melting of glaciers on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The retreat of glaciers since 1850 affects the availability of fresh water for irrigation and domestic use, mountain recreation, animals and plants that depend on glacier-melt, and, in the longer term, the level of the oceans.

Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change

I

Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

[Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1211–1362, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.011. The retreat of mountain glaciers, notably in western North America, Asia, the Alps and

Though the glaciers of the Alps have received more attention from glaciologists than in other areas of Europe, research indicates that glaciers in northern Europe are also retreating. Since the end of World War II,

Though the glaciers of the Alps have received more attention from glaciologists than in other areas of Europe, research indicates that glaciers in northern Europe are also retreating. Since the end of World War II,  In the Spanish Pyrenees, recent studies have shown important losses in extent and volume of the glaciers of the

In the Spanish Pyrenees, recent studies have shown important losses in extent and volume of the glaciers of the

The Himalayas and other mountain chains of central Asia support large glaciated regions. An estimated 15,000 glaciers can be found in the greater Himalayas, with double that number in the Hindu Kush and Karakoram and Tien Shan ranges, and comprise the largest glaciated region outside the poles. These glaciers provide critical water supplies to arid countries such as

The Himalayas and other mountain chains of central Asia support large glaciated regions. An estimated 15,000 glaciers can be found in the greater Himalayas, with double that number in the Hindu Kush and Karakoram and Tien Shan ranges, and comprise the largest glaciated region outside the poles. These glaciers provide critical water supplies to arid countries such as  With the retreat of glaciers in the Himalayas, a number of glacial lakes have been created. A growing concern is the potential for

With the retreat of glaciers in the Himalayas, a number of glacial lakes have been created. A growing concern is the potential for

North American glaciers are primarily located along the spine of the Rocky Mountains in the United States and Canada, and the Pacific Coast Ranges extending from northern California to

North American glaciers are primarily located along the spine of the Rocky Mountains in the United States and Canada, and the Pacific Coast Ranges extending from northern California to

As recently as 1975 many North Cascade glaciers were advancing due to cooler weather and increased precipitation that occurred from 1944 to 1976. By 1987 the North Cascade glaciers were retreating and the pace had increased each decade since the mid-1970s. Between 1984 and 2005 the North Cascade glaciers lost an average of more than in thickness and 20–40 percent of their volume.

Glaciologists researching the North Cascades found that all 47 monitored glaciers are receding while four glaciers— Spider Glacier, Lewis Glacier, Milk Lake Glacier and

As recently as 1975 many North Cascade glaciers were advancing due to cooler weather and increased precipitation that occurred from 1944 to 1976. By 1987 the North Cascade glaciers were retreating and the pace had increased each decade since the mid-1970s. Between 1984 and 2005 the North Cascade glaciers lost an average of more than in thickness and 20–40 percent of their volume.

Glaciologists researching the North Cascades found that all 47 monitored glaciers are receding while four glaciers— Spider Glacier, Lewis Glacier, Milk Lake Glacier and

File:Grinnell Glacier 1938.jpg, 1938 ''

The semiarid climate of Wyoming still manages to support about a dozen small glaciers within

In the

In the

There are thousands of glaciers in Alaska but only few have been named. The Columbia Glacier near Valdez in

There are thousands of glaciers in Alaska but only few have been named. The Columbia Glacier near Valdez in

Deglaciation Deglaciation is the transition from full glacial conditions during ice ages, to warm interglacials, characterized by global warming and sea level rise due to change in continental ice volume. Thus, it refers to the retreat of a glacier, an ice she ...

occurs naturally at the end of ice ages, but glaciologist

Glaciology (; ) is the scientific study of glaciers, or more generally ice and natural phenomena that involve ice.

Glaciology is an interdisciplinary Earth science that integrates geophysics, geology, physical geography, geomorphology, clim ...

s find the current glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such as ...

retreat is accelerated by the measured increase of atmospheric greenhouse gas

A greenhouse gas (GHG or GhG) is a gas that absorbs and emits radiant energy within the thermal infrared range, causing the greenhouse effect. The primary greenhouse gases in Earth's atmosphere are water vapor (), carbon dioxide (), methane ...

es—an effect of climate change. Mid-latitude mountain ranges such as the Himalayas

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 100 ...

, Rockies

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

, Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Sw ...

, Cascades, Southern Alps

The Southern Alps (; officially Southern Alps / Kā Tiritiri o te Moana) is a mountain range extending along much of the length of New Zealand's South Island, reaching its greatest elevations near the range's western side. The name "Southern ...

, and the southern Andes, as well as isolated tropical summits such as Mount Kilimanjaro

Mount Kilimanjaro () is a dormant volcano in Tanzania. It has three volcanic cones: Kibo, Mawenzi, and Shira. It is the highest mountain in Africa and the highest free-standing mountain above sea level in the world: above sea level and ab ...

in Africa, are showing some of the largest proportionate glacial losses. Excluding peripheral glaciers of ice sheets, the total cumulated global glacial losses over the 26 year period from 1993–2018 were likely 5500 gigatons, or 210 gigatons per yr.Fox-Kemper, B., H.T. Hewitt, C. Xiao, G. Aðalgeirsdóttir, S.S. Drijfhout, T.L. Edwards, N.R. Golledge, M. Hemer, R.E. Kopp, G. Krinner, A. Mix, D. Notz, S. Nowicki, I.S. Nurhati, L. Ruiz, J.-B. Sallée, A.B.A. Slangen, and Y. Yu, 2021Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change

I

Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

[Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1211–1362, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.011. The retreat of mountain glaciers, notably in western North America, Asia, the Alps and

tropical

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the Equator. They are defined in latitude by the Tropic of Cancer in the Northern Hemisphere at N and the Tropic of Capricorn in

the Southern Hemisphere at S. The tropics are also referred to ...

and subtropical

The subtropical zones or subtropics are geographical and climate zones to the north and south of the tropics. Geographically part of the temperate zones of both hemispheres, they cover the middle latitudes from to approximately 35° north and ...

regions of South America, Africa and Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guinea. In ...

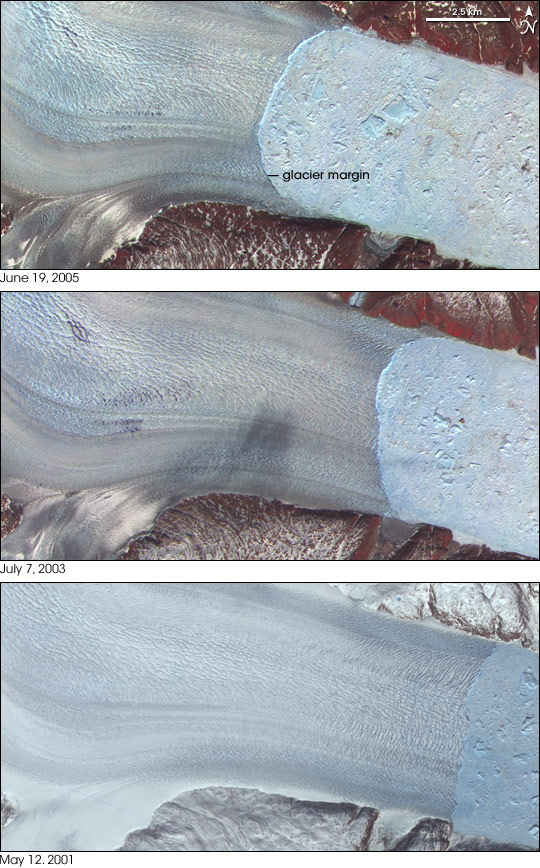

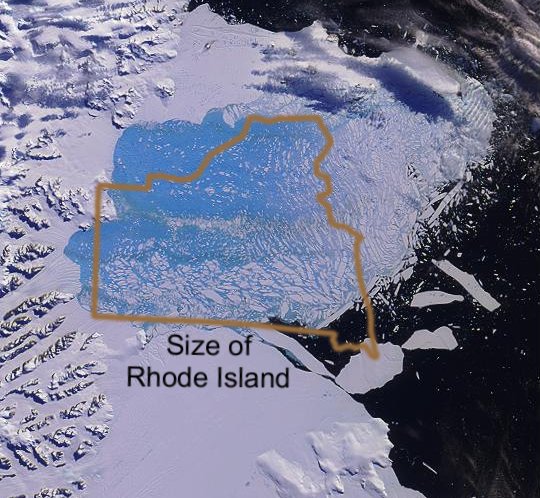

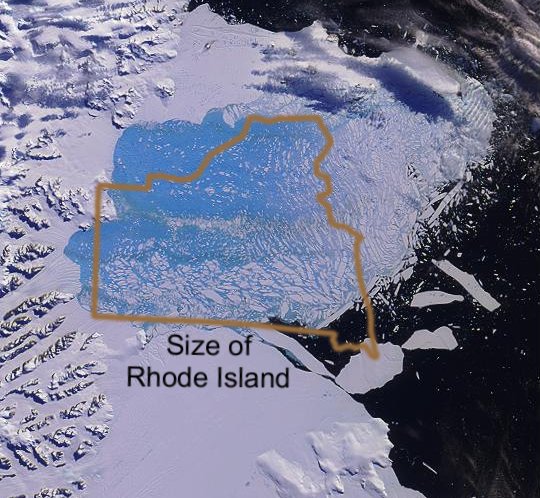

, provide evidence for the rise in global temperatures since the late 19th century. The acceleration of the rate of retreat since 1995 of key outlet glacier

Glacier morphology, or the form a glacier takes, is influenced by temperature, precipitation, topography, and other factors. The goal of glacial morphology is to gain a better understanding of glaciated landscapes and the way they are shaped. ...

s of the Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is ...

and West Antarctic ice sheet

In glaciology, an ice sheet, also known as a continental glacier, is a mass of glacial ice that covers surrounding terrain and is greater than . The only current ice sheets are in Antarctica and Greenland; during the Last Glacial Period at L ...

s may foreshadow a rise in sea level, which would affect coastal regions.

Glacier mass balance

Crucial to the survival of a glacier is its mass balance or surface mass balance (SMB), the difference between accumulation and ablation (sublimation and melting). Climate change may cause variations in both temperature and snowfall, causing ...

is the key determinant of the health of a glacier. If the amount of frozen precipitation in the accumulation zone

On a glacier, the accumulation zone is the area above the firn line, where snowfall accumulates and exceeds the losses from ablation, (melting, evaporation

Evaporation is a type of vaporization that occurs on the surface of a liquid ...

exceeds the quantity of glacial ice lost due to melting or in the ablation zone

Ablation zone or ''ablation area'' refers to the low-altitude area of a glacier or ice sheet below firn with a net loss in ice mass due to melting, sublimation, evaporation, ice calving, aeolian processes like blowing snow, avalanche, and any oth ...

a glacier will advance; if the accumulation is less than the ablation, the glacier will retreat. Glaciers in retreat will have negative mass balances, and if they do not find an equilibrium between accumulation and ablation, will eventually disappear.

The Little Ice Age

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of regional cooling, particularly pronounced in the North Atlantic region. It was not a true ice age of global extent. The term was introduced into scientific literature by François E. Matthes in 1939. Ma ...

was a period from about 1550 to 1850 when certain regions experienced relatively cooler temperatures compared to the time before and after. Subsequently, until about 1940, glaciers around the world retreated as the climate warmed substantially. Glacial retreat slowed and even reversed temporarily, in many cases, between 1950 and 1980 as global temperatures cooled slightly. Since 1980, climate change has led to glacier retreat becoming increasingly rapid and ubiquitous, so much so that some glaciers have disappeared altogether, and the existence of many of the remaining glaciers is threatened. In locations such as the Andes and Himalayas, the demise of glaciers has the potential to affect water supplies.

Causes

The mass balance, or difference betweenaccumulation

Accumulation may refer to:

Finance

* Accumulation function, a mathematical function defined in terms of the ratio future value to present value

* Capital accumulation, the gathering of objects of value

Science and engineering

* Accumulate (highe ...

and ablation

Ablation ( la, ablatio – removal) is removal or destruction of something from an object by vaporization, chipping, erosive processes or by other means. Examples of ablative materials are described below, and include spacecraft material for a ...

(melting and sublimation), of a glacier is crucial to its survival. Climate change may cause variations in both temperature and snowfall, resulting in changes in mass balance. A glacier with a sustained negative balance loses equilibrium and retreats. A sustained positive balance is also out of equilibrium and will advance to reestablish equilibrium. Currently, nearly all glaciers have a negative mass balance and are retreating.

Glacier retreat results in the loss of the low-elevation region of the glacier. Since higher elevations are cooler, the disappearance of the lowest portion decreases overall ablation, thereby increasing mass balance and potentially reestablishing equilibrium. If the mass balance of a significant portion of the accumulation zone of the glacier is negative, it is in disequilibrium with the climate and will melt away without a colder climate and/or an increase in frozen precipitation.

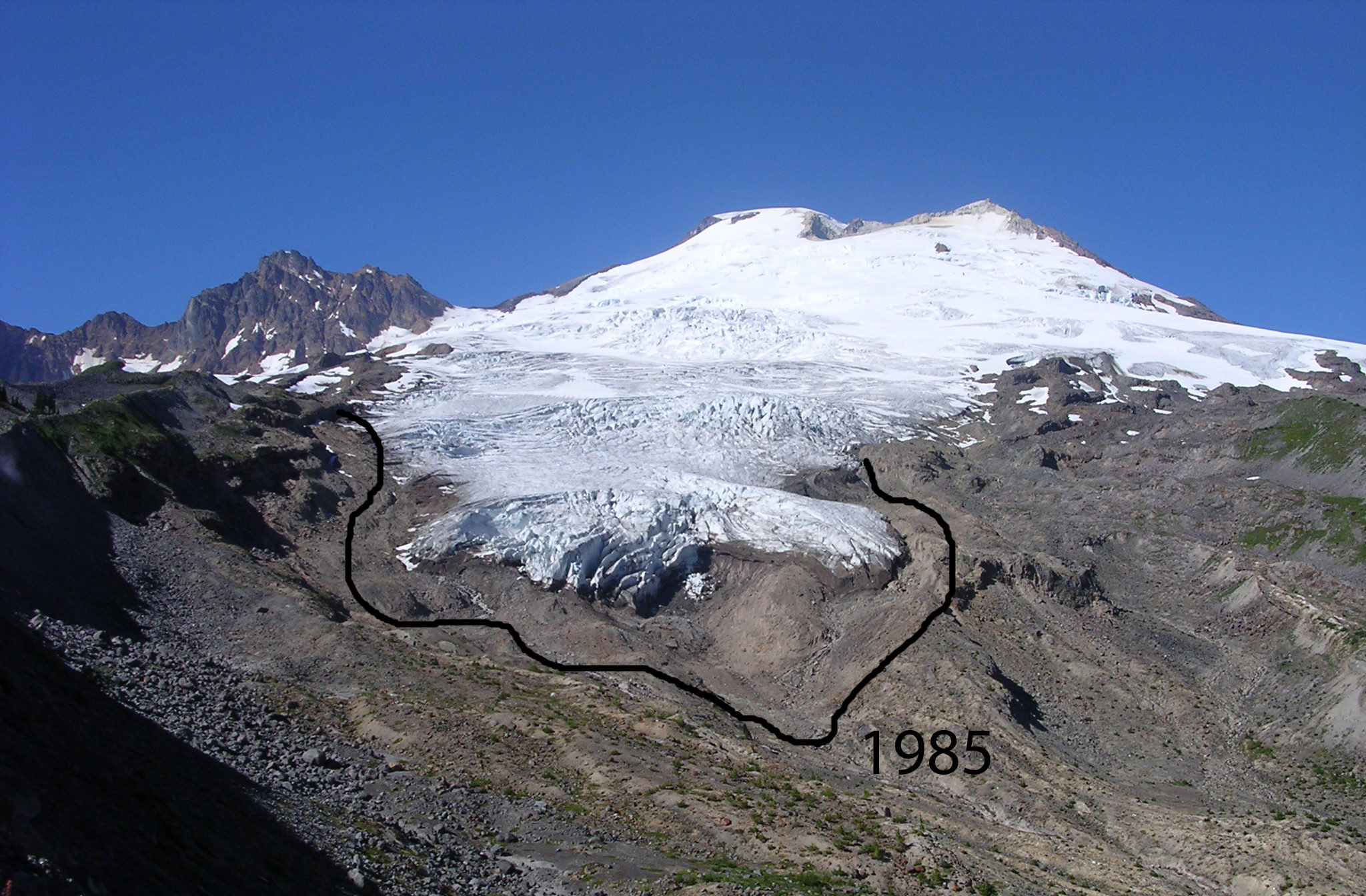

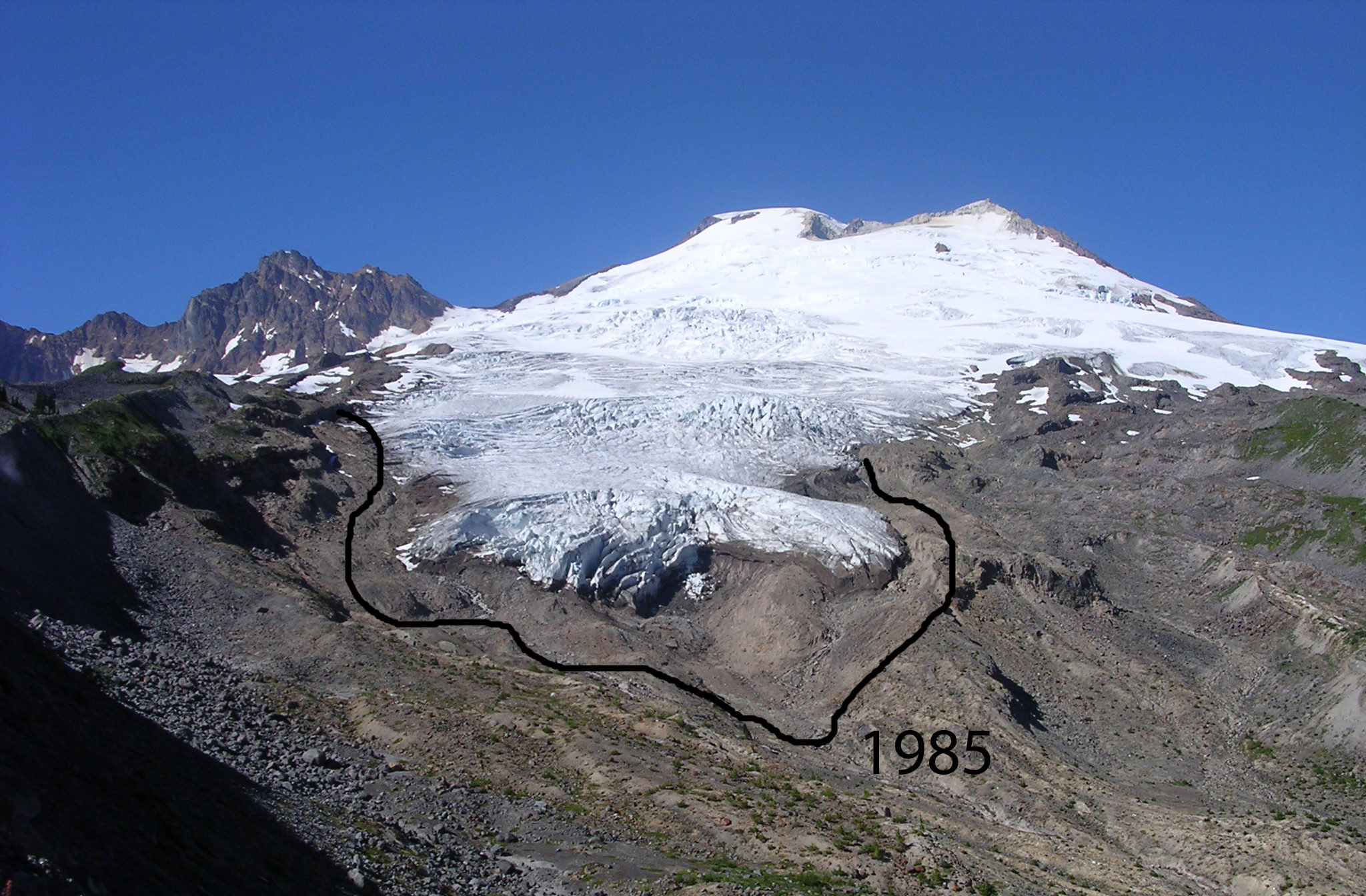

For example, Easton Glacier

Easton Glacier is one of the more prominent alpine glaciers on Mount Baker in the North Cascades of Washington state, United States. Named for Charles F. Easton of Bellingham, who did much to preserve the history of Mount Baker, it is positioned o ...

in Washington state, U.S. will likely shrink to half its size but at a slowing rate of reduction and stabilize at that size despite the warmer temperature over a few decades. However, the Grinnell Glacier

Grinnell Glacier is in the heart of Glacier National Park in the U.S. state of Montana. The glacier is named for George Bird Grinnell, an early American conservationist and explorer, who was also a strong advocate of ensuring the creation of Glac ...

in Montana, U.S. will shrink at an increasing rate until it disappears. The difference is that the upper section of Easton Glacier remains healthy and snow-covered, while even the upper section of the Grinnell Glacier is bare, is melting and has thinned. Small glaciers with minimal altitude range are most likely to fall into disequilibrium with the climate.

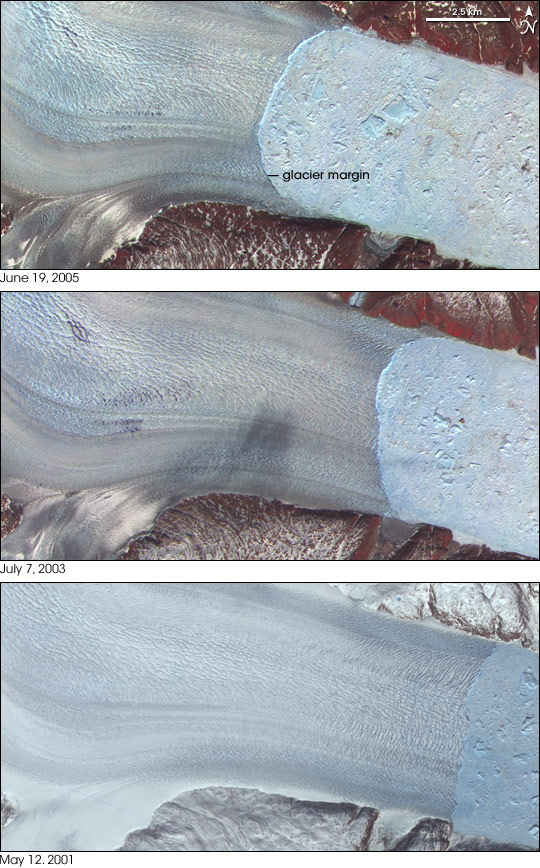

Measurements

Methods for measuring retreat include staking terminus location,global positioning

The Global Positioning System (GPS), originally Navstar GPS, is a satellite-based radionavigation system owned by the United States government and operated by the United States Space Force. It is one of the global navigation satellite sy ...

mapping, aerial mapping and laser altimetry

An altimeter or an altitude meter is an instrument used to measure the altitude of an object above a fixed level. The measurement of altitude is called altimetry, which is related to the term bathymetry, the measurement of depth under water. The m ...

. The key symptom of disequilibrium is thinning along the entire length of the glacier. This indicates a diminishment of the accumulation zone. The result is marginal recession of the accumulation zone margin, not just of the terminus. In effect, the glacier no longer has a consistent accumulation zone and without an accumulation zone cannot survive.

Estimated glacial losses

Excluding peripheral glaciers of ice sheets, the total cumulated global glacial losses over the 26 year period from 1993–2018 were likely 5500 gigatons, or 210 gigatons per yr.Effects

Water supply

The continued retreat of glaciers will have a number of different quantitative effects. In areas that are heavily dependent on water runoff from glaciers that melt during the warmer summer months, a continuation of the current retreat will eventually deplete the glacial ice and substantially reduce or eliminate runoff. A reduction in runoff will affect the ability toirrigate

Irrigation (also referred to as watering) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow crops, landscape plants, and lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,000 years and has been develo ...

crops and will reduce summer stream flows necessary to keep dams and reservoirs replenished. This situation is particularly acute for irrigation in South America, where numerous artificial lakes are filled almost exclusively by glacial melt. Central Asian

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the former ...

countries have also been historically dependent on the seasonal glacier melt water for irrigation and drinking supplies. In Norway, the Alps, and the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though ...

of North America, glacier runoff is important for hydropower

Hydropower (from el, ὕδωρ, "water"), also known as water power, is the use of falling or fast-running water to produce electricity or to power machines. This is achieved by converting the gravitational potential or kinetic energy of a wa ...

.

Ecosystems

Many species of freshwater and saltwater plants and animals are dependent on glacier-fed waters to ensure the cold water habitat to which they have adapted. Some species of freshwater fish need cold water to survive and to reproduce, and this is especially true withsalmon

Salmon () is the common name for several commercially important species of euryhaline ray-finned fish from the family Salmonidae, which are native to tributaries of the North Atlantic (genus ''Salmo'') and North Pacific (genus ''Oncorhynchus' ...

and cutthroat trout

The cutthroat trout is a fish species of the family Salmonidae native to cold-water tributaries of the Pacific Ocean, Rocky Mountains, and Great Basin in North America. As a member of the genus ''Oncorhynchus'', it is one of the Pacific trout ...

. Reduced glacial runoff can lead to insufficient stream flow to allow these species to thrive. Alterations to the ocean currents

An ocean current is a continuous, directed movement of sea water generated by a number of forces acting upon the water, including wind, the Coriolis effect, breaking waves, cabbeling, and temperature and salinity differences. Depth contours ...

, due to increased freshwater inputs from glacier melt, and the potential alterations to thermohaline circulation

Thermohaline circulation (THC) is a part of the large-scale ocean circulation that is driven by global density gradients created by surface heat and freshwater fluxes. The adjective ''thermohaline'' derives from '' thermo-'' referring to tempe ...

of the oceans

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth and contains 97% of Earth's water. An ocean can also refer to any of the large bodies of water into which the worl ...

, may affect existing fisheries

Fishery can mean either the enterprise of raising or harvesting fish and other aquatic life; or more commonly, the site where such enterprise takes place ( a.k.a. fishing ground). Commercial fisheries include wild fisheries and fish farms, bot ...

upon which humans depend as well.

Floods

One major concern is the increased risk ofGlacial Lake Outburst Flood

A glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF) is a type of outburst flood caused by the failure of a dam containing a glacial lake. An event similar to a GLOF, where a body of water contained by a glacier melts or overflows the glacier, is called a jö ...

s (GLOF), which have in the past had great effect on lives and property. Glacier meltwater left behind by the retreating glacier is often held back by moraine

A moraine is any accumulation of unconsolidated debris (regolith and rock), sometimes referred to as glacial till, that occurs in both currently and formerly glaciated regions, and that has been previously carried along by a glacier or ice she ...

s that can be unstable and have been known to collapse if breached or displaced by earthquakes, landslides or avalanches. If the terminal moraine is not strong enough to hold the rising water behind it, it can burst, leading to a massive localized flood. The likelihood of such events is rising due to the creation and expansion of glacial lakes resulting from glacier retreat. Past floods have been deadly and have resulted in enormous property damage. Towns and villages in steep, narrow valleys that are downstream from glacial lakes are at the greatest risk. In 1892 a GLOF released some of water from the lake of the Tête Rousse Glacier

The Tête Rousse Glacier ( French: ''Glacier de Tête Rousse'') is a small but significant glacier located in the Mont Blanc massif within the French Alps whose collapse in 1892 killed 200A contemporary account by J Vallot, cited here, states ...

, resulting in the deaths of 200 people in the French town of Saint-Gervais-les-Bains

Saint-Gervais-les-Bains () is a commune in the Haute-Savoie department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region, southeastern France.

The village is best known for tourism and has been a popular holiday destination since the early 1900s.

It has of p ...

. GLOFs have been known to occur in every region of the world where glaciers are located. Continued glacier retreat is expected to create and expand glacial lakes, increasing the danger of future GLOFs.

Sea level rise

The potential for majorsea level rise

Globally, sea levels are rising due to human-caused climate change. Between 1901 and 2018, the globally averaged sea level rose by , or 1–2 mm per year on average.IPCC, 2019Summary for Policymakers InIPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryo ...

depends mostly on a significant melting of the polar ice caps of Greenland and Antarctica, as this is where the vast majority of glacial ice is located. If all the ice on the polar ice caps were to melt away, the oceans of the world would rise an estimated . Although previously it was thought that the polar ice caps were not contributing heavily to sea level rise (IPCC 2007), recent studies have confirmed that both Antarctica and Greenland are contributing a year each to global sea level rise. The Thwaites Glacier

Thwaites Glacier, nicknamed the Doomsday Glacier, is an unusually broad and vast Antarctic glacier flowing into Pine Island Bay, part of the Amundsen Sea, east of Mount Murphy, on the Walgreen Coast of Marie Byrd Land. Its surface speeds exc ...

alone, in Western Antarctica is "currently responsible for approximately 4 percent of global sea level rise. It holds enough ice to raise the world ocean a little over 2 feet (65 centimeters) and backstops neighboring glaciers that would raise sea levels an additional 8 feet (2.4 meters) if all the ice were lost." The fact that the IPCC estimates did not include rapid ice sheet decay into their sea level predictions makes it difficult to ascertain a plausible estimate for sea level rise but a 2008 study found that the minimum sea level rise will be around by 2100.

Management approaches

To retard melting of the glaciers used by certain Austrian ski resorts, portions of the Stubai and Pitztal Glaciers were partially covered with plastic. In Switzerland plastic sheeting is also used to reduce the melt of glacial ice used as ski slopes. While covering glaciers with plastic sheeting may prove advantageous to ski resorts on a small scale, this practice is not expected to be economically practical on a much larger scale.Middle latitude

Middle latitude

The middle latitudes (also called the mid-latitudes, sometimes midlatitudes, or moderate latitudes) are a spatial region on Earth located between the Tropic of Cancer (latitudes 23°26'22") to the Arctic Circle (66°33'39"), and Tropic of Caprico ...

glaciers are located either between the Tropic of Cancer

The Tropic of Cancer, which is also referred to as the Northern Tropic, is the most northerly circle of latitude on Earth at which the Sun can be directly overhead. This occurs on the June solstice, when the Northern Hemisphere is tilted toward ...

and the Arctic Circle

The Arctic Circle is one of the two polar circles, and the most northerly of the five major circles of latitude as shown on maps of Earth. Its southern equivalent is the Antarctic Circle.

The Arctic Circle marks the southernmost latitude at wh ...

, or between the Tropic of Capricorn

The Tropic of Capricorn (or the Southern Tropic) is the circle of latitude that contains the subsolar point at the December (or southern) solstice. It is thus the southernmost latitude where the Sun can be seen directly overhead. It also reach ...

and the Antarctic Circle

The Antarctic Circle is the most southerly of the five major circles of latitude that mark maps of Earth. The region south of this circle is known as the Antarctic, and the zone immediately to the north is called the Southern Temperate Zone. S ...

. Both areas support glacier ice from mountain glaciers, valley glaciers and even smaller icecaps, which are usually located in higher mountainous regions. All are located in mountain ranges, notably the Himalayas

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 100 ...

; the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Sw ...

; the Pyrenees; Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

; the Caucasus and Pacific Coast Ranges of North America; the Patagonia

Patagonia () refers to a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and ...

n Andes in South America; and mountain ranges in New Zealand. Glaciers in these latitudes are more widespread and tend to be greater in mass the closer they are to the polar regions. They are the most widely studied over the past 150 years. As with examples located in the tropical zone, virtually all the glaciers in the mid-latitudes are in a state of negative mass balance and are retreating.

Northern hemisphere – Eurasia

Europe

In the French alps, all the glaciers there are retreating. OnMont Blanc

Mont Blanc (french: Mont Blanc ; it, Monte Bianco , both meaning "white mountain") is the highest mountain in the Alps and Western Europe, rising above sea level. It is the second-most prominent mountain in Europe, after Mount Elbrus, and it ...

, the highest peak in the Alps, the Argentière Glacier

The Argentière Glacier is a glacier in the French Alps. It is one of the larger glaciers found within the Mont Blanc massif, and is situated above the village of Argentière. It lies perpendicular to the Chamonix valley and falls within the Auve ...

has receded since 1870. Other Mont Blanc glaciers have also been in retreat, including the Mer de Glace

The Mer de Glace ("Sea of Ice") is a valley glacier located on the northern slopes of the Mont Blanc massif, in the French Alps. It is 7.5 km long and deep but, when all its tributary glaciers are taken into account, it can be regarded as ...

, which is the largest glacier in France at in length but retreated between 1994 and 2008. The glacier has retreated since the end of the Little Ice Age. The Argentière and Mer de Glace glaciers are expected to disappear completely by end of the 21st century if current climate trends persist. The Bossons Glacier

The Bossons Glacier is one of the larger glaciers of the Mont Blanc massif of the Alps, found in the Chamonix valley of Haute-Savoie ''département'', south-eastern France. It is fed from icefields lying on the northern side of Mont Blanc, ...

once extended from the summit of Mont Blanc at to an elevation of in 1900. By 2008 Bossons Glacier had retreated to a point that was above sea level.

Other researchers have found that glaciers across the Alps appear to be retreating at a faster rate than a few decades ago. In a paper published in 2009 by the University of Zurich, the Swiss glacier survey of 89 glaciers found 76 retreating, 5 stationary and 8 advancing from where they had been in 1973. The Trift Glacier

The Trift Glacier (german: Triftgletscher) is a long glacier (2005) in the Urner Alps near Gadmen, in the extreme east of the canton Berne in Switzerland.

Morphology

In 1973 glacier was 5.75 km long, 3 km wide at the top and around 500 m w ...

had the greatest recorded retreat, losing of its length between the years 2003 and 2005. The Grosser Aletsch Glacier

The Aletsch Glacier (german: Aletschgletscher, ) or Great Aletsch Glacier () is the largest glacier in the Alps. It has a length of about (2014), has about a volume of (2011), and covers about (2011) in the eastern Bernese Alps in the Swiss can ...

is the largest glacier in Switzerland and has been studied since the late 19th century. Aletsch Glacier retreated from 1880 to 2009. This rate of retreat has also increased since 1980, with 30%, or , of the total retreat occurring in the last 20% of the time period.

The Morteratsch Glacier

The Morteratsch Glacier (Romansh: Vadret da Morteratsch) is the largest glacier by area in the Bernina Range of the Bündner Alps in Switzerland.

By area and by volume (1.2 km3), it is the third largerst glacier in the eastern alps, after th ...

in Switzerland has had one of the longest periods of scientific study with yearly measurements of the glacier's length commencing in 1878. The overall retreat from 1878 to 1998 has been with a mean annual retreat rate of approximately per year. This long-term average was markedly surpassed in recent years with the glacier receding per year during the period between 1999 and 2005. Similarly, of the glaciers in the Italian Alps, only about a third were in retreat in 1980, while by 1999, 89% of these glaciers were retreating. In 2005, the Italian Glacier Commission found that 123 glaciers in Lombardy were retreating. A random study of the Sforzellina Glacier in the Italian Alps indicated that the rate of retreat from 2002 to 2006 was much higher than in the preceding 35 years. To study glaciers located in the alpine regions of Lombardy, researchers compared a series of aerial and ground images taken from the 1950s through the early 21st century and deduced that between the years 1954–2003 the mostly smaller glaciers found there lost more than half of their area. Repeat photography of glaciers in the Alps indicates that there has been significant retreat since studies commenced.

Research, published in 2019 by ETH Zurich, says that two-thirds of the ice in the glaciers of the Alps is doomed to melt by the end of the century due to climate change. In the most pessimistic scenario, the Alps will be almost completely ice-free by 2100, with only isolated ice patches remaining at high elevation.

Though the glaciers of the Alps have received more attention from glaciologists than in other areas of Europe, research indicates that glaciers in northern Europe are also retreating. Since the end of World War II,

Though the glaciers of the Alps have received more attention from glaciologists than in other areas of Europe, research indicates that glaciers in northern Europe are also retreating. Since the end of World War II, Storglaciären

Storglaciären (Swedish for ''The Great Glacier'') is a glacier in Tarfala Valley in the Scandinavian Alps of Kiruna Municipality, Sweden. The glacier is classified as polythermal having both cold and warm bottom temperatures. It was on Storglac ...

in Sweden has undergone the longest continuous mass balance study in the world conducted from the Tarfala research station. In the Kebnekaise

Kebnekaise (; from Sami or , "Cauldron Crest") is the highest mountain in Sweden. The Kebnekaise massif, which is part of the Scandinavian mountain range, has two main peaks. The glaciated southern peak used to be the highest at above sea level ...

Mountains of northern Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

, a study of 16 glaciers between 1990 and 2001 found that 14 glaciers were retreating, one was advancing and one was stable. In Norway, glacier studies have been performed since the early 19th century, with systematic surveys undertaken regularly since the 1990s. Inland glaciers have had a generally negative mass balance, whereby during the 1990s, maritime glaciers showed a positive mass balance and advanced. The maritime advances have been attributed to heavy snowfall in the period 1989–1995. However, reduced snowfall since has caused most Norwegian glaciers to retreat significantly. A survey of 31 Norwegian glaciers in 2010 indicated that 27 were in retreat, one had no change and three advanced. Similarly, in 2013, of 33 Norwegian glaciers surveyed, 26 were retreating, four showed no change and three advanced.

Engabreen Glacier in Norway, an outlet glacier of the Svartisen ice cap, had several advances in the 20th century, though it retreated between 1999 and 2014. Brenndalsbreen glacier retreated between the years 2000 and 2014, while the Rembesdalsskåka glacier, which has retreated since the end of the Little Ice Age, retreated between 1997 and 2007. The Briksdalsbreen glacier retreated between 1996 and 2004 with of that in the last year of that study; the greatest annual retreat recorded on that glacier since studies began there in 1900. This figure was exceeded in 2006 with five glaciers retreating over from the fall of 2005 to the fall of 2006. Four outlets from the Jostedalsbreen

Jostedal Glacier or is the largest glacier in continental Europe. It is in Vestland county in Western Norway. Jostedalsbreen lies in the municipalities of Luster, Sogndal, Sunnfjord, and Stryn. The highest peak in the area is Lodalskåpa at ...

ice cap, the largest body of ice in continental Europe, Kjenndalsbreen

Kjenndalsbreen is a glacier in the municipality of Stryn in Vestland, Norway. The glacier is a side branch of the Jostedalsbreen glacier, and is included in the Jostedalsbreen National Park.

See also

*List of glaciers in Norway

These are th ...

, Brenndalsbreen, Briksdalsbreen

Briksdalsbreen ( en, the Briksdal glacier) is one of the most accessible and best known arms of the Jostedalsbreen glacier. Briksdalsbreen is located in the municipality of Stryn in Vestland county, Norway. The glacier lies on the north side of ...

and Bergsetbreen had a frontal retreat of more than . Overall, from 1999 to 2005, Briksdalsbreen retreated . Gråfjellsbrea, an outlet glacier of the Folgefonna ice cap, had a retreat of almost .

Maladeta

Maladeta (3,312 m) is a mountain in the Pyrenees, close to the highest peak in the range, Aneto. It is located in the Natural Park of Posets-Maladeta in the town of Benasque in Province of Huesca, Aragon, Spain. Its northern slope contains the ...

massif during the period 1981–2005. These include a reduction in area of 35.7%, from to , a loss in total ice volume of and an increase in the mean altitude of the glacial termini of . For the Pyrenees as a whole 50–60% of the glaciated area has been lost since 1991. The Balaitus, Perdigurero and La Munia glaciers have disappeared in this period. Monte Perdido Glacier has shrunk from 90 hectares to 40 hectares.

As initial cause for glacier retreat in the alps since 1850, a decrease of the glaciers' albedo

Albedo (; ) is the measure of the diffuse reflection of sunlight, solar radiation out of the total solar radiation and measured on a scale from 0, corresponding to a black body that absorbs all incident radiation, to 1, corresponding to a body ...

, caused by industrial black carbon

Chemically, black carbon (BC) is a component of fine particulate matter (PM ≤ 2.5 µm in aerodynamic diameter). Black carbon consists of pure carbon in several linked forms. It is formed through the incomplete combustion of fossil fuel ...

can be identified. According to a report, this may have accelerated the retreat of glaciers in Europe which otherwise might have continued to expand until approximately the year 1910.

West Asia

All the glaciers in Turkey are in retreat and glaciers have been developing proglacial lakes at their terminal ends as the glaciers thin and retreat. Between the 1970s and 2013, the glaciers in Turkey lost half their area, going from in the 1970s to in 2013. Of the 14 glaciers studied, five had disappeared altogether.Mount Ararat

Mount Ararat or , ''Ararat''; or is a snow-capped and dormant compound volcano in the extreme east of Turkey. It consists of two major volcanic cones: Greater Ararat and Little Ararat. Greater Ararat is the highest peak in Turkey and t ...

has the largest glacier in Turkey, and that is forecast to be completely gone by 2065.

Siberia and the Russian Far East

Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

is typically classified as a polar region, owing to the dryness of the winter climate and has glaciers only in the high Altai Mountains

The Altai Mountains (), also spelled Altay Mountains, are a mountain range in Central and East Asia, where Russia, China, Mongolia and Kazakhstan converge, and where the rivers Irtysh and Ob have their headwaters. The massif merges with the ...

, Verkhoyansk Range

The Verkhoyansk Range (russian: Верхоянский хребет, ''Verkhojanskiy Khrebet''; sah, Үөһээ Дьааҥы сис хайата, ''Üöhee Chaangy sis khaĭata'') is a mountain range in the Sakha Republic, Russia near the settl ...

, Cherskiy Range and Suntar-Khayata Range

Suntar-Khayata Range (russian: Сунтар-Хаята, sah, Сунтаар Хайата) is a granite mountain range rising along the border of the Sakha Republic in the north with Amur Oblast and Khabarovsk Krai in the south.

The R504 Koly ...

, plus possibly a few very small glaciers in the ranges near Lake Baikal

Lake Baikal (, russian: Oзеро Байкал, Ozero Baykal ); mn, Байгал нуур, Baigal nuur) is a rift lake in Russia. It is situated in southern Siberia, between the federal subjects of Irkutsk Oblast to the northwest and the Rep ...

, which have never been monitored and may have completely disappeared since 1989. Between the years 1952 and 2006, the glaciers found in the Aktru Basin region shrank by 7.2 percent. This shrinkage has been primarily in the ablation zone of the glaciers, with recession of several hundred meters being observed for some glaciers. The Altai region has also experienced an overall temperature increase of 1.2 degrees Celsius in the last 120 years according to a report from 2006, with most of that increase occurring since the late 20th century.

In the more maritime and generally wetter Russian Far East

The Russian Far East (russian: Дальний Восток России, r=Dal'niy Vostok Rossii, p=ˈdalʲnʲɪj vɐˈstok rɐˈsʲiɪ) is a region in Northeast Asia. It is the easternmost part of Russia and the Asian continent; and is admin ...

, Kamchatka

The Kamchatka Peninsula (russian: полуостров Камчатка, Poluostrov Kamchatka, ) is a peninsula in the Russian Far East, with an area of about . The Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Okhotsk make up the peninsula's eastern and west ...

, exposed during winter to moisture from the Aleutian Low

The Aleutian Low is a semi-permanent low-pressure system located near the Aleutian Islands in the Bering Sea during the Northern Hemisphere winter. It is a climatic feature centered near the Aleutian Islands measured based on mean sea-level press ...

, has much more extensive glaciation totaling around with 448 known glaciers as of 2010. Despite generally heavy winter snowfall and cool summer temperatures, the high summer rainfall of the more southerly Kuril Islands

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands (; rus, Кури́льские острова́, r=Kuril'skiye ostrova, p=kʊˈrʲilʲskʲɪjə ɐstrɐˈva; Japanese: or ) are a volcanic archipelago currently administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast in the ...

and Sakhalin

Sakhalin ( rus, Сахали́н, r=Sakhalín, p=səxɐˈlʲin; ja, 樺太 ''Karafuto''; zh, c=, p=Kùyèdǎo, s=库页岛, t=庫頁島; Manchu: ᠰᠠᡥᠠᠯᡳᠶᠠᠨ, ''Sahaliyan''; Orok: Бугата на̄, ''Bugata nā''; Nivkh: ...

in historic times melt rates have been too high for a positive mass balance even on the highest peaks. In the Chukotskiy Peninsula small alpine glaciers are numerous, but the extent of glaciation, though larger than further west, is much smaller than in Kamchatka, totaling around .

Details on the retreat of Siberian and Russian Far East glaciers have been less adequate than in most other glaciated areas of the world. There are several reasons for this, the principal one being that since the collapse of Communism there has been a large reduction in the number of monitoring stations. Another factor is that in the Verkhoyansk and Cherskiy Ranges it was thought glaciers were absent before they were discovered during the 1940s, whilst in ultra-remote Kamchatka and Chukotka, although the existence of glaciers was known earlier, monitoring of their size dates back no earlier than the end of World War II. Nonetheless, available records do indicate a general retreat of all glaciers in the Altai Mountains with the exception of volcanic glaciers in Kamchatka. Sakha's glaciers, totaling seventy square kilometers, have shrunk by around 28 percent since 1945 reaching several percent annually in some places, whilst in the Altai and Chukotkan mountains and non-volcanic areas of Kamchatka, the shrinkage is considerably larger.

Himalayas and Central Asia

The Himalayas and other mountain chains of central Asia support large glaciated regions. An estimated 15,000 glaciers can be found in the greater Himalayas, with double that number in the Hindu Kush and Karakoram and Tien Shan ranges, and comprise the largest glaciated region outside the poles. These glaciers provide critical water supplies to arid countries such as

The Himalayas and other mountain chains of central Asia support large glaciated regions. An estimated 15,000 glaciers can be found in the greater Himalayas, with double that number in the Hindu Kush and Karakoram and Tien Shan ranges, and comprise the largest glaciated region outside the poles. These glaciers provide critical water supplies to arid countries such as Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; literal translation, lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia Mongolia–Russia border, to the north and China China–Mongolia border, to the s ...

, western China, Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

, Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

and India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

. As with glaciers worldwide, those of the greater Himalayan region are experiencing a decline in mass, and researchers claim that between the early 1970s and early 2000s, there had been a 9 percent reduction in ice mass, while there has been a significant increase in mass loss since the Little Ice Age

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of regional cooling, particularly pronounced in the North Atlantic region. It was not a true ice age of global extent. The term was introduced into scientific literature by François E. Matthes in 1939. Ma ...

with a 10-fold increase when compared to rates seen currently. Change in temperature has led to melting and the formation and expansion of glacial lakes which could cause an increase in the number of glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs). If the present trends persist the ice mass will gradually be reduced, and will affect the availability of water resources, though water loss is not expected to cause problems for many decades.

In the Wakhan Corridor of Afghanistan 28 of 30 glaciers examined retreated significantly between 1976 and 2003, with an average retreat of per year. One of these glaciers, the Zemestan Glacier, retreated during this period, not quite 10% of its length. In examining 612 glaciers in China between 1950 and 1970, 53% of the glaciers studied were retreating. After 1990, 95% of these glaciers were measured to be retreating, indicating that retreat of these glaciers was becoming more widespread. Glaciers in the Mount Everest

Mount Everest (; Tibetan: ''Chomolungma'' ; ) is Earth's highest mountain above sea level, located in the Mahalangur Himal sub-range of the Himalayas. The China–Nepal border runs across its summit point. Its elevation (snow heig ...

region of the Himalayas are all in a state of retreat. The Rongbuk Glacier

The Rongbuk Glacier () is located in the Himalaya of southern Tibet. Two large tributary glaciers, the East Rongbuk Glacier and the West Rongbuk Glacier, flow into the main Rongbuk Glacier. It flows north and forms the Rongbuk Valley north of Moun ...

, draining the north side of Mount Everest into Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa, Taman ...

, has been retreating per year. In the Khumbu region of Nepal along the front of the main Himalaya of 15 glaciers examined from 1976 to 2007 all retreated significantly and the average retreat was per year. The most famous of these, the Khumbu Glacier, retreated at a rate of per year from 1976 to 2007. In India, the Gangotri Glacier

Gangotri (Sanskrit and hi, गंगोत्री) is located in Uttarkashi District, Uttarakhand, India in a region bordering Tibet. This glacier, one of the primary sources of the Ganges, has a volume of over 27 cubic kilometers. The glacie ...

retreated between the years 1936 and 1996 with of that retreat occurring in the last 25 years of the 20th century. However, the glacier is still over long. In Sikkim

Sikkim (; ) is a state in Northeastern India. It borders the Tibet Autonomous Region of China in the north and northeast, Bhutan in the east, Province No. 1 of Nepal in the west and West Bengal in the south. Sikkim is also close to the Siligur ...

, 26 glaciers examined between the years 1976 and 2005 were retreating at an average rate of per year.

Overall, glaciers in the Greater Himalayan region that have been studied are retreating an average of between annually. The only region in the Greater Himalaya that has seen glacial advances is in the Karakoram Range

The Karakoram is a mountain range in Kashmir region spanning the borders of Pakistan, China, and India, with the northwest extremity of the range extending to Afghanistan and Tajikistan. Most of the Karakoram mountain range falls under the ...

and only in the highest elevation glaciers, but this has been attributed possibly increased precipitation as well as to the correlating glacial surges, where the glacier tongue advances due to pressure build up from snow and ice accumulation further up the glacier. Between the years 1997 and 2001, long Biafo Glacier

The Biafo Glacier ( ur, ) is a -long glacier situated in the Karakoram mountain range in Shigar district, Gilgit−Baltistan, Pakistan. Geography

Biafo Glacier meets the -long Hispar Glacier at an altitude of at Hispar La to create the wor ...

thickened mid-glacier, however it did not advance.

With the retreat of glaciers in the Himalayas, a number of glacial lakes have been created. A growing concern is the potential for

With the retreat of glaciers in the Himalayas, a number of glacial lakes have been created. A growing concern is the potential for GLOF

A glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF) is a type of outburst flood caused by the failure of a dam containing a glacial lake. An event similar to a GLOF, where a body of water contained by a glacier melts or overflows the glacier, is called a jö ...

s researchers estimate 21 glacial lakes in Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mai ...

and 24 in Bhutan

Bhutan (; dz, འབྲུག་ཡུལ་, Druk Yul ), officially the Kingdom of Bhutan,), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is situated in the Eastern Himalayas, between China in the north and India in the south. A mountainou ...

pose hazards to human populations should their terminal moraines fail. One glacial lake identified as potentially hazardous is Bhutan's Raphstreng Tsho, which measured long, wide and deep in 1986. By 1995 the lake had swollen to a length of , in width and a depth of . In 1994 a GLOF from Luggye Tsho, a glacial lake adjacent to Raphstreng Tsho, killed 23 people downstream.

Glaciers in the Ak-shirak Range in Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan,, pronounced or the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Asia. Kyrgyzstan is bordered by Kazakhstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the west, Tajikistan to the south, and the People's Republic of China to the east ...

experienced a slight loss between 1943 and 1977 and an accelerated loss of 20% of their remaining mass between 1977 and 2001. In the Tien Shan

The Tian Shan,, , otk, 𐰴𐰣 𐱅𐰭𐰼𐰃, , tr, Tanrı Dağı, mn, Тэнгэр уул, , ug, تەڭرىتاغ, , , kk, Тәңіртауы / Алатау, , , ky, Теңир-Тоо / Ала-Тоо, , , uz, Tyan-Shan / Tangritog‘ ...

mountains, which Kyrgyzstan shares with China and Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbekis ...

, studies in the northern areas of that mountain range show that the glaciers that help supply water to this arid region, lost nearly of ice per year between 1955 and 2000. The University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

study also reported that an average of 1.28% of the volume of these glaciers had been lost per year between 1974 and 1990.

The Pamirs

The Pamir Mountains are a mountain range between Central Asia and Pakistan. It is located at a junction with other notable mountains, namely the Tian Shan, Karakoram, Kunlun, Hindu Kush and the Himalaya mountain ranges. They are among the world' ...

mountain range located primarily in Tajikistan

Tajikistan (, ; tg, Тоҷикистон, Tojikiston; russian: Таджикистан, Tadzhikistan), officially the Republic of Tajikistan ( tg, Ҷумҳурии Тоҷикистон, Jumhurii Tojikiston), is a landlocked country in Centr ...

, has approximately eight thousand glaciers, many of which are in a general state of retreat. During the 20th century, the glaciers of Tajikistan lost of ice. The long Fedchenko Glacier

The Fedchenko Glacier (russian: Ледник Федченко; tg, Пиряхи Федченко) is a large glacier in the Yazgulem Range, Pamir Mountains, of north-central Gorno-Badakhshan province, Tajikistan. The glacier is long and narrow, ...

, which is the largest in Tajikistan and the largest non-polar glacier on Earth, retreated between the years 1933 and 2006, and lost of its surface area due to shrinkage between the years 1966 and 2000. Tajikistan and neighboring countries of the Pamir Range are highly dependent upon glacial runoff to ensure river flow during droughts and the dry seasons experienced every year. The continued demise of glacier ice will result in a short-term increase, followed by a long-term decrease in glacial melt water flowing into rivers and streams.

Northern hemisphere – North America

North American glaciers are primarily located along the spine of the Rocky Mountains in the United States and Canada, and the Pacific Coast Ranges extending from northern California to

North American glaciers are primarily located along the spine of the Rocky Mountains in the United States and Canada, and the Pacific Coast Ranges extending from northern California to Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

. While Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is ...

is geologically associated with North America, it is also a part of the Arctic region. Apart from the few tidewater glaciers such as Taku Glacier

Taku Glacier ( Lingít: ''T'aaḵú Ḵwáan Sít'i'') is a tidewater glacier located in Taku Inlet in the U.S. state of Alaska, just southeast of the city of Juneau. Recognized as the deepest and thickest alpine temperate glacier known in the w ...

, in the advance stage of their tidewater glacier cycle

The tidewater glacier cycle is the typically centuries-long behavior of tidewater glaciers that consists of recurring periods of advance alternating with rapid retreat and punctuated by periods of stability. During portions of its cycle, a tidewate ...

prevalent along the coast of Alaska, virtually all of those in North America are in a state of retreat. This rate has increased rapidly since around 1980, and overall each decade since has seen greater rates of retreat than the preceding one. There are also small remnant glaciers scattered throughout the Sierra Nevada

The Sierra Nevada () is a mountain range in the Western United States, between the Central Valley of California and the Great Basin. The vast majority of the range lies in the state of California, although the Carson Range spur lies primarily ...

mountains of California and Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a state in the Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the 7th-most extensive, ...

.

Cascade Range

TheCascade Range

The Cascade Range or Cascades is a major mountain range of western North America, extending from southern British Columbia through Washington and Oregon to Northern California. It includes both non-volcanic mountains, such as the North Cascades, ...

of western North America extends from southern British Columbia in Canada to northern California. Excepting Alaska, about half of the glacial area in the U.S. is contained within the over 700 glaciers of the North Cascades

The North Cascades are a section of the Cascade Range of western North America. They span the border between the Canadian province of British Columbia and the U.S. state of Washington and are officially named in the U.S. and Canada as the Cas ...

, a portion of those located between the Canada–US border and I-90

Interstate 90 (I-90) is an east–west transcontinental freeway and the longest Interstate Highway in the United States at . It begins in Seattle, Washington, and travels through the Pacific Northwest, Mountain West, Great Plains, Midwest, an ...

in central Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

. These contain as much water as is found in all the lakes and reservoirs in the rest of the state, and provide much of the stream and river flow in the dry summer months, approximating some .

As recently as 1975 many North Cascade glaciers were advancing due to cooler weather and increased precipitation that occurred from 1944 to 1976. By 1987 the North Cascade glaciers were retreating and the pace had increased each decade since the mid-1970s. Between 1984 and 2005 the North Cascade glaciers lost an average of more than in thickness and 20–40 percent of their volume.

Glaciologists researching the North Cascades found that all 47 monitored glaciers are receding while four glaciers— Spider Glacier, Lewis Glacier, Milk Lake Glacier and

As recently as 1975 many North Cascade glaciers were advancing due to cooler weather and increased precipitation that occurred from 1944 to 1976. By 1987 the North Cascade glaciers were retreating and the pace had increased each decade since the mid-1970s. Between 1984 and 2005 the North Cascade glaciers lost an average of more than in thickness and 20–40 percent of their volume.

Glaciologists researching the North Cascades found that all 47 monitored glaciers are receding while four glaciers— Spider Glacier, Lewis Glacier, Milk Lake Glacier and David Glacier

David Glacier is the most imposing outlet glacier in Victoria Land, Antarctica. It is named after the geologist Edgeworth David and is fed by two main flows which drain an area larger than 200,000 square kilometres of the East Antarctic platea ...

—are almost completely gone. The White Chuck Glacier

White Chuck Glacier is located in the Glacier Peak Wilderness in the U.S. state of Washington and is south of Glacier Peak. The glacier is within Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest and nearly touches the White River Glacier though they are se ...

(near Glacier Peak

Glacier Peak or Dakobed (known in the Sauk-Suiattle dialect of the Lushootseed language as "Tda-ko-buh-ba" or "Takobia") is the most isolated of the five major stratovolcanoes (composite volcanoes) of the Cascade Volcanic Arc in the U.S state o ...

) is a particularly dramatic example. The glacier area shrank from in 1958 to by 2002. Between 1850 and 1950, the Boulder Glacier on the southeast flank of Mount Baker

Mount Baker (Lummi: '; nok, Kw’eq Smaenit or '), also known as Koma Kulshan or simply Kulshan, is a active glacier-covered andesitic stratovolcano in the Cascade Volcanic Arc and the North Cascades of Washington in the United States. Moun ...

retreated . William Long of the United States Forest Service observed the glacier beginning to advance due to cooler/wetter weather in 1953. This was followed by a advance by 1979. The glacier again retreated from 1987 to 2005, leaving barren terrain behind. This retreat has occurred during a period of reduced winter snowfall and higher summer temperatures. In this region of the Cascades, winter snowpack

Snowpack forms from layers of snow that accumulate in geographic regions and high elevations where the climate includes cold weather for extended periods during the year. Snowpacks are an important water resource that feed streams and rivers as th ...

has declined 25% since 1946, and summer temperatures have risen 0.7 °C

The degree Celsius is the unit of temperature on the Celsius scale (originally known as the centigrade scale outside Sweden), one of two temperature scales used in the International System of Units (SI), the other being the Kelvin scale. The d ...

(1.2 °F

The Fahrenheit scale () is a temperature scale based on one proposed in 1724 by the physicist Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit (1686–1736). It uses the degree Fahrenheit (symbol: °F) as the unit. Several accounts of how he originally defined hi ...

) during the same period. The reduced snowpack has occurred despite a small increase in winter precipitation—thus, it reflects warmer winter temperatures leading to rainfall and melting on glaciers even during the winter. As of 2005, 67% of the North Cascade glaciers observed are in disequilibrium and will not survive the continuation of the present climate. These glaciers will eventually disappear unless temperatures fall and frozen precipitation increases. The remaining glaciers are expected to stabilize, unless the climate continues to warm, but will be much reduced in size.

U.S. Rocky Mountains

On the sheltered slopes of the highest peaks of Glacier National Park inMontana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Colum ...

, the eponymous

An eponym is a person, a place, or a thing after whom or which someone or something is, or is believed to be, named. The adjectives which are derived from the word eponym include ''eponymous'' and ''eponymic''.

Usage of the word

The term ''epon ...

glaciers are diminishing rapidly. The area of each glacier has been mapped for decades by the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational propertie ...

and the U.S. Geological Survey. Comparing photographs from the mid-19th century with contemporary images provides ample evidence that they have retreated notably since 1850. Repeat photography since clearly show that glaciers such as Grinnell Glacier

Grinnell Glacier is in the heart of Glacier National Park in the U.S. state of Montana. The glacier is named for George Bird Grinnell, an early American conservationist and explorer, who was also a strong advocate of ensuring the creation of Glac ...

are all retreating. The larger glaciers are now approximately a third of their former size when first studied in 1850, and numerous smaller glaciers have disappeared completely. Only 27% of the area of Glacier National Park covered by glaciers in 1850 remained covered by 1993. Researchers believe that between the year 2030 and 2080, that some glacial ice in Glacier National Park will be gone unless current climate patterns reverse their course. Grinnell Glacier is just one of many glaciers in Glacier National Park that have been well documented by photographs for many decades. The photographs below clearly demonstrate the retreat of this glacier since 1938.

T.J. Hileman T. J. (Tomar Jacob) Hileman (1882–1945) was an American photographer born in Manor Township, Armstrong County Pennsylvania, who is renowned for his photos of Glacier Park in Montana, and Blackfoot people.

After working a while in Chicago and gr ...

GNP''

File:Grinnell Glacier 1981.jpg, 1981 ''Carl Key (USGS)''

File:Grinnell Glacier 1998.jpg, 1998 ''Dan Fagre (USGS)''

File:Grinnell Glacier 2009.jpg, 2009 ''Lindsey Bengtson (USGS)''

Grand Teton National Park

Grand Teton National Park is an American national park in northwestern Wyoming. At approximately , the park includes the major peaks of the Teton Range as well as most of the northern sections of the valley known as Jackson Hole. Grand Teton N ...

, which all show evidence of retreat over the past 50 years. Schoolroom Glacier

Schoolroom Glacier is a small glacier in Grand Teton National Park in the U.S. state of Wyoming. This Teton Range glacier lies adjacent to the south Cascade Canyon trail at an altitude of , approximately from the trailhead at Jenny Lake. The ...

is located slightly southwest of Grand Teton

Grand Teton is the highest mountain in Grand Teton National Park, in Northwest Wyoming, and a classic destination in American mountaineering.

Geography

Grand Teton, at , is the highest point of the Teton Range, and the second highest peak in ...

is one of the more easily reached glaciers in the park and it is expected to disappear by 2025. Research between 1950 and 1999 demonstrated that the glaciers in Bridger-Teton National Forest and Shoshone National Forest

Shoshone National Forest ( ) is the first federally protected National Forest in the United States and covers nearly in the state of Wyoming. Originally a part of the Yellowstone Timberland Reserve, the forest is managed by the United State ...

in the Wind River Range

The Wind River Range (or "Winds" for short) is a mountain range of the Rocky Mountains in western Wyoming in the United States. The range runs roughly NW–SE for approximately . The Continental Divide follows the crest of the range and inclu ...

shrank by over a third of their size during that period. Photographs indicate that the glaciers today are only half the size as when first photographed in the late 1890s. Research also indicates that the glacial retreat was proportionately greater in the 1990s than in any other decade over the last 100 years. Gannett Glacier

Gannett Glacier is the largest glacier in the Rocky Mountains within the United States. The glacier is located on the east and north slopes of Gannett Peak, the highest mountain in Wyoming, on the east side of the Continental Divide in the Wind R ...

on the northeast slope of Gannett Peak

Gannett Peak is the highest mountain peak in the U.S. state of Wyoming at . It lies in the Wind River Range within the Bridger Wilderness of the Bridger-Teton National Forest. Straddling the Continental Divide along the boundary between Fremo ...

is the largest single glacier in the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

south of Canada. It has reportedly lost over 50% of its volume since 1920, with almost half of that loss occurring since 1980. Glaciologists believe the remaining glaciers in Wyoming will disappear by the middle of the 21st century if the current climate patterns continue.

Canadian Rockies and Coast and Columbia Mountains

In the

In the Canadian Rockies

The Canadian Rockies (french: Rocheuses canadiennes) or Canadian Rocky Mountains, comprising both the Alberta Rockies and the British Columbian Rockies, is the Canadian segment of the North American Rocky Mountains. It is the easternmost part ...

, glaciers are generally larger and more widespread than to the south in the Rocky Mountains. One of the more accessible in the Canadian Rockies is the Athabasca Glacier

The Athabasca Glacier is one of the six principal 'toes' of the Columbia Icefield, located in the Canadian Rockies. The glacier currently loses depth at a rate of about per year and has receded more than and lost over half of its volume in ...

, which is an outlet glacier of the Columbia Icefield

The Columbia Icefield is the largest ice field in North America's Rocky Mountains. Located within the Canadian Rocky Mountains astride the Continental Divide along the border of British Columbia and Alberta, Canada, the ice field lies partly i ...

. The Athabasca Glacier has retreated since the late 19th century. Its rate of retreat has increased since 1980, following a period of slow retreat from 1950 to 1980. The Peyto Glacier

__NOTOC__

The Peyto Glacier is situated in the Canadian Rockies in Banff National Park, Alberta, Canada, approximately northwest of the town of Banff, and can be accessed from the Icefields Parkway. Geography

Peyto Glacier is an outflow glac ...

in Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest Terri ...

covers an area of about , and retreated rapidly during the first half of the 20th century, stabilized by 1966, and resumed shrinking in 1976.

The Illecillewaet Glacier in British Columbia's Glacier National Park (Canada)

Glacier National Park is part of a system of 43 parks and park reserves across Canada, and one of seven national parks in British Columbia. Established in 1886, the park encompasses , and includes a portion of the Selkirk Mountains which are pa ...

, part of the Selkirk Mountains

The Selkirk Mountains are a mountain range spanning the northern portion of the Idaho Panhandle, eastern Washington, and southeastern British Columbia which are part of a larger grouping of mountains, the Columbia Mountains. They begin at Mica ...

(west of the Rockies) has retreated since first photographed in 1887.

In Garibaldi Provincial Park

Garibaldi Provincial Park, also called Garibaldi Park, is a wilderness park located on the coastal mainland of British Columbia, Canada, 70 kilometres (43.5 mi) north of Vancouver. It was established in 1920 and named a Class A Provincial P ...

in Southwestern British Columbia over , or 26%, of the park, was covered by glacier ice at the beginning of the 18th century. Ice cover decreased to by 1987–1988 and to by 2005, 50% of the 1850 area. The loss in the last 20 years coincides with negative mass balance in the region. During this period all nine glaciers examined have retreated significantly.

Alaska

There are thousands of glaciers in Alaska but only few have been named. The Columbia Glacier near Valdez in

There are thousands of glaciers in Alaska but only few have been named. The Columbia Glacier near Valdez in Prince William Sound

Prince William Sound ( Sugpiaq: ''Suungaaciq'') is a sound of the Gulf of Alaska on the south coast of the U.S. state of Alaska. It is located on the east side of the Kenai Peninsula. Its largest port is Valdez, at the southern terminus of the T ...

retreated in the 25 years from 1980 to 2005. Its calved icebergs partially caused the Exxon Valdez

''Oriental Nicety'', formerly ''Exxon Valdez'', ''Exxon Mediterranean'', ''SeaRiver Mediterranean'', ''S/R Mediterranean'', ''Mediterranean'', and ''Dong Fang Ocean'', was an oil tanker that gained notoriety after running aground in Prince Wil ...

oil spill, when the tanker changed course to avoid the ice tips. The Valdez Glacier is in the same area, and though it does not calve, has also retreated significantly. "A 2005 aerial survey of Alaskan coastal glaciers identified more than a dozen glaciers, many former tidewater and calving glaciers, including Grand Plateau, Alsek, Bear, and Excelsior Glaciers that are rapidly retreating. Of 2,000 glaciers observed, 99% are retreating." Icy Bay

Icy Bay (Tlingit: ''Lig̲aasi Áa'') is a body of water in the borough of Yakutat, Alaska, formed in the last 100 years by the rapid retreat of the Guyot, Yahtse, and Tyndall Glaciers. It is part of the Wrangell-Saint Elias Wilderness.

At th ...

in Alaska is fed by three large glaciers—Guyot

In marine geology, a guyot (pronounced ), also known as a tablemount, is an isolated underwater volcanic mountain (seamount) with a flat top more than below the surface of the sea. The diameters of these flat summits can exceed .Yahtse, and Tyndall Glaciers—all of which have experienced a loss in length and thickness and, consequently, a loss in area. Tyndall Glacier became separated from the retreating Guyot Glacier in the 1960s and has retreated since, averaging more than per year.

The Juneau Icefield Research Program has monitored outlet glaciers of the  Long-term mass balance records from Lemon Creek Glacier in Alaska show slightly declining mass balance with time. The mean annual balance for this glacier was − each year during the period of 1957 to 1976. Mean annual balance has been increasingly negatively averaging − per year from 1990 to 2005. Repeat glacier altimetry, or altitude measuring, for 67 Alaska glaciers find rates of thinning have increased by more than a factor of two when comparing the periods from 1950 to 1995 ( per year) and 1995 to 2001 ( per year). This is a systemic trend with loss in mass equating to loss in thickness, which leads to increasing retreat—the glaciers are not only retreating, but they are also becoming much thinner. In

Long-term mass balance records from Lemon Creek Glacier in Alaska show slightly declining mass balance with time. The mean annual balance for this glacier was − each year during the period of 1957 to 1976. Mean annual balance has been increasingly negatively averaging − per year from 1990 to 2005. Repeat glacier altimetry, or altitude measuring, for 67 Alaska glaciers find rates of thinning have increased by more than a factor of two when comparing the periods from 1950 to 1995 ( per year) and 1995 to 2001 ( per year). This is a systemic trend with loss in mass equating to loss in thickness, which leads to increasing retreat—the glaciers are not only retreating, but they are also becoming much thinner. In

A large region of population surrounding the central and southern Andes of

A large region of population surrounding the central and southern Andes of

In New Zealand, mountain glaciers have been in general retreat since 1890, with an acceleration since 1920. Most have measurably thinned and reduced in size, and the snow accumulation zones have risen in elevation as the 20th century progressed. Between 1971 and 1975 Ivory Glacier receded from the glacial terminus, and about 26% of its surface area was lost. Since 1980 numerous small glacial lakes formed behind the new terminal moraines of several of these glaciers. Glaciers such as Classen, Godley and Douglas now all have new glacial lakes below their terminal locations due to the glacial retreat over the past 20 years. Satellite imagery indicates that these lakes are continuing to expand. There has been significant and ongoing ice volume losses on the largest New Zealand glaciers, including the Tasman, Ivory, Classen, Mueller, Maud, Hooker, Grey, Godley, Ramsay, Murchison, Therma, Volta and Douglas Glaciers. The retreat of these glaciers has been marked by expanding proglacial lakes and terminus region thinning. The loss in Southern Alps total ice volume from 1976 to 2014 is 34 percent of the total.

Several glaciers, notably the much-visited

In New Zealand, mountain glaciers have been in general retreat since 1890, with an acceleration since 1920. Most have measurably thinned and reduced in size, and the snow accumulation zones have risen in elevation as the 20th century progressed. Between 1971 and 1975 Ivory Glacier receded from the glacial terminus, and about 26% of its surface area was lost. Since 1980 numerous small glacial lakes formed behind the new terminal moraines of several of these glaciers. Glaciers such as Classen, Godley and Douglas now all have new glacial lakes below their terminal locations due to the glacial retreat over the past 20 years. Satellite imagery indicates that these lakes are continuing to expand. There has been significant and ongoing ice volume losses on the largest New Zealand glaciers, including the Tasman, Ivory, Classen, Mueller, Maud, Hooker, Grey, Godley, Ramsay, Murchison, Therma, Volta and Douglas Glaciers. The retreat of these glaciers has been marked by expanding proglacial lakes and terminus region thinning. The loss in Southern Alps total ice volume from 1976 to 2014 is 34 percent of the total.

Several glaciers, notably the much-visited

Almost all Africa is in

Almost all Africa is in

The

The

In

In