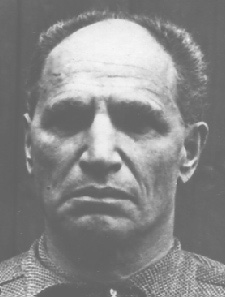

Alexander Krasnoshchyokov on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alexander Mikhailovich Krasnoshchyokov (russian: Алекса́ндр Миха́йлович Краснощёков, real name – Avraam Moiseevich Krasnoshchyok, russian: Абра́м Моисе́евич Краснощёк, October 10, 1880 – November 26, 1937) was a

When Lenin had his third stroke in March 1923, Krasnoshchyokov lost his only protector. He had made powerful enemies, and appears to have become a focus for resentment against private entrepreneurs who were making money in the relaxed conditions of the

When Lenin had his third stroke in March 1923, Krasnoshchyokov lost his only protector. He had made powerful enemies, and appears to have become a focus for resentment against private entrepreneurs who were making money in the relaxed conditions of the

Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

politician

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking ...

and the first Chairman of the Government (Head of the state) of the Far Eastern Republic, and later the first leading Bolshevik to be arrested by the regime.

Early life

Born atChernobyl

Chernobyl ( , ; russian: Чернобыль, ) or Chornobyl ( uk, Чорнобиль, ) is a partially abandoned city in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, situated in the Vyshhorod Raion of northern Kyiv Oblast, Ukraine. Chernobyl is about no ...

, son of a Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

shop assistant, he joined an illegal Marxist group as a teenager in 1896, and the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party soon after it was founded. He was arrested in 1898 and briefly imprisoned, before being exiled to Nikolaievsk where he met Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

. After his release he returned to the Ukraine where he joined Martov in political agitation and organised a workers association in Ekaterinoslav. He was again arrested and imprisoned in 1901. On his release he found himself under constant police surveillance and in November 1902 escaped to Berlin to avoid exile in Siberia. In March 1903, he emigrated to the USA. His first job there was as a house painter. Later, he became a headmaster. He joined the Socialist Labor Party of America and worked as an agitator for the American Federation of Labor. Later he started studying at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chic ...

at the Law School. In 1912 Alexander Krasnoshchyokov graduated from the University and started to work as lawyer. He defended striking workers in the ' Bread and Roses Strike' of 1913. After the February Revolution, he decided to return to Russia, travelling by ship from Vancouver via Japan, where he was interviewed by agents of the Provisional Government.

Return to Russia

Krasnoshchyokov described his return to Russia in his memoirs: "I arrived inVladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, c ...

at the end of July 1917, and immediately joined the Bolshevik faction, was elected to the Soviet in August, and in September was elected to the town duma in Nikolsko-Ussuriysk and President of the Soviet of workers' and soldiers' deputies to represent the Bolsheviks."

After the Bolsheviks seized power in Petrograd (St Petersburg) in November 1917, Krasnoshchyokov led the drive to establish the new regime's authority in the far east, against local resistance. He was president of the Far Eastern Soviet of People's Commissars, which was established in Khabarovsk in December 1917, and for about four months in summer 1918 had control of the entire Russian far east, until it was overthrown by the intervention of Czech, Japanese, British and American forces. Krasnoshchyokov then fled across the taiga, trying to reach territory controlled by the Red Army, but was captured near Samara and sent by 'death train' across Siberia to Irkutsk prison. He was released when the local administration in Irkutsk was overthrown by rioters on 28 December 1919.

Far Eastern Republic

In January 1920, with the civil war nearing an end, Krasnoshchyokov crossed the front line to reach Red Army headquarters inTomsk

Tomsk ( rus, Томск, p=tomsk, sty, Түң-тора) is a city and the administrative center of Tomsk Oblast in Russia, located on the Tom River. Population:

Founded in 1604, Tomsk is one of the oldest cities in Siberia. The city is a n ...

, and persuaded Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

to create a democratic buffer state in the far east, to enable the allied troops in Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive region, geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a ...

to withdraw without loss of face. He wrote the constitution of the Far Eastern Republic in English, before it was translated into Russian, served as first minister and minister for foreign affairs of the Far Eastern Republic from April 1920 to July 1921, and generally made a very good impression on the English and Americans who met him during this period, particularly the journalist H.K.Norton, who wrote an entire book eulogising Krasnoshchyokov's career.

The republic was recognised by the Japanese Army Command May 11, 1920, and by Soviet Russia May 16, 1920. Thanks to his efforts, the Gongota Agreement was signed 15 July 1920 with General Takayanagi of the Japanese Expeditionary Corps. This established a neutral zone between Verkhne-Udinsk and Chita, allowing the Japanese forces, who were under constant pressure from partisans, to withdraw from Transbaikalia without losing face. The Japanese completed this withdrawal (15 October 1920), and Chita was occupied by the partisan NRA 22 October 1920 despite some resistance by the White forces under General Verzhbitsky, who then withdrew south to join Semyonov in Manchuria. Krasnoshchyokov met General Eiche at Chita in early November and Chita became the capital of a state as large as Western Europe. The union of the FER with the Maritime province was finalised 10 November 1920.

Move to Moscow

Krasnoshchyokov was removed from office in April, ostensibly because he had contracted TB, though the real cause appears to have been that local Bolsheviks objected to his leadership style. In December 1921, he was appointed Second Deputy USSR People's Commissar in the People's Commissariat for Finance (Narkomfin), by Lenin, but against the objections of more left wing Bolsheviks, including the future Trotskyist,Yevgeni Preobrazhensky

Yevgeni Alekseyevich Preobrazhensky ( rus, Евге́ний Алексе́евич Преображе́нский, p=jɪvˈɡʲenʲɪj ɐlʲɪˈksʲejɪvʲɪt͡ɕ prʲɪəbrɐˈʐɛnskʲɪj; 1886–1937) was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet economi ...

, who threatened to resign if the appointment was confirmed. In January, Lenin sent a note to the Politburo praising Krasnoshchyokov's "practical approach to financial matters" and insisting that the Politburo back the appointment "to the hilt".

In March 1922, Krasnoshchyokov contracted typhus, and during his absence, his rivals at Narkomfin sacked him. This evoked a long written from Lenin complaining that "We have harassed this man, who undoubtedly has brains, energy, knowledge and experience...We have done everything possible and impossible to repulse this highly energetic, intelligent and valuable worker" and insisting that he be appointed to the Presidium of Vesenkha

Supreme Board of the National Economy, Superior Board of the People's Economy, (Высший совет народного хозяйства, ВСНХ, ''Vysshiy sovet narodnogo khozyaystva'', VSNKh) was the superior state institution for managem ...

The appointment was confirmed by the Politburo in April 1922. He used the opportunity in November 1922 to create Prombank, a new bank to promote trade and industry, leaving the state bank with only the regulation of money and credit, much to the annoyance of the Narkomfin.

In 1922 the American journalist Anna Louise Strong

Anna Louise Strong (November 24, 1885 – March 29, 1970) was an American journalist and activist, best known for her reporting on and support for communist movements in the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China.Archives West,Anna Loui ...

interviewed Krasnoshchyokov about the New Economic Policy

The New Economic Policy (NEP) () was an economic policy of the Soviet Union proposed by Vladimir Lenin in 1921 as a temporary expedient. Lenin characterized the NEP in 1922 as an economic system that would include "a free market and capitalism, ...

(NEP) and about the departure from war communism

War communism or military communism (russian: Военный коммунизм, ''Voyennyy kommunizm'') was the economic and political system that existed in Soviet Russia during the Russian Civil War from 1918 to 1921.

According to Soviet histo ...

. Krasnoshchyokov said:

We must say frankly to the people, "Your government cannot feed all and produce goods for all. We shall run the most necessary industries and feed the workers in those industries. The rest of you must feed yourselves in any way you can." This means we must allow private trade and private workshops; it is well if they succeed enough to feed those people who work in them, since no one else can feed them. Later, as state industries produce a surplus, these will expand and drive out private trade.

Arrest and trial

When Lenin had his third stroke in March 1923, Krasnoshchyokov lost his only protector. He had made powerful enemies, and appears to have become a focus for resentment against private entrepreneurs who were making money in the relaxed conditions of the

When Lenin had his third stroke in March 1923, Krasnoshchyokov lost his only protector. He had made powerful enemies, and appears to have become a focus for resentment against private entrepreneurs who were making money in the relaxed conditions of the New Economic Policy

The New Economic Policy (NEP) () was an economic policy of the Soviet Union proposed by Vladimir Lenin in 1921 as a temporary expedient. Lenin characterized the NEP in 1922 as an economic system that would include "a free market and capitalism, ...

, often in enterprises built on loans provided by Krasnoshchyokov's bank. He was arrested on 19 September 1924 on charges of corruption. Two weeks later, he was denounced in ''Pravda'' and ''Izvestiya'' by the People's Commissar for Workers' and Peasants' Inspection, Kuybyshev, who accused him of using state funds to pay for "disgraceful drunken sprees, enrich his relatives and so on.". It was the first time since the revolution that an eminent Bolshevik had been arrested, and was an overt challenge to Lenin's authority, and created a sensation. Vladimir Ipatiev, a scientist with no affiliation to the Bolsheviks, who was working in Moscow at the time, wrote in his memoirs that "rumours of his wild living were current throughout the city" though this may have only meant that rumours were being successfully put about by Stalin's political machine. Ipatiev was also probably repeating common gossip in his description of Krasnoshchokyov as "a resourceful, capable man but self-centred and hardly a communist out of conviction."

Krasnoshchyokov was tried in March 1924, along with his brother, Yakov, and four bank employees. The main charge a was that the bank had loaned Yakov a large sum at a favourable rate to enable him to set up a privately owned construction firm. He was also accused of paying himself an inflated salary. All six defendants denied the charges, but were found guilty. Alexander Krasnoshchyokov was sentenced to six years in prison and expelled from the communist party. His brother was sentenced to three years, and the other defendants to shorter terms.

Mayakovsky and Lili Brik

In 1922, Krasnoshchyokov had also begun a love affair with Lili Brik, whose most famous lover was the poetVladimir Mayakovsky

Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky (, ; rus, Влади́мир Влади́мирович Маяко́вский, , vlɐˈdʲimʲɪr vlɐˈdʲimʲɪrəvʲɪtɕ məjɪˈkofskʲɪj, Ru-Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky.ogg, links=y; – 14 Apr ...

. Mayakovsky and Brik took care of his daughter, Llewella while he was in prison. In November 1924, Mayakovsky wrote to Brik from Paris complaining: "I love you but all the same you are either someone else's or not mine". She replied: "What can be done about it? I cannot give up A.M. while he is in prison. It would be shameful! More shameful than anything in my entire life." Mayakovsky replied: "Are you really trying to tell me that is...the only thing that prevents you from being with me?"

.

Later life

Krasnoshchyokov was held in the Lefortovo prison in Moscow, where he contractedpneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severi ...

in November 1924. He was transferred then to the government hospital near the Kremlin. He was released under amnesty

Amnesty (from the Ancient Greek ἀμνηστία, ''amnestia'', "forgetfulness, passing over") is defined as "A pardon extended by the government to a group or class of people, usually for a political offense; the act of a sovereign power offici ...

in January 1925 and sent to Yalta

Yalta (: Я́лта) is a resort city on the south coast of the Crimean Peninsula surrounded by the Black Sea. It serves as the administrative center of Yalta Municipality, one of the regions within Crimea. Yalta, along with the rest of Cri ...

to recover. He returned to Moscow in autumn 1925 to work for the Ministry of Agriculture and devoted his energies to improving the cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

crop in Central Asia. By 1930 he was head of an institute dedicated to development of cotton and other fibre crops. He married Donna Gruz and they had twin girls in 1934. He was arrested in July 1937, sentenced to death for espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tangib ...

on 25 November, and was one of several prominent former Bolsheviks shot on 26 November 1937. He was rehabilitated posthumously in 1956, three years after Stalin's death.Robert Argenbright, Marking NEP’s Slippery Path: The Krasnoshchekov Show Trial, Russian Review 61, 2 (2002): 249–75

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Krasnoshchyokov, Alexander 1880 births 1937 deaths People from Chornobyl People from Radomyslsky Uyezd Ukrainian Jews Jews from the Russian Empire Soviet Jews Emigrants from the Russian Empire to the United States Members of the Socialist Labor Party of America category:Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Old Bolsheviks Communist Party of the Soviet Union members Government ministers of the Far Eastern Republic Bolshevik finance Jewish socialists History of Zabaykalsky Krai University of Chicago Law School alumni People of the Russian Civil War Great Purge victims from Ukraine Jews executed by the Soviet Union Soviet rehabilitations