Anti-Protestantism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anti-Protestantism is

Anti-Protestantism is

The

The

In 1870 the newly formed

In 1870 the newly formed

''Spanish Catholicism: An Historical Overview''

p. 186, 1984, University of Wisconsin Press Protestants, and forced many Protestant pastors to leave the country and various Protestant leaders were executed. Once authoritarian rule was established, non-Catholic Bibles were confiscated by police and Protestant schools were closed. Although the 1945 Spanish Bill of Rights granted freedom of ''private'' worship, Protestants suffered legal discrimination and non-Catholic religious services were not permitted publicly, to the extent that they could not be in buildings which had exterior signs indicating it was a house of worship and that public activities were prohibited.

In Northern Ireland or pre-

In Northern Ireland or pre-

Poll of Catholics

* * {{Theology Relations between Christian denominations

Anti-Protestantism is

Anti-Protestantism is bias

Bias is a disproportionate weight ''in favor of'' or ''against'' an idea or thing, usually in a way that is closed-minded, prejudicial, or unfair. Biases can be innate or learned. People may develop biases for or against an individual, a group ...

, hatred or distrust

Distrust is a formal way of not trusting any one party too much in a situation of grave risk or deep doubt. It is commonly expressed in civics as a division or balance of powers, or in politics as means of validating treaty terms. Systems based ...

against some or all branches of Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

and/or its followers.

Anti-Protestantism dates back to before the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and ...

itself, as various pre-Protestant groups such as Arnoldists

Arnoldists were a Proto-Protestant Christian movement in the 12th century, named after Arnold of Brescia, an advocate of ecclesiastical reform who criticized the great wealth and possessions of the Roman Catholic Church, while preaching against in ...

, Waldensians

The Waldensians (also known as Waldenses (), Vallenses, Valdesi or Vaudois) are adherents of a church tradition that began as an ascetic movement within Western Christianity before the Reformation.

Originally known as the "Poor Men of Lyon" in ...

, Hussites

The Hussites ( cs, Husité or ''Kališníci''; "Chalice People") were a Czech proto-Protestant Christian movement that followed the teachings of reformer Jan Hus, who became the best known representative of the Bohemian Reformation.

The Huss ...

and Lollards

Lollardy, also known as Lollardism or the Lollard movement, was a proto-Protestant Christian religious movement that existed from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catholic ...

were persecuted in Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

Europe. Protestants were not tolerated throughout most of Europe until the Peace of Augsburg of 1555 approved Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

as an alternative for Roman Catholicism as a state religion of various states within the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

. Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

was not recognized until the Peace of Westphalia of 1648. Other states, such as France, made similar agreements in the early stages of the Reformation. Poland–Lithuania had a long history of religious tolerance. However, the tolerance stopped after the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of battle ...

in Germany, the persecution of Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

and the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion is the term which is used in reference to a period of civil war between French Catholics and Protestants, commonly called Huguenots, which lasted from 1562 to 1598. According to estimates, between two and four mi ...

in France, the change in power between Protestant and Roman Catholic rulers after the death of Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

in England, and the launch of the Counter-Reformation in Italy, Spain, Habsburg Austria and Poland-Lithuania. Anabaptism

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. ...

arose as a part of the Radical Reformation, lacking the support of the state which Lutheranism and Calvinism enjoyed, and thus was persecuted. Theological disagreement initially led to a Lutheran-Reformed rivalry in the Reformation.

Protestants in Latin America were largely ostracized until the abolition of certain restrictions in the 20th century. Protestantism spread with Evangelicalism and Pentecostalism

Pentecostalism or classical Pentecostalism is a Protestant Charismatic Christian movement

gaining the majority of followers. North America became a shelter for Protestants who were fleeing Europe after the persecution increased.

Persecution of Protestants in Asia can be put under a common shield of the persecution Christians face in the Middle East and northern Africa, where Islam is the dominant religion.

History

Anti-Protestantism originated in a reaction by militant societies connected to the Roman Catholic Church alarmed at the spread of Protestantism following theProtestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and ...

of the 16th century. Martin Luther's Proclamation occurred in 1517. By 1540, Pope Paul III had sanctioned the first society pledged to extinguish Protestantism. Christian Protestantism was denounced as heresy, and those supporting these doctrines were excommunicated as heretics. Thus by canon law and the practice and policies of the Holy Roman Empire of the time, Protestants were subject to persecution in those territories, such as Spain, Italy and the Netherlands, in which the Catholic rulers were then the dominant power. This movement was started by the reigning Pope and various political rulers with a more political stake in the controversy then a religious one. These princes instituted policies as part of the Spanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition ( es, Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición), commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition ( es, Inquisición española), was established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand ...

, abuses of that crusade originally authorized for other reasons such as the Reconquista, and Morisco conversions, which ultimately led to the Counter Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

and the edicts of the Council of Trent

The Council of Trent ( la, Concilium Tridentinum), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation, it has been described a ...

. Therefore, the political repercussions of various European rulers supporting Roman Catholicism for their own political reasons over the new Protestant groups, only subsequently branded as heretical after rejection by the adherents of these doctrines of the Edicts of the Council of Trent, resulted in religious wars

A religious war or a war of religion, sometimes also known as a holy war ( la, sanctum bellum), is a war which is primarily caused or justified by differences in religion. In the modern period, there are frequent debates over the extent to wh ...

and outbreaks of sectarian violence.

Eastern Orthodoxy

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or "canonical") ...

had comparatively little contact with Protestantism for geographic, linguistic and historical reasons. Protestant attempts to ally with Eastern Orthodoxy proved problematic. In general, most Orthodox had the impression that Protestantism was a new heresy that arose from various previous heresies.

In 1771, Bishop Charles Walmesley

Charles Walmesley, OSB (best known by the pseudonyms Signor Pastorino or Pastorini; 13 January 1722 – 25 November 1797) was the Roman Catholic Titular Bishop of Rama and Vicar Apostolic of the Western District of England. He was known, especi ...

published his ''General History of the Christian Church from her birth to her Final Triumphant States in Heaven chiefly deduced from the Apocalypse of St. John the Apostle'', written under the pseudonym

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person or group assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true name (orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individua ...

of Signor Pastorini. The book forecast the end of Protestantism by 1825 and was published in at least 15 editions and several languages.

By the 19th century and later, some Eastern Orthodox thinkers, such as Nikolai Berdyaev, Seraphim Rose

Seraphim Rose (born Eugene Dennis Rose; August 13, 1934 – September 2, 1982), also known as Seraphim of Platina, was an American hieromonk of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia who co-founded the Saint Herman of Alaska Monastery in P ...

, and John Romanides

John Savvas Romanides ( el, Ιωάννης Σάββας Ρωμανίδης; 2 March 19271 November 2001) was a Greek-American theologian, Eastern Orthodox priest, and scholar who had a distinctive influence on post-war Greek Orthodox theology.

Bi ...

believed that Northern Europe had become secular or virtually atheist due to its having been Protestant earlier. In recent eras Orthodox anti-Protestantism has grown due to aggressive Protestant proselytization

Proselytism () is the policy of attempting to convert people's religious or political beliefs. Proselytism is illegal in some countries.

Some draw distinctions between '' evangelism'' or '' Da‘wah'' and proselytism regarding proselytism as invo ...

in predominantly Orthodox countries.

Reformation

The

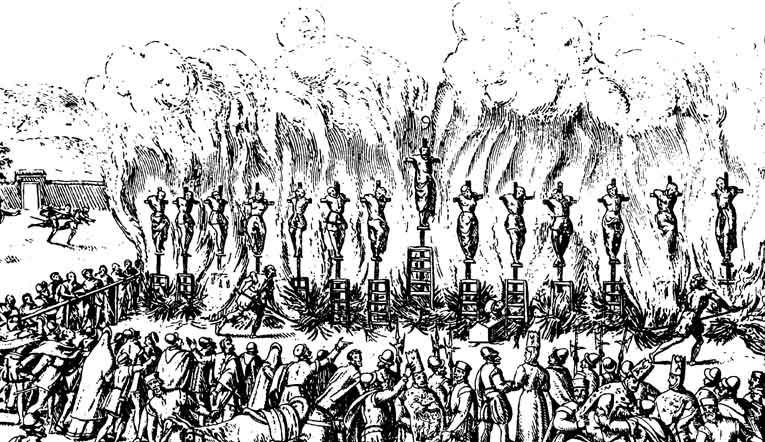

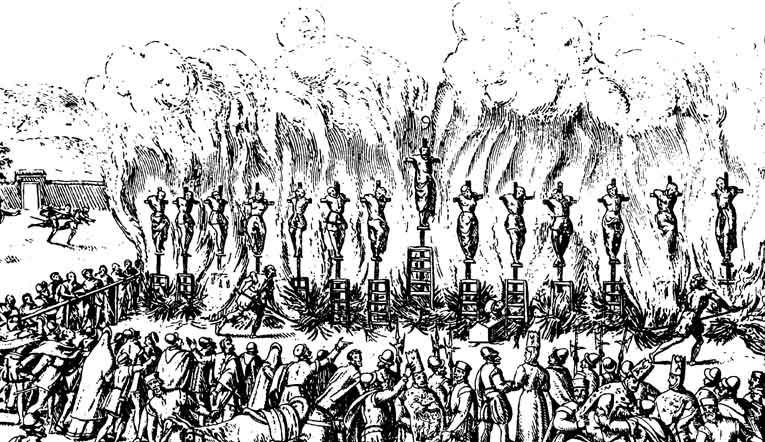

The Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and ...

led to a long period of warfare and communal violence between Catholic and Protestant factions, sometimes leading to massacres and forced suppression of the alternative views by the dominant faction in much of Europe.

Anti-Protestantism originated in a reaction by the Catholic Church against the Reformation of the 16th century. Protestants were denounced as heretics and subject to persecution in those territories, such as Spain, Italy and the Netherlands in which the Catholics were the dominant power. This movement was orchestrated by popes and princes as the Counter Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

. There were religious wars and eruptions of sectarian hatred such as the St Bartholomew's Day Massacre of 1572, part of the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion is the term which is used in reference to a period of civil war between French Catholics and Protestants, commonly called Huguenots, which lasted from 1562 to 1598. According to estimates, between two and four mi ...

in some countries, though not in others.

Fascist Italy

In 1870 the newly formed

In 1870 the newly formed Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to an institutional referendum to abandon the monarchy and f ...

annexed the remaining Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

, depriving the Pope of his temporal power. However, Papal rule over Italy was later restored by the Italian Fascist régime (albeit on a greatly diminished scale) in 1929 as head of the Vatican City

Vatican City (), officially the Vatican City State ( it, Stato della Città del Vaticano; la, Status Civitatis Vaticanae),—'

* german: Vatikanstadt, cf. '—' (in Austria: ')

* pl, Miasto Watykańskie, cf. '—'

* pt, Cidade do Vati ...

state; under Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

's dictatorship

A dictatorship is a form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, which holds governmental powers with few to no limitations on them. The leader of a dictatorship is called a dictator. Politics in a dictatorship a ...

, Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

became the state religion of Fascist Italy.

In 1938, the Italian Racial Laws and ''Manifesto of Race

The "Manifesto of Race" ( it, "Manifesto della razza", italics=no), otherwise referred to as the Charter of Race or the Racial Manifesto, was a manifesto which was promulgated by the Council of Ministers on the 14th of July 1938, its promulgation ...

'' were promulgated by the Fascist régime to both outlaw and persecute Italian Jews and Protestants,;

especially Evangelicals and Pentecostals

Pentecostalism or classical Pentecostalism is a Protestant Charismatic Christian movement

. Thousands of Italian Jews and a small number of Protestants died in the Nazi concentration camps

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps, (officially) or (more commonly). The Nazi concentration camps are distinguished from other types of Nazi camps such as forced-labor camps, as well as con ...

.

Francoist Spain

In Franco's authoritarian Spanish State (1936–1975), Protestantism was deliberately marginalized and persecuted. During the Civil War, Franco's regime persecuted the country's 30,000Payne, Stanle''Spanish Catholicism: An Historical Overview''

p. 186, 1984, University of Wisconsin Press Protestants, and forced many Protestant pastors to leave the country and various Protestant leaders were executed. Once authoritarian rule was established, non-Catholic Bibles were confiscated by police and Protestant schools were closed. Although the 1945 Spanish Bill of Rights granted freedom of ''private'' worship, Protestants suffered legal discrimination and non-Catholic religious services were not permitted publicly, to the extent that they could not be in buildings which had exterior signs indicating it was a house of worship and that public activities were prohibited.

Hostility to mainline Protestantism

Among theologically conservative Christians (including Catholics and Orthodox Christians, as well as Evangelicals and Protestant fundamentalists), mainline Protestant denominations are often characterized as being theologically liberal to the point where they are no longer true to the Bible or the historic Christian tradition. These perceptions are often linked to highly publicized events, such as the decision to endorsesame-sex marriage

Same-sex marriage, also known as gay marriage, is the marriage of two people of the same sex or gender. marriage between same-sex couples is legally performed and recognized in 33 countries, with the most recent being Mexico, constituting ...

by the United Church of Christ

The United Church of Christ (UCC) is a mainline Protestant Christian denomination based in the United States, with historical and confessional roots in the Congregational, Calvinist, Lutheran, and Anabaptist traditions, and with approximatel ...

. While theological liberalism is clearly present within most mainline denominations, surveys show that many within the mainline denominations consider themselves moderate or conservative and holding traditional Christian theological views.

Hostility to Evangelicals

In the United States, critics of the policies adopted by the Religious Right, such as opposition to same-sex marriage and abortion, often equate evangelicalism as a movement with the Religious Right. Many evangelicals belong to this political movement, although it is a diverse movement that draws support from other Protestants, Jews, Mormons, Catholics, and Eastern Orthodox, among other non-evangelical groups. Some critics have even suggested that evangelicals are a kind of " fifth column" aimed at turning the United States or other nations into Christian theocracies. Cultural progressive activists have indicated fear of a potential Christian theocracy as one of the reasons for their opposition to the Christian Right. Some evangelical groups that hold to a Dispensationalist interpretation of Biblical prophecy have been accused of supportingZionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

and providing material support for Jewish settlers who build communities within Palestinian territories. Critics contend that these evangelicals support Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

in order to expedite the building of the Third Temple

The "Third Temple" ( he, , , ) refers to a hypothetical rebuilt Temple in Jerusalem. It would succeed Solomon's Temple and the Second Temple, the former having been destroyed during the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem in and the latter havin ...

in Jerusalem, which Dispensationalists see as a requirement for the return of Jesus Christ. Many evangelicals reject Dispensationalism and support peace efforts in the Middle East, however.

Catholic and Protestant disagreement in Ireland

In Northern Ireland or pre-

In Northern Ireland or pre-Catholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, and later the combined United Kingdom in the late 18th century and early 19th century, that involved reducing and removing many of the restricti ...

Ireland, there is a hostility to Protestantism as a whole that has more to do with communal or nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

sentiments than theological issues. During the Tudor conquest of Ireland

The Tudor conquest (or reconquest) of Ireland took place under the Tudor dynasty, which held the Kingdom of England during the 16th century. Following a failed rebellion against the crown by Silken Thomas, the Earl of Kildare, in the 1530s, ...

by the Protestant state of England in the course of the 16th century, the Elizabethan state failed to convert Irish Catholics to Protestantism and thus followed a vigorous policy of confiscation, deportation, and resettlement. By dispossessing Catholics of their lands, and resettling Protestants on them, the official Government policy was to encourage a widespread campaign of proselytizing by Protestant settlers and establishment of English law in these areas. This led to a counter effort of the Counter Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

by mostly Jesuit Catholic clergy to maintain the "old religion" of the people as the dominant religion in these regions. The result was that Catholicism came to be identified with a sense of nativism and Protestantism came to be identified with the State, as most Protestant communities were established by state policy, and Catholicism was viewed as treason to the state after this time. While Elizabeth I had initially tolerated private Catholic worship, this ended after Pope Pius V

Pope Pius V ( it, Pio V; 17 January 1504 – 1 May 1572), born Antonio Ghislieri (from 1518 called Michele Ghislieri, O.P.), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1566 to his death in May 1572. He is v ...

, in his 1570 papal bull ''Regnans in Excelsis

''Regnans in Excelsis'' ("Reigning on High") is a papal bull that Pope Pius V issued on 25 February 1570. It excommunicated Queen Elizabeth I of England, referring to her as "the pretended Queen of England and the servant of crime", declared h ...

'', pronounced her to be illegitimate

Legitimacy, in traditional Western common law, is the status of a child born to parents who are legally married to each other, and of a child conceived before the parents obtain a legal divorce. Conversely, ''illegitimacy'', also known as '' ...

and unworthy of her subjects' allegiance.

The Penal Laws, first introduced in the early 17th century, were initially designed to force the native elite to conform to the state church by excluding non-Conformists and Roman Catholics from public office, and restricting land ownership, but were later, starting under Queen Elizabeth, also used to confiscate virtually all Catholic owned land and grant it to Protestant settlers from England and Scotland. The Penal Laws had a lasting effect on the population, due to their severity (celebrating Catholicism in any form was punishable by death or enslavement under the laws), and the favouritism granted Irish Anglicans served to polarise the community in terms of religion. Anti-Protestantism in Early Modern Ireland 1536–1691 thus was also largely a form of hostility to the colonisation of Ireland. Irish poetry of this era shows a marked antipathy to Protestantism, one such poem reading, "The faith of Christ atholicismwith the faith of Luther is like ashes in the snow". The mixture of resistance to colonization and religious disagreements led to widespread massacres of Protestant settlers in the Irish Rebellion of 1641. Subsequent religious or sectarian antipathy was fueled by the atrocities committed by both sides in the Irish Confederate Wars, especially the repression of Catholicism during and after the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, when Irish Catholic land was confiscated en masse, clergy were executed and discriminatory legislation was passed against Catholics.

The Penal Laws against Catholics (and also Presbyterians) were renewed in the late 17th and early 18th centuries due to fear of Catholic support for Jacobitism

, war =

, image = Prince James Francis Edward Stuart by Louis Gabriel Blanchet.jpg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = James Francis Edward Stuart, Jacobite claimant between 1701 and 1766

, active ...

after the Williamite War in Ireland

The Williamite War in Ireland (1688–1691; ga, Cogadh an Dá Rí, "war of the two kings"), was a conflict between Jacobite supporters of deposed monarch James II and Williamite supporters of his successor, William III. It is also called th ...

and were slowly repealed in 1771–1829. Penal Laws against Presbyterians were relaxed by the Toleration Act of 1719, due to their siding with the Jacobites in a 1715 rebellion. At the time the Penal Laws were in effect, Presbyterians and other non-Conformist Protestants left Ireland and settled in other countries. Some 250,000 left for the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

alone between the years 1717 and 1774, most of them arriving there from Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kin ...

.

Sectarian conflict was continued in the late 18th century in the form of communal violence between rival Catholic and Protestant factions over land and trading rights (see Defenders (Ireland)

The Defenders were a Catholic agrarian secret society in 18th-century Ireland, founded in County Armagh. Initially, they were formed as local defensive organisations opposed to the Protestant Peep o' Day Boys; however, by 1790 they had become a ...

, Peep O'Day Boys and Orange Institution

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots people, Ulster Sco ...

). The 1820s and 1830s in Ireland saw a major attempt by Protestant evangelists

Evangelists may refer to:

* Evangelists (Christianity), Christians who specialize in evangelism

* Four Evangelists, the authors of the four Gospel accounts in the New Testament

* ''The Evangelists

''The Evangelists'' (''Evangheliştii'' in Roma ...

to convert Catholics, a campaign which caused great resentment among Catholics.

In modern Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of c ...

, anti-Protestantism is usually more nationalist than religious in tone. The main reason for this is the identification of Protestants with unionism – i.e. the support for the maintenance of the union with the United Kingdom, and opposition to Home Rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

or Irish independence. In Northern Ireland, since the foundation of the Free State in 1921, Catholics, who were mainly nationalists, suffered systematic discrimination from the Protestant unionist majority. The same happened to Protestants in the Catholic-dominated South. ot in citation given

The mixture of religious and national identities on both sides reinforces both anti-Catholic and anti-Protestant sectarian prejudice in the province.

More specifically religious anti-Protestantism in Ireland was evidenced by the acceptance of the Ne Temere

''Ne Temere'' was a decree issued in 1907 by the Roman Catholic Congregation of the Council regulating the canon law of the Church regarding marriage for practising Catholics. It is named for its opening words, which literally mean "lest rashly" i ...

decrees in the early 20th century, whereby the Catholic Church decreed that all children born into mixed Catholic-Protestant marriages had to be brought up as Catholics. Protestants in Northern Ireland had long held that their religious liberty would be threatened under a 32-county Republic of Ireland, due to that country's Constitutional support of a "special place" for the Roman Catholic Church. This article was deleted in 1972.

During The Troubles

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an " ...

in Northern Ireland, Protestants with no connection to the security forces were occasionally targeted by Irish republican paramilitaries. In 1976, eleven Protestant workmen were shot by a group which was identified in a telephone call as the "South Armagh Republican Action Force". Ten of the men died, and the sole survivor said, "One man... did all the talking and proceeded to ask each of us our religion. Our Roman Catholic works colleague was ordered to clear off and the shooting started." A 2011 report from the Historical Enquiries Team

The Historical Enquiries Team was a unit of the Police Service of Northern Ireland set up in September 2005 to investigate the 3,269 unsolved murders committed during the Troubles, specifically between 1968 and 1998. It was wound up in Septembe ...

(HET) found, "These dreadful murders were carried out by the Provisional IRA

The Irish Republican Army (IRA; ), also known as the Provisional Irish Republican Army, and informally as the Provos, was an Irish republicanism, Irish republican paramilitary organisation that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland, fa ...

and none other."Moriarty, Gerry, "IRA blamed for 'sectarian slaughter' of 10 at Kingsmill", ''Irish Times'', 22 June 2011, p. 7.

See also

*Religious tolerance

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

* Anti-Christian sentiment

** Anti-Catholicism

** Anti-Eastern Orthodox sentiment

** Anti-Oriental Orthodox sentiment

** Anti-Mormonism

Anti-Mormonism is discrimination, persecution, hostility or prejudice directed against the Latter Day Saint movement, particularly the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church). The term is often used to describe people or literat ...

*Black legend (Spain)

The Black Legend ( es, Leyenda negra) or the Spanish Black Legend ( es, Leyenda negra española, link=no) is a theorised historiographical tendency which consists of anti-Spanish and anti-Catholic propaganda. Its proponents argue that its ro ...

* Counter-Reformation

* List of people burned as heretics

*Criticism of Protestantism

Criticism of Protestantism covers critiques and questions raised about Protestantism, the Christian denominations which arose out of the Protestant Reformation. While critics may praise some aspects of Protestantism which are not unique to the ...

References

External links

Poll of Catholics

* * {{Theology Relations between Christian denominations