Andrew M. Gleason on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

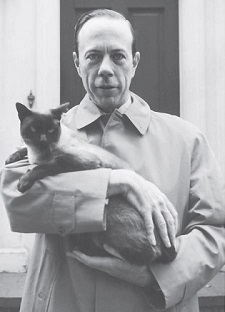

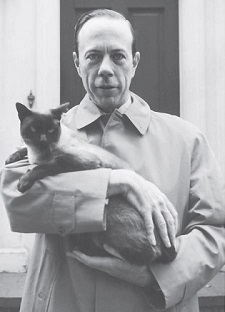

Andrew Mattei Gleason (19212008) was an American

Gleason was born in

Gleason was born in  In 1946, at the recommendation of Navy colleague Donald Howard Menzel, Gleason was appointed a

In 1946, at the recommendation of Navy colleague Donald Howard Menzel, Gleason was appointed a

Gleason said he "always enjoyed helping other people with math"a colleague said he "regarded teaching mathematicslike doing mathematicsas both important and also genuinely fun."

At fourteen, during his brief attendance at Berkeley High School, he found himself not only bored with first-semester geometry, but also helping other students with their homeworkincluding those taking the second half of the course, which he soon began auditing..

At Harvard he "regularly taught at every level", including administratively burdensome multisection courses.

One class presented Gleason with a framed print of Picasso's ''Mother and Child'' in recognition of his care for them.

In 1964 he created "the first of the 'bridge' courses now ubiquitous for math majors, only twenty years before its time." Such a course is designed to teach new students, accustomed to rote learning of mathematics in secondary school, how to reason abstractly and construct mathematical proofs. That effort led to publication of his ''Fundamentals of Abstract Analysis'', of which one reviewer wrote:

Gleason said he "always enjoyed helping other people with math"a colleague said he "regarded teaching mathematicslike doing mathematicsas both important and also genuinely fun."

At fourteen, during his brief attendance at Berkeley High School, he found himself not only bored with first-semester geometry, but also helping other students with their homeworkincluding those taking the second half of the course, which he soon began auditing..

At Harvard he "regularly taught at every level", including administratively burdensome multisection courses.

One class presented Gleason with a framed print of Picasso's ''Mother and Child'' in recognition of his care for them.

In 1964 he created "the first of the 'bridge' courses now ubiquitous for math majors, only twenty years before its time." Such a course is designed to teach new students, accustomed to rote learning of mathematics in secondary school, how to reason abstractly and construct mathematical proofs. That effort led to publication of his ''Fundamentals of Abstract Analysis'', of which one reviewer wrote:

But Gleason's "talent for exposition" did not always imply that the reader would be enlightened without effort of his own. Even in a wartime memo on the urgently important decryption of the German Enigma cipher, Gleason and his colleagues wrote:

His notes and exercises on probability and statistics, drawn up for his lectures to code-breaking colleagues during the war (see below) remained in use in

But Gleason's "talent for exposition" did not always imply that the reader would be enlightened without effort of his own. Even in a wartime memo on the urgently important decryption of the German Enigma cipher, Gleason and his colleagues wrote:

His notes and exercises on probability and statistics, drawn up for his lectures to code-breaking colleagues during the war (see below) remained in use in  Gleason was part of the

Gleason was part of the

During World War II Gleason was part of

During World War II Gleason was part of

In 1900 David Hilbert posed 23 problems he felt would be central to next century of mathematics research.

In 1900 David Hilbert posed 23 problems he felt would be central to next century of mathematics research.  Gleason's interest in the fifth problem began in the late 1940s, sparked by a course he took from

Gleason's interest in the fifth problem began in the late 1940s, sparked by a course he took from

The

The

The Ramsey number ''R''(''k'',''l'') is the smallest number ''r'' such that every graph with at least ''r'' vertices contains either a ''k''-vertex

The Ramsey number ''R''(''k'',''l'') is the smallest number ''r'' such that every graph with at least ''r'' vertices contains either a ''k''-vertex

Gleason published few contributions to

Gleason published few contributions to

In 1952 Gleason was awarded the American Association for the Advancement of Science's

In 1952 Gleason was awarded the American Association for the Advancement of Science's

mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems.

Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, structure, space, models, and change.

History

On ...

who made fundamental contributions to widely varied areas of mathematics, including the solution of Hilbert's fifth problem

Hilbert's fifth problem is the fifth mathematical problem from the problem list publicized in 1900 by mathematician David Hilbert, and concerns the characterization of Lie groups.

The theory of Lie groups describes continuous symmetry in mathem ...

, and was a leader in reform and innovation in teaching at all levels.. Gleason's theorem in quantum logic

In the mathematical study of logic and the physical analysis of quantum foundations, quantum logic is a set of rules for manipulation of propositions inspired by the structure of quantum theory. The field takes as its starting point an observ ...

and the Greenwood–Gleason graph, an important example in Ramsey theory

Ramsey theory, named after the British mathematician and philosopher Frank P. Ramsey, is a branch of mathematics that focuses on the appearance of order in a substructure given a structure of a known size. Problems in Ramsey theory typically ask ...

, are named for him.

As a young World War II naval officer, Gleason broke German and Japanese military codes. After the war he spent his entire academic career at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

, from which he retired in 1992. His numerous academic and scholarly leadership posts included chairmanship of the Harvard Mathematics Department and the Harvard Society of Fellows

The Society of Fellows is a group of scholars selected at the beginnings of their careers by Harvard University for their potential to advance academic wisdom, upon whom are bestowed distinctive opportunities to foster their individual and intell ...

, and presidency of the American Mathematical Society

The American Mathematical Society (AMS) is an association of professional mathematicians dedicated to the interests of mathematical research and scholarship, and serves the national and international community through its publications, meetings, ...

. He continued to advise the United States government on cryptographic security, and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts on education for children, almost until the end of his life.

Gleason won the Newcomb Cleveland Prize The Newcomb Cleveland Prize of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is annually awarded to author(s) of outstanding scientific paper published in the Research Articles or Reports sections of ''Science''. Established in 192 ...

in 1952 and the Gung–Hu Distinguished Service Award of the American Mathematical Society in 1996. He was a member of the National Academy of Sciences and of the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

, and held the Hollis Chair of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy The Hollis Chair of Mathematicks and Natural Philosophy is an endowed professorship established at Harvard College in 1727 by Thomas Hollis. The chair, now part of the Physics Department, is the second oldest at Harvard, and the oldest professors ...

at Harvard.

He was fond of saying that proofs "really aren't there to convince you that something is truethey're there to show you why it is true." The ''Notices of the American Mathematical Society

''Notices of the American Mathematical Society'' is the membership journal of the American Mathematical Society (AMS), published monthly except for the combined June/July issue. The first volume appeared in 1953. Each issue of the magazine since ...

'' called him "one of the quiet giants of twentieth-century mathematics, the consummate professor dedicated to scholarship, teaching, and service in equal measure."

Biography

Gleason was born in

Gleason was born in Fresno, California

Fresno () is a major city in the San Joaquin Valley of California, United States. It is the county seat of Fresno County and the largest city in the greater Central Valley region. It covers about and had a population of 542,107 in 2020, maki ...

, the youngest of three children;

his father Henry Gleason

Henry Allan Gleason (1882–1975) was an American ecologist, botanist, and taxonomist. He was known for his endorsement of the individualistic or open community concept of ecological succession, and his opposition to Frederic Clements's concept ...

was a botanist and a member of the Mayflower Society, and his mother was the daughter of Swiss-American winemaker Andrew Mattei.

His older brother Henry Jr. became a linguist.

He grew up in Bronxville, New York, where his father was the curator of the New York Botanical Garden

The New York Botanical Garden (NYBG) is a botanical garden at Bronx Park in the Bronx, New York City. Established in 1891, it is located on a site that contains a landscape with over one million living plants; the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory, ...

.

.

After briefly attending Berkeley High School (Berkeley, California)

he graduated from Roosevelt High School in Yonkers, winning a scholarship to Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Sta ...

.

Though Gleason's mathematics education had gone only so far as some self-taught calculus, Yale mathematician William Raymond Longley urged him to try a course in mechanics

Mechanics (from Ancient Greek: μηχανική, ''mēkhanikḗ'', "of machines") is the area of mathematics and physics concerned with the relationships between force, matter, and motion among physical objects. Forces applied to object ...

normally intended for juniors.

One month later he enrolled in a differential equations course ("mostly full of seniors") as well. When Einar Hille temporarily replaced the regular instructor, Gleason found Hille's style "unbelievably different ... He had a view of mathematics that was just vastly different ... That was a very important experience for me. So after that I took a lot of courses from Hille" including, in his sophomore year, graduate-level real analysis. "Starting with that course with Hille, I began to have some sense of what mathematics is about."

While at Yale he competed three times (1940, 1941 and 1942) in the recently founded William Lowell Putnam Mathematical Competition

The William Lowell Putnam Mathematical Competition, often abbreviated to Putnam Competition, is an annual mathematics competition for undergraduate college students enrolled at institutions of higher learning in the United States and Canada (regar ...

, always placing among the top five entrants in the country (making him the second three-time Putnam Fellow

The William Lowell Putnam Mathematical Competition, often abbreviated to Putnam Competition, is an annual mathematics competition for undergraduate college students enrolled at institutions of higher learning in the United States and Canada (regar ...

).

After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor during his senior year, Gleason applied for a commission in the US Navy,.

and on graduation

joined the team working to break Japanese naval codes

The vulnerability of Japanese naval codes and ciphers was crucial to the conduct of World War II, and had an important influence on foreign relations between Japan and the west in the years leading up to the war as well. Every Japanese code was e ...

.

(Others on this team included his future collaborator Robert E. Greenwood and Yale professor Marshall Hall Jr.)

He also collaborated with British researchers attacking the German Enigma cipher;

Alan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing (; 23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954) was an English mathematician, computer scientist, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. Turing was highly influential in the development of theoretical co ...

, who spent substantial time with Gleason while visiting Washington, called him "the brilliant young Yale graduate mathematician" in a report of his visit.

In 1946, at the recommendation of Navy colleague Donald Howard Menzel, Gleason was appointed a

In 1946, at the recommendation of Navy colleague Donald Howard Menzel, Gleason was appointed a Junior Fellow

The Society of Fellows is a group of scholars selected at the beginnings of their careers by Harvard University for their potential to advance academic wisdom, upon whom are bestowed distinctive opportunities to foster their individual and intell ...

at Harvard.

An early goal of the Junior Fellows program was to allow young scholars showing extraordinary promise to sidestep the lengthy PhD process; four years later Harvard appointed Gleason an assistant professor of mathematics,

though he was almost immediately recalled to Washington for cryptographic work related to the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

.

He returned to Harvard in the fall of 1952, and soon after published the most important of his results on Hilbert's fifth problem (see below).

Harvard awarded him tenure

Tenure is a category of academic appointment existing in some countries. A tenured post is an indefinite academic appointment that can be terminated only for cause or under extraordinary circumstances, such as financial exigency or program disco ...

the following year.

In January 1959 he married Jean Berko

whom he had met at a party featuring the music of Tom Lehrer

Thomas Andrew Lehrer (; born April 9, 1928) is an American former musician, singer-songwriter, satirist, and mathematician, having lectured on mathematics and musical theater. He is best known for the pithy and humorous songs that he recorded in ...

..

Berko, a psycholinguist

Psycholinguistics or psychology of language is the study of the interrelation between linguistic factors and psychological aspects. The discipline is mainly concerned with the mechanisms by which language is processed and represented in the mind ...

, worked for many years at Boston University

Boston University (BU) is a Private university, private research university in Boston, Massachusetts. The university is nonsectarian, but has a historical affiliation with the United Methodist Church. It was founded in 1839 by Methodists with ...

.

They had three daughters.

In 1969 Gleason took the Hollis Chair of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy The Hollis Chair of Mathematicks and Natural Philosophy is an endowed professorship established at Harvard College in 1727 by Thomas Hollis. The chair, now part of the Physics Department, is the second oldest at Harvard, and the oldest professors ...

. Established in 1727, this is the oldest scientific endowed professorship

A financial endowment is a legal structure for managing, and in many cases indefinitely perpetuating, a pool of Financial instrument, financial, real estate, or other investments for a specific purpose according to Donor intent, the will of its fou ...

in the US.

He retired from Harvard in 1992 but remained active in service to Harvard (as chair of the Society of Fellows

The Society of Fellows is a group of scholars selected at the beginnings of their careers by Harvard University for their potential to advance academic wisdom, upon whom are bestowed distinctive opportunities to foster their individual and intell ...

, for example)

and to mathematics: in particular, promoting the Harvard Calculus Reform Project.

and working with the Massachusetts Board of Education The Massachusetts Board of Elementary and Secondary Education (BESE) is the state education agency responsible for interpreting and implementing laws relevant to public education in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Public education in the Commonw ...

.

He died in 2008 from complications following surgery.

Teaching and education reform

Gleason said he "always enjoyed helping other people with math"a colleague said he "regarded teaching mathematicslike doing mathematicsas both important and also genuinely fun."

At fourteen, during his brief attendance at Berkeley High School, he found himself not only bored with first-semester geometry, but also helping other students with their homeworkincluding those taking the second half of the course, which he soon began auditing..

At Harvard he "regularly taught at every level", including administratively burdensome multisection courses.

One class presented Gleason with a framed print of Picasso's ''Mother and Child'' in recognition of his care for them.

In 1964 he created "the first of the 'bridge' courses now ubiquitous for math majors, only twenty years before its time." Such a course is designed to teach new students, accustomed to rote learning of mathematics in secondary school, how to reason abstractly and construct mathematical proofs. That effort led to publication of his ''Fundamentals of Abstract Analysis'', of which one reviewer wrote:

Gleason said he "always enjoyed helping other people with math"a colleague said he "regarded teaching mathematicslike doing mathematicsas both important and also genuinely fun."

At fourteen, during his brief attendance at Berkeley High School, he found himself not only bored with first-semester geometry, but also helping other students with their homeworkincluding those taking the second half of the course, which he soon began auditing..

At Harvard he "regularly taught at every level", including administratively burdensome multisection courses.

One class presented Gleason with a framed print of Picasso's ''Mother and Child'' in recognition of his care for them.

In 1964 he created "the first of the 'bridge' courses now ubiquitous for math majors, only twenty years before its time." Such a course is designed to teach new students, accustomed to rote learning of mathematics in secondary school, how to reason abstractly and construct mathematical proofs. That effort led to publication of his ''Fundamentals of Abstract Analysis'', of which one reviewer wrote:

But Gleason's "talent for exposition" did not always imply that the reader would be enlightened without effort of his own. Even in a wartime memo on the urgently important decryption of the German Enigma cipher, Gleason and his colleagues wrote:

His notes and exercises on probability and statistics, drawn up for his lectures to code-breaking colleagues during the war (see below) remained in use in

But Gleason's "talent for exposition" did not always imply that the reader would be enlightened without effort of his own. Even in a wartime memo on the urgently important decryption of the German Enigma cipher, Gleason and his colleagues wrote:

His notes and exercises on probability and statistics, drawn up for his lectures to code-breaking colleagues during the war (see below) remained in use in National Security Agency

The National Security Agency (NSA) is a national-level intelligence agency of the United States Department of Defense, under the authority of the Director of National Intelligence (DNI). The NSA is responsible for global monitoring, collect ...

training for several decades; they were published openly in 1985.

In a 1964 ''Science'' article, Gleason wrote of an apparent paradox arising in attempts to explain mathematics to nonmathematicians:

Gleason was part of the

Gleason was part of the School Mathematics Study Group

The School Mathematics Study Group (SMSG) was an American academic think tank focused on the subject of reform in mathematics education. Directed by Edward G. Begle and financed by the National Science Foundation, the group was created in the wa ...

, which helped define the New Math of the 1960sambitious changes in American elementary and high school mathematics teaching emphasizing understanding of concepts over rote algorithms. Gleason was "always interested in how people learn"; as part of the New Math effort he spent most mornings over several months with second-graders. Some years later he gave a talk in which he described his goal as having been:

In 1986 he helped found the Calculus Consortium, which has published a successful and influential series of "calculus reform" textbooks for college and high school, on precalculus, calculus, and other areas. His "credo for this program as for all of his teaching was that the ideas should be based in equal parts of geometry for visualization of the concepts, computation for grounding in the real world, and algebraic manipulation for power." However, the program faced heavy criticism from the mathematics community for its omission of topics such as the mean value theorem, and for its perceived lack of mathematical rigor.

Cryptanalysis work

During World War II Gleason was part of

During World War II Gleason was part of OP-20-G

OP-20-G or "Office of Chief Of Naval Operations (OPNAV), 20th Division of the Office of Naval Communications, G Section / Communications Security", was the U.S. Navy's signals intelligence and cryptanalysis group during World War II. Its mission ...

, the U.S. Navy's signals intelligence and cryptanalysis group.

One task of this group, in collaboration with British cryptographers at Bletchley Park

Bletchley Park is an English country house and estate in Bletchley, Milton Keynes ( Buckinghamshire) that became the principal centre of Allied code-breaking during the Second World War. The mansion was constructed during the years followin ...

such as Alan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing (; 23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954) was an English mathematician, computer scientist, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. Turing was highly influential in the development of theoretical co ...

, was to penetrate German Enigma machine communications networks. The British had great success with two of these networks, but the third, used for German-Japanese naval coordination, remained unbroken because of a faulty assumption that it employed a simplified version of Enigma. After OP-20-G's Marshall Hall observed that certain metadata in Berlin-to-Tokyo transmissions used letter sets disjoint from those used in Tokyo-to-Berlin metadata, Gleason hypothesized that the corresponding unencrypted letters sets were A-M (in one direction) and N-Z (in the other), then devised novel statistical tests by which he confirmed this hypothesis. The result was routine decryption of this third network by 1944. (This work also involved deeper related to permutation groups and the graph isomorphism problem

The graph isomorphism problem is the computational problem of determining whether two finite graphs are isomorphic.

The problem is not known to be solvable in polynomial time nor to be NP-complete, and therefore may be in the computational compl ...

.)

OP-20-G then turned to the Japanese navy's "Coral" cipher. A key tool for the attack on Coral was the "Gleason crutch", a form of Chernoff bound

In probability theory, the Chernoff bound gives exponentially decreasing bounds on tail distributions of sums of independent random variables. Despite being named after Herman Chernoff, the author of the paper it first appeared in, the result is d ...

on tail distributions of sums of independent random variables. Gleason's classified work on this bound predated Chernoff's work by a decade.

Toward the end of the war he concentrated on documenting the work of OP-20-G and developing systems for training new cryptographers.

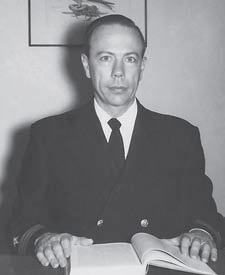

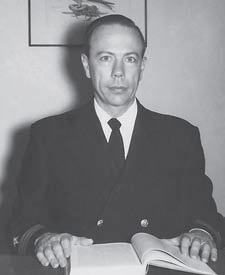

In 1950 Gleason returned to active duty for the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

, serving as a Lieutenant Commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding ran ...

in the Nebraska Avenue Complex (which much later became the home of the DHS Cyber Security Division). His cryptographic work from this period remains classified, but it is known that he recruited mathematicians and taught them cryptanalysis.

He served on the advisory boards for the National Security Agency

The National Security Agency (NSA) is a national-level intelligence agency of the United States Department of Defense, under the authority of the Director of National Intelligence (DNI). The NSA is responsible for global monitoring, collect ...

and the Institute for Defense Analyses, and he continued to recruit, and to advise the military on cryptanalysis, almost to the end of his life.

Mathematics research

Gleason made fundamental contributions to widely varied areas of mathematics, including the theory of Lie groups,quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is a fundamental theory in physics that provides a description of the physical properties of nature at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles. It is the foundation of all quantum physics including quantum chemistr ...

,.

and combinatorics.

According to Freeman Dyson

Freeman John Dyson (15 December 1923 – 28 February 2020) was an English-American theoretical physicist and mathematician known for his works in quantum field theory, astrophysics, random matrices, mathematical formulation of quantum m ...

's famous classification of mathematicians as being either birds or frogs,

Gleason was a frog: he worked as a problem solver rather than a visionary formulating grand theories..

Hilbert's fifth problem

In 1900 David Hilbert posed 23 problems he felt would be central to next century of mathematics research.

In 1900 David Hilbert posed 23 problems he felt would be central to next century of mathematics research. Hilbert's fifth problem

Hilbert's fifth problem is the fifth mathematical problem from the problem list publicized in 1900 by mathematician David Hilbert, and concerns the characterization of Lie groups.

The theory of Lie groups describes continuous symmetry in mathem ...

concerns the characterization

Characterization or characterisation is the representation of persons (or other beings or creatures) in narrative and dramatic works. The term character development is sometimes used as a synonym. This representation may include direct methods ...

of Lie groups by their actions

Action may refer to:

* Action (narrative), a literary mode

* Action fiction, a type of genre fiction

* Action game, a genre of video game

Film

* Action film, a genre of film

* ''Action'' (1921 film), a film by John Ford

* ''Action'' (1980 fi ...

on topological space

In mathematics, a topological space is, roughly speaking, a geometrical space in which closeness is defined but cannot necessarily be measured by a numeric distance. More specifically, a topological space is a set whose elements are called po ...

s: to what extent does their topology provide information sufficient to determine their geometry?

The "restricted" version of Hilbert's fifth problem (solved by Gleason) asks, more specifically, whether every locally In mathematics, a mathematical object is said to satisfy a property locally, if the property is satisfied on some limited, immediate portions of the object (e.g., on some ''sufficiently small'' or ''arbitrarily small'' neighborhoods of points).

P ...

Euclidean topological group

In mathematics, topological groups are logically the combination of groups and topological spaces, i.e. they are groups and topological spaces at the same time, such that the continuity condition for the group operations connects these two st ...

is a Lie group. That is, if a group ''G'' has the structure of a topological manifold In topology, a branch of mathematics, a topological manifold is a topological space that locally resembles real ''n''-dimensional Euclidean space. Topological manifolds are an important class of topological spaces, with applications throughout math ...

, can that structure be strengthened to a real analytic structure, so that within any neighborhood of an element of ''G'', the group law is defined by a convergent power series, and so that overlapping neighborhoods have compatible power series definitions? Prior to Gleason's work, special cases of the problem had been solved by Luitzen Egbertus Jan Brouwer

Luitzen Egbertus Jan Brouwer (; ; 27 February 1881 – 2 December 1966), usually cited as L. E. J. Brouwer but known to his friends as Bertus, was a Dutch mathematician and philosopher, who worked in topology, set theory, measure theory and compl ...

, John von Neumann

John von Neumann (; hu, Neumann János Lajos, ; December 28, 1903 – February 8, 1957) was a Hungarian-American mathematician, physicist, computer scientist, engineer and polymath. He was regarded as having perhaps the widest cove ...

, Lev Pontryagin

Lev Semenovich Pontryagin (russian: Лев Семёнович Понтрягин, also written Pontriagin or Pontrjagin) (3 September 1908 – 3 May 1988) was a Soviet mathematician. He was born in Moscow and lost his eyesight completely due ...

, and Garrett Birkhoff

Garrett Birkhoff (January 19, 1911 – November 22, 1996) was an American mathematician. He is best known for his work in lattice theory.

The mathematician George Birkhoff (1884–1944) was his father.

Life

The son of the mathematician Ge ...

, among others..

.

Gleason's interest in the fifth problem began in the late 1940s, sparked by a course he took from

Gleason's interest in the fifth problem began in the late 1940s, sparked by a course he took from George Mackey

George Whitelaw Mackey (February 1, 1916 – March 15, 2006) was an American mathematician known for his contributions to quantum logic, representation theory, and noncommutative geometry.

Career

Mackey earned his bachelor of arts at Rice Unive ...

.

In 1949 he published a paper introducing the "no small subgroups" property of Lie groups (the existence of a neighborhood of the identity within which no nontrivial subgroup exists) that would eventually be crucial to its solution.

His 1952 paper on the subject, together with a paper published concurrently by Deane Montgomery

Deane Montgomery (September 2, 1909 – March 15, 1992) was an American mathematician specializing in topology who was one of the contributors to the final resolution of Hilbert's fifth problem in the 1950s. He served as President of the America ...

and Leo Zippin

Leo Zippin (1905 – May 11, 1995) was an American mathematician. He is best known for solving Hilbert's fifth problem, Hilbert's Fifth Problem with Deane Montgomery and Andrew M. Gleason in 1952.

Biography

Leo Zippin was born in 1905 to Bella ...

, solves affirmatively the restricted version of Hilbert's fifth problem, showing that indeed every locally Euclidean group is a Lie group. Gleason's contribution was to prove that this is true when ''G'' has the no small subgroups property; Montgomery and Zippin showed every locally Euclidean group has this property. As Gleason told the story, the key insight of his proof was to apply the fact that monotonic function

In mathematics, a monotonic function (or monotone function) is a function between ordered sets that preserves or reverses the given order. This concept first arose in calculus, and was later generalized to the more abstract setting of order ...

s are differentiable

In mathematics, a differentiable function of one real variable is a function whose derivative exists at each point in its domain. In other words, the graph of a differentiable function has a non-vertical tangent line at each interior point in its ...

almost everywhere

In measure theory (a branch of mathematical analysis), a property holds almost everywhere if, in a technical sense, the set for which the property holds takes up nearly all possibilities. The notion of "almost everywhere" is a companion notion to ...

. On finding the solution, he took a week of leave to write it up, and it was printed in the ''Annals of Mathematics

The ''Annals of Mathematics'' is a mathematical journal published every two months by Princeton University and the Institute for Advanced Study.

History

The journal was established as ''The Analyst'' in 1874 and with Joel E. Hendricks as the ...

'' alongside the paper of Montgomery and Zippin; another paper a year later by Hidehiko Yamabe

was a Japanese mathematician. Above all, he is famous for discovering that every conformal class on a smooth compact manifold is represented by a Riemannian metric of constant scalar curvature. Other notable contributions include his definitive ...

removed some technical side conditions from Gleason's proof.

The "unrestricted" version of Hilbert's fifth problem, closer to Hilbert's original formulation, considers both a locally Euclidean group ''G'' and another manifold ''M'' on which ''G'' has a continuous action. Hilbert asked whether, in this case, ''M'' and the action of ''G'' could be given a real analytic structure. It was quickly realized that the answer was negative, after which attention centered on the restricted problem. However, with some additional smoothness assumptions on ''G'' and ''M'', it might yet be possible to prove the existence of a real analytic structure on the group action. The Hilbert–Smith conjecture, still unsolved, encapsulates the remaining difficulties of this case.

Quantum mechanics

The

The Born rule

The Born rule (also called Born's rule) is a key postulate of quantum mechanics which gives the probability that a measurement of a quantum system will yield a given result. In its simplest form, it states that the probability density of findi ...

states that an observable property of a quantum system is defined by a Hermitian operator

In mathematics, a self-adjoint operator on an infinite-dimensional complex vector space ''V'' with inner product \langle\cdot,\cdot\rangle (equivalently, a Hermitian operator in the finite-dimensional case) is a linear map ''A'' (from ''V'' to it ...

on a separable Hilbert space, that the only observable values of the property are the eigenvalue

In linear algebra, an eigenvector () or characteristic vector of a linear transformation is a nonzero vector that changes at most by a scalar factor when that linear transformation is applied to it. The corresponding eigenvalue, often denoted ...

s of the operator, and that the probability of the system being observed in a particular eigenvalue is the square of the absolute value of the complex number obtained by projecting the state vector (a point in the Hilbert space) onto the corresponding eigenvector.

George Mackey

George Whitelaw Mackey (February 1, 1916 – March 15, 2006) was an American mathematician known for his contributions to quantum logic, representation theory, and noncommutative geometry.

Career

Mackey earned his bachelor of arts at Rice Unive ...

had asked whether Born's rule is a necessary consequence of a particular set of axioms for quantum mechanics, and more specifically whether every measure on the lattice of projections of a Hilbert space can be defined by a positive operator with unit trace

Trace may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* ''Trace'' (Son Volt album), 1995

* ''Trace'' (Died Pretty album), 1993

* Trace (band), a Dutch progressive rock band

* ''The Trace'' (album)

Other uses in arts and entertainment

* ''Trace'' ...

. Though Richard Kadison proved this was false for two-dimensional Hilbert spaces, Gleason's theorem (published 1957) shows it to be true for higher dimensions.

Gleason's theorem implies the nonexistence of certain types of hidden variable theories

In physics, hidden-variable theories are proposals to provide explanations of quantum mechanical phenomena through the introduction of (possibly unobservable) hypothetical entities. The existence of fundamental indeterminacy for some measurem ...

for quantum mechanics, strengthening a previous argument of John von Neumann

John von Neumann (; hu, Neumann János Lajos, ; December 28, 1903 – February 8, 1957) was a Hungarian-American mathematician, physicist, computer scientist, engineer and polymath. He was regarded as having perhaps the widest cove ...

. Von Neumann had claimed to show that hidden variable theories were impossible, but (as Grete Hermann

Grete Hermann (2 March 1901 – 15 April 1984) was a German mathematician and philosopher noted for her work in mathematics, physics, philosophy and education. She is noted for her early philosophical work on the foundations of quantum mechanics, ...

pointed out) his demonstration made an assumption that quantum systems obeyed a form of additivity of expectation for noncommuting operators that might not hold a priori. In 1966, John Stewart Bell

John Stewart Bell FRS (28 July 1928 – 1 October 1990) was a physicist from Northern Ireland and the originator of Bell's theorem, an important theorem in quantum physics regarding hidden-variable theories.

In 2022, the Nobel Prize in Phy ...

showed that Gleason's theorem could be used to remove this extra assumption from von Neumann's argument.

Ramsey theory

clique

A clique ( AusE, CanE, or ), in the social sciences, is a group of individuals who interact with one another and share similar interests. Interacting with cliques is part of normative social development regardless of gender, ethnicity, or popular ...

or an ''l''-vertex independent set. Ramsey numbers require enormous effort to compute; when max(''k'',''l'') ≥ 3 only finitely many of them are known precisely, and an exact computation of ''R''(6,6) is believed to be out of reach. In 1953, the calculation of ''R''(3,3) was given as a question in the Putnam Competition

The William Lowell Putnam Mathematical Competition, often abbreviated to Putnam Competition, is an annual mathematics competition for undergraduate college students enrolled at institutions of higher learning in the United States and Canada (regar ...

; in 1955, motivated by this problem,

. Gleason and his co-author Robert E. Greenwood made significant progress in the computation of Ramsey numbers with their proof that ''R''(3,4) = 9, ''R''(3,5) = 14, and ''R''(4,4) = 18. Since then, only five more of these values have been found.. In the same 1955 paper, Greenwood and Gleason also computed the multicolor Ramsey number ''R''(3,3,3): the smallest number ''r'' such that, if a complete graph

In the mathematical field of graph theory, a complete graph is a simple undirected graph in which every pair of distinct vertices is connected by a unique edge. A complete digraph is a directed graph in which every pair of distinct vertices is ...

on ''r'' vertices has its edges colored with three colors, then it necessarily contains a monochromatic triangle. As they showed, ''R''(3,3,3) = 17; this remains the only nontrivial multicolor Ramsey number whose exact value is known. As part of their proof, they used an algebraic construction to show that a 16-vertex complete graph can be decomposed into three disjoint copies of a triangle-free 5-regular graph with 16 vertices and 40 edges.

(sometimes called the Greenwood–Gleason graph).

Ronald Graham

Ronald Lewis Graham (October 31, 1935July 6, 2020) was an American mathematician credited by the American Mathematical Society as "one of the principal architects of the rapid development worldwide of discrete mathematics in recent years". He ...

writes that the paper by Greenwood and Gleason "is now recognized as a classic in the development of Ramsey theory". In the late 1960s, Gleason became the doctoral advisor

A doctoral advisor (also dissertation director, dissertation advisor; or doctoral supervisor) is a member of a university faculty whose role is to guide graduate students who are candidates for a doctorate, helping them select coursework, as well ...

of Joel Spencer

Joel Spencer (born April 20, 1946) is an American mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems.

Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, da ...

, who also became known for his contributions to Ramsey theory.

Coding theory

Gleason published few contributions to

Gleason published few contributions to coding theory

Coding theory is the study of the properties of codes and their respective fitness for specific applications. Codes are used for data compression, cryptography, error detection and correction, data transmission and data storage. Codes are studied ...

, but they were influential ones, and included "many of the seminal ideas and early results" in algebraic coding theory. During the 1950s and 1960s, he attended monthly meetings on coding theory with Vera Pless and others at the Air Force Cambridge Research Laboratory.. Pless, who had previously worked in abstract algebra

In mathematics, more specifically algebra, abstract algebra or modern algebra is the study of algebraic structures. Algebraic structures include group (mathematics), groups, ring (mathematics), rings, field (mathematics), fields, module (mathe ...

but became one of the world's leading experts in coding theory during this time, writes that "these monthly meetings were what I

lived for." She frequently posed her mathematical problems to Gleason and was often rewarded with a quick and insightful response.

The Gleason–Prange theorem

A quadratic residue code is a type of cyclic code.

Examples

Examples of quadratic

residue codes include the (7,4) Hamming code

over GF(2), the (23,12) binary Golay code

over GF(2) and the (11,6) ternary Golay code

over GF(3).

Constructions

There ...

is named after Gleason's work with AFCRL researcher Eugene Prange; it was originally published in a 1964 AFCRL research report by H. F. Mattson Jr. and E. F. Assmus Jr.

It concerns the quadratic residue code of order ''n'', extended by adding a single parity check bit. This "remarkable theorem". shows that this code is highly symmetric, having the projective linear group

In mathematics, especially in the group theoretic area of algebra, the projective linear group (also known as the projective general linear group or PGL) is the induced action of the general linear group of a vector space ''V'' on the associate ...

''PSL''2(''n'') as a subgroup of its symmetries.

Gleason is the namesake of the Gleason polynomials, a system of polynomials that generate the weight enumerators of linear code In coding theory, a linear code is an error-correcting code for which any linear combination of codewords is also a codeword. Linear codes are traditionally partitioned into block codes and convolutional codes, although turbo codes can be seen as ...

s. These polynomials take a particularly simple form for self-dual codes: in this case there are just two of them, the two bivariate polynomials ''x''2 + ''y''2 and ''x''8 + 14''x''2''y''2 + ''y''8. Gleason's student Jessie MacWilliams

Florence Jessie Collinson MacWilliams (4 January 1917 – 27 May 1990) was an English mathematician who contributed to the field of coding theory, and was one of the first women to publish in the field. MacWilliams' thesis "Combinatorial Problems ...

continued Gleason's work in this area, proving a relationship between the weight enumerators of codes and their duals that has become known as the MacWilliams identity.

In this area, he also did pioneering work in experimental mathematics

Experimental mathematics is an approach to mathematics in which computation is used to investigate mathematical objects and identify properties and patterns. It has been defined as "that branch of mathematics that concerns itself ultimately with th ...

, performing computer experiments in 1960. This work studied the average distance to a codeword, for a code related to the Berlekamp switching game.

Other areas

Gleason founded the theory ofDirichlet algebra In mathematics, a Dirichlet algebra is a particular type of algebra associated to a compact Hausdorff space ''X''. It is a closed subalgebra of ''C''(''X''), the uniform algebra of bounded continuous functions on ''X'', whose real parts are dense ...

s,

and made other contributions including work on

finite geometry

Finite is the opposite of infinite. It may refer to:

* Finite number (disambiguation)

* Finite set, a set whose cardinality (number of elements) is some natural number

* Finite verb, a verb form that has a subject, usually being inflected or marke ...

and on

the enumerative combinatorics

Enumerative combinatorics is an area of combinatorics that deals with the number of ways that certain patterns can be formed. Two examples of this type of problem are counting combinations and counting permutations. More generally, given an infin ...

of permutations.

(In 1959 he wrote that his research "sidelines" included "an intense interest in combinatorial problems.")

As well, he was not above publishing research in more elementary mathematics, such as the derivation of the set of polygons that can be constructed with compass, straightedge, and an angle trisector

Angle trisection is a classical problem of straightedge and compass construction of ancient Greek mathematics. It concerns construction of an angle equal to one third of a given arbitrary angle, using only two tools: an unmarked straightedge and ...

.

Awards and honors

In 1952 Gleason was awarded the American Association for the Advancement of Science's

In 1952 Gleason was awarded the American Association for the Advancement of Science's Newcomb Cleveland Prize The Newcomb Cleveland Prize of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is annually awarded to author(s) of outstanding scientific paper published in the Research Articles or Reports sections of ''Science''. Established in 192 ...

for his work on Hilbert's fifth problem

Hilbert's fifth problem is the fifth mathematical problem from the problem list publicized in 1900 by mathematician David Hilbert, and concerns the characterization of Lie groups.

The theory of Lie groups describes continuous symmetry in mathem ...

.

He was elected to the National Academy of Sciences and the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

, was a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

,.

and belonged to the Société Mathématique de France

Lactalis is a French multinational dairy products corporation, owned by the Besnier family and based in Laval, Mayenne, France. The company's former name was Besnier SA.

Lactalis is the largest dairy products group in the world, and is the sec ...

.

In 1981 and 1982 he was president of the American Mathematical Society

The American Mathematical Society (AMS) is an association of professional mathematicians dedicated to the interests of mathematical research and scholarship, and serves the national and international community through its publications, meetings, ...

,

and at various times held numerous other posts in professional and scholarly organizations,

including chairmanship of the Harvard Department of Mathematics.

In 1986 he chaired the organizing committee for the International Congress of Mathematicians in Berkeley, California

Berkeley ( ) is a city on the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay in northern Alameda County, California, United States. It is named after the 18th-century Irish bishop and philosopher George Berkeley. It borders the cities of Oakland and E ...

, and was president of the Congress.

In 1996 the Harvard Society of Fellows

The Society of Fellows is a group of scholars selected at the beginnings of their careers by Harvard University for their potential to advance academic wisdom, upon whom are bestowed distinctive opportunities to foster their individual and intell ...

held a special symposium honoring Gleason on his retirement after seven years as its chairman;.

that same year, the Mathematics Association of America

The Mathematical Association of America (MAA) is a professional society that focuses on mathematics accessible at the undergraduate level. Members include university, college, and high school teachers; graduate and undergraduate students; pure a ...

awarded him the Yueh-Gin Gung and Dr. Charles Y. Hu Distinguished Service to Mathematics Award.

A past president of the Association wrote:

After his death a 32-page collection of essays in the ''Notices of the American Mathematical Society'' recalled "the life and work of his

His or HIS may refer to:

Computing

* Hightech Information System, a Hong Kong graphics card company

* Honeywell Information Systems

* Hybrid intelligent system

* Microsoft Host Integration Server

Education

* Hangzhou International School, in ...

eminent American mathematician",

.

calling him "one of the quiet giants of twentieth-century mathematics, the consummate professor dedicated to scholarship, teaching, and service in equal measure."

Selected publications

;Research papers * *. *. *. *. *. *. ;Books *. Corrected reprint, Boston: Jones and Bartlett, 1991, . *. *. Unclassified reprint of a book originally published in 1957 by the National Security Agency, Office of Research and Development, Mathematical Research Division. *. Since its original publications this book has been extended to many different editions and variations with additional co-authors. ;Film *. 63 minutes, black & white. Produced by Richard G. Long and directed by Allan Hinderstein.See also

* Bell's critique of von Neumann's proof *Pierpont prime

In number theory, a Pierpont prime is a prime number of the form

2^u\cdot 3^v + 1\,

for some nonnegative integers and . That is, they are the prime numbers for which is 3-smooth. They are named after the mathematician James Pierpont, who use ...

, a class of prime number

A prime number (or a prime) is a natural number greater than 1 that is not a product of two smaller natural numbers. A natural number greater than 1 that is not prime is called a composite number. For example, 5 is prime because the only ways ...

s conjectured by Gleason to be infinite

Notes

References

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Gleason, Andrew 1921 births 2008 deaths 20th-century American mathematicians 21st-century American mathematicians American cryptographers Mathematical analysts Coding theorists Graph theorists Quantum physicists Harvard University faculty Putnam Fellows Yale University alumni Presidents of the American Mathematical Society Hollis Chair of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences People from Fresno, California Topologists Mathematicians from California United States Navy personnel of World War II