Kulaks on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Kulak (; russian: кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈlak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned over of land towards the end of the Russian Empire. In the early Soviet Union, particularly in Soviet Russia and

Kulak (; russian: кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈlak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned over of land towards the end of the Russian Empire. In the early Soviet Union, particularly in Soviet Russia and

Soviet terminology divided the Russian peasants into three broad categories:

# ''Bednyak'', or poor peasants.

# ''Serednyak'', or mid-income peasants.

# ''Kulak'', the higher-income farmers who had larger farms.

In addition, they had a category of ''batrak'', landless seasonal agricultural workers for hire.

The

Soviet terminology divided the Russian peasants into three broad categories:

# ''Bednyak'', or poor peasants.

# ''Serednyak'', or mid-income peasants.

# ''Kulak'', the higher-income farmers who had larger farms.

In addition, they had a category of ''batrak'', landless seasonal agricultural workers for hire.

The

online free to borrow

* Kaznelson, Michael. 2007. "Remembering the Soviet State: Kulak children and dekulakisation." ''

We'll Meet Again in Heaven

" US:

Kulak (; russian: кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈlak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned over of land towards the end of the Russian Empire. In the early Soviet Union, particularly in Soviet Russia and

Kulak (; russian: кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈlak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned over of land towards the end of the Russian Empire. In the early Soviet Union, particularly in Soviet Russia and Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of t ...

, ''kulak'' became a vague reference to property ownership

Ownership is the state or fact of legal possession and control over property, which may be any asset, tangible or intangible. Ownership can involve multiple rights, collectively referred to as title, which may be separated and held by different ...

among peasants who were considered hesitant allies of the Bolshevik Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

. In Ukraine during 1930–1931, there also existed a term of pidkurkulnyk (almost wealthy peasant); these were considered "sub-kulaks".

''Kulak'' originally referred to former peasants in the Russian Empire who became wealthier during the Stolypin reform

The Stolypin agrarian reforms were a series of changes to Imperial Russia's agricultural sector instituted during the tenure of Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin. Most, if not all, of these reforms were based on recommendations from a committee known ...

of 1906 to 1914, which aimed to reduce radicalism amongst the peasantry and produce profit-minded, politically conservative farmers. During the Russian Revolution, ''kulak'' was used to chastise peasants who withheld grain from the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

. According to Marxist–Leninist political theories of the early 20th century, the kulaks were considered class enemies

The term enemy of the people or enemy of the nation, is a designation for the political or class opponents of the subgroup in power within a larger group. The term implies that by opposing the ruling subgroup, the "enemies" in question are ac ...

of the poorer peasants. Vladimir Lenin described them as "bloodsuckers, vampires, plunderers of the people and profiteers, who fatten themselves during famines", declaring revolution against them to liberate poor peasants, farm laborers, and proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philo ...

(the much smaller class of urban and industrial workers).

During the first five-year plan, Joseph Stalin's all-out campaign to take land ownership and organisation away from the peasantry meant that, according to historian Robert Conquest, "peasants with a couple of cows or five or six acres 2 hamore than their neighbors" were labeled ''kulaks''. In 1929, Soviet officials officially classified kulaks according to subjective criteria, such as the use of hired labour. Under dekulakization

Dekulakization (russian: раскулачивание, ''raskulachivanie''; uk, розкуркулення, ''rozkurkulennia'') was the Soviet campaign of political repressions, including arrests, deportations, or executions of millions of kula ...

, government officials seized farms and killed most resisters, deported others to labor camp

A labor camp (or labour camp, see spelling differences) or work camp is a detention facility where inmates are forced to engage in penal labor as a form of punishment. Labor camps have many common aspects with slavery and with prisons (especi ...

s, and drove many others to migrate to the cities following the loss of their property to the collectives.

Definitions

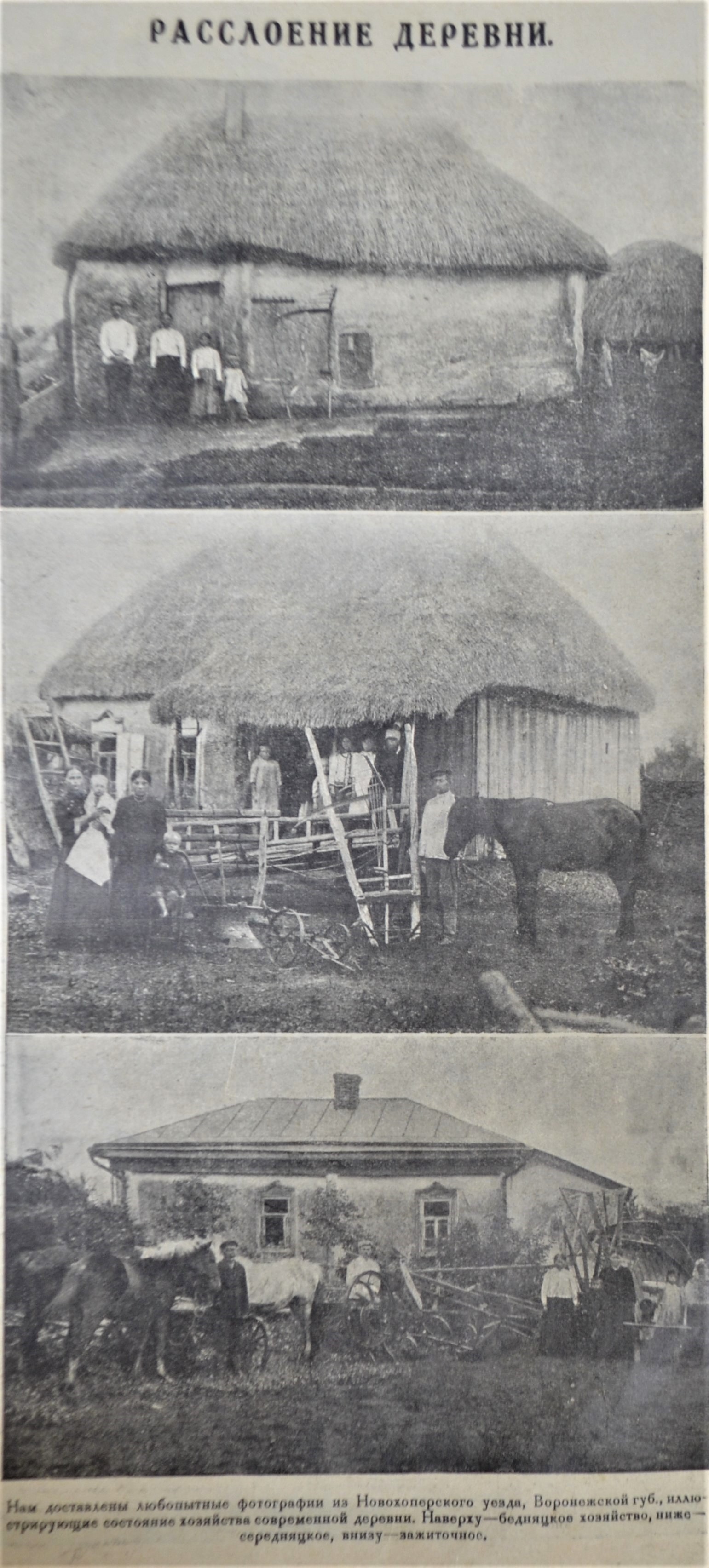

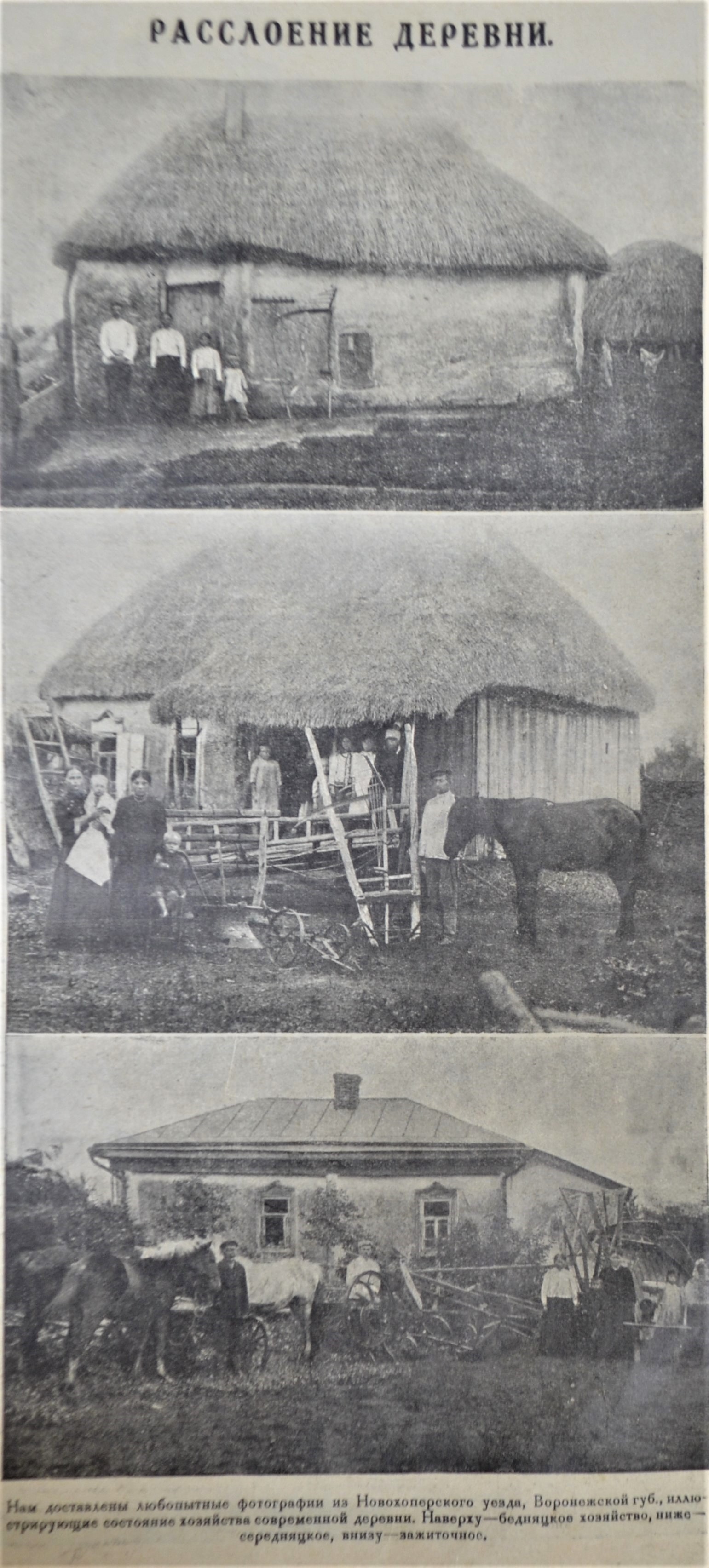

Soviet terminology divided the Russian peasants into three broad categories:

# ''Bednyak'', or poor peasants.

# ''Serednyak'', or mid-income peasants.

# ''Kulak'', the higher-income farmers who had larger farms.

In addition, they had a category of ''batrak'', landless seasonal agricultural workers for hire.

The

Soviet terminology divided the Russian peasants into three broad categories:

# ''Bednyak'', or poor peasants.

# ''Serednyak'', or mid-income peasants.

# ''Kulak'', the higher-income farmers who had larger farms.

In addition, they had a category of ''batrak'', landless seasonal agricultural workers for hire.

The Stolypin reform

The Stolypin agrarian reforms were a series of changes to Imperial Russia's agricultural sector instituted during the tenure of Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin. Most, if not all, of these reforms were based on recommendations from a committee known ...

created a new class of landowners by allowing peasants to acquire plots of land on credit from the large estate owners. They were to repay the credit (a kind of mortgage loan) from their farm earnings. By 1912, 16% of peasants (up from 11% in 1903) had relatively large endowments of over per male family member (a threshold used in statistics to distinguish between middle-class and prosperous farmers, i.e. the kulaks). At that time, an average farmer's family had 6 to 10 children. The number of such farmers amounted to 20% of the rural population, producing almost 50% of marketable grain.

1917–1918

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, theBolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

considered only ''batraks'' and ''bednyaks'' as true allies of the Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

s and proletariat; ''serednyaks'' were considered unreliable, hesitating allies, and ''kulaks'' were identified as class enemies

The term enemy of the people or enemy of the nation, is a designation for the political or class opponents of the subgroup in power within a larger group. The term implies that by opposing the ruling subgroup, the "enemies" in question are ac ...

, with the term generally referring to "peasant producers who hired labourers or exploited their neighbours in some other way" according to historian Robert W. Davies. Robert Conquest argues that the definition of a kulak was later expanded to include those peasants who owned livestock; however, a middle peasant who did not hire laborers and was little engaged in trade "might yet (if he had a large family) hold three cows and two horses."

There were other measures that indicated the kulaks as not being especially prosperous. Both peasants and Soviet officials were uncertain as to who constituted a ''kulak''; they often used the term to label anyone who had more property than was considered normal according to subjective criteria, and personal rivalries also played a part in the classification of people as enemies. Officials arbitrarily applied the definition and abused their power. Conquest wrote: "The land of the landlords had been spontaneously seized by the peasantry in 1917–18. A small class of richer peasants with around had then been expropriated by the Bolsheviks. Thereafter a Marxist conception of class struggle

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in society because of socio-economic competition among the social classes or between rich and poor.

The forms o ...

led to an almost totally imaginary class categorization being inflicted in the villages, where peasants with a couple of cows or five or six acres bout 2 hamore than their neighbors were now being labeled 'kulaks,' and a class war against them was being declared."

In the summer of 1918, Moscow sent armed detachments to the villages and ordered them to seize grain. Peasants who resisted the seizures were labeled ''kulaks''. According to Richard Pipes

Richard Edgar Pipes ( yi, ריכארד פּיִפּעץ ''Rikhard Pipets'', the surname literally means 'beak'; pl, Ryszard Pipes; July 11, 1923 – May 17, 2018) was an American academic who specialized in Russian and Soviet history. He publi ...

, "the Communists declared war on the rural population for two purposes: to forcibly extract food for growing industry (so-called First five-year plan) in cities and the Red Army and insinuate their authority into the countryside, which remained largely unaffected by the Bolshevik coup." A large-scale revolt ensued, and it was during this period in August 1918 that Vladimir Lenin sent a directive known as Lenin's Hanging Order: "Hang (hang without fail, so the people see) no fewer than one hundred known kulaks, rich men, bloodsuckers. ... Do it in such a way that for hundreds of versts ilometersaround the people will see, tremble, know, shout: they are strangling and will strangle to death the bloodsucker kulaks."

1930s

The average value of the goods which were confiscated from the kulaks during the policy ofdekulakization

Dekulakization (russian: раскулачивание, ''raskulachivanie''; uk, розкуркулення, ''rozkurkulennia'') was the Soviet campaign of political repressions, including arrests, deportations, or executions of millions of kula ...

() at the beginning of the 1930s was only 170–400 rubles (US$90–210) per household. During the height of Collectivization in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union introduced the collectivization (russian: Коллективизация) of its agricultural sector between 1928 and 1940 during the ascension of Joseph Stalin. It began during and was part of the first five-year plan. ...

in the early 1930s, people who were identified as kulaks were subjected to deportation and extrajudicial punishments. They were frequently murdered in local campaigns of violence, while others were formally executed after they were convicted of being kulaks.

In May 1929, the Sovnarkom issued a decree which formalised the notion of 'kulak household' (), according to which any of the following criteria defined a person as a ''kulak'':

* Use of hired labor.

* Ownership of a mill

Mill may refer to:

Science and technology

*

* Mill (grinding)

* Milling (machining)

* Millwork

* Textile mill

* Steel mill, a factory for the manufacture of steel

* List of types of mill

* Mill, the arithmetic unit of the Analytical Engine early ...

, a creamery

A creamery is a place where milk and cream are processed and where butter and cheese is produced. Cream is separated from whole milk; pasteurization is done to the skimmed milk and cream separately. Whole milk for sale has had some cream ret ...

(, 'butter-making rig'), other processing equipment, or a complex machine with a motor.

* Systematic renting out of agricultural equipment or facilities.

* Involvement in trade, money-lending, commercial brokerage, or "other sources of non-labor income."

In 1930, this list was expanded so it could include people who were renting industrial plants, e.g. sawmill

A sawmill (saw mill, saw-mill) or lumber mill is a facility where logs are cut into lumber. Modern sawmills use a motorized saw to cut logs lengthwise to make long pieces, and crosswise to length depending on standard or custom sizes (dimensi ...

s, or people who rented land to other farmers. At the same time, the ispolkom The Executive Committee of the Petrograd Soviet, commonly known as the Ispolkom (russian: исполком, исполнительный комитет, literally " executive committee") was a self-appointed executive committee of the Petrograd Sov ...

s (executive committees of local Soviets) of republics, oblasts, and krai

A krai or kray (; russian: край, , ''kraya'') is one of the types of federal subjects of modern Russia, and was a type of geographical administrative division in the Russian Empire and the Russian SFSR.

Etymologically, the word is rela ...

s were granted the right to add other criteria to the list so other people could be classified as kulaks, depending on local conditions.

Dekulakization

In July 1929, official Soviet policy continued to state that the kulaks should not be terrorized and should be enlisted into thecollective farms

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member- ...

, but Stalin disagreed: "Now we have the opportunity to carry out a resolute offensive against the kulaks, break their resistance, eliminate them as a class and replace their production with the production of kolkhozes and sovkhozes." A decree by the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks)

The Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, – TsK KPSS was the executive leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, acting between sessions of Congress. According to party statutes, the committee directe ...

on 5 January 1930 was titled "On the pace of collectivization and state assistance to collective-farm construction." The official goal of "kulak liquidation" came without precise instructions, and encouraged local leaders to take radical action, which resulted in physical elimination. The campaign to "liquidate the kulaks as a class" constituted the main part of Stalin's social engineering policies in the early 1930s. Andrei Suslov argues that the seizure of peasants' property led directly to the destruction of an entire social group, that of the peasant‐owners.

On 30 January 1930, the Politburo approved the dissolving of the kulaks as a class. Three categories of kulaks were distinguished: kulaks who were supposed to be sent to the Gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= was the government agency in ...

s, kulaks who were supposed to be relocated to distant provinces, such as the north Urals and Kazakhstan, kulaks who were supposed to be sent to other areas within their home provinces. The peasantry were required to relinquish their farm animals to government authorities. Many chose to slaughter their livestock rather than give them up to collective farms. In the first two months of 1930, peasants killed millions of cattle, horses, pigs, sheep and goats, with the meat and hides being consumed and bartered. For instance, the Soviet Party Congress reported in 1934 that 26.6 million head of cattle and 63.4 million sheep had been lost. In response to the widespread slaughter, the Sovnarkom issued decrees to prosecute "the malicious slaughtering of livestock" (). Stalin ordered severe measures to end kulak resistance. In 1930, he declared: "In order to oust the 'kulaks' as a class, the resistance of this class must be smashed in open battle and it must be deprived of the productive sources of its existence and development. ... That is a turn towards the policy of eliminating the kulaks as a class."

Human impact

From 1929–1933, the grain quotas were artificially heightened. Peasants attempted to hide the grain and bury it. According to historian Robert Conquest, every brigade was equipped with a long iron bar which it would use to probe the ground for grain caches and peasants who did not show signs of starvation were especially suspected of hiding food. Conquest states: "When the snow melted true starvation began. People had swollen faces and legs and stomachs. They could not contain their urine... And now they ate anything at all. They caught mice, rats, sparrows, ants, earthworms. They ground up bones into flour, and did the same with leather and shoe soles ... ." The party activists who helped the State Political Directorate (the secret police) with arrests and deportations were, in the words ofVasily Grossman

Vasily Semyonovich Grossman (russian: Васи́лий Семёнович Гро́ссман; 12 December (29 November, Julian calendar) 1905 – 14 September 1964) was a Soviet writer and journalist.

Born to a Jewish family in Ukraine, then ...

, "all people who knew one another well, and knew their victims, but in carrying out this task they became dazed, stupefied." Grossman commented: "They would threaten people with guns, as if they were under a spell, calling small children 'kulak bastards,' screaming 'bloodsuckers!' ... They had sold themselves on the idea that so-called 'kulaks' were pariahs, untouchables, vermin. They would not sit down at a 'parasite's' table; the 'kulak' child was loathsome, the young 'kulak' girl was lower than a louse." Party activists brutalizing the starving villagers fell into cognitive dissonance

In the field of psychology, cognitive dissonance is the perception of contradictory information, and the mental toll of it. Relevant items of information include a person's actions, feelings, ideas, beliefs, values, and things in the environmen ...

, rationalizing their actions through ideology. Lev Kopelev

Lev Zalmanovich (Zinovyevich) Kopelev (russian: Лев Залма́нович (Зино́вьевич) Ко́пелев, German: Lew Sinowjewitsch Kopelew, 9 April 1912, Kyiv – 18 June 1997, Cologne) was a Soviet author and dissident.

Early ...

, who later became a Soviet dissident

A dissident is a person who actively challenges an established political or religious system, doctrine, belief, policy, or institution. In a religious context, the word has been used since the 18th century, and in the political sense since the ...

, explained: "It was excruciating to see and hear all of this. And even worse to take part in it. ... And I persuaded myself, explained to myself. I mustn't give in to debilitating pity. We were realizing historical necessity. We were performing our revolutionary duty. We were obtaining grain for the socialist fatherland. For the Five-Year Plan."

Death tolls

Stalin issued an order for the kulaks "to be liquidated as a class"; according toRoman Serbyn

Roman Serbyn (born 21 March 1939) is an historian, and a professor emeritus of History of Russia, Russian and East European history at the University of Quebec at Montreal, and an expert on Ukraine. He currently resides in Montreal, Canada.

Serby ...

, this was the main cause of the Soviet famine of 1932–1933 and was a genocide, while other scholars disagree and propose more than one cause. This famine has complicated attempts to identify the number of deaths arising from the executions of kulaks. A wide range of death tolls has been suggested, from as many as six million as suggested by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Russian novelist. One of the most famous Soviet dissidents, Solzhenitsyn was an outspoken critic of communism and helped to raise global awareness of political repres ...

, to the much lower number of 700,000 as estimated by Soviet sources. According to data from the Soviet archives, which were only published in 1990, 1,803,392 people were sent to labor colonies

A labor camp (or labour camp, see spelling differences) or work camp is a detention facility where inmates are forced to engage in penal labor as a form of punishment. Labor camps have many common aspects with slavery and with prisons (especi ...

and camps in 1930 and 1931. Books which are based on these sources have stated that 1,317,022 people reached the final destinations. The fate of the remaining 486,370 people cannot be verified. Deportations continued on a smaller scale after 1931. The reported number of kulaks and their relatives who died in labor colonies from 1932 to 1940 was 389,521. Former kulaks and their families made up the majority of the victims of the Great Purge of the late 1930s, with 669,929 people arrested and 376,202 people executed.

See also

*Classicide

Classicide is a concept proposed by sociologist Michael Mann to describe the deliberate and systematic destruction, in whole or in part, of a social class through persecution and violence. Although it was first used by physician and anti-communist ...

* '' Earth'' (1930), a Ukrainian film by Alexander Dovzhenko

Oleksandr Petrovych Dovzhenko or Alexander Petrovich Dovzhenko ( uk, Олександр Петрович Довженко, ''Oleksandr Petrovych Dovzhenko''; russian: Алекса́ндр Петро́вич Довже́нко, ''Aleksandr Petro ...

concerning a community of farmers and their resistance to collectivization. ''Earth'' depicts the social struggles between kulaks and a youth who introduces a tractor to a Ukrainian village.

* Gombeen man

A gombeen man is a pejorative Hiberno-English term used in Ireland for a shady, small-time "wheeler-dealer" businessman or politician who is always looking to make a quick profit, often at someone else's expense or through the acceptance of bribes. ...

* Landlord

* Land tenure

* Ural-Siberian method

* Yeoman

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of servants in an English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in mid-14th-century England. The 14th century also witn ...

References

Further reading

*Conquest, Robert

George Robert Acworth Conquest (15 July 1917 – 3 August 2015) was a British historian and poet.

A long-time research fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution, Conquest was most notable for his work on the Soviet Union. His books ...

. 1987. '' The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine.''

* Douglas, Tottle. 1987. ''Fraud, Famine And Fascism: The Ukrainian Genocide Myth from Hitler to Harvard''

* Figes, Orlando. 2007. ''The whisperers: private life in Stalin's Russia''. Macmillan. … detailed histories of actual Kulak familiesonline free to borrow

* Kaznelson, Michael. 2007. "Remembering the Soviet State: Kulak children and dekulakisation." ''

Europe-Asia Studies

''Europe-Asia Studies'' is an academic peer-reviewed journal published 10 times a year by Routledge on behalf of the Institute of Central and East European Studies, University of Glasgow, and continuing (since vol. 45, 1993) the journal ''Soviet ...

'' 59(7):1163–77.

* Lewin, Moshe. 1966. "Who was the Soviet kulak?." ''Europe‐Asia Studies'' 18(2):189–212.

* Viola, Lynne. 1986. "The Campaign to Eliminate the Kulak as a Class, Winter 1929–1930: A Reevaluation of the Legislation." ''Slavic Review

The ''Slavic Review'' is a major peer-reviewed academic journal publishing scholarly studies, book and film reviews, and review essays in all disciplines concerned with Russia, Central Eurasia, and Eastern and Central Europe. The journal's tit ...

'' 45(3):503–24.

* —— 2000. "The Peasants' Kulak: Social Identities and Moral Economy in the Soviet Countryside in the 1920s." ''Canadian Slavonic Papers

''Canadian Slavonic Papers / Revue canadienne des slavistes'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal covering Central and Eastern European studies. It is the official journal of the Canadian Association of Slavists and published on its be ...

'' 42(4):431–60.

* Vossler, Ron, narrator. 2006.We'll Meet Again in Heaven

" US:

Prairie Public Prairie Public Broadcasting is a community-owned public broadcaster based in North Dakota, Minnesota, and Montana, with coverage extending into South Dakota, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Northwestern Ontario. It operates Prairie Public Radio, a radi ...

and Roadshow Productions.

** "This thirty-minute documentary is a searing chronicle of a forgotten genocide and a lost people, whose '... misery screams to the heavens.' The lost people are the ethnic German minority living in Soviet Ukraine, who wrote their American relatives about the starvation, forced labor, and execution that were almost daily fare in Soviet Ukraine during this period, 1928–1938...major funding by the Germans from Russia Heritage Collection, North Dakota State University Libraries

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north'' is ...

, Fargo, North Dakota."

{{authority control

Forced migration in the Soviet Union

Society of the Soviet Union

Class-related slurs

Political repression in the Soviet Union

Social groups of Russia

Soviet phraseology