1924 United States presidential election on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 1924 United States presidential election was the 35th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 4, 1924. In a three-way contest, incumbent

;Republican candidates

File:John Calvin Coolidge, Bain bw photo portrait.jpg,

File:Souvenir_of_the_unveiling,_dedication_and_presentation_of_the_Abraham_Lincoln_G._A._R._memorial_monument_-_dedicated_to_the_veterans_of_the_Civil_War,_1861-1865,_at_Long_Beach,_California,_July_3rd,_(14576262447).jpg,

File:Robert La Follette Sr crop.jpg,

File:Frank O Lowden portrait.jpg,

When Coolidge became president, he was fortunate to have had a stable cabinet that remained untarnished by the scandals of the Harding administration. He won public confidence by taking a hand in settling a serious Pennsylvania coal strike, even though much of the negotiation's success was largely due to the state's governor,  Coolidge decided to head off the immediate threat of Johnson's candidacy by gaining the endorsement of some of the liberals. He first approached Senator

Coolidge decided to head off the immediate threat of Johnson's candidacy by gaining the endorsement of some of the liberals. He first approached Senator  Through the power of patronage Coolidge consolidated his hold over Republican officeholders and office-seekers in the South, where the party was made up of little more than those whose positions were awarded through such a system. This allowed him to gain control of Southern delegates to the coming Republican convention. He also let it be known that his

Through the power of patronage Coolidge consolidated his hold over Republican officeholders and office-seekers in the South, where the party was made up of little more than those whose positions were awarded through such a system. This allowed him to gain control of Southern delegates to the coming Republican convention. He also let it be known that his  To head off the Johnson threat, such as it was, Coolidge used the familiar weapons of his office. Through patronage threats he persuaded Senator James Watson of Indiana to take his own favorite-son candidacy out of the race; the decision was announced on January 11 after Watson met with William Butler, the President's campaign manager. To seal the Indiana factions in common cause, Butler made Colonel Carmi Thompson from Cleveland, Ohio associate manager for Coolidge's pre-convention campaign. On January 16 steps were taken to enter Coolidge in Johnson's own California primary. Two days after that, Coolidge received the endorsement of the anti-prohibitionist Nicholas M. Butler, president of

To head off the Johnson threat, such as it was, Coolidge used the familiar weapons of his office. Through patronage threats he persuaded Senator James Watson of Indiana to take his own favorite-son candidacy out of the race; the decision was announced on January 11 after Watson met with William Butler, the President's campaign manager. To seal the Indiana factions in common cause, Butler made Colonel Carmi Thompson from Cleveland, Ohio associate manager for Coolidge's pre-convention campaign. On January 16 steps were taken to enter Coolidge in Johnson's own California primary. Two days after that, Coolidge received the endorsement of the anti-prohibitionist Nicholas M. Butler, president of  The platform also came under special consideration in the weeks before the convention. Some Republican liberals threatened to support La Follette's third party ticket if the document omitted certain planks. Other problems faced the Platform Committee: the veterans' bonus, tax reform, Chinese immigration, and the World Court — all issues that cut at least one extremity from the main body of the party. Heading up the Committee on Resolutions, which was enjoined to formulate the party platform, was Charles B. Warren. In fact, however, much of the actual drafting fell to a subcommittee of the national committee, with vice-chairman Ralph Williams of Oregon as its head.

Nicholas M. Butler suggested that the platform consist of twelve to fifteen crisp sentences written by President Coolidge. It did indeed turn out to be a short and noncontroversial document. No mention was made of the Ku Klux Klan, and faint praise was given to hopeful plans for joining the World Court and helping the farmer. Apparently the party thought that traditional Republican strength in the areas affected by crop failure and low prices could accommodate a mild rebellion without loss of the section's electoral votes. The platform spoke of Coolidge's "practical idealism"; it also observed apologetically that "time has been too short for the correction of all the ills we received as a heritage from the last Democratic Administration." It proposed a conference on "the use of submarines and poison gas." Though the document was drafted by a new breed of Republican such as Ogden Mills from New York - who even recommended the adoption of an anti-Klan plank - rather than party stalwarts like Senator

The platform also came under special consideration in the weeks before the convention. Some Republican liberals threatened to support La Follette's third party ticket if the document omitted certain planks. Other problems faced the Platform Committee: the veterans' bonus, tax reform, Chinese immigration, and the World Court — all issues that cut at least one extremity from the main body of the party. Heading up the Committee on Resolutions, which was enjoined to formulate the party platform, was Charles B. Warren. In fact, however, much of the actual drafting fell to a subcommittee of the national committee, with vice-chairman Ralph Williams of Oregon as its head.

Nicholas M. Butler suggested that the platform consist of twelve to fifteen crisp sentences written by President Coolidge. It did indeed turn out to be a short and noncontroversial document. No mention was made of the Ku Klux Klan, and faint praise was given to hopeful plans for joining the World Court and helping the farmer. Apparently the party thought that traditional Republican strength in the areas affected by crop failure and low prices could accommodate a mild rebellion without loss of the section's electoral votes. The platform spoke of Coolidge's "practical idealism"; it also observed apologetically that "time has been too short for the correction of all the ills we received as a heritage from the last Democratic Administration." It proposed a conference on "the use of submarines and poison gas." Though the document was drafted by a new breed of Republican such as Ogden Mills from New York - who even recommended the adoption of an anti-Klan plank - rather than party stalwarts like Senator

Democratic candidates:

Democratic candidates:

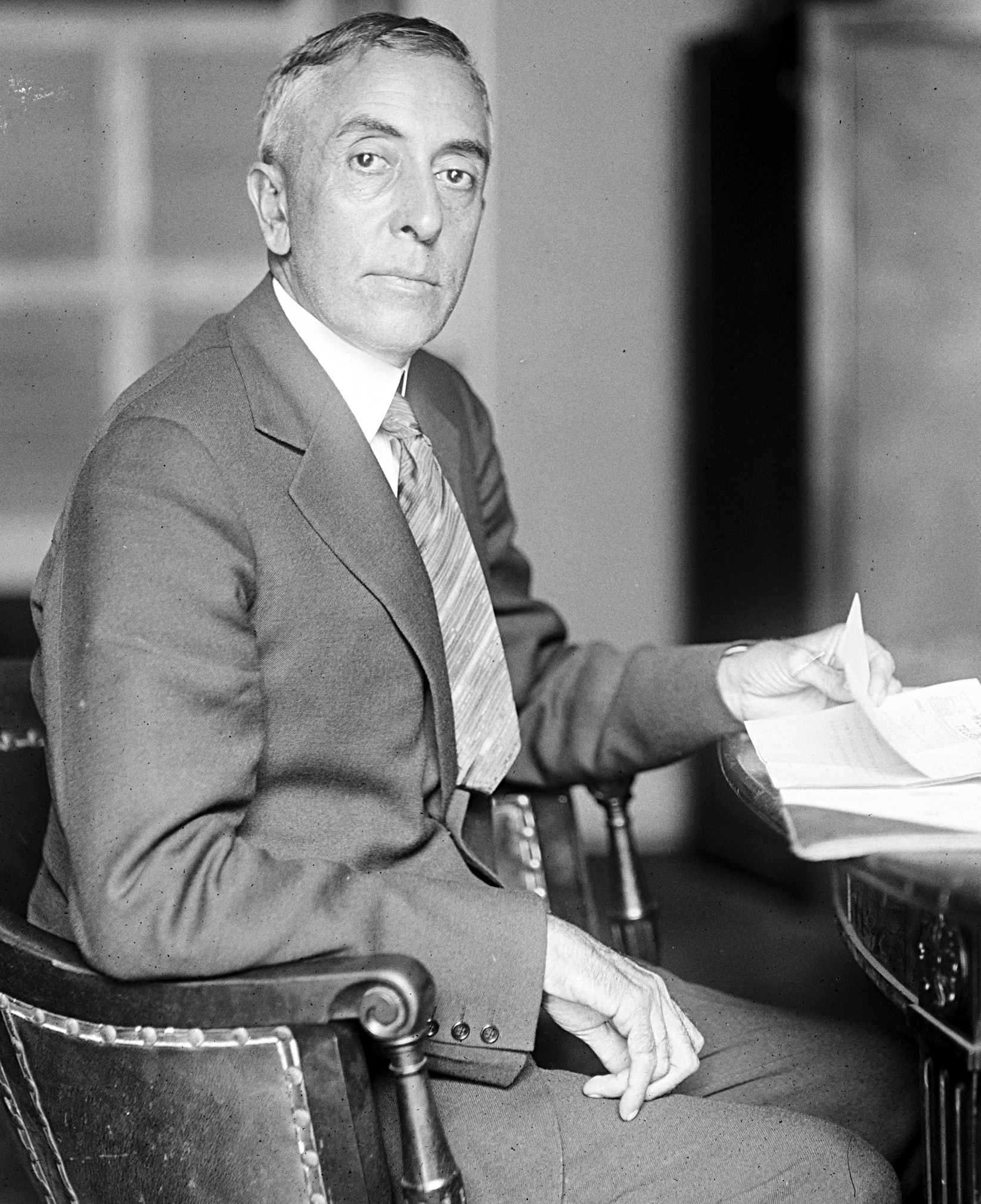

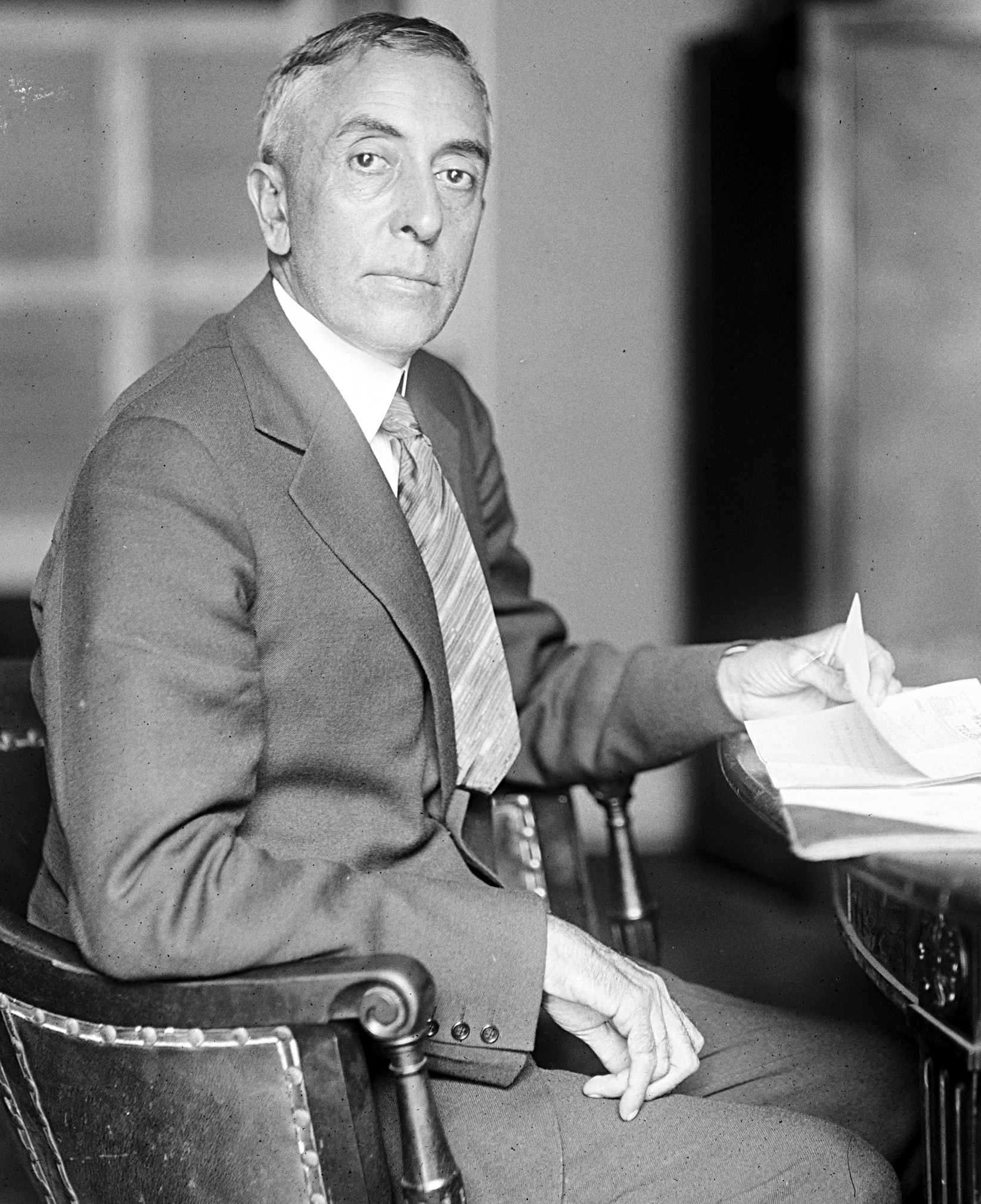

File:John William Davis.jpg,

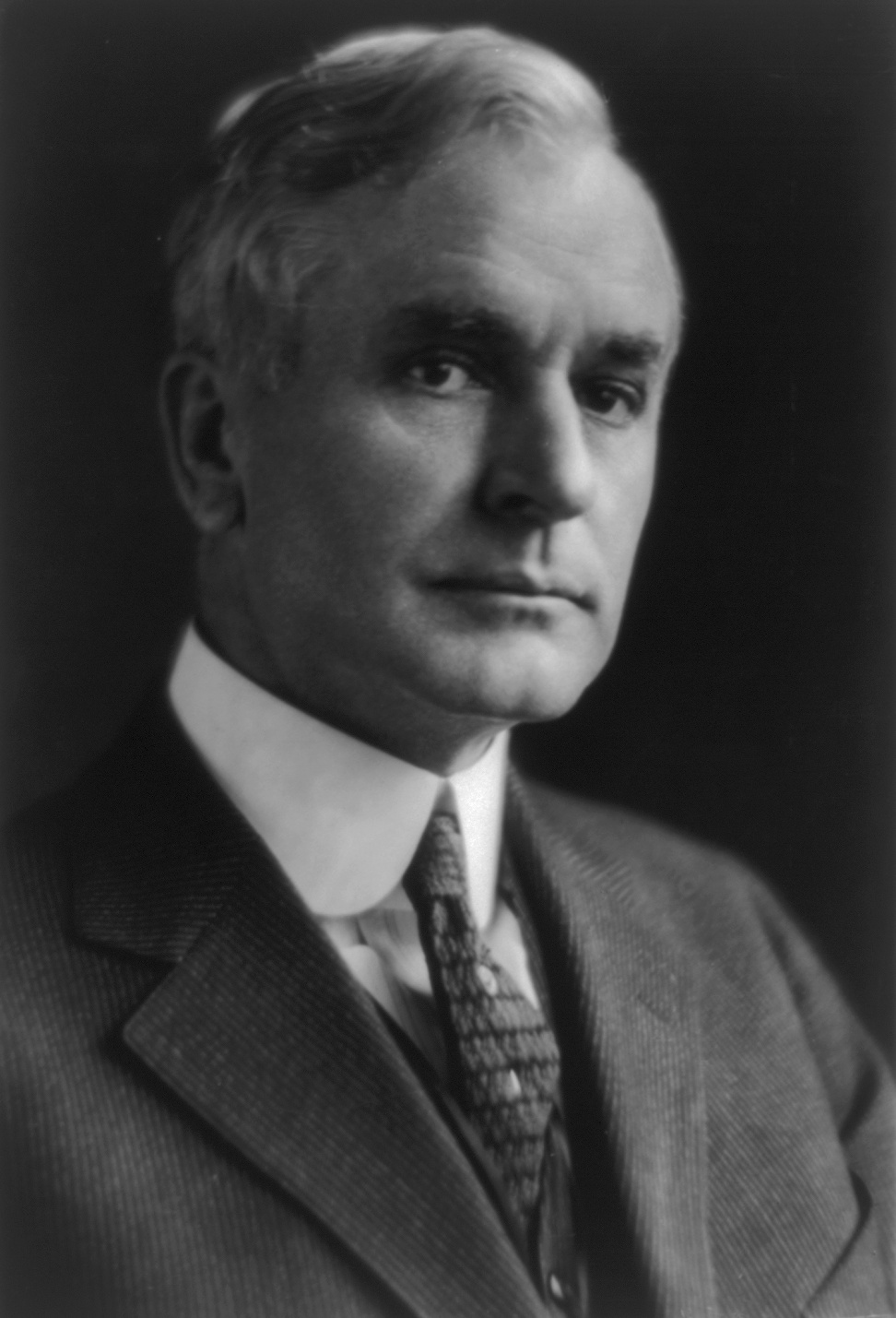

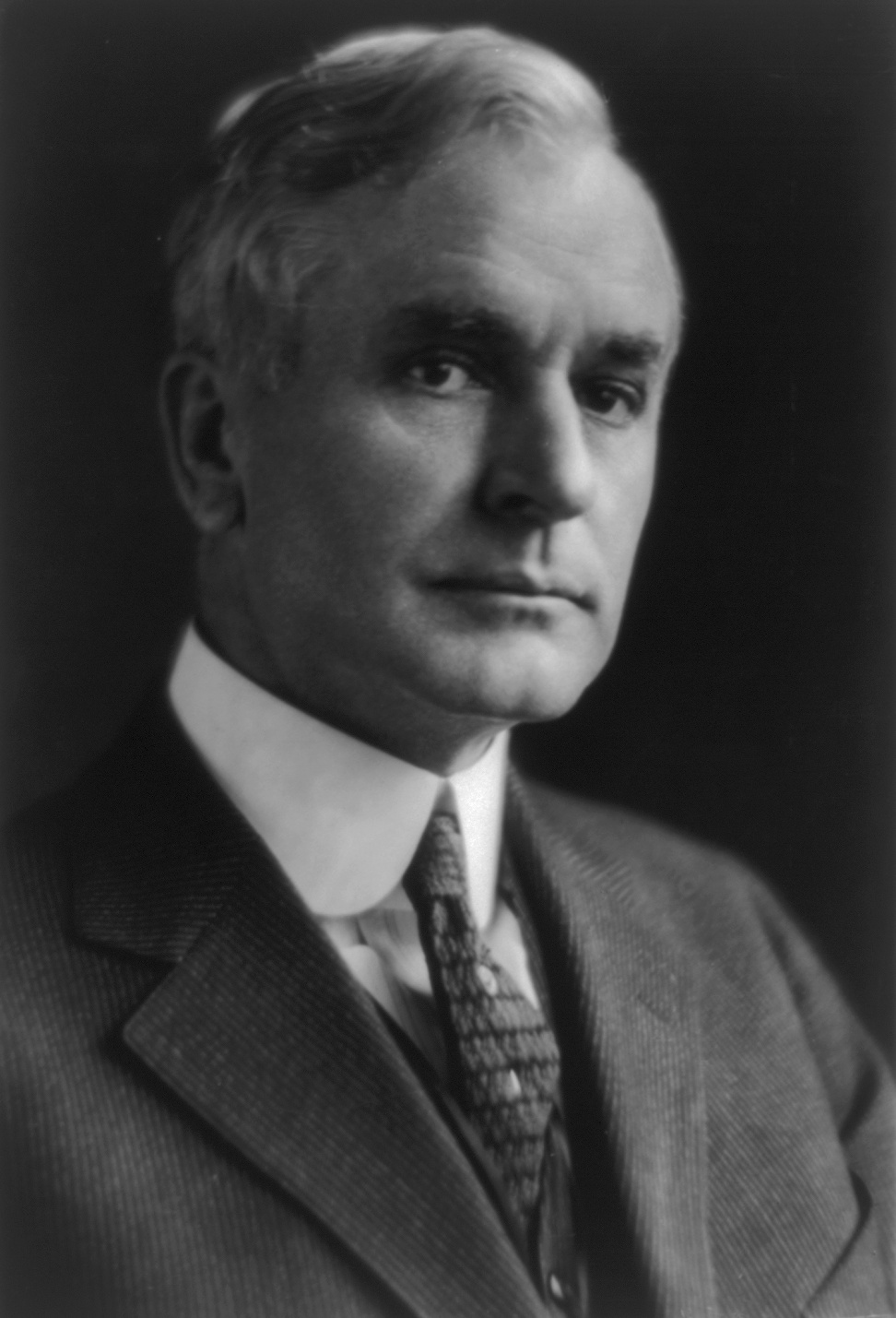

File:William Gibbs McAdoo, formal photo portrait, 1914.jpg,

File:AlfredSmith.png,

File:Oscar W. Underwood.jpg,

Sizable Democratic gains during the 1922 Midterm elections suggested to many Democrats that the nadir they experienced immediately following the 1920 elections was ending, and that a popular candidate like

Sizable Democratic gains during the 1922 Midterm elections suggested to many Democrats that the nadir they experienced immediately following the 1920 elections was ending, and that a popular candidate like

McAdoo's connection to Doheny appeared to seriously lessen his desirability as a presidential candidate. In February

McAdoo's connection to Doheny appeared to seriously lessen his desirability as a presidential candidate. In February  More directly, the contest between McAdoo and Smith thrust upon the Democratic national convention a dilemma of a kind no politician would wish to confront. To reject McAdoo and nominate Smith would solidify anti-Catholic feeling and rob the party of millions of otherwise certain votes in the South and elsewhere. But to reject Smith and nominate McAdoo would antagonize American Catholics, who constituted some 16 percent of the population and most of whom could normally be counted upon by the Democrats. Either selection would affect significantly the future of the party. Now in the ostensibly neutral hands of Cordell Hull, the Democratic national convention chairman, party machinery was expected to shift to the victor in the convention, and a respectable run in the fall election would ensure the victor's continued supremacy in Democratic politics.

The selection of New York as the site for the 1924 convention was based in part on the recent success of the party; in 1922 thirteen Republican congressmen from the state had lost their seats. New York City had not been chosen for a convention since 1868. Wealthy New Yorkers, who had outbid other cities, declared their purpose "to convince the rest of the country that the town was not the red-light menace generally conceived by the sticks." Though dry organizations opposed the choice of New York, it won McAdoo's grudging consent in the fall of 1923, before the oil scandals made Smith a serious threat to him. McAdoo's own adopted state, California, had played host to the Democrats in 1920.

The

More directly, the contest between McAdoo and Smith thrust upon the Democratic national convention a dilemma of a kind no politician would wish to confront. To reject McAdoo and nominate Smith would solidify anti-Catholic feeling and rob the party of millions of otherwise certain votes in the South and elsewhere. But to reject Smith and nominate McAdoo would antagonize American Catholics, who constituted some 16 percent of the population and most of whom could normally be counted upon by the Democrats. Either selection would affect significantly the future of the party. Now in the ostensibly neutral hands of Cordell Hull, the Democratic national convention chairman, party machinery was expected to shift to the victor in the convention, and a respectable run in the fall election would ensure the victor's continued supremacy in Democratic politics.

The selection of New York as the site for the 1924 convention was based in part on the recent success of the party; in 1922 thirteen Republican congressmen from the state had lost their seats. New York City had not been chosen for a convention since 1868. Wealthy New Yorkers, who had outbid other cities, declared their purpose "to convince the rest of the country that the town was not the red-light menace generally conceived by the sticks." Though dry organizations opposed the choice of New York, it won McAdoo's grudging consent in the fall of 1923, before the oil scandals made Smith a serious threat to him. McAdoo's own adopted state, California, had played host to the Democrats in 1920.

The  It had seemed for a time that the nomination could go to Samuel Ralston, an Indiana senator and popular former governor. Advanced by the indefatigable boss

It had seemed for a time that the nomination could go to Samuel Ralston, an Indiana senator and popular former governor. Advanced by the indefatigable boss

This was the first presidential election in which all American Indians were recognized as citizens and allowed to vote.

The total vote increased 2,300,000 but, because of the great drawing power of the La Follette candidacy, both the Republican and Democratic totals were less. Largely because of the deep inroads made by La Follette in the Democratic vote, Davis polled 750,000 fewer votes than were cast for Cox in 1920. Coolidge polled 425,000 votes less than Harding had in 1920. Nonetheless, La Follette's appeal among liberal Democrats allowed Coolidge to achieve a 25.2 percent margin of victory over Davis in the popular vote (the second largest since 1824, and the largest in the last century). Davis's popular vote percentage of 28.8% remains the lowest of any Democratic presidential candidate (not counting

This was the first presidential election in which all American Indians were recognized as citizens and allowed to vote.

The total vote increased 2,300,000 but, because of the great drawing power of the La Follette candidacy, both the Republican and Democratic totals were less. Largely because of the deep inroads made by La Follette in the Democratic vote, Davis polled 750,000 fewer votes than were cast for Cox in 1920. Coolidge polled 425,000 votes less than Harding had in 1920. Nonetheless, La Follette's appeal among liberal Democrats allowed Coolidge to achieve a 25.2 percent margin of victory over Davis in the popular vote (the second largest since 1824, and the largest in the last century). Davis's popular vote percentage of 28.8% remains the lowest of any Democratic presidential candidate (not counting

Image:1924 United States presidential election results map by county.svg, Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

Image:PresidentialCounty1924Colorbrewer.gif, Map of presidential election results by county

Image:RepublicanPresidentialCounty1924Colorbrewer.gif, Map of Republican presidential election results by county

Image:DemocraticPresidentialCounty1924Colorbrewer.gif, Map of Democratic presidential election results by county

Image:OtherPresidentialCounty1924Colorbrewer.gif, Map of "other" presidential election results by county

Image:CartogramPresidentialCounty1924Colorbrewer.gif,

online

*Craig, Douglas B. ''After Wilson: The Struggle for the Democratic Party, 1920-1934'' (1993) * Davies, Gareth, and Julian E. Zelizer, eds. ''America at the Ballot Box: Elections and Political History'' (2015) pp. 139–52. * * Goldberg, David J. "Unmasking the Ku Klux Klan: The northern movement against the KKK, 1920-1925." ''Journal of American Ethnic History'' (1996): 32-4

online

* * McVeigh, Rory. "Power Devaluation, the Ku Klux Klan, and the Democratic National Convention of 1924." ''Sociological Forum'' 16#1 (2001

abstract

* * Martinson, David L. "Coverage of La Follette Offers Insights for 1972 Campaign." ''Journalism Quarterly'' 52.3 (1975): 539–542. * * Prude, James C. "William Gibbs McAdoo and the Democratic National Convention of 1924." ''Journal of Southern History'' 38.4 (1972): 621-62

online

* Ranson, Edward. ''The Role of Radio in the American Presidential Election of 1924: How a New Communications Technology Shapes the Political Process'' (Edwin Mellen Press; 2010) 165 pages. Looks at Coolidge as a radio personality, and how radio figured in the campaign, the national conventions, and the election result. * Tucker, Garland S., III. ''The high tide of American conservatism: Davis, Coolidge, and the 1924 election'' (2010

online

*

online

* Porter, Kirk H. and Donald Bruce Johnson, eds. ''National party platforms, 1840-1964'' (1965

online 1840-1956

Election of 1924 in Counting the Votes

{{Authority control Presidency of Calvin Coolidge Calvin Coolidge 1924 in American politics November 1924 events

Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Calvin Coolidge won election to a full term.

Coolidge had been vice president

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

under Warren G. Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party, he was one of the most popular sitting U.S. presidents. A ...

and became president in 1923 upon Harding's death. Coolidge was given credit for a booming economy at home and no visible crises abroad, and he faced little opposition at the 1924 Republican National Convention

Nineteen or 19 may refer to:

* 19 (number), the natural number following 18 and preceding 20

* one of the years 19 BC, AD 19, 1919, 2019

Films

* ''19'' (film), a 2001 Japanese film

* ''Nineteen'' (film), a 1987 science fiction film

Music ...

. The Democratic Party nominated former Congressman and ambassador to the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

John W. Davis

John William Davis (April 13, 1873 – March 24, 1955) was an American politician, diplomat and lawyer. He served under President Woodrow Wilson as the Solicitor General of the United States and the United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom ...

of West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the B ...

. Davis, a compromise candidate, triumphed on the 103rd ballot of the 1924 Democratic National Convention

The 1924 Democratic National Convention, held at the Madison Square Garden in New York City from June 24 to July 9, 1924, was the longest continuously running convention in United States political history. It took a record 103 ballots to nominat ...

after a deadlock between supporters of William Gibbs McAdoo

William Gibbs McAdoo Jr.McAdoo is variously differentiated from family members of the same name:

* Dr. William Gibbs McAdoo (1820–1894) – sometimes called "I" or "Senior"

* William Gibbs McAdoo (1863–1941) – sometimes called "II" or "Ju ...

and Al Smith. Dissatisfied by the conservatism

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

of both major party candidates, the Progressive Party Progressive Party may refer to:

Active parties

* Progressive Party, Brazil

* Progressive Party (Chile)

* Progressive Party of Working People, Cyprus

* Dominica Progressive Party

* Progressive Party (Iceland)

* Progressive Party (Sardinia), Ita ...

nominated Senator Robert La Follette of Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

.

In a 2010 book, Garland S. Tucker argues that the election marked the "high tide of American conservatism

Conservatism in the United States is a political and social philosophy based on a belief in limited government, individualism, traditionalism, republicanism, and limited federal governmental power in relation to U.S. states. Conservative ...

", as both major candidates campaigned for limited government, reduced taxes, and less regulation. By contrast, La Follette called for the gradual nationalization of the railroads and increased taxes on the wealthy.

Coolidge won a landslide victory, taking majorities in both the popular vote and the Electoral College and winning almost every state outside of the Solid South

The Solid South or Southern bloc was the electoral voting bloc of the states of the Southern United States for issues that were regarded as particularly important to the interests of Democrats in those states. The Southern bloc existed especial ...

. Coolidge is the last Republican to be elected president without winning any states that made up the former Confederacy. The election was the last time a Republican won the presidency without carrying Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

, Oklahoma, and Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

. La Follette won 16.6% of the popular vote, a strong showing for a third-party

Third party may refer to:

Business

* Third-party source, a supplier company not owned by the buyer or seller

* Third-party beneficiary, a person who could sue on a contract, despite not being an active party

* Third-party insurance, such as a Ve ...

candidate, while Davis won the lowest share of the popular vote of any Democratic nominee since Breckinridge in 1860, when the party split between a northern and southern ticket. This is the most recent election to date in which a third-party candidate won a non-southern state. This was also the US election with the lowest per capita voter turnout since records were kept.

Nominations

Republican Party nomination

;Republican candidates

Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot (August 11, 1865October 4, 1946) was an American forester and politician. He served as the fourth chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry, as the first head of the United States Forest Service, and as the 28th governor of Pennsy ...

. However, the more conservative factions within the Republican Party remained unconvinced in the new president's own conservatism, given his rather liberal record while governor of Massachusetts

The governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is the chief executive officer of the government of Massachusetts. The governor is the head of the state cabinet and the commander-in-chief of the commonwealth's military forces.

Massachuset ...

, and he had not even been their first choice for the vice presidency back in 1920; Senator Irvine Lenroot had been the choice of the party bosses then, but the delegates had rebelled. However, Coolidge was not popular with the liberal or progressive factions within the party either. Heartened by their victories in the 1922 midterms, the party's progressives vigorously opposed a continuation of the late Harding's policies. In the fall of 1923, Senator Hiram Johnson of California announced his intention of fighting Coolidge in the presidential primaries, and already friends of Senator Robert La Follette of Wisconsin were planning a third party.

Coolidge decided to head off the immediate threat of Johnson's candidacy by gaining the endorsement of some of the liberals. He first approached Senator

Coolidge decided to head off the immediate threat of Johnson's candidacy by gaining the endorsement of some of the liberals. He first approached Senator William Borah

William Edgar Borah (June 29, 1865 – January 19, 1940) was an outspoken Republican United States Senator, one of the best-known figures in Idaho's history. A progressive who served from 1907 until his death in 1940, Borah is often co ...

of Idaho and cultivated his circle by making a conciliatory reference to the Soviet Union in a speech in December. No sooner had the Soviet Union reacted favorably than Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes Sr. (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American statesman, politician and jurist who served as the 11th Chief Justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party, he previously was the ...

persuaded the President to reject it. This left Borah on the verge of deserting Coolidge, but the subsequent disclosure of corruption among the Establishment

''The Establishment'' is a term used to describe a dominant group or elite that controls a polity or an organization. It may comprise a closed social group that selects its own members, or entrenched elite structures in specific institution ...

persuaded him to stay and to try to convince Coolidge to align his policies more closely to his own. Coolidge for his part seemed unsure of what ideological posture to assume. His State of the Union address in January was neither liberal nor reactionary. He played Borah by repeatedly promising to fire Attorney General Harry Daugherty and putting it off. In a speech on Lincoln Day Coolidge promised unstinting prosecution that would not mingle the innocent and the guilty—and managed to keep Borah within his ranks until he no longer feared the senator's influence. By then, Coolidge had made himself sufficiently strong to replace not only corrupt officeholders but also many Republican stalwarts on the national committee and throughout the party hierarchy, elevating in their stead business friends loyal to him; Coolidge managed to create a conservative administration that had very little to do with the party establishment. In an effort to try to get at least some of the liberals back into the party ranks, he then offered the vice presidency to the popular Senator Borah. The senator declined, also refusing to nominate Coolidge at that year's Republican convention which he later decided against attending.

Another task for Coolidge, only slightly easier than tightening his hold over the party's divergent factions, was to rebuild the party organization. A few years before, Will Hays had brought disciplined energy to the office of Republican national chairman. Hays's replacement, William Butler, lacked his predecessor's experience, and it fell to Coolidge himself to whip the party into shape. His prime task was to establish control over the party in order to ensure his own nomination.

Through the power of patronage Coolidge consolidated his hold over Republican officeholders and office-seekers in the South, where the party was made up of little more than those whose positions were awarded through such a system. This allowed him to gain control of Southern delegates to the coming Republican convention. He also let it be known that his

Through the power of patronage Coolidge consolidated his hold over Republican officeholders and office-seekers in the South, where the party was made up of little more than those whose positions were awarded through such a system. This allowed him to gain control of Southern delegates to the coming Republican convention. He also let it be known that his secretary

A secretary, administrative professional, administrative assistant, executive assistant, administrative officer, administrative support specialist, clerk, military assistant, management assistant, office secretary, or personal assistant is a ...

Campbell Slemp, who favored the policy, would remove African-American Republican leaders in the South in order to attract more white voters to the party. Only California Senator Hiram Johnson challenged Coolidge in the South; Governor Frank Lowden of Illinois, potentially Coolidge's most dangerous rival for the nomination, was attending to his state after he had decided 1924 would probably be a Democratic year. When the early Alabama primary resulted in a slate contested between the Coolidge and Johnson forces, an administration-picked committee on delegates awarded Alabama to Coolidge.

Johnson formally opened his campaign for the presidential nomination in Cleveland, Ohio on January 2. He delivered a sharp attack on the Republican National Committee for increasing southern delegate representation in the national convention while also criticizing Coolidge for supplying arms to the Obregón forces in Mexico. "I shall not concede," he said "that collectors of revenue, U.S. Marshals, postmasters, and other officeholders may themselves alone nominate candidates for the Presidency." Johnson later condemned inefficient enforcement of prohibition and argued against Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon's plan to reduce taxes, which he said favored the wealthiest classes.

Johnson's drive began to falter almost as soon as it had begun. In appealing to the rank and file he moved even further away from the organization Republicans who would choose the nominee. Johnson, moreover, was too much a maverick for the conciliatory role demanded of a national political candidate. In the mid-1920s the major parties had little use for the nonconformists like Johnson or Governor Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot (August 11, 1865October 4, 1946) was an American forester and politician. He served as the fourth chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry, as the first head of the United States Forest Service, and as the 28th governor of Pennsy ...

of Pennsylvania, but Johnson in truth could not easily be placed in the political spectrum. He did oppose the administration's tax reduction program which favored higher income groups, but he spoke against the World Court as he had the League of Nations, opposed the sale of arms to liberal Obregón forces in Mexico, called for an end to all Chinese immigration, and joined the American Legion in calling for the immediate payment of the veterans' bonus.

To head off the Johnson threat, such as it was, Coolidge used the familiar weapons of his office. Through patronage threats he persuaded Senator James Watson of Indiana to take his own favorite-son candidacy out of the race; the decision was announced on January 11 after Watson met with William Butler, the President's campaign manager. To seal the Indiana factions in common cause, Butler made Colonel Carmi Thompson from Cleveland, Ohio associate manager for Coolidge's pre-convention campaign. On January 16 steps were taken to enter Coolidge in Johnson's own California primary. Two days after that, Coolidge received the endorsement of the anti-prohibitionist Nicholas M. Butler, president of

To head off the Johnson threat, such as it was, Coolidge used the familiar weapons of his office. Through patronage threats he persuaded Senator James Watson of Indiana to take his own favorite-son candidacy out of the race; the decision was announced on January 11 after Watson met with William Butler, the President's campaign manager. To seal the Indiana factions in common cause, Butler made Colonel Carmi Thompson from Cleveland, Ohio associate manager for Coolidge's pre-convention campaign. On January 16 steps were taken to enter Coolidge in Johnson's own California primary. Two days after that, Coolidge received the endorsement of the anti-prohibitionist Nicholas M. Butler, president of Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

. A little later, Governor Pinchot, who had lost control of his state party organization, earned a place in his state's delegation, further state patronage, and other concessions in exchange for his support of the President. By the end of the month the eastern states were clearly entrenched in their support of Coolidge. In Michigan, where Johnson had won the presidential preference campaign in 1920, Coolidge backers filed nominating petitions for an old man named Hiram Johnson, hoping to divide the anti-administration vote. This Johnson, who resided in Michigan's Upper Peninsula, planned no campaign.

But the California senator remained in the race; it is thought that he might have hoped his candidacy would force Coolidge to adopt a more progressive stance, especially in regards to corruption. Johnson for example was prominent in the movement that led Coolidge to fire Attorney General Daugherty and accept the resignation of Secretary of the Navy Edwin Denby. In an effort to offset Johnson's popularity in some of the farm states the president also increased the tariff on wheat, and made available further farm loans. His efforts paid off in the first presidential primary in North Dakota; Coolidge won, La Follette ran second, and Johnson was far behind La Follette. The radical vote was split with Coolidge winning only with a plurality however, and Johnson remained in the race. Later in March, Johnson barely nosed ahead of Coolidge in the South Dakota primary, where Johnson had the personal support of the popular Senator Peter Norbeck

Peter Norbeck (August 27, 1870December 20, 1936) was an American politician from South Dakota. After serving two terms as the ninth Governor of South Dakota, Norbeck was elected to three consecutive terms as a United States Senator. Norbeck was ...

. This would be the only primary Johnson would win. During April Coolidge defeated him in swift succession in Michigan, Illinois, Nebraska, Oklahoma, New Jersey and Ohio. Refusing to quit, Johnson allowed his campaign to limp along into early May; then Coolidge defeated Johnson even in his staunch progressive-Republican state of California, despite Coolidge's opposition to an outright ban on Chinese immigration.

In mid-May the official Coolidge headquarters opened in Cleveland, Ohio under the direction of William Butler, general manager of the Coolidge campaign. When Butler predicted that 1,066 of the 1,109 delegates would favor Coolidge, no one really doubted him, and the Republicans planned a king of outing, like the familiar business conventions, rather than a serious political encounter. The only remotely interesting event would be the choosing of a vice presidential candidate, Coolidge himself had not bothered to decide on a candidate; evidently he hoped Borah might still run but the other candidates were all acceptable to him. Circumstances affecting the two most recent occupants of that office however gave the dramatic illusion of the importance of the Vice-Presidency. When President Wilson fell ill in 1919 only a heartbeat kept the little-known Thomas R. Marshall

Thomas Riley Marshall (March 14, 1854 – June 1, 1925) was an American politician who served as the 28th vice president of the United States from 1913 to 1921 under President Woodrow Wilson. A prominent lawyer in Indiana, he became an acti ...

from becoming president. Then Harding's death sent Coolidge to the White House. A man of ability had to be chosen and one who would also bring strength to the ticket in areas where La Follette could potentially run well. When Senator Borah declined the honor, California Republicans started to boost Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

, who was credited with helping Coolidge triumph over Johnson in the state's presidential primary. Particularly since the narrow defeat of Charles E. Hughes in 1916, discovered only the day after the election when the final tallies were received from California, the state had been looked upon as important; the imminent candidacy of Robert La Follette, who would appeal to western liberals, made California all the more crucial. ''The New York Times'' thought Hoover would make an excellent choice, recognition at last that the vice president must be a man fitted for the presidency. Coolidge never spoke for Hoover and may have hoped he would remain in the cabinet where he was needed. As a dynamic vice president, Hoover would be too visibly the heir apparent for 1928; certainly he would overshadow the chief executive in an embarrassing way. Other candidates mentioned prominently included Governor Frank O. Lowden of Illinois, Governor Arthur M. Hyde of Missouri, and Charles G. Dawes

Charles Gates Dawes (August 27, 1865 – April 23, 1951) was an American banker, general, diplomat, composer, and Republican politician who was the 30th vice president of the United States from 1925 to 1929 under Calvin Coolidge. He was a co-reci ...

, author of the German war reparations payment plan. It was hoped that both the party's candidates would be chosen on Thursday, June 12, to avoid the necessity of naming the Vice President on Friday the 13th.

The platform also came under special consideration in the weeks before the convention. Some Republican liberals threatened to support La Follette's third party ticket if the document omitted certain planks. Other problems faced the Platform Committee: the veterans' bonus, tax reform, Chinese immigration, and the World Court — all issues that cut at least one extremity from the main body of the party. Heading up the Committee on Resolutions, which was enjoined to formulate the party platform, was Charles B. Warren. In fact, however, much of the actual drafting fell to a subcommittee of the national committee, with vice-chairman Ralph Williams of Oregon as its head.

Nicholas M. Butler suggested that the platform consist of twelve to fifteen crisp sentences written by President Coolidge. It did indeed turn out to be a short and noncontroversial document. No mention was made of the Ku Klux Klan, and faint praise was given to hopeful plans for joining the World Court and helping the farmer. Apparently the party thought that traditional Republican strength in the areas affected by crop failure and low prices could accommodate a mild rebellion without loss of the section's electoral votes. The platform spoke of Coolidge's "practical idealism"; it also observed apologetically that "time has been too short for the correction of all the ills we received as a heritage from the last Democratic Administration." It proposed a conference on "the use of submarines and poison gas." Though the document was drafted by a new breed of Republican such as Ogden Mills from New York - who even recommended the adoption of an anti-Klan plank - rather than party stalwarts like Senator

The platform also came under special consideration in the weeks before the convention. Some Republican liberals threatened to support La Follette's third party ticket if the document omitted certain planks. Other problems faced the Platform Committee: the veterans' bonus, tax reform, Chinese immigration, and the World Court — all issues that cut at least one extremity from the main body of the party. Heading up the Committee on Resolutions, which was enjoined to formulate the party platform, was Charles B. Warren. In fact, however, much of the actual drafting fell to a subcommittee of the national committee, with vice-chairman Ralph Williams of Oregon as its head.

Nicholas M. Butler suggested that the platform consist of twelve to fifteen crisp sentences written by President Coolidge. It did indeed turn out to be a short and noncontroversial document. No mention was made of the Ku Klux Klan, and faint praise was given to hopeful plans for joining the World Court and helping the farmer. Apparently the party thought that traditional Republican strength in the areas affected by crop failure and low prices could accommodate a mild rebellion without loss of the section's electoral votes. The platform spoke of Coolidge's "practical idealism"; it also observed apologetically that "time has been too short for the correction of all the ills we received as a heritage from the last Democratic Administration." It proposed a conference on "the use of submarines and poison gas." Though the document was drafted by a new breed of Republican such as Ogden Mills from New York - who even recommended the adoption of an anti-Klan plank - rather than party stalwarts like Senator Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850 November 9, 1924) was an American Republican politician, historian, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served in the United States Senate from 1893 to 1924 and is best known for his positions on foreign policy. ...

from Massachusetts or Senator George Pepper from Pennsylvania, it remained conservative in its blandness. A substitute platform presented by Wisconsin progressives caught a moral tone the other failed to embody, but was defeated without a vote.

The convention formally ran from June 10 to 12. No questions arose over the choice of the presidential nominee. After the delegates tried unsuccessfully to prevail on Governor Frank Lowden of Illinois to run for the vice presidency — they actually nominated him but he declined — Charles G. Dawes won the nomination on the third ballot. He defeated Herbert Hoover, the choice of National Chairman Butler, by 682 votes to 234. Both candidates suffered from unpopularity with one major group of voters: Dawes with organized labor for his opposition to certain strikes, Hoover with wheat farmers for his role in price fixing during the war. Hoover lost because most convention leaders were more sensitive to the farm vote than that of labor, and because the president had not endorsed him. Dawes, a fiery brigadier general of World War I, now fifty-nine years old (seven years older than Coolidge), was well received by the convention and by Republicans generally. No doubt the establishment would have preferred a man of quieter disposition such as Senator Charles Curtis

Charles Curtis (January 25, 1860 – February 8, 1936) was an American attorney and Republican politician from Kansas who served as the 31st vice president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 under Herbert Hoover. He had served as the Sena ...

from Kansas, but Dawes's denunciation of the closed shop pleased them. Since Coolidge had not strongly supported any candidate, congressional leaders and party rebels agreed that "Hell'n Maria" Dawes, who had denounced "pinhead" politicians before a congressional investigating committee, was available and a strong candidate. His familiarity with the West, which would be the battleground of the campaign, gave needed strength to a ticket headed by a conservative easterner. German-Americans, who could be expected to support La Follette in large numbers, liked Dawes in particular for helping to solve postwar difficulties in Germany through his service on the Reparations Commission. He was billed as the active member of the ticket who would carry on the partisan campaign for Coolidge, much as Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

would do for the incumbent Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

in 1956. In an episode also suggestive of Nixon's career, a scandal was raised against Dawes. A dozen years earlier his bank had briefly loaned a banker friend named Lorimer, who had been expelled from the United States Senate, over a million dollars for the purpose of satisfying a state banking law; eventually, Lorimer's bank failed, but in 1924 this issue did not resonate with the voters.

Democratic Party nomination

Democratic candidates:

Democratic candidates:

Sizable Democratic gains during the 1922 Midterm elections suggested to many Democrats that the nadir they experienced immediately following the 1920 elections was ending, and that a popular candidate like

Sizable Democratic gains during the 1922 Midterm elections suggested to many Democrats that the nadir they experienced immediately following the 1920 elections was ending, and that a popular candidate like William Gibbs McAdoo

William Gibbs McAdoo Jr.McAdoo is variously differentiated from family members of the same name:

* Dr. William Gibbs McAdoo (1820–1894) – sometimes called "I" or "Senior"

* William Gibbs McAdoo (1863–1941) – sometimes called "II" or "Ju ...

from California, who could draw the popular support of labor and Wilsonian

Wilsonianism, or Wilsonian idealism, is a certain type of foreign policy advice. The term comes from the ideas and proposals of President Woodrow Wilson. He issued his famous Fourteen Points in January 1918 as a basis for ending World War I and p ...

s, would stand an excellent chance of winning the coming presidential election. The Teapot Dome scandal

The Teapot Dome scandal was a bribery scandal involving the administration of United States President Warren G. Harding from 1921 to 1923. Secretary of the Interior Albert Bacon Fall had leased Navy petroleum reserves at Teapot Dome in Wyomi ...

added yet even more enthusiasm for party initially, though further disclosures revealed that the corrupt interests had been bipartisan; Edward Doheny for example, whose name had become synonymous with that of the Teapot Dome scandal, ranked highly in the Democratic party of California, contributing highly to party campaigns, served as chairman of the state party, and was even at one point advanced as a possible candidate for vice-president in 1920. The death of Warren Harding in August 1923 and the succession of Coolidge blunted the effects of the scandals upon the Republican party, including that of Teapot Dome, but up until and into the convention many Democrats believed that the Republicans would be turned out of the White House.

The immediate leading candidate of the Democratic party was William Gibbs McAdoo

William Gibbs McAdoo Jr.McAdoo is variously differentiated from family members of the same name:

* Dr. William Gibbs McAdoo (1820–1894) – sometimes called "I" or "Senior"

* William Gibbs McAdoo (1863–1941) – sometimes called "II" or "Ju ...

, now sixty years old, who was extremely popular with labor thanks to his wartime record as Director General of the railroads and was, as former President Wilson's son-in-law, also the favorite of the Wilsonians. However, in January 1924, unearthed evidence of his relationship with Doheny discomforted many of his supporters. After McAdoo had resigned from the Wilson Administration in 1918, Joseph Tumulty, Wilson's secretary, had warned him to avoid association with Doheny. However, in 1919, McAdoo took Doheny as a client for an unusually large initial fee of $100,000, in addition to an annual retainer. Not the least perplexing part of the deal involved a million dollar bonus for McAdoo if the Mexican government reach a satisfactory agreement with Washington on oil lands Doheny held south of the Texas border. The bonus was never paid and McAdoo insisted later that it was a casual figure of speech mentioned in jest. At the time, however, he had telegraphed the New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 until 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers. It was a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under pub ...

that he would have received "an additional fee of $900,000 if my firm had succeeded in getting a satisfactory settlement," since the Doheny companies had "several hundred million dollars of property at stake, our services, had they been effective, would have been rightly compensated by the additional fee." In fact, the lawyer received only $50,000 more from Doheny. It was also charged that on matters of interest to his client, Republic Iron and Steel, from whom he received $150,000, McAdoo neglected the regular channels dictated by propriety and consulted directly with his own appointees in the capital to obtain a fat refund.

McAdoo's connection to Doheny appeared to seriously lessen his desirability as a presidential candidate. In February

McAdoo's connection to Doheny appeared to seriously lessen his desirability as a presidential candidate. In February Colonel House

Edward Mandell House (July 26, 1858 – March 28, 1938) was an American diplomat, and an adviser to President Woodrow Wilson. He was known as Colonel House, although his rank was honorary and he had performed no military service. He was a highl ...

urged him to withdraw from the race, as did Josephus Daniels, Thomas Bell Love, and two important contributors to the Democratic party, Bernard Baruch and Thomas Chadbourne. Some advisers hoped that McAdoo's chances would improve after a formal withdrawal. William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the Democratic Party, running three times as the party's nominee for President ...

, who never doubted McAdoo's honesty, thought that the Doheny affair had damaged the lawyer's chances "seriously, if not fatally." Senator Thomas Walsh, who earlier had called McAdoo the greatest Secretary of the Treasury since Alexander Hamilton, informed him with customary curtness: "You are no longer available as a candidate." Breckinridge Long

Samuel Miller Breckinridge Long (May 16, 1881 – September 26, 1958) was an American diplomat and politician. He served in the administrations of Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He is infamous among Holocaust historians for makin ...

, who would be McAdoo's floor manager at the June convention, wrote in his diary on February 13: "As it stands today we are beat." The New York Times, itself convinced that McAdoo had acted in bad taste and against the spirit of the law, reported the widespread opinion that McAdoo had "been eliminated as a formidable contender for Democratic nomination."

McAdoo was unpopular for reasons other than his close association with Doheny. Even in 1918, The Nation

''The Nation'' is an American liberal biweekly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper t ...

was saying that "his election to the White House would be an unqualified misfortune." McAdoo, the liberal journal then believed, had wanted to go to war with Mexico ''and'' Germany, and he was held responsible for segregating clerks in the Treasury Department. Walter Lippmann

Walter Lippmann (September 23, 1889 – December 14, 1974) was an American writer, reporter and political commentator. With a career spanning 60 years, he is famous for being among the first to introduce the concept of Cold War, coining the te ...

wrote in 1920 that McAdoo "is not fundamentally moved by the simple moralities," and that his "honest" liberalism catered only to popular feeling. Liberal critics, believing him a demagogue, gave as evidence his stand for quick payment of the veterans' bonus.

Much of the dissatisfaction with McAdoo on the part of reformers and urban Democrats sprang from his acceptance of the backing of the Ku Klux Klan. James Cox, the 1920 Democratic nominee, indignantly wrote that "there was not only tacit consent to the Klan's support, but it was apparent that he and his major supporters were conniving with the Klan." Friends insisted that McAdoo's silence on the matter hid a distaste that the political facts of life kept him from expressing, and especially after the Doheny scandal when he desperately needed support. Thomas Bell Love of Texas - though at one time of a contrary opinion - advised McAdoo not to issue even a mild disclaimer of the Klan. To Bernard Baruch and others, McAdoo explained as a disavowal of the Klan his remarks against prejudice at a 1923 college commencement. But McAdoo could not command the support of unsatisfied liberal spokesmen for The Nation and The New Republic

''The New Republic'' is an American magazine of commentary on politics, contemporary culture, and the arts. Founded in 1914 by several leaders of the progressive movement, it attempted to find a balance between "a liberalism centered in hu ...

, who favored the candidacy of the Republican Senator Robert La Follette. A further blow to McAdoo was the death on February 3, 1924, of Woodrow Wilson, who ironically had outlived his successor in the White House. Father-in-law to the candidate, Wilson might have given McAdoo a welcome endorsement now that the League of Nations had receded as an issue. William Dodd of the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chic ...

wrote to his father that Wilson had been "counting on" his daughter's being in the White House. The New York Times however reported a rumor that Wilson had written to Cox hoping he would again be a candidate in 1924.

McAdoo received support from the Ku Klux Klan and refused to answer questions on if he was a member of the organization. McAdoo's supporters later controlled the platform committee at the convention and voted against adding a condemnation of the KKK to the platform. He defeated Oscar Underwood

Oscar Wilder Underwood (May 6, 1862 – January 25, 1929) was an American lawyer and politician from Alabama, and also a candidate for President of the United States in 1912 and 1924. He was the first formally designated floor leader in the Unit ...

, who opposed the KKK and Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcohol ...

, in the Georgia primary and split the Alabama delegation. Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that ...

, who was seen as a threat to McAdoo, chose to not run for the nomination.

In their immediate effects the heated primary contests drew to McAdoo the financial support of the millionaires Thomas Chadbourne and Bernard Baruch (who was indebted to McAdoo for his appointment as head of the War Industries Board); and they strengthened the resolve of Governor Smith, ten years younger than McAdoo, to make a serious try for the nomination, which he had originally sought primarily to block McAdoo on the behalf of the eastern political bosses. The contests also hardened the antagonisms between the candidates, and cut deeper divisions within the electorate. In doing this, they undoubtedly retrieved lost ground for McAdoo and broadened his previously shrinking base of support, drawing to him rural, Klan, and dry elements awakened by the invigorated candidacy of Smith. Senator Kenneth McKellar from Tennessee wrote to his sister Nellie: "I see McAdoo carried Georgia by such an overwhelming majority that it is likely to reinstate him in the running." The Klan seemed to oppose every Democratic candidate except McAdoo. A Klan newspaper rejected Ford because he had given a Lincoln car to a Catholic archbishop; it flatly rejected Smith as a Catholic from "Jew York"; and it called Underwood the "Jew, jug, Jesuit candidate." The primaries therefore played their part in crystallizing the split within the party that would tear it apart at the forthcoming convention. Urban immigrants and McAdoo progressives had earlier joined to fight the Mellon tax plans in Congress, since both groups represented people of small means; deeper social animosities dissolved their alliance, and the urban-rural division rapidly supplanted all others. Frank Walsh

Francis Henry Walsh (6 July 1897 – 18 May 1968) was the 34th Premier of South Australia from 10 March 1965 to 1 June 1967, representing the South Australian Branch of the Australian Labor Party.

Early life

One of eight children, Walsh was b ...

, a progressive New York lawyer, wrote: "If his mith'sreligion is a bar, of course it is all right with me to bust up the Democratic party on such an issue."

More directly, the contest between McAdoo and Smith thrust upon the Democratic national convention a dilemma of a kind no politician would wish to confront. To reject McAdoo and nominate Smith would solidify anti-Catholic feeling and rob the party of millions of otherwise certain votes in the South and elsewhere. But to reject Smith and nominate McAdoo would antagonize American Catholics, who constituted some 16 percent of the population and most of whom could normally be counted upon by the Democrats. Either selection would affect significantly the future of the party. Now in the ostensibly neutral hands of Cordell Hull, the Democratic national convention chairman, party machinery was expected to shift to the victor in the convention, and a respectable run in the fall election would ensure the victor's continued supremacy in Democratic politics.

The selection of New York as the site for the 1924 convention was based in part on the recent success of the party; in 1922 thirteen Republican congressmen from the state had lost their seats. New York City had not been chosen for a convention since 1868. Wealthy New Yorkers, who had outbid other cities, declared their purpose "to convince the rest of the country that the town was not the red-light menace generally conceived by the sticks." Though dry organizations opposed the choice of New York, it won McAdoo's grudging consent in the fall of 1923, before the oil scandals made Smith a serious threat to him. McAdoo's own adopted state, California, had played host to the Democrats in 1920.

The

More directly, the contest between McAdoo and Smith thrust upon the Democratic national convention a dilemma of a kind no politician would wish to confront. To reject McAdoo and nominate Smith would solidify anti-Catholic feeling and rob the party of millions of otherwise certain votes in the South and elsewhere. But to reject Smith and nominate McAdoo would antagonize American Catholics, who constituted some 16 percent of the population and most of whom could normally be counted upon by the Democrats. Either selection would affect significantly the future of the party. Now in the ostensibly neutral hands of Cordell Hull, the Democratic national convention chairman, party machinery was expected to shift to the victor in the convention, and a respectable run in the fall election would ensure the victor's continued supremacy in Democratic politics.

The selection of New York as the site for the 1924 convention was based in part on the recent success of the party; in 1922 thirteen Republican congressmen from the state had lost their seats. New York City had not been chosen for a convention since 1868. Wealthy New Yorkers, who had outbid other cities, declared their purpose "to convince the rest of the country that the town was not the red-light menace generally conceived by the sticks." Though dry organizations opposed the choice of New York, it won McAdoo's grudging consent in the fall of 1923, before the oil scandals made Smith a serious threat to him. McAdoo's own adopted state, California, had played host to the Democrats in 1920.

The 1924 Democratic National Convention

The 1924 Democratic National Convention, held at the Madison Square Garden in New York City from June 24 to July 9, 1924, was the longest continuously running convention in United States political history. It took a record 103 ballots to nominat ...

was held from June 24 to July 9, and while there were a number of memorable moments, none were more crucial to the following proceedings then what occurred after a Platform Committee report on whether to censure the Ku Klux Klan by name came out. McAdoo controlled three of the four convention committees, including this one, and the majority report declared specifically against naming the Klan - although all the Committee members agreed on a general condemnation of bigotry and intolerance. Every effort was made to avoid the necessity of a direct commitment on the issue. Smith did not want to inflame the issue, but the proponents of his candidacy were anxious to identify McAdoo closely with the Klan and possibly to defeat him in a test of strength before the balloting began; the Smith faction, led by George Brennan of Illinois, therefore demanded that the specific denunciation of the Klan uttered by the committee minority become official.

William Jennings Bryan, whose aim was to keep the party together and to maintain harmony among his rural followers, argued that naming the Klan would popularize it, as had the publicity given the organization by the New York World. It was also good politics to avoid the issue, Bryan claimed, since naming it would irredeemably divide the party. Worse still, Bryan believed, denouncing the Klan by name would betray the McAdoo forces, since it had been the Smith camp's strategy to raise the issue. In contrast to Bryan, former mayor Andrew Erwin of Athens, Georgia, spoke for the anti-Klan plank. In the ensuing vote, the Klan escaped censure by a hair's breadth; the vote itself foretold McAdoo's own defeat in the balloting.

Balloting for President began on June 30. McAdoo and Smith each evolved a strategy to build up his own total slowly. Smith's trick was to plant his extra votes for his opponent, so that McAdoo's strength might later appear to be waning; the Californian countered by holding back his full force, though he had been planning a strong early show. But by no sleight of hand could the convention have been swung around to either contestant. With the party split into two assertive parts, the rule requiring a two-thirds majority for nomination crippled the chances of both candidates by giving a veto each could - and did - use. McAdoo himself wanted to drop the two-thirds rule, but his Protestant supporters preferred to keep their veto over a Catholic candidate, and the South regarded the rule as a protection of its interests. At no point in the balloting did Smith receive more than a single vote from the South and scarcely more than 20 votes from the states west of the Mississippi; he never won more than 368 of the 729 votes needed for nomination, though even this performance was impressive for a Roman Catholic. McAdoo's strength fluctuated more widely, reaching its highest point of 528 on the seventieth ballot. Since both candidates occasionally received purely strategic aid, the nucleus of their support was probably even less. The remainder of the votes were divided among dark horses and favorite sons who had spun high hopes since the Doheny testimony; understandably, they hesitated to withdraw their own candidacies as long as the convention was so clearly divided.

As time passed, the maneuvers of the two factions took on the character of desperation. Daniel C. Roper

Daniel Calhoun Roper (April 1, 1867April 11, 1943) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the 7th United States Secretary of Commerce under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and was the 5th United States Ambassador to Canada from Ma ...

even went to Franklin Roosevelt, reportedly to offer Smith second place on a McAdoo ticket. For their part, the Tammany men tried to prolong the convention until the hotel bills were beyond the means of the outlanders; the Smith backers also attempted to stampede the delegates by packing the galleries with noisy rooters. Senator James Phelan from California, among others, complained of "New York rowdyism." But the rudeness of Tammany, and particularly the booing accord to Bryan when he spoke to the convention, only steeled the resolution of the country delegates. McAdoo and Bryan both tried to reassemble the convention in another city, perhaps Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

or St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

. As a last resort, McAdoo supporters introduced a motion to eliminate one candidate on each ballot until only five remained, but Smith delegates and those supporting favorite sons managed to defeat the McAdoo strategy. Smith countered by suggesting that all delegates be released from their pledges - to which McAdoo agreed on condition that the two-thirds rule be eliminated - although Smith fully expected that loyalty would prevent the disaffection of Indiana and Illinois votes, both controlled by political bosses friendly to him. Indeed, Senator David Walsh from Massachusetts expressed the sentiment that moved Smith backers: "We must continue to do all that we can to nominate Smith. If it should develop that he cannot be nominated, then McAdoo cannot have it either." For his part, McAdoo would angrily quit the convention and leave the country once he lost: but the sixty-first inconclusive round - when the convention set a record for length of balloting - was no time to admit defeat.

It had seemed for a time that the nomination could go to Samuel Ralston, an Indiana senator and popular former governor. Advanced by the indefatigable boss

It had seemed for a time that the nomination could go to Samuel Ralston, an Indiana senator and popular former governor. Advanced by the indefatigable boss Thomas Taggart

Thomas Taggart (November 17, 1856March 6, 1929) was an Irish-American politician who was the political boss of the Democratic Party in Indiana for the first quarter of the twentieth century and remained an influential political figure in loca ...

, Ralston's candidacy might look for some support from Bryan, who had written, "Ralston is the most promising of the compromise candidates." Ralston was also a favorite of the Klan and a second choice of many McAdoo men. In 1922 he had launched an attack on parochial schools that the Klan saw as an endorsement of its own views, and he won several normally Republican counties dominated by the Klan. Commenting on the Klan issue, Ralston said that it would create a bad precedent to denounce any organization by name in the platform. Much of Ralston's support came from the South and West - states like Oklahoma, Missouri, and Nevada, with their strong Klan elements. McAdoo himself, according to Claude Bowers, said: "I like the old Senator, like his simplicity, honesty, record"; and it was reported that he told Smith supporters he would withdraw only in favor of Ralston. As with John W. Davis

John William Davis (April 13, 1873 – March 24, 1955) was an American politician, diplomat and lawyer. He served under President Woodrow Wilson as the Solicitor General of the United States and the United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom ...

, Ralston had few enemies, and his support from men as divergent as Bryan and Taggart cast him as a possible compromise candidate. He passed Davis, the almost consistent third choice of the convention, on the fifty-second ballot; but Taggart then discouraged the boom for the time being because the McAdoo and Smith phalanxes showed no signs of weakening. On July 8, the eighty-seventh ballot showed a total for Ralston of 93 votes, chiefly from Indiana and Missouri; before the day was over, the Ralston total had risen to almost two hundred, a larger tally than Davis had ever received. Most of these votes were drawn from McAdoo, to whom they later returned.

Numerous sources indicate that Taggart was not exaggerating when he later said: "We would have nominated Senator Ralston if he had not withdrawn his name at the last minute. It was a near certainty as anything in politics could be. We had pledges of enough delegates that would shift to Ralston on a certain ballot to have nominated him." Ralston himself had wavered on whether to make the race; despite the doctor's stern recommendation not to run and the illness of his wife and son, the Senator had told Taggart that he would be a candidate, albeit a reluctant one. But the 300-pound Ralston finally telegraphed his refusal to go on with it; sixty-six years old at the time of the convention, he would die the following year.

The nomination, stripped of all honor, finally went to Davis, a compromise candidate who won on the one hundred and third ballot after the withdrawal of Smith and McAdoo. Davis had never been a genuine dark horse candidate; he had almost always been third in the balloting, and by the end of the twenty-ninth round he was the betting favorite of New York gamblers. There had been a Davis movement at the 1920 San Francisco convention of considerable size; however, Charles Hamlin wrote in his diary, Davis "frankly said ... that he was not seeking he nomination

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

and that if nominated he would accept only as a matter of public duty." For Vice-President, the Democrats nominated the able Charles W. Bryan, governor of Nebraska, brother of William Jennings Bryan, and for many years editor of The Commoner. Infamously loquacious, Bryan attacked the gas companies of Nebraska and had attempted controversial projects such as a municipal ice plant for Lincoln. In 1922 he had won the governorship by promising to lower taxes. Bryan received little more than the necessary two-thirds vote, and no attempt was made to make the choice unanimous; boos were sounding through the Garden. The incongruous teaming of the distinguished Wall Street lawyer and the radical from a prairie state provided not a balanced but a polarized ticket, and because the selection of Bryan was reputed to be a sop to the radicals, many delegates unfamiliar with Davis's actual record came to identify the lawyer with a conservatism in excess even of that considerable amount he did indeed represent.

In his acceptance speech Davis made the perfunctory statement that he would enforce the prohibition law, but his conservatism prejudiced him in favor of personal liberty and home rule and he was frequently denounced as a wet. The dry leader Wayne Wheeler complained of Davis's "constant repetition of wet catch phrases like 'personal liberty,' 'illegal search and seizure,' and 'home rule'." After the convention Davis tried to satisfy both factions of his party, but his support came principally from the same city elements that had backed Cox in 1920.

Progressive Party nomination

The movement for a significant new third party had its impetus in 1919 when John A. H. Hopkins, earlier a prominent member of the RooseveltianProgressive Party Progressive Party may refer to:

Active parties

* Progressive Party, Brazil

* Progressive Party (Chile)

* Progressive Party of Working People, Cyprus

* Dominica Progressive Party

* Progressive Party (Iceland)

* Progressive Party (Sardinia), Ita ...

, organized the Committee of 48 as a progressive political action group. The work of political mobilization begun by the committee was taken up in 1922 by a conference of progressives called by the railroad brotherhoods of Chicago, where La Follette established his position as head of the young movement. The majority of participants at a second meeting that December in Cleveland were trade union officials, the delegates including William Green of the United Mine Workers and Sidney Hillman

Sidney Hillman (March 23, 1887 – July 10, 1946) was an American labor leader. He was the head of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America and was a key figure in the founding of the Congress of Industrial Organizations and in marshaling labor' ...

of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America

Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA) was a United States labor union known for its support for "social unionism" and progressive political causes. Led by Sidney Hillman for its first thirty years, it helped found the Congress of Indus ...

. A quarter of the delegates came from the Nonpartisan League

The Nonpartisan League (NPL) was a left-wing political party founded in 1915 in North Dakota by Arthur C. Townley, a former organizer for the Socialist Party of America. On behalf of small farmers and merchants, the Nonpartisan League advocat ...

, the Farmer-Labor Party, and Morris Hillquit's Socialist Party of America, while individual farmers and labor spokesmen comprised the remainder of the progressive conclave. The Forty-Eighters acted as a mediating force between the idealistic Socialists and the pragmatic labor men. Although majority sentiment for an independent party did not crystallize in Cleveland, the dream of a united new liberal party captured the loyalty of many delegates who subsequently turned away from the major parties in 1924.

Out of the Committee of Forty-Eight, some earlier organizations formed by La Follette, and the Chicago conventions grew the Conference for Progressive Political Action. La Follette had told reporters the previous summer that there would be no need for a third ticket unless both parties nominated reactionaries. Then came the Doheny scandals. As it seemed likely at the time that the scandals would eliminate Democratic frontrunner William Gibbs McAdoo

William Gibbs McAdoo Jr.McAdoo is variously differentiated from family members of the same name:

* Dr. William Gibbs McAdoo (1820–1894) – sometimes called "I" or "Senior"

* William Gibbs McAdoo (1863–1941) – sometimes called "II" or "Ju ...

, who was popular among railroad unions and other labor groups, the way was paved for the party which was launched at Cleveland in July 1924. Twelve hundred delegates and nine thousand spectators ratified the nomination of La Follette. The atmosphere was more sober than the one that had prevailed in 1912, where Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

elicited much enthusiasm among the delegations. Farmers themselves were sparsely represented; they were too "broke" to come, according to Senator Lynn Frazier. Only one African-American sat in the audience and only one or two eastern intellectuals. Duly accredited delegates appeared for the Food Reform Society of America, the National Unity Committee, and the Davenport Iowa Ethical Society. Many students attended, one of the largest groups coming from Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

. Jacob Coxey was present as well as John J. Streeter. Radical labor leaders constituted the main body of the congregation. It was the dream of the Progressives that they might replace the Democrats, and thereby bring a clearer ideological alignment to American politics. The best way to do this, according to John Hopkins, would be to prevent either of the major parties from gaining a majority in the Electoral College and thus force the House of Representatives to choose the President.

As the Progressive candidate for president, La Follette became leader of the first formal prominent alliance in American political history between members of organized labor and farm groups, and of these with Socialists and independent radicals. Even the American Federation of Labor, although weakened by a precipitous decline in membership since the First World War, gave La Follette mild backing and so officially supported a presidential candidate for the first time. The Progressive vice-presidential candidate was Senator Burton K. Wheeler

Burton Kendall Wheeler (February 27, 1882January 6, 1975) was an attorney and an American politician of the Democratic Party in Montana, which he represented as a United States senator from 1923 until 1947.

Born in Massachusetts, Wheeler began ...

from Montana, only one of many Democrats who abandoned the chaos of their own party for La Follette's, and found there an idealism and dedication unparalleled within any of the other major political organizations of the 1920s. Wheeler explained his defection in his autobiography: "When the Democratic party goes to Wall Street for a candidate, I must refuse to go with it." The Senator added special strength to the ticket, for he had played a major role in bringing to justice Attorney General Harry Daugherty. Moreover, his selection made it plain that the Progressives would seek votes from both major parties.

Ill with pneumonia and absent from his Senate desk during most of the spring, sixty-eight-year-old La Follette still was a formidable contender. Drawing on a variety of discontents, he could injure the cause of either major party in sections it could ill afford to lose. The long appeal to the farmer in the party platform suggested his major target, but the candidate was addressing every American. In his acceptance speech La Follette urged that military spending be curtailed and soldiers' bonus paid. At the foundation of La Follette's program was an attack on monopolies, which he demanded should be "crushed." His Socialist supporters took this as an attack on the capitalistic system in general; to non-Socialists, including the Senator himself, who believed this encroached on personal liberty, it signified a revival of the policy of trust-busting

Competition law is the field of law that promotes or seeks to maintain market competition by regulating anti-competitive conduct by companies. Competition law is implemented through public and private enforcement. It is also known as antitrust l ...

. The Progressive candidate also called for government ownership of water power and gradual nationalization of the railroads. He also supported the nationalization of cigarette factories and other large industries, strongly supported increased taxation on the wealthy, and supported the right of collective bargaining for factory workers. William Foster, a major figure within the Communist Party