Partus Sequitur Ventrem on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Partus sequitur ventrem'' (L. "That which is born follows the womb"; also ''partus'') was a legal doctrine passed in colonial Virginia in 1662 and other English

''Partus sequitur ventrem'' (L. "That which is born follows the womb"; also ''partus'') was a legal doctrine passed in colonial Virginia in 1662 and other English

41 ''Akron Law Review'' 799 (2008), Digital Commons Law, University of Maryland Law School, accessed 21 April 2009. The doctrine also meant that multiracial children with

Monticello Website, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, accessed 22 June 2011. Quote: "Ten years later eferring to their 2000 report TJF and most historians now believe that, years after his wife's death, Thomas Jefferson was the father of the six children of Sally Hemings mentioned in Jefferson's records, including Beverly, Harriet, Madison and Eston Hemings." Under Virginia law at the time, being seven-eighths European (“octoroon”) would have made the Jefferson–Hemings children legally white, if they’d been free. Jefferson allowed the two eldest to "escape", and freed the two youngest in his will. As adults, three of the Jefferson–Hemings children passed into white society: Beverly and Harriet Hemings in the Washington, DC area, and

Under Virginia law at the time, being seven-eighths European (“octoroon”) would have made the Jefferson–Hemings children legally white, if they’d been free. Jefferson allowed the two eldest to "escape", and freed the two youngest in his will. As adults, three of the Jefferson–Hemings children passed into white society: Beverly and Harriet Hemings in the Washington, DC area, and

''Partus sequitur ventrem'' (L. "That which is born follows the womb"; also ''partus'') was a legal doctrine passed in colonial Virginia in 1662 and other English

''Partus sequitur ventrem'' (L. "That which is born follows the womb"; also ''partus'') was a legal doctrine passed in colonial Virginia in 1662 and other English crown colonies

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony administered by The Crown within the British Empire. There was usually a Governor, appointed by the British monarch on the advice of the UK Government, with or without the assistance of a local Council ...

in the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

which defined the legal status of children born there; the doctrine mandated that all children would inherit the legal status of their mothers. As such, children of enslaved women would be born into slavery. The legal doctrine of ''partus sequitur ventrem'' was derived from Roman civil law, specifically the portions concerning slavery and personal property ( chattels).

The doctrine's most significant effect was placing into chattel slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to per ...

all children born to enslaved women. ''Partus sequitur ventrem'' soon spread from the colony of Virginia to all of the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th centu ...

. As a function of the political economy

Political economy is the study of how economic systems (e.g. markets and national economies) and political systems (e.g. law, institutions, government) are linked. Widely studied phenomena within the discipline are systems such as labour ...

of chattel slavery in Colonial America, the legalism of ''partus sequitur ventrem'' exempted the biological father from relationship toward children he fathered with enslaved women, and gave all rights in the children to the slave owner. The denial of paternity to enslaved children secured the slaveholders' right to profit from exploiting the labour of children engendered, bred, and born into slavery.Lovell Banks, Taunya "Dangerous Woman: Elizabeth Key's Freedom Suit — Subjecthood and Racialized Identity in Seventeenth century Colonial Virginia"41 ''Akron Law Review'' 799 (2008), Digital Commons Law, University of Maryland Law School, accessed 21 April 2009. The doctrine also meant that multiracial children with

white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White ...

mothers were born free. Early generations of Free Negros in the American South

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

were formed from unions between free working-class, usually mixed race women, and black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white ha ...

men.

Similar legal doctrines also derived from the civil law, operated in all the various European colonies in the Americas and Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

which were established by the British, Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

, Portuguese, French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

, or Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

.M.H.Davidson (1997) ''Columbus Then and Now, a life re-examined. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press'', p. 417)

History

Background

In 1619, a group of "twenty and odd" Negroes were landed in theColony of Virginia

The Colony of Virginia, chartered in 1606 and settled in 1607, was the first enduring English colony in North America, following failed attempts at settlement on Newfoundland by Sir Humphrey GilbertGilbert (Saunders Family), Sir Humphrey" (histor ...

, marking the beginning of the importation of Africans in England's colonies in continental North America. They had been captured from a Portuguese slaver, the Portuguese having begun the Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and ...

a century earlier. During the colonial era, English colonial administration struggled to determine the status of the children born in the colonies, where their births were the product of a union between an English subject and a "foreigner", or entirely between foreigners.

English common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omniprese ...

mandated that the legal place or status of an English subject's children was based on that of their father as the head of the household, known as ''pater familias''. Common law stipulated that men were legally required to acknowledge their bastard children in addition to their legal ones, and give them food and shelter - while they also had the right to put their children to work or hire them out taking any earnings, or arranging an apprenticeship

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

or indenture

An indenture is a legal contract that reflects or covers a debt or purchase obligation. It specifically refers to two types of practices: in historical usage, an indentured servant status, and in modern usage, it is an instrument used for commercia ...

so that they could become a self-supporting adult. Child labor was a critical benefit both to the family headed by a father in England, and to the development of England's colonies - the child was as property to the father, or to those who stood in place of the father, but the child grew out of that condition as they came of age.

Regarding personal property

property is property that is movable. In common law systems, personal property may also be called chattels or personalty. In civil law systems, personal property is often called movable property or movables—any property that can be moved fr ...

(chattels), common law mandated that the profits and increase generated by personal property (live stock, mobile property) accrued to the owner of the chattel property. Beginning in the Virginia royal colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony administered by The Crown within the British Empire. There was usually a Governor, appointed by the British monarch on the advice of the UK Government, with or without the assistance of a local Coun ...

in 1662, colonial governments incorporated the legal doctrine of ''partus sequitur ventrem'' into the laws of slavery, ruling that the children born in the colonies took the place or status of their mothers; therefore, children of enslaved mothers were born into slavery as chattel, regardless of the status of their fathers. The doctrine existed in English common law (which agreed with the civil law in such matters as live stock) but in England the ''partus sequitur ventrem'' doctrine did not make chattels of English subjects.

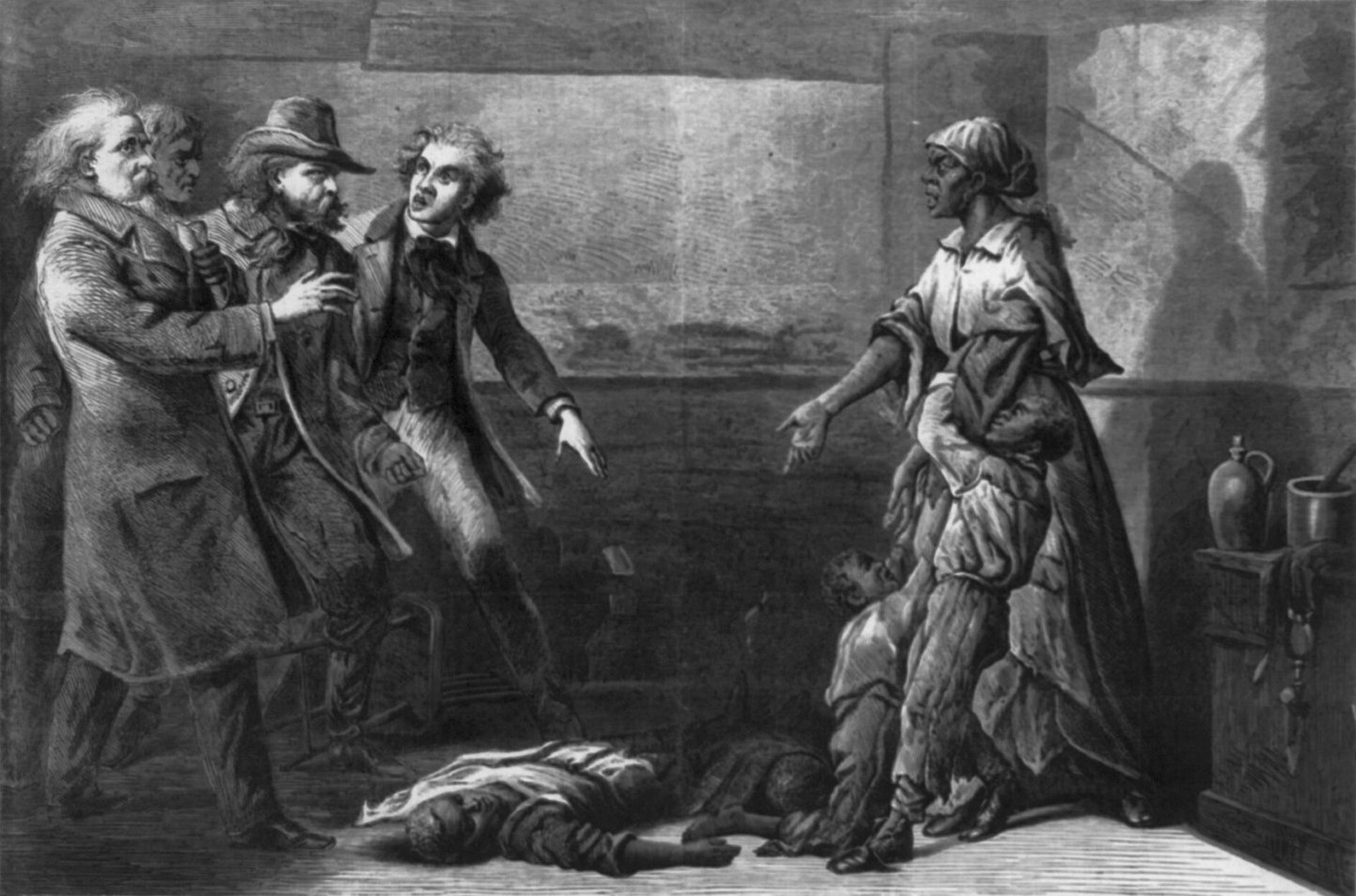

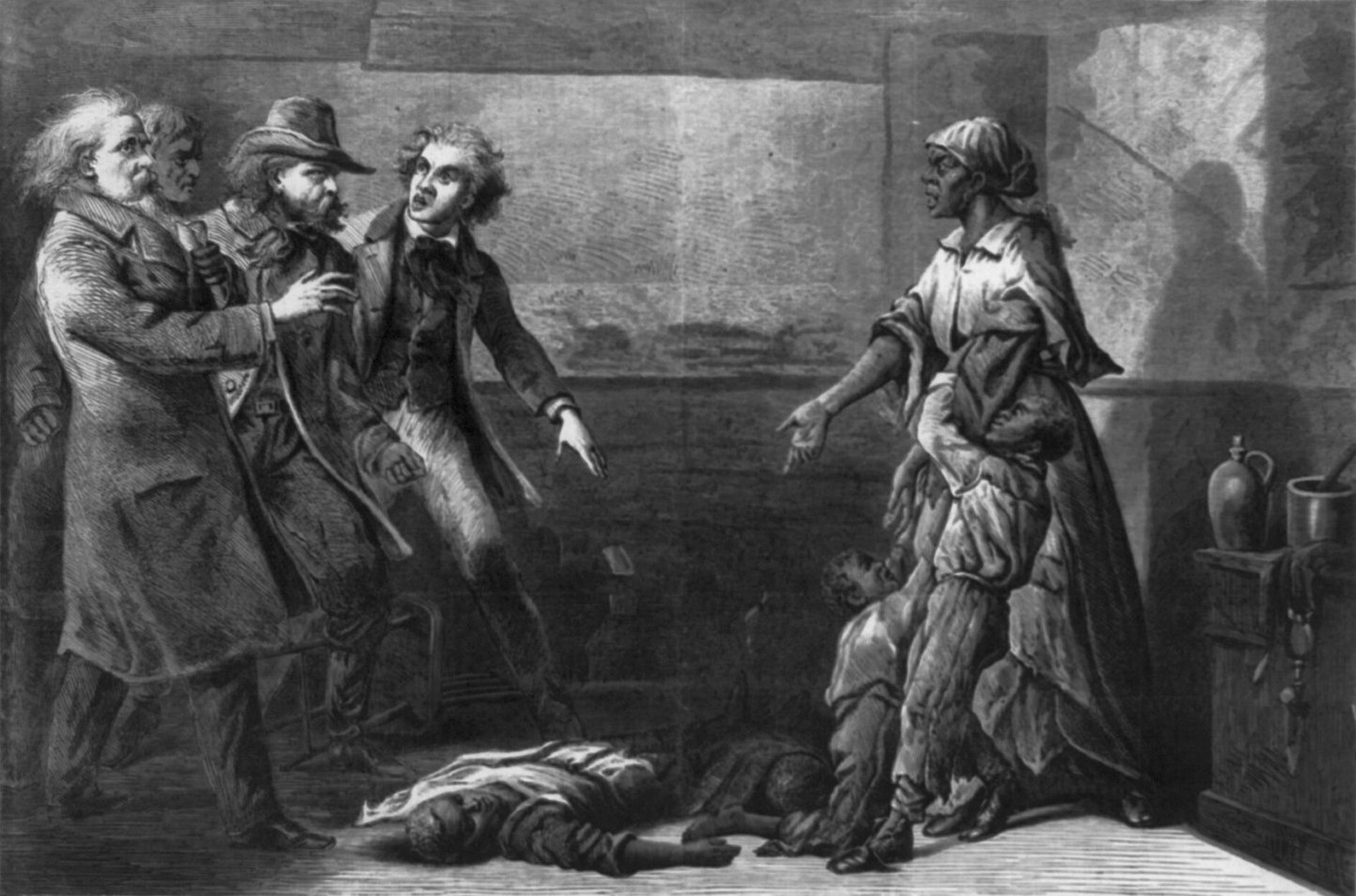

In 1656, multiracial

Mixed race people are people of more than one race or ethnicity. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mixed race people in a variety of contexts, including ''multiethnic'', ''polyethnic'', occasionally ''bi-eth ...

woman Elizabeth Key Grinstead

Elizabeth Key Grinstead (Greenstead) (1630 – January 20, 1665) was one of the first black people of the Thirteen Colonies to sue for freedom from slavery and win. Key won her freedom and that of her infant son John Grinstead on July 21, 1656, i ...

, then illegally classified as being enslaved, won her freedom lawsuit and legal recognition as a free woman of color in colonial Virginia. Key's successful lawsuit was based upon the circumstances of her birth: her English father was a member of the House of Burgesses

The House of Burgesses was the elected representative element of the Virginia General Assembly, the legislative body of the Colony of Virginia. With the creation of the House of Burgesses in 1642, the General Assembly, which had been establishe ...

; had acknowledged his paternity of Elizabeth, who was baptized as a Christian in the Church of England; and, before his death, had arranged a guardianship for her, by way of indentured servitude

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an " indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayme ...

until she came of age. When the man to whom Key was indentured returned to England, he sold her indenture contract to a second man. The latter prolonged Key's servitude beyond the indenture's original term. At the death of the second owner of her indenture, his estate classified Elizabeth Key and her mixed-race son (who also had a white father, William Grinstead), as "Negro slaves" who were personal property of the deceased. Elizabeth, with William acting as her attorney, sued the estate over her status, claiming that she was an indentured servant who had served past her term and that her son was thus freeborn

"Freeborn" is a term associated with political agitator John Lilburne (1614–1657), a member of the Levellers, a 17th-century English political party. As a word, "freeborn" means born free, rather than in slavery or bondage or vassalage. Lilbur ...

. This was eventually accepted by the Virginia General Court, though it overturned the decision after an appeal from the estate. Elizabeth took the case to the Virginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, the oldest continuous law-making body in the Western Hemisphere, the first elected legislative assembly in the New World, and was established on July 30, 16 ...

, which accepted her arguments.

According to scholar Taunya Lovell Banks,

children born to English parents outside the country became English subjects at birth, others could become "naturalized subjects" (although there was no process at the time in the colonies). What was unsettled was the status of children if only one of the parents was an English subject, as foreigners (including Africans) were not considered subjects. Because non-whites came to be denied civil rights as foreigners, mixed-race people seeking freedom often had to stress their English ancestry (and later, European).As a direct result of freedom suits such as those filed by Elizabeth, the Virginian

House of Burgesses

The House of Burgesses was the elected representative element of the Virginia General Assembly, the legislative body of the Colony of Virginia. With the creation of the House of Burgesses in 1642, the General Assembly, which had been establishe ...

passed the legal doctrine of ''partus sequitur ventrem'', noting that “doubts have arisen whether children got by an Englishmen upon a negro woman should be slave or free”.

After the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

, slave law in the United States continued to maintain such distinctions. Virginia established a law that no one could be a slave in the state other than those who had that status on October 17, 1785 "and the descendants of the females of them." Kentucky adopted this law in 1798; Mississippi passed a similar law in 1822, using the phrase about females and their descendants; as did Florida in 1828. Louisiana, whose legal system was based on civil law (following its French colonial past), in 1825 added this language to its code: "Children born of a mother then in a state of slavery, whether married or not, follow the condition of their mother." Other states adopted this "norm" through judicial rulings. In summary, the legal doctrine of ''partus sequitur ventrem'' functioned economically to provide a steady supply of slaves.

Mixed-race slaves

By the 18th century, the colonial slave population included mixed-race children of white ancestry, such asmulatto

(, ) is a racial classification to refer to people of mixed African and European ancestry. Its use is considered outdated and offensive in several languages, including English and Dutch, whereas in languages such as Spanish and Portuguese ...

es (half Black), quadroon

In the colonial societies of the Americas and Australia, a quadroon or quarteron was a person with one quarter African/ Aboriginal and three quarters European ancestry.

Similar classifications were octoroon for one-eighth black (Latin root ''oc ...

s (one-quarter Black), and octoroons (one-eighth Black). They were fathered by white planters, overseers, and other men with power, with enslaved women who were also sometimes of mixed race.

Numerous mixed-race slaves lived in stable families at the Monticello

Monticello ( ) was the primary plantation of Founding Father Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, who began designing Monticello after inheriting land from his father at age 26. Located just outside Charlottesville, V ...

plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Th ...

of Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

. In 1773 his wife, Martha Wayles, inherited more than one hundred slaves from her father John Wayles

John Wayles (January 31, 1715 – May 28, 1773) was a colonial American planter, slave trader and lawyer in colonial Virginia. He is historically best known as the father-in-law of Thomas Jefferson, the third President of the United States ...

. These included the six mixed-race children (three-quarters white) whom he fathered with his enslaved concubine Betty Hemings, a mulatto born of an Englishman and an enslaved African (Black) woman. Martha Wayles's three-quarters white (“quadroon”) half-brothers and half-sisters included the much younger Sally Hemings

Sarah "Sally" Hemings ( 1773 – 1835) was an enslaved woman with one-quarter African ancestry owned by president of the United States Thomas Jefferson, one of many he inherited from his father-in-law, John Wayles.

Hemings's mother Elizabet ...

. Some years later, the widower Jefferson took Sally Hemings (then between 14 and 16 years of age) as a concubine. Over 38 years, he had six children with her, four of whom survived to adulthood. As their mother was enslaved, they too were enslaved from birth."Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: A Brief Account"Monticello Website, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, accessed 22 June 2011. Quote: "Ten years later eferring to their 2000 report TJF and most historians now believe that, years after his wife's death, Thomas Jefferson was the father of the six children of Sally Hemings mentioned in Jefferson's records, including Beverly, Harriet, Madison and Eston Hemings."

Under Virginia law at the time, being seven-eighths European (“octoroon”) would have made the Jefferson–Hemings children legally white, if they’d been free. Jefferson allowed the two eldest to "escape", and freed the two youngest in his will. As adults, three of the Jefferson–Hemings children passed into white society: Beverly and Harriet Hemings in the Washington, DC area, and

Under Virginia law at the time, being seven-eighths European (“octoroon”) would have made the Jefferson–Hemings children legally white, if they’d been free. Jefferson allowed the two eldest to "escape", and freed the two youngest in his will. As adults, three of the Jefferson–Hemings children passed into white society: Beverly and Harriet Hemings in the Washington, DC area, and Eston Hemings

Eston is a Village in the borough of Redcar and Cleveland, North Yorkshire, England. The ward covering the area (as well as Lackenby, Lazenby and Wilton) had a population of 7,005 at the 2011 census. It is part of Greater Eston, which inc ...

Jefferson in Wisconsin. He had married a mixed-race woman in Virginia, and both their sons served as regular Union soldiers. The oldest gained the rank of colonel.

Historians had long discounted rumors that Jefferson had this relationship. But in 1998, a Y-DNA test confirmed that a contemporary male descendant of Sally Hemings (through Eston Heming's descendants) was a direct, genetic descendant of the male line of Jeffersons. It was Thomas Jefferson who was documented as having been at Monticello each time Hemings conceived, and the weight of historical evidence favored his paternity.

Mixed-race communities in the Deep South

In the colonial cities on the Gulf of Mexico, New Orleans, Savannah, and Charleston, there arose theCreole peoples

Creole peoples are ethnic groups formed during the European colonial era, from the mass displacement of peoples brought into sustained contact with others from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds, who converged onto a colonial ter ...

as a social class of educated free people of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (French: ''gens de couleur libres''; Spanish: ''gente de color libre'') were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not ...

, descended from white fathers and enslaved black or mixed-race women. As a class, they intermarried, sometimes gained formal education, and owned property, including slaves. Moreover, in the Upper South

The Upland South and Upper South are two overlapping cultural and geographic subregions in the inland part of the Southern and lower Midwestern United States. They differ from the Deep South and Atlantic coastal plain by terrain, history, econom ...

, some slaveholders freed their slaves after the Revolution through manumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

. The population of free black men and free black women rose from less than 1% in 1780 to more than 10% in 1810, when 7.2% of Virginia's population was free black people, and 75% of Delaware's black population were free.

Concerning the sexual hypocrisy related to whites and their sexual abuse of enslaved women, the diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut

Mary Boykin Chesnut (née Miller) (March 31, 1823 – November 22, 1886) was an American author noted for a book published as her Civil War diary, a "vivid picture of a society in the throes of its life-and-death struggle."Woodward, C. Vann. "In ...

said:

This only I see: like the patriarchs of old our men live all in one house with their wives and their concubines, the Mulattoes one sees in every family exactly resemble the white children — every lady tells you who is the father of all the Mulatto children in every body's household, but those ulatto childrenin her own ousehold she seems to think drop from the clouds or pretends so to think ...Likewise, in the ''Journal of a Residence on a Georgia Plantation in 1838–1839'' (1863),

Fanny Kemble

Frances Anne "Fanny" Kemble (27 November 180915 January 1893) was a British actress from a theatre family in the early and mid-19th century. She was a well-known and popular writer and abolitionist, whose published works included plays, poetry ...

, the English wife of an American planter, noted the immorality of white slave owners who kept their mixed-race children enslaved.

But some white fathers established common-law marriages with enslaved women. They manumitted the woman and children, or sometimes transferred property to them, arranged apprenticeships and education, and resettled in the North. Some white fathers paid for higher education of their mixed-race children at colour-blind colleges, such as Oberlin College

Oberlin College is a private liberal arts college and conservatory of music in Oberlin, Ohio. It is the oldest coeducational liberal arts college in the United States and the second oldest continuously operating coeducational institute of highe ...

. In 1860 Ohio, at Wilberforce University

Wilberforce University is a private historically black university in Wilberforce, Ohio. Affiliated with the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), it was the first college to be owned and operated by African Americans. It participates i ...

(est. 1855) owned and operated by the African Methodist Episcopal

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the AME Church or AME, is a predominantly African American Methodist denomination. It adheres to Wesleyan-Arminian theology and has a connexional polity. The African Methodist Episcopal ...

church, most of the two hundred subscribed students were mixed-race, natural sons of the white men paying their tuition.

See also

* History of sexual slavery in the United States * Female slavery in the United States * Enslaved women's resistance in the United States and Caribbean * Marriage of enslaved people (United States) * Children of the plantation * Slave breeding in the United States *Freedom of wombs

Freedom of wombs ( es, Libertad de vientres, pt, Lei do Ventre Livre), also referred to as free birth or the law of wombs, was a 19th century judicial concept in several Latin American countries, that declared that all wombs bore free children. A ...

* Rio Branco Law

The Rio Branco law (), also known as the Law of Free Birth (), named after its champion, Prime Minister José Paranhos, Viscount of Rio Branco, was passed by the Brazilian Parliament on September 28 in 1871. It was intended to provide freedom ...

* Slave Trade Act

Slave Trade Act is a stock short title used for legislation in the United Kingdom and the United States that relates to the slave trade.

The "See also" section lists other Slave Acts, laws, and international conventions which developed the c ...

s

* Sally Miller

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Partus Sequitur Ventrem Slavery in the United States Legal history of the United States Legal rules with Latin names Multiracial affairs in the United States Native American history Pre-emancipation African-American history Slavery of Native Americans