Statue Of Marduk on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Statue of Marduk, also known as the Statue of Bêl ('' Bêl'', meaning "lord", being a common designation for

The Statue of Marduk, also known as the Statue of Bêl ('' Bêl'', meaning "lord", being a common designation for

The Statue of Marduk, also known as the Statue of Bêl ('' Bêl'', meaning "lord", being a common designation for

The Statue of Marduk, also known as the Statue of Bêl ('' Bêl'', meaning "lord", being a common designation for Marduk

Marduk (Cuneiform: dAMAR.UTU; Sumerian: ''amar utu.k'' "calf of the sun; solar calf"; ) was a god from ancient Mesopotamia and patron deity of the city of Babylon. When Babylon became the political center of the Euphrates valley in the time of ...

), was the physical representation of the god Marduk, the patron deity of the ancient city of Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

, traditionally housed in the city's main temple, the Esagila. There were seven statues of Marduk in Babylon, but 'the' Statue of Marduk generally refers to the god's main statue, placed prominently in the Esagila and used in the city's rituals. This statue was nicknamed the ''Asullḫi'' and was made of a type of wood called ''mēsu'' and covered with gold and silver.

Similar to statues of deities in other cities in Mesopotamia, the Babylonians conflated

Conflation is the merging of two or more sets of information, texts, ideas, opinions, etc., into one, often in error. Conflation is often misunderstood. It originally meant to fuse or blend, but has since come to mean the same as equate, treati ...

this statue with their actual god, believing that Marduk himself resided in their city through the statue. As such, the statue held enormous religious significance. It was used during the Babylonian New Year's festival and the kings of Babylon incorporated it into their coronation rituals, receiving the crown "from the hands" of Marduk.

Because of the enormous significance of the statue, it was sometimes used as a means of psychological warfare

Psychological warfare (PSYWAR), or the basic aspects of modern psychological operations (PsyOp), have been known by many other names or terms, including Military Information Support Operations (MISO), Psy Ops, political warfare, "Hearts and M ...

by Babylon's enemies. Enemy powers such as the Hittites

The Hittites () were an Anatolian people who played an important role in establishing first a kingdom in Kussara (before 1750 BC), then the Kanesh or Nesha kingdom (c. 1750–1650 BC), and next an empire centered on Hattusa in north-cent ...

, the Assyria

Assyria ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

ns and the Elamites stole the statue during sacks of the city, which caused religious and political turmoil, as Babylon's traditional rituals could then not be completed. All the foreign kings known to have stolen the statue ended up later being killed by their own family members, something the Babylonians hailed as divine punishment. Returns of the statue, either through the enemies giving it back or through a Babylonian king campaigning and successfully retrieving it, were occasions for great celebrations.

The ultimate fate of the statue is uncertain. A common assumption is that it was destroyed by the Achaemenid Persian king Xerxes I

Xerxes I ( peo, 𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ξέρξης ; – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, ruling from 486 to 465 BC. He was the son and successor of D ...

after a Babylonian uprising against his rule in 484 BC, but historical sources used for this assumption could be referring to a completely different statue. The statue's crown was restored by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

in 325 BC, meaning it was still in the Esagila at that time. There are a handful of references to later rulers giving gifts "to Marduk" in the Esagila, some from as late as during the time of Parthian rule in Mesopotamia in the 2nd century BC.

Background

Marduk

Marduk (Cuneiform: dAMAR.UTU; Sumerian: ''amar utu.k'' "calf of the sun; solar calf"; ) was a god from ancient Mesopotamia and patron deity of the city of Babylon. When Babylon became the political center of the Euphrates valley in the time of ...

was the patron deity of the city of Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

, having held this position since the reign of Hammurabi

Hammurabi (Akkadian: ; ) was the sixth Amorite king of the Old Babylonian Empire, reigning from to BC. He was preceded by his father, Sin-Muballit, who abdicated due to failing health. During his reign, he conquered Elam and the city-states ...

(18th century BC) in Babylon's first dynasty. Although Babylonian worship of Marduk never meant the denial of the existence of the other gods in the Mesopotamian pantheon

Deities in ancient Mesopotamia were almost exclusively anthropomorphic. They were thought to possess extraordinary powers and were often envisioned as being of tremendous physical size. The deities typically wore ''melam'', an ambiguous substan ...

, it has sometimes been compared to monotheism

Monotheism is the belief that there is only one deity, an all-supreme being that is universally referred to as God. Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxfo ...

. The history of worship of Marduk is intimately tied to the history of Babylon itself and as Babylon's power increased, so did the position of Marduk relative to that of other Mesopotamian gods. By the end of the second millennium BC, Marduk was sometimes just referred to as ''Bêl'', meaning "lord".

In Mesopotamian mythology

Mesopotamian mythology refers to the myths, religious texts, and other literature that comes from the region of ancient Mesopotamia which is a historical region of Western Asia, situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system that occupies ...

, Marduk was a creator god

A creator deity or creator god (often called the Creator) is a deity responsible for the creation of the Earth, world, and universe in human religion and mythology. In monotheism, the single God is often also the creator. A number of monolatri ...

. Going by the '' Enûma Eliš'', the Babylonian creation myth, Marduk was the son of Enki

, image = Enki(Ea).jpg

, caption = Detail of Enki from the Adda Seal, an ancient Akkadian cylinder seal dating to circa 2300 BC

, deity_of = God of creation, intelligence, crafts, water, seawater, lakewater, fertility, semen, magic, mischief

...

, the Mesopotamian god of wisdom, and rose to prominence during a great battle between the gods. The myth tells how the universe originated as a chaotic realm of water in which there originally were two primordial deities, Tiamat

In Mesopotamian religion, Tiamat ( akk, or , grc, Θαλάττη, Thaláttē) is a primordial goddess of the sea, mating with Abzû, the god of the groundwater, to produce younger gods. She is the symbol of the chaos of primordial crea ...

(salt water, female) and Abzu

The Abzu or Apsu ( Sumerian: ; Akkadian: ), also called (Cuneiform:, ; Sumerian: ; Akkadian: — ='water' ='deep', recorded in Greek as ), is the name for fresh water from underground aquifers which was given a religious fertilising qualit ...

(sweet water, male). These two gods gave birth to other deities. These deities (including gods such as Enki) had little to do in these early stages of existence and as such occupied themselves with various activities.

Eventually, their children began to annoy the elder gods and Abzu decided to rid himself of them by killing them. Alarmed by this, Tiamat revealed Abzu's plan to Enki, who killed his father before the plot could be enacted. Although Tiamat had revealed the plot to Enki to warn him, the death of Abzu horrified her and she too attempted to kill her children, raising an army together with her new consort Kingu

Kingu, also spelled Qingu (, ), was a god in Babylonian mythology, and the son of the gods Abzu and Tiamat. After the murder of his father, Abzu, he served as the consort of his mother, Tiamat, who wanted to establish him as ruler and leader of ...

. Every battle in the war was a victory for Tiamat, until Marduk convinced the other gods to proclaim him as their leader and king. The gods agreed, and Marduk was victorious, capturing and executing Kingu and firing a great arrow at Tiamat, killing her and splitting her in two.

With these chaotic primordial forces defeated, Marduk created the world and ordered the heavens. Marduk is also described as the creator of human beings, which were meant to help the gods in defeating and holding off the forces of chaos and thus maintain order on Earth.

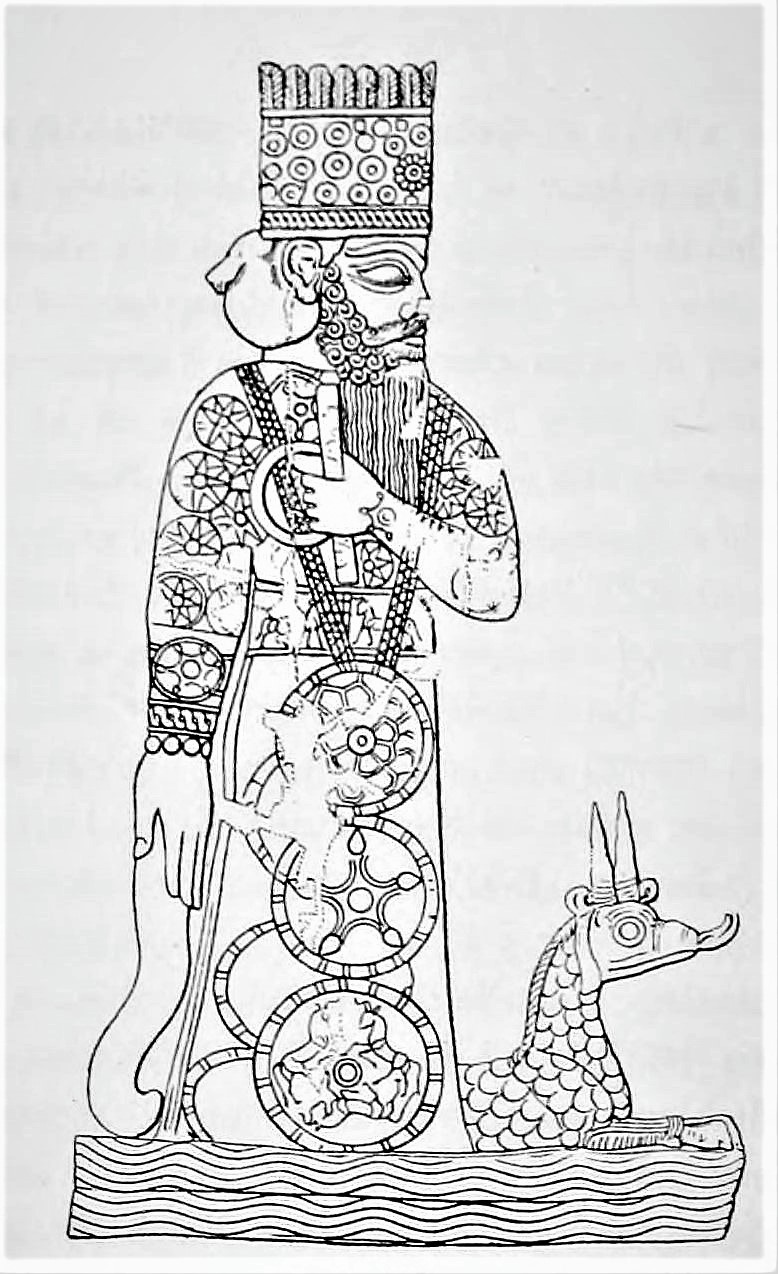

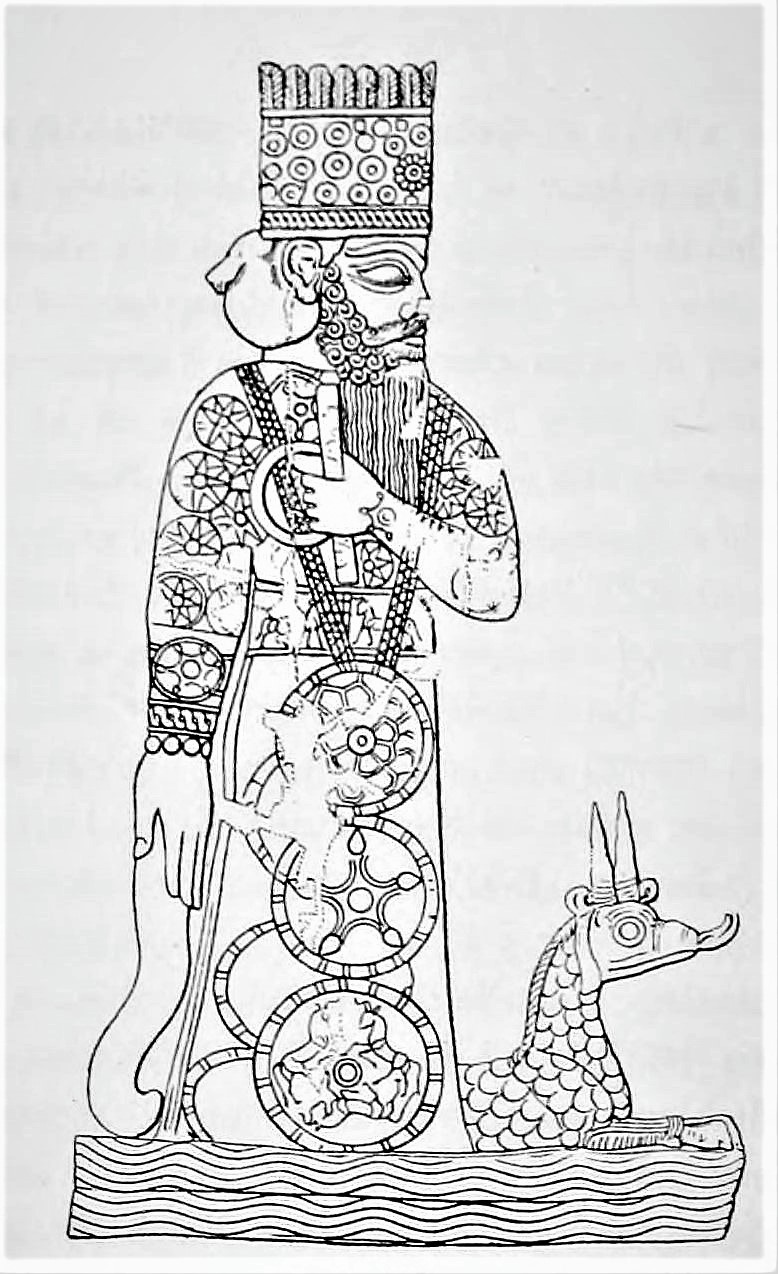

Appearance and other statues

The Statue of Marduk was the physical representation of Marduk housed in Babylon's main temple, the Esagila. Although there were actually seven separate statues of Marduk in Babylon: four in the Esagila and the surrounding temple complex; one in theEtemenanki

Etemenanki ( Sumerian: "temple of the foundation of heaven and earth") was a ziggurat dedicated to Marduk in the ancient city of Babylon. It now exists only in ruins, located about south of Baghdad, Iraq.

Etemenanki has been suggested to be ...

(the ziggurat

A ziggurat (; Cuneiform: 𒅆𒂍𒉪, Akkadian: ', D-stem of ' 'to protrude, to build high', cognate with other Semitic languages like Hebrew ''zaqar'' (זָקַר) 'protrude') is a type of massive structure built in ancient Mesopotamia. It has ...

dedicated to Marduk); and two in temples dedicated to other deities. 'The' statue of Marduk usually refers to Marduk's primary statue, placed prominently in the Esagila and used in the city's rituals.

This principal statue of Marduk was nicknamed the ''Asullḫi'' and made of a type of wood called ''mēsu''. The carved wooden statue would also have been covered in precious metals, such as gold and silver. In addition to this, the statue would have been provided with ritual clothing, at least partly made of gold. This statue would have occupied the cult room of Marduk in the Esagila, called the ''E-umuša''. Among the various statues of Marduk, the one called the ''Asullḫi'' is the only one explicitly mentioned in connection with the city's major rituals (though the statue is rarely named, often being referred to just as "Marduk" or "''Bêl''"). The name ''Asullḫi'' had centuries prior been associated with a separate deity of incantations later conflated

Conflation is the merging of two or more sets of information, texts, ideas, opinions, etc., into one, often in error. Conflation is often misunderstood. It originally meant to fuse or blend, but has since come to mean the same as equate, treati ...

with Marduk.

Another statue of Marduk, called the ''Asarre'', was made from a stone the Babylonians called ''marḫušu'', possibly chlorite

The chlorite ion, or chlorine dioxide anion, is the halite with the chemical formula of . A chlorite (compound) is a compound that contains this group, with chlorine in the oxidation state of +3. Chlorites are also known as salts of chlorou ...

or steatite

Soapstone (also known as steatite or soaprock) is a talc-schist, which is a type of metamorphic rock. It is composed largely of the magnesium rich mineral talc. It is produced by dynamothermal metamorphism and metasomatism, which occur in the ...

. The ''Asarre'' was located in a chapel dedicated to the god Ninurta

, image= Cropped Image of Carving Showing the Mesopotamian God Ninurta.png

, caption= Assyrian stone relief from the temple of Ninurta at Kalhu, showing the god with his thunderbolts pursuing Anzû, who has stolen the Tablet of Destinies from ...

off the north side of the Esagila's central courtyard. Though this chapel would have been dedicated to Ninurta, the Marduk statue would have occupied the central point of attention and thus have been the main figure. This might be explained through the god Ninurta becoming seen as simply an aspect of Marduk—an ancient visitor to the temple may not have been surprised to find Marduk in the stead of Ninurta. Other statues included one made of a type of wood called ''taskarinnu'' and placed in a chamber dedicated to the Enki (Marduk's father) in the E-kar-zaginna temple, part of the Esagila temple complex but not of the temple itself; an alabaster

Alabaster is a mineral or rock that is soft, often used for carving, and is processed for plaster powder. Archaeologists and the stone processing industry use the word differently from geologists. The former use it in a wider sense that include ...

statue in the "temple of E-namtila"; a statue of hematite

Hematite (), also spelled as haematite, is a common iron oxide compound with the formula, Fe2O3 and is widely found in rocks and soils. Hematite crystals belong to the rhombohedral lattice system which is designated the alpha polymorph of . ...

in the "chapel of Ninurta in the temple E-ḫursag-tilla"; and a statue of unknown material in "E-gišḫur-ankia, the temple of Bēlet-Ninua".

Role and importance

The citizens of the city of Babylon conflated the ''Asullḫi'' with the actual god Marduk—the god was understood as living in the temple, among the people of his city, and not in the heavens. As such, Marduk was not seen as some distant entity, but a friend and protector who lived nearby. This was no different from other Mesopotamian cities, who similarly conflated their gods with the representations used for them in their temples. During the religiously important 13-day long New Year's festival held annually in the spring at Babylon, the statue was removed from the temple and paraded through the city before being placed in a smaller building outside the city walls, where the statue received fresh air and could enjoy a different view from the one it had from inside the temple. The statue was traditionally incorporated into the coronation rituals for the Babylonian kings, who received their crowns "out of the hands" of Marduk during the New Year's festival, symbolizing them being bestowed with kingship by the patron deity of the city.' Both his rule and role as Marduk's vassal on Earth were reaffirmed annually at this time of year, when the king entered the Esagila alone on the fifth day of the festivities and met with the chief priest. The chief priest removed theregalia

Regalia is a Latin plurale tantum word that has different definitions. In one rare definition, it refers to the exclusive privileges of a sovereign. The word originally referred to the elaborate formal dress and dress accessories of a sovereig ...

from the king, slapped him across the face and made him kneel before Marduk's statue. The king would then tell the statue that he had not oppressed his people and that he had maintained order throughout the year, whereafter the chief priest would reply (on behalf of Marduk) that the king could continue to enjoy divine support for his rule and the regalia were returned.' The standard full Negative Confession of the king was the following:

Because of its significance to the city, Babylon's enemies often used the statue as a means of psychological warfare

Psychological warfare (PSYWAR), or the basic aspects of modern psychological operations (PsyOp), have been known by many other names or terms, including Military Information Support Operations (MISO), Psy Ops, political warfare, "Hearts and M ...

. When foreign powers conquered or plundered Babylon, the statue was often stolen from the city (a common way of weakening the power of defeated cities in ancient Mesopotamia). Such events caused great distress for the Babylonians, as the removal of the statue signified the actual departure of the real deity, their friend and protector. Without it, the New Year's festival could not be celebrated and religious activities were difficult to perform. The Babylonians believed that the statue's departures from the city were somewhat self-imposed, with the statue itself deciding to make the journey and foreign theft of it simply being a means to achieve that. The statue's absence meant confusion and hardship for the Babylonians, who believed that foreign lands benefited from having the statue as it brought prosperity wherever it went. The practice of taking the cult statues from enemies was viewed as capturing the enemy's source of divine power and suppressing that power.

Statues of deities were sometimes destroyed by enemy powers, as was once the case for the statue of the sun god Shamash

Utu (dUD " Sun"), also known under the Akkadian name Shamash, ''šmš'', syc, ܫܡܫܐ ''šemša'', he, שֶׁמֶשׁ ''šemeš'', ar, شمس ''šams'', Ashurian Aramaic: 𐣴𐣬𐣴 ''š'meš(ā)'' was the ancient Mesopotamian sun god ...

in that deity's patron city, Sippar

Sippar ( Sumerian: , Zimbir) was an ancient Near Eastern Sumerian and later Babylonian city on the east bank of the Euphrates river. Its '' tell'' is located at the site of modern Tell Abu Habbah near Yusufiyah in Iraq's Baghdad Governorate, som ...

. It was destroyed by the Suteans

The Suteans (Akkadian: ''Sutī’ū'', possibly from Amorite: ''Šetī’u'') were a Semitic people who lived throughout the Levant, Canaan and Mesopotamia during the Old Babylonian period. Unlike Amorites, they were not governed by a king. They ...

during the reign of Babylonian king Simbar-shipak

Simbar-Šipak, or perhaps ''Simbar-Šiḫu'',Earlier readings render his name as ''Simmash-Shipak''. typically inscribed m''sim-bar-''d''ši-i-''ḪU or ''si-im-bar-ši-''ḪU in cuneiform, where the reading of the last symbol is uncertain, “off ...

( 1026–1009 BC). As these statues held enormous religious significance, the statue of Shamash could not be replaced until almost two centuries later, under King Nabu-apla-iddina

Nabû-apla-iddina, inscribed md''Nábû-ápla-iddina''na''Synchronistic History'', tablet K4401a (ABC 21), iii 22–26. or md''Nábû-apla-íddina'';''Synchronistic Kinglist'' fragments VAT 11261 (KAV 10), ii 8, and Ass. 13956dh (KAV 182), iii 11. ...

( 887–855 BC) when a replica of the original was "divinely revealed" and the king ordered the new statue to be ritually dedicated. In the meantime, Sippar had prayed to its god using a sun-disc as a substitute for the statue. Though they were conflated into one, gods in Mesopotamia were believed to be able to "abandon" their statues. In an 8th-century BC religious text, the poor state of Marduk's statue inspired the god Erra to suggest that Marduk depart from the statue and that Erra could rule in his stead until the Babylonians had finished restoring it.

Gods could exist in heaven and on Earth simultaneously, and their presence on Earth could be in multiple places at the same time: for instance, Shamash and the goddess Ishtar

Inanna, also sux, 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒀭𒈾, nin-an-na, label=none is an ancient Mesopotamian goddess of love, war, and fertility. She is also associated with beauty, sex, divine justice, and political power. She was originally worshiped in Su ...

(a goddess of sex, war, justice and political power associated with the planet Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

) were manifested in cult images in many different cities and were also still seen as being present in their respective heavenly bodies. Though statues and other cult images could be harmed, this did not mean that actual damage was being done to the gods themselves.

History

Journeys of Marduk

The statue was first stolen from the city when KingMursili I

Mursili I (also known as Mursilis; sometimes transcribed as Murshili) was a king of the Hittites 1620-1590 BC, as per the middle chronology, the most accepted chronology in our times, (or alternatively c. 1556–1526 BC, short chronology), and wa ...

of the Hittites

The Hittites () were an Anatolian people who played an important role in establishing first a kingdom in Kussara (before 1750 BC), then the Kanesh or Nesha kingdom (c. 1750–1650 BC), and next an empire centered on Hattusa in north-cent ...

sacked Babylon 1595 BC. Mursili's war against Babylon ended the city's first dynasty and left its empire in ruins. Although Babylon rebuilt its kingdom under the Kassite dynasty

The Kassite dynasty, also known as the third Babylonian dynasty, was a line of kings of Kassite origin who ruled from the city of Babylon in the latter half of the second millennium BC and who belonged to the same family that ran the kingdom of ...

, the statue spent centuries in the kingdom of the Hittites, possibly being returned 1344 BC by King Šuppiluliuma I as a gesture of goodwill.

The statue then remained in Babylon until the Assyria

Assyria ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

n king Tukulti-Ninurta I captured Babylon in 1225 BC, when he plundered the city and carried the statue away to the Assyrian capital, Assur

Aššur (; Sumerian: AN.ŠAR2KI, Assyrian cuneiform: ''Aš-šurKI'', "City of God Aššur"; syr, ܐܫܘܪ ''Āšūr''; Old Persian ''Aθur'', fa, آشور: ''Āšūr''; he, אַשּׁוּר, ', ar, اشور), also known as Ashur and Qal'a ...

. What exactly happened thereafter is unclear, but it was returned and then later, for unknown reasons, moved to the nearby city Sippar

Sippar ( Sumerian: , Zimbir) was an ancient Near Eastern Sumerian and later Babylonian city on the east bank of the Euphrates river. Its '' tell'' is located at the site of modern Tell Abu Habbah near Yusufiyah in Iraq's Baghdad Governorate, som ...

. Sippar was sacked 1150 BC by the Elamites under their king, Shutruk-Nakhunte

Šutruk-Nakhunte was king of Elam from about 1184 to 1155 BC (middle chronology), and the second king of the Shutrukid Dynasty.

Elam amassed an empire that included most of Mesopotamia and western Iran.

Under his command, Elam defeated the K ...

, who stole the statue, carrying it to his homeland Elam. The statue was successfully seized and returned to Babylon after the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar I

Nebuchadnezzar I or Nebuchadrezzar I (), reigned 1121–1100 BC, was the fourth king of the Second Dynasty of Isin and Fourth Dynasty of Babylon. He ruled for 22 years according to the ''Babylonian King List C'', and was the most prominent monar ...

(1125–1104 BC) campaigned against the Elamites. Nebuchadnezzar's successful return of the statue to the city was a monumentous event and several literary works were created to commemorate it, possibly including an early version of the ''Enûma Eliš''.

The Neo-Assyrian King Tiglath-Pileser III

Tiglath-Pileser III ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "my trust belongs to the son of Ešarra"), was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 745 BC to his death in 727. One of the most prominent and historically significant Assyrian kings, T ...

conquered Babylon in October 729 BC, after which the Neo-Assyrian monarchs proclaimed themselves as kings of Babylon in addition to already being kings of Assyria. As vengeance after a series of revolts, the Neo-Assyrian king Sennacherib

Sennacherib ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: or , meaning " Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Sargon II in 705BC to his own death in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynas ...

plundered and destroyed Babylon in 689 BC. Sennacherib had been seen as heretical by the Babylonians, as he hadn't gone through with the traditional coronation ritual (with the statue) when he had proclaimed himself as Babylon's king. Following the destruction of the city, Sennacherib stole the statue and it was kept at the town of Issete in the northeastern parts of Assyria. When Sennacherib was murdered by his sons Arda-Mulissu

Arda-Mulissu or Arda-Mulissi (Akkadian: ) "servant of Mullissu", also known as Urdu-Mullissi, Urad-Mullissu and Arad-Ninlil and known in Hebrew writings as Adrammelech ( he, ''ʾAḏrammeleḵ''), was an ancient Assyrian prince of the Sargonid ...

and Sharezer

Sennacherib (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: or , meaning " Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Sargon II in 705BC to his own death in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynasty ...

in 681 BC, the Babylonians saw it as Marduk's divine retribution. Sennacherib's successor as Assyrian king, Esarhaddon

Esarhaddon, also spelled Essarhaddon, Assarhaddon and Ashurhaddon ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , also , meaning " Ashur has given me a brother"; Biblical Hebrew: ''ʾĒsar-Ḥaddōn'') was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of hi ...

, rebuilt Babylon in the 670s BC, restoring the Esagila. Under Esarhaddon's guidance, a pedestal

A pedestal (from French ''piédestal'', Italian ''piedistallo'' 'foot of a stall') or plinth is a support at the bottom of a statue, vase, column, or certain altars. Smaller pedestals, especially if round in shape, may be called socles. In ...

in gold (intended to support the returned statue) was created in the Esagila. The statue was finally returned to the city during the coronation of Esarhaddon's successor as Babylonian king, Shamash-shum-ukin

Shamash-shum-ukin ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: or , meaning "Shamash has established the name"), was king of Babylon as a vassal of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 668 BC to his death in 648. Born into the Assyrian royal family, Shamash-shum-ukin was ...

, in the spring of 668 BC. It is possible that Sennacherib actually destroyed the original statue and the statue returned to Babylon in 668 BC was a replica; some of Sennacherib's inscriptions allude to smashing the statues of the gods in Babylon while others explicitly state that the Marduk statue was carried to Assyria.

Assyrian control of Babylon was ended with the successful revolt of Nabopolassar

Nabopolassar (Babylonian cuneiform: , meaning "Nabu, protect the son") was the founder and first king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling from his coronation as king of Babylon in 626 BC to his death in 605 BC. Though initially only aimed at res ...

in 626 BC, which established the Neo-Babylonian Empire

The Neo-Babylonian Empire or Second Babylonian Empire, historically known as the Chaldean Empire, was the last polity ruled by monarchs native to Mesopotamia. Beginning with the coronation of Nabopolassar as the King of Babylon in 626 BC and bei ...

. Nabopolassar's son and heir, Nebuchadnezzar II

Nebuchadnezzar II (Babylonian cuneiform: ''Nabû-kudurri-uṣur'', meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir"; Biblical Hebrew: ''Nəḇūḵaḏneʾṣṣar''), also spelled Nebuchadrezzar II, was the second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling ...

(605–562 BC) widened the streets of Babylon so that the parade of the statue through the city at the New Year's festival would be made easier. The Neo-Babylonian Empire was ended with the conquest of Babylon by Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia (; peo, 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 ), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, the first Persian empire. Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Under his rule, the empire embraced ...

of the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

in 539 BC. Cyrus showed respect for the city and the statue and his own inscriptions surrounding his conquest of the city explicitly state that Marduk was on his side in the war.

Though the statue was often used as a means of psychological warfare by removing it from the city, powerful foreign rulers who did so had a tendency to die at the hands of their own family members. Mursili I, Shutruk-Nakhunte, Tukulti-Ninurta I, Sennacherib and the later Xerxes I

Xerxes I ( peo, 𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ξέρξης ; – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, ruling from 486 to 465 BC. He was the son and successor of D ...

were all killed by members of their own families. Such deaths, as can be seen in the Babylonian reaction to Sennacherib's murder in particular, were hailed by the Babylonians as divine punishment.

Xerxes and Babylon

In 484 BC, during the reign of the Achaemenid king Xerxes I, Babylon produced two contemporary revolts against Achaemenid rule, the revolts being led by rebel leaders Bel-shimanni and Shamash-eriba. Prior to these revolts, Babylon had occupied a special position within the Achaemenid Empire, the Achaemenid kings had been titled as ''king of Babylon and king of the Lands'', perceiving Babylonia as a somewhat separate entity within their empire, united with their own kingdom in apersonal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interli ...

. Xerxes gradually dropped the previous royal title and divided the previously large Babylonian satrapy (accounting for most of the Neo-Babylonian Empire's territory) into smaller sub-units.'

Using texts written by classical authors, it is often assumed that Xerxes enacted a brutal vengeance on Babylon following the two revolts. According to ancient writers, Xerxes destroyed Babylon's fortifications and damaged the temples in the city.' The Esagila was allegedly exposed to great damage and Xerxes allegedly carried the statue of Marduk away from the city,' possibly bringing it to Iran and melting it down (classical authors held that the statue was entirely made of gold, which would have made melting it down possible).' Historian Amélie Kuhrt

Amélie Kuhrt FBA (23 September 1944 - 2 January 2023) was a British historian and specialist in the history of the ancient Near East.

She was educated at King's College London, University College London and SOAS.

Professor Emerita at University ...

considers it unlikely that Xerxes destroyed the temples, but believes that the story of him doing so may derive from an anti-Persian sentiment among the Babylonians.' The story of Xerxes melting the statue comes chiefly from the ancient Greek writer Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known fo ...

, who isn't otherwise considered entirely reliable and has been noted as being very anti-Persian. Joshua J. Mark, writing in the Ancient History Encyclopedia, believes that the account of Herodotus, a Persian king destroying the statue of the deity of a city he just razed, could be anti-Persian propaganda. Furthermore, it is doubtful if the statue was removed from Babylon at all.' In ''From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire'' (2002), Pierre Briant considered it possible that Xerxes did remove a statue from the city, but that this was the golden statue of a man rather than the statue of the god Marduk.' Though mentions of the statue are lacking compared to earlier periods, contemporary documents suggest that the Babylonian New Year's Festival continued in some form during the Persian period.' Because the change in rulership from the Babylonians themselves to the Persians and due to the replacement of the city's elite families by Xerxes following its revolt, it is possible that the festival's traditional rituals and events had changed considerably.' Although contemporary evidence for Xerxes's retribution against Babylon is missing,' later authors mention the damage he inflicted upon the city's temples. For instance, both the Roman historian Arrian

Arrian of Nicomedia (; Greek: ''Arrianos''; la, Lucius Flavius Arrianus; )

was a Greek historian, public servant, military commander and philosopher of the Roman period.

''The Anabasis of Alexander'' by Arrian is considered the best ...

and the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

describe how Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

restored some temples in the city which had been destroyed or damaged by Xerxes.'

Later mentions

Arrian and Diodorus Siculus do not mention the Statue of Marduk, sometimes interpreted as indicating that the statue was no longer in the Esagila by Alexander's time. However, the statue was demonstrably still present in the Esagila, since its crown is mentioned as having been restored by Alexander in 325 BC. The crown is described as being horned, horned crowns being an ancient Mesopotamian way to indicate divinity, conflicting with how the statue's crown is portrayed in ancient Babylonian depictions. Due to his efforts to respect local religious customs in Mesopotamia, American historian Oliver D. Hoover speculated in 2011 thatSeleucus I Nicator

Seleucus I Nicator (; ; grc-gre, Σέλευκος Νικάτωρ , ) was a Macedonian Greek general who was an officer and successor ( ''diadochus'') of Alexander the Great. Seleucus was the founder of the eponymous Seleucid Empire. In the po ...

(305–281 BC), the first king of the Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

, might have undergone a traditional Babylonian coronation ceremony during a New Year's Festival in Babylon, involving the statue. Several later rulers are referenced as giving gifts "to Marduk" in the Esagila. Seleucus I's son and successor, Antiochus I Soter, sacrificed to Marduk several times during his time as crown prince. A late reference comes from the period of Parthian rule in Mesopotamia, with the Characenean ruler Hyspaosines attested as giving gifts "to Marduk" in 127 BC.'

There are no known sources that mention the New Year's Festival as a contemporary event from the time of the Seleucids and onwards' and one of the last times the tradition is known to have been celebrated is 188 BC. During the festival of 188 BC, Antiochus III

Antiochus III the Great (; grc-gre, Ἀντίoχoς Μέγας ; c. 2413 July 187 BC) was a Greek Hellenistic king and the 6th ruler of the Seleucid Empire, reigning from 222 to 187 BC. He ruled over the region of Syria and large parts of the r ...

, great-grandson of Antiochus I, prominently partook and was given various valuables, including a golden crown and the royal robe of Nebuchadnezzar II, by Babylon's high priest at the Esagila. The statue was a known historical object as late as the time of Parthian rule beyond Hyspaosines's time, from which a ritual text describes its role in the New Year's festival, including how the ''Enûma Eliš'' was recited in front of it and how the ancient kings of Babylon were supposed to be ritually slapped during the festival.

References

Cited bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Cited web sources

* * * {{refend Babylonia Babylonian art and architecture Lost sculptures Mesopotamian religion Mythological objects Sculptures of gods