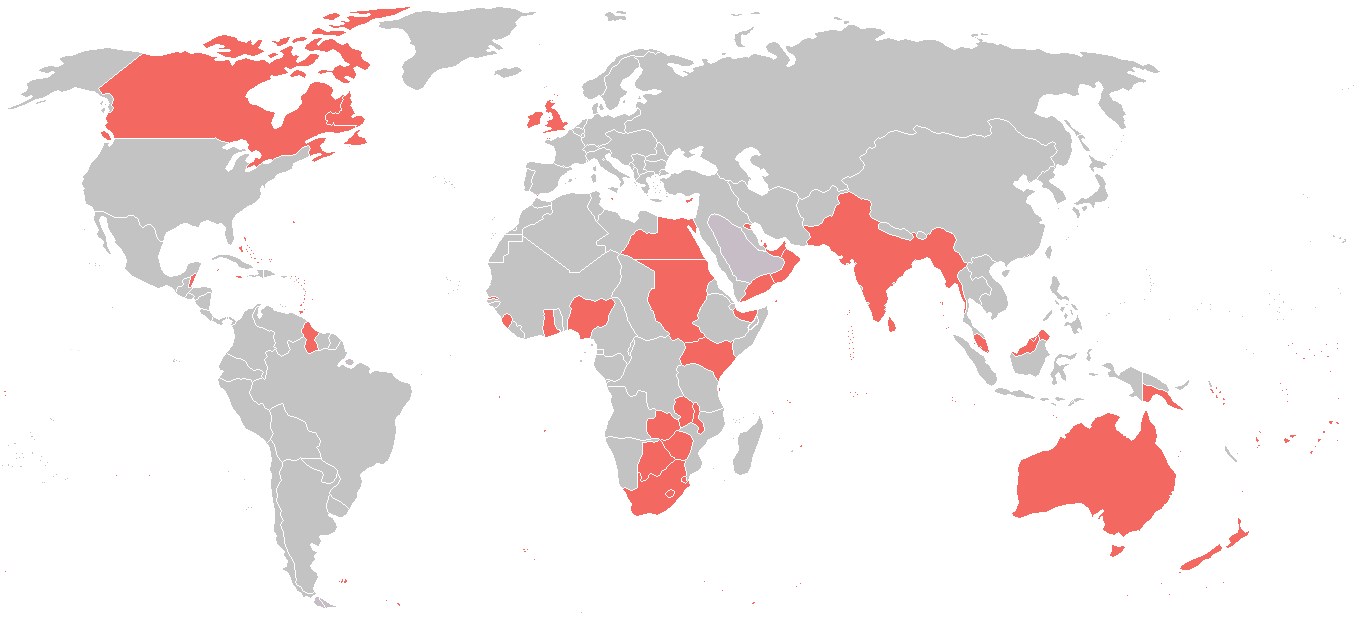

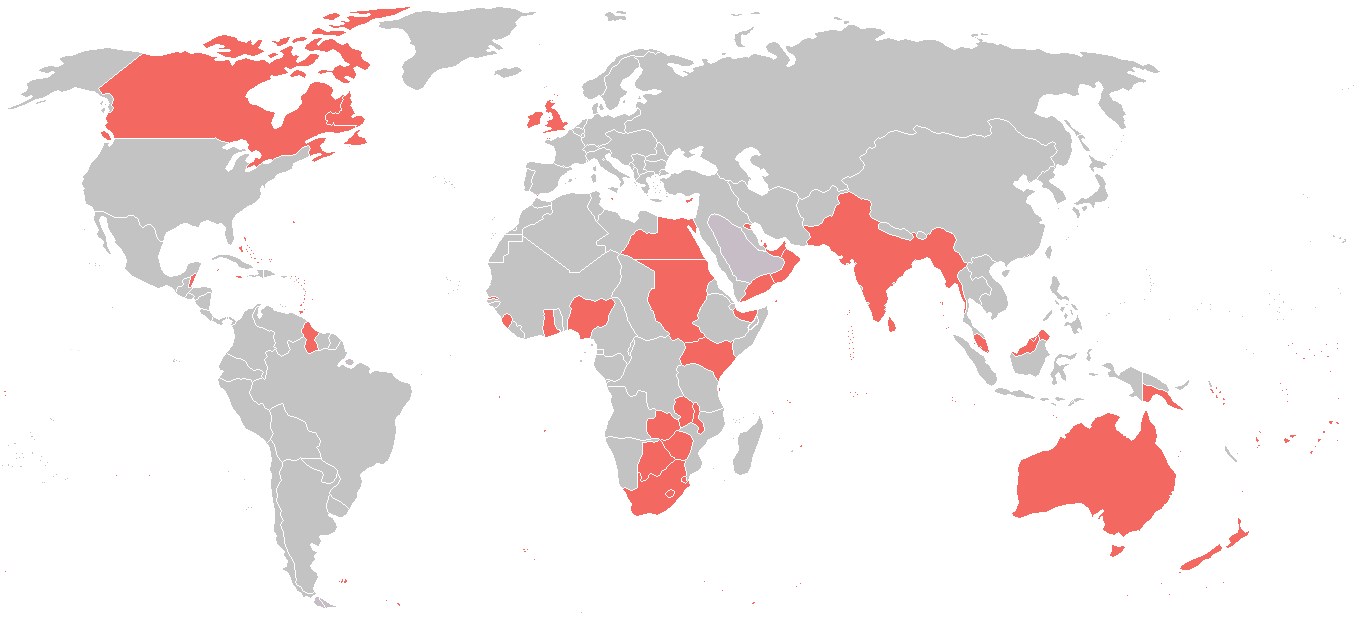

The Allies of World War I,

Entente Powers, or Allied Powers were a

coalition of countries led by

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

,

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

,

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

,

Japan, and the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

against the

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

of

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

,

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

,

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

, and their colonies during the

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

(1914–1918).

By the end of the first decade of the 20th century, the major

European powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

were divided between the

Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

and the

Triple Alliance. The Triple Entente was made up of France, Britain, and Russia. The Triple Alliance was originally composed of Germany, Austria–Hungary, and Italy, but Italy remained neutral in 1914. As the war progressed, each coalition added new members. Japan joined the Entente in 1914 and after proclaiming its neutrality at the beginning of the war, Italy also joined the Entente in 1915. The term "Allies" became more widely used than "Entente", although France, Britain, Russia, and Italy were also referred to as the Quadruple Entente and, together with Japan, as the Quintuple Entente. The colonies administered by the countries that fought for the allies were also part of the Entente Powers such as

British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

,

French Indochina

French Indochina (previously spelled as French Indo-China),; vi, Đông Dương thuộc Pháp, , lit. 'East Ocean under French Control; km, ឥណ្ឌូចិនបារាំង, ; th, อินโดจีนฝรั่งเศส, ...

, and

Japanese Korea.

The United States joined near the end of the war in 1917 (the same year in which Russia withdrew from the conflict) as an "associated power" rather than an official ally. Other "associated members" included

Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hungar ...

,

Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

,

Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = M ...

,

Asir,

Nejd and Hasa,

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

,

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

,

Hejaz,

Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Co ...

,

Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

,

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

,

China,

Siam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

(now

Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

),

Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

,

Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ' ...

,

Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small lan ...

,

Guatemala,

Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the countr ...

,

Costa Rica,

Haiti,

Liberia,

Bolivia,

Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ' ...

,

Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

, and

Honduras. The treaties signed at the

Paris Peace Conference recognised Great Britain, France, Italy, Japan and the United States as 'the Principal Allied and Associated Powers'.

Background

When the war began in 1914, the

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

were opposed by the

Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

, formed in 1907 when the agreement between Britain and the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

complemented existing agreements between Britain, Russia, and France.

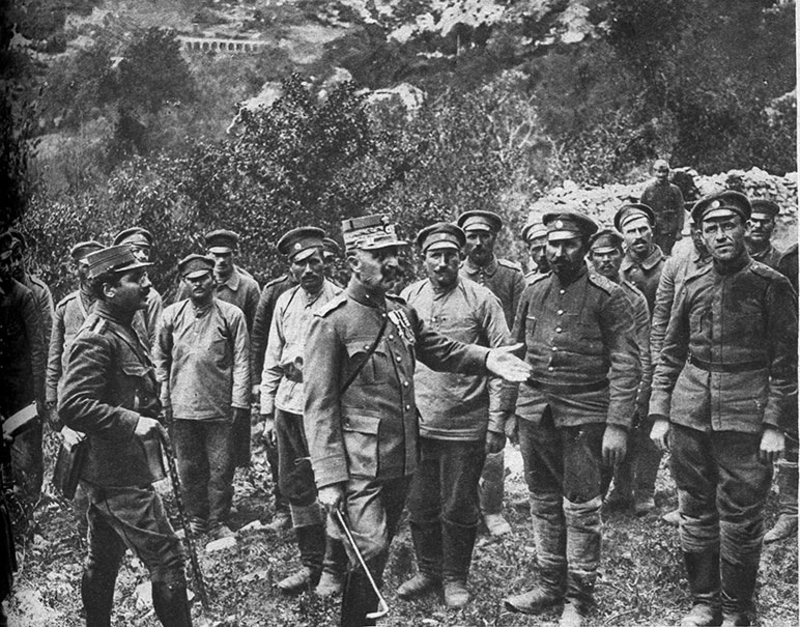

Fighting commenced when Austria invaded

Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hungar ...

on 28 July 1914, purportedly in response to the

assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, were assassinated on 28 June 1914 by Bosnian Serb student Gavrilo Princip. They were shot at close range whil ...

, heir to Emperor

Franz Joseph

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I (german: Franz Joseph Karl, hu, Ferenc József Károly, 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and the other states of the Habsburg monarchy from 2 December 1848 until his ...

; this brought Serbia's ally

Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = M ...

into the war on 8 August and it attacked the Austrian naval base at

Cattaro

Kotor (Montenegrin Cyrillic: Котор, ), historically known as Cattaro (from Italian: ), is a coastal town in Montenegro. It is located in a secluded part of the Bay of Kotor. The city has a population of 13,510 and is the administrative ...

, modern Kotor. At the same time, German troops carried out the

Schlieffen Plan

The Schlieffen Plan (german: Schlieffen-Plan, ) is a name given after the First World War to German war plans, due to the influence of Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen and his thinking on an invasion of France and Belgium, which began on ...

, entering neutral

Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

and

Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small lan ...

; over 95% of Belgium was occupied but the Belgian Army held their lines on the

Yser Front

The Yser Front (french: Front de l'Yser, nl, Front aan de IJzer or ), sometimes termed the West Flemish Front in British writing, was a section of the Western Front during World War I held by Belgian troops from October 1914 until 1918. The front ...

throughout the war. This allowed Belgium to be treated as an Ally, in contrast to Luxembourg which retained control over domestic affairs but was

occupied by the German military.

In the East, between 7 and 9 August the Russians entered German

East Prussia on 7 August, Austrian

Eastern Galicia.

Japan joined the Entente by declaring war on Germany on 23 August, then Austria on 25 August. On 2 September, Japanese forces surrounded the German

Treaty Port

Treaty ports (; ja, 条約港) were the port cities in China and Japan that were opened to foreign trade mainly by the unequal treaties forced upon them by Western powers, as well as cities in Korea opened up similarly by the Japanese Empire.

...

of

Tsingtao

Qingdao (, also spelled Tsingtao; , Mandarin: ) is a major city in eastern Shandong Province. The city's name in Chinese characters literally means " azure island". Located on China's Yellow Sea coast, it is a major nodal city of the One Belt ...

(now Qingdao) in China and occupied German colonies in the Pacific, including the

Mariana,

Caroline, and

Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands ( mh, Ṃajeḷ), officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands ( mh, Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ),'' () is an independent island country and microstate near the Equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the Intern ...

.

Despite its membership of the

Triple Alliance,

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

remained neutral until 23 May 1915 when it joined the Entente, declaring war on Austria but not Germany. On 17 January 1916,

Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = M ...

capitulated and left the Entente; this was offset when Germany declared war on

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

in March 1916, while

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

commenced hostilities against Austria on 27 August.

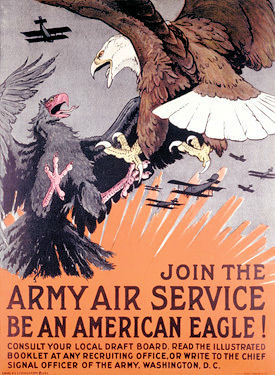

On 6 April 1917, the United States entered the war as a co-belligerent, along with the associated allies of

Liberia,

Siam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

and

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

. After the 1917

October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

, Russia left the Entente and agreed to a separate peace with the Central Powers with the signing of the

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire), that ended Russia's ...

on 3 March 1918. Romania was forced to do the same in the May 1918

Treaty of Bucharest but on 10 November, it repudiated the Treaty and once more declared war on the Central Powers.

These changes meant the Allies who negotiated the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

in 1919 included France, Britain, Italy, Japan and the US; Part One of the Treaty agreed to the establishment of the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

on 25 January 1919. This came into being on 16 January 1920 with Britain, France, Italy and Japan as permanent members of the Executive Council; the

US Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

voted against ratification of the treaty on 19 March, thus preventing the US from joining the League.

Statistics

Principal powers

Britain and its Empire

For much of the 19th century, Britain sought to maintain the European balance of power without formal alliances, a policy known as

splendid isolation. This left it dangerously exposed as Europe divided into opposing power blocs and the

1895–1905 Conservative government negotiated first the 1902

Anglo-Japanese Alliance, then the 1904

Entente Cordiale

The Entente Cordiale (; ) comprised a series of agreements signed on 8 April 1904 between the United Kingdom and the French Republic which saw a significant improvement in Anglo-French relations. Beyond the immediate concerns of colonial de ...

with France. The first tangible result of this shift was British support for France against Germany in the

1905 Moroccan Crisis.

The

1905–1915 Liberal government continued this re-alignment with the 1907

Anglo-Russian Convention

The Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 (russian: Англо-Русская Конвенция 1907 г., translit=Anglo-Russkaya Konventsiya 1907 g.), or Convention between the United Kingdom and Russia relating to Persia, Afghanistan, and Tibet (; ...

. Like the Anglo-Japanese and Entente agreements, it focused on settling colonial disputes but by doing so paved the way for wider co-operation and allowed Britain to refocus resources in response to

German naval expansion.

Since control of Belgium allowed an opponent to threaten invasion or blockade British trade, preventing it was a long-standing British strategic interest. Under Article VII of the 1839

Treaty of London, Britain guaranteed Belgian neutrality against aggression by any other state, by force if required. Chancellor

Bethmann Hollweg later dismissed this as a 'scrap of paper,' but British law officers routinely confirmed it as a binding legal obligation and its importance was well understood by Germany.

The 1911

Agadir Crisis

The Agadir Crisis, Agadir Incident, or Second Moroccan Crisis was a brief crisis sparked by the deployment of a substantial force of French troops in the interior of Morocco in April 1911 and the deployment of the German gunboat to Agadir, a ...

led to secret discussions between France and Britain in case of war with Germany. These agreed that within two weeks of its outbreak, a

British Expeditionary Force of 100,000 men would be landed in France; in addition, the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

would be responsible for the

North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea, epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the ...

, the

Channel and protecting Northern France, with the French navy concentrated in the

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

. Britain was committed to support France in a war against Germany but this was not widely understood outside government or the upper ranks of the military.

As late as 1 August, a clear majority of the Liberal government and its supporters wanted to stay out of the war. While Liberal leaders

H. H. Asquith and

Edward Grey considered Britain legally and morally committed to support France regardless, waiting until Germany triggered the 1839 Treaty provided the best chance of preserving Liberal party unity.

The German high command was aware entering Belgium would lead to British intervention but decided the risk was acceptable; they expected a short war while their ambassador in London claimed troubles in Ireland would prevent Britain from assisting France. On 3 August, Germany demanded unimpeded progress through any part of Belgium and when this was refused, invaded early on the morning of 4 August.

This changed the situation; the invasion of Belgium consolidated political and public support for the war by presenting what appeared to be a simple moral and strategic choice. The Belgians asked for assistance under the 1839 Treaty and in response, Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914. Although Germany's violation of Belgium neutrality was not the only cause of British entry into the war, it was used extensively in government propaganda at home and abroad to make the case for British intervention. This confusion arguably persists today.

The declaration of war automatically involved all dominions and colonies and protectorates of the

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

, many of whom made significant contributions to the Allied war effort, both in the provision of troops and civilian labourers. It was split into

Crown Colonies administered by the

Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created to deal with the colonial affairs of British North America but required also to oversee the increasing number of c ...

in London, such as

Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

, and the self-governing

Dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 192 ...

s of

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

,

Newfoundland,

New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

,

Australia and

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the ...

. These controlled their own domestic policies and military expenditure but not foreign policy.

In terms of population, the largest component (after Britain herself) was the

British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was him ...

or British India, which included modern

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

,

Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

,

Myanmar

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

and

Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

. Unlike other colonies which came under the

Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created to deal with the colonial affairs of British North America but required also to oversee the increasing number of c ...

, it was governed directly by the

India Office or by

princes loyal to the British; it also controlled British interests in the

Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bod ...

, such as the

Trucial States and

Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of ...

. Over one million soldiers of the

British Indian Army served in different theatres of the war, primarily France and the

Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

.

From 1914 to 1916, overall Imperial diplomatic, political and military strategy was controlled by the

British War Cabinet in London; in 1917 it was superseded by the

Imperial War Cabinet

The Imperial War Cabinet (IWC) was the British Empire's wartime coordinating body. It met over three sessions, the first from 20 March to 2 May 1917, the second from 11 June to late July 1918, and the third from 20 or 25 November 1918 to early Jan ...

, which included representatives from the Dominions. Under the War Cabinet were the

Chief of the Imperial General Staff or CIGS, responsible for all Imperial ground forces, and the

Admiralty that did the same for the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

. Theatre commanders like

Douglas Haig

Field Marshal Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig, (; 19 June 1861 – 29 January 1928) was a senior officer of the British Army. During the First World War, he commanded the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front from late 1915 until ...

on the

Western Front or

Edmund Allenby

Field Marshal Edmund Henry Hynman Allenby, 1st Viscount Allenby, (23 April 1861 – 14 May 1936) was a senior British Army officer and Imperial Governor. He fought in the Second Boer War and also in the First World War, in which he led th ...

in

Palestine then reported to the CIGS.

After the Indian Army, the largest individual units were the

Australian Corps

The Australian Corps was a World War I army corps that contained all five Australian infantry divisions serving on the Western Front. It was the largest corps fielded by the British Empire in France. At its peak the Australian Corps numbered 10 ...

and

Canadian Corps in France, which by 1918 were commanded by their own generals,

John Monash

General (Australia), General Sir John Monash, (; 27 June 1865 – 8 October 1931) was an Australian civil engineer and military commander of the First World War. He commanded the 13th Brigade (Australia), 13th Infantry Brigade before the war an ...

and

Arthur Currie

General Sir Arthur William Currie, (5 December 187530 November 1933) was a senior officer of the Canadian Army who fought during World War I. He had the unique distinction of starting his military career on the very bottom rung as a pre-wa ...

. Contingents from South Africa, New Zealand and Newfoundland served in theatres including France,

Gallipoli,

German East Africa and the Middle East. Australian troops separately occupied

German New Guinea

German New Guinea (german: Deutsch-Neu-Guinea) consisted of the northeastern part of the island of New Guinea and several nearby island groups and was the first part of the German colonial empire. The mainland part of the territory, called , ...

, with the South Africans doing the same in

German South West Africa

German South West Africa (german: Deutsch-Südwestafrika) was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. With a total area of ...

; this resulted in the

Maritz rebellion

The Maritz rebellion, also known as the Boer revolt or Five Shilling rebellion,General De Wet publicly unfurled the rebel banner in October, when he entered the town of Reitz at the head of an armed commando. He summoned all the town and dema ...

by former Boers, which was quickly suppressed. After the war, New Guinea and South-West Africa became

Protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its int ...

s, held until 1975 and 1990 respectively.

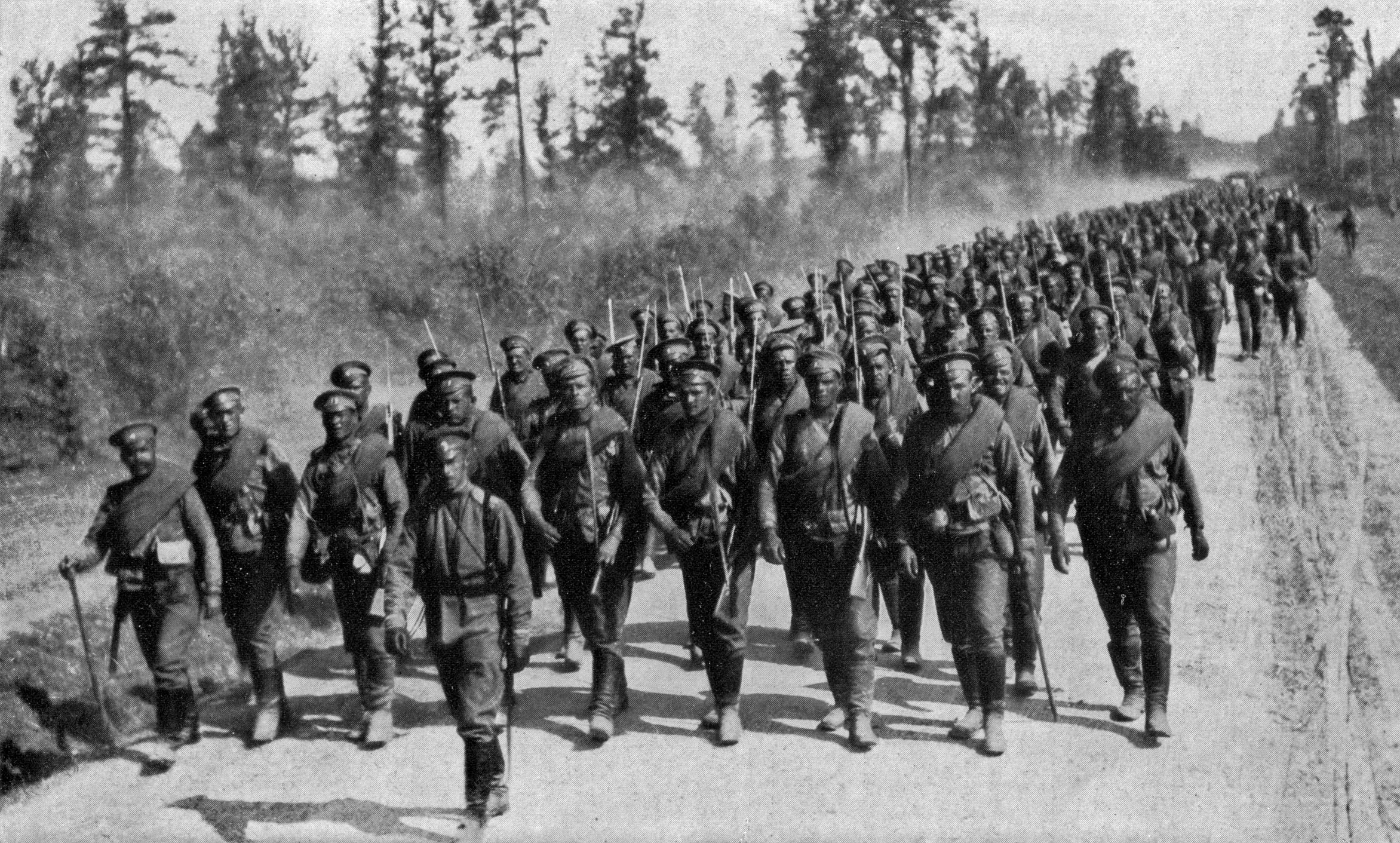

Russian Empire

Between 1873 and 1887, Russia was allied with Germany and Austria-Hungary in the

League of the Three Emperors

The League of the Three Emperors or Union of the Three Emperors (german: Dreikaiserbund) was an alliance between the German, Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires, from 1873 to 1887. Chancellor Otto von Bismarck took full charge of German foreign p ...

, then with Germany in the 1887–1890

Reinsurance Treaty; both collapsed due to the competing interests of Austria and Russia in the

Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

. While France took advantage of this to agree the 1894

Franco-Russian Alliance

The Franco-Russian Alliance (french: Alliance Franco-Russe, russian: Франко-Русский Альянс, translit=Franko-Russkiy Al'yans), or Russo-French Rapprochement (''Rapprochement Russo-Français'', Русско-Французско� ...

, Britain viewed Russia with deep suspicion; in 1800, over 3,000 kilometres separated the Russian Empire and British India, by 1902, it was 30 km in some areas. This threatened to bring the two into direct conflict, as did the long-held Russian objective of gaining control of the

Bosporus Straits and with it access to the British-dominated

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

.

Defeat in the 1905 Russo-Japanese War and Britain's isolation during the 1899–1902

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the South ...

led both parties to seek allies. The

Anglo-Russian Convention

The Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 (russian: Англо-Русская Конвенция 1907 г., translit=Anglo-Russkaya Konventsiya 1907 g.), or Convention between the United Kingdom and Russia relating to Persia, Afghanistan, and Tibet (; ...

of 1907 settled disputes in Asia and allowed the establishment of the Triple Entente with France, which at this stage was largely informal. In 1908, Austria annexed the former Ottoman province of

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of south and southeast Europe, located in the Balkans. Bosnia and H ...

; Russia responded by creating the

Balkan League in order to prevent further Austrian expansion.

In the 1912–1913

First Balkan War

The First Balkan War ( sr, Први балкански рат, ''Prvi balkanski rat''; bg, Балканска война; el, Αʹ Βαλκανικός πόλεμος; tr, Birinci Balkan Savaşı) lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and invo ...

,

Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hungar ...

,

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

and

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

captured most of the remaining Ottoman possessions in Europe; disputes over the division of these resulted in the

Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict which broke out when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, on 16 ( O.S.) / 29 (N.S.) June 1913. Serbian and Greek armies r ...

, in which Bulgaria was comprehensively defeated by its former allies.

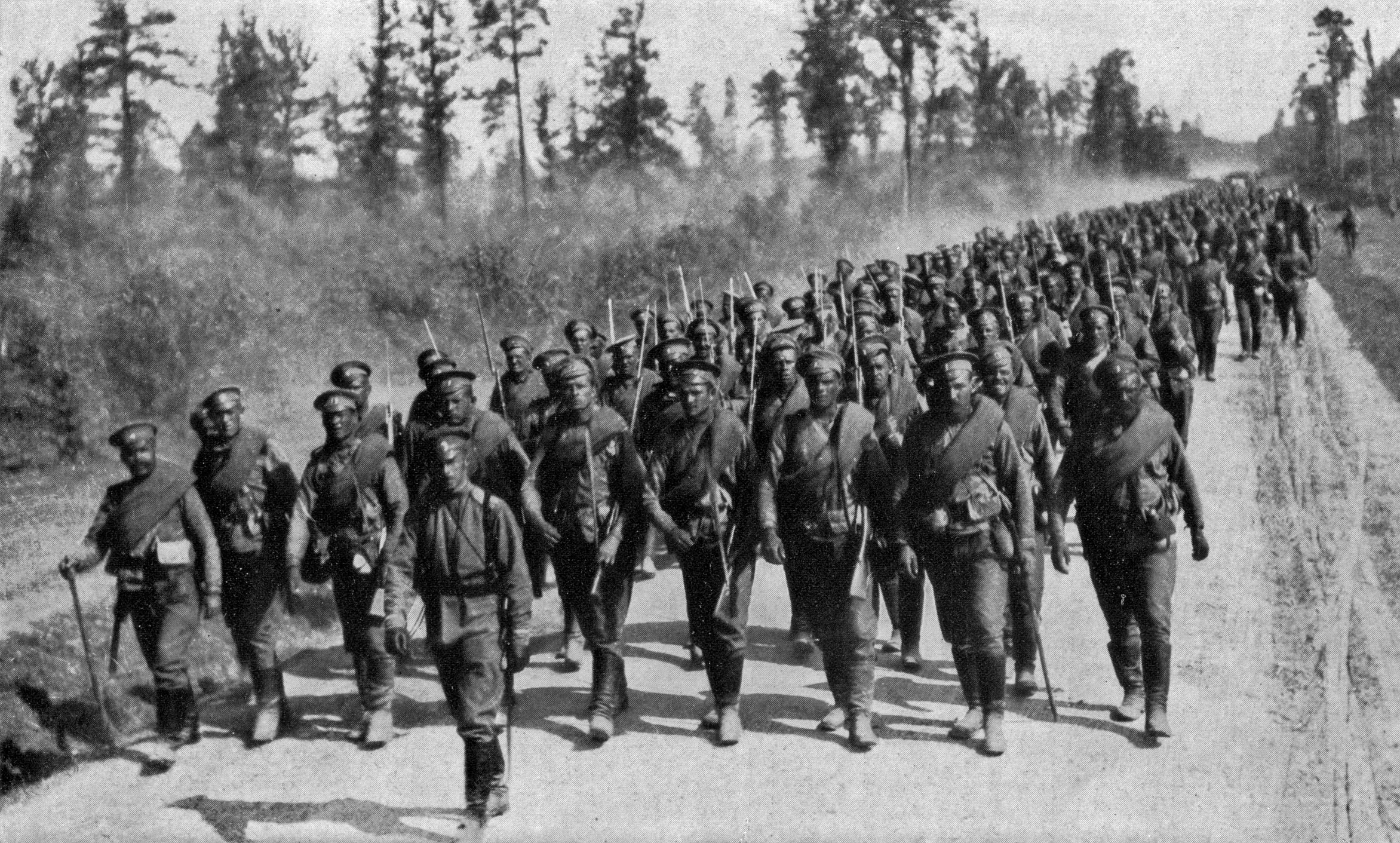

Russia's industrial base and railway network had significantly improved since 1905, although from a relatively low base; in 1913,

Tsar Nicholas approved an increase in the Russian Army of over 500,000 men. Although there was no formal alliance between Russia and Serbia, their close bilateral links provided Russia with a route into the crumbling Ottoman Empire, where Germany also had significant interests. Combined with the increase in Russian military strength, both Austria and Germany felt threatened by Serbian expansion; when Austria invaded Serbia on 28 July 1914, Russian Foreign Minister

Sergey Sazonov viewed it as an Austro-German conspiracy to end Russian influence in the Balkans.

In addition to its own territory, Russia viewed itself as the defender of its fellow

Slavs and on 30 July, mobilised in support of Serbia. In response, Germany declared war on Russia on 1 August, followed by Austria-Hungary on 6th; after Ottoman warships bombarded

Odessa in late October, the Entente declared war on the Ottoman Empire in November 1914.

French Republic

French defeat in the 1870–1871

Franco-Prussian War led to the loss of the two provinces of

Alsace-Lorraine and the establishment of the

Third Republic. The suppression of the

Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defended ...

by the new regime caused deep political divisions and led to a series of bitter political struggles, such as the

Dreyfus affair

The Dreyfus affair (french: affaire Dreyfus, ) was a political scandal that divided the French Third Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolise modern injustice in the Francop ...

. As a result, aggressive nationalism or

Revanchism

Revanchism (french: revanchisme, from ''revanche'', "revenge") is the political manifestation of the will to reverse territorial losses incurred by a country, often following a war or social movement. As a term, revanchism originated in 1870s Fr ...

was one of the few areas to unite the French.

The loss of Alsace-Lorraine deprived France of its natural defence line on the

Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

, while it was weaker demographically than Germany, whose 1911 population was 64.9 million to 39.6 in France, which had the lowest birthrate in Europe. This meant that despite their very different political systems, when Germany allowed the Reinsurance Treaty to lapse, France seized the opportunity to agree the 1894

Franco-Russian Alliance

The Franco-Russian Alliance (french: Alliance Franco-Russe, russian: Франко-Русский Альянс, translit=Franko-Russkiy Al'yans), or Russo-French Rapprochement (''Rapprochement Russo-Français'', Русско-Французско� ...

. It also replaced Germany as the primary source of financing for Russian industry and the expansion of its railway network, particularly in border areas with Germany and Austria-Hungary.

However, Russian defeat in the 1904–1905

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

damaged its credibility, while Britain's isolation during the

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the South ...

meant both countries sought additional allies. This resulted in the 1904

Entente Cordiale

The Entente Cordiale (; ) comprised a series of agreements signed on 8 April 1904 between the United Kingdom and the French Republic which saw a significant improvement in Anglo-French relations. Beyond the immediate concerns of colonial de ...

with Britain; like the 1907

Anglo-Russian Convention

The Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 (russian: Англо-Русская Конвенция 1907 г., translit=Anglo-Russkaya Konventsiya 1907 g.), or Convention between the United Kingdom and Russia relating to Persia, Afghanistan, and Tibet (; ...

, for domestic British consumption it focused on settling colonial disputes but led to informal co-operation in other areas. By 1914, both the British army and

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

were committed to support France in the event of war with Germany but even in the British government, very few were aware of the extent of these commitments.

In response to Germany's declaration of war on Russia, France issued a general mobilisation in expectation of war on 2 August and on 3 August, Germany also declared war on France. Germany's ultimatum to Belgium brought Britain into the war on 4 August, although France did not declare war on Austria-Hungary until 12 August.

As with Britain, France's

colonies

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

also became part of the war; pre-1914, French soldiers and politicians advocated using French African recruits to help compensate for France's demographic weakness. From August to December 1914, the French lost nearly 300,000 dead on the Western Front, more than Britain suffered in the whole of WWII and the gaps were partly filled by colonial troops, over 500,000 of whom served on the Western Front over the period 1914–1918. Colonial troops also fought at

Gallipoli, occupied

Togo

Togo (), officially the Togolese Republic (french: République togolaise), is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Ghana to the west, Benin to the east and Burkina Faso to the north. It extends south to the Gulf of Guinea, where its c ...

and

Kamerun

Kamerun was an African colony of the German Empire from 1884 to 1916 in the region of today's Republic of Cameroon. Kamerun also included northern parts of Gabon and the Congo with western parts of the Central African Republic, southwestern ...

in West Africa and had a minor role in the Middle East, where France was the traditional protector of Christians in the Ottoman provinces of

Syria,

Palestine and

Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

.

Japanese Empire

Prior to the

Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ...

in 1868, Japan was a semi-feudal, largely agrarian state with few natural resources and limited technology. By 1914, it had transformed itself into a modern industrial state, with a powerful military; by defeating China in the

First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894 – 17 April 1895) was a conflict between China and Japan primarily over influence in Korea. After more than six months of unbroken successes by Japanese land and naval forces and the loss of the ...

during 1894–1895, it established itself as the primary power in East Asia and colonised the then-unified Korea and

Formosa, now modern Taiwan.

Concerned by Russian expansion in Korea and

Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

, Britain and Japan signed the

Anglo-Japanese Alliance on 30 January 1902, agreeing if either were attacked by a third party, the other would remain neutral and if attacked by two or more opponents, the other would come to its aid. This meant Japan could rely on British support in a war with Russia, if either France or Germany, which also had interests in China, decided to join them. This gave Japan the reassurance needed to take on Russia in the 1905

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

; victory established Japan in the Chinese province of

Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

.

With Japan as an ally in the Far East,

John Fisher

John Fisher (c. 19 October 1469 – 22 June 1535) was an English Catholic bishop, cardinal, and theologian. Fisher was also an academic and Chancellor of the University of Cambridge. He was canonized by Pope Pius XI.

Fisher was executed by o ...

,

First Sea Lord

The First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff (1SL/CNS) is the military head of the Royal Navy and Naval Service of the United Kingdom. The First Sea Lord is usually the highest ranking and most senior admiral to serve in the British Armed Fo ...

from 1904 to 1910, was able to refocus British naval resources in the

North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea, epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the ...

to counter the threat from the

Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the Imperial Navy () was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for coast defence. Kaise ...

. The Alliance was renewed in 1911; in 1914, Japan joined the Entente in return for German territories in the Pacific, greatly annoying the Australian government which also wanted them.

On 7 August, Britain officially asked for assistance in destroying German naval units in China and Japan formally declared war on Germany on 23 August, followed by Austria-Hungary on 25th. On 2 September 1914, Japanese forces surrounded the German

Treaty Port

Treaty ports (; ja, 条約港) were the port cities in China and Japan that were opened to foreign trade mainly by the unequal treaties forced upon them by Western powers, as well as cities in Korea opened up similarly by the Japanese Empire.

...

of

Qingdao, then known as Tsingtao, which surrendered on 7 November. The

Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrend ...

simultaneously occupied German colonies in the

Mariana,

Caroline, and

Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands ( mh, Ṃajeḷ), officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands ( mh, Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ),'' () is an independent island country and microstate near the Equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the Intern ...

, while in 1917, a Japanese naval squadron was sent to support the Allies in the

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

.

Japan's primary interest was in China and in January 1915, the Chinese government was presented with a secret ultimatum of

Twenty-One Demands

The Twenty-One Demands ( ja, 対華21ヶ条要求, Taika Nijūikkajō Yōkyū; ) was a set of demands made during the First World War by the Empire of Japan under Prime Minister Ōkuma Shigenobu to the government of the Republic of China on 18 ...

, demanding extensive economic and political concessions. While these were eventually modified, the result was a surge of anti-Japanese

nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

in China and an economic boycott of Japanese goods. In addition, the other Allies now saw Japan as a threat, rather than a partner, lead to tensions first with Russia, then the US after it entered the war in April 1917. Despite protests from the other Allies, after the war Japan refused to return Qingdao and the province of

Shandong to China.

Kingdom of Italy

The 1882

Triple Alliance between Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy was renewed at regular intervals, but was compromised by conflicting objectives between Italy and Austria in the

Adriatic and

Aegean seas. Italian nationalists referred to Austrian-held

Istria (including

Trieste

Trieste ( , ; sl, Trst ; german: Triest ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital city, and largest city, of the autonomous region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, one of two autonomous regions which are not subdivided into prov ...

and

Fiume) and

Trento

Trento ( or ; Ladin and lmo, Trent; german: Trient ; cim, Tria; , ), also anglicized as Trent, is a city on the Adige River in Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol in Italy. It is the capital of the autonomous province of Trento. In the 16th ce ...

as

'the lost territories', making the Alliance so controversial that the terms were kept secret until it expired in 1915.

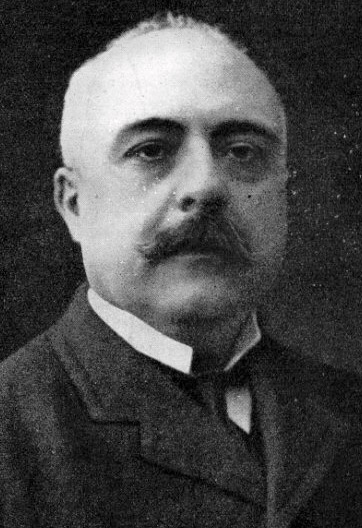

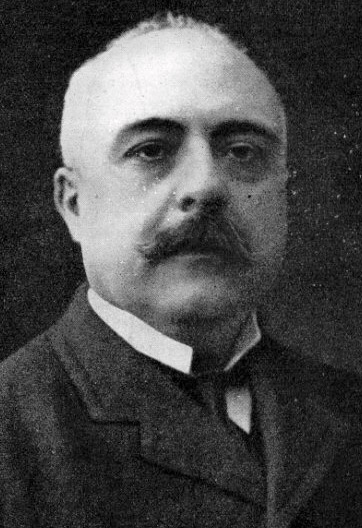

Alberto Pollio, the pro-Austrian

Chief of Staff of the Italian Army

The Chief of Staff of the Italian Army refers to the Chiefs of Staffs of the Royal Italian Army from 1882 to 1946 and the Italian Army from 1946 to the present.

List of chiefs of staff

Chiefs of Staff of the Royal Italian Army (1882–1946)

...

, died on 1 July 1914, taking many of the prospects for Italian support with him. The Italian Prime Minister

Antonio Salandra

Antonio Salandra (13 August 1853 – 9 December 1931) was a conservative Italian politician who served as the 21st prime minister of Italy between 1914 and 1916. He ensured the entry of Italy in World War I on the side of the Triple Entente (the ...

argued that as the Alliance was defensive in nature, Austria's aggression against Serbia and Italy's exclusion from the decision-making process meant it was not obliged to join them.

[Hamilton, Richard F; Herwig, Holger H. Decisions for War, 1914–1917. P194.]

His caution was understandable because France and Britain either supplied or controlled the import of most of Italy's raw materials, including 90% of its coal.

Salandra described the process of choosing a side as 'sacred egoism,' but as the war was expected to end before mid-1915 at the latest, making this decision became increasingly urgent. In line with Italy's obligations under the Triple Alliance, the bulk of the army was concentrated on Italy's border with France; in October, Pollio's replacement,

General Luigi Cadorna, was ordered to begin moving these troops to the North-Eastern one with Austria.

Under the April 1915

Treaty of London, Italy agreed to join the Entente in return for Italian-populated territories of Austria-Hungary and other concessions; in return, it declared war on Austria-Hungary in May 1915 as required, although not on Germany until 1916.

[Hamilton, Richard F; Herwig, Holger H. Decisions for War, 1914–1917. P194-198.] Italian resentment at the difference between the promises of 1915 and the actual results of the 1919

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

would be powerful factors in the rise of

Benito Mussolini.

Affiliated state combatants

Kingdom of Serbia

In 1817, the

Principality of Serbia

The Principality of Serbia ( sr-Cyrl, Књажество Србија, Knjažestvo Srbija) was an autonomous state in the Balkans that came into existence as a result of the Serbian Revolution, which lasted between 1804 and 1817. Its creation wa ...

became an autonomous province within the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

; with Russian support, it gained full independence after the 1877–1878

Russo-Turkish War

The Russo-Turkish wars (or Ottoman–Russian wars) were a series of twelve wars fought between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire between the 16th and 20th centuries. It was one of the longest series of military conflicts in European histo ...

. Many Serbs viewed Russia as protector of the

South Slavs

South Slavs are Slavic peoples who speak South Slavic languages and inhabit a contiguous region of Southeast Europe comprising the eastern Alps and the Balkan Peninsula. Geographically separated from the West Slavs and East Slavs by Austria, ...

in general but also specifically against Bulgaria, where Russian objectives increasingly collided with

Bulgarian nationalism

Bulgarian irredentism is a term to identify the territory associated with a historical national state and a modern Bulgarian irredentist nationalist movement in the 19th and 20th centuries, which would include most of Macedonia, Thrace and ...

.

When Austria annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908, Russia responded by creating the

Balkan League to prevent further Austrian expansion.

Austria viewed Serbia with hostility partly due to its links with Russia, whose claim to be the protector of South Slavs extended to those within the Austro-Hungarian Empire, such as the

Czechs

The Czechs ( cs, Češi, ; singular Czech, masculine: ''Čech'' , singular feminine: ''Češka'' ), or the Czech people (), are a West Slavic ethnic group and a nation native to the Czech Republic in Central Europe, who share a common ancestry, ...

and

Slovaks. Serbia also potentially gave Russia the ability to achieve their long-held objective of capturing

Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

and the

Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

.

Austria backed the

Albanian revolt of 1910 and the idea of a

Greater Albania

Greater Albania is an irredentist and nationalist concept that seeks to unify the lands that many Albanians consider to form their national homeland. It is based on claims on the present-day or historical presence of Albanian populations in th ...

, since this would prevent Serbian access to the Austrian-controlled

Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to t ...

. Another

Albanian revolt in 1912 exposed the weakness of the Ottoman Empire and led to the 1912–1913

First Balkan War

The First Balkan War ( sr, Први балкански рат, ''Prvi balkanski rat''; bg, Балканска война; el, Αʹ Βαλκανικός πόλεμος; tr, Birinci Balkan Savaşı) lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and invo ...

, with

Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hungar ...

,

Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = M ...

,

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

and

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

capturing most of the remaining Ottoman possessions in Europe. Disputes over the division of these resulted in the

Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict which broke out when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, on 16 ( O.S.) / 29 (N.S.) June 1913. Serbian and Greek armies r ...

, in which Bulgaria was comprehensively defeated by its former allies.

As a result of the 1913

Treaty of Bucharest, Serbia increased its territory by 100% and its population by 64%. However, it now faced a hostile Austria-Hungary, a resentful Bulgaria and opposition by Albanian nationalists. Germany too had ambitions in the Ottoman Empire, the centrepiece being the planned

Berlin–Baghdad railway, with Serbia the only section not controlled by a pro-German state.

The exact role played by Serbian officials in the

assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, were assassinated on 28 June 1914 by Bosnian Serb student Gavrilo Princip. They were shot at close range whil ...

is still debated but despite complying with most of their demands, Austria-Hungary invaded on 28 July 1914. While Serbia successfully repulsed the Austro-Hungarian army in 1914, it was exhausted by the two Balkan Wars and unable to replace its losses of men and equipment. In 1915, Bulgaria joined the Central Powers and by the end of the year, a combined Bulgar-Austrian-German army occupied most of Serbia. Between 1914 and 1918, Serbia suffered the greatest proportional losses of any combatant, with over 25% of all those mobilised becoming casualties; including civilians and deaths from disease, over 1.2 million died, nearly 30% of the entire population.

Kingdom of Belgium

In 1830, the southern provinces of the Netherlands broke away to form the

Kingdom of Belgium and their independence was confirmed by the 1839

Treaty of London. Article VII of the Treaty required Belgium to remain perpetually neutral and committed Austria, France, Germany and Russia to guarantee that against aggression by any other state, including the signatories.

While the French and German militaries accepted Germany would almost certainly violate Belgian neutrality in the event of war, the extent of that was unclear. The original

Schlieffen Plan

The Schlieffen Plan (german: Schlieffen-Plan, ) is a name given after the First World War to German war plans, due to the influence of Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen and his thinking on an invasion of France and Belgium, which began on ...

only required a limited incursion into the Belgian

Ardennes, rather than a full-scale invasion; in September 1911, the Belgian Foreign Minister told a British Embassy official they would not call for assistance if the Germans limited themselves to that.

While neither Britain or France could allow Germany to occupy Belgium unopposed, a Belgian refusal to ask for help would complicate matters for the

British Liberal government, which contained a significant isolationist element.

However, the key German objective was to avoid war on two fronts; France had to be defeated before Russia could fully mobilise and give time for German forces to be transferred to the East. The growth of the Russian railway network and increase in speed of mobilisation made rapid victory over France even more important; to accommodate the additional 170,000 troops approved by the 1913 Army Bill, the 'incursion' now became a full-scale invasion. The Germans accepted the risk of British intervention; in common with most of Europe, they expected it to be a short war while their London Ambassador claimed civil war in Ireland would prevent Britain from assisting its Entente partners.

On 3 August, a German ultimatum demanded unimpeded progress through any part of Belgium, which was refused. Early on the morning of 4 August, the Germans invaded and the Belgian government called for British assistance under the 1839 Treaty; by the end of 1914, over 95% of the country was occupied but the Belgian Army held their lines on the

Yser Front

The Yser Front (french: Front de l'Yser, nl, Front aan de IJzer or ), sometimes termed the West Flemish Front in British writing, was a section of the Western Front during World War I held by Belgian troops from October 1914 until 1918. The front ...

throughout the war.

In the

Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

, 25,000 Congolese troops plus an estimated 260,000 porters joined British forces in the 1916

East African Campaign. By 1917, they controlled the western part of

German East Africa which would become the Belgian

League of Nations Mandate of

Ruanda-Urundi or modern-day

Rwanda and

Burundi.

Kingdom of Greece

Greece almost doubled in size as a result of the

Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913, but the success masked deep divisions within the political elite. In 1908, the island of

Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

, formally part of the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

but administered by Greek officials, declared union with Greece, led by the charismatic nationalist

Eleftherios Venizelos. A year later, young army officers formed the Military League to advocate for an aggressive and expansionist foreign policy; with their backing, Venizelos won a majority in the 1910 Parliamentary elections, followed by another in 1912. He had effectively broken the power of the pre-1910 political class and his position was then further strengthened by success in the Balkan Wars.

In 1913, the Greek monarch

George I George I or 1 may refer to:

People

* Patriarch George I of Alexandria (fl. 621–631)

* George I of Constantinople (d. 686)

* George I of Antioch (d. 790)

* George I of Abkhazia (ruled 872/3–878/9)

* George I of Georgia (d. 1027)

* Yuri Dolgor ...

was assassinated; he was succeeded by his son

Constantine who had attended

Heidelberg University

}

Heidelberg University, officially the Ruprecht Karl University of Heidelberg, (german: Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg; la, Universitas Ruperto Carola Heidelbergensis) is a public university, public research university in Heidelberg, B ...

, served in a Prussian regiment and married

Sophia of Prussia, sister of Emperor

William II. These links and a belief the Central Powers would win the war combined to make Constantine pro-German.

Venizelos himself favoured the Entente, partly due to their ability to block the maritime trade routes required for Greek imports.

Other issues adding complexity to this decision included disputes with Bulgaria and Serbia over the regions of

Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

and

Macedonia as well as control of the

Aegean Islands. Greece captured most of the islands during the Balkan Wars but Italy occupied the

Dodecanese in 1912 and was in no hurry to give them back, while the Ottomans demanded the return of many others. In general, the Triple Entente favoured Greece, the Triple Alliance backed the Ottomans; Greece ultimately gained the vast majority but Italy did not cede the Dodecanese until 1947, while others remain

disputed even today.

As a result, Greece initially remained neutral but in March 1915, the Entente offered concessions to join the

Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

campaign. Arguments over whether to accept led to the

National Schism, with an Entente-backed administration under Venizelos in Crete, and a Royalist one led by Constantine in

Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

that supported the Central Powers.

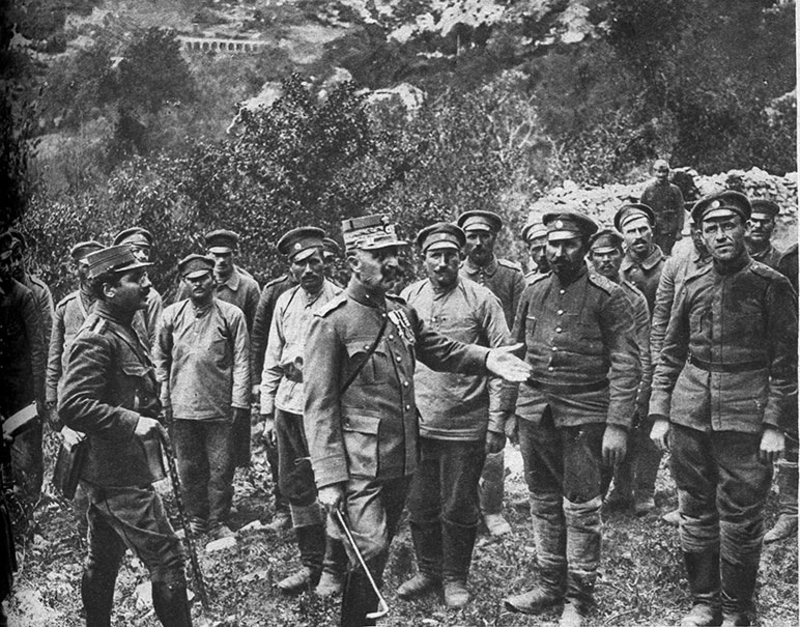

In September 1915, Bulgaria joined the Central Powers; in October, Venizelos allowed Entente forces to land at

Thessaloniki or Salonica to support the Serbs, although they were too late to prevent their defeat. In August 1916, Bulgarian troops advanced into Greek-held Macedonia and Constantine ordered the army not to resist; anger at this led to a coup and he was eventually forced into exile in June 1917. A new national government under Venizelos joined the Entente, while the Greek

National Defence Army Corps

The Army of National Defence ( el, Στρατός Εθνικής Αμύνης) was the military force of the Provisional Government of National Defence, a pro- Allied government led by Eleftherios Venizelos in Thessaloniki in 1916–17, against the ...

fought with the Allies on the

Macedonian front.

Kingdom of Montenegro

Unlike Serbia, with whom it shared close cultural and political connections, the

Kingdom of Montenegro

The Kingdom of Montenegro ( sr, Краљевина Црна Горa, Kraljevina Crna Gora) was a monarchy in southeastern Europe, present-day Montenegro, during the tumultuous period of time on the Balkan Peninsula leading up to and during World ...

gained little from its participation in the 1912–1913 Balkan Wars. The main Montenegrin offensive was in

Ottoman-controlled Albania, where it suffered heavy losses during the seven month

Siege of Scutari. Austria-Hungary opposed Serb or Montenegrin control of Albania, since it provided access to the

Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to t ...

; despite Scutari's surrender, Montenegro was forced to relinquish it by the

1913 Treaty of London and it became capital of the short-lived

Principality of Albania

The Principality of Albania ( al, Principata e Shqipërisë or ) refers to the short-lived monarchy in Albania, headed by Wilhelm, Prince of Albania, that lasted from the Treaty of London of 1913 which ended the First Balkan War, through ...

. This was largely an Austrian creation; the new ruler,

William, Prince of Albania, was a German who was forced into exile in September, only seven months after taking up his new position and later served with the

Imperial German Army.

In addition to the lack of substantive gains from the Balkan Wars, there were long-running internal divisions between those who like

Nicholas I preferred an independent Montenegro and those who advocated union with Serbia. In July 1914, Montenegro was not only militarily and economically exhausted, but also faced a multitude of political, economic and social issues.

At meetings held in March 1914, Austria-Hungary and Germany agreed union with Serbia must be prevented; Montenegro could either remain independent or be divided, its coastal areas becoming part of Albania, while the rest could join Serbia.

Nicholas seriously considered neutrality as a way to preserve his dynasty and on 31 July notified the Russian Ambassador Montenegro would only respond to an Austrian attack. He also held discussions with Austria, proposing neutrality or even active support in return for territorial concessions in Albania.

However, close links between the Serbian and Montenegrin militaries as well as popular sentiment meant there was little support for remaining neutral, especially after Russia joined the war; on 1 August, the National Assembly declared war on Austria-Hungary in fulfilment of its obligations to Serbia. After some initial success, in January 1916, the Montenegrin Army was forced to surrender to an Austro-Hungarian force.

Beda Sultanate

The

Beda Sultanate was invaded by Ottoman forces in February 1915 and March 1916.

Britain assisted the Beda Sultanate in defeating the Ottoman invasions by sending arms and ammunition.

Idrisid Emirate of Asir

The

Idrisid Emirate of Asir participated in the

Arab Revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية, ) or the Great Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية الكبرى, ) was a military uprising of Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. On ...

. Its Emir,

Muhammad ibn Ali al-Idrisi, signed an agreement with the British and joined the Allies in May 1915.

Emirate of Nejd and Hasa

The

Emirate of Nejd and Hasa launched a failed offensive against the Ottoman aligned Emirate of Jabal Shammar in January 1915. It then agreed to enter the war as an ally of Britain in the

Treaty of Darin on 26 December 1915.

Kingdom of Romania

Equal status with the main Entente Powers was one of the primary conditions for Romania's entry into the War. The Powers officially recognised this status through the

1916 Treaty of Bucharest. Romania fought on three of the four European Fronts:

Eastern

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air Li ...

,

Balkan and

Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

, fielding in total over 1,200,000 troops.

Romanian military industry was mainly focused on converting various fortification guns into field and anti-aircraft artillery. Up to 334 German 53 mm

Fahrpanzer

The Fahrpanzer was a mobile artillery piece made prior to World War I in Germany, implemented in several German fortifications from 1890 onwards and exported to several foreign military powers prior to the outbreak of hostilities.

Specificatio ...

guns, 93 French 57 mm Hotchkiss guns, 66 Krupp 150 mm guns, and dozens more 210 mm guns were mounted on Romanian-built

carriages and transformed into mobile field artillery, with 45 Krupp 75 mm guns and 132 Hotchkiss 57 mm guns being transformed into anti-aircraft artillery. The Romanians also

upgraded 120 German Krupp 105 mm howitzers, the result being the most effective field howitzer in Europe at that time. Romania even managed to design and build from scratch its own model of mortar, the 250 mm Negrei Model 1916.

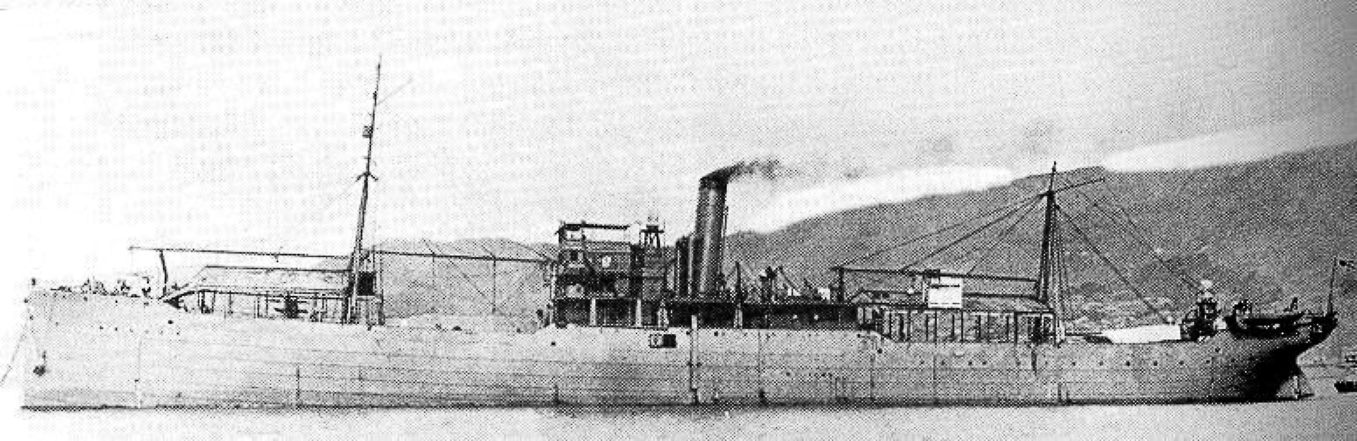

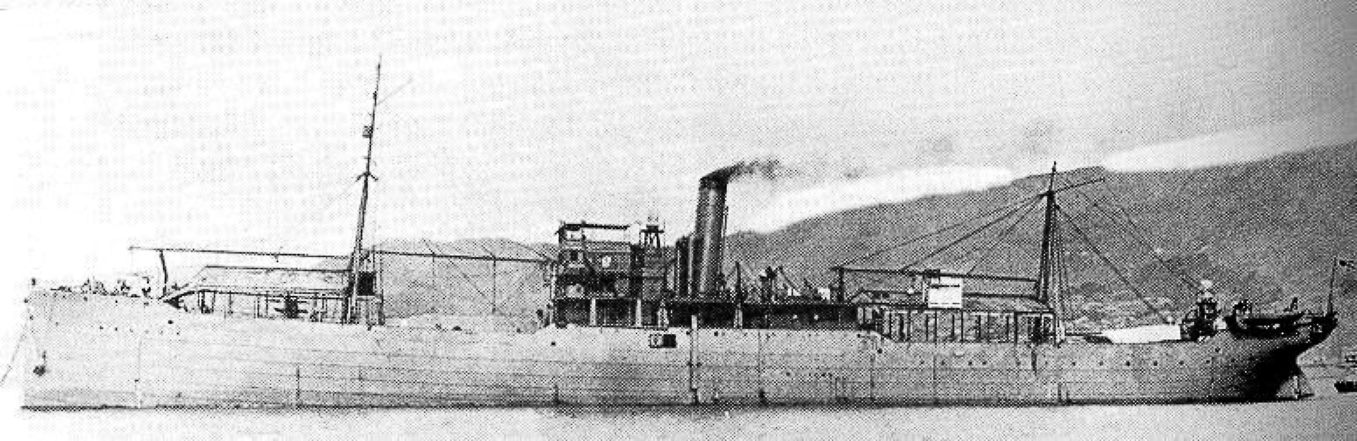

Other Romanian technological assets include the building of

Vlaicu III, the world's first aircraft made of metal. The Romanian Navy possessed the largest warships on the Danube. They were a class of four river monitors, built locally at the

Galați shipyard __NOTOC__

The Galați shipyard ( ro, Șantierul naval Galați), formally Damen Shipyards Galați, is a shipyard located on the Danube in Galați, a city located in the Moldavia region of Romania.

History Origins through communism

Shipbuilding is ...

using parts manufactured in Austria-Hungary. The first one launched was ''Lascăr Catargiu'', in 1907. The Romanian monitors displaced almost 700 tons, were armed with three 120 mm naval guns in three turrets, two 120 mm naval howitzers, four 47 mm anti-aircraft guns and two 6.5 machine guns. The monitors took part in the

Battle of Turtucaia and the

First Battle of Cobadin. The Romanian-designed Schneider 150 mm Model 1912 howitzer was considered one of the most modern field guns on the Western Front.

Romania's entry into the War in August 1916 provoked major changes for the Germans. General

Erich von Falkenhayn

General Erich Georg Sebastian Anton von Falkenhayn (11 September 1861 – 8 April 1922) was the second Chief of the German General Staff of the First World War from September 1914 until 29 August 1916. He was removed on 29 August 1916 after t ...

was dismissed and sent to command the Central Powers forces in Romania, which enabled

Hindenburg's subsequent ascension to power. Due to having to fight against all of the Central Powers on the longest front in Europe (1,600 km) and with little foreign help (only 50,000 Russians aided 650,000 Romanians in 1916),

the Romanian capital was conquered that December. Vlaicu III was also captured and shipped to Germany, being last seen in 1942. The Romanian administration established a new capital at

Iași and continued to fight on the Allied side in 1917. Despite being relatively short, the Romanian campaign of 1916 provided considerable respite for the Western Allies, as the Germans ceased all their other offensive operations in order to deal with Romania. After suffering a tactical defeat against the Romanians (aided by Russians) in July 1917 at

Mărăști, the Central Powers launched two counterattacks, at

Mărășești

Mărășești () is a small town in Vrancea County, Western Moldavia, Romania. It administers six villages: Călimănești, Haret, Modruzeni, Pădureni, Siretu and Tișița.

Geography

The town is located in the eastern part of the county, on th ...

and

Oituz

Oituz (formerly ''Grozești''; hu, Gorzafalva) is a commune in Bacău County, Western Moldavia, Romania. It is composed of six villages: Călcâi (''Zöldlonka''), Ferestrău-Oituz (''Fűrészfalva''), Hârja (''Herzsa''), Marginea, Oituz and Poi ...

. The German offensive at Mărășești was soundly defeated, with German prisoners later telling their Romanian captors that German casualties were extremely heavy, and that they "had not encountered such stiff resistance since the battles of Somme and Verdun". The Austro-Hungarian offensive at Oituz also failed. On 22 September, the Austro-Hungarian

''Enns''-class river monitor