Amelia Island, Florida on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Amelia Island is a part of the Sea Islands chain that stretches along the

The Amelia Island Trail is a part of the

The Amelia Island Trail is a part of the

. Exploring Florida. Retrieved June 21, 2012. In 1562, French Huguenot explorer

Insurgencies and filibuster efforts continued.

Insurgencies and filibuster efforts continued.

''The Florida Historical Quarterly'' Vol. 71, No. 3 (Jan., 1993), pp. 279–299; via JSTOR She continued her support for education and welfare in the whole state after marrying Governor Harrison Reed of Florida in 1869. By 1872 about one-quarter of school-age children were being served by new public schools.

Nautical Chart of Amelia Island

{{authority control Atlantic Coast barrier islands of Florida Florida Sea Islands Beaches of Nassau County, Florida Seaside resorts in Florida Islands of Florida Beaches of Florida Islands of Nassau County, Florida

East Coast of the United States

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, the Atlantic Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard, is the coastline along which the Eastern United States meets the North Atlantic Ocean. The eastern seaboard contains the coa ...

from South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

to Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and ...

; it is the southernmost of the Sea Islands, and the northernmost of the barrier islands

Barrier islands are coastal landforms and a type of dune system that are exceptionally flat or lumpy areas of sand that form by wave and tidal action parallel to the mainland coast. They usually occur in chains, consisting of anything from a f ...

on Florida's Atlantic coast. Lying in Nassau County, Florida, it is long and approximately wide at its widest point. The communities of Fernandina Beach Fernandina may refer to:

*Fernandina Beach, Florida

** Original Town of Fernandina Historic Site

*Fernandina Island, Galapagos Islands

* Fernandina (fruit), a citrus

''Citrus'' is a genus of flowering trees and shrubs in the rue family, Rutac ...

, Amelia City, and American Beach are located on the island.

Geography

The Amelia Island Trail is a part of the

The Amelia Island Trail is a part of the East Coast Greenway

The East Coast Greenway is a pedestrian and bicycle route between Maine and Florida along the East Coast of the United States. In 2020, the Greenway received over 50 million visits.

The nonprofit East Coast Greenway Alliance was created in 1991. ...

, a 3,000 mile-long system of trails connecting Maine to Florida.

Airport

Fernandina Beach Municipal Airport

Fernandina Beach Municipal Airport is a city-owned public-use airport located on Amelia Island three nautical miles (6 km) south of the central business district of Fernandina Beach, a city in Nassau County, Florida, United States. It is de ...

(KFHB), a general aviation airport and former military airbase that is also now used at times by the U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

, the U.S. Coast Guard and the Florida Air National Guard

The Florida Air National Guard (FL ANG) is the aerial militia of the State of Florida. It is, along with the Florida Army National Guard (FL ARNG), an element of the Florida National Guard. It is also an element of the Air National Guard (ANG ...

, is located on the island.

History

The island was named for Princess Amelia, daughter ofGeorge II of Great Britain

George II (George Augustus; german: link=no, Georg August; 30 October / 9 November 1683 – 25 October 1760) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg (Electorate of Hanover, Hanover) and a prince-ele ...

, and changed hands between colonial powers

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their relig ...

a number of times. It is claimed that eight flags have flown over Amelia Island: French, Spanish, British, Floridian/Patriot, Green Cross, Mexican, Confederate, and United States.

Early European settlement

American Indian bands associated with theTimucua

The Timucua were a Native American people who lived in Northeast and North Central Florida and southeast Georgia. They were the largest indigenous group in that area and consisted of about 35 chiefdoms, many leading thousands of people. The v ...

people settled on the island around 1000, which they called ''Napoyca''. They remained there until the early 18th century.Florida's Historic Places: Fernandina and Amelia Island. Exploring Florida. Retrieved June 21, 2012. In 1562, French Huguenot explorer

Jean Ribault

Jean Ribault (also spelled ''Ribaut'') (1520 – October 12, 1565) was a French naval officer, navigator, and a colonizer of what would become the southeastern United States. He was a major figure in the French attempts to colonize Florida. A ...

became the first recorded European visitor to Napoyca, and he named the island ''Île de Mai''. In 1565, Spanish forces led by Pedro Menendez de Aviles

Pedro is a masculine given name. Pedro is the Spanish, Portuguese, and Galician name for '' Peter''. Its French equivalent is Pierre while its English and Germanic form is Peter.

The counterpart patronymic surname of the name Pedro, meaning ...

drove the French from northeastern Florida by attacking their stronghold at Fort Caroline

Fort Caroline was an attempted French colonial settlement in Florida, located on the banks of the St. Johns River in present-day Duval County. It was established under the leadership of René Goulaine de Laudonnière on 22 June, 1564, follow ...

on the ''Rivière de Mai'' (later called ''Río de San Juan'' by the Spanish, and later the St. Johns River in English). They killed Ribault and perhaps 350 other French colonists who had been shipwrecked further down the coast.

Spanish rule

In 1573 SpanishFranciscan

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

s established the Santa María de Sena mission on the island, which they named ''Isla de Santa María''. In the early 17th century, the Spanish relocated the Mocama

The Mocama were a Native American people who lived in the coastal areas of what are now northern Florida and southeastern Georgia. A Timucua group, they spoke the dialect known as Mocama, the best-attested dialect of the Timucua language. Thei ...

people from their former settlements to Santa María de Sena.

In 1680, British raids on St. Catherines Island

St. Catherines Island is a sea island on the coast of the U.S. state of Georgia, 42 miles (80 km) south of Savannah in Liberty County. The island, located between St. Catherine's Sound and Sapelo Sound, is ten miles (16 km) long an ...

, Georgia resulted in the Christian Guale

Guale was a historic Native American chiefdom of Mississippian culture peoples located along the coast of present-day Georgia and the Sea Islands. Spanish Florida established its Roman Catholic missionary system in the chiefdom in the late 1 ...

Indians abandoning the Santa Catalina de Guale

Santa Catalina de Guale (1602-1702) was a Spanish Franciscan mission and town in Spanish Florida. Part of Spain's effort to convert the Native Americans to Catholicism, Santa Catalina served as the provincial headquarters of the Guale mission pro ...

mission and relocating to Spanish missions on ''Isla de Santa María''. In 1702, the Spanish abandoned these missions after South Carolina's colonial governor James Moore led an invasion of Florida with British colonists and their Native American allies.

Georgia's founder and colonial governor James Oglethorpe

James Edward Oglethorpe (22 December 1696 – 30 June 1785) was a British soldier, Member of Parliament, and philanthropist, as well as the founder of the colony of Georgia in what was then British America. As a social reformer, he hoped to r ...

renamed this island as "Amelia Island" in honor of Princess Amelia (1710–1786), daughter of George II of Great Britain

George II (George Augustus; german: link=no, Georg August; 30 October / 9 November 1683 – 25 October 1760) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg (Electorate of Hanover, Hanover) and a prince-ele ...

, although it was still a Spanish possession. Oglethorpe successfully negotiated with Spanish colonial officials for the island to be transferred to British sovereignty after ordering the garrison of Scottish Highlanders to build a fort on the northwestern edge of the island. Philip V, the King of Spain, rescinded the agreement.

British rule

Oglethorpe withdrew his troops in 1742. The area became a buffer zone between the English and Spanish colonies until theTreaty of Paris (1763)

The Treaty of Paris, also known as the Treaty of 1763, was signed on 10 February 1763 by the kingdoms of Great Britain, France and Spain, with Portugal in agreement, after Great Britain and Prussia's victory over France and Spain during the S ...

settling the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

, in which Britain defeated France. Under the treaty, Spain traded Florida to Great Britain in order to regain control of Havana, Cuba

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

; the treaty nullified all Spanish land grants in Florida. The Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Proclam ...

established the St. Marys River as East Florida

East Florida ( es, Florida Oriental) was a colony of Great Britain from 1763 to 1783 and a province of Spanish Florida from 1783 to 1821. Great Britain gained control of the long-established Spanish colony of ''La Florida'' in 1763 as part of ...

's northeastern boundary.

During the early period of British rule, the island was known as Egmont Isle, after Lord Egmont who had a 10,000-acre plantation covering almost the entire island. Its headquarters were presumably the so-called "New Settlement" on the south side of the mouth of Egan's Creek adjoining the Amelia River, the site of the present-day Old Town

In a city or town, the old town is its historic or original core. Although the city is usually larger in its present form, many cities have redesignated this part of the city to commemorate its origins after thorough renovations. There are ma ...

. Egmont had only recently begun his development of the island in 1770, when Gerard de Brahm prepared his map, the "Plan of Amelia, Now Egmont Island". This depicted most of the planned development at the north end.

Egmont died in December 1770, whereupon his widow Lady Egmont assumed control of his vast Florida estates. She continued to develop the plantation and appointed Stephen Egan as her agent to manage it. With the forced labor of enslaved African Americans, he produced profitable indigo

Indigo is a deep color close to the color wheel blue (a primary color in the RGB color space), as well as to some variants of ultramarine, based on the ancient dye of the same name. The word "indigo" comes from the Latin word ''indicum'', ...

crops there. until it was destroyed by American troops from Georgia in 1776.

Spanish rule returns

In the late 1770s and early 1780s, during the American Revolutionary War, British loyalists fleeing Charleston andSavannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach the ground to ...

hastily erected new buildings at the settlement, calling their impromptu town Hillsborough. Spain regained possession of Florida in 1783, under the terms of the new United States settlement with Great Britain. Amelia harbor was an embarkation point for Loyalists leaving the colony; they tore down buildings and took the lumber with them. In June 1785, former British governor Patrick Tonyn moved his command to Hillsborough town, from which he sailed to England and evacuated troops and Loyalists later that year.

After the British evacuation, Mary Mattair, her children, and a slave worker were the sole occupants left on Amelia island. She had received a grant from Governor Tonyn of the property on the bluff overlooking the Amelia River. Following the exchange of flags in 1784, the Spanish Crown allowed Mattair to remain on the island. In trade for the earlier British grant, the Spanish authorities awarded her within the present-day city limits of Fernandina Beach. The site of Mattair's initial grant is today's Old Town Fernandina.

In 1783, the Second Treaty of Paris ended the Revolutionary War and returned Florida to Spain. British inhabitants of Florida had to leave the province within 18 months unless they swore allegiance to Spain. In June 1795, American rebel marauders led by Richard Lang attacked the Spanish garrison on Amelia Island. Colonel Charles Howard, an officer in the Spanish military, discovered that the rebels had built a battery and were flying the French flag. On August 2, he raised a sizable Spanish force, sailed up Sisters Creek and the Nassau River, and attacked them. The rebels fled across the St. Marys to Georgia.

In 1811, surveyor George J. F. Clarke

George J. F. Clarke (October 12, 1774 – 1836) was one of the most prominent and active men of East Florida (Spanish: Florida Oriental) during the Second Spanish Period. As a friend and trusted advisor of the Spanish governors of the province f ...

platted the town of Fernandina, named in honor of King Ferdinand VII of Spain by Enrique White

Enrique White (1741 - April 13, 1811) was an Irish-born Spanish soldier who served as Governor of West Florida (May 1793 – May 1795) and of East Florida (June 1796 - March 1811).

Biography

Enrique (Henry) White was born in Dublin, Ireland. ...

, the governor of the Spanish province of East Florida.

U.S.-led "Patriot War"

On March 16, 1812, Amelia Island was invaded and seized by insurgents from the United States calling themselves the " Patriots of Amelia Island," under the command of General George Mathews, a former governor of Georgia. This action was tacitly approved by President James Madison. General Mathews moved into a house at St. Marys, Georgia, just nine miles acrossCumberland Sound

Cumberland Sound (french: Baie Cumberland; Inuit: ''Kangiqtualuk'') is an Arctic waterway in Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada. It is a western arm of the Labrador Sea located between Baffin Island's Hall Peninsula and the Cumberland Peninsula ...

from Fernandina on the northwest end of the island.

That same day, nine American gunboats under the command of Commodore Hugh Campbell formed a line in the harbor and aimed their guns at the town. From Point Peter, General Mathews ordered Colonel Lodowick Ashley to send a flag to Don Justo Lopez, commandant of the fort and Amelia Island, and demand his surrender. Lopez acknowledged the superior force and surrendered the port and the town. John H. McIntosh, George J. F. Clarke, Justo Lopez, and others signed the articles of capitulation; the Patriots raised their own standard. The next day, March 17, a detachment of 250 regular United States troops were brought from Point Peter, and the newly constituted Patriot government surrendered the town to General Matthews. He took formal possession in the name of the United States, ordering the Patriot flag struck and the flag of the United States to be raised immediately.

This was part of a plan by General Mathews and President Madison to annex East Florida

East Florida ( es, Florida Oriental) was a colony of Great Britain from 1763 to 1783 and a province of Spanish Florida from 1783 to 1821. Great Britain gained control of the long-established Spanish colony of ''La Florida'' in 1763 as part of ...

, but Congress became alarmed at the possibility of being drawn into war with Spain while engaged in the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

against Great Britain. The effort fell apart when Secretary of State James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

was forced to relieve Matthews of his commission. Negotiations began for the withdrawal of U.S. troops early in 1813. On May 6, the army lowered the flag at Fernandina and took its remaining troops across the St. Marys River to Georgia. Spain seized the redoubt and regained control of the island. In 1816 the Spanish completed construction of the new Fort San Carlos to guard Fernandina.

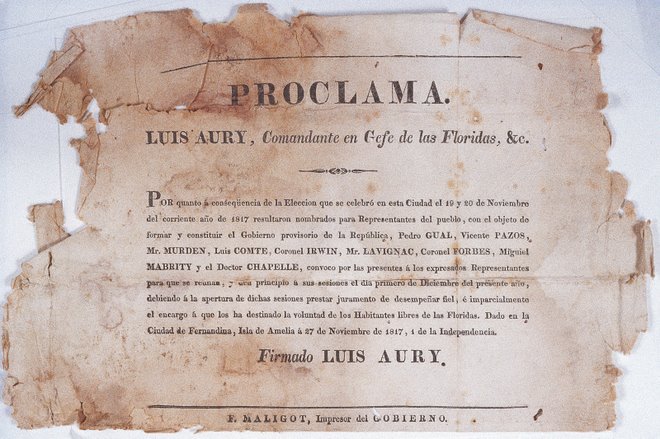

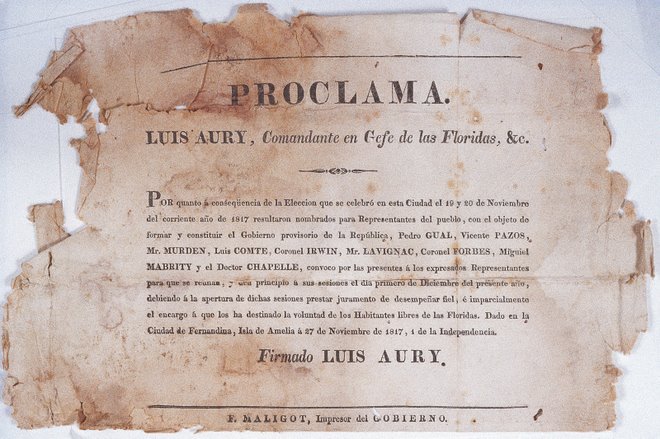

Gregor MacGregor and the Republic of the Floridas

Gregor MacGregor

General Gregor MacGregor (24 December 1786 – 4 December 1845) was a Scottish soldier, adventurer, and confidence trickster who attempted from 1821 to 1837 to draw British and French investors and settlers to "Poyais", a fictional Central A ...

, a Scottish-born soldier of fortune, led an army of 150 men, including recruits from Charleston and Savannah, some War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

veterans, and 55 musketeers, in an assault of Fort San Carlos on June 29, 1817. The commander, Francisco Morales, struck the Spanish flag and fled. MacGregor raised his flag, the "Green Cross of Florida", a green cross on a white ground, over the fort and proclaimed the "Republic of the Floridas". On September 4, faced with the threat of Spanish reprisal, and lacking money and adequate reinforcements, MacGregor abandoned his plans to conquer Florida and departed Fernandina for the Bahamas with most of his officers, leaving a small detachment of men at Fort San Carlos. The garrison and a force of American irregulars, organized by Bram Yasho and former Pennsylvania congressman Jared Irwin

Jared Irwin (1750 – March 1, 1818) served twice as elected Governor of Georgia (1796–1798) and (1806–1809). He first was elected to office as a reformer based on public outrage about the Yazoo land scandal. He signed a bill that nullifie ...

, repelled the Spanish attempt to reassert authority.

Battle of Amelia Island

On September 13 the Battle of Amelia Island started when the Spaniards erected a battery of four brass cannons on McLure's Hill east of the fort. With about 300 men, supported by two gunboats, they shelled Fernandina. Irwin's forces included ninety-four men, the privateer ships ''Morgiana'' and ''St. Joseph'', and the armed schooner ''Jupiter''. Spanish gunboats began firing at 3:30 pm and the battery on the hill joined the cannonade. The guns of Fort San Carlos, on the river bluff northwest of the hill, and those of the ''St. Joseph'' defended Amelia Island. Cannonballs killed two and wounded other Spanish troops clustered below. Firing continued until dark. The Spanish commander, convinced he could not capture the island, withdrew his forces.

French privateer Louis-Michel Aury

Hubbard and Irwin later joined forces with French-born pirateLouis-Michel Aury

Louis-Michel Aury (1788 – August 30, 1821) was a French privateer operating in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean during the early 19th century.

Early life

Louis Michel-Aury was born in Paris, France, around 1788.

French Navy

Louis Aury se ...

, who laid claim to Amelia Island supposedly on behalf of the revolutionary Republic of Mexico. He had formerly been associated with MacGregor in South American filibuster

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking out ...

adventures, Aury had also been a leader among a group of buccaneers based on Galveston Island, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

.

Aury assumed control of Amelia, creating an administrative body called the "Supreme Council of the Floridas". He directed his secretaries Pedro Gual and Vicente Pazos to draw up a constitution, and invited all of Florida to unite in throwing off the Spanish yoke. For the few months that Aury controlled Amelia Island, the flag of the revolutionary Republic of Mexico was flown. His supposed "clients" were still fighting the Spanish in their war for independence at the time.

U.S. occupation

The United States planned to annex Florida and sent a naval force, which captured Amelia Island on December 23, 1817. Aury surrendered the island to Commodore J.D. Henley and Major James Bankhead's U.S. forces on December 23, 1817. He stayed on the island more than two months as an unwelcome guest; Bankhead occupied Fernandina and PresidentJames Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

vowed to hold it "in trust for Spain". This episode in Florida's history became known as the Amelia Island Affair

The Amelia Island affair was an episode in the history of Spanish Florida.

The Embargo Act (1807) and the abolition of the American slave trade (1808) made Amelia Island, on the coast of northeastern Florida, a resort for smugglers with sometim ...

.

Spanish cession of the Floridas to the United States

Although angered by U.S. interference at Fort San Carlos, Spain ceded Florida. The proclamation of the Adams-Onis Treaty officially transferred to the United States both East Florida and what remained of Spanish claims in West Florida on February 22, 1821, two years after its signing in 1819. That was also the year that Mexico gained independence from Spain. The U.S. Army made little use of the fort and soon abandoned it. Subsequently, the island was privately developed as plantations by white planters using the labor of enslaved blacks.During the American Civil War

In the days before theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, Confederate sympathizers calling themselves the Third Regiment of Florida Volunteers took control of Fort Clinch

Fort Clinch is a 19th-century masonry coastal fortification, built as part of the Third System of seacoast defense conceived by the United States. It is located on a peninsula near the northernmost point of Amelia Island in Nassau County, Florid ...

on January 8, 1861. This was two days before Florida seceded. Located on the north end of the island, it had been under construction. Federal workers abandoned the site. Confederate General Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nor ...

visited Fort Clinch in November 1861 and again in January 1862 during a survey of coastal fortifications.

Union forces restored Federal control of the island on March 3, 1862. They had 28 gunboats commanded by Commodore Samuel Dupont

Samuel Francis Du Pont (September 27, 1803 – June 23, 1865) was a rear admiral in the United States Navy, and a member of the prominent Du Pont family. In the Mexican–American War, Du Pont captured San Diego, and was made commander of the Ca ...

. The island attracted slaves to the Union lines, where they gained freedom. By 1863 there were 1200 freedmen and their children, and 200 whites living on the island. This was one of numerous sites where freedmen congregated near Union forces.

In 1862 Secretary of War Edward M. Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814December 24, 1869) was an American lawyer and politician who served as U.S. Secretary of War under the Lincoln Administration during most of the American Civil War. Stanton's management helped organize ...

had appealed to northern abolitionists for aid in caring for the thousands of freedmen who camped near Union forces in areas of South Carolina and Florida. Among those who responded was Samuel J. May of Syracuse, New York

Syracuse ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Onondaga County, New York, United States. It is the fifth-most populous city in the state of New York following New York City, Buffalo, Yonkers, and Rochester.

At the 2020 census, the city' ...

, who organized a "Freedman's Relief Association" in the city. Funds were raised to support two teachers on Amelia Island; one was Chloe Merrick

Chloe Merrick (1832–1897) was an American educator who worked to educate and improve the welfare of freedmen and their children. She established a school on Amelia Island, Florida during and after the American Civil War. In addition to teach ...

of Syracuse. She went to the island, where she taught the freedmen, established a school and orphanage in 1863, and raised continued aid in Syracuse for clothing and supplies for the poor of the island.Sarah Whitmer Foster and John T. Foster, Jr., "Chloe Merrick Reed: Freedom's First Lady"''The Florida Historical Quarterly'' Vol. 71, No. 3 (Jan., 1993), pp. 279–299; via JSTOR She continued her support for education and welfare in the whole state after marrying Governor Harrison Reed of Florida in 1869. By 1872 about one-quarter of school-age children were being served by new public schools.

Events

Amelia Island is host to the annualIsle of Eight Flags Shrimp Festival

The Isle of Eight Flags Shrimp Festival is an annual festival held in Fernandina Beach, Florida. The first festival, which was originally referred to as the Shrimp Boat Festival, was held in 1964. The festival is normally held over the first weeke ...

(with more than 150,000 people visiting each May), the Amelia Island Jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots in blues and ragtime. Since the 1920s Jazz Age, it has been recognized as a m ...

Festival, the Amelia Island Chamber Music

Chamber music is a form of classical music that is composed for a small group of instruments—traditionally a group that could fit in a palace chamber or a large room. Most broadly, it includes any art music that is performed by a small nu ...

Festival, the Amelia Island Film

A film also called a movie, motion picture, moving picture, picture, photoplay or (slang) flick is a work of visual art that simulates experiences and otherwise communicates ideas, stories, perceptions, feelings, beauty, or atmospher ...

Festival, the automotive charitable event Amelia Island Concours d'Elegance and the Amelia Island Blues Festival. Amelia Island was the main filming location for the 2002 John Sayles

John Thomas Sayles (born September 28, 1950) is an American independent film director, screenwriter, editor, actor, and novelist. He has twice been nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, for ''Passion Fish'' (1992) and '' ...

-directed film '' Sunshine State.'' ''The New Adventures of Pippi Longstocking

''The New Adventures of Pippi Longstocking'' is a 1988 musical adventure film written and directed by Ken Annakin, based on the Pippi Longstocking book series by Astrid Lindgren. It is a Swedish-German-American joint venture produced by Columbia ...

'' was also filmed there in 1988.

Amelia Island hosted a Women's Tennis Association

The Women's Tennis Association (WTA) is the principal organizing body of women's professional tennis. It governs the WTA Tour which is the worldwide professional tennis tour for women and was founded to create a better future for women's tenn ...

tournament for 28 years (1980 to 2008). From 1987 to 2008 it was known as the Bausch & Lomb Championships

The Amelia Island Championships was a women's tennis tournament held in Amelia Island Plantation and later Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida, United States. The Women's Tennis Association event was an International series tournament played on outdoor gr ...

.

Since 2009 Amelia Island has hosted the annual Pétanque America Open of the game of pétanque

Pétanque (, ; oc, petanca, , also or ) is a sport that falls into the category of boules sports, along with raffa, bocce, boule lyonnaise, lawn bowls, and crown green bowling. In all of these sports, players or teams play their boules/balls ...

, a form of boules

''Boules'' () is a collective name for a wide range of games similar to bowls and bocce (In French: jeu or jeux, in Croatian: boćanje and in Italian: gioco or giochi) in which the objective is to throw or roll heavy balls (called in France, ...

.

Golf

Amelia Island has five golf courses: * Oak Marsh Course * Long Point Course (The Amelia Island Club) * Golf Club of Amelia Island * Amelia River Golf Club * Fernandina Beach Golf ClubReferences

External links

Nautical Chart of Amelia Island

{{authority control Atlantic Coast barrier islands of Florida Florida Sea Islands Beaches of Nassau County, Florida Seaside resorts in Florida Islands of Florida Beaches of Florida Islands of Nassau County, Florida