cyclol on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The cyclol hypothesis is the now discredited first structural model of a folded,

The cyclol hypothesis is the now discredited first structural model of a folded,

Wrinch developed this suggestion into a full-fledged model of

Wrinch developed this suggestion into a full-fledged model of

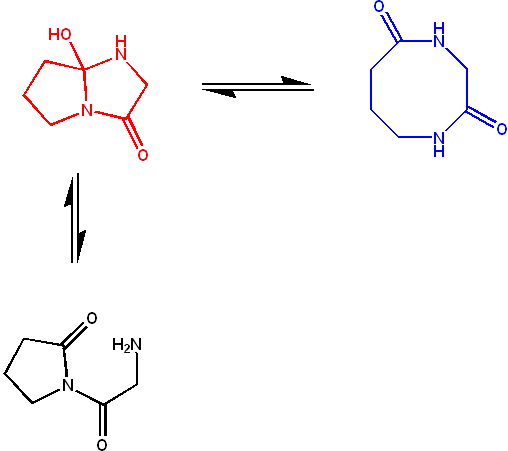

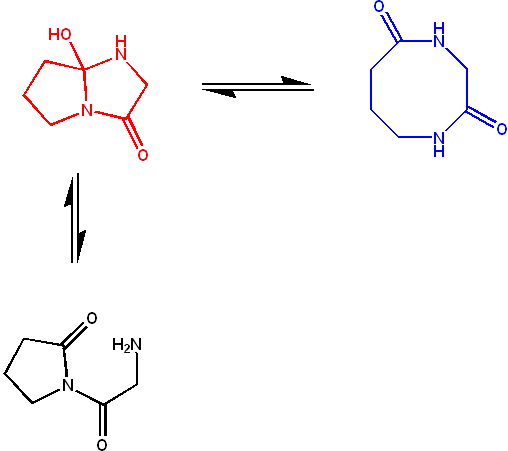

In two tandem Letters to the Editor (1936), Wrinch and Frank addressed the question of whether the cyclol form of the peptide group was indeed more stable than the amide form. A relatively simple calculation showed that the cyclol form is significantly ''less'' stable than the amide form. Therefore, the cyclol model would have to be abandoned unless a compensating source of energy could be identified. Initially, Frank proposed that the cyclol form might be stabilized by better interactions with the surrounding solvent; later, Wrinch and

In two tandem Letters to the Editor (1936), Wrinch and Frank addressed the question of whether the cyclol form of the peptide group was indeed more stable than the amide form. A relatively simple calculation showed that the cyclol form is significantly ''less'' stable than the amide form. Therefore, the cyclol model would have to be abandoned unless a compensating source of energy could be identified. Initially, Frank proposed that the cyclol form might be stabilized by better interactions with the surrounding solvent; later, Wrinch and

In her fifth paper on cyclols (1937), Wrinch identified the conditions under which two planar cyclol fabrics could be joined to make an angle between their planes while respecting the chemical bond angles. She identified a mathematical simplification, in which the non-planar six-membered rings of atoms can be represented by planar "median hexagon"s made from the midpoints of the chemical bonds. This "median hexagon" representation made it easy to see that the cyclol fabric planes can be joined correctly if the

In her fifth paper on cyclols (1937), Wrinch identified the conditions under which two planar cyclol fabrics could be joined to make an angle between their planes while respecting the chemical bond angles. She identified a mathematical simplification, in which the non-planar six-membered rings of atoms can be represented by planar "median hexagon"s made from the midpoints of the chemical bonds. This "median hexagon" representation made it easy to see that the cyclol fabric planes can be joined correctly if the

The cyclol fabric was shown to be implausible for several reasons. Hans Neurath and Henry Bull showed that the dense packing of side chains in the cyclol fabric was inconsistent with the experimental density observed in protein films. Maurice Huggins calculated that several non-bonded atoms of the cyclol fabric would approach more closely than allowed by their van der Waals radii; for example, the inner Hα and Cα atoms of the lacunae would be separated by only 1.68 Å (Figure 5). Haurowitz showed chemically that the outside of proteins could not have a large number of hydroxyl groups, a key prediction of the cyclol model, whereas Meyer and Hohenemser showed that cyclol condensations of amino acids did not exist even in minute quantities as a transition state. More general chemical arguments against the cyclol model were given by Bergmann and Niemann and by Neuberger. Infrared spectroscopic data showed that the number of carbonyl groups in a protein did not change upon hydrolysis, and that intact, folded proteins have a full complement of amide carbonyl groups; both observations contradict the cyclol hypothesis that such carbonyls are converted to hydroxyl groups in folded proteins. Finally, proteins were known to contain

The cyclol fabric was shown to be implausible for several reasons. Hans Neurath and Henry Bull showed that the dense packing of side chains in the cyclol fabric was inconsistent with the experimental density observed in protein films. Maurice Huggins calculated that several non-bonded atoms of the cyclol fabric would approach more closely than allowed by their van der Waals radii; for example, the inner Hα and Cα atoms of the lacunae would be separated by only 1.68 Å (Figure 5). Haurowitz showed chemically that the outside of proteins could not have a large number of hydroxyl groups, a key prediction of the cyclol model, whereas Meyer and Hohenemser showed that cyclol condensations of amino acids did not exist even in minute quantities as a transition state. More general chemical arguments against the cyclol model were given by Bergmann and Niemann and by Neuberger. Infrared spectroscopic data showed that the number of carbonyl groups in a protein did not change upon hydrolysis, and that intact, folded proteins have a full complement of amide carbonyl groups; both observations contradict the cyclol hypothesis that such carbonyls are converted to hydroxyl groups in folded proteins. Finally, proteins were known to contain

The downfall of the overall cyclol model generally led to a rejection of its elements; one notable exception was

The downfall of the overall cyclol model generally led to a rejection of its elements; one notable exception was

The cyclol hypothesis is the now discredited first structural model of a folded,

The cyclol hypothesis is the now discredited first structural model of a folded, globular

A globular cluster is a spheroidal conglomeration of stars. Globular clusters are bound together by gravity, with a higher concentration of stars towards their centers. They can contain anywhere from tens of thousands to many millions of membe ...

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, res ...

, formulated in the 1930s. It was based on the cyclol reaction of peptide bonds proposed by physicist Frederick Frank in 1936, in which two peptide groups are chemically crosslinked. These crosslinks are covalent analogs of the non-covalent hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (or H-bond) is a primarily electrostatic force of attraction between a hydrogen (H) atom which is covalently bound to a more electronegative "donor" atom or group (Dn), and another electronegative atom bearing a l ...

s between peptide groups and have been observed in rare cases, such as the ergopeptides.

Based on this reaction, mathematician Dorothy Wrinch

Dorothy Maud Wrinch (12 September 1894 – 11 February 1976; married names Nicholson, Glaser) was a mathematician and biochemical theorist best known for her attempt to deduce protein structure using mathematical principles. She was a champion o ...

hypothesized in a series of five papers in the late 1930s a structural model of globular proteins. She postulated that, under some conditions, amino acids will spontaneously make the maximum possible number of cyclol crosslinks, resulting in cyclol molecules and cyclol fabrics. She further proposed that globular proteins have a tertiary structure

Protein tertiary structure is the three dimensional shape of a protein. The tertiary structure will have a single polypeptide chain "backbone" with one or more protein secondary structures, the protein domains. Amino acid side chains may i ...

corresponding to Platonic solid

In geometry, a Platonic solid is a convex, regular polyhedron in three-dimensional Euclidean space. Being a regular polyhedron means that the faces are congruent (identical in shape and size) regular polygons (all angles congruent and all e ...

s and semiregular polyhedra formed of cyclol fabrics with no free edges. In contrast to the cyclol reaction itself, these hypothetical molecules, fabrics and polyhedra have not been observed experimentally. The model has several consequences that render it energetically implausible, such as steric clashes between the protein sidechains. In response to such criticisms J. D. Bernal

John Desmond Bernal (; 10 May 1901 – 15 September 1971) was an Irish scientist who pioneered the use of X-ray crystallography in molecular biology. He published extensively on the history of science. In addition, Bernal wrote popular book ...

proposed that hydrophobic interaction

In chemistry, hydrophobicity is the physical property of a molecule that is seemingly repelled from a mass of water (known as a hydrophobe). In contrast, hydrophiles are attracted to water.

Hydrophobic molecules tend to be nonpolar and, t ...

s are chiefly responsible for protein folding

Protein folding is the physical process by which a protein chain is translated to its native three-dimensional structure, typically a "folded" conformation by which the protein becomes biologically functional. Via an expeditious and reproduc ...

, which was indeed borne out.

Historical context

By the mid-1930s,analytical ultracentrifugation Analytical ultracentrifugation is an analytical technique which combines an ultracentrifuge with optical monitoring systems.

In an analytical ultracentrifuge (commonly abbreviated as AUC), a sample’s sedimentation profile is monitored in real tim ...

studies by Theodor Svedberg

Theodor Svedberg (30 August 1884 – 25 February 1971) was a Swedish chemist and Nobel laureate for his research on colloids and proteins using the ultracentrifuge. Svedberg was active at Uppsala University from the mid 1900s to late 1940s. ...

had shown that proteins had a well-defined chemical structure, and were not aggregations of small molecules. The same studies appeared to show that the molecular weight of proteins fell into a few well-defined classes related by integers, such as ''M''''w'' = 2''p''3''q'' Da, where ''p'' and ''q'' are nonnegative integers. However, it was difficult to determine the exact molecular weight and number of amino acids in a protein. Svedberg had also shown that a change in solution conditions could cause a protein to disassemble into small subunits, now known as a change in quaternary structure

Protein quaternary structure is the fourth (and highest) classification level of protein structure. Protein quaternary structure refers to the structure of proteins which are themselves composed of two or more smaller protein chains (also refe ...

.

The chemical structure

A chemical structure determination includes a chemist's specifying the molecular geometry and, when feasible and necessary, the electronic structure of the target molecule or other solid. Molecular geometry refers to the spatial arrangement of ...

of protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, res ...

s was still under debate at that time. The most accepted (and ultimately correct) hypothesis was that proteins are linear polypeptide

Peptides (, ) are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Long chains of amino acids are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty amino acids are called oligopeptides, and include dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides.

...

s, i.e., unbranched polymer

A polymer (; Greek '' poly-'', "many" + '' -mer'', "part")

is a substance or material consisting of very large molecules called macromolecules, composed of many repeating subunits. Due to their broad spectrum of properties, both synthetic a ...

s of amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha ...

s linked by peptide bond

In organic chemistry, a peptide bond is an amide type of covalent chemical bond linking two consecutive alpha-amino acids from C1 (carbon number one) of one alpha-amino acid and N2 (nitrogen number two) of another, along a peptide or protein cha ...

s. However, a typical protein is remarkably long—hundreds of amino-acid residues—and several distinguished scientists were unsure whether such long, linear macromolecule

A macromolecule is a very large molecule important to biophysical processes, such as a protein or nucleic acid. It is composed of thousands of covalently bonded atoms. Many macromolecules are polymers of smaller molecules called monomers. The ...

s could be stable in solution. Further doubts about the polypeptide nature of proteins arose because some enzymes

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. ...

were observed to cleave proteins but not peptides, whereas other enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products ...

s cleave peptides but not folded proteins. Attempts to synthesize proteins in the test tube were unsuccessful, mainly due to the chirality

Chirality is a property of asymmetry important in several branches of science. The word ''chirality'' is derived from the Greek (''kheir''), "hand", a familiar chiral object.

An object or a system is ''chiral'' if it is distinguishable from ...

of amino acids; naturally occurring proteins are composed of only ''left-handed'' amino acids. Hence, alternative chemical models of proteins were considered, such as the diketopiperazine hypothesis of Emil Abderhalden

Emil Abderhalden (9 March 1877 – 5 August 1950) was a Swiss biochemist and physiologist. His main findings, though disputed already in the 1910s, were not finally rejected until the late 1990s. Whether his misleading findings were based on fr ...

. However, no alternative model had yet explained why proteins yield only amino acids and peptides upon hydrolysis and proteolysis. As clarified by Linderstrøm-Lang, these proteolysis data showed that denatured proteins were polypeptides, but no data had yet been obtained about the structure of folded proteins; thus, denaturation could involve a chemical change that converted folded proteins into polypeptides.

The process of protein denaturation (as distinguished from coagulation

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a blood clot. It potentially results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The mechanism ...

) had been discovered in 1910 by Harriette Chick

Dame Harriette Chick DBE (6 January 1875 – 9 July 1977) was a British microbiologist, protein scientist and nutritionist. She is best remembered for demonstrating the roles of sunlight and cod liver oil in preventing rickets.

Biography ...

and Charles Martin, but its nature was still mysterious. Tim Anson and Alfred Mirsky

Alfred Ezra Mirsky (October 17, 1900 – June 19, 1974) was an American pioneer in molecular biology.

Mirsky graduated from Harvard College in 1922, after which he studied for two years at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeon ...

had shown that denaturation was a ''reversible, two-state process'' that results in many chemical groups becoming available for chemical reactions, including cleavage by enzymes. In 1929, Hsien Wu hypothesized correctly that denaturation corresponded to protein unfolding, a purely conformational change that resulted in the exposure of amino-acid side chains to the solvent. Wu's hypothesis was also advanced independently in 1936 by Mirsky and Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling (; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist, biochemist, chemical engineer, peace activist, author, and educator. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topi ...

. Nevertheless, protein scientists could not exclude the possibility that denaturation corresponded to a ''chemical'' change in the protein structure, a hypothesis that was considered a (distant) possibility until the 1950s.

X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angles ...

had just begun as a discipline in 1911, and had advanced relatively rapidly from simple salt crystals to crystals of complex molecules such as cholesterol

Cholesterol is any of a class of certain organic molecules called lipids. It is a sterol (or modified steroid), a type of lipid. Cholesterol is biosynthesized by all animal cells and is an essential structural component of animal cell memb ...

. However, even the smallest proteins have over 1000 atoms, which makes determining their structure far more complex. In 1934, Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin had taken crystallographic data on the structure of the small protein, insulin

Insulin (, from Latin ''insula'', 'island') is a peptide hormone produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets encoded in humans by the ''INS'' gene. It is considered to be the main anabolic hormone of the body. It regulates the metabolism ...

, although the structure of that and other proteins were not solved until the late 1960s.; ; ; However, pioneering X-ray

An X-ray, or, much less commonly, X-radiation, is a penetrating form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation. Most X-rays have a wavelength ranging from 10 picometers to 10 nanometers, corresponding to frequencies in the range 30&nb ...

fiber diffraction

Fiber diffraction is a subarea of scattering, an area in which molecular structure is determined from scattering data (usually of X-rays, electrons or neutrons). In fiber diffraction the scattering pattern does not change, as the sample is rotat ...

data had been collected in the early 1930s for many natural fibrous protein

In molecular biology, fibrous proteins or scleroproteins are one of the three main classifications of protein structure (alongside globular and membrane proteins). Fibrous proteins are made up of elongated or fibrous polypeptide chains which fo ...

s such as wool and hair by William Astbury

William Thomas Astbury FRS (25 February 1898 – 4 June 1961) was an English physicist and molecular biologist who made pioneering X-ray diffraction studies of biological molecules. His work on keratin provided the foundation for Linus Pauling ...

, who suggested that "globular proteins in general might be folded from elements essentially like the elements of fibrous proteins."

Since protein structure

Protein structure is the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in an amino acid-chain molecule. Proteins are polymers specifically polypeptides formed from sequences of amino acids, the monomers of the polymer. A single amino acid monom ...

was so poorly understood in the 1930s, the physical interactions responsible for stabilizing that structure were likewise unknown. Astbury Astbury is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Andrew Astbury, English swimmer

* Ian Astbury, English rock singer

* Jill Astbury, Australian researcher into violence against women

* William Astbury, English physicist and molecular ...

hypothesized that the structure of fibrous protein

In molecular biology, fibrous proteins or scleroproteins are one of the three main classifications of protein structure (alongside globular and membrane proteins). Fibrous proteins are made up of elongated or fibrous polypeptide chains which fo ...

s was stabilized by hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (or H-bond) is a primarily electrostatic force of attraction between a hydrogen (H) atom which is covalently bound to a more electronegative "donor" atom or group (Dn), and another electronegative atom bearing a l ...

s in β-sheets. The idea that globular protein

In biochemistry, globular proteins or spheroproteins are spherical ("globe-like") proteins and are one of the common protein types (the others being fibrous, disordered and membrane proteins). Globular proteins are somewhat water-soluble (for ...

s are also stabilized by hydrogen bonds was proposed by Dorothy Jordan Lloyd in 1932, and championed later by Alfred Mirsky

Alfred Ezra Mirsky (October 17, 1900 – June 19, 1974) was an American pioneer in molecular biology.

Mirsky graduated from Harvard College in 1922, after which he studied for two years at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeon ...

and Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling (; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist, biochemist, chemical engineer, peace activist, author, and educator. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topi ...

. At a 1933 lecture by Astbury to the Oxford Junior Scientific Society, physicist Frederick Frank suggested that the fibrous protein α-keratin might be stabilized by an alternative mechanism, namely, ''covalent'' crosslinking of the peptide bond

In organic chemistry, a peptide bond is an amide type of covalent chemical bond linking two consecutive alpha-amino acids from C1 (carbon number one) of one alpha-amino acid and N2 (nitrogen number two) of another, along a peptide or protein cha ...

s by the cyclol reaction above. The cyclol crosslink draws the two peptide groups close together; the N and C atoms are separated by ~1.5 Å, whereas they are separated by ~3 Å in a typical hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (or H-bond) is a primarily electrostatic force of attraction between a hydrogen (H) atom which is covalently bound to a more electronegative "donor" atom or group (Dn), and another electronegative atom bearing a l ...

. The idea intrigued J. D. Bernal

John Desmond Bernal (; 10 May 1901 – 15 September 1971) was an Irish scientist who pioneered the use of X-ray crystallography in molecular biology. He published extensively on the history of science. In addition, Bernal wrote popular book ...

, who suggested it to the mathematician Dorothy Wrinch

Dorothy Maud Wrinch (12 September 1894 – 11 February 1976; married names Nicholson, Glaser) was a mathematician and biochemical theorist best known for her attempt to deduce protein structure using mathematical principles. She was a champion o ...

as possibly useful in understanding protein structure.

Basic theory

Wrinch developed this suggestion into a full-fledged model of

Wrinch developed this suggestion into a full-fledged model of protein structure

Protein structure is the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in an amino acid-chain molecule. Proteins are polymers specifically polypeptides formed from sequences of amino acids, the monomers of the polymer. A single amino acid monom ...

. The basic cyclol model was laid out in her first paper (1936). She noted the possibility that polypeptide

Peptides (, ) are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Long chains of amino acids are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty amino acids are called oligopeptides, and include dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides.

...

s might cyclize to form closed rings (true

True most commonly refers to truth, the state of being in congruence with fact or reality.

True may also refer to:

Places

* True, West Virginia, an unincorporated community in the United States

* True, Wisconsin, a town in the United States

* ...

) and that these rings might form internal crosslinks through the cyclol reaction (also true, although rare). Assuming that the cyclol form of the peptide bond

In organic chemistry, a peptide bond is an amide type of covalent chemical bond linking two consecutive alpha-amino acids from C1 (carbon number one) of one alpha-amino acid and N2 (nitrogen number two) of another, along a peptide or protein cha ...

could be more stable than the amide form, Wrinch concluded that certain cyclic peptide

Peptides (, ) are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Long chains of amino acids are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty amino acids are called oligopeptides, and include dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides. ...

s would naturally make the maximal number of cyclol bonds (such as cyclol 6, Figure 2). Such cyclol molecules would have hexagonal symmetry, if the chemical bond

A chemical bond is a lasting attraction between atoms or ions that enables the formation of molecules and crystals. The bond may result from the electrostatic force between oppositely charged ions as in ionic bonds, or through the sharing of ...

s were taken as having the same length, roughly 1.5 Å; for comparison, the N-C and C-C bonds have the lengths 1.42 Å and 1.54 Å, respectively.

These rings can be extended indefinitely to form a cyclol fabric (Figure 3). Such fabrics exhibit a long-range, quasi-crystalline order that Wrinch felt was likely in proteins, since they must pack hundreds of residues densely. Another interesting feature of such molecules and fabrics is that their amino-acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha ami ...

side chains point axially upwards from only one face; the opposite face has no side chains. Thus, one face is completely independent of the primary sequence

Biomolecular structure is the intricate folded, three-dimensional shape that is formed by a molecule of protein, DNA, or RNA, and that is important to its function. The structure of these molecules may be considered at any of several length ...

of the peptide, which Wrinch conjectured might account for sequence-independent properties of proteins.

In her initial article, Wrinch stated clearly that the cyclol model was merely a ''working hypothesis'', a potentially valid model of proteins that would have to be checked. Her goals in this article and its successors were to propose a well-defined testable model, to work out the consequences of its assumptions and to make predictions that could be tested experimentally. In these goals, she succeeded; however, within a few years, experiments and further modeling showed that the cyclol hypothesis was untenable as a model for globular proteins.

Stabilizing energies

In two tandem Letters to the Editor (1936), Wrinch and Frank addressed the question of whether the cyclol form of the peptide group was indeed more stable than the amide form. A relatively simple calculation showed that the cyclol form is significantly ''less'' stable than the amide form. Therefore, the cyclol model would have to be abandoned unless a compensating source of energy could be identified. Initially, Frank proposed that the cyclol form might be stabilized by better interactions with the surrounding solvent; later, Wrinch and

In two tandem Letters to the Editor (1936), Wrinch and Frank addressed the question of whether the cyclol form of the peptide group was indeed more stable than the amide form. A relatively simple calculation showed that the cyclol form is significantly ''less'' stable than the amide form. Therefore, the cyclol model would have to be abandoned unless a compensating source of energy could be identified. Initially, Frank proposed that the cyclol form might be stabilized by better interactions with the surrounding solvent; later, Wrinch and Irving Langmuir

Irving Langmuir (; January 31, 1881 – August 16, 1957) was an American chemist, physicist, and engineer. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1932 for his work in surface chemistry.

Langmuir's most famous publication is the 1919 ar ...

hypothesized that hydrophobic association of nonpolar sidechains provides stabilizing energy to overcome the energetic cost of the cyclol reactions.

The lability of the cyclol bond was seen as an ''advantage'' of the model, since it provided a natural explanation for the properties of denaturation; reversion of cyclol bonds to their more stable amide form would open up the structure and allows those bonds to be attacked by protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalyzes (increases reaction rate or "speeds up") proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the ...

s, consistent with experiment. Early studies showed that proteins denatured by pressure

Pressure (symbol: ''p'' or ''P'') is the force applied perpendicular to the surface of an object per unit area over which that force is distributed. Gauge pressure (also spelled ''gage'' pressure)The preferred spelling varies by country a ...

are often in a different state than the same proteins denatured by high temperature

Temperature is a physical quantity that expresses quantitatively the perceptions of hotness and coldness. Temperature is measured with a thermometer.

Thermometers are calibrated in various temperature scales that historically have relied o ...

, which was interpreted as possibly supporting the cyclol model of denaturation.

The Langmuir-Wrinch hypothesis of hydrophobic stabilization shared in the downfall of the cyclol model, owing mainly to the influence of Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling (; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist, biochemist, chemical engineer, peace activist, author, and educator. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topi ...

, who favored the hypothesis that protein structure was stabilized by hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (or H-bond) is a primarily electrostatic force of attraction between a hydrogen (H) atom which is covalently bound to a more electronegative "donor" atom or group (Dn), and another electronegative atom bearing a l ...

s. Another twenty years had to pass before hydrophobic interactions were recognized as the chief driving force in protein folding.

Steric complementarity

In her third paper on cyclols (1936), Wrinch noted that many "physiologically active" substances such assteroid

A steroid is a biologically active organic compound with four rings arranged in a specific molecular configuration. Steroids have two principal biological functions: as important components of cell membranes that alter membrane fluidity; and ...

s are composed of fused hexagonal rings of carbon atoms and, thus, might be sterically complementary to the face of cyclol molecules without the amino-acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha ami ...

side chains. Wrinch proposed that steric complementarity was one of chief factors in determining whether a small molecule would bind to a protein.

Wrinch speculated that proteins are responsible for the synthesis of all biological molecules. Noting that cells digest their proteins only under extreme starvation conditions, Wrinch further speculated that life could not exist without proteins.

Hybrid models

From the beginning, the cyclol reaction was considered as a covalent analog of thehydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (or H-bond) is a primarily electrostatic force of attraction between a hydrogen (H) atom which is covalently bound to a more electronegative "donor" atom or group (Dn), and another electronegative atom bearing a l ...

. Therefore, it was natural to consider hybrid models with both types of bonds. This was the subject of Wrinch's fourth paper on the cyclol model (1936), written together with Dorothy Jordan Lloyd, who first proposed that globular proteins are stabilized by hydrogen bonds. A follow-up paper was written in 1937 that referenced other researchers on hydrogen bonding in proteins, such as Maurice Loyal Huggins and Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling (; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist, biochemist, chemical engineer, peace activist, author, and educator. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topi ...

.

Wrinch also wrote a paper with William Astbury

William Thomas Astbury FRS (25 February 1898 – 4 June 1961) was an English physicist and molecular biologist who made pioneering X-ray diffraction studies of biological molecules. His work on keratin provided the foundation for Linus Pauling ...

, noting the possibility of a keto-enol isomerization of the >CαHα and an amide carbonyl group >C=O, producing a crosslink >Cα-C(OHα)< and again converting the oxygen to a hydroxyl group. Such reactions could yield five-membered rings, whereas the classic cyclol hypothesis produces six-membered rings. This keto-enol crosslink hypothesis was not developed much further.

Space-enclosing fabrics

In her fifth paper on cyclols (1937), Wrinch identified the conditions under which two planar cyclol fabrics could be joined to make an angle between their planes while respecting the chemical bond angles. She identified a mathematical simplification, in which the non-planar six-membered rings of atoms can be represented by planar "median hexagon"s made from the midpoints of the chemical bonds. This "median hexagon" representation made it easy to see that the cyclol fabric planes can be joined correctly if the

In her fifth paper on cyclols (1937), Wrinch identified the conditions under which two planar cyclol fabrics could be joined to make an angle between their planes while respecting the chemical bond angles. She identified a mathematical simplification, in which the non-planar six-membered rings of atoms can be represented by planar "median hexagon"s made from the midpoints of the chemical bonds. This "median hexagon" representation made it easy to see that the cyclol fabric planes can be joined correctly if the dihedral angle

A dihedral angle is the angle between two intersecting planes or half-planes. In chemistry, it is the clockwise angle between half-planes through two sets of three atoms, having two atoms in common. In solid geometry, it is defined as the un ...

between the planes equals the tetrahedral bond angle δ = arccos(-1/3) ≈ 109.47°.

A large variety of closed polyhedra meeting this criterion can be constructed, of which the simplest are the truncated tetrahedron, the truncated octahedron

In geometry, the truncated octahedron is the Archimedean solid that arises from a regular octahedron by removing six pyramids, one at each of the octahedron's vertices. The truncated octahedron has 14 faces (8 regular hexagons and 6 squares), 36 ...

, and the octahedron

In geometry, an octahedron (plural: octahedra, octahedrons) is a polyhedron with eight faces. The term is most commonly used to refer to the regular octahedron, a Platonic solid composed of eight equilateral triangles, four of which meet at ea ...

, which are Platonic solid

In geometry, a Platonic solid is a convex, regular polyhedron in three-dimensional Euclidean space. Being a regular polyhedron means that the faces are congruent (identical in shape and size) regular polygons (all angles congruent and all e ...

s or semiregular polyhedra. Considering the first series of "closed cyclols" (those modeled on the truncated tetrahedron), Wrinch showed that their number of amino acids increased quadratically as 72''n''2, where ''n'' is the index of the closed cyclol ''Cn''. Thus, the ''C1'' cyclol has 72 residues, the ''C2'' cyclol has 288 residues, etc. Preliminary experimental support for this prediction came from Max Bergmann and Carl Niemann

Carl George Niemann (July 6, 1908 – April 29, 1964) was an American biochemist who worked extensively on the chemistry and structure of proteins, publishing over 260 research papers. He is known, with Max Bergmann, for proposing the Bergmann-Nie ...

, whose amino-acid analyses suggested that proteins were composed of integer multiples of 288 amino-acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha ami ...

residues (''n''=2). More generally, the cyclol model of globular proteins accounted for the early analytical ultracentrifugation Analytical ultracentrifugation is an analytical technique which combines an ultracentrifuge with optical monitoring systems.

In an analytical ultracentrifuge (commonly abbreviated as AUC), a sample’s sedimentation profile is monitored in real tim ...

results of Theodor Svedberg

Theodor Svedberg (30 August 1884 – 25 February 1971) was a Swedish chemist and Nobel laureate for his research on colloids and proteins using the ultracentrifuge. Svedberg was active at Uppsala University from the mid 1900s to late 1940s. ...

, which suggested that the molecular weight

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bio ...

s of proteins fell into a few classes related by integers.

The cyclol model was consistent with the general properties then attributed to folded proteins. (1) Centrifugation studies had shown that folded proteins were significantly denser than water (~1.4 g/ mL) and, thus, tightly packed; Wrinch assumed that dense packing should imply ''regular'' packing. (2) Despite their large size, some proteins crystallize readily into symmetric crystals, consistent with the idea of symmetric faces that match up upon association. (3) Proteins bind metal ions; since metal-binding sites must have specific bond geometries (e.g., octahedral), it was plausible to assume that the entire protein also had similarly crystalline geometry. (4) As described above, the cyclol model provided a simple ''chemical'' explanation of denaturation and the difficulty of cleaving folded proteins with proteases. (5) Proteins were assumed to be responsible for the synthesis of all biological molecules, including other proteins. Wrinch noted that a fixed, uniform structure would be useful for proteins in templating their own synthesis, analogous to the Watson

Watson may refer to:

Companies

* Actavis, a pharmaceutical company formerly known as Watson Pharmaceuticals

* A.S. Watson Group, retail division of Hutchison Whampoa

* Thomas J. Watson Research Center, IBM research center

* Watson Systems, make ...

-Francis Crick

Francis Harry Compton Crick (8 June 1916 – 28 July 2004) was an English molecular biologist, biophysicist, and neuroscientist. He, James Watson, Rosalind Franklin, and Maurice Wilkins played crucial roles in deciphering the helical stru ...

concept of DNA templating its own replication. Given that many biological molecules such as sugars

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or double ...

and sterol

Sterol is an organic compound with formula , whose molecule is derived from that of gonane by replacement of a hydrogen atom in position 3 by a hydroxyl group. It is therefore an alcohol of gonane. More generally, any compounds that contain the go ...

s have a hexagonal structure, it was plausible to assume that their synthesizing proteins likewise had a hexagonal structure. Wrinch summarized her model and the supporting molecular-weight experimental data in three review articles.

Predicted protein structures

Having proposed a model of globular proteins, Wrinch investigated whether it was consistent with the available structural data. She hypothesized that bovine tuberculin protein (523) was a ''C1'' closed cyclol consisting of 72 residues and that the digestiveenzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products ...

pepsin

Pepsin is an endopeptidase that breaks down proteins into smaller peptides. It is produced in the gastric chief cells of the stomach lining and is one of the main digestive enzymes in the digestive systems of humans and many other animals, w ...

was a ''C2'' closed cyclol of 288 residues. These residue-number predictions were difficult to verify, since the methods then available to measure the mass of proteins were inaccurate, such as analytical ultracentrifugation Analytical ultracentrifugation is an analytical technique which combines an ultracentrifuge with optical monitoring systems.

In an analytical ultracentrifuge (commonly abbreviated as AUC), a sample’s sedimentation profile is monitored in real tim ...

and chemical methods.

Wrinch also predicted that insulin

Insulin (, from Latin ''insula'', 'island') is a peptide hormone produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets encoded in humans by the ''INS'' gene. It is considered to be the main anabolic hormone of the body. It regulates the metabolism ...

was a ''C2'' closed cyclol consisting of 288 residues. Limited X-ray crystallographic data were available for insulin which Wrinch interpreted as "confirming" her model. However, this interpretation drew rather severe criticism for being premature. Careful studies of the Patterson diagrams of insulin taken by Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin showed that they were roughly consistent with the cyclol model; however, the agreement was not good enough to claim that the cyclol model was confirmed.

Implausibility of the model

The cyclol fabric was shown to be implausible for several reasons. Hans Neurath and Henry Bull showed that the dense packing of side chains in the cyclol fabric was inconsistent with the experimental density observed in protein films. Maurice Huggins calculated that several non-bonded atoms of the cyclol fabric would approach more closely than allowed by their van der Waals radii; for example, the inner Hα and Cα atoms of the lacunae would be separated by only 1.68 Å (Figure 5). Haurowitz showed chemically that the outside of proteins could not have a large number of hydroxyl groups, a key prediction of the cyclol model, whereas Meyer and Hohenemser showed that cyclol condensations of amino acids did not exist even in minute quantities as a transition state. More general chemical arguments against the cyclol model were given by Bergmann and Niemann and by Neuberger. Infrared spectroscopic data showed that the number of carbonyl groups in a protein did not change upon hydrolysis, and that intact, folded proteins have a full complement of amide carbonyl groups; both observations contradict the cyclol hypothesis that such carbonyls are converted to hydroxyl groups in folded proteins. Finally, proteins were known to contain

The cyclol fabric was shown to be implausible for several reasons. Hans Neurath and Henry Bull showed that the dense packing of side chains in the cyclol fabric was inconsistent with the experimental density observed in protein films. Maurice Huggins calculated that several non-bonded atoms of the cyclol fabric would approach more closely than allowed by their van der Waals radii; for example, the inner Hα and Cα atoms of the lacunae would be separated by only 1.68 Å (Figure 5). Haurowitz showed chemically that the outside of proteins could not have a large number of hydroxyl groups, a key prediction of the cyclol model, whereas Meyer and Hohenemser showed that cyclol condensations of amino acids did not exist even in minute quantities as a transition state. More general chemical arguments against the cyclol model were given by Bergmann and Niemann and by Neuberger. Infrared spectroscopic data showed that the number of carbonyl groups in a protein did not change upon hydrolysis, and that intact, folded proteins have a full complement of amide carbonyl groups; both observations contradict the cyclol hypothesis that such carbonyls are converted to hydroxyl groups in folded proteins. Finally, proteins were known to contain proline

Proline (symbol Pro or P) is an organic acid classed as a proteinogenic amino acid (used in the biosynthesis of proteins), although it does not contain the amino group but is rather a secondary amine. The secondary amine nitrogen is in the p ...

in significant quantities (typically 5%); since proline lacks the amide hydrogen and its nitrogen already forms three covalent bonds, proline seems incapable of the cyclol reaction and of being incorporated into a cyclol fabric. An encyclopedic summary of the chemical and structural evidence against the cyclol model was given by Pauling and Niemann. Moreover, a supporting piece of evidence—the result that all proteins contain an integer multiple of 288 amino-acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha ami ...

residues—was likewise shown to be incorrect in 1939.

Wrinch replied to the steric-clash, free-energy, chemical and residue-number criticisms of the cyclol model. On steric clashes, she noted that small deformations of the bond angles and bond lengths would allow these steric clashes to be relieved, or at least reduced to a reasonable level. She noted that distances between non-bonded groups within a single molecule can be shorter than expected from their van der Waals radii, e.g., the 2.93 Å distance between methyl groups in hexamethylbenzene. Regarding the free-energy penalty for the cyclol reaction, Wrinch disagreed with Pauling's calculations and stated that too little was known of intramolecular energies to rule out the cyclol model on that basis alone. In reply to the chemical criticisms, Wrinch suggested that the model compounds and simple bimolecular reactions studied need not pertain to the cyclol model, and that steric hindrance may have prevented the surface hydroxyl groups from reacting. On the residue-number criticism, Wrinch extended her model to allow for other numbers of residues. In particular, she produced a "minimal" closed cyclol of only 48 residues, and, on that (incorrect) basis, may have been the first to suggest that the insulin

Insulin (, from Latin ''insula'', 'island') is a peptide hormone produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets encoded in humans by the ''INS'' gene. It is considered to be the main anabolic hormone of the body. It regulates the metabolism ...

monomer had a molecular weight of roughly 6000 Da.

Therefore, she maintained that the cyclol model of globular proteins was still potentially viable and even proposed the cyclol fabric as a component of the cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton is a complex, dynamic network of interlinking protein filaments present in the cytoplasm of all cells, including those of bacteria and archaea. In eukaryotes, it extends from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane and is co ...

. However, most protein scientists ceased to believe in it and Wrinch turned her scientific attention to mathematical problems in X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angles ...

, to which she contributed significantly. One exception was physicist Gladys Anslow

Gladys Amelia Anslow (May 22, 1892 – March 31, 1969) was an American physicist who spent her career at Smith College. She was the first woman to work with the cyclotron.

Early life and education

Born in Springfield, Massachusetts, Anslow ...

, Wrinch's colleague at Smith College

Smith College is a private liberal arts women's college in Northampton, Massachusetts. It was chartered in 1871 by Sophia Smith and opened in 1875. It is the largest member of the historic Seven Sisters colleges, a group of elite women's coll ...

, who studied the ultraviolet

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation ...

absorption

Absorption may refer to:

Chemistry and biology

*Absorption (biology), digestion

**Absorption (small intestine)

*Absorption (chemistry), diffusion of particles of gas or liquid into liquid or solid materials

*Absorption (skin), a route by which s ...

spectra of proteins and peptides in the 1940s and allowed for the possibility of cyclols in interpreting her results. As the sequence

In mathematics, a sequence is an enumerated collection of objects in which repetitions are allowed and order matters. Like a set, it contains members (also called ''elements'', or ''terms''). The number of elements (possibly infinite) is called ...

of insulin began to be determined by Frederick Sanger

Frederick Sanger (; 13 August 1918 – 19 November 2013) was an English biochemist who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry twice.

He won the 1958 Chemistry Prize for determining the amino acid sequence of insulin and numerous other p ...

, Anslow published a three-dimensional cyclol model with sidechains, based on the backbone of Wrinch's 1948 "minimal cyclol" model.

Partial redemption

The downfall of the overall cyclol model generally led to a rejection of its elements; one notable exception was

The downfall of the overall cyclol model generally led to a rejection of its elements; one notable exception was J. D. Bernal

John Desmond Bernal (; 10 May 1901 – 15 September 1971) was an Irish scientist who pioneered the use of X-ray crystallography in molecular biology. He published extensively on the history of science. In addition, Bernal wrote popular book ...

's short-lived acceptance of the Langmuir-Wrinch hypothesis that protein folding

Protein folding is the physical process by which a protein chain is translated to its native three-dimensional structure, typically a "folded" conformation by which the protein becomes biologically functional. Via an expeditious and reproduc ...

is driven by hydrophobic association. Nevertheless, cyclol bonds were identified in small, naturally occurring cyclic peptide

Cyclic peptides are polypeptide chains which contain a circular sequence of bonds. This can be through a connection between the amino and carboxyl ends of the peptide, for example in cyclosporin; a connection between the amino end and a side chai ...

s in the 1950s.

Clarification of the modern terminology is appropriate. The classic cyclol reaction is the addition of the NH amine of a peptide group to the C=O carbonyl group of another; the resulting compound is now called an azacyclol. By analogy, an oxacyclol is formed when an OH hydroxyl group is added to a peptidyl carbonyl group. Likewise, a thiacyclol is formed by adding an SH thiol moiety to a peptidyl carbonyl group.Wieland T and Bodanszky M, ''The World of Peptides'', Springer Verlag, pp.193–198.

The oxacyclol alkaloid

Alkaloids are a class of basic, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. This group also includes some related compounds with neutral and even weakly acidic properties. Some synthetic compounds of simila ...

ergotamine

Ergotamine, sold under the brand names Cafergot (with caffeine) and Ergomar among others, is an ergopeptine and part of the ergot family of alkaloids; it is structurally and biochemically closely related to ergoline. It possesses structural sim ...

from the fungus

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately fr ...

''Claviceps purpurea'' was the first identified cyclol. The cyclic depsipeptide serratamolide is also formed by an oxacyclol reaction. Chemically analogous cyclic thiacyclols have also been obtained. Classic azacyclols have been observed in small molecules and tripeptides. Peptides are naturally produced from the reversion of azacylols, a key prediction of the cyclol model. Hundreds of cyclol molecules have now been identified, despite Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling (; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist, biochemist, chemical engineer, peace activist, author, and educator. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topi ...

's calculation that such molecules should not exist because of their unfavorably high energy

In physics, energy (from Ancient Greek: ἐνέργεια, ''enérgeia'', “activity”) is the quantitative property that is transferred to a body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of work and in the form of ...

.

After a long hiatus during which she worked mainly on the mathematics of X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angles ...

, Wrinch responded to these discoveries with renewed enthusiasm for the cyclol model and its relevance in biochemistry. She also published two books describing the cyclol theory and small peptides in general.

References

Further reading

* * * * * {{refend Protein structure Obsolete scientific theories History of chemistry