The Holy Roman Empire was a

political entity

A polity is an identifiable political entity – a group of people with a collective identity, who are organized by some form of institutionalized social relations, and have a capacity to mobilize resources. A polity can be any other group of p ...

in

Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

,

Central, and

Southern Europe

Southern Europe is the southern region of Europe. It is also known as Mediterranean Europe, as its geography is essentially marked by the Mediterranean Sea. Definitions of Southern Europe include some or all of these countries and regions: Alba ...

that developed during the

Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

and continued until its

dissolution in 1806 during the

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

.

From the accession of

Otto I

Otto I (23 November 912 – 7 May 973), traditionally known as Otto the Great (german: Otto der Große, it, Ottone il Grande), was East Frankish king from 936 and Holy Roman Emperor from 962 until his death in 973. He was the oldest son of He ...

in 962 until the twelfth century, the Empire was the most powerful monarchy in Europe. Andrew Holt characterizes it as "perhaps the most powerful European state of the Middle Ages". The functioning of government depended on the harmonic cooperation (dubbed ''consensual rulership'' by Bernd Schneidmüller) between monarch and vassals but this harmony was disturbed during the

Salian

The Salian dynasty or Salic dynasty (german: Salier) was a dynasty in the High Middle Ages. The dynasty provided four kings of Germany (1024–1125), all of whom went on to be crowned Holy Roman emperors (1027–1125).

After the death of the l ...

period. The empire reached the apex of territorial expansion and power under the

House of Hohenstaufen

The Hohenstaufen dynasty (, , ), also known as the Staufer, was a noble family of unclear origin that rose to rule the Duchy of Swabia from 1079, and to royal rule in the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages from 1138 until 1254. The dynast ...

in the mid-thirteenth century, but overextending led to partial collapse.

On 25 December 800,

Pope Leo III crowned the

Frankish king

The Franks, Germanic-speaking peoples that invaded the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, were first led by individuals called dukes and reguli. The earliest group of Franks that rose to prominence was the Salian Merovingians, who con ...

Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first ...

as

emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereignty, sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), ...

, reviving the title in

Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

, more than three centuries after the

fall

Autumn, also known as fall in American English and Canadian English, is one of the four temperate seasons on Earth. Outside the tropics, autumn marks the transition from summer to winter, in September (Northern Hemisphere) or March ( Southe ...

of the earlier ancient

Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period ...

in 476. In theory and diplomacy, the emperors were considered ''

primus inter pares'', regarded as first among equals among other Catholic monarchs across Europe. The title continued in the

Carolingian family

The Carolingian dynasty (; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Franks, Frankish noble family named after Charlemagne, grandson of Mayor of the palace, mayor Charles Martel and a descendant ...

until 888 and from 896 to 899, after which it was contested by the rulers of Italy in a series of civil wars until the death of the last Italian claimant,

Berengar I, in 924. The title was revived again in 962 when

Otto I

Otto I (23 November 912 – 7 May 973), traditionally known as Otto the Great (german: Otto der Große, it, Ottone il Grande), was East Frankish king from 936 and Holy Roman Emperor from 962 until his death in 973. He was the oldest son of He ...

, King of Germany, was crowned emperor by

Pope John XII

Pope John XII ( la, Ioannes XII; c. 930/93714 May 964), born Octavian, was the bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 16 December 955 to his death in 964. He was related to the counts of Tusculum, a powerful Roman family which had do ...

, fashioning himself as the successor of Charlemagne and beginning a continuous existence of the empire for over eight centuries.

Some historians refer to the coronation of Charlemagne as the origin of the empire, while others prefer the coronation of Otto I as its beginning.

Henry the Fowler, the founder of the

medieval German state (ruled 919–936), has sometimes been considered the founder of the Empire as well. The modern view favours Otto as the true founder. Scholars generally concur in relating an evolution of the institutions and principles constituting the empire, describing a gradual assumption of the imperial title and role.

The exact term "Holy Roman Empire" was not used until the 13th century, but the Emperor's legitimacy always rested on the concept of ''

translatio imperii

''Translatio imperii'' (Latin for "transfer of rule") is a historiographical concept that originated from the Middle Ages, in which history is viewed as a linear succession of transfers of an ''imperium'' that invests supreme power in a singular r ...

'', that he held supreme power inherited from the ancient emperors of

Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

. The imperial office was traditionally elective through the mostly German

prince-elector

The prince-electors (german: Kurfürst pl. , cz, Kurfiřt, la, Princeps Elector), or electors for short, were the members of the electoral college that elected the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

From the 13th century onwards, the prin ...

s.

During the final phase of the reign of Emperor

Frederick III (ruled 1452–1493),

Imperial Reform

Imperial Reform ( la, Reformatio imperii, german: Reichsreform) is the name given to repeated attempts in the 15th and 16th centuries to adapt the structure and the constitutional order () of the Holy Roman Empire to the requirements of the early ...

began. The reform would largely be materialized during

Maximilian I's rule (from 1486 as King of the Romans, from 1493 as sole ruler, and from 1508 as Holy Roman Emperor, until his death in 1519). The Empire transformed into the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation. It was during this time that the Empire gained most of its institutions that endured until its final demise in the nineteenth century. Thomas Brady Jr. opines that the Imperial Reform was successful, although perhaps at the expense of the reform of the Church, partly because Maximilian was not really serious about the religious matter.

According to Brady Jr., the Empire, after the Imperial Reform, was a political body of remarkable longevity and stability, and "resembled in some respects the monarchical polities of Europe's western tier, and in others the loosely integrated, elective polities of East Central Europe." The new corporate German Nation, instead of simply obeying the emperor, negotiated with him. On 6 August 1806, Emperor

Francis II dissolved the empire following the creation of the

Confederation of the Rhine

The Confederated States of the Rhine, simply known as the Confederation of the Rhine, also known as Napoleonic Germany, was a confederation of German client states established at the behest of Napoleon some months after he defeated Austria an ...

by

Emperor of the French

Emperor of the French (French: ''Empereur des Français'') was the title of the monarch and supreme ruler of the First and the Second French Empires.

Details

A title and office used by the House of Bonaparte starting when Napoleon was procla ...

Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

the month before.

Name and general perception

The Empire was considered by the Roman Catholic Church to be the only legal successor of the Roman Empire during the Middle Ages and the early modern period. Since Charlemagne, the realm was merely referred to as the ''Roman Empire''. The term ''sacrum'' ("holy", in the sense of "consecrated") in connection with the medieval Roman Empire was used beginning in 1157 under

Frederick I Barbarossa

Frederick Barbarossa (December 1122 – 10 June 1190), also known as Frederick I (german: link=no, Friedrich I, it, Federico I), was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1155 until his death 35 years later. He was elected King of Germany in Frankfurt o ...

("Holy Empire"): the term was added to reflect Frederick's ambition to dominate Italy and the

Papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

.

[Whaley 2011, p. 17] The form "Holy Roman Empire" is attested from 1254 onward.

The exact term "Holy Roman Empire" was not used until the 13th century, before which the empire was referred to variously as ''universum regnum'' ("the whole kingdom", as opposed to the regional kingdoms), ''imperium christianum'' ("Christian empire"), or ''Romanum imperium'' ("Roman empire"), but the Emperor's legitimacy always rested on the concept of ''

translatio imperii

''Translatio imperii'' (Latin for "transfer of rule") is a historiographical concept that originated from the Middle Ages, in which history is viewed as a linear succession of transfers of an ''imperium'' that invests supreme power in a singular r ...

'', that he held supreme power inherited from the ancient emperors of

Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

.

In a decree following the

Diet of Cologne in 1512, the name was changed to the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (german: Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation, la, Sacrum Imperium Romanum Nationis Germanicæ), a form first used in a document in 1474.

The new title was adopted partly because the Empire lost most of its territories in Italy and

Burgundy to the south and west by the late 15th century, but also to emphasize the new importance of the German

Imperial Estate

An Imperial State or Imperial Estate ( la, Status Imperii; german: Reichsstand, plural: ') was a part of the Holy Roman Empire with representation and the right to vote in the Imperial Diet ('). Rulers of these Estates were able to exercise si ...

s in ruling the Empire due to the

Imperial Reform

Imperial Reform ( la, Reformatio imperii, german: Reichsreform) is the name given to repeated attempts in the 15th and 16th centuries to adapt the structure and the constitutional order () of the Holy Roman Empire to the requirements of the early ...

. The Hungarian denomination "German Roman Empire" () is the shortening of this.

By the end of the 18th century, the term "Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation" fell out of official use. Contradicting the traditional view concerning that designation, Hermann Weisert has argued in a study on imperial titulature that, despite the claims of many textbooks, the name ''"Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation"'' never had an official status and points out that documents were thirty times as likely to omit the national suffix as include it.

In a famous assessment of the name, the political philosopher

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—es ...

remarked sardonically: "This body which was called and which still calls itself the Holy Roman Empire was in no way holy, nor Roman, nor an empire."

In the modern period, the Empire was often informally called the ''German Empire'' () or ''Roman-German Empire'' (). After its dissolution through the end of the

German Empire, it was often called "the old Empire" (). Beginning in 1923, early twentieth-century German nationalists and

Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

propaganda would identify the Holy Roman Empire as the "First" Reich (''Erstes Reich'', ''Reich'' meaning empire), with the

German Empire as the "Second" Reich and what would eventually become

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

as the "Third" Reich.

David S. Bachrach opines that the Ottonian kings, above all

Henry the Fowler and

Otto the Great, actually built their empire (which became the hegemonic state of Western Europe, with the leading role of the Kingdom of Germany) on the back of military and bureaucratic apparati as well as cultural legacy they inherited from the Carolingians, who ultimately inherited these from the Late Roman Empire:

Consequently, Henry I Henry I may refer to:

876–1366

* Henry I the Fowler, King of Germany (876–936)

* Henry I, Duke of Bavaria (died 955)

* Henry I of Austria, Margrave of Austria (died 1018)

* Henry I of France (1008–1060)

* Henry I the Long, Margrave of the ...

and Otto I

Otto I (23 November 912 – 7 May 973), traditionally known as Otto the Great (german: Otto der Große, it, Ottone il Grande), was East Frankish king from 936 and Holy Roman Emperor from 962 until his death in 973. He was the oldest son of He ...

, did not begin ''de novo'' to develop a military, administrative, and intellectual infrastructure for their kingdom and empire. They built upon the existing structures that they had inherited from their Carolingian predecessors. An argument for continuity should not, however, be confused with a claim for stasis. The Ottonians, just like their Carolingian predecessors, developed and refined their material, cultural, intellectual, and administrative inheritance in ways that fit their own time. It was the success of the Ottonians in molding the raw materials bequeathed to them into a formidable military machine that made possible the establishment of Germany as the preeminent kingdom in Europe from the tenth through the mid-thirteenth century ..the Carolingians built upon the military organization that they had inherited from their Merovingian and ultimately late-Roman predecessors."

Bachrach argues that the Ottonian empire was hardly an archaic kingdom of primitive Germans, maintained by personal relationships only and driven by the desire of the magnates to plunder and divide the rewards among themselves (as argued by Timothy Reuter), but instead, notable for their abilities to amass sophisticated economic, administrative, educational and cultural resources that they used to serve their enormous war machine.

Until the end of the 15th century, the empire was in theory composed of three major blocks –

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

,

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and

Burgundy. Later territorially only the Kingdom of Germany and Bohemia remained, with the Burgundian territories lost to

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

. Although the Italian territories were formally part of the empire, the territories were ignored in the

Imperial Reform

Imperial Reform ( la, Reformatio imperii, german: Reichsreform) is the name given to repeated attempts in the 15th and 16th centuries to adapt the structure and the constitutional order () of the Holy Roman Empire to the requirements of the early ...

and splintered into numerous

de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with ''de jure'' ("by la ...

independent territorial entities.

The status of Italy in particular varied throughout the 16th to 18th centuries. Some territories like

Piedmont-Savoy became increasingly independent, while others became more dependent due to the extinction of their ruling noble houses causing these territories to often fall under the dominions of the

Habsburgs and their

cadet branch

In history and heraldry, a cadet branch consists of the male-line descendants of a monarch's or patriarch's younger sons ( cadets). In the ruling dynasties and noble families of much of Europe and Asia, the family's major assets— realm, tit ...

es. Barring

the loss of Franche-Comté in 1678, the external borders of the Empire did not change noticeably from the

Peace of Westphalia – which acknowledged the exclusion of Switzerland and the Northern Netherlands, and the French protectorate over Alsace – to the dissolution of the Empire. At the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, most of the Holy Roman Empire was included in the

German Confederation

The German Confederation (german: Deutscher Bund, ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, w ...

, with the main exceptions being the Italian states.

History

Early Middle Ages

Carolingian period

As

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

power in

Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

declined during the 5th century, local Germanic tribes assumed control. In the late 5th and early 6th centuries, the

Merovingians

The Merovingian dynasty () was the ruling family of the Franks from the middle of the 5th century until 751. They first appear as "Kings of the Franks" in the Roman army of northern Gaul. By 509 they had united all the Franks and northern Gauli ...

, under

Clovis I and his successors, consolidated

Frankish

Frankish may refer to:

* Franks, a Germanic tribe and their culture

** Frankish language or its modern descendants, Franconian languages

* Francia, a post-Roman state in France and Germany

* East Francia, the successor state to Francia in Germany ...

tribes and extended hegemony over others to gain control of northern Gaul and the middle

Rhine river

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, source ...

valley region. By the middle of the 8th century, however, the Merovingians were reduced to figureheads, and the

Carolingians, led by

Charles Martel

Charles Martel ( – 22 October 741) was a Frankish political and military leader who, as Duke and Prince of the Franks and Mayor of the Palace, was the de facto ruler of Francia from 718 until his death. He was a son of the Frankish statesm ...

, became the ''de facto'' rulers. In 751, Martel's son

Pepin became King of the Franks, and later gained the sanction of the Pope.

The Carolingians would maintain a close alliance with the Papacy.

In 768, Pepin's son

Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first ...

became King of the Franks and began an extensive expansion of the realm. He eventually incorporated the territories of present-day France, Germany, northern Italy, the Low Countries and beyond, linking the Frankish kingdom with Papal lands.

Although antagonism about the expense of

Byzantine domination had long persisted within Italy, a political rupture was set in motion in earnest in 726 by the

iconoclasm

Iconoclasm (from Greek: grc, εἰκών, lit=figure, icon, translit=eikṓn, label=none + grc, κλάω, lit=to break, translit=kláō, label=none)From grc, εἰκών + κλάω, lit=image-breaking. ''Iconoclasm'' may also be conside ...

of Emperor

Leo III the Isaurian

Leo III the Isaurian ( gr, Λέων ὁ Ἴσαυρος, Leōn ho Isauros; la, Leo Isaurus; 685 – 18 June 741), also known as the Syrian, was Byzantine Emperor from 717 until his death in 741 and founder of the Isaurian dynasty. He put an e ...

, in what

Pope Gregory II

Pope Gregory II ( la, Gregorius II; 669 – 11 February 731) was the bishop of Rome from 19 May 715 to his death. saw as the latest in a series of imperial heresies. In 797, the Eastern Roman Emperor

Constantine VI

Constantine VI ( gr, Κωνσταντῖνος, ''Kōnstantinos''; 14 January 771 – before 805Cutler & Hollingsworth (1991), pp. 501–502) was Byzantine emperor from 780 to 797. The only child of Emperor Leo IV, Constantine was named co-emp ...

was removed from the throne by his mother

Irene

Irene is a name derived from εἰρήνη (eirēnē), the Greek for "peace".

Irene, and related names, may refer to:

* Irene (given name)

Places

* Irene, Gauteng, South Africa

* Irene, South Dakota, United States

* Irene, Texas, United Stat ...

who declared herself Empress. As the Latin Church only regarded a male Roman Emperor as the head of

Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwine ...

, Pope Leo III sought a new candidate for the dignity, excluding consultation with the

Patriarch of Constantinople.

[Bryce, pp. 44, 50–52]

Charlemagne's good service to the Church in his defense of Papal possessions against the

Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the '' History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 an ...

made him the ideal candidate. On Christmas Day of 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne emperor, restoring the title in the West for the first time in over three centuries.

This can be seen as symbolic of the papacy turning away from the declining

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

towards the new power of

Carolingian Francia

Francia, also called the Kingdom of the Franks ( la, Regnum Francorum), Frankish Kingdom, Frankland or Frankish Empire ( la, Imperium Francorum), was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks dur ...

. Charlemagne adopted the formula ''

Renovatio imperii Romanorum

''Renovatio imperii Romanorum'' ("renewal of the empire of the Romans") was a formula declaring an intention to restore or revive the Roman Empire. The formula (and variations) was used by several emperors of the Carolingian and Ottonian dynasti ...

'' ("renewal of the Roman Empire"). In 802, Irene was overthrown and exiled by

Nikephoros I and henceforth there were two Roman Emperors.

After Charlemagne died in 814, the imperial crown passed to his son,

Louis the Pious

Louis the Pious (german: Ludwig der Fromme; french: Louis le Pieux; 16 April 778 – 20 June 840), also called the Fair, and the Debonaire, was King of the Franks and co-emperor with his father, Charlemagne, from 813. He was also King of Aqui ...

. Upon Louis' death in 840, it passed to his son

Lothair, who was his co-ruler. By this point the territory of Charlemagne was divided into several territories (''cf''.

Treaty of Verdun

The Treaty of Verdun (), agreed in , divided the Frankish Empire into three kingdoms among the surviving sons of the emperor Louis I, the son and successor of Charlemagne. The treaty was concluded following almost three years of civil war and ...

,

Treaty of Prüm

The Treaty of Prüm, concluded on 19 September 855, was the second of the partition treaties of the Carolingian Empire. As Emperor Lothair I was approaching death, he divided his realm of Middle Francia among his three sons.

Background

From ...

,

Treaty of Meerssen

The Treaty of Mersen or Meerssen, concluded on 8 August 870, was a treaty to partition the realm of Lothair II, known as Lotharingia, by his uncles Louis the German of East Francia and Charles the Bald of West Francia, the two surviving sons of ...

and

Treaty of Ribemont

, Participants = Louis the Younger, Louis III of France, Carloman II

, Location = Ribemont

, Date = 880

, Result = All of Lotharingia given to East Francia

The Treaty of Ribemont in 880 was the last treaty on th ...

), and over the course of the later ninth century the title of Emperor was disputed by the Carolingian rulers of the Western Frankish Kingdom or

West Francia

In medieval history, West Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the West Franks () refers to the western part of the Frankish Empire established by Charlemagne. It represents the earliest stage of the Kingdom of France, lasting from about ...

and the Eastern Frankish Kingdom or

East Francia, with first the western king (

Charles the Bald

Charles the Bald (french: Charles le Chauve; 13 June 823 – 6 October 877), also known as Charles II, was a 9th-century king of West Francia (843–877), king of Italy (875–877) and emperor of the Carolingian Empire (875–877). After a ...

) and then the eastern (

Charles the Fat

Charles III (839 – 13 January 888), also known as Charles the Fat, was the emperor of the Carolingian Empire from 881 to 888. A member of the Carolingian dynasty, Charles was the youngest son of Louis the German and Hemma, and a great-grandso ...

), who briefly reunited the Empire, attaining the prize. In the ninth century, Charlemagne and his successors promoted the intellectual revival, known as the

Carolingian Renaissance. Some, like Mortimer Chambers, opine that the Carolingian Renaissance made possible the subsequent renaissances (even though by the early tenth century, the revival already diminished).

After the death of Charles the Fat in 888, the Carolingian Empire broke apart, and was never restored. According to

Regino of Prüm

Regino of Prüm or of Prum ( la, Regino Prumiensis, german: Regino von Prüm; died 915 AD) was a Benedictine monk, who served as abbot of Prüm (892–99) and later of Saint Martin's at Trier, and chronicler, whose ''Chronicon'' is an important so ...

, the parts of the realm "spewed forth kinglets", and each part elected a kinglet "from its own bowels". At this point in time, those crowned emperor by the pope controlled only territories in Italy. The last such emperor was

Berengar I of Italy

Berengar I ( la, Berengarius, Perngarius; it, Berengario; – 7 April 924) was the king of Italy from 887. He was Holy Roman Emperor between 915 and his death in 924. He is usually known as Berengar of Friuli, since he ruled the March of Fri ...

, who died in 924.

Post-Carolingian Eastern Frankish Kingdom

Around 900, East Francia's autonomous

stem duchies (

Franconia

Franconia (german: Franken, ; Franconian dialect: ''Franggn'' ; bar, Frankn) is a region of Germany, characterised by its culture and Franconian languages, Franconian dialect (German: ''Fränkisch'').

The three Regierungsbezirk, administrative ...

,

Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

,

Swabia,

Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

, and

Lotharingia

Lotharingia ( la, regnum Lotharii regnum Lothariense Lotharingia; french: Lotharingie; german: Reich des Lothar Lotharingien Mittelreich; nl, Lotharingen) was a short-lived medieval successor kingdom of the Carolingian Empire. As a more durable ...

) reemerged. After the Carolingian king

Louis the Child

Louis the Child (893 – 20/24 September 911), sometimes called Louis III or Louis IV, was the king of East Francia from 899 until his death and was also recognized as king of Lotharingia after 900. He was the last East Frankish ruler of the Car ...

died without issue in 911,

East Francia did not turn to the Carolingian ruler of West Francia to take over the realm but instead elected one of the dukes,

Conrad of Franconia

Conrad I (; c. 881 – 23 December 918), called the Younger, was the king of East Francia from 911 to 918. He was the first king not of the Carolingian dynasty, the first to be elected by the nobility and the first to be anointed. He was chosen as ...

, as ''Rex Francorum Orientalium''. On his deathbed, Conrad yielded the crown to his main rival,

Henry the Fowler of Saxony (r. 919–36), who was elected king at the Diet of

Fritzlar in 919. Henry reached a truce with the raiding

Magyars, and in 933 he won a first victory against them in the

Battle of Riade

The Battle of Riade or Battle of Merseburg was fought between the troops of East Francia under King Henry I and the Magyars at an unidentified location in northern Thuringia along the river Unstrut on 15 March 933. The battle was precipitated b ...

.

Henry died in 936, but his descendants, the

Liudolfing (or Ottonian) dynasty, would continue to rule the Eastern kingdom or the Kingdom of Germany for roughly a century. Upon Henry the Fowler's death,

Otto

Otto is a masculine German given name and a surname. It originates as an Old High German short form (variants ''Audo'', '' Odo'', ''Udo'') of Germanic names beginning in ''aud-'', an element meaning "wealth, prosperity".

The name is recorded f ...

, his son and designated successor, was elected King in

Aachen in 936. He overcame a series of revolts from a younger brother and from several dukes. After that, the king managed to control the appointment of dukes and often also employed bishops in administrative affairs. He replaced leaders of most of the major East Frankish duchies with his own relatives. At the same time, he was careful to prevent members of his own family from making infringements on his royal prerogatives.

Formation of the Holy Roman Empire

In 951, Otto came to the aid of

Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

, the widowed queen of Italy, defeating her enemies, marrying her, and taking control over Italy. In 955, Otto won a decisive victory over the

Magyars in the

Battle of Lechfeld

The Battle of Lechfeld was a series of military engagements over the course of three days from 10–12 August 955 in which the Kingdom of Germany, led by King Otto I the Great, annihilated the Hungarian army led by ''Harka ''Bulcsú and the chi ...

. In 962, Otto was crowned emperor by

Pope John XII

Pope John XII ( la, Ioannes XII; c. 930/93714 May 964), born Octavian, was the bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 16 December 955 to his death in 964. He was related to the counts of Tusculum, a powerful Roman family which had do ...

, thus intertwining the affairs of the German kingdom with those of Italy and the Papacy. Otto's coronation as Emperor marked the German kings as successors to the Empire of Charlemagne, which through the concept of ''

translatio imperii

''Translatio imperii'' (Latin for "transfer of rule") is a historiographical concept that originated from the Middle Ages, in which history is viewed as a linear succession of transfers of an ''imperium'' that invests supreme power in a singular r ...

'', also made them consider themselves as successors to Ancient Rome. The flowering of arts beginning with Otto the Great's reign is known as the

Ottonian Renaissance, centered in Germany but also happening in Northern Italy and France.

Otto created the imperial church system, often called "Ottonian church system of the Reich", which tied the great imperial churches and their representatives to imperial service, thus providing "a stable and long-lasting framework for Germany".

During the Ottonian era, imperial women played a prominent role in political and ecclesiastic affairs, often combining their functions as religious leader and advisor, regent or co-ruler, notably

Matilda of Ringelheim,

Eadgyth

Edith of England, also spelt Eadgyth or Ædgyth ( ang, Ēadgȳð, german: Edgitha; 910 – 946), a member of the House of Wessex, was a German queen from 936, by her marriage to King Otto I.

Life

Edith was born to the reigning English king Edw ...

,

Adelaide of Italy

Adelaide of Italy (german: Adelheid; 931 – 16 December 999 AD), also called Adelaide of Burgundy, was Holy Roman Empress by marriage to Emperor Otto the Great; she was crowned with him by Pope John XII in Rome on 2 February 962. She was the ...

,

Theophanu

Theophanu (; also ''Theophania'', ''Theophana'', or ''Theophano''; Medieval Greek ; AD 955 15 June 991) was empress of the Holy Roman Empire by marriage to Emperor Otto II, and regent of the Empire during the minority of their son, Emperor O ...

,

Matilda of Quedlinburg.

In 963, Otto deposed the current Pope John XII and chose

Pope Leo VIII

Pope Leo VIII ( 915 – 1 March 965) was a Roman prelate who claimed the Holy See from 963 until 964 in opposition to John XII and Benedict V and again from 23 June 964 to his death. Today he is considered by the Catholic Church to have bee ...

as the new pope (although John XII and Leo VIII both claimed the papacy until 964 when John XII died). This also renewed the conflict with the

Eastern Emperor in Constantinople, especially after Otto's son

Otto II

Otto II (955 – 7 December 983), called the Red (''der Rote''), was Holy Roman Emperor from 973 until his death in 983. A member of the Ottonian dynasty, Otto II was the youngest and sole surviving son of Otto the Great and Adelaide of Ita ...

(r. 967–83) adopted the designation ''imperator Romanorum''. Still, Otto II formed marital ties with the east when he married the Byzantine princess

Theophanu

Theophanu (; also ''Theophania'', ''Theophana'', or ''Theophano''; Medieval Greek ; AD 955 15 June 991) was empress of the Holy Roman Empire by marriage to Emperor Otto II, and regent of the Empire during the minority of their son, Emperor O ...

. Their son,

Otto III, came to the throne only three years old, and was subjected to a power struggle and series of regencies until his age of majority in 994. Up to that time, he remained in Germany, while a deposed duke,

Crescentius II

Crescentius the Younger (or Crescentius II; died 29 April 998), son of Crescentius the Elder, was a leader of the aristocracy of medieval Rome. During the minority of Holy Roman Emperor Otto III, he declared himself Consul (or Senator) of Rome ( ...

, ruled over Rome and part of Italy, ostensibly in his stead.

In 996 Otto III appointed his cousin

Gregory V

Gregory may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Gregory (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Gregory (surname), a surname

Places Australia

* Gregory, Queensland, a town in the Shire o ...

the first German Pope. A foreign pope and foreign papal officers were seen with suspicion by Roman nobles, who were led by

Crescentius II

Crescentius the Younger (or Crescentius II; died 29 April 998), son of Crescentius the Elder, was a leader of the aristocracy of medieval Rome. During the minority of Holy Roman Emperor Otto III, he declared himself Consul (or Senator) of Rome ( ...

to revolt. Otto III's former mentor

Antipope John XVI

John XVI ( 945 – 1001; born gr, Ιωάννης Φιλάγαθος, Ioannis Philagathos; it, Giovanni Filagato; la, Johannes Philagathus) was an antipope from 997 to 998.

Biography

John was of Greek descent and was a native of Rossan ...

briefly held Rome, until the

Holy Roman Emperor seized the city.

Otto died young in 1002, and was succeeded by his cousin

Henry II, who focused on Germany.

Otto III's (and his mentor Pope Sylvester's) diplomatic activities coincided with and facilitated the Christianization and the spread of Latin culture in different parts of Europe. They coopted a new group of nations (Slavic) into the framework of Europe, with their empire functioning, as some remark, as a "Byzantine-like presidency over a family of nations, centred on pope and emperor in Rome", has proved a lasting achievement. Otto's early death though made his reign "the tale of largely unrealized potential".

Henry II died in 1024 and

Conrad II, first of the

Salian dynasty

The Salian dynasty or Salic dynasty (german: Salier) was a dynasty in the High Middle Ages. The dynasty provided four kings of Germany (1024–1125), all of whom went on to be crowned Holy Roman emperors (1027–1125).

After the death of the l ...

, was elected king only after some debate among dukes and nobles. This group eventually developed into the college of

Electors.

The Holy Roman Empire eventually came to be composed of four kingdoms. The kingdoms were:

*

Kingdom of Germany

The Kingdom of Germany or German Kingdom ( la, regnum Teutonicorum "kingdom of the Germans", "German kingdom", "kingdom of Germany") was the mostly Germanic-speaking East Frankish kingdom, which was formed by the Treaty of Verdun in 843, especi ...

(part of the empire since 962),

*

Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to an institutional referendum to abandon the monarchy and f ...

(from 962 until 1801),

*

Kingdom of Bohemia

The Kingdom of Bohemia ( cs, České království),; la, link=no, Regnum Bohemiae sometimes in English literature referred to as the Czech Kingdom, was a medieval and early modern monarchy in Central Europe, the predecessor of the modern Czec ...

(from 1002 as the

Duchy of Bohemia

The Duchy of Bohemia, also later referred to in English as the Czech Duchy, ( cs, České knížectví) was a monarchy and a principality of the Holy Roman Empire in Central Europe during the Early and High Middle Ages. It was formed around 870 b ...

and raised to a kingdom in 1198),

*

Kingdom of Burgundy

Kingdom of Burgundy was a name given to various states located in Western Europe during the Middle Ages. The historical Burgundy correlates with the border area of France, Italy and Switzerland and includes the major modern cities of Geneva and ...

(from 1032 to 1378).

High Middle Ages

Investiture controversy

Kings often employed bishops in administrative affairs and often determined who would be appointed to ecclesiastical offices. In the wake of the

Cluniac Reforms

The Cluniac Reforms (also called the Benedictine Reform) were a series of changes within medieval monasticism of the Western Church focused on restoring the traditional monastic life, encouraging art, and caring for the poor. The movement began wi ...

, this involvement was increasingly seen as inappropriate by the Papacy. The reform-minded

Pope Gregory VII was determined to oppose such practices, which led to the

Investiture Controversy

The Investiture Controversy, also called Investiture Contest ( German: ''Investiturstreit''; ), was a conflict between the Church and the state in medieval Europe over the ability to choose and install bishops ( investiture) and abbots of mona ...

with

Henry IV (r. 1056–1106), the King of the Romans and Holy Roman Emperor.

Henry IV repudiated the Pope's interference and persuaded his bishops to excommunicate the Pope, whom he famously addressed by his born name "Hildebrand", rather than his regnal name "Pope Gregory VII". The Pope, in turn, excommunicated the king, declared him deposed, and dissolved the oaths of loyalty made to Henry.

The king found himself with almost no political support and was forced to make the famous

Walk to Canossa

The Humiliation of Canossa ( it, L'umiliazione di Canossa), sometimes called the Walk to Canossa (german: Gang nach Canossa/''Kanossa'') or the Road to Canossa, was the ritual submission of the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry IV to Pope Gregory VII ...

in 1077, by which he achieved a lifting of the excommunication at the price of humiliation. Meanwhile, the German princes had elected another king,

Rudolf of Swabia

Rudolf of Rheinfelden ( – 15 October 1080) was Duke of Swabia from 1057 to 1079. Initially a follower of his brother-in-law, the Salian emperor Henry IV, his election as German anti-king in 1077 marked the outbreak of the Great Saxon Revolt an ...

.

Henry managed to defeat Rudolf, but was subsequently confronted with more uprisings, renewed excommunication, and even the rebellion of his sons. After his death, his second son,

Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (c. 1173–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (1 ...

, reached an agreement with the Pope and the bishops in the 1122

Concordat of Worms. The political power of the Empire was maintained, but the conflict had demonstrated the limits of the ruler's power, especially in regard to the Church, and it robbed the king of the sacral status he had previously enjoyed. The Pope and the German princes had surfaced as major players in the political system of the empire.

Ostsiedlung

As the result of

Ostsiedlung, less-populated regions of Central Europe (i.e. sparsely populated border areas in present-day Poland and the Czech Republic) received a significant number of German speakers.

Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

became part of the Holy Roman Empire as the result of the local

Piast dukes' push for autonomy from the Polish Crown.

From the late 12th century, the

Duchy of Pomerania

The Duchy of Pomerania (german: Herzogtum Pommern; pl, Księstwo Pomorskie; Latin: ''Ducatus Pomeraniae'') was a duchy in Pomerania on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, ruled by dukes of the House of Pomerania (''Griffins''). The country ha ...

was under the

suzerainty of the Holy Roman Empire and the conquests of the

Teutonic Order

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians on ...

made that region German-speaking.

Hohenstaufen dynasty

When the Salian dynasty ended with Henry V's death in 1125, the princes chose not to elect the next of kin, but rather

Lothair, the moderately powerful but already old Duke of Saxony. When he died in 1137, the princes again aimed to check royal power; accordingly they did not elect Lothair's favoured heir, his son-in-law

Henry the Proud

Henry the Proud (german: Heinrich der Stolze) (20 October 1139), a member of the House of Welf, was Duke of Bavaria (as Henry X) from 1126 to 1138 and Duke of Saxony (as Henry II) as well as Margrave of Tuscany and Duke of Spoleto fro ...

of the

Welf Welf is a Germanic first name that may refer to:

*Welf (father of Judith), 9th century Frankish count, father-in-law of Louis the Pious

*Welf I, d. bef. 876, count of Alpgau and Linzgau

*Welf II, Count of Swabia, died 1030, supposed descendant of W ...

family, but

Conrad III of the

Hohenstaufen

The Hohenstaufen dynasty (, , ), also known as the Staufer, was a noble family of unclear origin that rose to rule the Duchy of Swabia from 1079, and to royal rule in the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages from 1138 until 1254. The dynast ...

family, the grandson of Emperor Henry IV and thus a nephew of Emperor Henry V. This led to over a century of strife between the two houses. Conrad ousted the Welfs from their possessions, but after his death in 1152, his nephew

Frederick I "Barbarossa" succeeded him and made peace with the Welfs, restoring his cousin

Henry the Lion

Henry the Lion (german: Heinrich der Löwe; 1129/1131 – 6 August 1195) was a member of the Welf dynasty who ruled as the duke of Saxony and Bavaria from 1142 and 1156, respectively, until 1180.

Henry was one of the most powerful German p ...

to his – albeit diminished – possessions.

The Hohenstaufen rulers increasingly lent land to ''ministerialia'', formerly non-free servicemen, who Frederick hoped would be more reliable than dukes. Initially used mainly for war services, this new class of people would form the basis for the later

knights, another basis of imperial power. A further important constitutional move at Roncaglia was the establishment of a new peace mechanism for the entire empire, the

Landfrieden

Under the law of the Holy Roman Empire, a ''Landfrieden'' or ''Landfriede'' (Latin: ''constitutio pacis'', ''pax instituta'' or ''pax jurata'', variously translated as "land peace", or "public peace") was a contractual waiver of the use of legiti ...

, with the first imperial one being issued in 1103 under

Henry IV at

Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-west, with Ma ...

.

This was an attempt to abolish private feuds, between the many dukes and other people, and to tie the emperor's subordinates to a legal system of jurisdiction and public prosecution of criminal acts – a predecessor of the modern concept of "

rule of law". Another new concept of the time was the systematic founding of new cities by the Emperor and by the local dukes. These were partly a result of the explosion in population; they also concentrated economic power at strategic locations. Before this, cities had only existed in the form of old Roman foundations or older

bishopric

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associate ...

s. Cities that were founded in the 12th century include

Freiburg

Freiburg im Breisgau (; abbreviated as Freiburg i. Br. or Freiburg i. B.; Low Alemannic: ''Friburg im Brisgau''), commonly referred to as Freiburg, is an independent city in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. With a population of about 230,000 (as o ...

, possibly the economic model for many later cities, and

Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and Ha ...

.

Frederick I Frederick I may refer to:

* Frederick of Utrecht or Frederick I (815/16–834/38), Bishop of Utrecht.

* Frederick I, Duke of Upper Lorraine (942–978)

* Frederick I, Duke of Swabia (1050–1105)

* Frederick I, Count of Zoll ...

, also called Frederick Barbarossa, was crowned emperor in 1155. He emphasized the "Romanness" of the empire, partly in an attempt to justify the power of the emperor independent of the (now strengthened) pope. An imperial assembly at the fields of Roncaglia in 1158 reclaimed imperial rights in reference to

Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renova ...

's

Corpus Juris Civilis

The ''Corpus Juris'' (or ''Iuris'') ''Civilis'' ("Body of Civil Law") is the modern name for a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence, issued from 529 to 534 by order of Justinian I, Byzantine Emperor. It is also sometimes referred ...

. Imperial rights had been referred to as ''regalia'' since the Investiture Controversy but were enumerated for the first time at Roncaglia. This comprehensive list included public roads, tariffs,

coining, collecting punitive fees, and the seating and unseating of office-holders. These rights were now explicitly rooted in

Roman law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the '' Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Ju ...

, a far-reaching constitutional act.

Frederick's policies were primarily directed at Italy, where he clashed with the increasingly wealthy and free-minded cities of the north, especially

Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

. He also embroiled himself in another conflict with the Papacy by supporting a candidate elected by a minority against

Pope Alexander III (1159–81). Frederick supported a succession of

antipopes before finally making peace with Alexander in 1177. In Germany, the Emperor had repeatedly protected Henry the Lion against complaints by rival princes or cities (especially in the cases of

Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and Ha ...

and

Lübeck

Lübeck (; Low German also ), officially the Hanseatic City of Lübeck (german: Hansestadt Lübeck), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 217,000 inhabitants, Lübeck is the second-largest city on the German Baltic coast and in the state ...

). Henry gave only lackluster support to Frederick's policies, and, in a critical situation during the Italian wars, Henry refused the Emperor's plea for military support. After returning to Germany, an embittered Frederick opened proceedings against the Duke, resulting in a public ban and the confiscation of all Henry's territories. In 1190, Frederick participated in the

Third Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) was an attempt by three European monarchs of Western Christianity (Philip II of France, Richard I of England and Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor) to reconquer the Holy Land following the capture of Jerusalem by ...

, dying in the

Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia.

During the Hohenstaufen period, German princes facilitated a successful, peaceful

eastward settlement of lands that were uninhabited or inhabited sparsely by

West Slavs

The West Slavs are Slavic peoples who speak the West Slavic languages. They separated from the common Slavic group around the 7th century, and established independent polities in Central Europe by the 8th to 9th centuries. The West Slavic lan ...

. German-speaking farmers, traders, and craftsmen from the western part of the Empire, both Christians and Jews, moved into these areas. The gradual

Germanization

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, people and culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationalism went hand in hand. In ling ...

of these lands was a complex phenomenon that should not be interpreted in the biased terms of 19th-century

nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

. The eastward settlement expanded the influence of the empire to include

Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

and

Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

, as did the intermarriage of the local, still mostly Slavic, rulers with German spouses. The

Teutonic Knights

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians o ...

were invited to

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

by Duke

Konrad of Masovia

Konrad I of Masovia (ca. 1187/88 – 31 August 1247), from the Polish Piast dynasty, was the sixth Duke of Masovia and Kuyavia from 1194 until his death as well as High Duke of Poland from 1229 to 1232 and again from 1241 to 1243.

Life

Konrad was ...

to Christianize the

Prussians in 1226. The

monastic state of the Teutonic Order

The State of the Teutonic Order (german: Staat des Deutschen Ordens, ; la, Civitas Ordinis Theutonici; lt, Vokiečių ordino valstybė; pl, Państwo zakonu krzyżackiego), also called () or (), was a medieval Crusader state, located in Centr ...

(german: Deutschordensstaat) and its later German successor state of the

Duchy of Prussia

The Duchy of Prussia (german: Herzogtum Preußen, pl, Księstwo Pruskie, lt, Prūsijos kunigaikštystė) or Ducal Prussia (german: Herzogliches Preußen, link=no; pl, Prusy Książęce, link=no) was a duchy in the region of Prussia establish ...

was never part of the Holy Roman Empire.

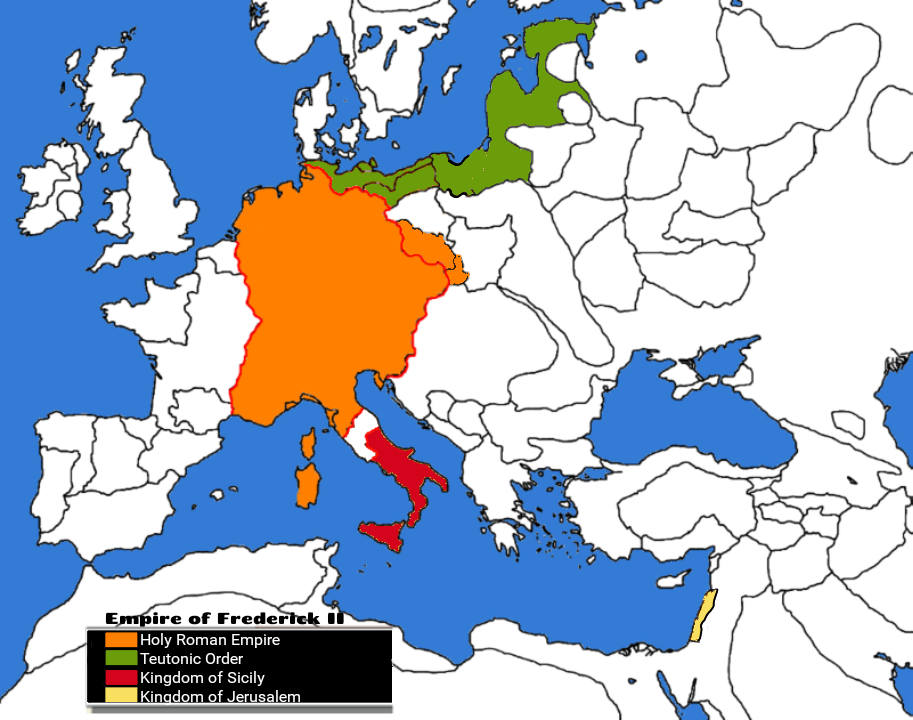

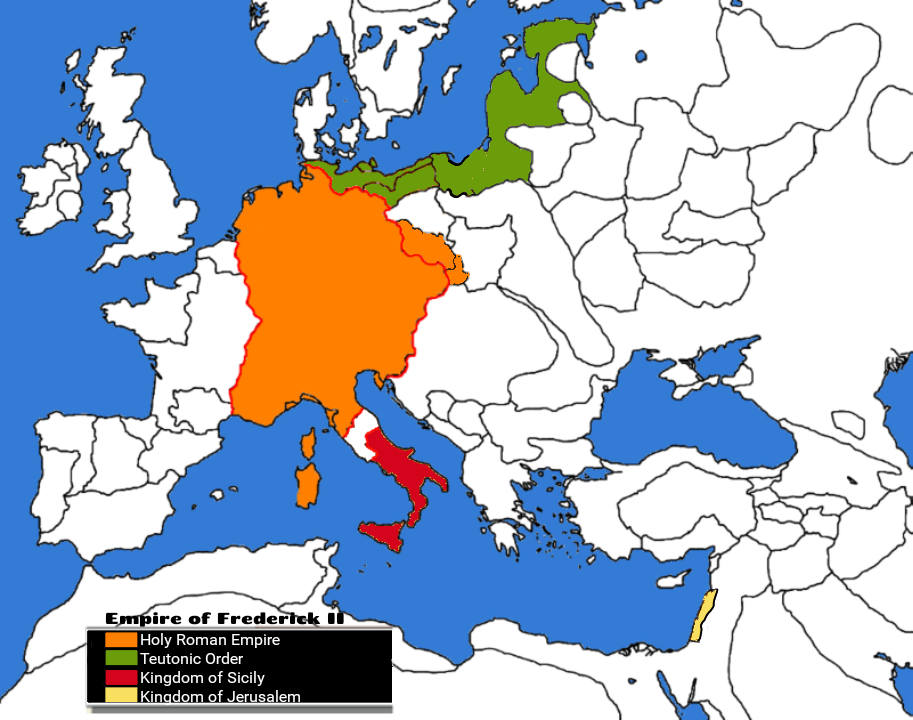

Under the son and successor of Frederick Barbarossa,

Henry VI, the Hohenstaufen dynasty reached its apex, with the addition of the Norman kingdom of Sicily through the marriage of Henry VI and

Constance of Sicily. Bohemia and Poland were under feudal dependence, while Cyprus and Lesser Armenia also paid homage. The Iberian-Moroccan caliph accepted his claims over the suzerainty over Tunis and Tripolitania and paid tribute. Fearing the power of Henry, the most powerful monarch in Europe since Charlemagne, the other European kings formed an alliance. But Henry broke this coalition by blackmailing English king

Richard the Lionheart

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199) was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Aquitaine and Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, and Count of Poitiers, Anjou, Maine, and Nantes, and was overl ...

. The Byzantine emperor worried that Henry would turned his Crusade plan against his empire, and began to collect the ''alamanikon'' to prepare against the expected invasion. Henry also had plans for turning the Empire into a hereditary monarchy, although this met with opposition from some of the princes and the Pope. The emperor suddenly died in 1197, leading to the partial collapse of his empire. As his son,

Frederick II, though already elected king, was still a small child and living in Sicily, German princes chose to elect an adult king, resulting in the dual election of Frederick Barbarossa's youngest son

Philip of Swabia and Henry the Lion's son

Otto of Brunswick, who competed for the crown. After Philip was murdered in a private squabble in 1208, Otto prevailed for a while, until he began to also claim Sicily.

Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III ( la, Innocentius III; 1160 or 1161 – 16 July 1216), born Lotario dei Conti di Segni (anglicized as Lothar of Segni), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 to his death in 16 ...

, who feared the threat posed by a union of the empire and Sicily, was now supported by Frederick II, who marched to Germany and defeated Otto. After his victory, Frederick did not act upon his promise to keep the two realms separate. Though he had made his son Henry king of Sicily before marching on Germany, he still reserved real political power for himself. This continued after Frederick was crowned Emperor in 1220. Fearing Frederick's concentration of power, the Pope finally excommunicated him. Another point of contention was the Crusade, which Frederick had promised but repeatedly postponed. Now, although excommunicated, Frederick led the

Sixth Crusade in 1228, which ended in negotiations and a temporary restoration of the

Kingdom of Jerusalem

The Kingdom of Jerusalem ( la, Regnum Hierosolymitanum; fro, Roiaume de Jherusalem), officially known as the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem or the Frankish Kingdom of Palestine,Example (title of works): was a Crusader state that was establish ...

.

Despite his imperial claims, Frederick's rule was a major turning point towards the disintegration of central rule in the Empire. While concentrated on establishing a modern, centralized state in Sicily, he was mostly absent from Germany and issued far-reaching privileges to Germany's secular and ecclesiastical princes: in the 1220 ''

Confoederatio cum principibus ecclesiasticis

The ''Confoederatio cum principibus ecclesiasticis'' ("Treaty with the princes of the church") was decreed on 26 April 1220 by Frederick II as a concession to the German bishops in return for their co-operation in the election of his son Henry ...

,'' Frederick gave up a number of ''regalia'' in favour of the bishops, among them tariffs,

coining, and fortification. The 1232 ''

Statutum in favorem principum'' mostly extended these privileges to secular territories. Although many of these privileges had existed earlier, they were now granted globally, and once and for all, to allow the German princes to maintain order north of the Alps while Frederick concentrated on Italy. The 1232 document marked the first time that the German dukes were called ''domini terræ,'' owners of their lands, a remarkable change in terminology as well.

Kingdom of Bohemia

The

Kingdom of Bohemia

The Kingdom of Bohemia ( cs, České království),; la, link=no, Regnum Bohemiae sometimes in English literature referred to as the Czech Kingdom, was a medieval and early modern monarchy in Central Europe, the predecessor of the modern Czec ...

was a significant regional power during the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

. In 1212, King

Ottokar I (bearing the title "king" since 1198) extracted a

Golden Bull of Sicily

The Golden Bull of Sicily ( cs, Zlatá bula sicilská; la, Bulla Aurea Siciliæ) was a decree issued by Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor in Basel on 26 September 1212 that confirmed the royal title obtained by Ottokar I of Bohemia in 1198, decl ...

(a formal edict) from the emperor

Frederick II, confirming the royal title for Ottokar and his descendants, and the Duchy of Bohemia was raised to a kingdom. Bohemia's political and financial obligations to the Empire were gradually reduced.

Charles IV set

Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and List of cities in the Czech Republic, largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 milli ...

to be the seat of the Holy Roman Emperor.

Interregnum

After the death of Frederick II in 1250, the German kingdom was divided between his son

Conrad IV

Conrad (25 April 1228 – 21 May 1254), a member of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, was the only son of Emperor Frederick II from his second marriage with Queen Isabella II of Jerusalem. He inherited the title of King of Jerusalem (as Conrad II) up ...

(died 1254) and the

anti-king

An anti-king, anti king or antiking (german: Gegenkönig; french: antiroi; cs, protikrál) is a would-be king who, due to succession disputes or simple political opposition, declares himself king in opposition to a reigning monarch. OED "Anti-, ...

,

William of Holland (died 1256). Conrad's death was followed by the

Interregnum, during which no king could achieve universal recognition, allowing the princes to consolidate their holdings and become even more independent as rulers. After 1257, the crown was contested between

Richard of Cornwall

Richard (5 January 1209 – 2 April 1272) was an English prince who was King of the Romans from 1257 until his death in 1272. He was the second son of John, King of England, and Isabella, Countess of Angoulême. Richard was nominal Count of P ...

, who was supported by the

Guelph party

The Guelphs and Ghibellines (, , ; it, guelfi e ghibellini ) were factions supporting the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, respectively, in the Italian city-states of Central Italy and Northern Italy.

During the 12th and 13th centuries, ri ...

, and

Alfonso X of Castile

Alfonso X (also known as the Wise, es, el Sabio; 23 November 1221 – 4 April 1284) was King of Castile, León and Galicia from 30 May 1252 until his death in 1284. During the election of 1257, a dissident faction chose him to be king of Ger ...

, who was recognized by the Hohenstaufen party but never set foot on German soil. After Richard's death in 1273,

Rudolf I of Germany

Rudolf I (1 May 1218 – 15 July 1291) was the first King of Germany from the House of Habsburg. The first of the count-kings of Germany, he reigned from 1273 until his death.

Rudolf's election marked the end of the Great Interregnum whic ...

, a minor pro-Hohenstaufen count, was elected. He was the first of the

Habsburgs to hold a royal title, but he was never crowned emperor. After Rudolf's death in 1291,

Adolf

Adolf (also spelt Adolph or Adolphe, Adolfo and when Latinised Adolphus) is a given name used in German-speaking countries, Scandinavia, the Netherlands and Flanders, France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Latin America and to a lesser extent in vari ...

and

Albert

Albert may refer to:

Companies

* Albert (supermarket), a supermarket chain in the Czech Republic

* Albert Heijn, a supermarket chain in the Netherlands

* Albert Market, a street market in The Gambia

* Albert Productions, a record label

* Alber ...

were two further weak kings who were never crowned emperor.

Albert was assassinated in 1308. Almost immediately, King

Philip IV of France began aggressively seeking support for his brother,

Charles of Valois

Charles of Valois (12 March 1270 – 16 December 1325), the fourth son of King Philip III of France and Isabella of Aragon, was a member of the House of Capet and founder of the House of Valois, whose rule over France would start in 1 ...

, to be elected the next

King of the Romans. Philip thought he had the backing of the French Pope,

Clement V

Pope Clement V ( la, Clemens Quintus; c. 1264 – 20 April 1314), born Raymond Bertrand de Got (also occasionally spelled ''de Guoth'' and ''de Goth''), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 5 June 1305 to his de ...

(established at Avignon in 1309), and that his prospects of bringing the empire into the orbit of the French royal house were good. He lavishly spread French money in the hope of bribing the German electors. Although Charles of Valois had the backing of pro-French

Henry, Archbishop of Cologne, many were not keen to see an expansion of French power, least of all Clement V. The principal rival to Charles appeared to be

Rudolf, the Count Palatine.

But the electors, the great territorial magnates who had lived without a crowned emperor for decades, were unhappy with both Charles and Rudolf. Instead

Henry, Count of Luxembourg, with the aid of his brother,

Baldwin, Archbishop of Trier

Baldwin of Luxembourg (c. 1285 – 21 January 1354) was the Archbishop- Elector of Trier and Archchancellor of Burgundy from 1307 to his death. From 1328 to 1336, he was the diocesan administrator of the archdiocese of Mainz and from 1331 to 1 ...

, was elected as Henry VII with six votes at Frankfurt on 27 November 1308. Though a vassal of king Philip, Henry was bound by few national ties, and thus suitable as a compromise candidate. Henry VII was crowned king at Aachen on 6 January 1309, and emperor by Pope Clement V on 29 June 1312 in Rome, ending the interregnum.

Changes in political structure

During the 13th century, a general structural change in how land was administered prepared the shift of political power towards the rising

bourgeoisie at the expense of the aristocratic

feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

that would characterize the

Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Renai ...

. The rise of the

cities

A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be def ...

and the emergence of the new

burgher

Burgher may refer to:

* Burgher (social class), a medieval, early modern European title of a citizen of a town, and a social class from which city officials could be drawn

** Burgess (title), a resident of a burgh in northern Britain

** Grand Bu ...

class eroded the societal, legal and economic order of feudalism. Instead of personal duties, money increasingly became the common means to represent economic value in agriculture.

Peasants were increasingly required to pay tribute to their landlords. The concept of "property" began to replace more ancient forms of jurisdiction, although they were still very much tied together. In the territories (not at the level of the Empire), power became increasingly bundled: whoever owned the land had jurisdiction, from which other powers derived. However, that jurisdiction at the time did not include legislation, which was virtually non-existent until well into the 15th century. Court practice heavily relied on traditional customs or rules described as customary.

During this time, territories began to transform into the predecessors of modern states. The process varied greatly among the various lands and was most advanced in those territories that were almost identical to the lands of the old Germanic tribes, ''e.g.'', Bavaria. It was slower in those scattered territories that were founded through imperial privileges.

In the 12th century the

Hanseatic League established itself as a commercial and defensive alliance of the merchant

guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometimes ...

s of towns and cities in the empire and all over northern and central Europe. It dominated marine trade in the

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and ...

, the

North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea, epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the ...

and along the connected navigable rivers. Each of the affiliated cities retained the legal system of its sovereign and, with the exception of the

Free imperial cities

In the Holy Roman Empire, the collective term free and imperial cities (german: Freie und Reichsstädte), briefly worded free imperial city (', la, urbs imperialis libera), was used from the fifteenth century to denote a self-ruling city that ...

, had only a limited degree of political autonomy. By the late 14th century, the powerful league enforced its interests with military means, if necessary. This culminated in

a war

''A War'' () is a 2015 Danish war drama film written and directed by Tobias Lindholm, and starring Pilou Asbæk and Søren Malling. It tells the story of a Danish military company in Afghanistan that is fighting the Taliban while trying to pro ...

with the sovereign Kingdom of Denmark from 1361 to 1370. The league declined after 1450.

Late Middle Ages

Rise of the territories after the Hohenstaufens

The difficulties in electing the king eventually led to the emergence of a fixed college of

prince-elector

The prince-electors (german: Kurfürst pl. , cz, Kurfiřt, la, Princeps Elector), or electors for short, were the members of the electoral college that elected the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

From the 13th century onwards, the prin ...

s (''Kurfürsten''), whose composition and procedures were set forth in the

Golden Bull of 1356

The Golden Bull of 1356 (, , , , ) was a decree issued by the Imperial Diet at Nuremberg and Metz ( Diet of Metz, 1356/57) headed by the Emperor Charles IV which fixed, for a period of more than four hundred years, important aspects of the con ...

, issued by

Charles IV (reigned 1355–1378, King of the Romans since 1346), which remained valid until 1806. This development probably best symbolizes the emerging duality between emperor and realm (''Kaiser und Reich''), which were no longer considered identical. The Golden Bull also set forth the system for election of the Holy Roman Emperor. The emperor now was to be elected by a majority rather than by consent of all seven electors. For electors the title became hereditary, and they were given the right to mint coins and to exercise jurisdiction. Also it was recommended that their sons learn the imperial languages –

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

,

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

,

Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

, and

Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus'

Places

* Czech, ...

. The decision by Charles IV is the subject of debates: on one hand, it helped to restore peace in the lands of the Empire, that had been engulfed in civil conflicts after the end of the Hohenstaufen era; on the other hand, the "blow to central authority was unmistakable". Thomas Brady Jr. opines that Charles IV's intention was to end contested royal elections (from the Luxembourghs' perspective, they also had the advantage that the King of Bohemia had a permanent and preeminent status as one of the Electors himself). At the same time, he built up Bohemia as the Luxembourghs' core land of the Empire and their dynastic base. His reign in Bohemia is often considered the land's Golden Age. According to Brady Jr. though, under all the glitter, one problem arose: the government showed an inability to deal with the German immigrant waves into Bohemia, thus leading to religious tensions and persecutions. The imperial project of the Luxembourgh halted under Charles's son

Wenceslaus

Wenceslaus, Wenceslas, Wenzeslaus and Wenzslaus (and other similar names) are Latinized forms of the Czech name Václav. The other language versions of the name are german: Wenzel, pl, Wacław, Więcesław, Wieńczysław, es, Wenceslao, russian ...