Province Of Posen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Province of Posen (german: Provinz Posen, pl, Prowincja Poznańska) was a

Following Germany's defeat in World War in 1945, at Stalin's demand all of the German territory east of the newly established Oder–Neisse line of the

Following Germany's defeat in World War in 1945, at Stalin's demand all of the German territory east of the newly established Oder–Neisse line of the

This region was inhabited by a Polish majority, with

This region was inhabited by a Polish majority, with

Prussian provinces were subdivided into government regions (''

Prussian provinces were subdivided into government regions ('' Data is from Prussian censuses, during a period of state-sponsored Germanization, and includes military garrisons. It is often criticized as being falsified.

Data is from Prussian censuses, during a period of state-sponsored Germanization, and includes military garrisons. It is often criticized as being falsified.Spisy ludności na ziemiach polskich do 1918 r

The German figure includes the German-speaking Jewish population.

(see also Notable people of Grand Duchy of Posen) * Stanisław Adamski (1875–1967), Polish priest, social and political activist of the Union of Catholic Societies of Polish Workers ('), founder and editor of the 'Robotnik' (Worker) weekly * Leo Baeck (1873–1956), German rabbi, scholar, and theologian * Tomasz K. Bartkiewcz (1865–1931), Polish composer and organist, co-founder of the Singer Circles Union (Związek Kół Śpiewackich) * Wernher von Braun (1912 –1977) German rocket engineer and space architect; a leading figure in the development of rocket technology, from the V1 & V2 to the Saturn rocket that powered the first Moon landing, and credited as being the "Father of Rocket Science" * Czesław Czypicki (1855–1926), Polish lawyer from Kożmin, activist for the singers' societies * Michał Drzymała (1857–1937), Polish peasant * Ferdinand Hansemann (1861–1900), Prussian politician, co-founder of the German Eastern Marches Society *

Administrative subdivision of the province (in 1910)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Posen, Province Of Provinces of Prussia Prussian Partition History of Poznań 1848 establishments in Prussia 1919 disestablishments in Germany Former eastern territories of Germany

province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions out ...

of the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. ...

from 1848 to 1920. Posen was established in 1848 following the Greater Poland Uprising as a successor to the Grand Duchy of Posen, which in turn was annexed by Prussia in 1815 from Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

's Duchy of Warsaw. It became part of the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

in 1871. After World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, Posen was briefly part of the Free State of Prussia within Weimar Germany, but was dissolved in 1920 when most of its territory was ceded to the Second Polish Republic by the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

, and the remaining German territory was later re-organized into Posen-West Prussia

The Frontier March of Posen-West Prussia (german: Grenzmark Posen-Westpreußen, pl, Marchia Graniczna Poznańsko-Zachodniopruska) was a province of Prussia from 1922 to 1938. Posen-West Prussia was established in 1922 as a province of the Fre ...

in 1922.

Posen (present-day Poznań, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

) was the provincial capital.

Geography

The land is mostly flat, drained by two majorwatershed

Watershed is a hydrological term, which has been adopted in other fields in a more or less figurative sense. It may refer to:

Hydrology

* Drainage divide, the line that separates neighbouring drainage basins

* Drainage basin, called a "watershe ...

systems; the Noteć (German: ''Netze'') in the north and the Warta (''Warthe'') in the center. Ice Age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and gre ...

glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such a ...

s left moraine

A moraine is any accumulation of unconsolidated debris ( regolith and rock), sometimes referred to as glacial till, that occurs in both currently and formerly glaciated regions, and that has been previously carried along by a glacier or ice sh ...

deposits and the land is speckled with hundreds of "finger lakes", streams flowing in and out on their way to one of the two rivers.

Agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people ...

was the primary industry. The three-field system

The three-field system is a regime of crop rotation in which a field is planted with one set of crops one year, a different set in the second year, and left fallow in the third year. A set of crops is ''rotated'' from one field to another. The tec ...

was used to grow a variety of crops, primarily rye, sugar beet

A sugar beet is a plant whose root contains a high concentration of sucrose and which is grown commercially for sugar production. In plant breeding, it is known as the Altissima cultivar group of the common beet ('' Beta vulgaris''). Together ...

, potato

The potato is a starchy food, a tuber of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'' and is a root vegetable native to the Americas. The plant is a perennial in the nightshade family Solanaceae.

Wild potato species can be found from the southern Uni ...

es, other grains, and some tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

and hops

Hops are the flowers (also called seed cones or strobiles) of the hop plant '' Humulus lupulus'', a member of the Cannabaceae family of flowering plants. They are used primarily as a bittering, flavouring, and stability agent in beer, to w ...

. Significant parcels of wooded land provided building materials and firewood. Small numbers of livestock

Livestock are the domesticated animals raised in an agricultural setting to provide labor and produce diversified products for consumption such as meat, eggs, milk, fur, leather, and wool. The term is sometimes used to refer solely to ani ...

existed, including geese, but a fair number of sheep

Sheep or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are domesticated, ruminant mammals typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus '' Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to domesticate ...

were herded.

The area roughly corresponded to the historic region of Greater Poland

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; german: Großpolen, sv, Storpolen, la, Polonia Maior), is a historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań followed by Kalisz, the oldest cit ...

.Gerhard Köbler, ', 7th edition, C.H.Beck, 2007, p.535, For more than a century, it was part of the Prussian Partition, with a brief exception during the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

. When this area came under Prussian control, the feudal system

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structu ...

was still in force. It was officially ended in Prussia (''see'' Freiherr vom Stein) in 1810 (1864 in Congress Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. I ...

), but lingered in some practices until the late 19th century. The situation was thus that (primarily) Polish serfs lived and worked side by side with (predominantly) free German settlers. Though the settlers were given initial advantages, in time their lots were not much different. Serfs worked for the noble lord, who took care of them. Settlers worked for themselves and took care of themselves, but paid taxes to the lord.

Typically, an estate would have its manor and farm buildings, and a village nearby for the Polish laborers. Near that village, there might be a German settlement. And in the woods, there would be a forester's dwelling. The estate owners, usually of the nobility, owned the local grist mill

A gristmill (also: grist mill, corn mill, flour mill, feed mill or feedmill) grinds cereal grain into flour and middlings. The term can refer to either the grinding mechanism or the building that holds it. Grist is grain that has been separat ...

, and often other types of mills or perhaps a distillery

Distillation, or classical distillation, is the process of separating the components or substances from a liquid mixture by using selective boiling and condensation, usually inside an apparatus known as a still. Dry distillation is the hea ...

. In many places, windmills

A windmill is a structure that converts wind power into rotational energy using vanes called sails or blades, specifically to mill grain (gristmills), but the term is also extended to windpumps, wind turbines, and other applications, in some par ...

dotted the landscape, reminding one of the earliest settlers, the Dutch, who began the process of turning unproductive river marshes into fields. This process was finished by the German settlers employed to reclaim unproductive lands (not only marshland) for the host estate owners.

History

The territory of later province had become Prussian in 1772 ( Netze District) and 1793 ( South Prussia) during the First and Second Partition of Poland. After Prussia's defeat in theNapoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

, the territory was attached to the Duchy of Warsaw in 1807 upon the Franco-Prussian Treaty of Tilsit. In 1815 during the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon ...

, Prussia gained the western third of the Warsaw duchy, which was about half of former South Prussia. Prussia then administered this province as the semi-autonomous Grand Duchy of Posen, which lost most of its exceptional status already after the 1830 November Uprising in Congress Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. I ...

, as the Prussian authorities feared a Polish national movement which would have swept away the Holy Alliance system in Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the a ...

. Instead Prussian Germanisation

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, people and culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationalism went hand in hand. In lin ...

measures increased under ''Oberpräsident'' Eduard Heinrich von Flottwell

Eduard Heinrich Flottwell (23 July 1786 – 28 May 1865; after 1861 von Flottwell) was a Prussian '' Staatsminister''. He served as ''Oberpräsident'' (governor) of the Grand Duchy of Posen (from 1830) and of the Saxony (from 1841), Westphali ...

, who had replaced Duke-governor Antoni Radziwiłł.

A first Greater Poland Uprising in 1846 failed, as the leading insurgents around Karol Libelt and Ludwik Mierosławski were reported to the Prussian police and arrested for high treason. Their trial at the Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

'' Kammergericht'' court gained them enormous popularity even among German national liberals, who themselves were suppressed by the Carlsbad Decrees

The Carlsbad Decrees (german: Karlsbader Beschlüsse) were a set of reactionary restrictions introduced in the states of the German Confederation by resolution of the Bundesversammlung on 20 September 1819 after a conference held in the spa town ...

. Both were released in the March Revolution of 1848 and triumphantly carried through the streets.

At the same time, a Polish national committee gathered at Poznań and demanded independence. The Prussian Army

The Royal Prussian Army (1701–1919, german: Königlich Preußische Armee) served as the army of the Kingdom of Prussia. It became vital to the development of Brandenburg-Prussia as a European power.

The Prussian Army had its roots in the co ...

under General Friedrich August Peter von Colomb at first retired. King Frederick William IV of Prussia as well as the new Prussian commissioner, Karl Wilhelm von Willisen

Karl Wilhelm Freiherr von Willisen (30 April 1790 – 25 February 1879) was a Prussian general.

Biography

Willisen was born in Stassfurt as the third son of the mayor of Stassfurt, Karl Wilhelm Hermann von Willisen (1751–1807) and his wife ...

, promised a renewed autonomy status.

However, both among the German-speaking population of the province as well as in the Prussian capital, anti-Polish

Polonophobia, also referred to as anti-Polonism, ( pl, Antypolonizm), and anti-Polish sentiment are terms for negative attitudes, prejudices, and actions against Poles as an ethnic group, Poland as their country, and their culture. These incl ...

sentiments arose. While the local Posen (Poznań

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint Joh ...

) Parliament voted 26 to 17 votes against joining German Confederation, on 3 April 1848 Andrzej Chwalba - Historia Polski 1795-1918 Wydawnictwo Literackie 2000 Kraków the Frankfurt Parliament ignored the vote, unsuccessfully attempting its status change to a common Prussian province, as well as its incorporation into the German Confederation

The German Confederation (german: Deutscher Bund, ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, w ...

. The Frankfurt parliamentarian Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Jordan vehemently spoke against Polish autonomy. The assembly at first attempted to divide the Posen duchy into two parts: the Province of Posen, which would have been given to the German population and annexed to a newly created Greater Germany, and the Province of Gniezno, which would have been given to the Poles and remain outside of Germany. Because of the protest of Polish politicians, this plan failed and the integrity of the duchy was preserved.

Nevertheless, when the Prussian troops had finally crushed the Greater Polish revolt, after a series of broken assurances, on 9 February 1849 the Prussian authorities renamed the duchy as the Province of Posen. In spite of that, the territory formally remained outside of the German Confederation

The German Confederation (german: Deutscher Bund, ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, w ...

(and thus Germany) until the German Confederation was dissolved and the North German Confederation was established, which occurred in 1866. Nevertheless, the Prussian Kings retained the title "Grand Duke of Posen" until the German and Prussian monarchy finally expired in 1918, following the abdication of William II.

With the unification of Germany after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the Province of Posen became part of the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

, and the city of Posen was officially named an imperial residence city. Bismarck's hostility towards the Poles was already well known, as in 1861 he had written in a letter to his sister: ''"Hit the Poles so hard that they despair of their life; I have full sympathy for their condition, but if we want to survive we can only exterminate them."'' His dislike was firmly entrenched in traditions of Prussian mentality and history. There was little need for discussions in Prussian circles, as most of them, including the monarch, agreed with his views. Poles suffered from discrimination by the Prussian state; numerous oppressive measures were implemented to eradicate the Polish community's identity and culture.

The Polish inhabitants of Posen, who faced discrimination and even forced Germanization, favored the French side during the Franco-Prussian War. France and Napoleon III were known for their support and sympathy for the Poles under Prussian rule Demonstrations at news of Prussian-German victories manifested Polish independence feelings and calls were also made for Polish recruits to desert from the Prussian Army

The Royal Prussian Army (1701–1919, german: Königlich Preußische Armee) served as the army of the Kingdom of Prussia. It became vital to the development of Brandenburg-Prussia as a European power.

The Prussian Army had its roots in the co ...

, though these went mostly unheeded. Bismarck regarded these as an indication of a Slavic-Roman encirclement and even a threat to unified Germany. Under German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck renewed Germanisation policies began, including an increase of the police, a colonization commission, and the ''Kulturkampf

(, 'culture struggle') was the conflict that took place from 1872 to 1878 between the Catholic Church in Germany, Catholic Church led by Pope Pius IX and the government of Kingdom of Prussia, Prussia led by Otto von Bismarck. The main issues wer ...

''. The German Eastern Marches Society (''Hakata'') pressure group was founded in 1894 and in 1904, special legislation was passed against the Polish population. The legislation of 1908 allowed for the confiscation of Polish-owned property. The Prussian authorities did not permit the development of industries in Posen, so the duchy's economy was dominated by high-level agriculture.

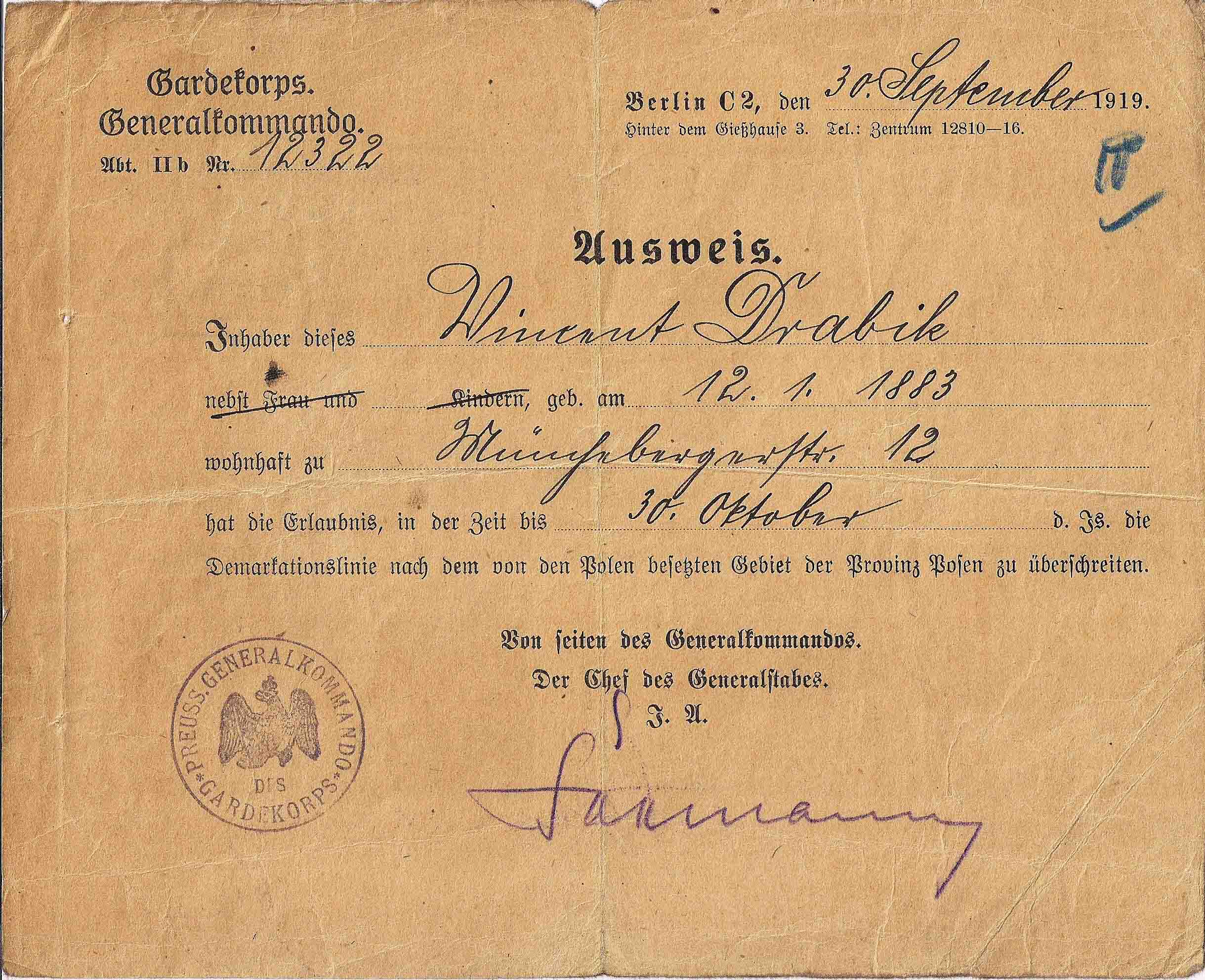

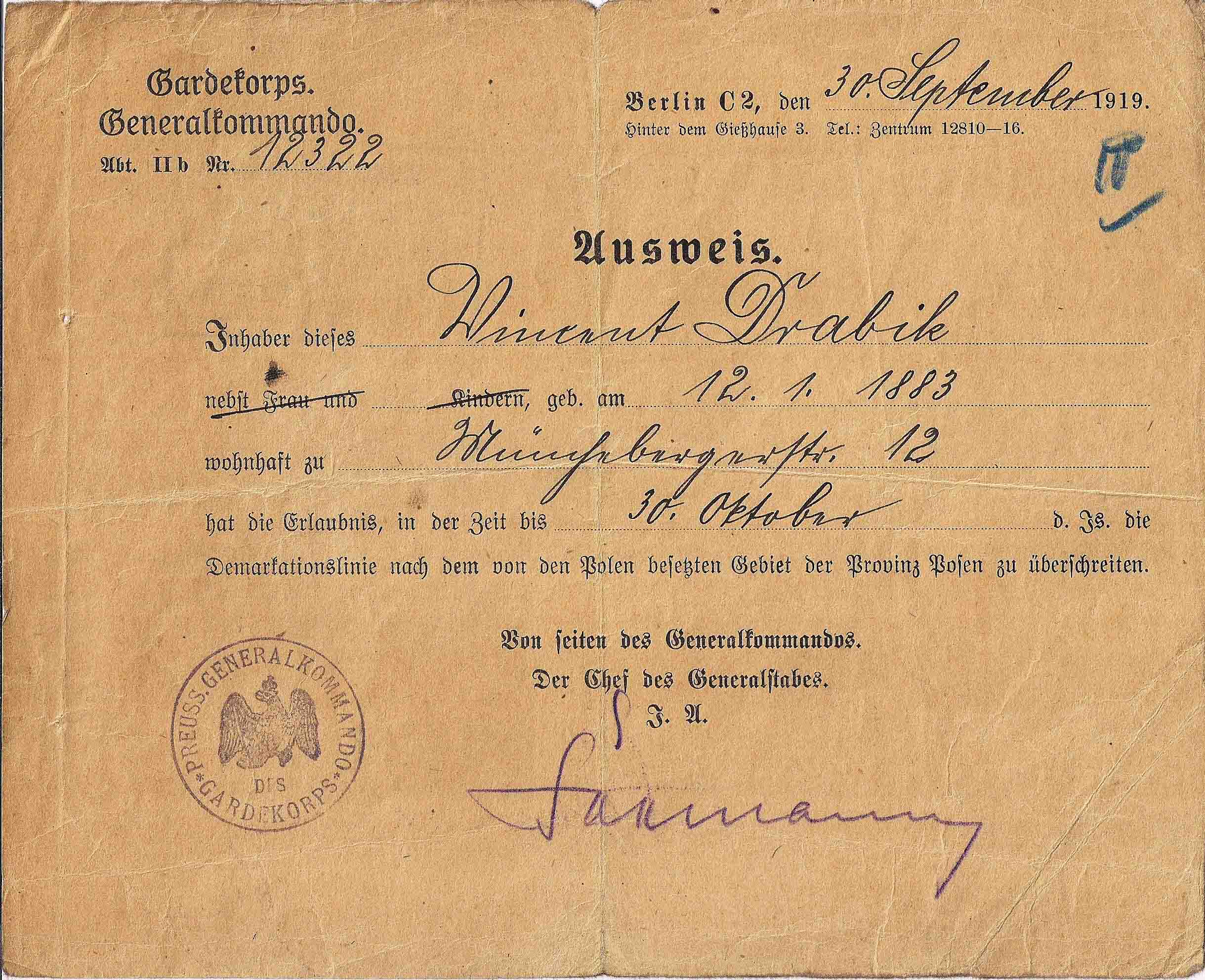

At the end of World War I, the fate of the province was undecided. The Polish inhabitants demanded the region be included in the newly independent Second Polish Republic, while the German minority refused any territorial concessions. Another Greater Poland Uprising broke out on 27 December 1918, a day after Ignacy Jan Paderewski's speech. The uprising received little support from the Polish government in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officiall ...

. After the success of the uprising, Posen province was until mid-1919 an independent state with its own government, currency and military. With the signing of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

in 1919, most of the province, composed of the areas with a Polish majority, was ceded to Poland and was reformed as the Poznań Voivodeship. The majority-German populated remainder (with Bomst, Fraustadt, Neu Bentschen, Meseritz, Tirschtiegel (partially), Schwerin

Schwerin (; Mecklenburgian Low German: ''Swerin''; Latin: ''Suerina'', ''Suerinum'') is the capital and second-largest city of the northeastern German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern as well as of the region of Mecklenburg, after Rostock. It ...

, Blesen, Schönlanke, Filehne, Schloppe, Deutsch Krone, Tütz, Schneidemühl, Flatow, Jastrow, and Krojanke

Krajenka (german: Krojanke) is a town in the Greater Poland Voivodeship of Poland. It has 3,804 inhabitants (2005) and lies in Złotów County.

Geographical location

Krajenka is located approximately 15 kilometers south of Złotów, 50 kilom ...

, about , was merged with the western remains of former West Prussia and was administered as Posen-West Prussia

The Frontier March of Posen-West Prussia (german: Grenzmark Posen-Westpreußen, pl, Marchia Graniczna Poznańsko-Zachodniopruska) was a province of Prussia from 1922 to 1938. Posen-West Prussia was established in 1922 as a province of the Fre ...

with Schneidemühl as its capital. This province was dissolved in 1938, when its territory was split between the neighboring Prussian provinces of Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. S ...

, Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

and Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an area of 29,480 squ ...

. In 1939, the territory of the former province of Posen was annexed by Nazi Germany and made part of Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia

Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia (german: Reichsgau Danzig-Westpreußen) was an administrative division of Nazi Germany created on 8 October 1939 from annexed territory of the Free City of Danzig, the Greater Pomeranian Voivodship ( Polish Corridor ...

and Reichsgau Wartheland (initially ''Reichsgau Posen''). By the time World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

ended in May 1945, it had been overrun by the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

.

Following Germany's defeat in World War in 1945, at Stalin's demand all of the German territory east of the newly established Oder–Neisse line of the

Following Germany's defeat in World War in 1945, at Stalin's demand all of the German territory east of the newly established Oder–Neisse line of the Potsdam Agreement

The Potsdam Agreement (german: Potsdamer Abkommen) was the agreement between three of the Allies of World War II: the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Soviet Union on 1 August 1945. A product of the Potsdam Conference, it concerned th ...

was either turned over to the Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

or the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

. All historical parts of the province came under Polish control, and the remaining ethnic German population was expelled by force.

Dissolution after 1918

Religious and ethnic composition

This region was inhabited by a Polish majority, with

This region was inhabited by a Polish majority, with German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

and Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

minorities and a smattering of other ethnic groups. Almost all the Poles were Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

, and most of the Germans were Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

. The small numbers of Jews were primarily in the larger communities, mostly in skilled crafts, local commerce and regional trading. The smaller a community, the more likely it was to be either all Polish or German. These "pockets of ethnicity" existed side by side, with German villages being the most dense in the northwestern areas. Under Prussia's Germanization policies, the population became more German until the end of the 19th century, when the trend reversed (in the Ostflucht). This was despite efforts of the government in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

to prevent it, establishing the Settlement Commission to buy land from Poles and make it available for sale only to Germans.

The province's large number of resident Germans resulted from constant immigration since the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, when the first settlers arrived in the course of the Ostsiedlung. Although many of those had been Polonized over time, a continuous immigration resulted in maintaining a large German community. The 18th century Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

-led Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

enacted severe restrictions on German Protestants. At the end of the 18th century when Prussia seized the area during the Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place toward the end of the 18th century and ended the existence of the state, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland and Lithuania for 12 ...

, thousands of German colonists were sent by Prussian officials to Germanize the area.

During the first half of the 19th century, the German population grew due to state sponsored colonisation. In the second half, the Polish population grew gradually due to the '' Ostflucht'' and a higher birthrate among the Poles. In the ''Kulturkampf

(, 'culture struggle') was the conflict that took place from 1872 to 1878 between the Catholic Church in Germany, Catholic Church led by Pope Pius IX and the government of Kingdom of Prussia, Prussia led by Otto von Bismarck. The main issues wer ...

'', mainly Protestant Prussia sought to reduce the Catholic impact on its society. Posen was hit severely by these measures due to its large, mainly Polish Catholic population. Many Catholic Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, image = Hohe_Domkirche_St._Petrus.jpg

, imagewidth = 200px

, alt =

, caption = Cologne Cathedral, Cologne

, abbreviation =

, type = Nat ...

in Posen joined with ethnic Poles in opposition to anti-Catholic Kulturkampf measures. Following the Kulturkampf, the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

for nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

reasons implemented Germanisation programs. One measure was to set up a Settlement Commission to attract German settlers to counter the Polish population's higher growth. However, this failed, even when accompanied by additional legal measures. The Polish language was eventually banned from use in schools and government offices as part of the Germanisation policies.

There is a notable disparity between German statistics gathered by the Prussian administration, and the Polish estimates conducted after 1918. According to the Prussian census of 1905, the number of German speakers in the Province of Posen was approximately 38.5% (which included colonists, military stationed in the area and German administration), while after 1918 the number of Germans in the Poznan Voivodship, which closely corresponded to province of Posen, was only 7%. According to Witold Jakóbczyk, the disparity between the number of ethnic Germans and the number of German speakers is because Prussian authorities placed ethnic Germans and the German-speaking Jewish minority into the same class. Around 161,000 Germans in the province were officials, soldiers and their families settled in the region by German Empire. In addition, there was a considerable exodus of Germans from the Second Polish Republic after the latter was established. There was also Polonization of local Catholic Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, image = Hohe_Domkirche_St._Petrus.jpg

, imagewidth = 200px

, alt =

, caption = Cologne Cathedral, Cologne

, abbreviation =

, type = Nat ...

. Another reason of the disparity is that some border areas of the province, inhabited mostly by Germans (including Piła), remained in Germany after 1918.Stefan Wolff, ''The German Question Since 1919: An Analysis with Key Documents'', Greenwood Publishing Group, 2003, p.33, According to Polish authors, the real share of Poles in 1910 was 65% (rather than 61.5% claimed by official census).

Statistics

Area: 28,970 km2 Population *1816: 820,176 *1868: 1,537,300 (Bydgoszcz 550,900 - Poznan 986,400) *1871: 1,583,843 **Religion: 1871 ***Catholics 1,009,885 ***Protestants 511,429 ***Jews 61,982 ***others 547 *1875: 1,606,084 *1880: 1,703,397 *1900: 1,887,275 *1905: 1,986,267 *1910: 2,099,831 (Bromberg

Bydgoszcz ( , , ; german: Bromberg) is a city in northern Poland, straddling the meeting of the River Vistula with its left-bank tributary, the Brda. With a city population of 339,053 as of December 2021 and an urban agglomeration with mor ...

- 763,947, Posen - 1,335,884)

Divisions

Regierungsbezirk

A ' () means "governmental district" and is a type of administrative division in Germany. Four of sixteen ' ( states of Germany) are split into '. Beneath these are rural and urban districts.

Saxony has ' (directorate districts) with more res ...

e''), in Posen:

* Regierungsbezirk Posen 17,503 km2

* Regierungsbezirk Bromberg 11,448 km2

These regions were again subdivided into districts called '' Kreise''. Cities would have their own "Stadtkreis" (urban district) and the surrounding rural area would be named for the city, but referred to as a "Landkreis" (rural district). In the case of Posen, the Landkreis was split into two: Landkreis Posen West, and Landkreis Posen East.

Presidents

The province was headed by presidents (german: Oberpräsidenten).Notable people

(in alphabetical order)(see also Notable people of Grand Duchy of Posen) * Stanisław Adamski (1875–1967), Polish priest, social and political activist of the Union of Catholic Societies of Polish Workers ('), founder and editor of the 'Robotnik' (Worker) weekly * Leo Baeck (1873–1956), German rabbi, scholar, and theologian * Tomasz K. Bartkiewcz (1865–1931), Polish composer and organist, co-founder of the Singer Circles Union (Związek Kół Śpiewackich) * Wernher von Braun (1912 –1977) German rocket engineer and space architect; a leading figure in the development of rocket technology, from the V1 & V2 to the Saturn rocket that powered the first Moon landing, and credited as being the "Father of Rocket Science" * Czesław Czypicki (1855–1926), Polish lawyer from Kożmin, activist for the singers' societies * Michał Drzymała (1857–1937), Polish peasant * Ferdinand Hansemann (1861–1900), Prussian politician, co-founder of the German Eastern Marches Society *

Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (; abbreviated ; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany fr ...

(1847–1934), German field marshal and statesman, last President of Germany before Adolf Hitler

* Józef Kościelski

Józef Kościelski (9 November 1845, Służewo - 22 June 1911, Poznań) was a Polish poet, politician and parliamentarian, co-founder of the Straż (Guard) society.

References

* Witold Jakóbczyk

Witold Jakóbczyk (; 15 January 1909 in Sosn ...

(1845–1911), Polish politician and parliamentarian, co-founder of the Straż (Guard) society

* Józef Krzymiński (1858–1940), Polish physician, social and political activist, member of parliament

* Władysław Marcinkowski (1858–1947), Polish sculptor who created a monument of Adam Mickiewicz in Milosław

* Bernd Baron von Maydell

Bernd Baron von Maydell (1934–2018), also ''Berend F. von Maydell'', was a German lawyer and secondary school teacher, who specialised in social law.

Life

Bernd Baron von Maydell, also ''Berend F. von Maydell'', was born on 19 July 1934 in T ...

(1934–2018), German lawyer and author

* Władysław Niegolewski (1819–85), Polish liberal politician and member of parliament, insurgent in 1846, 1848 and 1863, cofounder of TCL and CTG

* Cyryl Ratajski

Cyryl Ratajski (3 March 1875 – 19 October 1942) was a Polish politician and lawyer.

Life and career

Ratajski was born in Zalesie Wielkie, then part of the German Empire, on 3 March 1875. He graduated from a high school in Poznań and s ...

(1875–1942), president of Poznań 1922–34

* Arthur Ruppin (1876–1943), pioneering sociologist, Zionist thinker and leader, co-founder of Tel Aviv

* Karol Rzepecki

Karol Rzepecki (21 June 1865 in Poznań – 14 December 1931 in Poznań) was a Polish bookseller, social and political activist, editor of Sokół (Falcon) magazine.

References

* Witold Jakóbczyk

Witold Jakóbczyk (; 15 January 1909 in Sos ...

(1865–1931), Polish bookseller, social and political activist, editor of Sokół (Falcon) magazine

* Antoni Stychel (1859–1935), Polish priest, member of parliament, president of the Union of the Catholic Societies of Polish Workers

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

(Związek Katolickich Towarzystw Robotników Polskich)

* Roman Szymański

Roman Szymański (4 August 1840, Kostrzyn - 18 December 1908, Poznań) was a Polish political activist, publicist, editor of Orędownik magazine.

References

* Witold Jakóbczyk

Witold Jakóbczyk (; 15 January 1909 in Sosnowiec – 3 October ...

(1840–1908), Polish political activist, publicist, editor of '' Orędownik'' magazine

*Alfred Trzebinski

Alfred Trzebinski (29 August 1902 – 8 October 1946) was an SS-physician at the Auschwitz, Majdanek and Neuengamme concentration camps in Nazi Germany. He was sentenced to death and executed for his involvement in war crimes committed at the N ...

(1902–1946), SS-physician at several Nazi concentration camps executed for war crimes

* Aniela Tułodziecka

Aniela Tułodziecka (2 October 1853 in Dąbrowa Stara, Kingdom of Prussia - 11 October 1932 in Poznań) was a Polish educational activist of the Warta Society (Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Wzajemnego Pouczania się i Opieki nad Dziećmi Warta).

Ref ...

(1853–1932), Polish educational activist of the Warta Society

The river Warta ( , ; german: Warthe ; la, Varta) rises in central Poland and meanders greatly north-west to flow into the Oder, against the German border. About long, it is Poland's second-longest river within its borders after the Vistula, a ...

(Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Wzajemnego Pouczania się i Opieki nad Dziećmi Warta)

* Piotr Wawrzyniak

Piotr Wawrzyniak (30 January 1849 in Wyrzeka – 9 November 1910 in Poznań) was a Polish priest, economic and educational activist, patron of the Union of the Earnings and Economic Societies (Związek Spółek Zarobkowych i Gospodarczych).

Ref ...

(1849–1910), Polish priest, economic and educational activist, patron of Union of the Earnings and Economic Societies (Związek Spółek Zarobkowych i Gospodarczych)

Notes

References

External links

*Administrative subdivision of the province (in 1910)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Posen, Province Of Provinces of Prussia Prussian Partition History of Poznań 1848 establishments in Prussia 1919 disestablishments in Germany Former eastern territories of Germany