Internationalism (politics) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Internationalism is a political principle that advocates greater political or economic cooperation among states and

In 19th-century

In 19th-century  Other international organizations included the

Other international organizations included the

The

The

The Communist International, also known as the Comintern or the Third International, was formed in 1919 in the wake of the

The Communist International, also known as the Comintern or the Third International, was formed in 1919 in the wake of the

Big Leagues: Specters of Milton and Republican International Justice between Shakespeare and Marx

” ''Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development'', Vol. 7. Pg. 380. Marx and Engels, Warren claims, understood the empowering potential of Miltonic republican traditions for forging international coalitions—a lesson, perhaps, for “The New International.”

Big Leagues: Specters of Milton and Republican International Justice between Shakespeare and Marx.

�� ''Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development'', Vol. 7.

''Pop Internationalism'' by Paul Krugman

''Internationalism on Facebook''

{{Authority control Anarchism Anti-nationalism Communism Human migration Islamism Nationalism Politics and race Socialism World government Political movements

nation

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective identity of a group of people understood as defined by th ...

s. It is associated with other political movement

A political movement is a collective attempt by a group of people to change government policy or social values. Political movements are usually in opposition to an element of the status quo, and are often associated with a certain ideology. Some ...

s and ideologies, but can also reflect a doctrine, belief system, or movement in itself.Warren F. Kuehl, Concepts of Internationalism in History, July 1986.

Supporters of internationalism are known as internationalists and generally believe that humans should unite across national, political, cultural, racial, or class boundaries to advance their common interests, or that governments should cooperate because their mutual long-term interests are of greater importance than their short-term disputes.

Internationalism has several interpretations and meanings, but is usually characterized by opposition to nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

and isolationism

Isolationism is a political philosophy advocating a national foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality and opposes entangl ...

; support for international institutions, such as the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

; and a cosmopolitan outlook that promotes and respects other cultures and customs.

The term is similar to, but distinct from, globalism

Globalism refers to various patterns of meaning beyond the merely international. It is used by political scientists, such as Joseph Nye, to describe "attempts to understand all the interconnections of the modern world—and to highlight pattern ...

and cosmopolitanism

Cosmopolitanism is the idea that all human beings are members of a single community. Its adherents are known as cosmopolitan or cosmopolite. Cosmopolitanism is both prescriptive and aspirational, believing humans can and should be " world citizen ...

.

Origins

In 19th-century

In 19th-century Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

, there was a liberal internationalist strand of political thought epitomized by Richard Cobden and John Bright. Cobden and Bright were against the protectionist Corn Law

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. They were ...

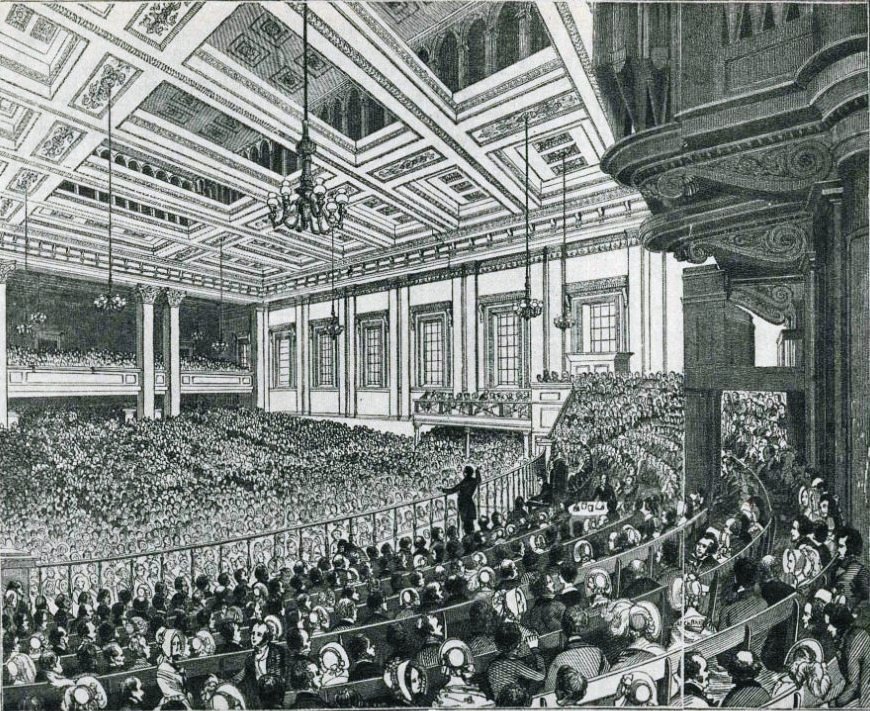

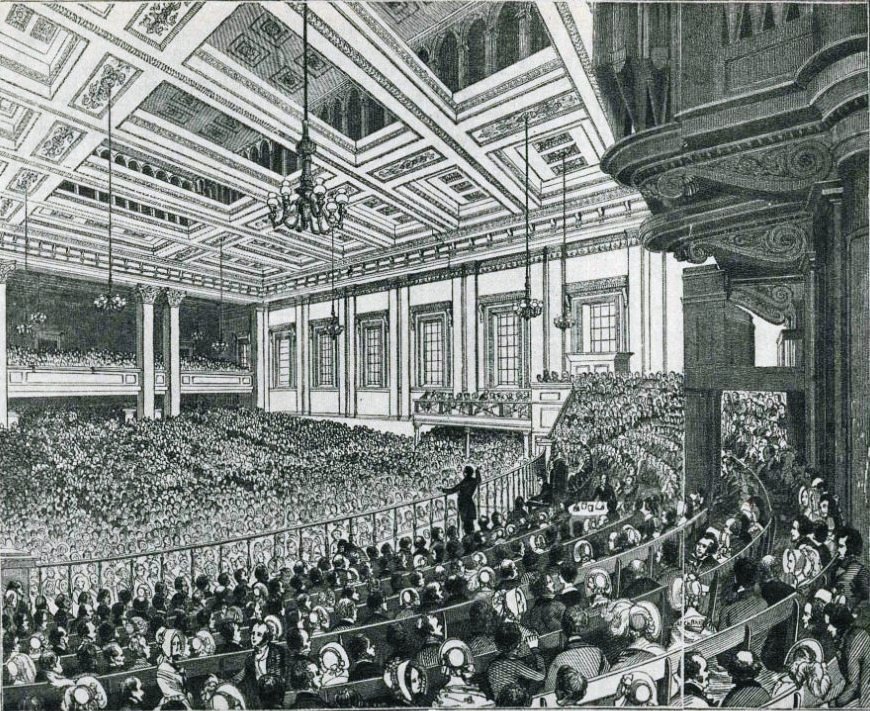

s and in a speech at Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist si ...

on September 28, 1843, Cobden outlined his utopian brand of internationalism:

Cobden believed that Free Trade would pacify the world byFree Trade Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...! What is it? Why, breaking down the barriers that separate nations; those barriers behind which nestle the feelings ofpride Pride is defined by Merriam-Webster as "reasonable self-esteem" or "confidence and satisfaction in oneself". A healthy amount of pride is good, however, pride sometimes is used interchangeably with "conceit" or "arrogance" (among other words) w ...,revenge Revenge is committing a harmful action against a person or group in response to a grievance, be it real or perceived. Francis Bacon described revenge as a kind of "wild justice" that "does... offend the law ndputteth the law out of office." P ...,hatred Hatred is an intense negative emotional response towards certain people, things or ideas, usually related to opposition or revulsion toward something. Hatred is often associated with intense feelings of anger, contempt, and disgust. Hatred is ...and jealously, which every now and then burst their bounds and deluge whole countries with blood.

interdependence

Systems theory is the interdisciplinary study of systems, i.e. cohesive groups of interrelated, interdependent components that can be natural or human-made. Every system has causal boundaries, is influenced by its context, defined by its structu ...

, an idea also expressed by Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——� ...

in his The Wealth of Nations

''An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations'', generally referred to by its shortened title ''The Wealth of Nations'', is the '' magnum opus'' of the Scottish economist and moral philosopher Adam Smith. First published in ...

and common to many liberals of the time. A belief in the idea of the moral law and an inherent goodness in human nature

Human nature is a concept that denotes the fundamental dispositions and characteristics—including ways of thinking, feeling, and acting—that humans are said to have naturally. The term is often used to denote the essence of humankind, or ...

also inspired their faith in internationalism.

Those liberal conceptions of internationalism were harshly criticized by socialists and radicals at the time, who pointed out the links between global economic competition and imperialism, and would identify this competition as being a root cause of world conflict. One of the first international organisations in the world was the International Workingmen's Association

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA), often called the First International (1864–1876), was an international organisation which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, communist and anarchist groups and trad ...

, formed in London in 1864 by working class socialist and communist political activists (including Karl Marx). Referred to as the First International, the organization was dedicated to the advancement of working class political interests across national boundaries, and was in direct ideological opposition to strains of liberal internationalism which advocated free trade and capitalism as means of achieving world peace and interdependence.

Inter-Parliamentary Union

The Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU; french: Union Interparlementaire, UIP) is an international organization of national parliaments. Its primary purpose is to promote democratic governance, accountability, and cooperation among its members; other ...

, established in 1889 by Frédéric Passy from France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and William Randal Cremer

Sir William Randal Cremer (18 March 1828 – 22 July 1908) usually known by his middle name "Randal", was a British Liberal Member of Parliament, a pacifist, and a leading advocate for international arbitration. He was awarded the Nobel Peace ...

from the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

, and the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

, which was formed after World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. The former was envisioned as a permanent forum for political multilateral negotiations, while the latter was an attempt to solve the world's security problems through international arbitration and dialogue.

J. A. Hobson

John Atkinson Hobson (6 July 1858 – 1 April 1940) was an English economist and social scientist. Hobson is best known for his writing on imperialism, which influenced Vladimir Lenin, and his theory of underconsumption.

His principal and ea ...

, a Gladstonian liberal who became a socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

after the Great War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, anticipated in his book ''Imperialism'' (1902) the growth of international courts and congresses which would hopefully settle international disputes between nations in a peaceful way. Sir Norman Angell in his work ''The Great Illusion'' (1910) claimed that the world was united by trade, finance, industry and communications and that therefore nationalism was an anachronism and that war would not profit anyone involved but would only result in destruction.

Lord Lothian was an internationalist and an imperialist

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power ( economic and ...

who in December 1914 looked forward to "the voluntary federation of the free civilised nations which will eventually exorcise the spectre of competitive armaments and give lasting peace to mankind."

In September 1915, he thought the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

was "the perfect example of the eventual world Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

."

Internationalism expressed itself in Britain through the endorsement of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

by such people as Gilbert Murray. The Liberal Party and the Labour Party had prominent internationalist members, like the Labour Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

who believed that 'our true nationality

Nationality is a legal identification of a person in international law, establishing the person as a subject, a ''national'', of a sovereign state. It affords the state jurisdiction over the person and affords the person the protection of t ...

is mankind'

Socialism

Internationalism is an important component ofsocialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

political theory, based on the principle that working-class people of all countries must unite across national boundaries and actively oppose nationalism and war in order to overthrow capitalism (see entry on proletarian internationalism

Proletarian internationalism, sometimes referred to as international socialism, is the perception of all communist revolutions as being part of a single global class struggle rather than separate localized events. It is based on the theory that ...

). In this sense, the socialist understanding of internationalism is closely related to the concept of international solidarity

''Solidarity'' is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. It is based on class collaboration.''Merriam Webster'', http://www.merriam-webster.com/dicti ...

.

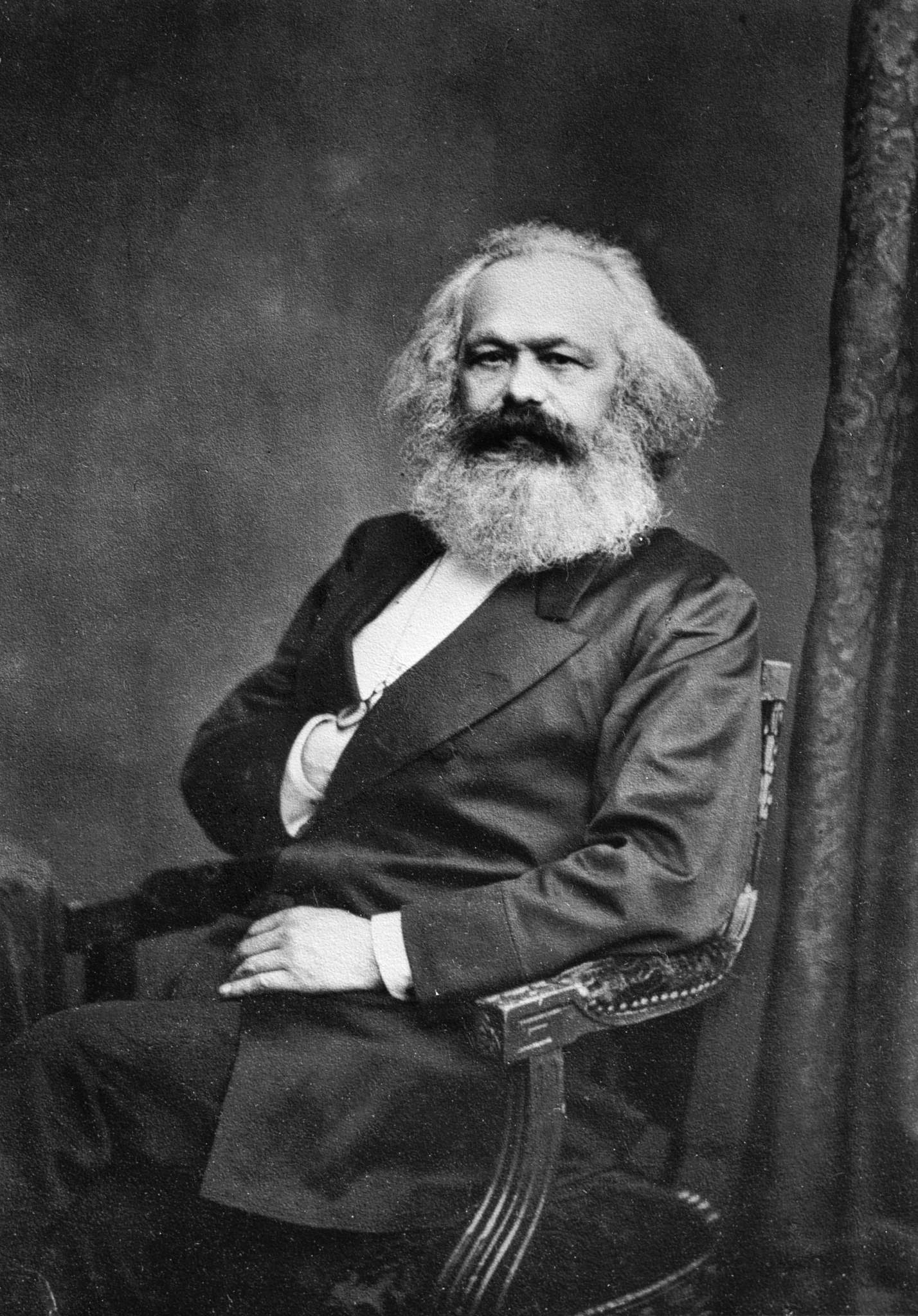

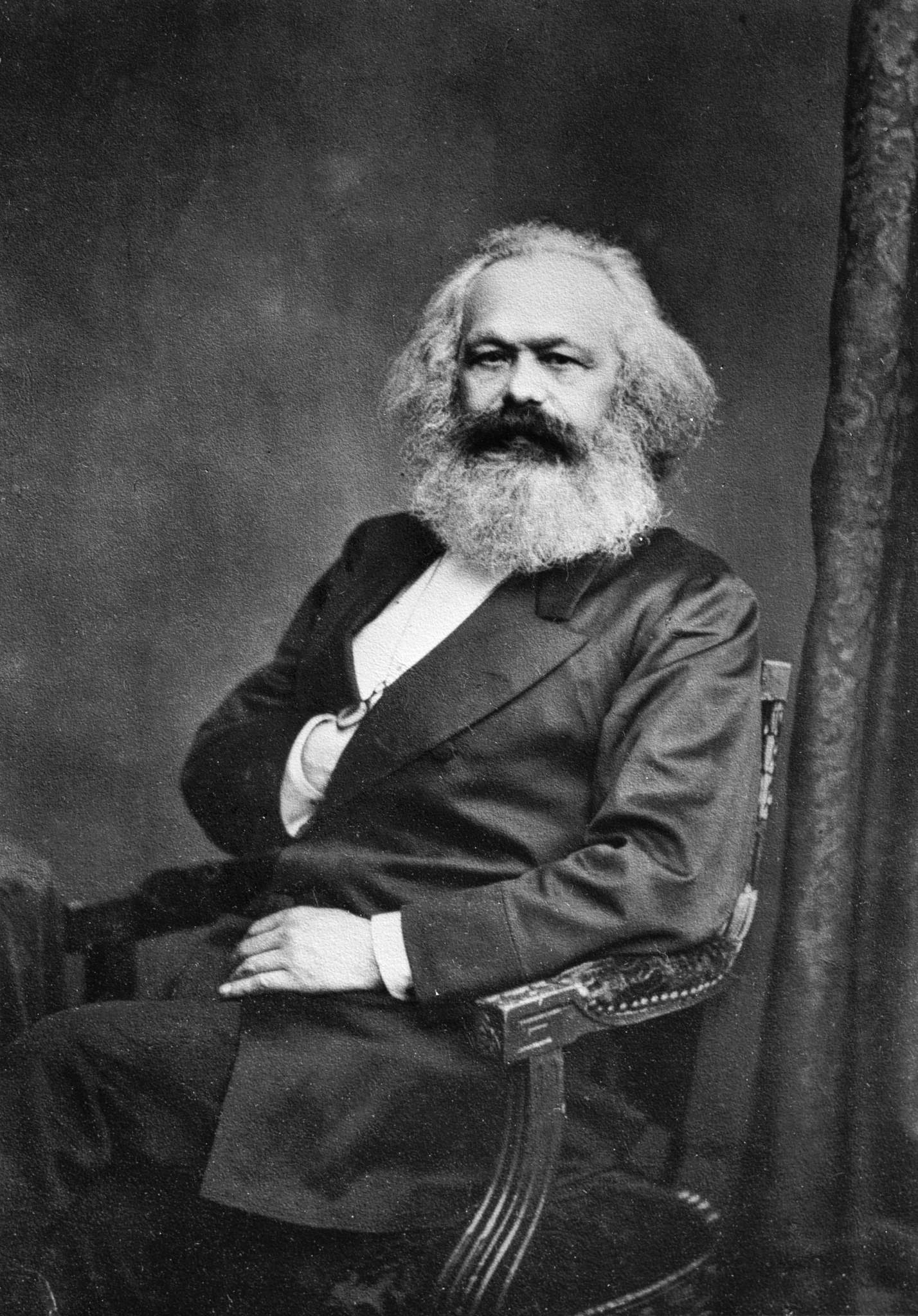

Socialist thinkers such as Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

, Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

'' Vladimir Lenin Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

argue that economic class, rather than (or interrelated with) nationality, race, or culture, is the main force which divides people in society, and that nationalist ideology is a '' Vladimir Lenin Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

tool of a society's dominant economic class. From this perspective, it is in the ruling class' interest to promote nationalism in order to hide the inherent class conflicts at play within a given society (such as the exploitation of workers by capitalists for profit). Therefore, socialists see nationalism as a form of ideological control arising from a society's given mode of economic production (see dominant ideology

In Marxist philosophy, the term dominant ideology denotes the attitudes, beliefs, values, and morals shared by the majority of the people in a given society. As a mechanism of social control, the dominant ideology frames how the majority of the ...

).

Since the 19th century, socialist political organizations and radical trade unions such as the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines general ...

have promoted internationalist ideologies and sought to organize workers across national boundaries to achieve improvements in the conditions of labor and advance various forms of industrial democracy. The First, Second

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds ea ...

, Third

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (disambiguation)

* Third Avenue (disambiguation)

* Hi ...

, and Fourth Internationals were socialist political groupings which sought to advance worker's revolution across the globe and achieve international socialism (see world revolution).

Socialist internationalism is anti-imperialist, and therefore supports the liberation

Liberation or liberate may refer to:

Film and television

* ''Liberation'' (film series), a 1970–1971 series about the Great Patriotic War

* "Liberation" (''The Flash''), a TV episode

* "Liberation" (''K-9''), an episode

Gaming

* '' Liberati ...

of peoples from all forms of colonialism

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their reli ...

and foreign domination, and the right of nations to self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a '' jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It sta ...

. Therefore, socialists have often aligned themselves politically with anti-colonial independence movements, and actively opposed the exploitation of one country by another.

Since war is understood in socialist theory to be a general product of the laws of economic competition inherent to capitalism (i.e., competition between capitalists and their respective national governments for natural resources and economic dominance), liberal ideologies which promote international capitalism and "free trade", even if they sometimes speak in positive terms of international cooperation, are, from the socialist standpoint, rooted in the very economic forces which drive world conflict. In socialist theory, world peace can only come once economic competition has been ended and class divisions within society have ceased to exist. This idea was expressed in 1848 by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in ''The Communist Manifesto'':

In proportion as the exploitation of one individual by another will also be put an end to, the exploitation of one nation by another will also be put an end to. In proportion as the antagonism between classes within the nation vanishes, the hostility of one nation to another will come to an end.The idea was reiterated later by Lenin and advanced as the official policy of the

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

party during World War I:

Socialists have always condemned war between nations as barbarous and brutal. But our attitude towards war is fundamentally different from that of the bourgeois pacifists (supporters and advocates of peace) and of the Anarchists. We differ from the former in that we understand the inevitable connection between wars and the class struggle within the country; we understand that war cannot be abolished unless classes are abolished and Socialism is created.

International Workingmen's Association

The

The International Workingmen's Association

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA), often called the First International (1864–1876), was an international organisation which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, communist and anarchist groups and trad ...

, or First International, was an organization founded in 1864, composed of various working class radicals and trade unionists who promoted an ideology of internationalist socialism and anti-imperialism. Figures such as Karl Marx and anarchist revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary s ...

would play prominent roles in the First International. The ''Inaugural Address of the First International'', written by Marx in October 1864 and distributed as a pamphlet, contained calls for international cooperation between working people, and condemnations of the imperialist policies of national aggression undertaken by the governments of Europe:

If the emancipation of the working classes requires their fraternal concurrence, how are they to fulfill that great mission with a foreign policy in pursuit of criminal designs, playing upon national prejudices, and squandering in piratical wars the people’s blood and treasure?By the mid-1870s, splits within the International over tactical and ideological questions would lead to the organization's demise and pave the way for the formation of the

Second International

The Second International (1889–1916) was an organisation of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second Internatio ...

in 1889. One faction, with Marx as the figurehead, argued that workers and radicals must work within parliaments in order to win political supremacy and create a worker's government. The other major faction were the anarchists, led by Bakunin, who saw all state institutions as inherently oppressive, and thus opposed any parliamentary activity and believed that workers action should be aimed at the total destruction of the state.

Socialist International

The Socialist International, known as the Second International, was founded in 1889 after the disintegration of the International Workingmen's Association. Unlike the First International, it was a federation of socialist political parties from various countries, including both reformist and revolutionary groupings. The parties of the Second International were the first socialist parties to win mass support among the working class and have representatives elected to parliaments. These parties, such as the German Social-Democratic Labor Party, were the first socialist parties in history to emerge as serious political players on the parliamentary stage, often gaining millions of members. Ostensibly committed to peace and anti-imperialism, the International Socialist Congress held its final meeting in Basel, Switzerland in 1912, in anticipation of the outbreak of World War I. The manifesto adopted at the Congress outlined the Second International's opposition to the war and its commitment to a speedy and peaceful resolution:If a war threatens to break out, it is the duty of the working classes and their parliamentary representatives in the countries involved supported by the coordinating activity of the International Socialist Bureau to exert every effort in order to prevent the outbreak of war by the means they consider most effective, which naturally vary according to the sharpening of the class struggle and the sharpening of the general political situation. In case war should break out anyway it is their duty to intervene in favor of its speedy termination and with all their powers to utilize the economic and political crisis created by the war to arouse the people and thereby to hasten the downfall of capitalist class rule.Despite this, when the war began in 1914, the majority of the Socialist parties of the International turned on each other and sided with their respective governments in the war effort, betraying their internationalist values and leading to the dissolution of the Second International. This betrayal led the few anti-war delegates left within the Second International to organize the International Socialist Conference at Zimmerwald, Switzerland in 1915. Known as the Zimmerwald Conference, its purpose was to formulate a platform of opposition to the war. The conference was unable to reach agreement on all points, but ultimately was able to publish the Zimmerwald Manifesto, which was drafted by Leon Trotsky. The most left-wing and stringently internationalist delegates at the conference were organized around Lenin and the Russian Social Democrats, and known as the Zimmerwald Left. They bitterly condemned the war and what they described as the hypocritical "social-chauvinists" of the Second International, who so quickly abandoned their internationalist principles and refused to oppose the war. The Zimmerwald Left resolutions urged all socialists who were committed to the internationalist principles of socialism to struggle against the war and commit to international workers' revolution. The perceived betrayal of the social-democrats and the organization of the Zimmerwald Left would ultimately set the stage for the emergence of the world's first modern communist parties and the formation of the Third International in 1919.

Communist International

Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

, the end of the first World War, and the dissolution of the Second International. It was an association of communist political parties from throughout the world dedicated to proletarian internationalism and the revolutionary overthrow of the world bourgeoisie. The ''Manifesto of the Communist International'', written by Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

, describes the political orientation of the Comintern as "against imperialist barbarism, against monarchy, against the privileged estates, against the bourgeois state and bourgeois property, against all kinds and forms of class or national oppression".

Fourth International

The fourth and last socialist international was founded by Leon Trotsky and his followers in 1938 in opposition to the Third International and the direction taken by the USSR under the leadership of Joseph Stalin. The Fourth International declared itself to be the true ideological successor of the original Comintern under Lenin, carrying on the banner of proletarian internationalism which had been abandoned by Stalin's Comintern. A variety of still active left-wing political organizations claim to be the contemporary successors of Trotsky's original Fourth International.Internationalism in practise

The4th World Congress of the Communist International

The 4th World Congress of the Communist International was an assembly of delegates to the Communist International held in Petrograd and Moscow, Soviet Russia, between November 5 and December 5, 1922. A total of 343 voting delegates from 58 coun ...

established the legal framework for internationalist collaboration and the foundation of agricultural and industrial communes within the USSR. Up until World War II, between seventy to eighty thousand internationalist-minded workers moved to the Soviet Union from abroad. The call for internationalist solidarity attracted settlers from countries such as Austria, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Estonia, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Uruguay and the United States. One of first communes was formed by 123 workers of the Ford Motor Company’s Highland Park factory. Led by the Detroit-based engineer Arthur Adams (1885–1969) the cooperative arrived in 1921 to set up the first automobile plant of the USSR ( Likhachev Plant) in the vicinity of Moscow. While most communes were short-lived and disbanded by 1927, others such as Interhelpo, an internationalist commune founded 1923 by Ido-speakers in Czechoslovakia, played an important role in the industrialization and urbanization of Soviet Central Asia

Soviet Central Asia (russian: link=no, Советская Средняя Азия, Sovetskaya Srednyaya Aziya) was the part of Central Asia administered by the Soviet Union between 1918 and 1991, when the Central Asian republics declared ind ...

. By 1932, the Frunze-based cooperative comprised members from 14 different ethnicities who had developed an organic pathwork working language referred to as "spontánne esperanto". Being a product of the New Economic Policy

The New Economic Policy (NEP) () was an economic policy of the Soviet Union proposed by Vladimir Lenin in 1921 as a temporary expedient. Lenin characterized the NEP in 1922 as an economic system that would include "a free market and capitalism, ...

, after Stalin's Great Break most internationalist communes operating in the USSR were either shut down or collectivized.

Modern expression

Internationalism is most commonly expressed as an appreciation for the diverse cultures in the world, and a desire for world peace. People who express this view believe in not only being a citizen of their respective countries, but of being a citizen of the world. Internationalists feel obliged to assist the world through leadership and charity. Internationalists also advocate the presence of international organizations, such as theUnited Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

, and often support a stronger form of a world government.

Contributors to the current version of internationalism include Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theor ...

, who was a socialist and believed in a world government, and classified the follies of nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

as "an infantile sickness". Conversely, other internationalists such as Christian Lange and Rebecca West

Dame Cicily Isabel Fairfield (21 December 1892 – 15 March 1983), known as Rebecca West, or Dame Rebecca West, was a British author, journalist, literary critic and travel writer. An author who wrote in many genres, West reviewed books ...

saw little conflict between holding nationalist and internationalist positions.

International organizations and internationalism

For both intergovernmental organizations and international non-governmental organizations to emerge, nations and peoples had to be strongly aware that they shared certain interests and objectives across national boundaries and they could best solve their many problems by pooling their resources and effecting transnational cooperation, rather than through individual countries' unilateral efforts. Such a view, such global consciousness, may be termed internationalism, the idea that nations and peoples should cooperate instead of preoccupying themselves with their respective national interests or pursuing uncoordinated approaches to promote them.Sovereign states vs. supranational powers balance

In the strict meaning of the word, internationalism is still based on the existence ofsovereign state

A sovereign state or sovereign country, is a political entity represented by one central government that has supreme legitimate authority over territory. International law defines sovereign states as having a permanent population, defined ter ...

. Its aims are to encourage multilateralism (world leadership not held by any single country) and create some formal and informal interdependence between countries, with some limited supranational powers given to international organisation

An international organization or international organisation (see spelling differences), also known as an intergovernmental organization or an international institution, is a stable set of norms and rules meant to govern the behavior of states an ...

s controlled by those nations via intergovernmental treaties and institutions.

The ideal of many internationalists, among them world citizens, is to go a step further towards democratic globalization by creating a world government

World government is the concept of a single political authority with jurisdiction over all humanity. It is conceived in a variety of forms, from tyrannical to democratic, which reflects its wide array of proponents and detractors.

A world gove ...

. However, this idea is opposed and/or thwarted by other internationalists, who believe any world government body would be inherently too powerful to be trusted, or because they dislike the path taken by supranational entities such as the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

or a union of states such as the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

and fear that a world government inclined towards fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and t ...

would emerge from the former. These internationalists are more likely to support a loose world federation

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government ( federalism). In a federation, the self-gover ...

in which most power resides with national governments or sub-national governments.

Literature and criticism

InJacques Derrida

Jacques Derrida (; ; born Jackie Élie Derrida; See also . 15 July 1930 – 9 October 2004) was an Algerian-born French philosopher. He developed the philosophy of deconstruction, which he utilized in numerous texts, and which was developed th ...

's 1993 work, '' Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International'', he uses Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

'' to frame a discussion of the history of the International, ultimately proposing his own vision for a "New International" that is less reliant on large-scale international organizations. As he puts it, the New International should be "without status ... without coordination, without party, without country, without national community, without co-citizenship, without common belonging to a class."

Through Derrida's use of ''Hamlet'', he shows the influence that Shakespeare had on Marx and Engel's work on internationalism. In his essay, "Big Leagues: Specters of Milton and Republican International Justice between Shakespeare and Marx", Christopher N. Warren makes the case that English poet John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet and intellectual. His 1667 epic poem ''Paradise Lost'', written in blank verse and including over ten chapters, was written in a time of immense religious flux and politica ...

also had a substantial influence on Marx and Engel's work. ''Paradise Lost'', in particular, shows “the possibility of political actions oriented toward international justice founded outside the aristocratic order.”Warren, Christopher N (2016). �Big Leagues: Specters of Milton and Republican International Justice between Shakespeare and Marx

” ''Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development'', Vol. 7. Pg. 380. Marx and Engels, Warren claims, understood the empowering potential of Miltonic republican traditions for forging international coalitions—a lesson, perhaps, for “The New International.”

Other uses

* In a less restricted sense, ''internationalism'' is a word describing the impetus and motivation for the creation of any international organizations. The earliest such example of broad internationalism would be the drive to replace feudal systems of measurement with themetric system

The metric system is a system of measurement that succeeded the decimalised system based on the metre that had been introduced in France in the 1790s. The historical development of these systems culminated in the definition of the Intern ...

, long before the creation of international organizations like the World Court, the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

and the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

.

* In linguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Ling ...

, an ''internationalism'' is a loanword

A loanword (also loan word or loan-word) is a word at least partly assimilated from one language (the donor language) into another language. This is in contrast to cognates, which are words in two or more languages that are similar because ...

that, originating in one language, has been borrowed by most other languages. Examples of such borrowings include ''OK'', ''microscope

A microscope () is a laboratory instrument used to examine objects that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Microscopy is the science of investigating small objects and structures using a microscope. Microscopic means being invisi ...

'' and '' tokamak''.

See also

*Anti-globalization movement

The anti-globalization movement or counter-globalization movement, is a social movement critical of economic globalization. The movement is also commonly referred to as the global justice movement, alter-globalization movement, anti-globalist m ...

* Anti-imperialism

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is a term used in a variety of contexts, usually by nationalist movements who want to secede from a larger polity (usually in the form of an empire, but also in a multi-ethnic ...

* Bahá'í International Community

* Communist International

* Cosmopolitanism

Cosmopolitanism is the idea that all human beings are members of a single community. Its adherents are known as cosmopolitan or cosmopolite. Cosmopolitanism is both prescriptive and aspirational, believing humans can and should be " world citizen ...

* Cross-culturalism

* Democratic globalization

* Fourth International

* Global Citizens Movement

* Global justice

* Global village

* Globalisation

Globalization, or globalisation (Commonwealth English; see spelling differences), is the process of interaction and integration among people, companies, and governments worldwide. The term ''globalization'' first appeared in the early 20t ...

* International community

The international community is an imprecise phrase used in geopolitics and international relations to refer to a broad group of people and governments of the world.

As a rhetorical term

Aside from its use as a general descriptor, the term is t ...

* International Workingmen's Association

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA), often called the First International (1864–1876), was an international organisation which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, communist and anarchist groups and trad ...

* "Yank" Levy

Bert "Yank" Levy (October 5, 1897September 2, 1965) was a Canadian soldier, socialist, military instructor and author/pamphleteer of one of the first manuals on guerrilla warfare, which was widely circulated with more than a half million publish ...

* Multilateralism

* Neoconservatism

Neoconservatism is a political movement that began in the United States during the 1960s among liberal hawks who became disenchanted with the increasingly pacifist foreign policy of the Democratic Party and with the growing New Left and co ...

* New Internationalist

* Pan-Islamism

Pan-Islamism ( ar, الوحدة الإسلامية) is a political movement advocating the unity of Muslims under one Islamic country or state – often a caliphate – or an international organization with Islamic principles. Pan-Islamism wa ...

* Second International

The Second International (1889–1916) was an organisation of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second Internatio ...

* Transnationalism

Transnationalism is a research field and social phenomenon grown out of the heightened interconnectivity between people and the receding economic and social significance of boundaries among nation states.

Overview

The term "trans-national" was ...

* World communism

World communism, also known as global communism, is the ultimate form of communism which of necessity has a universal or global scope. The long-term goal of world communism is an unlimited worldwide communist society that is classless (lacking ...

* World community

References

Further reading

* * * * Warren, Christopher (2016). �Big Leagues: Specters of Milton and Republican International Justice between Shakespeare and Marx.

�� ''Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development'', Vol. 7.

External links

''Pop Internationalism'' by Paul Krugman

''Internationalism on Facebook''

{{Authority control Anarchism Anti-nationalism Communism Human migration Islamism Nationalism Politics and race Socialism World government Political movements