Flying Boats on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a

The Frenchman

The Frenchman

Henri Fabre (1882–1984)"

Monash University Centre for Telecommunications and Information Engineering, 15 May 2002. Retrieved: 9 May 2008. Fabre's first successful take off and landing by a powered floatplane inspired other aviators and he designed floats for several other flyers. The first hydro-aeroplane competition was held in

In 1913, the '' Daily Mail'' newspaper put up a £10,000 prize for the first non-stop aerial crossing of the Atlantic which was soon "enhanced by a further sum" from the Women's Aerial League of Great Britain. American businessman Rodman Wanamaker became determined that the prize should go to an American aircraft and commissioned the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company to design and build an aircraft capable of making the flight. Curtiss' development of the ''Flying Fish'' flying boat in 1913 brought him into contact with

In 1913, the '' Daily Mail'' newspaper put up a £10,000 prize for the first non-stop aerial crossing of the Atlantic which was soon "enhanced by a further sum" from the Women's Aerial League of Great Britain. American businessman Rodman Wanamaker became determined that the prize should go to an American aircraft and commissioned the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company to design and build an aircraft capable of making the flight. Curtiss' development of the ''Flying Fish'' flying boat in 1913 brought him into contact with

At Felixstowe, Porte made advances in flying boat design and developed a practical hull design with the distinctive "Felixstowe notch". Porte's first design to be implemented in Felixstowe was the Felixstowe Porte Baby, a large, three-engined biplane flying-boat, powered by one central pusher and two outboard tractor Rolls-Royce Eagle engines.

Porte modified an H-4 with a new hull whose improved hydrodynamic qualities made taxiing, take-off and landing much more practical, and called it the Felixstowe F.1.

Porte's innovation of the "Felixstowe notch" enabled the craft to overcome suction from the water more quickly and break free for flight much more easily. This made operating the craft far safer and more reliable, although similar devices had been in use in France since 1911. The "notch" breakthrough would soon after evolve into a "step", with the rear section of the lower hull sharply recessed above the forward lower hull section, and that characteristic became a feature of both flying boat hulls and floatplane floats. The resulting aircraft would be large enough to carry sufficient fuel to fly long distances and could berth alongside ships to take on more fuel.

Porte then designed a similar hull for the larger

At Felixstowe, Porte made advances in flying boat design and developed a practical hull design with the distinctive "Felixstowe notch". Porte's first design to be implemented in Felixstowe was the Felixstowe Porte Baby, a large, three-engined biplane flying-boat, powered by one central pusher and two outboard tractor Rolls-Royce Eagle engines.

Porte modified an H-4 with a new hull whose improved hydrodynamic qualities made taxiing, take-off and landing much more practical, and called it the Felixstowe F.1.

Porte's innovation of the "Felixstowe notch" enabled the craft to overcome suction from the water more quickly and break free for flight much more easily. This made operating the craft far safer and more reliable, although similar devices had been in use in France since 1911. The "notch" breakthrough would soon after evolve into a "step", with the rear section of the lower hull sharply recessed above the forward lower hull section, and that characteristic became a feature of both flying boat hulls and floatplane floats. The resulting aircraft would be large enough to carry sufficient fuel to fly long distances and could berth alongside ships to take on more fuel.

Porte then designed a similar hull for the larger  The

The  The Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company independently developed its designs into the small Model "F", the larger Model "K" (several of which were sold to the Russian Naval Air Service), and the Model "C" for the U.S. Navy. Curtiss among others also built the Felixstowe F.5 as the Curtiss F5L, based on the final Porte hull designs and powered by American Liberty engines.

Meanwhile, the pioneering flying boat designs of François Denhaut had been steadily developed by the Franco-British Aviation Company into a range of practical craft. Smaller than the Felixstowes, several thousand FBAs served with almost all of the Allied forces as reconnaissance craft, patrolling the North Sea, Atlantic and Mediterranean oceans.

In Italy, several flying boats were developed, starting with the L series, and progressing with the M series. The

The Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company independently developed its designs into the small Model "F", the larger Model "K" (several of which were sold to the Russian Naval Air Service), and the Model "C" for the U.S. Navy. Curtiss among others also built the Felixstowe F.5 as the Curtiss F5L, based on the final Porte hull designs and powered by American Liberty engines.

Meanwhile, the pioneering flying boat designs of François Denhaut had been steadily developed by the Franco-British Aviation Company into a range of practical craft. Smaller than the Felixstowes, several thousand FBAs served with almost all of the Allied forces as reconnaissance craft, patrolling the North Sea, Atlantic and Mediterranean oceans.

In Italy, several flying boats were developed, starting with the L series, and progressing with the M series. The

In September 1919, British company Supermarine started operating the first flying boat service in the world, from Woolston to Le Havre in

In September 1919, British company Supermarine started operating the first flying boat service in the world, from Woolston to Le Havre in  Delivering the mail as quickly as possible generated a lot of competition and some innovative designs. One variant of the Short Empire flying boats was the strange-looking " Maia and Mercury". It was a four-engined floatplane "Mercury" (the winged messenger) fixed on top of "Maia", a heavily modified Short Empire flying boat. The larger Maia took off, carrying the smaller Mercury loaded to a weight greater than it could take off with. This allowed the Mercury to carry sufficient fuel for a direct trans-Atlantic flight with the mail.Norris 1966, pp. 11–12. Unfortunately this was of limited usefulness, and the Mercury had to be returned from America by ship. The Mercury did set a number of distance records before

Delivering the mail as quickly as possible generated a lot of competition and some innovative designs. One variant of the Short Empire flying boats was the strange-looking " Maia and Mercury". It was a four-engined floatplane "Mercury" (the winged messenger) fixed on top of "Maia", a heavily modified Short Empire flying boat. The larger Maia took off, carrying the smaller Mercury loaded to a weight greater than it could take off with. This allowed the Mercury to carry sufficient fuel for a direct trans-Atlantic flight with the mail.Norris 1966, pp. 11–12. Unfortunately this was of limited usefulness, and the Mercury had to be returned from America by ship. The Mercury did set a number of distance records before  The German

The German

The military value of flying boats was well-recognized, and every country bordering on water operated them in a military capacity at the outbreak of the

The military value of flying boats was well-recognized, and every country bordering on water operated them in a military capacity at the outbreak of the  The largest flying boat of the war was the Blohm & Voss BV 238, which was also the heaviest plane to fly during the Second World War and the largest aircraft built and flown by any of the

The largest flying boat of the war was the Blohm & Voss BV 238, which was also the heaviest plane to fly during the Second World War and the largest aircraft built and flown by any of the  The Imperial Japanese Navy operated what has been often described as the best flying boat of the conflict, the Kawanishi H8K. Its design was based upon its immediate predecessor, the Kawanishi H6K, but was a considerably larger and longer-ranged aircraft designed at the request of the Navy just prior to the outbreak of war. On the night of 4 March 1942, two H8Ks conducted the second raid on Pearl Harbor, refuelling en route by submarine at French Frigate Shoals in order to achieve the necessary range; poor visibility caused this attack on Pearl Harbor to fail to accomplish any significant damage. An improved H8K2 variant of the type, featuring extremely heavy defensive armament, was also introduced.

In November 1939, IAL was restructured into three separate companies: British European Airways, British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC), and

The Imperial Japanese Navy operated what has been often described as the best flying boat of the conflict, the Kawanishi H8K. Its design was based upon its immediate predecessor, the Kawanishi H6K, but was a considerably larger and longer-ranged aircraft designed at the request of the Navy just prior to the outbreak of war. On the night of 4 March 1942, two H8Ks conducted the second raid on Pearl Harbor, refuelling en route by submarine at French Frigate Shoals in order to achieve the necessary range; poor visibility caused this attack on Pearl Harbor to fail to accomplish any significant damage. An improved H8K2 variant of the type, featuring extremely heavy defensive armament, was also introduced.

In November 1939, IAL was restructured into three separate companies: British European Airways, British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC), and

"The Martin Mariner, Mars, & Marlin Flying Boats."

''Vectorsite.'' Retrieved: 20 May 2012.

After the end of the Second World War, the use of flying boats rapidly declined for several reasons. The ability to land on water became less of an advantage owing to the considerable increase in the number and length of land based runways during the conflict. Furthermore the commercial competitiveness of flying boats diminished, as their design compromised aerodynamic efficiency and speed in order to accommodate waterborne takeoff and landing. New land-based airliners such as the Lockheed Constellation and Douglas DC-4 were developed with comparable reliability, speed, and long-range. The new landplanes were relatively easy to fly, and did not require the extensive pilot training programs mandated for seaplane operations. One of the 314's most experienced pilots said, "We were indeed glad to change to DC-4s, and I argued daily for eliminating all flying boats. The landplanes were much safer. No one in the operations department... had any idea of the hazards of flying boat operations. The main problem now was lack of the very high level of experience and competence required of seaplane pilots".

The

After the end of the Second World War, the use of flying boats rapidly declined for several reasons. The ability to land on water became less of an advantage owing to the considerable increase in the number and length of land based runways during the conflict. Furthermore the commercial competitiveness of flying boats diminished, as their design compromised aerodynamic efficiency and speed in order to accommodate waterborne takeoff and landing. New land-based airliners such as the Lockheed Constellation and Douglas DC-4 were developed with comparable reliability, speed, and long-range. The new landplanes were relatively easy to fly, and did not require the extensive pilot training programs mandated for seaplane operations. One of the 314's most experienced pilots said, "We were indeed glad to change to DC-4s, and I argued daily for eliminating all flying boats. The landplanes were much safer. No one in the operations department... had any idea of the hazards of flying boat operations. The main problem now was lack of the very high level of experience and competence required of seaplane pilots".

The  On 22 August 1952, the

On 22 August 1952, the

"Japan's defense industry is super excited about this amphibious plane."

''The Week'', 10 September 2015. Shin Meiwa developed further flying boat concepts around this period, including the ''Shin Meiwa MS'' (Medium Seaplane) a 300-passenger long-range flying boat with its own beaching gear; and the gargantuan ''Shin Meiwa GS'' (Giant Seaplane) with a capacity of 1200 passengers seated on three decks.

"Big Wings: The Largest Aeroplanes Ever Built."

Pen and Sword, 2005. . * * Legg, David. ''Consolidated PBY Catalina: The Peacetime Record''. Annapolis, Maryland: US Naval Institute Press, 2002. . * London, Peter. ''British Flying Boats''. Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing, 2003. . * London, Peter. ''Saunders and Saro Aircraft since 1917''. London, UK: Conway Maritime Press Ltd, 1988. . * Nevin, David. ''The Pathfinders'' (The Epic of Flight series). Alexandria, Virginia: Time Life Books, 1980. . * * Norris, Geoffrey. ''The Short Empire Boats'' (Aircraft in Profile Number 84). Leatherhead, Surrey, UK: Profile Publications Ltd., 1966. * Norris, Geoffrey. ''The Short Sunderland (Aircraft in Profile number 189).'' London: Profile Publications, 1967. * * * * * Werner, H. A. '' Iron Coffins: A U-boat Commander's War, 1939–45.'' London: Cassells, 1999. . * Yenne, Bill. ''Seaplanes & Flying Boats: A Timeless Collection from Aviation's Golden Age''. New York: BCL Press, 2003. .

When Boats Had Wings, June 1963

detail article '' Popular Science''. * : BBC documentary film, 1980. {{DEFAULTSORT:Flying Boat Aircraft configurations

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* Chassis, of an armored fighting vehicle

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a ship

* Submarine hull

Mathematics

* Affine hull, in affi ...

, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fuselage-mounted floats for buoyancy. Though the fuselage provides buoyancy, flying boats may also utilize under-wing floats or wing-like projections (called sponson

Sponsons are projections extending from the sides of land vehicles, aircraft or watercraft to provide protection, stability, storage locations, mounting points for weapons or other devices, or equipment housing.

Watercraft

On watercraft, a spon ...

s) extending from the fuselage for additional stability. Flying boats often lack landing gear which would allow them to land on the ground, though many modern designs are convertible amphibious aircraft which may switch between landing gear and flotation mode for water or ground takeoff and landing.

Ascending into common use during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, flying boats rapidly grew in both scale and capability during the interwar period, during which time numerous operators found commercial success with the type. Flying boats were some of the largest aircraft of the first half of the 20th century, exceeded in size only by bombers developed during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. Their advantage lay in using water instead of expensive land-based runways, making them the basis for international airline

An airline is a company that provides air transport services for traveling passengers and freight. Airlines use aircraft to supply these services and may form partnerships or alliances with other airlines for codeshare agreements, in wh ...

s in the interwar period. They were also commonly used as maritime patrol aircraft and air-sea rescue, particularly during times of conflict. Flying boats such as the PBY Catalina and Short Sunderland played key roles in both the Pacific Theater and the Atlantic of the Second World War.

The popularity of flying boats gradually trailed off during the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

era, partially because of the difficulty in maintaining operations in inclement weather when sea states may easily prevent taking off and landing while land based aircraft are unaffected, and investments in airports during the conflict that eased the introduction of larger, and more efficient, land-based airliners. Despite being largely overshadowed, limited use of the type continued with some operators, such as in the case of the Shin Meiwa US-1A

The Shin Meiwa PS-1 and US-1A is a large STOL aircraft designed for anti-submarine warfare (ASW) and air-sea rescue (SAR) work respectively by Japanese aircraft manufacturer Shin Meiwa. The PS-1 anti-submarine warfare (ASW) variant is a flying ...

and the Martin JRM Mars

The Martin JRM Mars is a large, four-engined cargo transport flying boat designed and built by the Martin Company for the United States Navy during World War II. It was the largest Allied flying boat to enter production, although only seven ...

. In the 21st century, flying boats maintain a few niche uses, such as dropping water on forest fires, air transport around archipelagos, and access to undeveloped areas. Many modern seaplane variants, whether float or flying boat types, are convertible amphibious aircraft where either landing gear or flotation modes may be used to land and take off.

History

Early pioneers

The Frenchman

The Frenchman Alphonse Pénaud

Alphonse Pénaud (31 May 1850 – 22 October 1880), was a 19th-century French pioneer of aviation design and engineering. He was the originator of the use of twisted rubber to power model aircraft, and his 1871 model airplane, which he called ...

filed the first patent for a flying machine with a boat hull and retractable landing gear in 1876, but Austrian Wilhelm Kress is credited with building the first seaplane '' Drachenflieger'' in 1898, although its two 30 hp Daimler engines were inadequate for take-off and it later sank when one of its two floats collapsed.Nicolaou 1998,

On 6 June 1905, Gabriel Voisin took off and landed on the River Seine with a towed kite glider on floats. The first of his unpowered flights was 150 yards. He later built a powered floatplane in partnership with Louis Blériot, but the machine was unsuccessful.

Other pioneers also attempted to attach floats to aircraft in Britain, Australia, France and the USA.

On 28 March 1910, Frenchman Henri Fabre flew the first successful powered floatplane, the Gnome Omega–powered ''hydravion'', a trimaran floatplane.Naughton, Russell.Henri Fabre (1882–1984)"

Monash University Centre for Telecommunications and Information Engineering, 15 May 2002. Retrieved: 9 May 2008. Fabre's first successful take off and landing by a powered floatplane inspired other aviators and he designed floats for several other flyers. The first hydro-aeroplane competition was held in

Monaco

Monaco (; ), officially the Principality of Monaco (french: Principauté de Monaco; Ligurian: ; oc, Principat de Mónegue), is a sovereign city-state and microstate on the French Riviera a few kilometres west of the Italian region of Lig ...

in March 1912, featuring aircraft using floats from Fabre, Curtiss, Tellier and Farman. This led to the first scheduled seaplane passenger services at Aix-les-Bains

Aix-les-Bains (, ; frp, Èx-los-Bens; la, Aquae Gratianae), locally simply Aix, is a commune in the southeastern French department of Savoie.

, using a five-seat Sanchez-Besa from 1 August 1912. The French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

ordered its first floatplane in 1912.

In 1911–12, François Denhaut constructed the first flying boat, with a fuselage forming a hull, using various designs to give hydrodynamic lift at take-off. Its first successful flight was on 13 April 1912. Throughout 1910 and 1911 American pioneering aviator Glenn Curtiss developed his floatplane into the successful Curtiss Model D land-plane, which used a larger central float and sponsons. Combining floats with wheels, he made the first amphibian flights in February 1911 and was awarded the first Collier Trophy for US flight achievement. From 1912 his experiments resulted in the 1913 Model E and Model F, which he called "flying-boats".

In February 1911, the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

took delivery of the Curtiss Model E, and soon tested landings on and take-offs from ships using the Curtiss Model D.

In Britain, Captain Edward Wakefield and Oscar Gnosspelius

Major Oscar Theodor Gnosspelius (10 March 1878 – 17 February 1953) was an English civil engineer and pioneer seaplane builder.

Gnosspelius was born at Brookfield House, Lydiate on 18 March 1878 the only son of Adolf Jonathan Gnosspelius. He was ...

began to explore the feasibility of flight from water in 1908. They decided to make use of Windermere in the Lake District, England's largest lake. The latter's first attempts to fly attracted large crowds, though the aircraft failed to take off and required a re-design of the floats incorporating features of Borwick's successful speed-boat hulls. Meanwhile, Wakefield ordered a floatplane similar to the design of the 1910 Fabre Hydravion. By November 1911, both Gnosspelius and Wakefield had aircraft capable of flight from water and awaited suitable weather conditions. Gnosspelius's flight was short-lived as the aircraft crashed into the lake. Wakefield's pilot however, taking advantage of a light northerly wind, successfully took off and flew at a height of 50 feet to Ferry Nab, where he made a wide turn and returned for a perfect landing on the lake's surface.

Birth of an industry

In 1913, the '' Daily Mail'' newspaper put up a £10,000 prize for the first non-stop aerial crossing of the Atlantic which was soon "enhanced by a further sum" from the Women's Aerial League of Great Britain. American businessman Rodman Wanamaker became determined that the prize should go to an American aircraft and commissioned the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company to design and build an aircraft capable of making the flight. Curtiss' development of the ''Flying Fish'' flying boat in 1913 brought him into contact with

In 1913, the '' Daily Mail'' newspaper put up a £10,000 prize for the first non-stop aerial crossing of the Atlantic which was soon "enhanced by a further sum" from the Women's Aerial League of Great Britain. American businessman Rodman Wanamaker became determined that the prize should go to an American aircraft and commissioned the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company to design and build an aircraft capable of making the flight. Curtiss' development of the ''Flying Fish'' flying boat in 1913 brought him into contact with John Cyril Porte

Lieutenant Colonel John Cyril Porte, (26 February 1884 – 22 October 1919) was a British flying boat pioneer associated with the First World War Seaplane Experimental Station at Felixstowe.

Early life and career

Porte was born on 26 Februa ...

, a retired Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

lieutenant, aircraft designer and test pilot who was to become an influential British aviation pioneer. Recognising that many of the early accidents were attributable to a poor understanding of handling while in contact with the water, the pair's efforts went into developing practical hull designs to make the transatlantic crossing possible."The Felixstowe Flying Boats", ''Flight'', 2 December 1955.

At the same time the British boat building firm J. Samuel White of Cowes on the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Is ...

set up a new aircraft division and produced a flying boat in the United Kingdom. This was displayed at the London Air Show at Olympia in 1913.Hull 2002, . In that same year, a collaboration between the S. E. Saunders boatyard of East Cowes and the Sopwith Aviation Company produced the "Bat Boat", an aircraft with a consuta laminated hull that could operate from land or on water, which today we call an amphibious aircraft. The "Bat Boat" completed several landings on sea and on land and was duly awarded the Mortimer Singer Prize

Sir Adam Mortimer Singer, KBE, JP (25 July 1863 – 24 June 1929) was an Anglo-American landowner, philanthropist, and sportsman. He was one of the earliest pilots in both France and the United Kingdom.

Childhood and family

Singer was born in ...

. It was the first all-British aeroplane capable of making six return flights over five miles within five hours.

In the U.S. Wanamaker's commission built on Glen Curtiss' previous development and experience with the Model F for the U.S. Navy which rapidly resulted in the ''America'', designed under Porte's supervision following his study and rearrangement of the flight plan; the aircraft was a conventional biplane design with two-bay, unstaggered wings of unequal span with two pusher inline engines mounted side-by-side above the fuselage in the interplane gap. Wingtip pontoons were attached directly below the lower wings near their tips. The design (later developed into the Model H), resembled Curtiss' earlier flying boats, but was built considerably larger so it could carry enough fuel to cover . The three crew members were accommodated in a fully enclosed cabin.

Trials of the ''America'' began on 23 June 1914 with Porte also as Chief Test Pilot; testing soon revealed serious shortcomings in the design; it was under-powered, so the engines were replaced with more powerful engines mounted in a tractor configuration. There was also a tendency for the nose of the aircraft to try to submerge as engine power increased while taxiing on water. This phenomenon had not been encountered before, since Curtiss' earlier designs had not used such powerful engines nor large fuel/cargo loads and so were relatively more buoyant. In order to counteract this effect, Curtiss fitted fins to the sides of the bow to add hydrodynamic lift, but soon replaced these with sponson

Sponsons are projections extending from the sides of land vehicles, aircraft or watercraft to provide protection, stability, storage locations, mounting points for weapons or other devices, or equipment housing.

Watercraft

On watercraft, a spon ...

s, a type of underwater pontoon mounted in pairs on either side of a hull. These sponsons (or their engineering equivalents) and the flared, notched hull would remain a prominent feature of flying boat hull design in the decades to follow. With the problem resolved, preparations for the crossing resumed. While the craft was found to handle "heavily" on takeoff, and required rather longer take-off distances than expected, the full moon

The full moon is the lunar phase when the Moon appears fully illuminated from Earth's perspective. This occurs when Earth is located between the Sun and the Moon (when the ecliptic longitudes of the Sun and Moon differ by 180°). This mea ...

on 5 August 1914 was selected for the trans-Atlantic flight; Porte was to pilot the ''America'' with George Hallett as co-pilot and mechanic.

First World War

Curtiss and Porte's plans were interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War. Porte sailed for England on 4 August 1914 and rejoined the Navy, as a member of the Royal Naval Air Service. Appointed Squadron Commander of Royal Navy Air Station Hendon, he soon convinced the Admiralty of the potential of flying boats and was put in charge of the naval air station atFelixstowe

Felixstowe ( ) is a port town in Suffolk, England. The estimated population in 2017 was 24,521. The Port of Felixstowe is the largest container port in the United Kingdom. Felixstowe is approximately 116km (72 miles) northeast of London.

H ...

in 1915. Porte persuaded the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

to commandeer (and later, purchase) the ''America'' and a sister craft from Curtiss. This was followed by an order for 12 more similar aircraft, one Model H-2 and the remaining as Model H-4's. Four examples of the latter were assembled in the UK by Saunders. All of these were similar to the design of the ''America'' and, indeed, were all referred to as ''America''s in Royal Navy service. The engines, however, were changed from the under-powered 160 hp Curtiss engines to 250 hp Rolls-Royce Falcon engines. The initial batch was followed by an order for 50 more (totalling 64 ''Americas'' overall during the war). Porte also acquired permission to modify and experiment with the Curtiss aircraft.

The Curtiss H-4s were soon found to have a number of problems; they were underpowered, their hulls were too weak for sustained operations and they had poor handling characteristics when afloat or taking off.Bruce ''Flight'' 2 December 1955, p. 844.London 2003, pp. 16–17. One flying boat pilot, Major Theodore Douglas Hallam, wrote that they were "comic machines, weighing well under two tons; with two comic engines giving, when they functioned, 180 horsepower; and comic control, being nose heavy with engines on and tail heavy in a glide."Hallam 1919, pp. 21–22.

At Felixstowe, Porte made advances in flying boat design and developed a practical hull design with the distinctive "Felixstowe notch". Porte's first design to be implemented in Felixstowe was the Felixstowe Porte Baby, a large, three-engined biplane flying-boat, powered by one central pusher and two outboard tractor Rolls-Royce Eagle engines.

Porte modified an H-4 with a new hull whose improved hydrodynamic qualities made taxiing, take-off and landing much more practical, and called it the Felixstowe F.1.

Porte's innovation of the "Felixstowe notch" enabled the craft to overcome suction from the water more quickly and break free for flight much more easily. This made operating the craft far safer and more reliable, although similar devices had been in use in France since 1911. The "notch" breakthrough would soon after evolve into a "step", with the rear section of the lower hull sharply recessed above the forward lower hull section, and that characteristic became a feature of both flying boat hulls and floatplane floats. The resulting aircraft would be large enough to carry sufficient fuel to fly long distances and could berth alongside ships to take on more fuel.

Porte then designed a similar hull for the larger

At Felixstowe, Porte made advances in flying boat design and developed a practical hull design with the distinctive "Felixstowe notch". Porte's first design to be implemented in Felixstowe was the Felixstowe Porte Baby, a large, three-engined biplane flying-boat, powered by one central pusher and two outboard tractor Rolls-Royce Eagle engines.

Porte modified an H-4 with a new hull whose improved hydrodynamic qualities made taxiing, take-off and landing much more practical, and called it the Felixstowe F.1.

Porte's innovation of the "Felixstowe notch" enabled the craft to overcome suction from the water more quickly and break free for flight much more easily. This made operating the craft far safer and more reliable, although similar devices had been in use in France since 1911. The "notch" breakthrough would soon after evolve into a "step", with the rear section of the lower hull sharply recessed above the forward lower hull section, and that characteristic became a feature of both flying boat hulls and floatplane floats. The resulting aircraft would be large enough to carry sufficient fuel to fly long distances and could berth alongside ships to take on more fuel.

Porte then designed a similar hull for the larger Curtiss H-12

The Curtiss Model H was a family of classes of early long-range flying boats, the first two of which were developed directly on commission in the United States in response to the £10,000 prize challenge issued in 1913 by the London newspaper, t ...

flying boat which, while larger and more capable than the H-4s, shared failings of a weak hull and poor water handling. The combination of the new Porte-designed hull, this time fitted with two steps, with the wings of the H-12 and a new tail, and powered by two Rolls-Royce Eagle engines, was named the Felixstowe F.2 and first flew in July 1916,London 2003, pp. 24–25. proving greatly superior to the Curtiss on which it was based. It was used as the basis for all future designs.Bruce ''Flight'' 2 December 1955, p. 846. It entered production as the Felixstowe F.2A, being used as a patrol aircraft, with about 100 being completed by the end of World War I. Another seventy were built, and these were followed by two F.2c, which were built at Felixstowe.

The

The Felixstowe F.5

The Felixstowe F.5 was a British First World War flying boat designed by Lieutenant Commander John Cyril Porte RN of the Seaplane Experimental Station, Felixstowe.

Design and development

Porte designed a better hull for the larger Curtiss H-1 ...

was intended to combine the good qualities of the F.2 and F.3, with the prototype first flying in May 1918. The prototype showed superior qualities to its predecessors but, to ease production, the production version was modified to make extensive use of components from the F.3, which resulted in lower performance than the F.2A or F.3.

The Felixstowe flying boats were extensively employed by the Royal Navy for coastal patrols, including searching for German U-boats. In 1918 they were towed on lighters towards the northern German ports to extend their range; on 4 June 1918 this resulted in three F.2As engaging with ten German seaplanes, shooting down two confirmed and four probables at no loss. As a result of this action, British flying boats were dazzle-painted to aid identification in combat.

The Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company independently developed its designs into the small Model "F", the larger Model "K" (several of which were sold to the Russian Naval Air Service), and the Model "C" for the U.S. Navy. Curtiss among others also built the Felixstowe F.5 as the Curtiss F5L, based on the final Porte hull designs and powered by American Liberty engines.

Meanwhile, the pioneering flying boat designs of François Denhaut had been steadily developed by the Franco-British Aviation Company into a range of practical craft. Smaller than the Felixstowes, several thousand FBAs served with almost all of the Allied forces as reconnaissance craft, patrolling the North Sea, Atlantic and Mediterranean oceans.

In Italy, several flying boats were developed, starting with the L series, and progressing with the M series. The

The Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company independently developed its designs into the small Model "F", the larger Model "K" (several of which were sold to the Russian Naval Air Service), and the Model "C" for the U.S. Navy. Curtiss among others also built the Felixstowe F.5 as the Curtiss F5L, based on the final Porte hull designs and powered by American Liberty engines.

Meanwhile, the pioneering flying boat designs of François Denhaut had been steadily developed by the Franco-British Aviation Company into a range of practical craft. Smaller than the Felixstowes, several thousand FBAs served with almost all of the Allied forces as reconnaissance craft, patrolling the North Sea, Atlantic and Mediterranean oceans.

In Italy, several flying boats were developed, starting with the L series, and progressing with the M series. The Macchi M.5

The Macchi M.5 was an Italian single-seat fighter flying boat designed and built by Nieuport-Macchi at Varese. It was extremely manoeuvrable and agile and matched the land-based aircraft it had to fight.Orbis 1985, page 2393

Development

The ...

in particular was extremely manoeuvrable and agile and matched the land-based aircraft it had to fight. 244 were built in total. Towards the end of the First World War, the aircraft were flown by the Italian Navy Aviation, the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps airmen. Ensign Charles Hammann won the first Medal of Honor awarded to a United States naval aviator in an M.5.

The Aeromarine Plane and Motor Company

The Aeromarine Plane and Motor Company was an early American aircraft manufacturer founded by Inglis M. Upperçu which operated from 1914 to 1930. From 1928 to 1930 it was known as the Aeromarine-Klemm Corporation.

History

The beginnings of the ...

modified the Felixstowe F.5 into Aeromarine 75 airliner flying boats which with Aeromarine West Indies Airways

Aeromarine West Indies Airways was a United States airline that operated from 1920 to 1924. It was reorganized as ''Aeromarine Airways'' in 1921.

A new Aeromarine West Indies Airways was incorporated in 2007.

Original airline

The original co ...

flew Air Mail to Florida, Bahamas, and Cuba along with being passenger carriers.

The German aircraft manufacturing company Hansa-Brandenburg built flying boats starting with the model Hansa-Brandenburg GW in 1916. The Austro-Hungarian firm, Lohner-Werke

Bombardier Transportation Austria GmbH is an Austrian subsidiary company of Bombardier Transportation located in Vienna, Austria.

It was founded in the 19th century by Jacob Lohner as Lohner-Werke or simply ''Lohner'' as a luxury coachbuilding ...

began building flying boats, starting with the Lohner E in 1914 and the later (1915) Lohner L which was copied widely.

Interwar period

In September 1919, British company Supermarine started operating the first flying boat service in the world, from Woolston to Le Havre in

In September 1919, British company Supermarine started operating the first flying boat service in the world, from Woolston to Le Havre in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, but it was short-lived.

A Curtiss NC-4 became the first aircraft to fly across the Atlantic Ocean in 1919, crossing via the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

. Of the four that made the attempt, only one completed the flight. Before the development of highly reliable aircraft, the ability to land on water was a desirable safety feature for transoceanic travel.

In 1923, the first successful commercial flying boat service was introduced with flights to and from the Channel Islands. The British aviation industry was experiencing rapid growth. The Government decided that nationalization was necessary and ordered five aviation companies to merge to form the state-owned Imperial Airways of London (IAL). IAL became the international flag-carrying British airline, providing flying boat passenger and mail transport links between Britain and South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

using aircraft such as the Short S.8 Calcutta.

During the 1920s, the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

(RAF) Far East flight performed a series of "showing the flag" long-distance formation flights using the newly developed Supermarine Southampton. Perhaps the most notable of these flights was a expedition conducted during 1927 and 1928; it was carried out by four Southamptons of the Far East Flight, setting out from Felixstowe via the Mediterranean and India to Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

.Andrews and Morgan 1981, pp. 99–102. Both the RAF and Supermarine acquired considerable acclaim from these flights, as well as proving that flying boats had evolved to become reliable means of long-distance transport.Andrews and Morgan 1981, pp. 100–103.

In the 1930s, flying boats made it possible to have regular air transport between the U.S. and Europe, opening up new air travel routes to South America, Africa, and Asia. Foynes, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

and Botwood, Newfoundland and Labrador were the termini for many early transatlantic flights. In areas where there were no airfields for land-based aircraft, flying boats could stop at small island, river, lake or coastal stations to refuel and resupply. The Pan Am

Pan American World Airways, originally founded as Pan American Airways and commonly known as Pan Am, was an American airline that was the principal and largest international air carrier and unofficial overseas flag carrier of the United State ...

Boeing 314 Clipper

The Boeing 314 Clipper was an American long-range flying boat produced by Boeing from 1938 to 1941. One of the largest aircraft of its time, it had the range to cross the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. For its wing, Boeing re-used the design fro ...

planes brought exotic destinations like the Far East within reach of air travelers and came to represent the romance of flight.

By 1931, mail from Australia was reaching Britain in just 16 days – less than half the time taken by sea. In that year, government tenders on both sides of the world invited applications to run new passenger and mail services between the ends of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

, and Qantas and IAL were successful with a joint bid. A company under combined ownership was then formed, Qantas Empire Airways. The new ten-day service between Rose Bay, New South Wales (near Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mounta ...

) and Southampton was such a success with letter-writers that before long the volume of mail was exceeding aircraft storage space.

A better solution to the problem was sought by the British government during the early 1930s, who released a specification calling for a new large aircraft capable of carrying up to 24 passengers in spacious comfort along with adequate room for airmail or freight while simultaneously being capable of a cruising speed of 170 MPH and a range of at least 700 miles; the capacity for an extended range of 2,000 miles to serve the North Atlantic route was also stipulated.Norris 1966, p. 3. Originally intended for use by IAL, partner Qantas agreed to the initiative and undertook to purchase six of the new Short S23 "C" class or "Empire" flying boats as well. Being ordered from aviation manufacturer Short Brothers

Short Brothers plc, usually referred to as Shorts or Short, is an aerospace company based in Belfast, Northern Ireland. Shorts was founded in 1908 in London, and was the first company in the world to make production aeroplanes. It was particu ...

, the Empire was reportedly hailed as being "one of the world's boldest experiments in aviation", while early sceptics referred to the order less favourably as being a 'gamble'. IAL were so impressed by the Empire that it placed a follow-on order for another 11; when combined with the original order for 28 flying boats, this was the largest single order to have ever been placed for a British civil aircraft at that time.Norris 1966, pp. 10–11.

Delivering the mail as quickly as possible generated a lot of competition and some innovative designs. One variant of the Short Empire flying boats was the strange-looking " Maia and Mercury". It was a four-engined floatplane "Mercury" (the winged messenger) fixed on top of "Maia", a heavily modified Short Empire flying boat. The larger Maia took off, carrying the smaller Mercury loaded to a weight greater than it could take off with. This allowed the Mercury to carry sufficient fuel for a direct trans-Atlantic flight with the mail.Norris 1966, pp. 11–12. Unfortunately this was of limited usefulness, and the Mercury had to be returned from America by ship. The Mercury did set a number of distance records before

Delivering the mail as quickly as possible generated a lot of competition and some innovative designs. One variant of the Short Empire flying boats was the strange-looking " Maia and Mercury". It was a four-engined floatplane "Mercury" (the winged messenger) fixed on top of "Maia", a heavily modified Short Empire flying boat. The larger Maia took off, carrying the smaller Mercury loaded to a weight greater than it could take off with. This allowed the Mercury to carry sufficient fuel for a direct trans-Atlantic flight with the mail.Norris 1966, pp. 11–12. Unfortunately this was of limited usefulness, and the Mercury had to be returned from America by ship. The Mercury did set a number of distance records before in-flight refuelling

Aerial refueling, also referred to as air refueling, in-flight refueling (IFR), air-to-air refueling (AAR), and tanking, is the process of transferring aviation fuel from one aircraft (the tanker) to another (the receiver) while both aircraft a ...

was adopted.Norris 1966, pp. 12–13.

Sir Alan Cobham

Sir Alan John Cobham, KBE, AFC (6 May 1894 – 21 October 1973) was an English aviation pioneer.

Early life and family

As a child he attended Wilson's School, then in Camberwell, London. The school relocated to the former site of Croyd ...

devised a method of in-flight refuelling in the 1930s. In the air, the Short Empire could be loaded with more fuel than it could take off with. Short Empire flying boats serving the trans-Atlantic crossing were refueled over Foynes; with the extra fuel load, they could make a direct trans-Atlantic flight. A Handley Page H.P.54 Harrow

The Handley Page H.P.54 Harrow was a heavy bomber designed and produced by the British aircraft manufacturer Handley Page. It was operated by the Royal Air Force (RAF) and used during the Second World War, although not as a bomber.

The Harrow ...

was used as the fuel tanker.

Dornier Do X

The Dornier Do X was the largest, heaviest, and most powerful flying boat in the world when it was produced by the Dornier company of Germany in 1929. First conceived by Claude Dornier in 1924, planning started in late 1925 and after over 240, ...

flying boat was noticeably different from its UK and U.S.-built counterparts. It had wing-like protrusions from the fuselage, called sponson

Sponsons are projections extending from the sides of land vehicles, aircraft or watercraft to provide protection, stability, storage locations, mounting points for weapons or other devices, or equipment housing.

Watercraft

On watercraft, a spon ...

s, to stabilize it on the water without the need for wing-mounted outboard floats. This feature was pioneered by Claudius Dornier during the First World War on his Dornier Rs. I giant flying boat, and perfected on the Dornier Wal in 1924. The enormous Do X was powered by 12 engines and once carried 170 persons as a publicity stunt. It flew to America in 1930–31, crossing the Atlantic via an indirect route over 9 months. It was the largest flying boat of its time, but was severely underpowered and was limited by a very low operational ceiling. Only three were built, with a variety of different engines installed, in an attempt to overcome the lack of power. Two of these were sold to Italy.

The Dornier Wal was "easily the greatest commercial success in the history of marine aviation". Over 250 were built in Italy, Spain, Japan, The Netherlands and Germany. Numerous airlines operated the Dornier Wal on scheduled passenger and mail services. Wals were used by explorers, for a number of pioneering flights, and by the military in many countries. Though having first flown in 1922, from 1934 to 1938 Wals operated the over-water sectors of the Deutsche Luft Hansa South Atlantic Airmail service.

Second World War

The military value of flying boats was well-recognized, and every country bordering on water operated them in a military capacity at the outbreak of the

The military value of flying boats was well-recognized, and every country bordering on water operated them in a military capacity at the outbreak of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. Flying boats such as the PBM Mariner patrol bomber, PBY Catalina, Short Sunderland, and Grumman Goose were procured in large numbers. The Sunderland, which was developed in parallel to the civilian Empire flying boat, was one of the most powerful and widely used flying boats throughout the conflict,Eden 2004, p. 442.Norris 1967, p. 3. while Catalinas were one of the most produced ASW of the war, with over 2,661 being produced in the US alone.Weathered, William W. "Comment and Discussion". ''United States Naval Institute Proceedings'', October 1968.

Flying boats were commonly utilized to conduct various tasks from anti-submarine

An anti-submarine weapon (ASW) is any one of a number of devices that are intended to act against a submarine and its crew, to destroy (sink) the vessel or reduce its capability as a weapon of war. In its simplest sense, an anti-submarine weapo ...

patrol to air-sea rescue and gunfire spotting for battleships. They would recover downed airmen and operate as scout aircraft over the vast distances of the Pacific Theater and the Atlantic, locating in enemy vessels and sinking numerous submarines. In May 1941, the German battleship ''Bismarck'' was discovered by a PBY Catalina flying out of Castle Archdale Flying boat base, Lower Lough Erne

Lough Erne ( , ) is the name of two connected lakes in County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland. It is the second-biggest lake system in Northern Ireland and Ulster, and the fourth biggest in Ireland. The lakes are widened sections of the River Erne, ...

, Northern Ireland. A flight of Catalinas spotted the Japanese fleet approaching Midway Island

Midway Atoll (colloquial: Midway Islands; haw, Kauihelani, translation=the backbone of heaven; haw, Pihemanu, translation=the loud din of birds, label=none) is a atoll in the North Pacific Ocean. Midway Atoll is an insular area of the Unit ...

, beginning the Battle of Midway.

On 3 April 1940, a single Sunderland operating off Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of ...

was attacked by six German Junkers Ju 88C fighters; during the engagement, it shot one down, damaged another until it retreated and drove off the rest. The Germans reputedly nicknamed the Sunderland the ''Fliegendes Stachelschwein'' ("Flying Porcupine") due to its defensive firepower.Norris 1966, p. 13. Sunderlands in the Mediterranean theatre proved themselves on multiple high-profile occasions, flying many evacuation missions during the German seizure of Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

, each carrying as many as 82 passengers. One Sunderland flew the reconnaissance mission to observe the Italian fleet at anchor in Taranto

Taranto (, also ; ; nap, label=Tarantino, Tarde; Latin: Tarentum; Old Italian: ''Tarento''; Ancient Greek: Τάρᾱς) is a coastal city in Apulia, Southern Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Taranto, serving as an important comme ...

before the famous Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

Fleet Air Arm's torpedo attack on 11 November 1940.Cacutt 1988. .

The largest flying boat of the war was the Blohm & Voss BV 238, which was also the heaviest plane to fly during the Second World War and the largest aircraft built and flown by any of the

The largest flying boat of the war was the Blohm & Voss BV 238, which was also the heaviest plane to fly during the Second World War and the largest aircraft built and flown by any of the Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

. Only the first prototype ever flew, commencing flight trials in April 1944.Green 2010, pp. 165–168. Months later, it was strafed and partially sunk while moored on Lake Schaal, to the east of Hamburg; it never returned to flight, instead being intentionally sunk in deep water after the end of the conflict.

The Imperial Japanese Navy operated what has been often described as the best flying boat of the conflict, the Kawanishi H8K. Its design was based upon its immediate predecessor, the Kawanishi H6K, but was a considerably larger and longer-ranged aircraft designed at the request of the Navy just prior to the outbreak of war. On the night of 4 March 1942, two H8Ks conducted the second raid on Pearl Harbor, refuelling en route by submarine at French Frigate Shoals in order to achieve the necessary range; poor visibility caused this attack on Pearl Harbor to fail to accomplish any significant damage. An improved H8K2 variant of the type, featuring extremely heavy defensive armament, was also introduced.

In November 1939, IAL was restructured into three separate companies: British European Airways, British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC), and

The Imperial Japanese Navy operated what has been often described as the best flying boat of the conflict, the Kawanishi H8K. Its design was based upon its immediate predecessor, the Kawanishi H6K, but was a considerably larger and longer-ranged aircraft designed at the request of the Navy just prior to the outbreak of war. On the night of 4 March 1942, two H8Ks conducted the second raid on Pearl Harbor, refuelling en route by submarine at French Frigate Shoals in order to achieve the necessary range; poor visibility caused this attack on Pearl Harbor to fail to accomplish any significant damage. An improved H8K2 variant of the type, featuring extremely heavy defensive armament, was also introduced.

In November 1939, IAL was restructured into three separate companies: British European Airways, British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC), and British South American Airways

British South American Airways (BSAA) was a state-run airline of the United Kingdom in the mid-late 1940s responsible for services to the Caribbean and South America. Originally named British Latin American Air Lines it was renamed before serv ...

(which merged with BOAC in 1949), with the change being made official on 1 April 1940. BOAC continued to operate flying boat services from the (slightly) safer confines of Poole Harbour

Poole Harbour is a large natural harbour in Dorset, southern England, with the town of Poole on its shores. The harbour is a drowned valley ( ria) formed at the end of the last ice age and is the estuary of several rivers, the largest bei ...

during wartime, returning to Southampton in 1947. When Italy entered the war in June 1940, the Mediterranean was closed to allied planes and BOAC and Qantas operated the Horseshoe Route between Durban and Sydney using Short Empire flying boats.

The Martin Company produced the prototype XPB2M Mars based on their PBM Mariner patrol bomber, with flight tests between 1941 and 1943. The Mars was converted by the Navy into a transport aircraft designated the XPB2M-1R. Satisfied with the performance, 20 of the modified JRM-1 Mars were ordered. The first of the five production Mars flying boats entered service ferrying cargo to Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

and the Pacific Islands on 23 January 1944. Following the end of the conflict, the Navy opted to scaled back their order, buying only the five aircraft. The five Mars were completed, and the last delivered in 1947.Goebel, Greg"The Martin Mariner, Mars, & Marlin Flying Boats."

''Vectorsite.'' Retrieved: 20 May 2012.

Post-War

After the end of the Second World War, the use of flying boats rapidly declined for several reasons. The ability to land on water became less of an advantage owing to the considerable increase in the number and length of land based runways during the conflict. Furthermore the commercial competitiveness of flying boats diminished, as their design compromised aerodynamic efficiency and speed in order to accommodate waterborne takeoff and landing. New land-based airliners such as the Lockheed Constellation and Douglas DC-4 were developed with comparable reliability, speed, and long-range. The new landplanes were relatively easy to fly, and did not require the extensive pilot training programs mandated for seaplane operations. One of the 314's most experienced pilots said, "We were indeed glad to change to DC-4s, and I argued daily for eliminating all flying boats. The landplanes were much safer. No one in the operations department... had any idea of the hazards of flying boat operations. The main problem now was lack of the very high level of experience and competence required of seaplane pilots".

The

After the end of the Second World War, the use of flying boats rapidly declined for several reasons. The ability to land on water became less of an advantage owing to the considerable increase in the number and length of land based runways during the conflict. Furthermore the commercial competitiveness of flying boats diminished, as their design compromised aerodynamic efficiency and speed in order to accommodate waterborne takeoff and landing. New land-based airliners such as the Lockheed Constellation and Douglas DC-4 were developed with comparable reliability, speed, and long-range. The new landplanes were relatively easy to fly, and did not require the extensive pilot training programs mandated for seaplane operations. One of the 314's most experienced pilots said, "We were indeed glad to change to DC-4s, and I argued daily for eliminating all flying boats. The landplanes were much safer. No one in the operations department... had any idea of the hazards of flying boat operations. The main problem now was lack of the very high level of experience and competence required of seaplane pilots".

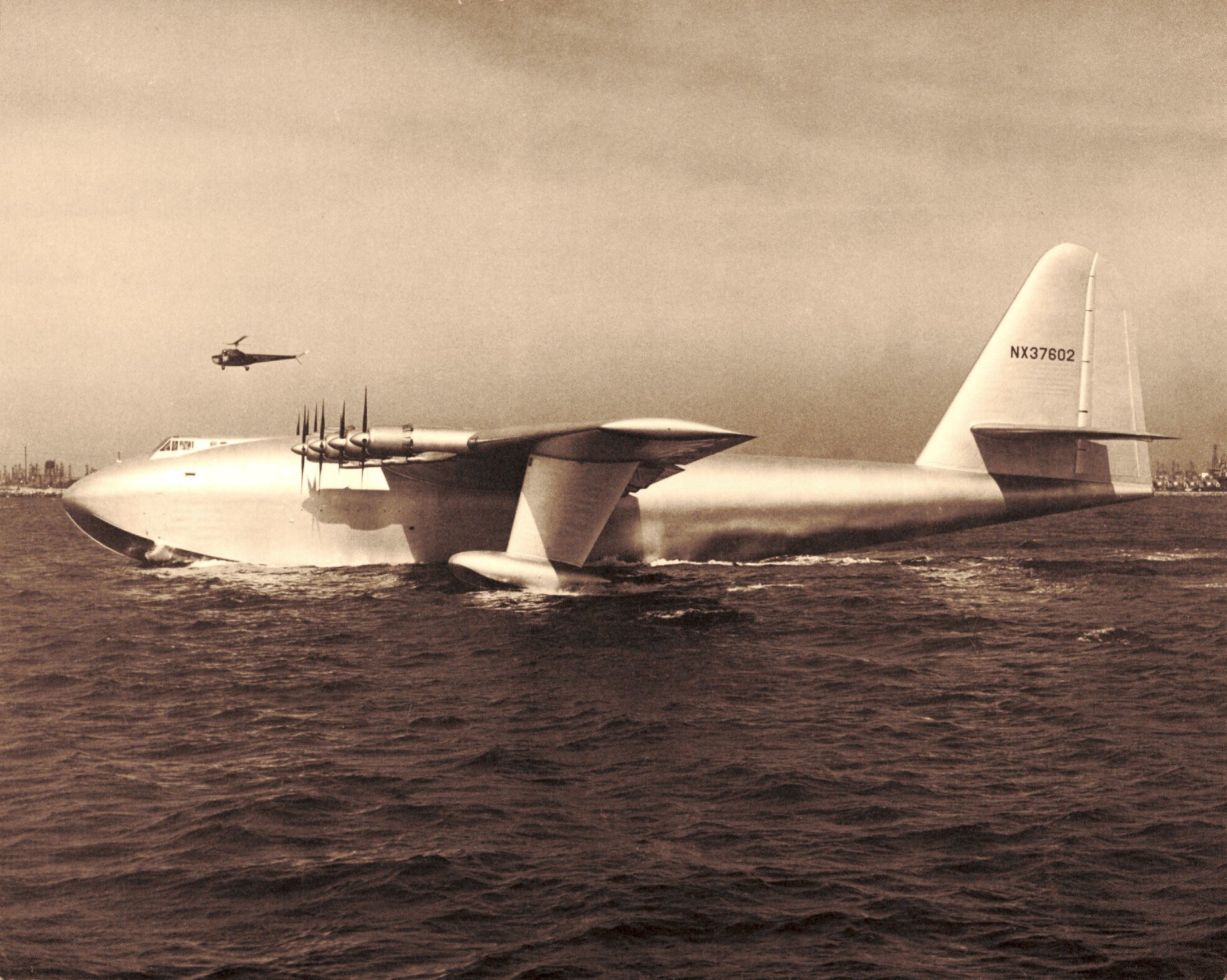

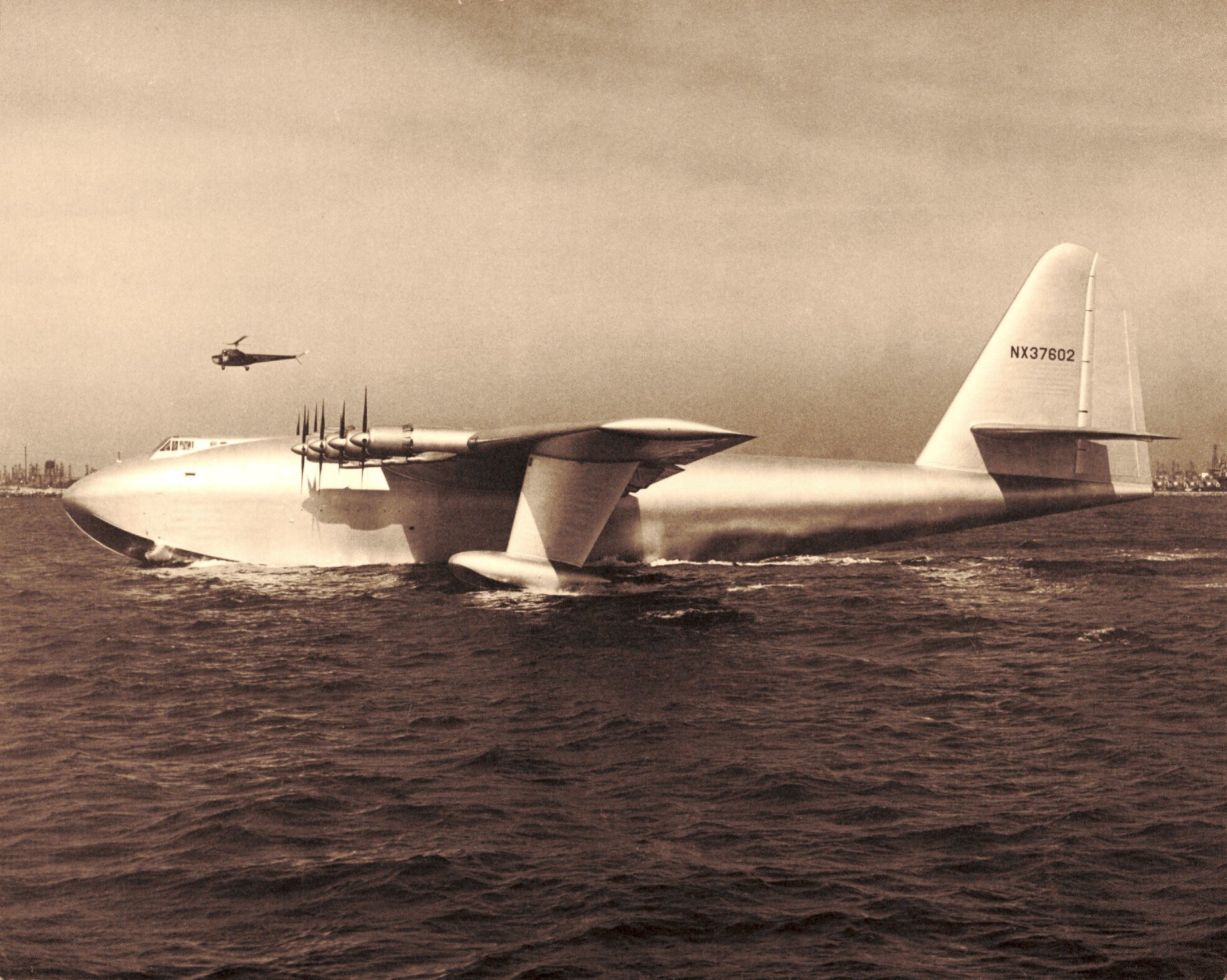

The Hughes H-4 Hercules

The Hughes H-4 Hercules (commonly known as the ''Spruce Goose''; registration NX37602) is a prototype strategic airlift flying boat designed and built by the Hughes Aircraft Company. Intended as a transatlantic flight transport for use durin ...

, in development in the U.S. during the war, was even larger than the BV 238 but it did not fly until 1947. The ''Spruce Goose'', as the 180-ton H-4 was nicknamed, was the largest flying boat ever to fly. Carried out during Senate hearings into Hughes use of government funds on its construction, the short hop of about a mile at 70 ft above the water by the "Flying Lumberyard" was claimed by Hughes as the H-4's vindication. Cutbacks in expenditure after the war and the disappearance of its intended mission as a transatlantic transport left the H-4 with no purpose. Despite never flying again, a full-time crew of 300 workers maintained the H-4 in a flightworthy condition in a climate-controlled hangar up until Hughes' death in 1976.Dietrich and Thomas 1972, pp. 209–216.

In early 1944, the British Air Ministry issued a contract for the production of a small jet-powered

Jet propulsion is the propulsion of an object in one direction, produced by ejecting a jet of fluid in the opposite direction. By Newton's third law, the moving body is propelled in the opposite direction to the jet. Reaction engines operating on ...

flying boat, the Saunders-Roe SR.A/1, that was intended for use as an air defence aircraft optimised for use in the Pacific theatre.Buttler 2004, pp. 206–207. By adopting jet propulsion for the flying boat, it was possible to design it with a hull, rather than making it a floatplane, and thus eliminating the performance handicaps typically imposed upon floatplanes. It was projected to be capable of attaining speeds of up to 520 mph at 40,000 ft. Due to the SR.A/1's perceived value in the war against Imperial Japan, measures taken at an early stage of development towards immediate quantity production.King 14 December 1950, p. 555. However, due to the end of the conflict, pressure for the SR.A/1 quickly dissipated.

On 16 July 1947, the SR.A/1 prototype performed its maiden flight, quickly proving its soundness in terms of its performance and handling.London 2003, p. 233. However, officials judged that such an aircraft was unnecessary, and that the aircraft carrier had demonstrated a far more effective way to project airpower over the oceans.King 14 December 1950, p. 553. During late 1950, shortly after the outbreak of the Korean War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Korean War

, partof = the Cold War and the Korean conflict

, image = Korean War Montage 2.png

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Clockwise from top:{ ...

, interest in the SR.A/1 programme was briefly resurrected amongst British and American officials, with whom data had been shared in the project. However, the flying boat fighter was found to be obsolete in comparison to increasingly capable land-based fighters, leading to a second and final cancellation.London 2003, pp. 235–237.

During the Berlin Airlift

The Berlin Blockade (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949) was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway, ro ...

(which lasted from June 1948 until August 1949) ten Sunderlands and two Hythe

Hythe, from Anglo-Saxon ''hȳð'', may refer to a landing-place, port or haven, either as an element in a toponym, such as Rotherhithe in London, or to:

Places Australia

* Hythe, Tasmania

Canada

*Hythe, Alberta, a village in Canada

England

* ...

s were used to transport goods from Finkenwerder on the Elbe near Hamburg to isolated Berlin, landing on the Havelsee beside RAF Gatow

Royal Air Force Gatow, or more commonly RAF Gatow, was a British Royal Air Force station (military airbase) in the district of Gatow in south-western Berlin, west of the Havel river, in the borough of Spandau. It was the home for the onl ...

until it iced over.Norris 1967, p. 14. The Sunderlands were particularly used for transporting salt, as their airframes were already protected against corrosion from seawater. Transporting salt in standard aircraft risked rapid and severe structural corrosion in the event of a spillage. In addition, three Aquila Airways flying boats were used during the airlift.

Bucking the trend, in 1948 Aquila Airways was founded to serve destinations that were still inaccessible to land-based aircraft. This company operated Short S.25 and Short S.45 flying boats out of Southampton on routes to Madeira, Las Palmas, Lisbon, Jersey

Jersey ( , ; nrf, Jèrri, label= Jèrriais ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey (french: Bailliage de Jersey, links=no; Jèrriais: ), is an island country and self-governing Crown Dependency near the coast of north-west France. It is the ...

, Majorca, Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fra ...

, Capri, Genoa, Montreux and Santa Margherita. From 1950 to 1957, Aquila also operated a service from Southampton to Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

and Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popu ...

. The flying boats of Aquila Airways were also chartered for one-off trips, usually to deploy troops where scheduled services did not exist or where there were political considerations. The longest charter, in 1952, was from Southampton to the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouze ...

. In 1953, the flying boats were chartered for troop deployment trips to Freetown and Lagos

Lagos (Nigerian English: ; ) is the largest city in Nigeria and the second most populous city in Africa, with a population of 15.4 million as of 2015 within the city proper. Lagos was the national capital of Nigeria until December 1991 fo ...

and there was a special trip from Hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* Chassis, of an armored fighting vehicle

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a ship

* Submarine hull

Mathematics

* Affine hull, in affi ...

to Helsinki to relocate a ship's crew. The airline ceased operations on 30 September 1958.

On 22 August 1952, the

On 22 August 1952, the Saunders-Roe Princess

The Saunders-Roe SR.45 Princess was a British flying boat aircraft developed and built by Saunders-Roe at their Cowes facility on the Isle of Wight. It has the distinction of being the largest all-metal flying boat to have ever been constructed.

...

, one of the largest and luxurious flying boats ever developed, performed its maiden flight.Kaplan 2005, p. 205. While flight testing of the innovative and ambitious flying boat went relatively smoothly, determining that the Princess was indeed capable of achieving its envisioned performance figures, only one prototype of the type would ever fly. Despite the granting of a certificate of airworthiness and representing the pinnacle of flying boat development of the era, no customers were willing to place firm orders for the Princess. This is despite reports that several would-be operators, including Aquila Airways and Aero Spacelines

Aero Spacelines, Inc. was an American aircraft manufacturer from 1960 to 1968 that converted Boeing 377 Stratocruisers into the famous Guppy line of airplanes, re-engineered to transport oversized cargo such as space exploration vehicles.

...

, had attempted to purchase examples.

In 1951, BOAC performed an in-depth reevaluation of its standing requirements, and determined that the airline had no present need for the Princess, or any new large flying boat. The airline had already chosen to terminate its existing flying boat services during the previous year. Up until 1974, Ansett Australia operated a flying boat service from Rose Bay to Lord Howe Island

Lord Howe Island (; formerly Lord Howe's Island) is an irregularly crescent-shaped volcanic remnant in the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand, part of the Australian state of New South Wales. It lies directly east of mainland Po ...

using Short Sandringhams.

The US Navy continued to operate flying boats (notably the Martin P5M Marlin) until the late 1960s. During the 1950s, the US Navy had encouraged the development of a jet-powered flying boat bomber, the Martin P6M Seamaster; however, its development was protracted by unfavourable handling characteristics above Mach 0.8, including rapid changes in directional trim, severe buffeting

Aeroelasticity is the branch of physics and engineering studying the interactions between the inertial, elastic, and aerodynamic forces occurring while an elastic body is exposed to a fluid flow. The study of aeroelasticity may be broadly classif ...

, and wing drop, which made it unfeasible for service until these tendencies were rectified. Following the US Navy's withdrawal of support, Martin tried unsuccessfully to market the SeaMaster to the civilian market, rebranding it as the ''SeaMistress'', but the initiative picked up no takers.

During the 1950s, the Japanese aircraft manufacturer ShinMeiwa Industries conducted internal design studies into developing flying boats that would exhibit greater levels of seaworthiness than their predecessors. Over the following decade, the company developed the Shin Meiwa US-1A

The Shin Meiwa PS-1 and US-1A is a large STOL aircraft designed for anti-submarine warfare (ASW) and air-sea rescue (SAR) work respectively by Japanese aircraft manufacturer Shin Meiwa. The PS-1 anti-submarine warfare (ASW) variant is a flying ...

, a new generation flying boat, to meet Japan's requirement for a maritime patrol aircraft capable of ASW operations. The initial model, designated ''PS-1'', was quickly followed by a dedicated search-and-rescue (SAR) variant, the ''US-1'', although this was technically an amphibian rather than a flying boat through its modified designs.Simpson, James"Japan's defense industry is super excited about this amphibious plane."

''The Week'', 10 September 2015. Shin Meiwa developed further flying boat concepts around this period, including the ''Shin Meiwa MS'' (Medium Seaplane) a 300-passenger long-range flying boat with its own beaching gear; and the gargantuan ''Shin Meiwa GS'' (Giant Seaplane) with a capacity of 1200 passengers seated on three decks.

Twenty-first century developments

The shape of the Short Empire, a British flying boat of the 1930s was a harbinger of the shape of 20th century aircraft yet to come. Today, however, true flying boats have largely been replaced by floatplanes or amphibious aircraft with wheels. The Beriev Be-200 twin-jet amphibious aircraft is used for fighting forest fires. There are also several experimental/kit amphibians such as the Volmer Sportsman, Quikkit Glass Goose, Airmax Sea Max, Aeroprakt A-24, and Seawind 300C. The ShinMaywa US-2 is a largeSTOL

A short takeoff and landing (STOL) aircraft is a conventional fixed-wing aircraft that has short runway requirements for takeoff and landing. Many STOL-designed aircraft also feature various arrangements for use on airstrips with harsh condi ...

amphibious aircraft designed for air-sea rescue work, derived from the earlier US-1. The first example was delivered to the Japan Maritime Self Defense Force in 2009; the service has replaced its US-1 fleet with the US-2. A civilian-orientated fire-fighting variant of the US-2 has also been designed and promoted to prospective customers.

The Canadair CL-415

The Canadair CL-415 (Super Scooper, later Bombardier 415) and the De Havilland Canada DHC-515 are a series of amphibious aircraft built originally by Canadair and subsequently by Bombardier and Viking Air, and De Havilland Canada. The CL-415 ...

, an improved model of the Canadair CL-215

The Canadair CL-215 (Scooper) is the first model in a series of flying boat amphibious aircraft designed and built by Canadian aircraft manufacturer Canadair, and later produced by Bombardier. It is one of only a handful of large amphibious a ...

, remains in production during the twenty-first century. The type has been primarily used for forest fire suppression, but has also seen use in other capacities, such as a maritime patrol aircraft.

The German company Dornier Seawings, an off-shoot of the original Dornier company, has repeatedly announced plans to launch production of its SeaStar composite flying boat. In February 2016, Dornier launched the improved CD2 SeaStar.

During the 2010s, the state-owned company Aviation Industry Corporation of China

Aviation includes the activities surrounding mechanical flight and the aircraft industry. ''Aircraft'' includes fixed-wing and rotary-wing types, morphable wings, wing-less lifting bodies, as well as lighter-than-air craft such as hot air ...

(AVIC) launched a program to develop a massive new amphibian, the AVIC AG600

The AVIC AG600 Kunlong () is a large amphibious aircraft designed by AVIC and assembled by CAIGA.

Powered by four WJ-6 turboprops, it is one of the largest flying boats with a MTOW.

After five years of development, assembly started in Au ...

. On 24 December 2017, it made its maiden flight from Zhuhai Jinwan Airport

Zhuhai Jinwan Airport , also called Zhuhai Sanzao Airport () before January 10, 2013, is the airport serving the city of Zhuhai in Guangdong province, China. It is located some (road distance) southwest of the Zhuhai city center in Sanzao To ...

. Target markets for the AVIC AG600 includes export sales, with countries such as New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

and Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federal constitutional monarchy consists of thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two regions: Peninsular Malaysia and Borneo's East Mal ...

having expressed interest.

The ICON A5 is an amphibious aircraft in the light-sport class.

The Progressive Aerodyne Searey is an amphibious aircraft in the light-sport class, available as a kit built experimental or factory built aircraft

See also

* Ground effect vehicle * List of flying boats and floatplanes * Maritime patrol aircraftReferences

Citations

Bibliography

* Amtmann, Hans. ''The Vanishing Paperclips.'' Monogram, 1988. * Andrews, C.F. and E.B. Morgan. ''Supermarine Aircraft Since 1914''. London: Putnam, 1981. . * * * Cacutt, Len. "The World's Greatest Aircraft," Exeter Books, New York, NY, 1988. . * Davies, R.E.G. ''Pan Am: An Airline and its Aircraft''. New York: Orion Books, 1987. . * * Eden, Paul, ed. ''The Encyclopedia of Aircraft of WW II''. Leicester, UK: Silverdale Books/Bookmart Ltd, 2004. . * (new edition 1987 by Putnam Aeronautical Books, .) * Francillon, René J. ''McDonnell Douglas Aircraft since 1920: Volume II''. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1990. . * * * Hull, Norman. ''Flying Boats of the Solent: A Portrait of a Golden Age of Air Travel'' (Aviation Heritage). Great Addington, Kettering, Northants, UK: Silver Link Publishing, 2002. . * Kaplan, Philip"Big Wings: The Largest Aeroplanes Ever Built."