History of the Huns on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the

The Huns' sudden appearance in the written sources suggests that the Huns crossed the

The Huns' sudden appearance in the written sources suggests that the Huns crossed the  The Huns first invaded the land of the

The Huns first invaded the land of the  After Vithimiris's death, most Greuthungi submitted themselves to the Huns: they retained their own king, named Hunimund, whose name means "protégé of the Huns". Those who decided to resist marched to the

After Vithimiris's death, most Greuthungi submitted themselves to the Huns: they retained their own king, named Hunimund, whose name means "protégé of the Huns". Those who decided to resist marched to the

After Ruga's death, his nephews

After Ruga's death, his nephews

Bleda died some time between 442 and 447, with the most likely years being 444 or 445. He appears to have been murdered by Attila. Following Bleda's death, a tribe known as the

Bleda died some time between 442 and 447, with the most likely years being 444 or 445. He appears to have been murdered by Attila. Following Bleda's death, a tribe known as the

In spring of 451, Attila invaded

In spring of 451, Attila invaded

Upon his return to Pannonia, Attila ordered the launching of raids into Illyricum to encourage the Eastern Roman Empire to resume its tribute. Rather than attacking the Eastern Empire, however, in 452 he invaded Italy. The precise reasons for this are unclear: the ''Chronicle of 452'' claims that it was due to his anger at his defeat in Gaul the previous year. The Huns crossed the

Upon his return to Pannonia, Attila ordered the launching of raids into Illyricum to encourage the Eastern Roman Empire to resume its tribute. Rather than attacking the Eastern Empire, however, in 452 he invaded Italy. The precise reasons for this are unclear: the ''Chronicle of 452'' claims that it was due to his anger at his defeat in Gaul the previous year. The Huns crossed the

In 453, Attila was reportedly planning a major campaign against the Eastern Romans to force them to resume paying tribute. However, he died unexpectedly, reportedly of a hemorrhage during his wedding to a new bride. He may also have been planning an invasion of the

In 453, Attila was reportedly planning a major campaign against the Eastern Romans to force them to resume paying tribute. However, he died unexpectedly, reportedly of a hemorrhage during his wedding to a new bride. He may also have been planning an invasion of the

Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

spans the time from before their first secure recorded appearance in Europe around 370 AD to after the disintegration of their empire around 469. The Huns likely entered Western Asia shortly before 370 from Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the fo ...

: they first conquered the Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Euro ...

and the Alans

The Alans (Latin: ''Alani'') were an ancient and medieval Iranian nomadic pastoral people of the North Caucasus – generally regarded as part of the Sarmatians, and possibly related to the Massagetae. Modern historians have connected the A ...

, pushing a number of tribes to seek refuge within the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

. In the following years, the Huns conquered most of the Germanic and Scythian

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Centra ...

barbarian tribes outside of the borders of the Roman Empire. They also launched invasions of both the Asian provinces of Rome and the Sasanian Empire

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

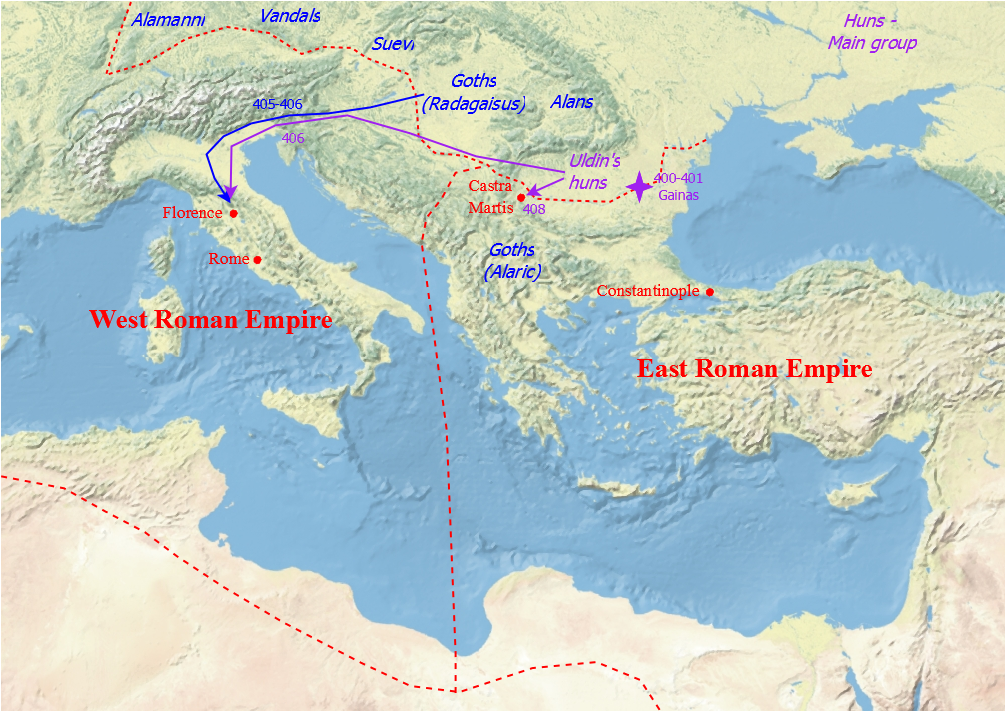

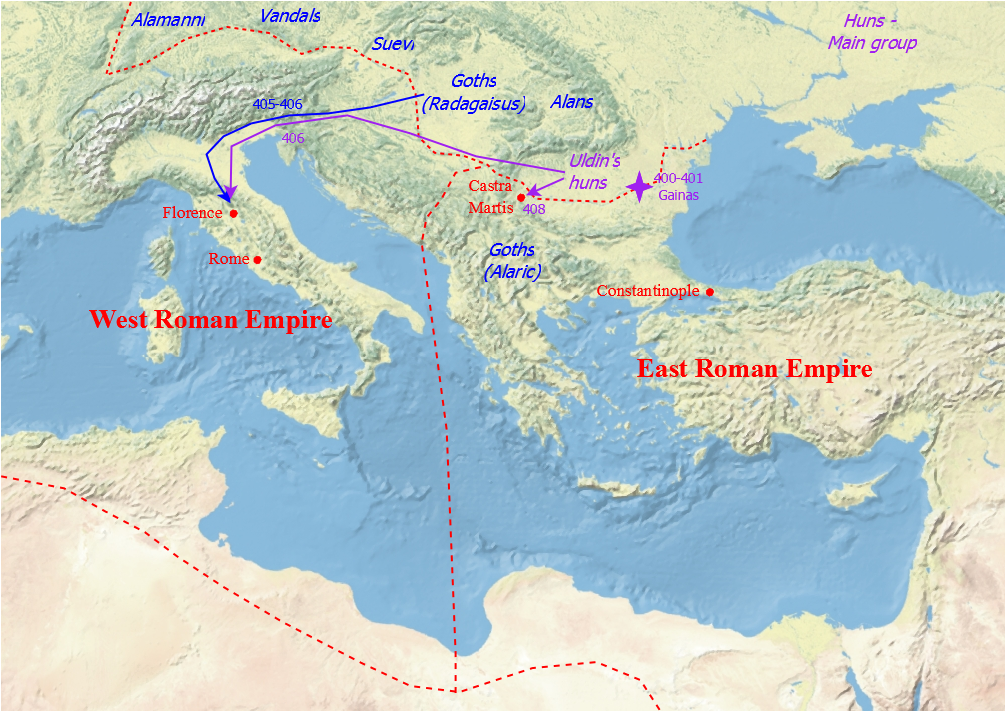

in 375. Under Uldin

Uldin, also spelled Huldin (died before 412) is the first ruler of the Huns whose historicity is undisputed.

Etymology

The name is recorded as ''Ουλδης'' (Ouldes) by Sozomen, ''Uldin'' by Orosius, and ''Huldin'' by Marcellinus Comes. On th ...

, the first Hunnic ruler named in contemporary sources, the Huns launched a first unsuccessful large-scale raid into the Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantino ...

in Europe in 408. From the 420s, the Huns were led by the brothers Octar and Ruga, who both cooperated with and threatened the Romans. Upon Ruga's death in 435, his nephews Bleda

Bleda () was a Hunnic ruler, the brother of Attila the Hun.

As nephews to Rugila, Attila and his elder brother Bleda succeeded him to the throne. Bleda's reign lasted for eleven years until his death. While it has been speculated by Jordanes t ...

and Attila

Attila (, ; ), frequently called Attila the Hun, was the ruler of the Huns from 434 until his death in March 453. He was also the leader of a tribal empire consisting of Huns, Ostrogoths, Alans, and Bulgars, among others, in Central and E ...

became the new rulers of the Huns, and launched a successful raid into the Eastern Roman Empire before making peace and securing an annual tribute and trading raids under the Treaty of Margus

The Treaty of Margus was a treaty between the Huns and the Roman Empire, signed in Margus, Moesia Superior (modern-day Požarevac, Serbia). It was signed by Roman consul Flavius Plintha in 435. Among other stipulations, the treaty doubled the ann ...

. Attila appears to have killed his brother and became sole ruler of the Huns in 445. He would go on to rule for the next eight years, launching a devastating raid on the Eastern Roman Empire in 447, followed by an invasion of Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

in 451. Attila is traditionally held to have been defeated in Gaul at the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields

The Battle of the Catalaunian Plains (or Fields), also called the Battle of the Campus Mauriacus, Battle of Châlons, Battle of Troyes or the Battle of Maurica, took place on June 20, 451 AD, between a coalition – led by the Roman general ...

, however some scholars hold the battle to have been a draw or Hunnic victory. The following year, the Huns invaded Italy and encountered no serious resistance before turning back.

Hunnic dominion over Barbarian Europe is traditionally held to have collapsed suddenly after the death of Attila the year after the invasion of Italy. The Huns themselves are usually thought to have disappeared after the death of his son Dengizich

Dengizich (died in 469), was a Hunnic ruler and son of Attila. After Attila's death in 453 AD, his Empire crumbled and its remains were ruled by his three sons, Ellac, Dengizich and Ernak. He succeeded his older brother Ellac in 454 AD, and prob ...

in 469. However, some scholars have argued that the Bulgars

The Bulgars (also Bulghars, Bulgari, Bolgars, Bolghars, Bolgari, Proto-Bulgarians) were Turkic semi-nomadic warrior tribes that flourished in the Pontic–Caspian steppe and the Volga region during the 7th century. They became known as noma ...

in particular show a high degree of continuity with the Huns. Hyun Jin Kim

Hyun Jin Kim (born 1982) is an Australian academic, scholar and author.

He was born in Seoul and raised in Auckland, New Zealand. Kim got his Doctor of Philosophy degree from the University of Oxford. He started learning Latin, German, and Fren ...

has argued that the three major Germanic tribes to emerge from the Hunnic empire, the Gepids

The Gepids, ( la, Gepidae, Gipedae, grc, Γήπαιδες) were an East Germanic tribe who lived in the area of modern Romania, Hungary and Serbia, roughly between the Tisza, Sava and Carpathian Mountains. They were said to share the relig ...

, the Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths ( la, Ostrogothi, Austrogothi) were a Roman-era Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the large Gothic populations who ...

, and the Sciri

The Sciri, or Scirians, were a Germanic people. They are believed to have spoken an East Germanic language. Their name probably means "the pure ones".

The Sciri were mentioned already in the late 3rd century BC as participants in a raid on th ...

, were all heavily Hunnicized, and may have had Hunnic rather than native rulers even after the end of Hunnic dominion in Europe.

It is possible that the Huns were directly or indirectly responsible for the fall of the Western Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its va ...

, and they have been directly or indirectly linked to the dominance of Turkic tribes on the Eurasian steppe

The Eurasian Steppe, also simply called the Great Steppe or the steppes, is the vast steppe ecoregion of Eurasia in the temperate grasslands, savannas and shrublands biome. It stretches through Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova and Transnistr ...

following the fourth century.

Potential history prior to 370

The 2nd century AD geographerPtolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

mentioned a people called Χοῦνοι ''Khunnoi'', when listing the peoples of the west Eurasian steppe. (In the Koine Greek

Koine Greek (; Koine el, ἡ κοινὴ διάλεκτος, hē koinè diálektos, the common dialect; ), also known as Hellenistic Greek, common Attic, the Alexandrian dialect, Biblical Greek or New Testament Greek, was the common supra-reg ...

used by Ptolemy, Χ generally denoted a voiceless velar fricative

The voiceless velar fricative is a type of consonantal sound used in some spoken languages. It was part of the consonant inventory of Old English and can still be found in some dialects of English, most notably in Scottish English, e.g. in ''loc ...

sound; hence contemporary Western Roman authors Latinised the name as ''Chuni'' or ''Chunni''.) The ''Khunnoi'' lived "between the Bastarnae

The Bastarnae ( Latin variants: ''Bastarni'', or ''Basternae''; grc, Βαστάρναι or Βαστέρναι) and Peucini ( grc, Πευκῖνοι) were two ancient peoples who between 200 BC and 300 AD inhabited areas north of the Roman front ...

and the Roxolani

The Roxolani or Rhoxolāni ( grc, Ροξολανοι , ; la, Rhoxolānī) were a Sarmatian people documented between the 2nd century BC and the 4th century AD, first east of the Borysthenes (Dnieper) on the coast of Lake Maeotis ( Sea of Azov), ...

", according to Ptolemy. However, modern scholars such as E. A. Thompson have claimed that the similarity of the ethnonyms ''Khunnoi'' and Hun were coincidental. Maenchen-Helfen and Denis Sinor also dispute the association of the ''Khunnoi'' with Attila's Huns. However, Maenchen-Helfen concedes that Ammianus Marcellinus referred to Ptolemy's report of the ''Khunnoi'', when stating that the Huns were "mentioned only cursorily" by previous writers.Ammianus 32.2

A tribe called the Ουρουγούνδοι ''Ourougoúndoi'' (or ''Urugundi'') who, according to Zosimus, invaded the Roman Empire from north of the Lower Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

in , may have been synonymous with the Βουρουγουνδοι ''Bourougoundoi'', whom Agathias

Agathias or Agathias Scholasticus ( grc-gre, Ἀγαθίας σχολαστικός; Martindale, Jones & Morris (1992), pp. 23–25582/594), of Myrina (Mysia), an Aeolian city in western Asia Minor (Turkey), was a Greek poet and the principal histo ...

(6th century) listed among the Hunnish tribes. Other scholars have regarded both names as referring to a Germanic tribe, the Burgundi

The Burgundians ( la, Burgundes, Burgundiōnes, Burgundī; on, Burgundar; ang, Burgendas; grc-gre, Βούργουνδοι) were an early Germanic tribe or group of tribes. They appeared in the middle Rhine region, near the Roman Empire, and ...

(Burgundians), although this identification was rejected by Maenchen-Helfen (who speculated that one or both names may have approximated an early Turkic ethnonym, such as "''Vurugundi''").

Early history

First conquests

The Huns' sudden appearance in the written sources suggests that the Huns crossed the

The Huns' sudden appearance in the written sources suggests that the Huns crossed the Volga River

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catch ...

from the east not much earlier. The reasons for the Huns' sudden attack on the neighboring peoples are unknown. One possible reason may have been climate change, however, Peter Heather notes that in the absence of reliable data this is unprovable. As a second possibility, Heather suggests some other nomadic group may have pushed them westward. Peter Golden suggests that the Huns may have been pushed west by the Jou-jan. A third possibility may have been a desire to increase their wealth by coming closer to the wealthy Roman Empire.

The Romans became aware of the Huns when the latter's invasion of the Pontic steppes forced thousands of Goths to move to the Lower Danube to seek refuge in the Roman Empire in 376, according to the contemporaneous Ammianus Marcellinus. There are also some indications that the Huns were already raiding Transcaucasia

The South Caucasus, also known as Transcaucasia or the Transcaucasus, is a geographical region on the border of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, straddling the southern Caucasus Mountains. The South Caucasus roughly corresponds to modern Arme ...

in the 360s and 370s. These raids eventually forced the Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantino ...

and Sasanian Empire

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

to jointly defend the passes through the Caucasus mountains.

The Huns first invaded the land of the

The Huns first invaded the land of the Alans

The Alans (Latin: ''Alani'') were an ancient and medieval Iranian nomadic pastoral people of the North Caucasus – generally regarded as part of the Sarmatians, and possibly related to the Massagetae. Modern historians have connected the A ...

, which was located to the east of the Don River

The Don ( rus, Дон, p=don) is the fifth-longest river in Europe. Flowing from Central Russia to the Sea of Azov in Southern Russia, it is one of Russia's largest rivers and played an important role for traders from the Byzantine Empire.

Its ...

, defeating them and forcing the survivors to submit themselves to them or to flee across the Don. Maenchen-Helfen believes that rather than a direct conquest, the Huns instead allied themselves with groups of Alans. Writing much later, the historian Jordanes

Jordanes (), also written as Jordanis or Jornandes, was a 6th-century Eastern Roman bureaucrat widely believed to be of Gothic descent who became a historian later in life. Late in life he wrote two works, one on Roman history ('' Romana'') an ...

mentioned that the Huns also conquered "the Alpidzuri, the Alcildzuri, Itimari, Tuncarsi, and Boisci" in a battle by the Maeotian Swamp

The Maeotian Swamp or Maeotian Marshes ( grc, ἡ Μαιῶτις λίμνη, ''hē Maiōtis límnē'', literally ''Maeotian Lake''; la, Palus Maeotis) was a name applied in antiquity variously to the swamps at the mouth of the Tanais River in Scy ...

. These were potentially Turkic-speaking nomadic tribes who are later mentioned living under the Huns along the Danube.

Jordanes claimed that the Huns at this time were led by a king Balamber

Balamber (also known as Balamir, Balamur and many other variants) was ostensibly a chieftain of the Huns, mentioned by Jordanes in his ''Getica'' ( 550 AD). Jordanes simply called him "king of the Huns" () and writes the story of Balamber crushin ...

. E. A. Thompson doubts that such a figure ever existed, but argues that "they were operating ..with a much larger force than any one of their tribes could have put to the field". Hyun Jin Kim argues that Jordanes has invented Balamber on the basis of the 5th century figure Valamer

Valamir or Valamer (c. 420 – 469) was an Ostrogothic king in the former Roman province of Pannonia from AD 447 until his death. During his reign, he fought alongside the Huns against the Roman Empire and then, after Attila the Hun's death, fo ...

. However, Maenchen-Helfen credits that Balamber was a historic king, and Denis Sinor suggests that "Balamber was merely the leader of a tribe or an ''ad hoc'' group of warriors".

After they subjugated the Alans, the Huns and their Alan auxiliaries started plundering the wealthy settlements of the Greuthungi

The Greuthungi (also spelled Greutungi) were a Gothic people who lived on the Pontic steppe between the Dniester and Don rivers in what is now Ukraine, in the 3rd and the 4th centuries. They had close contacts with the Tervingi, another Gothic ...

, or eastern Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Euro ...

, to the west of the Don. Maenchen-Helfen suggests that it was as a result of their new alliance with these Alans that the Huns were able to threaten the Goths. The Greuthungic king, Ermanaric

Ermanaric; la, Ermanaricus or ''Hermanaricus''; ang, Eormanrīc ; on, Jǫrmunrekkr , gmh, Ermenrîch (died 376) was a Greuthungian Gothic king who before the Hunnic invasion evidently ruled a sizable portion of Oium, the part of Scythi ...

, resisted for a while, but finally "he found release from his fears by taking his own life", according to Ammianus Marcellinus. Marcellinus's report refers either to Ermanaric's suicide or to his ritual sacrifice

Sacrifice is the offering of material possessions or the lives of animals or humans to a deity as an act of propitiation or worship. Evidence of ritual animal sacrifice has been seen at least since ancient Hebrews and Greeks, and possibly exis ...

. His great-nephew, Vithimiris, succeeded him. According to Ammianus, Vithimiris hired Huns to fight against the Alans who invaded the Greuthungi's land, but he was killed in a battle. Kim suggests that Ammianus has muddled events: the Alans, fleeing the Huns, likely attacked the Goths, who then called upon the Huns for aid. The Huns, having dealt with the Alans, "probably then in Machiavellian fashion fell upon the weakened Greuthungi Goths and conquered them as well".

After Vithimiris's death, most Greuthungi submitted themselves to the Huns: they retained their own king, named Hunimund, whose name means "protégé of the Huns". Those who decided to resist marched to the

After Vithimiris's death, most Greuthungi submitted themselves to the Huns: they retained their own king, named Hunimund, whose name means "protégé of the Huns". Those who decided to resist marched to the Dniester River

The Dniester, ; rus, Дне́стр, links=1, Dnéstr, ˈdⁿʲestr; ro, Nistru; grc, Τύρᾱς, Tyrās, ; la, Tyrās, la, Danaster, label=none, ) ( ,) is a transboundary river in Eastern Europe. It runs first through Ukraine and t ...

which was the border between the lands of the Greuthungi and the Thervingi

The Thervingi, Tervingi, or Teruingi (sometimes pluralised Tervings or Thervings) were a Gothic people of the plains north of the Lower Danube and west of the Dniester River in the 3rd and the 4th centuries.

They had close contacts with the G ...

, or western Goths. They were under the command of Alatheus

Alatheus and Saphrax were Greuthungi chieftains who served as co-regents for Vithericus, son and heir of the Gothic king Vithimiris.

Alatheus

Alatheus ( 376–387) was a chieftain of the Greuthungi. He fought during the Huns, Hunnish invasion of 3 ...

and Saphrax, because Vithimiris's son, Viderichus, was a child. Athanaric

Athanaric or Atanaric ( la, Athanaricus; died 381) was king of several branches of the Thervingian Goths () for at least two decades in the 4th century. Throughout his reign, Athanaric was faced with invasions by the Roman Empire, the Huns and a c ...

, the leader of the Thervingi, met the refugees along the Dniester at the head of his troops. However, a Hun army bypassed the Goths and attacked them from the rear, forcing Athanaric to retreat towards the Carpathian Mountains

The Carpathian Mountains or Carpathians () are a range of mountains forming an arc across Central Europe. Roughly long, it is the third-longest European mountain range after the Urals at and the Scandinavian Mountains at . The range stretche ...

. Athanaric wanted to fortify the borders, but Hun raids into the land west of the Dniester continued.

Most Thervingi realized that they could not resist the Huns. They went to the Lower Danube, requesting asylum in the Roman Empire. The still resisting Greuthingi under the leadership of Alatheus and Saphrax also marched to the river. Most Roman troops had been transferred from the Balkan Peninsula

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

to fight against the Sassanid Empire

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the History of Iran, last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th cen ...

in Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''O ...

. Emperor Valens

Valens ( grc-gre, Ουάλης, Ouálēs; 328 – 9 August 378) was Roman emperor from 364 to 378. Following a largely unremarkable military career, he was named co-emperor by his elder brother Valentinian I, who gave him the eastern half of ...

permitted the Thervingi to cross the Lower Danube and to settle in the Roman Empire in the autumn of 376. The Thervingi were followed by the Greuthingi, and also by the Taifali

The Taifals or Tayfals ( la, Taifali, Taifalae or ''Theifali''; french: Taïfales) were a people group of Germanic or Sarmatian origin, first documented north of the lower Danube in the mid third century AD. They experienced an unsettled and fra ...

and "other tribes that formerly dwelt with the Goths and Taifali" to the north of the Lower Danube, according to Zosimus. Food shortage and abuse stirred the Goths to revolt in early 377. The ensuing war between the Goths and the Romans lasted for more than five years.

First encounters with Rome

During the Gothic War, the Goths appear to have allied with a group of Huns and Alans, who crossed the Danube and forced the Romans to allow the Goths to advance further into Thrace. The Huns are mentioned intermittently among their allies until 380, after which they apparently returned beyond the Danube. Additionally, in 381, theSciri

The Sciri, or Scirians, were a Germanic people. They are believed to have spoken an East Germanic language. Their name probably means "the pure ones".

The Sciri were mentioned already in the late 3rd century BC as participants in a raid on th ...

and Carpi, together with at least some Huns, launched an unsuccessful attack upon Pannonia

Pannonia (, ) was a province of the Roman Empire bounded on the north and east by the Danube, coterminous westward with Noricum and upper Italy, and southward with Dalmatia and upper Moesia. Pannonia was located in the territory that is now west ...

. Once Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius I

Theodosius I ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος ; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also called Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two ...

made peace with the Goths in 382, the historian Eunapius

Eunapius ( el, Εὐνάπιος; fl. 4th–5th century AD) was a Greek sophist and historian of the 4th century AD. His principal surviving work is the ''Lives of Philosophers and Sophists'' ( grc-gre, Βίοι Φιλοσόφων καὶ Σ� ...

claims that he gave them land and cattle in order to form "an unconquerable bulwark against the inroads of the Huns." After this, the Huns are recorded to have launched a raid into Scythia Minor

Scythia Minor or Lesser Scythia (Greek: , ) was a Roman province in late antiquity, corresponding to the lands between the Danube and the Black Sea, today's Dobruja divided between Romania and Bulgaria. It was detached from Moesia Inferior by th ...

in 384 or 385. Soon afterwards, in 386, a group of Greuthungi under Odotheus Odotheus (in Zosimus ''Aedotheus'') was a Greuthungi king who in 386 led an incursion into the Roman Empire. He was defeated and killed by the Roman general Promotus. His surviving people settled in Phrygia.

Invasion of Roman Empire

After the ...

fled the Huns into Thrace, followed by several attempts by the Sarmatians

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th cen ...

. This is the last serious migration into Roman territory until after the end of Hun rule, and Kim suggests that this indicates that the Huns were securely in control of the tribes beyond Rome at this time.

Otto Maenchen-Helfen and E. A. Thompson argue that the Huns appear to have already been in possession of large parts of Pannonia (the Hungarian plain) as early as 384. Denis Sinor suggests that they may have been settled there as foederati

''Foederati'' (, singular: ''foederatus'' ) were peoples and cities bound by a treaty, known as ''foedus'', with Rome. During the Roman Republic, the term identified the ''socii'', but during the Roman Empire, it was used to describe foreign stat ...

of the Romans rather than as invaders, dating their presence to 380. In 384, the Roman-Frankish general Flavius Bauto

Flavius Bauto (died c. 385) was a Romanised Frank who served as a ''magister militum'' of the Roman Empire and imperial advisor under Valentinian II.

Biography

When the usurper Magnus Maximus invaded Italy in an attempt to replace Valentinian II ...

employed Hunnic mercenaries to defeat the Juthungi

The Juthungi (Greek: ''Iouthungoi'', Latin: ''Iuthungi'') were a Germanic tribe in the region north of the rivers Danube and Altmühl in what is now the modern German state of Bavaria.

The tribe was mentioned by the Roman historians Publius Her ...

tribe attacking from Rhaetia

Raetia ( ; ; also spelled Rhaetia) was a province of the Roman Empire, named after the Rhaetian people. It bordered on the west with the country of the Helvetii, on the east with Noricum, on the north with Vindelicia, on the south-west with ...

. However, the Huns, rather than return to their own country, began to ride to Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

: Bauto was forced to bribe them to turn back. They then attacked the Alamanni

The Alemanni or Alamanni, were a confederation of Germanic tribes

*

*

*

on the Upper Rhine River. First mentioned by Cassius Dio in the context of the campaign of Caracalla of 213, the Alemanni captured the in 260, and later expanded into pre ...

.

Pacatus Drepanius reports that the Huns then fought with Theodosius against the usurper Magnus Maximus

Magnus Maximus (; cy, Macsen Wledig ; died 8 August 388) was Roman emperor of the Western Roman Empire from 383 to 388. He usurped the throne from emperor Gratian in 383 through negotiation with emperor Theodosius I.

He was made emperor in B ...

in 388. In 392, however, the Huns were again involved in raids in the Balkans, together with various other tribes. Some of the Huns seem to have settled in Thrace, and these Huns were then used as auxiliaries by Theodosius in 394; Maenchen-Helfen argues that the Romans may have hoped to use the Huns against the Goths. Kim believes that these mercenaries were not really Huns, but rather non-Hunnic groups capitalizing on the Huns' fearsome reputation as warriors. These Huns were eventually wiped up by the Romans in 401 after they began plundering the territory.

First large scale attack on Rome and Persia

In 395 the Huns began their first large-scale attacks on the Romans. In the summer of that year, the Huns crossed over theCaucasus Mountains

The Caucasus Mountains,

: pronounced

* hy, Կովկասյան լեռներ,

: pronounced

* az, Qafqaz dağları, pronounced

* rus, Кавка́зские го́ры, Kavkázskiye góry, kɐfˈkasːkʲɪje ˈɡorɨ

* tr, Kafkas Dağla ...

, while in the winter of 395, another Hunnic invasion force crossed the frozen Danube, pillaged Thrace, and threatened Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

. Sinor argues that these two events were likely not coordinated, but Kim believes they were. The forces in Asia invaded Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''O ...

, Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, and the Roman provinces in Asia. One group crossed the Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

and was defeated by a Roman army, while two armies, recorded in later sources as under the leadership of Basich and Kursich

Kursich () was a Hun general and royal family member. He led a Hunnish army in the Hunnic invasion of Persia in 395 AD.

The Huns started to seriously threaten the Eastern Roman Empire in 395, crossing over the Caucasus mountains in the summer of ...

, rode down the Euphrates and threatened the Persian capital of Ctesiphon

Ctesiphon ( ; Middle Persian: 𐭲𐭩𐭮𐭯𐭥𐭭 ''tyspwn'' or ''tysfwn''; fa, تیسفون; grc-gre, Κτησιφῶν, ; syr, ܩܛܝܣܦܘܢThomas A. Carlson et al., “Ctesiphon — ܩܛܝܣܦܘܢ ” in The Syriac Gazetteer last modi ...

. One of these armies was defeated by the Persians, while the other successfully retreated by Derbend Pass. A final group of Huns ravaged Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

. The Huns devastated parts of Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

and Cappadocia

Cappadocia or Capadocia (; tr, Kapadokya), is a historical region in Central Anatolia, Turkey. It largely is in the provinces Nevşehir, Kayseri, Aksaray, Kırşehir, Sivas and Niğde.

According to Herodotus, in the time of the Ionian Revo ...

, threatening Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

. The devastation was worse because most Roman forces had been moved to the West due to Roman power struggles there. In 398 Eutropius finally succeeded in gathering an army and restoring order in the province. It seems likely, however, that the Huns left of their own accord without Eutropius having defeated them in battle.

Sinor argues that the much larger scale of the attacks on Asia Minor and Persia indicates that the bulk of the Huns had remained on the Pontic steppes rather than moving into Europe at this time. It seems clear that the Huns did not intend to conquer or settle the territories they attacked, but rather to plunder the provinces, taking, among other things, cattle. Priscus, writing much later, reports hearing from the Huns at Attila's camp that the raid was launched due to a famine on the steppes. This may also have been the reason for the raids into Thrace. Maenchen-Helfen suggests that Basich and Kursich, the Hun leaders responsible for the invasion of Persia, may have come to Rome in 404 or 407 as mercenaries: Priscus records that they came to Rome to make an alliance.

Hunnic attacks against Armenia would continue after this raid, with Armenian sources noting a Hunnic tribe known as the Xailandur as the perpetrators.

Uldin

Uldin

Uldin, also spelled Huldin (died before 412) is the first ruler of the Huns whose historicity is undisputed.

Etymology

The name is recorded as ''Ουλδης'' (Ouldes) by Sozomen, ''Uldin'' by Orosius, and ''Huldin'' by Marcellinus Comes. On th ...

, the first Hun identified by name in contemporary sources, is identified as the leader of the Huns in Muntenia

Muntenia (, also known in English as Greater Wallachia) is a historical region of Romania, part of Wallachia (also, sometimes considered Wallachia proper, as ''Muntenia'', ''Țara Românească'', and the seldom used ''Valahia'' are synonyms in R ...

(modern Romania east of the Olt River) in 400. It is unclear how much territory or how many tribes of Huns Uldin actually controlled, although he clearly controlled parts of Hungary as well as Muntenia. The Romans referred to him as a ''regulus'' (sub-king): he himself boasted of immense power.

In 400, Gainas

Gainas ( Greek: Γαϊνάς) was a Gothic leader who served the Eastern Roman Empire as '' magister militum'' during the reigns of Theodosius I and Arcadius.

Gainas began his military career as a common foot-soldier, but later commanded the ...

, rebellious former Roman ''magister militum'' fled into Uldin's territory with an army of Goths, and Uldin defeated and killed him, likely near Novae

A nova (plural novae or novas) is a transient astronomical event that causes the sudden appearance of a bright, apparently "new" star (hence the name "nova", which is Latin for "new") that slowly fades over weeks or months. Causes of the dramati ...

: he sent Gainas's head to Constantinople. Kim suggests that Uldin was interested in cooperating with the Romans while he expanded his control over Germanic tribes in the West. In 406, Hunnic pressure seems to have caused groups of Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

, Suebi

The Suebi (or Suebians, also spelled Suevi, Suavi) were a large group of Germanic peoples originally from the Elbe river region in what is now Germany and the Czech Republic. In the early Roman era they included many peoples with their own name ...

, and Alans to cross the Rhine into Gaul. Uldin's Huns raided Thrace in 404–405, likely in winter.

Also in 405, a group of Goths under Radagaisus

Radagaisus (died 23 August 406) was a Gothic king who led an invasion of Roman Italy in late 405 and the first half of 406.Peter Heather, ''The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians'', 2nd ed. 2006:194; A committed ...

invaded Italy, with Kim arguing that these Goths originated from Uldin's territory and that they were likely fleeing from some action of his. Stilicho

Flavius Stilicho (; c. 359 – 22 August 408) was a military commander in the Roman army who, for a time, became the most powerful man in the Western Roman Empire. He was of Vandal origins and married to Serena, the niece of emperor Theodosiu ...

, the Roman ''magister militum'' responded by asking for Uldin's aid: Uldin's Huns then destroyed Radagaisus's army near Faesulae

Fiesole () is a town and '' comune'' of the Metropolitan City of Florence in the Italian region of Tuscany, on a scenic height above Florence, 5 km (3 miles) northeast of that city. It has structures dating to Etruscan and Roman times.

Si ...

in modern Tuscany in 406. Kim suggests Uldin acted in order to demonstrate his ability to destroy any groups of barbarians who might flee Hunnic rule. An army of 1000 of Uldin's Huns were also employed by the Eastern Roman Empire to fight against the Goths under Alaric. After Stilicho's death in 408, however, Uldin switched sides and began aiding Alaric under an army under the command of Alaric's brother-in-law Athaulf

Athaulf (also ''Athavulf'', ''Atawulf'', or ''Ataulf'' and ''Adolf'', Latinized as ''Ataulphus'') ( 37015 August 415) was king of the Visigoths from 411 to 415. During his reign, he transformed the Visigothic state from a tribal kingdom to a maj ...

.

Also in 408, the Huns, under Uldin's command, crossed the Danube and captured the important fortress Castra Martis in Moesia

Moesia (; Latin: ''Moesia''; el, Μοισία, Moisía) was an ancient region and later Roman province situated in the Balkans south of the Danube River, which included most of the territory of modern eastern Serbia, Kosovo, north-eastern Alban ...

. The Roman commander in Thrace attempted to make peace with Uldin, but Uldin refused his offers and demanded an extremely high tribute. However, many of Uldin's commanders subsequently defected to the Romans, bribed by the Romans. It appears that most of his army was actually composed by Sciri and Germanic tribes, whom the Romans subsequently sold into slavery. Uldin himself escaped back across the Danube, after which he is not mentioned again. The Romans responded to Uldin's invasions by attempting to strengthen the fortifications at the border, increasing the defenses at Constantinople, and taking other measures to strengthen their defences.

Hunnic mercenaries had also formed Stilicho's bodyguard: Kim suggests they were a gift from Uldin. The guard was either killed with Stilicho, or is the same as an elite unit of 300 Huns who continued to fight for the Romans against Alaric even after Uldin's invasion.

During this same time, probably between 405 and 408, the future Roman ''magister militum'' and opponent of Attila Flavius Aetius

Aetius (also spelled Aëtius; ; 390 – 454) was a Roman general and statesman of the closing period of the Western Roman Empire. He was a military commander and the most influential man in the Empire for two decades (433454). He managed pol ...

was a hostage living among the Huns.

410s

Sources on the Huns after Uldin are scarce. In 412 or 413, the Roman statesman and writerOlympiodorus of Thebes

Olympiodorus of Thebes ( grc-gre, Ὀλυμπιόδωρος ὁ Θηβαῖος; born c. 380, fl. c. 412–425 AD) was a Roman historian, poet, philosopher and diplomat of the early fifth century. He produced a ''History'' in twenty-two volumes, wr ...

was sent on an embassy to "the first of the kings" of the Huns, Charaton

Charaton (Olympiodorus of Thebes: ''Χαράτων'') was one of the first kings of the Huns.

History

In the end of 412 or beginning of 413, Charaton received the Byzantine ambassador Olympiodorus sent by Honorius. Olympiodorus travelled to Cha ...

. Olympiodorus wrote an account of this event, which exists now only fragmentarily. Olympiodorus had been dispatched to appease Charaton after the death of a certain Donatus, who "was unlawfully put to death". Historians such as E. A. Thompson have assumed that Donatus was a king of the Huns. Denis Sinor, however, argues that given his obviously Roman name Donatus was likely a Roman refugee living among the Huns. Where Olympiodorus met Charaton is also unclear: due to Olympiodorus's traveling by sea, they may have met somewhere on the Pontic steppe. Maenchen-Helfen and Sinor, however, believe it more likely that Charaton was located in Pannonia. Also in 412, the Huns launched a new raid into Thrace.

Period of unified Hunnic rule

Ruga and Octar

The Huns again raided in 422, apparently under the command of a leader named Ruga. They reached as far as the walls of Constantinople. They appear to have forced the Eastern Empire to pay an annual tribute. In 424, they are noted as fighting for the Romans in North Africa, indicating friendly relations with the Western Roman Empire. In 425, ''magister militum'' Aetius marched into Italy with a large army of Huns to fight against forces of the Eastern Empire. The campaign ended with reconciliation, and the Huns received gold and returned to their lands. In 427, however, the Romans broke their alliance with the Huns and attacked Pannonia, perhaps reconquerring part of it. It is unclear when Ruga and his brother Octar became the supreme rulers of the Huns: Ruga appears to have ruled the land East of theCarpathians

The Carpathian Mountains or Carpathians () are a range of mountains forming an arc across Central Europe. Roughly long, it is the third-longest European mountain range after the Urals at and the Scandinavian Mountains at . The range stretche ...

while Octar ruled the territory to the north and west of the Carpathians. Kim argues that Octar was a "deputy" king in his territory while Ruga was the supreme king. Octar died around 430 while fighting the Burgundians

The Burgundians ( la, Burgundes, Burgundiōnes, Burgundī; on, Burgundar; ang, Burgendas; grc-gre, Βούργουνδοι) were an early Germanic tribe or group of tribes. They appeared in the middle Rhine region, near the Roman Empire, and ...

, who at the time lived on the right bank of the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, source ...

. Denis Sinor argues that his nephew Attila

Attila (, ; ), frequently called Attila the Hun, was the ruler of the Huns from 434 until his death in March 453. He was also the leader of a tribal empire consisting of Huns, Ostrogoths, Alans, and Bulgars, among others, in Central and E ...

likely succeeded him as ruler of the eastern portion of the Huns' empire in this year. Maenchen-Helfen, however, argues that Ruga simply became sole ruler.

In 432, Ruga aided Aetius, who had fallen into disfavor, in reobtaining his old office of ''magister militum'': Ruga either sent or threatened to send an army into Italy. In 433, Aetius surrendered Pannonia Prima to Ruga, perhaps as a reward for aid that Ruga's Huns had given him in securing his position. Either the previous year, in 432, or 434, Ruga sent an emissary to Constantinople announcing that he intended to attack some tribes whom he considered under his authority but who had fled into Roman territory; however, he died after the beginning of this campaign and the Huns left Roman territory.

Under Attila and Bleda

After Ruga's death, his nephews

After Ruga's death, his nephews Attila

Attila (, ; ), frequently called Attila the Hun, was the ruler of the Huns from 434 until his death in March 453. He was also the leader of a tribal empire consisting of Huns, Ostrogoths, Alans, and Bulgars, among others, in Central and E ...

and Bleda

Bleda () was a Hunnic ruler, the brother of Attila the Hun.

As nephews to Rugila, Attila and his elder brother Bleda succeeded him to the throne. Bleda's reign lasted for eleven years until his death. While it has been speculated by Jordanes t ...

became the rulers of the Huns: Bleda appears to have ruled in the eastern portion of the empire, while Attila ruled the west. Kim believes that Bleda was the supreme king of the two. In 435, Bleda and Attila forced the Eastern Roman Empire to sign the Treaty of Margus

The Treaty of Margus was a treaty between the Huns and the Roman Empire, signed in Margus, Moesia Superior (modern-day Požarevac, Serbia). It was signed by Roman consul Flavius Plintha in 435. Among other stipulations, the treaty doubled the ann ...

, giving the Huns trade rights and increasing the annual tribute from the Romans. The Romans also agreed to hand over Hunnic refugees and fugitive tribes.

Ruga appears to have made a commitment to aid Aetius in Gaul before his death, and Attila and Bleda kept this commitment. In 437, Huns, under the direction of Aetius and possibly with the involvement of Attila, destroyed the Burgundian kingdom

The Kingdom of the Burgundians or First Kingdom of Burgundy was established by Germanic Burgundians in the Rhineland and then in eastern Gaul in the 5th century.

History

Background

The Burgundians, a Germanic tribe, may have migrated from the ...

on the Rhine under king Gundahar, an event memorialized in medieval Germanic legend. It is possible that the Huns' destruction of the Burgundians was motivated by revenge for the death of Octar in 430. Also in 437, the Huns helped Aetius capture Tibatto, the leader of the Bagaudae

Bagaudae (also spelled bacaudae) were groups of peasant insurgents in the later Roman Empire who arose during the Crisis of the Third Century, and persisted until the very end of the Western Empire, particularly in the less-Romanised areas of G ...

, a group of rebellious peasants and slaves. In 438, an army of Huns aided the Roman general Litorius in an unsuccessful siege of the Visigothic capital of Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the prefecture of the French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger region of Occitania. The city is on the banks of the River Garonne, from the Mediterranean Sea, from the Atlantic Ocean and fr ...

. Priscus also mentions that the Huns extended their rule in "Scythia" and fought against an otherwise unknown people called the Sorosgi.

In 440, the Huns attacked the Romans during one of the annual trading fairs stipulated by the Treaty of Margus: the Huns justified this action by alleging that the bishop of Margus had crossed into Hunnic territory and plundered the Hunnic royal tombs and that the Romans themselves had breached the treaty by sheltering refugees from the Hunnic empire. When the Romans failed to turn over either the bishop of Margus or the refugees by 441, the Huns sacked a number of towns and captured the city of Viminacium

Viminacium () or ''Viminatium'', was a major city (provincial capital) and military camp of the Roman province of Moesia (today's Serbia), and the capital of ''Moesia Superior'' (hence once a metropolitan archbishopric, now a Latin titular see). ...

, razing it to the ground. The bishop of Margus, terrified that he would be handed over to the Huns, made a deal to betray the city to the Huns, which was likewise razed. The Huns also captured the fortress of Constantia on the Danube, as well as capturing and razing the cities of Singidunum

Singidunum ( sr, Сингидунум/''Singidunum'') was an ancient city which later evolved into modern Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. The name is of Celtic origin, going back to the time when Celtic tribe Scordisci settled the area in the 3r ...

and Sirmium

Sirmium was a city in the Roman province of Pannonia, located on the Sava river, on the site of modern Sremska Mitrovica in the Vojvodina autonomous provice of Serbia. First mentioned in the 4th century BC and originally inhabited by Illyria ...

. After this the Huns agreed to a truce. Maenchen-Helfen supposes that their army may have been hit by a disease, or that a rival tribe may have attacked Hunnic territory, necessitating a withdrawal. Thompson dates a further large campaign against the Eastern Roman Empire to 443; however Maenchen-Helfen, Kim, and Heather date it to around 447, after Attila had become sole ruler of the Huns.

In 444, tensions rose between the Huns and the Western Empire, and the Romans made preparations for war; however, the tensions appear to have resolved the following year through the diplomacy of Cassiodorus

Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator (c. 485 – c. 585), commonly known as Cassiodorus (), was a Roman statesman, renowned scholar of antiquity, and writer serving in the administration of Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths. ''Senator'' ...

. The terms seem to have involved the Romans handing over some territory to the Huns on the Sava River

The Sava (; , ; sr-cyr, Сава, hu, Száva) is a river in Central and Southeast Europe, a right-bank and the longest tributary of the Danube. It flows through Slovenia, Croatia and along its border with Bosnia and Herzegovina, and finally t ...

and may also have been when Attila was made ''magister militum'' to draw a salary.

Unified rule under Attila

Bleda died some time between 442 and 447, with the most likely years being 444 or 445. He appears to have been murdered by Attila. Following Bleda's death, a tribe known as the

Bleda died some time between 442 and 447, with the most likely years being 444 or 445. He appears to have been murdered by Attila. Following Bleda's death, a tribe known as the Akatziri

The Akatziri or Akatzirs ( gr, Άκατίροι, Άκατζίροι, ''Akatiroi'', ''Akatziroi''; la, Acatziri) were a tribe that lived north of the Black Sea, though the Crimean city of Cherson seemed to be under their control in the sixth centu ...

either rebelled against Attila or had never been under Attila's rule. Kim suggests that they rebelled specifically because of Bleda's death, as they were more likely to have been under Bleda's control than Attila's. The rebellion was actively encouraged by the Romans, who sent gifts to the Akatziri; however, the Romans offended the supreme chief, Buridach, by giving him gifts second rather than first. He subsequently appealed to Attila for help against the other rebellious leaders. Attila's forces then defeated the tribe after several battles: Buridach was allowed to rule his own tribe, but Attila placed his own son Ellac

Ellac (died in 454 AD) was the oldest son of Attila (434–453) and Kreka. After Attila's death in 453 AD, his Empire crumbled and its remains were ruled by his three sons, Ellac, Dengizich and Ernak. He ruled shortly, and died at the Battle of Ne ...

in command of the remaining Akatziri.

Maenchen-Helfen argues that the Huns likely fought a war against the Longobards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 and ...

, living in modern Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The ...

, in 446, in which the Longobards successfully resisted Hunnic domination.

Some time after Bleda's death, while the Huns were busy with internal affairs, Theodosius had ceased paying the stipulated tribute to the Huns. In 447, Attila sent an embassy to complain, threatening war and noting that his people were dissatisfied and that some had even begun raiding Roman territory. The Romans, however, refused to resume the tribute payments or hand over any refugees, and Attila began a full-scale attack by capturing the forts along the Danube. His forces included not only Huns, but also his subject peoples the Gepids

The Gepids, ( la, Gepidae, Gipedae, grc, Γήπαιδες) were an East Germanic tribe who lived in the area of modern Romania, Hungary and Serbia, roughly between the Tisza, Sava and Carpathian Mountains. They were said to share the relig ...

, led by their king Ardaric

Ardaric ( la, Ardaricus; c. 450 AD) was the king of the Gepids, a Germanic tribe closely related to the Goths. He was "famed for his loyalty and wisdom," one of the most trusted adherents of Attila the Hun, who "prized him above all the other chi ...

, and the Goths under their king Valamer

Valamir or Valamer (c. 420 – 469) was an Ostrogothic king in the former Roman province of Pannonia from AD 447 until his death. During his reign, he fought alongside the Huns against the Roman Empire and then, after Attila the Hun's death, fo ...

, as well as others. After they had cleared the Danube of Roman defences, the Huns then marched westward and defeated a large Roman army under the command of Arnegisclus

Arnegisclus was a ''magister militum'' of the Eastern Roman Empire in 447 AD. Possibly of Gothic descent, Arnegisclus is mentioned in 441 as an officer in Thrace, where he murdered the magister militum Johannes (father of Iordanes), with whom he ...

at the Battle of the Utus

The Battle of the Utus was fought in 447 between the army of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, and the Huns led by Attila at Utus, a river that is today the Vit in Bulgaria. It was the last of the bloody pitched battles between the Eastern ...

. The Huns then sacked and razed Marcianople. The Huns then set out for Constantinople itself, whose walls had been partially destroyed by an earthquake earlier in the year. While the Constantinoplitans were able to rebuild the walls before Attila's army approached, the Romans suffered another major defeat on the Gallipoli peninsula. The Huns proceeded to raid as far south as Thermopylae

Thermopylae (; Ancient Greek and Katharevousa: (''Thermopylai'') , Demotic Greek (Greek): , (''Thermopyles'') ; "hot gates") is a place in Greece where a narrow coastal passage existed in antiquity. It derives its name from its hot sulphur ...

and captured most of the major towns in the Balkans except for Hadrianople and Heracleia. Theodosius was forced to sue for peace: in addition to the tribute the Romans had failed to pay before, the amount of yearly tribute was raised, and the Romans were forced to evacuate a large swath of territory south of the Danube to the Huns, thus leaving the border defenseless.

In 450, Attila negotiated a new treaty with the Romans and agreed to withdraw from Roman lands; Heather believes that this was in order for him to plan an invasion of the Western Roman Empire. According to Priscus, Attila contemplated an invasion of Persia at this time as well. The treaty with Constantinople was abrogated shortly afterward by the new emperor Marcian

Marcian (; la, Marcianus, link=no; grc-gre, Μαρκιανός, link=no ; 392 – 27 January 457) was Roman emperor of the East from 450 to 457. Very little of his life before becoming emperor is known, other than that he was a (personal a ...

, however, Attila was already occupied with his plans for the Western Empire and did not respond.

Invasion of Gaul

Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

. Relations with the Western Roman Empire appear to have deteriorated already by 449. One of the leaders of the Bagaudae, Eudoxius, had also fled to the Huns in 448. Aetius and Attila had also backed different candidates to be king of the Ripuarian Franks

Ripuarian or Rhineland Franks (Latin: ''Ripuarii'' or ''Ribuarii'') were one of the two main groupings of early Frankish people, and specifically it was the name eventually applied to the tribes who settled in the old Roman territory of the Ubii, ...

in 450. Attila claimed to the East Roman ambassadors in 450 that he intended to attack the Visigoths at Toulouse as an ally of the Western Emperor Valentinian III

Valentinian III ( la, Placidus Valentinianus; 2 July 41916 March 455) was Roman emperor in the West from 425 to 455. Made emperor in childhood, his reign over the Roman Empire was one of the longest, but was dominated by powerful generals vying ...

. According to one source, Honoria, the sister of Valentinian III, sent Attila a ring and asked for his aid in escaping imprisonment at the hands of her brother. Attila then demanded half of Western Roman territory as his dowry and invaded. Kim dismisses this story as of doubtful authenticity and a "ridiculous stor . Heather is similarly skeptical that Attila would invade for this reason, noting that Attila invaded Gaul while Honoria was in Italy. Jordanes claims that Geiseric

Gaiseric ( – 25 January 477), also known as Geiseric or Genseric ( la, Gaisericus, Geisericus; reconstructed Vandalic: ) was King of the Vandals and Alans (428–477), ruling a kingdom he established, and was one of the key players in the dif ...

, king of the Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

in North Africa, encouraged Attila to attack. Thompson suggests that Attila intended to remove Aetius and actually take up his honorary office as ''magister militum''. Kim believes that it is unlikely that Attila actually intended to conquer Gaul, but rather to secure his control over Germanic tribes living on the Rhine.

The Hunnic army set out from the Hungarian Plain and likely crossed the Rhine near Koblenz

Koblenz (; Moselle Franconian: ''Kowelenz''), spelled Coblenz before 1926, is a German city on the banks of the Rhine and the Moselle, a multi-nation tributary.

Koblenz was established as a Roman military post by Drusus around 8 B.C. Its nam ...

. The Hunnic army included, besides Huns, the Gepids, Rugii, Sciri

The Sciri, or Scirians, were a Germanic people. They are believed to have spoken an East Germanic language. Their name probably means "the pure ones".

The Sciri were mentioned already in the late 3rd century BC as participants in a raid on th ...

, Thuringi

The Thuringii, Toringi or Teuriochaimai, were an early Germanic people that appeared during the late Migration Period in the Harz Mountains of central Germania, a region still known today as Thuringia. It became a kingdom, which came into confl ...

, Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths ( la, Ostrogothi, Austrogothi) were a Roman-era Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the large Gothic populations who ...

. Thompson suggests that Attila's first objection was the Ripuarian Franks, whom he summarily conquered and drafted into his army. They then captured Metz

Metz ( , , lat, Divodurum Mediomatricorum, then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle and the Seille rivers. Metz is the prefecture of the Moselle department and the seat of the parliament of the Grand ...

and Trier

Trier ( , ; lb, Tréier ), formerly known in English as Trèves ( ;) and Triers (see also names in other languages), is a city on the banks of the Moselle in Germany. It lies in a valley between low vine-covered hills of red sandstone in the ...

, before heading to besiege Orléans

Orléans (;"Orleans"

(US) and Paris Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

. The approach of Aetius' army, consisting of Romans and allies such as the Visigoths under their king (US) and Paris Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

Theodoric I

Theodoric I ( got, Þiudarīks; la, Theodericus; 390 or 393 – 20 or 24 June 451) was the King of the Visigoths from 418 to 451. Theodoric is famous for his part in stopping Attila (the Hun) at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains in 451, where ...

, Burgundians, the Alans, and some Franks, forced the Huns to break the siege of Orléans. Somewhere near Troyes

Troyes () is a commune and the capital of the department of Aube in the Grand Est region of north-central France. It is located on the Seine river about south-east of Paris. Troyes is situated within the Champagne wine region and is near ...

, the two armies met and fought in the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields

The Battle of the Catalaunian Plains (or Fields), also called the Battle of the Campus Mauriacus, Battle of Châlons, Battle of Troyes or the Battle of Maurica, took place on June 20, 451 AD, between a coalition – led by the Roman general ...

. In the standard scholarly view of the battle, despite the death of Theodoric, Attila's army was defeated and forced to retreat from Gaul. Kim argues that the battle was actually a Hunnic victory: the Huns had already been leaving Gaul after a successful campaign and simply continued to do so after the battle.

Invasion of Italy

Upon his return to Pannonia, Attila ordered the launching of raids into Illyricum to encourage the Eastern Roman Empire to resume its tribute. Rather than attacking the Eastern Empire, however, in 452 he invaded Italy. The precise reasons for this are unclear: the ''Chronicle of 452'' claims that it was due to his anger at his defeat in Gaul the previous year. The Huns crossed the

Upon his return to Pannonia, Attila ordered the launching of raids into Illyricum to encourage the Eastern Roman Empire to resume its tribute. Rather than attacking the Eastern Empire, however, in 452 he invaded Italy. The precise reasons for this are unclear: the ''Chronicle of 452'' claims that it was due to his anger at his defeat in Gaul the previous year. The Huns crossed the Julian Alps

The Julian Alps ( sl, Julijske Alpe, it, Alpi Giulie, , ) are a mountain range of the Southern Limestone Alps that stretch from northeastern Italy to Slovenia, where they rise to 2,864 m at Mount Triglav, the highest peak in Slovenia. A large p ...

and then besieged the heavily defended city of Aquileia

Aquileia / / / / ;Bilingual name of ''Aquileja – Oglej'' in: vec, Aquiłeja / ; Slovenian: ''Oglej''), group=pron is an ancient Roman city in Italy, at the head of the Adriatic at the edge of the lagoons, about from the sea, on the river ...

, eventually capturing and razing it after a long siege. They then entered the Po Valley

The Po Valley, Po Plain, Plain of the Po, or Padan Plain ( it, Pianura Padana , or ''Val Padana'') is a major geographical feature of Northern Italy. It extends approximately in an east-west direction, with an area of including its Venetic ex ...

, sacking Padua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

, Mantua

Mantua ( ; it, Mantova ; Lombard and la, Mantua) is a city and '' comune'' in Lombardy, Italy, and capital of the province of the same name.

In 2016, Mantua was designated as the Italian Capital of Culture. In 2017, it was named as the Eur ...

, Vicentia, Verona

Verona ( , ; vec, Verona or ) is a city on the Adige River in Veneto, Italy, with 258,031 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region. It is the largest city municipality in the region and the second largest in nor ...

, Brescia

Brescia (, locally ; lmo, link=no, label= Lombard, Brèsa ; lat, Brixia; vec, Bressa) is a city and '' comune'' in the region of Lombardy, Northern Italy. It is situated at the foot of the Alps, a few kilometers from the lakes Garda and Iseo ...

, and Bergamo

Bergamo (; lmo, Bèrghem ; from the proto- Germanic elements *''berg +*heim'', the "mountain home") is a city in the alpine Lombardy region of northern Italy, approximately northeast of Milan, and about from Switzerland, the alpine lakes Com ...

, before besieging and capturing Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city ...

. The Huns made no attempt to capture Ravenna

Ravenna ( , , also ; rgn, Ravèna) is the capital city of the Province of Ravenna, in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy. It was the capital city of the Western Roman Empire from 408 until its collapse in 476. It then served as the c ...

, and were either stopped or did not try to take Rome. Aetius was unable to offer a meaningful resistance and his authority was greatly damaged. The Huns received a peace embassy led by Pope Leo I

Pope Leo I ( 400 – 10 November 461), also known as Leo the Great, was bishop of Rome from 29 September 440 until his death. Pope Benedict XVI said that Leo's papacy "was undoubtedly one of the most important in the Church's history."

Leo was ...

and in the end turned back. However, Heather argues that it was a combination of disease and an attack by Eastern Roman troops on the Hunnic homeland in Pannonia that led to the Huns' withdrawal. Kim argues that the attacks by the Eastern Romans are a fiction, as the Eastern Empire was in a worse state than the West. Kim believes that the campaign had been a success and that the Huns simply withdrew after acquiring enough booty to satisfy them.

After Attila

Disintegration of Hunnic rule in the West

In 453, Attila was reportedly planning a major campaign against the Eastern Romans to force them to resume paying tribute. However, he died unexpectedly, reportedly of a hemorrhage during his wedding to a new bride. He may also have been planning an invasion of the

In 453, Attila was reportedly planning a major campaign against the Eastern Romans to force them to resume paying tribute. However, he died unexpectedly, reportedly of a hemorrhage during his wedding to a new bride. He may also have been planning an invasion of the Sasanian Empire

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

; Martin Schottky claims that "Attila’s death in 453 C.E. saved the Sasanians from an armed encounter with the Huns while they were at the height of their military power". Peter Heather, however, finds it unlikely that the Huns would have actually attacked Persia.

According to Jordanes, Attila's death precipitated a power struggle between his sons – it is unknown how many there were in total, but ancient sources mention three by name: Ellac

Ellac (died in 454 AD) was the oldest son of Attila (434–453) and Kreka. After Attila's death in 453 AD, his Empire crumbled and its remains were ruled by his three sons, Ellac, Dengizich and Ernak. He ruled shortly, and died at the Battle of Ne ...

, Dengizich

Dengizich (died in 469), was a Hunnic ruler and son of Attila. After Attila's death in 453 AD, his Empire crumbled and its remains were ruled by his three sons, Ellac, Dengizich and Ernak. He succeeded his older brother Ellac in 454 AD, and prob ...

and Ernak Ernak was the last known ruler of the Huns, and the third son of Attila. After Attila's death in 453 AD, his Empire crumbled and its remains were ruled by his three sons, Ellac, Dengizich and Ernak. He succeeded his older brother Ellac in 454 AD ...

. The brothers began fighting one another, and this caused the Gepids

The Gepids, ( la, Gepidae, Gipedae, grc, Γήπαιδες) were an East Germanic tribe who lived in the area of modern Romania, Hungary and Serbia, roughly between the Tisza, Sava and Carpathian Mountains. They were said to share the relig ...

under Ardaric

Ardaric ( la, Ardaricus; c. 450 AD) was the king of the Gepids, a Germanic tribe closely related to the Goths. He was "famed for his loyalty and wisdom," one of the most trusted adherents of Attila the Hun, who "prized him above all the other chi ...

to rebel. The Huns under Ellac then fought the Gepids and were defeated, resulting in Ellac's death. According to Jordanes, this occurred at the Battle of Nedao

The Battle of Nedao was a battle fought in Pannonia in 454 between the Huns and their former Germanic vassals. Nedao is believed to be a tributary of the Sava River.

Battle

After the death of Attila the Hun, allied forces of the subject peoples u ...

in 454, however, Heather speculates that there may have been more than just a single battle. Some tribes, such as the Sciri

The Sciri, or Scirians, were a Germanic people. They are believed to have spoken an East Germanic language. Their name probably means "the pure ones".

The Sciri were mentioned already in the late 3rd century BC as participants in a raid on th ...

, fought on the Huns' side against the Gepids. He also notes that, while 454 may have been a significant turning point, it by no means ended Hunnic rule over most of their subject peoples. According to Heather, rather than an immediate collapse, the end of Hunnic rule was a slow process whereby the Huns gradually lost control over their subject peoples.

The Huns continued to exist under Attila's sons Dengizich and Ernak. Kim argues that Dengizich had successfully reestablished Hunnic rule over the western part of their empire in 464. In 466, Dengizich demanded that Constantinople resume paying tribute to the Huns and reestablish the Huns' trading rights with the Romans. The Romans refused, however. Dengizich then decided to invade the Roman empire, with Ernak declining to join him to focus on other wars. Kim suggests that Ernak was distracted by the invasion of the Saragurs and other Oghurs

The Onoğurs or Oğurs (Ὀνόγουροι, Οὔρωγοι, Οὔγωροι; Onογurs, Ογurs; "ten tribes", "tribes"), were Turkic nomadic equestrians who flourished in the Pontic–Caspian steppe and the Volga region between 5th and 7th cen ...

, who had defeated the Akatziri in 463. Without his brother, Dengizich was forced to rely on the recently conquered Ostrogoths and the "unreliable" Bittigur tribe. His forces also included the Hunnic tribes of the Ultzinzures, Angiscires, and Bardores. The Romans were able to encourage the Goths in his army to revolt, forcing Dengizich to retreat. He died in 469, with Kim believing he was murdered, and his head was sent to the Romans. Anagast

Anagast or Anagastes () was a '' magister militum'' in the army of the Eastern Roman Empire. He was probably a Goth, as his name (as well as that of his father, '' Arnegisc(clus)'') seems to be of Gothic origin. He was sent to negotiate with De ...

es, the son of Arnegisclus

Arnegisclus was a ''magister militum'' of the Eastern Roman Empire in 447 AD. Possibly of Gothic descent, Arnegisclus is mentioned in 441 as an officer in Thrace, where he murdered the magister militum Johannes (father of Iordanes), with whom he ...

who was slain by Attila, brought Dengzich's head to Constantinople and paraded it through the streets before mounting it on a stake in the Hippodrome

The hippodrome ( el, ἱππόδρομος) was an ancient Greek stadium for horse racing and chariot racing. The name is derived from the Greek words ''hippos'' (ἵππος; "horse") and ''dromos'' (δρόμος; "course"). The term is used i ...

. This was the end of Hunnic rule in the West.

Germanic tribes as successors to the Huns in the West

Kim argues that the war after the death of Attila was actually a rebellion of the western half of the Hunnic empire, led by Ardaric, against the eastern half, led by Ellac as leader of the Akatziri Huns. He further argues that Ardaric, in common with the other leaders of the Gepids, was actually a Hun and not of Germanic origin; he notes that bones from the Gepid period frequently show Asiatic features among the ruling elite. He also notes that Gepid rule in theCarpathian Basin

The Pannonian Basin, or Carpathian Basin, is a large Sedimentary basin, basin situated in south-east Central Europe. The Geomorphology, geomorphological term Pannonian Plain is more widely used for roughly the same region though with a somewh ...

appears to have differed little from that of the Huns. Ardaric's grandson Mundo is identified in sources both as a Hun and as a Gepid. Kim explains the fact that Ardaric's kingdom was identified as a Gepid rather than a Hunnic kingdom from the fact that the western part of the Hunnic empire had been almost entirely Germanic in population.

The Sciri also emerged from Attila's empire with a potentially Hunnic King: Edeko

By the name Edeko (with various spellings:Edicon, Ediko, Edica, Ethico) are considered three contemporaneous historical figures, whom many scholars identified as one:

*A prominent Hun, who served as both Attila's deputy and his ambassador to the ...

is first encountered in sources as Attila's envoy, and is variously identified as having a Hunnic or Thuringian mother. While Heather believes that the latter is more likely, Kim argues that Edeco was in fact a Hun and that Thuringian in the source is a mistake for Torcilingi

The Turcilingi (also spelled Torcilingi or Thorcilingi) were an obscure barbarian people, or possibly a clan or dynasty, who appear in historical sources relating to Middle Danubian peoples who were present in Italy during the reign of Romulus A ...

. Accordingly, his sons Hunoulph ("Hun-wolf") and Odoacer

Odoacer ( ; – 15 March 493 AD), also spelled Odovacer or Odovacar, was a soldier and statesman of barbarian background, who deposed the child emperor Romulus Augustulus and became Rex/Dux (476–493). Odoacer's overthrow of Romulus August ...

, who would go on to conquer Italy, would also be Huns ethnically, though the armies they led were certainly mostly Germanic. Odoacer would also conquer the ''Rogii'', a tribe typically identified with the Rugii found in Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

' ''Germania'', but whom Kim holds far more likely to be a newly formed tribe that was named after the Hunnic king Ruga.

The Goths led by the Amali dynasty

The Amali – also called Amals, Amalings or Amalungs – were a leading dynasty of the Goths, a Germanic people who confronted the Roman Empire during the decline of the Western Roman Empire. They eventually became the royal house of the Ostrog ...

under their king Valamir

Valamir or Valamer (c. 420 – 469) was an Ostrogothic king in the former Roman province of Pannonia from AD 447 until his death. During his reign, he fought alongside the Huns against the Roman Empire and then, after Attila the Hun's death, ...

also became independent some time after 454. This did not include all Goths, however, some of whom are recorded as continuing to fight with the Huns as late as 468. Kim argues that even the Amali-led Goths remained loyal to the Huns until 459, when Valamir's nephew Theoderic