Andrei Vyshinsky on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Andrey Yanuaryevich Vyshinsky (russian: Андре́й Януа́рьевич Выши́нский; pl, Andrzej Wyszyński) ( – 22 November 1954) was a

Becoming a member of the

Becoming a member of the

In 1935, he became

In 1935, he became

In February 1945, he accompanied Stalin, Molotov, and Beria to the

In February 1945, he accompanied Stalin, Molotov, and Beria to the

He was responsible for the Soviet preparations for the trial of the major German war criminals by the International Military Tribunal.

In 1953, he was among the chief figures accused by the U.S. Congress Kersten Committee during its investigation of the Soviet occupation of the Baltic states.

The positions he held included those of vice-premier (1939–1944),

He was responsible for the Soviet preparations for the trial of the major German war criminals by the International Military Tribunal.

In 1953, he was among the chief figures accused by the U.S. Congress Kersten Committee during its investigation of the Soviet occupation of the Baltic states.

The positions he held included those of vice-premier (1939–1944),

"The Soviet Legal Narrative" - An essay by Anna Lukina about Vyshinsky as a theorist and his influence on the Nuremberg Trials and international law

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20060619201454/http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/hiss/hissvenona.html Venona transcript #1822* {{DEFAULTSORT:Vyshinsky, Andrey 1883 births 1954 deaths 20th-century jurists 20th-century Russian politicians Politicians from Odesa People from Kherson Governorate Central Executive Committee of the Soviet Union members Permanent Representatives of the Soviet Union to the United Nations Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary (Soviet Union) Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union candidate members Full Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences Moscow State University faculty Plekhanov Russian University of Economics faculty Rectors of Moscow State University Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Bolsheviks Mensheviks Soviet Ministers of Foreign Affairs First convocation members of the Soviet of the Union Second convocation members of the Soviet of the Union Fourth convocation members of the Soviet of the Union Stalin Prize winners Recipients of the Order of Lenin Recipients of the Order of the Red Banner of Labour Great Purge perpetrators Trial of the Sixteen (Great Purge) Lawyers from the Russian Empire People from the Russian Empire of Polish descent Soviet people of Polish descent Ukrainian people of Polish descent Russian prosecutors Russian revolutionaries Soviet lawyers Burials at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis

Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

politician

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking, ...

, jurist

A jurist is a person with expert knowledge of law; someone who analyses and comments on law. This person is usually a specialist legal scholar, mostly (but not always) with a formal qualification in law and often a legal practitioner. In the U ...

and diplomat

A diplomat (from grc, δίπλωμα; romanized ''diploma'') is a person appointed by a state or an intergovernmental institution such as the United Nations or the European Union to conduct diplomacy with one or more other states or interna ...

.

He is known as a state prosecutor of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

's Moscow Trials

The Moscow trials were a series of show trials held by the Soviet Union between 1936 and 1938 at the instigation of Joseph Stalin. They were nominally directed against " Trotskyists" and members of " Right Opposition" of the Communist Party o ...

and in the Nuremberg trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

. He was the Soviet Foreign Minister

The Ministry of External Relations (MER) of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) (russian: Министерство иностранных дел СССР) was founded on 6 July 1923. It had three names during its existence: People's Co ...

from 1949 to 1953, after having served as Deputy Foreign Minister under Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

since 1940. He also headed the Institute of State and Law

The Institute of State and Law (ISL) of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS) (''Russian'': Институт государства и права Российской академии наук (ИГП РАН)) is the largest scientific legal ce ...

in the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union

The Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union was the highest scientific institution of the Soviet Union from 1925 to 1991, uniting the country's leading scientists, subordinated directly to the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union (until 1946 ...

.

Biography

Early life

Vyshinsky was born inOdessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

into a Polish Catholic family which later moved to Baku

Baku (, ; az, Bakı ) is the capital and largest city of Azerbaijan, as well as the largest city on the Caspian Sea and of the Caucasus region. Baku is located below sea level, which makes it the lowest lying national capital in the world an ...

. Early biographies portray his father, Yanuary Vyshinsky (Januarius Wyszyński), as a "well-prospering" "experienced inspector" (Russian: Ревизор); while later, undocumented, Stalin-era biographies such as that in the ''Great Soviet Encyclopedia

The ''Great Soviet Encyclopedia'' (GSE; ) is one of the largest Russian-language encyclopedias, published in the Soviet Union from 1926 to 1990. After 2002, the encyclopedia's data was partially included into the later ''Bolshaya rossiyskaya e ...

'' make him a pharmaceutical chemist. A talented student, Andrei Vyshinsky married Kara Mikhailova and became interested in revolutionary ideas. He began attending the Kyiv University in 1901, but was expelled in 1902 for participating in revolutionary activities.

Vyshinsky returned to Baku, became a member of the Menshevik

The Mensheviks (russian: меньшевики́, from меньшинство 'minority') were one of the three dominant factions in the Russian socialist movement, the others being the Bolsheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries.

The factions em ...

faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP; in , ''Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (RSDRP)''), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party or the Russian Social Democratic Party, was a socialist pol ...

in 1903 and took an active part in the 1905 Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

. As a result, in 1908 he was sentenced to prison and a few days later was sent to in Baku to serve his sentence. Here he first met Stalin: a fellow-inmate with whom he engaged in ideological disputes. After his release, he returned home to Baku for the birth of his daughter Zinaida in 1909. Soon thereafter, he returned to Kyiv University and did quite well, graduating in 1913. He was even considered for a professorship, but his political past caught up with him, and he was forced to return to Baku.

Determined to practise law, he tried Moscow, where he became a successful lawyer, remained an active Menshevik, gave many passionate and incendiary speeches, and became involved in city government.

Russian Civil War

In 1917, as a minor official, he undersigned an order to arrestVladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

, according to the decision of the Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government ( rus, Временное правительство России, Vremennoye pravitel'stvo Rossii) was a provisional government of the Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately ...

, but the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

quickly intervened, and the offices which had ordered the arrest were dissolved. In 1917, he became reacquainted with Stalin, who had become an important Bolshevik leader. Consequently, he joined the staff of the People's Commissariat of Food, which was responsible for Moscow's food supplies, and with the help of Stalin, Alexei Rykov, and Lev Kamenev, he began to rise in influence and prestige. In 1920, after the defeat of the Whites

White is a racialized classification of people and a skin color specifier, generally used for people of European origin, although the definition can vary depending on context, nationality, and point of view.

Description of populations as ...

under Denikin

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (russian: Анто́н Ива́нович Дени́кин, link= ; 16 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New St ...

, and the end of the Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

, he joined the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

.

Bolsheviks in power

Becoming a member of the

Becoming a member of the nomenklatura

The ''nomenklatura'' ( rus, номенклату́ра, p=nəmʲɪnklɐˈturə, a=ru-номенклатура.ogg; from la, nomenclatura) were a category of people within the Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc countries who held various key admin ...

he became a prosecutor in the new Soviet legal system, began a rivalry with a fellow lawyer, Nikolai Krylenko

Nikolai Vasilyevich Krylenko ( rus, Никола́й Васи́льевич Крыле́нко, p=krɨˈlʲenkə; May 2, 1885 – July 29, 1938) was an Old Bolshevik and Soviet politician. Krylenko served in a variety of posts in the Soviet ...

, and in 1925 was elected rector of Moscow University

M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University (MSU; russian: Московский государственный университет имени М. В. Ломоносова) is a public research university in Moscow, Russia and the most prestigious ...

, which he began to clear of "unsuitable" students and professors.

In 1928, he presided over the Shakhty Trial

The Shakhty Trial (russian: Ша́хтинское де́ло) was the first important Soviet show trial since the case of the Socialist Revolutionary Party in 1922. Fifty-three engineers and managers from the North Caucasus town of Shakhty were ...

against 53 alleged counter-revolutionary "wreckers". Krylenko acted as prosecutor, and the outcome was never in doubt. As historian Arkady Vaksberg Arkady Iosifovich Vaksberg (Russian:Аркадий Иосифович Ваксберг) (11 November 1927 – 8 May 2011) was a Soviet and Russian lawyer, investigative journalist, writer on historical subjects, film maker and playwright. Biogr ...

explains, "all the court's attention was concentrated not on analyzing the evidence, which simply did not exist, but on securing from the accused confirmation of their confessions of guilt that were contained in the records of the preliminary investigation."

In 1930, he acted as co-prosecutor with Krylenko at another show trial, which was accompanied by a storm of propaganda. In this case, all eight defendants confessed their guilt. As a result, he was promoted.

He carried out administrative preparations for a "systematic" drive "against harvest-wreckers and grain-thieves".

Procurator General and Soviet law theorist

In 1935, he became

In 1935, he became Procurator General of the Soviet Union

The Procurator General of the USSR (russian: Генеральный прокурор СССР, Generalnyi prokuror SSSR) was the highest functionary of the Office of the Public Procurator of the USSR, responsible for the whole system of offices ...

, the legal mastermind of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

's Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

. Although he acted as a judge, he encouraged investigators to procure confessions from the accused. In some cases, he prepared the indictments before the "investigation" was concluded. In his ''Theory of Judicial Proofs in Soviet Justice'' (Stalin Prize Stalin Prize may refer to:

* The State Stalin Prize in science and engineering and in arts, awarded 1941 to 1954, later known as the USSR State Prize

The USSR State Prize (russian: links=no, Государственная премия СССР, ...

in 1947) he laid a theoretical base for the Soviet judicial system. He also used his own speeches from the Moscow Trials

The Moscow trials were a series of show trials held by the Soviet Union between 1936 and 1938 at the instigation of Joseph Stalin. They were nominally directed against " Trotskyists" and members of " Right Opposition" of the Communist Party o ...

as an example of how defendants' statements could be used as primary evidence. Vyshinsky is cited for the principle that "confession of the accused is the queen of evidence".

Vyshinsky first became a nationally known public figure as a result of the Semenchuk case of 1936. Konstantin Semenchuk was the head of the Glavsevmorput

The Chief Directorate of the Northern Sea Route (russian: Главное Управление Северного Морского Пути , translit=Glavnoe upravlenie Severnogo morskogo puti), also known as Glavsevmorput or GUSMP (russian: ГУ� ...

station on Wrangel Island

Wrangel Island ( rus, О́стров Вра́нгеля, r=Ostrov Vrangelya, p=ˈostrəf ˈvrangʲɪlʲə; ckt, Умӄиԓир, translit=Umqiḷir) is an island of the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia. It is the 91st largest island in the w ...

. He was accused of oppressing and starving the local Yupik Yupik may refer to:

* Yupik peoples, a group of indigenous peoples of Alaska and the Russian Far East

* Yupik languages, a group of Eskimo-Aleut languages

Yupꞌik (with the apostrophe) may refer to:

* Yup'ik people

The Yup'ik or Yupiaq (sg ...

and of ordering his subordinate, the sledge driver Stepan Startsev, to murder Dr. Nikolai Vulfson, who had attempted to stand up to Semenchuk, on 27 December 1934 (though there were also rumors that Startsev had fallen in love with Vulfson's wife, Dr. Gita Feldman, and killed him out of jealousy). The case came to trial before the Supreme Court of the RSFSR in May 1936; both defendants, attacked by Vyshinsky as "human waste", were found guilty and shot, and "the most publicised result of the trial was the joy of the liberated Eskimos."

In 1936, Vyshinsky achieved international infamy as the prosecutor at the Zinoviev-Kamenev trial (this trial had nine other defendants), the first of the Moscow Trials

The Moscow trials were a series of show trials held by the Soviet Union between 1936 and 1938 at the instigation of Joseph Stalin. They were nominally directed against " Trotskyists" and members of " Right Opposition" of the Communist Party o ...

during the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

, lashing its defenseless victims with vituperative rhetoric:Nicolas Werth, Karel Bartošek, Jean-Louis Panné, Jean-Louis Margolin, Andrzej Paczkowski, Stéphane Courtois

Stéphane Courtois (born 25 November 1947) is a French historian and university professor, a director of research at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), professor at the Catholic Institute of Higher Studies (ICES) in La Ro ...

, ''The Black Book of Communism

''The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression'' is a 1997 book by Stéphane Courtois, Andrzej Paczkowski, Nicolas Werth, Jean-Louis Margolin, and several other European academics documenting a history of political repression by co ...

: Crimes, Terror, Repression'', Harvard University Press

Harvard University Press (HUP) is a publishing house established on January 13, 1913, as a division of Harvard University, and focused on academic publishing. It is a member of the Association of American University Presses. After the retir ...

, 1999, , page 750

He often punctuated speeches with phrases like "Dogs of the Fascist bourgeoisie", "mad dogs of Trotskyism", "dregs of society", "decayed people", "terrorist thugs and degenerates", and "accursed vermin". This dehumanization aided in what historian Arkady Vaksberg Arkady Iosifovich Vaksberg (Russian:Аркадий Иосифович Ваксберг) (11 November 1927 – 8 May 2011) was a Soviet and Russian lawyer, investigative journalist, writer on historical subjects, film maker and playwright. Biogr ...

calls "a hitherto unknown type of trial where there was not the slightest need for evidence: what evidence did you need when you were dealing with 'stinking carrion' and 'mad dogs'?"

He is also attributed as the author of an infamous quote from the Stalin era: "Give me a man and I will find the crime."

During the trials, Vyshinsky misappropriated the house and money of Leonid Serebryakov

Leonid Petrovich Serebryakov (russian: Леонид Петрович Серебряков) (11 June 1890 – 1 February 1937) was a Russian Soviet politician and Bolshevik who became a victim of the Great Purge.

Early life

Born at Samara, the son ...

(one of the defendants of the infamous Moscow Trials), who was later executed.

Roland Freisler

Roland Freisler (30 October 1893 – 3 February 1945), a German Nazi jurist, judge, and politician, served as the State Secretary of the Reich Ministry of Justice from 1934 to 1942 and as President of the People's Court from 1942 to 1945.

As ...

, a German Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

judge, who served as the State Secretary of the Reich Ministry of Justice

''Reich'' (; ) is a German noun whose meaning is analogous to the meaning of the English word " realm"; this is not to be confused with the German adjective "reich" which means "rich". The terms ' (literally the "realm of an emperor") and ' (l ...

, studied and had attended the trials by Vyshinsky's in 1938 to use a similar approach in show trials conducted by Nazi Germany.''Hitlers Helfer - Ronald Freisler der Hinrichter'' (Hitler's Henchmen - Roland Freisler

Roland Freisler (30 October 1893 – 3 February 1945), a German Nazi jurist, judge, and politician, served as the State Secretary of the Reich Ministry of Justice from 1934 to 1942 and as President of the People's Court from 1942 to 1945.

As ...

, the Executioner), ZDF Enterprizes (1998), television documentary series, by Guido Knopp.Shirer, William, ''The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich

''The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany'' is a book by American journalist William L. Shirer in which the author chronicles the rise and fall of Nazi Germany from the birth of Adolf Hitler in 1889 to the end of World W ...

'' (Touchstone Edition) (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990)

Wartime diplomat

TheGreat Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

inflicted tremendous losses on the People's Commissariat of Foreign Affairs. Maxim Litvinov

Maxim Maximovich Litvinov (; born Meir Henoch Wallach; 17 July 1876 – 31 December 1951) was a Russian revolutionary and prominent Soviet statesman and diplomat.

A strong advocate of diplomatic agreements leading towards disarmament, Litvinov w ...

was one of the few diplomats who survived and he was dismissed. Vyshinsky had a low opinion of diplomats because they often complained about the effect of trials on opinions in the West.

In 1939, Vyshinsky entered another phase of his career when he introduced a motion to the Supreme Soviet to bring the Western Ukraine

Western Ukraine or West Ukraine ( uk, Західна Україна, Zakhidna Ukraina or , ) is the territory of Ukraine linked to the former Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia, which was part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Austr ...

into the USSR.Vaksberg, ''Stalin's Prosecutor'', 204. Afterwards, as deputy chairman of the People's Commissariat, which oversaw culture and education, as this area and others were incorporated more fully into the USSR, he directed efforts to convert the written alphabets of conquered peoples to the Cyrillic

The Cyrillic script ( ), Slavonic script or the Slavic script, is a writing system used for various languages across Eurasia. It is the designated national script in various Slavic, Turkic, Mongolic, Uralic, Caucasian and Iranic-speaking co ...

alphabet.

In June 1940 Vyshinsky was sent to Latvia

Latvia ( or ; lv, Latvija ; ltg, Latveja; liv, Leţmō), officially the Republic of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Republika, links=no, ltg, Latvejas Republika, links=no, liv, Leţmō Vabāmō, links=no), is a country in the Baltic region of ...

to supervise the establishment of a pro-Soviet government and incorporation of that country into the USSR. He was generally well received, and he set out to purge the Latvian Communist Party of Trotskyists, Bukharinites, and possible foreign agents. In July 1940, a Latvian Soviet Republic was proclaimed. It was, unsurprisingly, granted admission to the USSR. As a result of this success, he was named Deputy People's Commissar of Foreign Affairs, and taken into greater confidence by Stalin, Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria (; rus, Лавре́нтий Па́влович Бе́рия, Lavréntiy Pávlovich Bériya, p=ˈbʲerʲiə; ka, ლავრენტი ბერია, tr, ; – 23 December 1953) was a Georgian Bolshevik ...

, and Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

.

After the German invasion of the Soviet Union Vyshinsky was transferred to the shadow capital at Kuibyshev. He remained here for much of the war, but he continued to act as a loyal functionary, and attempted to ingratiate himself with Archibald Clark Kerr and visiting Republican presidential candidate Wendell Willkie

Wendell Lewis Willkie (born Lewis Wendell Willkie; February 18, 1892 – October 8, 1944) was an American lawyer, corporate executive and the 1940 Republican nominee for President. Willkie appealed to many convention delegates as the Republican ...

. During the Tehran Conference

The Tehran Conference ( codenamed Eureka) was a strategy meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill from 28 November to 1 December 1943, after the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. It was held in the Soviet Union's embass ...

in 1943, he remained in the Soviet Union to "keep shop" while most of the leadership was abroad. Stalin appointed him to the Allied Control Council

The Allied Control Council or Allied Control Authority (german: Alliierter Kontrollrat) and also referred to as the Four Powers (), was the governing body of the Allied Occupation Zones in Germany and Allied-occupied Austria after the end of ...

on Italian affairs where he began organizing the repatriation of Soviet POWs (including those who did not want to return to the Soviet Union). He also began to liaise with the Italian Communist Party in Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

.

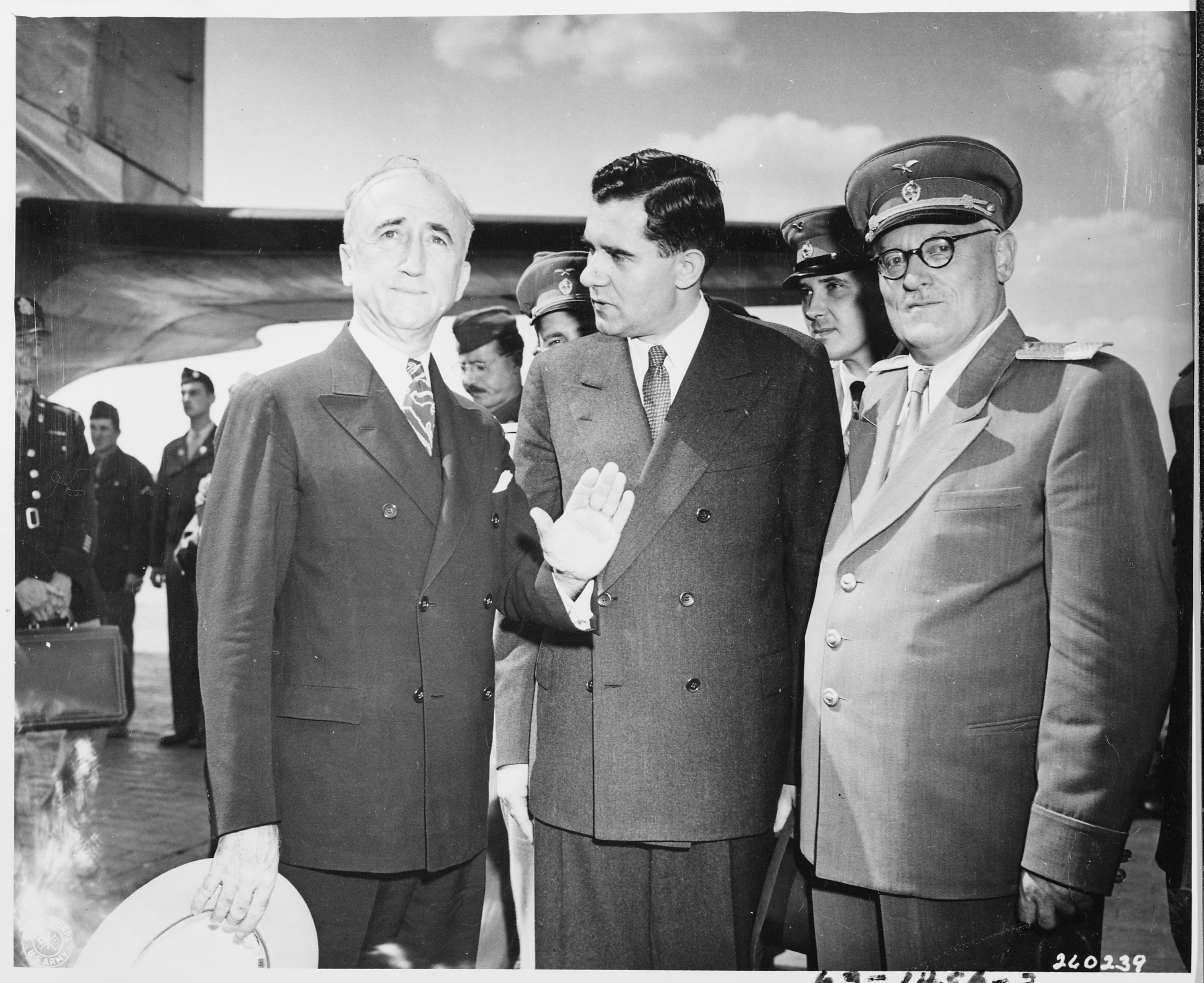

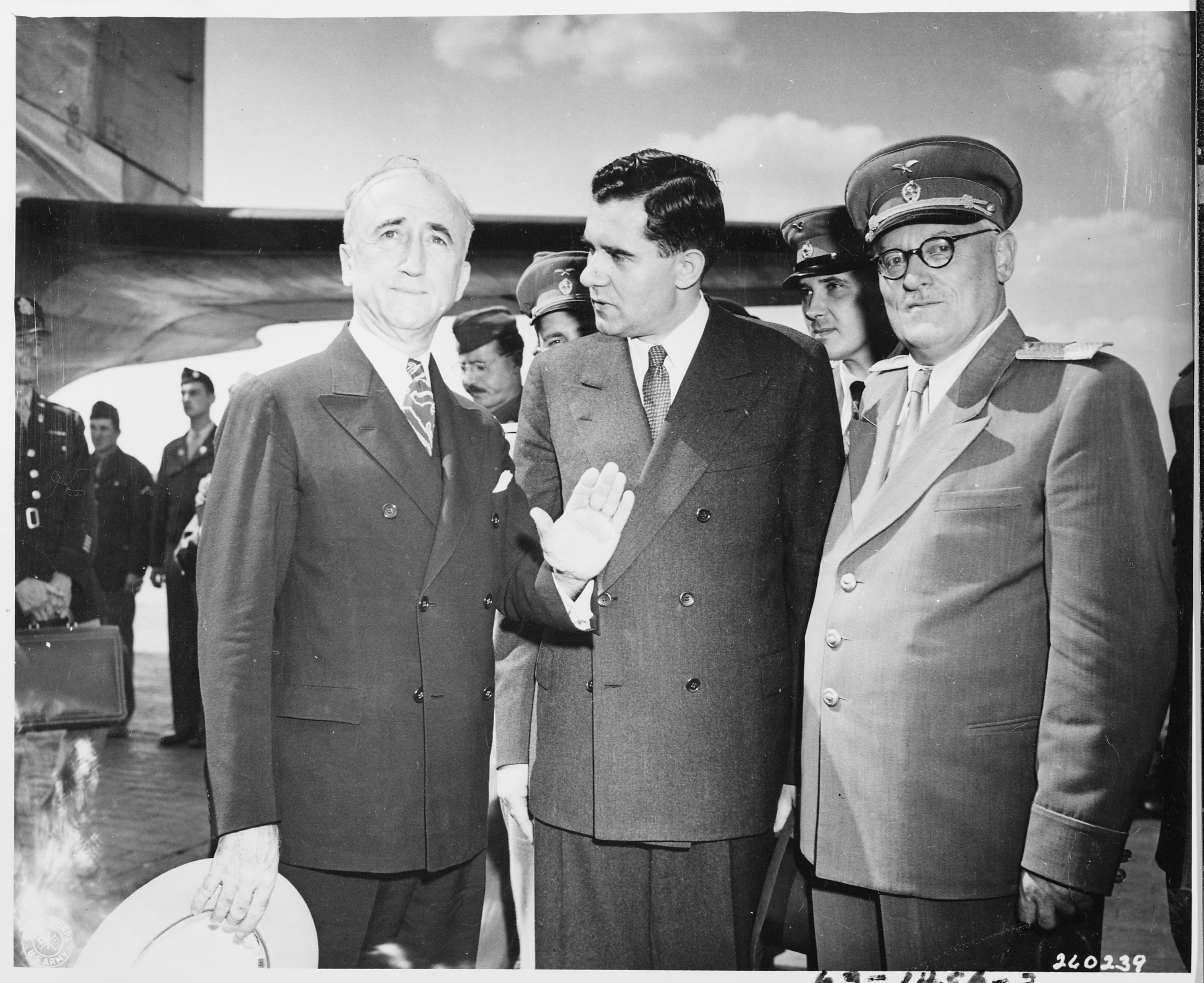

In February 1945, he accompanied Stalin, Molotov, and Beria to the

In February 1945, he accompanied Stalin, Molotov, and Beria to the Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

. After returning to Moscow he was dispatched to Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

, where he arranged for a communist regime to assume control in 1945. He then once again accompanied the Soviet leadership to the Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris P ...

.

British diplomat Sir Frank Roberts, who served as British chargé d'affaires in Moscow from February 1945 to October 1947, described him as follows:

Post-Second World War

He was responsible for the Soviet preparations for the trial of the major German war criminals by the International Military Tribunal.

In 1953, he was among the chief figures accused by the U.S. Congress Kersten Committee during its investigation of the Soviet occupation of the Baltic states.

The positions he held included those of vice-premier (1939–1944),

He was responsible for the Soviet preparations for the trial of the major German war criminals by the International Military Tribunal.

In 1953, he was among the chief figures accused by the U.S. Congress Kersten Committee during its investigation of the Soviet occupation of the Baltic states.

The positions he held included those of vice-premier (1939–1944), Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a Cabinet (government), cabinet Minister (government), minister in charge of a sovereign state, state's foreign policy and foreign ...

(1940–1949), Minister of Foreign Affairs

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between co ...

(1949–1953), academician of the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union

The Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union was the highest scientific institution of the Soviet Union from 1925 to 1991, uniting the country's leading scientists, subordinated directly to the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union (until 1946 ...

from 1939, and permanent representative of the Soviet Union to the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

.

He died of heart attack on 22 November, 1954 while in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

on a working visit and his ashes buried at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis

The Kremlin Wall Necropolis was the national cemetery for the Soviet Union. Burials in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis in Moscow began in November 1917, when 240 pro-Bolshevik individuals who died during the Moscow Bolshevik Uprising were buried in ma ...

.

Scholarship

Vyshinsky was the director of theAcademy of Sciences of the Soviet Union

The Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union was the highest scientific institution of the Soviet Union from 1925 to 1991, uniting the country's leading scientists, subordinated directly to the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union (until 1946 ...

's Institute of State and Law

The Institute of State and Law (ISL) of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS) (''Russian'': Институт государства и права Российской академии наук (ИГП РАН)) is the largest scientific legal ce ...

. Until the period of de-Stalinization

De-Stalinization (russian: десталинизация, translit=destalinizatsiya) comprised a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and the thaw brought about by ascension ...

, the Institute of State and Law was named in his honor.

During his tenure as director of the ISL, Vyshinsky oversaw the publication of several important monographs on the general theory of state and law.

Family

Vyshinsky married Kapitolina Isidorovna Mikhailova and had a daughter named Zinaida Andreyevna Vyshinskaya (born 1909).Awards and decorations

* SixOrders of Lenin

The Order of Lenin (russian: Орден Ленина, Orden Lenina, ), named after the leader of the Russian October Revolution, was established by the Central Executive Committee on April 6, 1930. The order was the highest civilian decoration b ...

(1937, 1943, 1945, 1947, 1954)

* Order of the Red Banner of Labour

The Order of the Red Banner of Labour (russian: Орден Трудового Красного Знамени, translit=Orden Trudovogo Krasnogo Znameni) was an order of the Soviet Union established to honour great deeds and services to th ...

(1933)

* Medal "For the Defence of Moscow"

The Medal "For the Defence of Moscow" (russian: Медаль «За оборону Москвы») was a World War II campaign medal of the Soviet Union awarded to military and civilians who had participated in the Battle of Moscow.

History

T ...

(1944)

* Medal "For Valiant Labour in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945"

The Medal "For Valiant Labour in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945" (russian: медаль «За доблестный труд в Великой Отечественной войне 1941–1945 гг.») was a World War II civilian labour awar ...

(1945).

* Stalin Prize Stalin Prize may refer to:

* The State Stalin Prize in science and engineering and in arts, awarded 1941 to 1954, later known as the USSR State Prize

The USSR State Prize (russian: links=no, Государственная премия СССР, ...

, first class (1947; for the monograph "Theory of forensic evidence in Soviet law")

Cultural references

ThePet Shop Boys

The Pet Shop Boys are an English synth-pop duo formed in London in 1981. Consisting of primary vocalist Neil Tennant and keyboardist Chris Lowe, they have sold more than 50 million records worldwide, and were listed as the most successful duo ...

song "This Must Be the Place I Waited Years to Leave" from the album ''Behaviour

Behavior (American English) or behaviour (British English) is the range of actions and mannerisms made by individuals, organisms, systems or artificial entities in some environment. These systems can include other systems or organisms as wel ...

'' (1990) contains a sample of recording from Vyshinsky's speech at the Zinoviev-Kamenev trial of 1936.

Vyshinsky appears at the beginning of the 2016 novel ''A Gentleman in Moscow'' by Amor Towles

Amor Towles (born 1964) is an American novelist. He is best known for his bestselling novels ''Rules of Civility'' (2011), '' A Gentleman in Moscow'' (2016), and ''The Lincoln Highway'' (2021).

Early life and education

Towles was born and rais ...

as the prosecutor in a purported transcript of an appearance by Count Alexander Ilyich Rostov, the novel's gentleman protagonist, before the Emergency Committee of the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs on 21 June 1922.

In Gregor Martov's alternative history

Alternate history (also alternative history, althist, AH) is a genre of speculative fiction of stories in which one or more historical events occur and are resolved differently than in real life. As conjecture based upon historical fact, alte ...

novel ''His New Majesty'',Published in Russian 1997, English and German translation 2002 depicting an alternate history in which Anton Denikin

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (russian: Анто́н Ива́нович Дени́кин, link= ; 16 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New St ...

's White forces defeated the Bolsheviks in 1921, Vyshinsky joins the winners and acts as the royal prosecutor in a show trial in which Lenin, Stalin, Trotsky and Bukharin are sentenced to death as "Subversives, Traitors, Blasphemers and Regicides". He is rewarded in being ennobled by the restored czar and made a duke, but gets assassinated by an anarchist girl with whom he had a secret affair.

See also

*Foreign relations of the Soviet Union

After the Russian Revolution, in which the Bolsheviks took over parts of the collapsing Russian Empire in 1918, they faced enormous odds against the German Empire and eventually negotiated terms to pull out of World War I. They then went to war ag ...

References

External links

"The Soviet Legal Narrative" - An essay by Anna Lukina about Vyshinsky as a theorist and his influence on the Nuremberg Trials and international law

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20060619201454/http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/hiss/hissvenona.html Venona transcript #1822* {{DEFAULTSORT:Vyshinsky, Andrey 1883 births 1954 deaths 20th-century jurists 20th-century Russian politicians Politicians from Odesa People from Kherson Governorate Central Executive Committee of the Soviet Union members Permanent Representatives of the Soviet Union to the United Nations Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary (Soviet Union) Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union candidate members Full Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences Moscow State University faculty Plekhanov Russian University of Economics faculty Rectors of Moscow State University Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Bolsheviks Mensheviks Soviet Ministers of Foreign Affairs First convocation members of the Soviet of the Union Second convocation members of the Soviet of the Union Fourth convocation members of the Soviet of the Union Stalin Prize winners Recipients of the Order of Lenin Recipients of the Order of the Red Banner of Labour Great Purge perpetrators Trial of the Sixteen (Great Purge) Lawyers from the Russian Empire People from the Russian Empire of Polish descent Soviet people of Polish descent Ukrainian people of Polish descent Russian prosecutors Russian revolutionaries Soviet lawyers Burials at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis