Foco on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A guerilla foco is a small cadre of revolutionaries operating in a nation's countryside. This guerilla organization was popularized by Che Guevara in his book

A guerilla foco is a small cadre of revolutionaries operating in a nation's countryside. This guerilla organization was popularized by Che Guevara in his book

Foco theory was originally based on Che Guevara's experiences in the Cuban Revolution. In which he was party of a guerilla army of 82 members who landed in Cuba on board of the '' Granma'' in December 1956 and initiated a guerrilla war in the

Foco theory was originally based on Che Guevara's experiences in the Cuban Revolution. In which he was party of a guerilla army of 82 members who landed in Cuba on board of the '' Granma'' in December 1956 and initiated a guerrilla war in the

chapter 2. The 26th of July Movement itself had a rural guerilla army as well as an urban underground that participated in the revolution. Che Guevara often accused the urban section of the movement as being without proper radicalism, which stirred internal controversy. The urban wing was responsible for arming the rural guerillas and engaged in its own urban warfare campaign. During the final months of the revolution an alliance of the Directorio Revolucionario Estudiantil, Popular Socialist Party, and 26th of July Movement was able to overthrow the Batista government. In their new provisional government the M-26-7 rebel army garnered the most popularity and influence.

by Dr. Peter Custers, ''Sri Lanka Guardian'', 24 February 2010. In '' Guerrilla Warfare'' (''La Guerra de Guerrillas''), Guevara did not count on a

Decree No. 261/75

. NuncaMas.org, ''Decretos de aniquilamiento''.

The strength of an idea

Revolution in the Revolution.

FROM CUBA TO BOLIVIA:GUEVARA’S FOCO THEORY IN PRACTICE

-

The Functionality of the Foco Theory

{{Marxist & Communist phraseology Che Guevara Marxism–Leninism Communist terminology Cuban Revolution Guerrilla warfare tactics Revolution terminology

A guerilla foco is a small cadre of revolutionaries operating in a nation's countryside. This guerilla organization was popularized by Che Guevara in his book

A guerilla foco is a small cadre of revolutionaries operating in a nation's countryside. This guerilla organization was popularized by Che Guevara in his book Guerilla Warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tactic ...

, which was based on his experiences in the Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution ( es, Revolución Cubana) was carried out after the 1952 Cuban coup d'état which placed Fulgencio Batista as head of state and the failed mass strike in opposition that followed. After failing to contest Batista in co ...

. Guevara would go on to argue that a foco was politically necessary for the success of a socialist revolution. Originally Guevara theorized that a foco was only useful in overthrowing personalistic military dictatorships and not liberal democratic capitalism where a peaceful overthrow was believed possible. Years later Guevara would revise his thesis and argue all nations in Latin America, including liberal democracies could be overthrown by a guerilla foco. Eventually the foco thesis would be that political conditions would not even need to be ripe for revolutions to be successful, since the sheer existence of a guerilla foco would create ripe conditions by itself. Guevara's theory of foco known as () was self-described as the application of Marxism-Leninism to Latin American conditions, and would later be further popularized by author Régis Debray

Jules Régis Debray (; born 2 September 1940) is a French philosopher, journalist, former government official and academic. He is known for his theorization of mediology, a critical theory of the long-term transmission of cultural meaning in h ...

. The proposed necessity of a guerilla foco proved influential in Latin America, but was also heavily criticized by other socialists.

This theory of foco proved heavily influential among armed militants around the world. Che Guevara's success in the Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution ( es, Revolución Cubana) was carried out after the 1952 Cuban coup d'état which placed Fulgencio Batista as head of state and the failed mass strike in opposition that followed. After failing to contest Batista in co ...

was seen as proof of his thesis and thus popularized foco theory. Some of the famous militant groups to adopt foco theory included the Red Army Faction

The Red Army Faction (RAF, ; , ),See the section "Name" also known as the Baader–Meinhof Group or Baader–Meinhof Gang (, , active 1970–1998), was a West German far-left Marxist-Leninist urban guerrilla group founded in 1970.

The ...

, Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief th ...

, and Weather Underground

The Weather Underground was a far-left militant organization first active in 1969, founded on the Ann Arbor campus of the University of Michigan. Originally known as the Weathermen, the group was organized as a faction of Students for a Democr ...

. The theory became especially popular in the New Left for its breaking with the strategy of incremental political change supported by the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, while also encouraging the possibility of immediate revolution.

Background

Cuban Revolution

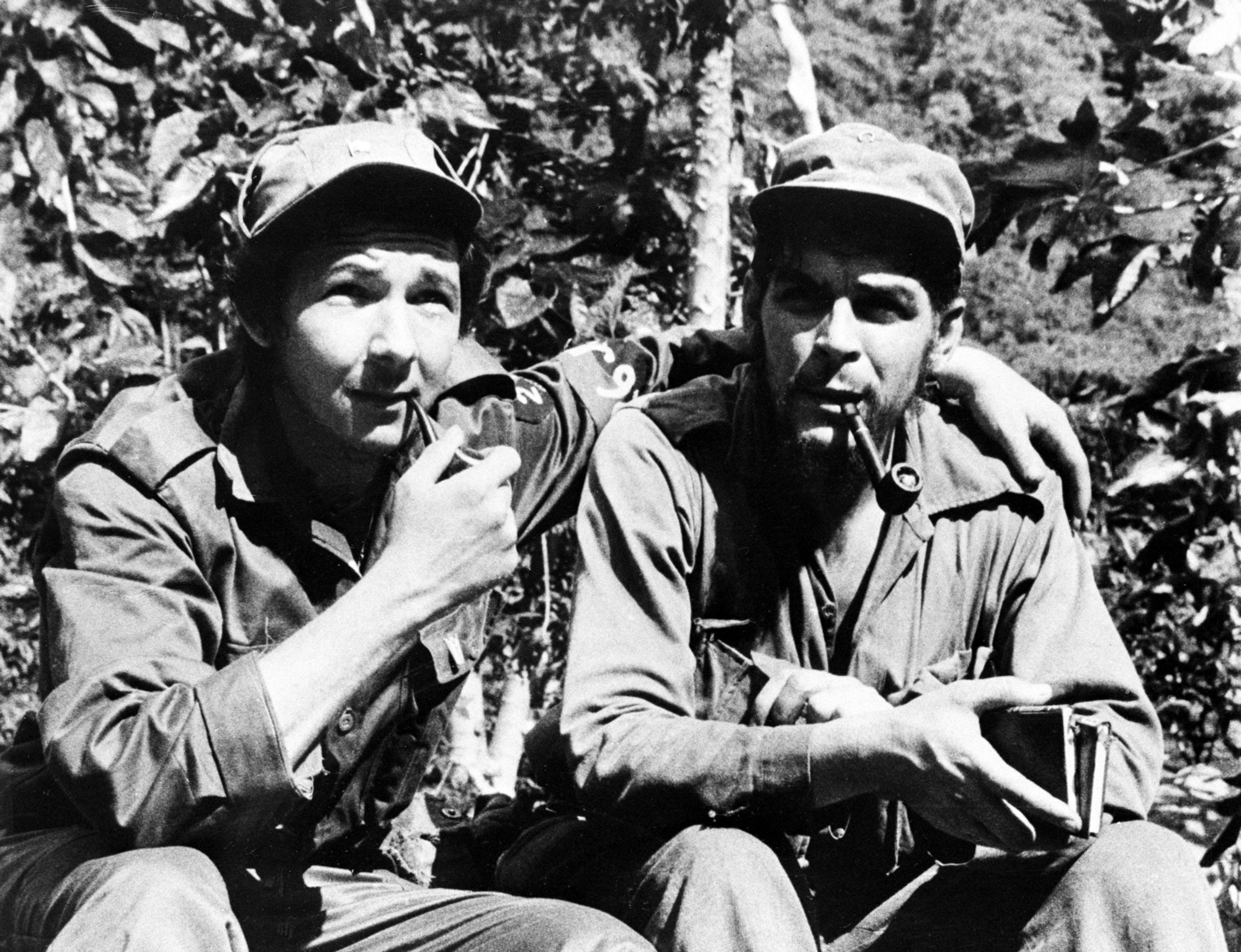

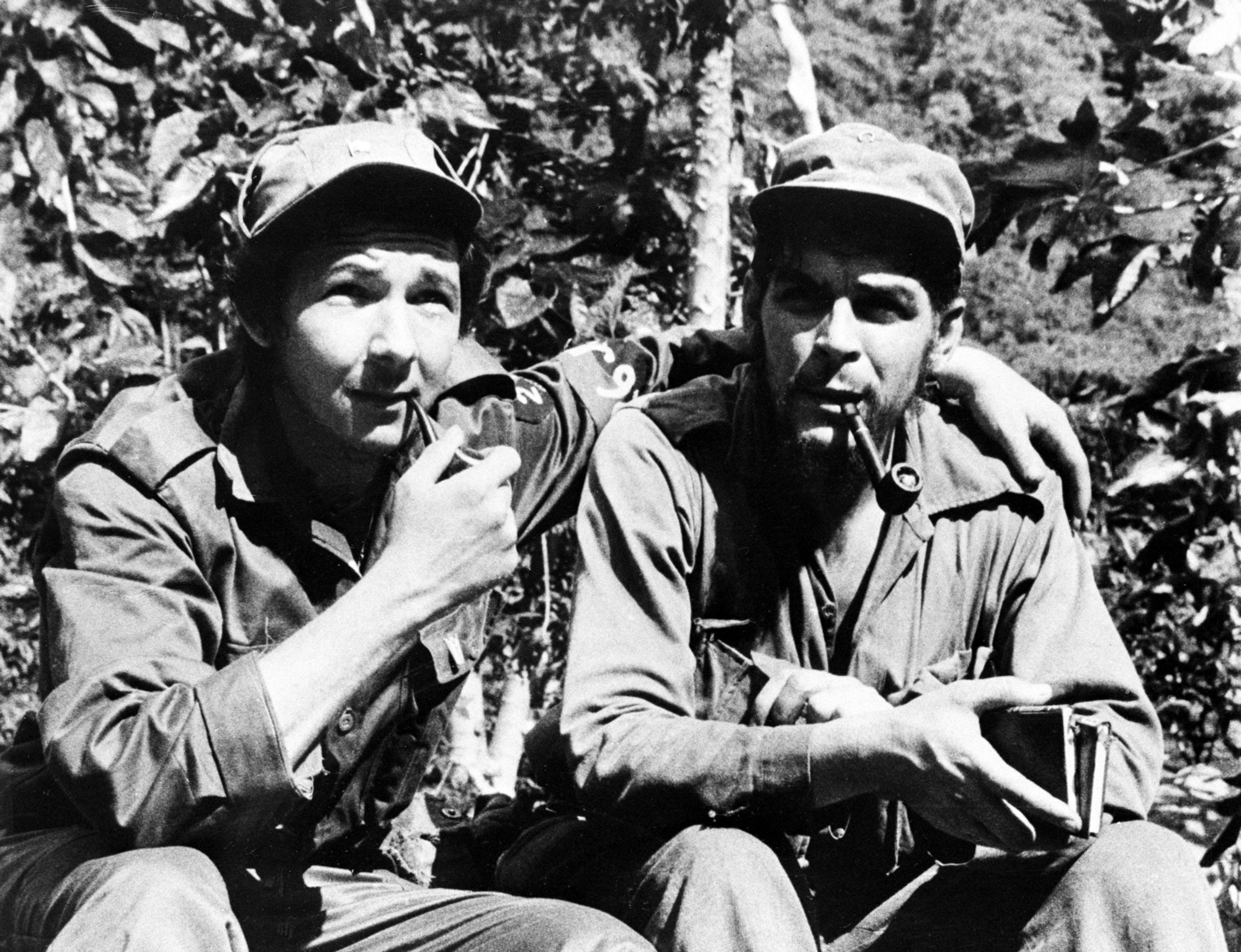

Foco theory was originally based on Che Guevara's experiences in the Cuban Revolution. In which he was party of a guerilla army of 82 members who landed in Cuba on board of the '' Granma'' in December 1956 and initiated a guerrilla war in the

Foco theory was originally based on Che Guevara's experiences in the Cuban Revolution. In which he was party of a guerilla army of 82 members who landed in Cuba on board of the '' Granma'' in December 1956 and initiated a guerrilla war in the Sierra Maestra

The Sierra Maestra is a mountain range that runs westward across the south of the old Oriente Province in southeast Cuba, rising abruptly from the coast. The range falls mainly within the Santiago de Cuba and in Granma Provinces. Some view it a ...

. During two years, the poorly armed ''escopeteros

During the Cuban revolution, escopeteros were essential scouts and pickets from the Sierra Maestra and other mountain ranges to the plains. The "escopeteros" were responsible for semi-continuously holding terrain against smaller sized Batista pat ...

'', at times fewer than 200 men, won victories against Fulgencio Batista

Fulgencio Batista y Zaldívar (; ; born Rubén Zaldívar, January 16, 1901 – August 6, 1973) was a Cuban military officer and politician who served as the elected president of Cuba from 1940 to 1944 and as its U.S.-backed military dictator ...

's army and police force, which numbered between 30,000 and 40,000 in strength."Bockman"chapter 2. The 26th of July Movement itself had a rural guerilla army as well as an urban underground that participated in the revolution. Che Guevara often accused the urban section of the movement as being without proper radicalism, which stirred internal controversy. The urban wing was responsible for arming the rural guerillas and engaged in its own urban warfare campaign. During the final months of the revolution an alliance of the Directorio Revolucionario Estudiantil, Popular Socialist Party, and 26th of July Movement was able to overthrow the Batista government. In their new provisional government the M-26-7 rebel army garnered the most popularity and influence.

Consolidation of the Cuban Revolution

Che Guevara played an integral role as one of the first historians of the Cuban Revolution. After the revolutionaries victory, Guevara published various articles in Cuba of his experiences in the revolution. These articles helped formalize his foco theory and a history of the Cuban Revolution that stressed the role of the rural guerillas as the main revolutionary force. This idea of the lone rural guerrillas deciding the revolution became immediately popular among the rebel army while consolidating their new government, and became a driving force in Cuban politics as a nation-building myth. Many early propnents saw the potential of repeating the model of the Cuban Revolution through out Latin America, and often encouraged it.Theory

Rural guerilla strategy

While foco theory drew from previous Marxist–Leninist ideas and theMaoist

Maoism, officially called Mao Zedong Thought by the Chinese Communist Party, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed to realise a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of Ch ...

strategy of "protracted people's war

People's war (Chinese language, Chinese: 人民战争), also called protracted people's war, is a Maoism, Maoist military strategy. First developed by the Chinese Communism, communist revolutionary leader Mao Zedong (1893–1976), the basic conc ...

", it simultaneously broke with many of the mid- Cold War era's established communist parties

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. ...

. Despite Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

's eager support for "wars of national liberation

Wars of national liberation or national liberation revolutions are conflicts fought by nations to gain independence. The term is used in conjunction with wars against foreign powers (or at least those perceived as foreign) to establish separa ...

" and the foco's own enthusiasm for Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

patronage, Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

's own Popular Socialist Party had retreated from active confrontation with the Fulgencio Batista

Fulgencio Batista y Zaldívar (; ; born Rubén Zaldívar, January 16, 1901 – August 6, 1973) was a Cuban military officer and politician who served as the elected president of Cuba from 1940 to 1944 and as its U.S.-backed military dictator ...

regime and Castroism/Guevarism

Guevarism is a theory of communist revolution and a military strategy of guerrilla warfare associated with Marxist–Leninist revolutionary Ernesto "Che" Guevara, a leading figure of the Cuban Revolution who believed in the idea of Marxism–Le ...

substituted the foco militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

for the more traditional vanguard party

Vanguardism in the context of Leninist revolutionary struggle, relates to a strategy whereby the most class-conscious and politically "advanced" sections of the proletariat or working class, described as the revolutionary vanguard, form organ ...

.

Like other communist and socialist theorists of his era (such as Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC) ...

and Ho Chi Minh

(: ; born ; 19 May 1890 – 2 September 1969), commonly known as (' Uncle Hồ'), also known as ('President Hồ'), (' Old father of the people') and by other aliases, was a Vietnamese revolutionary and statesman. He served as P ...

), Che Guevara

Ernesto Che Guevara (; 14 June 1928The date of birth recorded on /upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/78/Ernesto_Guevara_Acta_de_Nacimiento.jpg his birth certificatewas 14 June 1928, although one tertiary source, (Julia Constenla, quot ...

believed that people living in countries still ruled by colonial powers

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their relig ...

, or living in countries subject to newer forms of economic exploitation, could best defeat colonial power

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their relig ...

s by taking up arms. Guevara also believed in fostering armed resistance not by concentrating one's forces in urban centers, but rather through the accumulation of strength in mountainous and rural regions where the enemy had less presence."The Legacy of Che Guevara: Internationalism Today"by Dr. Peter Custers, ''Sri Lanka Guardian'', 24 February 2010. In '' Guerrilla Warfare'' (''La Guerra de Guerrillas''), Guevara did not count on a

Leninist

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the establishm ...

insurrection led by the proletariat as had happened during the 1917 October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

, but on popular uprisings which would gain strength in rural areas and would overthrow the regime. The vanguard guerrilla was supposed to bolster the population's morale, not to take control of the state apparatus

A state is a centralized political organization that imposes and enforces rules over a population within a territory. There is no undisputed definition of a state. One widely used definition comes from the German sociologist Max Weber: a "stat ...

itself and this overthrow would occur without any external or foreign help. According to him, guerrillas were to be supported by conventional armed forces: It is well established that guerrilla warfare constitutes one of the phases of war; this phase can not, on its own, lead to victory.Guevara added that this theory was formulated for

developing countries

A developing country is a sovereign state with a lesser developed industrial base and a lower Human Development Index (HDI) relative to other countries. However, this definition is not universally agreed upon. There is also no clear agreem ...

and that the guerrilleros had to look for support among both the workers and the peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasant ...

s.

Guerilla "new man"

The guerilla foco will be able to draw the support of the rural peasantry by demonstrating impeccable moral character and self-sacrifice. In the armed struggle the guerillas themselves would be shaped by hardship into individuals who had an affinity for solidarity and justice. Once the guerillas overthrow the existing government and come into power, the moral spirit of the guerillas would become the national ethos of the new government.Legacy

Authoritarian reaction

Many who opposed the formation of leftist guerillas took a focused approach to extinguish rural rebel groups from forming who were inspired by ''foquismo''. These measures were often supported by the United States and involved tortuting and "disappearing" political enemies. The development of guerrilla focos in various Latin American countries has been a factor proposed by historians, that legitimized military takeovers of their respective nations in order to defend against guerillas.Argentina's People's Revolutionary Army

InArgentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

, the People's Revolutionary Army (ERP), led by Roberto Santucho, attempted to create a ''foco'' in the Tucumán Province

Tucumán () is the most densely populated, and the second-smallest by land area, of the provinces of Argentina.

Located in the northwest of the country, the province has the capital of San Miguel de Tucumán, often shortened to Tucumán. Neigh ...

. The attempt failed after the government of Isabel Perón signed in February 1975 the secret presidential decree 261, which ordered the army to neutralize and/or annihilate the ERP. Destined to collapse without any external pressure, ERP was not supported by a foreign power and lacked support of the working class. Operativo Independencia

Operativo Independencia ("Operation Independence") was a 1975 Argentine military operation in Tucumán Province to crush the People's Revolutionary Army (ERP), a Guevarist guerrilla group which tried to create a Vietnam-style war front in the no ...

gave power to the Argentine Armed Forces to "execute all military operations necessary for the effects of neutralizing or annihilating the action of subversive elements acting in the Province of Tucumán".. NuncaMas.org, ''Decretos de aniquilamiento''.

Criticism

Urban guerilla strategists

Abraham Guillén was a writer who frequently made studies of urban warfare in European revolutions, and noted critic of foco theory. While he agreed with Guevara in their shared criticism of American imperialism, Guillén argued that the foco strategy was unideal compared to a strategy of urban warfare. Guillén regarded the foco as petit-bourgeois in origin. He regarded that very few peasants and workers actually joined these guerilla armies. He also argued that these rural guerillas only supplied for easy victories by the reigning state power who could easily defeat isolated rebels in the countryside who lacked connections to military resources. Guillén instead argued revolution was possible during dire political crisis, with a mass workers alliance, and taking place in urban centers where most modernized nations populations resided. The Tupamaros guerillas of Uruguay are also noted critics of foco theory. While the Tupamaros agreed with much of Guevara's theory of revolution, they argued that the rural theatre was inefficient for a rebel army. The urban setting houses a greater population which means more sympathizers to rely on. A rural setting is also open to military attack while a city is more populated and delicate which discourages open combat by the state.See also

*Guevarism

Guevarism is a theory of communist revolution and a military strategy of guerrilla warfare associated with Marxist–Leninist revolutionary Ernesto "Che" Guevara, a leading figure of the Cuban Revolution who believed in the idea of Marxism–Le ...

* 26 of July Movement

* National Liberation Army

* Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia

The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – People's Army ( es, link=no, Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de ColombiaEjército del Pueblo, FARC–EP or FARC) is a Marxist–Leninist guerrilla group involved in the continuing Colombian confl ...

* National Liberation Army

* Tupamaro

* Oriental Revolutionary Movement

* Paraguayan People's Army

* Fidel Castro

* People's war

People's war ( Chinese: 人民战争), also called protracted people's war, is a Maoist military strategy. First developed by the Chinese communist revolutionary leader Mao Zedong (1893–1976), the basic concept behind people's war is to main ...

* Urban guerrilla warfare

An urban guerrilla is someone who fights a government using unconventional warfare or domestic terrorism in an urban environment.

Theory and history

The urban guerrilla phenomenon is essentially one of industrialised society, resting bot ...

* Wars of national liberation

Wars of national liberation or national liberation revolutions are conflicts fought by nations to gain independence. The term is used in conjunction with wars against foreign powers (or at least those perceived as foreign) to establish separa ...

Notes

References

* Guevara, Ernesto: '' Guerrilla Warfare'', Souvenir Press Ltd, paperback, .External links

The strength of an idea

Revolution in the Revolution.

FROM CUBA TO BOLIVIA:GUEVARA’S FOCO THEORY IN PRACTICE

-

University of Calgary

The University of Calgary (U of C or UCalgary) is a public research university located in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. The University of Calgary started in 1944 as the Calgary branch of the University of Alberta, founded in 1908, prior to being ins ...

The Functionality of the Foco Theory

{{Marxist & Communist phraseology Che Guevara Marxism–Leninism Communist terminology Cuban Revolution Guerrilla warfare tactics Revolution terminology