threshing board on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A threshing board, also known as threshing sledge, is an obsolete agricultural implement used to separate

A threshing board, also known as threshing sledge, is an obsolete agricultural implement used to separate

Until the arrival of

Until the arrival of

Patricia C. Anderson (of ''Centre d’Etudes Préhistoire, Antiquité et Moyen Age del

Patricia C. Anderson (of ''Centre d’Etudes Préhistoire, Antiquité et Moyen Age del  There are another representation, in this case without writing, in central Turkey. It is an impression of a

There are another representation, in this case without writing, in central Turkey. It is an impression of a

Two apparently coincident descriptive narratives are given in and with regard to King David's purchase of the threshing floor on Mount

Two apparently coincident descriptive narratives are given in and with regard to King David's purchase of the threshing floor on Mount  The selected place, Mount Moriah, was owned by Araunah (or, ''Ornan'') the Jebusite, a rich villager who owned and operated the threshing floor on Mount Moriah. Araunah was awed by the visit of the king and offered his oxen to

The selected place, Mount Moriah, was owned by Araunah (or, ''Ornan'') the Jebusite, a rich villager who owned and operated the threshing floor on Mount Moriah. Araunah was awed by the visit of the king and offered his oxen to

In

In

ImageSize = width:730 height:100

PlotArea = width:700 height:50 left:20 bottom:30

TimeAxis = orientation:horizontal

DateFormat = yyyy

Period = from:-6000 till:2000

AlignBars = early

ScaleMajor = unit:year increment:1000 start:-6000

Colors =

id:canvas value:rgb(1,1,0.85)

BackgroundColors = canvas:canvas

PlotData=

bar:a width:15 color:teal

from:-5800 till:-5200

from:-4800 till:-4200

from:-3450 till:-3370

from:-3348 till:-3300

from:-2600 till:-2500

from:-1420 till:-1208

from:-1005 till:-965

from:-740 till:-698

from:-234 till:-149

from:-116 till:-27

from:10 till:79

from:1230 till:1280

from:1500 till:1950

bar:d width:15 color:canvas

from:-5800 till:-5200 align:center fontsize:S text:First discoveries

from:-5000 till:-4000 align:center fontsize:S text:Aratashen

at:-3400 align:right fontsize:S text:

*

File:Trillo-6 tronco de pino.png, The pine , from which the slats were cut

File:Trillo-7 listones en linea.png, Slats aligned, before forming the threshing board

File:Briquero escopleando.png, Chiseling the slat

Once the slat was in the right conditions, the next process was chiseling: using a

File:Trillo-8 cabezales.png, The planks glued, as they are in the ''cárceles''

File:Trillo-9 clavar cabezales.png, Placing the "headers" (''cabezales'') with large iron nails

File:Trillo-10 clavar juntas.png, Placing of stopgaps in the junctions.

File:Trillo-11 vista general.png, The wooden structure completed, but with the cutting stones not yet added

Once the basic structure of the threshing board is ready, it must be smoothed. This is first done by "working" it with an adze lengthwise, along the grain. Then the final finishing is done with various specialized carpenter's planes, on both top and bottom; first going across in a transverse direction, and later lengthwish.

The final phase of the work consisted of covering the junctions of the slats on the top side, which is done with thin strips at the front, tacked on with a board called the "front piece", and on the rest using long thin little boards (''tapajuntas'' or stopgaps). On the front header they attached a strong hook for the ''barzón'', or iron ring with a strap or a long rod for tying on the drafthorses or oxen.

Once the basic structure of the threshing board is ready, it must be smoothed. This is first done by "working" it with an adze lengthwise, along the grain. Then the final finishing is done with various specialized carpenter's planes, on both top and bottom; first going across in a transverse direction, and later lengthwish.

The final phase of the work consisted of covering the junctions of the slats on the top side, which is done with thin strips at the front, tacked on with a board called the "front piece", and on the rest using long thin little boards (''tapajuntas'' or stopgaps). On the front header they attached a strong hook for the ''barzón'', or iron ring with a strap or a long rod for tying on the drafthorses or oxen.

To create the lithic flakes used to cover threshing boards, the ''briqueros'' in Cantalejo used a manufacturing technique similar to prehistoric methods of making tools, except that they used metal hammers rather than percussors made of stone, wood, or antler.

The raw materials preferred by these artisans was a whitish flint imported from the province of

To create the lithic flakes used to cover threshing boards, the ''briqueros'' in Cantalejo used a manufacturing technique similar to prehistoric methods of making tools, except that they used metal hammers rather than percussors made of stone, wood, or antler.

The raw materials preferred by these artisans was a whitish flint imported from the province of  Knapping: Once manageable chunks of flint were obtained, knapping to obtain lithic flakes was performed using a very light hammer (called a ''pickaxe'') with a narrow handle and a pointed head. Knapping was considered "men's work." To work quartzite pebbles, they used a hammer with a head that was rounded and slightly wider. During the process of removing stone flakes, they sometimes resorted to a normal hammer to crack the stone and achieve perussion plains inaccessible with the pickaxe alone.

The ''briquero'' held the stone core in the left hand, protected with a piece of leather and with the palm upward, and struck rapid blows using a pick held in the right hand. The stone flakes would fall into the palm of the right hand, on top of the leather protector, which allowed the worker to evaluate them during fractions of a second: if they were acceptable, the ''briquero'' allowed them to fall into a tin; if not, he threw them into a reject pile. This pile was also where the ''briquero'' threw used-up stone cores —that is, stone blocks incapable of producing more chips; pieces of stone broken by accident; cortical flint flakes, useless fragments, and debris.

Knapping: Once manageable chunks of flint were obtained, knapping to obtain lithic flakes was performed using a very light hammer (called a ''pickaxe'') with a narrow handle and a pointed head. Knapping was considered "men's work." To work quartzite pebbles, they used a hammer with a head that was rounded and slightly wider. During the process of removing stone flakes, they sometimes resorted to a normal hammer to crack the stone and achieve perussion plains inaccessible with the pickaxe alone.

The ''briquero'' held the stone core in the left hand, protected with a piece of leather and with the palm upward, and struck rapid blows using a pick held in the right hand. The stone flakes would fall into the palm of the right hand, on top of the leather protector, which allowed the worker to evaluate them during fractions of a second: if they were acceptable, the ''briquero'' allowed them to fall into a tin; if not, he threw them into a reject pile. This pile was also where the ''briquero'' threw used-up stone cores —that is, stone blocks incapable of producing more chips; pieces of stone broken by accident; cortical flint flakes, useless fragments, and debris.

The working of pebbles was similar to the working of flint, except that with pebbles only the outside layer was chipped off. Thus, the pebbles were essentially "peeled" and discarded (unlike flint stones, whose interiors were worked until they were used up); using only the cortical flakes.

Covering the board with stone flakes was mainly the work of women called ''enchifleras''. The task is monotonous and repetitive. Up to three thousand lithic flakes may be pounded into a large threshing board. In addition, it is necessary to sort the flakes: small ones in the front, medium-sized in the middle, and the largest on the sides and in the back. It is necessary to pound in each flake without damaging its sharp edge, although it was impossible to avoid leaving at least some small mark (a "spontaneous retouch" in technical terms). The tool used was a light hammer with a cylindrical head and flat or concave ends. The flakes are inserted into the cracks at their thickest part (technically, the percussion zone, that is, the proximal heel of the flake as it is struck off.)

The working of pebbles was similar to the working of flint, except that with pebbles only the outside layer was chipped off. Thus, the pebbles were essentially "peeled" and discarded (unlike flint stones, whose interiors were worked until they were used up); using only the cortical flakes.

Covering the board with stone flakes was mainly the work of women called ''enchifleras''. The task is monotonous and repetitive. Up to three thousand lithic flakes may be pounded into a large threshing board. In addition, it is necessary to sort the flakes: small ones in the front, medium-sized in the middle, and the largest on the sides and in the back. It is necessary to pound in each flake without damaging its sharp edge, although it was impossible to avoid leaving at least some small mark (a "spontaneous retouch" in technical terms). The tool used was a light hammer with a cylindrical head and flat or concave ends. The flakes are inserted into the cracks at their thickest part (technically, the percussion zone, that is, the proximal heel of the flake as it is struck off.)

Threshing boards from Cantalejo captured nearly all the sales in

Threshing boards from Cantalejo captured nearly all the sales in

Middle-Eastern threshing board

. As mentioned previously, not all threshing boards are equipped with stones: some have metal knife blades embedded along the full length of the threshing board, and others have smaller blades encrusted here and there. Threshing sledges with metal knives usually have a few small wheels (four to six, depending on the size) with eccentric axes. These wheels protect the blades. They also make the threshing board wobble, causing parts of the board to rise and fall at random in an oscillating motion that improves the effectiveness of the threshing. A second model, which the classic sources refer to as ''plostellum punicum'' (literally, the "Punic cart"), ought to be called "threshing cart". Although the Carthaginians, heirs of the Phoenicians, brought this model to the Western

A threshing floor in the hills of Galilee

(ca. 1900),

Early Agricultural Remnants and Technical Heritage (EARTH)

* Patricia C. Anderson

on the EARTH site. * ttp://www.cepam.cnrs.fr/index2.php?page=ProCompTech/production/France Reconstruction of a Mesopotamian threshing sledge reprint from EARTH *

tribulum: reconstitution d'un traineau à dépiquer mésopotamien

"Threshing board: Reconstruction of a Mesopotamian threshing sledge" (drawings), Centre d'études Préhistorique, Antiquité, Moyen Âge (CEPAM), University of Nice

Threshing sledges from the Bronze Age and today

(CEPAM / Centre de Recherches Archéologiques - CNRS) *

(Rural World Day 2000). Pictures from Miranda de Arga (Navarre, Spain). * Laureano Molina Gómez

("Grandfather's Threshing board"), etnografo.com. * Amparo Siguer

Los trilleros

("The threshers"), ''Revista de Folklore''; includes some illustrations {{DEFAULTSORT:Threshing Board History of agriculture Agricultural machinery Grain production Threshing tools

cereal

A cereal is any grass cultivated for the edible components of its grain (botanically, a type of fruit called a caryopsis), composed of the endosperm, germ, and bran. Cereal grain crops are grown in greater quantities and provide more food ...

s from their straw

Straw is an agricultural byproduct consisting of the dry stalks of cereal plants after the grain and chaff have been removed. It makes up about half of the yield of cereal crops such as barley, oats, rice, rye and wheat. It has a number ...

; that is, to thresh

Thresh may refer to:

*Threshing, in agriculture

**Threshing machine

* A minor character in the novel ''The Hunger Games'' and its film adaptation

*Thresh (gamer)

Dennis Fong (), better known by his online alias Thresh, is an American businessm ...

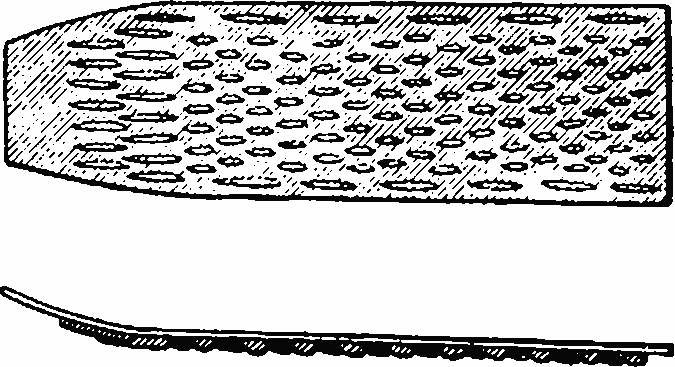

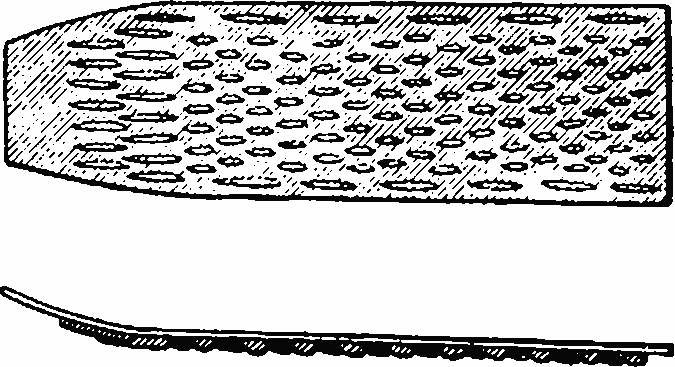

. It is a thick board, made with a variety of slats, with a shape between rectangular and trapezoidal, with the frontal part somewhat narrower and curved upward (like a sled or sledge) and whose bottom is covered with lithic flake

In archaeology, a lithic flake is a "portion of rock removed from an objective piece by percussion or pressure,"Andrefsky, W. (2005) ''Lithics: Macroscopic Approaches to Analysis''. 2d Ed. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press and may also be ref ...

s or razor

A razor is a bladed tool primarily used in the removal of body hair through the act of shaving. Kinds of razors include straight razors, safety razors, disposable razors, and electric razors.

While the razor has been in existence since bef ...

-like metal blades.

One form, once common by the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

, was "about three to four feet wide and six feet deep (these dimensions often vary, however), consisting of two or three wooden planks assembled to one another, of more than four inches wide, in which is several hard and cutting flints crammed into the bottom part pull along over the grains. In the rear part there is a large ring nailed, that is used to tie the rope that pulls it and to which two horses are usually harnessed; and a person, sitting on the threshing board, drives it in circles over the cereal that is spread on the threshing floor. Should the person need more weight, he need only put some big stones over it."

The dimensions of threshing boards varied. In Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, they could be up to approximately two metres in length and a metre and a half wide. There were also smaller threshing boards, as little about a metre-and-a-half long and a metre wide. The thickness of the slats of the threshing board is some five or six cm. Nonetheless, since threshing boards are nowadays custom made, made to order or made smaller as an adornment or souvenir, they may range from miniatures up to the sizes previously described.

The threshing board has been traditionally pulled by mules or by oxen over the grains spread on the threshing floor

Threshing (thrashing) was originally "to tramp or stamp heavily with the feet" and was later applied to the act of separating out grain by the feet of people or oxen and still later with the use of a flail. A threshing floor is of two main typ ...

. As it was moved in circles over the harvest that was spread, the stone chips or blades cut the straw

Straw is an agricultural byproduct consisting of the dry stalks of cereal plants after the grain and chaff have been removed. It makes up about half of the yield of cereal crops such as barley, oats, rice, rye and wheat. It has a number ...

and the ear of wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

(which remained between the threshing board and the pebbles on the ground), thus separating the seed without damaging it. The threshed grain was then gathered and set to be cleaned by some means of winnowing

Winnowing is a process by which chaff is separated from grain. It can also be used to remove pests from stored grain. Winnowing usually follows threshing in grain preparation. In its simplest form, it involves throwing the mixture into the ...

.

Traditional threshing systems

Until the arrival of

Until the arrival of combine harvester

The modern combine harvester, or simply combine, is a versatile machine designed to efficiently harvest a variety of grain crops. The name derives from its combining four separate harvesting operations— reaping, threshing, gathering, and win ...

s, which reap, thresh and clean grain in a single process, the traditional methods of threshing cereals and some legume

A legume () is a plant in the family Fabaceae (or Leguminosae), or the fruit or seed of such a plant. When used as a dry grain, the seed is also called a pulse. Legumes are grown agriculturally, primarily for human consumption, for livestock for ...

s were those described by Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

in his '' Natural History'', with three variants: "The cereals are threshed in some places with the threshing board on the threshing floor; in others they are trampled by a train of horses, and in others they are beaten with flails".

In this manner, Pliny refers to the three traditional methods of threshing grain:

* Beating sheafs of grain against a crushing stone or lump of wood.

* Trampling grain spread on the threshing floor; the trampling would be done by a train of mules or oxen

* Threshing with flail

A flail is an agriculture, agricultural tool used for threshing, the process of separating cereal, grains from their husks.

It is usually made from two or more large sticks attached by a short chain; one stick is held and swung, causing the othe ...

s, a type of traditional wooden tool with which one strikes the pile of grain until the seed is separated from the chaff

Chaff (; ) is the dry, scaly protective casing of the seeds of cereal grains or similar fine, dry, scaly plant material (such as scaly parts of flowers or finely chopped straw). Chaff is indigestible by humans, but livestock can eat it. In agri ...

.

Threshing with the threshing board

The threshing board is a historical form of threshing that can still be seen in some regions that practice a marginal agriculture. It is also somewhat preserved as an occasional folkloric and ceremonial practice, to commemorate traditional local customs. For threshing with the threshing board, firstly one brings the baled stalks to the threshing floor. Some are stacked, waiting their turn, and others are untied and placed in a circle forming a pile of grain that is heated by the sun. Then, the farmers drag the threshing board over the stalks, first going several times around in circles, and then in figure-eights, and stirring the grain with a woodenpitchfork

A pitchfork (also a hay fork) is an agricultural tool with a long handle and two to five tines used to lift and pitch or throw loose material, such as hay, straw, manure, or leaves.

The term is also applied colloquially, but inaccurately, to ...

. Sometimes, this work was done with another kind of threshing implement: a ''Plostellum punicum'' (Latin; literally "Punic cart") or threshing cart, fitted with a group of rollers, each with metallic transverse razors. In this first stage, the straw is detached from the ear; much chaff and dirty dust remains, mixed with the edible grain. Every time that the work of dragging the threshing board is repeated, the grain is stirred again, moving more straw to the edge of the threshing floor. If too much grain is spread on the ground, it has to be raked and swept in order to make a round mound and, if possible, to remove as much straw as possible.

After turning the grain and straw upside down and leaving it to dry during a lunch break, the farmers carry out a second round of threshing in order to separate the last of the grain from the straw. Then, they use pitchforks, rakes and brooms to create a mound. A pair of oxen or mules pulls the threshing board by means of a chain or a strap fixed to a hook nailed in the front plank; donkey

The domestic donkey is a hoofed mammal in the family Equidae, the same family as the horse. It derives from the African wild ass, ''Equus africanus'', and may be classified either as a subspecies thereof, ''Equus africanus asinus'', or as ...

s are not used, because unlike mules and oxen they often defecate on the crops. The driver rides on the threshing board, both guiding the draft animals and increasing the weight of the threshing board. If the driver's weight is not enough, large stones are put on the board. In recent times, the animals are sometimes replaced with a tractor

A tractor is an engineering vehicle specifically designed to deliver a high tractive effort (or torque) at slow speeds, for the purposes of hauling a trailer or machinery such as that used in agriculture, mining or construction. Most commo ...

; because the driver no longer sits on the board, the weight of stones becomes more important. Children enjoy riding on the threshing board for fun, and the farmers allow it because their weight is useful, as long as the children are not too boisterous. During this process, if the stalks are excessively squashed, two large metal arcs are affixed to the back of the threshing board; these turn-up and give volume to the straws, behind the threshing.

After threshing is finished, to avoid mixing the dirty remnants with the clean, new stalks, the threshing floor must be cleaned first with a rake to move the heavier material, and then with several brooms (in the narrow sense: they are typically made from " broom shrub"—''Cytisus scoparius

''Cytisus scoparius'' ( syn. ''Sarothamnus scoparius''), the common broom or Scotch broom, is a deciduous leguminous shrub native to western and central Europe. In Britain and Ireland, the standard name is broom; this name is also used for oth ...

''—and are stronger than domestic brooms). Also the straw was accumulated carefully and stored, because it was a good fodder

Fodder (), also called provender (), is any agricultural foodstuff used specifically to feed domesticated livestock, such as cattle, rabbits, sheep, horses, chickens and pigs. "Fodder" refers particularly to food given to the animals (includ ...

for livestock

Livestock are the domesticated animals raised in an agricultural setting to provide labor and produce diversified products for consumption such as meat, eggs, milk, fur, leather, and wool. The term is sometimes used to refer solely to ani ...

. The entire process of threshing generates a thin dust that soaks in through the respiratory system

The respiratory system (also respiratory apparatus, ventilatory system) is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies g ...

and sticks to the throat

In vertebrate anatomy, the throat is the front part of the neck, internally positioned in front of the vertebrae. It contains the pharynx and larynx. An important section of it is the epiglottis, separating the esophagus from the trachea (windpip ...

.

During the sweeping, the husk

Husk (or hull) in botany is the outer shell or coating of a seed. In the United States, the term husk often refers to the leafy outer covering of an ear of maize (corn) as it grows on the plant. Literally, a husk or hull includes the protective ...

s and the chaff

Chaff (; ) is the dry, scaly protective casing of the seeds of cereal grains or similar fine, dry, scaly plant material (such as scaly parts of flowers or finely chopped straw). Chaff is indigestible by humans, but livestock can eat it. In agri ...

are separated to one part of the threshing-floor, while the grain, still not entirely clean, was winnowed, either by traditional of winnowing

Winnowing is a process by which chaff is separated from grain. It can also be used to remove pests from stored grain. Winnowing usually follows threshing in grain preparation. In its simplest form, it involves throwing the mixture into the ...

with sieve

A sieve, fine mesh strainer, or sift, is a device for separating wanted elements from unwanted material or for controlling the particle size distribution of a sample, using a screen such as a woven mesh or net or perforated sheet materia ...

s, or by a mechanical winnowing machine.

Traditional threshing implements (including the threshing board) were gradually abandoned and replaced by modern combine harvesters. This change, of course, occurred in some areas before others. For instance, in Spain, it happened in the 1950s and 1960s.

Until that time, threshing boards were made in certain particular towns and villages with specialised craftsmen. Whereas the woodworking involved is simple, even rough, the flintknapping and the inlaying of flakes into the bottom of board need specialised skills that were passed from father to son. The most famous Spanish town for this work was, doubtlessly, Cantalejo

Cantalejo is a municipality located in the Segovia (province), province of Segovia, Castile and León, Spain. According to the 2004 census (Instituto Nacional de Estadística (Spain), INE), the municipality had a population of 3,622 inhabitants. ...

(Segovia

Segovia ( , , ) is a city in the autonomous community of Castile and León, Spain. It is the capital and most populated municipality of the Province of Segovia.

Segovia is in the Inner Plateau ('' Meseta central''), near the northern slopes of t ...

), where the craftsmen who made threshing boards were known as ''briqueros''.

History

Origins in the Neolithic and Copper Age

Patricia C. Anderson (of ''Centre d’Etudes Préhistoire, Antiquité et Moyen Age del

Patricia C. Anderson (of ''Centre d’Etudes Préhistoire, Antiquité et Moyen Age del CNRS

The French National Centre for Scientific Research (french: link=no, Centre national de la recherche scientifique, CNRS) is the French state research organisation and is the largest fundamental science agency in Europe.

In 2016, it employed 31,63 ...

''), discovered archaeological remains that demonstrate the existence of threshing boards at least 8,000 years old in the Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

and Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

. The artefacts are lithic flake

In archaeology, a lithic flake is a "portion of rock removed from an objective piece by percussion or pressure,"Andrefsky, W. (2005) ''Lithics: Macroscopic Approaches to Analysis''. 2d Ed. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press and may also be ref ...

s and, above all obsidian

Obsidian () is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed when lava extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal growth. It is an igneous rock.

Obsidian is produced from felsic lava, rich in the lighter elements such as silicon ...

or flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Flint was widely used historically to make stone tools and start ...

blade

A blade is the portion of a tool, weapon, or machine with an edge that is designed to puncture, chop, slice or scrape surfaces or materials. Blades are typically made from materials that are harder than those they are to be used on. Histor ...

s, recognizable through the type of microscopic wear that it has. Her work was completed by Jacques Chabot (of the ''Centre interuniversitaire d'études sur les lettres, les arts et les traditions'', CELAT), who has studied Mitanni

Mitanni (; Hittite cuneiform ; ''Mittani'' '), c. 1550–1260 BC, earlier called Ḫabigalbat in old Babylonian texts, c. 1600 BC; Hanigalbat or Hani-Rabbat (''Hanikalbat'', ''Khanigalbat'', cuneiform ') in Assyrian records, or '' Naharin'' ...

(northern Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

and Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''O ...

). Both count among their specialties the study of microwear analysis Use-wear analysis is a method in archaeology to identify the functions of artifact tools by closely examining their working surfaces and edges. It is mainly used on stone tools, and is sometimes referred to as "traceological analysis" (from the neo ...

, through which it is possible to take a particular piece of flint or obsidian (to take the most common examples) and determine the tasks for which it was used.

Concretely, the cutting of cereals leaves a very characteristic ''glossy

Gloss is an optical property which indicates how well a surface reflects light in a specular (mirror-like) direction. It is one of the important parameters that are used to describe the visual appearance of an object. The factors that affect glo ...

'' pattern of wear, owing to the presence of microscopic mineral particles (''phytolith

Phytoliths (from Greek, "plant stone") are rigid, microscopic structures made of silica, found in some plant tissues and persisting after the decay of the plant. These plants take up silica from the soil, whereupon it is deposited within different ...

s'') in the stalks of the plants. Therefore, scholars using controlled experimental replication studies and functional analysis with a scanning electron microscope are able to identify stone artefacts that were used as sickle

A sickle, bagging hook, reaping-hook or grasshook is a single-handed agricultural tool designed with variously curved blades and typically used for harvesting, or reaping, grain crops or cutting Succulent plant, succulent forage chiefly for feed ...

s or the teeth of threshing boards. The edge damage on the pieces used in threshing boards is distinct because, besides the ''glossy'' abrasion characteristic of cutting cereals, they have micro-scars from chipping, as a result of the blows of the threshing board against the rock surface of the threshing floor. (p. 222 and footnote 10)

The most productive archaeological site

An archaeological site is a place (or group of physical sites) in which evidence of past activity is preserved (either prehistoric or historic or contemporary), and which has been, or may be, investigated using the discipline of archaeology an ...

is Aratashen, Armenia: a village occupied between 5000 and 3000 BC (Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several pa ...

and Copper Age

The Copper Age, also called the Chalcolithic (; from grc-gre, χαλκός ''khalkós'', "copper" and ''líthos'', " stone") or (A)eneolithic (from Latin '' aeneus'' "of copper"), is an archaeological period characterized by regular ...

). The archaeological excavations

In archaeology, excavation is the exposure, processing and recording of archaeological remains. An excavation site or "dig" is the area being studied. These locations range from one to several areas at a time during a project and can be condu ...

have provided thousands of pieces from the knapping of obsidian (suggesting that Aratashen was a centre of production and trade of artefacts of that highly regarded stone); the rest of the archaeological record

The archaeological record is the body of physical (not written) evidence about the past. It is one of the core concepts in archaeology, the academic discipline concerned with documenting and interpreting the archaeological record. Archaeological t ...

consists mainly of fragments of common pottery, ground stone

In archaeology, ground stone is a category of stone tool formed by the grinding of a coarse-grained tool stone, either purposely or incidentally. Ground stone tools are usually made of basalt, rhyolite, granite, or other cryptocrystalline a ...

s, and other agricultural tools. Analysing a sample of 200 lithic flakes and blades, selected from the best-preserved pieces, it is possible to differentiate between those used in sickles and those used in threshing boards. The lithic blades of obsidian were knapped using highly developed and standardized methods, such as the use of a "pectoral crutch" with a copper point. Beginning at the headwaters of the river Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

, where this site is located, the craftsmen and peddlers sold their wares throughout the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

.

The threshing boards must have been important in the protohistory

Protohistory is a period between prehistory and history during which a culture or civilization has not yet developed writing, but other cultures have already noted the existence of those pre-literate groups in their own writings. For example, in ...

of Mesopotamia, since they already appear in some of the oldest written documents discovered: specifically, several sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicat ...

tablets from the early town of Kish

Kish may refer to:

Geography

* Gishi, Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan, a village also called Kish

* Kiş, Shaki, Azerbaijan, a village and municipality also spelled Kish

* Kish Island, an Iranian island and a city in the Persian Gulf

* Kish, Iran, ...

(Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

), engraved with cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo- syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge- ...

pictograms

A pictogram, also called a pictogramme, pictograph, or simply picto, and in computer usage an icon, is a graphic symbol that conveys its meaning through its pictorial resemblance to a physical object. Pictographs are often used in writing and g ...

, which could be the world's oldest surviving written record, dating to the middle of the 4th millennium BC

The 4th millennium BC spanned the years 4000 BC to 3001 BC. Some of the major changes in human culture during this time included the beginning of the Bronze Age and the invention of writing, which played a major role in starting recorded history. ...

(Early Uruk period

The Uruk period (ca. 4000 to 3100 BC; also known as Protoliterate period) existed from the protohistoric Chalcolithic to Early Bronze Age period in the history of Mesopotamia, after the Ubaid period and before the Jemdet Nasr period. Named af ...

). One of these tablets, preserved in the Ashmolean Museum

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology () on Beaumont Street, Oxford, England, is Britain's first public museum. Its first building was erected in 1678–1683 to house the cabinet of curiosities that Elias Ashmole gave to the University o ...

of Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, appears to have pictures of threshing boards on both faces, next to some numeric symbols and other pictograms. These presumed threshing boards (which might instead be sledges) have a shape similar to threshing carts that were used until recently in parts of the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

where non-industrial agriculture survived. Descriptions also appear in numerous cuneiform clay tablet

In the Ancient Near East, clay tablets (Akkadian ) were used as a writing medium, especially for writing in cuneiform, throughout the Bronze Age and well into the Iron Age.

Cuneiform characters were imprinted on a wet clay tablet with a sty ...

s as early as the third millennium BC.

There are another representation, in this case without writing, in central Turkey. It is an impression of a

There are another representation, in this case without writing, in central Turkey. It is an impression of a cylinder seal

A cylinder seal is a small round cylinder, typically about one inch (2 to 3 cm) in length, engraved with written characters or figurative scenes or both, used in ancient times to roll an impression onto a two-dimensional surface, generally ...

from the archaeological site of Arslantepe-Malatya, which appeared near of the named «Temple B». The archaeological layers were dated to 3374 BC using dendrochronology

Dendrochronology (or tree-ring dating) is the scientific method of dating tree rings (also called growth rings) to the exact year they were formed. As well as dating them, this can give data for dendroclimatology, the study of climate and atm ...

. The stamp shows a figure seated on a threshing board, with a clear image of the lithic flakes inlaid in the bottom of the board. The main figure is sitting (possibly on a throne

A throne is the seat of state of a potentate or dignitary, especially the seat occupied by a sovereign on state occasions; or the seat occupied by a pope or bishop on ceremonial occasions. "Throne" in an abstract sense can also refer to the mon ...

) under a dossal

A Dossal (or dossel, dorsel, dosel), from French ''dos'' (''back''), is one of a number of terms for something rising from the back of a church altar. In modern usage, it primarily refers to cloth hangings but it can also denote a board, ofte ...

. In front is a driver or oxherd, and there are peasants with pitchforks nearby. According to M. A. Frangipane, that the seal may illustrate a religious scene:

It closely resembles another scene, painted on the walls of the same site (a ceremonial procession of a person of high rank, painted in an archaic lineal style in the colours red and black), although the current condition of the wall obscures the exact nature of the vehicle in which he is seated, it is indeed possible to see that it is pulled by a pair of oxen. Professor Sherratt interprets both scenes as presenting manifestations of civil or religious power. In that era, the threshing board was a sophisticated and expensive implement, built by specialized artisans, using pieces of flint or obsidian; in the case of Lower Mesopotamia, these were imported from far away: in the alluvial plateau of Sumer, as in all south of Mesopotamia, it was impossible to find stone, not even a pebble. p.90.

Furthermore, threshing required a threshing floor composed of natural rock, cobbles or, at least, very hard and compressed ground, located in a sunny place situated in a rise in the ground with a constant dry wind, and with a flat base that would not allow puddles to form when it rained. So, a threshing floor was not available to just anybody. It was expensive, as we can see from the biblical citations in the following section. Also, it required draft animals, expensive and difficult to drive (because this was not a matter of having them walk in a straight line). All this meant that a threshing implement required a large amount of harvested grain to pay off the expenditure. Thus, the rise of the threshing board turns on a distinctive, sophisticated system of powerful elites.

The discovery of a ceremonial sledge (perhaps a threshing board) with gold ornaments in the Tomb of Pu-Abi, one of the "royal tombs" of Ur, dated from the 3rd millennium BC, makes clear the underlying problem of distinguishing in the ancient representations between a true threshing board and a sledge (that is, an unwheeled vehicle for hauling freight). Although we know that the threshing board appears no later than the 4th millennium BC

The 4th millennium BC spanned the years 4000 BC to 3001 BC. Some of the major changes in human culture during this time included the beginning of the Bronze Age and the invention of writing, which played a major role in starting recorded history. ...

(as we can see in ''Atarashen'' and ''Arslantepe-Malatya''), and we also know that the wheel was invented in Mesopotamia in the middle of that same millennium, still, the utilisation and spread of the wheel was not instantaneous. The sledges survived at least until the invention of the articulated axle, nearly 2000 BC. During this time, some vehicles were hybrids: sledges with wheels that could be dismantled to overcome obstacles by carrying it on shoulders or, simply, dragging it. Consequently—except in the case of Arslantepe, where the lithic flakes are clear visible—we cannot determine whether these representations are threshing boards or sledges for freight or for rites.

James Frazer

Sir James George Frazer (; 1 January 1854 – 7 May 1941) was a Scottish social anthropologist and folklorist influential in the early stages of the modern studies of mythology and comparative religion.

Personal life

He was born on 1 Janua ...

compiled numerous ceremonies of harvest and thresh, that centered on a ''Cereal Spirit''. From the Ancient Egyptian era to pre-industrial period, this spirit seems to have reside d in the first threshed sheaf or, sometimes, in the last one.

Biblical references

The first biblical mention of the threshing floor is in . As such, it was not a shed, building, or any place covered with a roof and surrounded by walls, but a circular piece of ground from fifty to a hundred feet in diameter, in the open air, on elevated ground, and made smooth, hardy, and clean. Here the grain was threshed and winnowed. In the Bible are found four modes of threshing grain (some of which modes are expounded in : * With a rod or flail. This was for small, delicate seeds such as fitches and cummin. It was also used when only small quantities of grain was to be threshed, or when it was necessary to conceal the operation from an enemy. Examples are found in , when Ruth "beat out" what she had gleaned during the day, and , when Gideon "threshed (Hebrew, ''chabat'', "beat out") wheat by the winepress to hide it from the Midianites." * With the ''charuts,'' Hebrew for "threshing instrument." This is the threshing board or sledge under discussion in this article. * With the ''agalah,'' Hebrew for "cart-wheel." This type of threshing instrument is probably referred to in . The term ''agalah'' is supposed to have been the same as the ''morag,'' "threshing instrument," mentioned in , , and , though some make the ''morag'' and the ''charuts'' the same. This instrument is still known in Egypt by the name of ''mowrej.'' It consists of three or four heavy rollers of wood, iron, or stone, roughly made and joined in a square frame, which is in the form of a sledge or drag. Rollers are said to be like barrels of an organ with their projections. Cylinders are parallel with each other and are stuck full of spikes having sharp square points. It is used the same way as the ''charuts''. The driver sits on the machine, and with his weight helps to keep it down. (Authorities are not agreed as to the differences between the ''charuts'', the ''morag'', and the ''agalah''.) * By treading. The last mode is that of simply treading out the grain with a horse or an ox. is an example of this. The Egyptians used this rather inefficient mode of threshing with multiple oxen, and this mode is still in use in the East. All four methods are discussed at length in the Talmud.Moriah

Moriah ( Hebrew: , ''Mōrīyya''; Arabic: ﻣﺮﻭﻩ, ''Marwah'') is the name given to a mountainous region in the Book of Genesis, where the binding of Isaac by Abraham is said to have taken place. Jews identify the region mentioned in Genes ...

(as well as Mount Moriah itself). In it, the Lord's directive to Gad, King David's prophet, was to instruct David to "rear an altar unto the Lord in the threshingfloor of Araunah the Jebusite

The Jebusites (; ISO 259-3 ''Ybusi'') were, according to the books of Joshua and Samuel from the Tanakh, a Canaanite tribe that inhabited Jerusalem, then called Jebus (Hebrew: ''Yəḇūs'', "trampled place") prior to the conquest initiated b ...

" ( and ) during the end of the three-day plague that was then ensuing upon David's people of Israel. In the 1 Chronicles

The Book of Chronicles ( he, דִּבְרֵי־הַיָּמִים ) is a book in the Hebrew Bible, found as two books (1–2 Chronicles) in the Christian Old Testament. Chronicles is the final book of the Hebrew Bible, concluding the third sect ...

account, the purchase of the entire hilltop of Mount Moriah is the subject, which is why the purchase price (verse 25) is different from the 2 Samuel account.

This selection is highly significant for several reasons:

* It was selected by the Lord (not David) (, ).

* Araunah's threshing floor was located on a hilltop called Mount Moriah. It is the same location of Abraham's attempted sacrifice of his son, Isaac ().

* The typology

Typology is the study of types or the systematic classification of the types of something according to their common characteristics. Typology is the act of finding, counting and classification facts with the help of eyes, other senses and logic. Ty ...

of the threshing floor is signified by and . It means that only the grain is gathered and admitted into the kingdom of God, while the chaff is cast into the unquenchable fire.

* On this hilltop was later built Solomon's Temple (), whose own typology heightens the significance of the threshing floor typology.

The selected place, Mount Moriah, was owned by Araunah (or, ''Ornan'') the Jebusite, a rich villager who owned and operated the threshing floor on Mount Moriah. Araunah was awed by the visit of the king and offered his oxen to

The selected place, Mount Moriah, was owned by Araunah (or, ''Ornan'') the Jebusite, a rich villager who owned and operated the threshing floor on Mount Moriah. Araunah was awed by the visit of the king and offered his oxen to sacrifice

Sacrifice is the offering of material possessions or the lives of animals or humans to a deity as an act of propitiation or worship. Evidence of ritual animal sacrifice has been seen at least since ancient Hebrews and Greeks, and possibly exis ...

and the threshing boards and other implements as wood for the sacrifice. Even so, David rejected any gift to come from a pagan and instead affirmed his intent to purchase first the oxen and threshing floor, then, later, the whole of Mount Moriah that contained it. Had David accepted Araunah's offer, it would have been Araunah's sacrifice instead of David's.

The references to the purchase are ostensively contradictory about the purchase price; it is 50 shekel

Shekel or sheqel ( akk, 𒅆𒅗𒇻 ''šiqlu'' or ''siqlu,'' he, שקל, plural he, שקלים or shekels, Phoenician: ) is an ancient Mesopotamian coin, usually of silver. A shekel was first a unit of weight—very roughly —and became c ...

s of silver

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical ...

according to , and 600 shekels of gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile ...

according to . However, this contradiction is only on the surface. The 50 shekels was the initial price to purchase the two oxen and the threshing floor, but the later price of 600 shekels was paid to purchase the property of Mount Moriah ''in addition'' to the oxen and threshing floor ''contained within'' and ''earlier purchased''.

Generally, all threshing floors were located on hilltops, not to associate with the various gods, but to expose them to prevailing winds that assist in the process of winnowing. The wind adds to the typology of the threshing floor, as the wind is a type of the Holy Ghost (see ).

The last biblical mention of threshing floors is in and . The term "floor" is the Greek ''halon'' which means threshing floor, and this fits the import of the two verses. The typology of the threshing floor on Mount Moriah, Solomon's Temple, and these two verses are significant.

As for the word "thresh," the last biblical mention is in , again showing the typology of separating the chaff from the wheat.

Classical Greece and Rome

During the early history of Greece and Rome the threshing board was not used. Only after the development of commerce (with occurred in the 5th and 4th centuries in Greece and 2nd and 1st centuries in Rome) and the subsequent transmission of information from the near east that it became widely used. According to V.V. Struve, who cites, in part, verses ofThe Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Ody ...

, the Greeks of the 8th century BC threshed cereals by trampling them with oxen:

Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

, which colonized the southeastern Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

in the 3rd century BC, had advanced agricultural technology, greatly superior to the Roman techniques of the time. Their methods astonished travellers such as Agathocles Agathocles ( Greek: ) is a Greek name, the most famous of which is Agathocles of Syracuse, the tyrant of Syracuse. The name is derived from , ''agathos'', i.e. "good" and , ''kleos'', i.e. "glory".

Other personalities named Agathocles:

*Agathocles ...

and Regulus

Regulus is the brightest object in the constellation Leo and one of the brightest stars in the night sky. It has the Bayer designation designated α Leonis, which is Latinized to Alpha Leonis, and abbreviated Alpha Leo or α Leo. Re ...

, and were an inspiration for the writings of Varro

Marcus Terentius Varro (; 116–27 BC) was a Roman polymath and a prolific author. He is regarded as ancient Rome's greatest scholar, and was described by Petrarch as "the third great light of Rome" (after Vergil and Cicero). He is sometimes calle ...

and Pliny. One well-known Carthaginian agronomist, '' Mago'', wrote a treatise that was translated into Latin by order of the Roman Senate. The ancient Romans describe Tunisia, today mainly desert, as a fertile landscape of olive groves and wheat fields. In Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hi ...

, the Carthaginians are known to have introduced several new crops (mainly fruit tree

A fruit tree is a tree which bears fruit that is consumed or used by animals and humans — all trees that are flowering plants produce fruit, which are the ripened ovaries of flowers containing one or more seeds. In horticultural usage, t ...

s) and some machines like the threshing board, either the version with stone-chips (''tribulum'' in Latin) or the version with rollers (''threshing cart'', named in their honour ''plostellum punicum'' by the Romans).

In Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, the threshing board had only economic significance, without the religious symbolism it took on in ancient Israel

The history of ancient Israel and Judah begins in the Southern Levant during the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age. "Israel" as a people or tribal confederation (see Israelites) appears for the first time in the Merneptah Stele, an inscri ...

. The treatises of agriculture written by Roman experts as Cato, Varro, Columella and Pliny the Elder (quoted above), touch the topic of threshing. In chronological order:

*Cato: In the time of Cato the Elder

Marcus Porcius Cato (; 234–149 BC), also known as Cato the Censor ( la, Censorius), the Elder and the Wise, was a Roman soldier, senator, and historian known for his conservatism and opposition to Hellenization. He was the first to write hi ...

—that is, the 2nd century BC—Rome was intensely connected with the conquered areas of Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

and Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

, whose higher degree of agricultural development threatened Roman traditionalism. Cato's book ''De Agricultura'' was against exotic innovations such as the threshing board in its different variants, defending instead a traditional agricultural system based on manual labour. To some writers, Cato's ideas drove, indirectly, to the disintegration of republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

society and even the imperial economy. Cato preferred threshing by trampling by mules or oxen. He doesn't expressly mention the threshing board, in spite of the fact it was already spreading through the empire. It is, then, "almost impossible to define, on the basis of Cato's report, when this or that implement or refinement came into use".

*Varro: Unlike Cato, Marcus Terentius Varro

Marcus Terentius Varro (; 116–27 BC) was a Roman polymath and a prolific author. He is regarded as ancient Rome's greatest scholar, and was described by Petrarch as "the third great light of Rome" (after Vergil and Cicero). He is sometimes calle ...

was not a man of action but a scholar, a πολιγραφοτάτω, in the 1st century BC. Varro, whose studies were wider than Cato's, tried to combine the cosmopolitan Greek outlook with Rome's provincial traditions. In his book of agricultural advice ''Rerum Rusticarum de Agri Cultura'' Varro only twice reflects the reality of his times by mentioning threshing boards. He advises, "None of the implements that can be produced in the plantation (farm) itself should be bought, as with almost all everything which is made from unfinished wood such as hampers, baskets, threshing boards, stakes, rakes…"; the inclination to self-sufficiency that he demonstrates here would later be harmful to Rome. Varro nonetheless shows himself more open to innovation that Cato: "To achieve an abundant and high-quality harvest, the stalks should be taken to the threshing floor without piling them up, so the grain is in the best condition, and the grain (should be) separated from the stalks on the threshing floor, a process which is done, among other ways, with a pair of mules and a threshing board. This is made with a wooden board (with its underside) equipped with stone-chips or saws of iron, which, with a plow in front or a large counterweight, is pulled by a pair of mules yoked together and thus separates the grain from the stalks…". That is, he explains in a very didactic way how the threshing boards works and the advantages of this innovative device. Next, he talks about the variant called ''plostellum poenicum'' (=''punicum''=Punic=Carthaginian), a threshing implement with rollers and metallic saws whose origin is, as we have already seen, Carthaginian, and which was used in Hispania (which had, in the past, been controlled by Carthage): "Another way to make it is by means of a cart with teethed rollers and bearings; this cart is named ''plostellum punicum'', in which one can sit and move the device that is pulled by mules, as it is done in Hispania Citerior

Hispania Citerior (English: "Hither Iberia", or "Nearer Iberia") was a Roman province in Hispania during the Roman Republic. It was on the eastern coast of Iberia down to the town of Cartago Nova, today's Cartagena in the autonomous community of ...

and other places."

*Columella ( Lucius Junius Moderatus, beginning of Common Era - 60s): a native of Hispania Baetica

Hispania Baetica, often abbreviated Baetica, was one of three Roman provinces in Hispania (the Iberian Peninsula). Baetica was bordered to the west by Lusitania, and to the northeast by Hispania Tarraconensis. Baetica remained one of the basic di ...

; after finishing his military career, Columella worked managing large estates. This writer from Hispania brings a new note to this topic, writing, in this case, about threshing floor

Threshing (thrashing) was originally "to tramp or stamp heavily with the feet" and was later applied to the act of separating out grain by the feet of people or oxen and still later with the use of a flail. A threshing floor is of two main typ ...

s: "The threshing floor, if it is possible, must be placed in such way that it can be overseen by the master or by the foreman; the best is one that is cobbled, because not only allows that the cereal be quickly threshed, since the ground don't give way to the blows of hoofs and threshing boards, but also, these cereals, before being winnowed, are cleaner and lack the pebbles and little clods that always remaine in a threshing floor of pressed earth."

*Pliny: Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

(23 - 79) only compiles what his predecessors had written, which we have already quoted.

Middle Ages

In

In Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

, the barbarian invasions

The Migration Period was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories by various tribes, and the establishment of the post-Roman ...

of Europe had detrimental effects upon agriculture, leading to the loss of many of the more advanced techniques, among them the threshing board, which was completely alien to Germanic tradition. The eastern Mediterranean areas, on the other hand, continued the use of the threshing board, passing into the Muslim culture, where it took deep root.

In the Iberian Peninsula, in the Visigothic kingdom

The Visigothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of the Goths ( la, Regnum Gothorum), was a kingdom that occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic successor states to ...

and the Christian zone during the ''Reconquista

The ' ( Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the N ...

'', the threshing board was little known (although awareness of it never quite disappeared). The degradation extended not only to the economy, but also to the very sources that we have to study the period: scholars are confronted with a documentary void that is difficult to get around. It is certain that in Islamic Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

, the threshing board continued to be very popular, which led to the Christians recuperating the tradition as they advanced in the ''Reconquista

The ' ( Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the N ...

.'' This act coincides with a generalized recovery in all of Europe. Economic prosperity began to return at the start of the 11th century; the experts speak of the increased area of tilled lands; the increased use of draft animals (first oxen, thanks to the frontal yoke, and later horses, thanks to harness collar); of the increase in metal tools and improved metalworking; of the appearance of the moldboard plough, often with wheels; and the increase in watermills. Livestock became a sign of progress: peasants, less dependent and more prosperous, became able to buy draft animals, and even plows. The peasants who had their own plow and one or two draft animals were a small elite, pampered by the feudal lord, who acquired a distinct status,

that of ''yeoman farmers'', quite distinct from ''farm-hand labourer'' whose only tool was their own arms.. The existence of draft animals does not imply the diffusion of the threshing board in Western Europe, where the flail continued to be the preferred threshing implement. On the other hand, in Spain, the weight of Eastern tradition made the difference: Professor Julio Caro Baroja

Julio Caro Baroja (13 November 1914 – 18 August 1995) was a Spanish anthropologist, historian, linguist and essayist. He was known for his special interest in Basque culture, Basque history and Basque society. Of Basque ancestry, he was the ...

admits that in Spain the threshing board appears cited or represented in works of art. Concretely, he mentions some Romanesque reliefs in Beleña (Salamanca

Salamanca () is a city in western Spain and is the capital of the Province of Salamanca in the autonomous community of Castile and León. The city lies on several rolling hills by the Tormes River. Its Old City was declared a UNESCO World Herit ...

) and Campisábalos (Guadalajara

Guadalajara ( , ) is a metropolis in western Mexico and the capital of the state of Jalisco. According to the 2020 census, the city has a population of 1,385,629 people, making it the 7th largest city by population in Mexico, while the Guadalaj ...

), both from the 12th century. One may add a document written in 1265, in which a woman named Doña Mayor (widow of one Don Arnal, an ecclesiastical tax collector, and thus a person of good position), leaves to the diocese

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associ ...

chapter of Salamanca

Salamanca () is a city in western Spain and is the capital of the Province of Salamanca in the autonomous community of Castile and León. The city lies on several rolling hills by the Tormes River. Its Old City was declared a UNESCO World Herit ...

her inheritance of ''Valcuevo'', a farm in the municipality of Valverdón, Salamanca:

And I, Doña Mayor, leave on my death these two yokings of country state above referred to the Cathedral Chapter, well preserved with 76These documents, at least testify for the presence of threshing boards, which, undoubtedly was continuous from then until recently in the Mediterranean basin. The rest is mere generalized speculation, given that traditional historiography centers on features more like ofbushel A bushel (abbreviation: bsh. or bu.) is an imperial and US customary unit of volume based upon an earlier measure of dry capacity. The old bushel is equal to 2 kennings (obsolete), 4 pecks, or 8 dry gallons, and was used mostly for agric ...s of wheat, 38 bushels of rye, and 38 bushels of barley to seed each yoking and with ploughshares, and with plows, and with ploughbeams, and with threshing boards and with all the accoutrements that a well-laid-out property should have.

Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

. In any case, none of the consulted authors describe the threshing board as playing a relevant part in the progress of medieval agriculture. We must, then, join with the despair of French historian Georges Duby

Georges Duby (7 October 1919 – 3 December 1996) was a French historian who specialised in the social and economic history of the Middle Ages. He ranks among the most influential medieval historians of the twentieth century and was one of Fran ...

, in his complaint:

Through all that has been said, we can see how interesting it would be to measure the influence of technical progress on agricultural output. Nevertheless, we must renounce this hope. Before the end of the 12th century, the methods of seignorial administration were all quite primitive; they granted little importance to writing and even less to numbers. The documents are more deceptive than those of theNowadays, numerous elements of traditional agriculture are being lost, and because of this various entities have been working to conserve or recover this cultural capital. Among these is an international interdisciplinary project called E.A.R.T.H., Early Agricultural Remnants and Technical Heritage. Participating countries includeCarolingian era The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large Frankish-dominated empire in western and central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the Lo ....

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

. Investigations center on broad archeological, documentary and ethnological aspects, related to diverse elements of traditional agriculture, threshing boards among them, in diverse countries, historical periods and societies.

Kish

Kish may refer to:

Geography

* Gishi, Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan, a village also called Kish

* Kiş, Shaki, Azerbaijan, a village and municipality also spelled Kish

* Kish Island, an Iranian island and a city in the Persian Gulf

* Kish, Iran, ...

at:-3374 align:left fontsize:S text:Arslantepe

Melid, also known as Arslantepe, was an ancient city on the Tohma River, a tributary of the upper Euphrates rising in the Taurus Mountains. It has been identified with the modern archaeological site of Arslantepe near Malatya, Turkey.

It was ...

from:-2700 till:-2400 align:center fontsize:S text:Puabi

Puabi (Akkadian language, Akkadian: 𒅤𒀀𒉿 ''Pu-A-Bi'' "Word of my father"), also called Shubad or Shudi-Ad due to a misinterpretation by Sir Charles Leonard Woolley, was an important woman in the Sumerian city of Ur, during the First Dyn ...

at:-1150 align:right fontsize:S text:Deuteronomy

Deuteronomy ( grc, Δευτερονόμιον, Deuteronómion, second law) is the fifth and last book of the Torah (in Judaism), where it is called (Hebrew: hbo, , Dəḇārīm, hewords Moses.html"_;"title="f_Moses">f_Moseslabel=none)_and_th ...

from:-1005 till:-965 align:center fontsize:S text:David

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

at:-810 align:left fontsize:S text:Isaiah

Isaiah ( or ; he, , ''Yəšaʿyāhū'', "God is Salvation"), also known as Isaias, was the 8th-century BC Israelite prophet after whom the Book of Isaiah is named.

Within the text of the Book of Isaiah, Isaiah himself is referred to as "the ...

from:-234 till:79 align:center fontsize:S text:Latin texts

at:1200 align:center fontsize:S text:Medieval

at:1850 align:center fontsize:S text:Cantalejo

Cantalejo is a municipality located in the Segovia (province), province of Segovia, Castile and León, Spain. According to the 2004 census (Instituto Nacional de Estadística (Spain), INE), the municipality had a population of 3,622 inhabitants. ...

Craftsmen from Cantalejo

Cantalejo

Cantalejo is a municipality located in the Segovia (province), province of Segovia, Castile and León, Spain. According to the 2004 census (Instituto Nacional de Estadística (Spain), INE), the municipality had a population of 3,622 inhabitants. ...

is located at the confluence of the Duraton River and the Cega River. Modern Cantalejo arose in the 11th century, although there are architectural remains that are much older, and forms part of Segovia

Segovia ( , , ) is a city in the autonomous community of Castile and León, Spain. It is the capital and most populated municipality of the Province of Segovia.

Segovia is in the Inner Plateau ('' Meseta central''), near the northern slopes of t ...

province in Spain. It was apparently prosperous at the beginning but, lost its liberty in the 17th Century and became a jurisdictional lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power (social and political), power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the Peerage ...

ship. There is no clear record of when the specialized craft of making threshing boards was introduced into Cantalejo, but all who have written on the topic indicate that it was probably during the 16th or 17th century.

The production of threshing boards appears to coincide with the arrival of foreign artisans, although this is speculation based on the fact that the artisans' form of speech (see the section on ) includes aspects of many foreign languages, especially French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

. The makers of threshing boards and plows were called ''«Briqueros»'', a word of French origin that refers to the making of tinderbox

A tinderbox, or patch box, is a container made of wood or metal containing flint, firesteel, and tinder (typically charcloth, but possibly a small quantity of dry, finely divided fibrous matter such as hemp), used together to help kindle a fire ...

es and matchlock

A matchlock or firelock is a historical type of firearm wherein the gunpowder is ignited by a burning piece of rope that is touched to the gunpowder by a mechanism that the musketeer activates by pulling a lever or trigger with his finger. Befor ...

s for guns, which in France were called '' briquets'', literally in archaic French: ''«Petite pièce d’acier don't on se sert pour tirer du feu d’un caillou.»'' (today, synonym of briquette

A briquette (; also spelled briquet) is a compressed block of coal dust or other combustible biomass material (e.g. charcoal, sawdust, wood chips, peat, or paper) used for fuel and kindling to start a fire. The term derives from the French word ' ...

or flammable matter, but also refers to a lighter

A lighter is a portable device which creates a flame, and can be used to ignite a variety of items, such as cigarettes, gas lighter, fireworks, candles or campfires. It consists of a metal or plastic container filled with a flammable liquid or ...

) for the early firearms

Early may refer to:

History

* The beginning or oldest part of a defined historical period, as opposed to middle or late periods, e.g.:

** Early Christianity

** Early modern Europe

Places in the United States

* Early, Iowa

* Early, Texas

* Early ...

(Flintlock

Flintlock is a general term for any firearm that uses a flint-striking ignition mechanism, the first of which appeared in Western Europe in the early 16th century. The term may also apply to a particular form of the mechanism itself, also know ...

s, arquebus

An arquebus ( ) is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

Although the term ''arquebus'', derived from the Dutch word ''Haakbus ...

es, musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually di ...

s...). It is therefore plausible that foreign gunsmiths introducing firearms in the Iberian Peninsula created an important colony in Cantalejo, although it is difficult to determine their origin

In any case, with time Cantalejo opted for peaceful and productive crafts such as the making of diverse agricultural implements, including threshing boards. By the 1950s, Cantalejo had reached 400 workshops producing more than 30,000 threshing boards each year; this suggests that more than half the population was dedicated to this occupation. The threshing boards were then distributed throughout the entire Meseta Central

The ''Meseta Central'' (, sometimes referred to in English as Inner Plateau) is one of the basic geographical units of the Iberian Peninsula. It consists of a plateau covering a large part of the latter's interior.

Developed during the 19th cent ...

of Spain.