sweating sickness on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sweating sickness, also known as the sweats, English sweating sickness, English sweat or ''sudor anglicus'' in Latin, was a mysterious and contagious disease that struck England and later continental Europe in a series of epidemics beginning in 1485. The last outbreak occurred in 1551, after which the disease apparently vanished. The onset of symptoms was sudden, with death often occurring within hours. Sweating sickness epidemics were unique compared with other disease outbreaks of the time: whereas other epidemics were typically urban and long-lasting, cases of sweating sickness spiked and receded very quickly, and heavily affected rural populations. Its cause remains unknown, although it has been suggested that an unknown species of

The ailment was not recorded from 1492 to 1502. It may have been the condition which afflicted Henry VII's son

The ailment was not recorded from 1492 to 1502. It may have been the condition which afflicted Henry VII's son

''Sweating Fever''

Jim Leavesley commemorates the 500th anniversary of the first outbreak – transcript of talk on ''Ockham's Razor'', ABC

"The Sweating Sickness Returns"

''Discover Magazine'', 1 June 1997 {{DEFAULTSORT:Sweating Sickness 1485 establishments in England 1551 disestablishments in England 15th-century epidemics 16th-century epidemics 1485 in Europe 1507 in Europe 1517 in Europe 1528 in Europe 1551 in Europe 1485 in England 1517 in England 1528 in England 1551 in England Ailments of unknown cause Retrospective diagnosis History of medicine Health disasters in the United Kingdom Disease outbreaks in England

hantavirus

''Orthohantavirus'' is a genus of single-stranded, enveloped, negative-sense RNA viruses in the family '' Hantaviridae'' within the order ''Bunyavirales''. Members of this genus may be called orthohantaviruses or simply hantaviruses.

Orthohantav ...

was responsible.

Signs and symptoms

John Caius was a physician in Shrewsbury in 1551, when an outbreak occurred, and he described the symptoms and signs of the disease in ''A Boke or Counseill Against the Disease Commonly Called the Sweate, or Sweatyng Sicknesse'' (1552), which is the main historical source of knowledge of the disease. It began very suddenly with a sense of apprehension, followed by cold shivers (sometimes very violent),dizziness

Dizziness is an imprecise term that can refer to a sense of disorientation in space, vertigo, or lightheadedness. It can also refer to disequilibrium or a non-specific feeling, such as giddiness or foolishness.

Dizziness is a common medical c ...

, headache

Headache is the symptom of pain in the face, head, or neck. It can occur as a migraine, tension-type headache, or cluster headache. There is an increased risk of depression in those with severe headaches.

Headaches can occur as a result ...

and severe pains in the neck, shoulders and limbs, with great exhaustion. The cold stage might last from half an hour to three hours, after which the hot and sweating stage began. The characteristic sweat broke out suddenly without any obvious cause. A sense of heat, headache, delirium

Delirium (also known as acute confusional state) is an organically caused decline from a previous baseline of mental function that develops over a short period of time, typically hours to days. Delirium is a syndrome encompassing disturbances ...

, rapid pulse and intense thirst accompanied the sweat. Palpitation and pain in the heart were frequent symptoms. No skin eruptions were noted by observers. In the final stages there was either general exhaustion and collapse or an irresistible urge to sleep, which Caius thought was fatal if the patient were permitted to give way to it. One attack did not produce immunity, and some people suffered several bouts before dying. The disease typically lasted through one full day before recovery or death took place. The disease tended to occur in summer and early autumn.

Thomas Forestier, a physician during the first outbreak, provided a written account of his own experiences with the sweating sickness in 1485. Forestier put great emphasis on the sudden breathlessness commonly associated with the final hours of sufferers. Forestier claimed in an account written for other physicians that "loathsome vapors" had congregated around the heart and lungs. His observations point towards a pulmonary component of the disease.

Transmission

Transmission mostly remains a mystery, with only a few pieces of evidence in writings. The illness seemed to target young men and favour the wealthy or powerful, earning itself nicknames such as "Stoop Gallant" or "Stoop Knave" (indicating the proud were forced to 'stoop' and relinquish their proud status). The large number of people in London to witness the coronation of Henry VII may have increased the spread of the disease.Cause

The cause is unknown. Commentators then and now have blamed the sewage, poor sanitation, and contaminated water supplies. The first confirmed outbreak was in August 1485 at the end of theWars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487), known at the time and for more than a century after as the Civil Wars, were a series of civil wars fought over control of the throne of England, English throne in the mid-to-late fifteenth century. These w ...

, leading to speculation that it may have been brought from France by French mercenaries. However, an earlier outbreak may have affected the city of York in June 1485, before Tudor's army landed, although records of that disease's symptoms are not adequate to be certain. Regardless, the ''Croyland Chronicle

Crowland (modern usage) or Croyland (medieval era name and the one still in ecclesiastical use; cf. la, Croilandia) is a town in the South Holland district of Lincolnshire, England. It is situated between Peterborough and Spalding. Crowland ...

'' mentions that Thomas Stanley, 1st Earl of Derby

Thomas Stanley, 1st Earl of Derby, KG (1435 – 29 July 1504) was an English nobleman. He was the stepfather of King Henry VII of England. He was the eldest son of Thomas Stanley, 1st Baron Stanley and Joan Goushill.

A landed magnate of imm ...

cited the sweating sickness as reason not to join Richard III

Richard III (2 October 145222 August 1485) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat and death at the Bat ...

's army prior to the Battle of Bosworth

The Battle of Bosworth or Bosworth Field was the last significant battle of the Wars of the Roses, the civil war between the houses of Lancaster and York that extended across England in the latter half of the 15th century. Fought on 22 Au ...

.

Relapsing fever, a disease spread by ticks and lice, has been proposed as a possible cause. It occurs most often during the summer months, as did the original sweating sickness. However, relapsing fever is marked by a prominent black scab at the site of the tick bite and a subsequent skin rash.

The suggestion of ergot poisoning was ruled out due to England having much less rye (the main cause of ergotism

Ergotism (pron. ) is the effect of long-term ergot poisoning, traditionally due to the ingestion of the alkaloids produced by the '' Claviceps purpurea'' fungus—from the Latin "club" or clavus "nail" and for "head", i.e. the purple club-he ...

) than the rest of Europe.

Researchers have noted symptoms overlap with hantavirus pulmonary syndrome and have proposed an unknown hantavirus

''Orthohantavirus'' is a genus of single-stranded, enveloped, negative-sense RNA viruses in the family '' Hantaviridae'' within the order ''Bunyavirales''. Members of this genus may be called orthohantaviruses or simply hantaviruses.

Orthohantav ...

as the cause. Hantavirus species are zoonotic diseases carried by bats, rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the order Rodentia (), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal species are rodents. They are n ...

s, and several insectivore

A robber fly eating a hoverfly

An insectivore is a carnivorous animal or plant that eats insects. An alternative term is entomophage, which can also refer to the human practice of eating insects.

The first vertebrate insectivores were ...

s. Sharing of similar trends (including seasonal occurrences, fluctuations multiple times a year, and occasional occurrences between major outbreaks) suggest the English sweating sickness may have been rodent borne. The epidemiology of hantavirus correlates with the trends of the English sweating sickness. Hantavirus infections generally do not strike infants, children, or the elderly, and mostly affect middle-aged adults. In contrast to most epidemics of the medieval ages, the English sweating sickness also predominantly affected the middle aged. A criticism of this hypothesis is that modern day hantaviruses, unlike the sweating sickness, do not randomly disappear and can be seen affecting isolated people. Another is that sweating sickness was thought to have been transmitted from human to human, whereas hantaviruses are rarely spread that way. However, infection via human contact has been suggested in hantavirus outbreaks in Argentina.

In 2004, microbiologist Edward McSweegan suggested the disease may have been an outbreak of anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium '' Bacillus anthracis''. It can occur in four forms: skin, lungs, intestinal, and injection. Symptom onset occurs between one day and more than two months after the infection is contracted. The s ...

poisoning. He hypothesized that the victims could have been infected with anthrax spores present in raw wool or infected animal carcasses, and suggested exhuming victims for testing.

Numerous attempts have been made to define the disease origin by molecular biology methods, but have so far failed due to a lack of DNA or RNA.

Epidemiology

Fifteenth century

Sweating sickness first came to the attention of physicians at the beginning of the reign of Henry VII, in 1485. It was frequently fatal; half the population perished in some areas. The Ricardian scholar John Ashdown-Hill conjectures thatRichard III

Richard III (2 October 145222 August 1485) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat and death at the Bat ...

fell victim the night before the Battle of Bosworth Field

The Battle of Bosworth or Bosworth Field was the last significant battle of the Wars of the Roses, the civil war between the houses of Lancaster and York that extended across England in the latter half of the 15th century. Fought on 22 Augu ...

and that this accounted for his sleepless night and excessive thirst in the early part of the battle. There is no definitive statement that the sickness was present in Henry Tudor's troops landing at Milford Haven

Milford Haven ( cy, Aberdaugleddau, meaning "mouth of the two Rivers Cleddau") is both a town and a community in Pembrokeshire, Wales. It is situated on the north side of the Milford Haven Waterway, an estuary forming a natural harbour that has ...

. The battle's victor Henry VII arrived in London on 28 August, and the disease broke out there on 19 September 1485; it had killed several thousand people by its conclusion in late October that year. Among those killed were two lord mayors, six aldermen, and three sheriffs.

Mass superstition and paranoia followed the new plague. The Battle of Bosworth Field ended the Wars of the Roses between the houses of Lancaster and York. Richard III, the final York king, was killed here and Henry VII was crowned. As chaos, grief, and anger spread, people searched for a culprit for the plague. English people started to believe it was sent by God to punish supporters of Henry VII.

The sickness was regarded as being quite distinct from the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

, the pestilential fever, or other epidemics previously known because of its extremely rapid and fatal course, and the sweating which gave it its name. It reached Ireland in 1492, when the ''Annals of Ulster

The ''Annals of Ulster'' ( ga, Annála Uladh) are annals of medieval Ireland. The entries span the years from 431 AD to 1540 AD. The entries up to 1489 AD were compiled in the late 15th century by the scribe Ruaidhrí Ó Luinín, ...

'' record the death of James Fleming, 7th Baron Slane

James Fleming (bef. 1442–1492) was an Irish nobleman, who sat as a member of the House of Lords in the Irish Parliament in 1491 and also served as High Sheriff of Meath.

James was the son of William Fleming, a younger son of the 2nd Baron, and ...

from the ''pláigh allais'' perspiring plague" newly come to Ireland. The '' Annals of Connacht'' also record this obituary, and the ''Annals of the Four Masters

The ''Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland'' ( ga, Annála Ríoghachta Éireann) or the ''Annals of the Four Masters'' (''Annála na gCeithre Máistrí'') are chronicles of medieval Irish history. The entries span from the Deluge, dated as 2,24 ...

'' record "an unusual plague in Meath" of 24 hours' duration; people recovered if they survived it beyond that 24-hour period. It did not attack infants or little children. English chronicler Richard Grafton mentioned the sweating sickness of 1485 in his work ''Grafton's Chronicle: or History of England''. He noted the common treatment of the disease was to go immediately to bed at the first sign of symptoms; there, the affected person was to remain absolutely still for the entire 24-hour period of the illness, abstaining from any solid food and limiting water intake.

Sixteenth century

The ailment was not recorded from 1492 to 1502. It may have been the condition which afflicted Henry VII's son

The ailment was not recorded from 1492 to 1502. It may have been the condition which afflicted Henry VII's son Arthur, Prince of Wales

Arthur, Prince of Wales (19/20 September 1486 – 2 April 1502), was the eldest son of King Henry VII of England and Elizabeth of York. He was Duke of Cornwall from birth, and he was created Prince of Wales and Earl of Chester in 1489. A ...

, and Arthur's wife, Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine, ; 16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536) was Queen of England as the first wife of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 11 June 1509 until their annulment on 23 May 1533. She was previously ...

, in March 1502; their illness was described as "a malign vapour which proceeded from the air". Researchers who opened Arthur's tomb in 2002 could not determine the exact cause of death. Catherine recovered, but Arthur died on 2 April 1502 in his home at Ludlow Castle, six months short of his sixteenth birthday.

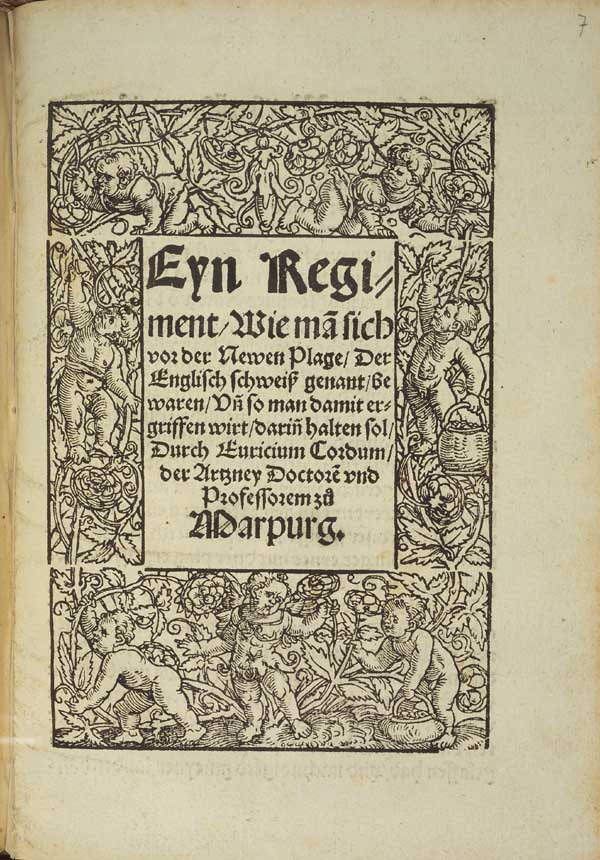

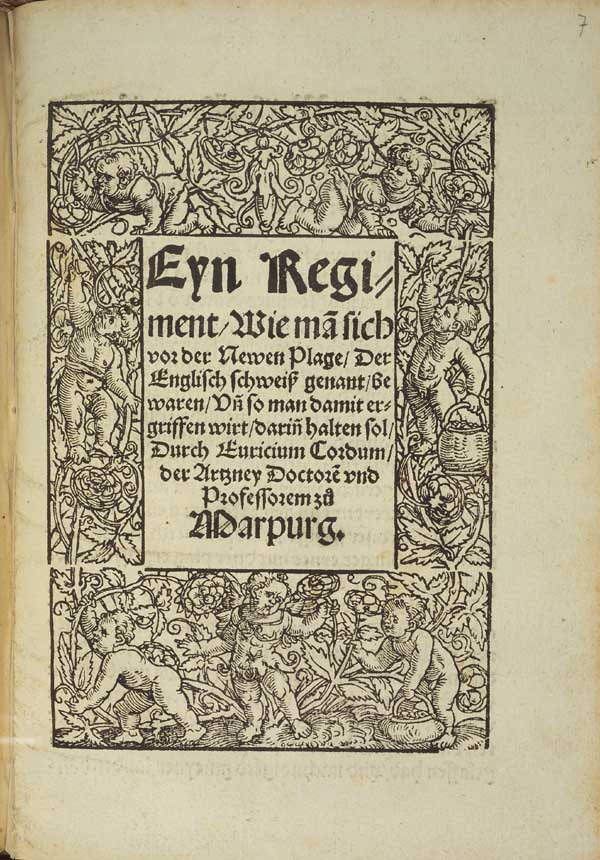

A second, less widespread outbreak occurred in 1507, followed by a third and much more severe epidemic in 1517, a few cases of which may have also spread to Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

. In the 1517 epidemic, the disease showed a particular affinity for the English; the ambassador from Venice at the time commented on the peculiarly low number of cases in foreign visitors. A similar effect was noted in 1528 when Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

(then an English territory) experienced an outbreak which did not spread into France. The 1528 outbreak, the fourth, reached epidemic proportions. It broke out in London at the end of May and spread over the whole of England, save the far north. It did not spread to Scotland, though it did reach Ireland where Lord Chancellor Hugh Inge

Hugh Inge or Ynge(c. 1460 – 3 August 1528) was an English-born judge and prelate in sixteenth century Ireland who held the offices of Bishop of Meath, Archbishop of Dublin and Lord Chancellor of Ireland.

Biography

Inge was born at Shepton Malle ...

was the most prominent victim. The mortality rate was very high in London; Henry VIII broke up the court and left London, frequently changing his residence. In 1529 Thomas Cromwell

Thomas Cromwell (; 1485 – 28 July 1540), briefly Earl of Essex, was an English lawyer and statesman who served as chief minister to King Henry VIII from 1534 to 1540, when he was beheaded on orders of the king, who later blamed false char ...

lost his wife and two daughters to the disease. It is believed several of the closest people to Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

contracted the sickness. His love letters to his mistress, Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn (; 1501 or 1507 – 19 May 1536) was Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and of her execution by beheading for treason and other charges made her a key f ...

, reveal that physicians believed Anne had contracted the illness. Henry sent his second-most trusted physician to her aid, his first being unavailable, and she survived. Cardinal Wolsey

Thomas Wolsey ( – 29 November 1530) was an English statesman and Catholic bishop. When Henry VIII became King of England in 1509, Wolsey became the king's almoner. Wolsey's affairs prospered and by 1514 he had become the controlling figur ...

contracted the illness and survived.

The disease suddenly appeared in Hamburg, spreading so rapidly that more than a thousand people died in a few weeks. It swept through eastern Europe causing high mortality rates. It arrived in Switzerland in December, then was carried northwards to Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, and eastwards to Lithuania, Poland, and Russia. Cases were unknown in Italy or France, except in the English-controlled Pale of Calais

The Pale of Calais was a territory in Northern France ruled by the monarchs of England for more than two hundred years from 1347 to 1558. The area, which was taken following the Battle of Crécy in 1346 and the subsequent siege of Calais, was ...

. It emerged in Flanders and the Netherlands, possibly transmitted directly from England by travellers; it appeared simultaneously in the cities of Antwerp and Amsterdam on the morning of 27 September. In each place, it prevailed for a short time, generally not more than two weeks. By the end of the year, it had entirely disappeared except in eastern Switzerland, where it lingered into the next year. The disease did not recur on mainland Europe.

Final outbreak

The last major outbreak of the disease occurred in England in 1551. Although burial patterns in smaller towns in Europe suggest that the disease may have been present elsewhere first, the outbreak is recorded to have begun in Shrewsbury in April. It killed around 1,000 there, spreading quickly throughout the rest of England and all but disappearing by October. It was more prevalent among younger men than other groups, possibly due to their greater social exposure. John Caius wrote his eyewitness account ''A Boke or Counseill Against the Disease Commonly Called the Sweate, or Sweatyng Sicknesse''. Henry Machin also recorded it in his diary: The ''Annals'' of Halifax Parish of 1551 records 44 deaths in an outbreak there. An outbreak called 'sweating sickness' occurred in Tiverton, Devon in 1644, recorded in Martin Dunsford's History, killing 443 people, 105 of them buried in October. However, no medical particulars were recorded, and the date falls well after the generally accepted disappearance of the 'sweating sickness' in 1551.Picardy sweat

Between 1718 and 1918 an illness with some similarities occurred in France, known as the Picardy sweat. It was significantly less lethal than the English Sweat but with a strikingly high frequency of outbreaks; some 200 were recorded during the period. Llywelyn Roberts noted "a great similarity between the two diseases." There was intense sweating and fever, and Henry Tidy found "no substantial reason to doubt the identity of ''sudor anglicus'' and Picardy sweat." There were also notable differences between the Picardy sweat and the English sweating sickness. It was accompanied by a rash, which was not described as a feature of the English disease. Henry Tidy argued that John Caius's report applies tofulminant

Fulminant () is a medical descriptor for any event or process that occurs suddenly and escalates quickly, and is intense and severe to the point of lethality, i.e., it has an explosive character. The word comes from Latin ''fulmināre'', to stri ...

cases fatal within a few hours, in which case no eruption may develop. The Picardy sweat appears to have had a different epidemiology than the English sweat in that individuals who slept close to the ground and/or lived on farms appeared more susceptible, supporting the theory that the disease could be rodent borne, common in hantaviruses. In a 1906 outbreak of Picardy sweat which struck 6,000 people a commission led by bacteriologist André Chantemesse attributed infection to the fleas of field mice.

Citations

Sources

* *Further reading

* * * * Flood, John L. "Englischer Schweiß und deutscher Fleiß. Ein Beitrag zur Buchhandelsgeschichte des 16. Jahrhunderts," in ''The German book in Wolfenbüttel and abroad. Studies presented to Ulrich Kopp in his retirement,'' ed. William A. Kelly & Jürgen Beyer tudies in reading and book culture 1(Tartu: University of Tartu Press, 2014), pp. 119–178. * *External links

''Sweating Fever''

Jim Leavesley commemorates the 500th anniversary of the first outbreak – transcript of talk on ''Ockham's Razor'', ABC

Radio National

Radio National, known on-air as RN, is an Australia-wide public service broadcasting radio network run by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). From 1947 until 1985, the network was known as ABC Radio 2.

History

1937: Predecessors a ...

"The Sweating Sickness Returns"

''Discover Magazine'', 1 June 1997 {{DEFAULTSORT:Sweating Sickness 1485 establishments in England 1551 disestablishments in England 15th-century epidemics 16th-century epidemics 1485 in Europe 1507 in Europe 1517 in Europe 1528 in Europe 1551 in Europe 1485 in England 1517 in England 1528 in England 1551 in England Ailments of unknown cause Retrospective diagnosis History of medicine Health disasters in the United Kingdom Disease outbreaks in England