Amasa Stone on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

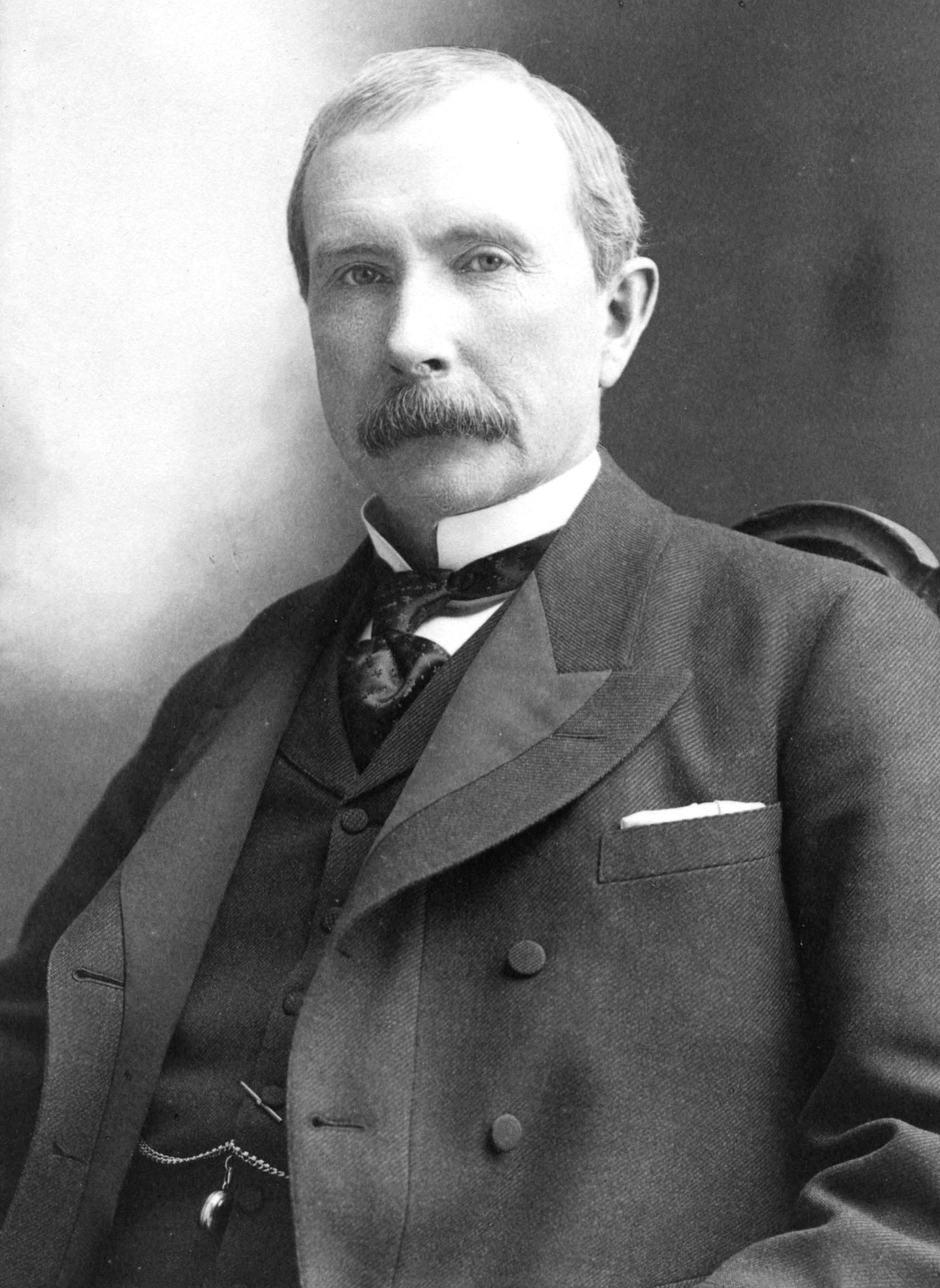

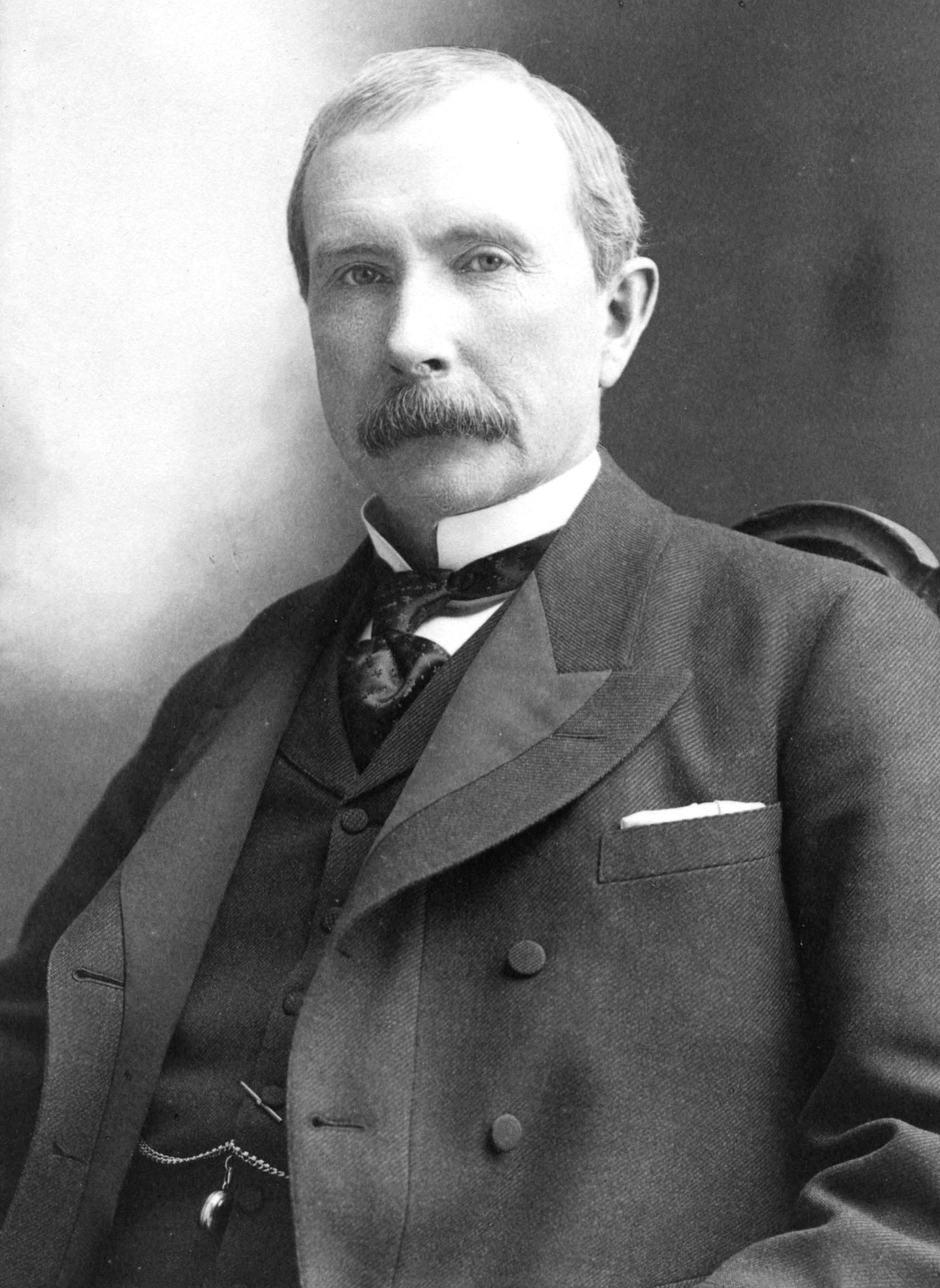

Amasa Stone, Jr. (April 27, 1818 – May 11, 1883) was an American industrialist who is best remembered for having created a regional railroad empire centered in the

Cornelius Vanderbilt waged a long and bitter war for control of the

Cornelius Vanderbilt waged a long and bitter war for control of the

The second time came in 1871. Rockefeller had long believed that overcapacity in the oil refining business would cause a crash in the price of refined oil. Anticipating the crash, on January 10, 1870, Rockefeller and his partners established a new

The second time came in 1871. Rockefeller had long believed that overcapacity in the oil refining business would cause a crash in the price of refined oil. Anticipating the crash, on January 10, 1870, Rockefeller and his partners established a new

After 1875, many of Amasa Stone's businesses suffered severe financial setbacks, and some of them failed. He suffered from

After 1875, many of Amasa Stone's businesses suffered severe financial setbacks, and some of them failed. He suffered from

At the time of his death, Amasa Stone was widely regarded by the press as the richest man in Cleveland, and modern historians have called him a nationally prominent economic leader. He was well known during his lifetime for having risen from the

At the time of his death, Amasa Stone was widely regarded by the press as the richest man in Cleveland, and modern historians have called him a nationally prominent economic leader. He was well known during his lifetime for having risen from the

Stone was the basis for a major character in John Hay's 1883 anti-

Stone was the basis for a major character in John Hay's 1883 anti-

Amasa Stone Chapel at Case Western Reserve UniversityAmasa Stone, Jr. Papers at Western Reserve Historical Society

{{DEFAULTSORT:Stone, Amasa 1818 births 1883 deaths American people in rail transportation Burials at Lake View Cemetery, Cleveland Businesspeople from Cleveland People from Charlton, Massachusetts Suicides by firearm in Ohio 19th-century American businesspeople 1880s suicides

U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its sover ...

of Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

from 1860 to 1883. He gained fame in New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

in the 1840s for building hundreds of bridges, most of them Howe truss

A Howe truss is a truss bridge consisting of chords, verticals, and diagonals whose vertical members are in tension and whose diagonal members are in compression. The Howe truss was invented by William Howe in 1840, and was widely used as a bridg ...

bridges (the patent for which he had licensed from its inventor). After moving into railroad construction in 1848, Stone moved to Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

, Ohio, in 1850. Within four years he was a director of the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad

The Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad (CC&C) was a railroad that ran from Cleveland to Columbus in the U.S. state of Ohio in the United States. Chartered in 1836, it was moribund for the first 10 years of its existence. Its charter was ...

and the Cleveland, Painesville and Ashtabula Railroad. The latter merged with the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway

The Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway, established in 1833 and sometimes referred to as the Lake Shore, was a major part of the New York Central Railroad's Water Level Route from Buffalo, New York, to Chicago, Illinois, primarily along the ...

, of which Stone was appointed director. Stone was also a director or president of numerous railroads in Ohio, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

, Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to the ...

, and Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and the ...

.

Stone played a critical role in helping the Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company, Inc., was an American oil production, transportation, refining, and marketing company that operated from 1870 to 1911. At its height, Standard Oil was the largest petroleum company in the world, and its success made its co-f ...

company form its monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek language, Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situati ...

, and he was a major force in the Cleveland banking, steel, and iron industries. Stone's reputation was significantly tarnished after the Ashtabula River

The Ashtabula River is a river located northeast of Cleveland in Ohio. The river flows into Lake Erie at the city of Ashtabula, Ohio. It is in length and drains .

Name

''Ashtabula'' derives from Lenape language ''ashte-pihële'', 'always enough ...

railroad bridge, which he designed and constructed, collapsed in 1876 in the Ashtabula River railroad disaster

The Ashtabula River railroad disaster (also called the Ashtabula horror, the Ashtabula Bridge disaster, and the Ashtabula train disaster) was the failure of a bridge over the Ashtabula River near the town of Ashtabula, Ohio, in the United Stat ...

. Stone spent many of his last years engaging in major charitable endeavors. Among the most prominent was his gift which allowed Western Reserve College (later known as Case Western Reserve University

Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) is a private research university in Cleveland, Ohio. Case Western Reserve was established in 1967, when Western Reserve University, founded in 1826 and named for its location in the Connecticut Western Reser ...

) to relocate from Hudson, Ohio

Hudson is a city in Summit County, Ohio, United States. The population was 23,110 at the 2020 census. It is a suburban community in the Akron metropolitan statistical area and the larger Cleveland–Akron–Canton Combined Statistical Area, th ...

, to Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

.

Early life

Amasa Stone, Jr. was born on April 27, 1818, on a farm nearCharlton, Massachusetts

Charlton is a town in Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 13,315 at the 2020 census.

History

Charlton was first settled in 1735. It was established as a District separated from Oxford on January 10, 1755, and b ...

, to Amasa and Esther ( Boyden) Stone. He was the ninth of 10 children, and the third of four sons. His ancestor, Gregory Stone, a yeoman

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of servants in an English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in mid-14th-century England. The 14th century also witn ...

, had emigrated from Ipswich

Ipswich () is a port town and borough in Suffolk, England, of which it is the county town. The town is located in East Anglia about away from the mouth of the River Orwell and the North Sea. Ipswich is both on the Great Eastern Main Line r ...

in Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include Lowes ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, to Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

in 1635 as part of the Puritan migration to New England. His great-grandfather, Jonathan Stone, fought at the Battle of Lexington

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. The battles were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord ...

on April 19, 1775, and in the subsequent American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

.

Stone worked on the family farm during the growing and harvest seasons, and attended local public schools when not engaged in agricultural labor. At the age of 17, Stone left the farm and moved to Worcester, Massachusetts

Worcester ( , ) is a city and county seat of Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. Named after Worcester, England, the city's population was 206,518 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the second-List of cities i ...

, where he apprenticed as a carpenter and builder with his older brother. Physically very strong, he swiftly advanced in his trade. Before he was 21 years old, he rose to the role of foreman

__NOTOC__

A foreman, forewoman or foreperson is a supervisor, often in a manual trade or industry.

Foreman may specifically refer to:

*Construction foreman, the worker or tradesman who is in charge of a construction crew

* Jury foreman, a head j ...

, and had supervised the erection of several homes in the area as well as a church in East Brookfield.

Fame as a bridge builder

Amasa Stone began working for his brother-in-law, William Howe, in 1839. The following year, Howe was engaged to build a railroad bridge over theConnecticut River

The Connecticut River is the longest river in the New England region of the United States, flowing roughly southward for through four states. It rises 300 yards (270 m) south of the U.S. border with Quebec, Canada, and discharges at Long Island ...

in Springfield, Massachusetts

Springfield is a city in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, United States, and the seat of Hampden County. Springfield sits on the eastern bank of the Connecticut River near its confluence with three rivers: the western Westfield River, the ...

. This famous bridge was of a new, influential design—the Howe truss

A Howe truss is a truss bridge consisting of chords, verticals, and diagonals whose vertical members are in tension and whose diagonal members are in compression. The Howe truss was invented by William Howe in 1840, and was widely used as a bridg ...

bridge

A bridge is a structure built to span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or rail) without blocking the way underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, which is usually somethi ...

. Howe patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A p ...

ed the design in 1840. With the financial support of Azariah Boody, a Springfield businessman, Stone purchased for $40,000 ($ in dollars) the rights to Howe's patented bridge design in 1842. That same year, the two men formed a bridge-building firm, Boody, Stone & Co., which erected a large number of Howe truss bridges throughout New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

.

Stone was named construction superintendent of the newly formed New Haven, Hartford & Springfield Railroad (NHH&S) in 1845. The demands of his construction business forced him to resign his railroad position in 1846. But later that same year, the NHH&S's bridge over the Connecticut River at Enfield Falls (near Springfield) washed out. This bridge carried much of the railroad's traffic, and its quick reconstruction was urgent. The railroad contracted with Stone to rebuild the bridge, which was long. Stone completed the work in just 40 days, much less time than most engineers believed possible. He later considered this remarkable feat the major accomplishment of his construction career. The railroad gave him $1,000 ($ in dollars) as a bonus in gratitude.

Stone dissolved Boody, Stone & Co. in late 1846 or early 1847. With Howe's business partner, Daniel L. Harris, he purchased the Howe Bridge Works (founded in 1840 by William Howe). This firm continued to construct bridges in Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

until 1849.

By the time he resettled in Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

, Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

, in 1850, Stone was known as the most eminent bridge builder and railroad contractor in New England.

Cleveland railroading

The CC&C and LS&MS

TheCleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad

The Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad (CC&C) was a railroad that ran from Cleveland to Columbus in the U.S. state of Ohio in the United States. Chartered in 1836, it was moribund for the first 10 years of its existence. Its charter was ...

(CC&C) was chartered in 1836. After several false starts at construction, in November 1848 the company finally issued a request for proposals to build the first leg of the line from Cleveland to Columbus, Ohio

Columbus () is the state capital and the most populous city in the U.S. state of Ohio. With a 2020 census population of 905,748, it is the 14th-most populous city in the U.S., the second-most populous city in the Midwest, after Chicago, and t ...

. Frederick Harbach, a surveyor

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. A land surveying professional is ca ...

and engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considering the l ...

for several Ohio railroads, surveyed the route for the new spur in 1847. Stone had worked with Harbach and another railroad engineer, Stillman Witt

Stillman Witt (January 4, 1808 — April 29, 1875) was an American railroad and steel industry executive best known for building the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad, Cleveland, Painesville and Ashtabula Railroad, and the Bellefontai ...

, while building railroad bridges in New England. Alfred Kelley

Alfred Kelley (November 7, 1789—December 2, 1859) was a Banking, banker, canal builder, lawyer, railroad executive, and state legislator in the U.S. state, state of Ohio in the United States. He is considered by historians to be one of the mo ...

, an attorney and former state legislator, canal commissioner, banker, and railroad builder, was president of the railway, and he, too, knew Stone well from his railroading days in the east. Kelley and the CC&C managers reached out to Stone, Harbach, and Witt, and asked them to bid on the project. Stone, Harbach, and Witt formed a company in late 1848 to bid on the contract, which they then won. Construction began on the line in November 1849, and the final spike was driven on February 18, 1851. Stone, Harbach, and Witt agreed to take a portion of their pay in the form of stock in the railroad. The stock soared in value as soon as the spur was completed, making Stone very wealthy.

In 1849, Stone, Harbach, and Witt also won a contract to build the Bellefontaine and Indiana Railroad. The Indiana portion of the line was finished in 1852, and the Ohio portion in July 1853.

In 1850, Stone was appointed construction superintendent of the CC&C, and he moved to Cleveland. He was named a director of the railroad in 1852.

Stone also became construction superintendent of another railroad in 1850, one that would eventually be known as the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway

The Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway, established in 1833 and sometimes referred to as the Lake Shore, was a major part of the New York Central Railroad's Water Level Route from Buffalo, New York, to Chicago, Illinois, primarily along the ...

(LS&MS). The line began in 1833 as a series of small, independent railroads which then combined into larger and larger companies. One of the first of these smaller lines was the Cleveland, Painesville and Ashtabula Railroad (CP&A), which had been chartered in 1848 to build track from Cleveland to the border with Pennsylvania. Alfred Kelley was one of its directors. On July 26, 1850, the CP&A awarded a contract to build its line to the firm of Stone, Harbach, and Witt. The line was completed in autumn 1852, and Stone was named a director of the railroad in August 1853 at a salary of $4,000 a year ($ in dollars). He continued in this position until the corporation's merger into the LS&MS in May 1869, and served as the CP&A's president from August 1858 to March 1859. While Stone served as director, the CP&A leased the Jamestown and Franklin Railroad (J&FR) in March 1864 for 20 years. He oversaw the construction of the Union Depot (named because all railroads in the city would use the same station) in Erie, Pennsylvania

Erie (; ) is a city on the south shore of Lake Erie and the county seat of Erie County, Pennsylvania, United States. Erie is the fifth largest city in Pennsylvania and the largest city in Northwestern Pennsylvania with a population of 94,831 a ...

, in 1866, and became a director of the J&FR (probably for a single year) in 1868. Stone was again elected a director of the LS&MS in August 1869, and was appointed the LS&MS' general manager in July 1873 (serving until June 1875). The railroad was in financial difficulty by mid-1873, and Stone's appointment was made in large part so that he could stabilize it. Just one month after Stone took over as general manager, he learned that the 1873 dividend (which cost $2 million) had been paid for with a loan from the Union Trust Company (a Cleveland bank). When the economy soured in August, the bank called the loan. The LS&MS almost went into receivership

In law, receivership is a situation in which an institution or enterprise is held by a receiver—a person "placed in the custodial responsibility for the property of others, including tangible and intangible assets and rights"—especially in ca ...

, but Cornelius Vanderbilt

Cornelius Vanderbilt (May 27, 1794 – January 4, 1877), nicknamed "the Commodore", was an American business magnate who built his wealth in railroads and shipping. After working with his father's business, Vanderbilt worked his way into lead ...

(another director of the road) repaid the loan out of his own funds. When his health failed in 1875, Stone resigned his position as director and general manager.

Stone remained construction superintendent of the CP&A until July 1853, and of the CC&C until 1854, when he resigned both offices (retaining his directorships) due to poor health. The following year, Stone and Witt signed a contract to clear and grade the Chicago and Milwaukee Railway The Chicago and Milwaukee Railway was a predecessor of the Chicago and North Western Railway (C&NW) in the U.S. states of Illinois and Wisconsin.

The Illinois portion was chartered on February 17, 1851, as the Illinois Parallel Railroad. Its chart ...

from Waukegan, Illinois

''(Fortress or Trading Post)''

, image_flag =

, image_seal =

, blank_emblem_size = 150

, blank_emblem_type = Logo

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_type1 = State

, subdivisi ...

, to the border with Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

. He and Witt then signed a second contract in 1858 to build the track.

Stone added another important railroad executive position when he became director of the Cleveland and Toledo Railroad in June 1859. Directorships for the road lasted a year, and Stone served one term. He was elected again in June 1863 and June 1867, and served as the company's president from January to June 1868. During his last term as director of the line (and while serving as a director of the CP&A), the CP&A leased the Cleveland & Toledo for 99 years on October 8, 1867, essentially running the railroad. On June 17, 1868, the CP&A changed its name to the Lake Shore Railway, and absorbed the Cleveland & Toledo on February 11, 1869.

Civil War

During theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

(1861 to 1864), Stone focused almost all his attention on running his railroads for the benefit of the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

war effort, and became a millionaire. He was an ardent supporter of President Abraham Lincoln, and Lincoln consulted with him on both supply and transportation issues. He became a friend of Lincoln's, and raised and supplied troops for Union cause. In 1863, Lincoln offered Stone a brigadier generalship if he would construct a military railway from Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

to Knoxville, Tennessee

Knoxville is a city in and the county seat of Knox County, Tennessee, Knox County in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 United States census, Knoxville's population was 190,740, making it the largest city in the East Tennessee Grand Di ...

. Stone turned down the generalship and persuaded the president to abandon the project (which was unfeasible and unnecessary). It was probably while visiting Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, during a trip to visit Lincoln that Stone met and became friends with Lincoln's private secretary

A private secretary (PS) is a civil servant in a governmental department or ministry, responsible to a secretary of state or minister; or a public servant in a royal household, responsible to a member of the royal family.

The role exists in t ...

, John Hay

John Milton Hay (October 8, 1838July 1, 1905) was an American statesman and official whose career in government stretched over almost half a century. Beginning as a private secretary and assistant to Abraham Lincoln, Hay's highest office was Un ...

.

It became clear during the Civil War that Cleveland's lone railroad station—a small wooden structure built in 1853 at the base of Bath Street (now Front Avenue) on the Cleveland Flats

The Flats is a mixed-use industrial, recreational, entertainment, and residential area of the Cuyahoga Valley neighborhood of Cleveland, Ohio, USA. The name reflects its low-lying topography on the banks of the Cuyahoga River.

History

In 179 ...

—was not large enough to handle the city's growing rail needs. The station burned to the ground in 1864, and Amasa Stone was tapped by the railroads to build a new station. Stone both designed and oversaw the construction of the luxurious and large Cleveland Union Depot

Union Depot was the name given to two intercity railroad stations in Cleveland, Ohio. Union Depot was built as the first union station in Cleveland in 1853. After a large fire in 1864, a new structure was built, and was the largest train station i ...

, which opened on November 10, 1866.

By 1868, Stone's annual income had risen to $70,000 a year ($ in dollars), and a few years later he owned property worth at least $5 million ($ in dollars).

Association with Cornelius Vanderbilt

Cornelius Vanderbilt waged a long and bitter war for control of the

Cornelius Vanderbilt waged a long and bitter war for control of the New York Central Railroad

The New York Central Railroad was a railroad primarily operating in the Great Lakes and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The railroad primarily connected greater New York and Boston in the east with Chicago and St. Louis in the Midw ...

from 1865 to 1867. The Central, governed by a clique of men known as the "Albany Regency", controlled most of the rail traffic outside of New York City. But Vanderbilt's Hudson River Railroad

The New York Central Railroad was a railroad primarily operating in the Great Lakes and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The railroad primarily connected greater New York and Boston in the east with Chicago and St. Louis in the Mid ...

not only had the only direct link between Albany, New York

Albany ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of New York, also the seat and largest city of Albany County. Albany is on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River, and about north of New York City ...

, and New York City, but it also had the only rail line into lower Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

. Vanderbilt won an agreement with the Central to transfer freight to his line. The contract also required the Central to pay the Hudson River Railroad $100,000 a year ($ in dollars) for keeping extra rolling stock on hand in the summer to handle the increased traffic moving north. A group of New York City investors—led by banker LeGrand Lockwood

LeGrand Lockwood (1820 – February 24, 1872), was a businessman and financier in New York City in the late 19th century. He built the Lockwood–Mathews Mansion in Norwalk, Connecticut.

Biography

Lockwood was born in Norwalk. He began his c ...

, American Express

American Express Company (Amex) is an American multinational corporation specialized in payment card services headquartered at 200 Vesey Street in the Battery Park City neighborhood of Lower Manhattan in New York City. The company was found ...

and Wells Fargo

Wells Fargo & Company is an American multinational financial services company with corporate headquarters in San Francisco, California; operational headquarters in Manhattan; and managerial offices throughout the United States and intern ...

founder William Fargo

William George Fargo (May 20, 1818August 3, 1881) was a pioneer American expressman who helped found the modern-day financial firms of American Express Company and Wells Fargo with his business partner, Henry Wells. He was also the 27th Mayor ...

, and Michigan Southern and Northern Indiana Railroad

The Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway, established in 1833 and sometimes referred to as the Lake Shore, was a major part of the New York Central Railroad's Water Level Route from Buffalo, New York, to Chicago, Illinois, primarily along the ...

president Henry Keep—decided to seek control of the Central. They quickly amassed almost two-thirds of the company's stock, and ousted the "Albany Regency". Keep, elected president of the Central, immediately revoked the yearly payment. An outraged Vanderbilt stopped carrying all Central freight. Steamboats could not move the Central's cargoes because the Hudson River frozen due to a harsh winter. Freight backed up in Albany, and New York City was effectively cut off by rail. The Central's stock price fell. In an attempt to make money off the situation, Keep borrowed a significant amount of shares to sell short

In finance, being short in an asset means investing in such a way that the investor will profit if the value of the asset falls. This is the opposite of a more conventional " long" position, where the investor will profit if the value of t ...

. Flooding the market with shares only drove the price further downward, and Vanderbilt and his allies quickly purchased these shares. This forced Keep to pay his lenders out of his own pocket, hurting him financially, and allowed the Vanderbilt group to gain control of the Central. Keep resigned, and Horace Henry Baxter was named president in December 1866. Vanderbilt exerted his power again in December 1867, and had himself named president of the Central.

Realizing that the New York Central now depended heavily on connecting lines to reach Midwestern cities like Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, Cleveland, Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at th ...

, and St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

, Vanderbilt decided to add Amasa Stone to the Central's board of directors. Stone was first appointed to the board in 1867, and probably served until December 1868. In April 1868, Stone played a major role in bringing together Cornelius Vanderbilt and the oil magnate John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American business magnate and philanthropist. He has been widely considered the wealthiest American of all time and the richest person in modern history. Rockefeller was ...

. Vanderbilt very much wanted the New York Central to carry both raw and refined oil being shipped by Rockefeller. On April 18, 1868, Vanderbilt asked Rockefeller (then visiting New York City) to meet with him. Rockefeller refused, sending only his business card

Business cards are cards bearing business information about a company or individual. They are shared during formal introductions as a convenience and a memory aid. A business card typically includes the giver's name, company or business aff ...

. He believed Vanderbilt would try to charge him high freightage rates, and Rockefeller knew he could get his oil to refineries and consumers without Vanderbilt. Vanderbilt persisted, however, and later that afternoon sent Amasa Stone to visit Rockefeller at Rockefeller's hotel. The two Clevelanders spoke for several hours, and Stone convinced Rockefeller to see Vanderbilt. The two men met that evening, and began a long and fruitful business relationship.

Vanderbilt subsequently played another critical role on Amasa Stone's railroad career. Vanderbilt wanted control of the Lake Shore Railway, which had formed out of a combination of smaller Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois railroads on March 31, 1868. In May 1868, Vanderbilt's proxies attended the first Lake Shore stockholders' meeting, and discovered that LeGrand Lockwood had a sizeable financial interest in the company. Vanderbilt was defeated in his attempt to install his own man as the Lake Shore's president. During the next several months, Lockwood worked with investor and robber baron Jay Gould

Jason Gould (; May 27, 1836 – December 2, 1892) was an American railroad magnate and financial speculator who is generally identified as one of the robber barons of the Gilded Age. His sharp and often unscrupulous business practices made hi ...

, who was engaged in the Erie War

The Erie War was a 19th-century conflict between American financiers for control of the Erie Railway Company, which owned and operated the Erie Railroad. Built with public funds raised by taxation and on land donated by public officials and priva ...

for control of the Erie Railroad

The Erie Railroad was a railroad that operated in the northeastern United States, originally connecting New York City — more specifically Jersey City, New Jersey, where Erie's Pavonia Terminal, long demolished, used to stand — with Lake Erie ...

and wanted to divert all Lake Shore traffic to the Erie. On August 19, 1869, Lockwood and Gould rammed their plan through the Lake Shore's board of directors. Vanderbilt fought them, but his only victory was in securing the election of Amasa Stone to the Lake Shore's board. Stone served until his health failed again in 1875, when he resigned.

Stone's usefulness to Vanderbilt was soon interrupted, however. On October 18, 1867, Stone and J.C. Buell, the cashier of Cleveland's Second National Bank, were hurled from their carriage after it came apart after hitting an open gutter

Gutter may refer to:

Water discharge structures

* Rain gutter, used on roofs and in buildings

* Street gutter, for drainage of streets

Design and printing

* Gutter, in typography, the space between columns of printed text

* Gutter, in bookbi ...

in Cleveland's Public Square. Stone was severely injured, and walked with a strong limp for the rest of his life. Stone went with his family to Europe to recuperate in 1868, and spent 13 months abroad. It was the first of two lengthy trips abroad for him.

LS&MS again, and other post-war railroad career

Amasa Stone had a wide range of railroad interests throughout the Midwest in the late 1860s and into the early 1880s. In 1868, he and Hiram Garrettson,Jeptha Wade

Jeptha Homer Wade (August 11, 1811 – August 9, 1890) was an American industrialist, philanthropist, and one of the founding members of Western Union Telegraph. Wade was born in Romulus, New York, the youngest of nine children of Jeptha and Sara ...

, and Stillman Witt invested in and constructed the Cleveland and Newburgh Railroad. This steam streetcar line cost $68,000 ($ in dollars) to build, and ran for down Willson Avenue (now East 55th Street) and then Kinsman Road to Newburgh (now the South Broadway neighborhood). It went bankrupt in 1878.

On July 2, 1870, the Lake Shore and Tuscarawas Valley Railway (LS&TV) was incorporated to build a railroad from Berea, Ohio

Berea ( ) is a city in Cuyahoga County in the U.S. state of Ohio and is a western suburb of Cleveland. The population was 19,093 at the 2010 census. Berea is home to Baldwin Wallace University, as well as the training facility for the Cleveland ...

, to Mill Township in Tuscarawas County, Ohio

Tuscarawas County ( ) is a county located in the northeastern part of the U.S. state of Ohio. As of the 2020 census, the population was 93,263. Its county seat is New Philadelphia. Its name is a Delaware Indian word variously translated as "ol ...

, where it would join the Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad

The Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad, commonly called the Pan Handle Route (Panhandle Route in later days), was a railroad that was part of the Pennsylvania Railroad system. Its common name came from its main line, whic ...

line. A branch to Elyria, Ohio

Elyria ( ) is a city in the Greater Cleveland metropolitan statistical area and the county seat of Lorain County, Ohio, United States, located at the forks of the Black River in Northeast Ohio 23 miles southwest of Cleveland. As of the 2020 cen ...

, was also authorized. In February 1871, Stone was among several men appointed to investigate the feasibility of constructing the line. Construction began, but the LS&TV fell into receivership in July 1874 for failing to pay the mortgage on another railroad it had acquired, and on January 30, 1875, Stone and four other investors formed the Cleveland, Tuscarawas Valley and Wheeling Railway

Cleveland, Tuscarawas Valley and Wheeling Railway operated in eastern Ohio and West Virginia from 1875 to 1882.

The Lakeshore and Tuscarawas Valley Railway Company organized by filing with the Ohio Secretary of State on July 2, 1870 to build a ro ...

(CTV&W) to take over the assets of the LS&TV. Stone was named a director of the CTV&W in 1877, serving until 1882. The CTV&W once again fell into receivership in February 1883. After a Cleveland investor purchased it, it was sold to yet another investors' group—once again led by Stone—which filed a charter on March 1, 1883, to incorporate the Cleveland, Lorain and Wheeling Railway (CL&W), which assumed the assets of the CTV&W. As before, Stone was named a director of this new road.

In 1870, at the conclusion of his 13-month trip to Europe, Stone once more was elected a director of the LS&MS. He retained this position in 1871, 1872, 1873, 1874, 1875, 1876, and 1879. Cornelius Vanderbilt became president of the Lake Shore in July 1873, and asked Stone to become managing director and ''de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with ''de jure'' ("by la ...

'' president of the railroad. Stone was managing director of the line in 1873, 1874, and 1875. The interruption in his directorship and the termination of his position as managing director occurred after he resigned due to ill health in June 1875 to go abroad for 18 months.

In 1871 and 1872, Stone was named a director of the Toledo, Wabash and Western Railway (TW&W). This road had formed in 1865 when the Toledo and Wabash Railway, Great Western Railway of Illinois, the Illinois and Southern Iowa Railroad, the Quincy and Toledo Railroad, and the Warsaw and Peoria Railroad merged. Cornelius Vanderbilt picked up large blocs of stock in the road as part of the Erie War, and the TW&W and LS&MS had effectively agreed to merge in 1869. Vanderbilt subsequently installed his strongest business associates as directors of the TW&W, which explains Stone's appointment.

Beginning in 1872, Stone played a role on three Michigan railroads as well. The first was the Northern Central Michigan Railroad, whose stock was purchased by the LS&MS in 1871. The LS&MS operated the road, and installed its own directors as directors and officers of the North Central. Beginning in 1872 and lasting to the end of 1876, Stone was a director of this road. He left the board after 1876 due to his 18-month trip in Europe. Similarly, the LS&MS purchased all the stock in and operated the Detroit, Monroe and Toledo Railroad. Stone was a director and president of this road without interruption from 1872 to his death in 1883. Finally, the LS&MS also purchased and operated the Kalamazoo and White Pigeon Railroad. Stone was a director of this road without interruption from 1872 to his death in 1883.

Beginning in 1873, Stone began playing a major role in the Mahoning Coal Railroad

The Mahoning Coal Railroad (MCR) was a railroad line in the U.S. states of Ohio and Pennsylvania. Incorporated in 1871, it largely linked Youngstown, Ohio, with Andover, Ohio. It had a major branch into Sharon, Pennsylvania, and several small bra ...

(MCR). The company incorporated in 1871 to build a line from Youngstown, Ohio

Youngstown is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio, and the largest city and county seat of Mahoning County, Ohio, Mahoning County. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, Youngstown had a city population of 60,068. It is a principal city of ...

(the location of a burgeoning steel industry) to Brookfield Township in Trumbull County, Ohio

Trumbull County is a county in the far northeast portion of U.S. state of Ohio. As of the 2020 census, the population was 201,977. Its county seat is Warren, which developed industry along the Mahoning River. Trumbull County is part of the You ...

. A branch line from Liberty Township (also located in Trumbull County) to the Ashtabula Branch of the LS&MS was also authorized. The MCR gave improved access to extensive coal mines, and its rolling stock was designed specifically to carry bulk coal. The LS&MS leased the line for 99 years beginning May 1, 1873. Stone was a director of the MCR for the rest of his life (except for the 18-month period in 1875 and 1876 when he was in Europe to regain his health).

Health issues and the Ashtabula bridge disaster

In thePanic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the "Lon ...

, Stone lost as much as $1 million ($ in dollars) making payments on loans called by desperate bankers and friends, and in financially propping up his friends and business associates. He also lost large sums of money selling stock in the LS&MS and in Western Union

The Western Union Company is an American multinational financial services company, headquartered in Denver, Colorado.

Founded in 1851 as the New York and Mississippi Valley Printing Telegraph Company in Rochester, New York, the company chang ...

at panic prices. Stone hid the extent of his financial difficulties from almost everyone, but his son-in-law John Hay believed Stone neared bankruptcy. Stone weathered the financial crisis, however, and recovered most of his wealth.

Stone's financial situation recovered enough that he was able to invest in the Mississippi Valley and Western Railway. This was a railroad (organized May 22, 1871) which merged on January 20, 1873, with the Mississippi Valley and Western Railway and the Clarksville and Western Railroad Company under the name Mississippi Valley and Western Railway. Amasa Stone invested in the new company on January 20, 1873. The railroad defaulted on its bonds, and Stone not only became a co-owner of the road but was also named a director of the line on August 7, 1874. The bankruptcy court put the railroad up for sale, and it was sold to Andros Stone on April 14, 1875. Six days later, Andros Stone sold the railroad to the St. Louis, Keokuk and North Western Railway (SLK&NW), which had been formed by Andros Stone and others to acquire the assets of the bankrupt line. In December 1879, Stone became a director of the SLK&NW. Stone remained on the board of the SLK&NW until his death.

Stone invested in another railroad, the Keokuk, Iowa City and St. Paul Railroad, in 1875. This road, which formed in 1870, still had incomplete when Stone acquired it in May 1875. A board of directors (which did not include Stone) was installed, but the railroad's history is unclear after this.

Stone began to suffer from undisclosed major health problems in the spring of 1875, and he and his wife went to Europe for 18 months beginning in late 1875. This event largely sparked Stone's retirement from most of his business ventures. While overseas, he left the management of his enterprises in the hands of his son-in-law, John Hay. During his absence, the Great Railroad Strike of 1877

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, sometimes referred to as the Great Upheaval, began on July 14 in Martinsburg, West Virginia, after the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) cut wages for the third time in a year. This strike finally ended 52 day ...

occurred, hitting his railroads hard.

While Stone was overseas in 1876, one of the greatest events in his life occurred. At 7:30 PM on December 29, the LS&MS bridge over the Ashtabula River

The Ashtabula River is a river located northeast of Cleveland in Ohio. The river flows into Lake Erie at the city of Ashtabula, Ohio. It is in length and drains .

Name

''Ashtabula'' derives from Lenape language ''ashte-pihële'', 'always enough ...

collapsed in what came to be known as the Ashtabula River railroad disaster

The Ashtabula River railroad disaster (also called the Ashtabula horror, the Ashtabula Bridge disaster, and the Ashtabula train disaster) was the failure of a bridge over the Ashtabula River near the town of Ashtabula, Ohio, in the United Stat ...

. One of two locomotives and 11 passenger railcars of the LS&MS plunged into the ice-clogged river below. The wooden cars burst into flame when their kerosene

Kerosene, paraffin, or lamp oil is a combustible hydrocarbon liquid which is derived from petroleum. It is widely used as a fuel in aviation as well as households. Its name derives from el, κηρός (''keros'') meaning "wax", and was regi ...

-fed heating stoves overturned, but rescue personnel made no attempt to extinguish the fire. The accident killed 92 people and injured 64. Amasa Stone had personally overseen both the bridge's design and its construction. He ordered the bridge built using a Howe truss design despite his chief engineer's argument that the span was too long to be safely bridged by that design. Stone later admitted that using a Howe truss for such a long span was "experimental". When bridge engineer Joseph Tomlinson III

Joseph Tomlinson III (June 22, 1816 – May 10, 1905) was an English American engineer and architect who built bridges and lighthouses in Canada and the United States. In 1868, he co-designed and oversaw the construction of the Hannibal Bridge, th ...

expressed concern that the bridge could not handle the stresses place upon it, Stone fired him. State investigators later concluded that the bridge had been improperly designed, inadequately inspected by the LS&MS, and had used faulty materials (provided by the Cleveland Rolling Mill The Cleveland Rolling Mill Company was a rolling steel mill in Cleveland, Ohio. It existed as an independent entity from 1863 to 1899.

Origins

The company stemmed from developments initiated in 1857, when John and David I. Jones, along with He ...

, which Stone's brother, Andros Stone, managed). They also found extensive evidence that the bridge had been poorly constructed: Struts were not in the correct place, braces were not tied together, and the bearings had been improperly laid. Stone categorically denied that there were any design or construction flaws. Instead, he asserted that the bridge was designed to be stronger than it needed to be.

In one of his last major railroad positions, Stone briefly became a director of two railroads, the Massillon and Cleveland Railroad and the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne and Chicago Railway

The Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne and Chicago Railway was a major part of the Pennsylvania Railroad system, extending the PRR west from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, via Fort Wayne, Indiana, to Chicago, Illinois. It included the current Norfolk Southern-own ...

, in early 1883.

Standard Oil

Twice, Amasa Stone proved crucial to the success of John D. Rockefeller's oil refining career.The 1868 secret rebate agreement

The first time came in 1868. On March 4, 1867, John D. Rockefeller, his brotherWilliam Rockefeller

William Avery Rockefeller Jr. (May 31, 1841 – June 24, 1922) was an American businessman and financier. Rockefeller was a co-founder of Standard Oil along with his elder brother John Davison Rockefeller. He was also part owner of the Anaconda ...

, chemist Samuel Andrews, and businessman Henry Flagler

Henry Morrison Flagler (January 2, 1830 – May 20, 1913) was an American industrialist and a founder of Standard Oil, which was first based in Ohio. He was also a key figure in the development of the Atlantic coast of Florida and founde ...

formed the oil refining

An oil refinery or petroleum refinery is an industrial process plant where petroleum (crude oil) is transformed and refined into useful products such as gasoline (petrol), diesel fuel, asphalt base, fuel oils, heating oil, kerosene, liquefie ...

firm of Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler

Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler was a business concern formed in 1867 in Cleveland, Ohio which was a predecessor of the Standard Oil Company. The principals and namesakes were John D. Rockefeller, William Rockefeller, Samuel Andrews, and Henry M. ...

. (Flagler's step-brother, the liquor magnate Stephen V. Harkness, was a silent partner.) Transportation costs were the key to making oil cheaply available to consumers, and cheap oil meant more market share (and more profit). For Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler, the question was how to get its refined oil to East Coast

East Coast may refer to:

Entertainment

* East Coast hip hop, a subgenre of hip hop

* East Coast (ASAP Ferg song), "East Coast" (ASAP Ferg song), 2017

* East Coast (Saves the Day song), "East Coast" (Saves the Day song), 2004

* East Coast FM, a ra ...

cities. At the time, the railroads were engaged in cutthroat competition for refined oil. Rate-cutting was common (with railways often losing money on shipments). Each road also attempted to win more oil freight business by rapidly building up its supply of tank car

A tank car ( International Union of Railways (UIC): tank wagon) is a type of railroad car (UIC: railway car) or rolling stock designed to transport liquid and gaseous commodities.

History

Timeline

The following major events occurred in t ...

s, but this left the railroads with an oversupply of cars, which lost them even more money. In 1868, Rockefeller formed a consortium of Cleveland-area refining companies. The consortium agreed to pool their shipments to the East Coast if lower freight rates could be procured. On behalf of the consortium, Henry Flagler reached an agreement with Stone's Lake Shore & Michigan Southern: The consortium would guarantee at least 60 tank cars of refined oil every day, in return for which the LS&MS would cut shipping rates by 30 percent (e.g., offer a "rebate"). The consortium agreed not to ship oil with any other railway unless the LS&MS could not take the oil, and the LS&MS agreed not to offer a rebate to any other refiners unless they could provide at least 60 tank cars of oil a day (which none of them could). Stone quickly agreed to the plan, which greatly enhanced Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler's market share.

The 1871-1872 South Improvement Company conspiracy

The second time came in 1871. Rockefeller had long believed that overcapacity in the oil refining business would cause a crash in the price of refined oil. Anticipating the crash, on January 10, 1870, Rockefeller and his partners established a new

The second time came in 1871. Rockefeller had long believed that overcapacity in the oil refining business would cause a crash in the price of refined oil. Anticipating the crash, on January 10, 1870, Rockefeller and his partners established a new joint-stock company

A joint-stock company is a business entity in which shares of the company's capital stock, stock can be bought and sold by shareholders. Each shareholder owns company stock in proportion, evidenced by their share (finance), shares (certificates ...

, Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company, Inc., was an American oil production, transportation, refining, and marketing company that operated from 1870 to 1911. At its height, Standard Oil was the largest petroleum company in the world, and its success made its co-f ...

. Just 10,000 shares of Standard Oil were created. John and William Rockefeller, Flagler, Harkness, and Andrews took almost all the shares. A new investor, Oliver B. Jennings (William Rockefeller's brother-in-law), invested $100,000 in the new company and was given 1,000 shares. The old company of Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler was given 1,000 shares as a reserve. The stock was set at a $100 per share par value

Par value, in finance and accounting, means stated value or face value. From this come the expressions at par (at the par value), over par (over par value) and under par (under par value).

Bonds

A Bond_(finance), bond selling at par is priced at 1 ...

($ in dollars), and Standard Oil paid a 105 percent dividend

A dividend is a distribution of profits by a corporation to its shareholders. When a corporation earns a profit or surplus, it is able to pay a portion of the profit as a dividend to shareholders. Any amount not distributed is taken to be re-in ...

in 1870 and 1871. The overcapacity crash hit in 1871, and many refiners neared bankruptcy. In the fall of 1871, Rockefeller learned of a conspiracy being promoted by Thomas A. Scott (First Vice President of the Pennsylvania Railroad

The Pennsylvania Railroad (reporting mark PRR), legal name The Pennsylvania Railroad Company also known as the "Pennsy", was an American Class I railroad that was established in 1846 and headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was named ...

) and Peter H. Watson (then a director of the LS&MS). On November 30, 1871, Rockefeller met with Scott and Watson at the St. Nicholas Hotel in New York City, where Scott outlined his plan: Using a vaguely-worded corporate charter he had obtained from the Pennsylvania General Assembly

The Pennsylvania General Assembly is the legislature of the U.S. commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The legislature convenes in the State Capitol building in Harrisburg. In colonial times (1682–1776), the legislature was known as the Pennsylvania ...

, the Pennsylvania Railroad, the New York Central Railroad, the Erie Railroad, Standard Oil, and a few small oil refining companies would create and invest in the South Improvement Company

The South Improvement Company was a short lived Pennsylvania corporation founded in late 1871 which existed until the state of Pennsylvania suspended its charter on April 2, 1872. It was created by major railroad and oil interests, and was widely ...

(SIC). The SIC's participating railroads would give the SIC's investor-refiners a 50 percent rebate on oil shipments, helping them to drive competitors out of business. Additionally, any time the SIC carried the oil of a non-participating refiner, the SIC would give a 40-cents-per-barrel payment ($ in dollars) to the investor-refiners. The SIC would also provide the investor-refiners with information on the shipments of their competitors, giving them a critical advantage in pricing and sales.

Rockefeller saw the SIC as the ideal mechanism for achieving another goal: A monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek language, Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situati ...

on oil refining in Cleveland. Once the SIC had severely weakened his competitors, Standard Oil would buy out the city's 26 major oil refining companies at fire-sale prices. The monopoly would allow Standard Oil to dominate the national refining market, garner significantly higher profits, and drive competitors out of business. With higher profits, Standard Oil could then rapidly expand, becoming even more dominant. To make the purchases, Standard Oil needed cash. To secure the cash, Rockefeller allowed Amasa Stone, Stillman Witt, Benjamin Brewster, and Truman P. Handy—all of whom were officers in Cleveland banks—to buy shares in Standard Oil at par in December 1871. Stone and the other bankers used their influence at their own and other banks to give Rockefeller the financial backing he needed. Stone now owned the equivalent of 5 percent of the entire outstanding stock of Standard Oil.

The SIC conspiracy collapsed in March 1872, but between February 17 and March 28, 1872, Rockefeller was able to buy out 22 of the 26 major refiners in Cleveland, an event which historians call "the Cleveland Massacre". Stone played a major part in the success of the event. Rockefeller knew that if he bought out the weak refiners first, he'd generate opposition and never get a chance to take on the larger, more profitable ones. So he tackled his strongest competitor, the firm of Clark, Payne & Co., led by Oliver Hazard Payne

Oliver Hazard Payne (July 21, 1839 – June 27, 1917) was an American businessman, organizer of the American Tobacco trust, and assisted with the formation of U.S. Steel, and was affiliated with Standard Oil.

Early life

Oliver Hazard Payne was ...

and backed by the wealthy J. G. Hussey family. In December 1871, Rockefeller asked Payne to meet him at the Second National Bank in Cleveland to discuss business matters in which the bank had an interest. Stone and Stillman Witt were both officers in the bank. Payne swiftly agreed to a merger of his interests with Rockefeller's, and the transaction closed in early January 1872.

Events moved so quickly that additional capital was needed, and Rockefeller felt that the Cleveland banks could not be counted on to keep his loan requests confidential. On January 2, 1872, Standard Oil issued 4,000 new shares of stock in the form of a dividend. Stock was issued on a pro rata basis, which gave Stone another 200 shares. Later that same day, another issue of stock was made. This constituted 11,000 shares, of which 3,000 were given to John D. Rockefeller, 1,400 to Henry Flagler, 4,000 to the owners of Clark, Payne and Company (one of the largest oil refineries in Cleveland), 700 to refiner Jabez A. Bostwick, 200 to refiner Joseph Stanley, and 500 to Peter Watson (who by now was the president of the SIC). Another 1,200 shares were given to John D. Rockefeller to retain as a reserve. On January 2, 1872, a third new issue of 10,000 shares occurred, and was given to Rockefeller to hold in reserve. Although these new issues had diluted Stone's investment to just 2 percent of Standard Oil's stock, it was enough to give him a strong financial interest in the company and to allow John D. Rockefeller to tighten his influence over railroads Stone directed.

To further encourage Stone to meet the needs of Standard Oil, Rockefeller put Stone on the Standard Oil board of directors in 1871. By 1872, Amasa Stone's personal fortune was worth an estimated $6 million ($ in dollars).

Break with Rockefeller

Stone's association with Standard Oil did not last past mid-1872. The break came when Rockefeller approached the Second National Bank, of which Stone was a director, for a major loan in early 1872. Stone expected the much younger Rockefeller to be deferential and suppliant, but he was not. Stone angrily opposed the loan during a bank board of directors meeting. After Rockefeller made his case to the board, Stone suggested that Payne and Witt arbitrate the dispute. The two officers voted to support Rockefeller. The relationship between Stone and Rockefeller deteriorated swiftly, and Stone repeatedly snubbed Rockefeller socially. Like other directors, Stone had been given an option to buy additional Standard Oil shares. About June 1872, this option expired without Stone having acted to buy the new shares. Stone then asked Henry Flagler to change the expiration date so he could purchase the shares. Flagler did so, but Rockefeller overruled Flagler when he learned about the change. Flagler argued that Stone's support was useful, and that he should be placated. Rockefeller disagreed, saying that he saw no reason to "truckle" to Stone. In a fit of pique, Stone sold all his Standard Oil shares, making him ineligible to continue serving on the board. Rockefeller never regretted his actions. He later said that he "probably saved two or three million dollars" in profit by getting rid of Stone. On July 30–31, 1872, Standard Oil's terminal at Hunters Point, New York, suffered a devastating fire. With the company's insurer refusing to pay until after an investigation, Standard Oil was in desperate need for cash to rebuild. The officers of the company asked Rockefeller to seek a loan from the Second National Bank. At a meeting between Rockefeller and the bank's directors, Stone demanded that Standard Oil be appraised and its financial condition assessed before any loan was issued. Offended, Stillman Witt approved the loan, and Stone was stymied.United Pipe Lines

Stone had one more interaction with Rockefeller and Standard Oil. Standard Oil relied on its rebate deals with the railroads to get its oil to market. Two companies, Vandergrift & Forman and the American Transfer Company, now threatened that arrangement by announcing the construction of pipelines from the western Pennsylvania oilfields to New York City.William H. Vanderbilt

William Henry Vanderbilt (May 8, 1821 – December 8, 1885) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He was the eldest son of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, an heir to his fortune and a prominent member of the Vanderbilt family. Vanderbi ...

, Cornelius Vanderbilt's son and vice-president of the New York Central Railroad, saw the threat as well. In 1873, Amasa Stone and William H. Vanderbilt attempted to gain control of Vandegrift & Forman, each taking a one-sixth interest in the firm. Rockefeller purchased a one-third share, and the company was renamed United Pipe Lines. Rockefeller then purchased American Transfer, effectively blocking Stone and Vanderbilt from gaining control of the emerging pipeline industry. Standard Oil eventually formed a new company, United Pipe-Lines, in 1877 and merged both United and American Transfer into the new firm. Although Stone held more than 1,000 shares of the new company, his ownership interest was small compared to that held by Rockefeller and others.

Banking and other roles

Banking and finance

Stone's interest in industries and services other than railroads emerged early after he moved to Cleveland. In 1856, Stone—along with Hinman Hurlbut, Stillman Witt, Joseph Perkins, James Mason, Henry Perkins,Morrison Waite

Morrison Remick "Mott" Waite (November 29, 1816 – March 23, 1888) was an American attorney, jurist, and politician from Ohio. He served as the seventh chief justice of the United States from 1874 until his death in 1888. During his tenur ...

, and Samuel Young—purchased the Toledo Branch of the State Bank of Ohio. Stone served as the bank's president from 1857 probably to 1864. The Toledo Branch was reorganized as a national bank in 1866.

Stone then helped organize the Cleveland Banking Company in 1863 with Stillman Witt, George A. Garretson

George Armstrong Garretson (January 30, 1844 – December 8, 1916) enlisted as private in the Union Army during the American Civil War, Civil War and later graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York. He returned to duty for t ...

, Jeptha Wade, and George B. Ely, and was elected to its first board of directors. It merged with the Second National Bank in 1868, and Stone was elected president of the successor bank in January 1873. He resigned in January 1874.

Stone helped reorganize the Commercial Bank on March 1, 1865, after its initial 20-year charter expired. Rechartered as the Commercial National Bank, Stone was elected a director of the bank and in 1879 served as its vice president. Stone was also a director of the Bank of Commerce (although just when he became a director is not clear). He was elected president of the bank in 1873, but resigned in late 1874 and was replaced by Hiram Garretson. He was also a director of the Merchants Bank (although the dates of his service are not clear).

Metals manufacturing

Stone's interests also extended heavily into metallurgy and metals manufacturing. In 1863, Stone, George B. Ely, and others helped organize the Mercer Iron & Coal Company inMercer County, Pennsylvania

Mercer County is a county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. As of the 2020 census, the population was 110,652. Its county seat is Mercer, and its largest city is Hermitage. The county was created in 1800 and later organized in 1803.

Merce ...

. Stone was named a director of the company, and later its president (although the date of this latter service is not clear). Stone also co-founded the Union Iron Company (later Union Iron & Steel Co.) in Chicago with his brother, Andros Stone, and mining magnate Jay C. Morse. Stone loaned his brother $800,000 ($ in dollars) to organizer the business.

A third steel mill organized by Stone was the Cleveland Rolling Mill The Cleveland Rolling Mill Company was a rolling steel mill in Cleveland, Ohio. It existed as an independent entity from 1863 to 1899.

Origins

The company stemmed from developments initiated in 1857, when John and David I. Jones, along with He ...

(later known as the American Steel & Wire Co.), which was organized on November 9, 1863. The firm was established in 1857 as Chisholm, Jones and Company, and in 1860 the company was reorganized as Stone, Chisholm & Jones after the family-run business received major investments from Amasa Stone, Henry Chisholm

Henry Chisholm (April 22, 1822 – May 9, 1881) was a Scottish American businessman and Steel#Steel industry, steel industry executive during the Gilded Age in the United States. A resident of Cleveland, Ohio, he purchased a small, struggling iron ...

, Andros Stone, Stillman Witt, Jeptha Wade, and Henry B. Payne

Henry B. Payne (November 30, 1810September 9, 1896) was an American politician from Ohio. Moving to Ohio from his native New York in 1833, he quickly established himself in law and business while becoming a local leader in Democratic politics. ...

. Andros Stone managed the firm. It changed its name to the Cleveland Rolling Mill Company, purchased the Cleveland Wire Mill Co. in 1866, and obtained control of the Union Rolling Mill Co. of Chicago in 1871. At some point, Stone also invested a substantial sum in the Kansas City Rolling Mill Company of Kansas City, Missouri

Kansas City (abbreviated KC or KCMO) is the largest city in Missouri by population and area. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 508,090 in 2020, making it the 36th most-populous city in the United States. It is the central ...

.

Stone then founded the Union Steel Screw Company in 1872 with Andros Stone, William Chisholm, Henry Chisholm, and Henry B. Payne. The factory, which was located at Case and Payne Avenues in Cleveland, was the only one in the United States making steel wood screws at that time.

In January 1881, Stone and others provided financial assistance to veteran brass

Brass is an alloy of copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn), in proportions which can be varied to achieve different mechanical, electrical, and chemical properties. It is a substitutional alloy: atoms of the two constituents may replace each other with ...

manufacturer Joel Hayden, Jr. in establishing the Joel Hayden Brass Works in Lorain, Ohio

Lorain () is a city in Lorain County, Ohio, United States. The municipality is located in northeastern Ohio on Lake Erie, at the mouth of the Black River, about 30 miles west of Cleveland. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 65 ...

.

About 1875, Stone also invested $500,000 in the new iron foundry of Brown, Bonnell & Co. of Youngstown, Ohio

Youngstown is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio, and the largest city and county seat of Mahoning County, Ohio, Mahoning County. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, Youngstown had a city population of 60,068. It is a principal city of ...

. He was placed on the board of directors of the firm (although the date of his departure from the board is unclear).

Other business ventures

Stone had a number of other business interests and ventures in addition to banking and metallurgy. Immediately upon his arrival in Cleveland in 1850, Stone created the Cleveland Stone Dressing Company withParker Handy

Parker Handy (April 24, 1809 – April 8, 1890) was an American banker who was "one of the best known dealers in bullion and specie" in New York City.

Early life

Handy was born in Paris Hill in Oneida County, New York on April 24, 1809. He was a ...

, J.P. Bishop, William E. Beckwith, F.T. Backus, J.H. Morley, H.K. Raynolds, Reuben Hitchcock, and John Case. The company bought large stone quarries in Berea (the "old Eldridge quarry") and Independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

, and built a small railroad to ship the stone to Cleveland. There, they established a stoneyard on west bank of Cuyahoga River, and dredged the river to make it navigable to ships carrying their dressed stone. Cleveland Stone Dressing furnished stone for a number of large mansions in Cleveland; the First Presbyterian Church of East Cleveland; the Ontario Legislative Building

The Ontario Legislative Building (french: L'édifice de l'Assemblée législative de l'Ontario) is a structure in central Toronto, Ontario, Canada. It houses the Legislative Assembly of Ontario, and the viceregal suite of the Lieutenant Governor ...

in Toronto, Ontario

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the ancho ...

, Canada; and the residence of Senator Henry B. Payne. The firm closed in 1854 due to lack of demand. The stoneyard was later taken over by Rhodes & Co., a major coal distributor.

Other business interests included a Cleveland woolen mill (established in 1861), and a position on the board of directors of the Buckeye Insurance Company (which he held in 1869). On February 26, 1870, Stone, Jeptha Wade, Worthy S. Streator, J.P. Robinson, and others formed the Northern Ohio Fair after the state refused to allow the Ohio State Fair

The Ohio State Fair is one of the largest state fairs in the United States, held in Columbus, Ohio during late July through early August. As estimated in a 2011 economic impact study conducted by Saperstein & Associates; the State Fair contributes ...

to be hosted by the city of Cleveland. The group purchased of land on St. Clair Avenue in the Glenville neighborhood and erected fair buildings there. Stone served as the fair's first president. In 1877, Stone dabbled in real estate by constructing a building on St. Clair Avenue in Cleveland's Warehouse District. The structure housed the Koch, Goldsmith, Joseph & Company clothing firm, which later (as The Joseph and Feiss Company

''The'' () is a grammatical Article (grammar), article in English language, English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite ...

) became one of the largest clothing retailers in the nation.

Both historic and modern sources say that Amasa Stone also invested in a wide range of factories, including those which manufactured automobiles, railroad car

A railroad car, railcar (American and Canadian English), railway wagon, railway carriage, railway truck, railwagon, railcarriage or railtruck (British English and UIC), also called a train car, train wagon, train carriage or train truck, is a ...

s, and bridges.

Stone also had a position on the board of directors of the Western Union

The Western Union Company is an American multinational financial services company, headquartered in Denver, Colorado.

Founded in 1851 as the New York and Mississippi Valley Printing Telegraph Company in Rochester, New York, the company chang ...

telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

company. Jeptha Wade had been president of Western Union in 1866, and Stone may have invested at this time in the company. By 1880, Cornelius Vanderbilt was a major investor in the firm, and was even rumored to have a controlling interest in it. It was Vanderbilt who had Stone appointed to Western Union's board of directors in 1881. Stone served on the board until his death in 1883.

Death

After 1875, many of Amasa Stone's businesses suffered severe financial setbacks, and some of them failed. He suffered from

After 1875, many of Amasa Stone's businesses suffered severe financial setbacks, and some of them failed. He suffered from stomach ulcers

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is a break in the inner lining of the stomach, the first part of the small intestine, or sometimes the lower esophagus. An ulcer in the stomach is called a gastric ulcer, while one in the first part of the intestines ...

which often kept him awake for two hours each night. It was widely believed by the public that the Ashtabula River railroad disaster

The Ashtabula River railroad disaster (also called the Ashtabula horror, the Ashtabula Bridge disaster, and the Ashtabula train disaster) was the failure of a bridge over the Ashtabula River near the town of Ashtabula, Ohio, in the United Stat ...

had deeply affected Stone emotionally, causing his health to worsen after 1876.

By 1882, Stone was suffering from insomnia

Insomnia, also known as sleeplessness, is a sleep disorder in which people have trouble sleeping. They may have difficulty falling asleep, or staying asleep as long as desired. Insomnia is typically followed by daytime sleepiness, low energy, ...

. That year, his son-in-law, John Hay, took his wife, Clara Stone Hay, on a long-delayed 18-month honeymoon to Europe. Hay biographer Patricia O'Toole

Patricia O'Toole is an American historian who taught at Columbia University. She is a Society of American Historians fellow and was a visitor at the Institute for Advanced Study

The Institute for Advanced Study (IAS), located in Princeton, ...