Evolution of human intelligence on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The evolution of human intelligence is closely tied to the evolution of the

Around 10 million years ago, the Earth's climate entered a cooler and drier phase, which led eventually to the

Around 10 million years ago, the Earth's climate entered a cooler and drier phase, which led eventually to the

ImageSize = width:450 height:125

PlotArea = left:40 right:25 bottom:20 top:5

AlignBars = justify

Colors =

id:green value:rgb(0.996,0.945,0.878)

id:nil value:gray(0.9)

id:era value:rgb(0.996,0.941,0.8)

id:age value:rgb(0.996,0.937,0.756)

id:period1 value:rgb(0.996,0.945,0.839)

id:period3 value:gray(0.8) # background bar

Period = from:-2000000 till:2013

TimeAxis = orientation:horizontal

ScaleMajor = unit:year increment:250000 start:-2000000

ScaleMinor = unit:year increment:20000 start:-2000000

PlotData=

align:center textcolor:black fontsize:8 mark:(line,black) width:5 shift:(0,-5)

bar: from:-2000000 till:end width:35 color:period3

bar: from:-2000000 till:end width:15 color:white

bar: at:-2000000 color:period3 shift:(-20,7) text:

::Dates approximate, consult articles for details

::(''From 2,000,000 BC to 2013 AD in (partial) exponential notation'')

::''See also'':

The

The

human brain

The human brain is the central organ of the human nervous system, and with the spinal cord makes up the central nervous system. The brain consists of the cerebrum, the brainstem and the cerebellum. It controls most of the activities of ...

and to the origin of language

The origin of language (spoken and signed, as well as language-related technological systems such as writing), its relationship with human evolution, and its consequences have been subjects of study for centuries. Scholars wishing to study th ...

. The timeline of human evolution spans approximately seven million years, from the separation of the genus '' Pan'' until the emergence of behavioral modernity

Behavioral modernity is a suite of behavioral and cognitive traits that distinguishes current '' Homo sapiens'' from other anatomically modern humans, hominins, and primates. Most scholars agree that modern human behavior can be characterize ...

by 50,000 years ago. The first three million years of this timeline concern ''Sahelanthropus

''Sahelanthropus tchadensis'' is an extinct species of the Homininae (African apes) dated to about , during the Miocene epoch. The species, and its genus ''Sahelanthropus'', was announced in 2002, based mainly on a partial cranium, nicknamed '' ...

'', the following two million concern ''Australopithecus

''Australopithecus'' (, ; ) is a genus of early hominins that existed in Africa during the Late Pliocene and Early Pleistocene. The genus ''Homo'' (which includes modern humans) emerged within ''Australopithecus'', as sister to e.g. ''Australo ...

'' and the final two million span the history of the genus ''Homo

''Homo'' () is the genus that emerged in the (otherwise extinct) genus '' Australopithecus'' that encompasses the extant species ''Homo sapiens'' ( modern humans), plus several extinct species classified as either ancestral to or closely rela ...

'' in the Paleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός '' palaios'', "old" and λίθος ''lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone too ...

era.

Many traits of human intelligence, such as empathy

Empathy is the capacity to understand or feel what another person is experiencing from within their frame of reference, that is, the capacity to place oneself in another's position. Definitions of empathy encompass a broad range of social, co ...

, theory of mind

In psychology, theory of mind refers to the capacity to understand other people by ascribing mental states to them (that is, surmising what is happening in their mind). This includes the knowledge that others' mental states may be different fro ...

, mourning

Mourning is the expression of an experience that is the consequence of an event in life involving loss, causing grief, occurring as a result of someone's death, specifically someone who was loved although loss from death is not exclusively ...

, ritual

A ritual is a sequence of activities involving gestures, words, actions, or objects, performed according to a set sequence. Rituals may be prescribed by the traditions of a community, including a religious community. Rituals are characterized ...

, and the use of symbol

A symbol is a mark, sign, or word that indicates, signifies, or is understood as representing an idea, object, or relationship. Symbols allow people to go beyond what is known or seen by creating linkages between otherwise very different conc ...

s and tool

A tool is an object that can extend an individual's ability to modify features of the surrounding environment or help them accomplish a particular task. Although many animals use simple tools, only human beings, whose use of stone tools dates b ...

s, are somewhat apparent in great ape

The Hominidae (), whose members are known as the great apes or hominids (), are a taxonomic family of primates that includes eight extant species in four genera: '' Pongo'' (the Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli orangutan); ''Gorilla'' (the ...

s, although they are in much less sophisticated forms than what is found in humans like the great ape language

Research into great ape language has involved teaching chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas and orangutans to communicate with humans and with each other using sign language, physical tokens, lexigrams, and mimicking human speech. Some primatologists ...

.

History

Hominidae

Thegreat ape

The Hominidae (), whose members are known as the great apes or hominids (), are a taxonomic family of primates that includes eight extant species in four genera: '' Pongo'' (the Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli orangutan); ''Gorilla'' (the ...

s (hominidae) show some cognitive

Cognition refers to "the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses". It encompasses all aspects of intellectual functions and processes such as: perception, attention, thought ...

and empathic

Empathy is the capacity to understand or feel what another person is experiencing from within their frame of reference, that is, the capacity to place oneself in another's position. Definitions of empathy encompass a broad range of social, cog ...

abilities. Chimpanzee

The chimpanzee (''Pan troglodytes''), also known as simply the chimp, is a species of great ape native to the forest and savannah of tropical Africa. It has four confirmed subspecies and a fifth proposed subspecies. When its close relative t ...

s can make tool

A tool is an object that can extend an individual's ability to modify features of the surrounding environment or help them accomplish a particular task. Although many animals use simple tools, only human beings, whose use of stone tools dates b ...

s and use them to acquire foods and for social display

Display behaviour is a set of ritualized behaviours that enable an animal to communicate to other animals (typically of the same species) about specific stimuli. These ritualized behaviours can be visual however many animals depend on a mixture ...

s; they have mildly complex hunting

Hunting is the human activity, human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, or killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to harvest food (i.e. meat) and useful animal products (fur/hide (skin), hide, ...

strategies requiring cooperation, influence and rank; they are status conscious, manipulative and capable of deception

Deception or falsehood is an act or statement that misleads, hides the truth, or promotes a belief, concept, or idea that is not true. It is often done for personal gain or advantage. Deception can involve dissimulation, propaganda and sleight o ...

; they can learn to use symbol

A symbol is a mark, sign, or word that indicates, signifies, or is understood as representing an idea, object, or relationship. Symbols allow people to go beyond what is known or seen by creating linkages between otherwise very different conc ...

s and understand aspects of human language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of ...

including some relational syntax

In linguistics, syntax () is the study of how words and morphemes combine to form larger units such as phrases and sentences. Central concerns of syntax include word order, grammatical relations, hierarchical sentence structure ( constituenc ...

, concepts of number

A number is a mathematical object used to count, measure, and label. The original examples are the natural numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, and so forth. Numbers can be represented in language with number words. More universally, individual number ...

and numerical sequence. One common characteristic that is present in species of "high degree intelligence" (i.e. dolphins, great apes, and humans - ''Homo sapiens'') is a brain of enlarged size. Along with this, there is a more developed neocortex, a folding of the cerebral cortex, and von Economo neurons. Said neurons are linked to social intelligence and the ability to gauge what another is thinking or feeling and are also present in bottlenose dolphins.

Homininae

Around 10 million years ago, the Earth's climate entered a cooler and drier phase, which led eventually to the

Around 10 million years ago, the Earth's climate entered a cooler and drier phase, which led eventually to the Quaternary glaciation

The Quaternary glaciation, also known as the Pleistocene glaciation, is an alternating series of glacial and interglacial periods during the Quaternary period that began 2.58 Ma (million years ago) and is ongoing. Although geologists describ ...

beginning some 2.6 million years ago. One consequence of this was that the north African tropical forest

Tropical forests (a.k.a. jungle) are forested landscapes in tropical regions: ''i.e.'' land areas approximately bounded by the tropic of Cancer and Capricorn, but possibly affected by other factors such as prevailing winds.

Some tropical fore ...

began to retreat, being replaced first by open grasslands

A grassland is an area where the vegetation is dominated by grasses ( Poaceae). However, sedge (Cyperaceae) and rush ( Juncaceae) can also be found along with variable proportions of legumes, like clover, and other herbs. Grasslands occur nat ...

and eventually by desert

A desert is a barren area of landscape where little precipitation occurs and, consequently, living conditions are hostile for plant and animal life. The lack of vegetation exposes the unprotected surface of the ground to denudation. About on ...

(the modern Sahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

). As their environment changed from continuous forest to patches of forest separated by expanses of grassland, some primates adapted to a partly or fully ground-dwelling life. Here they were exposed to predator

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill t ...

s, such as the big cats

The term "big cat" is typically used to refer to any of the five living members of the genus ''Panthera'', namely the tiger, lion, jaguar, leopard, and snow leopard.

Despite enormous differences in size, various cat species are quite similar ...

, from whom they had previously been safe.

These environmental pressures caused selection to favor bipedalism

Bipedalism is a form of terrestrial locomotion where an organism moves by means of its two rear limbs or legs. An animal or machine that usually moves in a bipedal manner is known as a biped , meaning 'two feet' (from Latin ''bis'' 'double' ...

: walking on hind legs. This gave the Homininae's eyes greater elevation, the ability to see approaching danger further off, and a more efficient means of locomotion. It also freed the arms from the task of walking and made the hands available for tasks such as gathering food. At some point the bipedal primate

Primates are a diverse order of mammals. They are divided into the strepsirrhines, which include the lemurs, galagos, and lorisids, and the haplorhines, which include the tarsiers and the simians ( monkeys and apes, the latter includin ...

s developed handedness

In human biology, handedness is an individual's preferential use of one hand, known as the dominant hand, due to it being stronger, faster or more dextrous. The other hand, comparatively often the weaker, less dextrous or simply less subject ...

, giving them the ability to pick up sticks, bone

A bone is a rigid organ that constitutes part of the skeleton in most vertebrate animals. Bones protect the various other organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells, store minerals, provide structure and support for the body, ...

s and stones and use them as weapon

A weapon, arm or armament is any implement or device that can be used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime, law enforcement, s ...

s, or as tool

A tool is an object that can extend an individual's ability to modify features of the surrounding environment or help them accomplish a particular task. Although many animals use simple tools, only human beings, whose use of stone tools dates b ...

s for tasks such as killing smaller animals, cracking nuts, or cutting up carcasses. In other words, these primates developed the use of primitive technology

Technology is the application of knowledge to reach practical goals in a specifiable and reproducible way. The word ''technology'' may also mean the product of such an endeavor. The use of technology is widely prevalent in medicine, scien ...

. Bipedal tool-using primates from the subtribe Hominina

Australopithecina or Hominina is a subtribe in the tribe Hominini. The members of the subtribe are generally ''Australopithecus'' (cladistically including the genera ''Homo'', ''Paranthropus'', and ''Kenyanthropus''), and it typically includes ...

date back to as far as about 5 to 7 million years ago, such as one of the earliest species, ''Sahelanthropus tchadensis

''Sahelanthropus tchadensis'' is an extinct species of the Homininae (African apes) dated to about , during the Miocene epoch. The species, and its genus ''Sahelanthropus'', was announced in 2002, based mainly on a partial cranium, nicknamed ''T ...

''.

From about 5 million years ago, the hominin brain began to develop rapidly in both size and differentiation of function.

There has been a gradual increase in brain volume as humans progressed along the timeline of evolution (see Homininae

Homininae (), also called "African hominids" or "African apes", is a subfamily of Hominidae. It includes two tribes, with their extant as well as extinct species: 1) the tribe Hominini (with the genus ''Homo'' including modern humans and numerou ...

), starting from about 600 cm3 in ''Homo habilis

''Homo habilis'' ("handy man") is an extinct species of archaic human from the Early Pleistocene of East and South Africa about 2.31 million years ago to 1.65 million years ago (mya). Upon species description in 1964, ''H. habilis'' was highly ...

'' up to 1500 cm3 in ''Homo neanderthalensis

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. While the ...

''. Thus, in general there's a correlation between brain volume and intelligence. However, modern ''Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture ...

'' have a brain volume slightly smaller (1250 cm3) than neanderthals, and the Flores hominids (''Homo floresiensis

''Homo floresiensis'' also known as "Flores Man"; nicknamed "Hobbit") is an extinct species of small archaic human that inhabited the island of Flores, Indonesia, until the arrival of modern humans about 50,000 years ago.

The remains of an in ...

''), nicknamed hobbits, had a cranial capacity of about 380 cm3 (considered small for a chimpanzee) about a third of that of ''Homo erectus

''Homo erectus'' (; meaning "upright man") is an extinct species of archaic human from the Pleistocene, with its earliest occurrence about 2 million years ago. Several human species, such as '' H. heidelbergensis'' and '' H. antecessor ...

''. It is proposed that they evolved from ''H. erectus'' as a case of insular dwarfism. With their three times smaller brain the Flores hominids apparently used fire and made tools as sophisticated as those of their ancestor ''H. erectus''.

''Homo''

Roughly 2.4 million years ago ''Homo habilis

''Homo habilis'' ("handy man") is an extinct species of archaic human from the Early Pleistocene of East and South Africa about 2.31 million years ago to 1.65 million years ago (mya). Upon species description in 1964, ''H. habilis'' was highly ...

'' had appeared in East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territories make up Eastern Africa:

Due to the historica ...

: the first known human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, cultu ...

species, and the first known to make stone tool

A stone tool is, in the most general sense, any tool made either partially or entirely out of stone. Although stone tool-dependent societies and cultures still exist today, most stone tools are associated with prehistoric (particularly Stone A ...

s, yet the disputed findings of signs of tool use from even earlier ages and from the same vicinity as multiple ''Australopithecus

''Australopithecus'' (, ; ) is a genus of early hominins that existed in Africa during the Late Pliocene and Early Pleistocene. The genus ''Homo'' (which includes modern humans) emerged within ''Australopithecus'', as sister to e.g. ''Australo ...

'' fossils may put to question how much more intelligent than its predecessors ''H. habilis'' was.

The use of tools conferred a crucial evolutionary advantage, and required a larger and more sophisticated brain to co-ordinate the fine hand movements required for this task. Our knowledge of the complexity of behaviour of ''Homo habilis'' is not limited to stone culture, they also had habitual therapeutic use of toothpicks.

A larger brain requires a larger skull

The skull is a bone protective cavity for the brain. The skull is composed of four types of bone i.e., cranial bones, facial bones, ear ossicles and hyoid bone. However two parts are more prominent: the cranium and the mandible. In humans, th ...

, and thus is accompanied by other morphological and biological evolutionary changes. One such change required for the female

Female ( symbol: ♀) is the sex of an organism that produces the large non-motile ova (egg cells), the type of gamete (sex cell) that fuses with the male gamete during sexual reproduction.

A female has larger gametes than a male. Fema ...

to have a wider birth canal

In mammals, the vagina is the elastic, muscular part of the female genital tract. In humans, it extends from the Vulval vestibule, vestibule to the cervix. The outer vaginal opening is normally partly covered by a thin layer of mucous membrane ...

for the newborn's larger skull to pass through. The solution to this was to give birth at an early stage of fetal development, before the skull grew too large to pass through the birth canal. Other accompanying adaptations were the smaller maxillary and mandibular bones, smaller and weaker facial muscles, and shortening and flattening of the face resulting in modern-human's complex cognitive and linguistic capabilities as well as the ability to create facial expressions and smile. Consequentially, dental issues in modern humans arise from these morphological changes that are exacerbated by a shift from nomadic to sedentary lifestyles.

This adaptation enabled the human brain to continue to grow, but it imposed a new discipline

Discipline refers to rule following behavior, to regulate, order, control and authority. It may also refer to punishment. Discipline is used to create habits, routines, and automatic mechanisms such as blind obedience. It may be inflicted on ot ...

. It is to be noted that traditional claims about men's and women's gender roles have been challenged in the past years. Regardless, humans' increasingly sedentary lifestyle to protect their more vulnerable offspring led them to grow even more dependent on tool-making to compete with other animals and other humans, and rely less on body size and strength.

About 200,000 years ago Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

and the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

were colonized by Neanderthal man, extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

by 39,000 years ago following the appearance of modern humans in the region from 40,000 to 45,000 years ago.

History of humans

In the Late Pliocene, hominins were set apart from modern great apes and other closely-related organisms by the anatomical evolutionary changes resulting in bipedalism, or the ability to walk upright. Characteristics such as a supraorbital torus, or prominent eyebrow ridge, and flat face also makes ''Homo erectus'' distinguishable. Their brain size substantially sets them apart from closely related species, such as ''H. habilis'', as we can see an increase in average cranial capacity of 1000 cc. Compared to earlier species, ''H. erectus'' developed keels and small crests in the skull showing morphological changes of the skull to support increased brain capacity. It is believed that ''Homo erectus'' were, anatomically, modern humans as they are very similar in size, weight, bone structure, and nutritional habits. Over time, however, human intelligence developed in phases that is interrelated with brain physiology, cranial anatomy and morphology, and rapidly changing climate and environments.

Tool-use

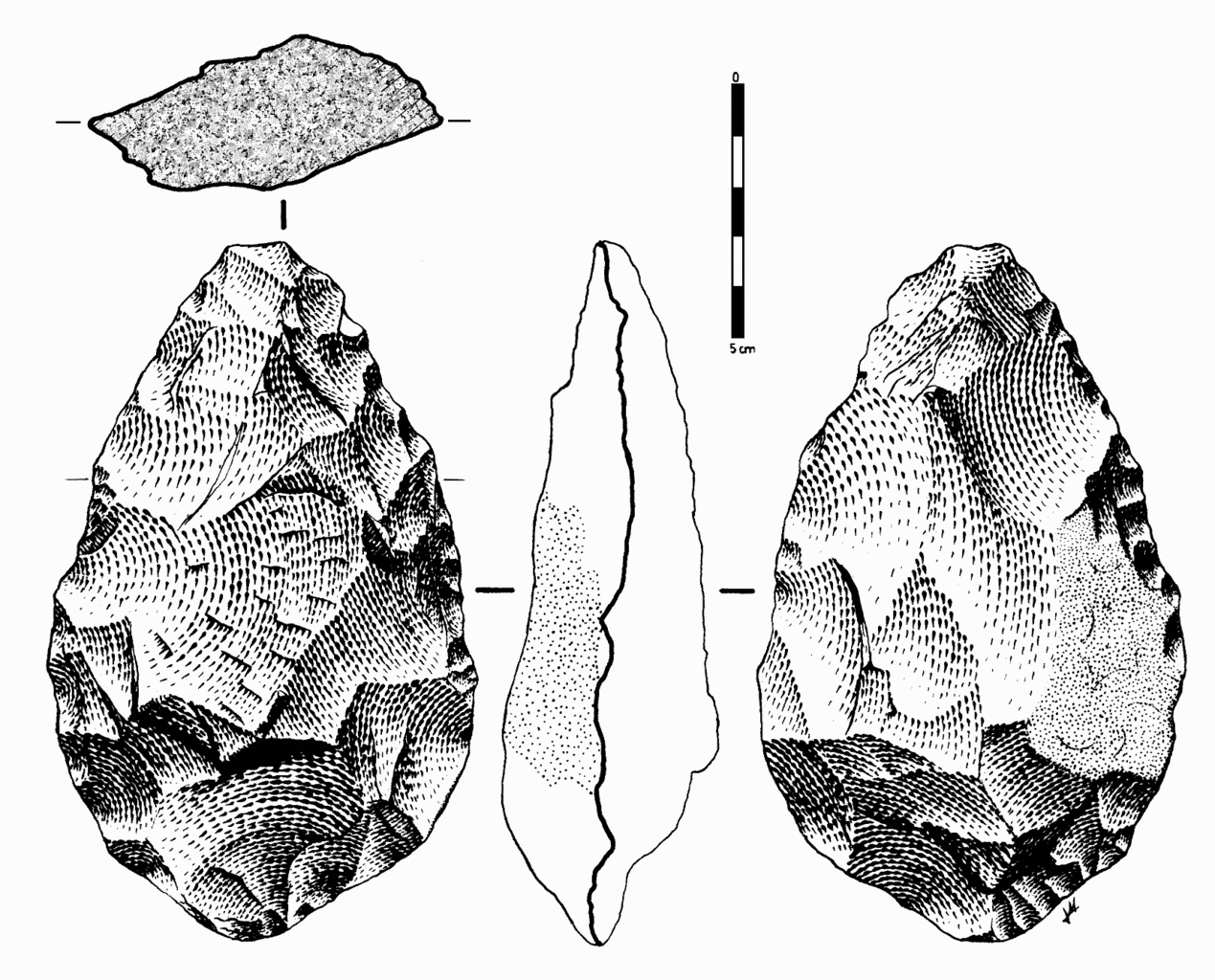

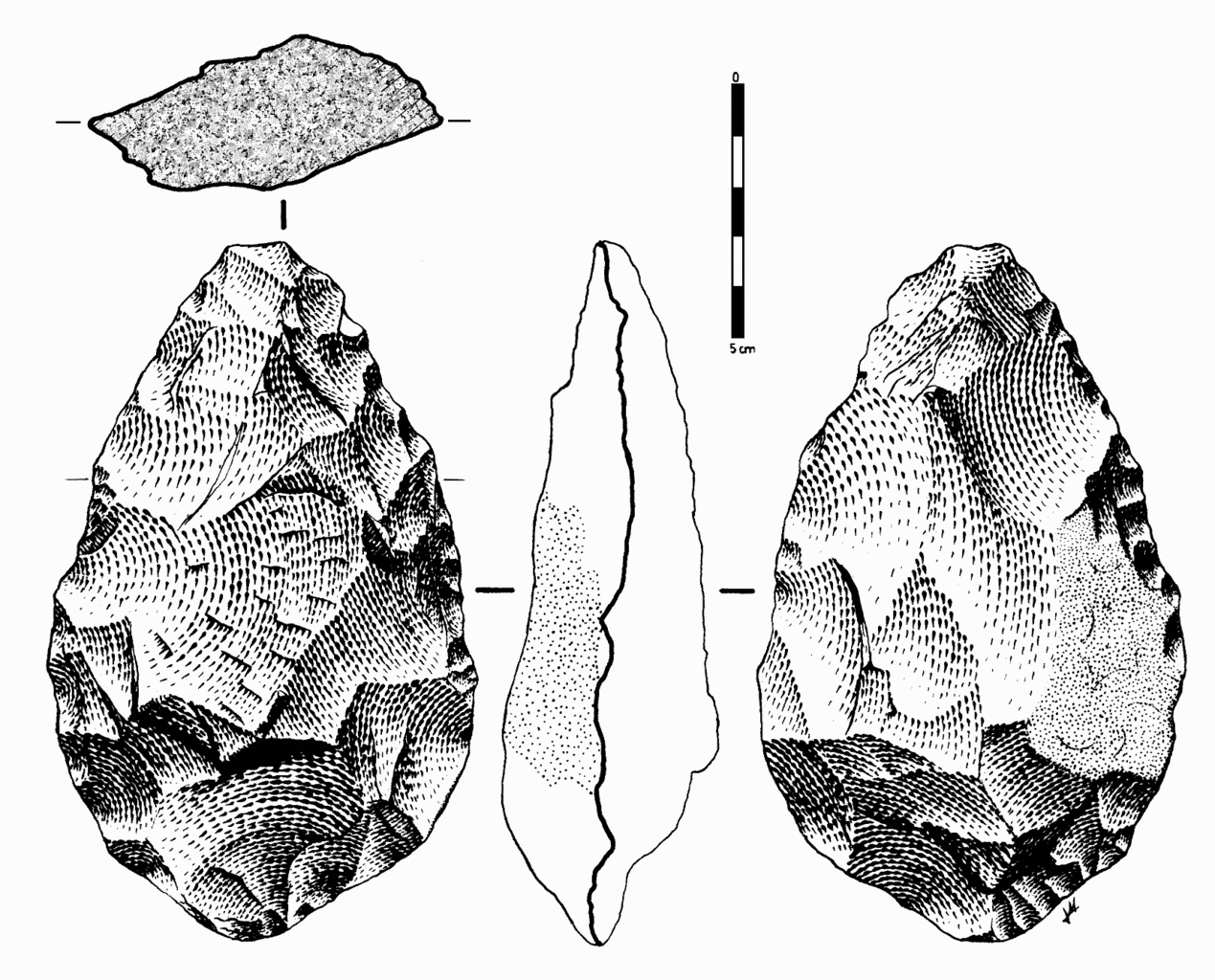

The study of the evolution of cognition relies on the archaeological record made up of assemblages of material culture, particularly from the Paleolithic Period, to make inferences about our ancestor's cognition. Paleo-anthropologists from the past half-century have had the tendency of reducingstone tool

A stone tool is, in the most general sense, any tool made either partially or entirely out of stone. Although stone tool-dependent societies and cultures still exist today, most stone tools are associated with prehistoric (particularly Stone A ...

artifacts to physical products of the metaphysical activity taking place in the brains of hominins. Recently, a new approach called 4E cognition (see Models for other approaches) has been developed by anthropologist Thomas Wynn, and cognitive archaeologists Karenleigh Overmann and Lambros Malafouris, to move past the "internal" and "external" dichotomy by treating stone tools as objects with agency in both providing insight to hominin cognition and having a role in the development of early hominin cognition. The 4E cognition approach describes cognition as embodied, embedded, enactive, and extended, to understand the interconnected nature between the mind, body, and environment.

There are four major categories of tools created and used throughout human evolution that are associated with the corresponding evolution of the brain

There is much to be discovered about the evolution of the brain and the principles that govern it. While much has been discovered, not everything currently known is well understood. The evolution of the brain has appeared to exhibit diverging ada ...

and intelligence. Stone tools such as flakes and cores used by ''Homo habilis

''Homo habilis'' ("handy man") is an extinct species of archaic human from the Early Pleistocene of East and South Africa about 2.31 million years ago to 1.65 million years ago (mya). Upon species description in 1964, ''H. habilis'' was highly ...

'' for cracking bones to extract marrow, known as the Oldowan

The Oldowan (or Mode I) was a widespread stone tool archaeological industry (style) in prehistory. These early tools were simple, usually made with one or a few flakes chipped off with another stone. Oldowan tools were used during the Lower ...

culture, make up the oldest major category of tools from about 2.5 and 1.6 million years ago. The development of stone tool technology suggests that our ancestors had the ability to hit cores with precision, taking into account the force and angle of the strike, and the cognitive planning and capacity to envision a desired outcome.

Acheulean

Acheulean (; also Acheulian and Mode II), from the French ''acheuléen'' after the type site of Saint-Acheul, is an archaeological industry of stone tool manufacture characterized by the distinctive oval and pear-shaped "hand axes" associated ...

culture, associated with ''Homo erectus'', is composed of bifacial, or double-sided, hand-axes, that "requires more planning and skill on the part of the toolmaker; he or she would need to be aware of principles of symmetry". In addition, some sites show evidence that selection of raw materials involved travel, advanced planning, cooperation, and thus communication with other hominins.

The third major category of tool industry marked by its innovation in tool-making technique and use is the Mousterian

The Mousterian (or Mode III) is an archaeological industry of stone tools, associated primarily with the Neanderthals in Europe, and to the earliest anatomically modern humans in North Africa and West Asia. The Mousterian largely defines the l ...

culture. Compared to previous tool cultures, which were regularly discarded after use, Mousterian tools, associated with Neanderthal

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an Extinction, extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ag ...

s, were specialized, built to last, and "formed a true toolkit". The making of these tools, called the Levallois technique

The Levallois technique () is a name given by archaeologists to a distinctive type of stone knapping developed around 250,000 to 300,000 years ago during the Middle Palaeolithic period. It is part of the Mousterian stone tool industry, and was u ...

, involves a multi-step process which yields several tools. In combination with other data, the formation of this tool culture for hunting large mammals in groups evidences the development of speech for communication and complex planning capabilities.

While previous tool cultures did not show great variation, the tools of early modern ''Homo sapiens'' are robust in the amount of artifacts and diversity in utility. There are several styles associated with this category of the Upper Paleolithic

The Upper Paleolithic (or Upper Palaeolithic) is the third and last subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. Very broadly, it dates to between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), according to some theories coin ...

, such as blades, boomerangs, atlatl

A spear-thrower, spear-throwing lever or ''atlatl'' (pronounced or ; Nahuatl ''ahtlatl'' ) is a tool that uses leverage to achieve greater velocity in dart or javelin-throwing, and includes a bearing surface which allows the user to store ene ...

s (spear throwers), and archery made from varying materials of stone, bone, teeth, and shell. Beyond use, some tools have been shown to have served as signifiers of status and group membership. The role of tools for social uses signal cognitive advancements such as complex language and abstract relations to things.

''Homo sapiens''

Genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

~Homo

''Homo'' () is the genus that emerged in the (otherwise extinct) genus '' Australopithecus'' that encompasses the extant species ''Homo sapiens'' ( modern humans), plus several extinct species classified as either ancestral to or closely rela ...

bar: color:period3

from:-200000 till:-1800000

at:-1800000 shift:(0,8) text:H. erectus

''Homo erectus'' (; meaning "upright man") is an extinct species of archaic human from the Pleistocene, with its earliest occurrence about 2 million years ago. Several human species, such as '' H. heidelbergensis'' and '' H. antecessor' ...

at:-1800000 text:H. ergaster

''Homo ergaster'' is an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Africa in the Early Pleistocene. Whether ''H. ergaster'' constitutes a species of its own or should be subsumed into ''H. erectus'' is an ongoing and unresolv ...

at:-1800000 shift:(0,-24) text:H. georgicus

The Dmanisi hominins, Dmanisi people, or Dmanisi man were a population of Early Pleistocene hominins whose fossils have been recovered at Dmanisi, Georgia. The fossils and stone tools recovered at Dmanisi range in age from 1.85–1.77 million ye ...

bar: color:period3

from:-1400000 till:end

at:-1400000 shift:(0,-16) text:H. habilis

''Homo habilis'' ("handy man") is an extinct species of archaic human from the Early Pleistocene of East and South Africa about 2.31 million years ago to 1.65 million years ago (mya). Upon species description in 1964, ''H. habilis'' was highly c ...

bar: color:period3

from:2013 till:-200000

at:-200000 text:H. sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, an ...

bar: color:period3

from:-1200000 shift:(0,4) till:-800000 text: H. antecessor

bar: color:period3

from:-29000 till:-230000

at:-230000 shift:(0,-10) text:H. neanderthalensis

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. While the ...

bar: color:period3

from:-230000 till:-600000

at:-600000 shift:(0,5) width:5 text: H. heidelbergensis

bar:Events color:nil mark:(line,black)

at:-77000 shift:(0,5) text:Toba Toba may refer to:

Languages

* Toba Sur language, spoken in South America

* Batak Toba, spoken in Indonesia

People

* Toba people, indigenous peoples of the Gran Chaco in South America

* Toba Batak people, a sub-ethnic group of Batak people from N ...

at:-640000 shift:(0,5) text: 3rd Y. Caldera

at:-1300000 shift:(0,5) text: 2nd Y. Caldera

bar:Events color:nil mark:(line,white)

from:-13000 till:2013 text: H.~extinction

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the Endling, last individual of the species, although the Functional ext ...

from:-781000 till:-13000 text: Q.~extinction

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the Endling, last individual of the species, although the Functional ext ...

Java Man

Java Man (''Homo erectus erectus'', formerly also ''Anthropopithecus erectus'', ''Pithecanthropus erectus'') is an early human fossil discovered in 1891 and 1892 on the island of Java (Dutch East Indies, now part of Indonesia). Estimated to be b ...

(−1.75e+06), Yuanmou Man

Yuanmou Man (, ''Homo erectus yuanmouensis'') is a subspecies of ''H. erectus'' which inhabited the Yuanmou Basin in the Yunnan Province, southwestern China, roughly 1.7 million years ago. It is the first fossil evidence of humans in China, tho ...

(−1.75e+06: -0.73e+06),

::Lantian Man

Lantian Man (), ''Homo erectus lantianensis'') is a subspecies of ''Homo erectus'' known from an almost complete mandible from Chenchiawo (陈家窝) Village discovered in 1963, and a partial skull from Gongwangling(公王岭) Village discovered ...

(−1.7e+06), Nanjing Man

Nanjing Man (''Homo erectus nankinensis'') is a subspecies of ''Homo erectus'' found in China. Large fragments of one male and one female skull and a molar tooth of ''H. e. nankinensis'' were discovered in 1993 in the Hulu Cave (葫芦洞) on th ...

(- 0.6e+06), Tautavel Man

Tautavel Man refers to the archaic humans which—from approximately 550,000 to 400,000 years ago—inhabited the Caune de l’Arago, a limestone cave in Tautavel, France. They are generally grouped as part of a long and highly variable lineag ...

(- 0.5e+06),

::Peking Man

Peking Man (''Homo erectus pekinensis'') is a subspecies of '' H. erectus'' which inhabited the Zhoukoudian Cave of northern China during the Middle Pleistocene. The first fossil, a tooth, was discovered in 1921, and the Zhoukoudian Cave has s ...

(- 0.4e+06), Solo Man

Solo Man (''Homo erectus soloensis'') is a subspecies of ''H. erectus'' that lived along the Solo River in Java, Indonesia, about 117,000 to 108,000 years ago in the Late Pleistocene. This population is the last known record of the species. ...

(- 0.4e+06), and Peștera cu Oase (- 0.378e+05)

''Homo sapiens'' intelligence

The eldest findings of ''Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture ...

'' in Jebel Irhoud

Jebel Irhoud or Adrar n Ighoud ( zgh, ⴰⴷⵔⴰⵔ ⵏ ⵉⵖⵓⴷ, Adrar n Iɣud; ar, جبل إيغود, žbəl iġud), is an archaeological site located just north of the locality known as Tlet Ighoud, approximately south-east of the cit ...

, Morocco date back years

Fossils of ''Homo sapiens'' were found in East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territories make up Eastern Africa:

Due to the historica ...

which are c. 200,000 years old. It is unclear to what extent these early modern humans had developed language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of ...

, music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspe ...

, religion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatur ...

, etc.

According to proponents of the Toba catastrophe theory

The Youngest Toba eruption was a supervolcano eruption that occurred around 74,000 years ago at the site of present-day Lake Toba in Sumatra, Indonesia. It is one of the Earth's largest known explosive eruptions. The Toba catastrophe theory ho ...

, the climate in non-tropical regions of the earth experienced a sudden freezing about 70,000 years ago, because of a huge explosion of the Toba volcano that filled the atmosphere with volcanic ash for several years. This reduced the human population to less than 10,000 breeding pairs in equatorial Africa, from which all modern humans are descended. Being unprepared for the sudden change in climate, the survivors were those intelligent enough to invent new tools and ways of keeping warm and finding new sources of food (for example, adapting to ocean fishing based on prior fishing skills used in lakes and streams that became frozen).

Around 80,000–100,000 years ago, three main lines of ''Homo sapiens'' diverged, bearers of mitochondrial haplogroup L1 (mtDNA) / A (Y-DNA) colonizing Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost subregion of the African continent, south of the Congo and Tanzania. The physical location is the large part of Africa to the south of the extensive Congo River basin. Southern Africa is home to a number o ...

(the ancestors of the Khoisan

Khoisan , or (), according to the contemporary Khoekhoegowab orthography, is a catch-all term for those indigenous peoples of Southern Africa who do not speak one of the Bantu languages, combining the (formerly "Khoikhoi") and the or ( in ...

/Capoid

Capoid race is a grouping formerly used for the Khoikhoi and San peoples in the context of a now-outdated model of dividing humanity into different races. The term was introduced by Carleton S. Coon in 1962 and named for the Cape of Good Hope.'' ...

peoples), bearers of haplogroup L2 (mtDNA) / B (Y-DNA) settling Central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known a ...

and West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali ...

(the ancestors of Niger–Congo and Nilo-Saharan

The Nilo-Saharan languages are a proposed family of African languages spoken by some 50–60 million people, mainly in the upper parts of the Chari and Nile rivers, including historic Nubia, north of where the two tributaries of the Nile meet. ...

speaking peoples), while the bearers of haplogroup L3 remained in East Africa.

The "Great Leap Forward" leading to full behavioral modernity

Behavioral modernity is a suite of behavioral and cognitive traits that distinguishes current '' Homo sapiens'' from other anatomically modern humans, hominins, and primates. Most scholars agree that modern human behavior can be characterize ...

sets in only after this separation. Rapidly increasing sophistication in tool-making and behaviour is apparent from about 80,000 years ago, and the migration out of Africa follows towards the very end of the Middle Paleolithic

The Middle Paleolithic (or Middle Palaeolithic) is the second subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age as it is understood in Europe, Africa and Asia. The term Middle Stone Age is used as an equivalent or a synonym for the Middle Paleol ...

, some 60,000 years ago. Fully modern behaviour, including figurative art

Figurative art, sometimes written as figurativism, describes artwork (particularly paintings and sculptures) that is clearly derived from real object sources and so is, by definition, representational. The term is often in contrast to abstract ...

, music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspe ...

, self-ornamentation, trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct exc ...

, burial rite

A funeral is a ceremony connected with the final disposition of a corpse, such as a burial or cremation, with the attendant observances. Funerary customs comprise the complex of beliefs and practices used by a culture to remember and respect ...

s etc. is evident by 30,000 years ago. The oldest unequivocal examples of prehistoric art

In the history of art, prehistoric art is all art produced in preliterate, prehistorical cultures beginning somewhere in very late geological history, and generally continuing until that culture either develops writing or other methods of re ...

date to this period, the Aurignacian

The Aurignacian () is an archaeological industry of the Upper Paleolithic

associated with European early modern humans (EEMH) lasting from 43,000 to 26,000 years ago. The Upper Paleolithic developed in Europe some time after the Levant, where ...

and the Gravettian

The Gravettian was an archaeological industry of the European Upper Paleolithic that succeeded the Aurignacian circa 33,000 years BP. It is archaeologically the last European culture many consider unified, and had mostly disappeared by 2 ...

periods of prehistoric Europe

Prehistoric Europe is Europe with human presence but before the start of recorded history, beginning in the Lower Paleolithic. As history progresses, considerable regional irregularities of cultural development emerge and increase. The region o ...

, such as the Venus figurines

A Venus figurine is any Upper Palaeolithic statuette portraying a woman, usually carved in the round.Fagan, Brian M., Beck, Charlotte, "Venus Figurines", ''The Oxford Companion to Archaeology'', 1996, Oxford University Press, pp. 740–741 Most ...

and cave painting

In archaeology, Cave paintings are a type of parietal art (which category also includes petroglyphs, or engravings), found on the wall or ceilings of caves. The term usually implies prehistoric origin, and the oldest known are more than 40,000 ye ...

(Chauvet Cave

The Chauvet-Pont-d'Arc Cave (french: Grotte Chauvet-Pont d'Arc, ) in the Ardèche department of southeastern France is a cave that contains some of the best-preserved figurative cave paintings in the world, as well as other evidence of Upper Pale ...

) and the earliest musical instruments

A musical instrument is a device created or adapted to make musical sounds. In principle, any object that produces sound can be considered a musical instrument—it is through purpose that the object becomes a musical instrument. A person who pl ...

(the bone pipe of Geissenklösterle

Geissenklösterle () is an archaeological site of significance for the central European Upper Paleolithic, located near the town of Blaubeuren in the Swabian Jura in Baden-Württemberg, southern Germany. First explored in 1963, the cave contains t ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

, dated to about 36,000 years ago).

The human brain has evolved gradually over the passage of time; a series of incremental changes occurred as a result of external stimuli and conditions. It is crucial to keep in mind that evolution operates within a limited framework at a given point in time. In other words, the adaptations that a species can develop are not infinite and are defined by what has already taken place in the evolutionary timeline of a species. Given the immense anatomical and structural complexity of the brain, its evolution (and the congruent evolution of human intelligence), can only be reorganized in a finite number of ways. The majority of said changes occur either in terms of size or in terms of developmental timeframes.

The

The cerebral cortex

The cerebral cortex, also known as the cerebral mantle, is the outer layer of neural tissue of the cerebrum of the brain in humans and other mammals. The cerebral cortex mostly consists of the six-layered neocortex, with just 10% consisting o ...

is divided into four lobes (frontal, parietal, occipital, and temporal) each with specific functions. The cerebral cortex is significantly larger in humans than in any other animal and is responsible for higher thought processes such as: reasoning, abstract thinking, and decision making. Another characteristic that makes humans special and sets them apart from any other species is our ability to produce and understand complex, syntactic language. The cerebral cortex, particularly in the temporal, parietal, and frontal lobes, are populated with neural circuits dedicated to language. There are two main areas of the brain commonly associated with language, namely: Wernicke's area

Wernicke's area (; ), also called Wernicke's speech area, is one of the two parts of the cerebral cortex that are linked to speech, the other being Broca's area. It is involved in the comprehension of written and spoken language, in contrast to B ...

and Broca's area

Broca's area, or the Broca area (, also , ), is a region in the frontal lobe of the dominant hemisphere, usually the left, of the brain with functions linked to speech production.

Language processing has been linked to Broca's area since Pier ...

. The former is responsible for the understanding of speech and the latter for the production of speech. Homologous regions have been found in other species (i.e. Area 44 and 45 have been studied in chimpanzees) but they are not as strongly related to or involved in linguistic activities as in humans.

A big portion of the scholarly literature focus on the evolution, and subsequent influence, of culture. This is in part because the leaps human intelligence has taken are far greater than those that would have resulted if our ancestors had simply responded to their environments, inhabiting them as hunter-gatherers.

Models

Social brain hypothesis

The social brain hypothesis was proposed by British anthropologistRobin Dunbar

Robin Ian MacDonald Dunbar (born 28 June 1947) is a British anthropologist and evolutionary psychologist and a specialist in primate behaviour. He is currently head of the Social and Evolutionary Neuroscience Research Group in the Department ...

, who argues that human intelligence did not evolve primarily as a means to solve ecological problems, but rather as a means of surviving and reproducing in large and complex social groups. Some of the behaviors associated with living in large groups include reciprocal altruism, deception and coalition formation. These group dynamics relate to Theory of Mind

In psychology, theory of mind refers to the capacity to understand other people by ascribing mental states to them (that is, surmising what is happening in their mind). This includes the knowledge that others' mental states may be different fro ...

or the ability to understand the thoughts and emotions of others, though Dunbar himself admits in the same book that it is not the flocking itself that causes intelligence to evolve (as shown by ruminant

Ruminants (suborder Ruminantia) are hoofed herbivorous grazing or browsing mammals that are able to acquire nutrients from plant-based food by fermenting it in a specialized stomach prior to digestion, principally through microbial actions. The ...

s).

Dunbar argues that when the size of a social group increases, the number of different relationships in the group may increase by orders of magnitude. Chimpanzees live in groups of about 50 individuals whereas humans typically have a social circle of about 150 people, which is also the typical size of social communities in small societies and personal social networks; this number is now referred to as Dunbar's number

Dunbar's number is a suggested cognitive limit to the number of people with whom one can maintain stable social relationships—relationships in which an individual knows who each person is and how each person relates to every other person. This ...

. In addition, there is evidence to suggest that the success of groups is dependent on their size at foundation, with groupings of around 150 being particularly successful, potentially reflecting the fact that communities of this size strike a balance between the minimum size of effective functionality and the maximum size for creating a sense of commitment to the community. According to the social brain hypothesis, when hominids started living in large groups, selection favored greater intelligence. As evidence, Dunbar cites a relationship between neocortex size and group size of various mammals.

Criticism

Phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups ...

studies of brain sizes in primates show that while diet predicts primate brain size, sociality does not predict brain size when corrections are made for cases in which diet affects both brain size and sociality. The exceptions to the predictions of the social intelligence hypothesis, which that hypothesis has no predictive model for, are successfully predicted by diets that are either nutritious but scarce or abundant but poor in nutrients. Researchers have found that frugivore

A frugivore is an animal that thrives mostly on raw fruits or succulent fruit-like produce of plants such as roots, shoots, nuts and seeds. Approximately 20% of mammalian herbivores eat fruit. Frugivores are highly dependent on the abundance and ...

s tend to exhibit larger brain size than folivore

In zoology, a folivore is a herbivore that specializes in eating leaves. Mature leaves contain a high proportion of hard-to-digest cellulose, less energy than other types of foods, and often toxic compounds.Jones, S., Martin, R., & Pilbeam, D. (1 ...

s. One potential explanation for this finding is that frugivory requires "extractive foraging", or the process of locating and preparing hard-shelled foods, such as nuts, insects, and fruit. Extractive foraging requires higher cognitive processing, which could help explain larger brain size. However, other researchers argue that extractive foraging was not a catalyst in the evolution of primate brain size, demonstrating that some non primates exhibit advanced foraging techniques. Other explanations for the positive correlation between brain size and frugivory highlight how the high-energy, frugivore diet facilitates fetal brain growth and requires spatial mapping to locate the embedded foods.

Meerkat

MeerKAT, originally the Karoo Array Telescope, is a radio telescope consisting of 64 antennas in the Meerkat National Park, in the Northern Cape of South Africa. In 2003, South Africa submitted an expression of interest to host the Square Ki ...

s have far more social relationships than their small brain capacity would suggest. Another hypothesis is that it is actually intelligence that causes social relationships to become more complex, because intelligent individuals are more difficult to learn to know.

There are also studies that show that Dunbar's number is not the upper limit of the number of social relationships in humans either.

The hypothesis that it is brain capacity that sets the upper limit for the number of social relationships is also contradicted by computer simulations that show simple unintelligent reactions to be sufficient to emulate "ape politics" and by the fact that some social insects such as the paper wasp do have hierarchies in which each individual has its place (as opposed to herding without social structure) and maintains their hierarchies in groups of approximately 80 individuals with their brains smaller than that of any mammal.

Insects provide an opportunity to explore this since they exhibit an unparalleled diversity of social forms to permanent colonies containing many individuals working together as a collective organism and have evolved an impressive range of cognitive skills despite their small nervous systems. Social insects are shaped by ecology, including their social environment. Studies aimed to correlating brain volume to complexity have failed to identify clear correlations between sociality and cognition because of cases like social insects. In humans, societies are usually held together by the ability of individuals to recognize features indicating group membership. Social insects, likewise, often recognize members of their colony allowing them to defend against competitors. Ants do this by comparing odors which require fine discrimination of multicomponent variable cues. Studies suggest this recognition is achieved through simple cognitive operations that do not involve long-term memory but through sensory adaptation or habituation. In honeybees, their symbolic 'dance' is a form of communication that they use to convey information with the rest of their colony. In an even more impressive social use of their dance language, bees indicate suitable nest locations to a swarm in search of a new home. The swarm builds a consensus from multiple 'opinions' expressed by scouts with different information, to finally agree on a single destination to which the swarm relocates.

Cultural intelligence hypothesis

Overview

Similar to but distinct from the social brain hypothesis is the cultural intelligence or cultural brain hypothesis, which dictates that human brain size, cognitive ability and intelligence have increased over generations due to cultural information from a mechanism known as social learning. The hypothesis also predicts a positive correlation between species with a higher dependency and more frequent opportunities for social learning and overall cognitive ability. This is because social learning allows species to develop cultural skills and strategies for survival; in this way it can be said that heavily cultural species should in theory be more intelligent. Humans have been widely acknowledged as the most intelligent species on the planet, with big brains with ample cognitive abilities and processing power which outcompete all other species. In fact, humans have shown an enormous increase in brain size and intelligence over millions of years of evolution. This is because humans have been referred to as an 'evolved cultural species'; one that has an unrivalled reliance on culturally transmitted knowledge due to the social environment around us. This is down to social transmission of information which spreads significantly faster in human populations relative to changes in genetics. Put simply, we are the most cultural species there is, and are therefore the most intelligent species there is. The key point when concerning evolution of intelligence is that this cultural information has been consistently transmitted across generations to build vast amounts of cultural skills and knowledge throughout the human race. Dunbar's social brain hypothesis on the other hand dictates that our brains evolved primarily due to complex social interactions in groups, so in this way the two hypotheses are distinct from each other in that the cultural intelligence hypothesis focuses more on an in increase in intelligence from socially transmitted information. We see a shift in focus from 'social' interactions to learning strategies. The hypothesis can also be seen to contradict the idea of human 'general intelligence' by emphasising the process of cultural skills and information being learned from others. In 2018, Muthukrishna and researchers constructed a model based on the cultural intelligence hypothesis which revealed relationships between brain size, group size, social learning and mating structures. The model had three underlying assumptions: # Brain size, complexity and organisation were grouped into one variable # A larger brain results in larger capacity for adaptive knowledge # More adaptive knowledge increases fitness of organisms Using evolutionary simulation the researchers were able to confirm the existence of hypothesised relationships. Results concerning the cultural intelligence hypothesis model showed that larger brains can store more information and adaptive knowledge, thus supporting larger groups. This abundance of adaptive knowledge can then be used for frequent social learning opportunities.Further empirical evidence

As previously mentioned, social learning is the foundation of the cultural intelligence hypothesis and can be described simplistically as learning from others. It involves behaviours such as imitation, observational learning, influences from family and friends and explicit teaching from others. What sets humans apart from other species is that, due to our emphasis on culturally acquired information, we have evolved to already possess significant social learning abilities from infancy. Neurological studies on nine month old infants were conducted by researchers in 2012 to demonstrate this phenomenon. The study involved infants observing a caregiver making a sound with a rattle over a period of one week. The brains of the infants were monitored throughout the study. Researchers found that the infants were able to activate neural pathways associated with making a sound with the rattle without actually doing the action themselves. Here we can see human social learning in action- infants were able to understand the effects of a particular action simply by observing the performance of the action by someone else. Not only does this study demonstrate the neural mechanisms of social learning, but it also demonstrates our inherent ability to acquire cultural skills from those around us from the very start of our lives- it therefore shows strong support for the cultural intelligent hypothesis. Various studies have been conducted to show the cultural intelligence hypothesis in action on a wider scale. One particular study in 2016 investigated two orangutan species, including the more social Sumatran species and the less sociable Bornean species. The aim was to test the notion that species with a higher frequency of opportunities for social learning should evolve to be more intelligent. Results showed that the Sumatrans consistently performed better in cognitive tests compared to the less Borneans. The Sumatrans also showed greater inhibition and more cautious behaviour within their habitat. This was one of the first studies to show evidence for the cultural intelligence hypothesis in a non human species- frequency of learning opportunities had gradually produced differences in cognitive abilities between the two species.Transformative cultural intelligence hypothesis

A study in 2018 proposed an altered variant of the original version of the hypothesis called the 'transformative cultural intelligence hypothesis'. The research involved investigating four year old's problem solving skills in different social contexts. The children were asked to extract a floating object from a tube using water. Nearly were all unsuccessful without cues, however most children succeeded after being shown a pedagogical solution suggesting video. When the same video was shown in a non pedagogical manner however, the children's success in the task did not improve. Crucially, this meant that the children's physical cognition and problem solving ability was therefore affected by how the task was socially presented to them. Researchers thus formulated the transformative cultural intelligence hypothesis, which stresses that our physical cognition is developed and affected by the social environment around us. This challenges the traditional cultural intelligence hypothesis which states that it is humans social cognition and not physical cognition which is superior to our nearest primate relatives; here we uniquely see physical cognition in humans affected by external social factors. This phenomenon has not been seen in other species.Reduction in aggression

Another theory that tries to explain the growth of human intelligence is the reduced aggression theory (aka self-domestication theory). According to this strand of thought what led to the evolution of advanced intelligence in ''Homo sapiens'' was a drastic reduction of the aggressive drive. This change separated us from other species of monkeys and primates, where this aggressivity is still in plain sight, and eventually lead to the development of quintessential human traits such as empathy, social cognition and culture.Eccles, John C. (1989). Evolution of the Brain: Creation of the Self. Foreword by Carl Popper. London: Routledge .de Waal, Frans B. M. (1989). Peacemaking among primates. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.. This theory has received strong support from studies of animal domestication where selective breeding for tameness has, in only a few generations, led to the emergence of impressive "humanlike" abilities. Tamed foxes, for example, exhibit advanced forms of social communication (following pointing gestures), pedomorphic physical features (childlike faces, floppy ears) and even rudimentary forms oftheory of mind

In psychology, theory of mind refers to the capacity to understand other people by ascribing mental states to them (that is, surmising what is happening in their mind). This includes the knowledge that others' mental states may be different fro ...

(eye contact seeking, gaze following).Belyaev, D. K. 1984. "Foxes" pp. 211-214. In Mason I. L. ed., ''Evolution of Domesticated Animals''. Prentice Hall Press.. Evidence also comes from the field of ethology

Ethology is the scientific study of animal behaviour, usually with a focus on behaviour under natural conditions, and viewing behaviour as an evolutionarily adaptive trait. Behaviourism as a term also describes the scientific and objecti ...

(which is the study of animal behavior, focused on observing species in their natural habitat rather than in controlled laboratory settings) where it has been found that animals with a gentle and relaxed manner of interacting with each other – like for example stumptailed macaques, orangutans and bonobos – have more advanced socio-cognitive abilities than those found among the more aggressive chimpanzees and baboons. It is hypothesized that these abilities derive from a selection against aggression.

On a mechanistic level these changes are believed to be the result of a systemic downregulation of the sympathetic nervous system (the fight-or-flight reflex). Hence, tamed foxes show a reduced adrenal gland size and have an up to fivefold reduction in both basal and stress-induced blood cortisol levels.Osadschuk, L. V. 1997. "Effects of domestication on the adrenal cortisol production of silver foxes during embryonic development ". In In L. N. Trut and L. V. Osadschuk eds., ''Evolutionary-Genetic and Genetic-Physiological Aspects of Fur Animal Domestication''. Oslo: Scientifur.. Similarly, domesticated rats and guinea pigs have both reduced adrenal gland size and reduced blood corticosterone levels. It seems as though the neoteny

Neoteny (), also called juvenilization,Montagu, A. (1989). Growing Young. Bergin & Garvey: CT. is the delaying or slowing of the physiological, or somatic, development of an organism, typically an animal. Neoteny is found in modern humans compare ...

of domesticated animals significantly prolongs the immaturity of their hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system (which is otherwise only immature for a short period when they are pups/kittens) and this opens up a larger "socialization window" during which they can learn to interact with their caretakers in a more relaxed way.

This downregulation of sympathetic nervous system reactivity is also believed to be accompanied by a compensatory increase in a number of opposing organs and systems. Although these are not as well specified various candidates for such "organs" have been proposed: the parasympathetic system as a whole, the septal area over the amygdala, the oxytocin system, the endogenous opioids and various forms of quiescent immobilization which antagonize the fight-or-flight reflex.

Social exchange theory

Other studies suggest that social exchange between individuals is a vital adaptation to the human brain, going as far to say that the human mind could be equipped with a neurocognitive system specialized for reasoning about social exchange.This adaption is predicted to evolve when two parties are both better off than they were before by mutually exchanging things they value less for things they value more. However, selection will only favor social exchange when both parties benefit. Consequently, the existence of cheaters—those who fail to deliver fair benefits—threatens the evolution of exchange. Using evolutionary game theory, it has been shown that adaptations for social exchange can be favored and stably maintained by natural selection, but only if they include design features that enable them to detect cheaters, and cause them to channel future exchanges to reciprocators and away from cheaters. Thus, humans use social contracts to lay the benefits and losses each party will be receiving (if you accept benefit B from me, then you must satisfy my requirement R). Humans have evolved an advanced cheater detection system, equipped with proprietary problem-solving strategies that evolved to match the recurrent features of their corresponding problem domains. Not only do humans need to determine that the contract was violated, but also if the violation was intentionally done. Therefore, systems are specialized to detect contract violations that imply intentional cheating. One problem with the hypothesis that specific punishment for intentional deception could coevolve with intelligence is the fact that selective punishment of individuals with certain characteristics selects against the characteristics in question. For example, if only individuals capable of remembering what they had agreed to were punished for breaking agreements, evolution would have selected against the ability to remember what one had agreed to. Though this becomes a superficial argument after considering the balancing positive selection for the ability to successfully 'make ones case'. Intelligence predicts the number of arguments one can make when taking either side of a debate. Humans who could get away with behaviours that exploited within and without-group cooperation, getting more while giving less, would overcome this. In 2004, psychologistSatoshi Kanazawa

Satoshi Kanazawa (born 16 November 1962) is an American-born British evolutionary psychologist and writer. He is currently Reader in Management at the London School of Economics. Kanazawa's comments and research on race and intelligence, heal ...

argued that '' g'' was a domain-specific

Domain specificity is a theoretical position in cognitive science (especially modern cognitive development) that argues that many aspects of cognition are supported by specialized, presumably evolutionarily specified, learning devices. The posit ...

, species-typical, information processing

Information processing is the change (processing) of information in any manner detectable by an observer. As such, it is a process that ''describes'' everything that happens (changes) in the universe, from the falling of a rock (a change in posi ...

psychological adaptation

A psychological adaptation is a functional, cognitive or behavioral trait that benefits an organism in its environment. Psychological adaptations fall under the scope of evolved psychological mechanisms (EPMs), however, EPMs refer to a less restric ...

, and in 2010, Kanazawa argued that ''g'' correlated only with performance on evolutionarily unfamiliar rather than evolutionarily familiar problems, proposing what he termed the "Savanna-IQ interaction hypothesis". In 2006, ''Psychological Review

''Psychological Review'' is a bimonthly peer-reviewed academic journal that covers psychology, psychological theory. It was established by James Mark Baldwin (Princeton University) and James McKeen Cattell (Columbia University) in 1894 as a publica ...

'' published a comment reviewing Kanazawa's 2004 article by psychologists Denny Borsboom

Denny Borsboom (born November 9, 1973) is a Dutch psychologist and psychometrician. He has been a professor of psychology at the University of Amsterdam since 2013. His work has included applying network theory to the study of mental disorders and ...

and Conor Dolan

Conor Vivian Dolan (born 5 April 1962 in Blenheim, New Zealand, also sometimes known as C.V. Dolan) is a New Zealand psychologist and professor in the Faculty of Behavioural and Movement Sciences at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

The Vrije Univ ...

that argued that Kanazawa's conception of ''g'' was empirically unsupported and purely hypothetical and that an evolutionary account of ''g'' must address it as a source of individual differences

Differential psychology studies the ways in which individuals differ in their behavior and the processes that underlie it. This is a discipline that develops classifications (taxonomies) of psychological individual differences. This is distingui ...

, and in response to Kanazawa's 2010 article, psychologists Scott Barry Kaufman

Scott Barry Kaufman is an American cognitive scientist, author, podcaster, and popular science writer. His writing and research focuses on intelligence, creativity, and human potential. Most media attention has focused on Kaufman's attempt to red ...

, Colin G. DeYoung, Deirdre Reis, and Jeremy R. Gray gave 112 subjects a 70-item computerized version of the Wason selection task

The Wason selection task (or ''four-card problem'') is a logic puzzle devised by Peter Cathcart Wason in 1966. It is one of the most famous tasks in the study of deductive reasoning. An example of the puzzle is:

A response that identifies a car ...

(a logic puzzle

A logic puzzle is a puzzle deriving from the mathematical field of deduction.

History

The logic puzzle was first produced by Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, who is better known under his pen name Lewis Carroll, the author of ''Alice's Adventures in W ...

) in a social relation

A social relation or also described as a social interaction or social experience is the fundamental unit of analysis within the social sciences, and describes any voluntary or involuntary interpersonal relationship between two or more individuals ...

s context as proposed by Leda Cosmides

Leda Cosmides (born May 1957) is an American psychologist, who, together with anthropologist husband John Tooby, helped develop the field of evolutionary psychology.

Biography

Cosmides originally studied biology at Radcliffe College/Harvard Univ ...

and John Tooby

John Tooby (born 1952) is an American anthropologist, who, together with psychologist wife Leda Cosmides, helped pioneer the field of evolutionary psychology.

Biography

Tooby received his PhD in Biological Anthropology from Harvard Universit ...

in ''The Adapted Mind

''The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture'' is a 1992 book edited by the anthropologists Jerome H. Barkow and John Tooby and the psychologist Leda Cosmides. First published by Oxford University Press, it is widel ...

'', and found instead that "performance on non-arbitrary, evolutionarily familiar problems is more strongly related to general intelligence than performance on arbitrary, evolutionarily novel problems".

Peter Cathcart Wason

Peter Cathcart Wason (22 April 1924 – 17 April 2003) was a cognitive psychologist at University College, London who pioneered the Psychology of Reasoning. He progressed explanations as to why people make certain consistent mistakes in logical r ...

originally demonstrated that not even 10% of subjects found the correct solution and his finding was replicated. Psychologists Patricia Cheng, Keith Holyoak, Richard E. Nisbett

__NOTOC__

Richard Eugene Nisbett (born June 1, 1941) is an American social psychologist and writer. He is the Theodore M. Newcomb Distinguished Professor of social psychology and co-director of the Culture and Cognition program at the University ...

, and Lindsay M. Oliver demonstrated experimentally that subjects who have completed semester-long college courses in propositional calculus

Propositional calculus is a branch of logic. It is also called propositional logic, statement logic, sentential calculus, sentential logic, or sometimes zeroth-order logic. It deals with propositions (which can be true or false) and relations b ...

do not perform better on the Wason selection task than subjects who do not complete such college courses. Tooby and Cosmides originally proposed a social relations context for the Wason selection task as part of a larger computational theory of social exchange after they began reviewing the previous experiments about the task beginning in 1983. Despite other experimenters finding that some contexts elicited more correct subject responses than others, no theoretical explanation for differentiating between them was identified until Tooby and Cosmides proposed that disparities in subjects performance on contextualized versus non-contextualized variations of the task was a by-product

A by-product or byproduct is a secondary product derived from a production process, manufacturing process or chemical reaction; it is not the primary product or service being produced.

A by-product can be useful and marketable or it can be consid ...

of a specialized cheater-detection module

Module, modular and modularity may refer to the concept of modularity. They may also refer to:

Computing and engineering

* Modular design, the engineering discipline of designing complex devices using separately designed sub-components

* Modul ...

, and Tooby and Cosmides later noted that whether there are evolved cognitive mechanisms for the content-blind rules of logical inference is disputed.

Additionally, economist Thomas Sowell

Thomas Sowell (; born June 30, 1930) is an American author, economist, political commentator and academic who is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution. With widely published commentary and books—and as a guest on TV and radio—he becam ...

has noted that numerous studies finding disparities between the mean test scores of ethnic groups on intelligence tests

An intelligence quotient (IQ) is a total score derived from a set of standardized tests or subtests designed to assess human intelligence. The abbreviation "IQ" was coined by the psychologist William Stern for the German term ''Intelligenzq ...

have found that ethnic groups with lower mean test scores have tended to perform worst on non-verbal

Nonverbal communication (NVC) is the transmission of messages or signals through a nonverbal platform such as eye contact, facial expressions, gestures, posture, and body language. It includes the use of social cues, kinesics, distance ( proxe ...

, non-informational, or abstract reasoning

Abstraction in its main sense is a conceptual process wherein general rule of inference, rules and concepts are derived from the usage and classification of specific examples, literal ("real" or "Abstract and concrete, concrete") signifiers, firs ...

test items. Writing after the completion of the Human Genome Project

The Human Genome Project (HGP) was an international scientific research project with the goal of determining the base pairs that make up human DNA, and of identifying, mapping and sequencing all of the genes of the human genome from both ...

in 2003, psychologist Earl B. Hunt

Earl B. Hunt (January 8, 1933 – April 12 or 13, 2016) was an American psychologist specializing in the study of human and artificial intelligence. Within these fields he focused on individual differences in intelligence and the implications ...

noted in 2011 that no genes related to differences in cognitive skills across various racial and ethnic groups had ever been discovered, and in 2012, ''American Psychologist

''American Psychologist'' is a peer-reviewed academic journal published by the American Psychological Association. The journal publishes articles of broad interest to psychologists, including empirical reports and scholarly reviews covering scien ...

'' published a review of new findings by psychologists Richard E. Nisbett

__NOTOC__