klepht on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

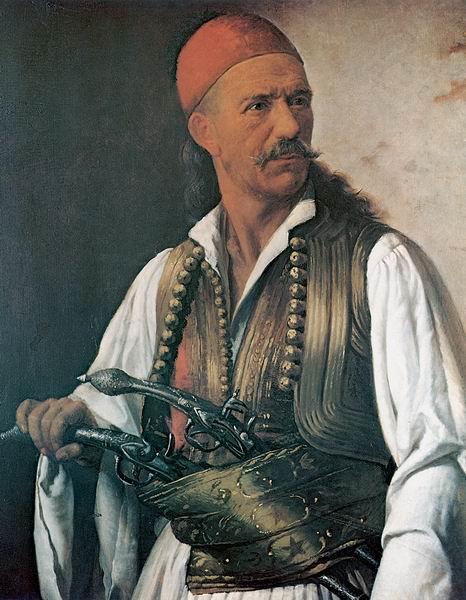

Klephts (; Greek κλέφτης, ''kléftis'', pl. κλέφτες, ''kléftes'', which means "thieves" and perhaps originally meant just "brigand": "Other Greeks, taking to the mountains, became unofficial, self-appointed armatoles and were known as klephts (from the Greek ''kleptes'', "brigand").") were highwaymen turned self-appointed armatoloi, anti-Ottoman insurgents, and warlike mountain-folk who lived in the countryside when

Klephts (; Greek κλέφτης, ''kléftis'', pl. κλέφτες, ''kléftes'', which means "thieves" and perhaps originally meant just "brigand": "Other Greeks, taking to the mountains, became unofficial, self-appointed armatoles and were known as klephts (from the Greek ''kleptes'', "brigand").") were highwaymen turned self-appointed armatoloi, anti-Ottoman insurgents, and warlike mountain-folk who lived in the countryside when

Klephtic songs (Greek: κλέφτικα τραγούδια), or ballads, were developed in mainland Greece. They are part of the Greek folk music genre, which includes folk poetry, and are thematically oriented on either the achievements and death of a single klepht or the generic life of the klephts as a group. Klephtic songs are especially popular in Epirus and the Peloponnese. The Czech composer Antonín Dvořák wrote a song-cycle named ''Three Modern Greek Poems'': the first one is entitled "Koljas – Klepht Song" and tells the story of Koljas, the klepht who killed the famous Ali Pasha.

The most famous klephtic and modern Greek folk song is ''The Battle of Mount Olympus and Mount Kisavos'', a ballad based on a musico-poetic motif dating back to classical Greece (specifically to the poetic song composed by Corinna pertaining to a contest between

Klephtic songs (Greek: κλέφτικα τραγούδια), or ballads, were developed in mainland Greece. They are part of the Greek folk music genre, which includes folk poetry, and are thematically oriented on either the achievements and death of a single klepht or the generic life of the klephts as a group. Klephtic songs are especially popular in Epirus and the Peloponnese. The Czech composer Antonín Dvořák wrote a song-cycle named ''Three Modern Greek Poems'': the first one is entitled "Koljas – Klepht Song" and tells the story of Koljas, the klepht who killed the famous Ali Pasha.

The most famous klephtic and modern Greek folk song is ''The Battle of Mount Olympus and Mount Kisavos'', a ballad based on a musico-poetic motif dating back to classical Greece (specifically to the poetic song composed by Corinna pertaining to a contest between

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

was a part of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

. They were the descendants of Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, ot ...

who retreated into the mountains during the 15th century in order to avoid Ottoman rule.: "The klephts were descendants of Greeks who fled into the mountains to avoid the Turks in the fifteenth century and who remained active as brigands into the nineteenth century." They carried on a continuous war against Ottoman rule and remained active as brigands until the 19th century.

The terms kleptomania and kleptocracy are derived from the same Greek root, κλέπτειν (''kléptein''), "to steal".

Origins

After the Fall of Constantinople in 1453 and then the fall ofMistra

Mystras or Mistras ( el, Μυστρᾶς/Μιστρᾶς), also known in the ''Chronicle of the Morea'' as Myzithras (Μυζηθρᾶς), is a fortified town and a former municipality in Laconia, Peloponnese, Greece. Situated on Mt. Taygetus, ...

in the Despotate of the Morea, most of the plains of present-day Greece fell entirely into the hands of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

. The only territories that did not fall under Ottoman rule were the mountain ranges (populated by Greeks and inaccessible to the Ottoman Turks), as well as a handful of islands and coastal possessions under the control of Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

. This situation lasted until 1821. However, the newly acquired territories of Greece, such as Macedonia, Thrace and Epirus, were in Turkish hands until the 20th century. This period of time in Greece is known as the Turkocracy.

Ottoman lands were divided up into pashaliks, also called eyalets

Eyalets (Ottoman Turkish: ایالت, , English: State), also known as beylerbeyliks or pashaliks, were a primary administrative division of the Ottoman Empire.

From 1453 to the beginning of the nineteenth century the Ottoman local government ...

; in the case of the lands that form present-day Greece, these were Morea and Roumelia. Pashaliks were further sub-divided into sanjaks which were often divided into feudal chifliks ( Turkish ''çiftlik'' (farm), Greek ''τσιφλίκι'' ''tsifliki''). Any surviving Greek troops, whether regular Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

forces, local militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

, or mercenaries had either to join the Ottoman army as janissaries, serve in the private army of a local Ottoman notable, or fend for themselves. Many Greeks wishing to preserve their Greek identity, Orthodox Christian religion, and independence chose the difficult but liberated life of a bandit. These bandit groups soon found their ranks swelled with impoverished and/or adventurous peasants, societal outcasts, and escaped criminals.

Klephts under Ottoman rule were generally men who were fleeing vendettas or taxes, debt

Debt is an obligation that requires one party, the debtor, to pay money or other agreed-upon value to another party, the creditor. Debt is a deferred payment, or series of payments, which differentiates it from an immediate purchase. The ...

s and reprisal

A reprisal is a limited and deliberate violation of international law to punish another sovereign state that has already broken them. Since the 1977 Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions (AP 1), reprisals in the laws of war are extreme ...

s from Ottoman officials. They raided travelers and isolated settlements and lived in the rugged mountains and back country. Most klephtic bands participated in some form in the Greek War of Independence. During the Greek War of Independence, the klephts, along with the armatoloi, formed the nucleus of the Greek fighting forces, and played a prominent part throughout its duration. Despite being ineffective, they were the only viable military force for the provisional governments of the 1821-1827 period. During that time period, three attempts were made at creating a regular army, and one the reasons for their failure was the resistance of the klepht and armatoles leaders. Yannis Makriyannis

Yannis Makriyannis ( el, Γιάννης Μακρυγιάννης, ''Giánnēs Makrygiánnīs''; 1797–1864), born Ioannis Triantaphyllou (, ''Iōánnēs Triantafýllou''), was a Greek merchant, military officer, politician and author, best ...

referred to the "klephtes and armatoloi" as the "yeast of liberty". John Koliopoulos studied the klephts in the 19th century, and stated that the principle of kinship and honour seen in Albanian '' besa'' could be seen among the klephts after centuries of contact with Albanian irregulars.

Contrary to conventional Greek history, many of the klephts and armatoles participated at the Greek War of Independence according to their own militaristic patron-client terms. They saw the war as an economic and political opportunity to expand their areas of operation. Balkan bandits such as the klephts and armatoles - glorified in nationalist historiography as national heroes - were actually driven by economic interests, were not aware of national projects, made alliances with the Ottomans and robbed Christians as much as Muslims.

Songs

Klephtic songs (Greek: κλέφτικα τραγούδια), or ballads, were developed in mainland Greece. They are part of the Greek folk music genre, which includes folk poetry, and are thematically oriented on either the achievements and death of a single klepht or the generic life of the klephts as a group. Klephtic songs are especially popular in Epirus and the Peloponnese. The Czech composer Antonín Dvořák wrote a song-cycle named ''Three Modern Greek Poems'': the first one is entitled "Koljas – Klepht Song" and tells the story of Koljas, the klepht who killed the famous Ali Pasha.

The most famous klephtic and modern Greek folk song is ''The Battle of Mount Olympus and Mount Kisavos'', a ballad based on a musico-poetic motif dating back to classical Greece (specifically to the poetic song composed by Corinna pertaining to a contest between

Klephtic songs (Greek: κλέφτικα τραγούδια), or ballads, were developed in mainland Greece. They are part of the Greek folk music genre, which includes folk poetry, and are thematically oriented on either the achievements and death of a single klepht or the generic life of the klephts as a group. Klephtic songs are especially popular in Epirus and the Peloponnese. The Czech composer Antonín Dvořák wrote a song-cycle named ''Three Modern Greek Poems'': the first one is entitled "Koljas – Klepht Song" and tells the story of Koljas, the klepht who killed the famous Ali Pasha.

The most famous klephtic and modern Greek folk song is ''The Battle of Mount Olympus and Mount Kisavos'', a ballad based on a musico-poetic motif dating back to classical Greece (specifically to the poetic song composed by Corinna pertaining to a contest between Mount Helicon

Mount Helicon ( grc, Ἑλικών; ell, Ελικώνας) is a mountain in the region of Thespiai in Boeotia, Greece, celebrated in Greek mythology. With an altitude of , it is located approximately from the north coast of the Gulf of Cori ...

and Mount Cithaeron

Cithaeron or Kithairon (Κιθαιρών, -ῶνος) is a mountain and mountain range about sixteen kilometres (ten miles) long in Central Greece. The range is the physical boundary between Boeotia in the north and Attica in the south. It is mai ...

).

Cuisine

The famous Greek dish '' klephtiko'' (or kleftiko), a dish entailing slow-cooked lamb (or other meat), can be translated "in the style of the klephts". The klephts, not having flocks of their own, would steal lambs or goats and cook the meat in a sealed pit to avoid the smoke being seen.Famous klephts

* Antonis Katsantonis * Giorgakis Olympios * Odysseas Androutsos * Athanasios Diakos *Geórgios Karaïskákis

Georgios Karaiskakis ( el, Γεώργιος Καραϊσκάκης), born Georgios Karaiskos ( el, Γεώργιος Καραΐσκος; 1782 – 1827), was a famous Greek military commander and a leader of the Greek War of Independence.

Early l ...

* Theodoros Kolokotronis

*Dimitrios Makris

Dimitrios Makris ( el, Δημήτριος Μακρής, 1772–1841) was a Greek klepht and armatolos who was one of the most powerful chieftains in West Central Greece. He joined the Filiki Eteria and became a revolutionary during the Greek Wa ...

* Nikitas Stamatelopoulos

See also

* Armatoloi * Hajduk *Uskok

The Uskoks ( hr, Uskoci, , singular: ; notes on naming) were irregular soldiers in Habsburg Croatia that inhabited areas on the eastern Adriatic coast and surrounding territories during the Ottoman wars in Europe. Bands of Uskoks fought a g ...

* Ottoman Greece

References

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * {{Greek War of Independence, state=collapsed Greek War of Independence Greek outlaws