Segregation in the United States on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In the

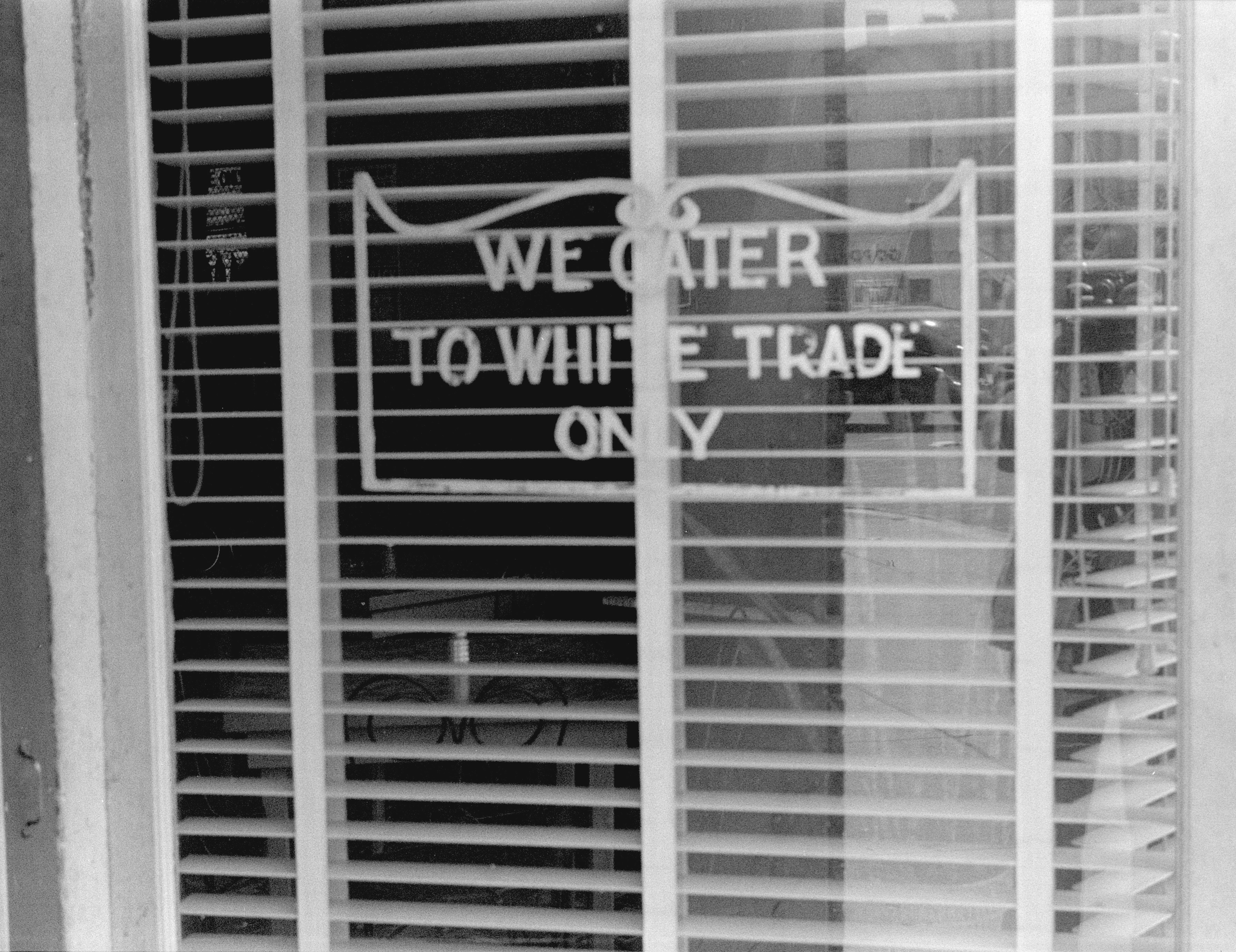

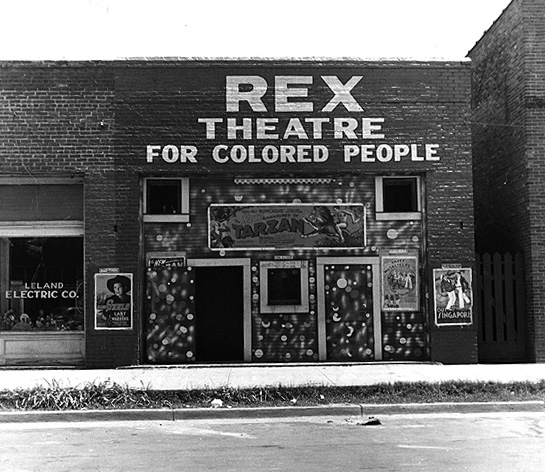

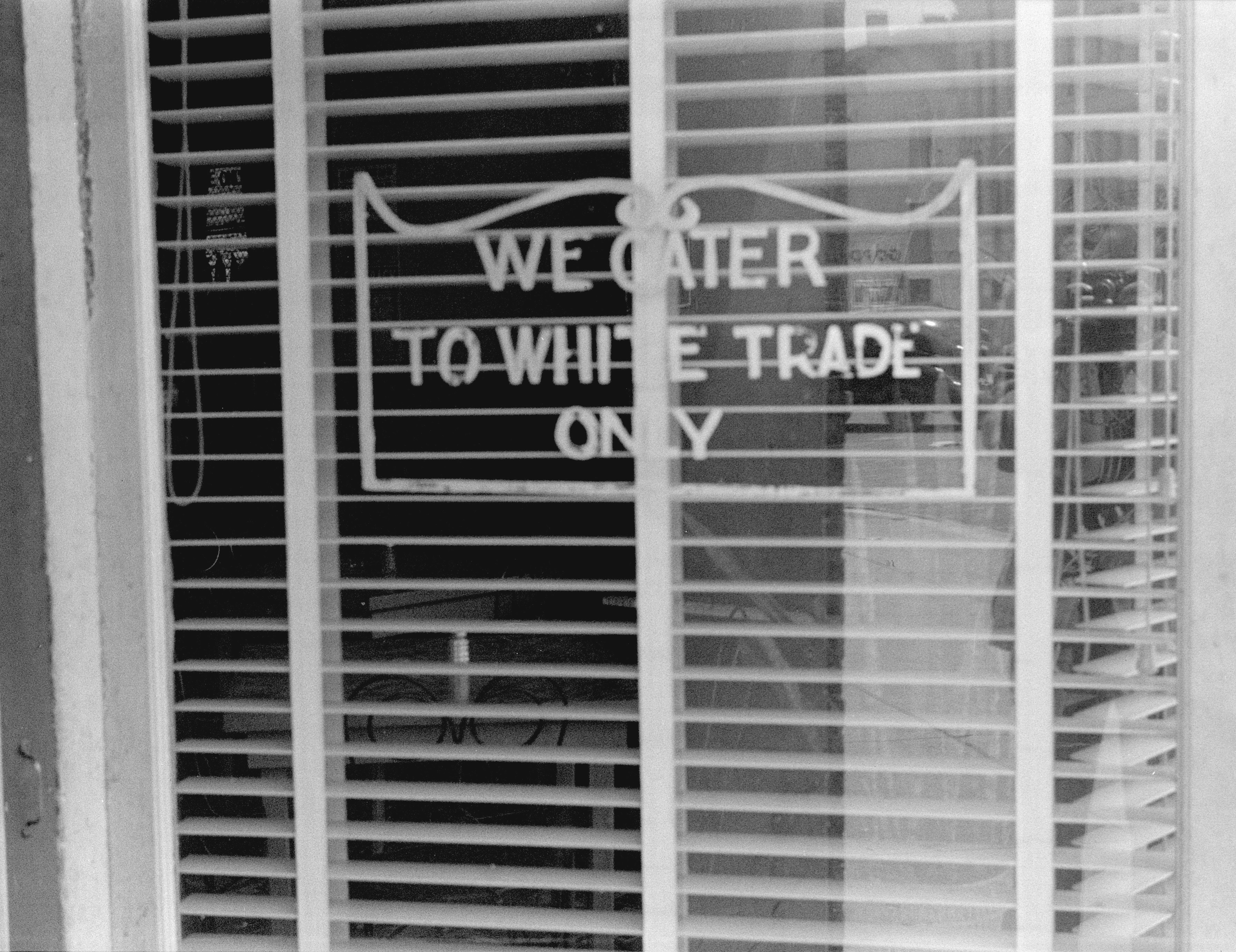

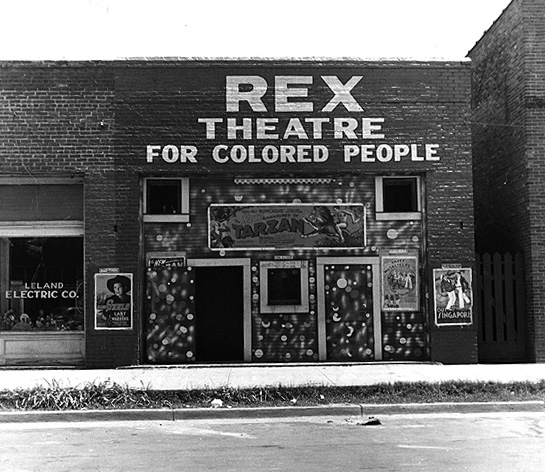

In the  Signs were used to indicate where African Americans could legally walk, talk, drink, rest, or eat. The

Signs were used to indicate where African Americans could legally walk, talk, drink, rest, or eat. The

The legitimacy of laws requiring segregation of black people was upheld by the

The legitimacy of laws requiring segregation of black people was upheld by the

Anti-miscegenation laws (also known as miscegenation laws) prohibited whites and non-whites from marrying each other. The first ever anti-miscegenation law was passed by the

Anti-miscegenation laws (also known as miscegenation laws) prohibited whites and non-whites from marrying each other. The first ever anti-miscegenation law was passed by the

"Hollywood Loved Sammy Davis Jr. Until He Dated a White Movie Star"

'' Smithsonian'' Retrieved February 23, 2021. In 1958, officers in In

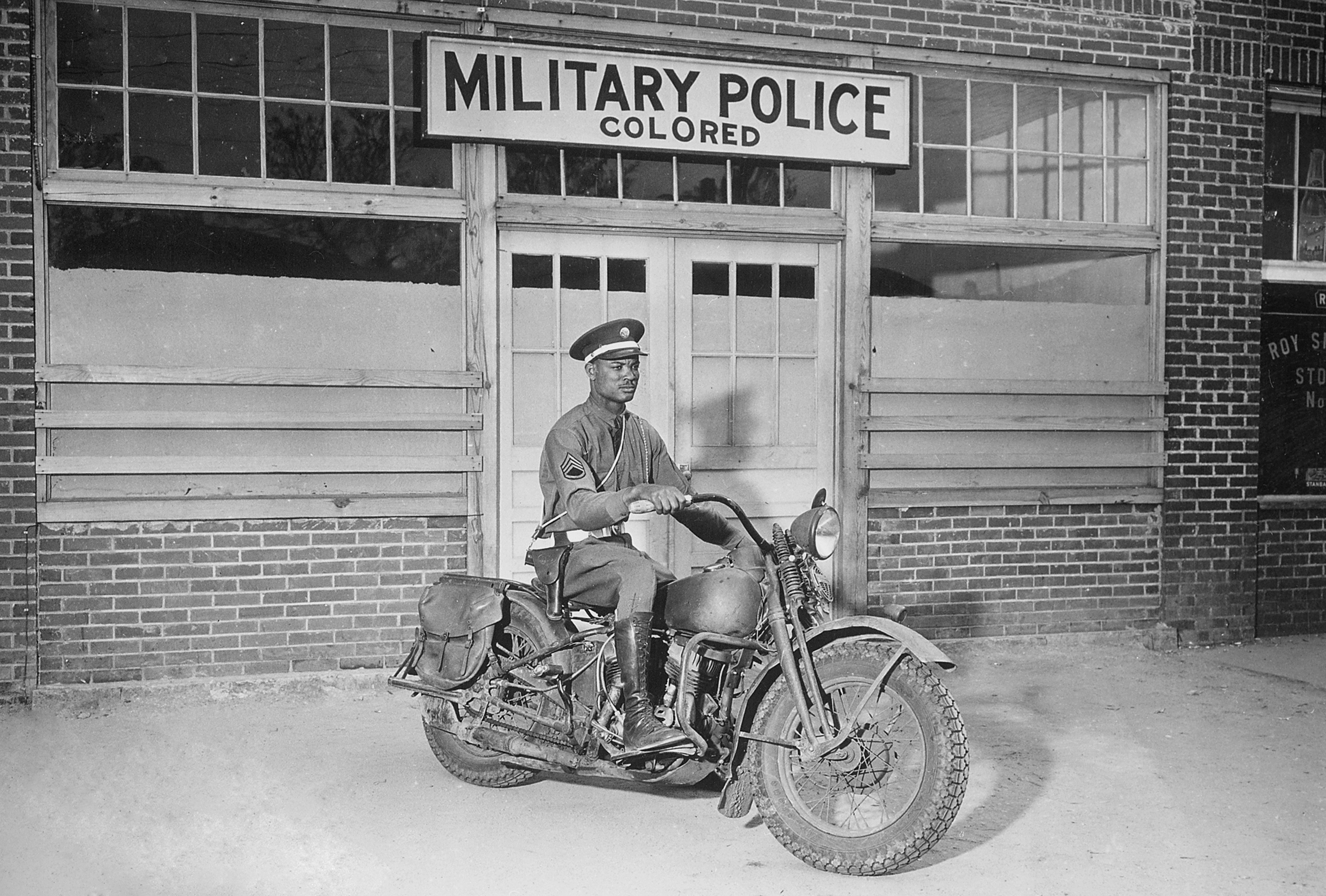

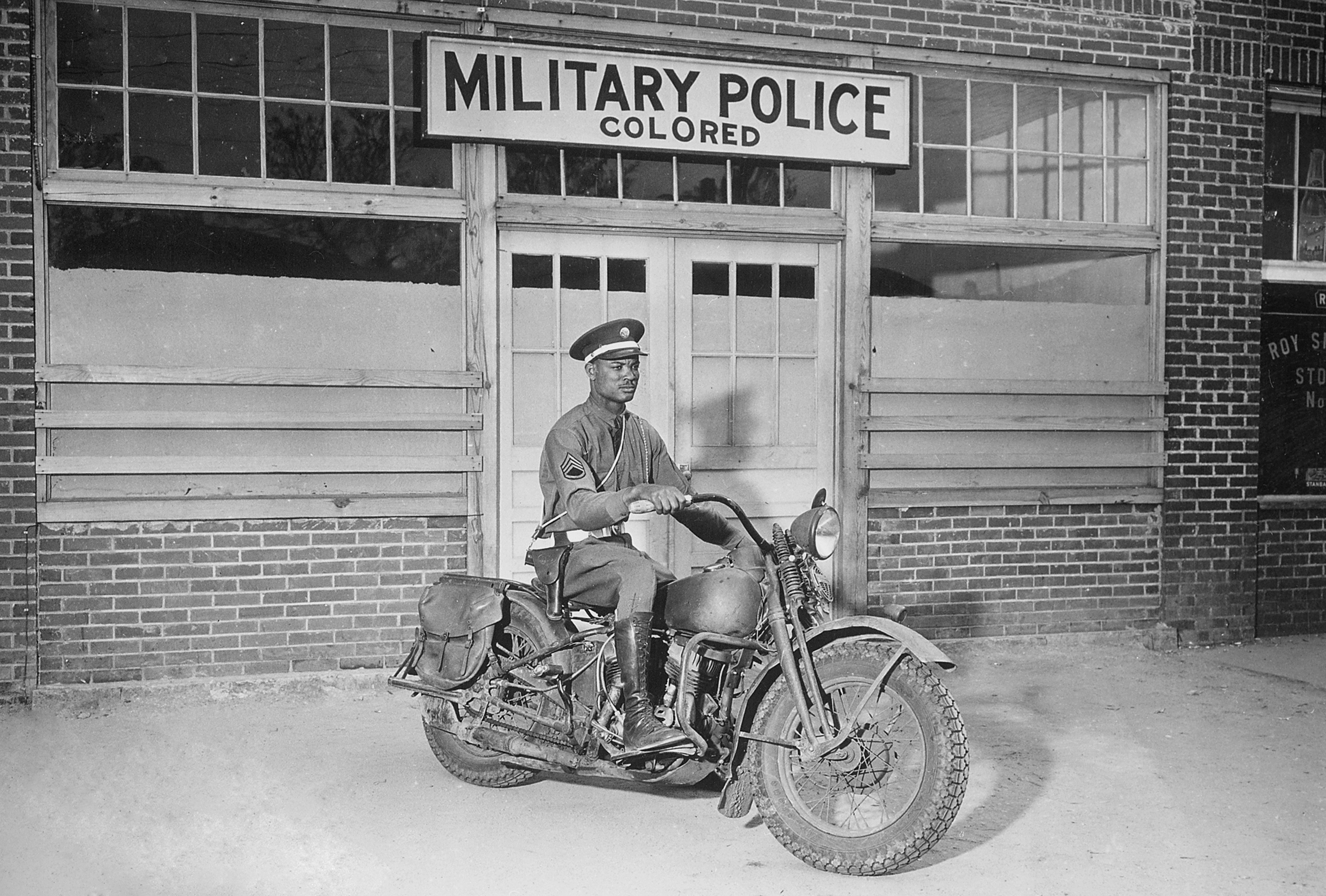

In  The U.S. military was still heavily segregated in World War II. The

The U.S. military was still heavily segregated in World War II. The  During World War II, 110,000 people of Japanese descent (whether citizens or not) were placed in

During World War II, 110,000 people of Japanese descent (whether citizens or not) were placed in

BBC. Retrieved July 17, 2017 A contract for a 1965 Beatles concert at the

After the end of Reconstruction and the withdrawal of federal troops, which followed from the Compromise of 1877, the Democratic governments in the South instituted state laws to separate black and white racial groups, submitting African-Americans to ''de facto'' second-class citizenship and enforcing

After the end of Reconstruction and the withdrawal of federal troops, which followed from the Compromise of 1877, the Democratic governments in the South instituted state laws to separate black and white racial groups, submitting African-Americans to ''de facto'' second-class citizenship and enforcing

– Minnesota Public Radio Sometimes, as in Florida's Constitution of 1885, segregation was mandated by state constitutions. Racial segregation became the law in most parts of the American South until the * In theory the segregated facilities available for negroes were of the same quality as those available to whites, under the

* In theory the segregated facilities available for negroes were of the same quality as those available to whites, under the

The rapid influx of blacks during the Great Migration disturbed the racial balance within Northern and Western cities, exacerbating hostility between both blacks and whites in the two regions. Deed restrictions and

The rapid influx of blacks during the Great Migration disturbed the racial balance within Northern and Western cities, exacerbating hostility between both blacks and whites in the two regions. Deed restrictions and  Within employment, economic opportunities for blacks were routed to the lowest-status and restrictive in potential mobility. In 1900 Reverend Matthew Anderson, speaking at the annual

Within employment, economic opportunities for blacks were routed to the lowest-status and restrictive in potential mobility. In 1900 Reverend Matthew Anderson, speaking at the annual

Racial segregation in

Racial segregation in

Prior to the 1930s, basketball saw a great deal of discrimination as well. Blacks and whites played mostly in different leagues and usually were forbidden from playing in inter-racial games. The popularity of the African American Harlem Globetrotters altered the American public's acceptance of African Americans in basketball. By the end of the 1930s, many northern colleges and universities allowed African Americans to play on their teams. In 1942, the color barrier for basketball was removed after Bill Jones and three other African American basketball players joined the Toledo Jim White Chevrolet NBL franchise and five Harlem Globetrotters joined the Chicago Studebakers.

In 1947, the

Prior to the 1930s, basketball saw a great deal of discrimination as well. Blacks and whites played mostly in different leagues and usually were forbidden from playing in inter-racial games. The popularity of the African American Harlem Globetrotters altered the American public's acceptance of African Americans in basketball. By the end of the 1930s, many northern colleges and universities allowed African Americans to play on their teams. In 1942, the color barrier for basketball was removed after Bill Jones and three other African American basketball players joined the Toledo Jim White Chevrolet NBL franchise and five Harlem Globetrotters joined the Chicago Studebakers.

In 1947, the

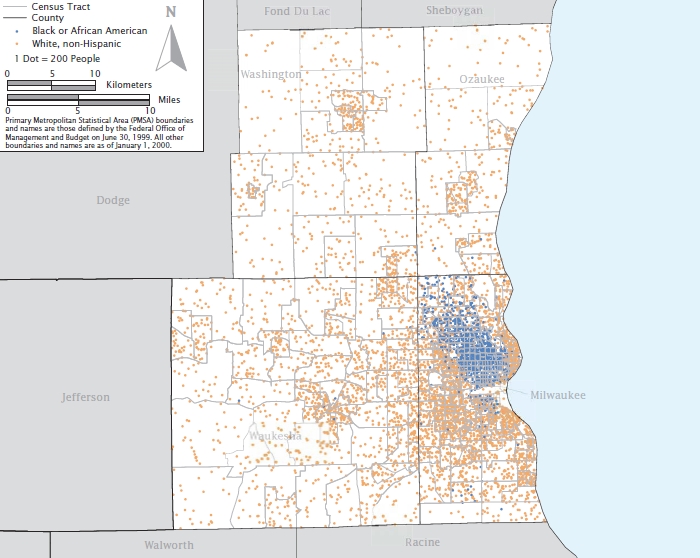

Racial segregation is most pronounced in housing. Although in the U.S. people of different races may work together, they are still very unlikely to live in integrated neighborhoods. This pattern differs only by degree in different metropolitan areas.

Residential segregation persists for a variety of reasons. Segregated neighborhoods may be reinforced by the practice of "

Racial segregation is most pronounced in housing. Although in the U.S. people of different races may work together, they are still very unlikely to live in integrated neighborhoods. This pattern differs only by degree in different metropolitan areas.

Residential segregation persists for a variety of reasons. Segregated neighborhoods may be reinforced by the practice of "

Segregation in

Segregation in

Apartheid America: Jonathan Kozol rails against a public school system that, 50 years after Brown v. Board of Education, is still deeply – and shamefully – segregated.

'' book review by Sarah Karnasiewicz for salon.com The words of "American apartheid" have been used in reference to the disparity between white and black schools in America. Those who compare this inequality to apartheid frequently point to unequal funding for predominantly black schools. In Chicago, by the academic year 2002–2003, 87 percent of public-school enrollment was black or Hispanic; less than 10 percent of children in the schools were white. In Washington, D.C., 94 percent of children were black or Hispanic; less than 5 percent were white.

In the

In the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

is the systematic separation of facilities and services such as housing

Housing, or more generally, living spaces, refers to the construction and assigned usage of houses or buildings individually or collectively, for the purpose of shelter. Housing ensures that members of society have a place to live, whether i ...

, healthcare, education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty ...

, employment, and transportation

Transport (in British English), or transportation (in American English), is the intentional movement of humans, animals, and goods from one location to another. Modes of transport include air, land (rail and road), water, cable, pipeline, ...

on racial grounds. The term is mainly used in reference to the legally or socially enforced separation of African Americans from whites

White is a racialized classification of people and a skin color specifier, generally used for people of European origin, although the definition can vary depending on context, nationality, and point of view.

Description of populations as ...

, but it is also used in reference to the separation of other ethnic minorities

The term 'minority group' has different usages depending on the context. According to its common usage, a minority group can simply be understood in terms of demographic sizes within a population: i.e. a group in society with the least number o ...

from majority and mainstream communities. While mainly referring to the physical separation and provision of separate facilities, it can also refer to other manifestations such as prohibitions against interracial marriage

Interracial marriage is a marriage involving spouses who belong to different races or racialized ethnicities.

In the past, such marriages were outlawed in the United States, Nazi Germany and apartheid-era South Africa as miscegenation. In 1 ...

(enforced with anti-miscegenation laws), and the separation of roles within an institution. Notably, in the United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six service branches: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard. The president of the United States is ...

up until 1948, black units were typically separated from white units but were still led by white officers.

Signs were used to indicate where African Americans could legally walk, talk, drink, rest, or eat. The

Signs were used to indicate where African Americans could legally walk, talk, drink, rest, or eat. The U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

upheld the constitutionality of segregation in ''Plessy v. Ferguson

''Plessy v. Ferguson'', 163 U.S. 537 (1896), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in which the Court ruled that racial segregation laws did not violate the U.S. Constitution as long as the facilities for each race were equal in qualit ...

'' (1896), so long as "separate but equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law, according to which racial segregation did not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which nominally guaranteed "equal protec ...

" facilities were provided, a requirement that was rarely met in practice. The doctrine's applicability to public schools was unanimously overturned in ''Brown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segrega ...

'' (1954) by the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren. In the following years the Warren Court

The Warren Court was the period in the history of the Supreme Court of the United States during which Earl Warren served as Chief Justice. Warren replaced the deceased Fred M. Vinson as Chief Justice in 1953, and Warren remained in office until ...

further ruled against racial segregation in several landmark cases including '' Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States'' (1964), which helped bring an end to the Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

.

Racial segregation follows two forms. ''De jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legally ...

'' segregation mandated the separation of races by law, and was the form imposed by slave codes before the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

and by Black Codes and Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

following the war. ''De jure'' segregation was outlawed by the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968. ''De facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with ''de jure'' ("by la ...

'' segregation, or segregation "in fact", is that which exists without sanction of the law. ''De facto'' segregation continues today in areas such as residential segregation and school segregation School segregation is the division of people into different groups in the education system by characteristics such as race, religion, or ethnicity. See also

*'' D.H. and Others v. the Czech Republic''

*School segregation in the United States

*Single ...

because of both contemporary behavior and the historical legacy of ''de jure'' segregation.

History

Reconstruction in the South

Congress passed theReconstruction Acts

The Reconstruction Acts, or the Military Reconstruction Acts, (March 2, 1867, 14 Stat. 428-430, c.153; March 23, 1867, 15 Stat. 2-5, c.6; July 19, 1867, 15 Stat. 14-16, c.30; and March 11, 1868, 15 Stat. 41, c.25) were four statutes passed duri ...

of 1867, ratified

Ratification is a principal's approval of an act of its agent that lacked the authority to bind the principal legally. Ratification defines the international act in which a state indicates its consent to be bound to a treaty if the parties inten ...

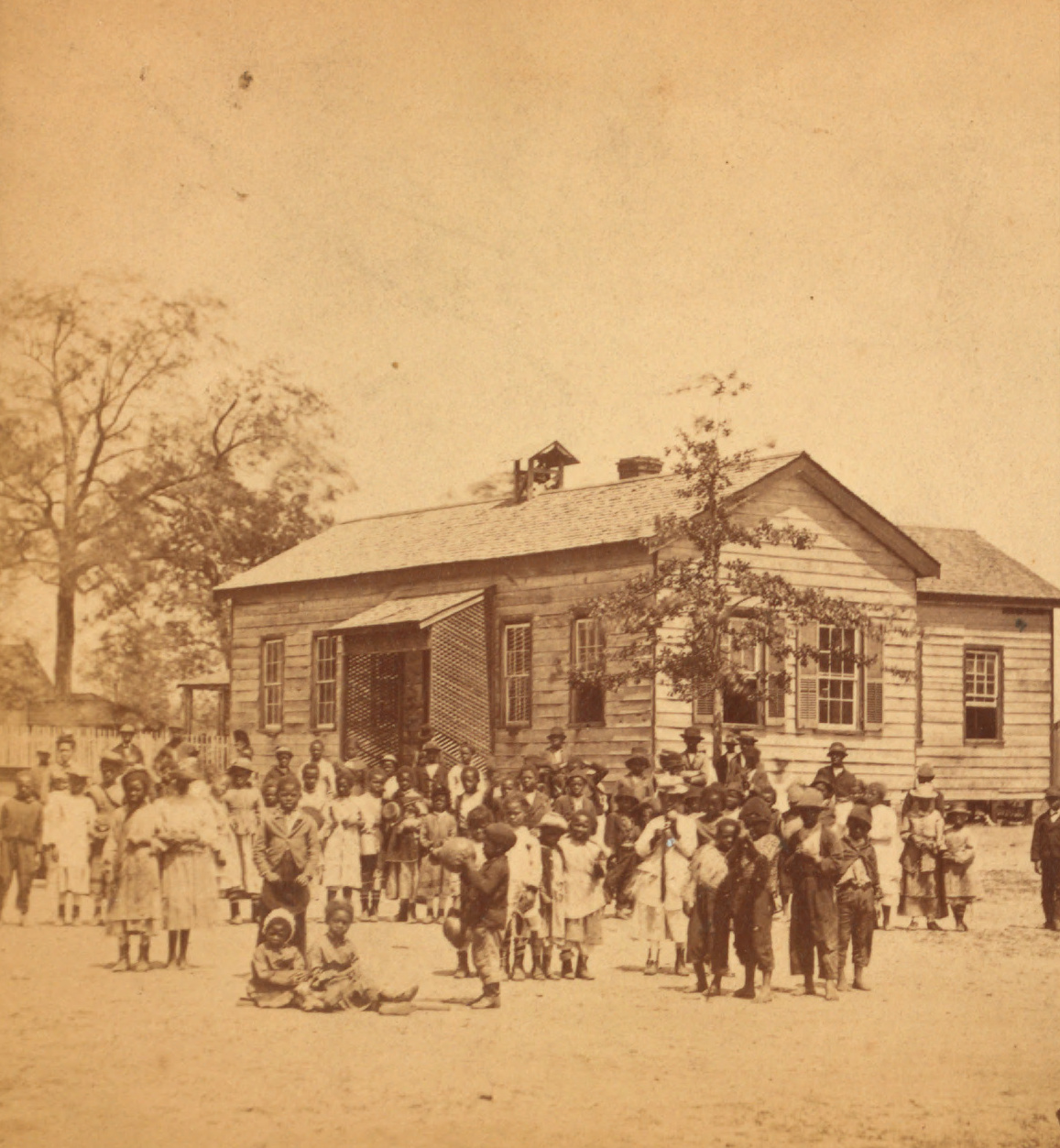

the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1870, granting African Americans the right to vote, and it also enacted the Civil Rights Act of 1875 forbidding racial segregation in accommodations. As a result, the presence of Federal occupation troops in the South assured that black people were allowed to vote and elect their own political leaders. The Reconstruction amendments asserted the supremacy of the national state and they also asserted that everyone within it was formally equal under the law. However, it did not prohibit segregation in schools.

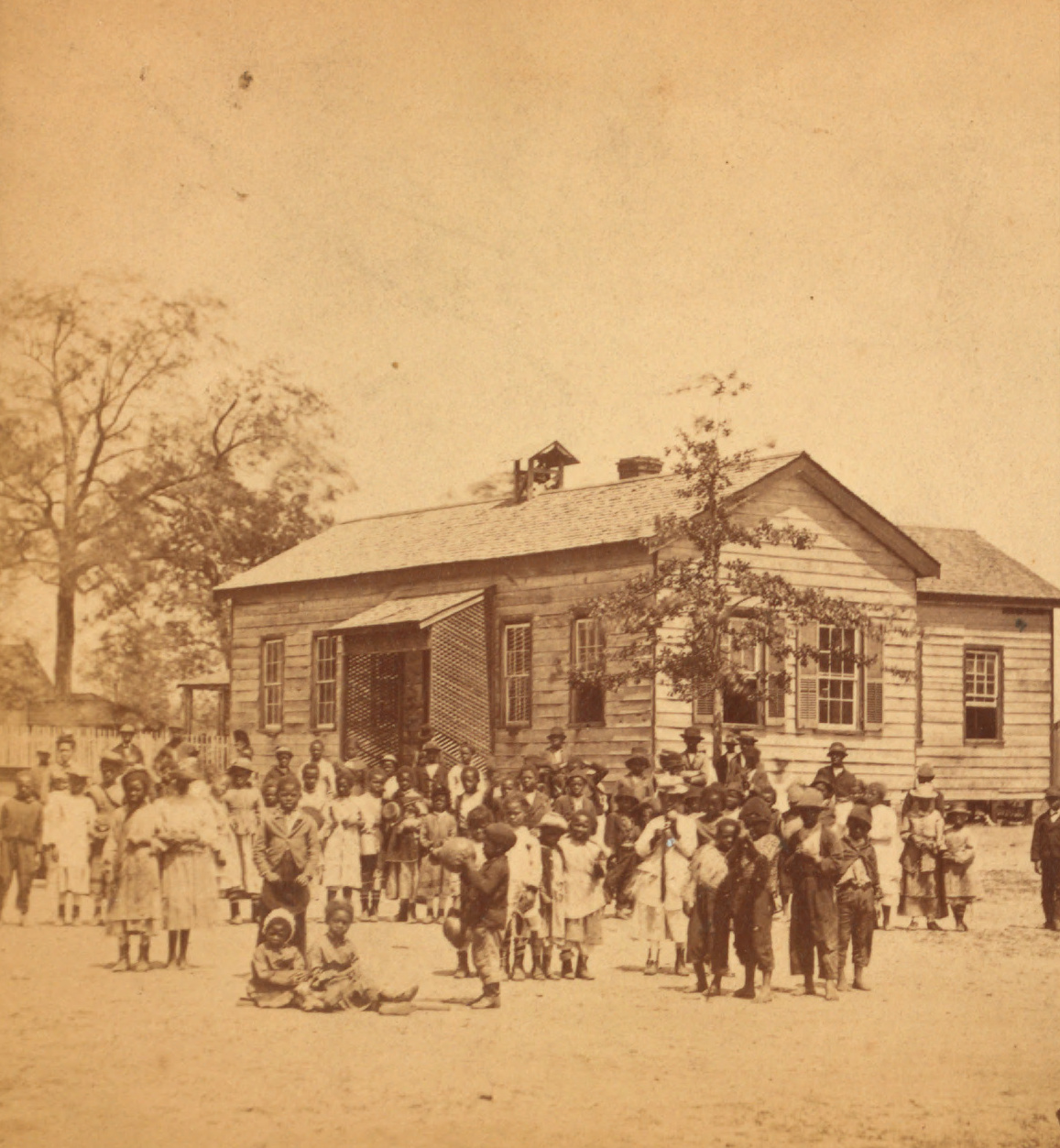

When the Republicans came to power in the Southern states after 1867, they created the first system of taxpayer-funded public schools. Southern black people wanted public schools for their children, but they did not demand racially integrated schools. Almost all the new public schools were segregated, apart from a few in . After the Republicans lost power in the mid-1870s, Southern Democrats

Southern Democrats, historically sometimes known colloquially as Dixiecrats, are members of the U.S. Democratic Party who reside in the Southern United States. Southern Democrats were generally much more conservative than Northern Democrats wi ...

retained the public school systems but sharply cut their funding.

Almost all private academies and colleges in the South were strictly segregated by race. The American Missionary Association supported the development and establishment of several historically black colleges including Fisk University and Shaw University. In this period, a handful of northern colleges accepted black students. Northern denominations and especially their missionary associations established private schools across the South to provide secondary education. They provided a small amount of collegiate work. Tuition was minimal, so churches financially supported the colleges and also subsidized the pay of some teachers. In 1900, churches—mostly based in the North—operated 247 schools for black people across the South, with a budget of about $1 million. They employed 1600 teachers and taught 46,000 students. Prominent schools included Howard University

Howard University (Howard) is a Private university, private, University charter#Federal, federally chartered historically black research university in Washington, D.C. It is Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, classifie ...

, a private, federally chartered institution based in Washington, D.C.; Fisk University in Nashville, Atlanta University

Clark Atlanta University (CAU or Clark Atlanta) is a private, Methodist, historically black research university in Atlanta, Georgia. Clark Atlanta is the first Historically Black College or University (HBCU) in the Southern United States. Fou ...

, Hampton Institute

Hampton University is a private, historically black, research university in Hampton, Virginia. Founded in 1868 as Hampton Agricultural and Industrial School, it was established by Black and White leaders of the American Missionary Association aft ...

in Virginia, and others.

By the early 1870s, the North lost interest in further reconstruction efforts, and, when federal troops were withdrawn in 1877, the Republican Party in the South splintered and lost support, leading to the conservatives (calling themselves "Redeemers

The Redeemers were a political coalition in the Southern United States during the Reconstruction Era that followed the Civil War. Redeemers were the Southern wing of the Democratic Party. They sought to regain their political power and enforce ...

") taking control of all the Southern states. 'Jim Crow' segregation began somewhat later, in the 1880s. Disfranchisement of black people began in the 1890s. Although the Republican Party had championed African-American rights during the Civil War and had become a platform for black political influence during Reconstruction, a backlash among white Republicans led to the rise of the lily-white movement to remove African Americans from leadership positions in the party and to incite riots to divide the party, with the ultimate goal of eliminating black influence. By 1910, segregation was firmly established across the South and most of the border region, and only a small number of black leaders were allowed to vote across the Deep South.

Jim Crow era

The legitimacy of laws requiring segregation of black people was upheld by the

The legitimacy of laws requiring segregation of black people was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

in the 1896 case of ''Plessy v. Ferguson

''Plessy v. Ferguson'', 163 U.S. 537 (1896), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in which the Court ruled that racial segregation laws did not violate the U.S. Constitution as long as the facilities for each race were equal in qualit ...

'', 163 U.S. 537. The Supreme Court sustained the constitutionality of a Louisiana statute that required railroad companies to provide "separate but equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law, according to which racial segregation did not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which nominally guaranteed "equal protec ...

" accommodations for white and black passengers, and prohibited white people and black people from using railroad cars that were not assigned to their race.

''Plessy'' thus allowed segregation, which became standard throughout the southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

, and represented the institutionalization of the Jim Crow period. Everyone was supposed to receive the same public services (schools, hospitals, prisons, etc.), but with separate facilities for each race. In practice, the services and facilities reserved for African-Americans were almost always of lower quality than those reserved for white people, if they existed at all; for example, most African-American schools received less public funding per student than nearby white schools. Segregation was not mandated by law in the Northern states, but a ''de facto'' system grew for schools, in which nearly all black students attended schools that were nearly all-black. In the South, white schools had only white pupils and teachers, while black schools had only black teachers and black students.

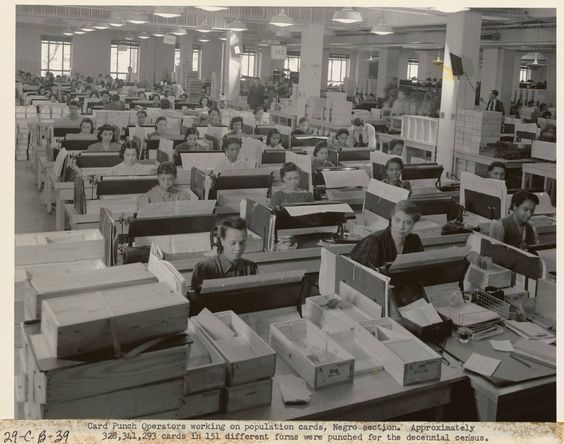

President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

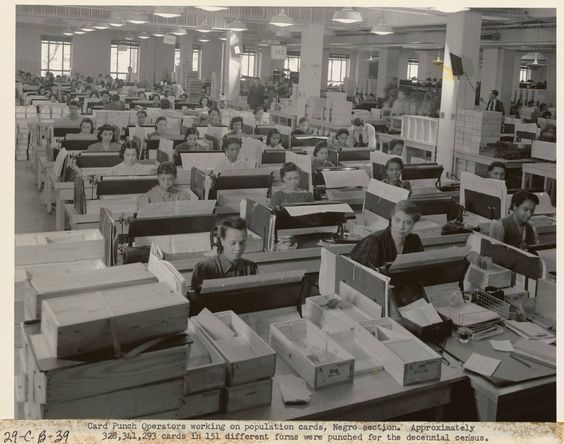

, a Southern Democrat, initiated the segregation of federal workplaces in 1913.

Some streetcar

A tram (called a streetcar or trolley in North America) is a rail vehicle that travels on tramway tracks on public urban streets; some include segments on segregated right-of-way. The tramlines or networks operated as public transport a ...

companies did not segregate voluntarily. It took 15 years for the government to break down their resistance.

On at least six occasions over nearly 60 years, the Supreme Court held, either explicitly or by necessary implication, that the "separate but equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law, according to which racial segregation did not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which nominally guaranteed "equal protec ...

" rule announced in Plessy was the correct rule of law, although, toward the end of that period, the Court began to focus on whether the separate facilities were in fact equal.

The repeal of "separate but equal" laws was a major focus of the civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

. In ''Brown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segrega ...

'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), the Supreme Court outlawed segregated public education facilities for black people and white people at the state level. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 superseded all state and local laws requiring segregation. Compliance with the new law came slowly, and it took years with many cases in lower courts to enforce it.

New Deal era

The New Deal of the 1930s was racially segregated; black people and whites rarely worked alongside each other in New Deal programs. The largest relief program by far was theWorks Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; renamed in 1939 as the Work Projects Administration) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to carry out public works projects, i ...

(WPA); it operated segregated units, as did its youth affiliate, the National Youth Administration

The National Youth Administration (NYA) was a New Deal agency sponsored by Franklin D. Roosevelt during his presidency. It focused on providing work and education for Americans between the ages of 16 and 25. It operated from June 26, 1935 to ...

(NYA). Black people were hired by the WPA as supervisors in the North; of 10,000 WPA supervisors in the South, only 11 were black. Historian Anthony Badger argues, "New Deal programs in the South routinely discriminated against black people and perpetuated segregation." In its first few weeks of operation, Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a voluntary government work relief program that ran from 1933 to 1942 in the United States for unemployed, unmarried men ages 18–25 and eventually expanded to ages 17–28. The CCC was a major part of ...

(CCC) camps in the North were integrated. By July 1935, practically all the CCC camps in the United States were segregated, and black people were strictly limited in the supervisory roles they were assigned. Philip Klinkner and Rogers Smith argue that "even the most prominent racial liberals in the New Deal did not dare to criticize Jim Crow." Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes was one of the Roosevelt Administration's most prominent supporters of black people and former president of the Chicago chapter of the NAACP. In 1937, when Senator Josiah Bailey, a Democrat from North Carolina, accused him of trying to break down segregation laws, Ickes wrote him to deny that:

:I think it is up to the states to work out their social problems if possible, and while I have always been interested in seeing that the Negro has a square deal, I have never dissipated my strength against the particular stone wall of segregation. I believe that wall will crumble when the Negro has brought himself to a high educational and economic status…. Moreover, while there are no segregation laws in the North, there is segregation in fact and we might as well recognize this.

The New Deal, nonetheless, provided unprecedented federal benefits to blacks. This led many to become part of the New Deal coalition from their base in Northern and Western cities where they could now vote, having in large numbers left the South during the Great Migration. Influenced in part by the " Black Cabinet" advisors and the March on Washington Movement

The March on Washington Movement (MOWM), 1941–1946, organized by activists A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin was a tool designed to pressure the U.S. government into providing fair working opportunities for African Americans and desegregating ...

, just prior to America's entry into World War II, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802

Executive Order 8802 was signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on June 25, 1941, to prohibit ethnic or racial discrimination in the nation's defense industry. It also set up the Fair Employment Practice Committee. It was the first federal ac ...

, the first anti-discrimination order at the federal level and established the Fair Employment Practices Committee. Roosevelt's successor, President Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

appointed the President's Committee on Civil Rights

The President's Committee on Civil Rights was a United States presidential commission established by President Harry Truman in 1946. The committee was created by Executive Order 9808 on December 5, 1946, and instructed to investigate the status o ...

, and issued Executive Order 9980 and Executive Order 9981

Executive Order 9981 was issued on July 26, 1948, by President Harry S. Truman. This executive order abolished discrimination "on the basis of race, color, religion or national origin" in the United States Armed Forces, and led to the re-integra ...

providing for desegregation throughout the federal government and the armed forces.

Hypersegregation

In an often-cited 1988 study, Douglas Massey and Nancy Denton compiled 20 existing segregation measures and reduced them to five dimensions of residential segregation. Dudley L. Poston and Michael Micklin argue that Massey and Denton "brought conceptual clarity to the theory of segregation measurement by identifying five dimensions". African Americans are considered to be racially segregated because of all five dimensions of segregation being applied to them within these inner cities across the U.S. These five dimensions are evenness, clustering, exposure, centralization and concentration. Evenness is the difference between the percentage of a minority group in a particular part of a city, compared to the city as a whole. Exposure is the likelihood that a minority and a majority party will come in contact with one another. Clustering is the gathering of different minority groups into a single space; clustering often leads to one bigghetto

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished t ...

and the formation of "hyperghettoization." Centralization measures the tendency of members of a minority group to be located in the middle of an urban area, often computed as a percentage of a minority group living in the middle of a city (as opposed to the outlying areas). Concentration is the dimension that relates to the actual amount of land a minority lives on within its particular city. The higher segregation is within that particular area, the smaller the amount of land a minority group will control.

The pattern of hypersegregation began in the early 20th century. African-Americans who moved to large cities often moved into the inner-city in order to gain industrial jobs. The influx of new African-American residents caused many white residents to move to the suburbs in a case of white flight

White flight or white exodus is the sudden or gradual large-scale migration of white people from areas becoming more racially or ethnoculturally diverse. Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, the terms became popular in the United States. They refer ...

. As industry began to move out of the inner-city, the African-American residents lost the stable jobs that had brought them to the area. Many were unable to leave the inner-city and became increasingly poor. This created the inner-city ghettos that make up the core of hypersegregation. Though the Civil Rights Act of 1968 banned discrimination in housing, housing patterns established earlier saw the perpetuation of hypersegregation. Data from the 2000 census shows that 29 metropolitan areas displayed black-white hypersegregation. Two areas—Los Angeles and New York City—displayed Hispanic-white hypersegregation. No metropolitan area displayed hypersegregation for Asians or for Native Americans.

Racism

During most of the 20th century, many (perhaps most) whites believed that the presence of blacks in white neighborhoods would bring downproperty value

Real estate appraisal, property valuation or land valuation is the process of developing an opinion of value for real property (usually market value). Real estate transactions often require appraisals because they occur infrequently and every prop ...

s. The United States government began to make low-interest mortgages available to families through the Federal Housing Administration

The Federal Housing Administration (FHA), also known as the Office of Housing within the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), is a United States government agency founded by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, created in part by ...

(FHA) and the Veteran's Administration

The United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is a Cabinet-level executive branch department of the federal government charged with providing life-long healthcare services to eligible military veterans at the 170 VA medical centers and ...

. Black families were legally entitled to these loans but they were sometimes denied these loans because the planners who were behind this initiative labeled many black neighborhoods throughout the country as neighborhoods which were "in decline". The rules for loans did not say that "black families cannot get loans"; rather, they said that people who were from "areas in decline" could not get loans. While a case could be made that the wording did not appear to compel segregation, it tended to have that effect. In fact, this administration was formed as part of the New Deal for all Americans but it mostly affected black residents of inner-city areas; most black families did in fact live in the inner city

The term ''inner city'' has been used, especially in the United States, as a euphemism for majority-minority lower-income residential districts that often refer to rundown neighborhoods, in a downtown or city centre area. Sociologists some ...

areas of large cities and they almost entirely occupied these areas after the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

when whites began to move to new suburbs.

The government encouraged white families to move into suburbs by granting them loans, and it uprooted many established African American communities by building elevated highways through their neighborhoods. In order to build these elevated highways, the government destroyed tens of thousands of single-family homes. Because these properties were summarily declared to be "in decline," families were given pittances for their properties, and forced to move into federally-funded housing which was called "the projects". To build these projects, still more single-family homes were demolished.

President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

did not oppose segregation practices by autonomous department heads of the federal Civil Service, according to Brian J. Cook in his work, ''Democracy And Administration: Woodrow Wilson's Ideas And The Challenges Of Public Management''. White and black people were sometimes required to eat separately, go to separate schools, use separate public toilets, park benches, train, buses, and water fountains, etc. In some locales, stores and restaurants refused to serve different races under the same roof.

Public segregation was challenged by individual citizens on rare occasions but had minimal impact on civil rights issues, until December 1955, in Montgomery, Alabama, Rosa Parks

Rosa Louise McCauley Parks (February 4, 1913 – October 24, 2005) was an American activist in the civil rights movement best known for her pivotal role in the Montgomery bus boycott. The United States Congress has honored her as "th ...

refused to be moved to the back of a bus for a white passenger. Parks' civil disobedience had the effect of sparking the Montgomery bus boycott

The Montgomery bus boycott was a political and social protest campaign against the policy of racial segregation on the public transit system of Montgomery, Alabama. It was a foundational event in the civil rights movement in the United States ...

. Parks' act of defiance became an important symbol of the modern Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

and Parks became an international icon of resistance to racial segregation.

Segregation was also pervasive in housing. State constitutions (for example, that of California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

) had clauses giving local jurisdictions the right to regulate where members of certain races could live. In 1917, the Supreme Court in the case of '' Buchanan v. Warley'' declared municipal resident segregation ordinances unconstitutional. In response, whites resorted to the restrictive covenant, a formal deed restriction binding white property owners in a given neighborhood not to sell to blacks. Whites who broke these agreements could be sued by "damaged" neighbors. In the 1948 case of '' Shelley v. Kraemer'', the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

finally ruled that such covenants were unenforceable in a court of law. Residential segregation patterns had already become established in most American cities, and have often persisted up to the present from the impact of white flight

White flight or white exodus is the sudden or gradual large-scale migration of white people from areas becoming more racially or ethnoculturally diverse. Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, the terms became popular in the United States. They refer ...

and Redlining.

In most cities, the only way blacks could relieve the pressure of crowding that resulted from increasing migration was to expand residential borders into surrounding previously white neighborhoods, a process that often resulted in harassment and attacks by white residents whose intolerant attitudes were intensified by fears that black neighbors would cause property values to decline. Moreover, the increased presence of African Americans in cities, North and South, as well as their competition with whites for housing, jobs, and political influence sparked a series of race riots. In 1898 white citizens of Wilmington, North Carolina

Wilmington is a port city in and the county seat of New Hanover County in coastal southeastern North Carolina, United States.

With a population of 115,451 at the 2020 census, it is the eighth most populous city in the state. Wilmington is t ...

, resenting African Americans' involvement in local government and incensed by an editorial in an African-American newspaper

African-American newspapers (also known as the Black press or Black newspapers) are news publications in the United States serving African-American communities. Samuel Cornish and John Brown Russwurm started the first African-American period ...

accusing white women of loose sexual behavior, rioted and killed dozens of blacks. In the fury's wake, white supremacists overthrew the city government, expelling black and white officeholders, and instituted restrictions to prevent blacks from voting. In Atlanta in 1906, newspaper accounts alleging attacks by black men on white women provoked an outburst of shooting and killing that left twelve blacks dead and seventy injured. An influx of unskilled black strikebreakers into East St Louis, Illinois, heightened racial tensions in 1917. Rumors that blacks were arming themselves for an attack on whites resulted in numerous attacks by white mobs on black neighborhoods. On July 1, blacks fired back at a car whose occupants they believed had shot into their homes and mistakenly killed two policemen riding in a car. The next day, a full-scaled riot erupted which ended only after nine whites and thirty-nine blacks had been killed and over three hundred buildings were destroyed.

Anti-miscegenation laws (also known as miscegenation laws) prohibited whites and non-whites from marrying each other. The first ever anti-miscegenation law was passed by the

Anti-miscegenation laws (also known as miscegenation laws) prohibited whites and non-whites from marrying each other. The first ever anti-miscegenation law was passed by the Maryland General Assembly

The Maryland General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maryland that convenes within the State House in Annapolis. It is a bicameral body: the upper chamber, the Maryland Senate, has 47 representatives and the lower chamber ...

in 1691, criminalizing interracial marriage. During one of his famous debates with Stephen A. Douglas in Charleston, Illinois

Charleston is a city in, and the county seat of, Coles County, Illinois, United States. The population was 17,286, as of the 2020 census. The city is home to Eastern Illinois University and has close ties with its neighbor, Mattoon. Both are ...

in 1858, Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

stated, "I am not, nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people". By the late 1800s, 38 US states had anti-miscegenation statutes. By 1924, the ban on interracial marriage was still in force in 29 states.

While interracial marriage had been legal in California since 1948, in 1957 actor Sammy Davis Jr.

Samuel George Davis Jr. (December 8, 1925 – May 16, 1990) was an American singer, dancer, actor, comedian, film producer and television director.

At age three, Davis began his career in vaudeville with his father Sammy Davis Sr. and the ...

faced a backlash for his involvement with white actress Kim Novak

Marilyn Pauline "Kim" Novak (born February 13, 1933) is an American retired film and television actress and painter.

Novak began her career in 1954 after signing with Columbia Pictures and quickly became one of Hollywood's top box office stars, ...

. Harry Cohn, the president of Columbia Pictures (with whom Novak was under contract) gave in to his concerns that a racist backlash against the relationship could hurt the studio. Davis briefly married black dancer Loray White in 1958 to protect himself from mob violence. Inebriated at the wedding ceremony, Davis despairingly said to his best friend, Arthur Silber Jr., "Why won't they let me live my life?" The couple never lived together and commenced divorce proceedings in September 1958.Lanzendorfer, Joy (August 9, 2017"Hollywood Loved Sammy Davis Jr. Until He Dated a White Movie Star"

'' Smithsonian'' Retrieved February 23, 2021. In 1958, officers in

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

entered the home of Richard and Mildred Loving and dragged them out of bed for living together as an interracial couple, on the basis that "any white person intermarry with a colored person"— or vice versa—each party "shall be guilty of a felony" and face prison terms of five years. In 1965, Virginia trial court Judge Leon Bazile, who heard their original case, defended his decision:

In

In World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, blacks served in the United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six service branches: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard. The president of the United States is ...

in segregated units. Black soldiers were often poorly trained and equipped, and were often put on the frontlines in suicide mission

A suicide mission is a task which is so dangerous for the people involved that they are not expected to survive. The term is sometimes extended to include suicide attacks such as kamikaze and suicide bombings, whose perpetrators actively commit s ...

s. The 369th Infantry (formerly 15th New York National Guard) Regiment distinguished themselves, and were known as the "Harlem Hellfighters

The 369th Infantry Regiment, originally formed as the 15th New York National Guard Regiment before being re-organized as the 369th upon federalization and commonly referred to as the Harlem Hellfighters, was an infantry regiment of the New Y ...

".

The U.S. military was still heavily segregated in World War II. The

The U.S. military was still heavily segregated in World War II. The Army Air Corps Army Air Corps may refer to the following army aviation corps:

* Army Air Corps (United Kingdom), the army aviation element of the British Army

* Philippine Army Air Corps (1935–1941)

* United States Army Air Corps (1926–1942), or its p ...

(forerunner of the Air Force

An air force – in the broadest sense – is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an ...

) and the Marines

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refle ...

had no blacks enlisted in their ranks. There were blacks in the Navy Seabees. The army had only five African-American officers. No African American received the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valo ...

during the war, and their tasks in the war were largely reserved to non-combat units. Black soldiers had to sometimes give up their seats in trains to the Nazi prisoners of war. World War II saw the first black military pilots in the U.S., the Tuskegee Airmen

The Tuskegee Airmen were a group of primarily African American military pilots (fighter and bomber) and airmen who fought in World War II. They formed the 332d Fighter Group and the 477th Bombardment Group (Medium) of the United States Army ...

, 99th Fighter Squadron, and also saw the segregated 183rd Engineer Combat Battalion participate in the liberation of Jewish survivors at Buchenwald concentration camp. Despite the institutional policy of racially segregated training for enlisted members and in tactical units; Army policy dictated that black and white soldiers train together in officer candidate school

An officer candidate school (OCS) is a military school which trains civilians and enlisted personnel in order for them to gain a commission as officers in the armed forces of a country. How OCS is run differs between countries and services. Ty ...

s (beginning in 1942). Thus, the Officer Candidate School

An officer candidate school (OCS) is a military school which trains civilians and enlisted personnel in order for them to gain a commission as officers in the armed forces of a country. How OCS is run differs between countries and services. Ty ...

became the Army's first formal experiment with integration – with all Officer Candidates, regardless of race, living and training together.

During World War II, 110,000 people of Japanese descent (whether citizens or not) were placed in

During World War II, 110,000 people of Japanese descent (whether citizens or not) were placed in internment camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

s. Hundreds of people of German and Italian descent were also imprisoned (see German American internment

Internment of German resident aliens and German-American citizens occurred in the United States during the periods of World War I and World War II. During World War II, the legal basis for this detention was under Presidential Proclamation 2526, ...

and Italian American internment). While the government program of Japanese American internment targeted all the Japanese in America as enemies, most German and Italian Americans were left in peace and were allowed to serve in the U.S. military.

Pressure to end racial segregation in the government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is ...

grew among African Americans and progressives after the end of World War II. On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

signed Executive Order 9981

Executive Order 9981 was issued on July 26, 1948, by President Harry S. Truman. This executive order abolished discrimination "on the basis of race, color, religion or national origin" in the United States Armed Forces, and led to the re-integra ...

, ending segregation in the United States Armed Forces.

A club central to the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s, the Cotton Club

The Cotton Club was a New York City nightclub from 1923 to 1940. It was located on 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue (1923–1936), then briefly in the midtown Theater District (1936–1940).Elizabeth Winter"Cotton Club of Harlem (1923- )" Blac ...

in Harlem, New York City was a whites-only establishment, with blacks (such as Duke Ellington) allowed to perform, but to a white audience. The first black Oscar recipient Hattie McDaniel

Hattie McDaniel (June 10, 1893October 26, 1952) was an American actress, singer-songwriter, and comedian. For her role as Mammy in ''Gone with the Wind (film), Gone with the Wind'' (1939), she won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress, ...

was not permitted to attend the premiere of ''Gone with the Wind

Gone with the Wind most often refers to:

* ''Gone with the Wind'' (novel), a 1936 novel by Margaret Mitchell

* ''Gone with the Wind'' (film), the 1939 adaptation of the novel

Gone with the Wind may also refer to:

Music

* ''Gone with the Wind'' ...

'' with Atlanta being racially segregated, and at the 12th Academy Awards

The 12th Academy Awards ceremony, held on February 29, 1940 by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS), honored the best in film for 1939 at a banquet in the Coconut Grove at The Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. It was hosted ...

ceremony at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

she was required to sit at a segregated table at the far wall of the room; the hotel had a no-blacks policy, but allowed McDaniel in as a favor. McDaniel's final wish to be buried in Hollywood Cemetery was denied because the graveyard was restricted to whites only.

On September 11, 1964, John Lennon

John Winston Ono Lennon (born John Winston Lennon; 9 October 19408 December 1980) was an English singer, songwriter, musician and peace activist who achieved worldwide fame as founder, co-songwriter, co-lead vocalist and rhythm guitarist of ...

announced The Beatles

The Beatles were an English rock band, formed in Liverpool in 1960, that comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are regarded as the most influential band of all time and were integral to the developmen ...

would not play to a segregated audience in Jacksonville, Florida

Jacksonville is a city located on the Atlantic coast of northeast Florida, the most populous city proper in the state and is the List of United States cities by area, largest city by area in the contiguous United States as of 2020. It is the co ...

. City officials relented following this announcement."The Beatles banned segregated audiences, contract shows"BBC. Retrieved July 17, 2017 A contract for a 1965 Beatles concert at the

Cow Palace

The Cow Palace (originally the California State Livestock Pavilion) is an indoor arena located in Daly City, California, situated on the city's northern border with neighboring San Francisco. Because the border passes through the property, a por ...

in Daly City, California

Daly City () is the second most populous city in San Mateo County, California, United States, with population of 104,901 according to the 2020 census. Located in the San Francisco Bay Area, and immediately south of San Francisco (sharing its ...

, specifies that the band "not be required to perform in front of a segregated audience".

Despite all the legal changes that have taken place since the 1940s and especially in the 1960s (see Desegregation

Desegregation is the process of ending the separation of two groups, usually referring to races. Desegregation is typically measured by the index of dissimilarity, allowing researchers to determine whether desegregation efforts are having impact o ...

), the United States remains, to some degree, a segregated society, with housing patterns, school enrollment, church membership, employment opportunities, and even college admissions all reflecting significant ''de facto'' segregation. Supporters of affirmative action argue that the persistence of such disparities reflects either racial discrimination or the persistence of its effects.

'' Gates v. Collier'' was a case decided in federal court that brought an end to the trusty system and flagrant inmate abuse at the notorious Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman, Mississippi. In 1972 federal judge, William C. Keady found that Parchman Farm violated modern standards of decency. He ordered an immediate end to all unconstitutional conditions and practices. Racial segregation of inmates was abolished. And the trusty system, which allowed certain inmates to have power and control over others, was also abolished.

More recently, the disparity between the racial compositions of inmates in the American prison system has led to concerns that the U.S. Justice system furthers a "new apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

".

Scientific racism

The intellectual roots of ''Plessy v. Ferguson

''Plessy v. Ferguson'', 163 U.S. 537 (1896), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in which the Court ruled that racial segregation laws did not violate the U.S. Constitution as long as the facilities for each race were equal in qualit ...

'', the landmark United States Supreme Court decision which upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation, under the doctrine of "separate but equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law, according to which racial segregation did not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which nominally guaranteed "equal protec ...

", were partially tied to the scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies ...

of the era. The popular support of the decision was likely a result of the racist beliefs which were held by most whites at the time. Later, the court decision ''Brown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segrega ...

'' rejected the ideas of scientific racists about the need for segregation, especially in schools. Following that decision both scholarly and popular ideas of scientific racism played an important role in the attack and backlash that followed the court decision.

The ''Mankind Quarterly

''Mankind Quarterly'' is a peer-reviewed journal that has been described as a "cornerstone of the scientific racism establishment", a "white supremacist journal", and "a pseudo-scholarly outlet for promoting racial inequality". It covers phy ...

'' is a journal that has published scientific racism. It was founded in 1960, partly in response to the 1954 United States Supreme Court decision ''Brown v. Board of Education'', which ordered the desegregation of US schools. Many of the publication's contributors, publishers, and board of directors espouse academic hereditarianism

Hereditarianism is the doctrine or school of thought that heredity plays a significant role in determining human nature and character traits, such as intelligence and personality. Hereditarians believe in the power of genetics to explain human ch ...

. The publication is widely criticized for its extremist politics, anti-semitic bent and its support for scientific racism.

In the South

After the end of Reconstruction and the withdrawal of federal troops, which followed from the Compromise of 1877, the Democratic governments in the South instituted state laws to separate black and white racial groups, submitting African-Americans to ''de facto'' second-class citizenship and enforcing

After the end of Reconstruction and the withdrawal of federal troops, which followed from the Compromise of 1877, the Democratic governments in the South instituted state laws to separate black and white racial groups, submitting African-Americans to ''de facto'' second-class citizenship and enforcing white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

. Collectively, these state laws were called the Jim Crow system, after the name of a stereotypical 1830s black minstrel show character.Remembering Jim Crow– Minnesota Public Radio Sometimes, as in Florida's Constitution of 1885, segregation was mandated by state constitutions. Racial segregation became the law in most parts of the American South until the

Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

. These laws, known as Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

, forced segregation of facilities and services, prohibited intermarriage, and denied suffrage. Impacts included:

* Segregation of facilities included separate schools, hotels, bars, hospitals, toilets, parks, even telephone booths, and separate sections in libraries, cinemas, and restaurants, the latter often with separate ticket windows and counters.

** After Reconstruction, many southern states passed Jim crow laws and followed the "separate but equal" doctrine created during the Plessy vs Ferguson case. Segregated libraries under this system existed in most parts of the south. The East Henry Street Carnegie library in Savannah, built by African Americans during the segregation era in 1914 with help from the Carnegie foundation, is one example. Hundreds of segregated libraries existed across the United States prior to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. These libraries were often underfunded, understocked, and had fewer services than their white counterparts. Only during the landmark Brown vs Board was the acknowledgement that separate was never equal and that African Americans were not segregating by choice. During the Civil rights movement, several demonstrations and sit-ins were orchestrated by activist including nine Tugaloo College students who were arrested when they requested service from the all-white Jackson Public Library in Mississippi. Another example was the St. Helena Four, where four local teenagers made several attempts to use the Auburn Regional Library located in Greenburg, Louisiana. Police were typically called on these civil rights activists usually resulting in some form of intimidation or incarceration. Libraries in several states continued their segregation practices even after the "separate but equal" doctrine was overruled by the Civil Rights Act. In 1964 E.J. Josey, the first African American member of ALA, put forth a resolution preventing ALA officers and staff members to attend segregated state chapter meetings. The segregated states being targeted by this resolution were Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana. This resolution led to the integration of these state's libraries within a few years.

* Laws prohibited blacks from being present in certain locations. For example, blacks in 1939 were not allowed on the streets of Palm Beach, Florida after dark, unless required by their employment.

* State laws prohibiting interracial marriage ("miscegenation

Miscegenation ( ) is the interbreeding of people who are considered to be members of different races. The word, now usually considered pejorative, is derived from a combination of the Latin terms ''miscere'' ("to mix") and ''genus'' ("race") ...

") had been enforced throughout the South and in many Northern states since the Colonial era. During Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, such laws were repealed in Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Florida, Texas and South Carolina. In all these states such laws were reinstated after the Democratic "Redeemers

The Redeemers were a political coalition in the Southern United States during the Reconstruction Era that followed the Civil War. Redeemers were the Southern wing of the Democratic Party. They sought to regain their political power and enforce ...

" came to power. The Supreme Court declared such laws constitutional in 1883. This verdict was overturned only in 1967 by '' Loving v. Virginia''.

* The voting rights of blacks were systematically restricted or denied through suffrage laws, such as the introduction of poll taxes

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments f ...

and literacy tests. Loopholes, such as the grandfather clause

A grandfather clause, also known as grandfather policy, grandfathering, or grandfathered in, is a provision in which an old rule continues to apply to some existing situations while a new rule will apply to all future cases. Those exempt from t ...

and the understanding clause, protected the voting rights of white people who were unable to pay the tax or pass the literacy test. (See Senator Benjamin Tillman's open defense of this practice.) Only whites could vote in Democratic Party primary contests. Where and when black people did manage to vote in numbers, their votes were negated by systematic gerrymander

In representative democracies, gerrymandering (, originally ) is the political manipulation of electoral district boundaries with the intent to create undue advantage for a party, group, or socioeconomic class within the constituency. The m ...

of electoral boundaries.

* In theory the segregated facilities available for negroes were of the same quality as those available to whites, under the

* In theory the segregated facilities available for negroes were of the same quality as those available to whites, under the separate but equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law, according to which racial segregation did not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which nominally guaranteed "equal protec ...

doctrine. In practice this was rarely the case. For example, in Martin County, Florida

Martin County ( es, Condado de Martín, link=) is a county located in the Treasure Coast region of the state of Florida, in the United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 158,431. Its county seat is Stuart. Martin County is in t ...

, students at Stuart Training School "read second-hand books...that were discarded from their all-white counterparts at Stuart High School. They also wore secondhand basketball and football uniforms.... The students and their parents built the basketball court and sidewalks at the school without the help of the school board. 'We even put in wiring for lights along the sidewalk, but the school board never connected the electricity.'"

In the North

Formal segregation also existed in the North. Some neighborhoods were restricted to blacks and job opportunities were denied them by unions in, for example, the skilled building trades. Blacks who moved to the North in the Great Migration after World War I sometimes could live without the same degree of oppression experienced in the South, but the racism and discrimination still existed. The rapid influx of blacks during the Great Migration disturbed the racial balance within Northern and Western cities, exacerbating hostility between both blacks and whites in the two regions. Deed restrictions and

The rapid influx of blacks during the Great Migration disturbed the racial balance within Northern and Western cities, exacerbating hostility between both blacks and whites in the two regions. Deed restrictions and restrictive covenants

A covenant, in its most general sense and historical sense, is a solemn promise to engage in or refrain from a specified action. Under historical English common law, a covenant was distinguished from an ordinary contract by the presence of a se ...

became an important instrument for enforcing racial segregation in most towns and cities, becoming widespread in the 1920s. Such covenants were employed by many real estate developers

Real estate development, or property development, is a business process, encompassing activities that range from the renovation and re-lease of existing buildings to the purchase of raw land and the sale of developed land or parcels to others. R ...

to "protect" entire subdivisions

Subdivision may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Subdivision (metre), in music

* ''Subdivision'' (film), 2009

* "Subdivision", an episode of ''Prison Break'' (season 2)

* ''Subdivisions'' (EP), by Sinch, 2005

* "Subdivisions" (song), by Rush ...

, with the primary intent to keep "white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White o ...

" neighborhoods "white". Ninety percent of the housing projects built in the years following World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

were racially restricted by such covenants. Cities known for their widespread use of racial covenants include Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at t ...

, Milwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee ...

, Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

, Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest regio ...

, and St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

.

The Chicago suburb of Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

, for example, was made famous when Civil Rights advocate Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

led a march advocating open (race-unbiased) housing.

Within employment, economic opportunities for blacks were routed to the lowest-status and restrictive in potential mobility. In 1900 Reverend Matthew Anderson, speaking at the annual

Within employment, economic opportunities for blacks were routed to the lowest-status and restrictive in potential mobility. In 1900 Reverend Matthew Anderson, speaking at the annual Hampton Negro Conference

The Hampton Negro Conference was a series of conferences held between 1897 and 1912 hosted by the Hampton University, Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) in Hampton, Virginia. It brought together Black leaders from across the Southern Unite ...

in Virginia, said that "...the lines along most of the avenues of wage earning are more rigidly drawn in the North than in the South. There seems to be an apparent effort throughout the North, especially in the cities to debar the colored worker from all the avenues of higher remunerative labor, which makes it more difficult to improve his economic condition even than in the South." In the 1930s, job discrimination ended for many African Americans in the North, after the Congress of Industrial Organizations, one of America's lead labor unions at the time, agreed to integrate the union.

School segregation in the North was also a major issue. In Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, towns in the south of those states enforced school segregation, despite the fact that it was prohibited by state laws. Indiana also required school segregation by state law. During the 1940s, NAACP lawsuits quickly depleted segregation from the Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania and New Jersey southern areas. In 1949, Indiana officially repealed its school segregation law as well. The most common form of segregation in the northern states came from anti-miscegenation laws.

The state of Oregon went farther than even any of the Southern states, specifically excluding blacks from entering the state, or from owning property within it. School integration did not come about until the mid-1970s. As of 2017, the population of Oregon was about 2% black.

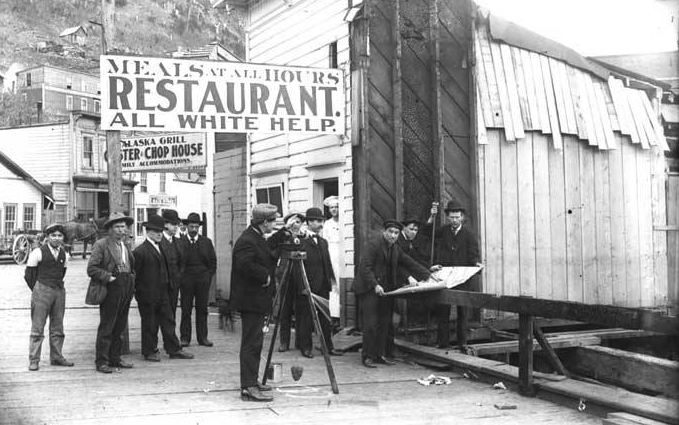

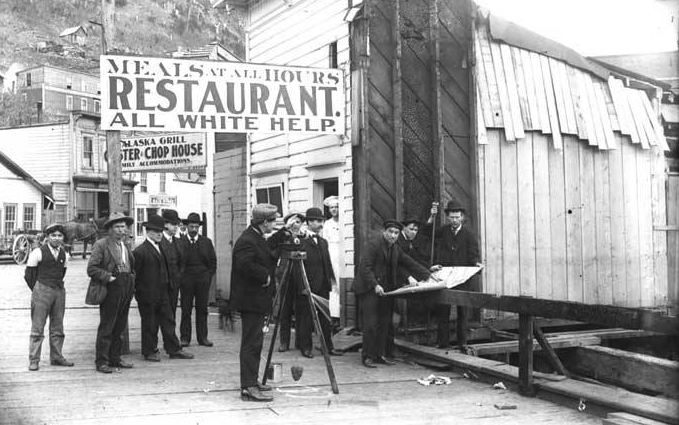

In Alaska

Racial segregation in

Racial segregation in Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S. ...

was primarily targeted at Alaska Natives. In 1905, the Nelson Act specified an educational system for whites and one for indigenous Alaskans. Public areas such as playgrounds, swimming pools, and theaters were also segregated. Groups such as the Alaska Native Brotherhood

The Alaska Native Brotherhood (ANB) and its counterpart, the Alaska Native Sisterhood (ANS), are two nonprofit organizations founded to address racism against Alaska Native peoples in Alaska. ANB was formed in 1912 and ANS founded three years lat ...

(ANB) staged boycotts of places that supported segregation. In 1941, Elizabeth Peratrovich

Elizabeth Peratrovich (née Elizabeth Jean Wanamaker, ; July 4, 1911December 1, 1958) was an American civil rights activist, Grand President of the Alaska Native Sisterhood, and member of the Tlingit nation who worked for equality on behalf of ...

(Tlingit

The Tlingit ( or ; also spelled Tlinkit) are indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. Their language is the Tlingit language (natively , pronounced ),

) and her husband argued to the governor of Alaska, Ernest Gruening, that segregation was "very Un-American." Gruening supported anti-discrimination laws and pushed for their passage. In 1944, Alberta Schenck ( Inupiaq) staged a sit-in in the whites-only section of a theater in Nome, Alaska. In 1945, the first anti-discrimination law in the United States, the Alaska Equal Rights Act, was passed in Alaska. The law made segregation illegal and banned signs that discriminate based on race.

Sports

Segregation insports in the United States

Sports are an important part of culture in the United States. Historically, the national sport has been baseball. However, in more recent decades, American football has been the most popular sport in terms of broadcast viewership audience. B ...

was also a major national issue. In 1900, just four years after the US Supreme Court separate but equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law, according to which racial segregation did not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which nominally guaranteed "equal protec ...

constitutional ruling, segregation was enforced in horse racing, a sport which had previously seen many African American jockeys win Triple Crown

Triple Crown may refer to:

Sports Horse racing

* Triple Crown of Thoroughbred Racing

* Triple Crown of Thoroughbred Racing (United States)

** Triple Crown Trophy

** Triple Crown Productions

* Canadian Triple Crown of Thoroughbred Racing

* Tri ...

and other major races. Widespread segregation also existed in bicycle and automobile racing. In 1890, segregation lessened for African-American track and field

Track and field is a sport that includes athletic contests based on running, jumping, and throwing skills. The name is derived from where the sport takes place, a running track and a grass field for the throwing and some of the jumping eve ...

athletes after various universities and colleges in the northern states agreed to integrate their track and field teams. Like track and field, soccer was another which experienced a low amount of segregation in the early days of segregation. Many colleges and universities in the northern states allowed African Americans to play on their football teams.

Segregation was also hardly enforced in boxing. In 1908, Jack Johnson became the first African American to win the World Heavyweight Title. Johnson's personal life (i.e. his publicly acknowledged relationships with white women) made him very unpopular among many Caucasians throughout the world. In 1937, when Joe Louis defeated German boxer Max Schmeling, the general American public embraced an African American as the World Heavyweight Champion.

In 1904, Charles Follis became the first African American to play for a professional football team, the Shelby Blues

The Shelby Blues were an American football team based in Shelby, Ohio. The team played in the Ohio League from 1900 to 1919. In 1920, when the Ohio League became the APFA (now known as the National Football League), the Blues did not join but conti ...

, and professional football leagues agreed to allow only a limited number of teams to be integrated. In 1933, the NFL, now the only major football league in the United States, reversed its limited integration policy and completely segregated the entire league. The NFL color barrier permanently broke in 1946, when the Los Angeles Rams signed Kenny Washington and Woody Strode

Woodrow Wilson Woolwine Strode (July 25, 1914 – December 31, 1994) was an American athlete and actor. He was a decathlete and football star who was one of the first Black American players in the National Football League in the postwar era. Aft ...

and the Cleveland Browns hired Marion Motley and Bill Willis.