The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the

German Reich

German ''Reich'' (lit. German Realm, German Empire, from german: Deutsches Reich, ) was the constitutional name for the German nation state that existed from 1871 to 1945. The ''Reich'' became understood as deriving its authority and sovereignty ...

, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a

constitutional

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princi ...

federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is also referred to, and unofficially proclaimed itself, as the German Republic (german: Deutsche Republik, link=no, label=none). The state's informal name is derived from the city of

Weimar, which hosted the

constituent assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

that established its government. In English, the republic was usually simply called "Germany", with "Weimar Republic" (a term introduced by

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

in 1929) not commonly used until the 1930s.

Following the devastation of the

First World War (1914–1918), Germany was exhausted and sued for peace in desperate circumstances. Awareness of imminent defeat sparked a

revolution, the

abdication

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ ...

of

Kaiser Wilhelm II, formal surrender

to the Allies, and the proclamation of the Weimar Republic on 9 November 1918.

In its initial years, grave problems beset the Republic, such as

hyperinflation and

political extremism

Extremism is "the quality or state of being extreme" or "the advocacy of extreme measures or views". The term is primarily used in a political or religious sense to refer to an ideology that is considered (by the speaker or by some implied share ...

, including political murders and two attempted

seizures of power by contending

paramilitaries

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

; internationally, it suffered isolation, reduced diplomatic standing, and contentious relationships with the great powers. By 1924, a great deal of monetary and political stability was restored, and the republic enjoyed relative prosperity for the next five years; this period, sometimes known as the

Golden Twenties, was characterised by significant cultural flourishing, social progress, and gradual improvement in foreign relations. Under the

Locarno Treaties of 1925, Germany moved toward normalising relations with its neighbours, recognising most territorial changes under the

Treaty of Versailles and committing to never go to war. The following year, it joined the

League of Nations, which marked its reintegration into the international community. Nevertheless, especially on the political right, there remained strong and widespread resentment against the treaty and those who had signed and supported it.

The

Great Depression of October 1929 severely impacted Germany's tenuous progress; high unemployment and subsequent social and political unrest led to the collapse of the coalition government. From March 1930 onwards, President

Paul von Hindenburg used

emergency powers to back

Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

s

Heinrich Brüning

Heinrich Aloysius Maria Elisabeth Brüning (; 26 November 1885 – 30 March 1970) was a German Centre Party politician and academic, who served as the chancellor of Germany during the Weimar Republic from 1930 to 1932.

A political scientis ...

,

Franz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, Erbsälzer zu Werl und Neuwerk (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German conservative politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and General Staff officer. He served as the chancellor of Germany in ...

and General

Kurt von Schleicher. The Great Depression, exacerbated by Brüning's policy of deflation, led to a greater surge in unemployment.

[Büttner, Ursula ''Weimar: die überforderte Republik'', Klett-Cotta, 2008, , p. 424] On 30 January 1933, Hindenburg appointed

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

as Chancellor to head a coalition government; Hitler's far-right

Nazi Party held two out of ten cabinet seats. Von Papen, as Vice-Chancellor and Hindenburg's confidant, was to serve as the ''

éminence grise

An ''éminence grise'' () or grey eminence is a powerful decision-maker or adviser who operates "behind the scenes", or in a non-public or unofficial capacity.

This phrase originally referred to François Leclerc du Tremblay, the right-hand man ...

'' who would keep Hitler under control; these intentions badly underestimated Hitler's political abilities. By the end of March 1933, the

Reichstag Fire Decree

The Reichstag Fire Decree (german: Reichstagsbrandverordnung) is the common name of the Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of People and State (german: Verordnung des Reichspräsidenten zum Schutz von Volk und Staat) issued by Ger ...

and the

Enabling Act of 1933 had used the perceived state of emergency to effectively grant the new Chancellor broad power to act outside parliamentary control.

Hitler promptly used these powers to thwart constitutional governance and suspend civil liberties, which brought about the swift collapse of democracy at the federal and state level, and the creation of a

one-party

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

dictatorship under his leadership.

Until the

end of World War II in Europe in 1945, the Nazis governed Germany under the pretense that all the extraordinary measures and laws they implemented were constitutional; notably, there was never an attempt to replace or substantially amend the

Weimar constitution. Nevertheless, Hitler's seizure of power (''

Machtergreifung'') had effectively ended the republic, replacing its constitutional framework with ''

Führerprinzip'', the principle that "the Führer's word is above all written law".

Name and symbols

The Weimar Republic is so called because

the assembly that adopted its constitution met at Weimar from 6 February 1919 to 11 August 1919, but this name only became mainstream after 1933.

Terminology

Between 1919 and 1933, no single name for the new state gained widespread acceptance, thus the old name was officially retained, although hardly anyone used it during the Weimar period.

To the right of the spectrum, the politically engaged rejected the new democratic model and were appalled to see the honour of the traditional word ''Reich'' associated with it.

[ as quoted in ] Zentrum, the Catholic Centre Party, favoured the term (German People's State), while on the moderate left Chancellor

Friedrich Ebert

Friedrich Ebert (; 4 February 187128 February 1925) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the first president of Germany from 1919 until his death in office in 1925.

Ebert was elected leader of the SPD on t ...

's

Social Democratic Party of Germany preferred (German Republic).

By the mid-1920s, most Germans referred to their government informally as the , but for many, especially on the right, the word "" was a painful reminder of a government structure that they believed had been imposed by foreign statesmen, along with the relocation of the seat of power to Weimar and the expulsion of

Kaiser Wilhelm in the wake of massive national humiliation.

The first recorded mention of the term (Republic of Weimar) came during a speech delivered by Adolf Hitler at a Nazi Party rally in Munich on 24 February 1929. A few weeks later, the term was first used again by Hitler in a newspaper article.

Only during the 1930s did the term become mainstream, both within and outside Germany.

According to historian

Richard J. Evans:

The continued use of the term 'German Empire', ''Deutsches Reich'', by the Weimar Republic ... conjured up an image among educated Germans that resonated far beyond the institutional structures Bismarck created: the successor to the Roman Empire; the vision of God's Empire here on earth; the universality of its claim to suzerainty; and a more prosaic but no less powerful sense, the concept of a German state that would include all German speakers in central Europe—'one People, one Reich, one Leader', as the Nazi slogan was to put it.

Flag and coat of arms

The old black-red-gold tricolor was named as the national flag in the

Weimar Constitution.

It was abolished in 1935 after the Nazi Party seized the power. The coat of arms was initially based on the ''Reichsadler'' introduced by the

Paulskirche Constitution of 1849, and announced in November 1911. In 1928, a new design by Karl-Tobias Schwab was adopted as national coat of arms, which was used until being replaced by Nazi's ''Reichsadler'' in 1935, and readopted by the

Federal Republic of Germany in 1950.

Armed forces

After the dissolution of the army of the former German Empire, known as the

''Deutsches Heer'' (simply "German Army") or the ''Reichsheer'' ("Army of the Realm") in 1918; Germany's military forces consisted of irregular

paramilitaries

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

, namely the various right-wing ''

Freikorps'' ("Free Corps") groups composed of veterans from the war. The ''Freikorps'' units were formally disbanded in 1920 (although continued to exist in underground groups), and on 1 January 1921, a new ''

Reichswehr'' (

figuratively; ''Defence of the realm'') was created.

The

Treaty of Versailles limited the size of the ''Reichswehr'' to 100,000 soldiers (consisting of seven infantry divisions and three cavalry divisions), 10 armoured cars and a navy (the ''

Reichsmarine

The ''Reichsmarine'' ( en, Realm Navy) was the name of the German Navy during the Weimar Republic and first two years of Nazi Germany. It was the naval branch of the '' Reichswehr'', existing from 1919 to 1935. In 1935, it became known as the ...

'') restricted to 36 ships in active service. No aircraft of any kind was allowed. The main advantage of this limitation, however, was that the ''Reichswehr'' could afford to pick the best recruits for service. However, with inefficient armour and no air support, the ''Reichswehr'' would have had limited combat abilities.

Privates were mainly recruited from the countryside, as it was believed that young men from cities were prone to socialist behaviour, which would fray the loyalty of the privates to their conservative officers.

Although technically in service of the republic, the army was predominantly officered by conservative reactionaries who were sympathetic to right-wing organisations.

Hans von Seeckt, the head of the ''

Reichswehr'', declared that the army was not loyal to the democratic republic, and would only defend it if it were in their interests. During the

Kapp Putsch for example, the army refused to fire upon the rebels. The vulgar and turbulent

SA was the ''Reichswehr's'' main opponent throughout its existence, openly seeking to absorb the army, and the army fired at them during the

Beer Hall Putsch

The Beer Hall Putsch, also known as the Munich Putsch,Dan Moorhouse, ed schoolshistory.org.uk, accessed 2008-05-31.Known in German as the or was a failed coup d'état by Nazi Party ( or NSDAP) leader Adolf Hitler, Erich Ludendorff and oth ...

. With the ascendance of the

SS, the ''Reichswehr'' took a softer line about the Nazis, as the SS presented itself as elitist, respectable, orderly, and busy reforming and dominating the police rather than the army.

In 1935, two years after

Adolf Hitler's rise to power

Adolf Hitler's rise to power began in the newly established Weimar Republic in September 1919 when Hitler joined the '' Deutsche Arbeiterpartei'' (DAP; German Workers' Party). He rose to a place of prominence in the early years of the party. Be ...

, the ''

Reichswehr'' was renamed the ''

Wehrmacht'' (Defense Force). The ''Wehrmacht'' was the unified armed forces of the Nazi regime, which consisted of the

''Heer'' (army), the ''

Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''

Luftwaffe'' (air force).

History

Background

Hostilities in

World War I took place between 28 July 1914 and 11 November 1918, during which over 70 million

military personnel

Military personnel are members of the state's armed forces. Their roles, pay, and obligations differ according to their military branch (army, navy, marines, air force, space force, and coast guard), rank (officer, non-commissioned officer, or e ...

were mobilised; the war ended with 20 million military and civilian deaths

—exclusive of fatalities from the

1918 Spanish flu pandemic

This year is noted for the end of the First World War, on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, as well as for the Spanish flu pandemic that killed 50–100 million people worldwide.

Events

Below, the events ...

, which accounted for millions more—making it one of the largest and deadliest wars in history.

After four years of war on multiple fronts in Europe and around the world, the final

Allied offensive began in August 1918, and the position of Germany and the Central Powers deteriorated,

leading them to sue for peace. Initial offers were rejected by the Allied Powers, and Germany's position became more desperate. Awareness of impending military defeat sparked the

German Revolution, proclamation of a republic on 9 November 1918,

the abdication of

Kaiser Wilhelm II,

and German surrender, marking the end of

Imperial Germany and the beginning of the Weimar Republic.

November Revolution (1918–1919)

In October 1918, the

constitution of the German Empire was reformed to give more powers to the elected parliament. On 29 October,

rebellion broke out in

Kiel among sailors. There, sailors, soldiers, and workers began electing

Workers' and Soldiers' Councils (''Arbeiter und Soldatenräte'') modelled after the

Soviets of the

Russian Revolution of 1917. The revolution spread throughout Germany, and participants seized military and civil powers in individual cities. The power takeover was achieved everywhere without loss of life.

At the time, the Socialist movement which represented mostly labourers was split among two major left-wing parties: the

Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD), which called for immediate peace

negotiations and favoured a soviet-style command economy, and the

Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) also known as "Majority" Social Democratic Party of Germany (MSPD), which supported the war effort and favoured a

parliamentary system. The rebellion caused great fear in the establishment and in the middle classes because of the

Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

-style aspirations of the councils. To centrist and conservative citizens, the country looked to be on the verge of a communist revolution.

By 7 November, the revolution had reached

Munich, resulting in King

Ludwig III of Bavaria fleeing. The MSPD decided to make use of their support at the grassroots and put themselves at the front of the movement, demanding that Kaiser

Wilhelm II abdicate. When he refused,

Prince Max of Baden

Maximilian, Margrave of Baden (''Maximilian Alexander Friedrich Wilhelm''; 10 July 1867 – 6 November 1929),Almanach de Gotha. ''Haus Baden (Maison de Bade)''. Justus Perthes, Gotha, 1944, p. 18, (French). also known as Max von Baden, was a Ger ...

simply announced that he had done so and frantically attempted to establish a

regency

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state ''pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy, ...

under another member of the

House of Hohenzollern.

Gustav Noske, a self-appointed military expert in the MSPD, was sent to Kiel to prevent any further unrest and took on the task of controlling the mutinous sailors and their supporters in the Kiel barracks. The sailors and soldiers, inexperienced in matters of revolutionary combat, welcomed him as an experienced politician and allowed him to negotiate a settlement, thus defusing the initial anger of the revolutionaries in uniform.

On 9 November 1918, the

"German Republic" was proclaimed by MSPD member

Philipp Scheidemann at the

''Reichstag'' building in Berlin, to the fury of

Friedrich Ebert

Friedrich Ebert (; 4 February 187128 February 1925) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the first president of Germany from 1919 until his death in office in 1925.

Ebert was elected leader of the SPD on t ...

, the leader of the MSPD, who thought that the question of monarchy or republic should be answered by a national assembly. Two hours later, a

"Free Socialist Republic" was proclaimed, away, at the ''

Berliner Stadtschloss

The Berlin Palace (german: Berliner Schloss), formally the Royal Palace (german: Königliches Schloss), on the Museum Island in the Mitte area of Berlin, was the main residence of the House of Hohenzollern from 1443 to 1918. Expanded by order of ...

''. The proclamation was issued by

Karl Liebknecht

Karl Paul August Friedrich Liebknecht (; 13 August 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a German socialist and anti-militarist. A member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) beginning in 1900, he was one of its deputies in the Reichstag from ...

, co-leader (with

Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg (; ; pl, Róża Luksemburg or ; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Polish and naturalised-German revolutionary socialist, Marxist philosopher and anti-war activist. Successively, she was a member of the Proletariat part ...

) of the communist Spartakusbund (

Spartacus League

The Spartacus League (German: ''Spartakusbund'') was a Marxist revolutionary movement organized in Germany during World War I. It was founded in August 1914 as the "International Group" by Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, Clara Zetkin, and ...

), a group of a few hundred supporters of the Russian Revolution that had allied itself with the USPD in 1917. In a legally questionable act, Imperial Chancellor (''Reichskanzler'') Prince Max of Baden transferred his powers to Friedrich Ebert, who, shattered by the monarchy's fall, reluctantly accepted. In view of the mass support for more radical reforms among the workers' councils, a

coalition government called "

Council of the People's Deputies" (''Rat der Volksbeauftragten'') was established, consisting of three MSPD and three USPD members. Led by Ebert for the MSPD and

Hugo Haase

Hugo Haase (29 September 1863 – 7 November 1919) was a German socialist politician, jurist and pacifist. With Friedrich Ebert, he co-chaired of the Council of the People's Deputies after the German Revolution of 1918–19.

Early life

Hugo Haas ...

for the USPD it sought to act as a provisional cabinet of ministers. But the power question was unanswered. Although the new government was confirmed by the Berlin worker and soldier council, it was opposed by the Spartacus League.

On 11 November 1918,

an armistice was signed at Compiègne by German representatives. It effectively ended military operations between

the Allies

Alliance, Allies is a term referring to individuals, groups or nations that have joined together in an association for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose.

Allies may also refer to:

* Allies of World War I

* Allies of World War II

* F ...

and Germany. It amounted to German capitulation, without any concessions by the Allies; the naval blockade would continue until complete peace terms were agreed.

From November 1918 to January 1919, Germany was governed by the "Council of the People's Deputies", under the leadership of Ebert and Haase. The Council issued a large number of decrees that radically shifted German policies. It introduced the

eight-hour workday, domestic labour reform, works councils, agricultural labour reform, right of civil-service associations, local municipality social welfare relief (split between ''Reich'' and States) and national health insurance, reinstatement of demobilised workers, protection from arbitrary dismissal with appeal as a right, regulated wage agreement, and universal suffrage from 20 years of age in all types of elections—local and national. Ebert called for a "National Congress of Councils" (''Reichsrätekongress''), which took place from 16 to 20 December 1918, and in which the MSPD had the majority. Thus, Ebert was able to institute elections for a provisional National Assembly that would be given the task of writing a democratic constitution for parliamentary government, marginalising the movement that called for a socialist republic.

To ensure his fledgling government maintained control over the country, Ebert made an agreement with the OHL, now led by Ludendorff's successor General

Wilhelm Groener. The '

Ebert–Groener pact' stipulated that the government would not attempt to reform the army so long as the army swore to protect the state. On the one hand, this agreement symbolised the acceptance of the new government by the military, assuaging concern among the middle classes; on the other hand, it was thought contrary to working-class interests by left wing social democrats and communists and was also opposed by the far right who believed democracy would make Germany weaker. The new ''Reichswehr'' armed forces, limited by the

Treaty of Versailles to 100,000 army soldiers and 15,000 sailors, remained fully under the control of the German

officer class, despite their nominal re-organisation.

The Executive Council of the Workers' and Soldiers' Councils, a coalition that included Majority Socialists, Independent Socialists, workers, and soldiers, implemented a programme of progressive social change, introducing reforms such as the eight-hour workday, the releasing of political prisoners, the abolition of press censorship, increases in workers' old-age, sick and unemployment benefits, and the bestowing upon labour the unrestricted right to organise into unions.

A number of other reforms were carried out in Germany during the revolutionary period. It was made harder for estates to sack workers and prevent them from leaving when they wanted to; under the Provisional Act for Agricultural Labour of 23 November 1918 the normal period of notice for management, and for most resident labourers, was set at six weeks. In addition, a supplementary directive of December 1918 specified that female (and child) workers were entitled to a fifteen-minute break if they worked between four and six hours, thirty minutes for workdays lasting six to eight hours, and one hour for longer days. A decree on 23 December 1918 established committees (composed of workers' representatives "in their relation to the employer") to safeguard the rights of workers. The right to bargain collectively was also established, while it was made obligatory "to elect workers' committees on estates and establish conciliation committees". A decree on 3 February 1919 removed the right of employers to acquire exemption for domestic servants and agricultural workers.

With the ''Verordnung'' of 3 February 1919, the Ebert government reintroduced the original structure of the health insurance boards according to an 1883 law, with one-third employers and two-thirds members (i.e. workers). From 28 June 1919 health insurance committees became elected by workers themselves. The Provisional Order of January 1919 concerning agricultural labour conditions fixed 2,900 hours as a maximum per year, distributed as eight, ten, and eleven hours per day in four-monthly periods. A code of January 1919 bestowed upon land-labourers the same legal rights that industrial workers enjoyed, while a bill ratified that same year obliged the States to set up agricultural settlement associations which, as noted by

Volker Berghahn

Volker Rolf Berghahn (born 15 February 1938) is a historian of German and modern European history at Columbia University. His research interests have included the fin de siècle period in Europe, the origins of World War I, and German-American r ...

, "were endowed with the priority right of purchase of farms beyond a specified size". In addition, undemocratic public institutions were abolished, involving, as noted by one writer, the disappearance "of the Prussian Upper House, the former Prussian Lower House that had been elected in accordance with the

three-class suffrage, and the municipal councils that were also elected on the class vote".

A rift developed between the MSPD and USPD after Ebert called upon the

OHL (Supreme Army Command) for troops to put down a

mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among member ...

by a leftist military unit on 23/24 December 1918, in which members of the ''Volksmarinedivision'' (People's Army Division) had captured the city's garrison commander

Otto Wels

Otto Wels (15 September 1873 – 16 September 1939) was a German politician who served as a member of parliament from 1912 to 1933 and as the chairman of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) from 1919 until his death in 1939. His 1933 sp ...

and occupied the ''Reichskanzlei'' (Reich Chancellery) where the "Council of the People's Deputies" was situated. The ensuing street fighting left several dead and injured on both sides. The USPD leaders were outraged by what they believed was treachery by the MSPD, which, in their view, had joined with the anti-communist military to suppress the revolution. Thus, the USPD left the "Council of the People's Deputies" after only seven weeks. On 30 December, the split deepened when the

Communist Party of Germany (KPD) was formed out of a number of radical left-wing groups, including the left wing of the USPD and the

Spartacus League

The Spartacus League (German: ''Spartakusbund'') was a Marxist revolutionary movement organized in Germany during World War I. It was founded in August 1914 as the "International Group" by Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, Clara Zetkin, and ...

group.

In January, the Spartacus League and others in the streets of Berlin made more armed attempts to establish communism, known as the

Spartacist uprising

The Spartacist uprising (German: ), also known as the January uprising (), was a general strike and the accompanying armed struggles that took place in Berlin from 5 to 12 January 1919. It occurred in connection with the November Revoluti ...

. Those attempts were put down by paramilitary ''

Freikorps'' units consisting of volunteer soldiers. Bloody street fights culminated in the beating and shooting deaths of

Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg (; ; pl, Róża Luksemburg or ; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Polish and naturalised-German revolutionary socialist, Marxist philosopher and anti-war activist. Successively, she was a member of the Proletariat part ...

and

Karl Liebknecht

Karl Paul August Friedrich Liebknecht (; 13 August 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a German socialist and anti-militarist. A member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) beginning in 1900, he was one of its deputies in the Reichstag from ...

after their arrests on 15 January. With the affirmation of Ebert, those responsible were not tried before a

court-martial, leading to lenient sentences, which made Ebert unpopular among radical leftists.

The National Assembly elections took place on 19 January 1919; it was the first time women were allowed to vote. In this time, the radical left-wing parties, including the USPD and KPD, were barely able to get themselves organised, leading to a solid majority of seats for the MSPD moderate forces. To avoid the ongoing fights in Berlin, the National Assembly convened in the city of

Weimar, giving the future Republic its unofficial name. The

Weimar Constitution created a republic under a

parliamentary republic system with the ''Reichstag'' elected by

proportional representation. The democratic parties obtained a solid 80% of the vote.

During the debates in Weimar, fighting continued. A

Soviet republic was declared in

Munich but quickly put down by ''Freikorps'' and remnants of the regular army. The fall of the

Munich Soviet Republic

The Bavarian Soviet Republic, or Munich Soviet Republic (german: Räterepublik Baiern, Münchner Räterepublik),Hollander, Neil (2013) ''Elusive Dove: The Search for Peace During World War I''. McFarland. p.283, note 269. was a short-lived unre ...

to these units, many of which were situated on the extreme right, resulted in the growth of far-right movements and organisations in

Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

, including

Organisation Consul

Organisation Consul (O.C.) was an ultra-nationalist and anti-Semitic terrorist organization that operated in the Weimar Republic from 1920 to 1922. It was formed by members of the disbanded Freikorps group Marine Brigade Ehrhardt and was respons ...

, the

Nazi Party, and societies of exiled Russian Monarchists. Sporadic fighting continued to flare up around the country. In eastern provinces, forces loyal to Germany's fallen Monarchy fought the republic, while militias of Polish nationalists fought for independence:

Great Poland Uprising in

Provinz Posen

The Province of Posen (german: Provinz Posen, pl, Prowincja Poznańska) was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1848 to 1920. Posen was established in 1848 following the Greater Poland Uprising as a successor to the Grand Duchy of Posen, w ...

and three

Silesian uprisings in

Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( pl, Górny Śląsk; szl, Gůrny Ślůnsk, Gōrny Ślōnsk; cs, Horní Slezsko; german: Oberschlesien; Silesian German: ; la, Silesia Superior) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, locate ...

.

Germany lost the war because the country ran out of allies and its economic resources were running out; support among the population began to crumble in 1916 and by mid-1918 there was support for the war only among the die-hard monarchists and conservatives. The decisive blow came with the entry of the United States into the conflict, which made its vast industrial resources available to the beleaguered Allies. By late summer 1918, the German reserves were exhausted while fresh American troops arrived in France at the rate of 10,000 a day. Retreat and defeat were at hand, and the Army told the Kaiser to abdicate for it could no longer support him. Although in retreat, the German armies were still on French and Belgian territory when the war ended on 11 November. Ludendorf and Hindenburg soon proclaimed that it was the defeatism of the civilian population that had made defeat inevitable. The die-hard nationalists then blamed the civilians for betraying the army and the surrender. This was the "

stab-in-the-back myth

The stab-in-the-back myth (, , ) was an antisemitic conspiracy theory that was widely believed and promulgated in Germany after 1918. It maintained that the Imperial German Army did not lose World War I on the battlefield, but was instead ...

" that was unceasingly propagated by the right in the 1920s and ensured that many monarchists and conservatives would refuse to support the government of what they called the "November criminals".

Years of crisis (1919–1923)

Burden from the First World War

In the four years following the First World War, the situation for German civilians remained dire. The severe food shortages improved little to none up until 1923. Many German civilians expected life to return to prewar normality following the removal of the naval blockade in June 1919. Instead, the struggles induced by the First World War persisted for the decade following. Throughout the war German officials made rash decisions to combat the growing hunger of the nation, most of which were highly unsuccessful. Examples include the nationwide pig slaughter,

Schweinemord, in 1915. The rationale behind exterminating the population of swine was to decrease the use of potatoes and turnips for animal consumption, transitioning all foods toward human consumption.

In 1922, now three years after the German signing of the Treaty of Versailles, meat consumption in the country had not increased since the war era. 22 kg per person per year was still less than half of the 52 kg statistic in 1913, before the onset of the war. German citizens felt the food shortages even deeper than during the war, because the reality of the nation contrasted so starkly with their expectations. The burdens of the First World War lightened little in the immediate years following, and with the onset of the Treaty of Versailles, coupled by mass inflation, Germany still remained in a crisis. The continuity of pain showed the Weimar authority in a negative light, and public opinion was one of the main sources behind its failure.

Treaty of Versailles

The growing post-war economic crisis was a result of lost pre-war industrial exports, the loss of supplies in raw materials and foodstuffs due to the continental blockade, the loss of the colonies, and worsening debt balances, exacerbated by an exorbitant issue of promissory notes raising money to pay for the war. Military-industrial activity had almost ceased, although controlled demobilisation kept unemployment at around one million. In part, the economic losses can also be attributed to the Allied blockade of Germany until the Treaty of Versailles.

The Allies permitted only low import levels of goods that most Germans could not afford. After four years of war and famine, many German workers were exhausted, physically impaired and discouraged. Millions were disenchanted with what they considered capitalism and hoping for a new era. Meanwhile, the currency depreciated, and would continue to depreciate following the French invasion of the Ruhr.

The treaty was signed 28 June 1919 and is easily divided into four categories: territorial issues, disarmament demands, reparations, and assignment of guilt. The German colonial empire was stripped and given over to Allied forces. The greater blow to Germans however was that they were forced to give up the territory of Alsace-Lorraine. Many German borderlands were demilitarised and allowed to self-determine. The German military was forced to have no more than 100,000 men with only 4,000 officers. Germany was forced to destroy all its fortifications in the West and was prohibited from having an air force, tanks, poison gas, and heavy artillery. Many ships were scuttled, and submarines and dreadnoughts were prohibited. Germany was forced under Article 235 to pay 20 billion gold marks, about 4.5 billion dollars by 1921. Article 231 placed Germany and her allies with responsibility for causing all the loss and damage suffered by the Allies. While Article 235 angered many Germans, no part of the treaty was more fought over than Article 231.

The German peace delegation in France signed the Treaty of Versailles, accepting mass reductions of the German military, the prospect of substantial war reparations payments to the victorious allies, and the controversial "

War Guilt Clause

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

". Explaining the rise of extreme nationalist movements in Germany shortly after the war, British historian

Ian Kershaw

Sir Ian Kershaw (born 29 April 1943) is an English historian whose work has chiefly focused on the social history of 20th-century Germany. He is regarded by many as one of the world's leading experts on Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany, and is pa ...

points to the "national disgrace" that was "felt throughout Germany at the humiliating terms imposed by the victorious Allies and reflected in the Versailles Treaty...with its confiscation of territory on the eastern border and even more so its 'guilt clause'."

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

repeatedly blamed the republic and its democracy for accepting the oppressive terms of this treaty. The Republic's first ''

Reichspräsident'' ("Reich President"),

Friedrich Ebert

Friedrich Ebert (; 4 February 187128 February 1925) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the first president of Germany from 1919 until his death in office in 1925.

Ebert was elected leader of the SPD on t ...

of the SPD, signed the new German constitution into law on 11 August 1919.

The new post-World War Germany, stripped of all colonies, became 13% smaller in its European territory than its imperial predecessor. Of these losses, a large proportion consisted of provinces that were originally Polish, and the

Imperial Territory of Alsace–Lorraine, seized by Germany in 1870, and where Germans constituted a majority within the

Alsatian portion of said imperial province and also within half of

Lorraine

Lorraine , also , , ; Lorrain: ''Louréne''; Lorraine Franconian: ''Lottringe''; german: Lothringen ; lb, Loutrengen; nl, Lotharingen is a cultural and historical region in Northeastern France, now located in the administrative region of G ...

.

Allied Rhineland occupation

The occupation of the

Rhineland took place following the

Armistice with Germany

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices ...

of 11 November 1918. The occupying armies consisted of

American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

,

Belgian,

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

and

French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

forces.

In 1920, under massive French pressure, the

Saar

Saar or SAAR has several meanings:

People Given name

* Saar Boubacar (born 1951), Senegalese professional football player

* Saar Ganor, Israeli archaeologist

* Saar Klein (born 1967), American film editor

Surname

* Ain Saar (born 1968), E ...

was separated from the Rhine Province and administered by the

League of Nations until a plebiscite in 1935, when the region was returned to the ''Deutsches Reich''. At the same time in 1920, the districts of

Eupen

Eupen (, ; ; formerly ) is the capital of German-speaking Community of Belgium and is a city and municipality in the Belgian province of Liège, from the German border (Aachen), from the Dutch border (Maastricht) and from the "High Fens" ...

and

Malmedy

Malmedy (; german: Malmünd, ; wa, Måmdiy) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Liège, Belgium.

On January 1, 2018, Malmedy had a total population of 12,654. The total area is 99.96 km2 which gives a popula ...

were transferred to Belgium (see

German-Speaking Community of Belgium

The German-speaking Community (german: links=no, Deutschsprachige Gemeinschaft, or DG; french: links=no, Communauté germanophone; nl, links=no, Duitstalige Gemeenschap), since 2017 also known as East Belgium (german: links=no, Ostbelgien), is ...

). Shortly after, France completely occupied the Rhineland, strictly controlling all important industrial areas.

Reparations

The actual amount of reparations that Germany was obliged to pay out was not the 132 billion marks decided in the London Schedule of 1921 but rather the 50 billion marks stipulated in the A and B Bonds. Historian Sally Marks says the 112 billion marks in "C bonds" were entirely chimerical—a device to fool the public into thinking Germany would pay much more. The actual total payout from 1920 to 1931 (when payments were suspended indefinitely) was 20 billion

marks

Marks may refer to:

Business

* Mark's, a Canadian retail chain

* Marks & Spencer, a British retail chain

* Collective trade marks, trademarks owned by an organisation for the benefit of its members

* Marks & Co, the inspiration for the novel '' ...

, worth about US$5 billion or £1 billion

stg. 12.5 billion was cash that came mostly from loans from New York bankers. The rest was goods such as coal and chemicals, or from assets like railway equipment. The reparations bill was fixed in 1921 on the basis of a German capacity to pay, not on the basis of Allied claims. The highly publicised rhetoric of 1919 about paying for all the damages and all the veterans' benefits was irrelevant for the total, but it did determine how the recipients spent their share. Germany owed reparations chiefly to France, Britain, Italy and Belgium; the US Treasury received $100 million.

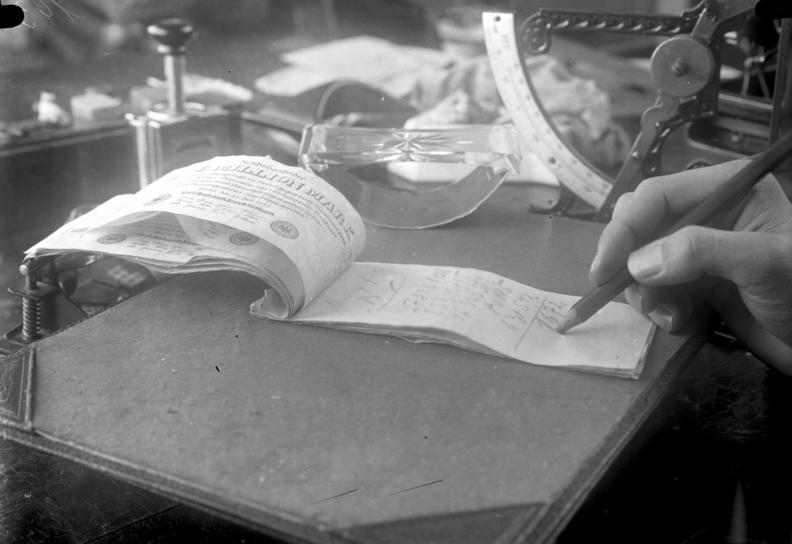

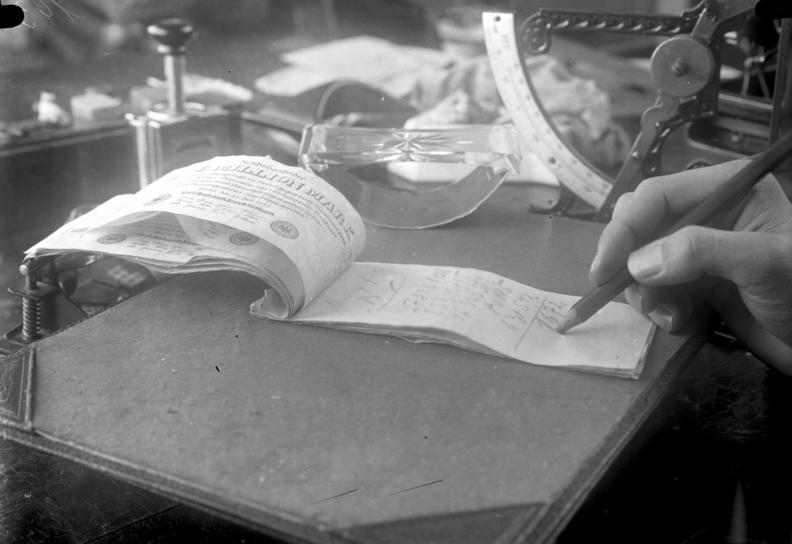

Hyperinflation

In the early post-war years, inflation was growing at an alarming rate, but the government simply printed more currency to pay debts. By 1923, the Republic claimed it could no longer afford the

reparations

Reparation(s) may refer to:

Christianity

* Restitution (theology), the Christian doctrine calling for reparation

* Acts of reparation, prayers for repairing the damages of sin

History

*War reparations

**World War I reparations, made from ...

payments required by the Versailles Treaty, and the government defaulted on some payments. In response, French and Belgian troops

occupied the Ruhr region, Germany's most productive industrial region at the time, taking control of most mining and manufacturing companies in January 1923. Strikes were called, and passive resistance was encouraged. These strikes lasted eight months, further damaging both the economy and society.

The strike prevented some goods from being produced, but one industrialist,

Hugo Stinnes, was able to create a vast empire out of bankrupt companies. Because the production costs in Germany were falling almost hourly, the prices for German products were unbeatable. Stinnes made sure that he was paid in dollars, which meant that by mid-1923, his industrial empire was worth more than the entire German economy. By the end of the year, over two hundred factories were working full-time to produce paper for the spiraling bank note production. Stinnes' empire collapsed when the government-sponsored inflation was stopped in November 1923.

In 1919, one loaf of bread cost 1 mark; by 1923, the same loaf of bread cost 100 billion marks.

Since striking workers were paid benefits by the state, much additional currency was printed, fuelling a period of

hyperinflation. The

1920s German inflation started when Germany had no goods to trade. The government printed money to deal with the crisis; this meant payments within Germany were made with worthless paper money, and helped formerly great industrialists to pay back their own loans. This also led to pay raises for workers and for businessmen who wanted to profit from it. Circulation of money rocketed, and soon banknotes were being overprinted to a thousand times their nominal value and every town produced its own promissory notes; many banks and industrial firms did the same.

The value of the ''

Papiermark'' had declined from 4.2 marks per U.S. dollar in 1914 to one million per dollar by August 1923. This led to further criticism of the Republic. On 15 November 1923, a new currency, the ''

Rentenmark'' (RM), was introduced by Stresemann at the rate of one

trillion

''Trillion'' is a number with two distinct definitions:

*1,000,000,000,000, i.e. one million million, or (ten to the twelfth power), as defined on the short scale. This is now the meaning in both American and British English.

* 1,000,000,000,00 ...

(1,000,000,000,000) ''Papiermark'' for one ''Rentenmark'', an action known as

redenomination. At that time, one U.S. dollar was equal to ''RM'' 4.20. Reparation payments were resumed, and the Ruhr was returned to Germany under the

Locarno Treaties, which defined the borders between Germany, France, and Belgium.

War guilt question

In the wake of the Treaty of Versailles which placed the responsibility for the outbreak of the war entirely on Germany and imposed crushing reparations upon Germany because of it, the question of German war guilt became a central point of debate in Germany both among politicians and historians, and also among the general public. The war guilt question pervaded the entire history of the Weimar Republic. Weimar embodied this debate until its demise, after which it was subsequently taken up as a campaign argument by the Nazi Party. This debate also took place in other countries involved in the conflict, such as in the

French Third Republic and the United Kingdom.

Entire organizations were formed in Germany chiefly to consider this question, including the

War Guilt Section

The war guilt question (german: Kriegsschuldfrage) is the public debate that took place in Germany for the most part during the Weimar Republic, to establish Germany's share of responsibility in the causes of the First World War. Structured i ...

() and the

Center for the Study of the Causes of the War (); existing institutions such as the

Potsdam Reichsarchiv spent significant resources researching or propagandizing about it.

While the war guilt question made it possible to investigate the deep-rooted

causes of the First World War

The identification of the causes of World War I remains controversial. World War I began in the Balkans on July 28, 1914, and hostilities ended on November 11, 1918, leaving 17 million dead and 25 million wounded. Moreover, the Russian Civi ...

, although not without provoking a great deal of controversy, it also made it possible to identify other aspects of the conflict, such as the role of the masses and the question of Germany's special path to democracy, the ''

Sonderweg''.

The war guilt debate motivated numerous historians such as

Hans Delbrück

Hans Gottlieb Leopold Delbrück (; 11 November 1848 – 14 July 1929) was a German historian. Delbrück was one of the first modern military historians, basing his method of research on the critical examination of ancient sources, using auxiliary ...

,

Wolfgang J. Mommsen, and

Gerhard Hirschfeld

Gerhard Hirschfeld (born 19 September 1946 in Plettenberg, Germany) is a German historian and author. He was director (between 1989-2011) of the Stuttgart-based Bibliothek für Zeitgeschichte / Library of Contemporary History, and has been a p ...

to take part. In 1961, German historian Fritz Fischer published ''

Germany's Aims in the First World War'', in which he argued that the German government had an expansionist foreign policy and had started a war of aggression in 1914. Fischer's thesis ignited a furious debate in Germany, which became known as the

Fischer controversy.

A century after the original events, this debate continues among historians into the 21st century. The main outlines of the debate include: how much room to maneuver was available diplomatically and politically; the inevitable consequences of pre-war armament policies; the role of domestic policy and social and economic tensions in the foreign relations of the states involved; the role of public opinion and their experience of war in the face of organized propaganda; the role of economic interests and top military commanders in torpedoing deescalation and peace negotiations; the theory; and the long-term trends which tend to contextualize the First World War as a condition or preparation for the Second, such as

Raymond Aron

Raymond Claude Ferdinand Aron (; 14 March 1905 – 17 October 1983) was a French philosopher, sociologist, political scientist, historian and journalist, one of France's most prominent thinkers of the 20th century.

Aron is best known for his 19 ...

who views the two world wars as the new

Thirty Years' War, a theory reprised by Enzo Traverso in his work.

Political turmoil: political murders, and attempted power seizures

The Republic was soon under attack from both

left- and right-wing sources. The radical left accused the ruling Social Democrats of having betrayed the ideals of the workers' movement by preventing a communist revolution and sought to overthrow the Republic to do so themselves. Various right-wing sources opposed any democratic system, preferring an authoritarian monarchy like the German Empire. To further undermine the Republic's credibility, some right-wingers (especially certain members of the former

officer corps) also blamed an

alleged conspiracy of Socialists and Jews for Germany's defeat in the First World War.

In the next five years, the central government, assured of the support of the Reichswehr, dealt severely with the occasional outbreaks of violence in Germany's large cities. The left claimed that the Social Democrats had betrayed the ideals of the revolution, while the army and the government-financed ''Freikorps'' committed hundreds of acts of gratuitous violence against striking workers.

The first challenge to the Weimar Republic came when a group of communists and anarchists took over the

Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

n government in

Munich and declared the creation of the

Bavarian Soviet Republic

The Bavarian Soviet Republic, or Munich Soviet Republic (german: Räterepublik Baiern, Münchner Räterepublik),Hollander, Neil (2013) ''Elusive Dove: The Search for Peace During World War I''. McFarland. p.283, note 269. was a short-lived unre ...

. The uprising was brutally attacked by ''

Freikorps'', which consisted mainly of ex-soldiers dismissed from the army and who were well-paid to put down forces of the Far Left. The ''Freikorps'' was an army outside the control of the government, but they were in close contact with their allies in the Reichswehr.

On 13 March 1920 during the

Kapp Putsch, 12,000 ''Freikorps'' soldiers occupied Berlin and installed

Wolfgang Kapp

Wolfgang Kapp (24 July 1858 – 12 June 1922) was a German civil servant and journalist. A strict nationalist, he is best known for being the leader of the Kapp Putsch.

Early life

Kapp was born in New York City where his father Friedrich Kapp, ...

, a right-wing journalist, as chancellor. The national government fled to

Stuttgart and called for a

general strike against the putsch. The strike meant that no "official" pronouncements could be published, and with the civil service out on strike, the Kapp government collapsed after only four days on 17 March.

Inspired by the general strikes, a workers'

uprising

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

began in the

Ruhr region

The Ruhr ( ; german: Ruhrgebiet , also ''Ruhrpott'' ), also referred to as the Ruhr area, sometimes Ruhr district, Ruhr region, or Ruhr valley, is a polycentric urban area in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. With a population density of 2,800/k ...

when 50,000 people formed a "Red Army" and took control of the province. The regular army and the ''Freikorps'' ended the uprising on their own authority. The rebels were campaigning for an extension of the plans to nationalise major industries and supported the national government, but the SPD leaders did not want to lend support to the growing USPD, who favoured the establishment of a socialist regime. The repression of an uprising of SPD supporters by the reactionary forces in the ''Freikorps'' on the instructions of the SPD ministers was to become a major source of conflict within the socialist movement and thus contributed to the weakening of the only group that could have withstood the Nazi movement. Other rebellions were put down in March 1921 in

Saxony and

Hamburg.

One of the manifestations of the sharp political polarisation that had occurred were the right-wing motivated assassinations of important representatives of the young republic. In August 1921, Finance Minister

Matthias Erzberger

Matthias Erzberger (20 September 1875 – 26 August 1921) was a German writer and politician (Centre Party), the minister of Finance from 1919 to 1920.

Prominent in the Catholic Centre Party, he spoke out against World War I from 1917 and as ...

and Foreign Minister

Walther Rathenau

Walther Rathenau (29 September 1867 – 24 June 1922) was a German industrialist, writer and liberal politician.

During the First World War of 1914–1918 he was involved in the organization of the German war economy. After the war, Rathenau s ...

were murdered by members of the

Organisation Consul

Organisation Consul (O.C.) was an ultra-nationalist and anti-Semitic terrorist organization that operated in the Weimar Republic from 1920 to 1922. It was formed by members of the disbanded Freikorps group Marine Brigade Ehrhardt and was respons ...

. While Erzberger was attacked for signing the armistice agreement in 1918, Rathenau as foreign minister was responsible, among other things, for the reparations issue. He had also sought to break Germany's isolation after World War I through the

1922 Treaty of Rapallo with the

Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. However, he also drew right-wing extremist hatred as a Jew (see also

Weimar antisemitism). The solidarity expressed in large, public funeral processions for those murdered, and the passage of a were intended to put a stop to the right-wing enemies of the Weimar Republic. However, right-wing state criminals were not permanently deterred from their activities, and the lenient sentences they were given by judges influenced by imperial conservatism were a contributing factor.

In 1922, Germany signed the

Treaty of Rapallo Following World War I there were two Treaties of Rapallo, both named after Rapallo, a resort on the Ligurian coast of Italy:

* Treaty of Rapallo, 1920, an agreement between Italy and the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (the later Yugosla ...

with the Soviet Russia, which allowed Germany to train military personnel in exchange for giving Russia military technology. This was against the

Treaty of Versailles, which limited Germany to 100,000 soldiers and no conscription, naval forces of 15,000 men, twelve destroyers, six battleships, and six cruisers, no

submarines or aircraft. However, Russia had pulled out of the First World War against the Germans as a result of the

1917 Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

and was excluded from the

League of Nations. Thus, Germany seized the chance to make an ally.

Walther Rathenau

Walther Rathenau (29 September 1867 – 24 June 1922) was a German industrialist, writer and liberal politician.

During the First World War of 1914–1918 he was involved in the organization of the German war economy. After the war, Rathenau s ...

, the Jewish

Foreign Minister who signed the treaty, was assassinated two months later by two ultra-nationalist army officers.

Further pressure from the political right came in 1923 with the

Beer Hall Putsch

The Beer Hall Putsch, also known as the Munich Putsch,Dan Moorhouse, ed schoolshistory.org.uk, accessed 2008-05-31.Known in German as the or was a failed coup d'état by Nazi Party ( or NSDAP) leader Adolf Hitler, Erich Ludendorff and oth ...

(aka Munich Putsch), a failed

power seizure staged by the

Nazi Party under

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

in Munich. In 1920, the

German Workers' Party had become the

National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), or

Nazi Party, which would eventually become a driving force in the collapse of Weimar. Hitler named himself as chairman of the party in July 1921. On 8 November 1923, the ''

Kampfbund'', in a pact with

Erich Ludendorff

Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff (9 April 1865 – 20 December 1937) was a German general, politician and military theorist. He achieved fame during World War I for his central role in the German victories at Liège and Tannenberg in 1914 ...

, took over a meeting by Bavarian prime minister

Gustav von Kahr

Gustav Ritter von Kahr (; born Gustav Kahr; 29 November 1862 – 30 June 1934) was a German right-wing politician, active in the state of Bavaria. He helped turn post–World War I Bavaria into Germany's center of radical-nationalism but was th ...

at a beer hall in Munich.

Ludendorff and Hitler declared that the Weimar government was deposed and that they were planning to take control of Munich the following day. But the 3,000 rebels were no match yet for the Bavarian authorities. Hitler was arrested and sentenced to five years in prison for high

treason, the minimum sentence for the charge. However, Hitler served less than eight months, in a comfortable cell, receiving a daily stream of visitors, until his release on 20 December 1924. While in jail, Hitler dictated ''

Mein Kampf'', which laid out his ideas and future policies. Hitler now decided to focus on legal methods of gaining power.

Golden Era (1924–1929)

Gustav Stresemann was ''

Reichskanzler

The chancellor of Germany, officially the federal chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany,; often shortened to ''Bundeskanzler''/''Bundeskanzlerin'', / is the head of the federal government of Germany and the commander in chief of the Ge ...

'' for 100 days in 1923, and served as

foreign minister from 1923 to 1929, a period of relative stability for the Weimar Republic, known in Germany as ''Goldene Zwanziger'' ("

Golden Twenties"). Prominent features of this period were a growing economy and a consequent decrease in civil unrest.

Once civil stability had been restored, Stresemann began stabilising the German currency, which promoted confidence in the German economy and helped the recovery that was so greatly needed for the German nation to keep up with their reparation repayments, while at the same time feeding and supplying the nation.

Once the economic situation had stabilised, Stresemann could begin putting a permanent currency in place, called the ''

Rentenmark'' (October 1923), which again contributed to the growing level of international confidence in the Weimar Republic's economy.

To help Germany meet reparation obligations, the

Dawes Plan

The Dawes Plan (as proposed by the Dawes Committee, chaired by Charles G. Dawes) was a plan in 1924 that successfully resolved the issue of World War I reparations that Germany had to pay. It ended a crisis in European diplomacy following W ...

was created in 1924. This was an agreement between American banks and the German government in which the American banks lent money to German banks with German assets as collateral to help it pay reparations. The German railways, the National Bank and many industries were therefore mortgaged as securities for the stable currency and the loans.

[Kitchen, ''Illustrated History of Germany'', Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 241]

Germany was the first state to establish diplomatic relations with the new

Soviet Union. Under the

Treaty of Rapallo Following World War I there were two Treaties of Rapallo, both named after Rapallo, a resort on the Ligurian coast of Italy:

* Treaty of Rapallo, 1920, an agreement between Italy and the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (the later Yugosla ...

, Germany accorded it formal (''de jure'') recognition, and the two mutually cancelled all pre-war debts and renounced war claims. In October 1925 the

Treaty of Locarno

The Locarno Treaties were seven agreements negotiated at Locarno, Switzerland, during 5 to 16 October 1925 and formally signed in London on 1 December, in which the First World War Western European Allied powers and the new states of Central ...

was signed by Germany, France, Belgium, Britain, and Italy; it recognised Germany's borders with France and Belgium. Moreover, Britain, Italy and Belgium undertook to assist France in the case that German troops marched into the demilitarised Rhineland. Locarno paved the way for Germany's admission to the

League of Nations in 1926. Germany signed arbitration conventions with France and Belgium and arbitration treaties with Poland and

Czechoslovakia, undertaking to refer any future disputes to an arbitration tribunal or to the

Permanent Court of International Justice

The Permanent Court of International Justice, often called the World Court, existed from 1922 to 1946. It was an international court attached to the League of Nations. Created in 1920 (although the idea of an international court was several cent ...

. Other foreign achievements were the evacuation of foreign troops from the Ruhr in 1925. In 1926, Germany was admitted to the League of Nations as a permanent member, improving her international standing and giving the right to vote on League matters.

Overall trade increased and unemployment fell. Stresemann's reforms did not relieve the underlying weaknesses of Weimar but gave the appearance of a stable democracy. Even Stresemann's

German People's Party

The German People's Party (German: , or DVP) was a liberal party during the Weimar Republic that was the successor to the National Liberal Party of the German Empire. A right-liberal, or conservative-liberal political party, it represented polit ...

failed to gain nationwide recognition, and instead featured in the 'flip-flop' coalitions. The Grand Coalition headed by Muller inspired some faith in the government, but that did not last. Governments frequently lasted only a year, comparable to the political situation in France during the 1930s. The major weakness in constitutional terms was the inherent instability of the coalitions, which often fell prior to elections. The growing dependence on American finance was to prove fleeting, and Germany was one of the worst hit nations in the

Great Depression.

Culture

The 1920s saw a remarkable cultural renaissance in Germany. During the worst phase of hyperinflation in 1923, the clubs and bars were full of speculators who spent their daily profits so they would not lose the value the following day. Berlin intellectuals responded by condemning the excesses of what they considered capitalism and demanding revolutionary changes on the cultural scenery.

Influenced by the brief cultural explosion in the Soviet Union, German literature, cinema, theatre and musical works entered a phase of great creativity. Innovative street theatre brought plays to the public, and the

cabaret

Cabaret is a form of theatrical entertainment featuring music, song, dance, recitation, or drama. The performance venue might be a pub, a casino, a hotel, a restaurant, or a nightclub with a stage for performances. The audience, often dining or ...

scene and jazz bands became very popular. According to the cliché, modern young women were

Americanized

Americanization or Americanisation (see spelling differences) is the influence of American culture and business on other countries outside the United States of America, including their media, cuisine, business practices, popular culture, tech ...

, wearing makeup, short hair, smoking and breaking with traditional

mores

Mores (, sometimes ; , plural form of singular , meaning "manner, custom, usage, or habit") are social norms that are widely observed within a particular society or culture. Mores determine what is considered morally acceptable or unacceptable ...

. The euphoria surrounding

Josephine Baker in the metropolis of Berlin for instance, where she was declared an "erotic

goddess" and in many ways admired and respected, kindled further "ultramodern" sensations in the minds of the German public. Art and a new type of architecture taught at "

Bauhaus" schools reflected the new ideas of the time, with artists such as

George Grosz being fined for defaming the military and for

blasphemy

Blasphemy is a speech crime and religious crime usually defined as an utterance that shows contempt, disrespects or insults a deity, an object considered sacred or something considered inviolable. Some religions regard blasphemy as a religio ...

.

Artists in Berlin were influenced by other contemporary progressive cultural movements, such as the Impressionist and Expressionist painters in Paris, as well as the Cubists. Likewise, American progressive architects were admired. Many of the new buildings built during this era followed a straight-lined, geometrical style. Examples of the new architecture include the

Bauhaus Building by

Gropius,

Grosses Schauspielhaus, and the

Einstein Tower

The Einstein Tower (German: ''Einsteinturm'') is an astrophysical observatory in the Albert Einstein Science Park in Potsdam, Germany built by architect Erich Mendelsohn. It was built on the summit of the Potsdam '' Telegraphenberg'' to house a ...

.

Not everyone, however, was happy with the changes taking place in

Weimar culture. Conservatives and reactionaries feared that Germany was betraying its traditional values by adopting popular styles from abroad, particularly those Hollywood was popularising in American films, while New York became the global capital of fashion. Germany was more susceptible to Americanization, because of the close economic links brought about by the Dawes plan.

In 1929, three years after receiving the 1926

Nobel Peace Prize, Stresemann died of a heart attack at age 51. When the New York Stock Exchange crashed in October 1929, American loans dried up and the sharp decline of the German economy brought the "Golden Twenties" to an abrupt end.

Social policy under Weimar

A wide range of progressive social reforms were carried out during and after the revolutionary period. In 1919, legislation provided for a maximum working 48-hour workweek, restrictions on night work, a half-holiday on Saturday, and a break of thirty-six hours of continuous rest during the week. That same year, health insurance was extended to wives and daughters without their own income, people only partially capable of gainful employment, people employed in private cooperatives, and people employed in public cooperatives.

A series of progressive tax reforms were introduced under the auspices of Matthias Erzberger, including increases in taxes on capital and an increase in the highest income tax rate from 4% to 60%. Under a governmental decree of 3 February 1919, the German government met the demand of the veterans' associations that all aid for the disabled and their dependents be taken over by the central government (thus assuming responsibility for this assistance) and extended into peacetime the nationwide network of state and district welfare bureaus that had been set up during the war to coordinate social services for war widows and orphans.

The Imperial Youth Welfare Act of 1922 obliged all municipalities and states to set up youth offices in charge of child protection, and also codified a right to education for all children, while laws were passed to regulate rents and increase protection for tenants in 1922 and 1923. Health insurance coverage was extended to other categories of the population during the existence of the Weimar Republic, including seamen, people employed in the educational and social welfare sectors, and all primary dependents.

Various improvements were also made in unemployment benefits, although in June 1920 the maximum amount of unemployment benefit that a family of four could receive in Berlin, 90 marks, was well below the minimum cost of subsistence of 304 marks.

In 1923, unemployment relief was consolidated into a regular programme of assistance following economic problems that year. In 1924, a modern public assistance programme was introduced, and in 1925 the accident insurance programme was reformed, allowing diseases that were linked to certain kinds of work to become insurable risks. In addition, a national unemployment insurance programme was introduced in 1927. Housing construction was also greatly accelerated during the Weimar period, with over 2 million new homes constructed between 1924 and 1931 and a further 195,000 modernised.

Renewed crisis and decline (1930–1933)

Onset of the Great Depression

In 1929, the onset of the

depression in the United States of America produced a severe economic shock in Germany and was further made worse by the bankruptcy of the Austrian

Creditanstalt

The Creditanstalt (sometimes Credit-Anstalt, abbreviated as CA), full original name k. k. priv. Österreichische Credit-Anstalt für Handel und Gewerbe (), was a major Austrian bank, founded in 1855 in Vienna.

From its founding until 1931, th ...

bank. Germany's fragile economy had been sustained by the granting of loans through the

Dawes Plan

The Dawes Plan (as proposed by the Dawes Committee, chaired by Charles G. Dawes) was a plan in 1924 that successfully resolved the issue of World War I reparations that Germany had to pay. It ended a crisis in European diplomacy following W ...

(1924) and the

Young Plan

The Young Plan was a program for settling Germany's World War I reparations. It was written in August 1929 and formally adopted in 1930. It was presented by the committee headed (1929–30) by American industrialist Owen D. Young, founder and fo ...

(1929). When American banks withdrew their line of credit to German companies, the onset of severe unemployment could not be abated by conventional economic measures. Unemployment thereafter grew dramatically, at 4 million in 1930, and in September 1930 a political earthquake shook the republic to its foundations. The

National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), until then a minor far-right party, increased its votes to 19%, becoming Germany's second largest party, while the

Communist Party of Germany (KPD) also increased its votes; this made the unstable coalition system by which every chancellor had governed increasingly unworkable. The last years of the Weimar Republic were marred by even more systemic political instability than previous years, as political violence increased. Four Chancellors (

Heinrich Brüning

Heinrich Aloysius Maria Elisabeth Brüning (; 26 November 1885 – 30 March 1970) was a German Centre Party politician and academic, who served as the chancellor of Germany during the Weimar Republic from 1930 to 1932.

A political scientis ...

,

Franz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, Erbsälzer zu Werl und Neuwerk (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German conservative politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and General Staff officer. He served as the chancellor of Germany in ...

,

Kurt von Schleicher) and, from 30 January to 23 March 1933,

Hitler governed through

presidential decree rather than through

parliamentary

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

consultation. This effectively rendered parliament as a means of enforcing constitutional

checks and balances

Separation of powers refers to the division of a state's government into branches, each with separate, independent powers and responsibilities, so that the powers of one branch are not in conflict with those of the other branches. The typic ...

powerless.

Brüning's policy of deflation (1930–1932)

On 29 March 1930, after months of lobbying by General

Kurt von Schleicher on behalf of the military, the finance expert

Heinrich Brüning

Heinrich Aloysius Maria Elisabeth Brüning (; 26 November 1885 – 30 March 1970) was a German Centre Party politician and academic, who served as the chancellor of Germany during the Weimar Republic from 1930 to 1932.

A political scientis ...

was appointed as Müller's successor by ''

Reichspräsident''

Paul von Hindenburg. The new government was expected to lead a political shift towards conservatism.

As Brüning had no majority support in the ''Reichstag'', he became, through the use of

the emergency powers granted to the ''Reichspräsident'' (Article 48) by

the constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princi ...

, the first Weimar chancellor to operate independently of parliament. This made him dependent on the ''Reichspräsident'', Hindenburg.

[Thomas Adam, ''Germany and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History'', 2005, , p. 185] After a bill to reform the Reich's finances was opposed by the ''Reichstag'', it was made an emergency decree by Hindenburg. On 18 July, as a result of opposition from the SPD,

KPD

The Communist Party of Germany (german: Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, , KPD ) was a major political party in the Weimar Republic between 1918 and 1933, an underground resistance movement in Nazi Germany, and a minor party in West Germ ...

,

DNVP

The German National People's Party (german: Deutschnationale Volkspartei, DNVP) was a national-conservative party in Germany during the Weimar Republic. Before the rise of the Nazi Party, it was the major conservative and nationalist party in Wei ...