1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Turkish invasion of Cyprus began on 20 July 1974 and progressed in two phases over the following month. Taking place upon a background of intercommunal violence between

British rule lasted until 1960 when the island was declared an independent state under the London-Zurich agreements. The agreement created a foundation for the Republic of Cyprus by the Turkish Cypriot and Greek Cypriot communities, although the republic was seen as a necessary compromise between the two reluctant communities.

The 1960 Constitution of the Cyprus Republic proved unworkable however, lasting only three years. Greek Cypriots wanted to end the separate Turkish Cypriot municipal councils permitted by the British in 1958, made subject to review under the 1960 agreements. For many Greek Cypriots these municipalities were the first stage on the way to the partition they feared. The Greek Cypriots wanted '' enosis'', integration with Greece, while Turkish Cypriots wanted '' taksim'', partition between Greece and Turkey.

Resentment also rose within the Greek Cypriot community because Turkish Cypriots had been given a larger share of governmental posts than the size of their population warranted. In accordance with the constitution 30% of civil service jobs were allocated to the Turkish community despite being only 18.3% of the population. Additionally, the position of vice president was reserved for the Turkish population, and both the president and vice president were given veto power over crucial issues.Borowiec, Andrew. Cyprus: A Troubled Island. Westport: Praeger. 2000. 47

British rule lasted until 1960 when the island was declared an independent state under the London-Zurich agreements. The agreement created a foundation for the Republic of Cyprus by the Turkish Cypriot and Greek Cypriot communities, although the republic was seen as a necessary compromise between the two reluctant communities.

The 1960 Constitution of the Cyprus Republic proved unworkable however, lasting only three years. Greek Cypriots wanted to end the separate Turkish Cypriot municipal councils permitted by the British in 1958, made subject to review under the 1960 agreements. For many Greek Cypriots these municipalities were the first stage on the way to the partition they feared. The Greek Cypriots wanted '' enosis'', integration with Greece, while Turkish Cypriots wanted '' taksim'', partition between Greece and Turkey.

Resentment also rose within the Greek Cypriot community because Turkish Cypriots had been given a larger share of governmental posts than the size of their population warranted. In accordance with the constitution 30% of civil service jobs were allocated to the Turkish community despite being only 18.3% of the population. Additionally, the position of vice president was reserved for the Turkish population, and both the president and vice president were given veto power over crucial issues.Borowiec, Andrew. Cyprus: A Troubled Island. Westport: Praeger. 2000. 47

, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 1991. The amendments would have involved the Turkish community giving up many of their protections as a minority, including adjusting ethnic quotas in the government and revoking the presidential and vice presidential veto power. These amendments were rejected by the Turkish side and the Turkish representation left the government, although there is some dispute over whether they left in protest or were forced out by the National Guard. The 1960 constitution fell apart and communal violence erupted on 21 December 1963, when two Turkish Cypriots were killed at an incident involving the Greek Cypriot police. Turkey, the UK and Greece, the guarantors of the

p.120

: "According to official records, 364 Turkish Cypriots and 174 Greek Cypriots were killed during the 1963–1964 crisis." destruction of 109 Turkish Cypriot or mixed villages and displacement of 25,000–30,000 Turkish Cypriots. The British '' Daily Telegraph'' later called it an "anti Turkish pogrom". Thereafter Turkey once again put forward the idea of partition. The intensified fighting especially around areas under the control of Turkish Cypriot militias, as well as the failure of the constitution were used as justification for a possible Turkish invasion. Turkey was on the brink of invading when

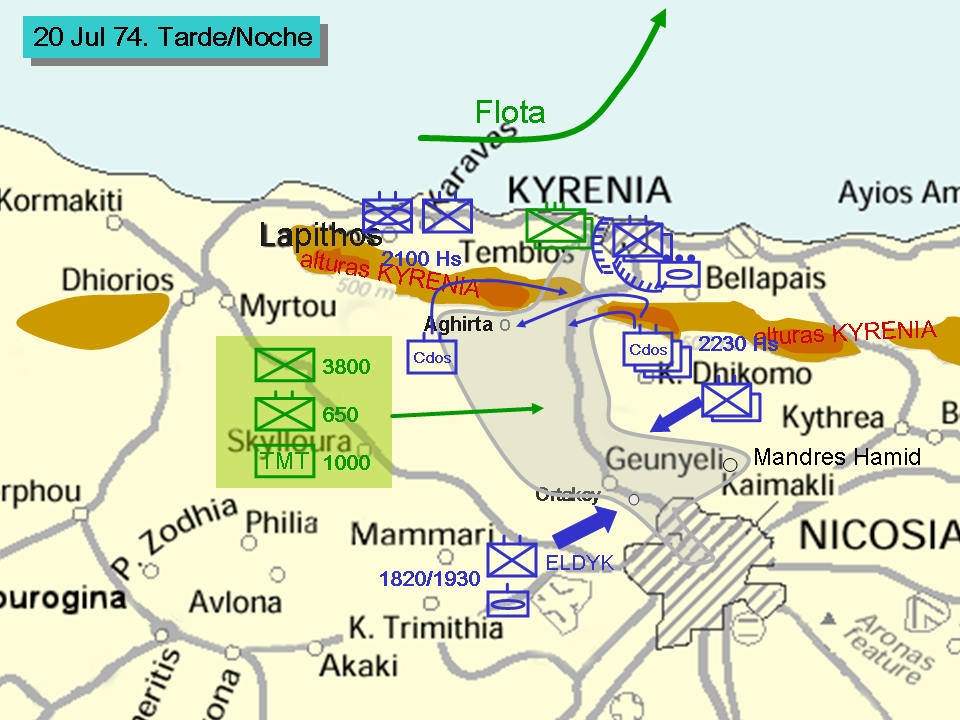

Turkey invaded Cyprus on Saturday, 20 July 1974. Heavily armed troops landed shortly before dawn at Kyrenia (Girne) on the northern coast meeting resistance from Greek and Greek Cypriot forces. Ankara said that it was invoking its right under the Treaty of Guarantee to protect the Turkish Cypriots and guarantee the independence of Cyprus.

By the time the UN Security Council was able to obtain a ceasefire on 22 July the Turkish forces were in command of a narrow path between Kyrenia and Nicosia, 3% of the territory of Cyprus,

which they succeeded in widening, violating the ceasefire demanded in Resolution 353.

On 20 July, the 10,000 inhabitants of the Turkish Cypriot enclave of

Turkey invaded Cyprus on Saturday, 20 July 1974. Heavily armed troops landed shortly before dawn at Kyrenia (Girne) on the northern coast meeting resistance from Greek and Greek Cypriot forces. Ankara said that it was invoking its right under the Treaty of Guarantee to protect the Turkish Cypriots and guarantee the independence of Cyprus.

By the time the UN Security Council was able to obtain a ceasefire on 22 July the Turkish forces were in command of a narrow path between Kyrenia and Nicosia, 3% of the territory of Cyprus,

which they succeeded in widening, violating the ceasefire demanded in Resolution 353.

On 20 July, the 10,000 inhabitants of the Turkish Cypriot enclave of

The Turkish Foreign Minister Turan Güneş had said to the Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit, "When I say 'Ayşe should go on vacation' ( Turkish: ''"Ayşe Tatile Çıksın"''), it will mean that our armed forces are ready to go into action. Even if the telephone line is tapped, that would rouse no suspicion." An hour and a half after the conference broke up, Turan Güneş called Ecevit and said the code phrase. On 14 August Turkey launched its "Second Peace Operation", which eventually resulted in the Turkish occupation of 37% of Cyprus. Turkish occupation reached as far south as the

The Turkish Foreign Minister Turan Güneş had said to the Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit, "When I say 'Ayşe should go on vacation' ( Turkish: ''"Ayşe Tatile Çıksın"''), it will mean that our armed forces are ready to go into action. Even if the telephone line is tapped, that would rouse no suspicion." An hour and a half after the conference broke up, Turan Güneş called Ecevit and said the code phrase. On 14 August Turkey launched its "Second Peace Operation", which eventually resulted in the Turkish occupation of 37% of Cyprus. Turkish occupation reached as far south as the

Turkey was found guilty by the European Commission of Human Rights for displacement of persons, deprivation of liberty, ill treatment, deprivation of life and deprivation of possessions.European Commission of Human Rights, "Report of the Commission to Applications 6780/74 and 6950/75", Council of Europe, 1976

Turkey was found guilty by the European Commission of Human Rights for displacement of persons, deprivation of liberty, ill treatment, deprivation of life and deprivation of possessions.European Commission of Human Rights, "Report of the Commission to Applications 6780/74 and 6950/75", Council of Europe, 1976

p. 160,161,162,163.Link from Internet Archive

/ref> The Turkish policy of violently forcing a third of the island's Greek population from their homes in the occupied North, preventing their return and settling Turks from mainland Turkey is considered an example of ethnic cleansing. In 1976 and again in 1983, the

p. 120,124.

Link from Internet Archive

/ref> The high rate of rape reportedly resulted in the temporary permission of abortion in Cyprus by the conservative

During the

During the

The road to Bellapais: the Turkish Cypriot exodus to northern Cyprus

'' (1982), Social Science Monographs, p. 185Paul Sant Cassia, ''Bodies of Evidence: Burial, Memory, and the Recovery of Missing Persons in Cyprus'', Berghahn Books, 2007,

p. 237

The

Massacre&f=false p. 61

The ''Washington Post'' covered another news of atrocity in which it is written that: "In a Greek raid on a small Turkish village near Limassol, 36 people out of a population of 200 were killed. The Greeks said that they had been given orders to kill the inhabitants of the Turkish villages before the Turkish forces arrived." In Limassol, upon the fall of the Turkish Cypriot enclave to the Cypriot National Guard, the Turkish Cypriot quarter was burned, women raped and children shot, according to Turkish Cypriot and Greek Cypriot eyewitness accounts. 1300 people were then led to a prison camp.

In 1989, the government of Cyprus took an American art dealer to court for the return of four rare 6th-century Byzantine

In 1989, the government of Cyprus took an American art dealer to court for the return of four rare 6th-century Byzantine

In 1983 the Turkish Cypriot assembly declared independence of the

In 1983 the Turkish Cypriot assembly declared independence of the

The United Nations Security Council decisions for the immediate unconditional withdrawal of all foreign troops from Cyprus soil and the safe return of the refugees to their homes have not been implemented by Turkey and the TRNC. Turkey and TRNC defend their position, stating that any such withdrawal would have led to a resumption of intercommunal fighting and killing.

In 1999, UNHCR halted its assistance activities for internally displaced persons in Cyprus.

Negotiations to find a solution to the Cyprus problem have been taking place on and off since 1964. Between 1974 and 2002, the Turkish Cypriot side was seen by the international community as the side refusing a balanced solution. Since 2002, the situation has been reversed according to US and UK officials, and the Greek Cypriot side rejected a plan which would have called for the dissolution of the Republic of Cyprus without guarantees that the Turkish occupation forces would be removed. The latest Annan Plan to reunify the island which was endorsed by the United States, United Kingdom, and Turkey was accepted by a referendum by Turkish Cypriots but overwhelmingly rejected in parallel referendum by Greek Cypriots, after the Greek Cypriot Leadership and

The United Nations Security Council decisions for the immediate unconditional withdrawal of all foreign troops from Cyprus soil and the safe return of the refugees to their homes have not been implemented by Turkey and the TRNC. Turkey and TRNC defend their position, stating that any such withdrawal would have led to a resumption of intercommunal fighting and killing.

In 1999, UNHCR halted its assistance activities for internally displaced persons in Cyprus.

Negotiations to find a solution to the Cyprus problem have been taking place on and off since 1964. Between 1974 and 2002, the Turkish Cypriot side was seen by the international community as the side refusing a balanced solution. Since 2002, the situation has been reversed according to US and UK officials, and the Greek Cypriot side rejected a plan which would have called for the dissolution of the Republic of Cyprus without guarantees that the Turkish occupation forces would be removed. The latest Annan Plan to reunify the island which was endorsed by the United States, United Kingdom, and Turkey was accepted by a referendum by Turkish Cypriots but overwhelmingly rejected in parallel referendum by Greek Cypriots, after the Greek Cypriot Leadership and  The entire island entered the EU on 1 May 2004 still divided, although the EU

The entire island entered the EU on 1 May 2004 still divided, although the EU

The House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee report on Cyprus

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20070927015015/http://www.hr-action.org/chr/ECHR02.html 2nd Report of the European Commission of Human Rights; Turkey's invasion in Cyprus and aftermath (19 May 1976 to 10 February 1983)]

European Court of Human Rights Case of Cyprus v. Turkey (Application no. 25781/94)

Policy Watershed: Turkey's Cyprus Policy and the Interventions of 1974

, Princeton University Press *

Europe: Cyprus — The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency

CIA

Cyprus-Conflict.net

– a neutral educational website on the conflict {{DEFAULTSORT:Turkish Invasion Of Cyprus Conflicts in 1974 Cyprus dispute Turkish Cypriot nationalism Invasions of Cyprus Invasions by Turkey Military history of Cyprus Wars involving Cyprus Wars involving Turkey 1974 in Cyprus 1974 in Turkey 1970s in Greek politics Cyprus–Turkey relations Ethnic cleansing in Asia Amphibious operations July 1974 events August 1974 events

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Turkish Cypriots

Turkish Cypriots or Cypriot Turks ( tr, Kıbrıs Türkleri or ''Kıbrıslı Türkler''; el, Τουρκοκύπριοι, Tourkokýprioi) are ethnic Turks originating from Cyprus. Following the Ottoman conquest of the island in 1571, about 30,0 ...

, and in response to a Greek junta-sponsored Cypriot coup d'état five days earlier, it led to the Turkish capture and occupation of the northern part of the island.

The coup was ordered by the military junta in Greece and staged by the Cypriot National Guard

, name2 = National Guard General Staff

, image = Emblem of the Cypriot National Guard.svg

, image_size = 100px

, caption = Emblem of the National Guard of Cyprus

, image2 = Flag of the ...

in conjunction with EOKA B

EOKA-B () was a Greek Cypriot paramilitary organisation formed in 1971 by General Georgios Grivas ("Digenis"). It followed an ultra right-wing nationalistic ideology and had the ultimate goal of achieving the '' enosis'' (union) of Cyprus wit ...

. It deposed the Cypriot president Archbishop Makarios III and installed Nikos Sampson

Nikos Sampson (born Nikos Georgiadis, el, Νίκος Γεωργιάδης; 16 December 1935 – 9 May 2001) was the ''de facto'' president of Cyprus who succeeded Archbishop Makarios, appointed as the president of Cyprus by the Greek military ...

. The aim of the coup was the union (''enosis'') of Cyprus with Greece, and the Hellenic Republic of Cyprus to be declared.

The Turkish forces landed in Cyprus on 20 July and captured 3% of the island before a ceasefire was declared. The Greek military junta collapsed and was replaced by a civilian government. Following the breakdown of peace talks, another Turkish invasion in August 1974 resulted in the capture of approximately 36% of the island. The ceasefire line from August 1974 became the United Nations Buffer Zone in Cyprus

The United Nations Buffer Zone in Cyprus is a demilitarized zone, patrolled by the United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP), that was established in 1964 and extended in 1974 after the ceasefire of 16 August 1974, following the ...

and is commonly referred to as the Green Line.

Around 150,000 people (amounting to more than one-quarter of the total population of Cyprus, and to one-third of its Greek Cypriot population) were expelled from the northern part of the island, where Greek Cypriots had constituted 80% of the population. Over the course of the next year, roughly 60,000 Turkish Cypriots

Turkish Cypriots or Cypriot Turks ( tr, Kıbrıs Türkleri or ''Kıbrıslı Türkler''; el, Τουρκοκύπριοι, Tourkokýprioi) are ethnic Turks originating from Cyprus. Following the Ottoman conquest of the island in 1571, about 30,0 ...

,. amounting to half the Turkish Cypriot population, were displaced from the south to the north. The Turkish invasion ended in the partition of Cyprus along the UN-monitored Green Line, which still divides Cyprus, and the formation of a ''de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with ''de jure'' ("by la ...

'' Autonomous Turkish Cypriot Administration

The Autonomous Turkish Cypriot Administration ( tr, ) was the name of a ''de facto'' administration established by the Turkish Cypriots in present-day Northern Cyprus immediately after the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974.

Politics

The fi ...

in the north. In 1983, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus

Northern Cyprus ( tr, Kuzey Kıbrıs), officially the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC; tr, Kuzey Kıbrıs Türk Cumhuriyeti, ''KKTC''), is a ''de facto'' state that comprises the northeastern portion of the island of Cyprus. Reco ...

(TRNC) declared independence, although Turkey is the only country that recognises it. The international community considers the TRNC's territory as Turkish-occupied territory of the Republic of Cyprus. The occupation is viewed as illegal under international law, amounting to illegal occupation of European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been de ...

territory since Cyprus became a member.

Background

Ottoman and British rule

In 1571 the mostly Greek-populated island of Cyprus was conquered by theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, following the Ottoman–Venetian War (1570–1573)

The Fourth Ottoman–Venetian War, also known as the War of Cyprus ( it, Guerra di Cipro) was fought between 1570 and 1573. It was waged between the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Venice, the latter joined by the Holy League, a coalition o ...

. After 300 years of Ottoman rule the island and its population was leased to Britain by the Cyprus Convention

The Cyprus Convention of 4 June 1878 was a secret agreement reached between Great Britain and the Ottoman Empire which granted administrative control of Cyprus to Britain (see British Cyprus), in exchange for its support of the Ottomans during ...

, an agreement reached during the Congress of Berlin

The Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878) was a diplomatic conference to reorganise the states in the Balkan Peninsula after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, which had been won by Russia against the Ottoman Empire. Represented at th ...

in 1878 between the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and the Ottoman Empire. On 5 November 1914, in response to the Ottoman Empire's entry into the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

on the side of the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

, the United Kingdom formally declared Cyprus (together with Egypt and Sudan) a protectorate of the British Empire and later a Crown colony, known as British Cyprus

British Cyprus was the island of Cyprus under the dominion of the British Empire, administered sequentially from 1878 to 1914 as a British protectorate, from 1914 to 1925 as a unilaterally annexed military occupation, and from 1925 to 1960 as a ...

. Article 20 of the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923 marked the end of the Turkish claim to the island. Article 21 of the treaty gave Turkish nationals ordinarily resident in Cyprus the choice of leaving the island within 2 years or to remain as British subjects.

At this time the population of Cyprus was composed of both Greeks and Turks, who identified themselves with their respective homeland. However, the elites of both communities shared the belief that they were socially more progressive and better educated, and therefore distinct from the mainlanders. Greek and Turkish Cypriots lived quietly side by side for many years.

Broadly, three main forces can be held responsible for transforming two ethnic communities into two national ones: education, British colonial practices, and insular religious teachings accompanying economic development. Formal education was perhaps the most important as it affected Cypriots during childhood and youth; education has been a main vehicle of transferring inter-communal hostility.

British colonial policies, such as the principle of "divide and rule

Divide and rule policy ( la, divide et impera), or divide and conquer, in politics and sociology is gaining and maintaining power divisively. Historically, this strategy was used in many different ways by empires seeking to expand their ter ...

", promoted ethnic polarisation as a strategy to reduce the threat to colonial control. For example, when Greek Cypriots

Greek Cypriots or Cypriot Greeks ( el, Ελληνοκύπριοι, Ellinokýprioi, tr, Kıbrıs Rumları) are the ethnic Greek population of Cyprus, forming the island's largest ethnolinguistic community. According to the 2011 census, 659,115 ...

rebelled in the 1950s, the Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created to deal with the colonial affairs of British North America but required also to oversee the increasing number of c ...

expanded the size of the Auxiliary Police

Auxiliary police, also called special police, are usually the part-time reserves of a regular police force. They may be armed or unarmed. They may be unpaid volunteers or paid members of the police service with which they are affiliated. The po ...

and in September 1955, established the Special Mobile Reserve which was made up exclusively of Turkish Cypriots

Turkish Cypriots or Cypriot Turks ( tr, Kıbrıs Türkleri or ''Kıbrıslı Türkler''; el, Τουρκοκύπριοι, Tourkokýprioi) are ethnic Turks originating from Cyprus. Following the Ottoman conquest of the island in 1571, about 30,0 ...

, to combat EOKA. This and similar practices contributed to inter-communal animosity.

Although economic development

In the economics study of the public sector, economic and social development is the process by which the economic well-being and quality of life of a nation, region, local community, or an individual are improved according to targeted goals and ...

and increased education reduced the explicitly religious characteristics of the two communities, the growth of nationalism on the two mainlands increased the significance of other differences. Turkish nationalism

Turkish nationalism ( tr, Türk milliyetçiliği) is a political ideology that promotes and glorifies the Turkish people, as either a national, ethnic, or linguistic group. The term " ultranationalism" is often used to describe Turkish nationa ...

was at the core of the revolutionary programme promoted by the father of modern Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881–1938) and affected Turkish Cypriots who followed his principles. President of the Republic of Turkey from 1923 to 1938, Atatürk attempted to build a new nation on the ruins of the Ottoman Empire and elaborated the programme of " six principles" (the "Six Arrows") to do so.

These principles of secularism

Secularism is the principle of seeking to conduct human affairs based on secular, naturalistic considerations.

Secularism is most commonly defined as the separation of religion from civil affairs and the state, and may be broadened to a sim ...

(laicism

Laicism refers to the policies and principles where the state plays a more active role in excluding religious visibility from the public domain.

Secularism in France has been described to be laicist in its form.

See also

* Laicization

* Seculari ...

) and nationalism reduced Islam's role in the everyday life of individuals and emphasised Turkish identity as the main source of nationalism. Traditional education with a religious foundation was discarded and replaced with one that followed secular principles and, shorn of Arab and Persian influences, was purely Turkish. Turkish Cypriots quickly adopted the secular programme of Turkish nationalism.

Under Ottoman rule Turkish Cypriots had been classified as Muslims, a distinction based on religion. Being thoroughly secular, Atatürk's programme made their Turkish identity paramount, and may have further reinforced their division from their Greek Cypriot neighbours.

1950s

In the early 1950s, a Greek nationalist group was formed called the ''Ethniki Organosis Kyprion Agoniston'' ( EOKA, or "National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters"). Their objective was to drive the British out of the island first, and then to integrate the island with Greece. EOKA wished to remove all obstacles from their path to independence, or union with Greece. The first secret talks for EOKA, as anationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

organisation established to integrate the island with Greece, were started under the chairmanship of Archbishop Makarios III in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

on 2 July 1952. In the aftermath of these meetings a "Council of Revolution" was established on 7 March 1953. In early 1954 secret weaponry shipments to Cyprus started with the knowledge of the Greek government

Greece is a parliamentary representative democratic republic, where the President of Greece is the head of state and the Prime Minister of Greece is the head of government within a multi-party system. Legislative power is vested in both the go ...

. Lt. Georgios Grivas

Georgios Grivas ( el, Γεώργιος Γρίβας; 6 June 1897 – 27 January 1974), also known by his nickname Digenis ( el, Διγενής), was a Cypriot general in the Hellenic Army and the leader of the Organization X (1942-1949), EOKA ...

, formerly an officer in the Greek army, covertly disembarked on the island on 9 November 1954 and EOKA's campaign against the British forces began to grow.

The first Turk to be killed by EOKA on 21 June 1955 was a policeman. EOKA also killed Greek Cypriot leftists. After the September 1955 Istanbul Pogrom, EOKA started its activity against Turkish Cypriots.

A year later EOKA revived its attempts to achieve the union of Cyprus with Greece. Turkish Cypriots were recruited into the police by the British forces to fight against Greek Cypriots, but EOKA initially did not want to open up a second front against Turkish Cypriots. However, in January 1957, EOKA forces began targeting and killing Turkish Cypriot police deliberately to provoke Turkish Cypriot riots in Nicosia, which diverted the British army's attention away from their positions in the mountains. In the riots, at least one Greek Cypriot was killed, which was presented by the Greek Cypriot leadership as an act of Turkish aggression.

The Turkish Resistance Organisation

The Turkish Resistance Organisation ( tr, Türk Mukavemet Teşkilatı, TMT) was a Turkish Cypriot pro- taksim paramilitary organisation formed by Rauf Denktaş and Turkish military officer Rıza Vuruşkan in 1958 as an organisation to counter t ...

(TMT, ''Türk Mukavemet Teşkilatı'') was formed initially as a local initiative to prevent the union with Greece which was viewed by Turkish Cypriots as an existential threat due to the exodus of Cretan Turks

The Cretan Muslims ( el, Τουρκοκρητικοί or , or ; tr, Giritli, , or ; ar, أتراك كريت) or Cretan Turks were the Muslim inhabitants of the island of Crete. Their descendants settled principally in Turkey, the Dodecanese ...

from Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

once the union with Greece was achieved. It was later supported and organised directly by the Turkish government, and the TMT declared war on the Greek Cypriot rebels as well.Roni Alasor, ''Sifreli Mesaj: "Trene bindir!"'',

On 12 June 1958, eight Greek Cypriot men from Kondemenos village, who were arrested by the British police as part of an armed group suspected of preparing an attack against the Turkish Cypriot quarter of Skylloura, were killed by the TMT near the Turkish Cypriot populated village of Gönyeli, after being dropped off there by the British authorities. TMT also blew up the offices of the Turkish press office in Nicosia in a false flag operation to attach blame to Greek Cypriots.Arif Hasan Tahsin, ''The rise of Dektash to power'', It also began a string of assassinations of prominent Turkish Cypriot supporters of independence. The following year, after the conclusion of the independence agreements on Cyprus, the Turkish Navy

The Turkish Naval Forces ( tr, ), or Turkish Navy ( tr, ) is the naval warfare service branch of the Turkish Armed Forces.

The modern naval traditions and customs of the Turkish Navy can be traced back to 10 July 1920, when it was establis ...

sent a ship to Cyprus fully loaded with arms for the TMT. The ship was stopped and the crew was caught red-handed in the infamous "Deniz" incident.

1960–1963

British rule lasted until 1960 when the island was declared an independent state under the London-Zurich agreements. The agreement created a foundation for the Republic of Cyprus by the Turkish Cypriot and Greek Cypriot communities, although the republic was seen as a necessary compromise between the two reluctant communities.

The 1960 Constitution of the Cyprus Republic proved unworkable however, lasting only three years. Greek Cypriots wanted to end the separate Turkish Cypriot municipal councils permitted by the British in 1958, made subject to review under the 1960 agreements. For many Greek Cypriots these municipalities were the first stage on the way to the partition they feared. The Greek Cypriots wanted '' enosis'', integration with Greece, while Turkish Cypriots wanted '' taksim'', partition between Greece and Turkey.

Resentment also rose within the Greek Cypriot community because Turkish Cypriots had been given a larger share of governmental posts than the size of their population warranted. In accordance with the constitution 30% of civil service jobs were allocated to the Turkish community despite being only 18.3% of the population. Additionally, the position of vice president was reserved for the Turkish population, and both the president and vice president were given veto power over crucial issues.Borowiec, Andrew. Cyprus: A Troubled Island. Westport: Praeger. 2000. 47

British rule lasted until 1960 when the island was declared an independent state under the London-Zurich agreements. The agreement created a foundation for the Republic of Cyprus by the Turkish Cypriot and Greek Cypriot communities, although the republic was seen as a necessary compromise between the two reluctant communities.

The 1960 Constitution of the Cyprus Republic proved unworkable however, lasting only three years. Greek Cypriots wanted to end the separate Turkish Cypriot municipal councils permitted by the British in 1958, made subject to review under the 1960 agreements. For many Greek Cypriots these municipalities were the first stage on the way to the partition they feared. The Greek Cypriots wanted '' enosis'', integration with Greece, while Turkish Cypriots wanted '' taksim'', partition between Greece and Turkey.

Resentment also rose within the Greek Cypriot community because Turkish Cypriots had been given a larger share of governmental posts than the size of their population warranted. In accordance with the constitution 30% of civil service jobs were allocated to the Turkish community despite being only 18.3% of the population. Additionally, the position of vice president was reserved for the Turkish population, and both the president and vice president were given veto power over crucial issues.Borowiec, Andrew. Cyprus: A Troubled Island. Westport: Praeger. 2000. 47

1963–1974

In December 1963, the President of the Republic Makarios proposed thirteen constitutional amendments after the government was blocked by Turkish Cypriot legislators. Frustrated by these impasses and believing that the constitution prevented enosis, the Greek Cypriot leadership believed that the rights given to Turkish Cypriots under the 1960 constitution were too extensive and had designed the Akritas plan, which was aimed at reforming the constitution in favour of Greek Cypriots, persuading the international community about the correctness of the changes and violently subjugating Turkish Cypriots in a few days should they not accept the plan.Eric Solsten, ed. ''Cyprus: A Country Study'', Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 1991. The amendments would have involved the Turkish community giving up many of their protections as a minority, including adjusting ethnic quotas in the government and revoking the presidential and vice presidential veto power. These amendments were rejected by the Turkish side and the Turkish representation left the government, although there is some dispute over whether they left in protest or were forced out by the National Guard. The 1960 constitution fell apart and communal violence erupted on 21 December 1963, when two Turkish Cypriots were killed at an incident involving the Greek Cypriot police. Turkey, the UK and Greece, the guarantors of the

Zürich and London Agreement

, neighboring_municipalities = Adliswil, Dübendorf, Fällanden, Kilchberg, Maur, Oberengstringen, Opfikon, Regensdorf, Rümlang, Schlieren, Stallikon, Uitikon, Urdorf, Wallisellen, Zollikon

, twintowns = Kunming, San Francisco

Zürich ...

s which had led to Cyprus' independence, wanted to send a NATO force to the island under the command of General Peter Young.

Both President Makarios and Dr. Küçük issued calls for peace, but these were ignored. Meanwhile, within a week of the violence flaring up, the Turkish army

The Turkish Land Forces ( tr, Türk Kara Kuvvetleri), or Turkish Army (Turkish: ), is the main branch of the Turkish Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. The army was formed on November 8, 1920, after the collapse of the ...

contingent had moved out of its barracks and seized the most strategic position on the island across the Nicosia to Kyrenia road, the historic jugular vein of the island. They retained control of that road until 1974, at which time it acted as a crucial link in Turkey's military invasion. From 1963 up to the point of the Turkish invasion of 20 July 1974, Greek Cypriots who wanted to use the road could only do so if accompanied by a UN convoy.

700 Turkish residents of northern Nicosia, among them women and children, were taken hostage. The violence resulted in the death of 364 Turkish and 174 Greek Cypriots,Oberling, Pierre. ''The Road to Bellapais'' (1982), Social Science Monographsp.120

: "According to official records, 364 Turkish Cypriots and 174 Greek Cypriots were killed during the 1963–1964 crisis." destruction of 109 Turkish Cypriot or mixed villages and displacement of 25,000–30,000 Turkish Cypriots. The British '' Daily Telegraph'' later called it an "anti Turkish pogrom". Thereafter Turkey once again put forward the idea of partition. The intensified fighting especially around areas under the control of Turkish Cypriot militias, as well as the failure of the constitution were used as justification for a possible Turkish invasion. Turkey was on the brink of invading when

US president

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

Johnson stated, in his famous letter of 5 June 1964, that the US was against a possible invasion and stated that he would not come to the aid of Turkey if an invasion of Cyprus led to conflict with the Soviet Union. One month later, within the framework of a plan prepared by the US Secretary of State, Dean Rusk

David Dean Rusk (February 9, 1909December 20, 1994) was the United States Secretary of State from 1961 to 1969 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, the second-longest serving Secretary of State after Cordell Hull from the F ...

, negotiations with Greece and Turkey began.

The crisis resulted in the end of the Turkish Cypriot involvement in the administration and their claiming that it had lost its legitimacy; the nature of this event is still controversial. In some areas, Greek Cypriots prevented Turkish Cypriots from travelling and entering government buildings, while some Turkish Cypriots willingly refused to withdraw due to the calls of the Turkish Cypriot administration. They started living in enclaves

An enclave is a territory (or a small territory apart of a larger one) that is entirely surrounded by the territory of one other state or entity. Enclaves may also exist within territorial waters. ''Enclave'' is sometimes used improperly to deno ...

in different areas that were blockaded by the National Guard and were directly supported by Turkey. The republic's structure was changed unilaterally by Makarios and Nicosia was divided by the Green Line, with the deployment of UNFICYP troops. In response to this, their movement and access to basic supplies became more restricted by Greek forces.

Fighting broke out again in 1967, as the Turkish Cypriots pushed for more freedom of movement. Once again, the situation was not settled until Turkey threatened to invade on the basis that it would be protecting the Turkish population from ethnic cleansing by Greek Cypriot forces. To avoid that, a compromise was reached for Greece to be forced to remove some of its troops from the island; for Georgios Grivas, EOKA leader, to be forced to leave Cyprus and for the Cypriot government to lift some restrictions of movement and access to supplies of the Turkish populations.

Greek military coup and Turkish invasion

Greek military coup of July 1974

In the spring of 1974, Greek Cypriot intelligence discovered thatEOKA-B

EOKA-B () was a Greek Cypriot paramilitary organisation formed in 1971 by General Georgios Grivas ("Digenis"). It followed an ultra right-wing nationalistic ideology and had the ultimate goal of achieving the ''enosis'' (union) of Cyprus with ...

was planning a coup against President Makarios Macarius is a Latinized form of the old Greek given name Makários (Μακάριος), meaning "happy, fortunate, blessed"; confer the Latin '' beatus'' and ''felix''. Ancient Greeks applied the epithet ''Makarios'' to the gods.

In other langua ...

which was sponsored by the military junta of Athens.

The junta had come to power in a military coup in Athens in 1967. In the autumn of 1973 after the 17 November student uprising there had been a further coup in Athens in which the original Greek junta had been replaced by one still more obscurantist headed by the Chief of Military Police, Brigadier Ioannides, though the actual head was General Phaedon Gizikis

Phaedon Gizikis ( el, Φαίδων Γκιζίκης ; 16 June 1917 – 26 July 1999) was a Greek army general, and the second and last President of Greece under the Junta, from 1973 to 1974.

Early life and military career

Born in Volos, ...

. Ioannides believed that Makarios was no longer a true supporter of enosis, and suspected him of being a communist sympathiser. This led Ioannides to support the EOKA-B and National Guard as they tried to undermine Makarios.

On 2 July 1974, Makarios wrote an open letter to President Gizikis complaining bluntly that 'cadres of the Greek military regime support and direct the activities of the 'EOKA-B' terrorist organisation'. He also ordered that Greece remove some 600 Greek officers in the Cypriot National Guard from Cyprus. The Greek Government's immediate reply was to order the go-ahead of the coup. On 15 July 1974 sections of the Cypriot National Guard

, name2 = National Guard General Staff

, image = Emblem of the Cypriot National Guard.svg

, image_size = 100px

, caption = Emblem of the National Guard of Cyprus

, image2 = Flag of the ...

, led by its Greek officers, overthrew the government.

Makarios narrowly escaped death in the attack. He fled the presidential palace from its back door and went to Paphos

Paphos ( el, Πάφος ; tr, Baf) is a coastal city in southwest Cyprus and the capital of Paphos District. In classical antiquity, two locations were called Paphos: Old Paphos, today known as Kouklia, and New Paphos.

The current city of Pap ...

, where the British managed to retrieve him by Westland Whirlwind helicopter in the afternoon of 16 July and flew him from Akrotiri to Malta in a Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

Armstrong Whitworth Argosy

The Armstrong Whitworth Argosy was a three-engine biplane airliner designed and produced by the British aircraft manufacturer Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft. It was the company's first airliner.

The Argosy was developed during the early-to-mid ...

transport aircraft and from there to London by de Havilland Comet

The de Havilland DH.106 Comet was the world's first commercial jet airliner. Developed and manufactured by de Havilland in the United Kingdom, the Comet 1 prototype first flew in 1949. It featured an aerodynamically clean design with four ...

the next morning.

In the meantime, Nikos Sampson

Nikos Sampson (born Nikos Georgiadis, el, Νίκος Γεωργιάδης; 16 December 1935 – 9 May 2001) was the ''de facto'' president of Cyprus who succeeded Archbishop Makarios, appointed as the president of Cyprus by the Greek military ...

was declared provisional president of the new government. Sampson was an ultra-nationalist, pro-''Enosis'' combatant who was known to be fanatically anti-Turkish and had taken part in violence against Turkish civilians in earlier conflicts.

The Sampson regime took over radio stations and declared that Makarios had been killed; but Makarios, safe in London, was soon able to counteract these reports. The Turkish-Cypriots were not affected by the coup against Makarios; one of the reasons was that Ioannides did not want to provoke a Turkish reaction.

In response to the coup, US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

sent Joseph Sisco to try to mediate the conflict. Turkey issued a list of demands to Greece via a US negotiator. These demands included the immediate removal of Nikos Sampson, the withdrawal of 650 Greek officers from the Cypriot National Guard, the admission of Turkish troops to protect their population, equal rights for both populations, and access to the sea from the northern coast for Turkish Cypriots. Turkey, led by Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit, then appealed to the UK as a signatory of the Treaty of Guarantee to take action to return Cyprus to its neutral status. The UK declined this offer, and refused to let Turkey use its bases on Cyprus as part of the operation.

According to American diplomat James W. Spain

James William Spain (July 22, 1926 – January 2, 2008) was in the US Foreign Service with postings in Karachi, Islamabad, Istanbul, Ankara, Dar Es Salaam, and Colombo and four ambassadorships in Tanzania, Turkey, the United Nations (as de ...

, on the eve of the Turkish invasion US president Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

sent a letter to

Bülent Ecevit that was not just reminiscent of Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

's letter to İsmet İnönü

Mustafa İsmet İnönü (; 24 September 1884 – 25 December 1973) was a Turkish army officer and statesman of Kurdish descent, who served as the second President of Turkey from 11 November 1938 to 22 May 1950, and its Prime Minister three tim ...

in the Cyprus crisis of 1963–64

Several distinct periods of Cypriot intercommunal violence involving the two main ethnic communities, Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots, marked mid-20th century Cyprus. These included the Cyprus Emergency of 1955–59 during British rule, the ...

, but even harsher. However, Nixon's letter never reached the hands of the Turkish prime minister, and no one ever heard anything about it.

First Turkish invasion, July 1974

Limassol

Limassol (; el, Λεμεσός, Lemesós ; tr, Limasol or ) is a city on the southern coast of Cyprus and capital of the district with the same name. Limassol is the second largest urban area in Cyprus after Nicosia, with an urban population ...

surrendered to the Cypriot National Guard. Following this, according to Turkish Cypriot and Greek Cypriot eyewitness accounts, the Turkish Cypriot quarter was burned, women raped and children shot. 1,300 Turkish Cypriots were confined in a prison camp afterwards. The enclave in Famagusta was subjected to shelling and the Turkish Cypriot town of Lefka

Lefka ( el, Λεύκα; tr, Lefke) is a town in Cyprus, overlooking Morphou Bay. It is under the ''de facto'' control of Northern Cyprus. In 2011, the town proper had 3,009 inhabitants. It is the capital of the Lefke District of Northern Cyprus ...

was occupied by Greek Cypriot troops.

According to the International Committee of the Red Cross

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC; french: Comité international de la Croix-Rouge) is a humanitarian organization which is based in Geneva, Switzerland, and it is also a three-time Nobel Prize Laureate. State parties (signato ...

, the prisoners of war taken at this stage and before the second invasion included 385 Greek Cypriots in Adana

Adana (; ; ) is a major city in southern Turkey. It is situated on the Seyhan River, inland from the Mediterranean Sea. The administrative seat of Adana province, it has a population of 2.26 million.

Adana lies in the heart of Cilicia, wh ...

, 63 Greek Cypriots in the Saray Prison and 3,268 Turkish Cypriots in various camps in Cyprus.

On the night of 21 to 22 July 1974, a battalion of Greek commandos was transported to Nicosia from Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

in a clandestine airlift operation.

Collapse of the Greek junta and peace talks

On 23 July 1974 theGreek military junta

The Greek junta or Regime of the Colonels, . Also known within Greece as just the Junta ( el, η Χούντα, i Choúnta, links=no, ), the Dictatorship ( el, η Δικτατορία, i Diktatoría, links=no, ) or the Seven Years ( el, η Ε ...

collapsed mainly because of the events in Cyprus. Greek political leaders in exile started returning to the country. On 24 July 1974 Constantine Karamanlis

Konstantinos G. Karamanlis ( el, Κωνσταντίνος Γ. Καραμανλής, ; 8 March 1907 – 23 April 1998), commonly Anglicisation, anglicised to Constantine Karamanlis or just Caramanlis, was a four-time prime minister and List of he ...

returned from Paris and was sworn in as Prime Minister. He kept Greece from entering the war, an act that was highly criticised as an act of treason. Shortly after this Nikos Sampson renounced the presidency and Glafcos Clerides temporarily took the role of president.

The first round of peace talks took place in Geneva

, neighboring_municipalities= Carouge, Chêne-Bougeries, Cologny, Lancy, Grand-Saconnex, Pregny-Chambésy, Vernier, Veyrier

, website = https://www.geneve.ch/

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevr ...

, Switzerland between 25 and 30 July 1974, James Callaghan, the British Foreign Secretary, having summoned a conference of the three guarantor powers. There they issued a declaration that the Turkish occupation zone should not be extended, that the Turkish enclaves should immediately be evacuated by the Greeks, and that a further conference should be held at Geneva with the two Cypriot communities present to restore peace and re-establish constitutional government. In advance of this they made two observations, one upholding the 1960 constitution, the other appearing to abandon it. They called for the Turkish Vice-President to resume his functions, but they also noted 'the existence in practice of two autonomous administrations, that of the Greek Cypriot community and that of the Turkish Cypriot community'.

By the time that the second Geneva conference met on 14 August 1974, international sympathy (which had been with the Turks in their first attack) was swinging back towards Greece now that it had restored democracy. At the second round of peace talks, Turkey demanded that the Cypriot government accept its plan for a federal state

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government ( federalism). In a federation, the self-gover ...

, and population transfer

Population transfer or resettlement is a type of mass migration, often imposed by state policy or international authority and most frequently on the basis of ethnicity or religion but also due to economic development. Banishment or exile is ...

. When the Cypriot acting president

An acting president is a person who temporarily fills the role of a country's president when the incumbent president is unavailable (such as by illness or a vacation) or when the post is vacant (such as for death, injury, resignation, dismissal ...

Clerides asked for 36 to 48 hours in order to consult with Athens and with Greek Cypriot leaders, the Turkish Foreign Minister denied Clerides that opportunity on the grounds that Makarios and others would use it to play for more time.

Second Turkish invasion, 14–16 August 1974

The Turkish Foreign Minister Turan Güneş had said to the Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit, "When I say 'Ayşe should go on vacation' ( Turkish: ''"Ayşe Tatile Çıksın"''), it will mean that our armed forces are ready to go into action. Even if the telephone line is tapped, that would rouse no suspicion." An hour and a half after the conference broke up, Turan Güneş called Ecevit and said the code phrase. On 14 August Turkey launched its "Second Peace Operation", which eventually resulted in the Turkish occupation of 37% of Cyprus. Turkish occupation reached as far south as the

The Turkish Foreign Minister Turan Güneş had said to the Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit, "When I say 'Ayşe should go on vacation' ( Turkish: ''"Ayşe Tatile Çıksın"''), it will mean that our armed forces are ready to go into action. Even if the telephone line is tapped, that would rouse no suspicion." An hour and a half after the conference broke up, Turan Güneş called Ecevit and said the code phrase. On 14 August Turkey launched its "Second Peace Operation", which eventually resulted in the Turkish occupation of 37% of Cyprus. Turkish occupation reached as far south as the Louroujina Salient

Louroujina ( []; , previously or ) is a village in Geography of Cyprus, Cyprus, located within the salient (geography), salient that marks the southernmost extent of Northern Cyprus. It was one of the largest Turkish Cypriot villages in Cyprus be ...

.

In the process, many Greek Cypriots became refugees. The number of refugees is estimated to be between 140,000 and 160,000. The ceasefire line from 1974 separates the two communities on the island, and is commonly referred to as the Green Line.

After the conflict, Cypriot representatives and the United Nations consented to the transfer of the remainder of the 51,000 Turkish Cypriots that had not left their homes in the south to settle in the north, if they wished to do so.

The United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

has challenged the legality of Turkey's action, because Article Four of the Treaty of Guarantee gives the right to guarantors to take action with the sole aim of re-establishing the state of affairs. The aftermath of Turkey's invasion, however, did not safeguard the Republic's sovereignty and territorial integrity, but had the opposite effect: the ''de facto'' partition of the Republic and the creation of a separate political entity in the north. On 13 February 1975, Turkey declared the occupied areas of the Republic of Cyprus to be a "Federated Turkish State", to the universal condemnation of the international community (see United Nations Security Council Resolution 367

United Nations Security Council Resolution 367, adopted on 12 March 1975, after receiving a complaint from the Government of the Republic of Cyprus, the Council again called upon all States to respect the sovereignty, independence, territorial in ...

). The United Nations recognises the sovereignty of the Republic of Cyprus according to the terms of its independence in 1960. The conflict continues to affect Turkey's relations with Cyprus, Greece, and the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been de ...

.

Human rights violations

Against Greek Cypriots

p. 160,161,162,163.

/ref> The Turkish policy of violently forcing a third of the island's Greek population from their homes in the occupied North, preventing their return and settling Turks from mainland Turkey is considered an example of ethnic cleansing. In 1976 and again in 1983, the

European Commission of Human Rights

The European Commission of Human Rights was a special body of the Council of Europe.

From 1954 to the entry into force of Protocol 11 to the European Convention on Human Rights, individuals did not have direct access to the European Court of Hu ...

found Turkey guilty of repeated violations of the European Convention of Human Rights

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR; formally the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms) is an international convention to protect human rights and political freedoms in Europe. Drafted in 1950 by th ...

. Turkey has been condemned for preventing the return of Greek Cypriot refugees to their properties. The European Commission of Human Rights reports of 1976 and 1983 state the following:

Enclaved Greek Cypriots in the Karpass Peninsula

The Karpas Peninsula ( el, Καρπασία; tr, Karpaz), also known as the Karpass, Karpaz or Karpasia, is a long, finger-like peninsula that is one of the most prominent geographical features of the island of Cyprus. Its farthest extent is ...

in 1975 were subjected by the Turks to violations of their human rights so that by 2001 when the European Court of Human Rights found Turkey guilty of the violation of 14 articles of the European Convention of Human Rights in its judgement of Cyprus v. Turkey (application no. 25781/94), less than 600 still remained. In the same judgement, Turkey was found guilty of violating the rights of the Turkish Cypriots by authorising the trial of civilians by a military court

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

.

The European commission of Human Rights with 12 votes against 1, accepted evidence from the Republic of Cyprus, concerning the rapes of various Greek-Cypriot women by Turkish soldiers and the torture of many Greek-Cypriot prisoners during the invasion of the island.European Commission of Human Rights, "Report of the Commission to Applications 6780/74 and 6950/75", Council of Europe, 1976p. 120,124.

Link from Internet Archive

/ref> The high rate of rape reportedly resulted in the temporary permission of abortion in Cyprus by the conservative

Cypriot Orthodox Church

The Church of Cyprus ( el, Ἐκκλησία τῆς Κύπρου, translit=Ekklisia tis Kyprou; tr, Kıbrıs Kilisesi) is one of the autocephalous Greek Orthodox churches that together with other Eastern Orthodox churches form the communion ...

. According to Paul Sant Cassia, rape was used systematically to "soften" resistance and clear civilian areas through fear. Many of the atrocities were seen as revenge for the atrocities against Turkish Cypriots in 1963–64 and the massacres during the first invasion. It has been suggested that many of the atrocities were revenge killings, committed by Turkish Cypriot fighters in military uniform who might have been mistaken for Turkish soldiers. In the Karpass Peninsula

The Karpas Peninsula ( el, Καρπασία; tr, Karpaz), also known as the Karpass, Karpaz or Karpasia, is a long, finger-like peninsula that is one of the most prominent geographical features of the island of Cyprus. Its farthest extent is ...

, a group of Turkish Cypriots reportedly chose young girls to rape and impregnated teenage girls. There were cases of rapes, which included gang rapes, of teenage girls by Turkish soldiers and Turkish Cypriot men in the peninsula, and one case involved the rape of an old Greek Cypriot man by a Turkish Cypriot. The man was reportedly identified by the victim and two other rapists were also arrested. Raped women were sometimes outcast from society.

Against Turkish Cypriots

During the

During the Maratha, Santalaris and Aloda massacre

Maratha, Santalaris and Aloda massacre ( tr, Muratağa, Sandallar ve Atlılar katliamı) refers to a massacreOberling, Pierre. The road to Bellapais: the Turkish Cypriot exodus to northern Cyprus' (1982), Social Science Monographs, p. 185 of Turk ...

by EOKA B, 126 people were killed on 14 August 1974.Oberling, Pierre. The road to Bellapais: the Turkish Cypriot exodus to northern Cyprus

'' (1982), Social Science Monographs, p. 185Paul Sant Cassia, ''Bodies of Evidence: Burial, Memory, and the Recovery of Missing Persons in Cyprus'', Berghahn Books, 2007,

p. 237

The

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

described the massacre as a crime against humanity

Crimes against humanity are widespread or systemic acts committed by or on behalf of a ''de facto'' authority, usually a state, that grossly violate human rights. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity do not have to take place within the ...

, by saying "constituting a further crime against humanity committed by the Greek and Greek Cypriot gunmen." In the Tochni massacre

Tochni massacre refers to the killing of 84 Turkish Cypriots from the village of Tochni, Larnaca, Cyprus by Greek Cypriot members of EOKA B during the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in the Summer of 1974.

Background

During the Turkish invasion a ...

, 85 Turkish Cypriot inhabitants were massacred.Paul Sant Cassia, ''Bodies of Evidence: Burial, Memory, and the Recovery of Missing Persons in Cyprus'', Berghahn Books, 2007; Massacre&f=false p. 61

The ''Washington Post'' covered another news of atrocity in which it is written that: "In a Greek raid on a small Turkish village near Limassol, 36 people out of a population of 200 were killed. The Greeks said that they had been given orders to kill the inhabitants of the Turkish villages before the Turkish forces arrived." In Limassol, upon the fall of the Turkish Cypriot enclave to the Cypriot National Guard, the Turkish Cypriot quarter was burned, women raped and children shot, according to Turkish Cypriot and Greek Cypriot eyewitness accounts. 1300 people were then led to a prison camp.

Missing people

The missing persons list of the Republic of Cyprus confirms that 83 Turkish Cypriots disappeared in Tochni on 14 August 1974. Also, as a result of the invasion, over 2000 Greek-Cypriot prisoners of war were taken to Turkey and detained in Turkish prisons. Some of them were not released and are still missing. In particular, the Committee on Missing Persons (CMP) in Cyprus, which operates under the auspices of the United Nations, is mandated to investigate approximately 1600 cases of Greek Cypriot and Greek missing persons. The issue of missing persons in Cyprus took a new turn in the summer of 2004 when the UN-sponsored Committee on Missing Persons (CMP) began returning remains of identified missing individuals to their families. CMP designed and started to implement (from August 2006) its project on the Exhumation, Identification and Return of Remains of Missing Persons. The whole project is being implemented by bi-communal teams of Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriot scientists (archaeologists, anthropologists and geneticists) under the overall responsibility of the CMP. By the end of 2007, 57 individuals had been identified and their remains returned to their families.Destruction of cultural heritage

mosaic

A mosaic is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and were particularly pop ...

s that survived an edict by the Byzantine Emperor, imposing the destruction of all images of sacred figures. Cyprus won the case, and the mosaics were eventually returned. In October 1997, Aydın Dikmen Aydın Dikmen (born October 15, 1937 – April 8, 2020) is a Turkish art dealer who was arrested in 1998 for trying to sell Eastern Orthodox art that had been looted from Cyprus during the 1974 invasion.

During the Turkish invasion of northern Cyp ...

, who had sold the mosaics, was arrested in Germany in a police raid and found to be in possession of a stash consisting of mosaics, frescoes and icons dating back to the 6th, 12th and 15th centuries, worth over $50 million. The mosaics, depicting Saints Thaddeus and Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

, are two more sections from the apse of the Kanakaria Church, while the frescoes, including the Last Judgement

The Last Judgment, Final Judgment, Day of Reckoning, Day of Judgment, Judgment Day, Doomsday, Day of Resurrection or The Day of the Lord (; ar, یوم القيامة, translit=Yawm al-Qiyāmah or ar, یوم الدین, translit=Yawm ad-Dīn, ...

and the Tree of Jesse

The Tree of Jesse is a depiction in art of the ancestors of Jesus Christ, shown in a branching tree which rises from Jesse of Bethlehem, the father of King David. It is the original use of the family tree as a schematic representation of a g ...

, were taken off the north and south walls of the Monastery of Antiphonitis, built between the 12th and 15th centuries. Frescoes found in possession of Dikmen included those from the 11th–12th century Church of Panagia Pergaminiotisa in Akanthou

Akanthou ( el, Ακανθού, ; tr, Tatlısu) is a village on the northern coast of Cyprus. It is under the ''de facto'' control of Northern Cyprus. , it had a population of 1,459.

History

The first settlement that can be linked with the mod ...

, which had been completely stripped of its ornate frescoes.

According to a Greek Cypriot claim, since 1974, at least 55 churches have been converted into mosques and another 50 churches and monasteries have been converted into stables, stores, hostels, or museums, or have been demolished. According to the government spokesman of the ''de facto'' Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, this has been done to keep the buildings from falling into ruin.

In January 2011, the British singer Boy George

George Alan O'Dowd (born 14 June 1961), known professionally as Boy George, is an English singer, songwriter, DJ, author and mixed media artist. Best known for his soulful voice and his androgynous appearance, Boy George has been the lead singer ...

returned an 18th-century icon of Christ to the Church of Cyprus

The Church of Cyprus ( el, Ἐκκλησία τῆς Κύπρου, translit=Ekklisia tis Kyprou; tr, Kıbrıs Kilisesi) is one of the autocephalous Greek Orthodox churches that together with other Eastern Orthodox churches form the communio ...

that he had bought without knowing the origin. The icon, which had adorned his home for 26 years, had been looted from the church of St Charalampus from the village of New Chorio, near Kythrea

Kythrea ( el, Κυθρέα or ; tr, Değirmenlik) is a small town in Cyprus, 10 km northeast of Nicosia. Kythrea is under the ''de facto'' control of Northern Cyprus.

History

Kythrea is situated near the ancient Greek city-kingdom of Ch ...

, in 1974. The icon was noticed by church officials during a television interview of Boy George at his home. The church contacted the singer who agreed to return the icon at Saints Anargyroi Church, Highgate

Highgate ( ) is a suburban area of north London at the northeastern corner of Hampstead Heath, north-northwest of Charing Cross.

Highgate is one of the most expensive London suburbs in which to live. It has two active conservation organisat ...

, north London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

.

Opinions

Greek Cypriot

Greek Cypriots have claimed that the invasion and subsequent actions by Turkey have been diplomatic ploys, furthered by ultranationalist Turkish militants to justify expansionistPan-Turkism

Pan-Turkism is a political movement that emerged during the 1880s among Turkic intellectuals who lived in the Russian region of Kazan (Tatarstan), Caucasus (modern-day Azerbaijan) and the Ottoman Empire (modern-day Turkey), with its aim bei ...

. They have also criticised the perceived failure of Turkish intervention to achieve or justify its stated goals (protecting the sovereignty, integrity, and independence of the Republic of Cyprus), claiming that Turkey's intentions from the beginning were to create the state of Northern Cyprus.

Greek Cypriots condemn the brutality of the Turkish invasion, including but not limited to the high levels of rape, child rape and torture. Greek Cypriots emphasise that in 1976 and 1983 Turkey was found guilty by the European Commission of Human Rights

The European Commission of Human Rights was a special body of the Council of Europe.

From 1954 to the entry into force of Protocol 11 to the European Convention on Human Rights, individuals did not have direct access to the European Court of Hu ...

of repeated violations of the European Convention of Human Rights

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR; formally the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms) is an international convention to protect human rights and political freedoms in Europe. Drafted in 1950 by th ...

.

Greek Cypriots have also claimed that the second wave of the Turkish invasion that occurred in August 1974, even after the Greek Junta had collapsed on 24 July 1974 and the democratic government of the Republic of Cyprus had been restored under Glafkos Clerides, did not constitute a justified intervention as had been the case with the first wave of the Turkish invasion that led to the Junta's collapse.

The stationing of 40,000 Turkish troops on Northern Cyprus after the invasion in violation of resolutions by the United Nations has also been criticised.

The United Nations Security Council Resolution 353, adopted unanimously on 20 July 1974, in response to the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, the Council demanded the immediate withdrawal of all foreign military personnel present in the Republic of Cyprus in contravention of paragraph 1 of the United Nations Charter.

The United Nations Security Council Resolution 360 adopted on 16 August 1974 declared their respect for the sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of the Republic of Cyprus, and formally recorded its disapproval of the unilateral military actions taken against it by Turkey.

Turkish Cypriot

Turkish Cypriot opinion quotesPresident

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Archbishop Makarios III, overthrown by the Greek Junta in the 1974 coup, who opposed immediate Enosis (union between Cyprus and Greece). Makarios described the coup which replaced him as "an invasion of Cyprus by Greece" in his speech to the UN security council and stated that there were "no prospects" of success in the talks aimed at resolving the situation between Greek and Turkish Cypriots, as long as the leaders of the coup, sponsored and supported by Greece, were in power.

In Resolution 573, the Council of Europe supported the legality of the first wave of the Turkish invasion that occurred in July 1974, as per Article 4 of the Guarantee Treaty of 1960

The Treaty of Guarantee is a treaty between Cyprus, Greece, Turkey, and the United Kingdom that was promulgated in 1960.

Article I bans Cyprus from participating in any political union or economic union with any other state. Article II requires ...

, which allows Turkey, Greece, and the United Kingdom to unilaterally intervene militarily in failure of a multilateral response to crisis in Cyprus.

Aftermath

Greek Cypriots who were unhappy with the United States not stopping the Turkish invasion took part in protests and riots in front of the American embassy. AmbassadorRodger Davies

Rodger Paul Davies (May 7, 1921 – August 19, 1974) was an American diplomat born in Berkeley, California, who was killed in the line of duty on August 19, 1974, in Nicosia, Cyprus, allegedly by Greek Cypriot gunmen during an anti-American demon ...

was assassinated during the protests by a sniper from the extremist EOKA-B

EOKA-B () was a Greek Cypriot paramilitary organisation formed in 1971 by General Georgios Grivas ("Digenis"). It followed an ultra right-wing nationalistic ideology and had the ultimate goal of achieving the ''enosis'' (union) of Cyprus with ...

group.

Declaration of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus

Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus

Northern Cyprus ( tr, Kuzey Kıbrıs), officially the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC; tr, Kuzey Kıbrıs Türk Cumhuriyeti, ''KKTC''), is a ''de facto'' state that comprises the northeastern portion of the island of Cyprus. Reco ...

. Immediately upon this declaration Britain convened a meeting of the United Nations Security Council to condemn the declaration as "legally invalid". United Nations Security Council Resolution 541

With United Nations Security Council resolution 541, adopted on 18 November 1983, after reaffirming Resolution 365 (1974) and Resolution 367 (1975), the Council considered Northern Cyprus' decision to declare independence legally invalid.

It ...

(1983) considered the "attempt to create the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus is invalid, and will contribute to a worsening of the situation in Cyprus". It went on to state that it "considers the declaration referred to above as legally invalid and calls for its withdrawal".

In the following year UN resolution 550 (1984) condemned the "exchange of Ambassadors" between Turkey and the TRNC and went on to add that the Security Council "considers attempts to settle any part of Varosha by people other than its inhabitants as inadmissible and calls for the transfer of this area to the administration of the United Nations".

Neither Turkey nor the TRNC have complied with the above resolutions and Varosha remains uninhabited. In 2017, Varosha's beach was opened to be exclusively used by Turks (Turkish-Cypriots and Turkish nationals).

On 22 July 2010, United Nations' International Court of Justice decided that "International law contains no prohibition on declarations of independence". In response to this non-legally-binding direction, German Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle

Guido Westerwelle (; 27 December 1961 – 18 March 2016) was a German politician who served as Foreign Minister in the second cabinet of Chancellor Angela Merkel and Vice-Chancellor of Germany from 2009 to 2011, being the first openly gay person ...

said it "has nothing to do with any other cases in the world" including Cyprus, whereas some researchers stated the decision of ICJ provided the Turkish Cypriots an option to be used.

Ongoing negotiations

Greek Orthodox Church

The term Greek Orthodox Church ( Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the entire body of Orthodox (Chalcedonian) Christianity, sometimes also cal ...

urged the Greek population to vote "no".

Greek Cypriots rejected the UN settlement plan

The Settlement Plan was an agreement between the ethnically Saharawi Polisario Front and Morocco on the organization of a referendum, which would constitute an expression of self-determination for the people of Western Sahara, leading either to ...

in an April 2004 referendum. On 24 April 2004, the Greek Cypriots rejected by a three-to-one margin the plan proposed by UN Secretary-General

The secretary-general of the United Nations (UNSG or SG) is the chief administrative officer of the United Nations and head of the United Nations Secretariat, one of the six principal organs of the United Nations.

The role of the secretary- ...

Kofi Annan

Kofi Atta Annan (; 8 April 193818 August 2018) was a Ghanaian diplomat who served as the seventh secretary-general of the United Nations from 1997 to 2006. Annan and the UN were the co-recipients of the 2001 Nobel Peace Prize. He was the founde ...

for the settlement of the Cyprus dispute. The plan, which was approved by a two-to-one margin by the Turkish Cypriots in a separate but simultaneous referendum, would have created a United Cyprus Republic and ensured that the entire island would reap the benefits of Cyprus's entry into the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been de ...

on 1 May. The plan would have created a United Cyprus Republic consisting of a Greek Cypriot constituent state and a Turkish Cypriot constituent state linked by a federal government. More than half of the Greek Cypriots who were displaced in 1974 and their descendants would have had their properties returned to them and would have lived in them under Greek Cypriot administration within a period of 3.5 to 42 months after the entry into force

In law, coming into force or entry into force (also called commencement) is the process by which legislation, regulations, treaties and other legal instruments come to have legal force and effect. The term is closely related to the date of this ...

of the settlement. For those whose property could not be returned, they would have received monetary compensation.

The entire island entered the EU on 1 May 2004 still divided, although the EU

The entire island entered the EU on 1 May 2004 still divided, although the EU acquis communautaire

The Community acquis or ''acquis communautaire'' (; ), sometimes called the EU acquis and often shortened to acquis, is the accumulated legislation, legal acts and court decisions that constitute the body of European Union law that came into b ...