Agnes B. Marshall on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Agnes Bertha Marshall (; 24 August 1855 – 29 July 1905) was an English

Marshall was a formidable businesswoman even by modern standards. In January 1883, Marshall and her husband bought the National Training School of Cookery, located at 31 Mortimer Street in London, and renamed it to the Marshall's School of Cookery. The school was purchased from Felix and Mary Ann Lavenue, who ran a cookery school of their own at 57 Mortimer Street. The original records of the transaction have not survived but later evidence suggests that Marshall bought the school with her own money. That the couple purchased the school together and that it was clear that Marshall herself was the main owner and driving force was unusual, since women had only very recently earned the legal right to purchase property through the Married Women's Property Act 1882. Marshall's step-brother John was employed as the school's manager.

The Marshall's School of Cookery mainly taught a mixture of high-end English and French cuisine and swiftly became one of only two major cookery schools in the city, alongside the

Marshall was a formidable businesswoman even by modern standards. In January 1883, Marshall and her husband bought the National Training School of Cookery, located at 31 Mortimer Street in London, and renamed it to the Marshall's School of Cookery. The school was purchased from Felix and Mary Ann Lavenue, who ran a cookery school of their own at 57 Mortimer Street. The original records of the transaction have not survived but later evidence suggests that Marshall bought the school with her own money. That the couple purchased the school together and that it was clear that Marshall herself was the main owner and driving force was unusual, since women had only very recently earned the legal right to purchase property through the Married Women's Property Act 1882. Marshall's step-brother John was employed as the school's manager.

The Marshall's School of Cookery mainly taught a mixture of high-end English and French cuisine and swiftly became one of only two major cookery schools in the city, alongside the

From 1886 onwards, Marshall and her husband published the magazine ''The Table'', a weekly paper on "Cookery, Gastronomy ndfood amusements". Every issue of ''The Table'' was accompanied by a weekly recipe contributed by Marshall and for the first six month (and periodically thereafter) the magazine also included weekly articles written by Marshall on an assortment of subjects she took an interest in. According to the historian John Deith, these articles were written in a "chatty, witty and ironic,

From 1886 onwards, Marshall and her husband published the magazine ''The Table'', a weekly paper on "Cookery, Gastronomy ndfood amusements". Every issue of ''The Table'' was accompanied by a weekly recipe contributed by Marshall and for the first six month (and periodically thereafter) the magazine also included weekly articles written by Marshall on an assortment of subjects she took an interest in. According to the historian John Deith, these articles were written in a "chatty, witty and ironic,

In 1904, Marshall fell from a horse and suffered wounds that she never properly recovered from. She died the next year, in the early morning of 29 July 1905 at ''The Towers'', Pinner. ''The Towers'' was a large estate purchased and refurbished by Marshall in 1891. Marshall was cremated at the Golders Green Crematorium and her ashes were interred at the Paines Lane Cemetery in Pinner. Alfred remarried within a year of her death to Gertrude Walsh, a former secretary that Marshall had previously fired. The two had likely been engaged in an affair before Marshall's death. Their son Alfred died in 1907 and his ashes were interred next to Marshall's. The elder Alfred died in 1917 in Nice during World War I; his ashes was at his request also interred next to Marshall's in 1920.

Marshall was one of the most celebrated cooks of her time and one of the foremost cookery writers of the Victorian age, particularly on ice cream. Her recipes were renowned for their detail, simplicity and accuracy. For her work on ice cream and other frozen desserts, Marshall in her lifetime earned the nickname "Queen of Ices". Only a single book on ice cream is known from England before Marshall's work and she helped popularise ice cream at a time when the concept was still novel in England and elsewhere, particularly through the portable ice cream freezer and the ice cream cone. Before Marshall's writings and innovations, ice cream was often sold frozen to metal rods which had to be returned after all had been licked off and was mainly enjoyed by just the upper classes. She increased the popularity of ice cream to such an extent that she was credited for causing an increase in ice imports from Norway. In 1901, she became the first person known to have suggested the use of

In 1904, Marshall fell from a horse and suffered wounds that she never properly recovered from. She died the next year, in the early morning of 29 July 1905 at ''The Towers'', Pinner. ''The Towers'' was a large estate purchased and refurbished by Marshall in 1891. Marshall was cremated at the Golders Green Crematorium and her ashes were interred at the Paines Lane Cemetery in Pinner. Alfred remarried within a year of her death to Gertrude Walsh, a former secretary that Marshall had previously fired. The two had likely been engaged in an affair before Marshall's death. Their son Alfred died in 1907 and his ashes were interred next to Marshall's. The elder Alfred died in 1917 in Nice during World War I; his ashes was at his request also interred next to Marshall's in 1920.

Marshall was one of the most celebrated cooks of her time and one of the foremost cookery writers of the Victorian age, particularly on ice cream. Her recipes were renowned for their detail, simplicity and accuracy. For her work on ice cream and other frozen desserts, Marshall in her lifetime earned the nickname "Queen of Ices". Only a single book on ice cream is known from England before Marshall's work and she helped popularise ice cream at a time when the concept was still novel in England and elsewhere, particularly through the portable ice cream freezer and the ice cream cone. Before Marshall's writings and innovations, ice cream was often sold frozen to metal rods which had to be returned after all had been licked off and was mainly enjoyed by just the upper classes. She increased the popularity of ice cream to such an extent that she was credited for causing an increase in ice imports from Norway. In 1901, she became the first person known to have suggested the use of

culinary

Culinary arts are the cuisine arts of outline of food preparation, food preparation, cooking and food presentation, presentation of food, usually in the form of meals. People working in this field – especially in establishments such as res ...

entrepreneur, inventor, and celebrity chef. An unusually prominent businesswoman for her time, Marshall was particularly known for her work on ice cream and other frozen desserts, which in Victorian England earned her the moniker "Queen of Ices". Marshall popularised ice cream in England and elsewhere at a time when it was still a novelty and is often regarded as the inventor of the modern ice cream cone. Through her work, Marshall may be largely responsible for both the look and popularity of ice cream today.

It is unknown when and where Marshall first learned to cook; scant later writings allude to having learnt from chefs in England, France and Austria. She began her career in 1883 through the founding of the Marshall's School of Cookery, which taught high-end English and French cuisine and grew to be a renowned culinary school. Marshall wrote four well-received cookbooks, two of which were devoted to ice cream and other desserts. Together with her husband Alfred, Marshall operated a variety of different businesses. From 1886 onwards she published her own magazine, ''The Table'', which included weekly recipes and at times articles written by Marshall on various topics, both serious and frivolous. Marshall had an intense interest in technology; she was an early adopter of new technologies, frequently wrote about her own predictions of the future, and invented several new appliances.

Though she was one of the most celebrated cooks of her time and one of the foremost cookery writers of the Victorian age, Marshall rapidly faded into obscurity after her death and was largely forgotten until she once more achieved renown in the late twentieth century. Technology invented or conceptualised by Marshall, including her ice cream freezer and the idea of creating ice cream with the use of liquid nitrogen

Liquid nitrogen—LN2—is nitrogen in a liquid state at low temperature. Liquid nitrogen has a boiling point of about . It is produced industrially by fractional distillation of liquid air. It is a colorless, low viscosity liquid that is wide ...

, have since become repopularised.

Personal life

Agnes Bertha Smith was born on 24 August 1855 inWalthamstow

Walthamstow ( or ) is a large town in East London, east London, England, within the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Greater London and the Historic counties of England, ancient county of Essex. Situated northeast of Chari ...

, Essex. She was the daughter of John Smith, who worked as a clerk, and his wife Susan. Both of her parents are shadowy figures about whom little is known. The early life of Marshall herself is also poorly known. From later evidence it can be deduced that she had at least one brother and that her father died at a relatively early age.

After John's death, Susan remarried to a man called Charles Wells, with whom she fathered the four children Eliza, Thomas, John and Ada. Ada later worked as Marshall's housekeeper. Nothing is known of how, where or when she learned to cook. According to a later article in the '' Pall Mall Gazette'', Marshall had "made a thorough study of cookery since she was a child, and has practiced at Paris and with Vienna's celebrated chefs". In the preface to her first book, Marshall wrote that she had received "practical training and lessons, through several years, from leading English and Continental authorities".

She married Alfred William Marshall, son of a builder named Thomas Marshall, on 17 August 1878 at St. George's Church, Hanover Square

St George's, Hanover Square, is an Anglican church, the parish church of Mayfair in the City of Westminster, central London, built in the early eighteenth century as part of a project to build fifty new churches around London (the Queen Anne Ch ...

. The couple had four children: Ethel (born 1879), Agnes (called "Aggie", also born 1879), Alfred (born 1880) and William (born 1882).

Career

Business ventures and ''The Book of Ices''

Marshall was a formidable businesswoman even by modern standards. In January 1883, Marshall and her husband bought the National Training School of Cookery, located at 31 Mortimer Street in London, and renamed it to the Marshall's School of Cookery. The school was purchased from Felix and Mary Ann Lavenue, who ran a cookery school of their own at 57 Mortimer Street. The original records of the transaction have not survived but later evidence suggests that Marshall bought the school with her own money. That the couple purchased the school together and that it was clear that Marshall herself was the main owner and driving force was unusual, since women had only very recently earned the legal right to purchase property through the Married Women's Property Act 1882. Marshall's step-brother John was employed as the school's manager.

The Marshall's School of Cookery mainly taught a mixture of high-end English and French cuisine and swiftly became one of only two major cookery schools in the city, alongside the

Marshall was a formidable businesswoman even by modern standards. In January 1883, Marshall and her husband bought the National Training School of Cookery, located at 31 Mortimer Street in London, and renamed it to the Marshall's School of Cookery. The school was purchased from Felix and Mary Ann Lavenue, who ran a cookery school of their own at 57 Mortimer Street. The original records of the transaction have not survived but later evidence suggests that Marshall bought the school with her own money. That the couple purchased the school together and that it was clear that Marshall herself was the main owner and driving force was unusual, since women had only very recently earned the legal right to purchase property through the Married Women's Property Act 1882. Marshall's step-brother John was employed as the school's manager.

The Marshall's School of Cookery mainly taught a mixture of high-end English and French cuisine and swiftly became one of only two major cookery schools in the city, alongside the The National Training School Of Cookery

The National Training School Of Cookery was a teaching organisation in London from 1873 to 1962. It changed its name to The National Training School of Cookery and Other Branches of Domestic Economy in 1902 and, in 1931 became The National Traini ...

. A year into the school's operation, Marshall was lecturing classes of up to 40 students five to six times a week and within a few years the school reportedly had nearly 2,000 students, lectured in cooking by prominent specialists. Among the lectures offered at the school were lessons in curry-making, taught by an English colonel who had once served in India and a class in French high-end cuisine taught by a Le Cordon Bleu

Le Cordon Bleu (French for " The Blue Ribbon") is an international network of hospitality and culinary schools teaching French ''haute cuisine''. Its educational focuses are hospitality management, culinary arts, and gastronomy. The instituti ...

graduate. The couple also operated a business involving the creation and retail of cooking equipment, an agency that supplied domestic staff, as well as a food shop that sold flavorings, spices and syrups.

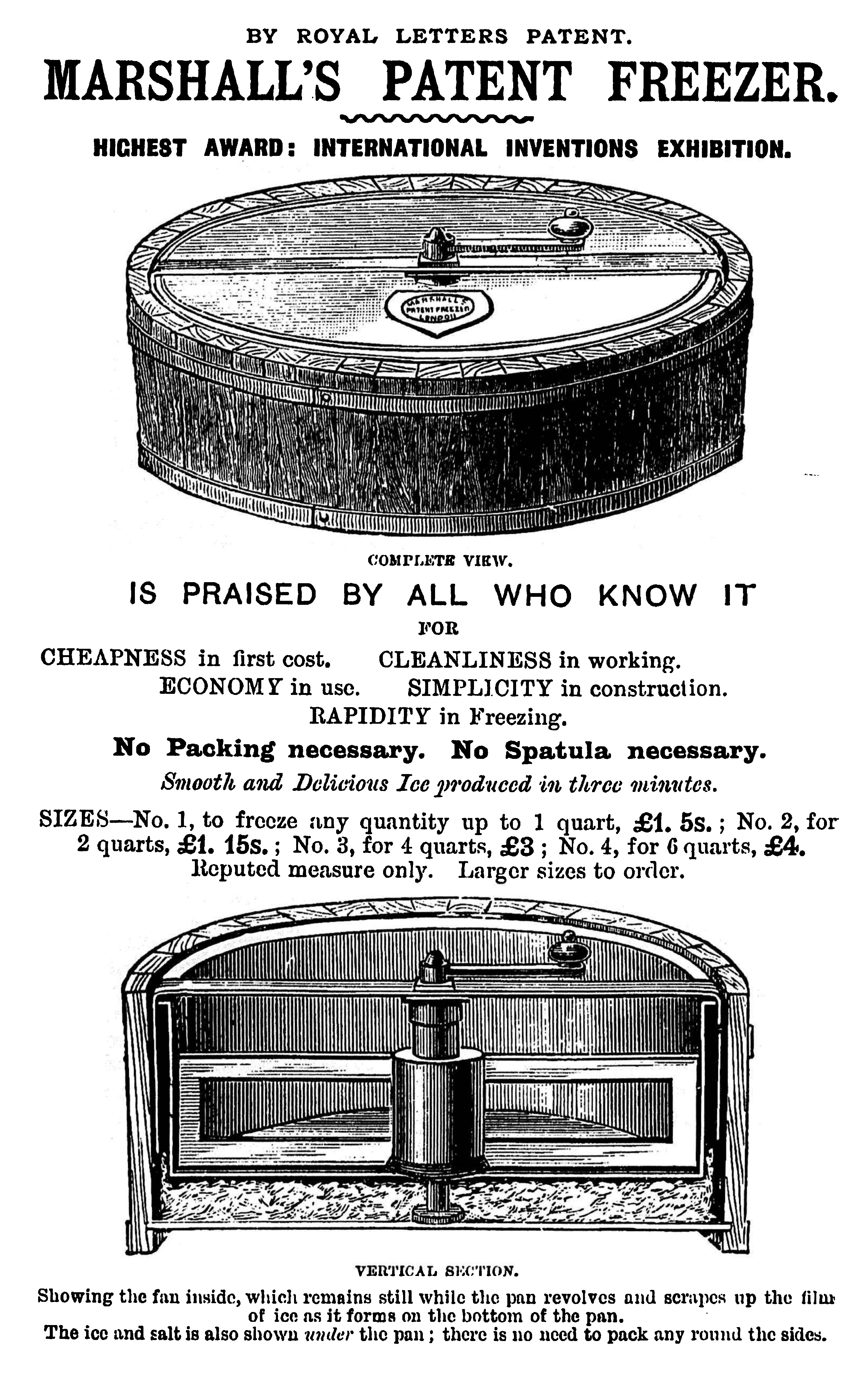

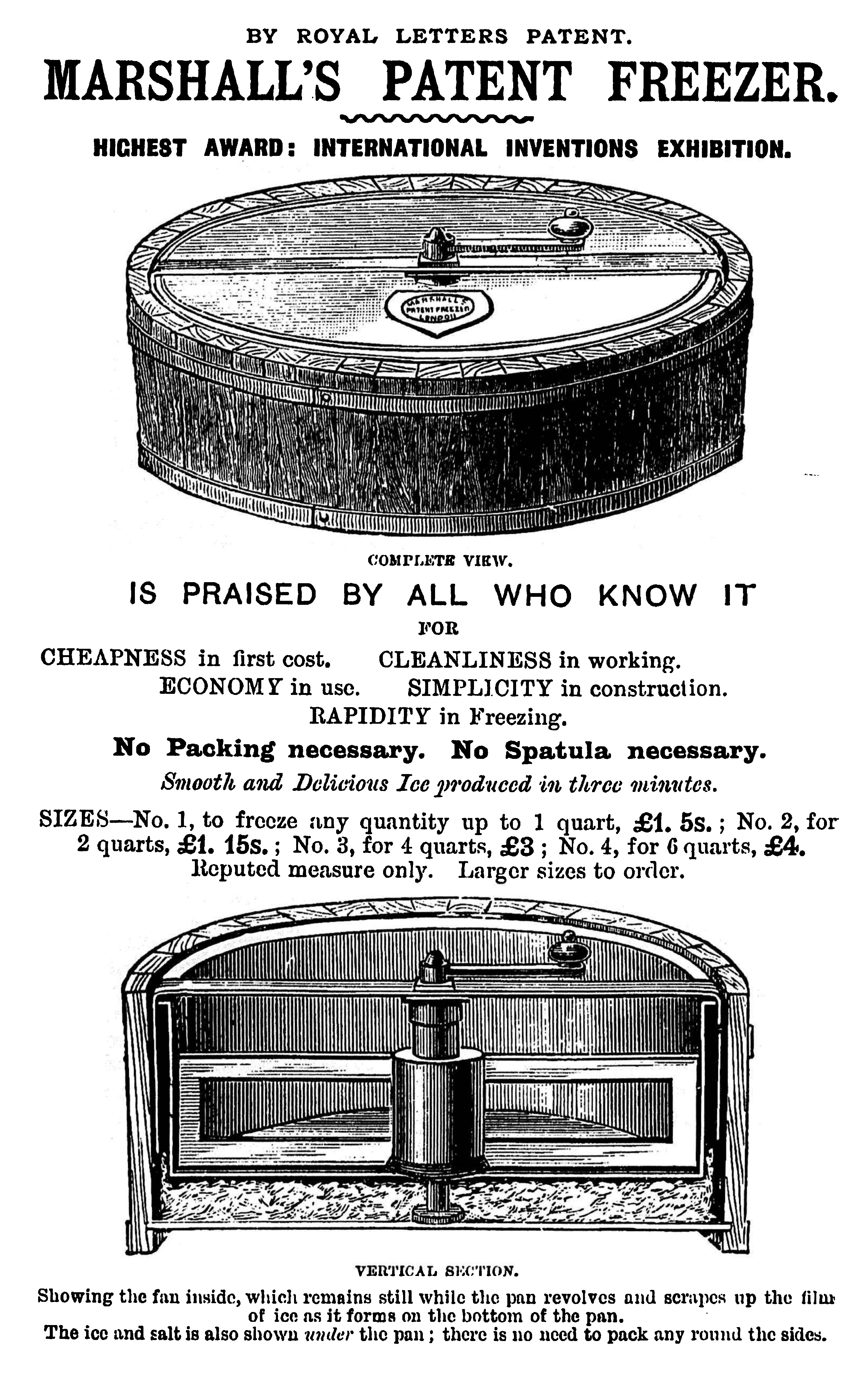

In 1885, Marshall wrote and published her first book, ''The Book of Ices'', which contained 177 different ice cream and dessert recipes. ''The Book of Ices'' was self-published through the cookery school and was well-written and thoroughly illustrated. In addition to the recipes, the book also promoted some of Marshall's ice cream-related inventions, including the Marshall's Patent Freezer. ''The Book of Ices'' received favourable reviews from critics but it mainly received attention in various local newspapers and did not reach the national-level media.

The Marshall's Patent Freezer, patented by her husband, was able to freeze a pint of ice cream in less than five minutes and her design remains faster and more reliable than even many modern electric ice cream machines. Marshall also designed an extensive range of over a thousand different molds for use with ice cream. She also invented an "ice-breaking machine", an "ice cave" (an insulated box for storing ice cream), and several different kitchen appliances and food ingredients, sold by her company.

''The Table'' and ''A Pretty Luncheon''

From 1886 onwards, Marshall and her husband published the magazine ''The Table'', a weekly paper on "Cookery, Gastronomy ndfood amusements". Every issue of ''The Table'' was accompanied by a weekly recipe contributed by Marshall and for the first six month (and periodically thereafter) the magazine also included weekly articles written by Marshall on an assortment of subjects she took an interest in. According to the historian John Deith, these articles were written in a "chatty, witty and ironic,

From 1886 onwards, Marshall and her husband published the magazine ''The Table'', a weekly paper on "Cookery, Gastronomy ndfood amusements". Every issue of ''The Table'' was accompanied by a weekly recipe contributed by Marshall and for the first six month (and periodically thereafter) the magazine also included weekly articles written by Marshall on an assortment of subjects she took an interest in. According to the historian John Deith, these articles were written in a "chatty, witty and ironic, Jane Austen

Jane Austen (; 16 December 1775 – 18 July 1817) was an English novelist known primarily for her six major novels, which interpret, critique, and comment upon the British landed gentry at the end of the 18th century. Austen's plots of ...

esque style". Among the articles she wrote were musings on hobbies such as riding, playing tennis, and gardening, as well as spirited attacks on The National Training School Of Cookery (the main competitor of her own school). She also published articles in support of improving the working conditions of kitchen staff in aristocratic homes, which she wrote "received less respect than carriage horses". At one point, Marshall authored a highly critical article on a financial venture of Horatio Bottomley

Horatio William Bottomley (23 March 1860 – 26 May 1933) was an English financier, journalist, editor, newspaper proprietor, swindler, and Member of Parliament. He is best known for his editorship of the popular magazine ''John Bull (maga ...

, who printed ''The Table'', which resulted in Bottomley threatening legal action (which never materialised) and refusing to print future critical material. Marshall responded by simply calling Bottomley "impudent" and partnering with another printer.

In 1887, Marshall was preparing to publish her second book, ''Mrs A. B. Marshall's Book of Cookery'', set for publication in February 1888. Wishing to reach a wider audience than she had with ''The Book of Ices'', Marshall decided to embark on a promotional tour across England which she dubbed ''A Pretty Luncheon''. In addition to promoting the upcoming book, the tour also served to bring attention to her cookery school and to her various businesses. The tour saw Marshall cooking meals in front of large audiences, helped on stage by a team of assistants. ''A Pretty Luncheon'' began in August 1888, with the shows held in Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds, Newcastle and Glasgow. On 15 and 22 October, Marshall held two successive shows at the Willis's Rooms in London which received unanimous and widespread critical acclaim. Encouraged by the success of the first part of the tour, Marshall embarked on the second part of the tour in the autumn and winter, cooking in front of audiences in Bath

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Plac ...

, Brighton

Brighton () is a seaside resort and one of the two main areas of the City of Brighton and Hove in the county of East Sussex, England. It is located south of London.

Archaeological evidence of settlement in the area dates back to the Bronze A ...

, Bristol, Cheltenham

Cheltenham (), also known as Cheltenham Spa, is a spa town and borough on the edge of the Cotswolds in the county of Gloucestershire, England. Cheltenham became known as a health and holiday spa town resort, following the discovery of mineral s ...

, Colchester, Leicester

Leicester ( ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city, Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest settlement in the East Midlands.

The city l ...

, Liverpool, Nottingham, Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

, Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'Sh ...

, Southampton and Worcester. Some of her shows had as many as 500–600 attendants in the audience. According to Deith, ''A Pretty Luncheon'' made Marshall into "the most talked about cook in England" and "the best known cook since Soyer Soyer is a surname of French and Turkish origin. It may refer to:

* Alexis Soyer (1810–1858), French chef

*Cyril Soyer (born 1978), French judoka

*David Soyer (1923–2010), American cellist

* Elizabeth Emma Soyer (1813–1842), British painter

* ...

".

Further writings and late career

After some delays, ''Mrs A. B. Marshall's Book of Cookery'' was published on 12 May 1888. Well-planned, well-written and practically arranged, the book was an enormous success, selling over 60,000 copies and being published in fifteen editions. ''Book of Cookery'' cemented Marshall's reputation among the prominent cooks of England. In ''Book of Cookery'', Marshall mentioned putting ice cream in an edible cone, the earliest known reference in English to ice cream cones. Her cone, which she called a "cornet", was made fromground almonds

Almond meal, almond flour or ground almond is made from ground sweet almonds. Almond flour is usually made with blanched almonds (no skin), whereas almond meal can be made with whole or blanched almonds. The consistency is more like corn meal than ...

and might have been the first portable and edible ice cream cone. Marshall's cornet bore little resemblance to its modern counterpart and was intended to be eaten with utensils but Marshall is accordingly frequently considered to be the inventor of the modern ice cream cone.

In the summer of 1888, Marshall went on a tour to the United States. Her lecture received a positive review in the ''Philadelphia Bulletin

The ''Philadelphia Bulletin'' was a daily evening newspaper published from 1847 to 1982 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was the largest circulation newspaper in Philadelphia for 76 years and was once the largest evening newspaper in the United ...

'' but she did not achieve the same level of acclaim in America as she had in England. Marshall is recorded to have provided Christmas dinners for the "Hungry Poor" in Stepney and Poplar in London in 1889. She also provided warm soup to the poor throughout the winter of that year.

''Book of Cookery'' was followed by her third book, ''Mrs A. B. Marshall's Larger Cookery Book of Extra Recipes'' (1891), dedicated "by permission" to Princess Helena and devoted to more high-end cuisine than the previous book. Marshall's fourth and final book, ''Fancy Ices'', was published in 1894 and was a follow-up to ''The Book of Ices''. The cooking books written by Marshall contained recipes she had created herself, unlike many other books of the age which were simply compilations of work by others, and she assured readers that she had tried out every recipe herself. Among the various foods featured, Marshall's books contain the earliest known written recipe for Cumberland rum butter

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 1974 ...

.

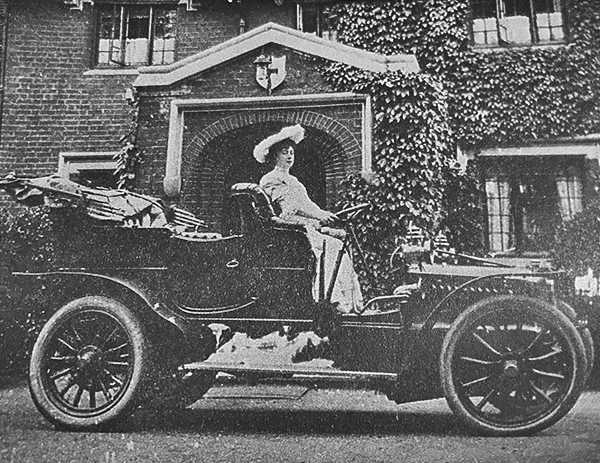

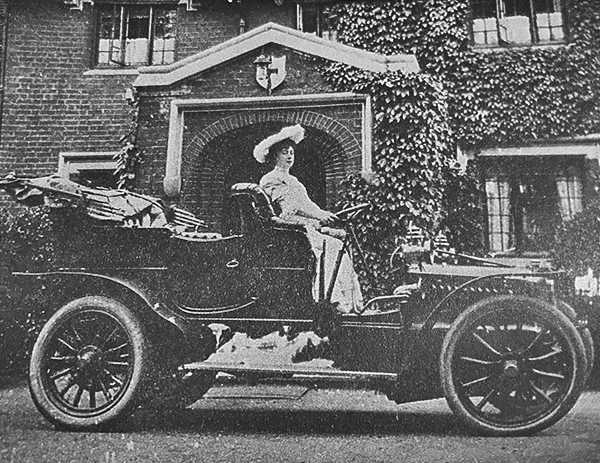

In the 1890s, Marshall also resumed her weekly articles on various subjects in ''The Table'', writing on both serious and frivolous topics. Among the articles she wrote during this time were musings on the poor quality of food on trains and at railway stations, a denouncement of canned food, a lament on the lack of good-quality tomatoes in her area, support for women's rights, criticism of superstition, and speculations on future technology. She made several correct predictions for the future; Marshall predicted that motor cars would "revolutionise trade and facilitate the travelling of the future", speculated on how refrigerated lorries could be used to deliver fresh food nationwide, predicted that larger stores would bring small provision shops out of business, and that chemically purified water might one day be provided to all homes as a matter of course. Marshall was greatly interested in technological developments and her shop was an early adopter of technologies such as the dishwasher, the teasmade

A teasmade is a machine for making tea automatically, which was once common in the United Kingdom and some Commonwealth countries. Teasmades generally include an analogue alarm clock and are designed to be used at the bedside, to ensure tea is ...

and automatic doors.

Death and legacy

In 1904, Marshall fell from a horse and suffered wounds that she never properly recovered from. She died the next year, in the early morning of 29 July 1905 at ''The Towers'', Pinner. ''The Towers'' was a large estate purchased and refurbished by Marshall in 1891. Marshall was cremated at the Golders Green Crematorium and her ashes were interred at the Paines Lane Cemetery in Pinner. Alfred remarried within a year of her death to Gertrude Walsh, a former secretary that Marshall had previously fired. The two had likely been engaged in an affair before Marshall's death. Their son Alfred died in 1907 and his ashes were interred next to Marshall's. The elder Alfred died in 1917 in Nice during World War I; his ashes was at his request also interred next to Marshall's in 1920.

Marshall was one of the most celebrated cooks of her time and one of the foremost cookery writers of the Victorian age, particularly on ice cream. Her recipes were renowned for their detail, simplicity and accuracy. For her work on ice cream and other frozen desserts, Marshall in her lifetime earned the nickname "Queen of Ices". Only a single book on ice cream is known from England before Marshall's work and she helped popularise ice cream at a time when the concept was still novel in England and elsewhere, particularly through the portable ice cream freezer and the ice cream cone. Before Marshall's writings and innovations, ice cream was often sold frozen to metal rods which had to be returned after all had been licked off and was mainly enjoyed by just the upper classes. She increased the popularity of ice cream to such an extent that she was credited for causing an increase in ice imports from Norway. In 1901, she became the first person known to have suggested the use of

In 1904, Marshall fell from a horse and suffered wounds that she never properly recovered from. She died the next year, in the early morning of 29 July 1905 at ''The Towers'', Pinner. ''The Towers'' was a large estate purchased and refurbished by Marshall in 1891. Marshall was cremated at the Golders Green Crematorium and her ashes were interred at the Paines Lane Cemetery in Pinner. Alfred remarried within a year of her death to Gertrude Walsh, a former secretary that Marshall had previously fired. The two had likely been engaged in an affair before Marshall's death. Their son Alfred died in 1907 and his ashes were interred next to Marshall's. The elder Alfred died in 1917 in Nice during World War I; his ashes was at his request also interred next to Marshall's in 1920.

Marshall was one of the most celebrated cooks of her time and one of the foremost cookery writers of the Victorian age, particularly on ice cream. Her recipes were renowned for their detail, simplicity and accuracy. For her work on ice cream and other frozen desserts, Marshall in her lifetime earned the nickname "Queen of Ices". Only a single book on ice cream is known from England before Marshall's work and she helped popularise ice cream at a time when the concept was still novel in England and elsewhere, particularly through the portable ice cream freezer and the ice cream cone. Before Marshall's writings and innovations, ice cream was often sold frozen to metal rods which had to be returned after all had been licked off and was mainly enjoyed by just the upper classes. She increased the popularity of ice cream to such an extent that she was credited for causing an increase in ice imports from Norway. In 1901, she became the first person known to have suggested the use of liquid nitrogen

Liquid nitrogen—LN2—is nitrogen in a liquid state at low temperature. Liquid nitrogen has a boiling point of about . It is produced industrially by fractional distillation of liquid air. It is a colorless, low viscosity liquid that is wide ...

to freeze ice cream (and the first to suggest using liquified gas on food in general). Marshall imagined that this would be the ideal method to make ice cream since the ice cream could be created in seconds and the ice crystals resulting from this method would be tiny, as desired.

Despite her fame in life, Marshall's reputation declined rapidly after her death and her name faded into obscurity. Her husband continued to operate their businesses but they declined without Marshall's personality and drive. In 1921, the company was sold and became a limited company and in 1954 it ceased operations. Marshall's cookery school remained in operation until the outbreak of World War II. ''The Table'' also continued to be published to around the same time. The rights to her books were sold off to the publishing house Ward Lock at some time in 1927 or 1928, though Ward Lock had little interest in keeping them in print. In the 1950s, a fire destroyed much of Marshall's personal papers which further pushed her into obscurity.

More recently, from the late 20th century onwards, Marshall's reputation has been restored as one of the most prominent cooks of the Victorian age. The cookery writer Elizabeth David referred to her as the "famous Mrs Marshall" in the posthumously published '' Harvest of the Cold Months'' (1994) and the author Robin Weir

Robin may refer to:

Animals

* Australasian robins, red-breasted songbirds of the family Petroicidae

* Many members of the subfamily Saxicolinae (Old World chats), including:

** European robin (''Erithacus rubecula'')

**Bush-robin

** Forest ...

declared her to have been "the greatest Victorian ice cream maker" in a 1998 biographical study. Weir assessed Marshall in 2015 as a "unique one-woman industry" whose achievements were "arguably unequalled" and who "deserves much more credit than she has been given by history". Since the late 20th century, Marshall's books have once more been reprinted and ice cream freezers based on her original designs are once again in commercial use. Using liquid nitrogen to freeze ice cream has also become an increasingly popular trend. A liquid nitrogen ice cream store that was inspired by Marshall's proposed technique was opened in 2014 in St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the Greater St. Louis, ...

and named "Ices Plain & Fancy" after her book.

References