Ann Bishop (biologist) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ann Bishop (19 December 1899 – 7 May 1990) was a British

Educated at home until she was seven, Bishop then went to a private elementary school until the age of nine. In 1909, then ten years old, she entered the progressive Fielden School in her hometown of Manchester, where she studied for three years. She completed her high school education at the

Educated at home until she was seven, Bishop then went to a private elementary school until the age of nine. In 1909, then ten years old, she entered the progressive Fielden School in her hometown of Manchester, where she studied for three years. She completed her high school education at the

Bishop's undergraduate work with Hickson was her first major research effort, concerning the reproduction of '' Spirostomum ambiguum'', a large ciliate that has been described as "wormlike". In 1923, while working at Manchester University, Bishop was appointed an honorary

Bishop's undergraduate work with Hickson was her first major research effort, concerning the reproduction of '' Spirostomum ambiguum'', a large ciliate that has been described as "wormlike". In 1923, while working at Manchester University, Bishop was appointed an honorary

Between 1937 and 1938, Bishop studied the effects of various factors, including different substances in blood and different temperatures, on the feeding behaviour of the chicken

Between 1937 and 1938, Bishop studied the effects of various factors, including different substances in blood and different temperatures, on the feeding behaviour of the chicken

biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual Cell (biology), cell, a multicellular organism, or a Community (ecology), community of Biological inter ...

from Girton College

Girton College is one of the Colleges of the University of Cambridge, 31 constituent colleges of the University of Cambridge. The college was established in 1869 by Emily Davies and Barbara Bodichon as the first women's college in Cambridge. In 1 ...

at the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209 and granted a royal charter by Henry III in 1231, Cambridge is the world's third oldest surviving university and one of its most pr ...

and a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemat ...

, one of the few female Fellows of the Royal Society

Female ( symbol: ♀) is the sex of an organism that produces the large non-motile ova (egg cells), the type of gamete (sex cell) that fuses with the male gamete during sexual reproduction.

A female has larger gametes than a male. Females ...

. She was born in Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

but stayed at Cambridge for the vast majority of her professional life. Her specialties were protozoology Protozoology is the study of protozoa, the "animal-like" (i.e., motile and heterotrophic) protists. The Protozoa are considered to be a subkingdom of Protista. They are free-living organisms that are found in almost every habitat. All humans have pr ...

and parasitology; early work with ciliate

The ciliates are a group of alveolates characterized by the presence of hair-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to eukaryotic flagella, but are in general shorter and present in much larger numbers, with a differen ...

parasites, including the one responsible for blackhead disease in the domesticated turkey

The domestic turkey (Meleagris gallopavo domesticus) is a large fowl, one of the two species in the genus '' Meleagris'' and the same species as the wild turkey. Although turkey domestication was thought to have occurred in central Mesoamerica a ...

, lay the groundwork for her later research. While working towards her doctorate, Bishop studied parasitic amoeba

An amoeba (; less commonly spelled ameba or amœba; plural ''am(o)ebas'' or ''am(o)ebae'' ), often called an amoeboid, is a type of cell or unicellular organism with the ability to alter its shape, primarily by extending and retracting pseudop ...

e and examined potential chemotherapies

Chemotherapy (often abbreviated to chemo and sometimes CTX or CTx) is a type of cancer treatment that uses one or more anti-cancer drugs (chemotherapeutic agents or alkylating agents) as part of a standardized chemotherapy regimen. Chemothera ...

for the treatment of amoebic diseases including amoebic dysentery

Amoebiasis, or amoebic dysentery, is an infection of the intestines caused by a parasitic amoeba ''Entamoeba histolytica''. Amoebiasis can be present with no, mild, or severe symptoms. Symptoms may include lethargy, loss of weight, colonic u ...

.

Her best known work was a comprehensive study of ''Plasmodium

''Plasmodium'' is a genus of unicellular eukaryotes that are obligate parasites of vertebrates and insects. The life cycles of ''Plasmodium'' species involve development in a blood-feeding insect host which then injects parasites into a ver ...

'', the malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

parasite, and investigation of various chemotherapies for the disease. Later she studied drug resistance

Drug resistance is the reduction in effectiveness of a medication such as an antimicrobial or an antineoplastic in treating a disease or condition. The term is used in the context of resistance that pathogens or cancers have "acquired", that is ...

in this parasite, research that proved valuable to the British military in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. She discovered the potential for cross-resistance

Cross-resistance is when something develops resistance to several substances that have a similar mechanism of action. For example, if a certain type of bacteria develops resistance to one antibiotic, that bacteria will also have resistance to sev ...

in these parasites during that same period. Bishop also discovered the protozoan '' Pseudotrichomonas keilini'' and worked with ''Aedes aegypti

''Aedes aegypti'', the yellow fever mosquito, is a mosquito that can spread dengue fever, chikungunya, Zika fever, Mayaro and yellow fever viruses, and other disease agents. The mosquito can be recognized by black and white markings on its le ...

'', a malaria vector

Vector most often refers to:

*Euclidean vector, a quantity with a magnitude and a direction

*Vector (epidemiology), an agent that carries and transmits an infectious pathogen into another living organism

Vector may also refer to:

Mathematic ...

, as part of her research on the disease. Elected to the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in 1959, Bishop was the founder of the British Society for Parasitology and served on the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of ...

's Malaria Committee.

Life

Bishop was born in Manchester, England on 19 December 1899. Her father, James Kimberly Bishop, was a furniture-maker who owned a cotton factory inherited from his father. Her mother, Ellen Bishop (''née'' Ginger), was fromBedfordshire

Bedfordshire (; abbreviated Beds) is a ceremonial county in the East of England. The county has been administered by three unitary authorities, Borough of Bedford, Central Bedfordshire and Borough of Luton, since Bedfordshire County Council ...

. Bishop had one brother, born when she was 13. At an early age, Bishop wished to continue the family business, though her interests quickly turned to the sciences after her father encouraged her to go to university. Appreciative of music from a young age, Bishop regularly attended performances of the Halle Orchestra Halle may refer to:

Places Germany

* Halle (Saale), also called Halle an der Saale, a city in Saxony-Anhalt

** Halle (region), a former administrative region in Saxony-Anhalt

** Bezirk Halle, a former administrative division of East Germany

** Hal ...

in Manchester. As a researcher, she was introverted and meticulous, preferring to work alone or with other scientists whom she considered to have high standards. She was a fixture at Girton College

Girton College is one of the Colleges of the University of Cambridge, 31 constituent colleges of the University of Cambridge. The college was established in 1869 by Emily Davies and Barbara Bodichon as the first women's college in Cambridge. In 1 ...

for most of her life; ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' dubbed her "Girtonian of Girtonians" in her obituary. A keen cook, she was also known for her annoyance at the lack of scientific measures in recipes she found.

Bishop was recognised at the college for her distinctive hats, which she would wear to breakfast every day before walking to the Molteno Institute, a distance of . She was skilled in needlework and appreciated the arts, though she did not like modern art. Her pastime

A hobby is considered to be a regular activity that is done for enjoyment, typically during one's leisure time. Hobbies include collecting themed items and objects, engaging in creative and artistic pursuits, playing sports, or pursuing oth ...

s included walking and travelling, especially in the Lake District: however, she rarely left Britain. She also spent time in London at the beginning of each year, attending the opera and ballet and visiting galleries. Towards the end of her life, when her mobility was limited by arthritis, Bishop developed a fascination with the history of biology

The history of biology traces the study of the living world from ancient to modern times. Although the concept of ''biology'' as a single coherent field arose in the 19th century, the biological sciences emerged from traditions of medicine a ...

and medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

, although she never published in that field. Ann Bishop died of pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severi ...

at the age of 90 after a short illness. Her memorial service

A funeral is a ceremony connected with the final disposition of a corpse, such as a burial or cremation, with the attendant observances. Funerary customs comprise the complex of beliefs and practices used by a culture to remember and respect th ...

was conducted in the college's chapel and was filled with her wide circle of friends.

Education

Educated at home until she was seven, Bishop then went to a private elementary school until the age of nine. In 1909, then ten years old, she entered the progressive Fielden School in her hometown of Manchester, where she studied for three years. She completed her high school education at the

Educated at home until she was seven, Bishop then went to a private elementary school until the age of nine. In 1909, then ten years old, she entered the progressive Fielden School in her hometown of Manchester, where she studied for three years. She completed her high school education at the Manchester High School for Girls

Manchester High School for Girls is an English independent day school for girls and a member of the Girls School Association. It is situated in Fallowfield, Manchester.

The head mistress is Helen Jeys who took up the position in September 2020 ...

. Though Bishop intended to study chemistry, her lack of education in physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

meant that she could not pursue her preferred course in the Honours School of Chemistry. Instead, she matriculated at Manchester University

, mottoeng = Knowledge, Wisdom, Humanity

, established = 2004 – University of Manchester Predecessor institutions: 1956 – UMIST (as university college; university 1994) 1904 – Victoria University of Manchester 1880 – Victoria Univer ...

in October 1918 to study botany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

, chemistry, and zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and ...

. That first-year course in zoology sparked her lifelong interest in and commitment to the field. She graduated with honours from the School of Zoology, receiving her Bachelor of Science degree in 1921; she received her master's degree in 1922. During her undergraduate years, under the tutelage of the helminthologist

Helminthology is the study of parasitic worms (helminths). The field studies the Taxonomy (biology), taxonomy of helminths and their effects on their host (biology), hosts.

The origin of the first compound of the word is the Greek ''wikt:ἕλ� ...

R.A. Wardle and the protozoologist Protozoology is the study of protozoa, the "animal-like" (i.e., motile and heterotrophic) protists. The Protozoa are considered to be a subkingdom of Protista. They are free-living organisms that are found in almost every habitat. All humans have pr ...

Geoffrey Lapage, Bishop studied ciliate

The ciliates are a group of alveolates characterized by the presence of hair-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to eukaryotic flagella, but are in general shorter and present in much larger numbers, with a differen ...

s acquired from local ponds.

Two years into her undergraduate career, after winning the John Dalton Natural History Prize awarded by the university, she began work for another protozoologist, a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemat ...

, Sydney J. Hickson

Sydney John Hickson FRS (25 June 1859 – 6 February 1940), was a British zoologist known for his groundbreaking research in evolution, embryology, genetics, and systematics.

Hickson travelled in the Malay archipelago in 1885–1886. He was a ...

. In 1932, she received her D.Sc.

Doctor of Science ( la, links=no, Scientiae Doctor), usually abbreviated Sc.D., D.Sc., S.D., or D.S., is an academic research degree awarded in a number of countries throughout the world. In some countries, "Doctor of Science" is the degree used f ...

from Manchester University, for her work with the blackhead parasite. She received her Sc.D.

Doctor of Science ( la, links=no, Scientiae Doctor), usually abbreviated Sc.D., D.Sc., S.D., or D.S., is an academic research degree awarded in a number of countries throughout the world. In some countries, "Doctor of Science" is the degree used f ...

from the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209 and granted a royal charter by Henry III in 1231, Cambridge is the world's third oldest surviving university and one of its most pr ...

in 1941, though it was in title only: women were not granted full degrees from Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

at this time.

Scientific career

Early work

Bishop's undergraduate work with Hickson was her first major research effort, concerning the reproduction of '' Spirostomum ambiguum'', a large ciliate that has been described as "wormlike". In 1923, while working at Manchester University, Bishop was appointed an honorary

Bishop's undergraduate work with Hickson was her first major research effort, concerning the reproduction of '' Spirostomum ambiguum'', a large ciliate that has been described as "wormlike". In 1923, while working at Manchester University, Bishop was appointed an honorary research fellow

A research fellow is an academic research position at a university or a similar research institution, usually for academic staff or faculty members. A research fellow may act either as an independent investigator or under the supervision of a pr ...

. In 1924, she became a part-time instructor for the Department of Zoology at Cambridge, one of only two women, both of whom were sometimes marginalised. For example, she was not allowed to sit at the table with the men of the department at tea: instead, she sat on a first-aid kit. There, Bishop continued her work with ''Spirostomum'' as the only protozoologist on the faculty.

She left that position in 1926, to work for Clifford Dobell

Cecil Clifford Dobell FRS (22 February 1886, Birkenhead – 23 December 1949, London) was a biologist, specifically a protozoologist. He studied intestinal amoebae, and algae. He was a leading authority on the history of protistology.

1910–19 ...

at the National Institute for Medical Research

The National Institute for Medical Research (commonly abbreviated to NIMR), was a medical research institute based in Mill Hill, on the outskirts of north London, England. It was funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC);

In 2016, the NIMR b ...

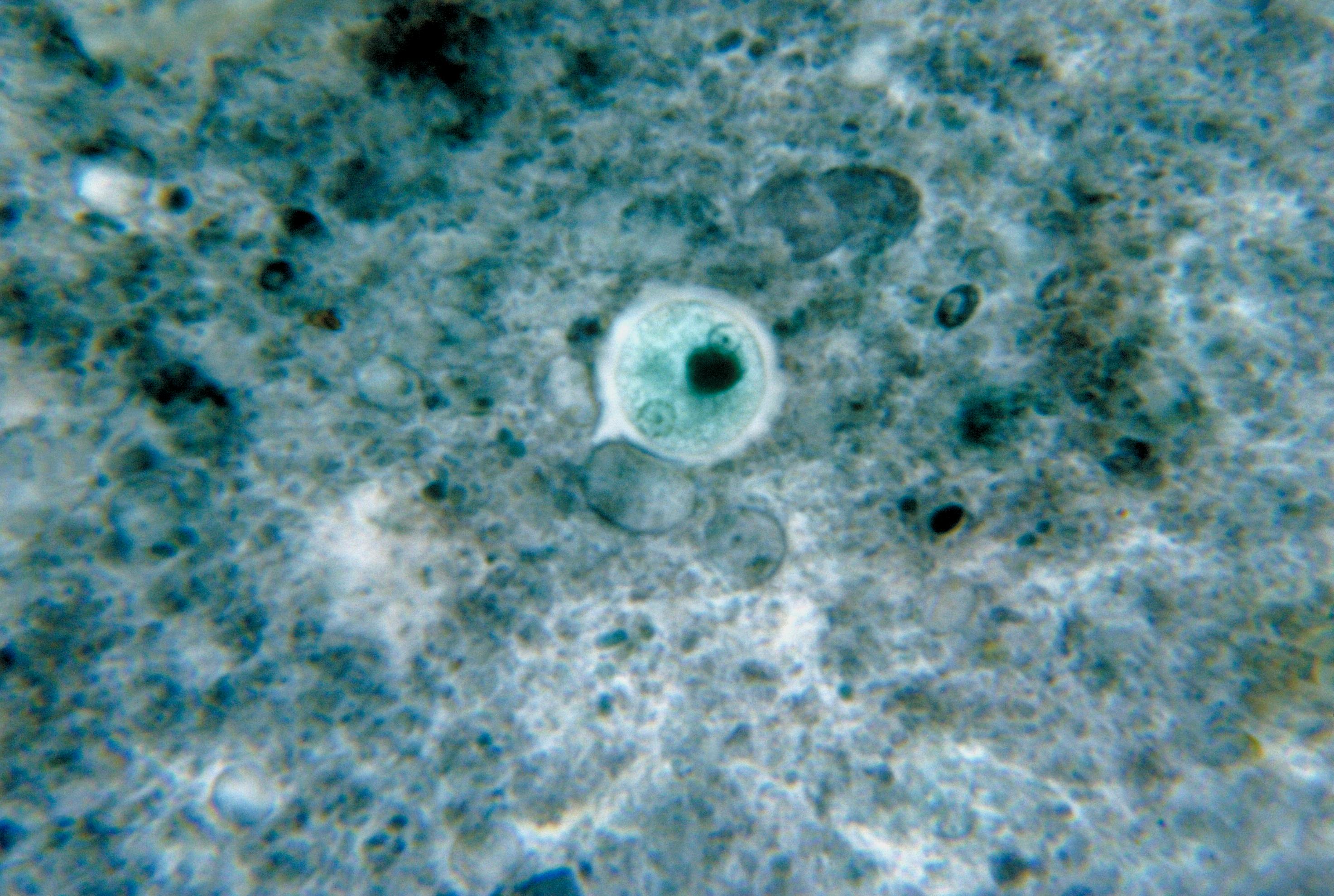

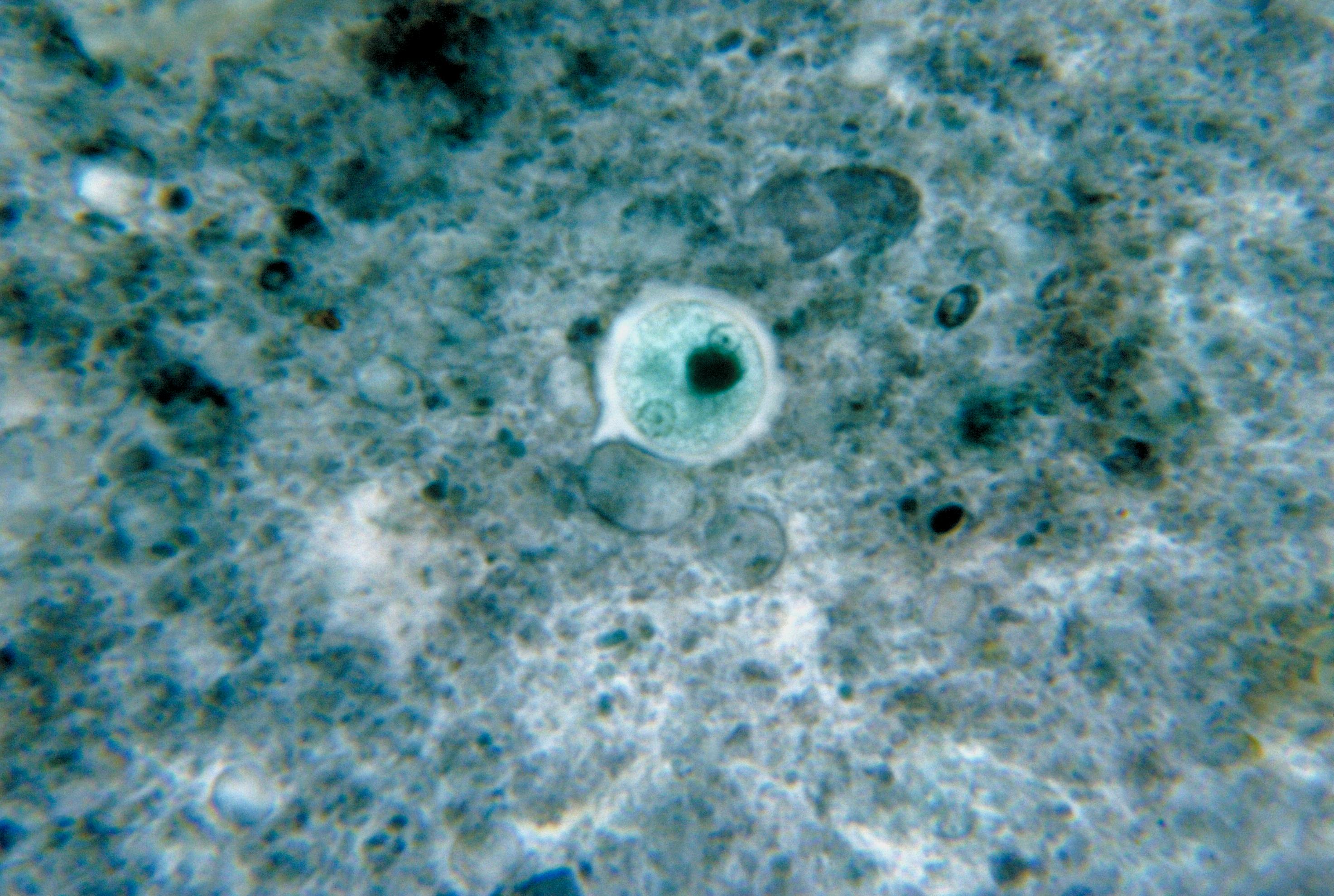

where she stayed there for three years. Under Dobell, Bishop studied parasitic

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson ha ...

amoeba

An amoeba (; less commonly spelled ameba or amœba; plural ''am(o)ebas'' or ''am(o)ebae'' ), often called an amoeboid, is a type of cell or unicellular organism with the ability to alter its shape, primarily by extending and retracting pseudop ...

e found in the human gastrointestinal tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans and ...

, focusing on the species responsible for amoebic dysentery

Amoebiasis, or amoebic dysentery, is an infection of the intestines caused by a parasitic amoeba ''Entamoeba histolytica''. Amoebiasis can be present with no, mild, or severe symptoms. Symptoms may include lethargy, loss of weight, colonic u ...

, ''Entamoeba histolytica

''Entamoeba histolytica'' is an anaerobic parasitic amoebozoan, part of the genus ''Entamoeba''. Predominantly infecting humans and other primates causing amoebiasis, ''E. histolytica'' is estimated to infect about 35-50 million people worldwid ...

''. Dobell, Bishop, and Patrick Laidlaw studied the effects of amoebicides like emetine

Emetine is a drug used as both an anti-protozoal and to induce vomiting. It is produced from the ipecac root. It takes its name from its emetic properties.

Early preparations

Mechanism of action of emetine was studied by François Magendie durin ...

for the purpose of treating amoebal diseases. Later in her career, she named the amoeba genus '' Dobellina'' after her mentor.

Molteno Institute

The majority of her career was spent at Cambridge's Molteno Institute for Parasite Biology, where she returned in 1929. Her work there was an extension of her research with Dobell, as she studied nuclear division in parasitic flagellates and amoebae of diverse species, including both vertebrates and invertebrates. She isolated one type of protozoan, aerotolerant anaerobes, from the digestive tract of '' Haemopis sanguisuga'' during this period. Bishop also discovered a new species, '' Pseudotrichomonas keilini'', which she named to acknowledge her colleagueDavid Keilin

David Keilin FRS (21 March 1887 – 27 February 1963) was a Jewish scientist focusing mainly on entomology.

Background and education

He was born in Moscow in 1887 and his family returned to Warsaw early in his youth. He did not attend scho ...

, as well as the parasite's resemblance to the genus ''Trichomonas

''Trichomonas'' is a genus of anaerobic excavate parasites of vertebrates. It was first discovered by Alfred François Donné in 1836 when he found these parasites in the pus of a patient suffering from vaginitis, an inflammation of the vagina. ...

''. Her research at Manchester with H.P. Baynon concerned the identification, isolation, and study of the turkey blackhead parasite (''Histomonas meleagridis

''Histomonas meleagridis'' is a species of parasitic protozoan that infects a wide range of birds including chickens, turkeys, peafowl, quail and pheasants, causing infectious enterohepatitis, or histomoniasis (blackhead diseases). ''H. meleagri ...

''); this study pioneered a technique for isolating and growing parasites from lesions on the liver. Bishop and Baynon were the first scientists to isolate ''Histomonas'' and then prove its role in blackhead. Bishop's expertise with parasitic protozoa translated into her best-known work, a comprehensive study of the malaria parasite (''Plasmodium

''Plasmodium'' is a genus of unicellular eukaryotes that are obligate parasites of vertebrates and insects. The life cycles of ''Plasmodium'' species involve development in a blood-feeding insect host which then injects parasites into a ver ...

'') and potential chemotherapies for the disease.

Between 1937 and 1938, Bishop studied the effects of various factors, including different substances in blood and different temperatures, on the feeding behaviour of the chicken

Between 1937 and 1938, Bishop studied the effects of various factors, including different substances in blood and different temperatures, on the feeding behaviour of the chicken malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

(''Plasmodium gallinaceum

''Plasmodium gallinaceum'' is a species of the genus ''Plasmodium'' (subgenus '' Haemamoeba'') that causes malaria in poultry.

Description

This species was described by Alexandre Joseph Emile Brumpt (1877–1951) a French professor of parasit ...

'') vector, ''Aedes aegypti

''Aedes aegypti'', the yellow fever mosquito, is a mosquito that can spread dengue fever, chikungunya, Zika fever, Mayaro and yellow fever viruses, and other disease agents. The mosquito can be recognized by black and white markings on its le ...

''. She also examined factors that contributed to ''Plasmodium'' reproduction. This work became the basis for subsequent ongoing research into a malaria vaccine

A malaria vaccine is a vaccine that is used to prevent malaria. The only approved use of a vaccine outside the EU, as of 2022, is RTS,S, known by the brand name ''Mosquirix''. In October 2021, the WHO for the first time recommended the large-s ...

. Her subsequent work was spurred by the outbreak of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. During the war, she investigated alternative chemotherapies for malaria. Her research aided the British war effort because the most prevalent antimalarial

Antimalarial medications or simply antimalarials are a type of antiparasitic chemical agent, often naturally derived, that can be used to treat or to prevent malaria, in the latter case, most often aiming at two susceptible target groups, young ...

, quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to '' Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal le ...

, was difficult to obtain due to the Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

occupation of the Dutch West Indies

The Dutch Caribbean (historically known as the Dutch West Indies) are the territories, colonies, and countries, former and current, of the Dutch Empire and the Kingdom of the Netherlands in the Caribbean Sea. They are in the north and south-wes ...

. From 1947 to 1964, she was in charge of the Institute's Chemotherapy Research Institute, associated with the Medical Research Council.

Bishop's work evolved to include studies of drug resistance

Drug resistance is the reduction in effectiveness of a medication such as an antimicrobial or an antineoplastic in treating a disease or condition. The term is used in the context of resistance that pathogens or cancers have "acquired", that is ...

in both the parasites and the host

A host is a person responsible for guests at an event or for providing hospitality during it.

Host may also refer to:

Places

* Host, Pennsylvania, a village in Berks County

People

*Jim Host (born 1937), American businessman

* Michel Host ...

organisms, the studies that would earn her a place in the Royal Society. Significant work from this period of Bishop's life included a study showing that the parasite itself did not develop resistance to quinine, but that host organisms could develop resistance to the drug proguanil. Her ''in vitro

''In vitro'' (meaning in glass, or ''in the glass'') studies are performed with microorganisms, cells, or biological molecules outside their normal biological context. Colloquially called " test-tube experiments", these studies in biology ...

'' research was proven accurate when the drugs she studied were used to treat patients who had tertian malaria, a form of the illness in which the paroxysm

Paroxysmal attacks or paroxysms (from Greek παροξυσμός) are a sudden recurrence or intensification of symptoms, such as a spasm or seizure. These short, frequent symptoms can be observed in various clinical conditions. They are usually ...

of fever occurs every third day. She also investigated the drugs pamaquine

Pamaquine is an 8-aminoquinoline drug formerly used for the treatment of malaria. It is closely related to primaquine.

Synonyms

*Plasmochin

*Plasmoquine

*Plasmaquine

Uses

Pamaquine is effective against the hypnozoites of the relapsing malarias ...

and atebrin, along with proguanil, though proguanil was the only one shown to cause the development of drug resistance. Other studies showed that malaria parasites could develop cross-resistance

Cross-resistance is when something develops resistance to several substances that have a similar mechanism of action. For example, if a certain type of bacteria develops resistance to one antibiotic, that bacteria will also have resistance to sev ...

to other antimalarial drugs. Bishop worked at Molteno until 1967. Her research and experimental protocols were later used in rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the order Rodentia (), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal species are rodents. They are n ...

and human studies, albeit with modifications.

Honours and legacy

Bishop received severalhonorary titles

An honorary position is one given as an honor, with no duties attached, and without payment. Other uses include:

* Honorary Academy Award, by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, United States

* Honorary Aryan, a status in Nazi Germany ...

and fellowships during her career. In 1932, she was appointed a Yallow Fellow of Girton College

Girton College is one of the Colleges of the University of Cambridge, 31 constituent colleges of the University of Cambridge. The college was established in 1869 by Emily Davies and Barbara Bodichon as the first women's college in Cambridge. In 1 ...

, an honour she held until her death in 1990. Bishop was also a Beit Fellow from 1929 to 1932. The Medical Research Council awarded her a grant in 1937 that sparked her study of ''Plasmodium''. In 1945 and 1947, she was involved in organising Girton College's Working Women's Summer School, an institution designed to provide intellectual fulfilment for women whose formal education ended at the age of 14. She was elected to the Royal Society in 1959, and at one point was a member of the Malaria Committee of the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of ...

.

The British Society for Parasitology was founded in the 1950s, largely due to Bishop's efforts. She was initially given only five pounds and a secretary to start the Society; to raise funds Bishop passed around a pudding basin at the Society's meetings. The society was originally a subgroup of the Institute of Biology at Cambridge, but it became an independent group in 1960 and was headed by Bishop. She was the president of the group, called the Institute of Biology Parasitology Group, from 1960 to 1962, the third overall leader of the group. Later that decade, the Department of Biology asked her to be the department head, but she declined because of the public nature of the role. For 20 years, the scientific journal '' Parasitology'' had Bishop on staff as an editor. Her lifelong association with Girton College prompted the placement of a plaque

Plaque may refer to:

Commemorations or awards

* Commemorative plaque, a plate or tablet fixed to a wall to mark an event, person, etc.

* Memorial Plaque (medallion), issued to next-of-kin of dead British military personnel after World War I

* Pl ...

commemorating her life, whose inscription, quoted from Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

, reads "''Felix, qui potuit rerum cognoscere causas

“” is verse 490 of Book 2 of the "Georgics" (29 BC), by the Latin poet Virgil (70 - 19 BC). It is literally translated as: “Fortunate, who was able to know the causes of things”. Dryden rendered it: "Happy the Man, who, studying Nature's La ...

''", Latin for "Happy is the one who has been able to get to know the causes of things". In 1992, the British Society for Parasitology created a grant in Bishop's name, the Ann Bishop Travelling Award, to aid young parasitologists in travelling for field work where their parasites of interest are endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found else ...

.

Selected publications

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *References

;Sources * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Bishop, Ann 1899 births 1990 deaths 20th-century British women scientists Alumni of Girton College, Cambridge Alumni of the University of Manchester Deaths from pneumonia in England British parasitologists British women biologists Fellows of Girton College, Cambridge Fellows of the Royal Society Female Fellows of the Royal Society Scientists from Manchester People educated at Manchester High School for Girls 20th-century British zoologists