parachutes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A parachute is a device used to slow the motion of an object through an

The earliest evidence for the true parachute dates back to the

The earliest evidence for the true parachute dates back to the  The

The

atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gas or layers of gases that envelop a planet, and is held in place by the gravity of the planetary body. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A ...

by creating drag or, in a ram-air parachute, aerodynamic lift

Lift or LIFT may refer to:

Physical devices

* Elevator, or lift, a device used for raising and lowering people or goods

** Paternoster lift, a type of lift using a continuous chain of cars which do not stop

** Patient lift, or Hoyer lift, mobil ...

. A major application is to support people, for recreation or as a safety device for aviators, who can exit from an aircraft at height and descend safely to earth.

A parachute is usually made of a light, strong fabric. Early parachutes were made of silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from th ...

. The most common fabric today is nylon

Nylon is a generic designation for a family of synthetic polymers composed of polyamides ( repeating units linked by amide links).The polyamides may be aliphatic or semi-aromatic.

Nylon is a silk-like thermoplastic, generally made from pet ...

. A parachute's canopy is typically dome-shaped, but some are rectangles, inverted domes, and other shapes.

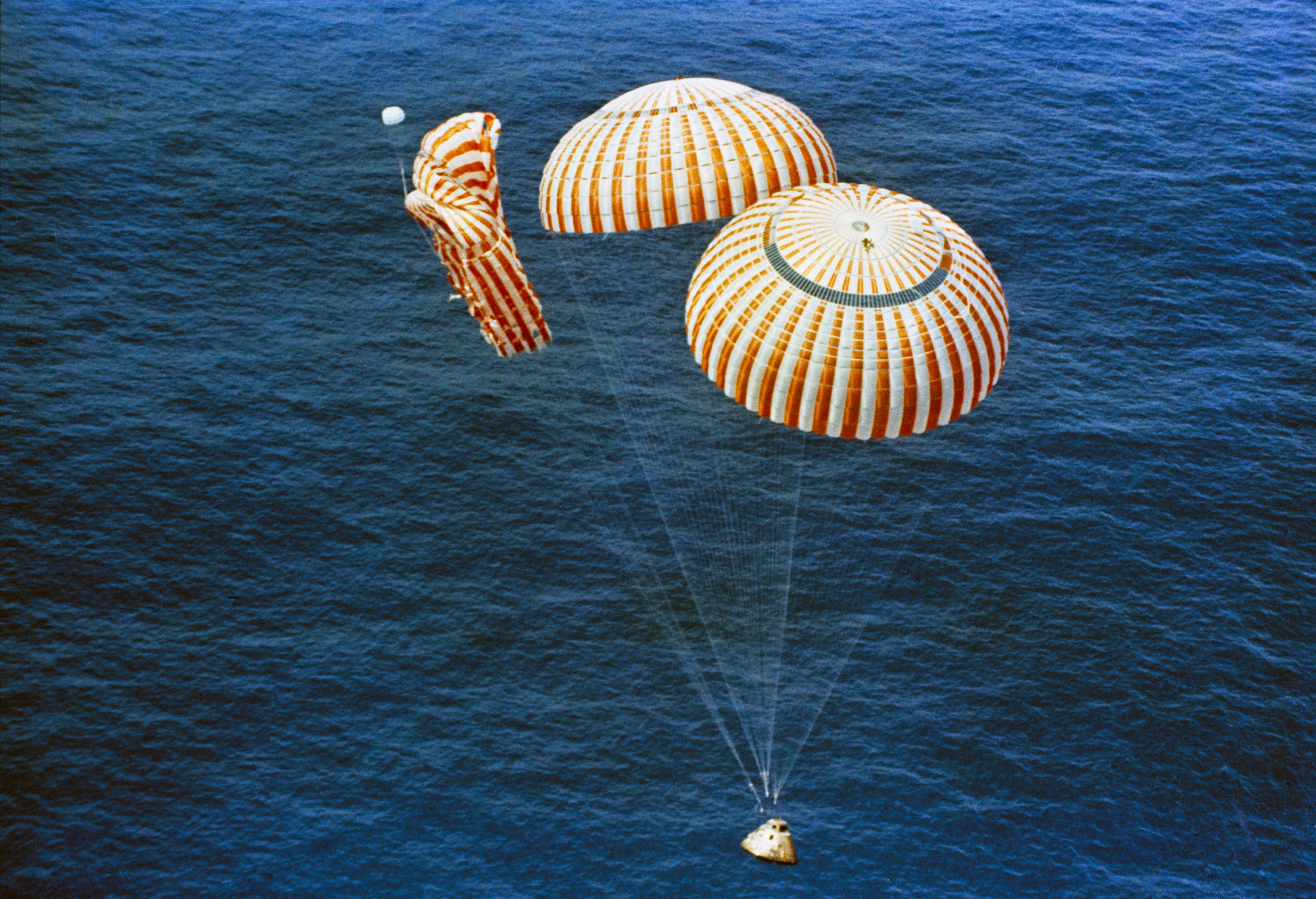

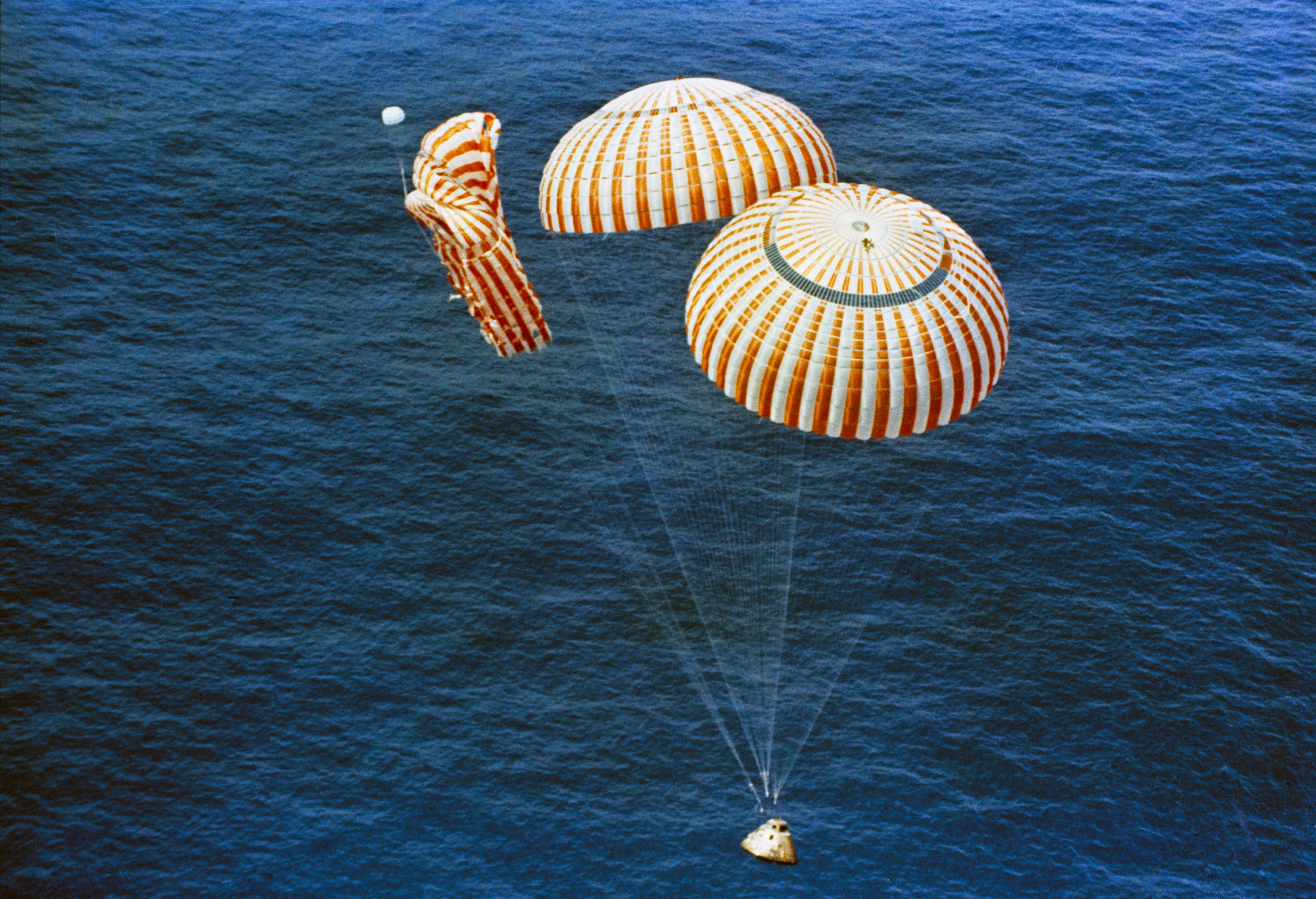

A variety of loads are attached to parachutes, including people, food, equipment, space capsule

A space capsule is an often-crewed spacecraft that uses a blunt-body reentry capsule to reenter the Earth's atmosphere without wings. Capsules are distinguished from other satellites primarily by the ability to survive reentry and return a payl ...

s, and bombs

A bomb is an explosive weapon that uses the exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy. Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-transmitted mechanic ...

.

History

Middle Ages

In 852, inCórdoba, Spain

Córdoba (; ),, Arabic: قُرطبة DIN: . or Cordova () in English, is a city in Andalusia, Spain, and the capital of the province of Córdoba. It is the third most populated municipality in Andalusia and the 11th overall in the country.

The ...

, the Moorish man Armen Firman attempted unsuccessfully to fly by jumping from a tower while wearing a large cloak. It was recorded that "there was enough air in the folds of his cloak to prevent great injury when he reached the ground."

Early Renaissance

The earliest evidence for the true parachute dates back to the

The earliest evidence for the true parachute dates back to the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

period. The oldest parachute design appears in an anonymous manuscript from 1470s Renaissance Italy

The Italian Renaissance ( it, Rinascimento ) was a period in Italian history covering the 15th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Europe and marked the trans ...

(British Library, Add MS 34113, fol. 200v), showing a free-hanging man clutching a crossbar frame attached to a conical canopy. As a safety measure, four straps ran from the ends of the rods to a waist belt. The design is a marked improvement over another folio (189v), which depicts a man trying to break the force of his fall using two long cloth streamers fastened to two bars, which he grips with his hands. Although the surface area of the parachute design appears to be too small to offer effective air resistance and the wooden base-frame is superfluous and potentially harmful, the basic concept of a working parachute is apparent.

Shortly after, a more sophisticated parachute was sketched by the polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested on ...

in his ''Codex Atlanticus

The Codex Atlanticus (Atlantic Codex) is a 12-volume, bound set of drawings and writings (in Italian) by Leonardo da Vinci, the largest single set. Its name indicates the large paper used to preserve original Leonardo notebook pages, which was u ...

'' (fol. 381v) dated to ca. 1485. Here, the scale of the parachute is in a more favorable proportion to the weight of the jumper. A square wooden frame, which alters the shape of the parachute from conical to pyramidal, held open Leonardo's canopy. It is not known whether the Italian inventor was influenced by the earlier design, but he may have learned about the idea through the intensive oral communication among artist-engineers of the time. The feasibility of Leonardo's pyramidal design was successfully tested in 2000 by Briton

British people or Britons, also known colloquially as Brits, are the citizens of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the British Overseas Territories, and the Crown dependencies.: British nationality law governs mod ...

Adrian Nicholas and again in 2008 by the Swiss skydiver Olivier Vietti-Teppa. According to historian of technology Lynn White, these conical and pyramidal designs, much more elaborate than early artistic jumps with rigid parasol

An umbrella or parasol is a folding canopy (building), canopy supported by wooden or metal ribs that is usually mounted on a wooden, metal, or plastic pole. It is designed to protect a person against rain or sunburn, sunlight. The term ''umbr ...

s in Asia, mark the origin of "the parachute as we know it."

The

The Venetian

Venetian often means from or related to:

* Venice, a city in Italy

* Veneto, a region of Italy

* Republic of Venice (697–1797), a historical nation in that area

Venetian and the like may also refer to:

* Venetian language, a Romance language s ...

polymath and inventor Fausto Veranzio

Fausto Veranzio ( la, Faustus Verantius; hr, Faust Vrančić; Hungarian and Vernacular Latin: ''Verancsics Faustus'';Andrew L. SimonMade in Hungary: Hungarian contributions to universal culture/ref> A now-famous depiction of a parachute that he dubbed ''Homo Volans'' (Flying Man), showing a man parachuting from a tower, presumably

The modern parachute was invented in the late 18th century by Louis-Sébastien Lenormand in

The modern parachute was invented in the late 18th century by Louis-Sébastien Lenormand in

In 1907 Charles Broadwick demonstrated two key advances in the parachute he used to jump from

In 1907 Charles Broadwick demonstrated two key advances in the parachute he used to jump from  In 1912, on a road near

In 1912, on a road near

Matematický ústav, Slovenská akadémia vied, obituary. Retrieved 21 October 2010. Banič had been the first person to patent the parachute, and his design was the first to properly function in the 20th century. On June 21, 1913,

The first military use of the parachute was by

The first military use of the parachute was by

The experience with parachutes during the war highlighted the need to develop a design that could be reliably used to exit a disabled airplane. For instance, tethered parachutes did not work well when the aircraft was spinning. After the war, Major Edward L. Hoffman of the

The experience with parachutes during the war highlighted the need to develop a design that could be reliably used to exit a disabled airplane. For instance, tethered parachutes did not work well when the aircraft was spinning. After the war, Major Edward L. Hoffman of the

Round parachutes are purely a drag device (that is, unlike the ram-air types, they provide no

Round parachutes are purely a drag device (that is, unlike the ram-air types, they provide no

A variation on the round parachute is the pull-down apex parachute, invented by a Frenchman named Pierre-Marcel Lemoigne. The first widely used canopy of this type was called the ''Para-Commander'' (made by the Pioneer Parachute Co.), although there are many other canopies with a pull-down apex produced in the years thereafter - these had minor differences in attempts to make a higher performance rig, such as different venting configurations. They are all considered 'round' parachutes, but with suspension lines to the canopy apex that apply load there and pull the apex closer to the load, distorting the round shape into a somewhat flattened or lenticular shape when viewed from the side. And while called ''rounds'', they generally have an elliptical shape when viewed from above or below, with the sides bulging out more than the for'd-and-aft dimension, the chord (see the lower photo to the right and you likely can ascertain the difference).

Due to their lenticular shape and appropriate venting, they have a considerably faster forward speed than, say, a modified military canopy. And due to controllable rear-facing vents in the canopy's sides, they also have much snappier turning capabilities, though they are decidedly low-performance compared to today's ram-air rigs. From about the mid-1960s to the late-1970s, this was the most popular parachute design type for sport parachuting (prior to this period, modified military 'rounds' were generally used and after, ram-air 'squares' became common). Note that the use of the word ''elliptical'' for these 'round' parachutes is somewhat dated and may cause slight confusion, since some 'squares' (i.e. ram-airs) are elliptical nowadays, too.

A variation on the round parachute is the pull-down apex parachute, invented by a Frenchman named Pierre-Marcel Lemoigne. The first widely used canopy of this type was called the ''Para-Commander'' (made by the Pioneer Parachute Co.), although there are many other canopies with a pull-down apex produced in the years thereafter - these had minor differences in attempts to make a higher performance rig, such as different venting configurations. They are all considered 'round' parachutes, but with suspension lines to the canopy apex that apply load there and pull the apex closer to the load, distorting the round shape into a somewhat flattened or lenticular shape when viewed from the side. And while called ''rounds'', they generally have an elliptical shape when viewed from above or below, with the sides bulging out more than the for'd-and-aft dimension, the chord (see the lower photo to the right and you likely can ascertain the difference).

Due to their lenticular shape and appropriate venting, they have a considerably faster forward speed than, say, a modified military canopy. And due to controllable rear-facing vents in the canopy's sides, they also have much snappier turning capabilities, though they are decidedly low-performance compared to today's ram-air rigs. From about the mid-1960s to the late-1970s, this was the most popular parachute design type for sport parachuting (prior to this period, modified military 'rounds' were generally used and after, ram-air 'squares' became common). Note that the use of the word ''elliptical'' for these 'round' parachutes is somewhat dated and may cause slight confusion, since some 'squares' (i.e. ram-airs) are elliptical nowadays, too.

Ribbon and ring parachutes have similarities to annular designs. They are frequently designed to deploy at

Ribbon and ring parachutes have similarities to annular designs. They are frequently designed to deploy at

Personal ram-air parachutes are loosely divided into two varieties – rectangular or tapered – commonly called "squares" or "ellipticals", respectively. Medium-performance canopies (reserve-, BASE-, canopy formation-, and accuracy-type) are usually rectangular. High-performance, ram-air parachutes have a slightly tapered shape to their leading and/or trailing edges when viewed in plan form, and are known as ellipticals. Sometimes all the taper is on the leading edge (front), and sometimes in the trailing edge (tail).

Ellipticals are usually used only by sport parachutists. They often have smaller, more numerous fabric cells and are shallower in profile. Their canopies can be anywhere from slightly elliptical to highly elliptical, indicating the amount of taper in the canopy design, which is often an indicator of the responsiveness of the canopy to control input for a given wing loading, and of the level of experience required to pilot the canopy safely.

The rectangular parachute designs tend to look like square, inflatable air mattresses with open front ends. They are generally safer to operate because they are less prone to dive rapidly with relatively small control inputs, they are usually flown with lower wing loadings per square foot of area, and they glide more slowly. They typically have a lower

Personal ram-air parachutes are loosely divided into two varieties – rectangular or tapered – commonly called "squares" or "ellipticals", respectively. Medium-performance canopies (reserve-, BASE-, canopy formation-, and accuracy-type) are usually rectangular. High-performance, ram-air parachutes have a slightly tapered shape to their leading and/or trailing edges when viewed in plan form, and are known as ellipticals. Sometimes all the taper is on the leading edge (front), and sometimes in the trailing edge (tail).

Ellipticals are usually used only by sport parachutists. They often have smaller, more numerous fabric cells and are shallower in profile. Their canopies can be anywhere from slightly elliptical to highly elliptical, indicating the amount of taper in the canopy design, which is often an indicator of the responsiveness of the canopy to control input for a given wing loading, and of the level of experience required to pilot the canopy safely.

The rectangular parachute designs tend to look like square, inflatable air mattresses with open front ends. They are generally safer to operate because they are less prone to dive rapidly with relatively small control inputs, they are usually flown with lower wing loadings per square foot of area, and they glide more slowly. They typically have a lower

Paragliders - virtually all of which use ram-air canopies - are more akin to today's sport parachutes than, say, parachutes of the mid-1970s and earlier. Technically, they are ''ascending parachutes'', though that term is not used in the paragliding community, and they have the same basic airfoil design of today's 'square' or 'elliptical' sports

Paragliders - virtually all of which use ram-air canopies - are more akin to today's sport parachutes than, say, parachutes of the mid-1970s and earlier. Technically, they are ''ascending parachutes'', though that term is not used in the paragliding community, and they have the same basic airfoil design of today's 'square' or 'elliptical' sports

Reserve parachutes usually have a ripcord deployment system, which was first designed by Theodore Moscicki, but most modern main parachutes used by sports parachutists use a form of hand-deployed pilot chute. A ripcord system pulls a closing pin (sometimes multiple pins), which releases a spring-loaded pilot chute, and opens the container; the pilot chute is then propelled into the air stream by its spring, then uses the force generated by passing air to extract a deployment bag containing the parachute canopy, to which it is attached via a bridle. A hand-deployed pilot chute, once thrown into the air stream, pulls a closing pin on the pilot chute bridle to open the container, then the same force extracts the deployment bag. There are variations on hand-deployed pilot chutes, but the system described is the more common throw-out system.

Only the hand-deployed pilot chute may be collapsed automatically after deployment—by a kill line reducing the in-flight drag of the pilot chute on the main canopy. Reserves, on the other hand, do not retain their pilot chutes after deployment. The reserve deployment bag and pilot chute are not connected to the canopy in a reserve system. This is known as a free-bag configuration, and the components are sometimes not recovered after a reserve deployment.

Occasionally, a pilot chute does not generate enough force either to pull the pin or to extract the bag. Causes may be that the pilot chute is caught in the turbulent wake of the jumper (the "burble"), the closing loop holding the pin is too tight, or the pilot chute is generating insufficient force. This effect is known as "pilot chute hesitation," and, if it does not clear, it can lead to a total malfunction, requiring reserve deployment.

Paratroopers' main parachutes are usually deployed by static lines that release the parachute, yet retain the deployment bag that contains the parachute—without relying on a pilot chute for deployment. In this configuration, the deployment bag is known as a direct-bag system, in which the deployment is rapid, consistent, and reliable.

Reserve parachutes usually have a ripcord deployment system, which was first designed by Theodore Moscicki, but most modern main parachutes used by sports parachutists use a form of hand-deployed pilot chute. A ripcord system pulls a closing pin (sometimes multiple pins), which releases a spring-loaded pilot chute, and opens the container; the pilot chute is then propelled into the air stream by its spring, then uses the force generated by passing air to extract a deployment bag containing the parachute canopy, to which it is attached via a bridle. A hand-deployed pilot chute, once thrown into the air stream, pulls a closing pin on the pilot chute bridle to open the container, then the same force extracts the deployment bag. There are variations on hand-deployed pilot chutes, but the system described is the more common throw-out system.

Only the hand-deployed pilot chute may be collapsed automatically after deployment—by a kill line reducing the in-flight drag of the pilot chute on the main canopy. Reserves, on the other hand, do not retain their pilot chutes after deployment. The reserve deployment bag and pilot chute are not connected to the canopy in a reserve system. This is known as a free-bag configuration, and the components are sometimes not recovered after a reserve deployment.

Occasionally, a pilot chute does not generate enough force either to pull the pin or to extract the bag. Causes may be that the pilot chute is caught in the turbulent wake of the jumper (the "burble"), the closing loop holding the pin is too tight, or the pilot chute is generating insufficient force. This effect is known as "pilot chute hesitation," and, if it does not clear, it can lead to a total malfunction, requiring reserve deployment.

Paratroopers' main parachutes are usually deployed by static lines that release the parachute, yet retain the deployment bag that contains the parachute—without relying on a pilot chute for deployment. In this configuration, the deployment bag is known as a direct-bag system, in which the deployment is rapid, consistent, and reliable.

A parachute is carefully folded, or "packed" to ensure that it will open reliably. If a parachute is not packed properly it can result in a malfunction where the main parachute fails to deploy correctly or fully. In the United States and many developed countries, emergency and reserve parachutes are packed by " riggers" who must be trained and certified according to legal standards. Sport skydivers are always trained to pack their own primary "main" parachutes.

Exact numbers are difficult to estimate because parachute design, maintenance, loading, packing technique and operator experience all have a significant impact on malfunction rates. Approximately one in a thousand sport main parachute openings malfunctions, requiring the use of the reserve parachute, although some skydivers have many thousands of jumps and never needed to use their reserve parachute.

Reserve parachutes are packed and deployed somewhat differently. They are also designed more conservatively, favouring reliability over responsiveness and are built and tested to more exacting standards, making them more reliable than main parachutes. Regulated inspection intervals, coupled with significantly less use contributes to reliability as wear on some components can adversely affect reliability. The primary safety advantage of a reserve parachute comes from the

A parachute is carefully folded, or "packed" to ensure that it will open reliably. If a parachute is not packed properly it can result in a malfunction where the main parachute fails to deploy correctly or fully. In the United States and many developed countries, emergency and reserve parachutes are packed by " riggers" who must be trained and certified according to legal standards. Sport skydivers are always trained to pack their own primary "main" parachutes.

Exact numbers are difficult to estimate because parachute design, maintenance, loading, packing technique and operator experience all have a significant impact on malfunction rates. Approximately one in a thousand sport main parachute openings malfunctions, requiring the use of the reserve parachute, although some skydivers have many thousands of jumps and never needed to use their reserve parachute.

Reserve parachutes are packed and deployed somewhat differently. They are also designed more conservatively, favouring reliability over responsiveness and are built and tested to more exacting standards, making them more reliable than main parachutes. Regulated inspection intervals, coupled with significantly less use contributes to reliability as wear on some components can adversely affect reliability. The primary safety advantage of a reserve parachute comes from the

Below are listed the malfunctions specific to round parachutes.

* A "Mae West" or "blown periphery" is a type of round parachute malfunction that contorts the shape of the canopy into the outward appearance of a large

Below are listed the malfunctions specific to round parachutes.

* A "Mae West" or "blown periphery" is a type of round parachute malfunction that contorts the shape of the canopy into the outward appearance of a large

*The "

On August 16, 1960, Joseph Kittinger, in the Excelsior III test jump, set the previous world record for the highest parachute jump. He jumped from a

On August 16, 1960, Joseph Kittinger, in the Excelsior III test jump, set the previous world record for the highest parachute jump. He jumped from a

CSPA

The Canadian Sport Parachuting Association—The governing body for sport skydiving in Canada

– ''Scientific American'', June 7, 1913

Parachute History

Program Executive Office (PEO) Soldier

The 2nd FAI World Championships in Canopy Piloting – 2008 at Pretoria Skydiving Club South Africa

USPA

The United States Parachute Association—The governing body for sport skydiving in the U.S.

The Parachute History Collection at Linda Hall Library

(text-searchable PDFs)

"How Armies Hit The Silk"

June 1945, ''Popular Science'' James L. H. Peck – detailed article on parachutes

NuméroLa Revue aérienne / directeur Emile Mousset

First female parachutist

Everard Calthrop Parachutist - Drop From Tower Bridge Part 1 (1918)

Film of a successful parachute jump from Tower Bridge during World War I. {{authority control Parachuting Airborne military equipment French inventions Italian inventions Military parachuting Sports equipment

St Mark's Campanile

St Mark's Campanile ( it, Campanile di San Marco, ) is the bell tower of St Mark's Basilica in Venice, Italy. The current campanile is a reconstruction completed in 1912, the previous tower having collapsed in 1902. At in height, it is the tal ...

in Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

, appeared in his book on mechanics, ''Machinae Novae'' ("New Machines", published in 1615 or 1616), alongside a number of other devices and technical concepts.

It was once widely believed that in 1617, Veranzio, then aged 65 and seriously ill, implemented his design and tested the parachute by jumping from St Mark's Campanile, from a bridge nearby, or from St Martin's Cathedral in Bratislava

Bratislava (, also ; ; german: Preßburg/Pressburg ; hu, Pozsony) is the capital and largest city of Slovakia. Officially, the population of the city is about 475,000; however, it is estimated to be more than 660,000 — approximately 140% of ...

. Various publications incorrectly claimed the event was documented some thirty years later by John Wilkins

John Wilkins, (14 February 1614 – 19 November 1672) was an Anglican clergyman, natural philosopher, and author, and was one of the founders of the Royal Society. He was Bishop of Chester from 1668 until his death.

Wilkins is one of the ...

, founder and secretary of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, in his book '' Mathematical Magick or, the Wonders that may be Performed by Mechanical Geometry'', published in London in 1648. However, Wilkins wrote about flying, not parachutes, and does not mention Veranzio, a parachute jump, or any event in 1617. Doubts about this test, which include a lack of written evidence, suggest it never occurred, and was instead a misreading of historical notes.

18th and 19th centuries

The modern parachute was invented in the late 18th century by Louis-Sébastien Lenormand in

The modern parachute was invented in the late 18th century by Louis-Sébastien Lenormand in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, who made the first recorded public jump in 1783. Lenormand also sketched his device beforehand.

Two years later, in 1785, Lenormand coined the word "parachute" by hybridizing an Italian prefix ''para'', an imperative form of ''parare'' = to avert, defend, resist, guard, shield or shroud, from ''paro'' = to parry, and ''chute'', the French word for ''fall'', to describe the aeronautical device's real function.

Also in 1785, Jean-Pierre Blanchard

Jean-Pierre rançoisBlanchard (4 July 1753 – 7 March 1809) was a French inventor, best known as a pioneer of gas balloon flight, who distinguished himself in the conquest of the air in a balloon, in particular the first crossing of the Engli ...

demonstrated it as a means of safely disembarking from a hot-air balloon

A hot air balloon is a lighter-than-air aircraft consisting of a bag, called an envelope, which contains heated air. Suspended beneath is a gondola or wicker basket (in some long-distance or high-altitude balloons, a capsule), which carries p ...

. While Blanchard's first parachute demonstrations were conducted with a dog as the passenger, he later claimed to have had the opportunity to try it himself in 1793 when his hot air balloon ruptured, and he used a parachute to descend. (This event was not witnessed by others).

Subsequent development of the parachute focused on it becoming more compact. While the early parachutes were made of linen

Linen () is a textile made from the fibers of the flax plant.

Linen is very strong, absorbent, and dries faster than cotton. Because of these properties, linen is comfortable to wear in hot weather and is valued for use in garments. It also ...

stretched over a wooden frame, in the late 1790s, Blanchard began making parachutes from folded silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from th ...

, taking advantage of silk's strength and light weight

In science and engineering, the weight of an object is the force acting on the object due to gravity.

Some standard textbooks define weight as a vector quantity, the gravitational force acting on the object. Others define weight as a scalar qua ...

. In 1797, André Garnerin

André — sometimes transliterated as Andre — is the French and Portuguese language, Portuguese form of the name Andrew, and is now also used in the English-speaking world. It used in France, Quebec, Canada and other French language, French-s ...

made the first descent of a "frameless" parachute covered in silk. In 1804, Jérôme Lalande

Joseph Jérôme Lefrançois de Lalande (; 11 July 1732 – 4 April 1807) was a French astronomer, freemason and writer.

Biography

Lalande was born at Bourg-en-Bresse (now in the département of Ain) to Pierre Lefrançois and Marie‐Anne‐Ga ...

introduced a vent in the canopy to eliminate violent oscillations. In 1887, Park Van Tassel

Park Albert Van Tassel (b.1853-d.1930) was a pioneering aerial exhibitionist in the United States. Van Tassel made the first balloon flights in New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado and helped invent and introduce methods of parachute jumping from balloon ...

and Thomas Scott Baldwin

Thomas Scott Baldwin (June 30, 1854 – May 17, 1923) was a pioneer balloonist and U.S. Army major during World War I. He was the first American to descend from a balloon by parachute.

Early career

Thomas Scott Baldwin was born on June 30, 185 ...

invented a parachute in San Francisco, California, with Baldwin making the first successful parachute jump in the western United States.

Eve of World War I

In 1907 Charles Broadwick demonstrated two key advances in the parachute he used to jump from

In 1907 Charles Broadwick demonstrated two key advances in the parachute he used to jump from hot air balloon

A hot air balloon is a lighter-than-air aircraft consisting of a bag, called an envelope, which contains heated air. Suspended beneath is a gondola or wicker basket (in some long-distance or high-altitude balloons, a capsule), which carries ...

s at fair

A fair (archaic: faire or fayre) is a gathering of people for a variety of entertainment or commercial activities. Fairs are typically temporary with scheduled times lasting from an afternoon to several weeks.

Types

Variations of fairs incl ...

s: he folded his parachute into a backpack

A backpack—also called knapsack, schoolbag, rucksack, rucksac, pack, sackpack, booksack, bookbag or backsack—is, in its simplest frameless form, a fabric sack carried on one's back and secured with two straps that go over the shoulders ...

, and the parachute was pulled from the pack by a static line attached to the balloon. When Broadwick jumped from the balloon, the static line became taut, pulled the parachute from the pack, and then snapped.

In 1911 a successful test took place with a dummy at the Eiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower ( ; french: links=yes, tour Eiffel ) is a wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris, France. It is named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower.

Locally nicknamed ...

in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

. The puppet's weight was ; the parachute's weight was . The cables between the puppet and the parachute were long. On February 4, 1912, Franz Reichelt

Franz Reichelt (16 October 1878 – 4 February 1912), also known as Frantz Reichelt or François Reichelt, was an Austrian-born French tailor, inventor and parachuting pioneer, now sometimes referred to as the Flying Tailor, who is remembered fo ...

jumped to his death from the tower during initial testing of his wearable parachute.

Also in 1911, Grant Morton

Grant Morton (1857?–1920), born William H. Morton, was one of the first people to successfully attempt skydiving, and is sometimes credited with the first skydive and jump from a powered aeroplane, in 1911. Supposedly, at age 54, Morton, a vetera ...

made the first parachute jump from an airplane

An airplane or aeroplane (informally plane) is a fixed-wing aircraft that is propelled forward by thrust from a jet engine, propeller, or rocket engine. Airplanes come in a variety of sizes, shapes, and wing configurations. The broad ...

, a Wright Model B

The Wright Model B was an early pusher biplane designed by the Wright brothers in the United States in 1910. It was the first of their designs to be built in quantity. Unlike the Model A, it featured a true elevator carried at the tail ra ...

piloted by Phil Parmalee

Philip Orin Parmelee (March 8, 1887 – June 1, 1912) was an American aviation pioneer trained by the Wright brothers and credited with several early world aviation records and "firsts" in flight. He turned a keen interest in small engines into ...

, at Venice Beach, California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

. Morton's device was of the "throw-out" type where he held the parachute in his arms as he left the aircraft. In the same year (1911), Russian Gleb Kotelnikov invented the first knapsack parachute, although Hermann Lattemann

Hermann Lattemann (September 14, 1852, Gebhardshagen near Braunschweig – June 17, 1894, Krefeld) was a German balloon pilot and inventor who experimented with an early prototype of a parachute.

Together with his wife Käthe Paulus, Latteman ...

and his wife Käthe Paulus had been jumping with bagged parachutes in the last decade of the 19th century.

In 1912, on a road near

In 1912, on a road near Tsarskoye Selo

Tsarskoye Selo ( rus, Ца́рское Село́, p=ˈtsarskəɪ sʲɪˈlo, a=Ru_Tsarskoye_Selo.ogg, "Tsar's Village") was the town containing a former residence of the Russian imperial family and visiting nobility, located south from the c ...

, years before it became part of St. Petersburg, Kotelnikov successfully demonstrated the braking effects of a parachute by accelerating a Russo-Balt automobile to its top speed and then opening a parachute attached to the back seat, thus also inventing the drogue parachute

A drogue parachute is a parachute designed for deployment from a rapidly-moving object. It can be used for various purposes, such as to decrease speed, to provide control and stability, or as a pilot parachute to deploy a larger parachute. V ...

.

On 1 March 1912, U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

Captain Albert Berry made the first (attached-type) parachute jump in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

from a fixed-wing aircraft

A fixed-wing aircraft is a heavier-than-air flying machine, such as an airplane, which is capable of flight using wings that generate lift caused by the aircraft's forward airspeed and the shape of the wings. Fixed-wing aircraft are dist ...

, a Benoist pusher, while flying above Jefferson Barracks

The Jefferson Barracks Military Post is located on the Mississippi River at Lemay, Missouri, south of St. Louis. It was an important and active U.S. Army installation from 1826 through 1946. It is the oldest operating U.S. military installation ...

, St. Louis, Missouri. The jump utilized a parachute stored or housed in a cone-shaped casing under the airplane and attached to a harness on the jumper's body.

Štefan Banič

Štefan Banič (; 23 November 1870 – 2 January 1941) was a Slovak inventor who patented an early parachute design.

Born in Jánostelek ( sk, Neštich), Austria-Hungary (now part of Smolenice, Slovakia), Banič immigrated to the United Sta ...

patented an umbrella-like design in 1914, and sold (or donated) the patent to the United States military, which later modified his design, resulting in the first military parachute.Štefan Banič, Konštruktér, vynálezcaMatematický ústav, Slovenská akadémia vied, obituary. Retrieved 21 October 2010. Banič had been the first person to patent the parachute, and his design was the first to properly function in the 20th century. On June 21, 1913,

Georgia Broadwick

Broadwick ready to drop from a Glenn Martin.">Glenn_L._Martin.html" ;"title="Martin T airplane piloted by Glenn L. Martin">Glenn Martin.

Georgia Ann "Tiny" Thompson Broadwick (April 8, 1893 in Oxford, North Carolina – 1978 in California), or Ge ...

became the first woman to parachute-jump from a moving aircraft, doing so over Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

. In 1914, while doing demonstrations for the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

, Broadwick deployed her chute manually, thus becoming the first person to jump free-fall.

World War I

The first military use of the parachute was by

The first military use of the parachute was by artillery observer

An artillery observer, artillery spotter or forward observer (FO) is responsible for directing artillery and mortar fire onto a target. It may be a ''forward air controller'' (FAC) for close air support (CAS) and spotter for naval gunfire sup ...

s on tethered observation balloons in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. These were tempting targets for enemy fighter aircraft

Fighter aircraft are fixed-wing military aircraft designed primarily for air-to-air combat. In military conflict, the role of fighter aircraft is to establish air superiority of the battlespace. Domination of the airspace above a battlefield ...

, though difficult to destroy, due to their heavy anti-aircraft

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based ...

defenses. Because it was difficult to escape from them, and dangerous when on fire due to their hydrogen inflation, observers would abandon them and descend by parachute as soon as enemy aircraft were seen. The ground crew would then attempt to retrieve and deflate the balloon as quickly as possible. The main part of the parachute was in a bag suspended from the balloon with the pilot wearing only a simple waist harness attached to the main parachute. When the balloon crew jumped the main part of the parachute was pulled from the bag by the crew's waist harness, first the shroud lines, followed by the main canopy. This type of parachute was first adopted on a large scale for their observation balloon crews by the Germans, and then later by the British and French. While this type of unit worked well from balloons, it had mixed results when used on fixed-wing aircraft by the Germans, where the bag was stored in a compartment directly behind the pilot. In many instances where it did not work the shroud lines became entangled with the spinning aircraft. Although this type of parachute saved a number of famous German fighter pilots, including Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

, no parachutes were issued to the crews of Allied "heavier-than-air

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to fly by gaining support from the air. It counters the force of gravity by using either static lift or by using the dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in a few cases the downward thrust from jet engines. ...

" aircraft, since it was thought that if a pilot had a parachute he would jump from the plane when hit rather than trying to save the aircraft.

Airplane cockpits at that time also were not large enough to accommodate a pilot and a parachute, since a seat that would fit a pilot wearing a parachute would be too large for a pilot not wearing one. This is why the German type was stowed in the fuselage, rather than being of the "backpack" type. Weight was – at the very beginning – also a consideration since planes had limited load capacity. Carrying a parachute impeded performance and reduced the useful offensive and fuel load.

In the UK, Everard Calthrop, a railway engineer and breeder of Arab horses, invented and marketed through his Aerial Patents Company a "British Parachute" and the "Guardian Angel" parachute. As part of an investigation into Calthrop's design, on 13 January 1917, test pilot Clive Franklyn Collett

Captain Clive Franklyn Collett (28 August 1886 – 23 December 1917) was a World War I flying ace from New Zealand credited with 11 aerial victories. He was the first British or Commonwealth military pilot to use a parachute, in a test. While se ...

successfully jumped from a Royal Aircraft Factory BE.2

The Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2 was a British single-engine tractor two-seat biplane designed and developed at the Royal Aircraft Factory. Most of the roughly 3,500 built were constructed under contract by private companies, including establish ...

c flying over Orford Ness Experimental Station at . He repeated the experiment several days later.

Following on from Collett, balloon officer Thomas Orde-Lees

Major Thomas Hans Orde-Lees, OBE, AFC (23 May 1877 – 1 December 1958) was a member of Sir Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–1917, a pioneer in the field of parachuting, and was one of the first non-Japan ...

, known as the "Mad Major", successfully jumped from Tower Bridge in London, which led to the balloonists of the Royal Flying Corps

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colors =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, decorations ...

using parachutes, though they were issued for use in aircraft.

In 1911, Solomon Lee Van Meter, Jr.

Solomon Lee Van Meter Jr. (April 8, 1888 - November 3, 1937) was an American inventor, famous for inventing the first successful backpack Parachute.

Early life

Solomon Lee Van Meter Jr. was born as Joseph Atkins Van Meter in a cabin behind where ...

of Lexington, Kentucky, submitted for and in July 1916 received a patent for a backpack style parachute – the Aviatory Life Buoy. His self-contained device featured a revolutionary quick-release mechanism – the ripcord – that allowed a falling aviator to expand the canopy only when safely away from the disabled aircraft.

Otto Heinecke, a German airship ground crewman, designed a parachute which the German air service introduced in 1918, becoming the world's first air service to introduce a standard parachute. Schroeder company of Berlin manufactured Heinecke's design. The first successful use of this parachute was by Leutnant Helmut Steinbrecher

Leutnant Helmut Steinbrecher was the first pilot in history to successfully parachute from a stricken airplane, on 27 June 1918. He was a World War I flying ace credited with five aerial victories.

Biography

Helmut Steinbrecher was born in Dres ...

of Jagdstaffel 46, who bailed on 27 June 1918 from his stricken fighter airplane to become the first pilot in history to successfully do so. Although many pilots were saved by the Heinecke design, their efficacy was relatively poor. Out of the first 70 German airmen to bail out, around a third died, These fatalities were mostly due to the chute or ripcord becoming entangled in the airframe of their spinning aircraft or because of harness failure, a problem fixed in later versions.

The French, British, American and Italian air services later based their first parachute designs on the Heinecke parachute to varying extents.

In the UK, Sir Frank Mears

Sir Frank Charles Mears LLD (11 July 1880 – 25 January 1953) was an architect and Scotland's leading planning consultant from the 1930s to the early 1950s.

Life and work

Born in Tynemouth he moved to Edinburgh in 1897 when his father, ...

, who was serving as a Major in the Royal Flying Corps

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colors =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, decorations ...

in France (Kite Balloon section), registered a patent in July 1918 for a parachute with a quick release buckle, known as the "Mears parachute", which was in common use from then onwards.

Post-World War I

The experience with parachutes during the war highlighted the need to develop a design that could be reliably used to exit a disabled airplane. For instance, tethered parachutes did not work well when the aircraft was spinning. After the war, Major Edward L. Hoffman of the

The experience with parachutes during the war highlighted the need to develop a design that could be reliably used to exit a disabled airplane. For instance, tethered parachutes did not work well when the aircraft was spinning. After the war, Major Edward L. Hoffman of the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

led an effort to develop an improved parachute by bringing together the best elements of multiple parachute designs. Participants in the effort included Leslie Irvin and James Floyd Smith

James Floyd Smith (17 October 1884 – 18 April 1956) was an inventor, aviation pioneer, and parachute manufacturer. With borrowed money, he built, then taught himself to fly his own airplane.

He worked as a flight instructor and test pi ...

. The team eventually created the Airplane Parachute Type-A. This incorporated three key elements:

* storing the parachute in a soft pack worn on the back, as demonstrated by Charles Broadwick in 1906;

* a ripcord for manually deploying the parachute at a safe distance from the airplane, from a design by Albert Leo Stevens

Albert Leo Stevens (March 9, 1877 – May 8, 1944) was a pioneering balloonist.

Biography

He was born on March 9, in 1873 or 1877, in Cleveland, Ohio, of Czech parentage. He had brother Frank Stevens (1875–1958).

He started making b ...

; and

* a pilot chute that draws the main canopy from the pack.

In 1919, Irvin successfully tested the parachute by jumping from an airplane. The Type-A parachute was put into production and over time saved a number of lives. The effort was recognized by the awarding of the Robert J. Collier Trophy to Major Edward L. Hoffman in 1926.

Irvin became the first person to make a premeditated free-fall parachute jump from an airplane. An early brochure of the Irvin Air Chute Company credits William O'Connor as having become, on 24 August 1920, at McCook Field near Dayton, Ohio

Dayton () is the List of cities in Ohio, sixth-largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Montgomery County, Ohio, Montgomery County. A small part of the city extends into Greene County, Ohio, Greene County. The 2020 United S ...

, the first person to be saved by an Irvin parachute. Test pilot Lt. Harold R. Harris

Harold Ross Harris (December 20, 1895 – July 28, 1988) was a notable American test pilot and U.S. Army Air Force officer who held 26 flying records. He made the first flight by American pilots over the Alps from Italy to France, successfull ...

made another life-saving jump at McCook Field on 20 October 1922. Shortly after Harris' jump, two Dayton newspaper reporters suggested the creation of the Caterpillar Club

The Caterpillar Club is an informal association of people who have successfully used a parachute to bail out of a disabled aircraft. After authentication by the parachute maker, applicants receive a membership certificate and a distinctive lapel ...

for successful parachute jumps from disabled aircraft.

Beginning with Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

in 1927, several countries experimented with using parachutes to drop soldiers behind enemy lines. The regular Soviet Airborne Troops

The Soviet Airborne Forces or VDV (from ''Vozdushno- desantnye voyska SSSR'', Russian: Воздушно-десантные войска СССР, ВДВ; Air-landing Forces) was a separate troops branch of the Soviet Armed Forces. First formed be ...

were established as early as 1931 after a number of experimental military mass jumps starting from 2 August 1930. Earlier the same year, the first Soviet mass jumps led to the development of the parachuting sport in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

. By the time of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, large airborne forces

Airborne forces, airborne troops, or airborne infantry are ground combat units carried by aircraft and airdropped into battle zones, typically by parachute drop or air assault. Parachute-qualified infantry and support personnel serving in a ...

were trained and used in surprise attacks, as in the battles for Fort Eben-Emael and The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital o ...

, the first large-scale, opposed landings of paratroopers in military history, by the Germans. This was followed later in the war by airborne assaults on a larger scale, such as the Battle of Crete

The Battle of Crete (german: Luftlandeschlacht um Kreta, el, Μάχη της Κρήτης), codenamed Operation Mercury (german: Unternehmen Merkur), was a major Axis Powers, Axis Airborne forces, airborne and amphibious assault, amphibious ope ...

and Operation Market Garden

Operation Market Garden was an Allied military operation during the Second World War fought in the Netherlands from 17 to 27 September 1944. Its objective was to create a salient into German territory with a bridgehead over the River Rhine, ...

, the latter being the largest airborne military operation ever. Aircraft crew were routinely equipped with parachutes for emergencies as well.

In 1937, drag chutes were used in aviation for the first time, by Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

airplanes in the Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

that were providing support for the polar expeditions of the era, such as the first drifting ice station, North Pole-1

North Pole-1 (russian: Северный полюс-1) was the world's first Soviet manned drifting station in the Arctic Ocean, primarily used for research.

North Pole-1 was established on 21 May 1937 and officially opened on 6 June, some from ...

. The drag chute allowed airplanes to land safely on smaller ice floes.

Most parachutes were made of silk until World War II cut off supplies from Japan. After Adeline Gray

Adeline Maria Gray (born January 15, 1991) is an American freestyle wrestler who currently competes at 76 kilograms. She is a six-time world champion (2012, 2014, 2015, 2018, 2019, 2021) and a two-time Olympian (2016, 2020), with the silver ...

made the first jump using a nylon parachute in June 1942, the industry switched to nylon.

Types

Today's modern parachutes are classified into two categories – ascending and descending canopies. All ascending canopies refer toparaglider

Paragliding is the recreational and competitive adventure sport of flying paragliders: lightweight, free-flying, foot-launched glider aircraft with no rigid primary structure. The pilot sits in a harness or lies supine in a cocoon-like ...

s, built specifically to ascend and stay aloft as long as possible. Other parachutes, including ram-air non-elliptical, are classified as descending canopies by manufacturers.

Some modern parachutes are classified as semi-rigid wings, which are maneuverable and can make a controlled descent to collapse on impact with the ground.

Round

Round parachutes are purely a drag device (that is, unlike the ram-air types, they provide no

Round parachutes are purely a drag device (that is, unlike the ram-air types, they provide no lift

Lift or LIFT may refer to:

Physical devices

* Elevator, or lift, a device used for raising and lowering people or goods

** Paternoster lift, a type of lift using a continuous chain of cars which do not stop

** Patient lift, or Hoyer lift, mobil ...

) and are used in military, emergency and cargo applications (e.g. airdrop

An airdrop is a type of airlift in which items including weapons, equipment, humanitarian aid or leaflets are delivered by military or civilian aircraft without their landing. Developed during World War II to resupply otherwise inaccessible tr ...

s). Most have large dome-shaped canopies made from a single layer of triangular cloth gores. Some skydivers call them "jellyfish 'chutes" because of the resemblance to the marine organisms. Modern sports parachutists rarely use this type.

The first round parachutes were simple, flat circulars. These early parachutes suffered from instability caused by oscillations. A hole in the apex helped to vent some air and reduce the oscillations. Many military applications adopted conical, ''i.e.'', cone-shaped, or parabolic (a flat circular canopy with an extended skirt) shapes, such as the United States Army T-10 static-line parachute. A round parachute with no holes in it is more prone to oscillate and is not considered to be steerable. Some parachutes have inverted dome-shaped canopies. These are primarily used for dropping non-human payloads due to their faster rate of descent.

Forward speed (5–13 km/h) and steering can be achieved by cuts in various sections (gores) across the back, or by cutting four lines in the back thereby modifying the canopy shape to allow air to escape from the back of the canopy, providing limited forward speed. Other modifications sometimes used are cuts in various sections (gores) to cause some of the skirt to bow out. Turning is accomplished by forming the edges of the modifications, giving the parachute more speed from one side of the modification than the other. This gives the jumpers the ability to steer the parachute (such as the United States Army MC series parachutes), enabling them to avoid obstacles and to turn into the wind to minimize horizontal speed at landing

Landing is the last part of a flight, where a flying animal, aircraft, or spacecraft returns to the ground. When the flying object returns to water, the process is called alighting, although it is commonly called "landing", "touchdown" or ...

.

Cruciform

The unique design characteristics of cruciform parachutes decrease oscillation (its user swinging back and forth) and violent turns during descent. This technology will be used by the United States Army as it replaces its older T-10 parachutes withT-11 parachute

The Non-Maneuverable Canopy (T-11) Personnel Parachute System is the newest personnel parachute system to be adopted by the United States armed forces and the Canadian Army. The T-11 replaces the T-10, introduced in 1955. The T-11 includes a co ...

s under a program called Advanced Tactical Parachute System (ATPS). The ATPS canopy is a highly modified version of a cross/ cruciform platform and is square in appearance. The ATPS system will reduce the rate of descent by 30 percent from to . The T-11 is designed to have an average rate of descent 14% slower than the T-10D, thus resulting in lower landing injury rates for jumpers. The decline in the rate of descent will reduce the impact energy by almost 25% to lessen the potential for injury.

Pull-down apex

A variation on the round parachute is the pull-down apex parachute, invented by a Frenchman named Pierre-Marcel Lemoigne. The first widely used canopy of this type was called the ''Para-Commander'' (made by the Pioneer Parachute Co.), although there are many other canopies with a pull-down apex produced in the years thereafter - these had minor differences in attempts to make a higher performance rig, such as different venting configurations. They are all considered 'round' parachutes, but with suspension lines to the canopy apex that apply load there and pull the apex closer to the load, distorting the round shape into a somewhat flattened or lenticular shape when viewed from the side. And while called ''rounds'', they generally have an elliptical shape when viewed from above or below, with the sides bulging out more than the for'd-and-aft dimension, the chord (see the lower photo to the right and you likely can ascertain the difference).

Due to their lenticular shape and appropriate venting, they have a considerably faster forward speed than, say, a modified military canopy. And due to controllable rear-facing vents in the canopy's sides, they also have much snappier turning capabilities, though they are decidedly low-performance compared to today's ram-air rigs. From about the mid-1960s to the late-1970s, this was the most popular parachute design type for sport parachuting (prior to this period, modified military 'rounds' were generally used and after, ram-air 'squares' became common). Note that the use of the word ''elliptical'' for these 'round' parachutes is somewhat dated and may cause slight confusion, since some 'squares' (i.e. ram-airs) are elliptical nowadays, too.

A variation on the round parachute is the pull-down apex parachute, invented by a Frenchman named Pierre-Marcel Lemoigne. The first widely used canopy of this type was called the ''Para-Commander'' (made by the Pioneer Parachute Co.), although there are many other canopies with a pull-down apex produced in the years thereafter - these had minor differences in attempts to make a higher performance rig, such as different venting configurations. They are all considered 'round' parachutes, but with suspension lines to the canopy apex that apply load there and pull the apex closer to the load, distorting the round shape into a somewhat flattened or lenticular shape when viewed from the side. And while called ''rounds'', they generally have an elliptical shape when viewed from above or below, with the sides bulging out more than the for'd-and-aft dimension, the chord (see the lower photo to the right and you likely can ascertain the difference).

Due to their lenticular shape and appropriate venting, they have a considerably faster forward speed than, say, a modified military canopy. And due to controllable rear-facing vents in the canopy's sides, they also have much snappier turning capabilities, though they are decidedly low-performance compared to today's ram-air rigs. From about the mid-1960s to the late-1970s, this was the most popular parachute design type for sport parachuting (prior to this period, modified military 'rounds' were generally used and after, ram-air 'squares' became common). Note that the use of the word ''elliptical'' for these 'round' parachutes is somewhat dated and may cause slight confusion, since some 'squares' (i.e. ram-airs) are elliptical nowadays, too.

Annular

Some designs with a pull-down apex have the fabric removed from the apex to open a hole through which air can exit (most, if not all, round canopies have at least a small hole to allow easier tie-down for packing - these aren't considered annular), giving the canopy an annular geometry. This hole can be very pronounced in some designs, taking up more 'space' than the parachute. They also have decreased horizontal drag due to their flatter shape and, when combined with rear-facing vents, can have considerable forward speed. Truly annular designs - with a hole large enough that the canopy can be classified as ''ring-shaped'' - are uncommon.Rogallo wing

Sport parachuting has experimented with the Rogallo wing, among other shapes and forms. These were usually an attempt to increase the forward speed and reduce the landing speed offered by the other options at the time. The ram-air parachute's development and the subsequent introduction of the sail slider to slow deployment reduced the level of experimentation in the sport parachuting community. The parachutes are also hard to build.Ribbon and Ring

Ribbon and ring parachutes have similarities to annular designs. They are frequently designed to deploy at

Ribbon and ring parachutes have similarities to annular designs. They are frequently designed to deploy at supersonic

Supersonic speed is the speed of an object that exceeds the speed of sound ( Mach 1). For objects traveling in dry air of a temperature of 20 °C (68 °F) at sea level, this speed is approximately . Speeds greater than five times ...

speeds. A conventional parachute would instantly burst upon opening and be shredded at such speeds. Ribbon parachutes have a ring-shaped canopy, often with a large hole in the centre to release the pressure. Sometimes the ring is broken into ribbons connected by ropes to leak air even more. These large leaks lower the stress on the parachute so it does not burst or shred when it opens. Ribbon parachutes made of Kevlar

Kevlar (para-aramid) is a strong, heat-resistant synthetic fiber, related to other aramids such as Nomex and Technora. Developed by Stephanie Kwolek at DuPont in 1965, the high-strength material was first used commercially in the early 1970s a ...

are used on nuclear bombs, such as the B61 and B83.

Ram-air

The principle of the Ram-Air Multicell Airfoil was conceived in 1963 by Canadian Domina "Dom" C. Jalbert, but serious problems had to be solved before a ram-air canopy could be marketed to the sport parachuting community. Ram-air parafoils are steerable (as are most canopies used for sport parachuting), and have two layers of fabric—top and bottom—connected by airfoil-shaped fabric ribs to form "cells". The cells fill with higher-pressure air from vents that face forward on the leading edge of the airfoil. The fabric is shaped and the parachute lines trimmed under load such that the ballooning fabric inflates into an airfoil shape. This airfoil is sometimes maintained by use of fabric one-way valves called '' airlocks''. "The first jump of this canopy (a Jalbert Parafoil) was made by International Skydiving Hall of Fame member Paul "Pop" Poppenhager."Varieties

Personal ram-air parachutes are loosely divided into two varieties – rectangular or tapered – commonly called "squares" or "ellipticals", respectively. Medium-performance canopies (reserve-, BASE-, canopy formation-, and accuracy-type) are usually rectangular. High-performance, ram-air parachutes have a slightly tapered shape to their leading and/or trailing edges when viewed in plan form, and are known as ellipticals. Sometimes all the taper is on the leading edge (front), and sometimes in the trailing edge (tail).

Ellipticals are usually used only by sport parachutists. They often have smaller, more numerous fabric cells and are shallower in profile. Their canopies can be anywhere from slightly elliptical to highly elliptical, indicating the amount of taper in the canopy design, which is often an indicator of the responsiveness of the canopy to control input for a given wing loading, and of the level of experience required to pilot the canopy safely.

The rectangular parachute designs tend to look like square, inflatable air mattresses with open front ends. They are generally safer to operate because they are less prone to dive rapidly with relatively small control inputs, they are usually flown with lower wing loadings per square foot of area, and they glide more slowly. They typically have a lower

Personal ram-air parachutes are loosely divided into two varieties – rectangular or tapered – commonly called "squares" or "ellipticals", respectively. Medium-performance canopies (reserve-, BASE-, canopy formation-, and accuracy-type) are usually rectangular. High-performance, ram-air parachutes have a slightly tapered shape to their leading and/or trailing edges when viewed in plan form, and are known as ellipticals. Sometimes all the taper is on the leading edge (front), and sometimes in the trailing edge (tail).

Ellipticals are usually used only by sport parachutists. They often have smaller, more numerous fabric cells and are shallower in profile. Their canopies can be anywhere from slightly elliptical to highly elliptical, indicating the amount of taper in the canopy design, which is often an indicator of the responsiveness of the canopy to control input for a given wing loading, and of the level of experience required to pilot the canopy safely.

The rectangular parachute designs tend to look like square, inflatable air mattresses with open front ends. They are generally safer to operate because they are less prone to dive rapidly with relatively small control inputs, they are usually flown with lower wing loadings per square foot of area, and they glide more slowly. They typically have a lower glide ratio

In aerodynamics, the lift-to-drag ratio (or L/D ratio) is the lift generated by an aerodynamic body such as an aerofoil or aircraft, divided by the aerodynamic drag caused by moving through air. It describes the aerodynamic efficiency under giv ...

.

Wing loading of parachutes is measured similarly to that of aircraft, comparing exit weight to area of parachute fabric. Typical wing loading for students, accuracy competitors, and BASE jumpers is less than 5 kg per square meter – often 0.3 kilograms per square meter or less. Most student skydivers fly with wing loading below 5 kg per square meter. Most sport jumpers fly with wing loading between 5 and 7 kg per square meter, but many interested in performance landings exceed this wing loading. Professional Canopy pilots compete with wing loading of 10 to over 15 kilograms per square meter. While ram-air parachutes with wing loading higher than 20 kilograms per square meter have been landed, this is strictly the realm of professional test jumpers.

Smaller parachutes tend to fly faster for the same load, and ellipticals respond faster to control input. Therefore, small, elliptical designs are often chosen by experienced canopy pilots for the thrilling flying they provide. Flying a fast elliptical requires much more skill and experience. Fast ellipticals are also considerably more dangerous to land. With high-performance elliptical canopies, nuisance malfunctions can be much more serious than with a square design, and may quickly escalate into emergencies. Flying highly loaded, elliptical canopies is a major contributing factor in many skydiving accidents, although advanced training programs are helping to reduce this danger.

High-speed, cross-braced parachutes, such as the Velocity, VX, XAOS, and Sensei, have given birth to a new branch of sport parachuting called "swooping." A race course is set up in the landing area for expert pilots to measure the distance they are able to fly past the tall entry gate. Current world records exceed .

Aspect ratio is another way to measure ram-air parachutes. Aspect ratios of parachutes are measured the same way as aircraft wings, by comparing span with chord. Low aspect ratio parachutes, ''i.e.'', span 1.8 times the chord, are now limited to precision landing competitions. Popular precision landing parachutes include Jalbert (now NAA) Para-Foils and John Eiff's series of Challenger Classics. While low aspect ratio parachutes tend to be extremely stable, with gentle stall characteristics, they suffer from steep glide ratios and a small tolerance, or "sweet spot", for timing the landing flare.

Because of their predictable opening characteristics, parachutes with a medium aspect ratio around 2.1 are widely used for reserves, BASE, and canopy formation competition. Most medium aspect ratio parachutes have seven cells.

High aspect ratio parachutes have the flattest glide and the largest tolerance for timing the landing flare, but the least predictable openings. An aspect ratio of 2.7 is about the upper limit for parachutes. High aspect ratio canopies typically have nine or more cells. All reserve ram-air parachutes are of the square variety, because of the greater reliability, and the less-demanding handling characteristics.

Paragliders

Paragliders - virtually all of which use ram-air canopies - are more akin to today's sport parachutes than, say, parachutes of the mid-1970s and earlier. Technically, they are ''ascending parachutes'', though that term is not used in the paragliding community, and they have the same basic airfoil design of today's 'square' or 'elliptical' sports

Paragliders - virtually all of which use ram-air canopies - are more akin to today's sport parachutes than, say, parachutes of the mid-1970s and earlier. Technically, they are ''ascending parachutes'', though that term is not used in the paragliding community, and they have the same basic airfoil design of today's 'square' or 'elliptical' sports parachuting

Parachuting, including also skydiving, is a method of transiting from a high point in the Atmosphere of Earth, atmosphere to the surface of Earth with the aid of gravity, involving the control of speed during the descent using a parachut ...

canopy, but generally have more sectioned cells, higher aspect ratio and a lower profile. Cell count varies widely, typically from the high 20s to the 70s, while aspect ratio can be 8 or more, though aspect ratio (projected) for such a canopy might be down at 6 or so - both outrageously higher than a representative skydiver's parachute. The wing span is typically so great that it's far closer to a very elongated rectangle or ellipse than a ''square'' and that term is rarely used by paraglider pilots. Similarly, span might be ~15 m with span (projected) at 12 m. Canopies are still attached to the harness by suspension lines and (four or six) risers, but they use lockable carabiner

A carabiner or karabiner () is a specialized type of shackle, a metal loop with a spring-loaded gate used to quickly and reversibly connect components, most notably in safety-critical systems. The word is a shortened form of ''Karabinerhaken'' ...

s as the final connection to the harness. Modern high-performance paragliders often have the cell openings closer to the bottom of the leading edge and the end cells might appear to be closed, both for aerodynamic streamlining (these apparently closed end cells are vented and inflated from the adjacent cells, which have venting in the cell walls).

The main difference is in paragliders' usage, typically longer flights that can last all day and hundreds of kilometres in some cases. The harness is also quite different from a parachuting harness and can vary dramatically from ones for the beginner (which might be just a bench seat with nylon material and webbing to ensure the pilot is secure, no matter the position), to seatboardless ones for high altitude and cross-country flights (these are usually full-body cocoon- or hammock-like devices to include the outstretched legs - called ''speedbags'', ''aerocones'', etc. - to ensure aerodynamic efficiency and warmth). In many designs, there will be protection for the back and shoulder areas built-in, and support for a reserve canopy, water container, etc. Some even have windshields.

Because paragliders are made for foot- or ski-launch, they aren't suitable for terminal velocity openings and there is no slider to slow down an opening (paraglider pilots typically start with an ''open'' but uninflated canopy). To launch a paraglider, one typically spreads out the canopy on the ground to closely approximate an open canopy with the suspension lines having little slack and less tangle - see more in Paragliding

Paragliding is the recreational and competitive adventure sport of flying paragliders: lightweight, free-flying, foot-launched glider aircraft with no rigid primary structure. The pilot sits in a harness or lies supine in a cocoon-like 'p ...

. Depending on the wind, the pilot has three basic options: 1) a running forward launch (typically in no wind or slight wind), 2) a standing launch (in ''ideal'' winds) and 3) a reverse launch (in higher winds). In ideal winds, the pilot pulls on the top risers to have the wind inflate the cells and simply eases the brakes down, much like an aircraft's flaps, and takes off. Or if there is no wind, the pilot runs or skis to make it inflate, typically at the edge of a cliff or hill. Once the canopy is above one's head, it's a gentle pull down on both toggles in ideal winds, a tow (say, behind a vehicle) on flat ground, a continued run down the hill, etc. Ground handling in a variety of winds is important and there are even canopies made strictly for that practice, to save on wear and tear of more expensive canopies designed for say, XC, competition or just recreational flying.

General characteristics

Main parachutes used by skydivers today are designed to open softly. Overly rapid deployment was an early problem with ram-air designs. The primary innovation that slows the deployment of a ram-air canopy is the slider; a small rectangular piece of fabric with agrommet

Curtain grommets, used among others in shower curtains.

A grommet is a ring or edge strip inserted into a hole through thin material, typically a sheet of textile fabric, sheet metal or composite of carbon fiber, wood or honeycomb. Grommets ar ...

near each corner. Four collections of lines go through the grommets to the risers (risers are strips of webbing joining the harness and the rigging lines of a parachute). During deployment, the slider slides down from the canopy to just above the risers. The slider is slowed by air resistance as it descends and reduces the rate at which the lines can spread. This reduces the speed at which the canopy can open and inflate.

At the same time, the overall design of a parachute still has a significant influence on the deployment speed. Modern sport parachutes' deployment speeds vary considerably. Most modern parachutes open comfortably, but individual skydivers may prefer harsher deployment.

The deployment process is inherently chaotic. Rapid deployments can still occur even with well-behaved canopies. On rare occasions, deployment can even be so rapid that the jumper suffers bruising, injury, or death. Reducing the amount of fabric decreases the air resistance. This can be done by making the slider smaller, inserting a mesh panel, or cutting a hole in the slider.

Deployment