Thorny-headed Worm on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Acanthocephala (

There are several morphological characteristics that distinguish acanthocephalans from other phyla of parasitic worms.

There are several morphological characteristics that distinguish acanthocephalans from other phyla of parasitic worms.

Acanthocephalans have complex life cycles, involving a number of hosts, for both

Acanthocephalans have complex life cycles, involving a number of hosts, for both

Having been expelled by the female, the acanthocephalan egg is released along with the feces of the host. For development to occur, the egg, containing the acanthor, needs to be ingested by an

Having been expelled by the female, the acanthocephalan egg is released along with the feces of the host. For development to occur, the egg, containing the acanthor, needs to be ingested by an

* * * Carl Zimmer, Zimmer, C. '' Parasite Rex: Inside the Bizarre World of Nature's Most Dangerous Creatures'' 92. .

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, ', thorn + , ', head) is a phylum

In biology, a phylum (; plural: phyla) is a level of classification or taxonomic rank below kingdom and above class. Traditionally, in botany the term division has been used instead of phylum, although the International Code of Nomenclature ...

of parasitic

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson ha ...

worm

Worms are many different distantly related bilateral animals that typically have a long cylindrical tube-like body, no limbs, and no eyes (though not always).

Worms vary in size from microscopic to over in length for marine polychaete wor ...

s known as acanthocephalans, thorny-headed worms, or spiny-headed worms, characterized by the presence of an eversible proboscis

A proboscis () is an elongated appendage from the head of an animal, either a vertebrate or an invertebrate. In invertebrates, the term usually refers to tubular mouthparts used for feeding and sucking. In vertebrates, a proboscis is an elong ...

, armed with spines, which it uses to pierce and hold the gut wall of its host. Acanthocephalans have complex life cycles, involving at least two hosts, which may include invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chorda ...

s, fish, amphibian

Amphibians are four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terrestrial, fossorial, arbo ...

s, birds, and mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur ...

s. About 1420 species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriat ...

have been described.

The Acanthocephala were thought to be a discrete phylum

In biology, a phylum (; plural: phyla) is a level of classification or taxonomic rank below kingdom and above class. Traditionally, in botany the term division has been used instead of phylum, although the International Code of Nomenclature ...

. Recent genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ...

analysis has shown that they are descended from, and should be considered as, highly modified rotifer

The rotifers (, from the Latin , "wheel", and , "bearing"), commonly called wheel animals or wheel animalcules, make up a phylum (Rotifera ) of microscopic and near-microscopic pseudocoelomate animals.

They were first described by Rev. John H ...

s. This unified taxon is known as Syndermata

Syndermata is a clade of animals that, in some systems, is considered synonymous with Rotifera. Older systems separate Rotifera and Acanthocephala

Acanthocephala (Greek , ', thorn + , ', head) is a phylum of parasitic worms known as acant ...

.

History

The earliest recognisable description of Acanthocephala – a worm with a proboscis armed with hooks – was made by Italian authorFrancesco Redi

Francesco Redi (18 February 1626 – 1 March 1697) was an Italian physician, naturalist, biologist, and poet. He is referred to as the "founder of experimental biology", and as the "father of modern parasitology". He was the first person to ch ...

(1684).Crompton 1985, p. 27 In 1771, Joseph Koelreuter proposed the name Acanthocephala. Philipp Ludwig Statius Müller

Philipp Ludwig Statius Müller (25 April 1725 – 5 January 1776) was a German zoologist.

Statius Müller was born in Esens, and was a professor of natural science at Erlangen. Between 1773 and 1776, he published a German translation of Linn ...

independently called them ''Echinorhynchus'' in 1776. Karl Rudolphi

Karl Asmund Rudolphi (14 July 1771 – 29 November 1832) was a Swedish-born German naturalist, who is credited with being the "father of helminthology".

Life

Rudolphi was born in Stockholm to German parents. He was awarded his PhD in 1793 an ...

in 1809 formally named them Acanthocephala.

Evolutionary history

The oldest known remains of acanthocephalans are eggs found in acoprolite

A coprolite (also known as a coprolith) is fossilized feces. Coprolites are classified as trace fossils as opposed to body fossils, as they give evidence for the animal's behaviour (in this case, diet) rather than morphology. The name is ...

from the Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the younger of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''creta'', ...

Bauru Group

The Bauru Group is a geological group of the Bauru Sub-basin, Paraná Basin in Minas Gerais, São Paulo, General Salgado, Itapecuru-Mirim, Mato Grosso, Brazil whose strata date back to the Late Cretaceous. Dinosaur remains are among the fossils ...

of Brazil, around 70-80 million years old, likely from a crocodyliform

Crocodyliformes is a clade of crurotarsan archosaurs, the group often traditionally referred to as "crocodilians". They are the first members of Crocodylomorpha to possess many of the features that define later relatives. They are the only pseu ...

. The group may have originated substantially earlier.

Phylogeny

Acanthocephalans are highly adapted to a parasitic mode of life, and have lost many organs and structures through evolutionary processes. This makes determining relationships with other higher taxa through morphological comparison problematic.Phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups ...

analysis of the 18S ribosomal

Ribosomes ( ) are macromolecular machines, found within all cells, that perform biological protein synthesis (mRNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules to for ...

gene has revealed that the Acanthocephala are most closely related to the rotifer

The rotifers (, from the Latin , "wheel", and , "bearing"), commonly called wheel animals or wheel animalcules, make up a phylum (Rotifera ) of microscopic and near-microscopic pseudocoelomate animals.

They were first described by Rev. John H ...

s. They are possibly closer to the two rotifer classes Bdelloidea

Bdelloidea ( Greek ''βδέλλα'', ''bdella'', "leech") is a class of rotifers found in freshwater habitats all over the world. There are over 450 described species of bdelloid rotifers (or 'bdelloids'), distinguished from each other main ...

and Monogononta than to the other class, Seisonidea, producing the names and relationships shown in the cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to ...

below.The three rotifer classes and the Acanthocephala make up a clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English ter ...

called Syndermata. This clade is placed in the Platyzoa

The paraphyletic "Platyzoa" are a group of protostome unsegmented animals proposed by Thomas Cavalier-Smith in 1998. Cavalier-Smith included in Platyzoa the phylum Platyhelminthes (or flatworms), and a new phylum, the Acanthognatha, into which ...

.

A study of the gene order in the mitochondria suggests that Seisonidea and Acanthocephala are sister clades and that the Bdelloidea are the sister clade to this group.

Currently the phylum is divided into four classes – Palaeacanthocephala

Palaeacanthocephala ("ancient thornheads") is a class within the phylum Acanthocephala. The adults of these parasitic platyzoans feed mainly on fish, aquatic birds and mammals. This order is characterized by the presence of lateral longitudinal ...

, Archiacanthocephala

Archiacanthocephala is a class within the phylum of Acanthocephala. They are parasitic worms that attach themselves to the intestinal wall of terrestrial vertebrates, including humans. They are characterised by the body wall and the lemnisci (wh ...

, Polyacanthocephala

Polyacanthorhynchidae is a family of parasitic worms from the (phylum Acanthocephala). It contains a single genus ''Polyacanthorhynchus''. Taxonomy

Phylogenetic analysis has found that polyacanthocephala represents a distinct class of acanthocep ...

and Eoacanthocephala

Eoacanthocephala is a class of parasitic worms, within the phylum Acanthocephala. They feed on any aquatic cold-blooded creature such as turtles and fish. Their proboscis spines are arranged radially, with no protonephridia, and with persistent ...

. The monophyletic Archiacanthocephala are the sister taxon of a clade comprising Eoacanthocephala and the monophyletic Palaeacanthocephala.

Morphology

There are several morphological characteristics that distinguish acanthocephalans from other phyla of parasitic worms.

There are several morphological characteristics that distinguish acanthocephalans from other phyla of parasitic worms.

Digestion

Acanthocephalans lack a mouth oralimentary canal

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans and ...

. This is a feature they share with the cestoda

Cestoda is a class of parasitic worms in the flatworm phylum (Platyhelminthes). Most of the species—and the best-known—are those in the subclass Eucestoda; they are ribbon-like worms as adults, known as tapeworms. Their bodies consist of ...

(tapeworms), although the two groups are not closely related. Adult stages live in the intestine

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans an ...

s of their host and uptake nutrients which have been digested by the host, directly, through their body surface. The acanthocephalans lack an excretory system, although some species have been shown to possess flame cells (protonephridia).

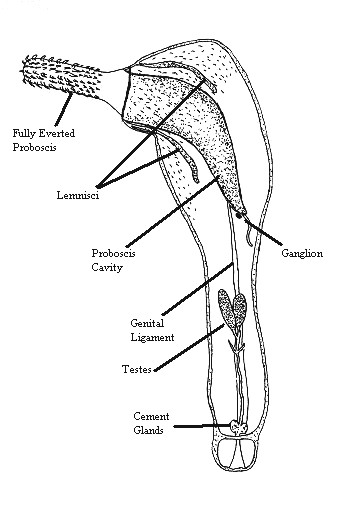

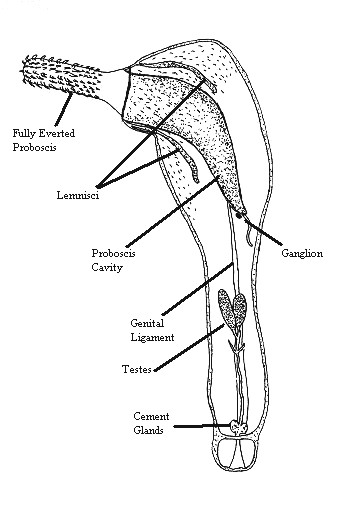

Proboscis

The most notable feature of the acanthocephala is the presence of ananterior

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek language, Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. Th ...

, protrudable proboscis

A proboscis () is an elongated appendage from the head of an animal, either a vertebrate or an invertebrate. In invertebrates, the term usually refers to tubular mouthparts used for feeding and sucking. In vertebrates, a proboscis is an elong ...

that is usually covered with spiny hooks (hence the common name: thorny or spiny headed worm). The proboscis bears rings of recurved hooks arranged in horizontal rows, and it is by means of these hooks that the animal attaches itself to the tissues of its host. The hooks may be of two or three shapes, usually: longer, more slender hooks are arranged along the length of the proboscis, with several rows of more sturdy, shorter nasal hooks around the base of the proboscis. The proboscis is used to pierce the gut wall of the final host, and hold the parasite fast while it completes its life cycle.

Like the body, the proboscis is hollow, and its cavity is separated from the body cavity by a ''septum'' or ''proboscis sheath''. Traversing the cavity of the proboscis are muscle

Skeletal muscles (commonly referred to as muscles) are organs of the vertebrate muscular system and typically are attached by tendons to bones of a skeleton. The muscle cells of skeletal muscles are much longer than in the other types of mus ...

-strands inserted into the tip of the proboscis at one end and into the septum at the other. Their contraction causes the proboscis to be invaginated into its cavity. The whole proboscis apparatus can also be, at least partially, withdrawn into the body cavity, and this is effected by two retractor muscles which run from the posterior aspect of the septum to the body wall.

Some of the acanthocephalans (perforating acanthocephalans) can insert their proboscis in the intestine of the host and open the way to the abdominal cavity.

Size

The size of these animals varies greatly, some are measured to be a few millimetres in length to '' Gigantorhynchus gigas'', which measures from . A curious feature shared by both larva and adult is the large size of many of the cells, e.g. the nerve cells and cells forming the uterine bell.Polyploid

Polyploidy is a condition in which the cells of an organism have more than one pair of ( homologous) chromosomes. Most species whose cells have nuclei ( eukaryotes) are diploid, meaning they have two sets of chromosomes, where each set conta ...

y is common, with up to 343n having been recorded in some species.

Skin

The body surface of the acanthocephala is peculiar. Externally, the skin has a thin tegument covering theepidermis

The epidermis is the outermost of the three layers that comprise the skin, the inner layers being the dermis and hypodermis. The epidermis layer provides a barrier to infection from environmental pathogens and regulates the amount of water rel ...

, which consists of a syncytium

A syncytium (; plural syncytia; from Greek: σύν ''syn'' "together" and κύτος ''kytos'' "box, i.e. cell") or symplasm is a multinucleate cell which can result from multiple cell fusions of uninuclear cells (i.e., cells with a single nucleu ...

with no cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer surrounding some types of cells, just outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. It provides the cell with both structural support and protection, and also acts as a filtering mec ...

s. The syncytium is traversed by a series of branching tubule

In biology, a tubule is a general term referring to small tube or similar type of structure. Specifically, tubule can refer to:

* a small tube or fistular structure

* a minute tube lined with glandular epithelium

* any hollow cylindrical body stru ...

s containing fluid and is controlled by a few wandering, amoeboid

An amoeba (; less commonly spelled ameba or amœba; plural ''am(o)ebas'' or ''am(o)ebae'' ), often called an amoeboid, is a type of cell or unicellular organism with the ability to alter its shape, primarily by extending and retracting pseudopo ...

nuclei. Inside the syncytium is an irregular layer of circular muscle fibres, and within this again some rather scattered longitudinal fibres; there is no endothelium

The endothelium is a single layer of squamous endothelial cells that line the interior surface of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. The endothelium forms an interface between circulating blood or lymph in the lumen and the rest of the ve ...

. In their micro-structure the muscular fibres resemble those of nematode

The nematodes ( or grc-gre, Νηματώδη; la, Nematoda) or roundworms constitute the phylum Nematoda (also called Nemathelminthes), with plant- parasitic nematodes also known as eelworms. They are a diverse animal phylum inhabiting a bro ...

s.

Except for the absence of the longitudinal fibres the skin of the proboscis resembles that of the body, but the fluid-containing tubules of the proboscis are shut off from those of the body. The canals of the proboscis open into a circular vessel which runs round its base. From the circular canal two sac-like projections called the ''lemnisci'' run into the cavity of the body, alongside the proboscis cavity. Each consists of a prolongation of the syncytial material of the proboscis skin, penetrated by canals and sheathed with a muscular coat. They seem to act as reservoirs into which the fluid which is used to keep the proboscis "erect" can withdraw when it is retracted, and from which the fluid can be driven out when it is wished to expand the proboscis.

Nervous system

The central ganglion of the nervous system lies behind the proboscis sheath or septum. It innervates the proboscis and projects two stout trunks posteriorly which supply the body. Each of these trunks is surrounded by muscles, and this nerve-muscle complex is called a ''retinaculum''. In the male at least there is also agenital

A sex organ (or reproductive organ) is any part of an animal or plant that is involved in sexual reproduction. The reproductive organs together constitute the reproductive system. In animals, the testis in the male, and the ovary in the female, a ...

ganglion

A ganglion is a group of neuron cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system. In the somatic nervous system this includes dorsal root ganglia and trigeminal ganglia among a few others. In the autonomic nervous system there are both sympathe ...

. Some scattered papillae may possibly be sense-organs.

Life cycles

Acanthocephalans have complex life cycles, involving a number of hosts, for both

Acanthocephalans have complex life cycles, involving a number of hosts, for both developmental

Development of the human body is the process of growth to maturity. The process begins with fertilization, where an egg released from the ovary of a female is penetrated by a sperm cell from a male. The resulting zygote develops through mitosi ...

and resting stages. Complete life cycles have been worked out for only 25 species.

Reproduction

The Acanthocephala aredioecious

Dioecy (; ; adj. dioecious , ) is a characteristic of a species, meaning that it has distinct individual organisms (unisexual) that produce male or female gametes, either directly (in animals) or indirectly (in seed plants). Dioecious reproducti ...

(an individual organism is either male or female). There is a structure called the ''genital ligament'' which runs from the posterior end of the proboscis sheath to the posterior end of the body. In the male, two testes

A testicle or testis (plural testes) is the male reproductive gland or gonad in all bilaterians, including humans. It is homologous to the female ovary. The functions of the testes are to produce both sperm and androgens, primarily testoste ...

lie on either side of this. Each opens in a vas deferens

The vas deferens or ductus deferens is part of the male reproductive system of many vertebrates. The ducts transport sperm from the epididymis to the ejaculatory ducts in anticipation of ejaculation. The vas deferens is a partially coiled tube ...

which bears three diverticula

In medicine or biology, a diverticulum is an outpouching of a hollow (or a fluid-filled) structure in the body. Depending upon which layers of the structure are involved, diverticula are described as being either true or false.

In medicine, t ...

or ''vesiculae seminales''. The male also possesses three pairs of cement glands, found behind the testes, which pour their secretions through a duct into the vasa deferentia. These unite and end in a penis

A penis (plural ''penises'' or ''penes'' () is the primary sexual organ that male animals use to inseminate females (or hermaphrodites) during copulation. Such organs occur in many animals, both vertebrate and invertebrate, but males d ...

which opens posteriorly.

In the female, the ovaries

The ovary is an organ in the female reproductive system that produces an ovum. When released, this travels down the fallopian tube into the uterus, where it may become fertilized by a sperm. There is an ovary () found on each side of the body. T ...

are found, like the testes, as rounded bodies along the ligament. From the ovaries, masses of ova dehisce into the body cavity, floating in its fluids for fertilization

Fertilisation or fertilization (see spelling differences), also known as generative fertilisation, syngamy and impregnation, is the fusion of gametes to give rise to a new individual organism or offspring and initiate its development. Pro ...

by male's sperm. After fertilization, each egg contains a developing embryo

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male spe ...

. (These embryos hatch into first stage larva

A larva (; plural larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

...

.) The fertilized eggs are brought into the uterus

The uterus (from Latin ''uterus'', plural ''uteri'') or womb () is the organ in the reproductive system of most female mammals, including humans that accommodates the embryonic and fetal development of one or more embryos until birth. The ...

by actions of the ''uterine bell'', a funnel like opening continuous with the uterus. At the junction of the bell and the uterus there is a second, smaller opening situated dorsally

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position prov ...

. The bell "swallows" the matured eggs and passes them on into the uterus. (Immature embryos are passed back into the body cavity through the dorsal opening.) From the uterus, mature eggs leave the female's body via her oviduct

The oviduct in mammals, is the passageway from an ovary. In human females this is more usually known as the Fallopian tube or uterine tube. The eggs travel along the oviduct. These eggs will either be fertilized by spermatozoa to become a zygote, o ...

, pass into the host's alimentary canal and are expelled from the host's body within feces

Feces ( or faeces), known colloquially and in slang as poo and poop, are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the large intestine. Feces contain a rela ...

.

Release

Having been expelled by the female, the acanthocephalan egg is released along with the feces of the host. For development to occur, the egg, containing the acanthor, needs to be ingested by an

Having been expelled by the female, the acanthocephalan egg is released along with the feces of the host. For development to occur, the egg, containing the acanthor, needs to be ingested by an arthropod

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and cuticle made of chiti ...

, usually a crustacean

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapoda, decapods, ostracoda, seed shrimp, branchiopoda, branchiopods, argulidae, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopoda, isopods, barnacles, copepods, ...

(there is one known life cycle which uses a mollusc

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is est ...

as a first intermediate host). Inside the intermediate host, the acanthor is released from the egg and develops into an acanthella. It then penetrates the gut wall, moves into the body cavity, encysts, and begins transformation into the infective cystacanth stage. This form has all the organs of the adult save the reproductive ones.

The parasite is released when the first intermediate host is ingested. This can be by a suitable final host, in which case the cystacanth develops into a mature adult, or by a paratenic

In biology and medicine, a host is a larger organism that harbours a smaller organism; whether a parasitic, a mutualistic, or a commensalist ''guest'' ( symbiont). The guest is typically provided with nourishment and shelter. Examples include ...

host, in which the parasite again forms a cyst. When consumed by a suitable final host, the cycstacant ''excysts'', everts its proboscis and pierces the gut wall. It then feeds, grows and develops its sexual organs. Adult worms then mate. The male uses the excretions of its ''cement glands'' to plug the vagina

In mammals, the vagina is the elastic, muscular part of the female genital tract. In humans, it extends from the vestibule to the cervix. The outer vaginal opening is normally partly covered by a thin layer of mucosal tissue called the hymen ...

of the female, preventing subsequent matings from occurring. Embryos develop inside the female, and the life cycle repeats.

Host control

Thorny-headed worms begin their life cycle inside invertebrates that reside in marine or freshwater systems. '' Gammarus lacustris'', a small crustacean that inhabits ponds and rivers, is one invertebrate that the thorny-headed worm may occupy. In recent years the occurrence of infections from these parasites have been increases in Asian aquaculture practices. This crustacean is preyed on by ducks and hides by avoiding light and staying away from the surface. However, when infected by a thorny-headed worm it becomes attracted toward light and swims to the surface. ''Gammarus lacustris'' will even go so far as to find a rock or a plant on the surface, clamp its mouth down, and latch on, making it easy prey for the duck. The duck is the definitive host for the acanthocephalan parasite. In order to be transmitted to the duck, the parasite's intermediate host (the gammarid) must be eaten by the duck. This modification of gammarid behavior by the acanthocephalan is thought to increase the rate of transmission of the parasite to its next host by increasing the susceptibility of the gammarid to predation. It is thought that when ''Gammarus lacustris'' is infected with a thorny-headed worm, the parasite causesserotonin

Serotonin () or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) is a monoamine neurotransmitter. Its biological function is complex and multifaceted, modulating mood, cognition, reward, learning, memory, and numerous physiological processes such as vomiting and va ...

to be massively expressed. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter involved in emotions and mood. Researchers have found that during mating ''Gammarus lacustris'' expresses high levels of serotonin. Also during mating, the male ''Gammarus lacustris'' clamps down on the female and holds on for days. Researchers have additionally found that blocking serotonin releases clamping. Another experiment found that serotonin also reduces the photophobic behavior in ''Gammarus lacustris''. Thus, it is thought that the thorny-headed worm physiologically changes the behavior of the ''Gammarus lacustris'' in order to enter the bird, its final host.

Examples of this behaviour include the '' Polymorphus'' spp. which are parasites of seabirds

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same envi ...

, particularly the eider duck

Eiders () are large seaducks in the genus ''Somateria''. The three extant species all breed in the cooler latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere.

The down feathers of eider ducks, and some other ducks and geese, are used to fill pillows and quil ...

(''Somateria mollissima''). Heavy infections of up to 750 parasites per bird are common, causing ulceration

An ulcer is a discontinuity or break in a bodily membrane that impedes normal function of the affected organ. According to Robbins's pathology, "ulcer is the breach of the continuity of skin, epithelium or mucous membrane caused by sloughing o ...

to the gut, disease and seasonal mortality. Recent research has suggested that there is no evidence of pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a g ...

icity of ''Polymorphus'' spp. to intermediate crab hosts. The cystacanth stage is long lived and probably remains infective throughout the life of the crab.

The life cycle of ''Polymorphus'' spp. normally occurs between sea ducks (e.g. eiders and scoter

The scoters are stocky seaducks in the genus ''Melanitta''. The drakes are mostly black and have swollen bills, the females are brown. They breed in the far north of Europe, Asia, and North America, and winter farther south in temperate zone ...

s) and small crabs. Infections found in commercial-sized lobster

Lobsters are a family (Nephropidae, synonym Homaridae) of marine crustaceans. They have long bodies with muscular tails and live in crevices or burrows on the sea floor. Three of their five pairs of legs have claws, including the first pair, ...

s in Canada were probably acquired from crabs that form an important dietary item of lobsters. Cystacanths occurring in lobsters can cause economic loss to fishermen. There are no known methods of prevention or control.

Human infections

There is no known evidence of human infection being a common occurrence. However, there are many anecdotal claims of Acanthocephala showing up in stool with the insidious appearance of “rolled up tomato skins”. The earliest known infection was found in a prehistoric man inUtah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to its ...

. This infection was dated to 1869 ± 160 BC. The species involved was thought to be '' Moniliformis clarki'' which is still common in the area. The first report of an isolate in historic times was by Lambl in 1859 when he isolated '' Macracanthorhynchus hirudinaceus'' from a child in Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

. Lindemann in 1865 reported that this organism was commonly isolated in Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

. The reason for this was discovered by Schneider in 1871 when he found that an intermediate host, the scarabaeid beetle grub, was commonly eaten raw. The first report of clinical symptoms was by Calandruccio who in 1888 while in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

infected himself by ingesting larvae. He reported gastrointestinal disturbances and shed eggs in two weeks. Subsequent natural infections have since been reported. Eight species have been isolated from humans to date. ''Moniliformis moniliformis

''Moniliformis moniliformis'' is a parasite of the Acanthocephala phylum in the family Moniliformidae. The adult worms are usually found in intestines of rodents or carnivores such as cats and dogs. The species can also infest humans, though th ...

'' is the most common isolate. Other isolates include '' Acanthocephalus bufonis'' and ''Corynosoma strumosum

''Corynosoma'' is a genus of parasitic worms belonging to the family Polymorphidae.

The genus has almost cosmopolitan distribution.

Species:

*'' Corynosoma alaskensis''

*'' Corynosoma australe''

*'' Corynosoma beaglense''

*'' Corynosoma bu ...

''.

See also

*Cestoda

Cestoda is a class of parasitic worms in the flatworm phylum (Platyhelminthes). Most of the species—and the best-known—are those in the subclass Eucestoda; they are ribbon-like worms as adults, known as tapeworms. Their bodies consist of ...

* Digenea

Digenea (Gr. ''Dis'' – double, ''Genos'' – race) is a class of trematodes in the Platyhelminthes phylum, consisting of parasitic flatworms (known as ''flukes'') with a syncytial tegument and, usually, two suckers, one ventral and one oral. ...

* Monogenea

Monogeneans are a group of ectoparasitic flatworms commonly found on the skin, gills, or fins of fish. They have a direct lifecycle and do not require an intermediate host. Adults are hermaphrodites, meaning they have both male and female repr ...

Notes

References

* *Crompton, David; William Thomasson; Nickol, Brent B. (1985.) ''Biology of the Acanthocephala'', Cambridge University Press. p. 27* * * Carl Zimmer, Zimmer, C. '' Parasite Rex: Inside the Bizarre World of Nature's Most Dangerous Creatures'' 92. .

External links

{{Authority control Animal phyla Veterinary parasitology Mind-altering parasites Suicide-inducing parasitism Taxa named by Joseph Gottlieb Kölreuter