Foibe massacres on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The foibe massacres (; ; ), or simply the foibe, refers to mass killings both during and after

At the Plutone foibe near Bazovizza, members of the Trieste Steffe criminal gang killed 18 people. For this the leader of the gang, Giovanni Steffe, and three others were arrested by the Yugoslav forces. Steffe and Carlo Mazzoni were killed by the Yugoslav forces while trying to escape. Three members of the gang, all from Trieste, were later convicted by Italian courts to 2 to 5 years in jail for the killings. Altogether some 70 trials were held in Italy from 1946 to 1949 for the killings, some ending in acquittals or amnesties, others with heavy sentences.

In 1947, British envoy W. J. Sullivan wrote of Italians arrested and deported by Yugoslav forces from around Trieste: Alongside a large number of Fascists, however, among those killed were also anti-Fascists who opposed the Yugoslav annexation of the region, such as

At the Plutone foibe near Bazovizza, members of the Trieste Steffe criminal gang killed 18 people. For this the leader of the gang, Giovanni Steffe, and three others were arrested by the Yugoslav forces. Steffe and Carlo Mazzoni were killed by the Yugoslav forces while trying to escape. Three members of the gang, all from Trieste, were later convicted by Italian courts to 2 to 5 years in jail for the killings. Altogether some 70 trials were held in Italy from 1946 to 1949 for the killings, some ending in acquittals or amnesties, others with heavy sentences.

In 1947, British envoy W. J. Sullivan wrote of Italians arrested and deported by Yugoslav forces from around Trieste: Alongside a large number of Fascists, however, among those killed were also anti-Fascists who opposed the Yugoslav annexation of the region, such as  The foibe massacres were

The foibe massacres were

The number of those killed or left in ''foibe'' during and after the war is still unknown; it is difficult to establish and a matter of controversy. Estimates range from hundreds to twenty thousand. According to data gathered by a joint Slovene-Italian historical commission established in 1993, "the violence was further manifested in hundreds of

The number of those killed or left in ''foibe'' during and after the war is still unknown; it is difficult to establish and a matter of controversy. Estimates range from hundreds to twenty thousand. According to data gathered by a joint Slovene-Italian historical commission established in 1993, "the violence was further manifested in hundreds of

/ref>Foibe, bilancio e rilettura

nonluoghi.info, February 2015; accessed 17 March 2016. More bodies were sighted, but not recovered. The most famous Basovizza foiba, was investigated by English and American forces, starting immediately on June 12, 1945. After 5 months of investigation and digging, all they found in the foiba were the remains of 150 German soldiers and one civilian killed in the final battles for Basovizza on April 29–30, 1945. The Italian mayor, Gianni Bartoli continued with investigations and digging until 1954, with speleologists entering the cave multiple time, yet they found nothing. Between November 1945 and April 1948, firefighters, speleologists and policemen inspected ''foibe'' and mine shafts in the "Zone A" of the

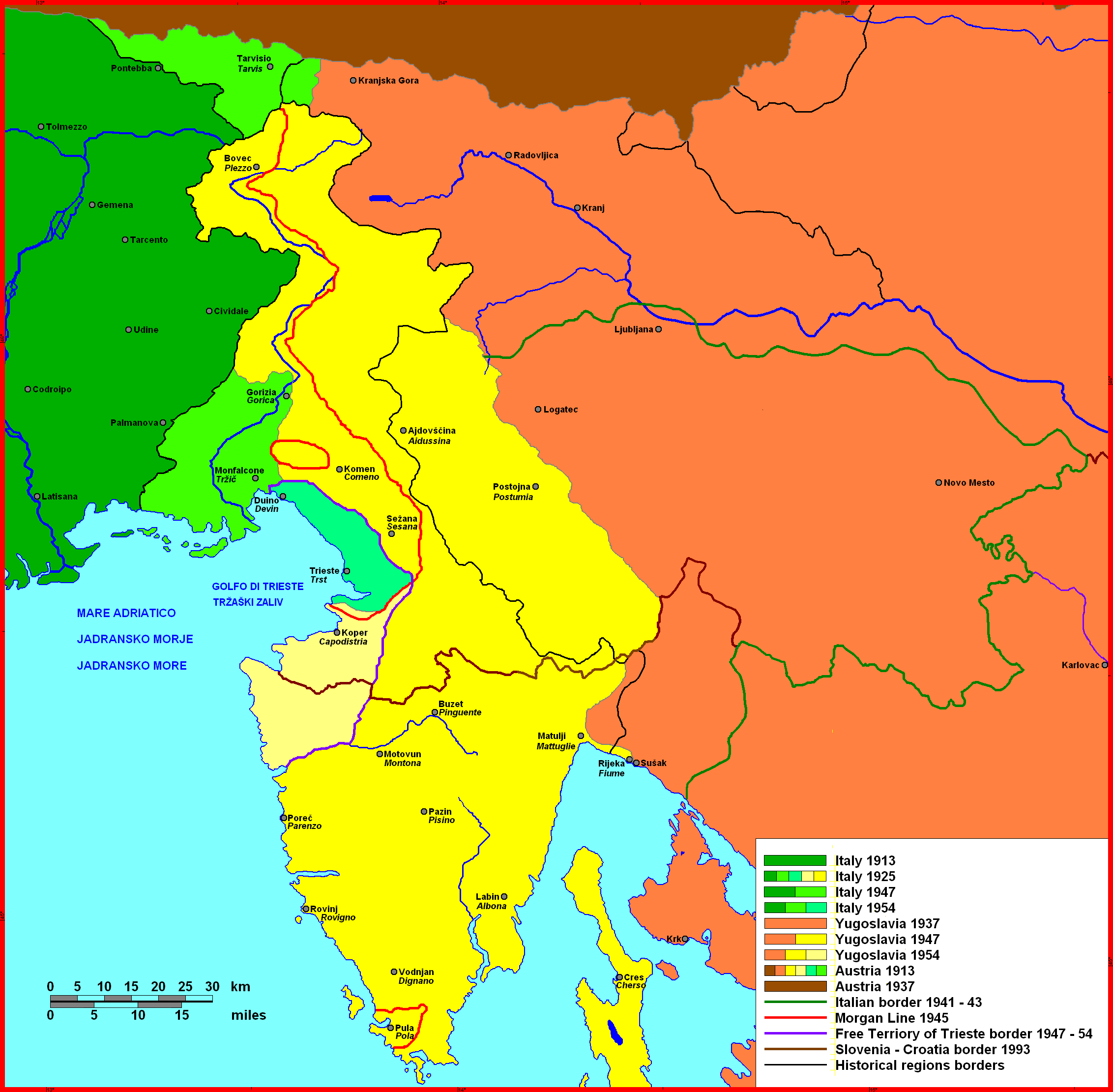

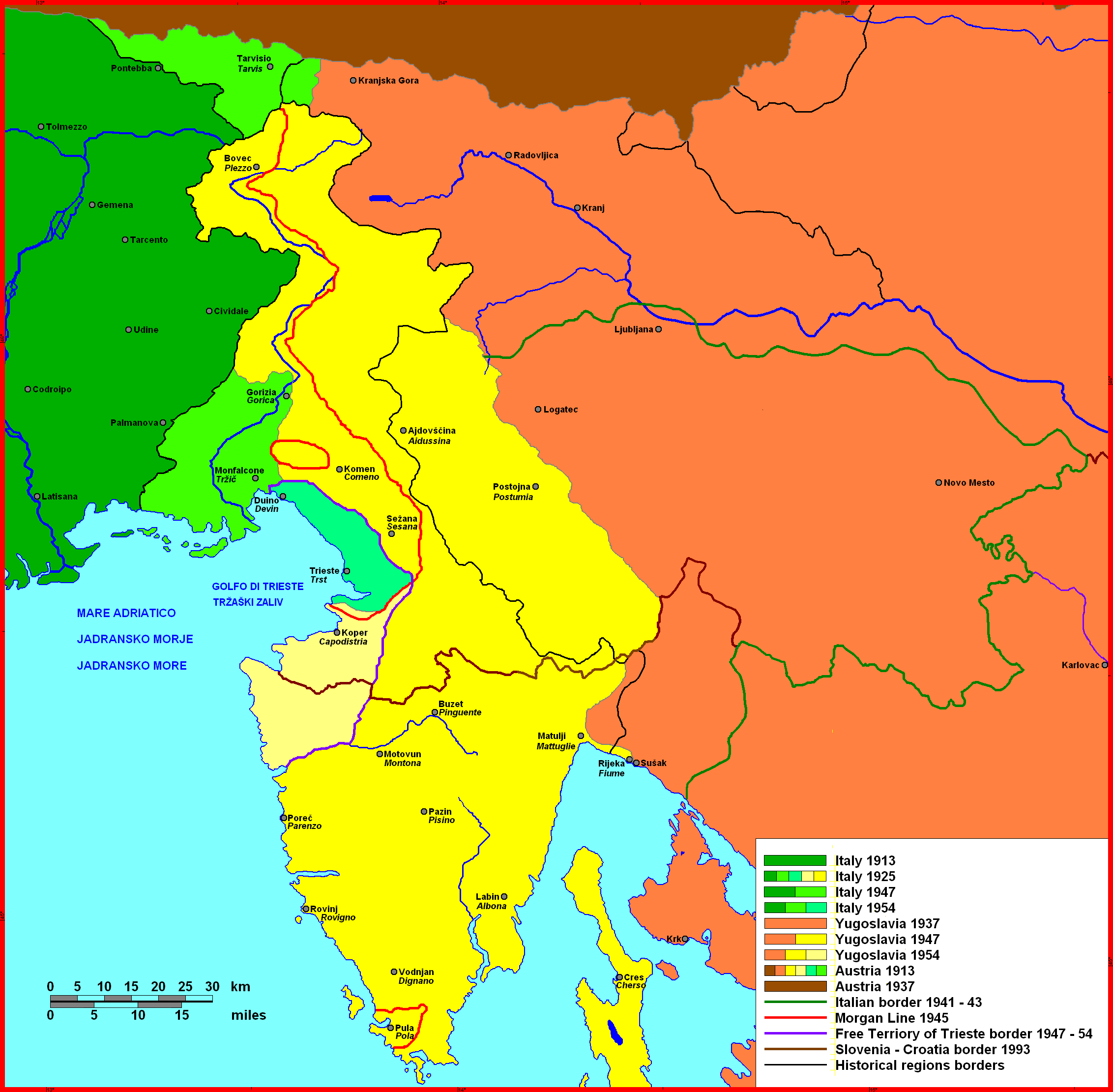

The coastal areas and cities of Istria came under Venetian Influence in the 9th century. In 1145, the cities of

The coastal areas and cities of Istria came under Venetian Influence in the 9th century. In 1145, the cities of

During the meeting of the Council of Ministers of 12 November 1866, Emperor

During the meeting of the Council of Ministers of 12 November 1866, Emperor

In a 1920 speech in

In a 1920 speech in

Seeking to create an Imperial Italy, Mussolini started expansionist wars in the Mediterranean, with Fascist Italy invading and occupying

Seeking to create an Imperial Italy, Mussolini started expansionist wars in the Mediterranean, with Fascist Italy invading and occupying

(Archived by

''«Si ammazza troppo poco». I crimini di guerra italiani. 1940–43''

Mondadori, In 1944, near the end of a war in which Nazis, Fascists and their allies killed over 800,000 Yugoslavs, Croat poet

After the war, inspector Umberto de Giorgi, who was State Police marshal under fascist and Nazi rule, led the Foibe Exploration Team. Between 1945 and 1948 they investigated 71 foibe locations on the Italian side of the border. 23 of these were empty, in the rest they discovered some 464 corpses. These included soldiers killed during the last battles of the war. Among the 246 identified corpses, more than 200 were military (German, Italian, other), and some 40 were civilians, of the latter, 30 killed after the war.

Due to claims of hundreds having been killed and tossed into the Basovizza mineshaft, in August–October, 1945 British military authorities investigated the shaft, ultimately recovering 9 German soldiers, 1 civilian and a few horse cadavers. Based on these results the British suspended excavations. Afterwards the city of Trieste used the mineshaft as a garbage dump. Despite repeat demands from various right-wing groups to further excavate the shaft, the government of Trieste, led by the Christian Democratic mayor Gianni Bartoli, declined to do so, claiming among other reasons, lack of financial resources. In 1959 the shaft was sealed and a monument erected, thus becoming the center of the annual foibe commemorations.

Only a few trials were held, including that of the Trieste Zoll-Steffe criminal gang, for the killing of 18 people in the Plutone foibe in May 1945. Afterwards, Yugoslav authorities arrested the gang members and took them to Ljubljana, with two killed along the way while trying to escape, and the others convicted before a military tribunal. Additional members of the gang were brought before an Italian court in Trieste 1947, and were convicted and sentenced to prison for 2–3 years for their role in the Plutone killings.

After the war, inspector Umberto de Giorgi, who was State Police marshal under fascist and Nazi rule, led the Foibe Exploration Team. Between 1945 and 1948 they investigated 71 foibe locations on the Italian side of the border. 23 of these were empty, in the rest they discovered some 464 corpses. These included soldiers killed during the last battles of the war. Among the 246 identified corpses, more than 200 were military (German, Italian, other), and some 40 were civilians, of the latter, 30 killed after the war.

Due to claims of hundreds having been killed and tossed into the Basovizza mineshaft, in August–October, 1945 British military authorities investigated the shaft, ultimately recovering 9 German soldiers, 1 civilian and a few horse cadavers. Based on these results the British suspended excavations. Afterwards the city of Trieste used the mineshaft as a garbage dump. Despite repeat demands from various right-wing groups to further excavate the shaft, the government of Trieste, led by the Christian Democratic mayor Gianni Bartoli, declined to do so, claiming among other reasons, lack of financial resources. In 1959 the shaft was sealed and a monument erected, thus becoming the center of the annual foibe commemorations.

Only a few trials were held, including that of the Trieste Zoll-Steffe criminal gang, for the killing of 18 people in the Plutone foibe in May 1945. Afterwards, Yugoslav authorities arrested the gang members and took them to Ljubljana, with two killed along the way while trying to escape, and the others convicted before a military tribunal. Additional members of the gang were brought before an Italian court in Trieste 1947, and were convicted and sentenced to prison for 2–3 years for their role in the Plutone killings.

In 1949 a trial was held in Trieste for those accused of killing Mario Fabian, a torturer in the "Collotti gang", a fascist squad that during the war killed and tortured Slovene and Italian antifascists, and Jews. Fabian was taken from his home on May 4, 1945, then shot and tossed into the Basovizza shaft. He is the only known Italian victim of Basovizza. His executioners were at first condemned, but later acquitted. The historian Pirjevec notes that the head of the gang, Gaetano Collotti, was awarded a medal by the Italian government in 1954, for fighting Slovene partisans in 1943, despite the fact that Collotti and his gang had committed many crimes while working for the Gestapo, and was killed by Italian partisans near Treviso in 1945.

In 1993 a study titled ''Pola Istria Fiume 1943-1945'' by Gaetano La Perna provided a detailed list of the victims of Yugoslav occupation (in September–October 1943 and from 1944 to the very end of the Italian presence in its former provinces) in the area. La Perna gave a list of 6,335 names (2,493 military, 3,842 civilians). The author considered this list "not complete".

A 2002 joint report by

In 1949 a trial was held in Trieste for those accused of killing Mario Fabian, a torturer in the "Collotti gang", a fascist squad that during the war killed and tortured Slovene and Italian antifascists, and Jews. Fabian was taken from his home on May 4, 1945, then shot and tossed into the Basovizza shaft. He is the only known Italian victim of Basovizza. His executioners were at first condemned, but later acquitted. The historian Pirjevec notes that the head of the gang, Gaetano Collotti, was awarded a medal by the Italian government in 1954, for fighting Slovene partisans in 1943, despite the fact that Collotti and his gang had committed many crimes while working for the Gestapo, and was killed by Italian partisans near Treviso in 1945.

In 1993 a study titled ''Pola Istria Fiume 1943-1945'' by Gaetano La Perna provided a detailed list of the victims of Yugoslav occupation (in September–October 1943 and from 1944 to the very end of the Italian presence in its former provinces) in the area. La Perna gave a list of 6,335 names (2,493 military, 3,842 civilians). The author considered this list "not complete".

A 2002 joint report by

It has been alleged that the killings were part of a

It has been alleged that the killings were part of a

For several Italian historians these killings were the beginning of organized

For several Italian historians these killings were the beginning of organized  Medal of ''Day of Remembrance'' to relatives of victims of foibe killings

In February 2012, a photo of Italian troops killing Slovene civilians was shown on public Italian TV as if being the other way round. When historian

Medal of ''Day of Remembrance'' to relatives of victims of foibe killings

In February 2012, a photo of Italian troops killing Slovene civilians was shown on public Italian TV as if being the other way round. When historian Il giorno del ricordo - Porta a Porta, from Rai website

accessed 26 September 2015.

available online

* Vincenzo Maria De Luca, ''Foibe. Una tragedia annunciata. Il lungo addio italiano alla Venezia Giulia'', Settimo sigillo, Roma, 2000. * Luigi Papo, ''L'Istria e le sue foibe'', Settimo sigillo, Roma, 1999. * Luigi Papo, ''L'ultima bandiera''. * Marco Pirina, ''Dalle foibe all'esodo 1943-1956''. * Franco Razzi, ''Lager e foibe in Slovenia''. * Giorgio Rustia, ''Contro operazione foibe a Trieste'', 2000. * Carlo Sgorlon, ''La foiba grande'', Mondadori, 2005, . * Pol Vice, ''La foiba dei miracoli'', Kappa Vu, Udine, 2008. * Atti del convegno di Sesto San Giovanni 2008, "Foibe. Revisionismo di Stato e amnesie della Repubblica", Kappa Vu, Udine, 2008. * Gaetano La Perna, ''Pola Istria Fiume 1943-1945'', Mursia, Milan, 1993. * Marco Girardo ''Sopravvissuti e dimenticati: il dramma delle foibe e l'esodo dei giuliano-dalmati'

Paoline, 2006

* Amleto Ballerini, Mihael Sobolevski, ''Le vittime di nazionalità italiana a Fiume e dintorni (1939–1947) - Žrtve talijanske nacionalnosti u Rijeci i okolici (1939.-1947.)'', Società Di Studi Fiumani - Hrvatski Institut Za Povijest, Roma Zagreb, Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali Direzione generale per gli archivi, Pubblicazioni degli Archivi Di Stato, Sussidi 12, . :: An Italian-Croatian joint research carried out by the Italian "Society of Fiuman studies" and the "Croatian Institute of History", containing an alphabetic list of recognized victims. As foot note, on each of the two lingual forewords, a warning states that ''Società di Studi Fiumani'' do not judge completed the present work, because the lack of funds, could not achieve to the finalization that was in intentions and goals of the initial project.

princeton.edu; accessed 14 December 2015.

nytimes.com, 20 April 1997. Report of the Italian-Slovene commission of historians (in three languages):

Operazione foibe a Trieste by Claudia Cernigoi

Le foibe

* Gian Luigi Falabrino

* Marco Ottanelli

* Istituto regionale per la storia della Resistenza e dell’Età contemporanea nel Friuli Venezia Giulia

"Vademecum per il giorno del ricordo"

;Videos

1948 Italian newsreel

{{DEFAULTSORT:Foibe Massacres Massacres in 1943 Massacres in 1945 Massacres in Italy Massacres in Yugoslavia Yugoslav war crimes Deaths by firearm in Italy Deaths by firearm in Yugoslavia World War II massacres Ethnic cleansing in Europe Yugoslavia in World War II 1943 in Yugoslavia 1945 in Yugoslavia Italians of Croatia Political and cultural purges Political repression in Communist Yugoslavia Politicides Anti-Italian sentiment Aftermath of World War II in Yugoslavia Mass murder in 1943 1943 murders in Europe Mass murder in 1945 1945 murders in Europe Massacres of Croats

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, mainly committed by Yugoslav Partisans

The Yugoslav Partisans,Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian, Slovene: , or the National Liberation Army, sh-Latn-Cyrl, Narodnooslobodilačka vojska (NOV), Народноослободилачка војска (НОВ); mk, Народноослобод� ...

and OZNA

The Department for People's Protection or OZNA ( sh-Cyrl-Latn, Одељење за заштиту нaрода, Odjeljenje za zaštitu naroda, Odeljenje za zaštitu naroda; mk, Одделение за заштита на народот; sl, Oddele ...

in the then-Italian territories of Julian March

Venezia Giulia, traditionally called Julian March (Serbo-Croatian, Slovene: ''Julijska krajina'') or Julian Venetia ( it, Venezia Giulia; vec, Venesia Julia; fur, Vignesie Julie; german: Julisch Venetien) is an area of southeastern Europe wh ...

( Karst Region and Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian and Slovene: ; ist, Eîstria; Istro-Romanian, Italian and Venetian: ; formerly in Latin and in Ancient Greek) is the largest peninsula within the Adriatic Sea. The peninsula is located at the head of the Adriatic betwe ...

), Kvarner

The Kvarner Gulf (, or , la, Sinus Flanaticus or ), sometimes also Kvarner Bay, is a bay in the northern Adriatic Sea, located between the Istrian peninsula and the northern Croatian Littoral mainland. The bay is a part of Croatia's internal ...

and Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

, against the local ethnic Italian population (Istrian Italians

Istrian Italians are an ethnic group from the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic region of Istria in modern northwestern Croatia and southwestern Slovenia. Istrian Italians descend from the original Latinized population of Roman Empire, Roman Istria#Early h ...

and Dalmatian Italians

Dalmatian Italians are the historical Italian national minority living in the region of Dalmatia, now part of Croatia and Montenegro. Since the middle of the 19th century, the community, counting according to some sources nearly 20% of all Da ...

), as well the ethnic Slovenes

The Slovenes, also known as Slovenians ( sl, Slovenci ), are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Slovenia, and adjacent regions in Italy, Austria and Hungary. Slovenes share a common ancestry, Slovenian culture, culture, History ...

, Croats

The Croats (; hr, Hrvati ) are a South Slavic ethnic group who share a common Croatian ancestry, culture, history and language. They are also a recognized minority in a number of neighboring countries, namely Austria, the Czech Republic ...

and Istro-Romanians who chose to maintain Italian citizenship, against all anti-communists, associated with Fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and t ...

, Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) i ...

and collaboration with Axis, and against real, potential or presumed opponents of Tito communism. The type of attack was state terrorism

State terrorism refers to acts of terrorism which a state conducts against another state or against its own citizens.Martin, 2006: p. 111.

Definition

There is neither an academic nor an international legal consensus regarding the proper def ...

, reprisal killings, and ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

against Italians

, flag =

, flag_caption = The national flag of Italy

, population =

, regions = Italy 55,551,000

, region1 = Brazil

, pop1 = 25–33 million

, ref1 =

, region2 ...

.

The Yugoslav partisans intended to kill whoever could oppose or compromise the future annexation of Italian territories: as a preventive purge of real, potential or presumed opponents of Tito communism (Italian, Slovenian and Croatian anti-communists, collaborators and radical nationalists), the Yugoslav partisans exterminated the native anti-fascist

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers wer ...

autonomists — including the leadership of Italian anti-fascist partisan organizations and the leaders of Fiume's Autonomist Party, like Mario Blasich and Nevio Skull, who supported local independence from both Italy and Yugoslavia — for example in the city of Fiume, where at least 650 were killed after the entry of the Yugoslav units, without any due trial.

The term refers to the victims who were often thrown alive into '' foibe'' (from Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

: ), or into deep natural sinkhole

A sinkhole is a depression or hole in the ground caused by some form of collapse of the surface layer. The term is sometimes used to refer to doline, enclosed depressions that are locally also known as ''vrtače'' and shakeholes, and to openi ...

s characteristic of the karst regions (by extension, it also was applied to the use of mine shafts, etc., to hide the bodies). In a wider or symbolic sense, some authors used the term to apply to all disappearances or killings of Italian people in the territories occupied by Yugoslav forces. They excluded possible 'foibe' killings by other parties or forces. Others included deaths resulting from the forced deportation of Italians, or those who died while trying to flee from these contested lands.

The foibe massacres were followed by the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus

The Istrian–Dalmatian exodus (; ; ) was the post- World War II exodus and departure of local ethnic Italians ( Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians) as well as ethnic Slovenes, Croats, and Istro-Romanians from the Yugoslav territory of ...

, which was the post-World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

exodus and departure of local ethnic Italians (Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians) from the Yugoslav territory of Istria, Kvarner, the Julian March, lost by Italy after the Treaty of Paris (1947), as well as Dalmatia, towards Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, and in smaller numbers, towards the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America, North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World. ...

and Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

. According to various sources, the exodus is estimated to have amounted to between 230,000 and 350,000 Italians (the others being ethnic Slovenes

The Slovenes, also known as Slovenians ( sl, Slovenci ), are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Slovenia, and adjacent regions in Italy, Austria and Hungary. Slovenes share a common ancestry, Slovenian culture, culture, History ...

, Croats

The Croats (; hr, Hrvati ) are a South Slavic ethnic group who share a common Croatian ancestry, culture, history and language. They are also a recognized minority in a number of neighboring countries, namely Austria, the Czech Republic ...

, and Istro-Romanians, who chose to maintain Italian citizenship) leaving the areas in the aftermath of the conflict.

The estimated number of people killed in the foibe is disputed, varying from hundreds to thousands, according to some sources 11,000 or 20,000. The Italian historian, Raoul Pupo estimates 3,000 to 4,000 total victims, across all areas of former Yugoslavia and Italy from 1943 to 1945, with the primary target being military and repressive forces of the Fascist regime, and civilians associated with the regime, including Slavic collaborators. He places the events in the broader context of "the collapse of a structure of power and oppression: that of the fascist state in 1943, that of the Nazi-fascist state of the Adriatic coast in 1945."

The events were also part of larger reprisals in which tens-of-thousands of Slavic collaborators of Axis forces were killed in the aftermath of WWII, following a brutal war in which some 800,000 Yugoslavs, the vast majority civilians, were killed by Axis occupation forces and collaborators, with Italian forces committing war crimes. Similar postwar reprisals occurred in other countries, including Italy, where the Italian resistance

The Italian resistance movement (the ''Resistenza italiana'' and ''la Resistenza'') is an umbrella term for the Italian resistance groups who fought the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and the fascist collaborationists of the Italian Socia ...

and others killed an estimated 12,000 to 26,000 Italians, usually in extra-judicial executions, the great majority in Northern Italy, just in April and May 1945.

Origin and meaning of the term

The name was derived from a local geological feature, a type of deepkarst

Karst is a topography formed from the dissolution of soluble rocks such as limestone, Dolomite (rock), dolomite, and gypsum. It is characterized by underground drainage systems with sinkholes and caves. It has also been documented for more weathe ...

sinkhole

A sinkhole is a depression or hole in the ground caused by some form of collapse of the surface layer. The term is sometimes used to refer to doline, enclosed depressions that are locally also known as ''vrtače'' and shakeholes, and to openi ...

called ''foiba

A foiba (from Italian: ; plural: foibe or foibas) — ''jama'' () in South Slavic languages scientific and colloquial vocabulary (borrowed since early research in the Western Balkan Dinaric Alpine karst) — is a type of deep natural sinkhole ...

''. The term includes by extension killings and "burials" in other subterranean formations, such as the Basovizza "''foiba''", which is a mine shaft.

In Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

the term ''foibe'' has, for some authors and scholars, taken on a symbolic meaning; for them it refers in a broader sense to all the disappearances or killings of Italian people in the territories occupied by Yugoslav forces. According to author :

It is well known that the majority of the victims didn't end their lives in a Karst cave, but met their deaths on the road to deportation, as well as in jails or in Yugoslav concentration camps.Pupo also states that — since the primary targets of the purges were ideological, i.e. the anti-communists — the Yugoslav troops did not behave like an occupying army, partly contradicting the numerous academic authors and institutional figures — both in Italy and abroad — who recognized an

ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

against Italians

, flag =

, flag_caption = The national flag of Italy

, population =

, regions = Italy 55,551,000

, region1 = Brazil

, pop1 = 25–33 million

, ref1 =

, region2 ...

, and against ethnic Slovenes

The Slovenes, also known as Slovenians ( sl, Slovenci ), are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Slovenia, and adjacent regions in Italy, Austria and Hungary. Slovenes share a common ancestry, Slovenian culture, culture, History ...

, Croats

The Croats (; hr, Hrvati ) are a South Slavic ethnic group who share a common Croatian ancestry, culture, history and language. They are also a recognized minority in a number of neighboring countries, namely Austria, the Czech Republic ...

and Istro-Romanians who chose to maintain Italian citizenship.

The terror spread by these disappearances and killings eventually caused the majority of the Italians of Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian and Slovene: ; ist, Eîstria; Istro-Romanian, Italian and Venetian: ; formerly in Latin and in Ancient Greek) is the largest peninsula within the Adriatic Sea. The peninsula is located at the head of the Adriatic betwe ...

, Fiume

Rijeka ( , , ; also known as Fiume hu, Fiume, it, Fiume ; local Chakavian: ''Reka''; german: Sankt Veit am Flaum; sl, Reka) is the principal seaport and the third-largest city in Croatia (after Zagreb and Split). It is located in Prim ...

, and Zara to flee to other parts of Italy or the Free Territory of Trieste

The Free Territory of Trieste was an independent territory in Southern Europe between northern Italy and Yugoslavia, facing the north part of the Adriatic Sea, under direct responsibility of the United Nations Security Council in the aftermath ...

. Raoul Pupo wrote:

According to Fogar and Miccoli there is the need to put the episodes in 1943 and 1945 within he context ofa longer history of abuse and violence, which began with Fascism and with its policy of oppression of the minority Slovenes and Croats and continued with the Italian aggression on Yugoslavia, which culminated with the horrors of the Nazi-Fascist repression against the Partisan movement.Other authors assert that the post-war pursuit of the 'truth' of the ''foibe,'' as a means of transcending Fascist/Anti-Fascist oppositions and promoting popular patriotism, has not been the preserve of right-wing or

neo-Fascist

Neo-fascism is a post-World War II far-right ideology that includes significant elements of fascism. Neo-fascism usually includes ultranationalism, racial supremacy, populism, authoritarianism, nativism, xenophobia, and anti-immigration ...

groups. Evocations of the 'Slav other' and of the terrors of the ''foibe'' made by state institutions, academics, amateur historians, journalists, and the memorial landscape of everyday life were the backdrop to the post-war renegotiation of Italian national identity.

Gaia Baracetti notes that Italian representations of ''foibe,'' such as a miniseries on national television, are replete with historical inaccuracies and stereotypes, portraying Slavs as “merciless assassins”, similar to fascist propaganda, while “largely ignoring the issue of Italian war crimes

Italian war crimes have mainly been associated with Fascist Italy in the Pacification of Libya, the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, the Spanish Civil War, and World War II.

Italo-Turkish War

In 1911, Italy went to war with the Ottoman Empire and in ...

” Others, including members of Italy's Jewish community, have objected to Italian right-wing efforts to equate the ''foibe'' with the Holocaust, via historical distortions which include exaggerated ''foibe'' victim claims, in an attempt to turn Italy from a perpetrator in the Holocaust, to a victim.

Events

The first (disputed) claims of people being thrown into ''foibe'' date to 1943, after theWehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

took back the area from the Partisans. Other authors claimed the 70 hostages were killed and burned in the Nazi ''lager'' of the Risiera of San Sabba, on 4 April 1944.

The massacres occurred in two waves, the first taking places in the interlude between the Armistice of Cassibile

The Armistice of Cassibile was an armistice signed on 3 September 1943 and made public on 8 September between the Kingdom of Italy and the Allies during World War II.

It was signed by Major General Walter Bedell Smith for the Allies and Bri ...

and the German occupation of Istria in September 1943, and the second after the Yugoslav occupation of the region in May 1945. Victims of the first wave numbered in the hundreds, whereas those of the second wave in the thousands. The first wave of killings is widely regarded as a disorganized, spontaneous series of revenge killing

Revenge is committing a harmful action against a person or group in response to a grievance, be it real or perceived. Francis Bacon described revenge as a kind of "wild justice" that "does... offend the law ndputteth the law out of office." P ...

s by Slovenes and Croats after twenty years of Fascist oppression, as well as "''jacquerie

The Jacquerie () was a popular revolt by peasants that took place in northern France in the early summer of 1358 during the Hundred Years' War. The revolt was centred in the valley of the Oise north of Paris and was suppressed after a few week ...

''" against Italian landowners and more broadly the Italian elite in the region; these killings targeted members of the Fascist Party, their relatives (as in the famous case of Norma Cossetto), Italian landowners, policemen and civil servant

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil servants hired on professional merit rather than appointed or elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leaders ...

s of all ranks, considered as symbols of Italian oppression. The scope and nature of the second wave is much more disputed; Slovene and Croat historians, as well as Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

-leaning Italian historians such as Alessandra Kersevan

Alessandra Kersevan (born 18 December 1950) is a historian, author and editor living and working in Udine.

She researches Italian modern history, including the Italian resistance movement and Italian war crimes.

She is the editor of a group cal ...

and Claudia Cernigoi, characterize it as another wave of revenge killings against Fascist collaborators and members of the armed forces of the Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic ( it, Repubblica Sociale Italiana, ; RSI), known as the National Republican State of Italy ( it, Stato Nazionale Repubblicano d'Italia, SNRI) prior to December 1943 but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò ...

, whereas Italian historians such as Raoul Pupo, Gianni Oliva and Roberto Spazzali argue that this was the result of a deliberate Titoist policy aimed at spreading terror among the Italian population of the region and eliminating anyone who opposed Yugoslav plans of annexing Istria and the Julian March, including anti-Fascists. It is to be noted that while the ''foibe'' became the symbol of these massacres, only a minority of the victims were killed with this method, largely during the first wave; a far larger part were executed and buried in mass grave

A mass grave is a grave containing multiple human corpses, which may or may not be identified prior to burial. The United Nations has defined a criminal mass grave as a burial site containing three or more victims of execution, although an exact ...

s or died in Yugoslav prisons and concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

s.

After the re-occupation of Istria by Axis forces in September 1943, following the first wave of killings, the fire brigade

A fire department (American English) or fire brigade (Commonwealth English), also known as a fire authority, fire district, fire and rescue, or fire service in some areas, is an organization that provides fire prevention and fire suppression se ...

of Pola, under the command of Arnaldo Harzarich, recovered 204 bodies from the foibe of the region. Between 1945 and 1948, Italian authorities recovered a total 369 corpses from foibe in the Italian-controlled part of the Free Territory of Trieste (Zone A), and another 95 were recovered from mass graves in the same area; these included also bodies of German soldiers killed in the closing days of the war and hastily buried in these cavities. Foibe located in the Yugoslav-controlled part of the Free Territory of Trieste, as well as in the rest of Istria, were never searched as this territory was now under Yugolav control.

Great controversy has surrounded the ''foiba'' of Basovizza, one of the most famous ''foibe'' (and unlikely called as such, as it was not a natural ''foiba'' but a disused mine shaft

Shaft mining or shaft sinking is the action of excavating a mine shaft from the top down, where there is initially no access to the bottom. Shallow shafts, typically sunk for civil engineering projects, differ greatly in execution method from ...

). Newspaper reports from the postwar era claimed anywhere from 18 to 3,000 victims in this ''foiba'' alone, but Trieste authorities refused to fully excavate it, citing financial constraints. At the end of the war, local villagers had thrown the bodies of dead German soldiers (killed in a battle fought in the vicinity in the closing days of the war) and horses into the mine shaft, which after the war had also been used as a garbage dump by the authorities of the Free Territory of Trieste

The Free Territory of Trieste was an independent territory in Southern Europe between northern Italy and Yugoslavia, facing the north part of the Adriatic Sea, under direct responsibility of the United Nations Security Council in the aftermath ...

. After the war the Basovizza foibe was used by the Italian authorities as a garbage dump. Thus no Italian victims were ever recovered or determined at Basovizza. In 1959 the pit was sealed and a monument erected, which later became the central site for the annual foibe commemorations.

At the Plutone foibe near Bazovizza, members of the Trieste Steffe criminal gang killed 18 people. For this the leader of the gang, Giovanni Steffe, and three others were arrested by the Yugoslav forces. Steffe and Carlo Mazzoni were killed by the Yugoslav forces while trying to escape. Three members of the gang, all from Trieste, were later convicted by Italian courts to 2 to 5 years in jail for the killings. Altogether some 70 trials were held in Italy from 1946 to 1949 for the killings, some ending in acquittals or amnesties, others with heavy sentences.

In 1947, British envoy W. J. Sullivan wrote of Italians arrested and deported by Yugoslav forces from around Trieste: Alongside a large number of Fascists, however, among those killed were also anti-Fascists who opposed the Yugoslav annexation of the region, such as

At the Plutone foibe near Bazovizza, members of the Trieste Steffe criminal gang killed 18 people. For this the leader of the gang, Giovanni Steffe, and three others were arrested by the Yugoslav forces. Steffe and Carlo Mazzoni were killed by the Yugoslav forces while trying to escape. Three members of the gang, all from Trieste, were later convicted by Italian courts to 2 to 5 years in jail for the killings. Altogether some 70 trials were held in Italy from 1946 to 1949 for the killings, some ending in acquittals or amnesties, others with heavy sentences.

In 1947, British envoy W. J. Sullivan wrote of Italians arrested and deported by Yugoslav forces from around Trieste: Alongside a large number of Fascists, however, among those killed were also anti-Fascists who opposed the Yugoslav annexation of the region, such as Socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

Licurgo Olivi and Action Party leader Augusto Sverzutti, members of the Committee of National Liberation of Gorizia; in Trieste, the same fate befell Resistance leaders Romano Meneghello (posthumously awarded a Silver Medal of Military Valor

The Silver Medal of Military Valor ( it, Medaglia d'argento al valor militare) is an Italian medal for gallantry.

Italian medals for valor were first instituted by Victor Amadeus III of Sardinia on 21 May 1793, with a gold medal, and, below it, ...

for his Resistance activities) and Carlo Dell'Antonio. In Fiume

Rijeka ( , , ; also known as Fiume hu, Fiume, it, Fiume ; local Chakavian: ''Reka''; german: Sankt Veit am Flaum; sl, Reka) is the principal seaport and the third-largest city in Croatia (after Zagreb and Split). It is located in Prim ...

(where at least 652 Italians were killed or disappeared between 3 May 1945 and 31 December 1947, according to a joint Italian-Croat study), Autonomist Party

The Autonomist Party ( it, Partito Autonomista; hr, Autonomaška stranka) was an Italian-Dalmatianist political party in the Dalmatian political scene, that existed for around 70 years of the 19th century and until World War I. Its goal was ...

leaders Mario Blasich, Joseph Sincich and Nevio Skull were among those executed by the Yugoslavs soon after the occupation, as was anti-Fascist and Dachau

Dachau () was the first concentration camp built by Nazi Germany, opening on 22 March 1933. The camp was initially intended to intern Hitler's political opponents which consisted of: communists, social democrats, and other dissidents. It is lo ...

survivor Angelo Adam. Priests were also targeted by the new Yugoslav Communist authorities, as in the case of Francesco Bonifacio. Out of 1,048 people who were arrested and executed by the Yugoslavs in the province of Gorizia

The Province of Gorizia ( it, Provincia di Gorizia, fur, Provincie di Gurize; sl, Goriška pokrajina) was a province in the autonomous Friuli–Venezia Giulia region of Italy, which was disbanded on 30 September 2017.

Overview

Its capital was th ...

in May 1945, according to a list drafted by a joint Italian-Slovene commission in 2006, 470 were members of the military or police forces of the Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic ( it, Repubblica Sociale Italiana, ; RSI), known as the National Republican State of Italy ( it, Stato Nazionale Repubblicano d'Italia, SNRI) prior to December 1943 but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò ...

, 110 were Slovene civilians accused of collaborationism

Wartime collaboration is cooperation with the enemy against one's country of citizenship in wartime, and in the words of historian Gerhard Hirschfeld, "is as old as war and the occupation of foreign territory".

The term ''collaborator'' dates to ...

, and 320 were Italian civilians.

The foibe massacres were

The foibe massacres were state terrorism

State terrorism refers to acts of terrorism which a state conducts against another state or against its own citizens.Martin, 2006: p. 111.

Definition

There is neither an academic nor an international legal consensus regarding the proper def ...

, reprisal killings, and ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

against Italians

, flag =

, flag_caption = The national flag of Italy

, population =

, regions = Italy 55,551,000

, region1 = Brazil

, pop1 = 25–33 million

, ref1 =

, region2 ...

. The foibe massacres were mainly committed by Yugoslav Partisans

The Yugoslav Partisans,Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian, Slovene: , or the National Liberation Army, sh-Latn-Cyrl, Narodnooslobodilačka vojska (NOV), Народноослободилачка војска (НОВ); mk, Народноослобод� ...

and OZNA

The Department for People's Protection or OZNA ( sh-Cyrl-Latn, Одељење за заштиту нaрода, Odjeljenje za zaštitu naroda, Odeljenje za zaštitu naroda; mk, Одделение за заштита на народот; sl, Oddele ...

against the local ethnic Italian population (Istrian Italians

Istrian Italians are an ethnic group from the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic region of Istria in modern northwestern Croatia and southwestern Slovenia. Istrian Italians descend from the original Latinized population of Roman Empire, Roman Istria#Early h ...

and Dalmatian Italians

Dalmatian Italians are the historical Italian national minority living in the region of Dalmatia, now part of Croatia and Montenegro. Since the middle of the 19th century, the community, counting according to some sources nearly 20% of all Da ...

), as well against anti-communists in general (even Croats

The Croats (; hr, Hrvati ) are a South Slavic ethnic group who share a common Croatian ancestry, culture, history and language. They are also a recognized minority in a number of neighboring countries, namely Austria, the Czech Republic ...

and Slovenes

The Slovenes, also known as Slovenians ( sl, Slovenci ), are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Slovenia, and adjacent regions in Italy, Austria and Hungary. Slovenes share a common ancestry, Slovenian culture, culture, History ...

), usually associated with Fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and t ...

, Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) i ...

and collaboration with Axis, and against real, potential or presumed opponents of Tito communism. The events were also part of larger reprisals in which tens-of-thousands of Slavic collaborators of Axis forces were killed in the aftermath of WWII, following a brutal war in which some 800,000 Yugoslavs, the vast majority civilians, were killed by Axis occupation forces and collaborators.

The foibe massacres were followed by the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus

The Istrian–Dalmatian exodus (; ; ) was the post- World War II exodus and departure of local ethnic Italians ( Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians) as well as ethnic Slovenes, Croats, and Istro-Romanians from the Yugoslav territory of ...

, which was the post-World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

expulsion and departure of local ethnic Italians (Istrian Italians

Istrian Italians are an ethnic group from the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic region of Istria in modern northwestern Croatia and southwestern Slovenia. Istrian Italians descend from the original Latinized population of Roman Empire, Roman Istria#Early h ...

and Dalmatian Italians

Dalmatian Italians are the historical Italian national minority living in the region of Dalmatia, now part of Croatia and Montenegro. Since the middle of the 19th century, the community, counting according to some sources nearly 20% of all Da ...

) from the Yugoslav territory of Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian and Slovene: ; ist, Eîstria; Istro-Romanian, Italian and Venetian: ; formerly in Latin and in Ancient Greek) is the largest peninsula within the Adriatic Sea. The peninsula is located at the head of the Adriatic betwe ...

, Kvarner

The Kvarner Gulf (, or , la, Sinus Flanaticus or ), sometimes also Kvarner Bay, is a bay in the northern Adriatic Sea, located between the Istrian peninsula and the northern Croatian Littoral mainland. The bay is a part of Croatia's internal ...

, the Julian March

Venezia Giulia, traditionally called Julian March (Serbo-Croatian, Slovene: ''Julijska krajina'') or Julian Venetia ( it, Venezia Giulia; vec, Venesia Julia; fur, Vignesie Julie; german: Julisch Venetien) is an area of southeastern Europe wh ...

, lost by Italy after the Treaty of Paris (1947), as well as Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

, towards Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, and in smaller numbers, towards the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America, North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World. ...

and Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

. According to various sources, the exodus is estimated to have amounted to between 230,000 and 350,000 Italians (the others being ethnic Slovenes

The Slovenes, also known as Slovenians ( sl, Slovenci ), are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Slovenia, and adjacent regions in Italy, Austria and Hungary. Slovenes share a common ancestry, Slovenian culture, culture, History ...

, Croats

The Croats (; hr, Hrvati ) are a South Slavic ethnic group who share a common Croatian ancestry, culture, history and language. They are also a recognized minority in a number of neighboring countries, namely Austria, the Czech Republic ...

, and Istro-Romanians, who chose to maintain Italian citizenship) leaving the areas in the aftermath of the conflict. From 1947, after the war, Italians were subject by Yugoslav authorities to less violent forms of intimidation, such as nationalization, expropriation, and discriminatory taxation, which gave them little option other than emigration. According to the census organized in Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = " Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capi ...

in 2001 and that organized in Slovenia

Slovenia ( ; sl, Slovenija ), officially the Republic of Slovenia (Slovene: , abbr.: ''RS''), is a country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the southeast, and ...

in 2002, the Italians who remained in the former Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label= Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavij ...

amounted to 21,894 people (2,258 in Slovenia and 19,636 in Croatia).

Number of victims

The number of those killed or left in ''foibe'' during and after the war is still unknown; it is difficult to establish and a matter of controversy. Estimates range from hundreds to twenty thousand. According to data gathered by a joint Slovene-Italian historical commission established in 1993, "the violence was further manifested in hundreds of

The number of those killed or left in ''foibe'' during and after the war is still unknown; it is difficult to establish and a matter of controversy. Estimates range from hundreds to twenty thousand. According to data gathered by a joint Slovene-Italian historical commission established in 1993, "the violence was further manifested in hundreds of summary execution

A summary execution is an execution in which a person is accused of a crime and immediately killed without the benefit of a full and fair trial. Executions as the result of summary justice (such as a drumhead court-martial) are sometimes includ ...

s - victims were mostly thrown into the Karst chasms (''foibe'') - and in the deportation of a great number of soldiers and civilians, who either wasted away or were killed during the deportation".

Historians Raoul Pupo and Roberto Spazzali, have estimated the total number of victims at about 5,000, and note that the targets were not "Italians", but military and repressive forces of the Fascist regime, and civilians associated with the regime. More recently, Pupo has revised the total victims estimates to 3,000 to 4,000. Italian historian Guido Rumici estimated the number of Italians executed, or died in Yugoslav concentration camps, as between 6,000 and 11,000, while Mario Pacor estimated that after the armistice about 400-500 people were killed in the foibe and about 4,000 were deported, many of whom were later executed. Other sources claim 20,000 victims.

It was not possible to extract all the corpses from the ''foibe'', some of which are deeper than several hundred meters; some sources are attempting to compile lists of locations and possible victim numbers. Between October and December 1943, the fire brigade

A fire department (American English) or fire brigade (Commonwealth English), also known as a fire authority, fire district, fire and rescue, or fire service in some areas, is an organization that provides fire prevention and fire suppression se ...

of Pola, helped by mine workers, recovered a total of 159 victims of the first wave of mass killings from the ''foibe'' of Vines (84 bodies), Terli (26 bodies), Treghelizza (2 bodies), Pucicchi (11 bodies), Villa Surani (26 bodies), Cregli (8 bodies) and Carnizza d'Arsia (2 bodies); another 44 corpses were recovered in the same period from two bauxite mines in Lindaro and Villa Bassotti.Foibe: revisionismo di Stato e amnesie della Repubblica/ref>Foibe, bilancio e rilettura

nonluoghi.info, February 2015; accessed 17 March 2016. More bodies were sighted, but not recovered. The most famous Basovizza foiba, was investigated by English and American forces, starting immediately on June 12, 1945. After 5 months of investigation and digging, all they found in the foiba were the remains of 150 German soldiers and one civilian killed in the final battles for Basovizza on April 29–30, 1945. The Italian mayor, Gianni Bartoli continued with investigations and digging until 1954, with speleologists entering the cave multiple time, yet they found nothing. Between November 1945 and April 1948, firefighters, speleologists and policemen inspected ''foibe'' and mine shafts in the "Zone A" of the

Free Territory of Trieste

The Free Territory of Trieste was an independent territory in Southern Europe between northern Italy and Yugoslavia, facing the north part of the Adriatic Sea, under direct responsibility of the United Nations Security Council in the aftermath ...

(mainly consisting in the surroundings of Trieste), where they recovered 369 corpses; another 95 were recovered from mass grave

A mass grave is a grave containing multiple human corpses, which may or may not be identified prior to burial. The United Nations has defined a criminal mass grave as a burial site containing three or more victims of execution, although an exact ...

s in the same area. At the time, no inspections were carried out either in the Yugoslav-controlled "Zone B", or in the rest of Istria.

Other foibe and mass graves were investigated in more recently in Istria and elsewhere in Slovenia and Croatia; for instance, human remains were discovered in the Idrijski Log ''foiba'' near Idrija

Idrija (, in older sources ''Zgornja Idrija''; german: (Ober)idria, it, Idria) is a town in western Slovenia. It is the seat of the Municipality of Idrija. It is located in the traditional region of Inner Carniola and is in the Gorizia Statisti ...

, Slovenia, in 1998; four skeletons were found in the foiba of Plahuti near Opatija in 2002; in the same year, a mass grave containing the remains of 52 Italians and 15 Germans, most likely all military, was discovered in Slovenia, not far from Gorizia; in 2005, the remains of about 130 people killed between the 1940s and the 1950s were recovered from four ''foibe'' located in northeastern Istria.

Background

Early history

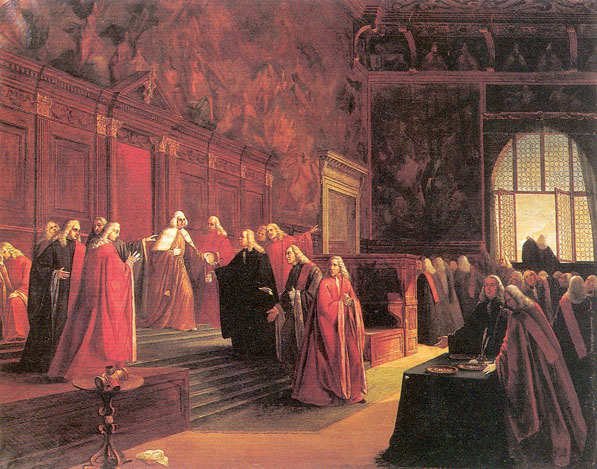

Via conquests, theRepublic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

, between the 9th century

The 9th century was a period from 801 ( DCCCI) through 900 ( CM) in accordance with the Julian calendar.

The Carolingian Renaissance and the Viking raids occurred within this period. In the Middle East, the House of Wisdom was founded in Abba ...

and 1797, extended its dominion to coastal parts of Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian and Slovene: ; ist, Eîstria; Istro-Romanian, Italian and Venetian: ; formerly in Latin and in Ancient Greek) is the largest peninsula within the Adriatic Sea. The peninsula is located at the head of the Adriatic betwe ...

and Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

. Thus Venice invaded and attacked Zadar

Zadar ( , ; historically known as Zara (from Venetian and Italian: ); see also other names), is the oldest continuously inhabited Croatian city. It is situated on the Adriatic Sea, at the northwestern part of Ravni Kotari region. Zadar ser ...

multiple times, especially devastating the city in 1202 when Venice used the crusaders

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

, on their Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

, to lay siege, then ransack, demolish and rob the city, the population fleeing into countryside. Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III ( la, Innocentius III; 1160 or 1161 – 16 July 1216), born Lotario dei Conti di Segni (anglicized as Lothar of Segni), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 to his death in 16 ...

excommunicated the Venetians and crusaders for attacking a Catholic city. The Venetians used the same Crusade to attack the Dubrovnik Republic, and force it to pay tribute, then continued to sack Christian Orthodox Constantinople where they looted

Looting is the act of stealing, or the taking of goods by force, typically in the midst of a military, political, or other social crisis, such as war, natural disasters (where law and civil enforcement are temporarily ineffective), or rioting. ...

, terrorized, and vandalized the city, killing 2.000 civilians, raping nuns and destroying Christian Churches, with Venice receiving a big portion of the plundered treasures.

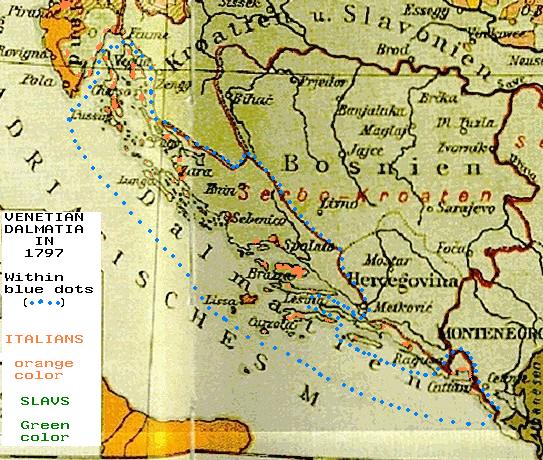

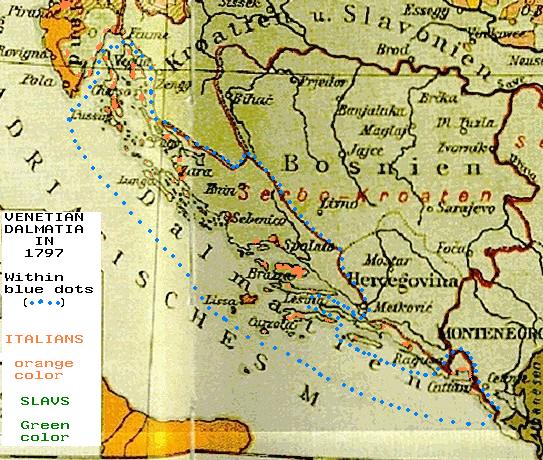

The coastal areas and cities of Istria came under Venetian Influence in the 9th century. In 1145, the cities of

The coastal areas and cities of Istria came under Venetian Influence in the 9th century. In 1145, the cities of Pula

Pula (; also known as Pola, it, Pola , hu, Pòla, Venetian; ''Pola''; Istriot: ''Puola'', Slovene: ''Pulj'') is the largest city in Istria County, Croatia, and the seventh-largest city in the country, situated at the southern tip of the I ...

, Koper

Koper (; it, Capodistria, hr, Kopar) is the fifth largest city in Slovenia. Located in the Istrian region in the southwestern part of the country, approximately five kilometres () south of the border with Italy and 20 kilometres () from Triest ...

and Izola

Izola (; it, Isola ) is a town in southwestern Slovenia on the Adriatic coast of the Istrian peninsula. It is the seat of the Municipality of Izola. Its name originates from Italian ''Isola'', which means 'island'.

History

An ancient Roman ...

rose against the Republic of Venice but were defeated, and were since further controlled by Venice. On 15 February 1267, Poreč

Poreč (; it, Parenzo; la, Parens or ; grc, Πάρενθος, Párenthos) is a town and municipality on the western coast of the Istrian peninsula, in Istria County, west Croatia. Its major landmark is the 6th-century Euphrasian Basilica, whi ...

was formally incorporated with the Venetian state. Other coastal towns followed shortly thereafter. The Republic of Venice gradually dominated the whole coastal area of western Istria and the area to Plomin

Plomin ( it, Fianona) is a village in the Croatian part of Istria, situated approximately 11 km north of Labin, on a hill 80 meters tall. It is a popular destination for tourists traveling through Istria by road.

Originally named ''F ...

on the eastern part of the peninsula. Dalmatia was first and finally sold to the Republic of Venice in 1409 but Venetian Dalmatia

Venetian Dalmatia ( la, Dalmatia Veneta) refers to parts of Dalmatia under the rule of the Republic of Venice, mainly from the 15th to the 18th centuries. Dalmatia was first sold to Venice in 1409 but Venetian Dalmatia was not fully consolidated ...

wasn't fully consolidated from 1420.

From the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

onwards numbers of Slavic people near and on the Adriatic coast were ever increasing, due to their expanding population and due to pressure from the Ottomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

pushing them from the south and east. This led to Italic people becoming ever more confined to urban areas, while the countryside was populated by Slavs, with certain isolated exceptions. In particular, the population was divided into urban-coastal communities (mainly Romance speakers) and rural communities (mainly Slavic speakers), with small minorities of Morlachs

Morlachs ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, Morlaci, Морлаци or , ; it, Morlacchi; ro, Morlaci) has been an exonym used for a rural Christian community in Herzegovina, Lika and the Dalmatian Hinterland. The term was initially used for a bilingual Vlach ...

and Istro-Romanians.

Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

influenced the neolatins of Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian and Slovene: ; ist, Eîstria; Istro-Romanian, Italian and Venetian: ; formerly in Latin and in Ancient Greek) is the largest peninsula within the Adriatic Sea. The peninsula is located at the head of the Adriatic betwe ...

and Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

until 1797, when it was conquered by Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

: Koper

Koper (; it, Capodistria, hr, Kopar) is the fifth largest city in Slovenia. Located in the Istrian region in the southwestern part of the country, approximately five kilometres () south of the border with Italy and 20 kilometres () from Triest ...

and Pula

Pula (; also known as Pola, it, Pola , hu, Pòla, Venetian; ''Pola''; Istriot: ''Puola'', Slovene: ''Pulj'') is the largest city in Istria County, Croatia, and the seventh-largest city in the country, situated at the southern tip of the I ...

were important centers of art and culture during the Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance ( it, Rinascimento ) was a period in Italian history covering the 15th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Europe and marked the trans ...

. From the Middle Ages to the 19th century, Italian and Slavic communities in Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian and Slovene: ; ist, Eîstria; Istro-Romanian, Italian and Venetian: ; formerly in Latin and in Ancient Greek) is the largest peninsula within the Adriatic Sea. The peninsula is located at the head of the Adriatic betwe ...

and Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

had lived peacefully side by side because they did not know the national identification, given that they generically defined themselves as "Istrians" and "Dalmatians", of "Romance" or "Slavic" culture.

Austrian Empire

The French victory of 1809 compelled Austria to cede a portion of its South Slav lands to France, Napoleon combinedCarniola

Carniola ( sl, Kranjska; , german: Krain; it, Carniola; hu, Krajna) is a historical region that comprised parts of present-day Slovenia. Although as a whole it does not exist anymore, Slovenes living within the former borders of the region s ...

, western Carinthia

Carinthia (german: Kärnten ; sl, Koroška ) is the southernmost Austrian state, in the Eastern Alps, and is noted for its mountains and lakes. The main language is German. Its regional dialects belong to the Southern Bavarian group. Carin ...

, Gorica (Gorizia

Gorizia (; sl, Gorica , colloquially 'old Gorizia' to distinguish it from Nova Gorica; fur, label= Standard Friulian, Gurize, fur, label= Southeastern Friulian, Guriza; vec, label= Bisiacco, Gorisia; german: Görz ; obsolete English ''Gori ...

), Istria, and parts of Croatia, Dalmatia, and Dubrovnik to form the Illyrian Provinces

The Illyrian Provinces sl, Ilirske province hr, Ilirske provincije sr, Илирске провинције it, Province illirichegerman: Illyrische Provinzen, group=note were an autonomous province of France during the First French Empire that e ...

. The Code Napoléon was introduced, and roads and schools were constructed. Local citizens were given administrative posts, and native languages were used to conduct official business. This sparked the Illyrian Movement for the cultural and linguistic unification of South Slavic lands.

After the fall of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

(1814), Istria, Kvarner and Dalmatia were annexed to the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central- Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

. Many Istrian Italians

Istrian Italians are an ethnic group from the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic region of Istria in modern northwestern Croatia and southwestern Slovenia. Istrian Italians descend from the original Latinized population of Roman Empire, Roman Istria#Early h ...

and Dalmatian Italians

Dalmatian Italians are the historical Italian national minority living in the region of Dalmatia, now part of Croatia and Montenegro. Since the middle of the 19th century, the community, counting according to some sources nearly 20% of all Da ...

looked with sympathy towards the Risorgimento

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

movement that fought for the unification of Italy. However, after the Third Italian War of Independence

The Third Italian War of Independence ( it, Terza Guerra d'Indipendenza Italiana) was a war between the Kingdom of Italy and the Austrian Empire fought between June and August 1866. The conflict paralleled the Austro-Prussian War and resulted in ...

(1866), when the Veneto

Veneto (, ; vec, Vèneto ) or Venetia is one of the 20 regions of Italy. Its population is about five million, ranking fourth in Italy. The region's capital is Venice while the biggest city is Verona.

Veneto was part of the Roman Empire unt ...

and Friuli

Friuli ( fur, Friûl, sl, Furlanija, german: Friaul) is an area of Northeast Italy with its own particular cultural and historical identity containing 1,000,000 Friulians. It comprises the major part of the autonomous region Friuli Venezia Giuli ...

regions were ceded by the Austrians

, pop = 8–8.5 million

, regions = 7,427,759

, region1 =

, pop1 = 684,184

, ref1 =

, region2 =

, pop2 = 345,620

, ref2 =

, region3 =

, pop3 = 197,990

, ref3 ...

to the newly formed Kingdom Italy, Istria and Dalmatia remained part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, together with other Italian-speaking areas on the eastern Adriatic. This triggered the gradual rise of Italian irredentism

Italian irredentism ( it, irredentismo italiano) was a nationalist movement during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Italy with irredentist goals which promoted the unification of geographic areas in which indigenous peoples ...

among many Italians in Istria, Kvarner and Dalmatia, who demanded the unification of the Julian March

Venezia Giulia, traditionally called Julian March (Serbo-Croatian, Slovene: ''Julijska krajina'') or Julian Venetia ( it, Venezia Giulia; vec, Venesia Julia; fur, Vignesie Julie; german: Julisch Venetien) is an area of southeastern Europe wh ...

, Kvarner

The Kvarner Gulf (, or , la, Sinus Flanaticus or ), sometimes also Kvarner Bay, is a bay in the northern Adriatic Sea, located between the Istrian peninsula and the northern Croatian Littoral mainland. The bay is a part of Croatia's internal ...

and Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

with Italy. The Italians in Istria, Kvarner and Dalmatia supported the Italian Risorgimento

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

: as a consequence, the Austrians saw the Italians as enemies and favored the Slav communities of Istria, Kvarner and Dalmatia,''Die Protokolle des Österreichischen Ministerrates 1848/1867. V Abteilung: Die Ministerien Rainer und Mensdorff. VI Abteilung: Das Ministerium Belcredi'', Wien, Österreichischer Bundesverlag für Unterricht, Wissenschaft und Kunst 1971

During the meeting of the Council of Ministers of 12 November 1866, Emperor

During the meeting of the Council of Ministers of 12 November 1866, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I (german: Franz Joseph Karl, hu, Ferenc József Károly, 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and the other states of the Habsburg monarchy from 2 December 1848 until ...

outlined a wide-ranging project aimed at the Germanization

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, people and culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationalism went hand in hand. In ling ...

or Slavization

Slavicisation or Slavicization, is the acculturation of something Slavic into a non-Slavic culture, cuisine, region, or nation. To a lesser degree, it also means acculturation or adoption of something non-Slavic into Slavic culture or terms. Th ...

of the areas of the empire with an Italian presence:

Istrian Italians

Istrian Italians are an ethnic group from the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic region of Istria in modern northwestern Croatia and southwestern Slovenia. Istrian Italians descend from the original Latinized population of Roman Empire, Roman Istria#Early h ...

were more than 50% of the total population for centuries, while making up about a third of the population in 1900. Dalmatia, especially its maritime cities, once had a substantial local ethnic Italian population (Dalmatian Italians

Dalmatian Italians are the historical Italian national minority living in the region of Dalmatia, now part of Croatia and Montenegro. Since the middle of the 19th century, the community, counting according to some sources nearly 20% of all Da ...

), making up 33% of the total population of Dalmatia in 1803, but this was reduced to 20% in 1816. In the 1910 Austro-Hungarian census, Istria had a population of 57.8% Slavic-speakers (Croat and Slovene), and 38.1% Italian speakers. For the Austrian Kingdom of Dalmatia

The Kingdom of Dalmatia ( hr, Kraljevina Dalmacija; german: Königreich Dalmatien; it, Regno di Dalmazia) was a crown land of the Austrian Empire (1815–1867) and the Cisleithanian half of Austria-Hungary (1867–1918). It encompassed the entire ...

, (i.e. Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

), the 1910 numbers were 96.2% Slavic speakers and 2.8% Italian speakers, compared to 12.5% Italian speakers in the first Austro-Hungarian census of 1865. Many of these Italian speakers were local Slavs who became Italianized due to Italian long being the only official language, and later returned to Slavic languages. In 1909 the Italian language

Italian (''italiano'' or ) is a Romance language of the Indo-European language family that evolved from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire. Together with Sardinian, Italian is the least divergent language from Latin. Spoken by about 8 ...

lost its status

Status (Latin plural: ''statūs''), is a state, condition, or situation, and may refer to:

* Status (law)

** City status

** Legal status, in law

** Political status, in international law

** Small entity status, in patent law

** Status confere ...

as the official language of Dalmatia in favor of Croatian only (previously both languages were recognized): thus Italian could no longer be used in the public and administrative sphere.

Historians note that while Slavs made up 80-95% of the Dalmatia populace, only Italian language schools existed until 1848, and due to restrictive voting laws, which allowed only wealthy property owners to vote, the Italian-speaking aristocratic minority retained political control of Dalmatia. They fought to keep Italian as the only official language, and opposed granting official languages rights to the Croatian language, spoken by the great majority of inhabitants. Only after Austria liberalized elections in 1870, allowing more majority Slavs to vote, did Croatian parties gain control. Croatian finally became an official language in Dalmatia in 1883, along with Italian. Yet minority Italian-speakers continued to wield strong influence, since Austria favored Italians for government work, thus in the Austrian capital of Dalmatia, Zara, the proportion of Italians continued to grow, making it the only Dalmatian city with an Italian majority.

When Italy took over the Veneto region, it sought to repress the language of the local Slovene minority. In 1911, complaining of local Italian efforts to falsely count Slovenes as Italians, the Trieste Slovene newspaper Edinost wrote: “We are here, we want to stay here and enjoy our rights! We throw the ruling clique the glove a duel, and we will not give up until artificial Trieste Italianism is crushed in dust, lying under our feet.” Due to these complaints, Austria carried a census recount, and the number of Slovenes increased by 50-60% in Trieste and Gorizia, proving Slovenes were initially falsely counted as Italians.

After World War I

Although a member of theCentral Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in W ...

, Italy remained neutral at the start of WWI, and soon launched secret negotiations with the Triple Entente, bargaining to participate in the war on its side, in exchange for significant territorial gains. To get Italy to join the war, in the secret 1915 Treaty of London the Entente promised Italy Istria and parts of Dalmatia, German-speaking South Tyrol

it, Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano – Alto Adige lld, Provinzia Autonoma de Balsan/Bulsan – Südtirol

, settlement_type = Autonomous province

, image_skyline =

, image_alt ...

, the Greek Dodecanese Islands

The Dodecanese (, ; el, Δωδεκάνησα, ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger plus 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Turkey's Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited. ...

, parts of Albania and Turkey, plus more territory for Italy's North Africa colonies.

After World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, the whole of the former Austrian Julian March