Naval gunnery on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Naval artillery is

Naval artillery is

The idea of ship-borne artillery dates back to the classical era.

The idea of ship-borne artillery dates back to the classical era.

The 16th century was an era of transition in naval warfare. Since ancient times, war at sea had been fought much like that on land: with

The 16th century was an era of transition in naval warfare. Since ancient times, war at sea had been fought much like that on land: with

During rebuilding in 1536, ''Mary Rose'' had a second tier of carriage-mounted long guns fitted. Records show how the configuration of guns changed as gun-making technology evolved and new classifications were invented. In 1514, the armament consisted mostly of anti-personnel guns like the larger breech-loading iron ''murderers'' and the small ''serpentines'', ''demi-slings'' and stone guns. Only a handful of guns in the first inventory were powerful enough to hole enemy ships, and most would have been supported by the ship's structure rather than resting on carriages. The inventories of both the ''Mary Rose'' and the Tower had changed radically by 1540. There were now the new cast bronze ''cannons'', ''demi-cannons'', ''culverins'' and ''sakers'' and the wrought iron ''port pieces'' (a name that indicated they fired through ports), all of which required carriages, had longer range and were capable of doing serious damage to other ships.

Various types of ammunition could be used for different purposes: plain spherical shot of stone or iron smashed hulls, spiked bar shot and shot linked with chains would tear sails or damage rigging, and

During rebuilding in 1536, ''Mary Rose'' had a second tier of carriage-mounted long guns fitted. Records show how the configuration of guns changed as gun-making technology evolved and new classifications were invented. In 1514, the armament consisted mostly of anti-personnel guns like the larger breech-loading iron ''murderers'' and the small ''serpentines'', ''demi-slings'' and stone guns. Only a handful of guns in the first inventory were powerful enough to hole enemy ships, and most would have been supported by the ship's structure rather than resting on carriages. The inventories of both the ''Mary Rose'' and the Tower had changed radically by 1540. There were now the new cast bronze ''cannons'', ''demi-cannons'', ''culverins'' and ''sakers'' and the wrought iron ''port pieces'' (a name that indicated they fired through ports), all of which required carriages, had longer range and were capable of doing serious damage to other ships.

Various types of ammunition could be used for different purposes: plain spherical shot of stone or iron smashed hulls, spiked bar shot and shot linked with chains would tear sails or damage rigging, and

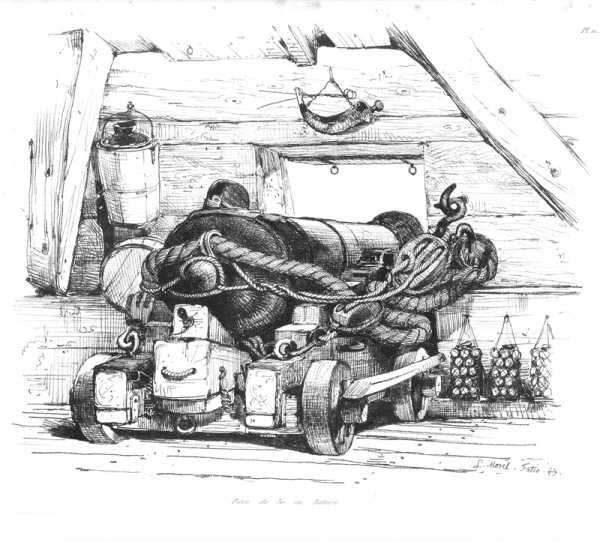

Firing a naval cannon required a great amount of labour and manpower. The propellant was gunpowder, whose bulk had to be kept in a special storage area below deck for safety. ''Powder boys'', typically 10–14 years old, were enlisted to run powder from the armoury up to the gun decks of a vessel as required.

A typical firing procedure follows. A wet swab was used to mop out the interior of the barrel, extinguishing any embers from a previous firing which might set off the next charge of gunpowder prematurely.

Firing a naval cannon required a great amount of labour and manpower. The propellant was gunpowder, whose bulk had to be kept in a special storage area below deck for safety. ''Powder boys'', typically 10–14 years old, were enlisted to run powder from the armoury up to the gun decks of a vessel as required.

A typical firing procedure follows. A wet swab was used to mop out the interior of the barrel, extinguishing any embers from a previous firing which might set off the next charge of gunpowder prematurely.  The earlier method of firing a cannon was to apply a

The earlier method of firing a cannon was to apply a

The muzzle-loading design and weight of the iron placed design constraints on the length and size of naval guns. Muzzle loading required the cannon muzzle to be positioned within the hull of the ship for loading. The hull is only so wide, with guns on both sides, and hatchways in the centre of the deck also limit the room available. Weight is always a great concern in ship design as it affects speed, stability, and buoyancy. The desire for longer guns for greater range and accuracy, and greater weight of shot for more destructive power, led to some interesting gun designs.

One unique naval gun was the long nine. It was a proportionately longer-barrelled 9-pounder. Its typical mounting as a bow or stern chaser, where it was not perpendicular to the keel, allowed room to operate this longer weapon. In a chase situation, the gun's greater range came into play. However, the desire to reduce weight in the ends of the ship and the relative fragility of the bow and stern portions of the hull limited this role to a 9-pounder, rather than one which used a 12 or 24 pound shot.

In the reign of

The muzzle-loading design and weight of the iron placed design constraints on the length and size of naval guns. Muzzle loading required the cannon muzzle to be positioned within the hull of the ship for loading. The hull is only so wide, with guns on both sides, and hatchways in the centre of the deck also limit the room available. Weight is always a great concern in ship design as it affects speed, stability, and buoyancy. The desire for longer guns for greater range and accuracy, and greater weight of shot for more destructive power, led to some interesting gun designs.

One unique naval gun was the long nine. It was a proportionately longer-barrelled 9-pounder. Its typical mounting as a bow or stern chaser, where it was not perpendicular to the keel, allowed room to operate this longer weapon. In a chase situation, the gun's greater range came into play. However, the desire to reduce weight in the ends of the ship and the relative fragility of the bow and stern portions of the hull limited this role to a 9-pounder, rather than one which used a 12 or 24 pound shot.

In the reign of

The wreck of an English

The

The

New Principles in Gunnery

' (1742), which contains a description of his

Marshall's Practical Marine Gunnery

' in 1822. Marshall was a naval artillery specialist. The book was the first scientific-technical book on naval artillery published in the United States for the U.S. Navy. He discussed cannons and fireworks. The book discusses the dimensions and apparatus necessary for the equipment of naval artillery. It features tables and charts. The book goes into further details regarding the distance of a shot on a ship based on the sound of the gun, which was found to fly at a rate of 1142 feet in one second. It was the standard of the time. According to Marshall's equation after seeing the flash of a cannon and hearing the blast the gunner would count the seconds until impact. This way a trained ear would know the distance a cannonball traveled based on ear training. The book example outlines a 9-second scenario where the distance the cannon was fired from the gunner was approximately 10,278 feet or 3,426 yards.

The

The

Explosive shells had long been in use in ground warfare (in

Explosive shells had long been in use in ground warfare (in

William Armstrong was awarded a contract by the British government in the 1850s to design a revolutionary new piece of artillery—the

William Armstrong was awarded a contract by the British government in the 1850s to design a revolutionary new piece of artillery—the  What made the gun really revolutionary lay in the technique of the construction of the gun barrel that allowed it to withstand much more powerful explosive forces. The " built-up" method involved assembling the barrel with

What made the gun really revolutionary lay in the technique of the construction of the gun barrel that allowed it to withstand much more powerful explosive forces. The " built-up" method involved assembling the barrel with

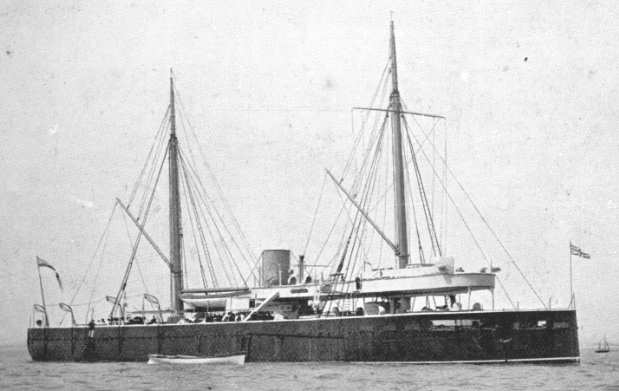

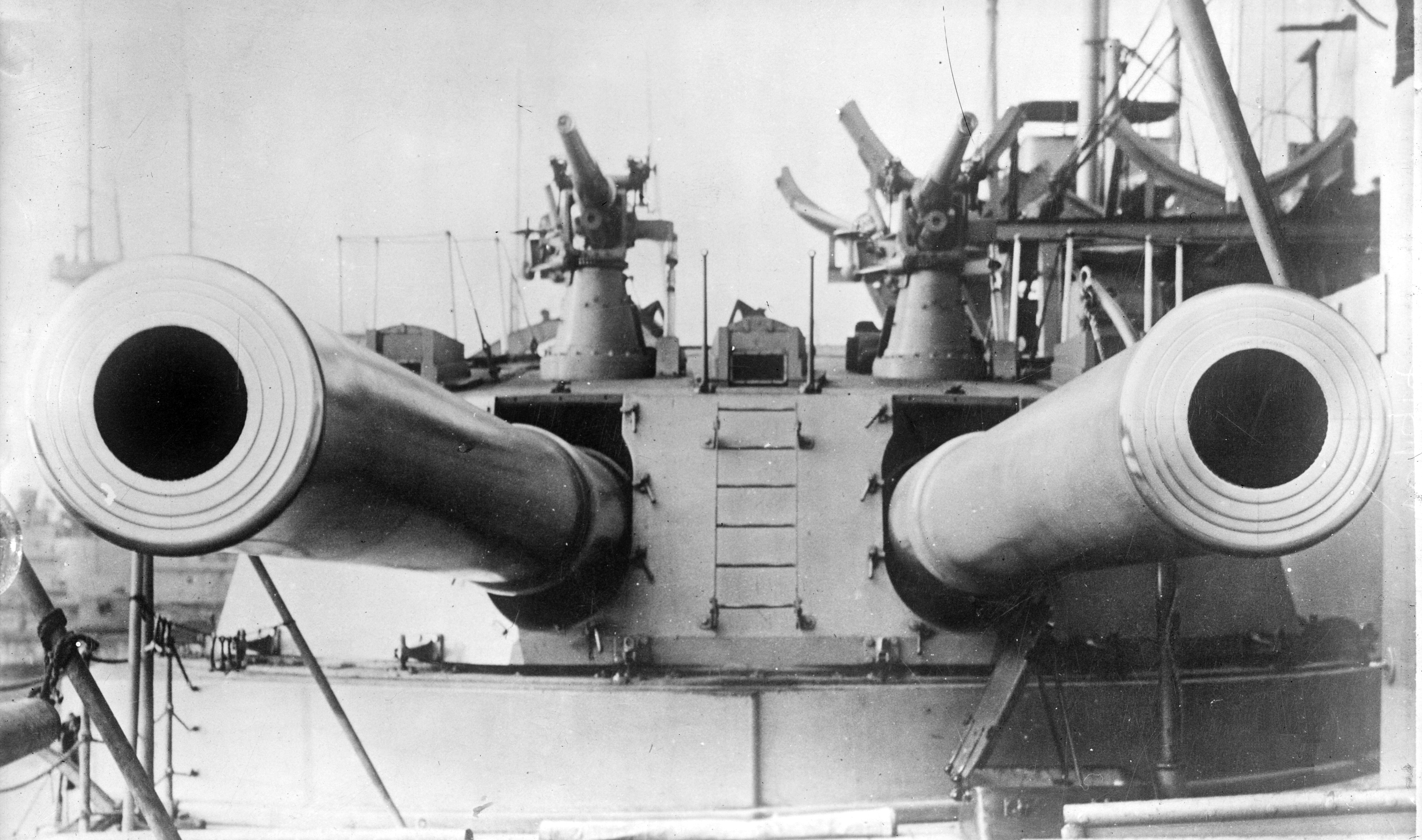

Before the development of large-calibre, long-range guns in the mid-19th century, the classic

Before the development of large-calibre, long-range guns in the mid-19th century, the classic  The gun turret was independently invented by the Swedish inventor

The gun turret was independently invented by the Swedish inventor  The turret was intended to mount a pair of

The turret was intended to mount a pair of

The late 1850s saw the development of the

The late 1850s saw the development of the

Underwater hull damage possible with

Underwater hull damage possible with

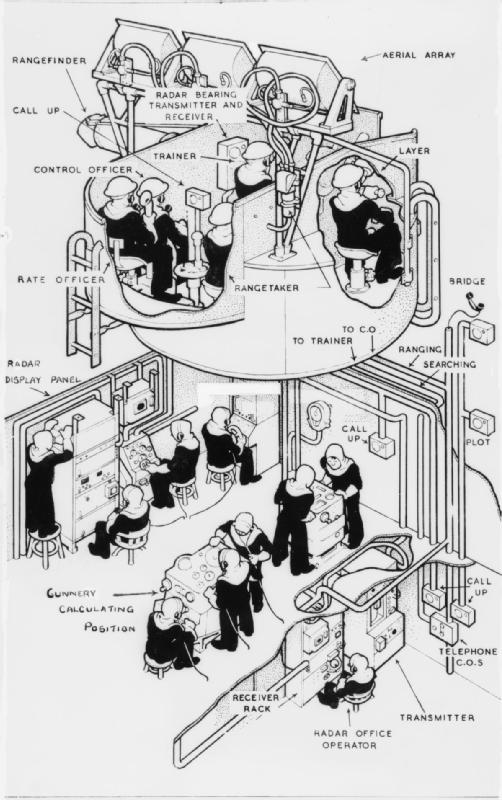

When gunnery ranges increased dramatically in the late 19th century, it was no longer a simple matter of calculating the proper aim point, given the flight times of the shells. Increasingly sophisticated

When gunnery ranges increased dramatically in the late 19th century, it was no longer a simple matter of calculating the proper aim point, given the flight times of the shells. Increasingly sophisticated

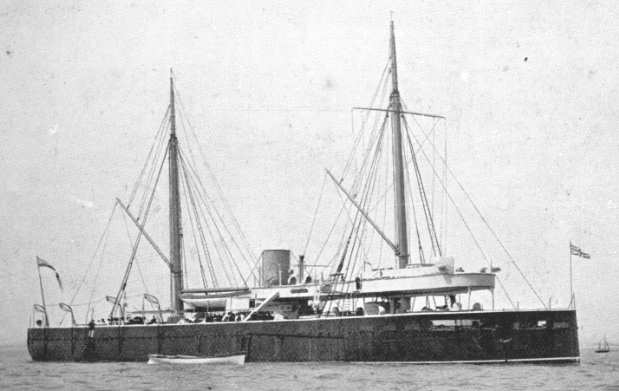

Significant gunnery developments occurred in the late 1890s and the early 1900s, culminating with the launch of the revolutionary in 1906. Sir

Significant gunnery developments occurred in the late 1890s and the early 1900s, culminating with the launch of the revolutionary in 1906. Sir  As battle ranges were pushed out to an unprecedented , the distance was great enough to force gunners to wait for the shells to arrive before applying corrections for the next

As battle ranges were pushed out to an unprecedented , the distance was great enough to force gunners to wait for the shells to arrive before applying corrections for the next  Within five years of the commissioning of ''Dreadnought'', a new generation of more powerful "super-dreadnoughts" was being built. The arrival of the super-dreadnought is commonly believed to have started with the British . What made them 'super' was the unprecedented 2,000-ton jump in displacement, the introduction of the heavier 13.5-inch (343 mm) gun, and the placement of all the main armament on the centerline. In the four years between ''Dreadnought'' and ''Orion'', displacement had increased by 25%, and weight of broadside had doubled.

In comparison to the rapid advancement of the preceding half-century, naval artillery changed comparatively little through

Within five years of the commissioning of ''Dreadnought'', a new generation of more powerful "super-dreadnoughts" was being built. The arrival of the super-dreadnought is commonly believed to have started with the British . What made them 'super' was the unprecedented 2,000-ton jump in displacement, the introduction of the heavier 13.5-inch (343 mm) gun, and the placement of all the main armament on the centerline. In the four years between ''Dreadnought'' and ''Orion'', displacement had increased by 25%, and weight of broadside had doubled.

In comparison to the rapid advancement of the preceding half-century, naval artillery changed comparatively little through

Although naval artillery had been designed to perform within the classical broadside tactics of the age of sail, World War I demonstrated the need for naval artillery mounts capable of greater elevation for defending against aircraft. High-velocity naval artillery intended to puncture side armor at close range was theoretically capable of hitting targets miles away with the aid of fire control directors; but the maximum elevation of guns mounted within restrictive armored

Although naval artillery had been designed to perform within the classical broadside tactics of the age of sail, World War I demonstrated the need for naval artillery mounts capable of greater elevation for defending against aircraft. High-velocity naval artillery intended to puncture side armor at close range was theoretically capable of hitting targets miles away with the aid of fire control directors; but the maximum elevation of guns mounted within restrictive armored

The Royal Navy continually advanced their technology and techniques necessary to conduct effective bombardments in the face of the German defenders—firstly refining

The Royal Navy continually advanced their technology and techniques necessary to conduct effective bombardments in the face of the German defenders—firstly refining

New Mexico class battleship bombarding Okinawa.jpg, The

1943 article on the history of naval cannons

''

Naval artillery is

Naval artillery is artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during si ...

mounted on a warship

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is built and primarily intended for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the armed forces of a state. As well as being armed, warships are designed to withstand damage and are usually faster ...

, originally used only for naval warfare

Naval warfare is combat in and on the sea, the ocean, or any other battlespace involving a major body of water such as a large lake or wide river. Mankind has fought battles on the sea for more than 3,000 years. Even in the interior of large la ...

and then subsequently used for shore bombardment

Naval gunfire support (NGFS) (also known as shore bombardment) is the use of naval artillery to provide fire support for amphibious assault and other troops operating within their range. NGFS is one of a number of disciplines encompassed by t ...

and anti-aircraft

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based ...

roles. The term generally refers to tube-launched projectile-firing weapons and excludes self-propelled projectiles such as torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, ...

es, rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entir ...

s, and missile

In military terminology, a missile is a guided airborne ranged weapon capable of self-propelled flight usually by a jet engine or rocket motor. Missiles are thus also called guided missiles or guided rockets (when a previously unguided rocket ...

s and those simply dropped overboard such as depth charge

A depth charge is an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) weapon. It is intended to destroy a submarine by being dropped into the water nearby and detonating, subjecting the target to a powerful and destructive hydraulic shock. Most depth charges use h ...

s and naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive device placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Unlike depth charges, mines are deposited and left to wait until they are triggered by the approach of, or contact with, an ...

s.

Origins

The idea of ship-borne artillery dates back to the classical era.

The idea of ship-borne artillery dates back to the classical era. Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

indicates the use of ship-borne catapults against Britons ashore in his ''Commentarii de Bello Gallico

''Commentarii de Bello Gallico'' (; en, Commentaries on the Gallic War, italic=yes), also ''Bellum Gallicum'' ( en, Gallic War, italic=yes), is Julius Caesar's firsthand account of the Gallic Wars, written as a third-person narrative. In it C ...

''. The dromon

A dromon (from Greek δρόμων, ''dromōn'', "runner") was a type of galley and the most important warship of the Byzantine navy from the 5th to 12th centuries AD, when they were succeeded by Italian-style galleys. It was developed from the an ...

s of the Byzantine Empire carried catapults and fire-throwers.

From the late Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

onwards, warships began to carry cannons

A cannon is a large-caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder dur ...

of various calibres. The Mongol invasion of Java

The Yuan dynasty under Kublai Khan attempted in 1292 to invade Java, an island in modern Indonesia, with 20,000 to 30,000 soldiers. This was intended as a punitive expedition against Kertanegara of Singhasari, who had refused to pay tribute ...

introduced cannons to be used in naval warfare (e.g. Cetbang

Cetbang (also known as bedil, warastra, or meriam coak) were cannons produced and used by the Majapahit Empire (1293–1527) and other kingdoms in the Indonesian archipelago. There are 2 main types of cetbang: the eastern-style cetbang which lo ...

by the Majapahit

Majapahit ( jv, ꦩꦗꦥꦲꦶꦠ꧀; ), also known as Wilwatikta ( jv, ꦮꦶꦭ꧀ꦮꦠꦶꦏ꧀ꦠ; ), was a Javanese Hindu-Buddhist thalassocratic empire in Southeast Asia that was based on the island of Java (in modern-day Indonesia ...

). The Battle of Arnemuiden

The Battle of Arnemuiden was a naval battle fought on 23 September 1338 at the start of the Hundred Years' War between England and France. It was the first naval battle of the Hundred Years' War and the first recorded European naval battle usi ...

, fought between England and France in 1338 at the start of the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a series of armed conflicts between the kingdoms of England and France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from disputed claims to the French throne between the English House of Plantagen ...

, was the first recorded European naval battle using artillery. The English ship ''Christopher'' was armed with three cannon and one hand gun. In Asia naval artillery are recorded from the Battle of Lake Poyang

The Battle of Lake Poyang () was a naval conflict which took place (30 August – 4 October 1363) between the rebel forces of Zhu Yuanzhang and Chen Youliang during the Red Turban Rebellion which led to the fall of the Yuan dynasty. Chen Youlia ...

in 1363 and in considerable quantities at the Battle of Jinpo

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and for ...

in 1380 with cannon made by Choe Museon

Choe Mu-Seon (1325–1395) was a medieval Korean scientist, inventor, and military commander during the late Goryeo Dynasty and early Joseon Dynasty. He is best known for enabling Korea to domestically produce gunpowder by obtaining a recip ...

. 80 Koryo warships successfully repelled 500 Japanese pirates referred to as Wokou

''Wokou'' (; Japanese: ''Wakō''; Korean: 왜구 ''Waegu''), which literally translates to "Japanese pirates" or "dwarf pirates", were pirates who raided the coastlines of China and Korea from the 13th century to the 16th century.

using long range cannon fire.

By the 15th century most Mediterranean powers were utilising heavy cannon mounted on the bow or stern of a vessel and designed to bombard fortresses on shore. By mid-century some vessels also carried smaller broadside cannon for bombarding other vessels immediately prior to an attempted boarding. These small guns were anti-personnel weapons and were fired at point blank range to accompany engagement with muskets or bows.

From the 1470s both the Portuguese and Venetian navies were experimenting with cannon as anti-ship weapons. King John II of Portugal

John II ( pt, João II; ; 3 March 1455 – 25 October 1495), called the Perfect Prince ( pt, o Príncipe Perfeito, link=no), was King of Portugal from 1481 until his death in 1495, and also for a brief time in 1477. He is known for re-establishi ...

, while still a prince in 1474, is credited with pioneering the introduction of a reinforced deck on the old Henry-era caravel

The caravel (Portuguese: , ) is a small maneuverable sailing ship used in the 15th century by the Portuguese to explore along the West African coast and into the Atlantic Ocean. The lateen sails gave it speed and the capacity for sailing w ...

to allow the mounting of heavy guns for this purpose.Rodrigues and Tevezes (2009: p. 193) These were initially wrought iron breech-loading weapon

A breechloader is a firearm in which the user loads the ammunition ( cartridge or shell) via the rear (breech) end of its barrel, as opposed to a muzzleloader, which loads ammunition via the front ( muzzle).

Modern firearms are generally br ...

s known as basilisks, but by the early sixteenth century the navies of the Mediterranean had universally adopted lighter and more accurate muzzleloader

A muzzleloader is any firearm into which the projectile and the propellant charge is loaded from the muzzle of the gun (i.e., from the forward, open end of the gun's barrel). This is distinct from the modern (higher tech and harder to make) desig ...

s, cast in bronze and capable of firing balls or stones weighing up to . In 1489 John of Portugal further contributed to the development of naval artillery by establishing the first standardized teams of trained naval gunners (''bombardeiros'').

Age of Sail

Transition

The 16th century was an era of transition in naval warfare. Since ancient times, war at sea had been fought much like that on land: with

The 16th century was an era of transition in naval warfare. Since ancient times, war at sea had been fought much like that on land: with melee weapon

A melee weapon, hand weapon or close combat weapon is any handheld weapon used in hand-to-hand combat, i.e. for use within the direct physical reach of the weapon itself, essentially functioning as an additional (and more impactful) extension of th ...

s and bows and arrows

The bow and arrow is a ranged weapon system consisting of an elastic launching device (bow) and long-shafted projectiles (arrows). Humans used bows and arrows for hunting and aggression long before recorded history, and the practice was commo ...

, but on floating wooden platforms rather than battlefields. Though the introduction of guns was a significant change, it only slowly changed the dynamics of ship-to-ship combat. As guns became heavier and able to take more powerful gunpowder charges, they needed to be placed lower in the ship, closer to the water line.

Although some 16th-century galley

A galley is a type of ship that is propelled mainly by oars. The galley is characterized by its long, slender hull, shallow draft, and low freeboard (clearance between sea and gunwale). Virtually all types of galleys had sails that could be u ...

s mounted broadside cannon, they did so at the expense of rowing

Rowing is the act of propelling a human-powered watercraft using the sweeping motions of oars to displace water and generate reactional propulsion. Rowing is functionally similar to paddling, but rowing requires oars to be mechanically ...

positions which sacrificed speed and mobility. Most early cannon were still placed in the forecastle

The forecastle ( ; contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le) is the upper deck of a sailing ship forward of the foremast, or, historically, the forward part of a ship with the sailors' living quarters. Related to the latter meaning is the phrase " ...

and aftercastle

An aftercastle (or sometimes aftcastle) is the stern structure behind the mizzenmast and above the transom on large sailing ships, such as carracks, caravels, galleons and galleasses. It usually houses the captain's cabin and perhaps addi ...

of a ship where they might be conveniently pointed in any direction. Early naval artillery was an antipersonnel weapon to deter boarders, because cannon powerful enough to damage ships were heavy enough to destabilize any ship mounting them in an elevated castle.

Throughout the century, naval artillery was the single greatest advantage the Portuguese held over their rivals in the Indian Ocean, and the Portuguese crown spared no expense in procuring and producing the best naval guns European technology permitted. Being a crown industry, cost considerations did not curb the pursuit of the best quality, best innovations and best training. The crown paid wage premiums and bonuses to lure the best European artisans and gunners to advance the industry in Portugal. Every cutting-edge innovation introduced elsewhere was immediately appropriated into Portuguese naval artillery – that includes bronze cannon (Flemish/German), breech-loading swivel-guns, truck carriages (possibly English), and the idea (originally French, c. 1501) of cutting square gunports (''portinhola'' in Portuguese – also already created and tested in the Portuguese ships since 1490) in the hull to allow heavy cannon to be mounted below deck.

In this respect, the Portuguese spearheaded the evolution of modern naval warfare, moving away from the medieval warship, a carrier of armed men, aiming for the grapple, towards the modern idea of a floating artillery piece dedicated to resolving battles by gunnery alone.

The anti-ship broadside

Gun ports cut in the hull of ships were introduced as early as 1501 in France, as early as 1496 in some Mediterranean navies, and in 1490 in Portugal, about a decade before the famousTudor era

The Tudor period occurred between 1485 and 1603 in England and Wales and includes the Elizabethan period during the reign of Elizabeth I until 1603. The Tudor period coincides with the dynasty of the House of Tudor in England that began with t ...

ship ''Mary Rose

The ''Mary Rose'' (launched 1511) is a carrack-type warship of the English Tudor navy of King Henry VIII. She served for 33 years in several wars against France, Scotland, and Brittany. After being substantially rebuilt in 1536, she saw her ...

'' was launched in 1511. This made broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

s, coordinated volleys from all the guns on one side of a ship, possible for the first time in history, at least in theory.

Ships such as ''Mary Rose'' carried a mixture of cannon of different types and sizes, many designed for land use, and using incompatible ammunition at different ranges and rates of fire. ''Mary Rose'', like other ships of the time, was built during a period of rapid development of heavy artillery, and her armament was a mix of old designs and innovations. The heavy armament was a mix of older-type wrought iron and cast bronze guns, which differed considerably in size, range and design. The large iron guns were made up of staves or bars welded into cylinders and then reinforced by shrinking iron hoops and breech loaded, from the back, and equipped with simpler gun-carriages made from hollowed-out elm logs with only one pair of wheels, or without wheels entirely. The bronze guns were cast in one piece and rested on four-wheel carriages which were essentially the same as those used until the 19th century. The breech-loaders were cheaper to produce and both easier and faster to reload, but could take less powerful charges than cast bronze guns. Generally, the bronze guns used cast iron shot and were more suited to penetrate hull sides while the iron guns used stone shot that would shatter on impact and leave large, jagged holes, but both could also fire a variety of ammunition intended to destroy rigging and light structure or injure enemy personnel.

The majority of the guns were small iron guns with short range that could be aimed and fired by a single person. The two most common are the ''bases'', breech-loading swivel gun

A breech-loading swivel gun was a particular type of swivel gun and a small breech-loading cannon invented in the 14th century. It was equipped with a swivel for easy rotation and was loaded by inserting a mug-shaped device called a chamber or b ...

s, most likely placed in the castles, and ''hailshot pieces'', small muzzle-loaders with rectangular bores and fin-like protrusions that were used to support the guns against the railing and allow the ship structure to take the force of the recoil. Though the design is unknown, there were two ''top pieces'' in a 1546 inventory (finished after the sinking) which was probably similar to a base, but placed in one or more of the fighting tops.

During rebuilding in 1536, ''Mary Rose'' had a second tier of carriage-mounted long guns fitted. Records show how the configuration of guns changed as gun-making technology evolved and new classifications were invented. In 1514, the armament consisted mostly of anti-personnel guns like the larger breech-loading iron ''murderers'' and the small ''serpentines'', ''demi-slings'' and stone guns. Only a handful of guns in the first inventory were powerful enough to hole enemy ships, and most would have been supported by the ship's structure rather than resting on carriages. The inventories of both the ''Mary Rose'' and the Tower had changed radically by 1540. There were now the new cast bronze ''cannons'', ''demi-cannons'', ''culverins'' and ''sakers'' and the wrought iron ''port pieces'' (a name that indicated they fired through ports), all of which required carriages, had longer range and were capable of doing serious damage to other ships.

Various types of ammunition could be used for different purposes: plain spherical shot of stone or iron smashed hulls, spiked bar shot and shot linked with chains would tear sails or damage rigging, and

During rebuilding in 1536, ''Mary Rose'' had a second tier of carriage-mounted long guns fitted. Records show how the configuration of guns changed as gun-making technology evolved and new classifications were invented. In 1514, the armament consisted mostly of anti-personnel guns like the larger breech-loading iron ''murderers'' and the small ''serpentines'', ''demi-slings'' and stone guns. Only a handful of guns in the first inventory were powerful enough to hole enemy ships, and most would have been supported by the ship's structure rather than resting on carriages. The inventories of both the ''Mary Rose'' and the Tower had changed radically by 1540. There were now the new cast bronze ''cannons'', ''demi-cannons'', ''culverins'' and ''sakers'' and the wrought iron ''port pieces'' (a name that indicated they fired through ports), all of which required carriages, had longer range and were capable of doing serious damage to other ships.

Various types of ammunition could be used for different purposes: plain spherical shot of stone or iron smashed hulls, spiked bar shot and shot linked with chains would tear sails or damage rigging, and canister shot

Canister shot is a kind of anti-personnel artillery ammunition. Canister shot has been used since the advent of gunpowder-firing artillery in Western armies. However, canister shot saw particularly frequent use on land and at sea in the various ...

packed with sharp flints produced a devastating shotgun

A shotgun (also known as a scattergun, or historically as a fowling piece) is a long-barreled firearm designed to shoot a straight-walled cartridge known as a shotshell, which usually discharges numerous small pellet-like spherical sub- pr ...

effect. Trials made with replicas of culverins and port pieces showed that they could penetrate wood the same thickness of the ''Mary Rose's'' hull planking, indicating a stand-off range of at least 90 m (295 ft). The port pieces proved particularly efficient at smashing large holes in wood when firing stone shot and were a devastating anti-personnel weapon when loaded with flakes or pebbles.

A perrier

Perrier ( , also , ) is a French brand of natural bottled mineral water obtained at its source in Vergèze, located in the Gard ''département''. Perrier is known for its carbonation and its distinctive green bottle.

Perrier was part of th ...

threw a stone projectile three quarters of a mile (1.2 km), while cannon threw a 32-pound ball

A ball is a round object (usually spherical, but can sometimes be ovoid) with several uses. It is used in ball games, where the play of the game follows the state of the ball as it is hit, kicked or thrown by players. Balls can also be used f ...

a full mile (1.6 km), and a culverin

A culverin was initially an ancestor of the hand-held arquebus, but later was used to describe a type of medieval and Renaissance cannon. The term is derived from the French "''couleuvrine''" (from ''couleuvre'' "grass snake", following the ...

a 17-pound ball a mile and a quarter (2 km). Swivel gun

The term swivel gun (or simply swivel) usually refers to a small cannon, mounted on a swiveling stand or fork which allows a very wide arc of movement. Another type of firearm referred to as a swivel gun was an early flintlock combination gun wi ...

s and smaller cannon were often loaded with grapeshot

Grapeshot is a type of artillery round invented by a British Officer during the Napoleonic Wars. It was used mainly as an anti infantry round, but had other uses in naval combat.

In artillery, a grapeshot is a type of ammunition that consists of ...

for antipersonnel use at closer ranges, while the larger cannon might be loaded with a single heavy cannonball to cause structural damage.

In Portugal, the development of the heavy galleon removed even the necessity of bringing carrack firepower to bear in most circumstances. One of them became famous in the conquest of Tunis in 1535, and could carry 366 bronze cannon (a possible exaggeration – or possibly not – of the various European chroniclers of the time, that reported this number; or also possibly counting the weapons in reserve). This ship had an exceptional capacity of fire for its time, illustrating the evolution that was operating at the time, and for this reason, it became known as ''Botafogo

Botafogo (local/standard alternative Brazilian Portuguese pronunciation: ) is a beachfront neighborhood (''bairro'') in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. It is a mostly upper middle class and small commerce community, and is located between the hills o ...

'', meaning literally ''fire maker'', ''torcher'' or ''spitfire'' in popular Portuguese.

Maturation

Naval artillery and tactics stayed relatively constant during the period 1571–1862, with large, sail-powered wooden naval warships mounting a great variety of different types and sizes of cannon as their main armament. By the 1650s, theline of battle

The line of battle is a tactic in naval warfare in which a fleet of ships forms a line end to end. The first example of its use as a tactic is disputed—it has been variously claimed for dates ranging from 1502 to 1652. Line-of-battle tacti ...

had developed as a tactic that could take advantage of the broadside armament. This method became the heart of naval warfare during the Age of Sail

The Age of Sail is a period that lasted at the latest from the mid-16th (or mid- 15th) to the mid-19th centuries, in which the dominance of sailing ships in global trade and warfare culminated, particularly marked by the introduction of nava ...

, with navies adapting their strategies and tactics in order to get the most broadside-on fire. Cannon were mounted on multiple decks to maximise broadside effectiveness. Numbers and calibre differed somewhat with preferred tactics. France and Spain attempted to immobilize ships by destroying rigging with long-range, accurate fire from their swifter and more maneuverable ships, while England and the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands ( Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiograph ...

favoured rapid fire at close range to shatter a ship's hull and disable its crew.

A typical broadside of a Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

ship of the late 18th century could be fired 2–3 times in approximately 5 minutes, depending on the training of the crew, a well trained one being essential to the simple yet detailed process of preparing to fire. French and Spanish crews typically took twice as long to fire an aimed broadside. An 18th-century ship of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which depended on the two colu ...

typically mounted 32-pounder A 32-pounder is a gun firing a shot of 32 pounds weight, a mass of .

Examples include:

*Naval artillery in the Age of Sail

*32-pounder gun – a smooth-bore muzzle-loading gun firing bullets of 32 pounds, c. 1500 – c. 1880

*A size of Dahlgren gu ...

or 36-pounder long gun

The 36-pounder long gun was the largest piece of artillery mounted on French warships of the Age of Sail. They were also used for Coastal defense and fortification. They largely exceeded the heaviest guns fielded by the Army, which were 24-pounder ...

s on a lower deck, and 18- or 24-pounders on an upper deck, with some 12-pounders on the forecastle and quarterdeck. From the late sixteenth century it was routine for naval ships to carry a master gunner, responsible for overseeing the operation of the cannon on board. Originally a prestigious position, its status declined throughout the Age of Sail as responsibility for gunnery strategy was devolved to midshipmen

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Canada (Naval Cadet), Australia, Bangladesh, Namibia, New Zealand, Sout ...

or lieutenants. By the eighteenth century the master gunner had become responsible only for the maintenance of the guns and their carriages, and for overseeing supplies of gunpowder and shot. In status the master gunner remained equal to the boatswain

A boatswain ( , ), bo's'n, bos'n, or bosun, also known as a deck boss, or a qualified member of the deck department, is the most senior rate of the deck department and is responsible for the components of a ship's hull. The boatswain supervis ...

and ship's carpenter as senior warrant officer

Warrant officer (WO) is a rank or category of ranks in the armed forces of many countries. Depending on the country, service, or historical context, warrant officers are sometimes classified as the most junior of the commissioned ranks, the mo ...

s, and was entitled to the support of one or more gunner's mates. In the Royal Navy, the master gunner also directed the "quarter gunners" able seamen with the added responsibility of managing the rate and direction of fire from any set of four gun crews.

The British Admiralty

The Admiralty was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom responsible for the command of the Royal Navy until 1964, historically under its titular head, the Lord High Admiral – one of the Great Officers of State. For much of i ...

did not see fit to provide additional powder to captains to train their crews, generally only allowing 1/3 of the powder loaded onto the ship to be fired in the first six months of a typical voyage, barring hostile action. Instead of live fire practice, most captains exercised their crews by "running" the guns in and out—performing all the steps associated with firing but for the actual discharge. Some wealthy captains—those who had made money capturing prizes or from wealthy families—were known to purchase powder with their own funds to enable their crews to fire real discharges at real targets.

Firing

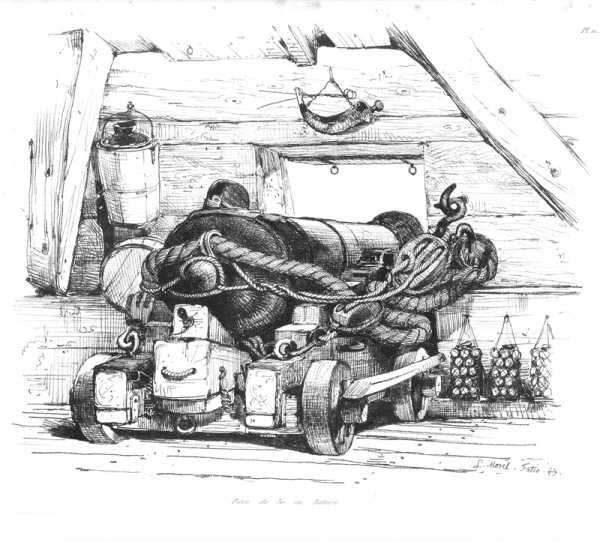

Firing a naval cannon required a great amount of labour and manpower. The propellant was gunpowder, whose bulk had to be kept in a special storage area below deck for safety. ''Powder boys'', typically 10–14 years old, were enlisted to run powder from the armoury up to the gun decks of a vessel as required.

A typical firing procedure follows. A wet swab was used to mop out the interior of the barrel, extinguishing any embers from a previous firing which might set off the next charge of gunpowder prematurely.

Firing a naval cannon required a great amount of labour and manpower. The propellant was gunpowder, whose bulk had to be kept in a special storage area below deck for safety. ''Powder boys'', typically 10–14 years old, were enlisted to run powder from the armoury up to the gun decks of a vessel as required.

A typical firing procedure follows. A wet swab was used to mop out the interior of the barrel, extinguishing any embers from a previous firing which might set off the next charge of gunpowder prematurely. Gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). T ...

, either loose or in a cloth or parchment cartridge

Cartridge may refer to:

Objects

* Cartridge (firearms), a type of modern ammunition

* ROM cartridge, a removable component in an electronic device

* Cartridge (respirator), a type of filter used in respirators

Other uses

* Cartridge (surname), a ...

pierced by a metal 'pricker' through the touch hole, was placed in the barrel and followed by a cloth wad (typically made from canvas and old rope), then rammed home with a rammer. Next the shot was rammed in, followed by another wad (to prevent the cannonball from rolling out of the barrel if the muzzle was depressed.) The gun in its carriage was then 'run out'—men heaved on the gun tackles until the front of the gun carriage

A gun carriage is a frame and mount that supports the gun barrel of an artillery piece, allowing it to be maneuvered and fired. These platforms often had wheels so that the artillery pieces could be moved more easily. Gun carriages are also use ...

was hard up against the ship's bulwark, and the barrel protruding out of the gun port. This took the majority of the guncrew manpower as the total weight of a large cannon in its carriage could reach over two tons, and the ship would probably be rolling.

The touch hole in the rear ('breech') of the cannon was primed with finer gunpowder ('priming powder'), or a 'quill' (from a porcupine or such, or the skin-end of a feather) pre-filled with priming powder, then ignited.

The earlier method of firing a cannon was to apply a

The earlier method of firing a cannon was to apply a linstock

A linstock (also called a lintstock) is a staff with a fork at one end to hold a lighted slow match. The name was adapted from the Dutch ''lontstok'', "match stick". Linstocks were used for discharging cannons in the early days of artillery; th ...

—a wooden staff holding a length of smoldering match at the end—to the touch-hole of the gun. This was dangerous and made accurate shooting from a moving ship difficult, as the gun had to be fired from the side, to avoid its recoil, and there was a noticeable delay between the application of the linstock and the gun firing. In 1745, the British began using ''gunlocks'' (flintlock mechanism

The flintlock mechanism is a type of lock used on muskets, rifles, and pistols from the early 17th to the mid-19th century. It is commonly referred to as a " flintlock" (without the word ''mechanism''), though that term is also commonly used f ...

s fitted to cannon).

The gunlock was operated by pulling a cord, or lanyard

A lanyard is a cord, length of webbing, or strap that may serve any of various functions, which include a means of attachment, restraint, retrieval, and activation and deactivation. A lanyard is also a piece of rigging used to secure or lo ...

. The gun-captain could stand behind the gun, safely beyond its range of recoil, and sight along the barrel, firing when the roll of the ship lined the gun up with the enemy and so avoid the chance of the shot hitting the sea or flying high over the enemy's deck. Despite their advantages, gunlocks spread gradually as they could not be retrofitted to older guns. The British adopted them faster than the French, who had still not generally adopted them by the time of the Battle of Trafalgar (1805), placing them at a disadvantage as they were in general use by the Royal Navy at this time. After the introduction of gunlocks, linstocks were retained, but only as a backup means of firing.

The linstock slow match, or the spark from the flintlock, ignited the priming powder, which in turn set off the main charge, which propelled the shot out of the barrel. When the gun discharged, the recoil sent it backwards until it was stopped by the breech rope—a sturdy rope made fast to ring bolts set into the bulwarks, and a turn taken about the gun's cascabel, the knob at the end of the gun barrel.

Artillery and shot

The types of artillery used varied from nation and time period. The more important types included the demi-cannon, theculverin

A culverin was initially an ancestor of the hand-held arquebus, but later was used to describe a type of medieval and Renaissance cannon. The term is derived from the French "''couleuvrine''" (from ''couleuvre'' "grass snake", following the ...

and demi-culverin

The demi-culverin was a medium cannon similar to but slightly larger than a saker and smaller than a regular culverin developed in the late 16th century. Barrels of demi-culverins were typically about long, had a calibre of and could weigh up to ...

, and the carronade

A carronade is a short, smoothbore, cast-iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color wh ...

. One descriptive characteristic which was commonly used was to define guns by their 'pound' rating: theoretically, the weight of a single solid iron shot fired by that bore of cannon. Common sizes were 42-pounders, 36-pounders, 32-pounders, 24-pounders, 18-pounders, 12-pounders, 9-pounders, 8-pounders, 6-pounders, and various smaller calibres. French ships used standardized guns of 36-pound, 24-pound and 12-pound calibres, augmented by smaller pieces. In general, larger ships carrying more guns carried larger ones as well.

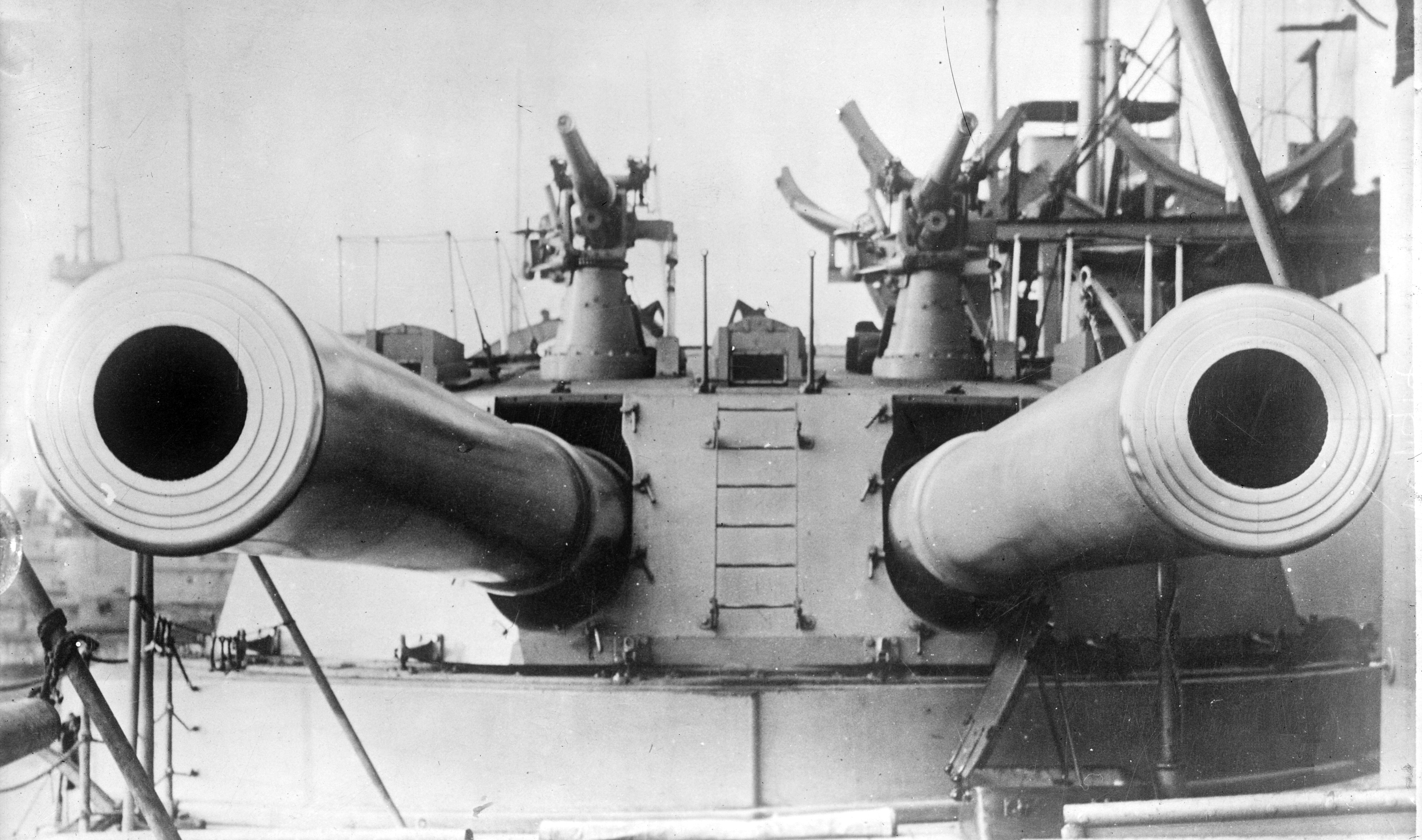

The muzzle-loading design and weight of the iron placed design constraints on the length and size of naval guns. Muzzle loading required the cannon muzzle to be positioned within the hull of the ship for loading. The hull is only so wide, with guns on both sides, and hatchways in the centre of the deck also limit the room available. Weight is always a great concern in ship design as it affects speed, stability, and buoyancy. The desire for longer guns for greater range and accuracy, and greater weight of shot for more destructive power, led to some interesting gun designs.

One unique naval gun was the long nine. It was a proportionately longer-barrelled 9-pounder. Its typical mounting as a bow or stern chaser, where it was not perpendicular to the keel, allowed room to operate this longer weapon. In a chase situation, the gun's greater range came into play. However, the desire to reduce weight in the ends of the ship and the relative fragility of the bow and stern portions of the hull limited this role to a 9-pounder, rather than one which used a 12 or 24 pound shot.

In the reign of

The muzzle-loading design and weight of the iron placed design constraints on the length and size of naval guns. Muzzle loading required the cannon muzzle to be positioned within the hull of the ship for loading. The hull is only so wide, with guns on both sides, and hatchways in the centre of the deck also limit the room available. Weight is always a great concern in ship design as it affects speed, stability, and buoyancy. The desire for longer guns for greater range and accuracy, and greater weight of shot for more destructive power, led to some interesting gun designs.

One unique naval gun was the long nine. It was a proportionately longer-barrelled 9-pounder. Its typical mounting as a bow or stern chaser, where it was not perpendicular to the keel, allowed room to operate this longer weapon. In a chase situation, the gun's greater range came into play. However, the desire to reduce weight in the ends of the ship and the relative fragility of the bow and stern portions of the hull limited this role to a 9-pounder, rather than one which used a 12 or 24 pound shot.

In the reign of Queen Elizabeth

Queen Elizabeth, Queen Elisabeth or Elizabeth the Queen may refer to:

Queens regnant

* Elizabeth I (1533–1603; ), Queen of England and Ireland

* Elizabeth II (1926–2022; ), Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms

* Queen ...

advances in manufacturing technology allowed the English Navy Royal

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fra ...

to start using matched cannon firing standard ammunition,BBC: 'Superguns' of Elizabeth I's navy.The wreck of an English

full-rigged pinnace

The full-rigged pinnace was the larger of two types of vessel called a pinnace in use from the sixteenth century.

Etymology

The word ''pinnace'', and similar words in many languages (as far afield as Indonesia, where the boat "pinisi" took its ...

dating from around 1592 with 12 matched guns was discovered, and guns were recovered in 2009 allowing firing of coordinated broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

s (although that was more of a matter of improved training and discipline than of matched guns).

Different types of shot were employed for various situations. Standard fare was the round shot

A round shot (also called solid shot or simply ball) is a solid spherical projectile without explosive charge, launched from a gun. Its diameter is slightly less than the bore of the barrel from which it is shot. A round shot fired from a lar ...

—spherical cast-iron shot used for smashing through the enemy's hull, holing his waterline, smashing gun carriages and breaking masts and yards, with a secondary effect of sending large wooden splinters flying about to maim and kill the enemy crew. At very close range, two round shots could be loaded in one gun and fired together. "Double-shotting", as it was called, lowered the effective range and accuracy of the gun, but could be devastating within pistol shot range.

Canister shot

Canister shot is a kind of anti-personnel artillery ammunition. Canister shot has been used since the advent of gunpowder-firing artillery in Western armies. However, canister shot saw particularly frequent use on land and at sea in the various ...

consisted of metallic canisters which broke open upon firing, each of which was filled with hundreds of lead musket balls for clearing decks like a giant shotgun

A shotgun (also known as a scattergun, or historically as a fowling piece) is a long-barreled firearm designed to shoot a straight-walled cartridge known as a shotshell, which usually discharges numerous small pellet-like spherical sub- pr ...

blast; it is commonly mistakenly called "grapeshot", both today and in historic accounts (typically those of landsmen). Although canister shot could be used aboard ship, it was more traditionally an army artillery projectile for clearing fields of infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

. Grapeshot

Grapeshot is a type of artillery round invented by a British Officer during the Napoleonic Wars. It was used mainly as an anti infantry round, but had other uses in naval combat.

In artillery, a grapeshot is a type of ammunition that consists of ...

was similar in that it also consisted of multiple (usually 9–12) projectiles that separated upon firing, except that the shot was larger (at least 1 inch in diameter, up to 3 inches or larger for heavier guns), and it either came in bundles held together by lengths of rope wrapped around the balls and wedged between, with wooden bases to act as wadding when rammed down the muzzles, or in canvas sacks wrapped about with rope. The name "grapeshot" comes from the former's apparent resemblance to a bunch of grapes. When fired, the inertial forces would cause the bundle to disintegrate, and the shot would spread out to hit numerous targets. Grapeshot was a naval weapon, and existed for almost as long as naval artillery. The larger size of the grapeshot projectiles was desirable because it was more capable of cutting thick cordage and smashing equipment than the relatively smaller musket balls of a canister shot, although it could rarely penetrate a wooden hull. Although grapeshot won great popular fame as a weapon used against enemy crew on open decks (especially when massed in great numbers, such as for a boarding attempt), it was originally designed and carried primarily for cutting up enemy rigging.

A more specialized shot for similar use, chain-shot

In artillery, chain shot is a type of cannon projectile formed of two sub-calibre balls, or half-balls, chained together. Bar shot is similar, but joined by a solid bar. They were used in the age of sailing ships and black powder cannon to sho ...

consisted of two iron balls joined together with a chain, and was particularly designed for cutting large swaths of rigging

Rigging comprises the system of ropes, cables and chains, which support a sailing ship or sail boat's masts—''standing rigging'', including shrouds and stays—and which adjust the position of the vessel's sails and spars to which they ar ...

—anti-boarding netting and sails. It was far more effective than other projectiles in this use, but was of little use for any other purpose. ''Bar shot'' was similar, except that it used a solid bar to join the two balls; the bar could sometimes also extend upon firing. Series of long chain links were also used in a similar way. Bags of junk, such as scrap metal, bolts, rocks, gravel, or old musket balls, were known as 'langrage', and were fired to injure enemy crews (although this was not common, and when it was used, it was generally aboard non-commissioned vessels such as privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

s, actual pirate ships

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

, merchantmen, and others who couldn't afford real ammunition).

In China and other parts of Asia, fire arrow

Fire arrows were one of the earliest forms of weaponized gunpowder, being used from the 9th century onward. Not to be confused with earlier incendiary arrow projectiles, the fire arrow was a gunpowder weapon which receives its name from the tra ...

s were thick, dartlike, rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entir ...

-propelled incendiary projectiles with barbed points, wrapped with pitch-soaked canvas which took fire when the rocket was launched, which could either be from special launching racks or from a cannon barrel (see ''Chongtong

The Chongtong ( Hangul: 총통, Hanja: 銃筒) was a term for military firearms of Goryeo and Joseon dynasty. The size of chongtong varies from small firearm to large cannon, and underwent upgrades, which can be separated in three generation ty ...

'', '' Bō hiya''.) The point stuck in sails, hulls or spars and set fire to the enemy ship. In Western naval warfare, shore forts sometimes heated iron shot red-hot in a special furnace before loading it (with water-soaked wads to prevent it from setting off the powder charge prematurely.) The hot shot lodging in a ship's dry timbers would set the ship afire. Because of the danger of fire aboard (and the difficulty of heating and transporting the red-hot shot aboard ship), heated shot was seldom used from ship-mounted cannon, as the danger to the vessel deploying it was almost as great as to the enemy; fire was the single greatest fear of all men sailing in wooden ships. Consequently, for men aboard these vessels, going up against shore artillery firing heated shot was a terrifying experience, and typically wooden fleets were not expected to brave such fire except in cases of great emergency, as a single heated shot could easily destroy the entire ship and crew, while the same ship could typically be expected to survive numerous hits from normal solid shot.

In later years, the spherical exploding shell came into use. It first saw use in shore fortifications, and then relatively low-risk applications such as bomb-ketches, which used mortars, which required an explosive shell to be effective. However, the long trajectory of a mortar meant that long fuses could be used, which reduced the risk of premature explosion, and such vessels were small and cheap in any case. It took some time for them to be adopted aboard other combat ships, largely due to the imprecise nature of the fuses

Fuse or FUSE may refer to:

Devices

* Fuse (electrical), a device used in electrical systems to protect against excessive current

** Fuse (automotive), a class of fuses for vehicles

* Fuse (hydraulic), a device used in hydraulic systems to protec ...

then available; with the short fuse-lengths required at naval battle ranges, it was not uncommon for shells to explode inside the gun barrel, or shortly after leaving the muzzle, which would pose a great risk to the vessel, and combat vessels represented a very large investment which a government could ill afford to lose. The risk of having to have such dangerous ammunition stocked above waterline during combat was also cited, as gunpowder in a rigid enclosure will explode with far more violence than if simply packed in a fabric sack, as propellant charges were. The strongly traditionalist nature of many senior naval officers was also a factor. Nevertheless, explosive shells were adopted for use aboard ship by the early 19th century. It had already been proven, from ships facing bombardment from shell-armed shore batteries, that wooden ships were vulnerable to shell-fire, which both caused massive blast and wood- and metal-fragmentation damage (and hence very high crew casualties), but also scattered red-hot, jagged fragments all about, which embedded themselves into the wooden hull and acted much the same as heated shot, or simply ignited many of the flammable objects and materials lying about on a normal wooden ship, lighting oils, tar, tarred cords, powder charges, etc. The quick destruction wrought by explosive shells on vessels during the American Civil War brought quick recognition of this in most cases.

Although it is popularly believed that it was the advent of the ironclad vessel that single-handedly brought about the end of the wooden sailing ship, the recognition of their terrible vulnerability to explosive shells was equally vital in this transition, if not more so. Even without the factor of armored hulls to consider, the spectre of fleets of wooden ships decimating each other with shell-fire was unattractive to naval nations like Great Britain, which relied not only on maintaining a great fleet, but also on adding captured enemy vessels to it. The idea of a battle that, even in victory, would likely cost them over half of their engaged vessels and probably leave few if any suitable candidates for capture was unappealing. Combined with the protection afforded by ironclad hulls, the destructive power of explosive shells on wooden vessels ensured their rapid replacement in the first-line combat duties with ironclad vessels.

Bomb ketch

The

The bomb ketch

A bomb vessel, bomb ship, bomb ketch, or simply bomb was a type of wooden sailing naval ship. Its primary armament was not cannons (long guns or carronades) – although bomb vessels carried a few cannons for self-defence – but mortars mounted ...

was developed as a wooden sailing naval ship

A naval ship is a military ship (or sometimes boat, depending on classification) used by a navy. Naval ships are differentiated from civilian ships by construction and purpose. Generally, naval ships are Damage control, damage resilient a ...

with its primary armament

A weapon, arm or armament is any implement or device that can be used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime, law enforcement, s ...

as mortars

Mortar may refer to:

* Mortar (weapon), an indirect-fire infantry weapon

* Mortar (masonry), a material used to fill the gaps between blocks and bind them together

* Mortar and pestle, a tool pair used to crush or grind

* Mortar, Bihar, a villag ...

mounted forward near the bow and elevated to a high angle, and projecting their fire in a ballistic arc. Explosive shells or carcasses were employed rather than solid shot. Bomb vessels were specialized ships designed for bombarding (hence the name) fixed positions on land.

The first recorded deployment of bomb vessels by the English was for the Siege of Calais in 1347 when Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

deployed single deck ships with Bombardes and other artillery.

The first specialised bomb vessels were built towards the end of the 17th century, based on the designs of Bernard Renau d'Eliçagaray, and used by the French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

. Five such vessels were used to shell Algiers in 1682 destroying the land forts, and killing some 700 defenders. Two years later the French repeated their success at Genoa. The early French bomb vessels had two forward-pointing mortars fixed side-by-side on the foredeck. To aim these weapons, the entire ship was rotated by letting out or pulling in a spring anchor

An anchor is a device, normally made of metal , used to secure a vessel to the bed of a body of water to prevent the craft from drifting due to wind or current. The word derives from Latin ''ancora'', which itself comes from the Greek � ...

. The range was usually controlled by adjusting the gunpowder charge.

The Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

continued to refine the class over the next century or more, after Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

exiles brought designs over to England and the United Provinces. The side-by-side, forward-pointing mortars were replaced in the British designs by mortars mounted on the centerline on revolving platforms. These platforms were supported by strong internal wooden framework to transmit the forces of firing the weapons to the hull. The interstices of the framework were used as storage areas for ammunition. Early bomb vessels were rigged as ketch

A ketch is a two- masted sailboat whose mainmast is taller than the mizzen mast (or aft-mast), and whose mizzen mast is stepped forward of the rudder post. The mizzen mast stepped forward of the rudder post is what distinguishes the ketch fr ...

es with two masts. They were awkward vessels to handle, in part because bomb ketches typically had the masts stepped farther aft than would have been normal in other vessels of similar rig, in order to accommodate the mortars forward and provide a clear area for their forward fire. As a result, by the 1800s British bomb vessels were designed as full-rigged ship

A full-rigged ship or fully rigged ship is a sailing vessel's sail plan with three or more masts, all of them square-rigged. A full-rigged ship is said to have a ship rig or be ship-rigged. Such vessels also have each mast stepped in three s ...

s with three masts, and two mortars, one between each neighboring pair of masts.

Scientific gunnery

The art of gunnery was put on a scientific basis in the mid-18th century. British military engineerBenjamin Robins

Benjamin Robins (170729 July 1751) was a pioneering British scientist, Newtonian mathematician, and military engineer.

He wrote an influential treatise on gunnery, for the first time introducing Newtonian science to military men, was an early en ...

used Newtonian mechanics

Newton's laws of motion are three basic laws of classical mechanics that describe the relationship between the motion of an object and the forces acting on it. These laws can be paraphrased as follows:

# A body remains at rest, or in motio ...

to calculate the projectile trajectory while taking the air resistance

In fluid dynamics, drag (sometimes called air resistance, a type of friction, or fluid resistance, another type of friction or fluid friction) is a force acting opposite to the relative motion of any object moving with respect to a surrounding flu ...

into account. He also carried out an extensive series of experiments in gunnery, embodying his results in his famous treatise on New Principles in Gunnery

' (1742), which contains a description of his

ballistic pendulum

A ballistic pendulum is a device for measuring a bullet's momentum, from which it is possible to calculate the velocity and kinetic energy. Ballistic pendulums have been largely rendered obsolete by modern chronographs, which allow direct meas ...

(see chronograph

A chronograph is a specific type of watch that is used as a stopwatch combined with a display watch. A basic chronograph has an independent sweep second hand and a minute sub-dial; it can be started, stopped, and returned to zero by successiv ...

).

Robins also made a number of important experiments on the resistance of the air to the motion of projectiles, and on the force of gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). T ...

, with computation of the velocities thereby communicated to projectiles. He compared the results of his theory with experimental determinations of the ranges of mortars and cannon, and gave practical maxims for the management of artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during si ...

. He also made observations on the flight of rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entir ...

s, and wrote on the advantages of rifled

In firearms, rifling is machining helical grooves into the internal (bore) surface of a gun's barrel for the purpose of exerting torque and thus imparting a spin to a projectile around its longitudinal axis during shooting to stabilize the ...

gun barrels.

Robins argued for the use of larger bore cannon and the importance of tightly fitting cannonballs. His work on gunnery was translated into German by Leonhard Euler

Leonhard Euler ( , ; 15 April 170718 September 1783) was a Swiss mathematician, physicist, astronomer, geographer, logician and engineer who founded the studies of graph theory and topology and made pioneering and influential discoveries ...

and was heavily influential on the development of naval weaponry across Europe. Another artillery scientist was George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the US Army under Pre ...

.

Warrant Officer George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the US Army under Pre ...

was a Master Gunner in the United Navy. He wrote Marshall's Practical Marine Gunnery

' in 1822. Marshall was a naval artillery specialist. The book was the first scientific-technical book on naval artillery published in the United States for the U.S. Navy. He discussed cannons and fireworks. The book discusses the dimensions and apparatus necessary for the equipment of naval artillery. It features tables and charts. The book goes into further details regarding the distance of a shot on a ship based on the sound of the gun, which was found to fly at a rate of 1142 feet in one second. It was the standard of the time. According to Marshall's equation after seeing the flash of a cannon and hearing the blast the gunner would count the seconds until impact. This way a trained ear would know the distance a cannonball traveled based on ear training. The book example outlines a 9-second scenario where the distance the cannon was fired from the gunner was approximately 10,278 feet or 3,426 yards.

Technical innovations

By the outbreak of theFrench Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted France against Britain, Austria, Pruss ...

in 1793, a series of technical innovations over the course of the late 18th century combined to give the British fleet a distinct superiority over the ships of the French and Spanish navies.

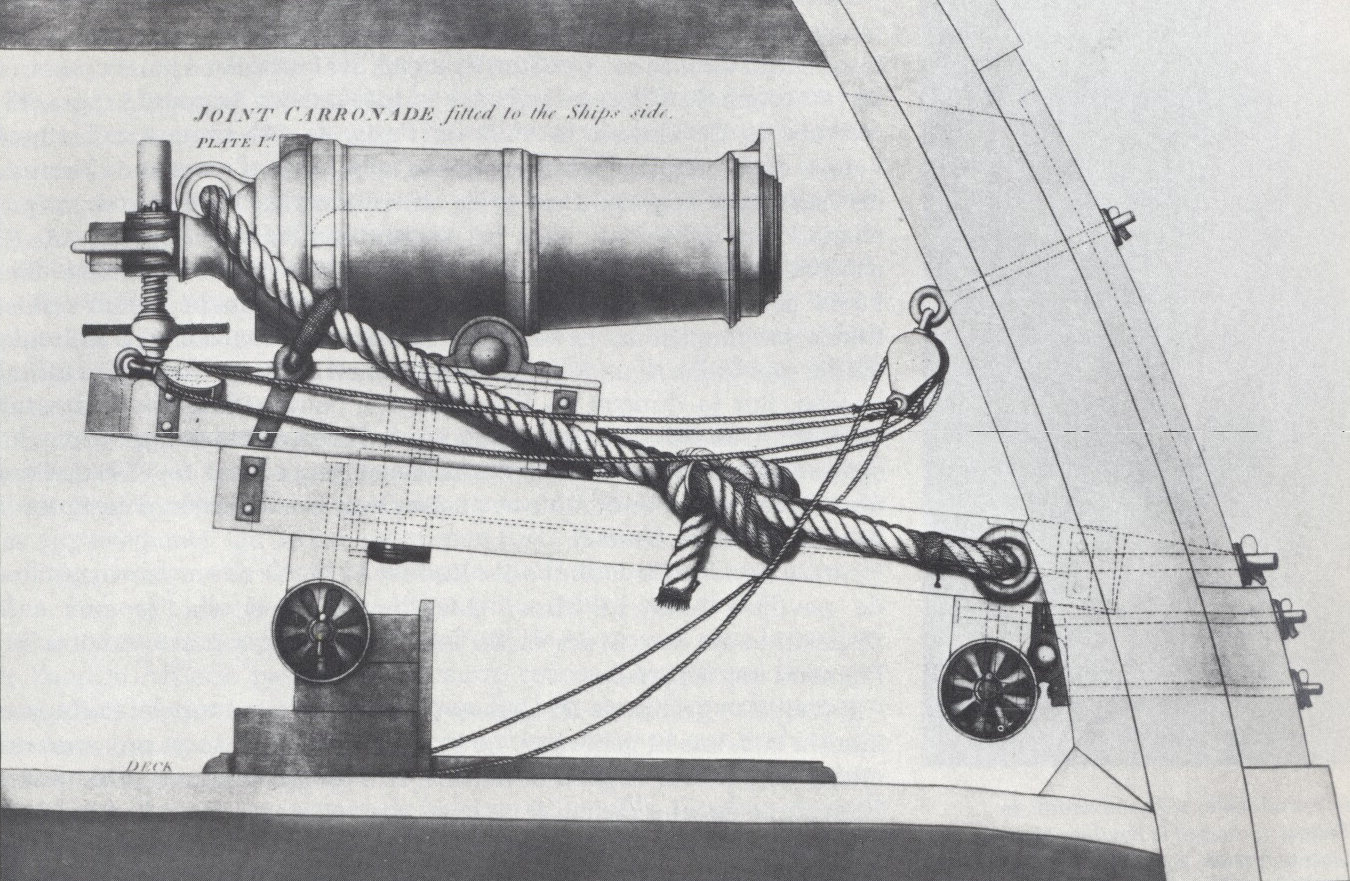

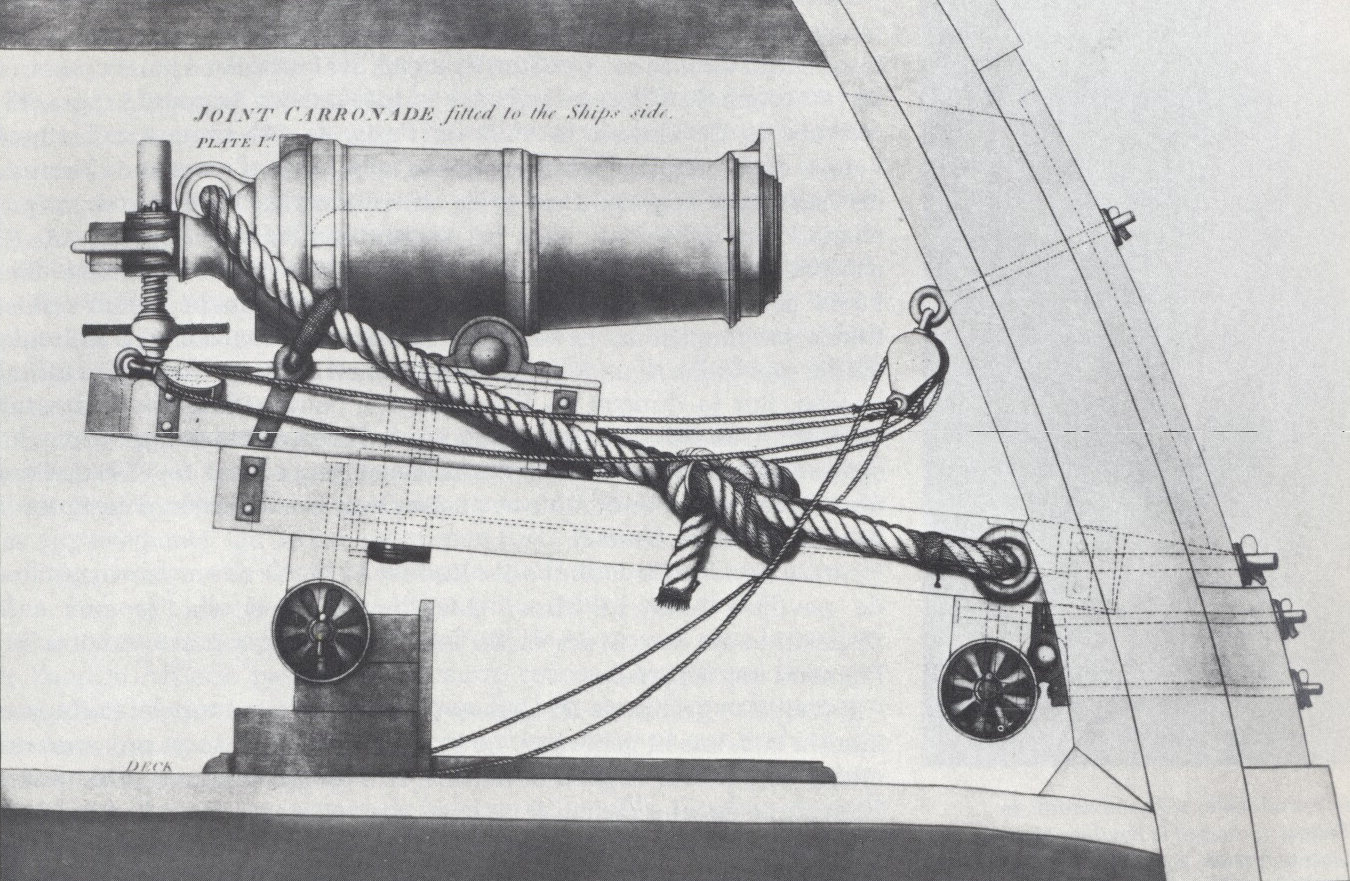

The

The carronade

A carronade is a short, smoothbore, cast-iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color wh ...

was a short-barrelled gun which threw a heavy ball developed by the Carron Company

The Carron Company was an ironworks established in 1759 on the banks of the River Carron near Falkirk, in Stirlingshire, Scotland. After initial problems, the company was at the forefront of the Industrial Revolution in the United Kingdom. T ...

, a Scottish ironworks, in 1778. Because of irregularities in the size of cannonballs and the difficulty of boring out gun barrels, there was usually a considerable gap between the ball and the bore—often as much as a quarter of an inch—with a consequent loss of efficiency. This gap was known as the "windage". The manufacturing practices introduced by the Carron Company reduced the windage considerably, enabling the ball to be fired with less powder and hence a smaller and lighter gun. The carronade was half the weight of an equivalent long gun, but could throw a heavy ball over a limited distance. The light weight of the carronade meant that the guns could be added to the forecastle and quarterdeck of frigates and ships of the line, increasing firepower without affecting the ship's sailing qualities. It became known as the "Smasher" and gave ships armed with carronades a great advantage at short range.

The mounting, attached to the side of the ship on a pivot, took the recoil on a slider. The reduced recoil did not alter the alignment of the gun. The smaller gunpowder charge reduced the guns' heating in action. The pamphlet advocated the use of woollen cartridges, which, although more expensive, eliminated the need for wadding

Wadding is a disc of material used in guns to seal gas behind a projectile (a bullet or ball), or to separate the propellant from loosely packed shots.

Wadding can be crucial to a gun's efficiency, since any gas that leaks past a projectile as i ...

and worming. Simplifying gunnery for comparatively untrained merchant seamen in both aim and reloading was part of the rationale for the gun. The replacement of trunnions by a bolt underneath, to connect the gun to the mounting, reduced the width of the carriage enhancing the wide angle of fire. A carronade weighed a quarter as much and used a quarter to a third of the gunpowder charge for a long gun firing the same cannonball.

Its invention is variously ascribed to Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on th ...

Robert Melvill

General Robert Melvill (or Melville) LLD (12 October 1723 – 29 August 1809) was a Scottish soldier, antiquary, botanist and inventor.

Melvill invented (1759) the Carronade, a cast-iron cannon popular for 100 years, in co-operation with the C ...

e in 1759, or to Charles Gascoigne

Charles Gascoigne (1738–1806) was a British industrialist at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. He was a partner and manager of the Carron Company ironworks in its early years, but left in 1786, before the company's success became o ...

, manager of the Carron Company

The Carron Company was an ironworks established in 1759 on the banks of the River Carron near Falkirk, in Stirlingshire, Scotland. After initial problems, the company was at the forefront of the Industrial Revolution in the United Kingdom. T ...

from 1769 to 1779. Carronades initially became popular on British merchant ships during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. A lightweight gun that needed only a small gun crew and was devastating at short range was a weapon well suited to defending merchant ships against French and American privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

s. In the Action of 4 September 1782

The action of 4 September 1782 was a small naval engagement fought off the Île de Batz between a French naval frigate, , and a Royal Naval frigate, . This battle was notable as the first proper use of a carronade, and so effective was this we ...

, the impact of a single carronade broadside fired at close range by the frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed an ...

HMS ''Rainbow'' under Henry Trollope

Admiral Sir Henry Trollope, GCB (20 April 1756 – 2 November 1839) was an officer of the British Royal Navy.

Early life

Henry Trollope was born the son of the Reverend John Trollope of Bucklebury on 20 April 1756. His paternal grandfather, als ...

caused a wounded French captain to capitulate and surrender the ''Hebe'' after a short fight.

Flintlock