criminal conversation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

At

At

At

At common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omnipres ...

, criminal conversation, often abbreviated as ''crim. con.'', is a tort

A tort is a civil wrong that causes a claimant to suffer loss or harm, resulting in legal liability for the person who commits the tortious act. Tort law can be contrasted with criminal law, which deals with criminal wrongs that are punishable ...

arising from adultery

Adultery (from Latin ''adulterium'') is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and legal ...

. "Conversation" is an old euphemism for sexual intercourse that is obsolete except as part of this term.

It is similar to breach of promise

Breach of promise is a common law tort, abolished in many jurisdictions. It was also called breach of contract to marry,N.Y. Civil Rights Act article 8, §§ 80-A to 84. and the remedy awarded was known as heart balm.

From at least the Middle ...

, a tort involving a broken engagement against the betrothed, and alienation of affections

Alienation of affections is a common law tort, abolished in many jurisdictions. Where it still exists, an action is brought by a spouse against a third party alleged to be responsible for damaging the marriage, most often resulting in divorce. The ...

, a tort action brought by a spouse against a third party, who interfered with the marriage relationship. These torts have been abolished in most jurisdictions. The tort of criminal conversation was abolished in England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. The substantive law of the jurisdiction is Eng ...

in 1857; in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

in 1939; in Australia in 1975; and in the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ga, Éire ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 Counties of Ireland, counties of the island of Ireland. The capital and largest city is Dublin, on the eastern ...

in 1981. Prior to its abolition, a husband could sue any man who had intercourse with his wife, regardless of whether she consented – unless the couple was already separated, in which case the husband could only sue if the separation was caused by the person he was suing.

Criminal conversation still exists in parts of the United States, but the application has changed. At least 29 states have abolished the tort by statute and another four have abolished it judicially. The tort of criminal conversation seeks damages for the act of sexual intercourse outside marriage, between the spouse and a third party. Each act of adultery can give rise to a separate claim for criminal conversation.

History

England and Wales

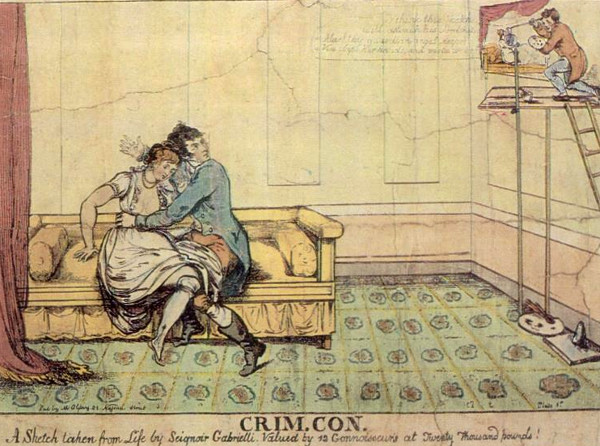

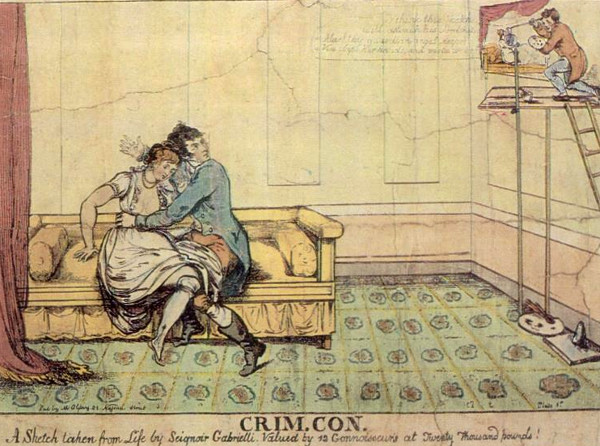

Initially, criminal conversation was an action brought by a husband for compensation for the breach of fidelity with his wife. Only a husband could be the plaintiff, and only the "other man" could be the defendant. Suits for criminal conversation reached their height in late 18th- and early 19th-century England, where large sums, often between £10,000 and £20,000 (worth upwards of £1–2 million in today's terms), could be demanded by the plaintiff for the debauching of his wife. These suits were conducted at the Court of the King's Bench inWestminster Hall

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north bank ...

, and were highly publicised by publishers such as Edmund Curll

Edmund Curll (''c.'' 1675 – 11 December 1747) was an English bookseller and publisher. His name has become synonymous, through the attacks on him by Alexander Pope, with unscrupulous publication and publicity. Curll rose from poverty to wealt ...

and in the newspapers of the day. Although neither the plaintiff

A plaintiff ( Π in legal shorthand) is the party who initiates a lawsuit (also known as an ''action'') before a court. By doing so, the plaintiff seeks a legal remedy. If this search is successful, the court will issue judgment in favor of t ...

, defendant, nor the wife accused of the adultery was permitted to take the stand, evidence of the adulterous behaviour was presented by servants or observers.

A number of sensational cases involving members of the aristocracy gained public notoriety in this period. In the 1769 case of ''Grosvenor v Cumberland'', Lord Grosvenor sued the King's brother, the Duke of Cumberland

Duke of Cumberland is a peerage title that was conferred upon junior members of the British Royal Family, named after the historic county of Cumberland.

History

The Earldom of Cumberland, created in 1525, became extinct in 1643. The dukedom ...

, for criminal conversation with his wife, and was awarded damages of £10,000. In the 1782 case of ''Worsley v Bisset'', Sir Richard Worsley won a technical victory against George Bisset, but was awarded the derisory sum of only one shilling damages: the fact of adultery was not contested, but it was found that he had colluded in his own dishonour by showing his friend his wife, Seymour Dorothy Fleming

Seymour Dorothy Fleming (5 October 1758 – 9 September 1818), styled Lady Worsley from 1775 to 1805, was a member of the British gentry, notable for her involvement in a high-profile criminal conversation trial.

Early life and family

Fleming ...

, naked in a bath-house. In 1796, the Earl of Westmeath

Earl of Westmeath is a title in the Peerage of Ireland. It was created in 1621 for Richard Nugent, Baron Delvin. During the Tudor era the loyalty of the Nugent family was often in question, and Richard's father, the sixth Baron, died in prison ...

was awarded £10,000 against his wife's lover, Augustus Cavendish-Bradshaw

Hon. Augustus Cavendish Bradshaw (17 February 1768 – 11 November 1832), of Putney, Surrey and High Elms, near Watford, Hertfordshire, was an English politician, best remembered today for his role as co-respondent in the Westmeath divorce case ...

. In 1807 Lord Cloncurry brought a much-publicized action for criminal conversation against his former friend Sir John Piers, and was awarded damages of £20,000. In 1836, George Chapple Norton

George Chapple Norton (31 August 1800 – 24 February 1875) was a Tory Member of Parliament for Guildford from 1826 to 1830.

He was educated at Winchester College.

He died on 24 February 1875 at Wonersh.

Family

He was born in Wakefield the son ...

sued Lord Melbourne

William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, (15 March 177924 November 1848), in some sources called Henry William Lamb, was a British Whig politician who served as Home Secretary (1830–1834) and Prime Minister (1834 and 1835–1841). His first pre ...

, the Whig Prime Minister, for criminal conversation with his wife, Caroline, who had left him: the jury threw out the claim, but the negative publicity almost brought down the government.

Australia

In the state of New South Wales, the tort of criminal conversation was abolished by section 92 of the Matrimonial Causes Act 1899 (NSW). In the state of Victoria, the tort of criminal conversation was abolished by section 146 of the Marriage Act 1915 (Vic), although that act also provided for a husband to seek damages from a man guilty of adultery with his wife as part of divorce proceedings (sections 147–149). In Tasmania, action for criminal conversation was abolished in 1860 by the Matrimonial Causes Act (24 Vic, No 1), section 50. It was abolished under Commonwealth law by section 44(5) of the Matrimonial Causes Act 1959 (Cth), which was restated by section 120 of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth).Current usage: United States

The tort is still recognized in a number of states in the United States, although it has been abolished either legislatively or judicially in most. The tort has seen particular use inNorth Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and ...

. In the case of ''Cannon v. Miller'', 71 N.C. App. 460, 322 S.E.2d 780 (1984), the North Carolina Court of Appeals

The North Carolina Court of Appeals (in case citation, N.C. Ct. App.) is the only intermediate appellate court in the state of North Carolina. It is composed of fifteen members who sit in rotating panels of three. The Court of Appeals was create ...

(the state's intermediate appellate court

A court of appeals, also called a court of appeal, appellate court, appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to hear an appeal of a trial court or other lower tribunal. In much of ...

) abolished the tort of criminal conversation, as well as the tort of alienation of affections

Alienation of affections is a common law tort, abolished in many jurisdictions. Where it still exists, an action is brought by a spouse against a third party alleged to be responsible for damaging the marriage, most often resulting in divorce. The ...

, in the state. However, the North Carolina Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the State of North Carolina is the state of North Carolina's highest appellate court. Until the creation of the North Carolina Court of Appeals in the 1960s, it was the state's only appellate court. The Supreme Court consists ...

summarily vacated the Court of Appeals' decision shortly thereafter, saying in a brief opinion that the Court of Appeal had improperly sought to overrule earlier decisions of the Supreme Court. ''Cannon v. Miller'', 313 N.C. 324, 327 S.E.2d 888 (1985). In 2009, the General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of presb ...

approved legislation which placed some limits on such lawsuits. The bill was signed into law by Governor Bev Perdue

Beverly Eaves Perdue (born Beverly Marlene Moore; January 14, 1947) is an American businesswoman, politician, and member of the Democratic Party who served as the 73rd governor of North Carolina from 2009 to 2013. She was the first female gov ...

on August 3, 2009, and is codified under Chapter 52 of the North Carolina General Statutes:

Each of the three limitations arose from a recent North Carolina legal case involving the tort. In ''Jones v. Skelley'', 195 N.C. App. 500, 673 S.E.2d 385 (2009), the North Carolina Court of Appeals had held that the tort applies even to legally separated spouses. In ''Misenheimer v. Burris'', 360 N.C. 620, 637 S.E.2d 173 (2006), the North Carolina Supreme Court held that the statute of limitation commences when the affair should have been discovered rather than when it occurred. In ''Smith v. Lee'', 2007 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 78987, the Federal District Court for the Western District of North Carolina noted that the question of whether an employer could be held liable for an affair conducted by an employee on a business trip was still unsettled in North Carolina.

References

Further reading

* * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Criminal Conversation Tort law