Ahmadiyya in the United States on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The earliest contact between the American people and Ahmadi Muslims in India was during the early era of

The earliest contact between the American people and Ahmadi Muslims in India was during the early era of  Ahmad was an enthusiastic writer and was noted for his extensive correspondences with prominent Americans and Europeans, including some of the leading Christian missionary figureheads of his period. Among them was

Ahmad was an enthusiastic writer and was noted for his extensive correspondences with prominent Americans and Europeans, including some of the leading Christian missionary figureheads of his period. Among them was

Despite the early onset of interactions with the American people, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community only began to prepare for its mission to the United States in 1911, during the era of the First Caliphate. However, it was not until almost a decade later, on January 24, 1920, during the era of the Second Caliphate, that Mufti Muhammad Sadiq, the first missionary to the country, would embark on

Despite the early onset of interactions with the American people, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community only began to prepare for its mission to the United States in 1911, during the era of the First Caliphate. However, it was not until almost a decade later, on January 24, 1920, during the era of the Second Caliphate, that Mufti Muhammad Sadiq, the first missionary to the country, would embark on

In October 1920, within a period of a few months of Sadiq's arrival to New York City, Sadiq moved the headquarters to

In October 1920, within a period of a few months of Sadiq's arrival to New York City, Sadiq moved the headquarters to  In the late 1920s, Sufi Bengalee arrived in the United States and replaced Muhammad Din as a missionary. Bengalee resumed Sadiq's tradition of giving lectures throughout the country. The lectures varied from talks on the life of the Islamic prophet

In the late 1920s, Sufi Bengalee arrived in the United States and replaced Muhammad Din as a missionary. Bengalee resumed Sadiq's tradition of giving lectures throughout the country. The lectures varied from talks on the life of the Islamic prophet

In 1950, the American Ahmadiyya movement shifted their headquarters to Washington, D.C., and established the American Fazl Mosque which served as the headquarters for over four decades, until the early 1990s. The 1950s was an era when many African American musicians were introduced to Islam and thrived as members of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community.

Over the late 20th century, the Ahmadiyya influence on African American Islam subsided to a degree. The Community did not draw as many followers as it did in its early history. Multiple reasons have been postulated for this. Rise of

In 1950, the American Ahmadiyya movement shifted their headquarters to Washington, D.C., and established the American Fazl Mosque which served as the headquarters for over four decades, until the early 1990s. The 1950s was an era when many African American musicians were introduced to Islam and thrived as members of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community.

Over the late 20th century, the Ahmadiyya influence on African American Islam subsided to a degree. The Community did not draw as many followers as it did in its early history. Multiple reasons have been postulated for this. Rise of

In the 1980s,

In the 1980s,

Official website of the U.S. Ahmadiyya Muslim Community

{{Demographics of the United States

Ahmadiyya

Ahmadiyya (, ), officially the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community or the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama'at (AMJ, ar, الجماعة الإسلامية الأحمدية, al-Jamāʿah al-Islāmīyah al-Aḥmadīyah; ur, , translit=Jamā'at Aḥmadiyyah Musl ...

is an Islamic branch in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

. The earliest contact between the American people and the Ahmadiyya movement in Islam was during the lifetime of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad

Mirzā Ghulām Ahmad (13 February 1835 – 26 May 1908) was an Indian religious leader and the founder of the Ahmadiyya movement in Islam. He claimed to have been divinely appointed as the promised Messiah and Mahdi—which is the metaphoric ...

. In 1911, during the era of the First Caliphate of the Community, the Ahmadiyya movement in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

began to prepare for its mission to the United States. However, it was not until 1920, during the era of the Second Caliphate, that Mufti Muhammad Sadiq, under the directive of the caliph, would leave England on SS Haverford

SS ''Haverford'' was an American transatlantic liner commissioned in 1901 for the American Line on the route from Southampton to New York, then quickly on the route from Liverpool to Boston and Philadelphia. During her early years, this ship, ma ...

for the United States. Sadiq established the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in the United States in 1920. The U.S. Ahmadiyya movement is considered by some historians as one of the precursors to the Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

in America. The Community was the most influential Muslim community in African-American Islam until the 1950s. Today, there are approximately 15,000 to 20,000 American Ahmadi Muslims spread across the country.

History

Early contact

The earliest contact between the American people and Ahmadi Muslims in India was during the early era of

The earliest contact between the American people and Ahmadi Muslims in India was during the early era of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad

Mirzā Ghulām Ahmad (13 February 1835 – 26 May 1908) was an Indian religious leader and the founder of the Ahmadiyya movement in Islam. He claimed to have been divinely appointed as the promised Messiah and Mahdi—which is the metaphoric ...

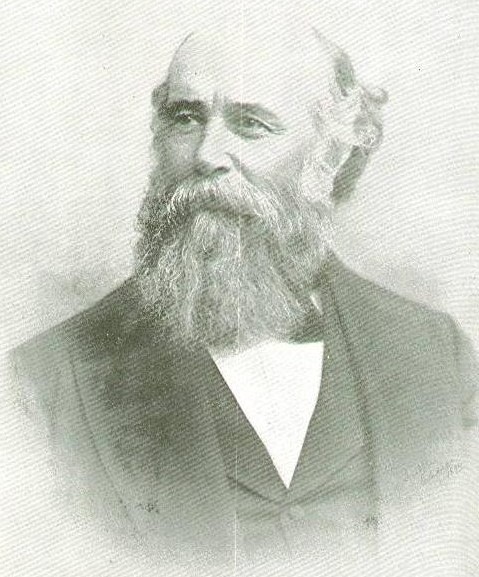

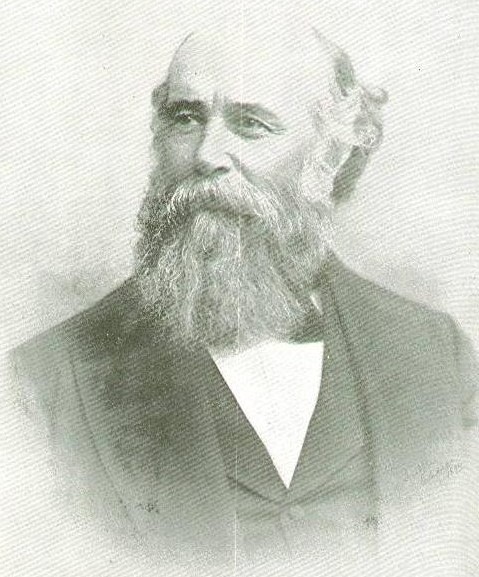

. In 1886, roughly three years prior to the establishment of the Ahmadiyya movement, Alexander Russell Webb

Mohammed Alexander Russell Webb (born Alexander Russell Webb; November 9, 1846 – October 1, 1916) was an American writer, publisher, and the United States Consul to the Philippines. He converted to Islam in 1889, and is considered by histor ...

initiated a correspondence with Ahmad, in response to an advertisement published by the latter. Before 1886, Webb studied several eastern religions, including Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

. His first interaction with the founder of the Ahmadiyya movement was the first serious step towards understanding Islam. The initial correspondence consisted of four letters, two from both sides. Although Webb's letters indicate that he was becoming inclined towards Islam, to the extent of showing willingness to propagate it, the letters do not demonstrate that he had converted to the religion. However, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community does stress that the correspondences were instrumental in Webb's later conversion to the religion. Jane Smith writes that the correspondences were "key to ebb'sconversion to Islam." On his visit to India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

in the early 1890s, Webb stated that it was because of Ahmad that he had the "honour to join Islam." His correspondence with Ahmad began during a period when the latter had gained fame throughout India as one of Islam's leading champions against Christian missionary activity in India during the colonial era. However, after the initial correspondences with Webb, Ahmad quickly became one of Islam's most controversial figures due to his messianic claims. As a result, on his visit to India, Webb abstained from paying a visit to Ahmad. In spite of this, he remained in contact with Ahmad until his death in 1908. In 1906, he wrote to Ahmad, regretting his decision to avoid him:

Although Webb kept in contact with Ahmadis and read Ahmadi literature up until his death in 1916, the Ahmadiyya literature does not record whether Webb was an Ahmadi Muslim, nor does his work show allegiance towards Ahmadiyya eschatology. Today he is known as one of the earliest Anglo-American converts to Islam.

Other early American Muslims who had ties with the movement during Ahmad's lifetime included A. George Baker, a contact of Webb and former Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

clergyman who had converted to Islam. Baker was among a number of European and American figures with whom Mufti Muhammad Sadiq, a disciple of Ahmad, had established contact. He was a subscriber and contributor of the Ahmadi journal '' The Review of Religions'', a journal with which Webb had also corresponded. Baker was mentioned in the fifth volume of Ahmad's ''Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya

''Al-Barāhīn al-Ahmadīyyah 'alā Haqīqatu KitābAllāh al-Qur'ān wa'n-Nabūwwatu al-Muhammadīyyah'' (Ahmadiyya Arguments in Support of the Book of Allah - the Qur'an, and the Prophethood of Muhammad) is a five-part book written by Mirza Ghu ...

'' (1905; The Muhammadan Proofs). He maintained contact with the movement from 1904 until his death in 1918. Unlike Webb, Baker professed allegiance to the Ahmadiyya movement and is counted within it as one of the earliest American Ahmadis.

Ahmad was an enthusiastic writer and was noted for his extensive correspondences with prominent Americans and Europeans, including some of the leading Christian missionary figureheads of his period. Among them was

Ahmad was an enthusiastic writer and was noted for his extensive correspondences with prominent Americans and Europeans, including some of the leading Christian missionary figureheads of his period. Among them was John Alexander Dowie

John Alexander Dowie (25 May 18479 March 1907) was a Scottish-Australian minister known as an evangelist and faith healer. He began his career as a conventional minister in South Australia. After becoming an evangelist and faith healer, he im ...

, a Scottish-born American faith healer, who founded the Christian Catholic Apostolic Church

Christ Community Church in Zion, Illinois, formerly the Christian Catholic Church or Christian Catholic Apostolic Church, is an evangelical non-denominational church founded in 1896 by John Alexander Dowie. The city of Zion was founded by Dowie as ...

and the theocratic

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy originates fro ...

city of Zion

Zion ( he, צִיּוֹן ''Ṣīyyōn'', LXX , also variously transliterated ''Sion'', ''Tzion'', ''Tsion'', ''Tsiyyon'') is a placename in the Hebrew Bible used as a synonym for Jerusalem as well as for the Land of Israel as a whole (see Names ...

, along the banks of Lake Michigan

Lake Michigan is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is the second-largest of the Great Lakes by volume () and the third-largest by surface area (), after Lake Superior and Lake Huron. To the east, its basin is conjoined with that o ...

, and established himself as the "General Overseer" of the theocracy. In December 1899, moments before the turn of the century, Dowie claimed to be God's Messenger and two years later, in 1901, he claimed to be the spiritual return of the Biblical prophet Elijah

Elijah ( ; he, אֵלִיָּהוּ, ʾĒlīyyāhū, meaning "My God is Yahweh/YHWH"; Greek form: Elias, ''Elías''; syr, ܐܸܠܝܼܵܐ, ''Elyāe''; Arabic: إلياس or إليا, ''Ilyās'' or ''Ilyā''. ) was, according to the Books of ...

, and styled himself as "Elijah the Restorer," "The Prophet Elijah", or "The Third Elijah." In his controversial relationship with Islam, Dowie prophesied the destruction of all Muslims around the world within a period of 25 years, upon the return of Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

. In 1903, when Ahmad heard Dowie's claims in India, particularly his prophecies concerning the Muslim world, he proposed a " Prayer Duel" and set out certain conditions. Ahmad requested Dowie to set aside his prophecies concerning the Muslims for the moment and offered his own life instead. He challenged Dowie to willingly pray for Ahmad's death instead, whilst simultaneously Ahmad prays for Dowie's destruction. The proposal was published in dozens of local and national newspapers across the United States and queried Dowie's response to the challenge. Dowie neither accepted the challenge, nor did he decline it. His followers claimed that he did not have time to respond, as he was busy preparing for his ''rally of rallies'' to New York City. However, in 1903, he responded to the challenge indirectly, stating in his periodical ''Leaves of Healing'':

Dowie died in 1907, roughly a year before Ahmad. In the years before his death, Dowie was deposed. The interplay between Ahmad and Dowie and the circumstances leading to the latter's death is seen by members of the Ahmadiyya movement as a sign of truthfulness of Ahmad as the Promised Messiah. Following Dowie's decline and his eventual death, multiple newspapers ran a discussion of Dowie's death in the context of Ahmad's prophecies. The Boston ''Sunday Herald'' ran a double page feature entitled "Great is Mirza Ghulam Ahmad The Messiah."

Arrival

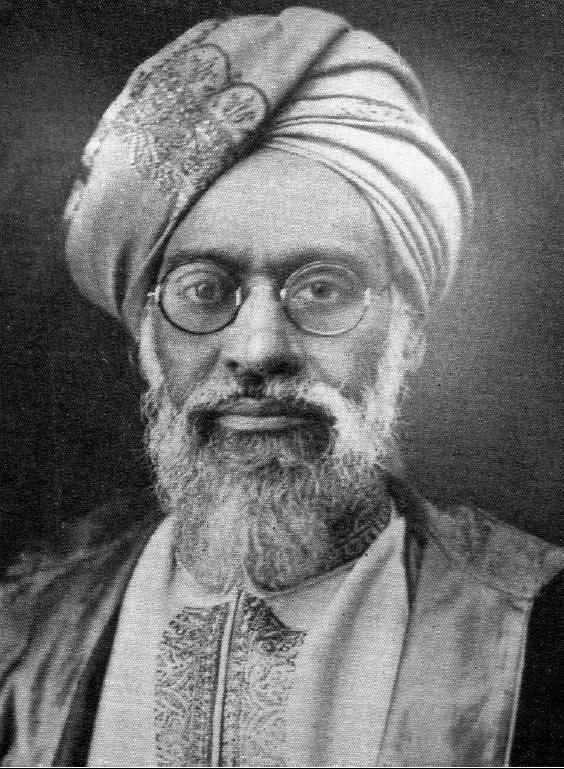

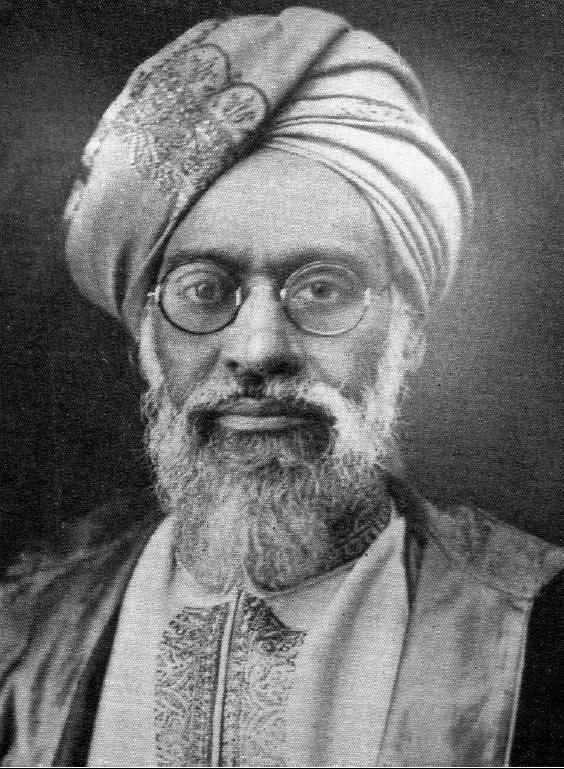

Despite the early onset of interactions with the American people, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community only began to prepare for its mission to the United States in 1911, during the era of the First Caliphate. However, it was not until almost a decade later, on January 24, 1920, during the era of the Second Caliphate, that Mufti Muhammad Sadiq, the first missionary to the country, would embark on

Despite the early onset of interactions with the American people, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community only began to prepare for its mission to the United States in 1911, during the era of the First Caliphate. However, it was not until almost a decade later, on January 24, 1920, during the era of the Second Caliphate, that Mufti Muhammad Sadiq, the first missionary to the country, would embark on SS Haverford

SS ''Haverford'' was an American transatlantic liner commissioned in 1901 for the American Line on the route from Southampton to New York, then quickly on the route from Liverpool to Boston and Philadelphia. During her early years, this ship, ma ...

from England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, for the United States. On board, Sadiq preached the Islamic faith on each day he spent on the translantic liner. With many passengers intrigued by Sadiq's teachings on the life of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 Common Era, CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Muhammad in Islam, Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet Divine inspiration, di ...

and the claims of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad

Mirzā Ghulām Ahmad (13 February 1835 – 26 May 1908) was an Indian religious leader and the founder of the Ahmadiyya movement in Islam. He claimed to have been divinely appointed as the promised Messiah and Mahdi—which is the metaphoric ...

as the return of the Messiah, seven people of Chinese, American, Syrian and Yugoslavian heritage converted to the Islamic faith. However, on the arrival of SS Haverford on the shores of Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, the authorities accused Sadiq of preaching a religion that permitted polygamous

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marriage, marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is ...

relationships. As an Ahmadi Muslim, Sadiq believed that the law of the land precedes the practice of non-essential Islamic principles. Despite this, and his assurance that he did not preach polygamy on board, the authorities refused his entry into the United States and demanded him to take a return trip back to Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

. Sadiq refused and submitted an appeal. Having successfully appealed against the decision, during the course of which he was temporarily detained and placed in a Philadelphia Detention House in Gloucester, New Jersey, for seven weeks, he continued his preaching efforts, but now limited to the inmates of the prison. Before his discharge, he managed to attract 19 people from Jamaican, Polish, Russian, German, Belgian, Portuguese, Italian, French heritage. Perhaps in a connection with his own ordeal with the authorities, Sadiq would later remark that under the U.S. immigration laws Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

would not be permitted entry into the United States.

Mirza Basheer-ud-Din Mahmood Ahmad

Mirza Basheer-ud-Din Mahmood Ahmad ( ur, ) (12 January 1889 – 8 November 1965), was the second caliph ( ar, خليفة المسيح الثاني, ''khalīfatul masīh al-thāni''), leader of the worldwide Ahmadiyya Muslim Community and the e ...

, the second caliph of the Community, with reference to the early missionary work in the western world, including that of Sadiq, later coined the term "Pioneers in the spiritual Colonization of the Western World," alluding to the Western colonization of the eastern hemisphere, the traditional East–west divide and their respective spiritual and secular identities. Several headlines remarked Mufti Muhammad Sadiq's arrival into the U.S, such as "Hopes to Convert U.S.", "East Indian Here With New Religion" and "Optimistic in Detention," alluding to Sadiq's continued missionary effort whilst taken custody on board. The Philadelphian ''Press'', recounting Sadiq's experience, states:

1920: New York City

In April 1920, Sadiq was permitted entry into the United States. Possibly attracted toNew York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

's reputed culture, he journeyed to the city and assembled the first national headquarters of the Ahmadiyya movement on Manhattan's Madison Avenue

Madison Avenue is a north-south avenue in the borough of Manhattan in New York City, United States, that carries northbound one-way traffic. It runs from Madison Square (at 23rd Street) to meet the southbound Harlem River Drive at 142nd Stre ...

. As a philologist

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defined as th ...

, with proficiency in Arabic and Hebrew linguistics, Sadiq successfully published articles on Islam in multiple American periodicals within a period of a few months, including in the ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

''. Moreover, as a lecturer and a charismatic public speaker, Sadiq secured approximately fifty lectures across several cities in the Northeast

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each se ...

, including Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at th ...

, Grand Havens in Michigan and his locale, New York City. As such, within a period of a few weeks, a dozen people of Christian and Muslim backgrounds converted to the Ahmadiyya interpretation of Islam. Among those were some of the earliest converts to Islam in the United States, who converted to Islam in the early 1900s, such as Ahmad Anderson and George Baker. Whilst a missionary in England, before his arrival into the United States, Sadiq had a dream concerning a female American convert to the faith. The moment S. W. Sobolewski walked into the Community's headquarters on Madison Avenue, Sadiq interpreted her to be the fulfilment of his dream. Sobolewski would later join the movement, and be given the name Fatimah Mustafa. She became renowned as the first white American female to convert to Islam. Nonetheless, the most active female preacher of the movement during the 1920s was an African American, Madame Rahatullah.

1920–1950: Chicago–Detroit

In October 1920, within a period of a few months of Sadiq's arrival to New York City, Sadiq moved the headquarters to

In October 1920, within a period of a few months of Sadiq's arrival to New York City, Sadiq moved the headquarters to Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, Illinois. Accompanying this was the shift of America's Ahmadiyya Muslim Community towards the problem of racial separatism, with particular focus on discrimination of black Americans. Perhaps triggered by segregation of African American Muslims and Arab Muslims who arrived in Illinois as labourers during the early 20th century, the Ahmadis made various attempts to unite and reconcile Muslims of different racial backgrounds and ethnicities. During the winter of 1920, Sadiq was elected president of an intra-Muslim society, aiming to combat separatism and promote multi-racial unity among Muslims across the United States. Mohni, a non-Ahmadi Muslim and editor of the ''alserat,'' an Arabic newspaper was elected secretary. Shortly after, within the same year, Sadiq moved the national headquarters of the Community to Highland Park, in Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at th ...

, Michigan. The city attracted Muslim workers of diverse ethnic backgrounds. The move came in an attempt to link various Muslim communities across the region.

In 1922, Sadiq once again returned to Chicago and re-established the national headquarters of the movement at 4448 Wabash Avenue. A converted house was used to serve as a mosque and a mission house. The mission house was from where the oldest Islamic magazine ''The Moslem Sunrise'' was to be published from. Whilst based in Chicago, Sadiq continued to deliver his public lectures on Islam at schools, clubs and lodges across the Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four Census Bureau Region, census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of ...

. Many a times he was successful in removing misconceptions concerning the religion and occasionally his speeches attracted converts. In 1923, Sadiq gave multiple lectures at the Universal Negro Improvement Association

The Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL) is a black nationalist fraternal organization founded by Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican immigrant to the United States, and Amy Ashwood Garvey. The Pan-African o ...

, as a result of which he converted 40 members of the fraternal organization to Islam. In September 1923, Sadiq left the United States for India. He was replaced by Muhammad Din, another missionary to the Community. During his three years, Sadiq had converted 700 Americans to Islam. Named in honour of Mufti Muhammad Sadiq, Wabash Avenue is today the site of the Al-Sadiq Mosque

The Al Sadiq Mosque (or Wabash Mosque) was commissioned in 1922 in the Bronzeville neighborhood in city of Chicago. The Al-Sadiq Mosque is one of America's earliest built mosques and the oldest standing mosque in the country today. This mosque ...

, the oldest standing mosque in the United States.

In contrast to the early converts to the movement who generally belonged to diverse ethnic backgrounds, the converts during Sadiq's Chicago-era were largely African American, with relatively less white American. The cities of Chicago and Detroit, and to some degree, St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

, Missouri, and Gary, Indiana, were major centres of Ahmadiyya missionary activity during the 1920s. Muhammad Yaqoob, formerly Andrew Jacob; Ghulam Rasul, formerly Mrs. Elias Russel and James Sodick, a Russian Tartar, were some of the key figures of the Ahmadiyya activity. Some African American converts emerged as prominent missionaries of the Community. For example, Ahmad Din, who formerly may have been a Freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

or a member of the Moorish Science Temple

The Moorish Science Temple of America is an American national and religious organization founded by Noble Drew Ali (born as Timothy Drew) in the early twentieth century. He based it on the premise that African Americans are descendants of the M ...

, was appointed as a missionary in St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

, Missouri. Din is said to have acquired roughly 100 converts in the city. J. H. Humpharies, one of Din's converts, became an active missionary of the Ahmadiyya Community himself, after becoming disillusioned with Christianity. Humpharies was a Belgian-Congolese immigrant who studied at the Tuskegee Institute

Tuskegee University (Tuskegee or TU), formerly known as the Tuskegee Institute, is a private, historically black land-grant university in Tuskegee, Alabama. It was founded on Independence Day in 1881 by the state legislature.

The campus was de ...

for the evangelical Protestant ministry

Ministry may refer to:

Government

* Ministry (collective executive), the complete body of government ministers under the leadership of a prime minister

* Ministry (government department), a department of a government

Religion

* Christian ...

.

In the late 1920s, Sufi Bengalee arrived in the United States and replaced Muhammad Din as a missionary. Bengalee resumed Sadiq's tradition of giving lectures throughout the country. The lectures varied from talks on the life of the Islamic prophet

In the late 1920s, Sufi Bengalee arrived in the United States and replaced Muhammad Din as a missionary. Bengalee resumed Sadiq's tradition of giving lectures throughout the country. The lectures varied from talks on the life of the Islamic prophet Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 Common Era, CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Muhammad in Islam, Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet Divine inspiration, di ...

to the question of overcoming racial prejudice in the United States. Within a few years of his arrival, he gave over seventy lectures, some of which were facilitated by the multi-racial ecumenical Christian organization, ''Fellowship of Faiths''. Venues that were sponsored by the organization included the Chicago Temple, the First Congregational Church, the People's Church and the Sinai Temple Men's Club. Many of these lectures catered for large number of audiences, up to and including 2500 people. Other settings for talks included institutions of higher education, such as Northwestern University

Northwestern University is a private research university in Evanston, Illinois. Founded in 1851, Northwestern is the oldest chartered university in Illinois and is ranked among the most prestigious academic institutions in the world.

Charte ...

and the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

. Many talks were featured in newspapers, such as the ''Chicago Daily Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is a daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States, owned by Tribune Publishing. Founded in 1847, and formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" (a slogan for which WGN radio and television are ...

'' and the ''Chicago Daily News

The ''Chicago Daily News'' was an afternoon daily newspaper in the midwestern United States, published between 1875 and 1978 in Chicago, Illinois.

History

The ''Daily News'' was founded by Melville E. Stone, Percy Meggy, and William Dougherty ...

.'' Although in contrast to Sadiq's era, the Ahmadiyya Community toned down its multi-racial rhetoric, perhaps in response to FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and its principal Federal law enforcement in the United States, federal law enforcement age ...

's campaign to divide American Muslim groups in suspicion of potential sedition, it continued to address the issue of racism. At a lecture at the People's Church discussing racism, Bengalee stated:

In August and September 1932, the Ahmadiyya movement participated in the World Fellowship of Faiths Convention. Opened with a message from the caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

and world head of the Ahmadiyya movement, Mirza Basheer-ud-Din Mahmood Ahmad

Mirza Basheer-ud-Din Mahmood Ahmad ( ur, ) (12 January 1889 – 8 November 1965), was the second caliph ( ar, خليفة المسيح الثاني, ''khalīfatul masīh al-thāni''), leader of the worldwide Ahmadiyya Muslim Community and the e ...

, the convention exhibited a speech on "Islam, Promoting World Peace and Progress," delivered by Muhammad Zafarullah Khan

Chaudhry Sir Muhammad Zafarullah Khan ( ur, ; 6 February 1893 – 1 September 1985) was a Pakistani jurist and diplomat who served as the first Foreign Minister of Pakistan. After serving as foreign minister he continued his international ...

, an Ahmadi Muslim and a former president of All-India Muslim League

The All-India Muslim League (AIML) was a political party established in Dhaka in 1906 when a group of prominent Muslim politicians met the Viceroy of British India, Lord Minto, with the goal of securing Muslim interests on the Indian subcontin ...

. In one conference held on September 1, 1935, Bengalee attempted to give a practical example of favourable race relation among his converts. He introduced a white convert, Muhammad Ahmad, and a black convert, Omar Khan. The two discussed Islamic qualities concerning race relations. Perhaps, the most conspicuous was a conference at the Chicago Temple Building, attended by speakers of various religious and racial backgrounds. The conference which was entitled, "How Can We Overcome Color and Race Prejudice?" was attended by over 2000 people. By the 1940s, the Ahmadiyya movement had between 5000 and 10,000 members in the United States, a small speck in sight of the growing 2 million members worldwide. In light of this and a number of political and cultural concerns and rising tensions in the Muslim world, the African American identity and its local issues were occasionally obscured. Moreover, during the 1940s, the Ahmadiyya movement began to shift away from its focus on the African Americans, and again towards the general public.

During the 1940s, the cities of Chicago, Washington, D.C., Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

, Pennsylvania, Kansas City

The Kansas City metropolitan area is a bi-state metropolitan area anchored by Kansas City, Missouri. Its 14 counties straddle the border between the U.S. states of Missouri (9 counties) and Kansas (5 counties). With and a population of more ...

, Missouri, and Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

, Ohio, were major centres of the Ahmadiyya missionary activity. Yusef Khan, a prominent Ahmadi teacher from Pittsburgh, was responsible for the education of a splinter group of the Moorish Science Temple. Omar Cleveland and Wali Akram, both African American Ahmadi Muslim in Cleveland, Ohio, were key figures during this period. Cleveland published multiple articles on ''The Moslem Sunrise''. As a consequence of Akram's work, there were perhaps 200 converts in the city, the majority of which were African American. In the city, there were frequent inter-ethnic and inter-religious marriages among the Ahmadi Muslims.

''The Moslem Sunrise''

In the summer of 1921, Sadiq founded the first Islamic magazine in the United States, ''The Moslem Sunrise'' and published it quarterly, with its first issue being released on July 21, 1921. The cover of each issue displayed a sunrise over the North American continent, perhaps insinuating the rise of the Islam in the United States and a prophetic symbolism of asaying

A saying is any concisely written or spoken expression that is especially memorable because of its meaning or style. Sayings are categorized as follows:

* Aphorism: a general, observational truth; "a pithy expression of wisdom or truth".

** Adage ...

of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 Common Era, CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Muhammad in Islam, Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet Divine inspiration, di ...

, which stated "In the Latter Days, the sun shall rise from the West." In just the first quarter, 646 requests were received and roughly 2,000 packages were sent. Approximately 500 copies of the publication were sent to Masonic lodges

A Masonic lodge, often termed a private lodge or constituent lodge, is the basic organisational unit of Freemasonry. It is also commonly used as a term for a building in which such a unit meets. Every new lodge must be warranted or chartered ...

and 1,000 copies of Ahmadiyya literature, including copies of the publication, were mailed to libraries across the country. The recipients included several contemporary celebrities such as Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that mi ...

, Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventio ...

and the then President of the United States, Warren Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party, he was one of the most popular sitting U.S. presidents. ...

.

As a consequence of colonization of Muslim lands, and thus the rising contact with the Muslim world, Islam was becoming an increasing victim of criticism from the American media. Sadiq, and the American Ahmadiyya Muslim Community utilized ''The Moslem Sunrise'' as a tool to defend Islam and the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Classical Arabic, Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation in Islam, revelation from God in Islam, ...

against Christian polemics. Recognizing racial intolerance in the early 20th century America, Sadiq also popularized the Islamic quality for inter-racial harmony. The publication had a profound influence on African American-Islam relations, including the early development of the Nation of Islam

The Nation of Islam (NOI) is a religious and political organization founded in the United States by Wallace Fard Muhammad in 1930.

A black nationalist organization, the NOI focuses its attention on the African diaspora, especially on African ...

and the Moorish Science Temple

The Moorish Science Temple of America is an American national and religious organization founded by Noble Drew Ali (born as Timothy Drew) in the early twentieth century. He based it on the premise that African Americans are descendants of the M ...

. On the other hand, the publication strained Sadiq's relationship with mainstream American Protestant Christianity and the American media. Whilst discussing the Detroit race riot of 1943, the magazine would describe the situation as a "dark blot in the country's good name." Roughly five years later, in 1948, the magazine documented 13,600 churches belonging to Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

, Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

and Unitarian Christian denominations and concluded that only 1,331 had "colored

''Colored'' (or ''coloured'') is a racial descriptor historically used in the United States during the Jim Crow, Jim Crow Era to refer to an African Americans, African American. In many places, it may be considered a Pejorative, slur, though it ...

members." When Sadiq arrived in the country, he envisioned a multi-racial movement and inter-religious harmony with the dominant Protestant communities in America. However, many white Protestants of that period, with whom Sadiq came into contact with, as Sadiq later realized, were unwilling to work towards the Ahmadi Muslim ideal of an American society. Consequently, the American Ahmadi missionary activity shifted more towards the African American populations.

1950–1994: Washington, D.C.

black nationalism

Black nationalism is a type of racial nationalism or pan-nationalism which espouses the belief that black people are a race, and which seeks to develop and maintain a black racial and national identity. Black nationalist activism revolves ar ...

among African Americans, as opposed to Ahmadi ideal of multi-racial global identity has been cited as one possible reason. After the 1950s, the Nation of Islam, which generally caters for black Americans, began to draw more followers than the Ahmadiyya movement. On the other hand, with the rise of Muslim immigration from the Arab world

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western A ...

, African Americans may have desired to " arabize" their Islamic identity, which contrasts to the South Asian

South Asia is the southern Subregion#Asia, subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geography, geographical and culture, ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, ...

heritage of early Ahmadi missionaries in the country. Subsequently, since the 1970s, Sunni

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagr ...

Muslims began to draw large converts from the African American community as well. However, push factors that may have also contributed to the slow development of the Community include clash of cultures between African Americans and the growing immigrant Ahmadi communities of Pakistani heritage. It has been argued that the missionaries may have bought effects of colonialism with them and insisted on Indian cultural norms on the one hand, and denied African American culture on the other. In the decades of the 1970s and 1980s, the Ahmadiyya Community continued to attract small, though significant number of converts from among the African American populations. In spite of the rise of Muslim immigrant populations from the Middle East, the Community continued to be an exemplary multi-racial model in the changing dynamics of American Islam, which was often wrought with challenges of diversity, and conjectures of racial superiority. It has been argued that it had the potential for partial acculturation

Acculturation is a process of social, psychological, and cultural change that stems from the balancing of two cultures while adapting to the prevailing culture of the society. Acculturation is a process in which an individual adopts, acquires and ...

along class lines.

Journeys by caliphs

Caliph IV

In the 1980s,

In the 1980s, Mirza Tahir Ahmad

Mirza Tahir Ahmad ( ur, ) (18 December 1928 – 19 April 2003) was the Ahmadiyya Caliphate, fourth caliph ( ar, خليفة المسيح الرابع, ''khalīfatul masīh al-rābi'') and the head of the worldwide Ahmadiyya, Ahmadiyya Communi ...

, the fourth caliph and worldwide head of the movement sanctioned five large mosque projects, to be built in and around major cities in the United States, including Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

, Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, Houston

Houston (; ) is the most populous city in Texas, the most populous city in the Southern United States, the fourth-most populous city in the United States, and the sixth-most populous city in North America, with a population of 2,304,580 in ...

and Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

In 1987, the caliph toured the United States and laid foundation stones for multiple mosques across the country. For example, on October 23, 1987, he laid the foundation stone for the Baitul Hameed Mosque

The Baitul Hameed Mosque (English: ''House of the Praiseworthy'') is the largest Ahmadiyya Muslim mosque in the Western United States with an area of sitting on nearly . Initially built in 1989 at a cost of $2.5 million, entirely from donations o ...

in Chino, California with a brick specially bought from Qadian

Qadian (; ; ) is a city and a municipal council in Gurdaspur district, north-east of Amritsar, situated north-east of Batala city in the state of Punjab, India.

Qadian is the birthplace of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the founder of the Ahmadiyya move ...

, India, the birthplace of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad. The mosque was inaugurated by the caliph on his second trip in 1989.

Caliph V

Mirza Masroor Ahmad

Mirza Masroor Ahmad ( ur, ; born 15 September 1950) is the current and fifth leader of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. His official title within the movement is Fifth Caliph of the Messiah ( ar, خليفة المسيح الخامس, ''khal� ...

, the current and fifth caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community attended the Annual Convention of the United States in June 2012. As part of his visit, on 27 June 2012, he also delivered a keynote address at a bi-partisan reception co-sponsored by the Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission

The Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission (formerly known as the Congressional Human Rights Caucus) is a bipartisan caucus of the United States House of Representatives. Its stated mission is "to promote, defend and advocate internationally recogniz ...

and the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom

The United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) is a U.S. federal government commission created by the International Religious Freedom Act (IRFA) of 1998. USCIRF Commissioners are appointed by the President and the lead ...

at the Rayburn House Office Building in Capitol Hill

Capitol Hill, in addition to being a metonym for the United States Congress, is the largest historic residential neighborhood in Washington, D.C., stretching easterly in front of the United States Capitol along wide avenues. It is one of the ...

, Washington, D.C., entitled "The Path to Peace: Just Relations Between Nations." The reception featured remarks by House Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi

Nancy Patricia Pelosi (; ; born March 26, 1940) is an American politician who has served as Speaker of the United States House of Representatives since 2019 and previously from 2007 to 2011. She has represented in the United States House of ...

, U.S. Senator Robert Casey, U.S. Members of Congress Brad Sherman

Bradley James Sherman (born October 24, 1954) is an American accountant and politician serving as the U.S. representative for California's 30th congressional district since 2013. A member of the Democratic Party, he first entered Congress in 19 ...

, Frank Wolf, Mike Honda

Michael Makoto "Mike" Honda (born June 27, 1941) is an American politician and former educator. A member of the Democratic Party, he served in Congress from 2001 to 2017.

Initially involved in education in California, he first became active in ...

, Keith Ellison

Keith Maurice Ellison (born August 4, 1963) is an American politician and lawyer serving as the 30th attorney general of Minnesota. A member of the Democratic–Farmer–Labor Party (DFL), Ellison was the U.S. representative for from 2007 to ...

, Zoe Lofgren

Susan Ellen "Zoe" Lofgren ( ; born December 21, 1947) is an American lawyer and politician serving as a U.S. representative from California. A member of the Democratic Party, Lofgren is in her 13th term in Congress, having been first elected in 1 ...

, and U.S. Chairwoman for the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom Katrina Lantos Swett. Lofgren also presented Ahmad with a copy of a bipartisan U.S. House of Representative resolution (H. Res 709) welcoming him to Washington D.C. and honoring his contributions to peace. In total, more than 130 dignitaries, including 30 members of U.S. Congress, members of the diplomatic corps, members of uniform services, NGO leaders, professors, thought leaders and inter-faith and community leaders attended the event.

On his first trip to the West Coast of the United States on 11 May 2013, Mirza Masroor Ahmad delivered a keynote address entitled, "Islamic Solution to Achieve World Peace," at a "Global Peace Lunch" at the Montage Hotel in Beverly Hills, CA. Over 300 dignitaries participated in the event. Special guests included: California Lieutenant Governor Gavin Newsom

Gavin Christopher Newsom (born October 10, 1967) is an American politician and businessman who has been the 40th governor of California since 2019. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as the 49th lieutenant governor of California fr ...

, California State Controller John Chiang, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti

Eric Michael Garcetti (born February 4, 1971) is an American politician who served as the 42nd mayor of Los Angeles from 2013 until 2022. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he was first elected in the 2013 Los An ...

, Los Angeles County Sheriff Lee Baca

Leroy David Baca (born May 27, 1942) is a convicted criminal and former American law enforcement officer who served as the 30th Sheriff of Los Angeles County, California from 1998 to 2014. In 2017, he was convicted of felony obstruction of justi ...

, former California Governior Gray Davis

Joseph Graham "Gray" Davis Jr. (born December 26, 1942) is an American attorney and former politician who served as the 37th governor of California from 1999 to 2003. In 2003, only a few months into his second term, Davis was recalled and remov ...

, U.S. Congresswoman Karen Bass

Karen Ruth Bass (; born October 3, 1953) is an American politician, social worker and former physician assistant who is serving as the 43rd mayor of Los Angeles since 2022. A member of the Democratic Party, Bass had previously served in the U.S. ...

, U.S. Congresswoman Gloria Negrete McLeod

Gloria Negrete McLeod (born September 6, 1941) is an American politician who was the United States representative for from 2013 to 2015. The district included portions of eastern Los Angeles County and western San Bernardino County. She was a ...

, U.S. Congresswoman Judy Chu

Judy May Chu (born July 7, 1953) is an American politician serving as the U.S. representative for since 2013. A member of the Democratic Party, she has held a seat in Congress since 2009, representing until redistricting. Chu is the first Chines ...

, U.S. Congresswoman Julia Brownley

Julia Andrews Brownley (born August 28, 1952) is an American businesswoman and politician who has been the United States representative for California's 26th congressional district since 2013. A Democrat, she served in the California State Assem ...

and U.S. Congressman Dana Rohrabacher

Dana Tyrone Rohrabacher (; born June 21, 1947) is a former American politician who served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1989 to 2019. A Republican, he represented for the last three terms of his House tenure.

Rohrabacher ran for re- ...

. Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti

Eric Michael Garcetti (born February 4, 1971) is an American politician who served as the 42nd mayor of Los Angeles from 2013 until 2022. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he was first elected in the 2013 Los An ...

and Los Angeles City Councilman Dennis Zine

Dennis Phillip Zine (born August 1, 1947) is an American politician, who served on the Los Angeles City Council for the 3rd district from 2001 to 2013. A member of the Republican Party who later became unaffiliated in 2011, Zine was elected t ...

presented Ahmad with a special golden key to the city.

Influence

American Islam

The U.S. Ahmadiyya Muslim Community under the leadership of Mufti Muhammad Sadiq provided the first multi-racial community experience for the African American Muslims. Until the 1960s, most of the Islamic literature would be published by the Ahmadiyya movement. The Community published the first Islamic magazine and the first Quran translation in the United States. According to Turner, the Ahmadiyya movement was "arguably the most influential community in African-American Islam until the 1950s." Although at first Ahmadiyya efforts were broadly concentrated at over large number of racial and ethnic groups, subsequent realization of the deep-seated racial tensions and discrimination made Ahmadi Muslim missionaries focus their attention to mainly African Americans and the Muslim immigrant community and became vocal proponents of the Civil Rights Movement. The Ahmadi Muslims offered the first multi-racial community experience for African American Muslims, which included elements of Indian culture andPan-Africanism

Pan-Africanism is a worldwide movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all Indigenous and diaspora peoples of African ancestry. Based on a common goal dating back to the Atlantic slave trade, the movement exte ...

.

Over the late 20th century, the Ahmadiyya influence on African American Islam subsided to a degree. The Community did not draw as many followers as it did in its early history. However, Ahmadi Muslims continued to be an influential force, educating numerous African Americans that passed through its ranks. Often working behind the scenes, the Community had a profound influence in the African American-Isam relations including the early development of the Nation of Islam, the Moorish Science Temple and American Sunni Islam

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagre ...

. In particular, the Community is said to have influenced Elijah Muhammad

Elijah Muhammad (born Elijah Robert Poole; October 7, 1897 – February 25, 1975) was an African American religious leader, black separatist, and self-proclaimed Messenger of Allah, who led the Nation of Islam (NOI) from 1934 until his de ...

, the leader of the Nation of Islam, and his son, Warith Deen Mohammed

Warith Deen Mohammed (born Wallace D. Muhammad; October 30, 1933 – September 9, 2008), also known as W. Deen Mohammed, Imam W. Deen Muhammad and Imam Warith Deen, was an African-American Muslim leader, theologian, philosopher, Muslim revi ...

, who became a Sunni Muslim.

While Malcolm X

Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little, later Malik el-Shabazz; May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965) was an American Muslim minister and human rights activist who was a prominent figure during the civil rights movement. A spokesman for the Nation of Is ...

was in Norfolk Prison Colony, he was visited by an Ahmadi missionary, Abdul Hameed; pseudo-named as Omar Khalil in literature. Hameed later sent him a book of Islamic prayers in Arabic which Malcolm did memorize phonetically. Whilst a member of Nation of Islam

The Nation of Islam (NOI) is a religious and political organization founded in the United States by Wallace Fard Muhammad in 1930.

A black nationalist organization, the NOI focuses its attention on the African diaspora, especially on African ...

in prison, he was impressed by the Ahmadi teachings. After his release in 1952, Malcolm repeatedly attempted to incorporate the Nation of Islam into a more traditional form of Islam. It has been suggested that this may have been the reason why he once identified himself as an "Asiatic." He later stated that "Allah

Allah (; ar, الله, translit=Allāh, ) is the common Arabic word for God. In the English language, the word generally refers to God in Islam. The word is thought to be derived by contraction from '' al- ilāh'', which means "the god", an ...

is One God, not of one particular people or race, but of All the Worlds, thus forming All Peoples into One Universal Brotherhood." He would repeat the notion of a universal and multi-racial faith, which according to Louis DeCaro can genealogically be seen descending from the influence of the Ahmadiyya movement.

Jazz

The Ahmadiyya movement was the main channel through which many African American musicians were introduced to Islam during the mid-20th century. It was contended that converting to a Muslim faith provided spiritual protection from harmful pitfalls that accompanied the profession, alongside a safeguard from the stigma of white supremacy. Islam was a force which impeded the deterioration of the mind and body through physical and spiritual deterrents. For example, by teaching the importance of keeping the body as well as the spirit clean, it offered an opportunity to clear the musicians from the labyrinth of American oppression and the myths about black Americans. Some Ahmadi converts includedAhmad Jamal

Ahmad Jamal (born Frederick Russell Jones, July 2, 1930) is an American jazz pianist, composer, bandleader and educator. For six decades, he has been one of the most successful small-group leaders in jazz.

Biography Early life

Jamal was born Fr ...

, a pianist from Chicago; Dakota Staton

Dakota Staton (June 3, 1930 – April 10, 2007) was an American jazz vocalist who found international acclaim with the 1957 No. 4 hit "The Late, Late Show". She was also known by the Muslim name Aliyah Rabia for a period due to her conversion to ...

, a vocalist and her husband, Talib Dawud

Talib Ahmad Dawood (formerly Alfonso Nelson Rainey, born January 26, 1923, on Antigua; died 9 July 1999, New York City) was an American jazz trumpeter.

Career

Dawud came from Antigua and Barbuda, taking lessons from his father, a trumpeter who ...

, a trumpeter, both from Philadelphia; and Yusef Lateef

Yusef Abdul Lateef (born William Emanuel Huddleston; October 9, 1920 – December 23, 2013) was an American jazz multi-instrumentalist, composer, and prominent figure among the Ahmadiyya Community in America.

Although Lateef's main instruments ...

, a Grammy Award-winning saxophonist from New York City, who became the spokesperson for the U.S. Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. Other members of the Community included the drummer Art Blakey

Arthur Blakey (October 11, 1919 – October 16, 1990) was an American jazz drummer and bandleader. He was also known as Abdullah Ibn Buhaina after he converted to Islam for a short time in the late 1940s.

Blakey made a name for himself in the 1 ...

, the double bassist Ahmed Abdul-Malik

Ahmed Abdul-Malik (born Jonathan Tim, Jr.; January 30, 1927 – October 2, 1993) was an American jazz double bassist and oud player.

Abdul-Malik is remembered for integrating Middle Eastern and North African music styles in his jazz music.Kelsey ...

, the reed player Rudy Powell, the saxophonist Sahib Shihab

Sahib Shihab (born Edmund Gregory; June 23, 1925 – October 24, 1989) was an American jazz and hard bop saxophonist (baritone, alto, and soprano) and flautist. He variously worked with Luther Henderson, Thelonious Monk, Fletcher Henderson, Tad ...

, the pianist McCoy Tyner

Alfred McCoy Tyner (December 11, 1938March 6, 2020) was an American jazz piano, jazz pianist and composer known for his work with the John Coltrane Quartet (from 1960 to 1965) and his long solo career afterwards. He was an NEA Jazz Masters, NEA ...

, and the trumpeter Idrees Sulieman

Idrees Sulieman (August 7, 1923 – July 23, 2002) was an American bop and hard bop trumpeter.

Biography

He was born Leonard Graham in St. Petersburg, Florida, United States, later changing his name to Idrees Sulieman, after converting to Isl ...

. Blakey was introduced to Ahmadiyya through Dawud, and the two started a Quran study group as well a rehearsal band from Blakey's apartment in Philadelphia. The latter evolved into an influential Jazz combo, The Jazz Messengers

The Jazz Messengers were a jazz combo that existed for over thirty-five years beginning in the early 1950s as a collective, and ending when long-time leader and founding drummer Art Blakey died in 1990. Blakey led or co-led the group from the o ...

, led by the drummer, Art Blakey. The term " messengers" in Islam refers to a group of people assigned to special missions by God to guide humankind. In Ahmadiyya in particular, the term amalgamated with "Jazz" embodied a form of an American symbolism of the democratic promise of Islam's universalism. Initially an all Muslim group, the group attracted a large number of jazz musicians.

The Muslim faith began to grow among musicians when some of the early Ahmadi musicians began to raise money in order to bring and support Ahmadiyya missionaries from the Indian subcontinent. Articles on Ahmadi musicians would be published across popular publications. In 1953, ''Ebony

Ebony is a dense black/brown hardwood, coming from several species in the genus ''Diospyros'', which also contains the persimmons. Unlike most woods, ebony is dense enough to sink in water. It is finely textured and has a mirror finish when pol ...

'' published articles, such as "Moslem Musicians" and "Ancient religion attracts Moderns," although the magazine attempted to downplay the influence of Islam. Despite the fact that the role of music in Islam was a subject of debate among the South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;;;;; ...

n Ahmadis, the musicians, whilst donning Islamic attire, combined Islamic themes and their struggle for civil rights in their recordings. At times sounds from the Middle East and Asia would be assimilated into the songs. This would give rise to song titles such as ''Abdullah's Delight,'' ''Prayer to the East'' and ''Eastern Clouds.'' Although Dizzy Gillespie

John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie (; October 21, 1917 – January 6, 1993) was an American jazz trumpeter, bandleader, composer, educator and singer. He was a trumpet virtuoso and improviser, building on the virtuosic style of Roy Eldridge but addi ...

, Miles Davis

Miles Dewey Davis III (May 26, 1926September 28, 1991) was an American trumpeter, bandleader, and composer. He is among the most influential and acclaimed figures in the history of jazz and 20th-century music. Davis adopted a variety of music ...

, and John Coltrane

John William Coltrane (September 23, 1926 – July 17, 1967) was an American jazz saxophonist

The saxophone (often referred to colloquially as the sax) is a type of single-reed woodwind instrument with a conical body, usually made of br ...

did not become Ahmadi Muslims, they were influenced by the spirit of Islam bought by the Ahmadis. ''A Love Supreme

''A Love Supreme'' is an album by American jazz saxophonist John Coltrane. He recorded it in one session on December 9, 1964, at Van Gelder Studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, leading a quartet featuring pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Ga ...

'', one of Coltrane's greatest pieces of work, considered by some as the greatest Jazz album of all time, was deeply influenced by the work of the Ahmadiyya movement. In the liner notes of the album, Coltrane repeatedly echoes ''Basmala

The ''Basmala'' ( ar, بَسْمَلَة, ; also known by its incipit ; , "In the name of Allah"), or Tasmiyyah (Arabic: ), is the titular name of the Islamic phrase "In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful" (Arabic: , ). ...

'', the opening verse of almost every chapter of the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Classical Arabic, Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation in Islam, revelation from God in Islam, ...

: "Now and again through the unerring hand of God, I do perceive his ... Omnipotence ... He is Gracious and Merciful."

Demographics

Between 1921 and 1925, there were 1,025 converts to the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, many of whom were African American from Chicago and Detroit. By the 1940s, the Ahmadiyya movement had between 5000 and 10,000 members in the United States. By the 1980s, there were roughly 10,000 Ahmadi Muslims in the country, of whom 60% were African-Americans. The remainder consisted of immigrant populations from Pakistan, India and the African continent. Today, there are roughly 15,000 to 20,000 Ahmadi Muslims across the country. Although Ahmadi Muslims have a presence across several U.S. states, sizeable communities exist in New York City, Chicago, Detroit,Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

, Washington, D.C., Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, and in Dayton

Dayton () is the sixth-largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Montgomery County. A small part of the city extends into Greene County. The 2020 U.S. census estimate put the city population at 137,644, while Greater Da ...

, Ohio.

Muslims for Life blood drives

Since the tenth anniversary of9/11

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commercial ...

, members of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community have been holding an annual blood drive in remembrance of those who lost their lives in the attacks. Whilst working with ''Muslims for Life'', a U.S. Ahmadiyya charitable initiative, and the American Red Cross

The American Red Cross (ARC), also known as the American National Red Cross, is a non-profit humanitarian organization that provides emergency assistance, disaster relief, and disaster preparedness education in the United States. It is the desi ...

, the Community in its first year of its collection, collected 11,000 pints of blood. The initiative comes in an effort to bring together different people, amid the rising tensions in the post 9/11 era. It also comes in an attempt to honor the victims of the attack.

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Official website of the U.S. Ahmadiyya Muslim Community

{{Demographics of the United States

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

Islam in the United States