1890s on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 1890s (pronounced "eighteen-nineties") was a

The 1890s (pronounced "eighteen-nineties") was a

*

*

''

Troops Came Just In Time

' April 15, 1892''Wyoming Tails and Trails''

' January 6, 2004 They were also accompanied by surgeon Dr. Charles Penrose, who served as the group's doctor, as well as

Doukhobortsy and Religious Persecution in Russia

, 1900 (Doukhobor Genealogy Website) * 1896â1898: The Philippine Revolution. The

* 1890: A split erupted in

* 1890: A split erupted in

* 1896â1897:

* 1896â1897:

* 1890s:

* 1890s:  * 1893â1894: The

* 1893â1894: The Caroll Gray, "The Herring Powered Biplane Glider 1898"

/ref>

The 1890s (pronounced "eighteen-nineties") was a

The 1890s (pronounced "eighteen-nineties") was a decade

A decade () is a period of ten years. Decades may describe any ten-year period, such as those of a person's life, or refer to specific groupings of calendar years.

Usage

Any period of ten years is a "decade". For example, the statement that "du ...

of the Gregorian calendar

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world. It was introduced in October 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian calendar. The principal change was to space leap years dif ...

that began on January 1, 1890, and ended on December 31, 1899.

In the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, the 1890s were marked by a severe economic depression sparked by the Panic of 1893. This economic crisis would help bring about the end of the so-called "Gilded Age

In United States history, the Gilded Age was an era extending roughly from 1877 to 1900, which was sandwiched between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was a time of rapid economic growth, especially in the Northern and Wes ...

", and coincided with numerous industrial strikes in the industrial workforce. From 1926 the period was sometimes referred to as the "Mauve

Mauve (, ; , ) is a pale purple color named after the mallow flower (French: ''mauve''). The first use of the word ''mauve'' as a color was in 1796â98 according to the ''Oxford English Dictionary'', but its use seems to have been rare befo ...

Decade", because William Henry Perkin

Sir William Henry Perkin (12 March 1838 â 14 July 1907) was a British chemist and entrepreneur best known for his serendipitous discovery of the first commercial synthetic organic dye, mauveine, made from aniline. Though he failed in tryin ...

's aniline dye (discovered in London in 1856) allowed the widespread use of that color in fashion

Fashion is a form of self-expression and autonomy at a particular period and place and in a specific context, of clothing, footwear, lifestyle, accessories, makeup, hairstyle, and body posture. The term implies a look defined by the fashion i ...

in the late 1850s and early 1860s.

In France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

the 1890s formed the core of the so-called '' Belle Ãpoque''.

In the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

the 1890s epitomised the late Victorian period

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardian ...

.

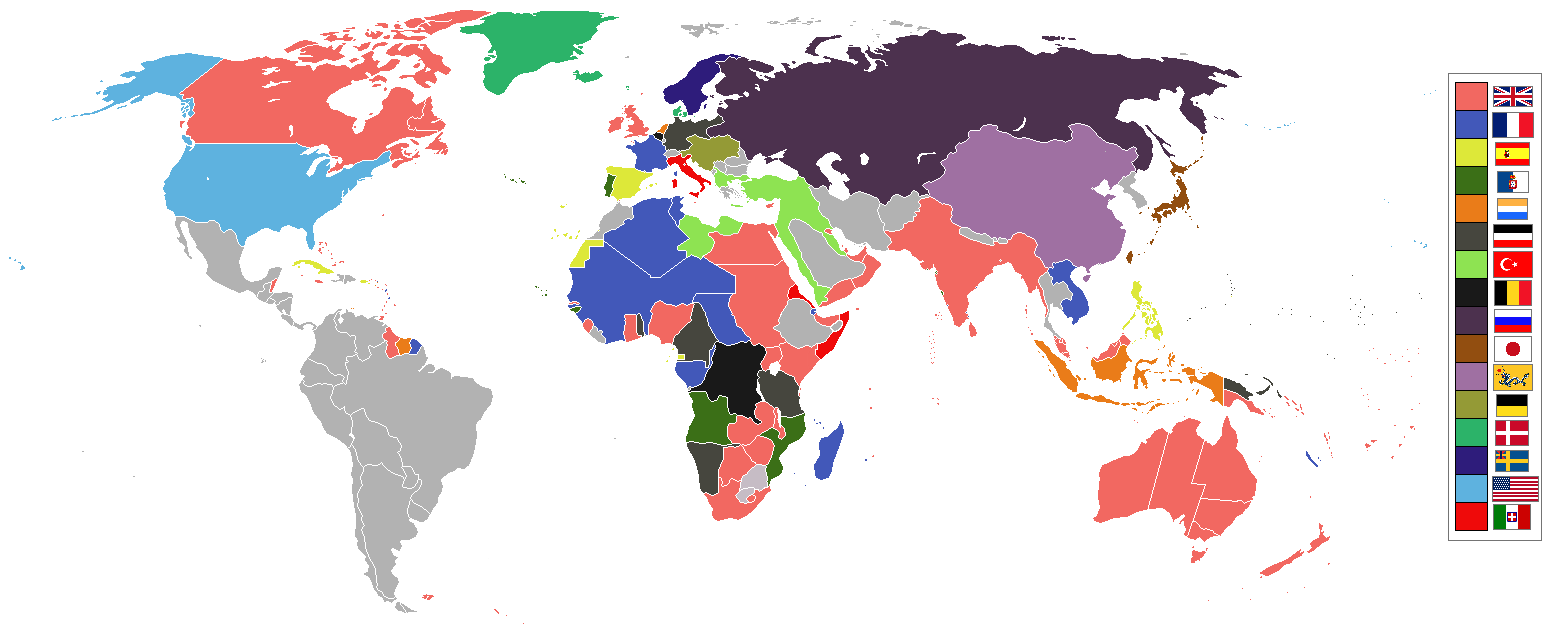

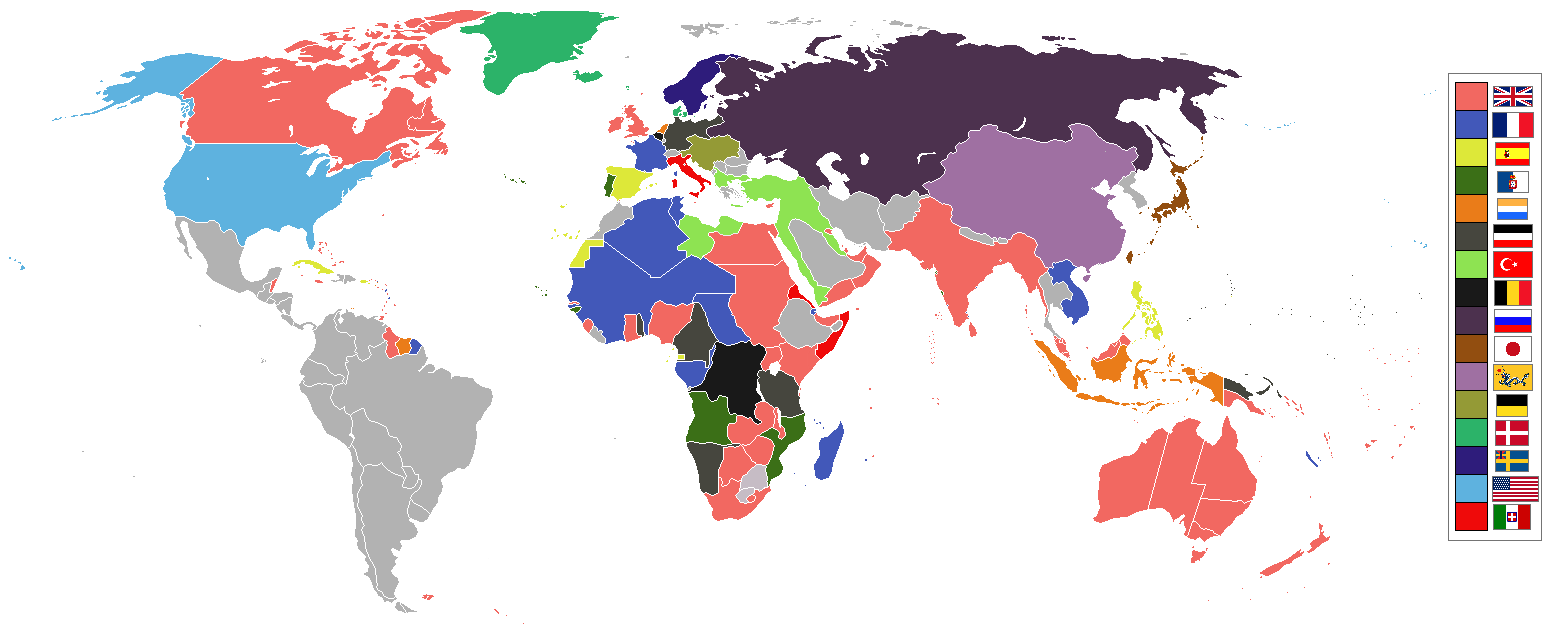

Map

Politics and wars

Wars

*

* First Franco-Dahomean War

The First Franco-Dahomean War was fought in 1890 between France, led by General Alfred-AmÃĐdÃĐe Dodds, and Dahomey under King BÃĐhanzin.

Background

At the close of the 19th century, European powers were busy conquering and colonising much of ...

(1890)

* Second Franco-Dahomean War

The Second Franco-Dahomean War, which raged from 1892 to 1894, was a major conflict between France, led by General Alfred-AmÃĐdÃĐe Dodds, and Dahomey under King BÃĐhanzin. The French emerged triumphant and incorporated Dahomey into their gr ...

(1892â1894)

* First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894 â 17 April 1895) was a conflict between China and Japan primarily over influence in Korea. After more than six months of unbroken successes by Japanese land and naval forces and the loss of the ...

(1894â1895)

* First Italo-Ethiopian War

The First Italo-Ethiopian War, lit. ''Abyssinian War'' was fought between Italy and Ethiopia from 1895 to 1896. It originated from the disputed Treaty of Wuchale, which the Italians claimed turned Ethiopia into an Italian protectorate. Full-sc ...

(1895â1896)

* Greco-Turkish War (1897)

The Greco-Turkish War of 1897 or the Ottoman-Greek War of 1897 ( or ), also called the Thirty Days' War and known in Greece as the Black '97 (, ''Mauro '97'') or the Unfortunate War ( el, ÎÏÏ

ÏÎŪÏ ÏÏÎŧÎĩΞÎŋÏ, Atychis polemos), was a w ...

* SpanishâAmerican War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

(1898)

* PhilippineâAmerican War (1899â1902)

* Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the AngloâBoer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the South ...

(1899â1902)

Wars and Conflicts

* 1890: Wounded Knee Massacre inSouth Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux Native American tribes, who comprise a large porti ...

. On December 29, 1890, 365 troops of the US 7th Cavalry, supported by four Hotchkiss guns, surrounded an encampment of Miniconjou (Lakota

Lakota may refer to:

* Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language, the language of the Lakota peoples

Place names

In the United States:

* Lakota, Iowa

* Lakota, North Dakota, seat of Nelson County

* La ...

) and Hunkpapa Sioux (Lakota) near Wounded Knee Creek

Wounded Knee Creek is a tributary of the White River, approximately 100 miles (160 km) long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed March 30, 2011 in Oglala Lakota County, ...

, South Dakota. The Army had orders to escort the Sioux to the railroad for transport to Omaha, Nebraska

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest cit ...

. One day earlier, the Sioux had been cornered and agreed to turn themselves in at the Pine Ridge Agency in South Dakota. They were the last of the Sioux to do so. In the process of disarming the Sioux, a deaf tribesman named Black Coyote could not hear the order to give up his rifle and was reluctant to do so. A scuffle over Black Coyote's rifle escalated into an all-out battle, with those few Sioux warriors who still had weapons shooting at the 7th Cavalry, and the 7th Cavalry opening fire indiscriminately from all sides, killing men, women, and children, as well as some of their own fellow troopers. The 7th Cavalry quickly suppressed the Sioux fire, and the surviving Sioux fled, but US cavalrymen pursued and killed many who were unarmed. By the time it was over, about 146 men, women, and children of the Lakota Sioux had been killed. Twenty-five troopers also died, some believed to have been the victims of friendly fire

In military terminology, friendly fire or fratricide is an attack by belligerent or neutral forces on friendly troops while attempting to attack enemy/hostile targets. Examples include misidentifying the target as hostile, cross-fire while en ...

as the shooting took place at point-blank range

Point-blank range is any distance over which a certain firearm can hit a target without the need to compensate for bullet drop, and can be adjusted over a wide range of distances by sighting in the firearm. If the bullet leaves the barrel para ...

in chaotic conditions. Around 150 Lakota are believed to have fled the chaos, with an unknown number later dying from hypothermia

Hypothermia is defined as a body core temperature below in humans. Symptoms depend on the temperature. In mild hypothermia, there is shivering and mental confusion. In moderate hypothermia, shivering stops and confusion increases. In severe ...

. The incident is noteworthy as the engagement in military history in which the most Medals of Honor have been awarded in the military history of the United States. This was the last tribe to be invaded which broke the backbone of the American Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, were fought by European governments and colonists in North America, and later by the United States and Canadian governments and American and Canadian settle ...

and the American Frontier.

* 1891: Chilean Civil War fought from January to September. JosÃĐ Manuel Balmaceda

JosÃĐ Manuel Emiliano Balmaceda FernÃĄndez (; July 19, 1840 â September 19, 1891) served as the 10th President of Chile from September 18, 1886, to August 29, 1891. Balmaceda was part of the Castilian-Basque aristocracy in Chile. While he was ...

, President of Chile, and the Chilean Army loyal to him face Jorge Montt's Junta. The latter was formed by an alliance between the National Congress of Chile and the Chilean Navy.

* 1892: The Johnson County War

The Johnson County War, also known as the War on Powder River and the Wyoming Range War, was a range conflict that took place in Johnson County, Wyoming from 1889 to 1893. The conflict began when cattle companies started ruthlessly persecuting ...

in Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to the s ...

. Actually this range war

A range war or range conflict is a type of usually violent conflict, most commonly in the 19th and early 20th centuries in the American West. The subject of these conflicts was control of " open range", or range land freely used for cattle grazing ...

took place in April 1892 in Johnson County, Natrona County and Converse County. The combatants were the Wyoming Stock Growers Association The Wyoming Stock Growers Association (WSGA) is an American cattle organization started in 1872 among Wyoming cattle ranchers to standardize and organize the cattle industry but quickly grew into a political force that has been called "the de facto ...

(the WSGA) and the Northern Wyoming Farmers and Stock Growers' Association (NWFSGA). WSGA was an older organization, comprising some of the state's wealthiest and most popular residents. It held a great deal of political sway in the state and region. A primary function of the WSGA was to organize the cattle industry by scheduling roundups and cattle shipments. The NWFSGAA was a group of smaller Johnson County ranchers led by a local settler named Nate Champion. They had recently formed their organization in order to compete with the WSGA. The WSGA "blacklisted" the NWFSGA and told them to stop all operations, but the NWFSGA refused the powerful WSGA's orders to disband and instead made public their plans to hold their own roundup in the spring of 1892.Burt, Nathaniel 1991 ''Wyoming'' Compass American Guides, Inc p.159 The WSGA, under the direction of Frank Wolcott (WSGA Member and large North Platte rancher), hired a group of skilled gunmen with the intention of eliminating alleged rustlers in Johnson County and break up the NWFSGA.Inventory of the Johnson County War Collection''

Texas A&M University

Texas A&M University (Texas A&M, A&M, or TAMU) is a public, land-grant, research university in College Station, Texas. It was founded in 1876 and became the flagship institution of the Texas A&M University System in 1948. As of late 2021, T ...

â Cushing Memorial Library" Twenty three gunmen from the Paris, Texas

Paris is a city and county seat of Lamar County, Texas, United States. Located in Northeast Texas at the western edge of the Piney Woods, the population of the city was 24,171 in 2020.

History

Present-day Lamar County was part of Red River ...

, region and four cattle detectives from the WSGA were hired, as well as Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the CanadaâUnited States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyomi ...

frontiersman George Dunning who would later turn against the group. A cadre of WSGA and Wyoming dignitaries also joined the expedition, including State Senator Bob Tisdale, state water commissioner W. J. Clarke, as well as W. C. Irvine and Hubert Teshemacher, both instrumental in organizing Wyoming's statehood four years earlier.''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' Troops Came Just In Time

' April 15, 1892''Wyoming Tails and Trails''

' January 6, 2004 They were also accompanied by surgeon Dr. Charles Penrose, who served as the group's doctor, as well as

Asa Mercer

Asa Shinn Mercer (June 6, 1839 â August 10, 1917) was the first president of the Territorial University of Washington and a member of the Washington State Senate.

He is remembered primarily for his role in three milestones of the old America ...

, the editor of the WSGA's newspaper, and a newspaper reporter for the '' Chicago Herald'', Sam T. Clover, whose lurid first-hand accounts later appeared in the eastern newspapers.

* 1893: The Leper War on KauaĘŧi in the island of Kauai. The Provisional Government of Hawaii

The Provisional Government of Hawaii (abbr.: P.G.; Hawaiian: ''Aupuni KÅŦikawÄ o HawaiĘŧi'') was proclaimed after the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 17, 1893, by the 13-member Committee of Safety under the leadership of its ch ...

under Sanford B. Dole

Sanford Ballard Dole (April 23, 1844 â June 9, 1926) was a lawyer and jurist from the Hawaiian Islands. He lived through the periods when Hawaii was a kingdom, protectorate, republic, and territory. A descendant of the American missionary ...

passes a law which would forcibly relocate lepers

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is a long-term infection by the bacteria ''Mycobacterium leprae'' or ''Mycobacterium lepromatosis''. Infection can lead to damage of the nerves, respiratory tract, skin, and eyes. This nerve dama ...

to the Leprosy Colony of Kalawao on the Kalaupapa peninsula

Kalawao County ( haw, Kalana o Kalawao) is a county in the U.S. state of Hawaii. It is the smallest county in the 50 states by land area and the second-smallest county by population, after Loving County, Texas. The county encompasses the Kala ...

. When Kaluaikoolau, a leper, resisted arrest by a deputy sheriff and killed the man, Dole reacted by sending armed militia against the lepers of Kalalau Valley. Kaluaikoolau reportedly foiled or killed some of his pursuers. But the conflict ended with the evacuation of the area in July, 1893. The main source for the event is a 1906 publication by Kahikina Kelekona (John Sheldon), preserving the story as told by Piilani, Kaluaikoolau's widow.

* 1893â1894: Enid-Pond Creek Railroad War in the Oklahoma Territory. Effectively a county seat war

A county seat war is an American phenomenon that occurred mainly in the Old West as it was being settled and county lines determined. Incidents elsewhere, such as in southeastern Ohio and West Virginia, have also been recorded. As new towns s ...

. The Rock Island Railroad Company had invested in the townships of Enid and Pond Creek following an announcement by the United States Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is one of the executive departments of the U.S. federal government headquartered at the Main Interior Building, located at 1849 C Street NW in Washington, D.C. It is responsible for the ma ...

that the two would become county seats. The Department of the Interior decided to create an Enid and Pond Creek at another location, free of company influence. Resulting in two Enids and two Pond Creeks vying for becoming county seats, starting in September, 1893. Rock Island refused to have its trains stop at "Government Enid". They would pass by without taking passengers. Frustrated Enid residents "turned to acts of violence". Some were regularly shooting

Shooting is the act or process of discharging a projectile from a ranged weapon (such as a gun, bow, crossbow, slingshot, or blowpipe). Even the acts of launching flame, artillery, darts, harpoons, grenades, rockets, and guided missiles ...

at the trains. Others were damaging trestles and rail tracks

A railway track (British English and UIC terminology) or railroad track (American English), also known as permanent way or simply track, is the structure on a railway or railroad consisting of the rails, fasteners, railroad ties (sleeper ...

, setting up train accidents. Only government intervention stopped the conflict in September, 1894.

* 1893â1897: War of Canudos

The War of Canudos (, , 1895â1898) was a conflict between the First Brazilian Republic and the residents of Canudos in the northeastern state of Bahia. It was waged in the aftermath of the abolition of slavery in Brazil (1888) and the overt ...

, a conflict between the state of Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

and a group of some 30,000 settlers under AntÃīnio Conselheiro who had founded their own community in the northeastern state of Bahia

Bahia ( , , ; meaning "bay") is one of the 26 states of Brazil, located in the Northeast Region of the country. It is the fourth-largest Brazilian state by population (after SÃĢo Paulo, Minas Gerais, and Rio de Janeiro) and the 5th-largest b ...

, named Canudos. After a number of unsuccessful attempts at military suppression, it came to a brutal end in October 1897, when a large Brazilian army force overran the village and killed most of the inhabitants. The conflict started with Conselheiro and his jagunços (landless peasants) of this "remote and arid" area protesting against the payment of taxes to the distant government of Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after SÃĢo Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a ...

. They founded their own self-sufficient village, soon joined by others in search of a "Promised Land

The Promised Land ( he, ŨŨŨĻŨĨ ŨŨŨŨŨŨŨŠ, translit.: ''ha'aretz hamuvtakhat''; ar, ØĢØąØķ اŲŲ

ŲØđاØŊ, translit.: ''ard al-mi'ad; also known as "The Land of Milk and Honey"'') is the land which, according to the Tanakh (the Hebrew ...

". By 1895, they refused requests by Rodrigues Lima, Governor of Bahia and Jeronimo Thome da Silva, Archbishop of SÃĢo Salvador da Bahia to start obeying the laws of the Brazilian state and the rules of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. In 1896, a military expedition under Lieutenant Manuel da Silva Pires Ferreira was sent to pacify them. It was instead attacked, defeated and forced to retreat. Increasingly stronger military forces were sent against Canudos, only to meet with fierce resistance and suffering heavy casualties. In October 1897, Canudos finally fell to the Brazilian military forces. "Those jagunços who were not killed in combat were taken prisoner and summarily executed (by beheading) by the army".

* 1894: The Donghak Peasant Revolution

The Donghak Peasant Revolution (), also known as the Donghak Peasant Movement (), Donghak Rebellion, Peasant Revolt of 1894, Gabo Peasant Revolution, and a variety of other names, was an armed rebellion in Korea led by peasants and followers o ...

in Joseon Korea. The uprising started in Gobu during February 1894, with the peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasant ...

class protesting against the political corruption of local government officials. The revolution was named after Donghak

Donghak (formerly spelled Tonghak; ) was an academic movement in Korean Neo-Confucianism founded in 1860 by Choe Je-u. The Donghak movement arose as a reaction to seohak (), and called for a return to the "Way of Heaven". While Donghak origin ...

, a Korean religion stressing "the equality

Equality may refer to:

Society

* Political equality, in which all members of a society are of equal standing

** Consociationalism, in which an ethnically, religiously, or linguistically divided state functions by cooperation of each group's elit ...

of all human beings". The forces of Emperor Gojong

Gojong (; 8 September 1852 â 21 January 1919) was the monarch of Korea from 1864 to 1907. He reigned as the last King of Joseon from 1864 to 1897, and as the first Emperor of Korea from 1897 until his forced abdication in 1907. He is known ...

failed in their attempt to suppress the revolt, with initial skirmishes giving way to major conflicts. The Korean government requested assistance from the Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitu ...

. Japanese troops, armed with " rifles and artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

", managed to suppress the revolution. With Korea being a tributary state

A tributary state is a term for a pre-modern state in a particular type of subordinate relationship to a more powerful state which involved the sending of a regular token of submission, or tribute, to the superior power (the suzerain). This to ...

to Qing Dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-spea ...

China, the Japanese military presence was seen as a provocation. The resulting conflict over dominance of Korea would become the First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894 â 17 April 1895) was a conflict between China and Japan primarily over influence in Korea. After more than six months of unbroken successes by Japanese land and naval forces and the loss of the ...

. In part, the government of Emperor Meiji was acting to prevent expansion by the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

or any other great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power in ...

towards Korea. Viewing such an expansion as a direct threat to Japanese national security.

* 1895: The Doukhobor

The Doukhobours or Dukhobors (russian: ÐīŅŅ

ÐūÐąÐūŅŅ / ÐīŅŅ

ÐūÐąÐūŅŅŅ, dukhobory / dukhobortsy; ) are a Spiritual Christian ethnoreligious group of Russian origin. They are one of many non-Orthodox ethno-confessional faiths in Russia a ...

s, a pacifist Christian sect of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, attempt to resist a number of laws and regulations forced on them by the Russian government. They are mostly active in the South Caucasus

The South Caucasus, also known as Transcaucasia or the Transcaucasus, is a geographical region on the border of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, straddling the southern Caucasus Mountains. The South Caucasus roughly corresponds to modern Arme ...

, where universal military conscription was introduced in 1887 and was still controversial. They also refuse to swear an oath of allegiance to Nicholas II, the new Russian Emperor. Under further instructions from their exiled leader Peter Vasilevich Verigin

Peter Vasilevich Verigin (russian: ÐŅŅŅ ÐаŅÐļÐŧŅÐĩÐēÐļŅ ÐÐĩŅÐļÐģÐļÐ―) often known as Peter "the Lordly" Verigin ( - October 29, 1924) was a Russian philosopher, activist, and leader of the Community Doukhobors in Canada.

Biography

I ...

, as a sign of absolute pacifism, the Doukhobors of the three Governorates of Transcaucasia made the decision to destroy their weapon

A weapon, arm or armament is any implement or device that can be used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime, law enforcement, ...

s. As the Doukhobors assembled to burn them on the night of June 28/29 (July 10/11, Gregorian calendar

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world. It was introduced in October 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian calendar. The principal change was to space leap years dif ...

) 1895, with the singing of psalms and spiritual songs, arrests and beatings by government Cossacks followed. Soon, Cossacks were billeted in many of the Large Party Doukhobors' villages, and over 4,000 of their original residents were dispersed through villages in other parts of Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. Many of those died of starvation and exposure.John AshworthDoukhobortsy and Religious Persecution in Russia

, 1900 (Doukhobor Genealogy Website) * 1896â1898: The Philippine Revolution. The

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, RepÚblica de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, part of the Spanish East Indies

The Spanish East Indies ( es , Indias orientales espaÃąolas ; fil, Silangang Indiyas ng Espanya) were the overseas territories of the Spanish Empire in Asia and Oceania from 1565 to 1898, governed for the Spanish Crown from Mexico City and Madri ...

, attempt to secede from the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio espaÃąol), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, MonarquÃa HispÃĄnica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, MonarquÃa CatÃģlica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

. The Philippine Revolution began in August 1896, upon the discovery of the anti-colonial

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on independence ...

secret organization

A secret society is a club or an organization whose activities, events, inner functioning, or membership are concealed. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence a ...

''Katipunan

The Katipunan, officially known as the Kataastaasan, Kagalanggalangang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan or Kataastaasan Kagalang-galang na Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan (KKK; en, Supreme and Honorable Association of the Children of the Nation ...

'' by the Spanish authorities. The ''Katipunan'', led by AndrÃĐs Bonifacio, was a secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

ist movement and shadow government spread throughout much of the islands whose goal was independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

from Spain through armed revolt. In a mass gathering in Caloocan

Caloocan, officially the City of Caloocan ( fil, Lungsod ng Caloocan; ), is a 1st class highly urbanized city in Metropolitan Manila, Philippines. According to the 2020 census, it has a population of 1,661,584 people making it the fourth-most ...

, the ''Katipunan'' leaders organized themselves into a revolutionary government and openly declared a nationwide armed revolution. Bonifacio called for a simultaneous coordinated attack on the capital Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populate ...

. This attack failed, but the surrounding provinces also rose up in revolt. In particular, rebels in Cavite

Cavite, officially the Province of Cavite ( tl, Lalawigan ng Kabite; Chavacano: ''Provincia de Cavite''), is a province in the Philippines located in the Calabarzon region in Luzon. Located on the southern shores of Manila Bay and southwest ...

led by Emilio Aguinaldo won early victories. A power struggle among the revolutionaries led to Bonifacio's execution in 1897, with command shifting to Aguinaldo who led his own revolutionary government. That year, a truce was officially reached with the Pact of Biak-na-Bato

The Pact of Biak-na-Bato, signed on December 15, 1897, created a truce between Spanish colonial Governor-General Fernando Primo de Rivera and the revolutionary leader Emilio Aguinaldo to end the Philippine Revolution. Aguinaldo and his fellow rev ...

and Aguinaldo was exiled to Hong Kong, though hostilities between rebels and the Spanish government never actually ceased.* In 1898, with the outbreak of the SpanishâAmerican War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

, Aguinaldo unofficially allied with the United States, returned to the Philippines and resumed hostilities against the Spaniards. By June, the rebels had conquered nearly all Spanish-held ground within the Philippines with the exception of Manila. Aguinaldo thus declared independence from Spain and the First Philippine Republic

The Philippine Republic ( es, RepÚblica Filipina), now officially known as the First Philippine Republic, also referred to by historians as the Malolos Republic, was established in Malolos, Bulacan during the Philippine Revolution against ...

was established. However, neither Spain nor the United States recognized Philippine independence. Spanish rule in the islands only officially ended with the 1898 Treaty of Paris, wherein Spain ceded the Philippines and other territories to the United States. The PhilippineâAmerican War broke out shortly afterward.

* 1897: The Lattimer massacre

The Lattimer massacre was the violent deaths of at least 19 unarmed striking immigrant anthracite miners at the Lattimer mine near Hazleton, Pennsylvania, United States, on September 10, 1897.Anderson, John W. ''Transitions: From Eastern Europ ...

. The violent deaths of 19 unarmed striking immigrant anthracite coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when ...

miners at the Lattimer mine near Hazleton, Pennsylvania

Hazleton is a city in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 29,963 at the 2020 census. Hazleton is the second largest city in Luzerne County. It was incorporated as a borough on January 5, 1857, and as a city on Decembe ...

, on September 10, 1897.Anderson, John W. ''Transitions: From Eastern Europe to Anthracite Community to College Classroom.'' Bloomington, Ind.: iUniverse, 2005. Miller, Randall M. and Pencak, William. ''Pennsylvania: A History of the Commonwealth.'' State College, Penn.: Penn State Press, 2003. The miners, mostly of Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

, Slovak, and Lithuanian ethnicity, were shot and killed by a Luzerne County

Luzerne County is a county in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of , of which is land and is water. It is Northeastern Pennsylvania's second-largest county by total area. As of ...

sheriff's posse

Posse is a shortened form of posse comitatus, a group of people summoned to assist law enforcement. The term is also used colloquially to mean a group of friends or associates.

Posse may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Posse'' (1975 ...

. Scores more workers were wounded.Estimates of the number of wounded are inexact. They range from a low of 17 wounded (Duwe, Grant. ''Mass Murder in the United States: A History.'' Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2007. ) to a high of 49 (DeLeon, Clark. ''Pennsylvania Curiosities: Quirky Characters, Roadside Oddities & Other Offbeat Stuff.'' 3rd rev. ed. Guilford, Conn.: Globe Pequot, 2008. ). Other estimates include 30 wounded (Lewis, Ronald L. ''Welsh Americans: A History of Assimilation in the Coalfields.'' Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 2008. ), 32 wounded (Anderson, ''Transitions: From Eastern Europe to Anthracite Community to College Classroom,'' 2005; Berger, Stefan; Croll, Andy; and Laporte, Norman. ''Towards A Comparative History of Coalfield Societies.'' Aldershot, Hampshire, UK: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2005. ; Campion, Joan. ''Smokestacks and Black Diamonds: A History of Carbon County, Pennsylvania.'' Easton, Penn.: Canal History and Technology Press, 1997. ), 35 wounded (Foner, Philip S. ''First Facts of American Labor: A Comprehensive Collection of Labor Firsts in the United States.'' New York: Holmes & Meier, 1984. ; Miller and Pencak, ''Pennsylvania: A History of the Commonwealth,'' 2003; Derks, Scott. ''Working Americans, 1880â2006: Volume VII: Social Movements.'' Amenia, N.Y.: Grey House Publishing, 2006. ), 38 wounded (Weir, Robert E. and Hanlan, James P. ''Historical Encyclopedia of American Labor, Vol. 1.'' Santa Barbara, Calif.: Greenwood Press, 2004. ), 39 wounded ( Long, Priscilla. '' Where the Sun Never Shines: A History of America's Bloody Coal Industry.'' Minneapolis: Paragon House, 1989. ; Novak, Michael. ''The Guns of Lattimer.'' Reprint ed. New York: Transaction Publishers, 1996. ), and 40 wounded (Beers, Paul B. ''The Pennsylvania Sampler: A Biography of the Keystone State and Its People.'' Mechanicsburg, Penn.: Stackpole Books, 1970). The Lattimer massacre was a turning point in the history of the United Mine Workers (UMW).

* 1898: The Bava Beccaris massacre in Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

, Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to an institutional referendum to abandon the monarchy and f ...

. On May 5, 1898, workers organized a strike

Strike may refer to:

People

* Strike (surname)

Physical confrontation or removal

*Strike (attack), attack with an inanimate object or a part of the human body intended to cause harm

*Airstrike, military strike by air forces on either a suspected ...

to demonstrate against the government of Antonio Starabba, Marchese di RudinÃŽ, Prime Minister of Italy, holding it responsible for the general increase of prices and for the famine that was affecting the country. The first blood was shed that day at Pavia

Pavia (, , , ; la, Ticinum; Medieval Latin: ) is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy in northern Italy, south of Milan on the lower Ticino river near its confluence with the Po. It has a population of c. 73,086. The city was the cap ...

, when the son of the mayor of Milan was killed while attempting to halt the troops marching against the crowd. After a protest in Milan the following day, the government declared a state of siege

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

in the city. Infantry, cavalry and artillery were brought into the city and General Fiorenzo Bava Beccaris ordered his troops to fire on demonstrators. According to the government, there were 118 dead and 450 wounded. The opposition claimed 400 dead and more than 2,000 injured people. Filippo Turati

Filippo Turati (; 26 November 1857 â 29 March 1932) was an Italian sociologist, criminologist, poet and socialist politician.

Early life

Born in Canzo, province of Como, he graduated in law at the University of Bologna in 1877, and participa ...

, one of the founder of the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Socialism, socialist and later Social democracy, social-democratic List of political parties in Italy, political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the l ...

, was arrested and accused of inspiring the riots.

* 1898: The VouletâChanoine Mission a disastrous French military expedition sent out from Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: ðĪ

ðĪŦðĪēðĪŦðĪšðĪĒðĨðĪĪðĪ (Senegaali); Arabic: اŲØģŲؚاŲ ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''RÃĐewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : ðĪðĪŦðĪēðĪĢðĪĒðĨðĪēðĪĢðĪ ...

to conquer the Chad Basin and unify all French territories in West Africa. The expedition descended into wanton violence against the local population and ended in sedition on the part of the commanders.

* 1898: The Battle of Sugar Point

The Battle of Sugar Point, or the Battle of Leech Lake, was fought on October 5, 1898 between the 3rd U.S. Infantry and members of the Pillager Band of Chippewa Indians in a failed attempt to apprehend Pillager Ojibwe Bugonaygeshig ("Old Bug" or ...

takes place in the northeast shore of Leech Lake

Leech Lake is a lake located in north central Minnesota, United States. It is southeast of Bemidji, located mainly within the Leech Lake Indian Reservation, and completely within the Chippewa National Forest. It is used as a reservoir. The lake ...

, Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over to ...

. "Old Bug" ( Bugonaygeshig), a leading member of the Pillager Band of Chippewa Indians Pillager Band of Chippewa Indians (or simply the Pillagers; in the Ojibwe language) are a historical band of Chippewa (Ojibwe) who settled at the headwaters of the Mississippi River in present-day Minnesota. Their name "Pillagers" is a translatio ...

in Bear Island had been arrested in September, 1898. A reported number of 22 Pillagers helped him escape. Arrest warrants were issued for all Pillagers involved in the incident. On October 5, 1898, about 80 men serving or attached to the 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment arrived on Bear Island to perform the arrests. Finding it abandoned, they proceeded to Sugar Point. There, a force of 19 Pillagers armed with Winchester rifle

Winchester rifle is a comprehensive term describing a series of lever action repeating rifles manufactured by the Winchester Repeating Arms Company. Developed from the 1860 Henry rifle, Winchester rifles were among the earliest repeaters. The Mo ...

was observing the soldiers from a forested area. When a soldier fired his weapon, allegedly a new recruit who had done so accidentally, the Pillagers returned fire. Major Melville Wilkinson, the commanding officer, was shot three times and killed. By the end of the conflict, seven soldiers had been killed (including Wilkinson), another 16 wounded. There were no casualties among the 19 Natives. Peaceful relations were soon re-established but this uprising was among the last Native American victories in the American Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, were fought by European governments and colonists in North America, and later by the United States and Canadian governments and American and Canadian settle ...

. It is known as "the last Indian Uprising in the United States".

Prominent political events

* 1890: A split erupted in

* 1890: A split erupted in Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of c ...

over a scandal involving the Irish leader Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell (27 June 1846 â 6 October 1891) was an Irish nationalist politician who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1875 to 1891, also acting as Leader of the Home Rule League from 1880 to 1882 and then Leader of the ...

's affair with a fellow MP's wife, Kitty O'Shea.

*1893: New Zealand becomes the first country to grant women the vote.

* 1894: The Greenwich Observatory

The Royal Observatory, Greenwich (ROG; known as the Old Royal Observatory from 1957 to 1998, when the working Royal Greenwich Observatory, RGO, temporarily moved south from Greenwich to Herstmonceux) is an observatory situated on a hill in G ...

bomb attack. This was possibly the first widely publicised terrorist incident in Britain.

* The Dreyfus affair

The Dreyfus affair (french: affaire Dreyfus, ) was a political scandal that divided the French Third Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolise modern injustice in the Francop ...

â a political scandal that divided France in the 1890s and the early 20th century. It involved the conviction for treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

in November 1894 of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a young French artillery officer of Alsatian Jewish descent.

* 1895: The Gongche Shangshu movement. In April, Over 1300 JĮrÃĐn, present in Beijing to participate in the imperial examination, sign a petition requesting reforms by the Guangxu Emperor

The Guangxu Emperor (14 August 1871 â 14 November 1908), personal name Zaitian, was the tenth Emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the ninth Qing emperor to rule over China proper. His reign lasted from 1875 to 1908, but in practice he ruled, w ...

. Kang Youwei

Kang Youwei (; Cantonese: ''HÅng YÃĄuh-wà ih''; 19March 185831March 1927) was a prominent political thinker and reformer in China of the late Qing dynasty. His increasing closeness to and influence over the young Guangxu Emperor spar ...

is the main organizer of the movement. In May, thousands of Beijing scholars and citizens protested against the Treaty of Shimonoseki

The , also known as the Treaty of Maguan () in China and in the period before and during World War II in Japan, was a treaty signed at the , Shimonoseki, Japan on April 17, 1895, between the Empire of Japan and Qing China, ending the Firs ...

. The Emperor would respond with the Hundred Days' Reform

The Hundred Days' Reform or Wuxu Reform () was a failed 103-day national, cultural, political, and educational reform movement that occurred from 11 June to 22 September 1898 during the late Qing dynasty. It was undertaken by the young Guangxu E ...

of 1898.

* 1896 Republican Realignment

* The 1896 Cross of Gold speech

The Cross of Gold speech was delivered by William Jennings Bryan, a former United States Representative from Nebraska, at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago on July 9, 1896. In his address, Bryan supported " free silver" (i.e. bim ...

by William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 â July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the Democratic Party, running three times as the party's nominee for President ...

* The New Imperialism

In historical contexts, New Imperialism characterizes a period of colonial expansion by European powers, the United States, and Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Com

The period featured an unprecedented pursuit of ove ...

* The Populist Party reaches its high point in American history.

Economics in the United States

* 1892: TheHomestead Strike

The Homestead strike, also known as the Homestead steel strike, Homestead massacre, or Battle of Homestead, was an industrial lockout and strike that began on July 1, 1892, culminating in a battle in which strikers defeated private security age ...

in Homestead, Pennsylvania

Homestead is a borough in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, USA, in the Monongahela River valley southeast of downtown Pittsburgh and directly across the river from the city limit line. The borough is known for the ...

. Labor dispute between the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers

Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers (AA) was an American labor union formed in 1876 to represent iron and steel workers. It partnered with the Steel Workers Organizing Committee of the CIO, in November 1935. Both organizations di ...

(the AA) and the Carnegie Steel Company

Carnegie Steel Company was a steel-producing company primarily created by Andrew Carnegie and several close associates to manage businesses at steel mills in the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania area in the late 19th century. The company was form ...

starting in June, 1892. The union negotiated national uniform wage scales on an annual basis; helped regularize working hours, workload levels and work speeds; and helped improve working conditions. It also acted as a hiring hall

In organized labor, a hiring hall is an organization, usually under the auspices of a labor union, which has the responsibility of furnishing new recruits for employers who have a collective bargaining agreement with the union. It may also refer t ...

, helping employers find scarce puddlers and rollers. With the collective bargaining agreement due to expire on June 30, 1892, Henry Clay Frick

Henry Clay Frick (December 19, 1849 â December 2, 1919) was an American industrialist, financier, and art patron. He founded the H. C. Frick & Company coke manufacturing company, was chairman of the Carnegie Steel Company, and played a maj ...

(chairman of the company) and the leaders of the local AA union entered into negotiations in February. With the steel industry doing well and prices higher, the AA asked for a wage increase. Frick immediately countered with a 22% wage decrease that would affect nearly half the union's membership and remove a number of positions from the bargaining unit. Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (, ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans i ...

encouraged Frick to use the negotiations to break the union: "...the Firm has decided that the minority must give way to the majority. These works, therefore, will be necessarily non-union after the expiration of the present agreement." Frick locked workers out of the plate mill and one of the open hearth furnace

An open-hearth furnace or open hearth furnace is any of several kinds of industrial Industrial furnace, furnace in which excess carbon and other impurities are burnt out of pig iron to Steelmaking, produce steel. Because steel is difficult to ma ...

s on the evening of June 28. When no collective bargaining agreement was reached on June 29, Frick locked the union out of the rest of the plant. A high fence topped with barbed wire, begun in January, was completed and the plant sealed to the workers. Sniper towers with searchlights were constructed near each mill building, and high-pressure water cannon

A water cannon is a device that shoots a high-velocity stream of water. Typically, a water cannon can deliver a large volume of water, often over dozens of meters. They are used in firefighting, large vehicle washing, riot control, and mining ...

s (some capable of spraying boiling-hot liquid) were placed at each entrance. Various aspects of the plant were protected, reinforced or shielded.

* 1892: Buffalo switchmen's strike in Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from Sou ...

, during August, 1892. In early 1892, the New York State Legislature

The New York State Legislature consists of the two houses that act as the state legislature of the U.S. state of New York: The New York State Senate and the New York State Assembly. The Constitution of New York does not designate an officia ...

passed a law mandating a 10-hour work-day and increases in the day- and night-time minimum wage. On August 12, switchmen in the Buffalo railyards struck the Lehigh Valley Railroad

The Lehigh Valley Railroad was a railroad built in the Northeastern United States to haul anthracite coal from the Coal Region in Pennsylvania. The railroad was authorized on April 21, 1846 for freight and transportation of passengers, goods, ...

, the Erie Railroad

The Erie Railroad was a railroad that operated in the northeastern United States, originally connecting New York City â more specifically Jersey City, New Jersey, where Erie's Pavonia Terminal, long demolished, used to stand â with Lake Er ...

and the Buffalo Creek Railroad after the companies refused to obey the new law.Foner, Philip S. History of the Labor Movement in the United States: From the Founding of the A.F. of L. to the Emergence of American Imperialism, p. 253. 2nd ed. New York: International Publishers, Co., 1975. On August 15, Democratic Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Roswell P. Flower called out the New York State Guard

The New York Guard (NYG) is the state defense force of New York State, also called The New York State Military Reserve. Originally called the New York State Militia it can trace its lineage back to the American Revolution and the War of 1812.

T ...

to restore order and protect the railroads' property. However, State Guard Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Peter C. Doyle, commanding the Fourth Brigade, held a full-time position as an agent of the Lehigh Valley Railroad and was determined to crush the strike.

* 1892: New Orleans general strike taking place in , during November, 1892. 49 labor unions affiliated through the American Federation of Labor (AFL) had established a central labor council known as the Workingmen's Amalgamated Council that represented more than 20,000 workers. Three racially integrated unionsâthe Teamsters

The International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT), also known as the Teamsters Union, is a labor union in the United States and Canada. Formed in 1903 by the merger of The Team Drivers International Union and The Teamsters National Union, the ...

, the Scalesmen, and the Packersâmade up what came to be called the "Triple Alliance." Many of the workers belonging to the unions of the Triple Alliance were African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

.Rosenberg, ''New Orleans Dockworkers: Race, Labor, and Unionism, 1892â1923,'' 1988. The Triple Alliance started negotiations with the New Orleans Board of Trade in October. Employers utilized race-based appeals to try to divide the workers and turn the public against the strikers. The board of trade announced it would sign contracts agreeing to the termsâbut only with the white-dominated Scalesmen and Packers unions. The Board of Trade refused to sign any contract with the black-dominated Teamsters. The Board of Trade and the city's newspapers also began a campaign designed to create public hysteria. The newspapers ran lurid accounts of "mobs of brutal Negro strikers" rampaging through the streets, of African American unionists "beating up all who attempted to interfere with them," and repeated accounts of crowds of blacks assaulting lone white men and women. The striking workers refused to break ranks along racial lines. Large majorities of the Scalesmen and Packers unions passed resolutions affirming their commitment to stay out until the employers had signed a contract with the Teamsters on the same terms offered to other unions. The Board of Trade's tactics essentially backfired when the Workingmen's Amalgamated Council called for a general strike, involving all of its unions. The city's supply of natural gas failed on November 8, as did the electrical grid, and the city was plunged into darkness. The delivery of food and beverages immediately ceased, generating alarm among city residents. Construction, printing, street cleaning, manufacturing and even fire-fighting services ground to a halt.Foner, ''History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol. 2: From the Founding of the American Federation of Labor to the Emergence of American Imperialism,'' 1955.

* 1893: The Panic of 1893 set off a widespread economic depression in the United States of America that lasts until 1896. One of the first signs of trouble was the bankruptcy of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad

The Reading Company ( ) was a Philadelphia-headquartered railroad that provided passenger and commercial rail transport in eastern Pennsylvania and neighboring states that operated from 1924 until its 1976 acquisition by Conrail.

Commonly called ...

, which had greatly over-extended itself, on February 23, 1893, ten days before Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

's second inauguration. Some historians consider this bankruptcy to be the beginning of the Panic. As concern of the state of the economy worsened, people rushed to withdraw their money from banks and caused bank runs. The credit crunch

A credit crunch (also known as a credit squeeze, credit tightening or credit crisis) is a sudden reduction in the general availability of loans (or credit) or a sudden tightening of the conditions required to obtain a loan from banks. A credit cr ...

rippled through the economy. A financial panic in the United Kingdom and a drop in trade in Europe caused foreign investors to sell American stocks to obtain American funds backed by gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile me ...

.

People attempted to redeem silver notes for gold; ultimately the statutory limit for the minimum amount of gold in federal reserves was reached and US notes could no longer be successfully redeemed for gold. Investments during the time of the Panic were heavily financed through bond issues with high interest payments. The National Cordage Company (the most actively traded stock at the time) went into receivership

In law, receivership is a situation in which an institution or enterprise is held by a receiverâa person "placed in the custodial responsibility for the property of others, including tangible and intangible assets and rights"âespecially in c ...

as a result of its bankers calling their loans in response to rumors regarding the NCC's financial distress. As the demand for silver and silver notes fell, the price and value of silver

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European ''hâerĮĩ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical ...

dropped. Holders worried about a loss of face value of bonds, and many became worthless. A series of bank failures followed, and the Northern Pacific Railway, the Union Pacific Railroad

The Union Pacific Railroad , legally Union Pacific Railroad Company and often called simply Union Pacific, is a freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Paci ...

and the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad

The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway , often referred to as the Santa Fe or AT&SF, was one of the larger railroads in the United States. The railroad was chartered in February 1859 to serve the cities of Atchison and Topeka, Kansas, and ...

failed. This was followed by the bankruptcy of many other companies; in total over 15,000 companies and 500 banks failed (many in the west). According to high estimates, about 17%â19% of the workforce was unemployed

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work during the refere ...

at the Panic's peak. The huge spike in unemployment, combined with the loss of life savings by failed banks, meant that a once-secure middle-class could not meet their mortgage

A mortgage loan or simply mortgage (), in civil law jurisdicions known also as a hypothec loan, is a loan used either by purchasers of real property to raise funds to buy real estate, or by existing property owners to raise funds for any ...

obligations. As a result, many walked away from recently built homes. From this, the sight of the vacant Victorian (haunted

Haunted or The Haunted may refer to:

Books

* ''Haunted'' (Armstrong novel), by Kelley Armstrong, 2005

* ''Haunted'' (Cabot novel), by Meg Cabot, 2004

* ''Haunted'' (Palahniuk novel), by Chuck Palahniuk, 2005

* ''Haunted'' (Angel novel), a 200 ...

) house entered the American mindset.

* 1894: Cripple Creek miners' strike, a five-month strike by the Western Federation of Miners

The Western Federation of Miners (WFM) was a trade union, labor union that gained a reputation for militancy in the mining#Human Rights, mines of the western United States and British Columbia. Its efforts to organize both hard rock miners and ...

(WFM) in Cripple Creek, Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the wes ...

, United States. In January 1894, Cripple Creek mine owners J. J. Hagerman, David Moffat and Eben Smith

Eben Smith (December 17, 1832 â November 5, 1906) was a successful mine owner, smelting company executive, railroad executive and bank owner in Colorado in the late 19th century and early 20th century.

Early life

Eben Smith was born in Erie, Pen ...

, who together employed one-third of the area's miners, announced a lengthening of the work-day to ten hours (from eight), with no change to the daily wage of $3.00 per day. When workers protested, the owners agreed to employ the miners for eight hours a day â but at a wage of only $2.50.Holbrook, Stewart. The Rocky Mountain Revolution. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1956. p.73â74 Not long before this dispute, miners at Cripple Creek had formed the Free Coinage Union. Once the new changes went into effect, they affiliated with the Western Federation of Miners

The Western Federation of Miners (WFM) was a trade union, labor union that gained a reputation for militancy in the mining#Human Rights, mines of the western United States and British Columbia. Its efforts to organize both hard rock miners and ...

, and became Local 19. The union was based in Altman, and had chapters in Anaconda

Anacondas or water boas are a group of large snakes of the genus '' Eunectes''. They are found in tropical South America. Four species are currently recognized.

Description

Although the name applies to a group of snakes, it is often used ...

, Cripple Creek and Victor. On February 1, 1894, the mine owners began implementing the 10-hour day. Union president John Calderwood issued a notice a week later demanding that the mine owners reinstate the eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the ...

at the $3.00 wage. When the owners did not respond, the nascent union struck on February 7. Portland, Pikes Peak, Gold Dollar and a few smaller mines immediately agreed to the eight-hour day and remained open, but larger mines held out.

* 1894: Coxey's Army

Coxey's Army was a protest march by unemployed workers from the United States, led by Ohio businessman Jacob Coxey. They marched on Washington, D.C. in 1894, the second year of a four-year economic depression that was the worst in United Sta ...

a protest march by unemployed workers from the United States, led by the populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term develop ...

Jacob Coxey

Jacob Sechler Coxey Sr. (April 16, 1854 â May 18, 1951), sometimes known as General Coxey, of Massillon, Ohio, was an American politician who ran for elective office several times in Ohio. Twice, in 1894 and 1914, he led "Coxey's Army", a grou ...

. The purpose of the march was to protest the unemployment caused by the Panic of 1893 and to lobby for the government to create jobs which would involve building road

A road is a linear way for the conveyance of traffic that mostly has an improved surface for use by vehicles (motorized and non-motorized) and pedestrians. Unlike streets, the main function of roads is transportation.

There are many types of ...

s and other public works

Public works are a broad category of infrastructure projects, financed and constructed by the government, for recreational, employment, and health and safety uses in the greater community. They include public buildings ( municipal buildings, sc ...

improvements. The march originated with 100 men in Massillon, Ohio, on March 25, 1894, passing through Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Western Pennsylvania, the second-most populous city in Pennsylva ...

, Becks Run and Homestead, Pennsylvania

Homestead is a borough in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, USA, in the Monongahela River valley southeast of downtown Pittsburgh and directly across the river from the city limit line. The borough is known for the ...

, in April.

* 1894: The Bituminous Coal Miners' Strike, an unsuccessful national eight-week strike by miners of hard coal in the United States, which began on April 21, 1894. Initially, the strike was a major success. More than 180,000 miners in Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the wes ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

, Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, and West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the B ...

struck. In Illinois, 25,207 miners went on strike, while only 610 continued to work through the strike, with the average Illinois miner out of work for 72 days because of the strike. In some areas of the country, violence erupted between strikers and mine operators or between striking and non-striking miners. On May 23 near Uniontown, Pennsylvania

Uniontown is a city in Fayette County, Pennsylvania, United States, southeast of Pittsburgh and part of the Greater Pittsburgh Region. The population was 10,372 at the 2010 census, down from 12,422 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat and ...

, 15 guards armed with carbine

A carbine ( or ) is a long gun that has a barrel shortened from its original length. Most modern carbines are rifles that are compact versions of a longer rifle or are rifles chambered for less powerful cartridges.

The smaller size and lighte ...

s and machine gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic, rifled autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as automatic shotguns and automatic rifles (including assault rifles and battle rifles) ar ...

s held off an attack by 1500 strikers, killing 5 and wounding 8.

* 1894: May Day Riots, a series of violent demonstrations that occurred throughout Cleveland, Ohio, on May 1, 1894 (May Day

May Day is a European festival of ancient origins marking the beginning of summer, usually celebrated on 1 May, around halfway between the spring equinox and summer solstice. Festivities may also be held the night before, known as May Eve. Tr ...

). Cleveland's unemployment rate increased dramatically during the Panic of 1893. Finally, riots broke out among the unemployed who condemned city leaders for their ineffective relief measures.

* 1894: The workers of the Pullman Company went on strike in Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

. During the economic panic of 1893, the Pullman Palace Car Company

The Pullman Company, founded by George Pullman, was a manufacturer of railroad cars in the mid-to-late 19th century through the first half of the 20th century, during the boom of railroads in the United States. Through rapid late-19th century ...

cut wages as demands for their train cars plummeted and the company's revenue dropped. A delegation of workers complained of the low wages and twelve-hour workdays, and that the corporation that operated the town of Pullman didn't decrease rents, but company owner George Pullman

George Mortimer Pullman (March 3, 1831 â October 19, 1897) was an American engineer and industrialist. He designed and manufactured the Pullman sleeping car and founded a company town, Pullman, for the workers who manufactured it. This ulti ...

"loftily declined to talk with them."Lukas, Anthony. ''Big Trouble'', 1997, page 310. The boycott was launched on June 26, 1894. Within four days, 125,000 workers on twenty-nine railroads had quit work rather than handle Pullman cars. Adding fuel to the fire the railroad companies began hiring replacement workers (that is, strikebreaker

A strikebreaker (sometimes called a scab, blackleg, or knobstick) is a person who works despite a strike. Strikebreakers are usually individuals who were not employed by the company before the trade union dispute but hired after or during the st ...

s), which only increased hostilities. Many African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

s, fearful that the racism expressed by the American Railway Union would lock them out of another labor market, crossed the picket line to break the strike; thus adding a racially charged tone to the conflict.

* 1896: The 1896 United States presidential election

The 1896 United States presidential election was the 28th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 3, 1896. Former Governor William McKinley, the Republican candidate, defeated former Representative William Jennings Bryan, t ...

becomes a political realignment

A political realignment, often called a critical election, critical realignment, or realigning election, in the academic fields of political science and political history, is a set of sharp changes in party ideology, issues, party leaders, regional ...

. The monetary policy

Monetary policy is the policy adopted by the monetary authority of a nation to control either the interest rate payable for very short-term borrowing (borrowing by banks from each other to meet their short-term needs) or the money supply, often a ...

standard supported by the candidates of the two major parties arguably dominated their electoral campaigns. William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 â July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the Democratic Party, running three times as the party's nominee for President ...

, candidate of the ruling Democratic Party campaigned on a policy of Free Silver. His opponent William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

of the Republican Party, which had lost elections in 1884 and 1892, campaigned on a policy of Sound Money and maintaining the gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the l ...

in effect since the 1870s. The "shorthand slogans" actually reflected "broader philosophies of finance and public policy, and opposing beliefs about justice, order, and 'moral economy

Moral economy refers to economic activities viewed through a moral, not just a material, lens. The definition of moral economy is constantly revisited depending on its usage in differing social, economic, ecological, and geographic situations and ...

.'", The Republicans won the election and would win every election to 1912. Arguably ending the so-called Gilded Age

In United States history, the Gilded Age was an era extending roughly from 1877 to 1900, which was sandwiched between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was a time of rapid economic growth, especially in the Northern and Wes ...

. The McKinley administration would embrace American imperialism

American imperialism refers to the expansion of American political, economic, cultural, and media influence beyond the boundaries of the United States. Depending on the commentator, it may include imperialism through outright military conques ...

, its involvement in the SpanishâAmerican War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

(1896â1898) leading the United States in playing a more active role in the world scene. The term Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s â late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

has been suggested for the period, though often covering the reforms lasting from the 1880s to the 1920s.

* 1896â1897:

* 1896â1897: Leadville Colorado, Miners' Strike

The Leadville miners' strike was a labor action by the Cloud City Miners' Union, which was the Leadville, Colorado local of the Western Federation of Miners (WFM), against those silver mines paying less than $3.00 per day. The strike lasted from 1 ...

. The union local in the Leadville mining district

The Leadville mining district, located in the Colorado Mineral Belt, was the most productive silver-mining district in the state of Colorado and hosts one of the largest lead-zinc-silver deposits in the world. Oro City, Colorado, Oro City, an ...

was the Cloud City Miners' Union (CCMU), Local 33 of the Western Federation of Miners

The Western Federation of Miners (WFM) was a trade union, labor union that gained a reputation for militancy in the mining#Human Rights, mines of the western United States and British Columbia. Its efforts to organize both hard rock miners and ...