history of MIT on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the

The history of the

As early as 1859, the Massachusetts State Legislature was given a proposal for use of newly opened lands in

As early as 1859, the Massachusetts State Legislature was given a proposal for use of newly opened lands in

Rogers wrote

Rogers wrote  Walker established a new general course of study (Course IX) emphasizing economics, history, law, English, and modern languages. Walker also set out to reform and expand the Institute's organization by creating an Executive Committee, apart from the fifty-member Corporation, to handle regular administrative issues. He also emphasized the importance of faculty governance by regularly attending their meetings and seeking their advice on major decisions.

MIT's inability to secure a more stable financial footing during this era can largely be attributed to the existence of the

Walker established a new general course of study (Course IX) emphasizing economics, history, law, English, and modern languages. Walker also set out to reform and expand the Institute's organization by creating an Executive Committee, apart from the fifty-member Corporation, to handle regular administrative issues. He also emphasized the importance of faculty governance by regularly attending their meetings and seeking their advice on major decisions.

MIT's inability to secure a more stable financial footing during this era can largely be attributed to the existence of the  Walker also sought to improve the state of student life and alumni relations by supporting the creation of a gymnasium, dormitories, and the Technology Club which served to foster a stronger identity and loyalty among the largely commuter student body. Walker also won considerable praise from the student body by reducing the required time spent in recitation and preparation, limited the faculty to examinations lasting no longer than three hours, expanded the availability of entrance examinations in other cities, started a summer curriculum, and launched masters and doctoral graduate degree programs. These reforms were largely a response to Walker's on-going defense of the Institute and its curriculum from outside accusations of overwork, poor writing, unapplicable skills, and status as a "mere" trade school. Between 1881 and 1897, enrollments quadrupled from 302 to 1,198 students, annual degrees granted increased from 28 to 179, faculty appointments quadrupled from 38 to 156, and the endowment grew thirteen-fold from $137,000 to $1,798,000.

In the following years, the science and engineering curriculum drifted away from Rogers' ideal of combining general and professional studies and became focused on more vocational or practical and less theoretical concerns. To the extent that MIT had overspecialized to the detriment of other programs, " the school up the river" courted MIT's administration with hopes of merging the schools. An initial proposal in 1900 was cancelled after protests from MIT's alumni. In 1914, a merger of MIT and Harvard's Applied Science departments was formally announced

and was to begin "when the Institute will occupy its splendid new buildings in Cambridge". However, in 1917, the arrangement with Harvard was cancelled due to a decision by the State Judicial Court. Since the founding years, there had been at least six failed attempts to absorb MIT into Harvard.

MIT was the first university in the nation to have a curriculum in: architecture (1865), electrical engineering (1882), sanitary engineering (1889), naval architecture and marine engineering (1895), aeronautical engineering (1914), meteorology (1928), nuclear physics (1935), and artificial intelligence (1960s).

Walker also sought to improve the state of student life and alumni relations by supporting the creation of a gymnasium, dormitories, and the Technology Club which served to foster a stronger identity and loyalty among the largely commuter student body. Walker also won considerable praise from the student body by reducing the required time spent in recitation and preparation, limited the faculty to examinations lasting no longer than three hours, expanded the availability of entrance examinations in other cities, started a summer curriculum, and launched masters and doctoral graduate degree programs. These reforms were largely a response to Walker's on-going defense of the Institute and its curriculum from outside accusations of overwork, poor writing, unapplicable skills, and status as a "mere" trade school. Between 1881 and 1897, enrollments quadrupled from 302 to 1,198 students, annual degrees granted increased from 28 to 179, faculty appointments quadrupled from 38 to 156, and the endowment grew thirteen-fold from $137,000 to $1,798,000.

In the following years, the science and engineering curriculum drifted away from Rogers' ideal of combining general and professional studies and became focused on more vocational or practical and less theoretical concerns. To the extent that MIT had overspecialized to the detriment of other programs, " the school up the river" courted MIT's administration with hopes of merging the schools. An initial proposal in 1900 was cancelled after protests from MIT's alumni. In 1914, a merger of MIT and Harvard's Applied Science departments was formally announced

and was to begin "when the Institute will occupy its splendid new buildings in Cambridge". However, in 1917, the arrangement with Harvard was cancelled due to a decision by the State Judicial Court. Since the founding years, there had been at least six failed attempts to absorb MIT into Harvard.

MIT was the first university in the nation to have a curriculum in: architecture (1865), electrical engineering (1882), sanitary engineering (1889), naval architecture and marine engineering (1895), aeronautical engineering (1914), meteorology (1928), nuclear physics (1935), and artificial intelligence (1960s).

A pilot training program was necessary as the

A pilot training program was necessary as the

, page 13 The

MIT has been always been notionally

MIT has been always been notionally

The Institute announced they would be moving all classes online and student were told to move out of dormitories on March 10, 2020.

On July 7, 2020 the school announced that seniors would be allowed to return to campus in September with some in-person classes beginning on September 7 and other students would be granted access to school facilities and special consideration for housing on a case-by-case basis.

The Institute announced they would be moving all classes online and student were told to move out of dormitories on March 10, 2020.

On July 7, 2020 the school announced that seniors would be allowed to return to campus in September with some in-person classes beginning on September 7 and other students would be granted access to school facilities and special consideration for housing on a case-by-case basis.

"Names on Institute Buildings Lend Inspiration to Future Scientists"

'' The Tech'', Friday, December 22, 1922 * Mindell, David, and Merritt Roe Smith

"STS.050 The History of MIT, Spring 2011."

MIT OpenCourseWare. Accessed 04 Mar 2013. *MIT Librarie

"MIT Facts/MIT History."

MIT Museum

* ttp://museum.mit.edu/150/ MIT 150th Anniversary Exhibition site, collecting nominations of & comments about objects that are emblematic of MIT*

Evolution of the first-year academic experience

(with graphical timeline of Institute Requirements, Pass/Fail, and Orientation - September 21, 2018 {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of The Massachusetts Institute Of Technology History of science and technology in the United States

The history of the

The history of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of th ...

can be traced back to the 1861 incorporation of the "Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Boston Society of Natural History

The Boston Society of Natural History (1830–1948) in Boston, Massachusetts, was an organization dedicated to the study and promotion of natural history. It published a scholarly journal and established a museum. In its first few decades, the s ...

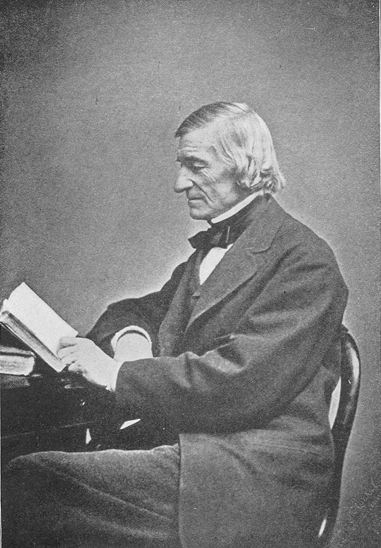

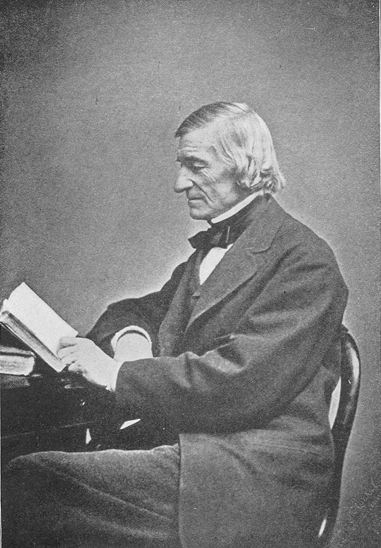

" led primarily by William Barton Rogers

William Barton Rogers (December 7, 1804 – May 30, 1882) was an American geologist, physicist, and educator at the College of William & Mary from 1828 to 1835 and at the University of Virginia from 1835 to 1853. In 1861, Rogers founded the M ...

.

Vision and mission

As early as 1859, the Massachusetts State Legislature was given a proposal for use of newly opened lands in

As early as 1859, the Massachusetts State Legislature was given a proposal for use of newly opened lands in Back Bay

Back Bay is an officially recognized neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, built on reclaimed land in the Charles River basin. Construction began in 1859, as the demand for luxury housing exceeded the availability in the city at the time, and t ...

in Boston for a museum and Conservatory of Art and Science.

On April 10, 1861, the governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts signed a charter for the incorporation of the "Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Boston Society of Natural History" which had been submitted by William Barton Rogers

William Barton Rogers (December 7, 1804 – May 30, 1882) was an American geologist, physicist, and educator at the College of William & Mary from 1828 to 1835 and at the University of Virginia from 1835 to 1853. In 1861, Rogers founded the M ...

, a natural scientist. Rogers sought to establish a new form of higher education to address the challenges posed by rapid advances in science and technology in the mid-19th century, that he believed classic institutions were ill-prepared to deal with.

With the charter approved, Rogers began raising funds, developing a curriculum and looking for a suitable location. The Rogers Plan, as it came to be known, was rooted in three principles: the educational value of useful knowledge, the necessity of "learning by doing", and integrating a professional and liberal arts education at the undergraduate level.

MIT was a pioneer in the use of laboratory instruction. Its founding philosophy is "the teaching, not of the manipulations and minute details of the arts, which can be done only in the workshop, but the inculcation of all the scientific principles which form the basis and explanation of them".

Because open conflict in the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

broke out only two days later on April 12, 1861, Rogers faced enormous difficulties raising funds to match conditional financial commitments from the state. Thus, his recruitment of faculty and students was delayed, but eventually MIT's first classes were held in rented space at the Mercantile Building in downtown Boston in 1865.

Boston Tech (1865–1916)

:''Includes the administrations ofWilliam Barton Rogers

William Barton Rogers (December 7, 1804 – May 30, 1882) was an American geologist, physicist, and educator at the College of William & Mary from 1828 to 1835 and at the University of Virginia from 1835 to 1853. In 1861, Rogers founded the M ...

(1862–1870, 1879–1881), John Daniel Runkle (1870–1879), Francis Amasa Walker

Francis Amasa Walker (July 2, 1840 – January 5, 1897) was an American economist, statistician, journalist, educator, academic administrator, and an officer in the Union Army.

Walker was born into a prominent Boston family, the son of the econo ...

(1881–1896), and Henry Pritchett

Henry Smith Pritchett (April 16, 1857 – August 28, 1939) was an American astronomer and educator.

Biography

Pritchett was born on April 16, 1857 in Fayette, Missouri, the son of Carr Waller Pritchett, Sr., and attended Pritchett Colleg ...

(1900–1907)''

Construction of the first MIT building was completed in Boston's Back Bay

Back Bay is an officially recognized neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, built on reclaimed land in the Charles River basin. Construction began in 1859, as the demand for luxury housing exceeded the availability in the city at the time, and t ...

in 1866 and would be known as "Boston Tech" until the campus moved across the Charles River

The Charles River ( Massachusett: ''Quinobequin)'' (sometimes called the River Charles or simply the Charles) is an river in eastern Massachusetts. It flows northeast from Hopkinton to Boston along a highly meandering route, that doubles bac ...

to Cambridge in 1916.

At the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition

The Centennial International Exhibition of 1876, the first official World's Fair to be held in the United States, was held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from May 10 to November 10, 1876, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the signing of the ...

of 1875, Runkle was impressed by the work of the Russian Victor Della-Vos, who had introduced a pedagogical approach combining manual and theoretical instruction at the Moscow Imperial Technical Academy. Runkle became an advocate of this approach, introducing it at MIT.

MIT's financial position was severely undermined following the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

and subsequent Long Depression

The Long Depression was a worldwide price and economic recession, beginning in 1873 and running either through March 1879, or 1896, depending on the metrics used. It was most severe in Europe and the United States, which had been experiencing st ...

. Enrollments decreased sharply after 1875 and by 1878, the university had abolished three professorships, reduced faculty salaries, and there was talk among members of the Corporation of closing the Institute. In 1879, Runkle retired from a nine-year tenure as the MIT's second president trying to weather these challenges, but the board of trustees (the "MIT Corporation") was unable to secure a new successor and elected the seventy-five-year-old founder William Barton Rogers

William Barton Rogers (December 7, 1804 – May 30, 1882) was an American geologist, physicist, and educator at the College of William & Mary from 1828 to 1835 and at the University of Virginia from 1835 to 1853. In 1861, Rogers founded the M ...

back to the post in the interim under his stipulated conditions that he be allowed to resign upon the discovery of a successor and $100,000 ($ in 2009) be raised to fund the Institute's obligations.

Rogers wrote

Rogers wrote Francis Amasa Walker

Francis Amasa Walker (July 2, 1840 – January 5, 1897) was an American economist, statistician, journalist, educator, academic administrator, and an officer in the Union Army.

Walker was born into a prominent Boston family, the son of the econo ...

in June 1880 to offer him the Presidency. Because no alumni of MIT were of sufficient age to fill the position, most scientific leaders lacked executive experience, and few leaders shared the founder's, faculty's, or Corporation's vision for the young technical institute, Walker's previous experience and reputation made him uniquely qualified for the position. Walker ultimately accepted in early May and was formally elected President by the MIT Corporation on May 25, 1881; however, the assassination attempt on President Garfield in July 1881 and the ensuing illness before Garfield's death in September upset Walker's transition and delayed his formal introduction to the faculty of MIT until November 5, 1881. On May 30, 1882, during Walker's first Commencement exercises, Rogers died mid-speech where his last words were famously "bituminous coal

Bituminous coal, or black coal, is a type of coal containing a tar-like substance called bitumen or asphalt. Its coloration can be black or sometimes dark brown; often there are well-defined bands of bright and dull material within the seams. It ...

".

Walker established a new general course of study (Course IX) emphasizing economics, history, law, English, and modern languages. Walker also set out to reform and expand the Institute's organization by creating an Executive Committee, apart from the fifty-member Corporation, to handle regular administrative issues. He also emphasized the importance of faculty governance by regularly attending their meetings and seeking their advice on major decisions.

MIT's inability to secure a more stable financial footing during this era can largely be attributed to the existence of the

Walker established a new general course of study (Course IX) emphasizing economics, history, law, English, and modern languages. Walker also set out to reform and expand the Institute's organization by creating an Executive Committee, apart from the fifty-member Corporation, to handle regular administrative issues. He also emphasized the importance of faculty governance by regularly attending their meetings and seeking their advice on major decisions.

MIT's inability to secure a more stable financial footing during this era can largely be attributed to the existence of the Lawrence Scientific School

The Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) is the engineering school within Harvard University's Faculty of Arts and Sciences, offering degrees in engineering and applied sciences to graduate students admitted ...

at nearby Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

. Given the choice between funding technological research at the oldest university in the nation or an independent and adolescent institution, potential benefactors were indifferent or even hostile to funding MIT's competing mission. Earlier overtures from founding MIT faculty member and now Harvard President Charles William Eliot

Charles William Eliot (March 20, 1834 – August 22, 1926) was an American academic who was president of Harvard University from 1869 to 1909the longest term of any Harvard president. A member of the prominent Eliot family of Boston, he transfor ...

towards consolidation of the two schools had been rejected or disrupted by Rogers in 1870 and 1878. Also, despite his previous tenure at the analogous Sheffield School, Walker now remained committed to MIT's independence from the larger institution.

In light of the difficulties in raising capital for these expansions and despite MIT's privately endowed status, Walker and other members of the Corporation lobbied the Massachusetts legislature for a $200,000 grant to aid in the industrial development of the Commonwealth. After intensive negotiations that called upon his extensive connections and civic experience, in 1887 the legislature made a grant of $300,000 over two years to the Institute, and would lead to a total of $1.6 million in grants from the Commonwealth to the Institute before the practice was abolished in 1921.

Walker sought to erect a new building on to address the increasingly cramped conditions of the original Boylston Street

Boylston Street is a major east–west thoroughfare in the city of Boston, Massachusetts. The street begins in Boston's Chinatown neighborhood, forms the southern border of the Boston Public Garden and Boston Common, runs through Back Bay, and e ...

campus located near Copley Square

Copley Square , named for painter John Singleton Copley, is a public square in Boston's Back Bay neighborhood, bounded by Boylston Street, Clarendon Street, St. James Avenue, and Dartmouth Street. Prior to 1883 it was known as Art Square due to i ...

. Because the stipulations of the original land grant prevented MIT from covering more than two-ninths of its current lot, Walker announced his intention to build the industrial expansion on a lot directly across from the Trinity Church fully intending that their opposition would lead to favorable terms for selling the proposed land and funding construction elsewhere. With the financial health of the Institute only beginning to recover, Walker began construction on the partially funded expansion fully expecting the immediacy of the project to be a persuasive tool for raising its funds. The strategy was only partially successful as the 1883 building had laboratory facilities that were second-to-none but also lacked the outward architectural grandeur of its sister building and was generally considered an eyesore on its surroundings. Mechanical shops were moved out of the Rogers Building in the mid-1880s to accommodate other programs and in 1892 the Institute began construction on another Copley Square building. New programs were also launched under Walker's tenure: Electrical Engineering in 1882, Chemical Engineering in 1888, Sanitary Engineering in 1889, Geology in 1890, Naval Architecture in 1893.

Walker also sought to improve the state of student life and alumni relations by supporting the creation of a gymnasium, dormitories, and the Technology Club which served to foster a stronger identity and loyalty among the largely commuter student body. Walker also won considerable praise from the student body by reducing the required time spent in recitation and preparation, limited the faculty to examinations lasting no longer than three hours, expanded the availability of entrance examinations in other cities, started a summer curriculum, and launched masters and doctoral graduate degree programs. These reforms were largely a response to Walker's on-going defense of the Institute and its curriculum from outside accusations of overwork, poor writing, unapplicable skills, and status as a "mere" trade school. Between 1881 and 1897, enrollments quadrupled from 302 to 1,198 students, annual degrees granted increased from 28 to 179, faculty appointments quadrupled from 38 to 156, and the endowment grew thirteen-fold from $137,000 to $1,798,000.

In the following years, the science and engineering curriculum drifted away from Rogers' ideal of combining general and professional studies and became focused on more vocational or practical and less theoretical concerns. To the extent that MIT had overspecialized to the detriment of other programs, " the school up the river" courted MIT's administration with hopes of merging the schools. An initial proposal in 1900 was cancelled after protests from MIT's alumni. In 1914, a merger of MIT and Harvard's Applied Science departments was formally announced

and was to begin "when the Institute will occupy its splendid new buildings in Cambridge". However, in 1917, the arrangement with Harvard was cancelled due to a decision by the State Judicial Court. Since the founding years, there had been at least six failed attempts to absorb MIT into Harvard.

MIT was the first university in the nation to have a curriculum in: architecture (1865), electrical engineering (1882), sanitary engineering (1889), naval architecture and marine engineering (1895), aeronautical engineering (1914), meteorology (1928), nuclear physics (1935), and artificial intelligence (1960s).

Walker also sought to improve the state of student life and alumni relations by supporting the creation of a gymnasium, dormitories, and the Technology Club which served to foster a stronger identity and loyalty among the largely commuter student body. Walker also won considerable praise from the student body by reducing the required time spent in recitation and preparation, limited the faculty to examinations lasting no longer than three hours, expanded the availability of entrance examinations in other cities, started a summer curriculum, and launched masters and doctoral graduate degree programs. These reforms were largely a response to Walker's on-going defense of the Institute and its curriculum from outside accusations of overwork, poor writing, unapplicable skills, and status as a "mere" trade school. Between 1881 and 1897, enrollments quadrupled from 302 to 1,198 students, annual degrees granted increased from 28 to 179, faculty appointments quadrupled from 38 to 156, and the endowment grew thirteen-fold from $137,000 to $1,798,000.

In the following years, the science and engineering curriculum drifted away from Rogers' ideal of combining general and professional studies and became focused on more vocational or practical and less theoretical concerns. To the extent that MIT had overspecialized to the detriment of other programs, " the school up the river" courted MIT's administration with hopes of merging the schools. An initial proposal in 1900 was cancelled after protests from MIT's alumni. In 1914, a merger of MIT and Harvard's Applied Science departments was formally announced

and was to begin "when the Institute will occupy its splendid new buildings in Cambridge". However, in 1917, the arrangement with Harvard was cancelled due to a decision by the State Judicial Court. Since the founding years, there had been at least six failed attempts to absorb MIT into Harvard.

MIT was the first university in the nation to have a curriculum in: architecture (1865), electrical engineering (1882), sanitary engineering (1889), naval architecture and marine engineering (1895), aeronautical engineering (1914), meteorology (1928), nuclear physics (1935), and artificial intelligence (1960s).

World War I and after (1917–1939)

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

prepared for the emerging technology of naval aviation

Naval aviation is the application of military air power by navies, whether from warships that embark aircraft, or land bases.

Naval aviation is typically projected to a position nearer the target by way of an aircraft carrier. Carrier-based ...

for World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. Following the United States declaration of war on 6 April 1917, the Navy implemented a three-part pilot training program beginning with two months of ground school, followed by preliminary flight training teaching student pilots to fly solo, and advanced flight training to qualification as a naval aviator with a commission in the Naval Reserve Flying Corps.

Commander Jerome Clarke Hunsaker

Jerome Clarke Hunsaker (August 26, 1886 – September 10, 1984) was an American naval officer and aeronautical engineer, born in Creston, Iowa, and educated at the U.S. Naval Academy and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His work with Gus ...

, who had previously studied and then taught at the MIT School of Aeronautical Engineering, encouraged the Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

to establish the Navy's first ground school for pilot training at MIT. The first class of fifty student pilots arrived on 23 July 1917 for an eight-week training program covering electricity, signals, photography, seamanship, navigation, gunnery, aeronautic engines, theory of flight, and aircraft instruments. MIT provided training and quarters, exclusive of beds and bedding, at a cost per student of ten dollars per week for the first four weeks, and five dollars for succeeding weeks. New classes arrived at intervals of two weeks. The last of 34 classes graduated on 18 January 1919. Of 4,911 students enrolling in the ground school, 3,622 graduated qualified for preliminary flight training.

The MIT ground school provided the model for similar ground school programs opened in July 1918 at the University of Washington

The University of Washington (UW, simply Washington, or informally U-Dub) is a public research university in Seattle, Washington.

Founded in 1861, Washington is one of the oldest universities on the West Coast; it was established in Seatt ...

in Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest region o ...

, and at Dunwoody Institute

Dunwoody College of Technology is a private technology school in Minneapolis, Minnesota. It offers Bachelor of Science (B.S.), Bachelor of Architecture (B. Arch) and Associate of Applied Science (A.A.S.) degrees.

History

Dunwoody College was ...

in Minneapolis

Minneapolis () is the largest city in Minnesota, United States, and the county seat of Hennepin County. The city is abundant in water, with thirteen lakes, wetlands, the Mississippi River, creeks and waterfalls. Minneapolis has its origin ...

. The naval aviation training program at MIT was expanded to include an aerography school training 54 weather forecasters, and an inspector's school training 114 airplane inspectors and 58 engine inspectors to oversee quality control of newly manufactured aviation material.

World War II and Cold War (1940–1966)

: ''Includes the administrations of James R. Killian (1948-1959) and Julius A. Stratton (1959-1966)'' MIT was drastically changed by its involvement in military research during World War Two. Bush, who had been MIT's Vice President (effectively Provost) was appointed head of theOffice of Scientific Research and Development

The Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) was an agency of the United States federal government created to coordinate scientific research for military purposes during World War II. Arrangements were made for its creation during May 1 ...

which was responsible for the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

. Government-sponsored research had contributed to a fantastic growth in the size of the Institute's research staff and physical plant as well as a shifting the educational focus away from undergraduates to graduate studies.Report of the Committee on Educational Survey, page 13 The

MIT Radiation Laboratory

The Radiation Laboratory, commonly called the Rad Lab, was a microwave and radar research laboratory located at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It was first created in October 1940 and operated until 31 ...

greatly accelerated the development of radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, Marine radar, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor v ...

technology invented in the United Kingdom. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, MIT was one of 131 colleges and universities nationally that took part in the V-12 Navy College Training Program

The V-12 Navy College Training Program was designed to supplement the force of commissioned officers in the United States Navy during World War II. Between July 1, 1943, and June 30, 1946, more than 125,000 participants were enrolled in 131 colleg ...

which offered students a path to a Navy commission.

Cold War and Space Race

As the Cold War and Space Race intensified and concerns about thetechnology gap Technology Gap Theory is a model developed by M.V. Posner in 1961, which describes an advantage enjoyed by the country that introduces new goods in a market. The country will enjoy a comparative advantage as well as a temporary state of monopoly un ...

between the U.S. and the Soviet Union grew more pervasive throughout the 1950s and 1960s, MIT's Department of Nuclear Engineering as well as the Center for International Studies were established in 1957. In 1951, visiting professor Gordon Welchman

William Gordon Welchman (15 June 1906 – 8 October 1985) was a British mathematician. During World War II, he worked at Britain's secret codebreaking centre, "Station X" at Bletchley Park, where he was one of the most important contributors. ...

taught the first computer programming course at MIT; among his students were Frank Heart, who would go on to become a leading Interface Message Processor

The Interface Message Processor (IMP) was the packet switching node used to interconnect participant networks to the ARPANET from the late 1960s to 1989. It was the first generation of gateways, which are known today as routers. An IMP was a ...

project manager at Bolt Beranek and Newman

Raytheon BBN (originally Bolt Beranek and Newman Inc.) is an American research and development company, based next to Fresh Pond in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States.

In 1966, the Franklin Institute awarded the firm the Frank P. Brow ...

.

Lewis Report

Walker's Course IX on General Studies was dissolved shortly after his death and a seventy-year debate followed over what was the appropriate role and scope of humanistic and social studies at MIT. A new Department of Economics, Statistics, and Political Science was established in 1903 to replace Course IX, which was later split into a Department of Economics and Statistics and a Department of History of Political Science in 1907.Karl Taylor Compton

Karl Taylor Compton (September 14, 1887 – June 22, 1954) was a prominent American physicist and president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) from 1930 to 1948.

The early years (1887–1912)

Karl Taylor Compton was born in ...

reorganized the Institute to incorporate a Division of Humanities under which these departments were placed in 1932, but could offer no degrees. Between 1918 and 1956, political science classes and faculty were subsumed or merged into any of History and English or Economics and Social Science until a separate Ph.D. program was approved in 1958. A PhD program in Economics was launched in 1941.

The 1949 report of the Committee on Educational Survey recommended the establishment of a School of Humanities granting degrees which led to the establishment of the same in 1950 and separate departments in Economics and Political Science were formally established in 1965. Since 1975, all MIT undergraduate students have been required to take eight classes distributed across the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences before receiving their degrees.

Social movements and activism (1966–1980)

:''Includes the administrations ofHoward W. Johnson

Howard Wesley Johnson (July 2, 1922 – December 12, 2009) was an American educator. He served as dean of the MIT Sloan School of Management between 1959 and 1966, president of MIT between 1966 and 1971, and chairman of the MIT Corporation ( ...

(1966–1971) and Jerome Wiesner

Jerome Bert Wiesner (May 30, 1915 – October 21, 1994) was a professor of electrical engineering, chosen by President John F. Kennedy as chairman of his Science Advisory Committee (PSAC). Educated at the University of Michigan, Wiesner was asso ...

(1971–1980)

Co-education

MIT has been always been notionally

MIT has been always been notionally coeducation

Mixed-sex education, also known as mixed-gender education, co-education, or coeducation (abbreviated to co-ed or coed), is a system of education where males and females are educated together. Whereas single-sex education was more common up to t ...

al, admitting Ellen Swallow Richards

Ellen Henrietta Swallow Richards (December 3, 1842 – March 30, 1911) was an American industrial and safety engineer, environmental chemist, and university faculty member in the United States during the 19th century. Her pioneering work i ...

as the first female student in 1870. Female students were at first a tiny minority (numbering in the dozens) because they had no accommodations and were thus generally local residents. This changed with the completion of the first women's dormitory, McCormick Hall, in 1964. Construction was funded by Katherine Dexter McCormick, who had graduated with a biology degree and who also funded development of the birth control pill

The combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP), often referred to as the birth control pill or colloquially as "the pill", is a type of birth control that is designed to be taken orally by women. The pill contains two important hormones: progesti ...

. Women constituted 45% of the undergraduates and 31% of the graduate students enrolled in 2013.

Anti-war protests

However, by the late 1960s and early 1970s, intense protests by student and faculty activists against military-related research required that the MIT administration spin these laboratories off into what would become theCharles Stark Draper Laboratory

Draper Laboratory is an American non-profit research and development organization, headquartered in Cambridge, Massachusetts; its official name is The Charles Stark Draper Laboratory, Inc (sometimes abbreviated as CSDL). The laboratory specialize ...

and Lincoln Laboratory

The MIT Lincoln Laboratory, located in Lexington, Massachusetts, is a United States Department of Defense federally funded research and development center chartered to apply advanced technology to problems of national security. Research and d ...

. The extent of these protests is reflected by the fact that MIT had more names on " President Nixon's enemies list" than any other single organization, among them its president Jerome Wiesner

Jerome Bert Wiesner (May 30, 1915 – October 21, 1994) was a professor of electrical engineering, chosen by President John F. Kennedy as chairman of his Science Advisory Committee (PSAC). Educated at the University of Michigan, Wiesner was asso ...

and professor Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American public intellectual: a linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist, historian, social critic, and political activist. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky i ...

. Memos revealed during Watergate indicated that Nixon had ordered MIT's federal subsidy cut "in view of Wiesner's anti-defense bias."

Social movements

MIT's particular strain of anti-authoritarianism has manifested itself in other forms. In 1977, two female students, juniors Susan Gilbert and Roxanne Ritchie, were disciplined for publishing an article on April 28 of that year in the "alternative" MIT campus weekly ''thursday''. Entitled "Consumer Guide to MIT Men," the article was a sex survey of 36 men the two claimed to have had sex with, and the men were listed with their full names and rated for their performance. Gilbert and Ritchie had intended to turn the tables on the rating systems and facebooks men use for women, but their article led not only to disciplinary action against them but also to a protest petition signed by 200 students, as well as condemnation by President Jerome B. Wiesner, who published a fierce criticism of the article. Another minor campus uproar occurred when the traditional pornographic registration-day movie was replaced byStar Wars

''Star Wars'' is an American epic space opera multimedia franchise created by George Lucas, which began with the eponymous 1977 film and quickly became a worldwide pop-culture phenomenon. The franchise has been expanded into various film ...

in 1984.

Course "Bibles"

In 1970, the then-Dean of Institute Relations, Benson R. Snyder, published '' The Hidden Curriculum,'' in which he argued that a mass of unstated assumptions and requirements dominated MIT students' lives and inhibited their ability to function creatively. Snyder contended that these unwritten regulations, like the implicit curricula of informally compiled "course bibles" (problem set A problem set, sometimes shortened as pset, is a teaching tool used by many universities. Most courses in physics, math, engineering, chemistry, and computer science will give problem sets on a regular basis. They can also appear in other subjects ...

s and solutions from previous years' classes), often outweighed the effect of the "formal curriculum," and that the situation was not unique to MIT. After studying the behavior of MIT and Wellesley students, Snyder observed that "bibles" were often in fact counterproductive; they fooled professors into believing that their classes were imparting broad knowledge as intended, but instead locked professors and students into a feedback cycle to the detriment of actual education.

New programs

* MIT and Wellesley begin cross-registration program in 1968 *Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program

An Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program provides funding and/or credit to undergraduate students who volunteer for faculty-mentored research projects pertaining to all academic disciplines.

Participating universities

Universities involve ...

(UROP) established by Margaret MacVicar in 1969

* Department of Mechanical Engineering offers 2.007 Introduction to Design, a robotics competition

* MIT-Harvard Program in Health Sciences and Technology established in 1970. Becomes Whitaker College of Health Sciences, Technology, and Management in 1977.

* Independent Activities Period (IAP) first offered in 1971

* Council for the Arts founded in 1972.

* Program in Science, Technology, and Society established in 1977.

Changing roles and priorities (1980–2004)

:''Includes the administrations of Paul E. Gray (1980–1990) andCharles M. Vest

Charles "Chuck" Marstiller Vest (September 9, 1941 – December 12, 2013) was an American educator and engineer. He served as President of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from October 1990 until December 2004. He succeeded Paul Gray a ...

(1990–2004)''

Ethical disputes

In 1986,David Baltimore

David Baltimore (born March 7, 1938) is an American biologist, university administrator, and 1975 Nobel laureate in Physiology or Medicine. He is President Emeritus and Distinguished Professor of Biology at the California Institute of Tec ...

, a Nobel Laureate

The Nobel Prizes ( sv, Nobelpriset, no, Nobelprisen) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make o ...

, and his colleague, Thereza Imanishi-Kari

Thereza Imanishi-Kari is an associate professor of pathology at Tufts University. Her research focuses on the origins of autoimmune diseases, particularly systemic lupus erythematosus, studied using mice as model organisms. Previously she had been ...

, were accused of research misconduct

Scientific misconduct is the violation of the standard codes of scholarly conduct and ethical behavior in the publication of professional scientific research. A '' Lancet'' review on ''Handling of Scientific Misconduct in Scandinavian countrie ...

. The ensuing controversy involved a Congressional investigation and required him to resign from his new appointment as president of Rockefeller University

The Rockefeller University is a private biomedical research and graduate-only university in New York City, New York. It focuses primarily on the biological and medical sciences and provides doctoral and postdoctoral education. It is classif ...

although the allegations against Imanishi-Kari were dropped and Baltimore eventually became an endowed professor at and president of Caltech

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech or CIT)The university itself only spells its short form as "Caltech"; the institution considers other spellings such a"Cal Tech" and "CalTech" incorrect. The institute is also occasional ...

.

Given the scale and reputation of MIT's research accomplishments, allegations of research misconduct

Scientific misconduct is the violation of the standard codes of scholarly conduct and ethical behavior in the publication of professional scientific research. A '' Lancet'' review on ''Handling of Scientific Misconduct in Scandinavian countrie ...

or improprieties have received substantial press coverage. Professor David Baltimore

David Baltimore (born March 7, 1938) is an American biologist, university administrator, and 1975 Nobel laureate in Physiology or Medicine. He is President Emeritus and Distinguished Professor of Biology at the California Institute of Tec ...

, a Nobel Laureate

The Nobel Prizes ( sv, Nobelpriset, no, Nobelprisen) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make o ...

, became embroiled in a misconduct investigation starting in 1986 that led to Congressional hearings in 1991. Professor Ted Postol

Theodore A. Postol (born 1946) is a professor emeritus of Science, Technology, and International Security at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Prior to his work at MIT, he worked at Argonne National Laboratory, the Pentagon, and Stanford ...

has accused the MIT administration since 2000 of attempting to whitewash

Whitewash, or calcimine, kalsomine, calsomine, or lime paint is a type of paint made from slaked lime (calcium hydroxide, Ca(OH)2) or chalk calcium carbonate, (CaCO3), sometimes known as "whiting". Various other additives are sometimes used.

...

potential research misconduct at the Lincoln Lab facility involving a ballistic missile defense

Missile defense is a system, weapon, or technology involved in the detection, tracking, interception, and also the destruction of attacking missiles. Conceived as a defense against nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), ...

test, though a final investigation into the matter has not been completed. Dean of Admissions Marilee Jones resigned in April 2007 after she "misrepresented her academic degrees" when she applied to an administrative assistant position in 1979 and never corrected the record despite her subsequent promotions.

Civic relations

TheCambridge City Council

Cambridge City Council is a district council in the county of Cambridgeshire, which governs the City of Cambridge.

History

Cambridge was granted a Royal Charter by King John in 1207, which permitted the appointment of a mayor. The first recorde ...

imposed a citywide moratorium on research into recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA (rDNA) molecules are DNA molecules formed by laboratory methods of genetic recombination (such as molecular cloning) that bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be f ...

in 1976 in response to community concerns that Harvard and MIT researchers may inadvertently release mutant organisms into the ecosystem but the ban was lifted in 1977 after an extensive dialogue between scientists, politicians, and community leaders. Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, American politicians and business leaders accused MIT and other universities of contributing to a declining economy by transferring taxpayer-funded research and technology to international — especially Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

— firms that were competing with struggling American businesses.

The Justice Department

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

filed an antitrust suit against MIT and the eight Ivy League

The Ivy League is an American collegiate athletic conference comprising eight private research universities in the Northeastern United States. The term ''Ivy League'' is typically used beyond the sports context to refer to the eight school ...

colleges in 1991 for holding "Overlap Meetings" to prevent bidding wars over promising students from consuming funds for need-based scholarships. While the Ivy League institutions settled

A settler is a person who has migrated to an area and established a permanent residence there, often to colonize the area.

A settler who migrates to an area previously uninhabited or sparsely inhabited may be described as a pioneer.

Settle ...

, MIT contested the charges on the grounds that the practice was not anticompetitive because it ensured the availability of aid for the greatest number of students. MIT ultimately prevailed when the Justice Department dropped the case in 1994. In 2001, the Environmental Protection Agency

A biophysical environment is a biotic and abiotic surrounding of an organism or population, and consequently includes the factors that have an influence in their survival, development, and evolution. A biophysical environment can vary in scale ...

sued MIT for violating Clean Water Act

The Clean Water Act (CWA) is the primary federal law in the United States governing water pollution. Its objective is to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the nation's waters; recognizing the responsibiliti ...

and Clean Air Act with regard to its hazardous waste

Hazardous waste is waste that has substantial or potential threats to public health or the environment. Hazardous waste is a type of dangerous goods. They usually have one or more of the following hazardous traits: ignitability, reactivity, cor ...

storage and disposal procedures. MIT settled the suit by paying a $155,000 fine and launching three environmental projects.

Suicide and mental health

A number of student deaths in the late 1990s and early 2000s resulted in considerable media attention to MIT's culture and student life. After the alcohol-related death of Scott Krueger in September 1997 as a new member at thePhi Gamma Delta

Phi Gamma Delta (), commonly known as Fiji, is a social Fraternities and sororities, fraternity with more than 144 active chapters and 10 colonies across the United States and Canada. It was founded at Washington & Jefferson College, Jefferson C ...

fraternity, MIT began requiring all freshmen to live in the dormitory system. The 2000 suicide of MIT undergraduate Elizabeth Shin drew attention to suicides at MIT and created a controversy over whether MIT had an unusually high suicide rate. In late 2001 a task force's recommended improvements in student mental health

Mental health encompasses emotional, psychological, and social well-being, influencing cognition, perception, and behavior. It likewise determines how an individual handles Stress (biology), stress, interpersonal relationships, and decision-maki ...

services were implemented, including expanding staff and operating hours at the mental health center. These and later cases were significant as well because they sought to prove the negligence and liability of university administrators in loco parentis

The term ''in loco parentis'', Latin for "in the place of a parent" refers to the legal responsibility of a person or organization to take on some of the functions and responsibilities of a parent.

Originally derived from English common law, ...

.

Faculty diversity

MIT has been nominallycoeducation

Mixed-sex education, also known as mixed-gender education, co-education, or coeducation (abbreviated to co-ed or coed), is a system of education where males and females are educated together. Whereas single-sex education was more common up to t ...

al since admitting Ellen Swallow Richards

Ellen Henrietta Swallow Richards (December 3, 1842 – March 30, 1911) was an American industrial and safety engineer, environmental chemist, and university faculty member in the United States during the 19th century. Her pioneering work i ...

in 1870. (Richards also became the first female member of MIT's faculty, specializing in sanitary chemistry.) Female students, however, remained a very small minority (numbered in dozens) prior to the completion of the first wing of a women's dormitory, McCormick Hall, in 1963. By 1993, 32% of MIT's undergraduates were female and in 2006, the number had increased to near-parity (47.5%). A 1998 MIT study concluded that a systemic bias

Systemic bias, also called institutional bias, and related to structural bias, is the inherent tendency of a process to support particular outcomes. The term generally refers to human systems such as institutions. Institutional bias and structur ...

against female faculty existed in its college of science, although the study's methods were controversial. Since the study, the number of women undergraduates increased from 34 percent to 42 percent, women graduate students has increased from 20 percent to 29 percent, and women outnumber men in 10 undergraduate majors. Additionally, women have headed departments within the school of science, engineering, and MIT has appointed no fewer than five female vice presidents. Susan Hockfield

Susan Hockfield (born March 24, 1951) is an American neuroscientist who served as the sixteenth president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from December 2004 through June 2012. Hockfield succeeded Charles M. Vest and was succeeded by ...

, a molecular neurobiologist

A neuroscientist (or neurobiologist) is a scientist who has specialised knowledge in neuroscience, a branch of biology that deals with the physiology, biochemistry, psychology, anatomy and molecular biology of neurons, neural circuits, and glial c ...

, became MIT's 16th president on December 6, 2004 and is the first woman to hold the post. While the student body

A students' union, also known by many other names, is a student organization present in many colleges, universities, and high schools. In higher education, the students' union is often accorded its own building on the campus, dedicated to social, ...

has become more balanced in recent years, women are still a distinct minority among faculty.

Tenure outcomes have vaulted MIT into the national spotlight on several occasions. The 1984 dismissal of David F. Noble, a historian of technology, became a cause célèbre

A cause célèbre (,''Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged'', 12th Edition, 2014. S.v. "cause célèbre". Retrieved November 30, 2018 from https://www.thefreedictionary.com/cause+c%c3%a9l%c3%a8bre ,''Random House Kernerman Webs ...

about the extent to which academics are granted "freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recogni ...

" after he published several books and papers critical of MIT's and other research universities' reliance upon financial support from corporations and the military. Former materials science professor Gretchen Kalonji sued MIT in 1994 alleging that she was denied tenure because of sexual discrimination. In 1997, the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination

The Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination (MCAD) is the primary agency for civil rights law enforcement, outreach, and training in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Following the recommendation of a 1944 committee appointed by Governor o ...

issued a probable cause finding supporting James Jennings' allegations that he was not offered reciprocal tenure in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning for a post in MIT's Community Fellow Program after the senior faculty search committee believed that he was not a top black scholar in the country. In 2006–2007, MIT's denial of tenure to African-American biological engineering professor James Sherley prompted accusations of racism in MIT's tenure process, eventually leading to a protracted public dispute with the administration, a brief hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance in which participants fast as an act of political protest, or to provoke a feeling of guilt in others, usually with the objective to achieve a specific goal, such as a policy change. Most ...

, and the resignation of Professor Frank L. Douglas in protest.

Globalization and new initiatives (2000—present)

:''Includes the administration ofSusan Hockfield

Susan Hockfield (born March 24, 1951) is an American neuroscientist who served as the sixteenth president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from December 2004 through June 2012. Hockfield succeeded Charles M. Vest and was succeeded by ...

(2004–2012)''

* In 2000, MIT extended the existing Writing Requirement to a new Communication Requirement, encompassing spoken as well as written expression, as an undergraduate degree requirement.

* In 2001, MIT announced that it planned to put many of its course materials online as part of its OpenCourseWare

OpenCourseWare (OCW) are course lessons created at universities and published for free via the Internet. OCW projects first appeared in the late 1990s, and after gaining traction in Europe and then the United States have become a worldwide means ...

project. This was largely accomplished by 2010, with material from over 2,000 courses available to all.

* Nicholas Negroponte

Nicholas Negroponte (born December 1, 1943) is a Greek American architect. He is the founder and chairman Emeritus of Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Media Lab, and also founded the One Laptop per Child Association (OLPC). Negroponte ...

of the MIT Media Lab

The MIT Media Lab is a research laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, growing out of MIT's Architecture Machine Group in the School of Architecture. Its research does not restrict to fixed academic disciplines, but draws from ...

co-founded and became head of the One Laptop per Child initiative.

* Susan Hockfield

Susan Hockfield (born March 24, 1951) is an American neuroscientist who served as the sixteenth president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from December 2004 through June 2012. Hockfield succeeded Charles M. Vest and was succeeded by ...

launched the MIT Energy Research council to explore how MIT can respond to the interdisciplinary challenges of global energy consumption.

* Consolidation of old programs like Ocean Engineering into Mechanical Engineering and emergence of interdisciplinary departments like Biological Engineering and Computational Biology.

* International collaborations and educational initiatives with University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

in England and National University of Singapore

The National University of Singapore (NUS) is a national public research university in Singapore. Founded in 1905 as the Straits Settlements and Federated Malay States Government Medical School, NUS is the oldest autonomous university in th ...

and Nanyang Technological University

The Nanyang Technological University (NTU) is a national research university in Singapore. It is the second oldest autonomous university in the country and is considered as one of the most prestigious universities in the world by various in ...

in Singapore.

* In 2016 MIT established the MIT Hong Kong Innovation Node

Response to the COVID-19 pandemic

The Institute announced they would be moving all classes online and student were told to move out of dormitories on March 10, 2020.

On July 7, 2020 the school announced that seniors would be allowed to return to campus in September with some in-person classes beginning on September 7 and other students would be granted access to school facilities and special consideration for housing on a case-by-case basis.

The Institute announced they would be moving all classes online and student were told to move out of dormitories on March 10, 2020.

On July 7, 2020 the school announced that seniors would be allowed to return to campus in September with some in-person classes beginning on September 7 and other students would be granted access to school facilities and special consideration for housing on a case-by-case basis.

Notes

References

* *Further reading

"Names on Institute Buildings Lend Inspiration to Future Scientists"

'' The Tech'', Friday, December 22, 1922 * Mindell, David, and Merritt Roe Smith

"STS.050 The History of MIT, Spring 2011."

MIT OpenCourseWare. Accessed 04 Mar 2013. *MIT Librarie

"MIT Facts/MIT History."

External links

MIT Museum

* ttp://museum.mit.edu/150/ MIT 150th Anniversary Exhibition site, collecting nominations of & comments about objects that are emblematic of MIT*

Evolution of the first-year academic experience

(with graphical timeline of Institute Requirements, Pass/Fail, and Orientation - September 21, 2018 {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of The Massachusetts Institute Of Technology History of science and technology in the United States

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of th ...

mit

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the m ...