Alto-Alentejano on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Portuguese ( or, in full, ) is a western Romance languages, Romance language of the Indo-European language family, originating in the Iberian Peninsula of Europe. It is an official language of Portugal, Brazil, Cape Verde, Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau and Sأ£o Tomأ© and Prأncipe, while having co-official language status in East Timor, Equatorial Guinea, and Macau. A Portuguese-speaking person or nation is referred to as "Lusophone" (). As the result of expansion during colonial times, a cultural presence of Portuguese speakers is also found around the world. Portuguese is part of the Iberian Romance languages, Ibero-Romance group that evolved from several dialects of Vulgar Latin in the medieval Kingdom of Galicia and the County of Portugal, and has kept some Gallaecian language, Celtic phonology in its lexicon.

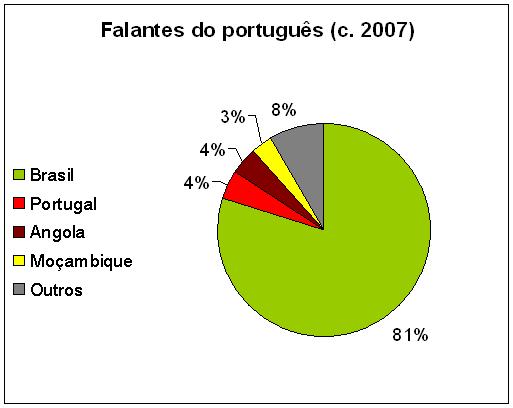

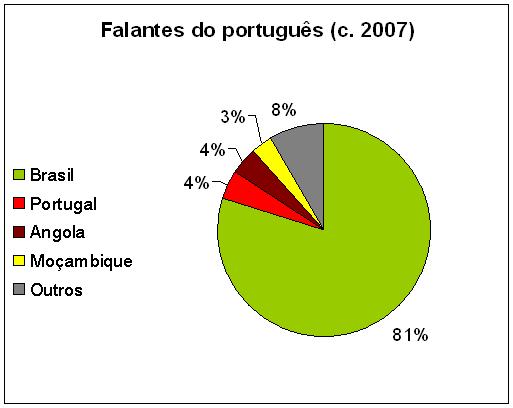

With approximately 250 million native speakers and 24 million L2 (second language) speakers, Portuguese has approximately 274 million total speakers. It is usually listed as the List of languages by number of native speakers, sixth-most spoken language, the third-most spoken European language in the world in terms of native speakers and the second most spoken Romance languages, Romance language in the world, surpassed only by Spanish language, Spanish. Being the most widely spoken language in South America and all of the Southern Hemisphere, it is also the second-most spoken language, after Spanish language, Spanish, in Latin America, one of the 10 most spoken languages in Africa, and an official language of the European Union, Mercosur, the Organization of American States#Official languages, Organization of American States, the Economic Community of West African States, the African Union, and the Community of Portuguese Language Countries, an international organization made up of all of the world's officially Lusophone nations. In 1997, a comprehensive academic study ranked Portuguese as one of the 10 most influential languages in the world.

It is in Latin administrative documents of the 9th century that written Galician-Portuguese words and phrases are first recorded. This phase is known as Proto-Portuguese, which lasted from the 9th century until the 12th-century independence of the County of Portugal from the Kingdom of Leأ³n, which had by then assumed reign over Galicia (Spain), Galicia.

In the first part of the Galician-Portuguese period (from the 12th to the 14th century), the language was increasingly used for documents and other written forms. For some time, it was the language of preference for lyric poetry in Christian Hispania, much as Occitan language, Occitan was the language of the Occitan literature#Poetry of the troubadours, poetry of the troubadours in France. The Occitan digraphs ''lh'' and ''nh'', used in its classical orthography, were adopted by the Portuguese alphabet#Basic digraphs, orthography of Portuguese, presumably by Gerald of Braga, a monk from Moissac, who became bishop of Braga in Portugal in 1047, playing a major role in modernizing written Portuguese using classical Occitan language, Occitan norms. Portugal became an independent kingdom in 1139, under King Afonso I of Portugal. In 1290, King Denis of Portugal created the first Portuguese university in Lisbon (the ''Estudos Gerais'', which later moved to University of Coimbra, Coimbra) and decreed for Portuguese, then simply called the "common language," to be known as the Portuguese language and used officially.

In the second period of Old Portuguese, in the 15th and 16th centuries, with the Age of Discovery, Portuguese discoveries, the language was taken to many regions of Africa, Asia, and the Americas. By the mid-16th century, Portuguese had become a ''lingua franca'' in Asia and Africa, used not only for colonial administration and trade but also for communication between local officials and Europeans of all nationalities. The Portuguese expanded across South America, across Africa to the Pacific Ocean, taking their language with them.

Its spread was helped by mixed marriages between Portuguese and local people and by its association with Catholic Church, Roman Catholic missionary efforts, which led to the formation of creole languages such as that called Kristang language, Kristang in many parts of Asia (from the word ''cristأ£o'', "Christian"). The language continued to be popular in parts of Asia until the 19th century. Some Portuguese-speaking Christian communities in India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and Indonesia preserved their language even after they were isolated from Portugal.

The end of the Old Portuguese period was marked by the publication of the ''Cancioneiro Geral'' by Garcia de Resende, in 1516. The early times of Modern Portuguese, which spans the period from the 16th century to the present day, were characterized by an increase in the number of learned words borrowed from Classical Latin and Ancient Greek, Classical Greek because of the Renaissance (learned words borrowed from Latin also came from Renaissance Latin, the form of Latin during that time), which greatly enriched the lexicon. Most literate Portuguese speakers were also literate in Latin; and thus they easily adopted Latin words into their writing, and eventually speech, in Portuguese.

Spanish author Miguel de Cervantes once called Portuguese "the sweet and gracious language", while the Brazilian poet Olavo Bilac described it as ("the last flower of Latium, naأ¯ve and beautiful"). Portuguese is also termed "the language of Camأµes," after Luأs Vaz de Camأµes, one of the greatest literary figures in the Portuguese language and author of the Portuguese epic poem ''The Lusiads''.

In March 2006, the Museum of the Portuguese Language, an interactive museum about the Portuguese language, was founded in Sأ£o Paulo, Brazil, the city with the greatest number of Portuguese language speakers in the world. The museum is the first of its kind in the world. In 2015 the museum was partially destroyed in a fire, but restored and reopened in 2020.

It is in Latin administrative documents of the 9th century that written Galician-Portuguese words and phrases are first recorded. This phase is known as Proto-Portuguese, which lasted from the 9th century until the 12th-century independence of the County of Portugal from the Kingdom of Leأ³n, which had by then assumed reign over Galicia (Spain), Galicia.

In the first part of the Galician-Portuguese period (from the 12th to the 14th century), the language was increasingly used for documents and other written forms. For some time, it was the language of preference for lyric poetry in Christian Hispania, much as Occitan language, Occitan was the language of the Occitan literature#Poetry of the troubadours, poetry of the troubadours in France. The Occitan digraphs ''lh'' and ''nh'', used in its classical orthography, were adopted by the Portuguese alphabet#Basic digraphs, orthography of Portuguese, presumably by Gerald of Braga, a monk from Moissac, who became bishop of Braga in Portugal in 1047, playing a major role in modernizing written Portuguese using classical Occitan language, Occitan norms. Portugal became an independent kingdom in 1139, under King Afonso I of Portugal. In 1290, King Denis of Portugal created the first Portuguese university in Lisbon (the ''Estudos Gerais'', which later moved to University of Coimbra, Coimbra) and decreed for Portuguese, then simply called the "common language," to be known as the Portuguese language and used officially.

In the second period of Old Portuguese, in the 15th and 16th centuries, with the Age of Discovery, Portuguese discoveries, the language was taken to many regions of Africa, Asia, and the Americas. By the mid-16th century, Portuguese had become a ''lingua franca'' in Asia and Africa, used not only for colonial administration and trade but also for communication between local officials and Europeans of all nationalities. The Portuguese expanded across South America, across Africa to the Pacific Ocean, taking their language with them.

Its spread was helped by mixed marriages between Portuguese and local people and by its association with Catholic Church, Roman Catholic missionary efforts, which led to the formation of creole languages such as that called Kristang language, Kristang in many parts of Asia (from the word ''cristأ£o'', "Christian"). The language continued to be popular in parts of Asia until the 19th century. Some Portuguese-speaking Christian communities in India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and Indonesia preserved their language even after they were isolated from Portugal.

The end of the Old Portuguese period was marked by the publication of the ''Cancioneiro Geral'' by Garcia de Resende, in 1516. The early times of Modern Portuguese, which spans the period from the 16th century to the present day, were characterized by an increase in the number of learned words borrowed from Classical Latin and Ancient Greek, Classical Greek because of the Renaissance (learned words borrowed from Latin also came from Renaissance Latin, the form of Latin during that time), which greatly enriched the lexicon. Most literate Portuguese speakers were also literate in Latin; and thus they easily adopted Latin words into their writing, and eventually speech, in Portuguese.

Spanish author Miguel de Cervantes once called Portuguese "the sweet and gracious language", while the Brazilian poet Olavo Bilac described it as ("the last flower of Latium, naأ¯ve and beautiful"). Portuguese is also termed "the language of Camأµes," after Luأs Vaz de Camأµes, one of the greatest literary figures in the Portuguese language and author of the Portuguese epic poem ''The Lusiads''.

In March 2006, the Museum of the Portuguese Language, an interactive museum about the Portuguese language, was founded in Sأ£o Paulo, Brazil, the city with the greatest number of Portuguese language speakers in the world. The museum is the first of its kind in the world. In 2015 the museum was partially destroyed in a fire, but restored and reopened in 2020.

Portuguese is the native language of the vast majority of the people in Portugal, Brazil and Sأ£o Tomأ© and Prأncipe (95%). Perhaps 75% of the population of urban Angola speaks Portuguese natively, with approximately 85% fluent; these rates are lower in the countryside. Just over 50% (and rapidly increasing) of the population of Mozambique are native speakers of Portuguese, and 70% are fluent, according to the 2007 census. Portuguese is also spoken natively by 30% of the population in Guinea-Bissau, and a Portuguese-based creole is understood by all. No data is available for Cape Verde, but almost all the population is bilingual, and the monolingual population speaks the Portuguese-based Cape Verdean Creole. Portuguese is mentioned in the Constitution of South Africa as one of the languages spoken by communities within the country for which the Pan South African Language Board was charged with promoting and ensuring respect.

There are also significant Portuguese-speaking immigrant communities in many countries including Andorra (17.1%), Bermuda, Canada (400,275 people in the 2006 census), France (1,625,000 people), Japan (400,000 people), Jersey, Luxembourg (about 25% of the population as of 2021), Namibia (about 4–5% of the population, mainly refugees from Angola in the north of the country), Paraguay (10.7% or 636,000 people), Macau (2.3% speak fluent Portuguese or 15,000 people), Switzerland (550,000 in 2019, learning + mother tongue), Venezuela (554,000). and the United States (0.35% of the population or 1,228,126 speakers according to the 2007 American Community Survey).

In some parts of former Portuguese India, namely Goa and Daman and Diu, the language is still spoken by about 10,000 people. In 2014, an estimated 1,500 students were learning Portuguese in Goa.

Portuguese is the native language of the vast majority of the people in Portugal, Brazil and Sأ£o Tomأ© and Prأncipe (95%). Perhaps 75% of the population of urban Angola speaks Portuguese natively, with approximately 85% fluent; these rates are lower in the countryside. Just over 50% (and rapidly increasing) of the population of Mozambique are native speakers of Portuguese, and 70% are fluent, according to the 2007 census. Portuguese is also spoken natively by 30% of the population in Guinea-Bissau, and a Portuguese-based creole is understood by all. No data is available for Cape Verde, but almost all the population is bilingual, and the monolingual population speaks the Portuguese-based Cape Verdean Creole. Portuguese is mentioned in the Constitution of South Africa as one of the languages spoken by communities within the country for which the Pan South African Language Board was charged with promoting and ensuring respect.

There are also significant Portuguese-speaking immigrant communities in many countries including Andorra (17.1%), Bermuda, Canada (400,275 people in the 2006 census), France (1,625,000 people), Japan (400,000 people), Jersey, Luxembourg (about 25% of the population as of 2021), Namibia (about 4–5% of the population, mainly refugees from Angola in the north of the country), Paraguay (10.7% or 636,000 people), Macau (2.3% speak fluent Portuguese or 15,000 people), Switzerland (550,000 in 2019, learning + mother tongue), Venezuela (554,000). and the United States (0.35% of the population or 1,228,126 speakers according to the 2007 American Community Survey).

In some parts of former Portuguese India, namely Goa and Daman and Diu, the language is still spoken by about 10,000 people. In 2014, an estimated 1,500 students were learning Portuguese in Goa.

The Community of Portuguese Language Countries

(in Portuguese ''Comunidade dos Paأses de Lأngua Portuguesa'', with the Portuguese acronym CPLP) consists of the nine independent countries that have Portuguese as an official language: Angola, Brazil, Cape Verde, East Timor, Equatorial Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Portugal and Sأ£o Tomأ© and Prأncipe.

Equatorial Guinea made a formal application for full membership to the CPLP in June 2010, a status given only to states with Portuguese as an official language. In 2011, Portuguese became its third official language (besides Spanish language, Spanish and French language, French) and, in July 2014, the country was accepted as a member of the CPLP.

Portuguese is also one of the official languages of the Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China of Macau (alongside Chinese language, Chinese) and of several international organizations, including Mercosur, the Organization of Ibero-American States, the Union of South American Nations, the Organization of American States, the African Union,Article 11, Protocol on Amendments to the Constitutive Act of the African Union the Economic Community of West African States, the Southern African Development Community and the European Union.

The Community of Portuguese Language Countries

(in Portuguese ''Comunidade dos Paأses de Lأngua Portuguesa'', with the Portuguese acronym CPLP) consists of the nine independent countries that have Portuguese as an official language: Angola, Brazil, Cape Verde, East Timor, Equatorial Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Portugal and Sأ£o Tomأ© and Prأncipe.

Equatorial Guinea made a formal application for full membership to the CPLP in June 2010, a status given only to states with Portuguese as an official language. In 2011, Portuguese became its third official language (besides Spanish language, Spanish and French language, French) and, in July 2014, the country was accepted as a member of the CPLP.

Portuguese is also one of the official languages of the Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China of Macau (alongside Chinese language, Chinese) and of several international organizations, including Mercosur, the Organization of Ibero-American States, the Union of South American Nations, the Organization of American States, the African Union,Article 11, Protocol on Amendments to the Constitutive Act of the African Union the Economic Community of West African States, the Southern African Development Community and the European Union.

, a pronoun meaning "you", is used for educated, formal, and colloquial respectful speech in most Portuguese-speaking regions. In a few Brazilian states such as Rio Grande do Sul, Parأ،, among others, is virtually absent from the spoken language. Riograndense and European Portuguese normally distinguishes formal from informal speech by verbal conjugation. Informal speech employs followed by second person verbs, formal language retains the formal , followed by the third person conjugation.

Conjugation of verbs in has three different forms in Brazil (verb "to see": , in the traditional second person, , in the third person, and , in the innovative second person), the conjugation used in the Brazilian states of Parأ،, Santa Catarina and Maranhأ£o being generally traditional second person, the kind that is used in other Portuguese-speaking countries and learned in Brazilian schools.

The predominance of Southeastern-based media products has established as the pronoun of choice for the second person singular in both writing and multimedia communications. However, in the city of Rio de Janeiro, the country's main cultural center, the usage of has been expanding ever since the end of the 20th century, being most frequent among youngsters, and a number of studies have also shown an increase in its use in a number of other Brazilian dialects.

, a pronoun meaning "you", is used for educated, formal, and colloquial respectful speech in most Portuguese-speaking regions. In a few Brazilian states such as Rio Grande do Sul, Parأ،, among others, is virtually absent from the spoken language. Riograndense and European Portuguese normally distinguishes formal from informal speech by verbal conjugation. Informal speech employs followed by second person verbs, formal language retains the formal , followed by the third person conjugation.

Conjugation of verbs in has three different forms in Brazil (verb "to see": , in the traditional second person, , in the third person, and , in the innovative second person), the conjugation used in the Brazilian states of Parأ،, Santa Catarina and Maranhأ£o being generally traditional second person, the kind that is used in other Portuguese-speaking countries and learned in Brazilian schools.

The predominance of Southeastern-based media products has established as the pronoun of choice for the second person singular in both writing and multimedia communications. However, in the city of Rio de Janeiro, the country's main cultural center, the usage of has been expanding ever since the end of the 20th century, being most frequent among youngsters, and a number of studies have also shown an increase in its use in a number of other Brazilian dialects.

Modern Standard European Portuguese ( or ) is based on the Portuguese spoken in the area including and surrounding the cities of Coimbra and Lisbon, in central Portugal. Standard European Portuguese is also the preferred standard by the Portuguese-speaking African countries. As such, and despite the fact that its speakers are dispersed around the world, Portuguese has only two dialects used for learning: the European and the Brazilian. Some aspects and sounds found in many dialects of Brazil are exclusive to South America, and cannot be found in Europe. The same occur with the Santomean, Mozambican, Bissau-Guinean, Angolan and Cape Verdean dialects, being exclusive to Africa. See Portuguese in Africa.

Audio samples of some dialects and accents of Portuguese are available below. There are some differences between the areas but these are the best approximations possible. IPA transcriptions refer to the names in local pronunciation.

Modern Standard European Portuguese ( or ) is based on the Portuguese spoken in the area including and surrounding the cities of Coimbra and Lisbon, in central Portugal. Standard European Portuguese is also the preferred standard by the Portuguese-speaking African countries. As such, and despite the fact that its speakers are dispersed around the world, Portuguese has only two dialects used for learning: the European and the Brazilian. Some aspects and sounds found in many dialects of Brazil are exclusive to South America, and cannot be found in Europe. The same occur with the Santomean, Mozambican, Bissau-Guinean, Angolan and Cape Verdean dialects, being exclusive to Africa. See Portuguese in Africa.

Audio samples of some dialects and accents of Portuguese are available below. There are some differences between the areas but these are the best approximations possible. IPA transcriptions refer to the names in local pronunciation.

#

#  ''Fluminense''

''Fluminense''

nbsp;– A broad dialect with many variants spoken in the states of Rio de Janeiro (state), Rio de Janeiro, Espأrito Santo and neighboring eastern regions of Minas Gerais. ''Fluminense'' formed in these previously ''caipira''-speaking areas due to the gradual influence of European migrants, causing many people to distance their speech from their original dialect and incorporate new terms. ''Fluminense'' is sometimes referred to as ''carioca'', however ''carioca'' is a more specific term referring to the accent of the Greater Rio de Janeiro area by speakers with a ''fluminense'' dialect. # ''Gaأ؛cho dialect, Gaأ؛cho'' – in Rio Grande do Sul, similar to ''sulista''. There are many distinct accents in Rio Grande do Sul, mainly due to the heavy influx of European immigrants of diverse origins who have settled in colonies throughout the state, and to the proximity to Hispanosphere, Spanish-speaking nations. The ''gaأ؛cho'' word in itself is a Spanish loanword into Portuguese of obscure Indigenous languages of the Americas, Indigenous Amerindian origins. # ''Mineiro'' – Minas Gerais (not prevalent in the Triأ¢ngulo Mineiro). As the ''fluminense'' area, its associated region was formerly a sparsely populated land where ''caipira'' was spoken, but Minas Gerais#History, the discovery of gold and gems made it the most prosperous Brazilian region, what attracted Portuguese colonists, commoners from other parts of Brazil and their African slaves. South-southwestern, Zona da Mata (Minas Gerais), southeastern and northern areas of the state have fairly distinctive speech, actually approximating to ''caipira'', ''fluminense'' (popularly called, often pejoratively, ''carioca do brejo'', "marsh carioca") and ''baiano'' respectively. Areas including and surrounding Belo Horizonte have a distinctive accent.

#

''Mineiro'' – Minas Gerais (not prevalent in the Triأ¢ngulo Mineiro). As the ''fluminense'' area, its associated region was formerly a sparsely populated land where ''caipira'' was spoken, but Minas Gerais#History, the discovery of gold and gems made it the most prosperous Brazilian region, what attracted Portuguese colonists, commoners from other parts of Brazil and their African slaves. South-southwestern, Zona da Mata (Minas Gerais), southeastern and northern areas of the state have fairly distinctive speech, actually approximating to ''caipira'', ''fluminense'' (popularly called, often pejoratively, ''carioca do brejo'', "marsh carioca") and ''baiano'' respectively. Areas including and surrounding Belo Horizonte have a distinctive accent.

#  ''Nordestino''

''Nordestino''

ref name="ReferenceB">Note: the speaker of this sound file is from Rio de Janeiro, and he is talking about his experience with ''nordestino'' and ''nortista'' accents. – more marked in the Sertأ£o (7), where, in the 19th and 20th centuries and especially in the area including and surrounding the ''sertأ£o'' (the dry land after Agreste) of Pernambuco and southern Cearأ،, it could sound less comprehensible to speakers of other Portuguese dialects than Galician or Rioplatense Spanish, and nowadays less distinctive from other variants in the metropolitan cities Zona da Mata, along the coasts. It can be divided in two regional variants, one that includes the northern Maranhأ£o and southern of Piauأ, and other that goes from Cearأ، to Alagoas. # ''Nortista'' or ''amazofonia'' – Most of Amazon Basin states, i.e. North Region, Brazil, Northern Brazil. Before the 20th century, most people from the ''nordestino'' area fleeing the droughts and their associated poverty settled here, so it has some similarities with the Portuguese dialect there spoken. The speech in and around the cities of Belأ©m and Manaus has a more European flavor in phonology, prosody and grammar. # ''Paulistano dialect, Paulistano'' – Variants spoken around Greater Sأ£o Paulo in its maximum definition and more easterly areas of Sأ£o Paulo state, as well as perhaps "educated speech" from anywhere in Sأ£o Paulo (state), the state of Sأ£o Paulo (where it coexists with ''caipira''). ''Caipira'' is the hinterland sociolect of much of the Centro-Sul, Central-Southern half of Brazil, nowadays conservative only in the rural areas and associated with them, that has a historically prestige (sociolinguistics), low prestige in cities as Rio de Janeiro, Curitiba, Belo Horizonte, and until some years ago, in Sأ£o Paulo itself. Sociolinguistics, or what by times is described as "linguistic discrimination, linguistic prejudice", often correlated with Class discrimination, classism, is a polemic topic in the entirety of the country since the times of Adoniran Barbosa#Musical production, Adoniran Barbosa. Also, the "Paulistano" accent was heavily influenced by the presence of immigrants in the city of Sأ£o Paulo, especially the Italians. # ''Sertanejo'' – Center-West Region, Brazil, Center-Western states, and also much of Tocantins and Rondأ´nia. It is closer to ''mineiro'', ''caipira'', ''nordestino'' or ''nortista'' depending on the location. # ''Sulista'' – The variants spoken in the areas between the northern regions of Rio Grande do Sul and southern regions of Sأ£o Paulo state, encompassing most of South Region, Brazil, southern Brazil. The city of Curitiba does have a fairly distinct accent as well, and a relative majority of speakers around and in Florianأ³polis also speak this variant (many speak ''florianopolitano'' or ''manezinho da ilha'' instead, related to the European Portuguese dialects spoken in Azores and Madeira). Speech of northern Paranأ، is closer to that of inland Sأ£o Paulo. # ''Florianopolitan dialect, Florianopolitano'' – Variants heavily influenced by European Portuguese spoken in Florianأ³polis city (due to a heavy immigration movement from Portugal, mainly its Autonomous regions of Portugal, insular regions) and much of its metropolitan area, Grande Florianأ³polis, said to be a continuum between those whose speech most resemble ''sulista'' dialects and those whose speech most resemble ''fluminense'' and European ones, called, often pejoratively, ''manezinho da ilha''. # ''Carioca'' – Not a dialect, but sociolects of the ''fluminense'' variant spoken in an area roughly corresponding to Greater Rio de Janeiro. It appeared after locals came in contact with the Portuguese aristocracy amidst the Transfer of the Portuguese Court to Brazil, Portuguese royal family fled in the early 19th century. There is actually a continuum between Vernacular countryside accents and the ''carioca'' sociolect, and the educated speech (in Portuguese ''norma culta'', which most closely resembles other Brazilian Portuguese standards but with marked recent Portuguese influences, the nearest ones among the country's dialects along ''florianopolitano''), so that not all people native to the state of Rio de Janeiro speak the said sociolect, but most ''carioca'' speakers will use the standard variant not influenced by it that is rather uniform around Brazil depending on context (emphasis or formality, for example). # ''Brasiliense'' – used in Brasأlia and its metropolitan area. It is not considered a dialect, but more of a regional variant – often deemed to be closer to ''fluminense'' than the dialect commonly spoken in most of Goiأ،s, ''sertanejo''. # ''Arco do desflorestamento'' or '':pt:Dialeto da serra amazأ´nica, serra amazأ´nica'' – Known in its region as the "accent of the migrants," it has similarities with ''caipira'', ''sertanejo'' and often ''sulista'' that make it differing from ''amazofonia'' (in the opposite group of Brazilian dialects, in which it is placed along ''nordestino'', ''baiano'', ''mineiro'' and ''fluminense''). It is the most recent dialect, which appeared by the settlement of families from various other Brazilian regions attracted by the cheap land offer in recently Deforestation, deforested areas. # ''Recifense'' – used in Recife and its metropolitan area.

#

#

''Micaelense (Aأ§ores)''

(Sأ£o Miguel) – Azores. # ''Alentejano''

''Alentejano''

– Alentejo (Alentejan Portuguese) # ''Algarvio''

''Algarvio''

– Algarve (there is a particular dialect in a small part of western Algarve). # ''Minhoto''

''Minhoto''

nbsp;– Districts of Braga and Viana do Castelo (hinterland). # ''Beirأ£o''; ''Alto-Alentejano''

''Beirأ£o''; ''Alto-Alentejano''

– Central Portugal (hinterland). #

– Central Portugal. #

nbsp;– Regions of Coimbra and Lisbon (this is a disputed denomination, as Coimbra and is not part of "Estremadura", and the Lisbon dialect has some peculiar features that are not only not shared with that of Coimbra, but also significantly distinct and recognizable to most native speakers from elsewhere in Portugal). # ''Madeirense''

''Madeirense''

(Madeiran) – Madeira. # ''Portuense''

''Portuense''

nbsp;– Regions of the district of Porto and parts of Aveiro, Portugal, Aveiro. # ''Transmontano''

''Transmontano''

nbsp;– Trأ،s-os-Montes e Alto Douro.

''Angolano''

''Angolano''

(Angolan Portuguese) * – ''Cabo-verdiano''

''Cabo-verdiano''

(Cape Verdean Portuguese) * – ''Timorense''

''Timorense''

(East Timorese Portuguese) * – ''Damaense'' (Damanese Portuguese) and ''Goأھs'' (Goan Portuguese) * – ''Guineense''

''Guineense''

(Guinean Portuguese) * – ''Macaense''

''Macaense''

(Macanese Portuguese) * – ''Moأ§ambicano''

''Moأ§ambicano''

(Mozambican Portuguese) * – ''Santomense''

''Santomense''

(Sأ£o Tomean Portuguese) * – Riverense Portuأ±ol language, ''Dialectos Portugueses del Uruguay (DPU)'' Differences between dialects are mostly of Accent (dialect), accent and vocabulary, but between the Brazilian dialects and other dialects, especially in their most colloquial forms, there can also be some grammatical differences. The Portuguese creole, Portuguese-based creoles spoken in various parts of Africa, Asia, and the Americas are independent languages.

Starting in the 15th century, the Portuguese maritime explorations led to the introduction of many loanwords from Asian languages. For instance, ('cutlass') from Japanese language, Japanese ''katana'', ('tea') from Chinese language, Chinese ''Tea#Etymology, chأ،'', and ''Canja de galinha, canja'' ('chicken-soup, piece of cake') from Malay language, Malay.

From the 16th to the 19th centuries, because of the role of Portugal as intermediary in the Atlantic slave trade, and the establishment of large Portuguese colonies in Angola, Mozambique, and Brazil, Portuguese acquired several words of African and indigenous peoples of Brazil, Amerind origin, especially names for most of the animals and plants found in those territories. While those terms are mostly used in the former colonies, many became current in European Portuguese as well. From Kimbundu language, Kimbundu, for example, came ''kifumate'' > ('head caress') (Brazil), ''kusula'' > ('youngest child') (Brazil), ('tropical wasp') (Brazil), and ''kubungula'' > ('to dance like a wizard') (Angola). From South America came ('potato'), from Taأno language, Taino; and , from Tupi–Guarani languages, Tupi–Guarani ''nanأ،'' and Tupi language, Tupi ''ibأ، cati'', respectively (two species of pineapple), and ('popcorn') from Tupi and ('toucan') from Guarani language, Guarani ''tucan''.

Finally, it has received a steady influx of loanwords from other European languages, especially French and English language, English. These are by far the most important languages when referring to loanwords. There are many examples such as: / ('bracket'/'crochet'), ('jacket'), ('lipstick'), and / ('steak'/'slice'), ('street'), respectively, from French , , , , ; and ('steak'), , , /, , from English "beef," "football," "revolver," "stock," "folklore."

Examples from other European languages: ('pasta'), ('pilot'), ('carriage'), and ('barrack'), from Italian , , , and ; ('hair lock'), ('wet-cured ham') (in Portugal, in contrast with ''presunto'' 'dry-cured ham' from Latin ''prae-exsuctus'' 'dehydrated') or ('canned ham') (in Brazil, in contrast with non-canned, wet-cured (''presunto cozido'') and dry-cured (''presunto cru'')), or ''castelhano'' ('Castilian'), from Spanish ''melena'' ('mane'), ''fiambre'' and ''castellano.''

Starting in the 15th century, the Portuguese maritime explorations led to the introduction of many loanwords from Asian languages. For instance, ('cutlass') from Japanese language, Japanese ''katana'', ('tea') from Chinese language, Chinese ''Tea#Etymology, chأ،'', and ''Canja de galinha, canja'' ('chicken-soup, piece of cake') from Malay language, Malay.

From the 16th to the 19th centuries, because of the role of Portugal as intermediary in the Atlantic slave trade, and the establishment of large Portuguese colonies in Angola, Mozambique, and Brazil, Portuguese acquired several words of African and indigenous peoples of Brazil, Amerind origin, especially names for most of the animals and plants found in those territories. While those terms are mostly used in the former colonies, many became current in European Portuguese as well. From Kimbundu language, Kimbundu, for example, came ''kifumate'' > ('head caress') (Brazil), ''kusula'' > ('youngest child') (Brazil), ('tropical wasp') (Brazil), and ''kubungula'' > ('to dance like a wizard') (Angola). From South America came ('potato'), from Taأno language, Taino; and , from Tupi–Guarani languages, Tupi–Guarani ''nanأ،'' and Tupi language, Tupi ''ibأ، cati'', respectively (two species of pineapple), and ('popcorn') from Tupi and ('toucan') from Guarani language, Guarani ''tucan''.

Finally, it has received a steady influx of loanwords from other European languages, especially French and English language, English. These are by far the most important languages when referring to loanwords. There are many examples such as: / ('bracket'/'crochet'), ('jacket'), ('lipstick'), and / ('steak'/'slice'), ('street'), respectively, from French , , , , ; and ('steak'), , , /, , from English "beef," "football," "revolver," "stock," "folklore."

Examples from other European languages: ('pasta'), ('pilot'), ('carriage'), and ('barrack'), from Italian , , , and ; ('hair lock'), ('wet-cured ham') (in Portugal, in contrast with ''presunto'' 'dry-cured ham' from Latin ''prae-exsuctus'' 'dehydrated') or ('canned ham') (in Brazil, in contrast with non-canned, wet-cured (''presunto cozido'') and dry-cured (''presunto cru'')), or ''castelhano'' ('Castilian'), from Spanish ''melena'' ('mane'), ''fiambre'' and ''castellano.''

Portuguese belongs to the West Iberian languages, West Iberian branch of the Romance languages, and it has special ties with the following members of this group:

* Galician language, Galician, Fala language, Fala and Riverense Portuأ±ol language, ''portunhol do pampa'' (the way ''riverense'' and its sibling dialects are referred to in Portuguese), its closest relatives.

* Mirandese language, Mirandese, Leonese language, Leonese, Asturian language, Asturian, Extremaduran language, Extremaduran and Cantabrian dialect, Cantabrian (Astur-Leonese languages). Mirandese is the only recognised regional language spoken in Portugal (beside Portuguese, the only official language in Portugal).

* Spanish language, Spanish and Calأ³ language, ''calأ£o'' (the way ''calأ³'', language of the Iberian Romani people, Romani, is referred to in Portuguese).

Portuguese and other Romance languages (namely French language, French and Italian language, Italian) share considerable similarities in both vocabulary and grammar. Portuguese speakers will usually need some formal study before attaining strong comprehension in those Romance languages, and vice versa. However, Portuguese and Galician are fully mutually intelligible, and Spanish is considerably intelligible for lusophones, owing to their genealogical proximity and shared genealogical history as West Iberian languages, West Iberian (Ibero-Romance languages), historical contact between speakers and mutual influence, shared areal features as well as modern lexical, structural, and grammatical similarity (89%) between them.

Portuأ±ol/Portunhol, a form of code-switching, has a more lively use and is more readily mentioned in popular culture in South America. Said code-switching is not to be confused with the Portuأ±ol spoken on the borders of Brazil with Uruguay () and Paraguay (), and of Portugal with Spain (), that are Portuguese dialects spoken natively by thousands of people, which have been heavily influenced by Spanish.

Portuguese and Spanish are the only Ibero-Romance languages, and perhaps the only Romance languages with such thriving inter-language forms, in which visible and lively bilingual contact dialects and code-switching have formed, in which functional bilingual communication is achieved through attempting an approximation to the target foreign language (known as 'Portuأ±ol') without a learned acquisition process, but nevertheless facilitates communication. There is an emerging literature focused on such phenomena (including informal attempts of standardization of the linguistic continua and their usage).

Portuguese belongs to the West Iberian languages, West Iberian branch of the Romance languages, and it has special ties with the following members of this group:

* Galician language, Galician, Fala language, Fala and Riverense Portuأ±ol language, ''portunhol do pampa'' (the way ''riverense'' and its sibling dialects are referred to in Portuguese), its closest relatives.

* Mirandese language, Mirandese, Leonese language, Leonese, Asturian language, Asturian, Extremaduran language, Extremaduran and Cantabrian dialect, Cantabrian (Astur-Leonese languages). Mirandese is the only recognised regional language spoken in Portugal (beside Portuguese, the only official language in Portugal).

* Spanish language, Spanish and Calأ³ language, ''calأ£o'' (the way ''calأ³'', language of the Iberian Romani people, Romani, is referred to in Portuguese).

Portuguese and other Romance languages (namely French language, French and Italian language, Italian) share considerable similarities in both vocabulary and grammar. Portuguese speakers will usually need some formal study before attaining strong comprehension in those Romance languages, and vice versa. However, Portuguese and Galician are fully mutually intelligible, and Spanish is considerably intelligible for lusophones, owing to their genealogical proximity and shared genealogical history as West Iberian languages, West Iberian (Ibero-Romance languages), historical contact between speakers and mutual influence, shared areal features as well as modern lexical, structural, and grammatical similarity (89%) between them.

Portuأ±ol/Portunhol, a form of code-switching, has a more lively use and is more readily mentioned in popular culture in South America. Said code-switching is not to be confused with the Portuأ±ol spoken on the borders of Brazil with Uruguay () and Paraguay (), and of Portugal with Spain (), that are Portuguese dialects spoken natively by thousands of people, which have been heavily influenced by Spanish.

Portuguese and Spanish are the only Ibero-Romance languages, and perhaps the only Romance languages with such thriving inter-language forms, in which visible and lively bilingual contact dialects and code-switching have formed, in which functional bilingual communication is achieved through attempting an approximation to the target foreign language (known as 'Portuأ±ol') without a learned acquisition process, but nevertheless facilitates communication. There is an emerging literature focused on such phenomena (including informal attempts of standardization of the linguistic continua and their usage).

Portuguese has provided loanwords to many languages, such as Indonesian language, Indonesian, Manado Malay, Malayalam, Sri Lanka Tamils (native), Sri Lankan Tamil and Sinhala language, Sinhala, Malay language, Malay, Bengali language, Bengali, English (language), English, Hindi, Swahili language, Swahili, Afrikaans, Konkani language, Konkani, Marathi language, Marathi, Punjabi language, Punjabi, Tetum language, Tetum, Tsonga language, Xitsonga, Japanese language, Japanese, Lanc-Patuأ، creole, Lanc-Patuأ،, Esan people#Language, Esan, Bandar Abbas, Bandari (spoken in Iran) and Sranan Tongo (spoken in Suriname). It left a strong influence on the ''Old Tupi, lأngua brasأlica'', a Tupi–Guarani language, which was the most widely spoken in Brazil until the 18th century, and on the language spoken around Sikka Regency, Sikka in Flores Island, Indonesia. In nearby Larantuka, Portuguese is used for prayers in Holy Week rituals.

The Japanese–Portuguese dictionary ''Nippo Jisho'' (1603) was the first dictionary of Japanese in a European language, a product of Society of Jesus, Jesuit missionary activity in Japan. Building on the work of earlier Portuguese missionaries, the ''Dictionarium Anamiticum, Lusitanum et Latinum'' (Annamite–Portuguese–Latin dictionary) of Alexandre de Rhodes (1651) introduced the modern Vietnamese alphabet, orthography of Vietnamese, which is based on the orthography of 17th-century Portuguese. The Romanization of Chinese language, Chinese was also influenced by the Portuguese language (among others), particularly regarding List of common Chinese surnames, Chinese surnames; one example is ''Mei''. During 1583–88 Italians, Italian Jesuits Michele Ruggieri and Matteo Ricci created a Portuguese–Chinese dictionary – the first ever European–Chinese dictionary.''Dicionأ،rio Portuguأھs–Chinأھs : Pu Han ci dian: Portuguese–Chinese dictionary'', by Michele Ruggieri, Matteo Ricci; edited by John W. Witek. Published 2001, Biblioteca Nacional.

Portuguese has provided loanwords to many languages, such as Indonesian language, Indonesian, Manado Malay, Malayalam, Sri Lanka Tamils (native), Sri Lankan Tamil and Sinhala language, Sinhala, Malay language, Malay, Bengali language, Bengali, English (language), English, Hindi, Swahili language, Swahili, Afrikaans, Konkani language, Konkani, Marathi language, Marathi, Punjabi language, Punjabi, Tetum language, Tetum, Tsonga language, Xitsonga, Japanese language, Japanese, Lanc-Patuأ، creole, Lanc-Patuأ،, Esan people#Language, Esan, Bandar Abbas, Bandari (spoken in Iran) and Sranan Tongo (spoken in Suriname). It left a strong influence on the ''Old Tupi, lأngua brasأlica'', a Tupi–Guarani language, which was the most widely spoken in Brazil until the 18th century, and on the language spoken around Sikka Regency, Sikka in Flores Island, Indonesia. In nearby Larantuka, Portuguese is used for prayers in Holy Week rituals.

The Japanese–Portuguese dictionary ''Nippo Jisho'' (1603) was the first dictionary of Japanese in a European language, a product of Society of Jesus, Jesuit missionary activity in Japan. Building on the work of earlier Portuguese missionaries, the ''Dictionarium Anamiticum, Lusitanum et Latinum'' (Annamite–Portuguese–Latin dictionary) of Alexandre de Rhodes (1651) introduced the modern Vietnamese alphabet, orthography of Vietnamese, which is based on the orthography of 17th-century Portuguese. The Romanization of Chinese language, Chinese was also influenced by the Portuguese language (among others), particularly regarding List of common Chinese surnames, Chinese surnames; one example is ''Mei''. During 1583–88 Italians, Italian Jesuits Michele Ruggieri and Matteo Ricci created a Portuguese–Chinese dictionary – the first ever European–Chinese dictionary.''Dicionأ،rio Portuguأھs–Chinأھs : Pu Han ci dian: Portuguese–Chinese dictionary'', by Michele Ruggieri, Matteo Ricci; edited by John W. Witek. Published 2001, Biblioteca Nacional.

Partial preview

available on Google Books For instance, as Portuguese Empire, Portuguese merchants were presumably the first to introduce the sweet orange in Europe, in several modern Indo-European languages the fruit has been named after them. Some examples are Albanian ''wikt:portokall#Albanian, portokall'', Bosnian (archaic) ''portokal'', ''prtokal'', Bulgarian wikt:ذ؟ذ¾ر€ر‚ذ¾ذ؛ذ°ذ»#Bulgarian, ذ؟ذ¾ر€ر‚ذ¾ذ؛ذ°ذ» (''portokal''), Greek wikt:د€خ؟دپد„خ؟خ؛خ¬خ»خ¹#Greek, د€خ؟دپد„خ؟خ؛خ¬خ»خ¹ (''portokأ،li''), Macedonian language, Macedonian ', Persian wikt:ظ¾ط±طھظ‚ط§ظ„#Persian, ظ¾ط±طھظ‚ط§ظ„ (''porteghal''), and Romanian ''wikt:portocalؤƒ#Romanian, portocalؤƒ''. Related names can be found in other languages, such as Arabic wikt:ط§ظ„ط¨ط±طھظ‚ط§ظ„#Arabic, ط§ظ„ط¨ط±طھظ‚ط§ظ„ (''burtuqؤپl''), Georgian language, Georgian wikt:لƒ¤لƒلƒ لƒ—لƒلƒ®لƒگلƒڑلƒک#Georgian, لƒ¤لƒلƒ لƒ—لƒلƒ®لƒگلƒڑلƒک (''p'ort'oxali''), Turkish ''wikt:portakal#Turkish, portakal'' and Amharic ''birtukan''. Also, in southern Italian language, Italian dialects (e.g. Neapolitan language, Neapolitan), an orange is '':wikt:portogallo, portogallo'' or '':wikt:it:purtuallo, purtuallo'', literally "(the) Portuguese (one)", in contrast to standard Italian ''arancia''.

Like Catalan language, Catalan and German language, German, Portuguese uses vowel quality to contrast stressed syllables with unstressed syllables. Unstressed isolated vowels tend to be vowel height, raised and sometimes centralized.

Like Catalan language, Catalan and German language, German, Portuguese uses vowel quality to contrast stressed syllables with unstressed syllables. Unstressed isolated vowels tend to be vowel height, raised and sometimes centralized.

Instituto Camأµes website

* ''A Lأngua Portuguesa'' i

Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil

* ''Carta de dotaأ§أ£o e fundaأ§أ£o da Igreja de S. Miguel de Lardosa, a.D. 882 (o mais antigo documento latino-portuguأھs original conhecido)'

; Literature * ''Poesia e Prosa Medievais'', by Maria Ema Tarracha Ferreira, Ulisseia 1998, 3rd ed., . * ''Bases Temأ،ticas – Lأngua, Literatura e Cultura Portuguesa'' i

Instituto Camأµes

* ''Portuguese literature'' i

The Catholic Encyclopedia

; Phonology, orthography and grammar * * Bergstrأ¶m, Magnus & Reis, Neves ''Prontuأ،rio Ortogrأ،fico'' Editorial Notأcias, 2004. * * * * * *

- Instituto Camأµes website

– Instituto Camأµes website

– Instituto Camأµes website

– Instituto Camأµes website

Portuguese Grammar

– Learn101.org ; Reference dictionaries * Antأ´nio Houaiss (2000), ''Dicionأ،rio Houaiss da Lأngua Portuguesa'' (228,500 entries). * Aurأ©lio Buarque de Holanda Ferreira, ''Novo Dicionأ،rio da Lأngua Portuguesa'' (1809 pp.)

English–Portuguese–Chinese Dictionary (Freeware for Windows/Linux/Mac)

; Linguistic studies * Cook, Manuela. Portuguese Pronouns and Other Forms of Address, from the Past into the Future – Structural, Semantic and Pragmatic Reflections, Ellipsis, vol. 11, APSA, www.portuguese-apsa.com/ellipsis, 2013 * * Cook, Manuela. On the Portuguese Forms of Address: From ''Vossa Mercأھ'' to ''Vocأھ'', Portuguese Studies Review 3.2, Durham: University of New Hampshire, 1995 * Lindley Cintra, Luأs F

''Nova Proposta de Classificaأ§أ£o dos Dialectos Galego- Portugueses''

(PDF) Boletim de Filologia, Lisboa, Centro de Estudos Filolأ³gicos, 1971.

History

When the Rome, Romans arrived in the Iberian Peninsula in 216 BC, they brought with them the Latin language, from which all Romance languages are descended. The language was spread by Roman soldiers, settlers, and merchants, who built Roman cities mostly near the settlements of previous Celts, Celtic civilizations established long before the Roman arrivals. For that reason, the language has kept a relevant substratum of much older, Atlantic European Megalithic Culture and Celts, Celtic culture, part of the Hispano-Celtic languages, Hispano-Celtic group of ancient languages."In the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula, and more specifically between the west and north Atlantic coasts and an imaginary line running north-south and linking Oviedo and Merida, there is a corpus of Latin inscriptions with particular characteristics of its own. This corpus contains some linguistic features that are clearly Celtic and others that in our opinion are not Celtic. The former we shall group, for the moment, under the label northwestern Hispano-Celtic. The latter are the same features found in well-documented contemporary inscriptions in the region occupied by the Lusitanians, and therefore belonging to the variety known as LUSITANIAN, or more broadly as GALLO-LUSITANIAN. As we have already said, we do not consider this variety to belong to the Celtic language family." Jordأ،n Colera 2007: p.750 In Latin, the Portuguese language is known as ''lusitana'' or ''(latina) lusitanica'', after the Lusitanians, a Celtic tribe that lived in the territory of present-day Portugal and Spain that adopted the Latin language as Roman settlers moved in. This is also the origin of the ''luso-'' prefix, seen in terms like "Lusophone." Between AD 409 and AD 711, as the Roman Empire collapsed in Western Europe, the Iberian Peninsula was conquered by Germanic peoples of the Migration Period. The occupiers, mainly Suebi, Visigoths and Buri tribe, Buri who originally spoke Germanic languages, quickly adopted late Roman culture and the Vulgar Latin dialects of the peninsula and over the next 300 years totally integrated into the local populations. Some Germanic words from that period are part of the Portuguese lexicon. After the Moors, Moorish invasion beginning in 711, Arabic language, Arabic became the administrative and common language in the conquered regions, but most of the Mozarabs, remaining Christian population continued to speak a form of Romance languages, Romance commonly known as Mozarabic language, Mozarabic, which lasted three centuries longer in Spain. Like other Neo-Latin and European languages, Portuguese has adopted a significant number of loanwords from Greek language, Greek, mainly in technical and scientific terminology. These borrowings occurred via Latin, and later during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Portuguese evolved from the medieval language, known today by linguists as Galician-Portuguese, Old Portuguese or Old Galician, of the northwestern medieval Kingdom of Galicia of which the County of Portugal was part. It is in Latin administrative documents of the 9th century that written Galician-Portuguese words and phrases are first recorded. This phase is known as Proto-Portuguese, which lasted from the 9th century until the 12th-century independence of the County of Portugal from the Kingdom of Leأ³n, which had by then assumed reign over Galicia (Spain), Galicia.

In the first part of the Galician-Portuguese period (from the 12th to the 14th century), the language was increasingly used for documents and other written forms. For some time, it was the language of preference for lyric poetry in Christian Hispania, much as Occitan language, Occitan was the language of the Occitan literature#Poetry of the troubadours, poetry of the troubadours in France. The Occitan digraphs ''lh'' and ''nh'', used in its classical orthography, were adopted by the Portuguese alphabet#Basic digraphs, orthography of Portuguese, presumably by Gerald of Braga, a monk from Moissac, who became bishop of Braga in Portugal in 1047, playing a major role in modernizing written Portuguese using classical Occitan language, Occitan norms. Portugal became an independent kingdom in 1139, under King Afonso I of Portugal. In 1290, King Denis of Portugal created the first Portuguese university in Lisbon (the ''Estudos Gerais'', which later moved to University of Coimbra, Coimbra) and decreed for Portuguese, then simply called the "common language," to be known as the Portuguese language and used officially.

In the second period of Old Portuguese, in the 15th and 16th centuries, with the Age of Discovery, Portuguese discoveries, the language was taken to many regions of Africa, Asia, and the Americas. By the mid-16th century, Portuguese had become a ''lingua franca'' in Asia and Africa, used not only for colonial administration and trade but also for communication between local officials and Europeans of all nationalities. The Portuguese expanded across South America, across Africa to the Pacific Ocean, taking their language with them.

Its spread was helped by mixed marriages between Portuguese and local people and by its association with Catholic Church, Roman Catholic missionary efforts, which led to the formation of creole languages such as that called Kristang language, Kristang in many parts of Asia (from the word ''cristأ£o'', "Christian"). The language continued to be popular in parts of Asia until the 19th century. Some Portuguese-speaking Christian communities in India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and Indonesia preserved their language even after they were isolated from Portugal.

The end of the Old Portuguese period was marked by the publication of the ''Cancioneiro Geral'' by Garcia de Resende, in 1516. The early times of Modern Portuguese, which spans the period from the 16th century to the present day, were characterized by an increase in the number of learned words borrowed from Classical Latin and Ancient Greek, Classical Greek because of the Renaissance (learned words borrowed from Latin also came from Renaissance Latin, the form of Latin during that time), which greatly enriched the lexicon. Most literate Portuguese speakers were also literate in Latin; and thus they easily adopted Latin words into their writing, and eventually speech, in Portuguese.

Spanish author Miguel de Cervantes once called Portuguese "the sweet and gracious language", while the Brazilian poet Olavo Bilac described it as ("the last flower of Latium, naأ¯ve and beautiful"). Portuguese is also termed "the language of Camأµes," after Luأs Vaz de Camأµes, one of the greatest literary figures in the Portuguese language and author of the Portuguese epic poem ''The Lusiads''.

In March 2006, the Museum of the Portuguese Language, an interactive museum about the Portuguese language, was founded in Sأ£o Paulo, Brazil, the city with the greatest number of Portuguese language speakers in the world. The museum is the first of its kind in the world. In 2015 the museum was partially destroyed in a fire, but restored and reopened in 2020.

It is in Latin administrative documents of the 9th century that written Galician-Portuguese words and phrases are first recorded. This phase is known as Proto-Portuguese, which lasted from the 9th century until the 12th-century independence of the County of Portugal from the Kingdom of Leأ³n, which had by then assumed reign over Galicia (Spain), Galicia.

In the first part of the Galician-Portuguese period (from the 12th to the 14th century), the language was increasingly used for documents and other written forms. For some time, it was the language of preference for lyric poetry in Christian Hispania, much as Occitan language, Occitan was the language of the Occitan literature#Poetry of the troubadours, poetry of the troubadours in France. The Occitan digraphs ''lh'' and ''nh'', used in its classical orthography, were adopted by the Portuguese alphabet#Basic digraphs, orthography of Portuguese, presumably by Gerald of Braga, a monk from Moissac, who became bishop of Braga in Portugal in 1047, playing a major role in modernizing written Portuguese using classical Occitan language, Occitan norms. Portugal became an independent kingdom in 1139, under King Afonso I of Portugal. In 1290, King Denis of Portugal created the first Portuguese university in Lisbon (the ''Estudos Gerais'', which later moved to University of Coimbra, Coimbra) and decreed for Portuguese, then simply called the "common language," to be known as the Portuguese language and used officially.

In the second period of Old Portuguese, in the 15th and 16th centuries, with the Age of Discovery, Portuguese discoveries, the language was taken to many regions of Africa, Asia, and the Americas. By the mid-16th century, Portuguese had become a ''lingua franca'' in Asia and Africa, used not only for colonial administration and trade but also for communication between local officials and Europeans of all nationalities. The Portuguese expanded across South America, across Africa to the Pacific Ocean, taking their language with them.

Its spread was helped by mixed marriages between Portuguese and local people and by its association with Catholic Church, Roman Catholic missionary efforts, which led to the formation of creole languages such as that called Kristang language, Kristang in many parts of Asia (from the word ''cristأ£o'', "Christian"). The language continued to be popular in parts of Asia until the 19th century. Some Portuguese-speaking Christian communities in India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and Indonesia preserved their language even after they were isolated from Portugal.

The end of the Old Portuguese period was marked by the publication of the ''Cancioneiro Geral'' by Garcia de Resende, in 1516. The early times of Modern Portuguese, which spans the period from the 16th century to the present day, were characterized by an increase in the number of learned words borrowed from Classical Latin and Ancient Greek, Classical Greek because of the Renaissance (learned words borrowed from Latin also came from Renaissance Latin, the form of Latin during that time), which greatly enriched the lexicon. Most literate Portuguese speakers were also literate in Latin; and thus they easily adopted Latin words into their writing, and eventually speech, in Portuguese.

Spanish author Miguel de Cervantes once called Portuguese "the sweet and gracious language", while the Brazilian poet Olavo Bilac described it as ("the last flower of Latium, naأ¯ve and beautiful"). Portuguese is also termed "the language of Camأµes," after Luأs Vaz de Camأµes, one of the greatest literary figures in the Portuguese language and author of the Portuguese epic poem ''The Lusiads''.

In March 2006, the Museum of the Portuguese Language, an interactive museum about the Portuguese language, was founded in Sأ£o Paulo, Brazil, the city with the greatest number of Portuguese language speakers in the world. The museum is the first of its kind in the world. In 2015 the museum was partially destroyed in a fire, but restored and reopened in 2020.

Geographic distribution

Official status

Lusophone countries

According to ''The World Factbook''s country population estimates for 2018, the population of each of the ten jurisdictions is as follows (by descending order): The combined population of the entire Lusophone area was estimated at 300 million in January 2022. This number does not include the Lusophone diaspora, estimated at 10 million people (including 4.5 million Portuguese, 3 million Brazilians, although it is hard to obtain official accurate numbers of diasporic Portuguese speakers because a significant portion of these citizens are naturalized citizens born outside of Lusophone territory or are children of immigrants, and may have only a basic command of the language. Additionally, a large part of the diaspora is a part of the already-counted population of the Portuguese-speaking countries and territories, such as the high number of Brazilian and Portuguese-speaking African countries, PALOP emigrant citizens in Portugal or the high number of Portuguese emigrant citizens in the PALOP and Brazil. The Portuguese language therefore serves more than 250 million people daily, who have direct or indirect legal, juridical and social contact with it, varying from the only language used in any contact, to only education, contact with local or international administration, commerce and services or the simple sight of road signs, public information and advertising in Portuguese.Portuguese as a foreign language

Portuguese is a mandatory subject in the school curriculum in Uruguay. Other countries where Portuguese is commonly taught in schools or where it has been introduced as an option include Venezuela, Zambia, the Republic of the Congo, Senegal, Namibia, Eswatini, Eswatini (Swaziland), South Africa, Ivory Coast, and Mauritius. In 2017, a project was launched to introduce Portuguese as a school subject in Zimbabwe. Also, according to Portugal's Minister of Foreign Affairs, the language will be part of the school curriculum of a total of 32 countries by 2020. In the countries listed below, Portuguese is spoken either as a native language by vast majorities due to the Portuguese colonial past or as a ''lingua franca'' in bordering and multilingual regions, such as on the border between Brazil and Uruguay & Paraguay, as well as Angola and Namibia. In many other countries, Portuguese is spoken by majorities as a second language. And there are still communities of thousands of Portuguese (or Creole language, Creole) first language speakers in Goa, Sri Lanka, Kuala Lumpur, Daman and Diu, etc. due to Portuguese Empire, Portuguese colonization. In East Timor, the number of Portuguese speakers is quickly increasing as Portuguese and Brazilian teachers are making great strides in teaching Portuguese in the schools all over the island. Additionally, there are many large Portuguese immigrant communities all over the world.Future

According to estimates by UNESCO, Portuguese is the fastest-growing European language after English language, English and the language has, according to the newspaper ''The Portugal News'' publishing data given from UNESCO, the highest potential for growth as an international language in southern Africa and South America. Portuguese is a globalized language spoken officially on four continents, and as a second language by millions worldwide. Since 1991, when Brazil signed into the economic community of Mercosul with other South American nations, namely Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay, Portuguese is either mandatory, or taught, in the schools of those South American countries. Although early in the 21st century, after Macau was returned to China and immigration of Brazilians of Japanese Brazilian, Japanese descent to Japan slowed down, the use of Portuguese was in decline in Asia, it is once again becoming a language of opportunity there, mostly because of increased diplomatic and financial ties with economically powerful Portuguese-speaking countries in the world.Current status and importance

Portuguese, being a language spread on all continents, is official in several international organizations; one of twenty official of the European Union, an official language of NATO, Organization of American States (alongside Spanish, French and English), one of eighteen official languages of the European Space Agency. It is also a working language in nonprofit organisations such as the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, Red Cross (alongside English, German, Spanish, French, Arabic and Russian), Amnesty International (alongside 32 other languages of which English is the most used, followed by Spanish, French, German, and Italian), and Mأ©decins sans Frontiأ¨res (used alongside English, Spanish, French and Arabic), in addition to being the official legal language in the African Court on Human and Peoples' Rights, also in Community of Portuguese Language Countries, an international organization formed essentially by Lusophone, lusophone countries.Dialects, accents and varieties

, a pronoun meaning "you", is used for educated, formal, and colloquial respectful speech in most Portuguese-speaking regions. In a few Brazilian states such as Rio Grande do Sul, Parأ،, among others, is virtually absent from the spoken language. Riograndense and European Portuguese normally distinguishes formal from informal speech by verbal conjugation. Informal speech employs followed by second person verbs, formal language retains the formal , followed by the third person conjugation.

Conjugation of verbs in has three different forms in Brazil (verb "to see": , in the traditional second person, , in the third person, and , in the innovative second person), the conjugation used in the Brazilian states of Parأ،, Santa Catarina and Maranhأ£o being generally traditional second person, the kind that is used in other Portuguese-speaking countries and learned in Brazilian schools.

The predominance of Southeastern-based media products has established as the pronoun of choice for the second person singular in both writing and multimedia communications. However, in the city of Rio de Janeiro, the country's main cultural center, the usage of has been expanding ever since the end of the 20th century, being most frequent among youngsters, and a number of studies have also shown an increase in its use in a number of other Brazilian dialects.

, a pronoun meaning "you", is used for educated, formal, and colloquial respectful speech in most Portuguese-speaking regions. In a few Brazilian states such as Rio Grande do Sul, Parأ،, among others, is virtually absent from the spoken language. Riograndense and European Portuguese normally distinguishes formal from informal speech by verbal conjugation. Informal speech employs followed by second person verbs, formal language retains the formal , followed by the third person conjugation.

Conjugation of verbs in has three different forms in Brazil (verb "to see": , in the traditional second person, , in the third person, and , in the innovative second person), the conjugation used in the Brazilian states of Parأ،, Santa Catarina and Maranhأ£o being generally traditional second person, the kind that is used in other Portuguese-speaking countries and learned in Brazilian schools.

The predominance of Southeastern-based media products has established as the pronoun of choice for the second person singular in both writing and multimedia communications. However, in the city of Rio de Janeiro, the country's main cultural center, the usage of has been expanding ever since the end of the 20th century, being most frequent among youngsters, and a number of studies have also shown an increase in its use in a number of other Brazilian dialects.

Brazil

# ''Caipira dialect, Caipira'' – Spoken in the states of Sأ£o Paulo (state), Sأ£o Paulo (most markedly on the countryside and rural areas); southern Minas Gerais, northern Paranأ، (state), Paranأ، and southeastern Mato Grosso do Sul. Depending on the vision of what constitutes ''caipira'', Triأ¢ngulo Mineiro, border areas of Goiأ،s and the remaining parts of Mato Grosso do Sul are included, and the frontier of ''caipira'' in Minas Gerais is expanded further northerly, though not reaching metropolitan Belo Horizonte. It is often said that ''caipira'' appeared by decreolization of the Old Tupi, lأngua brasأlica and the related lأngua geral paulista, then spoken in almost all of what is now Sأ£o Paulo, a former lingua franca in most of the contemporary Centro-Sul of Brazil before the 18th century, brought by the ''bandeirantes'', interior pioneers of Colonial Brazil, closely related to its northern counterpart Nheengatu language, Nheengatu, and that is why the dialect shows many general differences from other variants of the language. It has striking remarkable differences in comparison to other Brazilian dialects in phonology, prosody and grammar, often Social stigma, stigmatized as being strongly associated with a Prestige (sociolinguistics), substandard variant, now mostly rural. # North coast Portuguese, ''Cearense'' or ''Costa norte'' – is a dialect spoken more sharply in the states of Cearأ، and Piauأ. The variant of Cearأ، includes fairly distinctive traits it shares with the one spoken in Piauأ, though, such as distinctive regional phonology and vocabulary (for example, a debuccalization process stronger than that of Portuguese, a different system of the vowel harmony that spans Brazil from ''fluminense'' and ''mineiro'' to ''amazofonia'' but is especially prevalent in ''nordestino'', a very coherent coda sibilant palatalization as those of Portugal and Rio de Janeiro but allowed in fewer environments than in other accents of ''nordestino'', a greater presence of dental stop palatalization to palato-alveolar in comparison to other accents of ''nordestino'', among others, as well as a great number of archaic Portuguese words). # ''Baiano'' – Found in Bahia and border regions with Goiأ،s and Tocantins. Similar to ''nordestino'', it has a very characteristic Stress timing, syllable-timed rhythm and the greatest tendency to pronounce unstressed vowels as open-mid and .nbsp;– A broad dialect with many variants spoken in the states of Rio de Janeiro (state), Rio de Janeiro, Espأrito Santo and neighboring eastern regions of Minas Gerais. ''Fluminense'' formed in these previously ''caipira''-speaking areas due to the gradual influence of European migrants, causing many people to distance their speech from their original dialect and incorporate new terms. ''Fluminense'' is sometimes referred to as ''carioca'', however ''carioca'' is a more specific term referring to the accent of the Greater Rio de Janeiro area by speakers with a ''fluminense'' dialect. # ''Gaأ؛cho dialect, Gaأ؛cho'' – in Rio Grande do Sul, similar to ''sulista''. There are many distinct accents in Rio Grande do Sul, mainly due to the heavy influx of European immigrants of diverse origins who have settled in colonies throughout the state, and to the proximity to Hispanosphere, Spanish-speaking nations. The ''gaأ؛cho'' word in itself is a Spanish loanword into Portuguese of obscure Indigenous languages of the Americas, Indigenous Amerindian origins. #

''Mineiro'' – Minas Gerais (not prevalent in the Triأ¢ngulo Mineiro). As the ''fluminense'' area, its associated region was formerly a sparsely populated land where ''caipira'' was spoken, but Minas Gerais#History, the discovery of gold and gems made it the most prosperous Brazilian region, what attracted Portuguese colonists, commoners from other parts of Brazil and their African slaves. South-southwestern, Zona da Mata (Minas Gerais), southeastern and northern areas of the state have fairly distinctive speech, actually approximating to ''caipira'', ''fluminense'' (popularly called, often pejoratively, ''carioca do brejo'', "marsh carioca") and ''baiano'' respectively. Areas including and surrounding Belo Horizonte have a distinctive accent.

#

''Mineiro'' – Minas Gerais (not prevalent in the Triأ¢ngulo Mineiro). As the ''fluminense'' area, its associated region was formerly a sparsely populated land where ''caipira'' was spoken, but Minas Gerais#History, the discovery of gold and gems made it the most prosperous Brazilian region, what attracted Portuguese colonists, commoners from other parts of Brazil and their African slaves. South-southwestern, Zona da Mata (Minas Gerais), southeastern and northern areas of the state have fairly distinctive speech, actually approximating to ''caipira'', ''fluminense'' (popularly called, often pejoratively, ''carioca do brejo'', "marsh carioca") and ''baiano'' respectively. Areas including and surrounding Belo Horizonte have a distinctive accent.

# ref name="ReferenceB">Note: the speaker of this sound file is from Rio de Janeiro, and he is talking about his experience with ''nordestino'' and ''nortista'' accents. – more marked in the Sertأ£o (7), where, in the 19th and 20th centuries and especially in the area including and surrounding the ''sertأ£o'' (the dry land after Agreste) of Pernambuco and southern Cearأ،, it could sound less comprehensible to speakers of other Portuguese dialects than Galician or Rioplatense Spanish, and nowadays less distinctive from other variants in the metropolitan cities Zona da Mata, along the coasts. It can be divided in two regional variants, one that includes the northern Maranhأ£o and southern of Piauأ, and other that goes from Cearأ، to Alagoas. # ''Nortista'' or ''amazofonia'' – Most of Amazon Basin states, i.e. North Region, Brazil, Northern Brazil. Before the 20th century, most people from the ''nordestino'' area fleeing the droughts and their associated poverty settled here, so it has some similarities with the Portuguese dialect there spoken. The speech in and around the cities of Belأ©m and Manaus has a more European flavor in phonology, prosody and grammar. # ''Paulistano dialect, Paulistano'' – Variants spoken around Greater Sأ£o Paulo in its maximum definition and more easterly areas of Sأ£o Paulo state, as well as perhaps "educated speech" from anywhere in Sأ£o Paulo (state), the state of Sأ£o Paulo (where it coexists with ''caipira''). ''Caipira'' is the hinterland sociolect of much of the Centro-Sul, Central-Southern half of Brazil, nowadays conservative only in the rural areas and associated with them, that has a historically prestige (sociolinguistics), low prestige in cities as Rio de Janeiro, Curitiba, Belo Horizonte, and until some years ago, in Sأ£o Paulo itself. Sociolinguistics, or what by times is described as "linguistic discrimination, linguistic prejudice", often correlated with Class discrimination, classism, is a polemic topic in the entirety of the country since the times of Adoniran Barbosa#Musical production, Adoniran Barbosa. Also, the "Paulistano" accent was heavily influenced by the presence of immigrants in the city of Sأ£o Paulo, especially the Italians. # ''Sertanejo'' – Center-West Region, Brazil, Center-Western states, and also much of Tocantins and Rondأ´nia. It is closer to ''mineiro'', ''caipira'', ''nordestino'' or ''nortista'' depending on the location. # ''Sulista'' – The variants spoken in the areas between the northern regions of Rio Grande do Sul and southern regions of Sأ£o Paulo state, encompassing most of South Region, Brazil, southern Brazil. The city of Curitiba does have a fairly distinct accent as well, and a relative majority of speakers around and in Florianأ³polis also speak this variant (many speak ''florianopolitano'' or ''manezinho da ilha'' instead, related to the European Portuguese dialects spoken in Azores and Madeira). Speech of northern Paranأ، is closer to that of inland Sأ£o Paulo. # ''Florianopolitan dialect, Florianopolitano'' – Variants heavily influenced by European Portuguese spoken in Florianأ³polis city (due to a heavy immigration movement from Portugal, mainly its Autonomous regions of Portugal, insular regions) and much of its metropolitan area, Grande Florianأ³polis, said to be a continuum between those whose speech most resemble ''sulista'' dialects and those whose speech most resemble ''fluminense'' and European ones, called, often pejoratively, ''manezinho da ilha''. # ''Carioca'' – Not a dialect, but sociolects of the ''fluminense'' variant spoken in an area roughly corresponding to Greater Rio de Janeiro. It appeared after locals came in contact with the Portuguese aristocracy amidst the Transfer of the Portuguese Court to Brazil, Portuguese royal family fled in the early 19th century. There is actually a continuum between Vernacular countryside accents and the ''carioca'' sociolect, and the educated speech (in Portuguese ''norma culta'', which most closely resembles other Brazilian Portuguese standards but with marked recent Portuguese influences, the nearest ones among the country's dialects along ''florianopolitano''), so that not all people native to the state of Rio de Janeiro speak the said sociolect, but most ''carioca'' speakers will use the standard variant not influenced by it that is rather uniform around Brazil depending on context (emphasis or formality, for example). # ''Brasiliense'' – used in Brasأlia and its metropolitan area. It is not considered a dialect, but more of a regional variant – often deemed to be closer to ''fluminense'' than the dialect commonly spoken in most of Goiأ،s, ''sertanejo''. # ''Arco do desflorestamento'' or '':pt:Dialeto da serra amazأ´nica, serra amazأ´nica'' – Known in its region as the "accent of the migrants," it has similarities with ''caipira'', ''sertanejo'' and often ''sulista'' that make it differing from ''amazofonia'' (in the opposite group of Brazilian dialects, in which it is placed along ''nordestino'', ''baiano'', ''mineiro'' and ''fluminense''). It is the most recent dialect, which appeared by the settlement of families from various other Brazilian regions attracted by the cheap land offer in recently Deforestation, deforested areas. # ''Recifense'' – used in Recife and its metropolitan area.

Portugal

#

#''Micaelense (Aأ§ores)''

(Sأ£o Miguel) – Azores. #

– Alentejo (Alentejan Portuguese) #

– Algarve (there is a particular dialect in a small part of western Algarve). #

nbsp;– Districts of Braga and Viana do Castelo (hinterland). #

– Central Portugal (hinterland). #

– Central Portugal. #

nbsp;– Regions of Coimbra and Lisbon (this is a disputed denomination, as Coimbra and is not part of "Estremadura", and the Lisbon dialect has some peculiar features that are not only not shared with that of Coimbra, but also significantly distinct and recognizable to most native speakers from elsewhere in Portugal). #

(Madeiran) – Madeira. #

nbsp;– Regions of the district of Porto and parts of Aveiro, Portugal, Aveiro. #

nbsp;– Trأ،s-os-Montes e Alto Douro.

Other countries and dependencies

* –(Angolan Portuguese) * –

(Cape Verdean Portuguese) * –

(East Timorese Portuguese) * – ''Damaense'' (Damanese Portuguese) and ''Goأھs'' (Goan Portuguese) * –

(Guinean Portuguese) * –

(Macanese Portuguese) * –

(Mozambican Portuguese) * –

(Sأ£o Tomean Portuguese) * – Riverense Portuأ±ol language, ''Dialectos Portugueses del Uruguay (DPU)'' Differences between dialects are mostly of Accent (dialect), accent and vocabulary, but between the Brazilian dialects and other dialects, especially in their most colloquial forms, there can also be some grammatical differences. The Portuguese creole, Portuguese-based creoles spoken in various parts of Africa, Asia, and the Americas are independent languages.

Characterization and peculiarities