greatest happiness principle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

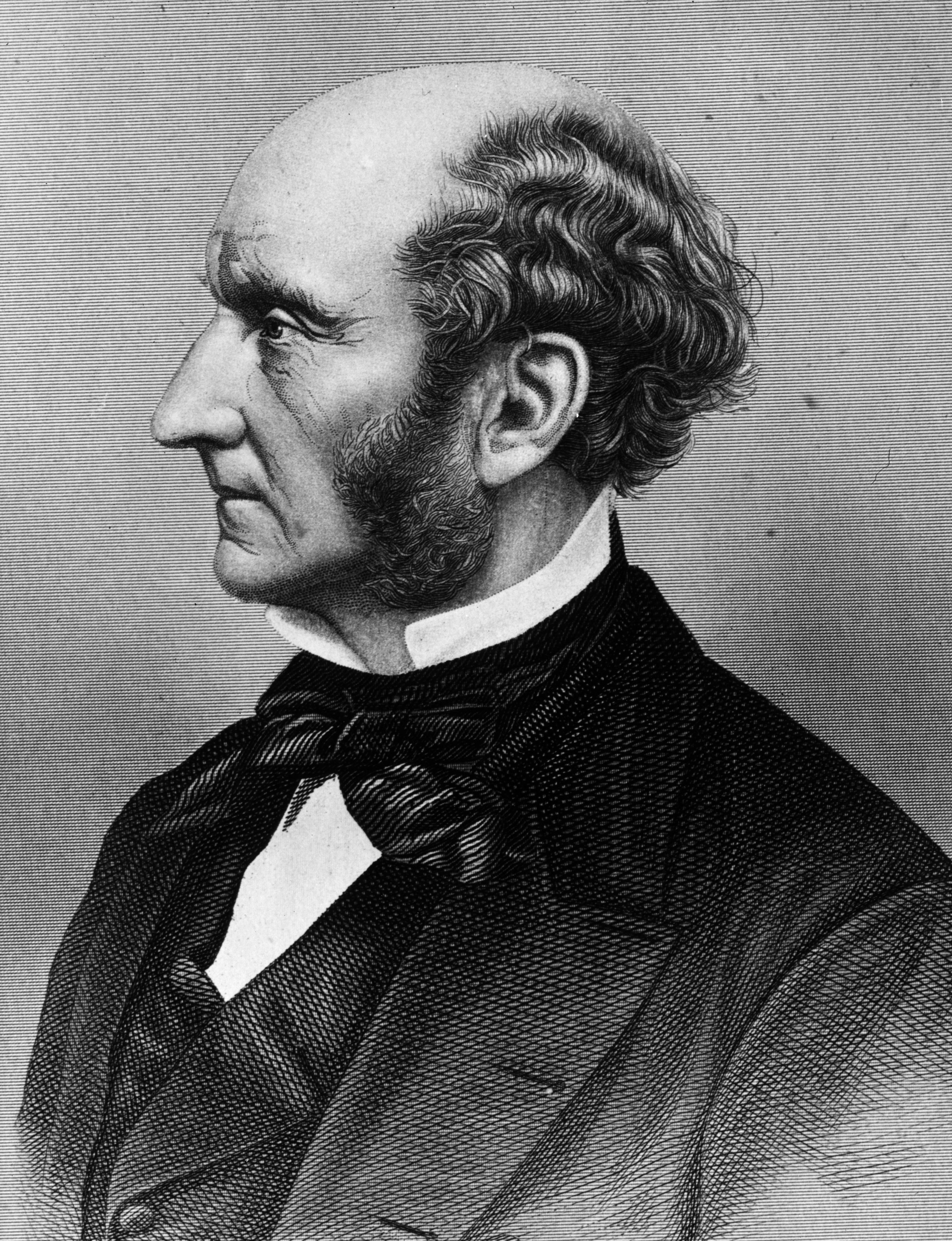

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English

pp. 21–22

. One way to read Mill's Principle of Liberty as a principle of public reason is to see it excluding certain kinds of reasons from being taken into account in legislation, or in guiding the moral coercion of public opinion. (Rawls, Lectures on the History of Political Philosophy; p. 291). These reasons include those founded in other persons good; reasons of excellence and ideals of human perfection; reasons of dislike or disgust, or of preference. Mill states that "harms" which may be prevented include acts of omission as well as acts of commission. Thus, failing to rescue a

On Liberty

''. Kitchener, ON: Batoche Books. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

''The Subjection of Women''

. ch. 1.

Mill's view of history was that right up until his time "the whole of the female" and "the great majority of the male sex" were simply "slaves". He countered arguments to the contrary, arguing that relations between sexes simply amounted to "the legal subordination of one sex to the other—

Mill's view of history was that right up until his time "the whole of the female" and "the great majority of the male sex" were simply "slaves". He countered arguments to the contrary, arguing that relations between sexes simply amounted to "the legal subordination of one sex to the other—

The canonical statement of Mill's

The canonical statement of Mill's

* Mill is the subject of a 1905

* Mill is the subject of a 1905

"Mill's Moral and Political Philosophy"

, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.) * Claeys, Gregory. ''Mill and Paternalism'' (Cambridge University Press, 2013) * Christians, Clifford G. & John C. Merrill (eds) Ethical Communication: Five Moral Stances in Human Dialogue, Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2009 * * * Gopnick, Adam

"Right Again, The passions of John Stuart Mill", ''The New Yorker'', 6 October 2008

* * Harwood, Sterling. "Eleven Objections to Utilitarianism", in Louis P. Pojman, ed., ''Moral Philosophy: A Reader'' (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Co., 1998), and in Sterling Harwood, ed., ''Business as Ethical and Business as Usual'' (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Co., 1996), Chapter 7 * Hollander, Samuel, ''The Economics of John Stuart Mill'' (University of Toronto Press, 1985) * Kolmar, Wendy & Frances Bartowski. ''Feminist Theory''. 2nd ed. New York: Mc Graw Hill, 2005 * Letwin, Letwin, ''The Pursuit of Certainty'' (Cambridge University Press, 1965). * Packe, Michael St. John, ''The Life of John Stuart Mill'' (Macmillan, 1952) * Pateman, Carole, ''Participation and Democratic Theory'' (Cambridge University Press, 1970). * Reeves, Richard, ''John Stuart Mill: Victorian Firebrand'', Atlantic Books (2007), paperback 2008. * Robinson, Dave & Groves, Judy (2003). ''Introducing Political Philosophy''. Icon Books. * Rosen, Frederick, ''Classical Utilitarianism from Hume to Mill'' (

Contents

Victorianweb.org (National University of Singapore) * Thompson, Dennis F., ''John Stuart Mill and Representative Government'' (Princeton University Press, 1976). * Thompson, Dennis F., "Mill in Parliament: When Should a Philosopher Compromise?" in ''J. S. Mill's Political Thought'', eds. N. Urbinati and A. Zakaras (Cambridge University Press, 2007). *

Bentham and Mill on the "Quality" of Pleasures

�, ''Revue d'études benthamiennes'', Paris, 2011. * Francisco Vergara, �

A Critique of Elie Halévy; refutation of an important distortion of British moral philosophy

», ''Philosophy'', Journal of The Royal Institute of Philosophy, London, 1998.

The Online Books Page

lists works on various sites

Works

readable and downloadable

Primary and secondary works

More easily readable versions of ''On Liberty'', ''Utilitarianism'', ''Three Essays on Religion'', ''The Subjection of Women'', ''A System of Logic'', and ''Autobiography''

Chapter VI of ''System of Logic'' (1859)

* ''

John Stuart Mill

in the

Catalogue of Mill's correspondence and papers

held at th

of the London School of Economics. View the Archives Catalogue of the contents of this important holding, which also includes letters of James Mill and Helen Taylor.

John Stuart Mill's library

Mill

BBC Radio 4 discussion with A. C. Grayling, Janet Radcliffe Richards & Alan Ryan (''In Our Time'', 18 May 2006) *

John Stuart Mill

on

John Stuart Mill

biographical profile, including quotes and further resources, a

Utilitarianism.net

{{DEFAULTSORT:Mill, John Stuart 1806 births 1873 deaths 19th-century British non-fiction writers 19th-century British philosophers 19th-century British writers 19th-century English philosophers 19th-century English writers 19th-century essayists Anglo-Scots British agnostics British autobiographers British classical liberals British cultural critics British economists British ethicists British radicals British feminist writers British feminists British male essayists British political philosophers British political writers British social liberals Classical economists Consequentialists Empiricists English agnostics English autobiographers English essayists English feminist writers English feminists English libertarians English logicians English male non-fiction writers English non-fiction writers English people of Scottish descent English political philosophers English political writers English social commentators English suffragists European democratic socialists Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Feminist economists Feminist philosophers Free speech activists Honorary Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Individualist feminists Infectious disease deaths in France Liberal Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies Libertarian theorists Logicians Male feminists Moral philosophers National Society for Women's Suffrage People associated with criticism of economic growth People from Pentonville Philosophers of culture Philosophers of economics Philosophers of ethics and morality Philosophers of history Philosophers of language Philosophers of logic Philosophers of mind Philosophers of psychology Philosophers of science Philosophers of sexuality Philosophy writers Political philosophers Rectors of the University of St Andrews British social commentators Social critics Social philosophers Theorists on Western civilization UK MPs 1865–1868 Utilitarians Voting theorists English republicans

philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

, political economist

Political economy is the study of how economic systems (e.g. markets and national economies) and political systems (e.g. law, institutions, government) are linked. Widely studied phenomena within the discipline are systems such as labour m ...

, Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members ofte ...

(MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to social theory

Social theories are analytical frameworks, or paradigms, that are used to study and interpret social phenomena.Seidman, S., 2016. Contested knowledge: Social theory today. John Wiley & Sons. A tool used by social scientists, social theories relat ...

, political theory

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, l ...

, and political economy. Dubbed "the most influential English-speaking philosopher of the nineteenth century", he conceived of liberty

Liberty is the ability to do as one pleases, or a right or immunity enjoyed by prescription or by grant (i.e. privilege). It is a synonym for the word freedom.

In modern politics, liberty is understood as the state of being free within society fr ...

as justifying the freedom of the individual in opposition to unlimited state and social control.

Mill was a proponent of utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charact ...

, an ethical theory developed by his predecessor Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

. He contributed to the investigation of scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientific me ...

ology, though his knowledge of the topic was based on the writings of others, notably William Whewell

William Whewell ( ; 24 May 17946 March 1866) was an English polymath, scientist, Anglican priest, philosopher, theologian, and historian of science. He was Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. In his time as a student there, he achieved dist ...

, John Herschel

Sir John Frederick William Herschel, 1st Baronet (; 7 March 1792 – 11 May 1871) was an English polymath active as a mathematician, astronomer, chemist, inventor, experimental photographer who invented the blueprint and did botanical wor ...

, and Auguste Comte

Isidore Marie Auguste François Xavier Comte (; 19 January 1798 – 5 September 1857) was a French philosopher and writer who formulated the doctrine of positivism. He is often regarded as the first philosopher of science in the modern sense of ...

, and research carried out for Mill by Alexander Bain. He engaged in written debate with Whewell.

A member of the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

and author of the early feminist work ''The Subjection of Women

''The Subjection of Women'' is an essay by English philosopher, political economist and civil servant John Stuart Mill published in 1869, with ideas he developed jointly with his wife Harriet Taylor Mill. Mill submitted the finished manuscript ...

'', Mill was also the second Member of Parliament to call for women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

after Henry Hunt in 1832.

Biography

John Stuart Mill was born at 13 Rodney Street inPentonville

Pentonville is an area on the northern fringe of Central London, in the London Borough of Islington. It is located north-northeast of Charing Cross on the Inner Ring Road. Pentonville developed in the northwestern edge of the ancient parish o ...

, Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a historic county in southeast England. Its area is almost entirely within the wider urbanised area of London and mostly within the ceremonial county of Greater London, with small sections in neighbouri ...

, the eldest son of Harriet Barrow and the Scottish philosopher, historian, and economist James Mill

James Mill (born James Milne; 6 April 1773 – 23 June 1836) was a Scottish historian, economist, political theorist, and philosopher. He is counted among the founders of the Ricardian school of economics. He also wrote '' The History of Britis ...

. John Stuart was educated by his father, with the advice and assistance of Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

and Francis Place

Francis Place (3 November 1771 in London – 1 January 1854 in London) was an English social reformer.

Early life

He was an illegitimate son of Simon Place and Mary Gray. His father was originally a journeyman baker. He then became a Marshalse ...

. He was given an extremely rigorous upbringing, and was deliberately shielded from association with children his own age other than his siblings. His father, a follower of Bentham and an adherent of associationism

Associationism is the idea that mental processes operate by the association of one mental state with its successor states. It holds that all mental processes are made up of discrete psychological elements and their combinations, which are believed ...

, had as his explicit aim to create a genius

Genius is a characteristic of original and exceptional insight in the performance of some art or endeavor that surpasses expectations, sets new standards for future works, establishes better methods of operation, or remains outside the capabiliti ...

intellect that would carry on the cause of utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charact ...

and its implementation after he and Bentham had died.

Mill was a notably precocious child. He describes his education in his autobiography. At the age of three he was taught Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

. By the age of eight, he had read ''Aesop's Fables

Aesop's Fables, or the Aesopica, is a collection of fables credited to Aesop, a slave and storyteller believed to have lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 564 BCE. Of diverse origins, the stories associated with his name have descended to m ...

'', Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Greek mercenary armies o ...

's ''Anabasis

Anabasis (from Greek ''ana'' = "upward", ''bainein'' = "to step or march") is an expedition from a coastline into the interior of a country. Anabase and Anabasis may also refer to:

History

* ''Anabasis Alexandri'' (''Anabasis of Alexander''), a ...

'', and the whole of Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known for ha ...

, and was acquainted with Lucian

Lucian of Samosata, '; la, Lucianus Samosatensis ( 125 – after 180) was a Hellenized Syrian satirist, rhetorician and pamphleteer who is best known for his characteristic tongue-in-cheek style, with which he frequently ridiculed superstitio ...

, Diogenes Laërtius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; grc-gre, Διογένης Λαέρτιος, ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal sourc ...

, Isocrates

Isocrates (; grc, Ἰσοκράτης ; 436–338 BC) was an ancient Greek rhetorician, one of the ten Attic orators. Among the most influential Greek rhetoricians of his time, Isocrates made many contributions to rhetoric and education throu ...

and six dialogues of Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, wikt:Πλάτων, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greeks, Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thou ...

. He had also read a great deal of history in English and had been taught arithmetic

Arithmetic () is an elementary part of mathematics that consists of the study of the properties of the traditional operations on numbers—addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, exponentiation, and extraction of roots. In the 19th c ...

, physics and astronomy.

At the age of eight, Mill began studying Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, the works of Euclid

Euclid (; grc-gre, Εὐκλείδης; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the ''Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of ge ...

, and algebra

Algebra () is one of the broad areas of mathematics. Roughly speaking, algebra is the study of mathematical symbols and the rules for manipulating these symbols in formulas; it is a unifying thread of almost all of mathematics.

Elementary a ...

, and was appointed schoolmaster to the younger children of the family. His main reading was still history, but he went through all the commonly taught Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

authors and by the age of ten could read Plato and Demosthenes with ease. His father also thought that it was important for Mill to study and compose poetry. One of his earliest poetic compositions was a continuation of the ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyss ...

''. In his spare time he also enjoyed reading about natural sciences and popular novels, such as ''Don Quixote

is a Spanish epic novel by Miguel de Cervantes. Originally published in two parts, in 1605 and 1615, its full title is ''The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha'' or, in Spanish, (changing in Part 2 to ). A founding work of Western ...

'' and ''Robinson Crusoe

''Robinson Crusoe'' () is a novel by Daniel Defoe, first published on 25 April 1719. The first edition credited the work's protagonist Robinson Crusoe as its author, leading many readers to believe he was a real person and the book a tra ...

''.

His father's work, ''The History of British India

''The History of British India'' is a three-volume work by the Scottish historian, economist, political theorist, and philosopher James Mill, charting the history of Company rule in India. The work, first published in 1817, was an instant succes ...

'', was published in 1818; immediately thereafter, at about the age of twelve, Mill began a thorough study of the scholastic logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premises ...

, at the same time reading Aristotle's logical treatises in the original language. In the following year he was introduced to political economy

Political economy is the study of how economic systems (e.g. markets and national economies) and political systems (e.g. law, institutions, government) are linked. Widely studied phenomena within the discipline are systems such as labour m ...

and studied Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——� ...

and David Ricardo

David Ricardo (18 April 1772 – 11 September 1823) was a British political economist. He was one of the most influential of the classical economists along with Thomas Malthus, Adam Smith and James Mill. Ricardo was also a politician, and a m ...

with his father, ultimately completing their classical economic view of factors of production

In economics, factors of production, resources, or inputs are what is used in the production process to produce output—that is, goods and services. The utilized amounts of the various inputs determine the quantity of output according to the rel ...

. Mill's ''comptes rendus'' of his daily economy lessons helped his father in writing ''Elements of Political Economy'' in 1821, a textbook to promote the ideas of Ricardian economics

Ricardian economics are the economic theories of David Ricardo, an English political economist born in 1772 who made a fortune as a stockbroker and loan broker.Henderson 826Fusfeld 325 At the age of 27, he read '' An Inquiry into the Nature and ...

; however, the book lacked popular support. Ricardo, who was a close friend of his father, used to invite the young Mill to his house for a walk to talk about political economy

Political economy is the study of how economic systems (e.g. markets and national economies) and political systems (e.g. law, institutions, government) are linked. Widely studied phenomena within the discipline are systems such as labour m ...

.

At the age of fourteen, Mill stayed a year in France with the family of Sir Samuel Bentham

Sir Samuel Bentham (11 January 1757 – 31 May 1831) was a noted English mechanical engineer and naval architect credited with numerous innovations, particularly related to naval architecture, including weapons. He was the only surviving siblin ...

, brother of Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

. The mountain scenery he saw led to a lifelong taste for mountain landscapes. The lively and friendly way of life of the French also left a deep impression on him. In Montpellier

Montpellier (, , ; oc, Montpelhièr ) is a city in southern France near the Mediterranean Sea. One of the largest urban centres in the region of Occitania, Montpellier is the prefecture of the department of Hérault. In 2018, 290,053 people l ...

, he attended the winter courses on chemistry, zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and dis ...

, logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premises ...

of the ''Faculté des Sciences'', as well as taking a course in higher mathematics. While coming and going from France, he stayed in Paris for a few days in the house of the renowned economist Jean-Baptiste Say

Jean-Baptiste Say (; 5 January 1767 – 15 November 1832) was a liberal French economist and businessman who argued in favor of competition, free trade and lifting restraints on business. He is best known for Say's law—also known as the law of ...

, a friend of Mill's father. There he met many leaders of the Liberal party, as well as other notable Parisians, including Henri Saint-Simon.

Mill went through months of sadness and contemplated suicide at twenty years of age. According to the opening paragraphs of Chapter V of his autobiography, he had asked himself whether the creation of a just society, his life's objective, would actually make him happy. His heart answered "no", and unsurprisingly he lost the happiness of striving towards this objective. Eventually, the poetry of William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication ''Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ' ...

showed him that beauty generates compassion for others and stimulates joy. With renewed joy he continued to work towards a just society, but with more relish for the journey. He considered this one of the most pivotal shifts in his thinking. In fact, many of the differences between him and his father stemmed from this expanded source of joy.

Mill met Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, Dum ...

during one of the latter's visits to London in the early 1830s, and the two quickly became companions and correspondents. Mill offered to print Carlyle's works at his own expense and encouraged Carlyle to write his ''French Revolution'', supplying him with materials in order to do so. In March 1835, while the manuscript of the completed first volume was in Mill's possession, Mill's housemaid unwittingly used it as tinder, destroying all "except some three or four bits of leaves". Mortified, Mill offered Carlyle £200 (£17,742.16 in 2021) as compensation (Carlyle would only accept £100). Ideological differences would put an end to the friendship during the 1840s, though Carlyle's early influence on Mill would colour his later thought.

Mill had been engaged in a pen-friendship with Auguste Comte

Isidore Marie Auguste François Xavier Comte (; 19 January 1798 – 5 September 1857) was a French philosopher and writer who formulated the doctrine of positivism. He is often regarded as the first philosopher of science in the modern sense of ...

, the founder of positivism

Positivism is an empiricist philosophical theory that holds that all genuine knowledge is either true by definition or positive—meaning ''a posteriori'' facts derived by reason and logic from sensory experience.John J. Macionis, Linda M. G ...

and sociology, since Mill first contacted Comte in November 1841. Comte's ''sociologie'' was more an early philosophy of science

Philosophy of science is a branch of philosophy concerned with the foundations, methods, and implications of science. The central questions of this study concern what qualifies as science, the reliability of scientific theories, and the ulti ...

than modern sociology is. Comte's positivism motivated Mill to eventually reject Bentham's psychological egoism

Psychological egoism is the view that humans are always motivated by self-interest and selfishness, even in what seem to be acts of altruism. It claims that, when people choose to help others, they do so ultimately because of the personal benefit ...

and what he regarded as Bentham's cold, abstract view of human nature focused on legislation and politics, instead coming to favour Comte's more sociable view of human nature focused on historical facts and directed more towards human individuals in all their complexities.

As a nonconformist who refused to subscribe to the Thirty-Nine Articles

The Thirty-nine Articles of Religion (commonly abbreviated as the Thirty-nine Articles or the XXXIX Articles) are the historically defining statements of doctrines and practices of the Church of England with respect to the controversies of the ...

of the Church of England, Mill was not eligible to study at the University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

or the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

.Capaldi, Nicholas. ''John Stuart Mill: A Biography.'' p. 33, Cambridge, 2004, . Instead he followed his father to work for the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

, and attended University College

In a number of countries, a university college is a college institution that provides tertiary education but does not have full or independent university status. A university college is often part of a larger university. The precise usage varies ...

, London, to hear the lectures of John Austin John Austin may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* John P. Austin (1906–1997), American set decorator

* Johnny Austin (1910–1983), American musician

* John Austin (author) (fl. 1940s), British novelist

Military

* John Austin (soldier) (180 ...

, the first Professor of Jurisprudence. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and ...

in 1856.

Mill's career as a colonial administrator at the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

spanned from when he was 17 years old in 1823 until 1858, when the Company's territories in India were directly annexed by the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

, establishing direct Crown control over India. In 1836, he was promoted to the Company's Political Department, where he was responsible for correspondence pertaining to the Company's relations with the princely state

A princely state (also called native state or Indian state) was a nominally sovereign entity of the British Indian Empire that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule, subject to ...

s, and in 1856, was finally promoted to the position of Examiner of Indian Correspondence. In ''On Liberty

''On Liberty'' is a philosophical essay by the English philosopher John Stuart Mill. Published in 1859, it applies Mill's ethical system of utilitarianism to society and state. Mill suggests standards for the relationship between authority an ...

'', '' A Few Words on Non-Intervention'', and other works, he opined that "To characterize any conduct whatever towards a barbarous people as a violation of the law of nations, only shows that he who so speaks has never considered the subject". (Mill immediately added, however, that "A violation of the great principles of morality it may easily be.") Mill viewed places such as India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

as having once been progressive in their outlook, but had now become stagnant in their development; he opined that this meant these regions had to be ruled via a form of " benevolent despotism", "provided the end is improvement". When the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

proposed to take direct control over the territories of the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

, he was tasked with defending Company rule, penning ''Memorandum on the Improvements in the Administration of India during the Last Thirty Years'' among other petitions. Lal, Vinay. 1998. "'John Stuart Mill and India', a review-article". ''New Quest'' 54(1):54–64. He was offered a seat on the Council of India

The Council of India was the name given at different times to two separate bodies associated with British rule in India.

The original Council of India was established by the Charter Act of 1833 as a council of four formal advisors to the Governor ...

, the body created to advise the new Secretary of State for India

His (or Her) Majesty's Principal Secretary of State for India, known for short as the India Secretary or the Indian Secretary, was the British Cabinet minister and the political head of the India Office responsible for the governance of t ...

, but declined, citing his disapproval of the new system of administration in India.

On 21 April 1851, Mill married Harriet Taylor after 21 years of intimate friendship. Taylor was married when they met, and their relationship was close but generally believed to be chaste during the years before her first husband died in 1849. The couple waited two years before marrying in 1851. Brilliant in her own right, Taylor was a significant influence on Mill's work and ideas during both friendship and marriage. His relationship with Taylor reinforced Mill's advocacy of women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

. He said that in his stand against domestic violence, and for women's rights he was "chiefly an amanuensis to my wife". He called her mind a "perfect instrument", and said she was "the most eminently qualified of all those known to the author". He cites her influence in his final revision of ''On Liberty

''On Liberty'' is a philosophical essay by the English philosopher John Stuart Mill. Published in 1859, it applies Mill's ethical system of utilitarianism to society and state. Mill suggests standards for the relationship between authority an ...

'', which was published shortly after her death. Taylor died in 1858 after developing severe lung congestion, after only seven years of marriage to Mill.

Between the years 1865 and 1868 Mill served as Lord Rector

A rector (Latin for 'ruler') is a senior official in an educational institution, and can refer to an official in either a university or a secondary school. Outside the English-speaking world the rector is often the most senior official in a un ...

of the University of St Andrews

(Aien aristeuein)

, motto_lang = grc

, mottoeng = Ever to ExcelorEver to be the Best

, established =

, type = Public research university

Ancient university

, endowment ...

. At his inaugural address, delivered to the University on 1 February 1867, he made the now-famous (but often wrongly attributed) remark that "Bad men need nothing more to compass their ends, than that good men should look on and do nothing". That Mill included that sentence in the address is a matter of historical record, but it by no means follows that it expressed a wholly original insight. During the same period, 1865–68, he was also a Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members ofte ...

(MP) for City of Westminster

The City of Westminster is a city and borough in Inner London. It is the site of the United Kingdom's Houses of Parliament and much of the British government. It occupies a large area of central Greater London, including most of the West En ...

.Capaldi, Nicholas. ''John Stuart Mill: A Biography.'' pp. 321–322, Cambridge, 2004, . He was sitting for the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

. During his time as an MP, Mill advocated easing the burdens on Ireland. In 1866, he became the first person in the history of Parliament to call for women to be given the right to vote, vigorously defending this position in subsequent debate. He also became a strong advocate of such social reforms as labour unions and farm cooperatives. In ''Considerations on Representative Government

''Considerations on Representative Government'' is a book by John Stuart Mill published in 1861.

Summary

Mill argues for representative government, the ideal form of government in his opinion. One of the more notable ideas Mill puts forth in the ...

'', he called for various reforms of Parliament and voting, especially proportional representation

Proportional representation (PR) refers to a type of electoral system under which subgroups of an electorate are reflected proportionately in the elected body. The concept applies mainly to geographical (e.g. states, regions) and political divis ...

, the single transferable vote, and the extension of suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

. In April 1868, he favoured in a Commons debate the retention of capital punishment for such crimes as aggravated murder; he termed its abolition "an effeminacy in the general mind of the country". Sher, George, ed. 2001. ''Utilitarianism and the 1868 Speech on Capital Punishment'', by J. S. Mill. Hackett Publishing Co.

He was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

in 1867.

He was godfather to the philosopher Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, ar ...

.

In his views on religion, Mill was an agnostic and a sceptic

Skepticism, also spelled scepticism, is a questioning attitude or doubt toward knowledge claims that are seen as mere belief or dogma. For example, if a person is skeptical about claims made by their government about an ongoing war then the pe ...

.

Mill died in 1873, thirteen days before his 67th birthday, of erysipelas

Erysipelas () is a relatively common bacterial infection of the superficial layer of the skin ( upper dermis), extending to the superficial lymphatic vessels within the skin, characterized by a raised, well-defined, tender, bright red rash, t ...

in Avignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label= Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of Southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the commune ha ...

, France, where his body was buried alongside his wife's.

Works and theories

''A System of Logic''

Mill joined the debate overscientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientific me ...

which followed on from John Herschel

Sir John Frederick William Herschel, 1st Baronet (; 7 March 1792 – 11 May 1871) was an English polymath active as a mathematician, astronomer, chemist, inventor, experimental photographer who invented the blueprint and did botanical wor ...

's 1830 publication of ''A Preliminary Discourse on the study of Natural Philosophy'', which incorporated inductive reasoning

Inductive reasoning is a method of reasoning in which a general principle is derived from a body of observations. It consists of making broad generalizations based on specific observations. Inductive reasoning is distinct from ''deductive'' rea ...

from the known to the unknown, discovering general laws in specific facts and verifying these laws empirically. William Whewell

William Whewell ( ; 24 May 17946 March 1866) was an English polymath, scientist, Anglican priest, philosopher, theologian, and historian of science. He was Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. In his time as a student there, he achieved dist ...

expanded on this in his 1837 ''History of the Inductive Sciences, from the Earliest to the Present Time'', followed in 1840 by ''The Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences, Founded Upon their History'', presenting induction as the mind superimposing concepts on facts. Laws were self-evident

In epistemology (theory of knowledge), a self-evident proposition is a proposition that is known to be true by understanding its meaning without proof, and/or by ordinary human reason.

Some epistemologists deny that any proposition can be self-e ...

truths, which could be known without need for empirical verification.

Mill countered this in 1843 in ''A System of Logic

''A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive'' is an 1843 book by English philosopher John Stuart Mill.

Overview

In this work, he formulated the five principles of inductive reasoning that are known as Mill's Methods. This work is important i ...

'' (fully titled ''A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive, Being a Connected View of the Principles of Evidence, and the Methods of Scientific Investigation''). In "Mill's Methods

Mill's Methods are five methods of induction described by philosopher John Stuart Mill in his 1843 book '' A System of Logic''. They are intended to illuminate issues of causation.

The methods

Direct method of agreement

For a property to be ...

" (of induction), as in Herschel's, laws were discovered through observation and induction, and required empirical verification. Matilal remarks that Dignāga

Dignāga (a.k.a. ''Diṅnāga'', c. 480 – c. 540 CE) was an Indian Buddhist scholar and one of the Buddhist founders of Indian logic (''hetu vidyā''). Dignāga's work laid the groundwork for the development of deductive logic in India and cr ...

analysis is much like John Stuart Mill's Joint Method of Agreement and Difference, which is inductive. He suggested that it is very likely that during his stay in India he may have come across the tradition of logic, on which scholars started taking interest after 1824, though it is unknown whether it influenced his work or not.

Theory of liberty

Mill's ''On Liberty

''On Liberty'' is a philosophical essay by the English philosopher John Stuart Mill. Published in 1859, it applies Mill's ethical system of utilitarianism to society and state. Mill suggests standards for the relationship between authority an ...

'' (1859) addresses the nature and limits of the power

Power most often refers to:

* Power (physics), meaning "rate of doing work"

** Engine power, the power put out by an engine

** Electric power

* Power (social and political), the ability to influence people or events

** Abusive power

Power may ...

that can be legitimately exercised by society over the individual

An individual is that which exists as a distinct entity. Individuality (or self-hood) is the state or quality of being an individual; particularly (in the case of humans) of being a person unique from other people and possessing one's own need ...

. Mill's idea is that only if a democratic society follows the Principle of Liberty can its political and social institutions fulfill their role of shaping national character so that its citizens can realise the permanent interests of people as progressive beings (Rawls, Lectures on the History of Political Philosophy; p 289).

Mill states the Principle of Liberty as: "the sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection". "The only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant."Mill, John Stuart. 859

__FORCETOC__

Year 859 ( DCCCLIX) was a common year starting on Sunday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Europe

* January 15 – Battle of St. Quentin: Frankish forces, led by Humfrid, d ...

1869. ''On Liberty'' (4th ed.). London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyerpp. 21–22

. One way to read Mill's Principle of Liberty as a principle of public reason is to see it excluding certain kinds of reasons from being taken into account in legislation, or in guiding the moral coercion of public opinion. (Rawls, Lectures on the History of Political Philosophy; p. 291). These reasons include those founded in other persons good; reasons of excellence and ideals of human perfection; reasons of dislike or disgust, or of preference. Mill states that "harms" which may be prevented include acts of omission as well as acts of commission. Thus, failing to rescue a

drowning

Drowning is a type of suffocation induced by the submersion of the mouth and nose in a liquid. Most instances of fatal drowning occur alone or in situations where others present are either unaware of the victim's situation or unable to offer a ...

child counts as a harmful act, as does failing to pay taxes

A tax is a compulsory financial charge or some other type of levy imposed on a taxpayer (an individual or legal entity) by a governmental organization in order to fund government spending and various public expenditures (regional, local, or n ...

, or failing to appear as a witness

In law, a witness is someone who has knowledge about a matter, whether they have sensed it or are testifying on another witnesses' behalf. In law a witness is someone who, either voluntarily or under compulsion, provides testimonial evidence, e ...

in court. All such harmful omissions may be regulated, according to Mill. By contrast, it does not count as harming someone if—without force or fraud—the affected individual consent

Consent occurs when one person voluntarily agrees to the proposal or desires of another. It is a term of common speech, with specific definitions as used in such fields as the law, medicine, research, and sexual relationships. Consent as und ...

s to assume the risk: thus one may permissibly offer unsafe employment to others, provided there is no deception involved. (He does, however, recognise one limit to consent: society should not permit people to sell themselves into slavery.)

The question of what counts as a self-regarding action and what actions, whether of omission or commission, constitute harmful actions subject to regulation, continues to exercise interpreters of Mill. He did not consider giving offence to constitute "harm"; an action could not be restricted because it violated the conventions or morals of a given society.Mill, John Stuart. 859

__FORCETOC__

Year 859 ( DCCCLIX) was a common year starting on Sunday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Europe

* January 15 – Battle of St. Quentin: Frankish forces, led by Humfrid, d ...

2001. On Liberty

''. Kitchener, ON: Batoche Books. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

Social liberty and tyranny of majority

Mill believed that "the struggle betweenLiberty

Liberty is the ability to do as one pleases, or a right or immunity enjoyed by prescription or by grant (i.e. privilege). It is a synonym for the word freedom.

In modern politics, liberty is understood as the state of being free within society fr ...

and Authority

In the fields of sociology and political science, authority is the legitimate power of a person or group over other people. In a civil state, ''authority'' is practiced in ways such a judicial branch or an executive branch of government.''The Ne ...

is the most conspicuous feature in the portions of history." For him, liberty in antiquity was a "contest…between subjects, or some classes of subjects, and the government."

Mill defined '' social liberty'' as protection from "the tyranny

A tyrant (), in the modern English usage of the word, is an absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defend their positions by resorting to r ...

of political rulers". He introduced a number of different concepts of the form tyranny can take, referred to as social tyranny, and ''tyranny of the majority

The tyranny of the majority (or tyranny of the masses) is an inherent weakness to majority rule in which the majority of an electorate pursues exclusively its own objectives at the expense of those of the minority factions. This results in oppres ...

''. ''Social liberty'' for Mill meant putting limits on the ruler's power so that he would not be able to use that power to further his own wishes and thus make decisions that could harm society. In other words, people should have the right to have a say in the government's decisions. He said that ''social liberty'' was "the nature and limits of the power which can be legitimately exercised by society over the individual." It was attempted in two ways: first, by obtaining recognition of certain immunities (called ''political liberties'' or ''rights''); and second, by establishment of a system of "constitutional

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princi ...

checks".

However, in Mill's view, limiting the power of government was not enough:Society can and does execute its own mandates: and if it issues wrong mandates instead of right, or any mandates at all in things with which it ought not to meddle, it practises a social tyranny more formidable than many kinds of political oppression, since, though not usually upheld by such extreme penalties, it leaves fewer means of escape, penetrating much more deeply into the details of life, and enslaving the soul itself.

Liberty

Mill's view onliberty

Liberty is the ability to do as one pleases, or a right or immunity enjoyed by prescription or by grant (i.e. privilege). It is a synonym for the word freedom.

In modern politics, liberty is understood as the state of being free within society fr ...

, which was influenced by Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted exp ...

and Josiah Warren

Josiah Warren (; 1798–1874) was an American utopian socialist, American individualist anarchist, individualist philosopher, polymath, social reformer, inventor, musician, printer and author. He is regarded by anarchist historians like James ...

, is that individuals

An individual is that which exists as a distinct entity. Individuality (or self-hood) is the state or quality of being an individual; particularly (in the case of humans) of being a person unique from other people and possessing one's own need ...

ought to be free to do as they wished unless they caused harm to others. Individuals are rational enough to make decisions about their well being. Government should interfere when it is for the protection of society. Mill explained:

The sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection. That the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not sufficient warrant. He cannot rightfully be compelled to do or forbear because it will be better for him to do so, because it will make him happier, because, in the opinion of others, to do so would be wise, or even right.… The only part of the conduct of anyone, for which he is amenable to society, is that which concerns others. In the part which merely concerns him, his independence is, of right,absolute Absolute may refer to: Companies * Absolute Entertainment, a video game publisher * Absolute Radio, (formerly Virgin Radio), independent national radio station in the UK * Absolute Software Corporation, specializes in security and data risk manag .... Over himself, over his own body and mind, theindividual An individual is that which exists as a distinct entity. Individuality (or self-hood) is the state or quality of being an individual; particularly (in the case of humans) of being a person unique from other people and possessing one's own need ...issovereign ''Sovereign'' is a title which can be applied to the highest leader in various categories. The word is borrowed from Old French , which is ultimately derived from the Latin , meaning 'above'. The roles of a sovereign vary from monarch, ruler or ....

Freedom of speech

''On Liberty'' involves an impassioned defense offree speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recogn ...

. Mill argues that free discourse

Discourse is a generalization of the notion of a conversation to any form of communication. Discourse is a major topic in social theory, with work spanning fields such as sociology, anthropology, continental philosophy, and discourse analysis. ...

is a necessary condition

In logic and mathematics, necessity and sufficiency are terms used to describe a conditional or implicational relationship between two statements. For example, in the conditional statement: "If then ", is necessary for , because the truth of ...

for intellectual and social progress

Progress is the movement towards a refined, improved, or otherwise desired state. In the context of progressivism, it refers to the proposition that advancements in technology, science, and social organization have resulted, and by extension wi ...

. We can never be sure, he contends, that a silenced opinion does not contain some element of the truth. He also argues that allowing people to air false opinions is productive for two reasons. First, individuals are more likely to abandon erroneous beliefs if they are engaged in an open exchange of ideas. Second, by forcing other individuals to re-examine and re-affirm their beliefs in the process of debate, these beliefs are kept from declining into mere dogma

Dogma is a belief or set of beliefs that is accepted by the members of a group without being questioned or doubted. It may be in the form of an official system of principles or doctrines of a religion, such as Roman Catholicism, Judaism, Islam o ...

. It is not enough for Mill that one simply has an unexamined belief that happens to be true; one must understand why the belief in question is the true one. Along those same lines Mill wrote, "unmeasured vituperation, employed on the side of prevailing opinion, really does deter people from expressing contrary opinions, and from listening to those who express them."

As an influential advocate of freedom of speech, Mill objected to censorship:

I choose, by preference the cases which are least favourable to me—In which the argument opposing freedom of opinion, both on truth and that ofMill outlines the benefits of "searching for and discovering the truth" as a way to further knowledge. He argued that even if an opinion is false, the truth can be better understood by refuting the error. And as most opinions are neither completely true nor completely false, he points out that allowing free expression allows the airing of competing views as a way to preserve partial truth in various opinions.Paul, Ellen Frankel, Fred Dycus Miller, and Jeffrey Paul. 2004. ''Freedom of Speech'' 21. Cambridge University Press. Worried about minority views being suppressed, he argued in support of freedom of speech on political grounds, stating that it is a critical component for autility As a topic of economics, utility is used to model worth or value. Its usage has evolved significantly over time. The term was introduced initially as a measure of pleasure or happiness as part of the theory of utilitarianism by moral philosophe ..., is considered the strongest. Let the opinions impugned be the belief of God and in a future state, or any of the commonly received doctrines of morality ... But I must be permitted to observe that it is not the feeling sure of a doctrine (be it what it may) which I call an assumption ofinfallibility Infallibility refers to an inability to be wrong. It can be applied within a specific domain, or it can be used as a more general adjective. The term has significance in both epistemology and theology, and its meaning and significance in both fi .... It is the undertaking to decide that question ''for others'', without allowing them to hear what can be said on the contrary side. And I denounce and reprobate this pretension not the less if it is put forth on the side of my most solemn convictions. However positive anyone's persuasion may be, not only of the faculty but of the pernicious consequences, but (to adopt expressions which I altogether condemn) the immorality and impiety of opinion.—yet if, in pursuance of that private judgement, though backed by the public judgement of his country or contemporaries, he prevents the opinion from being heard in its defence, he assumes infallibility. And so far from the assumption being less objectionable or less dangerous because the opinion is called immoral or impious, this is the case of all others in which it is most fatal.

representative government

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy, is a type of democracy where elected people represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearly all modern Western-style democracies function as some type of represen ...

to have to empower debate over public policy

Public policy is an institutionalized proposal or a decided set of elements like laws, regulations, guidelines, and actions to solve or address relevant and real-world problems, guided by a conception and often implemented by programs. Public ...

. He also eloquently argued that freedom of expression allows for personal growth

Personal development or self improvement consists of activities that develop a person's capabilities and potential, build human capital, facilitate employability, and enhance quality of life and the realization of dreams and aspirations. Personal ...

and self-realization

Self-realization is an expression used in Western psychology, philosophy, and spirituality; and in Indian religions. In the Western understanding, it is the "fulfillment by oneself of the possibilities of one's character or personality" (see ...

. He said that freedom of speech was a vital way to develop talents and realise a person's potential and creativity. He repeatedly said that eccentricity was preferable to uniformity and stagnation.

=Harm principle

= The belief that freedom of speech would advance societypresupposed

In the branch of linguistics known as pragmatics, a presupposition (or PSP) is an implicit assumption about the world or background belief relating to an utterance whose truth is taken for granted in discourse. Examples of presuppositions include ...

a society sufficiently culturally and institutionally advanced to be capable of progressive improvement. If any argument is really wrong or harmful, the public will judge it as wrong or harmful, and then those arguments cannot be sustained and will be excluded. Mill argued that even any arguments which are used in justifying murder or rebellion against the government shouldn't be politically suppressed or socially persecuted. According to him, if rebellion is really necessary, people should rebel; if murder is truly proper, it should be allowed. However, the way to express those arguments should be a public speech or writing, not in a way that causes actual harm to others. Such is the ''harm principle

The harm principle holds that the actions of individuals should only be limited to prevent harm to other individuals. John Stuart Mill articulated this principle in ''On Liberty'', where he argued that "The only purpose for which power can be rig ...

'': "That the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilised community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others."

At the beginning of the 20th century, Associate justice

Associate justice or associate judge (or simply associate) is a judicial panel member who is not the chief justice in some jurisdictions. The title "Associate Justice" is used for members of the Supreme Court of the United States and some state ...

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. (March 8, 1841 – March 6, 1935) was an American jurist and legal scholar who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1902 to 1932.Holmes was Acting Chief Justice of the Un ...

made the standard of "clear and present danger" based on Mill's idea. In the majority opinion, Holmes writes:

The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent.Holmes suggested that falsely shouting out "Fire!" in a dark theatre, which evokes panic and provokes injury, would be such a case of speech that creates an illegal danger. But if the situation allows people to

reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, lang ...

by themselves and decide to accept it or not, any argument or theology should not be blocked.

Nowadays, Mill's argument is generally accepted by many democratic countries, and they have laws at least guided by the harm principle. For example, in American law some exceptions limit free speech such as obscenity

An obscenity is any utterance or act that strongly offends the prevalent morality of the time. It is derived from the Latin ''obscēnus'', ''obscaenus'', "boding ill; disgusting; indecent", of uncertain etymology. Such loaded language can be us ...

, defamation

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defin ...

, breach of peace, and "fighting words

Fighting words are written or spoken words intended to incite hatred or violence from their target. Specific definitions, freedoms, and limitations of fighting words vary by jurisdiction. The term ''fighting words'' is also used in a general sens ...

".

=Freedom of the press

= In ''On Liberty'', Mill thought it was necessary for him to restate the case for press freedom. He considered that argument already won. Almost no politician or commentator in mid-19th-century Britain wanted a return to Tudor and Stuart-type press censorship. However, Mill warned new forms of censorship could emerge in the future. Indeed, in 2013 the Cameron Tory government considered setting up a so-called independent official regulator of the UK press. This prompted demands for better basic legal protection of press freedom. A new British Bill of Rights could include a US-type constitutional ban on governmental infringement of press freedom and block other official attempts to control freedom of opinion and expression.Colonialism

Mill, an employee of theEast India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

from 1823 to 1858, argued in support of what he called a "benevolent despotism" with regard to the administration of overseas colonies. Mill argued:To suppose that the same international customs, and the same rules of international morality, can obtain between one civilized nation and another, and between civilized nations and barbarians, is a grave error.… To characterize any conduct whatever towards a barbarous people as a violation of the law of nations, only shows that he who so speaks has never considered the subject.Mill expressed general support for

Company rule in India

Company rule in India (sometimes, Company ''Raj'', from hi, rāj, lit=rule) refers to the rule of the British East India Company on the Indian subcontinent. This is variously taken to have commenced in 1757, after the Battle of Plassey, when ...

, but expressed reservations on specific Company policies in India which he disagreed with.

Slavery and racial equality

In 1850, Mill sent an anonymous letter (which came to be known under the title " The Negro Question"), in rebuttal toThomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, Dum ...

's anonymous letter to ''Fraser's Magazine

''Fraser's Magazine for Town and Country'' was a general and literary journal published in London from 1830 to 1882, which initially took a strong Tory line in politics. It was founded by Hugh Fraser and William Maginn in 1830 and loosely direct ...

for Town and Country'' in which Carlyle argued for slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. Mill supported abolishing slavery in the United States, expressing his opposition to slavery in his essay of 1869, ''The Subjection of Women

''The Subjection of Women'' is an essay by English philosopher, political economist and civil servant John Stuart Mill published in 1869, with ideas he developed jointly with his wife Harriet Taylor Mill. Mill submitted the finished manuscript ...

'':Mill, John Stuart. 1869''The Subjection of Women''

. ch. 1.

This absolutely extreme case of the law of force, condemned by those who can tolerate almost every other form of arbitrary power, and which, of all others, presents features the most revolting to the feeling of all who look at it from an impartial position, was the law of civilized and Christian England within the memory of persons now living: and in one half of Anglo-Saxon America three or four years ago, not only did slavery exist, but the slave trade, and the breeding of slaves expressly for it, was a general practice between slave states. Yet not only was there a greater strength of sentiment against it, but, in England at least, a less amount either of feeling or of interest in favour of it, than of any other of the customary abuses of force: for its motive was the love of gain, unmixed and undisguised: and those who profited by it were a very small numerical fraction of the country, while the natural feeling of all who were not personally interested in it, was unmitigated abhorrence.Mill corresponded with John Appleton, an American legal reformer from

Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and ...

, extensively on the topic of racial equality. Appleton influenced Mill's work on such, especially swaying him on the optimal economic

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with the p ...

and social welfare

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifical ...

plan for the Antebellum South

In the history of the Southern United States, the Antebellum Period (from la, ante bellum, lit= before the war) spanned the end of the War of 1812 to the start of the American Civil War in 1861. The Antebellum South was characterized by the ...

. In a letter sent to Appleton in response to a previous letter, Mill expressed his view on antebellum integration:I cannot look forward with satisfaction to any settlement but complete emancipation—land given to every negro family either separately or in organized communities under such rules as may be found temporarily necessary—the schoolmaster set to work in every village & the tide of free immigration turned on in those fertile regions from which slavery has hitherto excluded it. If this be done, the gentle & docile character which seems to distinguish the negroes will prevent any mischief on their side, while the proofs they are giving of fighting powers will do more in a year than all other things in a century to make the whites respect them & consent to their being politically & socially equals.

Women's rights

Mill's view of history was that right up until his time "the whole of the female" and "the great majority of the male sex" were simply "slaves". He countered arguments to the contrary, arguing that relations between sexes simply amounted to "the legal subordination of one sex to the other—

Mill's view of history was that right up until his time "the whole of the female" and "the great majority of the male sex" were simply "slaves". He countered arguments to the contrary, arguing that relations between sexes simply amounted to "the legal subordination of one sex to the other—hich

Ij ( fa, ايج, also Romanized as Īj; also known as Hich and Īch) is a village in Golabar Rural District, in the Central District of Ijrud County, Zanjan Province, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also ...

is wrong itself, and now one of the chief hindrances to human improvement; and that it ought to be replaced by a principle of perfect equality." Here, then, we have an instance of Mill's use of "slavery" in a sense which, compared to its fundamental meaning of absolute unfreedom of person, is an extended and arguably a rhetorical rather than a literal sense.

With this, Mill can be considered among the earliest male proponents of gender equality, having been recruited by American feminist John Neal during his stay in London circa 1825–1827. His book ''The Subjection of Women

''The Subjection of Women'' is an essay by English philosopher, political economist and civil servant John Stuart Mill published in 1869, with ideas he developed jointly with his wife Harriet Taylor Mill. Mill submitted the finished manuscript ...

'' (1861, publ.1869) is one of the earliest written on this subject by a male author. In ''The Subjection of Women'', Mill attempts to make a case for perfect equality.

In his proposal for a universal education system sponsored by the state, Mill expands benefits for many marginalized groups, especially for women. For Mill, a universal education held the potential to create new abilities and novel types of behavior of which the current receiving generation and their descendants could both benefit from. Such a pathway to opportunity would enable women to gain "industrial and social independence" that would allow them the same movement in their agency and citizenship as men.

Mill's view of opportunity stands out in its reach, but even more so for the population he foresees who could benefit from it. Mill was hopeful of the autonomy such an education could allow for its recipients and especially for women. Through the consequential sophistication and knowledge attained, individuals are able to properly act in ways that recedes away from those leading towards overpopulation.

This stands directly in contrast with the view held by many of Mill's contemporaries and predecessors who viewed such inclusive programs to be counter intuitive. Aiming such help at marginalized groups, such as the poor and working class, would only serve to reward them with the opportunity to move to a higher status, thus encouraging greater fertility which at its extreme could lead to overproduction.

He talks about the role of women in marriage and how it must be changed. Mill comments on three major facets of women's lives that he felt are hindering them:

# society and gender construction;

# education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty. Var ...

; and

# marriage

Marriage, also called matrimony or wedlock, is a culturally and often legally recognized union between people called spouses. It establishes rights and obligations between them, as well as between them and their children, and between ...

.

He argues that the oppression of women was one of the few remaining relics from ancient times, a set of prejudices that severely impeded the progress of humanity. As a Member of Parliament, Mill introduced an unsuccessful amendment to the Reform Bill

In the United Kingdom, Reform Act is most commonly used for legislation passed in the 19th century and early 20th century to enfranchise new groups of voters and to redistribute seats in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. ...

to substitute the word "person" in place of "man

A man is an adult male human. Prior to adulthood, a male human is referred to as a boy (a male child or adolescent). Like most other male mammals, a man's genome usually inherits an X chromosome from the mother and a Y chromo ...

".

''Utilitarianism''

The canonical statement of Mill's

The canonical statement of Mill's utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charact ...

can be found in his book, ''Utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charact ...

''. Although this philosophy has a long tradition, Mill's account is primarily influenced by Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

and Mill's father James Mill

James Mill (born James Milne; 6 April 1773 – 23 June 1836) was a Scottish historian, economist, political theorist, and philosopher. He is counted among the founders of the Ricardian school of economics. He also wrote '' The History of Britis ...

.