Just before the 20th century began, most of Africa, with the exception of Ethiopia, Somalia and Liberia, was under colonial rule. By the 1980s, most nations were independent. Military systems reflect this evolution in several ways:

*Growth of indigenous knowledge and skill in handling modern arms

*Established colonial armies of mainly indigenous troops officered by Europeans

*Rebellions, resistance and "mop up" operations

*Weakening of European colonial power due to World War I and World War II

*

Decolonization

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on separatism, in ...

and the transition to the militaries of the new African states

*Wars of national liberation across the continent particularly the northern and southern regions

*Frequent tribal or civil wars across the continent

*Frequent military coups against the post colonial regimes

*Continued strength of regional powers like Egypt and South Africa

*The rise of asymmetric forces and failed states

*The rise of international forces and bureaucracies

*Continued challenges and evolution into the 21st century

For events prior to 1800, see

African military systems to 1800

African military systems before 1800 refers to the evolution of military systems on the African continent prior to 1800, with emphasis on the role of indigenous states and peoples, whose leaders and fighting forces were born on the continent, with ...

. For events between 1800 and 1900, see

African military systems (1800–1900)

African military systems (1800–1900) refers to the evolution of military systems on the African continent after 1800, with emphasis on the role of indigenous states and peoples within the African continent. Only major military systems or innovat ...

. For an overall view of the military history of Africa by region, see

Military History of Africa

The military history of Africa is one of the oldest military histories in the world. Africa is a continent of many regions with diverse populations speaking hundreds of different languages and practicing an array of cultures and religion

Reli ...

. Below are the major activities and events that shaped African military systems into the 20th and 21st century.

Rebellions, resistance and "mop up" operations

By 1900, the imperial powers had won most of the initial major battles against indigenous powers, or had occupied strategic areas such as coastlines, to secure their dominance. Colonies were established or expanded across the landscape- sometimes eagerly, as in the case of major mineral finds- or sometimes forced on the imperial center by the outlying actions of grasping or ambitious settlers, merchants, military officers, and bureaucrats. The complexity of African responses to the new order defies a simple narrative of

good versus evil

In religion, ethics, philosophy, and psychology "good and evil" is a very common dichotomy. In cultures with Manichaeism, Manichaean and Abrahamic religious influence, evil is perceived as the dualistic cosmology, dualistic antagonistic oppos ...

. In some cases the intruders were welcomed as useful allies, saviours or counterweights in local disputes. In other cases, they were bitterly resisted. In some areas, the colonial regimes brought massive land confiscations, violence and what some see as genocide. In others they brought education, better security, new products and skills, and improved standards of infrastructure and living.

The historical record shows destructive operations by both indigenous hegemony and foreign intruders. Some of the methods used by the colonial powers are also reflected in armed European conflicts. Murdered peasants, livestock and grain seizures, arbitrary quartering of troops, and massive theft and looting by roaming armies for example, are common occurrences in various eras of European military history. Napoleon's brutal

occupation of Spain is but one example.

[ Nor did the colonial era see a complete cessation of purely internal disputes and wars. These were much reduced from the 19th century due to the colonial conquests, but still occurred in some areas with varying levels of intensity. Some limited areas of North Africa, such as Libya, were still under the sway of non-European powers like the Ottomans, adding to the complexity of the colonial situation.][Gann, L. H. and Duignan, Peter, ''Burden of Empire – an Appraisal of Western Colonialism in Africa South of the Sahara'', Pall Mall Press. London 1968. Reviewed in ]

Whatever the balance sheet in different areas, it is clear that consolidation and exploitation of the new territories involved a large measure of coercion, and this often provoked a military reply. The exact form of such coercion varied- it could be land seizures, forced labor, hut taxes, interference in local quarrels, monopolism of trade, small-scale punitive expeditions, or outright warfare of genocidal intensity as that waged by the Germans against the Herero

Herero may refer to:

* Herero people, a people belonging to the Bantu group, with about 240,000 members alive today

* Herero language, a language of the Bantu family (Niger-Congo group)

* Herero and Namaqua Genocide

* Herero chat, a species of b ...

and Namaqua (or ''Nama'') in southwest Africa.guerilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tac ...

, and full scale clashes. Only a few of these varying responses are considered here in terms of African military systems.

*Cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

: the demise of the Sokoto Caliphate

The Sokoto Caliphate (), also known as the Fulani Empire or the Sultanate of Sokoto, was a Sunni Muslim caliphate in West Africa. It was founded by Usman dan Fodio in 1804 during the Fulani jihads after defeating the Hausa Kingdoms in the Ful ...

, one of the major powers in the savannah regions of West Africa

*Guerilla warfare: the Herrero and Nama versus the Germans

*Major warfare: the massive Rif War

The Rif War () was an armed conflict fought from 1921 to 1926 between Spain (joined by History of France, France in 1924) and the Berbers, Berber tribes of the mountainous Rif region of northern Morocco.

Led by Abd el-Krim, the Riffians at ...

in Spanish Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

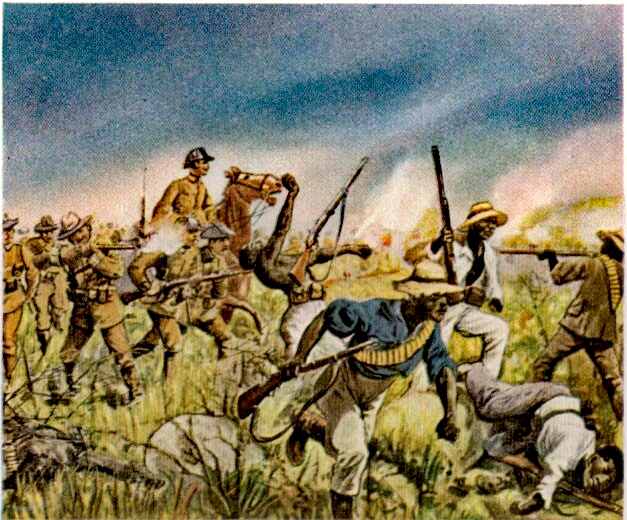

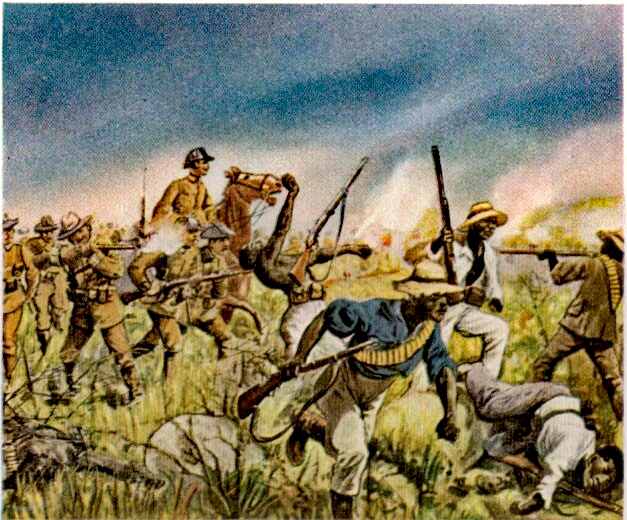

Twilight of the mounted man

West Africa's largest single state during the 19th century, the Sokoto Caliphate

The Sokoto Caliphate (), also known as the Fulani Empire or the Sultanate of Sokoto, was a Sunni Muslim caliphate in West Africa. It was founded by Usman dan Fodio in 1804 during the Fulani jihads after defeating the Hausa Kingdoms in the Ful ...

of northern Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

moved into the 20th century with its military system intact- the traditional mix of infantry and cavalry. New powers and technologies however were appearing on the scene. Some cavalry-strong states like the Tukolor

__NOTOC__

The Tukulor people ( ar, توكولور), also called Toucouleur or Haalpulaar, are a West African ethnic group native to Futa Tooro region of Senegal. There are smaller communities in Mali and Mauritania. The Toucouleur were Islamized ...

, made sporadic attempts to incorporate weapons like artillery but integration was poor. Sokoto largely stuck to the old ways, was annexed and incorporated in the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

in 1903. Sokoto's soldiers, whether horse or foot, had very few guns. The Caliphate's tactics were to attack in a series of set-piece battles, with thundering cavalry charges leading the way, followed by infantry armed with bow, sword and spear. As the fighting men surged forward into combat, their movements were accompanied by loud music and drums These however were not enough, and assaults were quickly routed by the modern weaponry of virtually invulnerable British squares

In Euclidean geometry, a square is a regular quadrilateral, which means that it has four equal sides and four equal angles (90- degree angles, π/2 radian angles, or right angles). It can also be defined as a rectangle with two equal-length a ...

. Traditional fortified cities and forts also made a poor showing and were usually rapidly breached by British artillery.[Risto Marjomaa, ''War on the Savannah: The Military Collapse of the Sokoto Caliphate under the Invasion of the British Empire, 1897–1903'' – Reviewed in ] Thus ended the heyday of the centuries-old West African cavalry-infantry combination. In Southern Africa the mounted men of the Boer

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape Colony, Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controll ...

forces also saw defeat in 1902, as imperial troops implemented a blockade and scorched earth policy against their mobile tactics. This outcome paralleled general developments on the battlefield, as mounted forces gradually lost their relevance under modern firepower.[Archer Jones, The Art of War in the Western World, University of Illinois Press: 1987, pp. 387–463]

Guerilla warfare in Southwest Africa

Guerilla warfare was a common military response in many areas of Africa during the early colonial era. The bitter 1904–1907 war between imperial Germany and the

Guerilla warfare was a common military response in many areas of Africa during the early colonial era. The bitter 1904–1907 war between imperial Germany and the Herero

Herero may refer to:

* Herero people, a people belonging to the Bantu group, with about 240,000 members alive today

* Herero language, a language of the Bantu family (Niger-Congo group)

* Herero and Namaqua Genocide

* Herero chat, a species of b ...

tribe in today's Namibia is an illustration of this pattern, with tragic consequences for the indigenous resistance, including concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

s, forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

and a scorched earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. Any assets that could be used by the enemy may be targeted, which usually includes obvious weapons, transport vehicles, communi ...

extermination policy that even some contemporary Germans found repugnant. In August 1904, German colonial troops under commander Lothar von Trotha

General Adrian Dietrich Lothar von Trotha (3 July 1848 – 31 March 1920) was a German military commander during the European new colonial era. As a brigade commander of the East Asian Expedition Corps, he was involved in suppressing the Boxe ...

, carried out a ruthless cleansing campaign against the recalcitrant Herero and Nama tribes, who had risen in revolt against increasing white demands for land, labor and cattle. Several white farmers were killed in the rising and thousands of cattle were collected. General von Trotha counterattacked with well equipped modern troops, and refused Herero offers to negotiate surrender. His extermination proclamation, issued on October 2, 1904, read in part: ''"Every Herero found within German borders, with or without guns, with or without livestock, will be shot. I will not give shelter to any Herero women or children.."'' An estimated 75,000 Herero and Nama were slaughtered. Thousands were killed in battle and in the aftermath, victorious German forces chased the survivors into the waterless Omaheke Desert, physically preventing any from returning. Thousands of men, women and children died of thirst and starvation. Many of those Herero and Nama that survived this slaughter were sent to specially erected concentration camps or to forced employment on German commercial farms. Hundreds of civilians died due to the inhumane conditions in the camps and on the farms. The liquidation of the blacks opened the way for the seizure of land and cattle and consolidated European control over the territory.

The Rif Wars

The Rif wars are relatively obscure compared to the well known Ethiopian victory at Adowa or that of the Zulu at Isandhlwana. Nevertheless, it was a significant demonstration of large scale warfare by indigenous troops, and fighters of the Moroccan Rif and J'bala tribes dealt several defeats to Spanish forces in Morocco over their course. It took a massive collaboration by French and Spanish forces to finally liquidate resistance in 1925.

Early defeats of the Spanish

The Rif War of 1920, also called the Second Moroccan War, was fought between Spain (later assisted by France) and the Moroccan Rif and J'bala tribes. Spain moved to conquer the lands around Melilla and Ceuta and the eastern territory from the Jibala tribes during the 1920s. In 1921 Spanish troops suffered a momentous defeat — known in Spain as the disaster of Annual — by the forces of Abd el-Krim

Muhammad ibn Abd al-Karim al-Khattabi (; Tarifit: Muḥend n Ɛabd Krim Lxeṭṭabi, ⵎⵓⵃⵏⴷ ⵏ ⵄⴰⴱⴷⵍⴽⵔⵉⵎ ⴰⵅⵟⵟⴰⴱ), better known as Abd el-Krim (1882/1883, Ajdir, Morocco – 6 February 1963, Cairo, Egypt) ...

, the leader of the Rif tribes. The Spanish were pushed back and during the following five years, occasional battles were fought between the two. In a bid to break the stalemate, the Spanish military turned to the use of chemical weapon

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as a ...

s against the Riffians. The Berber tribesmen had a long tradition of fierce fighting skills, combined with high standards of fieldcraft and marksmanship. They were capably led by Abd el-Krim who showed both military and political expertise. The elite of the Riffian forces formed regular units which according to Abd el-Krim, quoted by the Spanish General Manual Goded, numbered 6–7,000. The remaining Riffians were tribal militia selected by their Caids and not liable to serve away from their homes and farms for more than fifteen consecutive days. General Goded estimates that at their peak the Riffian forces numbered about 80,000 men. Spanish troops in Morocco were initially mainly Metropolitan conscripts. While capable of enduring much hardship they were poorly trained and supplied, with widespread corruption reported amongst the officer corps. Accordingly, much reliance was placed on the limited number of professional units comprising the Spanish "Army of Africa". Since 1911 these had included regiments of Moorish Regulares. A Spanish equivalent of the French Foreign Legion

The French Foreign Legion (french: Légion étrangère) is a corps of the French Army which comprises several specialties: infantry, Armoured Cavalry Arm, cavalry, Military engineering, engineers, Airborne forces, airborne troops. It was created ...

, the Tercio de Extranjeros ("Regiment of Foreigners"), was also formed in 1920. The regiment's second commander was General Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War ...

.

Entry of France into the war and collaboration between France and Spain

In May 1924, the French Army had established a line of posts north of the Ouregha River in disputed tribal territory. On 13 April 1925, an estimated 8,000 Rifs attacked this line and in two weeks 39 of 66 French posts had been stormed or abandoned. The French accordingly intervened on the side of Spain, employing up to 300,000 well trained and equipped troops from Metropolitan, North African, Senegalese and Foreign Legion units. French deaths in what had now become a major war are estimated at about 12,000. Superior manpower and technology soon resolved the course of the war in favour of France and Spain. The French troops pushed through from the south while the Spanish fleet secured Alhucemas Bay by an amphibious landing, and began attacking from the north. After one year of bitter resistance, Abd el-Krim, the leader of both the tribes, surrendered to French authorities, and in 1926 Spanish Morocco was finally retaken.

Impact of World War I and World War II

The massive conflicts of

The massive conflicts of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

were to have important effects on African military development. Hundreds of thousands of African troops served in Europe and the Pacific and gained new military skills via their exposure to new forms of organization, handling of advanced weaponry, and intense modern combat. The exposure to a wider world during the two conflicts opened up a sense of new possibilities, and opportunities. These were eventually to be reflected in demands for greater freedom in homeland colonies. The success of peoples like the Japanese also demonstrated that European forces were not invincible, and post-war weakening of many former imperial powers provided new scope in challenging the colonial order.

World War I

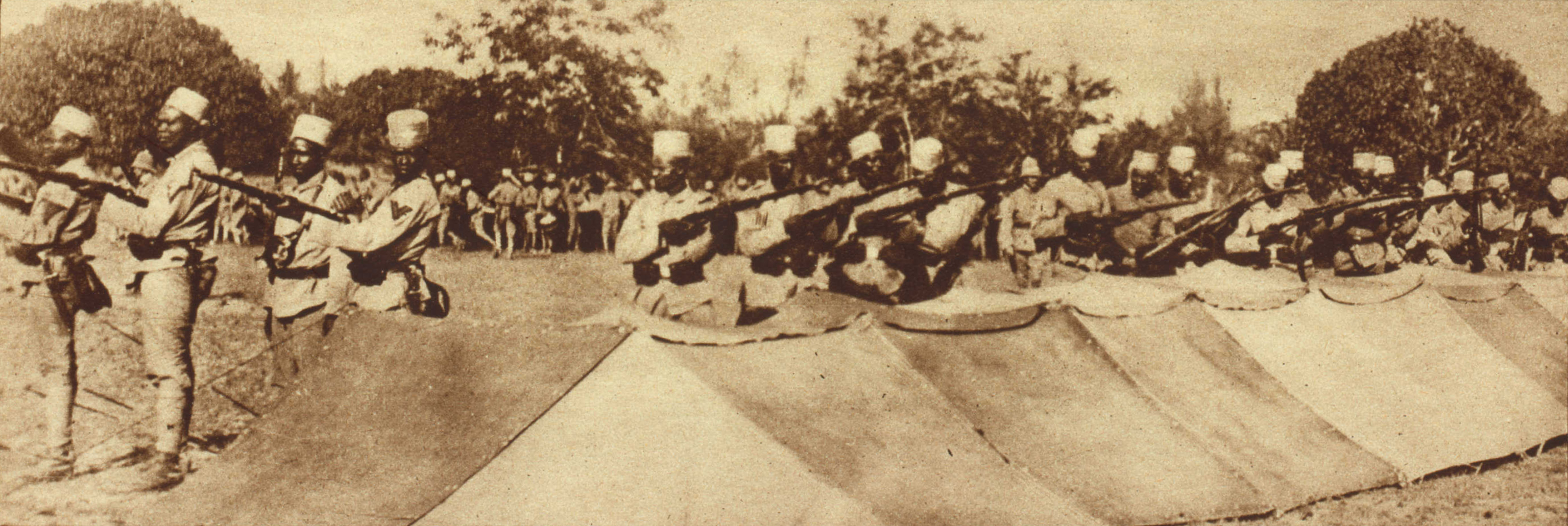

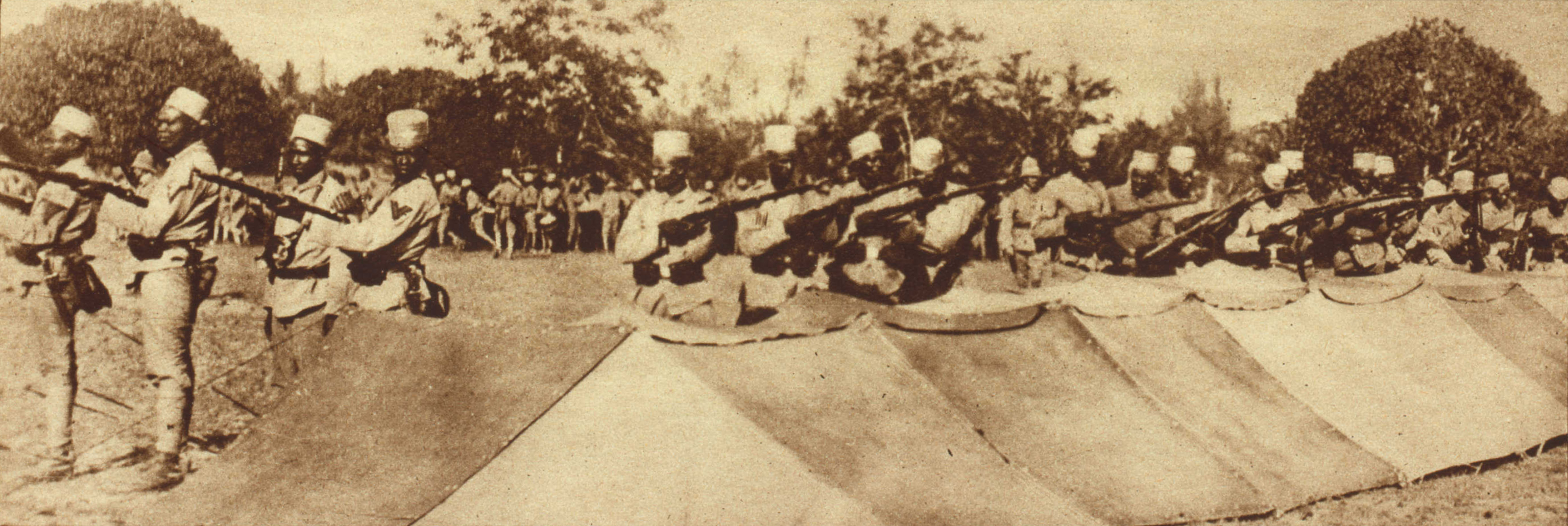

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

deployed hundreds of thousands of African fighting men to aid its cause, including some 300,000 North Africans, some 250,000 West Africans and thousands more from other regions. Over 140,000 African soldiers for example, fought on the Western Front during World War I and thousands of others fought at Gallipoli

The Gallipoli peninsula (; tr, Gelibolu Yarımadası; grc, Χερσόνησος της Καλλίπολης, ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles ...

and in the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

. French West African troops fought and died in all the major battles of the Western Front, from Verdun

Verdun (, , , ; official name before 1970 ''Verdun-sur-Meuse'') is a large city in the Meuse department in Grand Est, northeastern France. It is an arrondissement of the department.

Verdun is the biggest city in Meuse, although the capital ...

(where they were instrumental in recapturing a fort) to the Armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the La ...

.British Indian Army

The British Indian Army, commonly referred to as the Indian Army, was the main military of the British Raj before its dissolution in 1947. It was responsible for the defence of the British Indian Empire, including the princely states, which co ...

, including its elite Gurkha regiments is well known in this role, but the Senegalese

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 ...

and other African regiments of France demonstrate a similar pattern from Africa. Based on a variety of contemporary accounts, the performance of many African units was excellent, and both their German enemies and American allies accord them respect in a wide range of commentary, particularly fighting units from Morocco and regiments of ''Tirailleurs Senegalais'' from France's ''Armee coloniale.'' One French commander, commander of the 58th Regiment on the Western Front favored the employment of blacks as shock troops to save white lives: ''"finally and above all superb attack troops permitting the saving of the lives of whites, who behind them exploit their success and organize the positions they conquer."''

The impact of the European war was substantial in Senegal and other French African colonies. Many of the soldiers had volunteered, but the French also resorted to extensive conscription in its territories. Many of the African soldiers found army life in Europe comparatively more egalitarian than civilian life under the colonial regimes of their homelands. The mixing of African troops with troops and civilians from other races however often made colonial regimes nervous. In 1918 for example, South Africa, forced to earlier deploy armed Africans to cover manpower shortages, removed its black troops from France, because "blacks in the French front were contaminated with foreign notions about race relations and other social grievances." The French employed a number of high-ranking black soldiers, such as Sosthene Mortenol, Commander of the Air Defenses of Paris. The exigencies and shared dangers of war also seemed to have created, in measure, more mutual understanding and freer communication between Africans and Europeans, although this did not translate immediately into a more just order in their homeland territories. Ironically, the last troops to surrender in World War I were the black soldiers fighting for Germany in East Africa.

The impact of the European war was substantial in Senegal and other French African colonies. Many of the soldiers had volunteered, but the French also resorted to extensive conscription in its territories. Many of the African soldiers found army life in Europe comparatively more egalitarian than civilian life under the colonial regimes of their homelands. The mixing of African troops with troops and civilians from other races however often made colonial regimes nervous. In 1918 for example, South Africa, forced to earlier deploy armed Africans to cover manpower shortages, removed its black troops from France, because "blacks in the French front were contaminated with foreign notions about race relations and other social grievances." The French employed a number of high-ranking black soldiers, such as Sosthene Mortenol, Commander of the Air Defenses of Paris. The exigencies and shared dangers of war also seemed to have created, in measure, more mutual understanding and freer communication between Africans and Europeans, although this did not translate immediately into a more just order in their homeland territories. Ironically, the last troops to surrender in World War I were the black soldiers fighting for Germany in East Africa.South African Native Labour Corps

The South African Native Labour Corps (SANLC) was a force of workers formed in 1916 in response to a British request for workers at French ports. About 25,000 South Africans joined the Corps. The SANLC was utilized in various menial noncombat tas ...

(SANLC), met a sudden end in a 1917 maritime incident, that sparked sympathy throughout South Africa. Their transport, the SS Mendi

SS ''Mendi'' was a British Ocean liner, passenger steamship that was built in 1905 and, as a troopship, sank after collision with great loss of life in 1917.

Alexander Stephen and Sons of Linthouse in Glasgow, Scotland launched her on 18 June ...

was struck by another ship, the Darro, which was sailing without warning lights or signals, and made no attempt to pick up the survivors. Their chaplain, Reverend Isaac Dyobha, is reported to have rallied the doomed troops on deck for one final muster, referencing old warrior traditions as the waves closed in:

The Second Italian-Ethiopian War: 1935–36

The Italo-Ethiopian War (1935–36), saw Ethiopia's defeat by the Italian armies of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

. Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

(Abyssinia), which Italy had unsuccessfully tried to conquer in the 1890s, was in 1934 one of the few independent states in a European-dominated Africa. A border incident between Ethiopia and Italian Somaliland that December gave Benito Mussolini an excuse to intervene. Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie I

Haile Selassie I ( gez, ቀዳማዊ ኀይለ ሥላሴ, Qädamawi Häylä Səllasé, ; born Tafari Makonnen; 23 July 189227 August 1975) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. He rose to power as Regent Plenipotentiary of Ethiopia ('' ...

pulled all forces back from the border so as not to give the ''Duce'' any reason for aggression, but to no avail. Rejecting all arbitration offers, the Italians invaded Ethiopia on October 3, 1935. The Ethiopians were poorly armed with antiquated artillery, obsolete firearms, little armor, and some 20 outmoded planes. The Italians had over 200,000 troops in place, well equipped with modern arms for air and ground fighting.

Under Generals Rodolfo Graziani

Rodolfo Graziani, 1st Marquis of Neghelli (; 11 August 1882 – 11 January 1955), was a prominent Italian military officer in the Kingdom of Italy's '' Regio Esercito'' ("Royal Army"), primarily noted for his campaigns in Africa before and durin ...

and Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino (, ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regime ...

, the invading forces steadily pushed back the ill-armed and poorly trained Ethiopian army, winning a major victory near Lake Ascianghi (Ashangi) on April 9, 1936, and taking the capital, Addis Ababa

Addis Ababa (; am, አዲስ አበባ, , new flower ; also known as , lit. "natural spring" in Oromo), is the capital and largest city of Ethiopia. It is also served as major administrative center of the Oromia Region. In the 2007 census, t ...

, on May 5. Italian operations included the use of hundreds of tons of mustard gas, banned previously by the Geneva Convention.[Barker, pp. 2–189] The nation's leader, Emperor Haile Selassie, went into exile. In Rome, Mussolini proclaimed Italy's king Victor Emmanuel III

The name Victor or Viktor may refer to:

* Victor (name), including a list of people with the given name, mononym, or surname

Arts and entertainment

Film

* ''Victor'' (1951 film), a French drama film

* ''Victor'' (1993 film), a French shor ...

emperor of Ethiopia and appointed Badoglio to rule as viceroy. In response to Ethiopian appeals, the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

had condemned the Italian invasion in 1935 and voted to impose economic sanctions on the aggressor. The sanctions remained ineffective because of general lack of support, and because they excluded key war-making material- iron, coal, steel and most critically, oil. Strangely, aluminum, a metal that Italy had in plenty, and even exported, was on the list of sanctions that supposedly punished Italy. Although Mussolini's aggression was viewed with disfavour by the British, the other major powers had no real interest in opposing him. One historian notes that Britain could have starved the Italian war machine to a halt simply by closing the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

to the Duce

( , ) is an Italian title, derived from the Latin word 'leader', and a cognate of ''duke''. National Fascist Party leader Benito Mussolini was identified by Fascists as ('The Leader') of the movement since the birth of the in 1919. In 1925 ...

, but while issuing public statements condemning Italy, the British government took no real action.[W. Manchester, 1988. Winston Spencer Churchill: The Last Lion – Alone, Little Brown and Co: pp. 160–178] During the invasion, senior British and French officials drafted the Hoare-Laval pact which would partition the country, handing three-fifths of Ethiopia to the Italians. Press leaks created public outrage that canceled the pact. Less than a year after the Italian invasion, the League voted to remove sanctions against Italy.

The war ultimately gave substance to Italian imperialist claims, and contributed to international tensions between the fascist states and the Western democracies. It also sounded the death knell of the League of Nations as a credible institution according to some historians.[ These outcomes were to eventually culminate in World War II.]

World War II

Numerous Africans participated in World War II with black troops from France's colonial domains making up the bulk of the non-Europeans. Senegalese (sometimes a generic name for black troops from French colonies) put up a stiff fighting resistance against the Nazis during the great German Blitzkrieg into France. These, African troops were also to form a large part of the

Numerous Africans participated in World War II with black troops from France's colonial domains making up the bulk of the non-Europeans. Senegalese (sometimes a generic name for black troops from French colonies) put up a stiff fighting resistance against the Nazis during the great German Blitzkrieg into France. These, African troops were also to form a large part of the Free French Forces

__NOTOC__

The French Liberation Army (french: Armée française de la Libération or AFL) was the reunified French Army that arose from the merging of the Armée d'Afrique with the prior Free French Forces (french: Forces françaises libres, l ...

that maintained French resistance under Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

, outside the continent. In Africa, Felix Eboue, a black colonial administrator, was instrumental in rallying the territory of Chad for the Free French, adding thousands of fighting troops and masses of equipment to de Gaulle's cause. Other colonial formations were made up of troops from north Africa. As the Germans were beaten back, African troops made up the bulk of the initial forces that participated in the liberation of France during 1944, including supporting the French crossing of the Rhine.

The British colonies mostly deployed African troops in both Africa and Asia. Thousands of white South Africans and Rhodesians saw service in the Middle East and the Mediterranean, while black soldiers were assigned to both logistics and support formations. Some black regiments however did see combat, such as the King's African Rifles

The King's African Rifles (KAR) was a multi-battalion British colonial regiment raised from Britain's various possessions in East Africa from 1902 until independence in the 1960s. It performed both military and internal security functions withi ...

in the conquest of Madagascar from Vichy France

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...

in 1942, and the thousands of men of two West African divisions that fought with the British 14th Army against the Japanese in Burma.

Destabilizing effects of WWII among colonial soldiers

World War II was to have a profound effect on attitudes and developments in the African colonies. Dissatisfaction at inequities under colonial administration developed and had significant effects as the de-colonization/liberation era approached. As various colonial reports note:

:"Most of the thousands of Africans who became soldiers had never been out of their native lands. On active service, despite the dangers and hardships, they were well fed and clothed, and comparatively well paid. Many of them learned to read newspapers listen to wireless bulletins and to take an interest in world affairs. They learned to see their own countries in perspective, from the outside. On their return home, many of them became dissatisfied with conditions which were not so attractive as army life in countries more developed than their own... Such Africans, by reason of their contacts with other peoples, including Europeans, had developed a political and national consciousness. The fact that they were disappointed at conditions on their return, either from specious promises made before demobilization or a general expectancy of a golden age for heroes, made them the natural focal point for any general movement against authority."

More brutal treatment of black troops

Some WWII historians hold that black troops in France during the Western Campaign of 1940 were singled out for more brutal treatment by Nazi forces, even after making allowances for victor's anger at the steadfast resistance of the Negro units, who, as some German reports noted, ''"fought tenaciously, the blacks especially used every resource to the bitter end, defended every house.. to overcome the last Senegalese we had to kill them one by one."``

:"Blitzkrieg’s real victor in 1940 was National Socialism. Hitler celebrated the successes of May and June in Nazi terms: as a triumph of will, informed by a consciousness of martial superiority that in turn depended on the racial superiority evoked and refined by the Third Reich. In that context, blitzkrieg played a central, arguably essential role in the "exterminatory warfare” that was Nazi Germany’s true contribution to modern war making. Some forewarning was given by the treatment of the West African troops the French deployed in large numbers during the campaign’s second half. The atrocities had historical roots: fear and resentment generated by French use of African "savages” in 1870 and 1914-18... After all allowances are made there is nevertheless no question that German soldiers, including men from the mobile divisions, disproportionately refused quarter to black combatants, disproportionately singled out black prisoners for brutal treatment including large-scale executions in non-combat situations, and justified themselves on racial grounds." (Dennis Showalter - Hitler's Panzers_ The Lightning Attacks that Revolutionized Warfare)

While the post-surrender killings were not ordered as part of official Nazi regime policy, archival documents indicate that the German army massacred several thousand black POWs belonging to units drafted in France's West African colonies, amid the background of a long-running propaganda campaign identifying African as sub-human racial enemies. Some researchers hold that the massacres represent a significant link in the Nazis' progressive racial radicalization of the war. While white British and French POWs were generally treated according to the Geneva Convention, not so the blacks, who were separated out from whites, North Africans and other colonial soldiers for special abuse. Massacres of the black POWs occurred in several different places, with some killings of a hundred at a time. Massacres did not just take place with POWs, but with wounded Africans on the battlefield, such as after African troops had recaptured Aubigny in a counterattack, but were later driven out. Some French reports claim an "indescribable rage" of German troops when they fought the black units, with no quarter given, compared to the white, a pattern contributing to far higher casualty rates among the Negro units than other French forces. Such indicators of racialization began with the casual killing of captured Polish and African "Untermensch

''Untermensch'' (, ; plural: ''Untermenschen'') is a Nazi term for non- Aryan "inferior people" who were often referred to as "the masses from the East", that is Jews, Roma, and Slavs (mainly ethnic Poles, Serbs, and later also Russians). The ...

" in 1939 and 1940, and continued into the deliberate mass murder of millions of Soviet POWs after 1941, which was sanctioned as state policy.

Decolonization

Northern Africa

*Algerian War

The Algerian War, also known as the Algerian Revolution or the Algerian War of Independence,( ar, الثورة الجزائرية '; '' ber, Tagrawla Tadzayrit''; french: Guerre d'Algérie or ') and sometimes in Algeria as the War of 1 November ...

*Perejil Island crisis

The Perejil Island crisis (; ) was a bloodless armed conflict between Spain and Morocco that took place on 11–18 July 2002. The incident took place over the small, uninhabited Perejil Island, when a squad of the Royal Moroccan Navy occupied it. ...

Eastern Africa

*Mau Mau Uprising

The Mau Mau rebellion (1952–1960), also known as the Mau Mau uprising, Mau Mau revolt or Kenya Emergency, was a war in the British Kenya Colony (1920–1963) between the Kenya Land and Freedom Army (KLFA), also known as the ''Mau Mau'', an ...

*Eritrean War of Independence

The Eritrean War of Independence was a war for independence which Eritrean independence fighters waged against successive Ethiopian governments from 1 September 1961 to 24 May 1991.

Eritrea was an Italian colony from the 1880s until the d ...

Western Africa

*Green March

The Green March was a strategic mass demonstration in November 1975, coordinated by the Moroccan government, to force Spain to hand over the disputed, autonomous semi-metropolitan province of Spanish Sahara to Morocco. At that time, the Spani ...

*Guinea-Bissau War of Independence

The Guinea-Bissau War of Independence (), or the Bissau-Guinean War of Independence, was an armed independence conflict that took place in Portuguese Guinea from 1963 to 1974. It was fought between Portugal and the African Party for the Independ ...

Central Africa

*Congo Crisis

The Congo Crisis (french: Crise congolaise, link=no) was a period of political upheaval and conflict between 1960 and 1965 in the Republic of the Congo (today the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The crisis began almost immediately after ...

Warfare in Southern Africa

*

*Angolan War of Independence

The Angolan War of Independence (; 1961–1974), called in Angola the ("Armed Struggle of National Liberation"), began as an uprising against forced cultivation of cotton, and it became a multi-faction struggle for the control of Portugal ...

*Mozambican War of Independence

The Mozambican War of Independence ( pt, Guerra da Independência de Moçambique, 'War of Independence of Mozambique') was an armed conflict between the guerrilla forces of the Mozambique Liberation Front or FRELIMO () and Portugal. The wa ...

*Rhodesian Bush War

The Rhodesian Bush War, also called the Second as well as the Zimbabwe War of Liberation, was a civil conflict from July 1964 to December 1979 in the unrecognised country of Rhodesia (later Zimbabwe-Rhodesia).

The conflict pitted three for ...

*South African Border War

The South African Border War, also known as the Namibian War of Independence, and sometimes denoted in South Africa as the Angolan Bush War, was a largely asymmetric conflict that occurred in Namibia (then South West Africa), Zambia, and Angol ...

*Malagasy Uprising

The Malagasy Uprising (french: Insurrection malgache; mg, Tolom-bahoaka tamin' ny 1947) was a Malagasy nationalist rebellion against French colonial rule in Madagascar, lasting from March 1947 to February 1949. Starting in late 1945, Madagasca ...

Coups and counter-coups

1952

:* Egyptian Revolution in 1952.

1960

:* ''Force Publique'' mutiny in the Congo.

:* Katanga secedes from the Congo.

:*South Kasai

South Kasai (french: Sud-Kasaï) was an List of historical unrecognized states and dependencies, unrecognised Secession, secessionist state within the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville), Republic of the Congo (the modern-day Democratic Republi ...

secedes from the Congo.

1961

:* Overthrow and arrest of Patrice Lumumba by Mobutu Sese Seko

Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga (; born Joseph-Désiré Mobutu; 14 October 1930 – 7 September 1997) was a Congolese politician and military officer who was the president of Zaire from 1965 to 1997 (known as the Democratic Republic o ...

.

1963

:*Military coup in Togo

Togo (), officially the Togolese Republic (french: République togolaise), is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Ghana to the west, Benin to the east and Burkina Faso to the north. It extends south to the Gulf of Guinea, where its c ...

.

1964

:*Simba Rebellion

The Simba rebellion, also known as the Orientale revolt, was a regional uprising which took place in the Democratic Republic of the Congo between 1963 and 1965 in the wider context of the Congo Crisis and the Cold War. The rebellion, located in t ...

in the Congo.

1965

:*Mobutu Sese Seko

Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga (; born Joseph-Désiré Mobutu; 14 October 1930 – 7 September 1997) was a Congolese politician and military officer who was the president of Zaire from 1965 to 1997 (known as the Democratic Republic o ...

launches a successful second coup in the Congo.

:*Houari Boumédienne Houari is a given name and surname. It may refer to:

Persons Given name

*Houari Boumédiène, also transcribed Boumediene, Boumedienne etc. (1932–1978), served as Chairman of the Revolutionary Council of Algeria from 19 June 1965 until 12 Decembe ...

seizes power in Algeria.

1966

:*First Kisangani Mutiny in the Congo.

:*Jean-Bédel Bokassa

Jean-Bédel Bokassa (; 22 February 1921 – 3 November 1996), also known as Bokassa I, was a Central African political and military leader who served as the second president of the Central African Republic (CAR) and as the emperor of its s ...

stages the a coup in the Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR; ; , RCA; , or , ) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to the north, Sudan to the northeast, South Sudan to the southeast, the DR Congo to the south, the Republic of th ...

.

1967

:*Second Kisangani Mutiny in the Congo.

:*Military officers in Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

attempt an unsuccessful coup d'etat (code named '' Operation Guitar Boy'') that results in the assassination of Lieutenant General Emmanuel Kwasi Kotoka

Lieutenant-General Emmanuel Kwasi Kotoka Born (26 September 1926 – 17 April 1967) was a Ghanaian military officer who was a member of the ruling National Liberation Council which came to power in Ghana in a military coup d'état on 24 February ...

.

:*Yakubu Gowon

Yakubu Dan-Yumma 'Jack' Gowon (born 19 October 1934) is a retired Nigerian Army general and military leader. As Head of State of Nigeria, Gowon presided over a controversial Nigerian Civil War and delivered the famous "no victor, no vanquish ...

comes to power through a coup in Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

.

1969

:*Muammar al-Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi, . Due to the lack of standardization of transcribing written and regionally pronounced Arabic, Gaddafi's name has been romanized in various ways. A 1986 column by ''The Straight Dope'' lists 32 spellin ...

, a Lieutenant Colonel in the Libyan army, stages a coup to oust king Idris of Libya

Muhammad Idris bin Muhammad al-Mahdi as-Senussi ( ar, إدريس, Idrīs; 13 March 1890 – 25 May 1983) was a Libyan political and religious leader who was Kingdom of Libya, King of Libya from 24 December 1951 until his overthrow on 1 September ...

and installs himself as "Leader and Guide of the Revolution."

:*Military coup in Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constituti ...

:*Military coup in the Sudan.

1970s – warfare in southern Africa

1971

:*Idi Amin

Idi Amin Dada Oumee (, ; 16 August 2003) was a Ugandan military officer and politician who served as the third president of Uganda from 1971 to 1979. He ruled as a military dictator and is considered one of the most brutal despots in modern w ...

seizes power through a coup in Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territor ...

.

1972

:*Ignatius Kutu Acheampong

Ignatius Kutu Acheampong ( ; (23 September 1931 – 16 June 1979) was the military head of state of Ghana from 13 January 1972 to 5 July 1978, when he was deposed in a palace coup. He was executed by firing squad on 16 June 1979.

Early life and ...

overthrows the democratically elected government of Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

.

1974

:*The Derg

The Derg (also spelled Dergue; , ), officially the Provisional Military Administrative Council (PMAC), was the military junta that ruled Ethiopia, then including present-day Eritrea, from 1974 to 1987, when the military leadership formally " c ...

, a communist military junta

Junta may refer to:

Government and military

* Junta (governing body) (from Spanish), the name of various historical and current governments and governing institutions, including civil ones

** Military junta, one form of junta, government led by ...

, seizes power in Ethiopia.

1975

:*French mercenary Bob Denard

Robert Denard (born Gilbert Bourgeaud; 7 April 1929 – 13 October 2007) was a French soldier of fortune and mercenary. He served as the Military Leader of The Comoros twice with him first serving from 13 May 1978 to 15 December 1989 and again ...

deposes Ahmed Abdallah of the Comoros

The Comoros,, ' officially the Union of the Comoros,; ar, الاتحاد القمري ' is an independent country made up of three islands in southeastern Africa, located at the northern end of the Mozambique Channel in the Indian Ocean. It ...

.

:*Murtala Mohammed

Murtala Ramat Muhammad (8 November 1938 – 13 February 1976) was a Nigerian general who led the 1966 Nigerian counter-coup in overthrowing the Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi military regime and featured prominently during the Nigerian Civil War ...

seizes power from Yakubu Gowon

Yakubu Dan-Yumma 'Jack' Gowon (born 19 October 1934) is a retired Nigerian Army general and military leader. As Head of State of Nigeria, Gowon presided over a controversial Nigerian Civil War and delivered the famous "no victor, no vanquish ...

in Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

.

:*A coup in Chad overthrows the government of François Tombalbaye

François Tombalbaye ( ar, فرنسوا تومبالباي '; 15 June 1918 – 13 April 1975), also known as N'Garta Tombalbaye, was a Chadian politician who served as the first President of Chad from the country's independence in 1960 until ...

.

1976

:*A failed coup in Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

results in the death of Murtala Mohammed

Murtala Ramat Muhammad (8 November 1938 – 13 February 1976) was a Nigerian general who led the 1966 Nigerian counter-coup in overthrowing the Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi military regime and featured prominently during the Nigerian Civil War ...

and the rise to power of Olusegun Obasanjo

Chief Olusegun Matthew Okikiola Ogunboye Aremu Obasanjo, , ( ; yo, Olúṣẹ́gun Ọbásanjọ́ ; born 5 March 1937) is a Nigerian political and military leader who served as Nigeria's head of state from 1976 to 1979 and later as its pres ...

.

1979

:*Flight Lieutenant

1979

:*Flight Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings

Jerry John Rawlings (22 June 194712 November 2020) was a Ghanaian military officer and politician who led the country for a brief period in 1979, and then from 1981 to 2001. He led a military junta until 1992, and then served two terms as the de ...

seizes power in Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

.

1980

:*Coup by Master Sergeant Samuel Doe

Samuel Kanyon Doe (6 May 1951 – 9 September 1990) was a Liberian politician who served as the 21st president of Liberia from 1980 to 1990. Doe ruled Liberia as Chairman of the People's Redemption Council (PRC) from 1980 to 1984 and then a ...

in Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean ...

.

:*Coup in Guinea Bissau

Guinea-Bissau ( ; pt, Guiné-Bissau; ff, italic=no, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫 𞤄𞤭𞤧𞤢𞥄𞤱𞤮, Gine-Bisaawo, script=Adlm; Mandinka: ''Gine-Bisawo''), officially the Republic of Guinea-Bissau ( pt, República da Guiné-Bissau, links=no ) ...

.

1981

:*Kukoi Sanyang

Kukoi Samba Sanyang (1952 – 18 June 2013) was a Gambian politician and leader of the 1981 Gambian coup d'état attempt, unsuccessful 1981 coup d'état against the government of Dawda Jawara.

Early Years

Sanyang was born in the village of Wassadu ...

leads a failed coup attempt in The Gambia

The Gambia,, ff, Gammbi, ar, غامبيا officially the Republic of The Gambia, is a country in West Africa. It is the smallest country within mainland AfricaHoare, Ben. (2002) ''The Kingfisher A-Z Encyclopedia'', Kingfisher Publicatio ...

.

:*Jerry John Rawlings

Jerry John Rawlings (22 June 194712 November 2020) was a Ghanaian military officer and politician who led the country for a brief period in 1979, and then from 1981 to 2001. He led a military junta until 1992, and then served two terms as the de ...

leads a second coup in Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

.

:*Failed coup attempt by mercenary

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any o ...

Mike Hoare

Thomas Michael Hoare (17 March 1919 – 2 February 2020), known as Mad Mike Hoare, was a British mercenary soldier who operated during the Simba rebellion, and attempted to conduct a coup d'état in the Seychelles.

Early life and military car ...

in the Seychelles

Seychelles (, ; ), officially the Republic of Seychelles (french: link=no, République des Seychelles; Creole: ''La Repiblik Sesel''), is an archipelagic state consisting of 115 islands in the Indian Ocean. Its capital and largest city, V ...

.

:*The Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army

Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) was the military wing of the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU), a Marxist–Leninist political party in Rhodesia. It participated in the Rhodesian Bush War against white minority rule of Rhodes ...

launches the 1981 Entumbane Uprising

The 1981 Entumbane uprising, also known as the Battle of Bulawayo or Entumbane II, occurred between 8 and 12 February 1981 in and around Bulawayo, Zimbabwe amid political tensions in the newly independent state. Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary ...

.

1982

:*Members of the Kenyan Air Force

The Kenya Air Force (KAF) or sw, Jeshi la Wanahewa is the national aerial warfare service branch of the Republic of Kenya.

The main airbase operating fighters is Laikipia Air Base in Nanyuki, while Moi Air Base

Moi Air Base, formerly know ...

lead a failed coup attempt in that country.

1983

:*Military coup in Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

. Second republic president Shagari overthrown; Muhammadu Buhari

Muhammadu Buhari (born 17 December 1942) is a Nigerian politician and current president of Nigeria since 2015.

Buhari is a retired Nigerian Army major general who served as the country's military head of state from 31 December 1983 to 27 Au ...

takes power.

1984

:* Cameroonian Palace Guard Revolt

:*Maaouya Ould Sid'Ahmed Taya

Maaouya Ould Sid'Ahmed Taya ( ar, معاوية ولد سيد أحمد الطايع, Ma‘āwiyah wuld Sīdi Aḥmad aṭ-Ṭāya‘ / Mu'awiya walad Sayyidi Ahmad Taya; born 28 November 1941) is a Mauritanian military officer who served as the P ...

raise to power in Mauritania

Mauritania (; ar, موريتانيا, ', french: Mauritanie; Berber: ''Agawej'' or ''Cengit''; Pulaar: ''Moritani''; Wolof: ''Gànnaar''; Soninke:), officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania ( ar, الجمهورية الإسلامية ...

after a coup that overthrow the president Mohamed Khouna Ould Haidalla

Ret. Col. Mohamed Khouna Ould Haidallah ( ar, محمد خونا ولد هيداله ''Muḥammad Khouna Wald Haidallah'') (born 1940) was the head of state of Mauritania (Chairman of the Military Committee for National Salvation, CMSN) from 4 Janu ...

.

1985

:*Military coup in Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territor ...

led by Bazilio Olara-Okello

Bazilio Olara-Okello (1929 – 9 January 1990) was a Ugandan Officer (armed forces), military officer and one of the commanders of the Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA) that together with the Tanzania People's Defence Force, Tanzanian a ...

and Tito Okello

Tito Lutwa Okello (1914 – 3 June 1996) was a Ugandan military officer and politician. He was the eighth president of Uganda from 29 July 1985 until 26 January 1986.

Background

Tito Okello was born into an ethnic Acholi family in circa 1914 ...

.

:*Military coup in Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

. Ibrahim Babangida

Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida (born 17 August, 1941) is a retired Nigerian Army general and politician. He served as military president of Nigeria from 1985 until his resignation in 1993. He rose through the ranks to serve from 1984 to 1985 as Ch ...

replaces Muhammadu Buhari

Muhammadu Buhari (born 17 December 1942) is a Nigerian politician and current president of Nigeria since 2015.

Buhari is a retired Nigerian Army major general who served as the country's military head of state from 31 December 1983 to 27 Au ...

.

1987

:*Bloodless coup in Tunisia led by Prime Minister General Zine El Abidine Ben Ali

Zine El Abidine Ben Ali ( ar, زين العابدين بن علي, translit=Zayn al-'Ābidīn bin 'Alī; 3 September 1936 – 19 September 2019), commonly known as Ben Ali ( ar, بن علي) or Ezzine ( ar, الزين), was a Tunisian politician ...

overthrows President Habib Bourguiba

Habib Bourguiba (; ar, الحبيب بورقيبة, al-Ḥabīb Būrqībah; 3 August 19036 April 2000) was a Tunisian lawyer, nationalist leader and statesman who led the country from 1956 to 1957 as the prime minister of the Kingdom of T ...

.

1990

:*Samuel Doe

Samuel Kanyon Doe (6 May 1951 – 9 September 1990) was a Liberian politician who served as the 21st president of Liberia from 1980 to 1990. Doe ruled Liberia as Chairman of the People's Redemption Council (PRC) from 1980 to 1984 and then a ...

is captured and killed by INPFL rebels in Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean ...

led by Prince Johnson

Prince Yormie Johnson"Prince" is a common given name for men in Liberia, rather than a royal title. (born 6 July 1952) is a Liberian politician and the current Senior Senator from Nimba County. A former rebel leader, Johnson played a prominent ...

.

1992

:*Military coup in Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

cancels elections and forces President to resign.

1994

:*Military coup in The Gambia

The Gambia,, ff, Gammbi, ar, غامبيا officially the Republic of The Gambia, is a country in West Africa. It is the smallest country within mainland AfricaHoare, Ben. (2002) ''The Kingfisher A-Z Encyclopedia'', Kingfisher Publicatio ...

.

1999

:*Military coup in Côte d'Ivoire

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire, officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital is Yamoussoukro, in the centre of the country, while its largest city and economic centre is ...

.

2003

:*Military coup in Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR; ; , RCA; , or , ) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to the north, Sudan to the northeast, South Sudan to the southeast, the DR Congo to the south, the Republic of th ...

.

:*Attempted coup in Mauritania

Mauritania (; ar, موريتانيا, ', french: Mauritanie; Berber: ''Agawej'' or ''Cengit''; Pulaar: ''Moritani''; Wolof: ''Gànnaar''; Soninke:), officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania ( ar, الجمهورية الإسلامية ...

.

:*Military coup in São Tomé and Príncipe

São Tomé and Príncipe (; pt, São Tomé e Príncipe (); English: " Saint Thomas and Prince"), officially the Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe ( pt, República Democrática de São Tomé e Príncipe), is a Portuguese-speaking i ...

.

:*Military coup in Guinea-Bissau

Guinea-Bissau ( ; pt, Guiné-Bissau; ff, italic=no, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫 𞤄𞤭𞤧𞤢𞥄𞤱𞤮, Gine-Bisaawo, script=Adlm; Mandinka: ''Gine-Bisawo''), officially the Republic of Guinea-Bissau ( pt, República da Guiné-Bissau, links=no ) ...

.

2004

:*Attempted coup in the

2004

:*Attempted coup in the Democratic Republic of Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

.

:* Failed coup d'état in Chad against Heads of State of Chad, President Idriss Déby.

:*Second attempted coup in the Democratic Republic of Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

(June).

:*2004 Equatorial Guinea coup d'état attempt, Attempted coup in Equatorial Guinea by South African mercenaries Nick du Toit and Simon Mann.

2005

:*Coup in Togo

Togo (), officially the Togolese Republic (french: République togolaise), is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Ghana to the west, Benin to the east and Burkina Faso to the north. It extends south to the Gulf of Guinea, where its c ...

legalized by parliamentary vote but unrecognized by international community.

:*A 2005 Mauritanian coup d'état, military coup in Mauritania

Mauritania (; ar, موريتانيا, ', french: Mauritanie; Berber: ''Agawej'' or ''Cengit''; Pulaar: ''Moritani''; Wolof: ''Gànnaar''; Soninke:), officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania ( ar, الجمهورية الإسلامية ...

overthrows Heads of state of Mauritania, President Maaouya Ould Sid'Ahmed Taya

Maaouya Ould Sid'Ahmed Taya ( ar, معاوية ولد سيد أحمد الطايع, Ma‘āwiyah wuld Sīdi Aḥmad aṭ-Ṭāya‘ / Mu'awiya walad Sayyidi Ahmad Taya; born 28 November 1941) is a Mauritanian military officer who served as the P ...

. A new government is set up by a group of military officers headed by Ely Ould Mohamed Vall. The group formed the Military Council for Justice and Democracy to act as the governing council of the country.

2006

:*The United Front for Democratic Change allegedly attempted to instigate a military 2006 Chadian coup d'état attempt, coup in Chad to overthrow Heads of state of Chad, President Idriss Déby.

:*The Military of Madagascar, Malagasy Popular Armed Forces allegedly attempt a 2006 Malagasy coup d'état attempt, military coup in Madagascar against List of Presidents of Madagascar, President Marc Ravalomanana.

:*The military of Côte d'Ivoire claims to foil a coup attempt targeting President of Côte d'Ivoire, President Laurent Gbagbo.

2008

:*A 2008 Mauritanian coup d'état, military coup in Mauritania involving the seizure of the Sidi Ould Cheikh Abdallahi, president, Yahya Ould Ahmed El Waghef, prime minister, and interior minister after the sacking of several military officials and a political crisis in which 48 MPs walked off the job and a vote of no confidence in cabinet.

2013

:*The 2013 Egyptian coup d'etat overthrew president Mohammed Morsi.

The post-Cold War era

Rise of asymmetric warfare and the "technicals" generation

With the exception of a handful of nations such as Egypt and South Africa, most modern defense forces in Africa are comparatively small and lightly armed, although many have a limited number of heavy weapons such as older main battle tanks. The post-colonial era however has also seen the emergence of numerous non-state military forces, such as terrorists, rebel guerilla organizations, ethnic gangs, and local warlords with various political platforms. Such non-state actors add to the instability of the African situation, and the growth of ''asymmetric'' warfare and terrorism makes the military challenges in Africa more acute.Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constituti ...

. Local militiamen downed two Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawks with RPG-7s and killed 18 elite United States Army Rangers, Army Rangers. Although Somali losses in the encounter were staggering and the Rangers carried out their assigned objectives, the affair prompted the United States to withdraw, ultimately leaving the field to the Somali defenders. Another tactically significant demonstration of today's African mobility was displayed in the Toyota War, which pitted an under-equipped and understrength Chadian army against 20,000 Libyan troops backed by 300 T-54/55 and T-62 tanks, thousands of armored personnel carriers, and Sukhoi Su-10 bomber aircraft. As one military analyst notes of the Chadian performance:

:'In contrast, Chadian forces possessed nothing more sophisticated than a handful of older Western armored cars, and mostly relied on Toyota pick-up trucks mounting crew-served infantry weapons. The Chadians had no tanks, no APCs, no artillery, no air force, no infantry weapons heavier than the Milan antitank guided missile, and only the complicated and ineffectual Redeye shoulder-launched surface-to-air missile (SAM) for air defence, What's more, the Chadians did not operate their weaponry very well. Nevertheless, an army of as many as 20,000 Libyans was demolished by 10,000 Chadian regulars and 20,000 tribal militia during eight months of fighting."[Ken Pollack, Arabs at War: Military Effectiveness 1948–1991, University of Nebraska Press, p. 3]

Guerilla organizations, paramilitaries and other asymmetric elements also continue to make an important impact in local areas—threatening to overthrow local regimes as well as generating widespread misery and economic dislocation in various areas. Such patterns are not unique to Africa and are also seen in places such as the Balkans.

Major modern forces in Africa

Contrasting with the small scale, more fragmented pattern in many parts of the continent are the modern forces of such major powers as Egypt and South Africa. Well equipped for air and ground fighting, such regional powers represent a significant illustration of the growing capacities of Africa-based armies. The well-organized Canal Crossing of the Egyptians in the 1973 Yom Kippur War for example, is spoken of with respect by some Western military analysts and demonstrates the degree to which some continental forces have mastered modern technology.

However, detailed open-source evaluations of Egyptian military effectiveness, remain skeptical of any great capability leaps, arguing at length that the same problems that held the Egyptians back in 1956, 1967, and 1973 remain. The initial success at Suez for example, was comprehensively beaten back by the Israelis, first in the Sinai and then in the Battle of the Chinese Farm, leading to the cutting off of the Egyptian Third Army. Compared to previous Egyptian performances however, the Suez crossing represented a step forward, and showed an increasing sophistication on the battlefield.

Further south, Somalia in July 1977 initiated the Ogaden War with Barre's government trying to incorporate the predominantly Somali-inhabited Ogaden region in Ethiopia into a Pan-Somali Greater Somalia. The Somali national army invaded the Ogaden and was successful at first, capturing most of the territory. But the invasion reached an abrupt end with the Soviet Union's sudden shift of support to Ethiopia and was forced to retreat with almost the entire communist world siding with Ethiopia. Somalia's initial friendship with the Soviet Union and later partnership with the United States enabled it to build the fourth largest army in Africa.

Contrasting with the small scale, more fragmented pattern in many parts of the continent are the modern forces of such major powers as Egypt and South Africa. Well equipped for air and ground fighting, such regional powers represent a significant illustration of the growing capacities of Africa-based armies. The well-organized Canal Crossing of the Egyptians in the 1973 Yom Kippur War for example, is spoken of with respect by some Western military analysts and demonstrates the degree to which some continental forces have mastered modern technology.

However, detailed open-source evaluations of Egyptian military effectiveness, remain skeptical of any great capability leaps, arguing at length that the same problems that held the Egyptians back in 1956, 1967, and 1973 remain. The initial success at Suez for example, was comprehensively beaten back by the Israelis, first in the Sinai and then in the Battle of the Chinese Farm, leading to the cutting off of the Egyptian Third Army. Compared to previous Egyptian performances however, the Suez crossing represented a step forward, and showed an increasing sophistication on the battlefield.

Further south, Somalia in July 1977 initiated the Ogaden War with Barre's government trying to incorporate the predominantly Somali-inhabited Ogaden region in Ethiopia into a Pan-Somali Greater Somalia. The Somali national army invaded the Ogaden and was successful at first, capturing most of the territory. But the invasion reached an abrupt end with the Soviet Union's sudden shift of support to Ethiopia and was forced to retreat with almost the entire communist world siding with Ethiopia. Somalia's initial friendship with the Soviet Union and later partnership with the United States enabled it to build the fourth largest army in Africa.[Oliver Ramsbotham, Tom Woodhouse, ''Encyclopedia of international peacekeeping operations'', (ABC-CLIO: 1999), p.222.]

While some fighting forces such as South African National Defence Force, those maintained by South Africa have already been recognized for their professional competence and operational record, intermediate nations like Ethiopia also grow increasingly more sophisticated, adding to dynamic patterns of change and transformation illustrated from the earliest times on the continent, to the present.

21st century military challenges

The military challenge in Africa is huge in the post-Cold War era. It is a continent covering some 22% of the world's land area, has an estimated population of some 800 million, is governed by 53 different states, and is made up of hundreds of different ethnicities and languages. According to a 2007 Whitehall Report, (''The African Military in the 21st Century, Tswalu Dialogue''), some issues affecting African militaries in the 21st century include:

The military challenge in Africa is huge in the post-Cold War era. It is a continent covering some 22% of the world's land area, has an estimated population of some 800 million, is governed by 53 different states, and is made up of hundreds of different ethnicities and languages. According to a 2007 Whitehall Report, (''The African Military in the 21st Century, Tswalu Dialogue''), some issues affecting African militaries in the 21st century include:[The African Military in the 21st Century: Report of the 2007 Tswalu Dialogue](_blank)

: May 3–6, 2007, Whitehall Report Series, 2007

*The continued need to build military proficiency and effectiveness

*The threat of rebellions, coups and the need for stability

*Unrealistic expectations by the West about what Africa should be doing about continental defence and security issues

*The relevance of West Point or Sandhurst style training and thinking to the African context

*The weak and fragmented nature of many collective security type arrangements – such as the AU (African Union) – weak clones of the NATO concept

*The challenge of terrorism asymmetric warfare and how African forces shape themselves to meet them

*The danger of giving militaries a bigger role in nation building and development. In Africa such activity touches on political power.

*The appropriateness of international peacekeeping forces and bureaucracies in parts of Africa, with the mixed record of UN peacekeeping in the Congo or Rwanda raising doubts about their efficacy

Future of African military systems

Theme of modernization

Some writers argue that military activities in Africa after 1950 resemble somewhat the concept of a "frontiersman" – that is, warriors from numerous small tribes, clans, polities, and ethnicities seeking to expand their ''lebensraum'' – "living space" or control of economic resources, at the expense of some "other." Even the most powerful military below the Sahara, South Africa, it is argued, had its genesis in the notions of ''lebensraum'', and the struggle of warriors from tribes and ethnicities seeking land, resources and dominance against some defined outsider. The plethora of ethnic and tribal military conflicts in Africa after the colonial period- from Rwanda, to Somalia, to the Congo, to the apartheid state, is held to reflect this basic pattern. Others maintain that ethnic and tribal struggles, and wars over economic resources are common in European history, and military conflicts and development that these struggles aid or hinder can be seen as a reflection of the process of modernization.

Inspiration from the past in African military systems

Yet other writers call for a renewed study of the past as inspiration for future reforms. They maintain that there has been a decline in African military systems from their indigenous foundations of the pre-colonial era, and early post colonial phases. In these eras, it is argued, African military forces generally conducted themselves "with honor" but future decades were to see numerous horrors and infamy. Peoples like the Asante, Zulu etc. fought hard and sometimes viciously, but this was within the context of their cultural understanding, at their particular time and place. There were no mass campaigns of genocidal extermination against others. Encounters with such African military forces it is held, often generated the universal code of respect between opposing warriors who had seen combat- one fighting man to another. An example of this can be seen in British writings such as post-mortem accounts of enemy leadership at the Battle of Amoaful against the Ashanti:

:''The great Chief Amanquatia was among the killed. Admirable skill was shown in the position selected by Amanquatia, and the determination and generalship he displayed in the defence fully bore out his great reputation as an able tactician and gallant soldier."''

According to R. Edgerton, historian of many African conflicts:

:"These armed men – and sometimes women – fought for territorial expansion, tribute and slaves; they also defended their families, kinsmen and their societies at large with their cherished ways of life. And when they fought, they typically did so with honor, sparing the elderly, women, and children... When colonial powers invaded Africa, African soldiers fought them with death-defying courage, earning such respect as warriors that they were recruited into the colonial armies not simply to enforce colonial rule in Africa but to fight for the European homelands as well. The French were so impressed by African warriors that they used them in the trenches of the western front in World War I, and African soldiers bore the brunt of German panzer attacks in World War II.. where they made a vivid impression on the far better equipped Germans.."