Г‰lisГ©e Reclus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

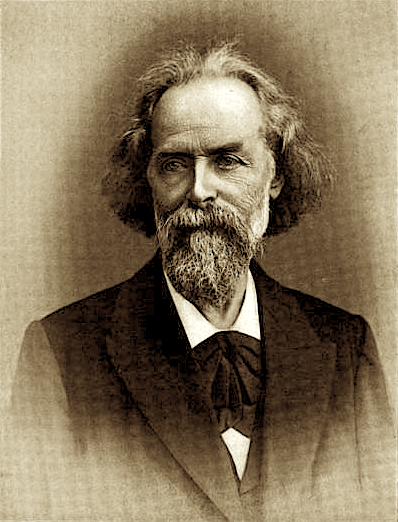

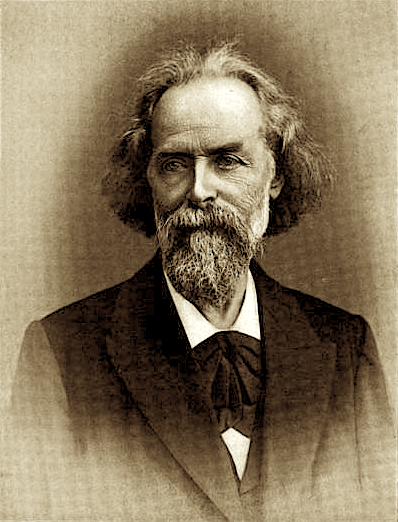

Jacques Г‰lisГ©e Reclus (; 15 March 18304 July 1905) was a French

During the

During the

"Are Anarchists Revolting?"

, ''

originally published in ''Joyce Studies,'' Annual 6 (1995): 99–138 In a 1913 piece, Kropotkin, in admiration of Reclus, said that if anyone asked about the conflicts of the Middle East, that "I should merely open the volume of Elisée Reclus's ''Geographie Universelle L'Asie, Russe''..." Reclus had strong views on In 1894, Reclus was appointed chair of comparative geography at the

In 1894, Reclus was appointed chair of comparative geography at the

''L'Homme et la terre''

(1905), e-text online, Internet Archive * *

v.5

Russia in Europe, etc.

Index

*

v.6

Asiatic Russia

Index

* * ** Europe

v.1v.2v.3v.4v.5

** North America

v.1v.2v.3

** Africa

v.1v.2v.3v.4

''The earth and its inhabitants. The universal geography,'' ed. by E.G. Ravenstein (A.H. Keane). (J.S. Virtue, 1878)

''The earth and its inhabitants, Asia, Volume 1'' (D. Appleton and Company, 1891)

''The Earth and Its Inhabitants ...: Asiatic Russia: Caucasia, Aralo-Caspian basin, Siberia'' (D. Appleton and Company, 1891)

''The Earth and Its Inhabitants ...: South-western Asia'' (D. Appleton and Company, 1891)

''On Vegetarianism''

(''Humane Review'', 1901)

Г‰lisГ©e Reclus

Research on Anarchism * * *

Reed College * ttp://antwerpjamesjoycecenter.com/fleuve.html Ingeborg Landuyt and Geert Lernout, "Joyce's Sources: Les Grands Fleuves Historiques" originally published in ''Joyce Studies,'' Annual 6 (1995): 99-138.

Г‰lisГ©e Reclus, "An Anarchist on Anarchy"

(1884) * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Reclus, Elisee 1830 births 1905 deaths 19th-century geographers 19th-century Protestants Anarcho-communists Christian anarchists Christian communists Communards Free love advocates French anarchists French animal rights activists French anti-capitalists French communists French geographers French male writers French naturists French non-fiction writers French Protestants French socialists French vegetarianism activists Green anarchists Human geographers Male non-fiction writers Members of the SociГ©tГ© Ramond People from Gironde Elisee

geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society, including how society and nature interacts. The Greek prefix "geo" means "earth" a ...

, writer and anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

. He produced his 19-volume masterwork, ''La Nouvelle Géographie universelle, la terre et les hommes'' ("Universal Geography"), over a period of nearly 20 years (1875–1894). In 1892 he was awarded the Gold Medal of the Paris Geographical Society

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 kmВІ (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

for this work, despite having been banished from France because of his political activism.

Biography

Reclus was born atSainte-Foy-la-Grande

Sainte-Foy-la-Grande (; oc, Senta Fe la Granda) is a Communes of France, commune in the Gironde Departments of France, department in Nouvelle-Aquitaine in southwestern France. It is on the south bank of the Dordogne (river), Dordogne.

History

Th ...

(Gironde

Gironde ( US usually, , ; oc, Gironda, ) is the largest department in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region of Southwestern France. Named after the Gironde estuary, a major waterway, its prefecture is Bordeaux. In 2019, it had a population of 1,62 ...

). He was the second son of a Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

pastor and his wife. From the family of fourteen children, several brothers, including fellow geographers OnГ©sime and Г‰lie Reclus

Élie Reclus (; 1827–1904) was a French ethnographer and anarchist.

Г‰lie Reclus was the oldest of five brothers, born to a Protestant minister and his wife. His middle three brothers, including the well known anarchist Г‰lisГ©e Reclus, all b ...

, went on to achieve renown either as men of letters, politicians or members of the learned professions.

Reclus began his education in Rhenish Prussia

The Rhine Province (german: Rheinprovinz), also known as Rhenish Prussia () or synonymous with the Rhineland (), was the westernmost province of the Kingdom of Prussia and the Free State of Prussia, within the German Reich, from 1822 to 1946. It ...

, and continued higher studies at the Protestant college of Montauban

Montauban (, ; oc, Montalban ) is a commune in the Tarn-et-Garonne department, region of Occitania, Southern France. It is the capital of the department and lies north of Toulouse. Montauban is the most populated town in Tarn-et-Garonne, an ...

. He completed his studies at the University of Berlin

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative o ...

, where he followed a long course of geography under Carl Ritter

Carl Ritter (August 7, 1779September 28, 1859) was a German geographer. Along with Alexander von Humboldt, he is considered one of the founders of modern geography. From 1825 until his death, he occupied the first chair in geography at the Univer ...

.

Withdrawing from France due to the political events of December 1851, as a young man he spent the next six years (1852–1857) traveling and working in Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

, the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, Central America

Central America ( es, AmГ©rica Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

, and Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Car ...

. Arriving in Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

in 1853, Reclus worked for about two and a half years as a tutor to the children of cousin Septime and FГ©licitГ© Fortier at their plantation FГ©licitГ©, located about upriver from New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-OrlГ©ans , es, Nuev ...

. He recounted his passage through the Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-OrlГ©ans , es, Nuev ...

Mississippi River Delta

The Mississippi River Delta is the confluence of the Mississippi River with the Gulf of Mexico in Louisiana, southeastern United States. The river delta is a area of land that stretches from Vermilion Bay on the west, to the Chandeleur Isla ...

and impressions of antebellum New Orleans and the state in ''Fragment d'un voyage Г la Nouvelle-OrlГ©ans'', published in 1855.

On his return to Paris, Reclus contributed to the ''Revue des deux mondes

The ''Revue des deux Mondes'' (, ''Review of the Two Worlds'') is a monthly French-language literary, cultural and current affairs magazine that has been published in Paris since 1829.

According to its website, "it is today the place for debates a ...

'', the ''Tour du monde'' and other periodicals, a large number of articles embodying the results of his geographical work. Among other works of this period was the short book ''Histoire d'un ruisseau'', in which he traced the development of a great river from source to mouth. During 1867 and 1868, he published ''La Terre; description des phГ©nomГЁnes de la vie du globe'' in two volumes.

Siege of Paris (1870–1871)

The siege of Paris took place from 19 September 1870 to 28 January 1871 and ended in the capture of the city by forces of the various states of the North German Confederation, led by the Kingdom of Prussia. The siege was the culmination of the ...

, Reclus shared in the aerostat

An aerostat (, via French) is a lighter-than-air aircraft that gains its lift through the use of a buoyant gas. Aerostats include unpowered balloons and powered airships. A balloon may be free-flying or tethered. The average density of the cra ...

ic operations conducted by FГ©lix Nadar

Gaspard-Félix Tournachon (5 April 1820 – 20 March 1910), known by the pseudonym Nadar, was a French photographer, caricaturist, journalist, novelist, balloonist, and proponent of heavier-than-air flight. In 1858, he became the first person t ...

, and also served in the National Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

Nat ...

. As a member of the Association Nationale des Travailleurs, he published a hostile manifesto against the government of Versailles in support of the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defended ...

of 1871 in the ''Cri du Peuple

CRI or CRi may refer to:

Organizations

* Canadian Rivers Institute, for river sciences, University of New Brunswick

* Cancer Research Institute, New York, US

* Centro de Relaciones Internacionales (International Relations Center), Universidad Nac ...

''.

Continuing to serve in the National Guard, which was then in open revolt, Reclus was taken prisoner on 5 April into Fort QuГ©lern

The fort QuГ©lern or rГ©duit de QuГ©lern is a castle and prison in the commune of Roscanvel in France.

Construction

This fort was built between 1852 and 1854 on modified plans by Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban (1633–1707).

It is an enclosure ...

. On 16 November he was sentenced to deportation for life. Because of intervention by supporters from England, the sentence was commuted in January 1872 to perpetual banishment from France.

After a short visit to Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, Reclus settled at Clarens, Switzerland

Clarens-Montreux or Clarens is a neighborhood in the municipality of Montreux, in the canton of Vaud, in Switzerland. This neighborhood is the biggest and most populated of the city of Montreux.

Clarens was made famous throughout Europe by the i ...

, where he resumed his literary labours and produced ''Histoire d'une montagne'', a companion to ''Histoire d'un ruisseau''. There he wrote nearly the whole of his work, ''La Nouvelle Géographie universelle, la terre et les hommes'', "an examination of every continent and country in terms of the effects that geographic features like rivers and mountains had on human populations—and vice versa." Sale, Kirkpatrick (1 July 2010"Are Anarchists Revolting?"

, ''

The American Conservative

''The American Conservative'' (''TAC'') is a magazine published by the American Ideas Institute which was founded in 2002. Originally published twice a month, it was reduced to monthly publication in August 2009, and since February 2013, it has ...

'', 1 July 2010 This compilation was profusely illustrated with maps, plans, and engravings. It was awarded the gold medal of the Paris Geographical Society

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 kmВІ (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

in 1892. An English edition was published simultaneously, also in 19 volumes, the first four translated by E. G. Ravenstein, the rest by A. H. Keane

Augustus Henry Keane (1833–1912) was an Irish Roman Catholic journalist and linguist, known for his ethnological writings.

Early life

He was born in Cork (city), Cork, Ireland.George Grant MacCurdy, James Mooney and A. B. LegГa - Antonio Flor ...

. Reclus's writings were characterized by extreme accuracy and brilliant exposition, which gave them permanent literary and scientific value.

According to Kirkpatrick Sale

Kirkpatrick Sale (born June 27, 1937) is an American author who has written prolifically about political decentralism, environmentalism, luddism and technology. He has been described as having a "philosophy unified by decentralism" and as being " ...

:

In 1882, Reclus initiated the Anti-Marriage Movement. In accordance with these beliefs and the practice of ''union libre'' ("free unions"), which was common among working-class French in the mid-to-late 1800s, Reclus allowed his two daughters to "marry" their male partners without any civil or religious ceremonies, an action causing embarrassment to many of his well-wishers. Reclus had himself entered a free union in 1872, after the death of his first wife. In 1882 he also wrote ''Unions Libres'', a pamphlet which detailed his anarchist and feminist objections to marriage. The French government initiated prosecution from the High Court of Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''LionГ©s'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers RhГґne and SaГґne, to the northwest of t ...

, arrested him and Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (; russian: link=no, Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин ; 9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist, socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist, philosopher, and activis ...

as the International Association's organizers, and sentenced the latter to five years' imprisonment. Reclus escaped punishment as he remained in Switzerland.Ingeborg Landuyt and Geert Lernout, "Joyce's Sources: Les Grands Fleuves Historiques"originally published in ''Joyce Studies,'' Annual 6 (1995): 99–138 In a 1913 piece, Kropotkin, in admiration of Reclus, said that if anyone asked about the conflicts of the Middle East, that "I should merely open the volume of Elisée Reclus's ''Geographie Universelle L'Asie, Russe''..." Reclus had strong views on

naturism

Naturism is a lifestyle of practising non-sexual social nudity in private and in public; the word also refers to the cultural movement which advocates and defends that lifestyle. Both may alternatively be called nudism. Though the two terms ar ...

and the benefits of nudity

Nudity is the state of being in which a human is without clothing.

The loss of body hair was one of the physical characteristics that marked the biological evolution of modern humans from their hominin ancestors. Adaptations related to ...

. He argued that living naked was more hygienic than wearing clothes; he believed that it was healthier for skin to be fully exposed to light and air so that it could resume its "natural vitality and activity" and become more flexible and firm at the same time. He also argued that from an aesthetic point of view, nudity was better: naked people were more beautiful. His principal objection to clothing was, however, a moral one; he felt that a fixation with clothing caused excessive focus on what was covered.

In 1894, Reclus was appointed chair of comparative geography at the

In 1894, Reclus was appointed chair of comparative geography at the Free University of Brussels University of Brussels may refer to several institutions in Brussels, Belgium: Current institutions

* UniversitГ© libre de Bruxelles (ULB), a French-speaking university established as a separate entity in 1970

*Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), a D ...

, and moved with his family to Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

. His brother Г‰lie Reclus

Élie Reclus (; 1827–1904) was a French ethnographer and anarchist.

Г‰lie Reclus was the oldest of five brothers, born to a Protestant minister and his wife. His middle three brothers, including the well known anarchist Г‰lisГ©e Reclus, all b ...

was at the university already, teaching religion. Г‰lisГ©e Reclus continued to write, contributing several important articles and essays to French, German and English scientific journals. He was awarded the 1894 Patron's Medal

The Royal Geographical Society's Gold Medal consists of two separate awards: the Founder's Medal 1830 and the Patron's Medal 1838. Together they form the most prestigious of the society's awards. They are given for "the encouragement and promoti ...

of the Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

.

In 1905, shortly before his death, Reclus completed ''L'Homme et la terre'', in which he rounded out his previous works by considering humanity's development relative to its geographical environment.

Personal life

On 11 March 1858, he was initiated in the regularScottish Rite

The Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry (the Northern Masonic Jurisdiction in the United States often omits the ''and'', while the English Constitution in the United Kingdom omits the ''Scottish''), commonly known as simply the Sco ...

Masonic Lodge

A Masonic lodge, often termed a private lodge or constituent lodge, is the basic organisational unit of Freemasonry. It is also commonly used as a term for a building in which such a unit meets. Every new lodge must be warranted or chartered ...

''Les Г‰mules d'Hiram'', affiliated to the Grand Orient of France. His brother was just initiated and took part in his masonic baptism. He remained at the initiatel degrees of the Masonic spiritual path.

Reclus married and had a family, including two daughters.

He died at Torhout

Torhout (; french: Thourout; vls, Toeroet) is a city and municipality located in the Belgian province of West Flanders. The municipality comprises the city of Torhout proper, the villages of Wijnendale and Sint-Henricus, and the hamlet of De Dri ...

, near Bruges

Bruges ( , nl, Brugge ) is the capital and largest City status in Belgium, city of the Provinces of Belgium, province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium, in the northwest of the country, and the sixth-largest city of the countr ...

, Belgium.

Legacy

Reclus was admired by many prominent 19th century thinkers, includingAlfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was a British naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He is best known for independently conceiving the theory of evolution through natural se ...

, George Perkins Marsh

George Perkins Marsh (March 15, 1801July 23, 1882), an American diplomat and philologist, is considered by some to be America's first environmentalist and by recognizing the irreversible impact of man's actions on the earth, a precursor to the ...

, Patrick Geddes

Sir Patrick Geddes (2 October 1854 – 17 April 1932) was a British biologist, sociologist, Comtean positivist, geographer, philanthropist and pioneering town planner. He is known for his innovative thinking in the fields of urban planning ...

, Henry Stephens Salt

Henry Shakespear Stephens Salt (; 20 September 1851 – 19 April 1939) was an English writer and campaigner for social reform in the fields of prisons, schools, economic institutions, and the treatment of animals. He was a noted ethical vegeta ...

, and Octave Mirbeau

Octave Mirbeau (16 February 1848 – 16 February 1917) was a French novelist, art critic, travel writer, pamphleteer, journalist and playwright, who achieved celebrity in Europe and great success among the public, whilst still appealing to the ...

. James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important writers of ...

was influenced by LГ©on Metchnikoff's book ''La civilisation et les grands fleuves historiques'', to which Reclus contributed a foreword.

Reclus advocated nature conservation

Nature conservation is the moral philosophy and conservation movement focused on protecting species from extinction, maintaining and restoring habitats, enhancing ecosystem services, and protecting biological diversity. A range of values unde ...

and opposed meat-eating and cruelty to animals. He was a vegetarian

Vegetarianism is the practice of abstaining from the consumption of meat (red meat, poultry, seafood, insects, and the flesh of any other animal). It may also include abstaining from eating all by-products of animal slaughter.

Vegetarianism m ...

. As a result, his ideas are seen by some historians and writers as anticipating the modern social ecology Social ecology may refer to:

* Social ecology (academic field), the study of relationships between people and their environment, often the interdependence of people, collectives and institutions

* Social ecology (Bookchin), a theory about the relat ...

and animal rights

Animal rights is the philosophy according to which many or all sentient animals have moral worth that is independent of their utility for humans, and that their most basic interests—such as avoiding suffering—should be afforded the sa ...

movements.

Selected works

Books

''L'Homme et la terre'' (''The Earth and Its Inhabitants"), 6 volumes:''L'Homme et la terre''

(1905), e-text online, Internet Archive * *

v.5

Russia in Europe, etc.

Index

*

v.6

Asiatic Russia

Index

* * ** Europe

v.1

** North America

v.1

** Africa

v.1

''The earth and its inhabitants. The universal geography,'' ed. by E.G. Ravenstein (A.H. Keane). (J.S. Virtue, 1878)

''The earth and its inhabitants, Asia, Volume 1'' (D. Appleton and Company, 1891)

''The Earth and Its Inhabitants ...: Asiatic Russia: Caucasia, Aralo-Caspian basin, Siberia'' (D. Appleton and Company, 1891)

''The Earth and Its Inhabitants ...: South-western Asia'' (D. Appleton and Company, 1891)

Anthology

* ''Du sentiment de la nature dans les sociétés modernes'' et autres textes, Éditions Premières Pierres, 2002 –Articles

* ''The Progress of Mankind'' (''Contemporary Review'', 1896) * ''Attila de Gerando'' (''Revue GГ©ographie'', 1898) * ''A Great Globe'' (''Geograph. Journal'', 1898) * ''L'ExtrГЄme-Orient'' (''Bulletin de la SociГ©tГ© royale de gГ©ographie d'Anvers,'' 1898), a study of the political geography of the Far East and its possible changes * a report made for Parisian newspapers about theParaguayan War

The Paraguayan War, also known as the War of the Triple Alliance, was a South American war that lasted from 1864 to 1870. It was fought between Paraguay and the Triple Alliance of Argentina, the Empire of Brazil, and Uruguay. It was the deadlies ...

, sympathetic towards the Paraguayan side.

* ''La Perse'' (''Bulletin de la SociГ©tГ© neuchГўteloise'', 1899)

* ''La PhГ©nicie et les PhГ©niciens'' (ibid., 1900)

* ''La Chine et la diplomatie europГ©enne'' (''L'HumanitГ© nouvelle'' series, 1900)

* ''L'Enseignement de la gГ©ographie'' (''Institut de gГ©ographie de Bruxelles'', No 5, 1901)

''On Vegetarianism''

(''Humane Review'', 1901)

See also

*Anarchism in France

Anarchism in France can trace its roots to thinker Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who grew up during the Restoration and was the first self-described anarchist. French anarchists fought in the Spanish Civil War as volunteers in the International Brig ...

* Green anarchism

Green anarchism (or eco-anarchism"green anarchism (also called eco-anarchism)" in ''An Anarchist FAQ'' by various authors.) is an anarchist school of thought that puts a particular emphasis on ecology and environmental issues. A green anarchist ...

References

*Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ''Kropotkin P. A.'' Obituary. ElisГ©e Reclus // Geographical Journal. 1905. Vol. 26, No. 3, Sept. P. 337-343; Obituary. ElisГ©e Reclus. London, 1905. 8 p. * * * Philippe Pelletier, ElisГ©e Reclus, gГ©ographie et anarchie, Paris, Editions du monde Libertaire, 2009. * * *External links

Г‰lisГ©e Reclus

Research on Anarchism * * *

Reed College * ttp://antwerpjamesjoycecenter.com/fleuve.html Ingeborg Landuyt and Geert Lernout, "Joyce's Sources: Les Grands Fleuves Historiques" originally published in ''Joyce Studies,'' Annual 6 (1995): 99-138.

Г‰lisГ©e Reclus, "An Anarchist on Anarchy"

(1884) * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Reclus, Elisee 1830 births 1905 deaths 19th-century geographers 19th-century Protestants Anarcho-communists Christian anarchists Christian communists Communards Free love advocates French anarchists French animal rights activists French anti-capitalists French communists French geographers French male writers French naturists French non-fiction writers French Protestants French socialists French vegetarianism activists Green anarchists Human geographers Male non-fiction writers Members of the SociГ©tГ© Ramond People from Gironde Elisee