conservationism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The conservation movement, also known as nature conservation, is a political, environmental, and social movement that seeks to manage and protect

The conservation movement can be traced back to

The conservation movement can be traced back to

Sir Dietrich Brandis, a

Sir Dietrich Brandis, a

The American movement received its inspiration from 19th century works that exalted the inherent value of nature, quite apart from human usage. Author

The American movement received its inspiration from 19th century works that exalted the inherent value of nature, quite apart from human usage. Author  Roosevelt established the

Roosevelt established the  While Theodore Roosevelt was one of the leading activists for the conservation movement in the United States, he also believed that the threats to the natural world were equally threats to white Americans. They held the belief that the cities, industries and factories that were overtaking the wilderness and threatening the native plants and animals were also consuming and threatening the racial vigor that they believed white Americans held which made them superior. Roosevelt was a big believer that white male virility depended on wildlife for its vigor, and that depleting wildlife would result in a much weaker nation. This lead Roosevelt to support the passing of many immigration restrictions, eugenics legislations and wildlife preservation laws. He drew much inspiration for his beliefs from Madison Grant, a well known American eugenicist and conservationist. Grant worked alongside Roosevelt in the American conservation movement and was even secretary and president of the Boone and Crockett Club. In 1916, Grant published the book "The Passing of the Great Race", which explained the hierarchy of races, with white, "Nordic" men at the top, and all other races below. The German translation of this book was used by Nazi Germany as the source for many of their beliefs.

The National Audubon Society was founded in 1905 with the priority of protecting/conserving various waterbird species. However, the first state-level Audubon group was created in 1896 by Harriet Hemenway and Minna B. Hall to convince women to refrain from buying hats made with bird feathers- a common practice at the time. The organization is named after John Audubon, a naturalist and legendary bird painter. The lesser known truth is that he was a slaveholder who also included many racist tales in his many books. Despite his views of racial inequality, Audubon did find black and indigenous people to be scientifically useful, often using their local knowledge in his books and relying on them to collect specimens for him.

While Theodore Roosevelt was one of the leading activists for the conservation movement in the United States, he also believed that the threats to the natural world were equally threats to white Americans. They held the belief that the cities, industries and factories that were overtaking the wilderness and threatening the native plants and animals were also consuming and threatening the racial vigor that they believed white Americans held which made them superior. Roosevelt was a big believer that white male virility depended on wildlife for its vigor, and that depleting wildlife would result in a much weaker nation. This lead Roosevelt to support the passing of many immigration restrictions, eugenics legislations and wildlife preservation laws. He drew much inspiration for his beliefs from Madison Grant, a well known American eugenicist and conservationist. Grant worked alongside Roosevelt in the American conservation movement and was even secretary and president of the Boone and Crockett Club. In 1916, Grant published the book "The Passing of the Great Race", which explained the hierarchy of races, with white, "Nordic" men at the top, and all other races below. The German translation of this book was used by Nazi Germany as the source for many of their beliefs.

The National Audubon Society was founded in 1905 with the priority of protecting/conserving various waterbird species. However, the first state-level Audubon group was created in 1896 by Harriet Hemenway and Minna B. Hall to convince women to refrain from buying hats made with bird feathers- a common practice at the time. The organization is named after John Audubon, a naturalist and legendary bird painter. The lesser known truth is that he was a slaveholder who also included many racist tales in his many books. Despite his views of racial inequality, Audubon did find black and indigenous people to be scientifically useful, often using their local knowledge in his books and relying on them to collect specimens for him.

online

* Bonhomme, Brian. ''Forests, Peasants and Revolutionaries: Forest Conservation & Organization in Soviet Russia, 1917-1929'' (2005) 252pp. * Cioc, Mark. ''The Rhine: An Eco-Biography, 1815-2000'' (2002). * Dryzek, John S., et al. ''Green states and social movements: environmentalism in the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, and Norway'' (Oxford UP, 2003). * Jehlicka, Petr. "Environmentalism in Europe: an east-west comparison." in ''Social change and political transformation'' (Routledge, 2018) pp. 112–131. * Simmons, I.G. ''An Environmental History of Great Britain: From 10,000 Years Ago to the Present'' (2001). * Uekotter, Frank. ''The greenest nation?: A new history of German environmentalism'' (MIT Press, 2014). * Weiner, Douglas R. ''Models of Nature: Ecology, Conservation and Cultural Revolution in Soviet Russia'' (2000) 324pp; covers 1917 to 1939.

in JSTOR

* Brinkley, Douglas G. ''The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America,'' (2009

excerpt and text search

* Cawley, R. McGreggor. ''Federal Land, Western Anger: The Sagebrush Rebellion and Environmental Politics'' (1993), on conservatives * Flippen, J. Brooks. ''Nixon and the Environment'' (2000). * Hays, Samuel P. ''Beauty, Health, and Permanence: Environmental Politics in the United States, 1955–1985'' (1987), the standard scholarly history ** Hays, Samuel P. ''A History of Environmental Politics since 1945'' (2000), shorter standard history * Hays, Samuel P. ''Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency'' (1959), on Progressive Era. * King, Judson. ''The Conservation Fight, From Theodore Roosevelt to the Tennessee Valley Authority'' (2009) * Nash, Roderick. ''Wilderness and the American Mind,'' (3rd ed. 1982), the standard intellectual history * * Rothmun, Hal K. ''The Greening of a Nation? Environmentalism in the United States since 1945'' (1998) * Scheffer, Victor B. ''The Shaping of Environmentalism in America'' (1991). * Sellers, Christopher. ''Crabgrass Crucible: Suburban Nature and the Rise of Environmentalism in Twentieth-Century America'' (2012) * Strong, Douglas H. ''Dreamers & Defenders: American Conservationists.'' (1988

online edition

good biographical studies of the major leaders * Taylor, Dorceta E. ''The Rise of the American Conservation Movement: Power, Privilege, and Environmental Protection'' (Duke U.P. 2016) x, 486 pp. * Turner, James Morton, "The Specter of Environmentalism": Wilderness, Environmental Politics, and the Evolution of the New Right. ''The Journal of American History'' 96.1 (2009): 123-4

* Vogel, David. ''California Greenin': How the Golden State Became an Environmental Leader'' (2018) 280 pp

online review

excerpt and text search

* McNeill, John R. "Observations on the Nature and Culture of Environmental History," ''History and Theory,'' 42 (2003), pp. 5–43. * Robin, Libby, and Tom Griffiths, "Environmental History in Australasia," ''Environment and History,'' 10 (2004), pp. 439–74 * Worster, Donald, ed. ''The Ends of the Earth: Perspectives on Modern Environmental History'' (1988)

A history of conservation in New Zealand

''For Future Generations'', a Canadian documentary on conservation and national parks

{{DEFAULTSORT:Conservation Movement Environmental conservation Environmental ethics Environmental movements el:Κίνημα Διατήρησης fr:Conservation de la nature sv:Naturskydd

natural resource

Natural resources are resources that are drawn from nature and used with few modifications. This includes the sources of valued characteristics such as commercial and industrial use, aesthetic value, scientific interest and cultural value. ...

s, including animal, fungus, and plant species as well as their habitat for the future. Conservationists are concerned with leaving the environment in a better state than the condition they found it in. Evidence-based conservation

Evidence-based conservation is the application of evidence in nature conservation management actions and policy making. It is defined as systematically assessing scientific information from published, peer-reviewed publications and texts, practiti ...

seeks to use high quality scientific evidence to make conservation efforts more effective.

The early conservation movement evolved out of necessity to maintain natural resources such as fisheries

Fishery can mean either the enterprise of raising or harvesting fish and other aquatic life; or more commonly, the site where such enterprise takes place ( a.k.a. fishing ground). Commercial fisheries include wild fisheries and fish farms, ...

, wildlife management, water

Water (chemical formula ) is an inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms (in which it acts as ...

, soil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth or dirt, is a mixture of organic matter, minerals, gases, liquids, and organisms that together support life. Some scientific definitions distinguish ''dirt'' from ''soil'' by restricting the former ...

, as well as conservation

Conservation is the preservation or efficient use of resources, or the conservation of various quantities under physical laws.

Conservation may also refer to:

Environment and natural resources

* Nature conservation, the protection and manageme ...

and sustainable forestry

Sustainable forest management (SFM) is the management of forests according to the principles of sustainable development. Sustainable forest management has to keep the balance between three main pillars: ecological, economic and socio-cultura ...

. The contemporary conservation movement has broadened from the early movement's emphasis on use of sustainable yield of natural resources and preservation of wilderness areas to include preservation of biodiversity

Biodiversity or biological diversity is the variety and variability of life on Earth. Biodiversity is a measure of variation at the genetic ('' genetic variability''), species ('' species diversity''), and ecosystem ('' ecosystem diversity'') ...

. Some say the conservation movement is part of the broader and more far-reaching environmental movement

The environmental movement (sometimes referred to as the ecology movement), also including conservation and green politics, is a diverse philosophical, social, and political movement for addressing environmental issues. Environmentalists a ...

, while others argue that they differ both in ideology and practice. Conservation is seen as differing from environmentalism

Environmentalism or environmental rights is a broad Philosophy of life, philosophy, ideology, and social movement regarding concerns for environmental protection and improvement of the health of the environment (biophysical), environment, par ...

and it is generally a conservative school of thought which aims to preserve natural resources expressly for their continued sustainable

Specific definitions of sustainability are difficult to agree on and have varied in the literature and over time. The concept of sustainability can be used to guide decisions at the global, national, and individual levels (e.g. sustainable livi ...

use by humans.

History

Early history

The conservation movement can be traced back to

The conservation movement can be traced back to John Evelyn

John Evelyn (31 October 162027 February 1706) was an English writer, landowner, gardener, courtier and minor government official, who is now best known as a diarist. He was a founding Fellow of the Royal Society.

John Evelyn's diary, or m ...

's work '' Sylva'', presented as a paper to the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in 1662. Published as a book two years later, it was one of the most highly influential texts on forestry

Forestry is the science and craft of creating, managing, planting, using, conserving and repairing forests, woodlands, and associated resources for human and environmental benefits. Forestry is practiced in plantations and natural stands. ...

ever published. Timbre resources in England were becoming dangerously depleted at the time, and Evelyn advocated the importance of conserving the forests by managing the rate of depletion and ensuring that the cut down trees get replenished.

The field developed during the 18th century, especially in Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

and France where scientific forestry methods were developed. These methods were first applied rigorously in British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

from the early 19th century. The government was interested in the use of forest produce and began managing the forests with measures to reduce the risk of wildfire in order to protect the "household" of nature, as it was then termed. This early ecological idea was in order to preserve the growth of delicate teak

Teak (''Tectona grandis'') is a tropical hardwood tree species in the family Lamiaceae. It is a large, deciduous tree that occurs in mixed hardwood forests. ''Tectona grandis'' has small, fragrant white flowers arranged in dense clusters ( pan ...

trees, which was an important resource for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

.

Concerns over teak depletion were raised as early as 1799 and 1805 when the Navy was undergoing a massive expansion during the Napoleonic Wars; this pressure led to the first formal conservation Act, which prohibited the felling of small teak trees. The first forestry officer was appointed in 1806 to regulate and preserve the trees necessary for shipbuilding.

This promising start received a setback in the 1820s and 30s, when laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups ...

economics and complaints from private landowners brought these early conservation attempts to an end.

In 1837, American poet George Pope Morris published "Woodman, Spare that Tree!", a Romantic poem urging a lumberjack to avoid an oak tree that has sentimental value. The poem was set to music later that year by Henry Russell. Lines from the song have been quoted by environmentalists.

Origins of the modern conservation movement

Conservation was revived in the mid-19th century, with the first practical application of scientific conservation principles to the forests of India. The conservation ethic that began to evolve included three core principles: that human activity damaged theenvironment

Environment most often refers to:

__NOTOC__

* Natural environment, all living and non-living things occurring naturally

* Biophysical environment, the physical and biological factors along with their chemical interactions that affect an organism or ...

, that there was a civic duty

Civic engagement or civic participation is any individual or group activity addressing issues of public concern. Civic engagement includes communities working together or individuals working alone in both political and non-political actions to ...

to maintain the environment for future generations, and that scientific, empirically based methods should be applied to ensure this duty was carried out. Sir James Ranald Martin was prominent in promoting this ideology, publishing many medico-topographical reports that demonstrated the scale of damage wrought through large-scale deforestation and desiccation, and lobbying extensively for the institutionalization of forest conservation activities in British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

through the establishment of Forest Departments. Edward Percy Stebbing warned of desertification of India. The Madras

Chennai (, ), formerly known as Madras ( the official name until 1996), is the capital city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost Indian state. The largest city of the state in area and population, Chennai is located on the Coromandel Coast of th ...

Board of Revenue started local conservation efforts in 1842, headed by Alexander Gibson, a professional botanist

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek wo ...

who systematically adopted a forest conservation program based on scientific principles. This was the first case of state management of forests in the world.

These local attempts gradually received more attention by the British government as the unregulated felling of trees continued unabated. In 1850, the British Association in Edinburgh formed a committee to study forest destruction at the behest of Dr. Hugh Cleghorn a pioneer in the nascent conservation movement.

He had become interested in forest conservation

Sustainable forest management (SFM) is the management of forests according to the principles of sustainable development. Sustainable forest management has to keep the balance between three main pillars: ecological, economic and socio-cultural. ...

in Mysore

Mysore (), officially Mysuru (), is a city in the southern part of the state of Karnataka, India. Mysore city is geographically located between 12° 18′ 26″ north latitude and 76° 38′ 59″ east longitude. It is located at an altitude o ...

in 1847 and gave several lectures at the Association on the failure of agriculture in India. These lectures influenced the government under Governor-General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

Lord Dalhousie

James Andrew Broun-Ramsay, 1st Marquess of Dalhousie (22 April 1812 – 19 December 1860), also known as Lord Dalhousie, styled Lord Ramsay until 1838 and known as The Earl of Dalhousie between 1838 and 1849, was a Scottish statesman and co ...

to introduce the first permanent and large-scale forest conservation program in the world in 1855, a model that soon spread to other colonies, as well the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

. In the same year, Cleghorn organised the Madras Forest Department and in 1860 the department banned the use shifting cultivation

Shifting cultivation is an agricultural system in which plots of land are cultivated temporarily, then abandoned while post-disturbance fallow vegetation is allowed to freely grow while the cultivator moves on to another plot. The period of cu ...

. Cleghorn's 1861 manual, ''The forests and gardens of South India'', became the definitive work on the subject and was widely used by forest assistants in the subcontinent. In 1861, the Forest Department extended its remit into the Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi Language, Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also Romanization, romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the I ...

.

Sir Dietrich Brandis, a

Sir Dietrich Brandis, a German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

forester, joined the British service in 1856 as superintendent of the teak forests of Pegu division in eastern Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John C. Wells, Joh ...

. During that time Burma's teak

Teak (''Tectona grandis'') is a tropical hardwood tree species in the family Lamiaceae. It is a large, deciduous tree that occurs in mixed hardwood forests. ''Tectona grandis'' has small, fragrant white flowers arranged in dense clusters ( pan ...

forests were controlled by militant Karen

Karen may refer to:

* Karen (name), a given name and surname

* Karen (slang), a term and meme for a demanding woman displaying certain behaviors

People

* Karen people, an ethnic group in Myanmar and Thailand

** Karen languages or Karenic la ...

tribals. He introduced the "taungya" system, in which Karen villagers provided labor for clearing, planting and weeding teak plantations. After seven years in Burma, Brandis was appointed Inspector General of Forests in India, a position he served in for 20 years. He formulated new forest legislation and helped establish research and training institutions. The Imperial Forest School

The Forest Research Institute ( FRI; hi, वन अनुसन्धान संस्थान) is a Natural Resource Service training institute of the Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education and is an institution in the field of ...

at Dehradun

Dehradun () is the capital and the List of cities in Uttarakhand by population, most populous city of the Indian state of Uttarakhand. It is the administrative headquarters of the eponymous Dehradun district, district and is governed by the Dehr ...

was founded by him.

Germans were prominent in the forestry administration of British India. As well as Brandis, Berthold Ribbentrop

Berthold Ribbentrop was a pioneering forester from Germany who worked in India with Sir Dietrich Brandis and others. He is said to have inspired Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)'' The Times'', ...

and Sir William P.D. Schlich brought new methods to Indian conservation, the latter becoming the Inspector-General in 1883 after Brandis stepped down. Schlich helped to establish the journal '' Indian Forester'' in 1874, and became the founding director of the first forestry

Forestry is the science and craft of creating, managing, planting, using, conserving and repairing forests, woodlands, and associated resources for human and environmental benefits. Forestry is practiced in plantations and natural stands. ...

school in England at Cooper's Hill in 1885. He authored the five-volume ''Manual of Forestry'' (1889–96) on silviculture, forest management, forest protection, and forest utilization, which became the standard and enduring textbook for forestry students.

Conservation in the United States

The American movement received its inspiration from 19th century works that exalted the inherent value of nature, quite apart from human usage. Author

The American movement received its inspiration from 19th century works that exalted the inherent value of nature, quite apart from human usage. Author Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817May 6, 1862) was an American naturalist, essayist, poet, and philosopher. A leading transcendentalist, he is best known for his book ''Walden'', a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings, and h ...

(1817–1862) made key philosophical contributions that exalted nature. Thoreau was interested in peoples' relationship with nature and studied this by living close to nature in a simple life. He published his experiences in the book ''Walden

''Walden'' (; first published in 1854 as ''Walden; or, Life in the Woods'') is a book by American transcendentalist writer Henry David Thoreau. The text is a reflection upon the author's simple living in natural surroundings. The work is part ...

,'' which argued that people should become intimately close with nature. The ideas of Sir Brandis, Sir William P.D. Schlich and Carl A. Schenck

Carl Alwin Schenck (March 25, 1868 – May 17, 1955) was a German forester and pioneering forestry educator. He founded the Biltmore Forest School, the first forestry school in North America on George W. Vanderbilt's Biltmore Estate. His teachin ...

were also very influential— Gifford Pinchot, the first chief of the USDA Forest Service, relied heavily upon Brandis' advice for introducing professional forest management in the U.S. and on how to structure the Forest Service.

Both conservationists and preservationists appeared in political debates during the Progressive Era (the 1890s–early 1920s). There were three main positions.

* Laissez-faire: The laissez-faire position held that owners of private property—including lumber and mining companies, should be allowed to do anything they wished on their properties.

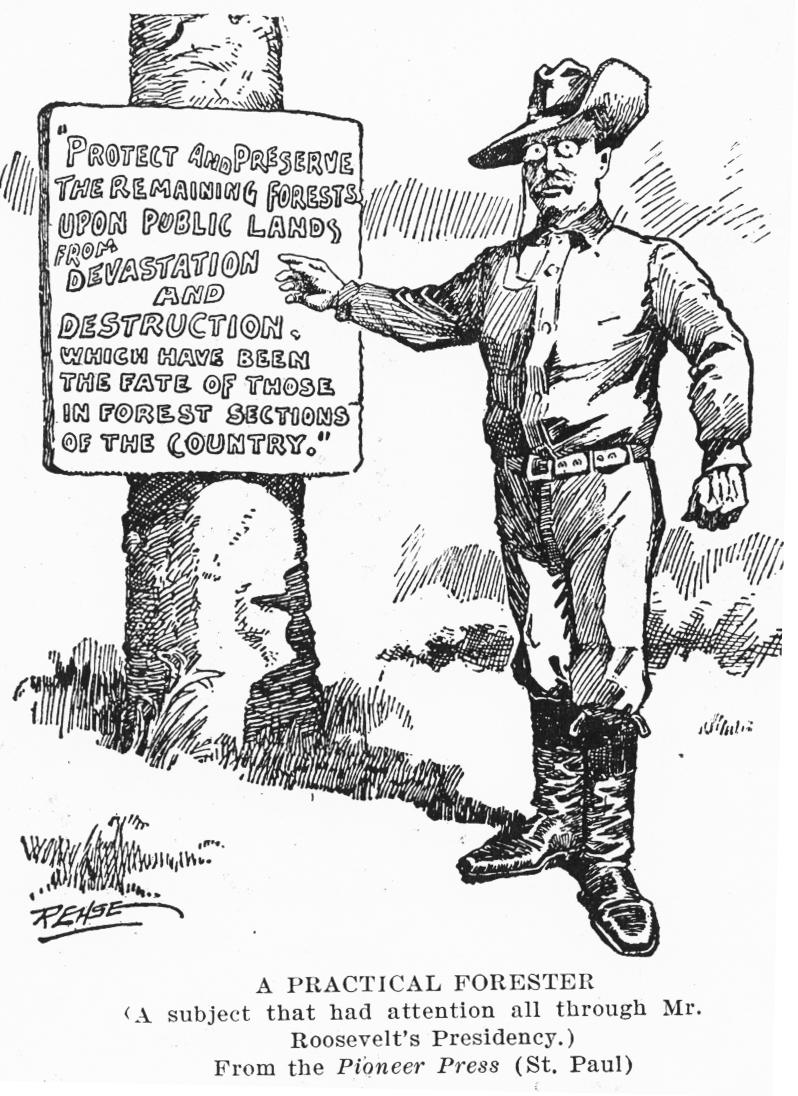

* Conservationists: The conservationists, led by future President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

and his close ally George Bird Grinnell, were motivated by the wanton waste that was taking place at the hand of market forces, including logging and hunting. This practice resulted in placing a large number of North American game species on the edge of extinction. Roosevelt recognized that the laissez-faire approach of the U.S. Government was too wasteful and inefficient. In any case, they noted, most of the natural resources in the western states were already owned by the federal government. The best course of action, they argued, was a long-term plan devised by national experts to maximize the long-term economic benefits of natural resources. To accomplish the mission, Roosevelt and Grinnell formed the Boone and Crockett Club, whose members were some of the best minds and influential men of the day. Its contingency of conservationists, scientists, politicians, and intellectuals became Roosevelt's closest advisers during his march to preserve wildlife and habitat across North America.

* Preservationists: Preservationists, led by John Muir

John Muir ( ; April 21, 1838December 24, 1914), also known as "John of the Mountains" and "Father of the National Parks", was an influential Scottish-American naturalist, author, environmental philosopher, botanist, zoologist, glaciologis ...

(1838–1914), argued that the conservation policies were not strong enough to protect the interest of the natural world because they continued to focus on the natural world as a source of economic production.

The debate between conservation and preservation reached its peak in the public debates over the construction of California's Hetch Hetchy dam

O'Shaughnessy Dam is a high concrete arch-gravity dam in Tuolumne County, California, United States. It impounds the Tuolumne River, forming the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir at the lower end of Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park, about ...

in Yosemite National Park

Yosemite National Park ( ) is an American national park in California, surrounded on the southeast by Sierra National Forest and on the northwest by Stanislaus National Forest. The park is managed by the National Park Service and covers an ...

which supplies the water supply of San Francisco. Muir, leading the Sierra Club

The Sierra Club is an environmental organization with chapters in all 50 United States, Washington D.C., and Puerto Rico. The club was founded on May 28, 1892, in San Francisco, California, by Scottish-American preservationist John Muir, who b ...

, declared that the valley must be preserved for the sake of its beauty: "No holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man."

President Roosevelt put conservationist issues high on the national agenda. He worked with all the major figures of the movement, especially his chief advisor on the matter, Gifford Pinchot and was deeply committed to conserving natural resources. He encouraged the Newlands Reclamation Act of 1902 to promote federal construction of dams to irrigate small farms and placed 230 million acres (360,000 mi2 or 930,000 km2) under federal protection. Roosevelt set aside more federal land for national park

A national park is a natural park in use for conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state declares or owns. Although individual ...

s and nature preserve

A nature reserve (also known as a wildlife refuge, wildlife sanctuary, biosphere reserve or bioreserve, natural or nature preserve, or nature conservation area) is a protected area of importance for flora, fauna, or features of geological or ...

s than all of his predecessors combined.

United States Forest Service

The United States Forest Service (USFS) is an agency of the United States Department of Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture that administers the nation's 154 United States National Forest, national forests and 20 United States Nationa ...

, signed into law the creation of five national parks, and signed the year 1906 Antiquities Act

The Antiquities Act of 1906 (, , ), is an act that was passed by the United States Congress and signed into law by Theodore Roosevelt on June 8, 1906. This law gives the President of the United States the authority to, by presidential pro ...

, under which he proclaimed 18 new national monuments. He also established the first 51 bird reserves, four game preserves, and 150 national forests, including Shoshone National Forest, the nation's first. The area of the United States that he placed under public protection totals approximately .

Gifford Pinchot had been appointed by McKinley as chief of Division of Forestry in the Department of Agriculture. In 1905, his department gained control of the national forest reserves. Pinchot promoted private use (for a fee) under federal supervision. In 1907, Roosevelt designated 16 million acres (65,000 km2) of new national forests just minutes before a deadline.

In May 1908, Roosevelt sponsored the Conference of Governors held in the White House, with a focus on natural resources and their most efficient use. Roosevelt delivered the opening address: "Conservation as a National Duty".

In 1903 Roosevelt toured the Yosemite Valley with John Muir

John Muir ( ; April 21, 1838December 24, 1914), also known as "John of the Mountains" and "Father of the National Parks", was an influential Scottish-American naturalist, author, environmental philosopher, botanist, zoologist, glaciologis ...

, who had a very different view of conservation, and tried to minimize commercial use of water resources and forests. Working through the Sierra Club he founded, Muir succeeded in 1905 in having Congress transfer the Mariposa Grove

Mariposa Grove is a sequoia grove located near Wawona, California, United States, in the southernmost part of Yosemite National Park. It is the largest grove of giant sequoias in the park, with several hundred mature examples of the tree. Two o ...

and Yosemite Valley to the federal government. While Muir wanted nature preserved for its own sake, Roosevelt subscribed to Pinchot's formulation, "to make the forest produce the largest amount of whatever crop or service will be most useful, and keep on producing it for generation after generation of men and trees."

Theodore Roosevelt's view on conservationism remained dominant for decades; Franklin D. Roosevelt authorised the building of many large-scale dams and water projects, as well as the expansion of the National Forest System to buy out sub-marginal farms. In 1937, the Pittman–Robertson Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act was signed into law, providing funding for state agencies to carry out their conservation efforts.

While Theodore Roosevelt was one of the leading activists for the conservation movement in the United States, he also believed that the threats to the natural world were equally threats to white Americans. They held the belief that the cities, industries and factories that were overtaking the wilderness and threatening the native plants and animals were also consuming and threatening the racial vigor that they believed white Americans held which made them superior. Roosevelt was a big believer that white male virility depended on wildlife for its vigor, and that depleting wildlife would result in a much weaker nation. This lead Roosevelt to support the passing of many immigration restrictions, eugenics legislations and wildlife preservation laws. He drew much inspiration for his beliefs from Madison Grant, a well known American eugenicist and conservationist. Grant worked alongside Roosevelt in the American conservation movement and was even secretary and president of the Boone and Crockett Club. In 1916, Grant published the book "The Passing of the Great Race", which explained the hierarchy of races, with white, "Nordic" men at the top, and all other races below. The German translation of this book was used by Nazi Germany as the source for many of their beliefs.

The National Audubon Society was founded in 1905 with the priority of protecting/conserving various waterbird species. However, the first state-level Audubon group was created in 1896 by Harriet Hemenway and Minna B. Hall to convince women to refrain from buying hats made with bird feathers- a common practice at the time. The organization is named after John Audubon, a naturalist and legendary bird painter. The lesser known truth is that he was a slaveholder who also included many racist tales in his many books. Despite his views of racial inequality, Audubon did find black and indigenous people to be scientifically useful, often using their local knowledge in his books and relying on them to collect specimens for him.

While Theodore Roosevelt was one of the leading activists for the conservation movement in the United States, he also believed that the threats to the natural world were equally threats to white Americans. They held the belief that the cities, industries and factories that were overtaking the wilderness and threatening the native plants and animals were also consuming and threatening the racial vigor that they believed white Americans held which made them superior. Roosevelt was a big believer that white male virility depended on wildlife for its vigor, and that depleting wildlife would result in a much weaker nation. This lead Roosevelt to support the passing of many immigration restrictions, eugenics legislations and wildlife preservation laws. He drew much inspiration for his beliefs from Madison Grant, a well known American eugenicist and conservationist. Grant worked alongside Roosevelt in the American conservation movement and was even secretary and president of the Boone and Crockett Club. In 1916, Grant published the book "The Passing of the Great Race", which explained the hierarchy of races, with white, "Nordic" men at the top, and all other races below. The German translation of this book was used by Nazi Germany as the source for many of their beliefs.

The National Audubon Society was founded in 1905 with the priority of protecting/conserving various waterbird species. However, the first state-level Audubon group was created in 1896 by Harriet Hemenway and Minna B. Hall to convince women to refrain from buying hats made with bird feathers- a common practice at the time. The organization is named after John Audubon, a naturalist and legendary bird painter. The lesser known truth is that he was a slaveholder who also included many racist tales in his many books. Despite his views of racial inequality, Audubon did find black and indigenous people to be scientifically useful, often using their local knowledge in his books and relying on them to collect specimens for him.

Since 1970

Environmental reemerged on the national agenda in 1970, with RepublicanRichard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

playing a major role, especially with his creation of the Environmental Protection Agency

A biophysical environment is a biotic and abiotic surrounding of an organism or population, and consequently includes the factors that have an influence in their survival, development, and evolution. A biophysical environment can vary in scale ...

. The debates over the public lands and environmental politics played a supporting role in the decline of liberalism and the rise of modern environmentalism. Although Americans consistently rank environmental issues as "important", polling data indicates that in the voting booth voters rank the environmental issues low relative to other political concerns.

The growth of the Republican party's political power in the inland West (apart from the Pacific coast) was facilitated by the rise of popular opposition to public lands reform. Successful Democrats in the inland West and Alaska typically take more conservative positions on environmental issues than Democrats from the Coastal states. Conservatives drew on new organizational networks of think tanks, industry groups, and citizen-oriented organizations, and they began to deploy new strategies that affirmed the rights of individuals to their property, protection of extraction rights, to hunt and recreate, and to pursue happiness unencumbered by the federal government at the expense of resource conservation.

In 2019, convivial conservation was an idea proposed by Bram Büscher and Robert Fletcher. Convivial conservation draws on social movements and concepts like environmental justice and structural change to create a post-capitalist approach to conservation.

Conservation in Costa Rica

World Wide Fund for Nature

TheWorld Wide Fund for Nature

The World Wide Fund for Nature Inc. (WWF) is an international non-governmental organization founded in 1961 that works in the field of wilderness preservation and the reduction of human impact on the environment. It was formerly named the W ...

(WWF) is an international non-governmental organization

A non-governmental organization (NGO) or non-governmental organisation (see spelling differences) is an organization that generally is formed independent from government. They are typically nonprofit entities, and many of them are active in ...

founded in 1961, working in the field of the wilderness preservation, and the reduction of human impact on the environment

Human impact on the environment (or anthropogenic impact) refers to changes to biophysical environments and to ecosystems, biodiversity, and natural resources caused directly or indirectly by humans. Modifying the environment to fit the need ...

. It was formerly named the "World Wildlife Fund", which remains its official name in Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

.

WWF is the world's largest conservation organization

An environmental organization is an organization coming out of the conservation or environmental movements

that seeks to protect, analyse or monitor the environment against misuse or degradation from human forces.

In this sense the environmen ...

with over five million supporters worldwide, working in more than 100 countries, supporting around 1,300 conservation and environmental projects. They have invested over $1 billion in more than 12,000 conservation initiatives since 1995. WWF is a foundation with 55% of funding from individuals and bequests, 19% from government sources (such as the World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and grants to the governments of low- and middle-income countries for the purpose of pursuing capital projects. The World Bank is the collective name for the Inte ...

, DFID

The Department for International Development (DFID) was a department of HM Government responsible for administering foreign aid from 1997 to 2020. The goal of the department was "to promote sustainable development and eliminate world poverty". ...

, USAID

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is an independent agency of the U.S. federal government that is primarily responsible for administering civilian foreign aid and development assistance. With a budget of over $27 bi ...

) and 8% from corporations in 2014.

WWF aims to "stop the degradation of the planet's natural environment and to build a future in which humans live in harmony with nature." The Living Planet Report is published every two years by WWF since 1998; it is based on a Living Planet Index and ecological footprint

The ecological footprint is a method promoted by the Global Footprint Network to measure human demand on natural capital, i.e. the quantity of nature it takes to support people or an economy. It tracks this demand through an ecological accounti ...

calculation. In addition, WWF has launched several notable worldwide campaigns including Earth Hour

Earth Hour is a worldwide movement organized by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). The event is held annually, encouraging individuals, communities, and businesses to turn off non-essential electric lights, for one hour, from 8:00 to 9:00 p.m. ...

and Debt-for-Nature Swap, and its current work is organized around these six areas: food, climate, freshwater, wildlife, forests, and oceans.

"Conservation Far" approach

A conservation-exploitation dichotomy has plagued a place many may not expect: Conservation institutions. Institutions such as the WWF have historically been the cause of the displacement and divide between native populations and the lands they inhabit. The overbearing reason behind this rather contradictory truth is because of the organization's historically colonial, paternalistic, and neoliberal approaches to conservation. Claus, in his article "Drawing the Sea Near: Satoumi and Coral Reef Conservation in Okinawa", expands on these approaches and their effectiveness, not as much in conservation, but in creating the value of and commercializing endangered flora and fauna. One way in which this has taken place is through a separation between people, even locals, and the nature spaces they aimed to protect. This is what Claus calls the "Conservation-Far" method, in which access to lands is completely relinquished upon the locals and tourists, by an external, foreign entity. This entity is largely unaware of the customs and values held by those within the territory surrounding nature and their role within it. Claus relays the history of an Island in Japan, Shiraho, in which the people's traditional ways of tending to nature were lost due to modernization and the rise of a fast-paced lifestyle. It is the view of a "Conservation-Near" approach that would suggest a regeneration of these customs within the local area. This engages those near in proximity to the lands in the conservation efforts and holds them accountable for their direct effects on its preservation. Unlike the hands-on, full sensory experience permitted by conservation-near methodologies, conservation-far drills visuals and sight as being the main interaction medium between people and the environment. An emphasis on observation only stems from a deeper association with intellect and observation. The alternative to this is more of a bodily or "primitive" consciousness, which is associated with lower-intelligence and people of color. A new, integrated approach to conservation is being investigated in recent years by institutions such as WWF.Evidence-based conservation

Areas of concern

Deforestation

Deforestation or forest clearance is the removal of a forest or stand of trees from land that is then converted to non-forest use. Deforestation can involve conversion of forest land to farms, ranches, or urban use. The most concentrated ...

and overpopulation

Overpopulation or overabundance is a phenomenon in which a species' population becomes larger than the carrying capacity of its environment. This may be caused by increased birth rates, lowered mortality rates, reduced predation or large scale ...

are issues affecting all regions of the world. The consequent destruction of wildlife habitat has prompted the creation of conservation groups in other countries, some founded by local hunters who have witnessed declining wildlife populations first hand. Also, it was highly important for the conservation movement to solve problems of living conditions in the cities and the overpopulation of such places.

Boreal forest and the Arctic

The idea of incentive conservation is a modern one but its practice has clearly defended some of the sub Arctic wildernesses and the wildlife in those regions for thousands of years, especially by indigenous peoples such as the Evenk, Yakut, Sami, Inuit and Cree. The fur trade and hunting by these peoples have preserved these regions for thousands of years. Ironically, the pressure now upon them comes from non-renewable resources such as oil, sometimes to make synthetic clothing which is advocated as a humane substitute for fur. (See Raccoon dog for case study of the conservation of an animal through fur trade.) Similarly, in the case of the beaver, hunting and fur trade were thought to bring about the animal's demise, when in fact they were an integral part of its conservation. For many years children's books stated and still do, that the decline in the beaver population was due to the fur trade. In reality however, the decline in beaver numbers was because of habitat destruction and deforestation, as well as its continued persecution as a pest (it causes flooding). In Cree lands, however, where the population valued the animal for meat and fur, it continued to thrive. The Inuit defend their relationship with the seal in response to outside critics.Latin America (Bolivia)

The Izoceño- Guaraní of Santa Cruz Department,Bolivia

, image_flag = Bandera de Bolivia (Estado).svg

, flag_alt = Horizontal tricolor (red, yellow, and green from top to bottom) with the coat of arms of Bolivia in the center

, flag_alt2 = 7 × 7 square p ...

, is a tribe of hunters who were influential in establishing the Capitania del Alto y Bajo Isoso (CABI). CABI promotes economic growth and survival of the Izoceno people while discouraging the rapid destruction of habitat within Bolivia's Gran Chaco

The Gran Chaco or Dry Chaco is a sparsely populated, hot and semiarid lowland natural region of the Río de la Plata basin, divided among eastern Bolivia, western Paraguay, northern Argentina, and a portion of the Brazilian states of Mato ...

. They are responsible for the creation of the 34,000 square kilometre Kaa-Iya del Gran Chaco National Park and Integrated Management Area (KINP). The KINP protects the most biodiverse portion of the Gran Chaco, an ecoregion shared with Argentina, Paraguay and Brazil. In 1996, the Wildlife Conservation Society joined forces with CABI to institute wildlife and hunting monitoring programs in 23 Izoceño communities. The partnership combines traditional beliefs and local knowledge with the political and administrative tools needed to effectively manage habitats. The programs rely solely on voluntary participation by local hunters who perform self-monitoring techniques and keep records of their hunts. The information obtained by the hunters participating in the program has provided CABI with important data required to make educated decisions about the use of the land. Hunters have been willing participants in this program because of pride in their traditional activities, encouragement by their communities and expectations of benefits to the area.

Africa (Botswana)

In order to discourage illegal South African hunting parties and ensure future local use and sustainability, indigenous hunters inBotswana

Botswana (, ), officially the Republic of Botswana ( tn, Lefatshe la Botswana, label= Setswana, ), is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. Botswana is topographically flat, with approximately 70 percent of its territory being the Kal ...

began lobbying for and implementing conservation practices in the 1960s. The Fauna Preservation Society of Ngamiland (FPS) was formed in 1962 by the husband and wife team: Robert Kay and June Kay, environmentalists working in conjunction with the Batawana tribes to preserve wildlife habitat.

The FPS promotes habitat conservation and provides local education for preservation of wildlife. Conservation initiatives were met with strong opposition from the Botswana government because of the monies tied to big-game hunting. In 1963, BaTawanga Chiefs and tribal hunter/adventurers in conjunction with the FPS founded Moremi National Park and Wildlife Refuge, the first area to be set aside by tribal people rather than governmental forces. Moremi National Park is home to a variety of wildlife, including lions, giraffes, elephants, buffalo, zebra, cheetahs and antelope, and covers an area of 3,000 square kilometers. Most of the groups involved with establishing this protected land were involved with hunting and were motivated by their personal observations of declining wildlife and habitat.

See also

Notes

Further reading

World

* Barton, Gregory A. ''Empire, Forestry and the Origins of Environmentalism,'' (2002), covers British Empire * Clover, Charles. ''The End of the Line: How overfishing is changing the world and what we eat''. (2004) Ebury Press, London. * Haq, Gary, and Alistair Paul. ''Environmentalism since 1945'' (Routledge, 2013). * Jones, Eric L. "The History of Natural Resource Exploitation in the Western World," ''Research in Economic History,'' 1991 Supplement 6, pp 235–252 * McNeill, John R. ''Something New Under the Sun: An Environmental History of the Twentieth Century'' (2000).Regional studies

Africa

* Adams, Jonathan S.; McShane, Thomas O. ''Myth of Wild Africa: Conservation without Illusion'' (1992) 266p; covers 1900 to 1980s * Anderson, David; Grove, Richard. ''Conservation in Africa: People, Policies & Practice'' (1988), 355pp * Bolaane, Maitseo. "Chiefs, Hunters & Adventurers: The Foundation of the Okavango/Moremi National Park, Botswana". ''Journal of Historical Geography.'' 31.2 (Apr. 2005): 241–259. * Carruthers, Jane. "Africa: Histories, Ecologies, and Societies," Environment and History, 10 (2004), pp. 379–406; * Showers, Kate B. ''Imperial Gullies: Soil Erosion and Conservation in Lesotho'' (2005) 346ppAsia-Pacific

* Bolton, Geoffrey. ''Spoils and Spoilers: Australians Make Their Environment, 1788-1980'' (1981) 197pp * Economy, Elizabeth. ''The River Runs Black: The Environmental Challenge to China's Future'' (2010) * Elvin, Mark. ''The Retreat of the Elephants: An Environmental History of China'' (2006) * Grove, Richard H.; Damodaran, Vinita Jain; Sangwan, Satpal. ''Nature and the Orient: The Environmental History of South and Southeast Asia'' (1998) 1036pp * Johnson, Erik W., Saito, Yoshitaka, and Nishikido, Makoto. "Organizational Demography of Japanese Environmentalism," ''Sociological Inquiry,'' Nov 2009, Vol. 79 Issue 4, pp 481–504 * Thapar, Valmik. ''Land of the Tiger: A Natural History of the Indian Subcontinent'' (1998) 288ppLatin America

* Boyer, Christopher. ''Political Landscapes: Forests, Conservation, and Community in Mexico''. Duke University Press (2015) * Dean, Warren. ''With Broadax and Firebrand: The Destruction of the Brazilian Atlantic Forest'' (1997) * Evans, S. ''The Green Republic: A Conservation History of Costa Rica''. University of Texas Press. (1999) * Funes Monzote, Reinaldo. ''From Rainforest to Cane Field in Cuba: An Environmental History since 1492'' (2008) * Melville, Elinor G. K. ''A Plague of Sheep: Environmental Consequences of the Conquest of Mexico'' (1994) * Miller, Shawn William. ''An Environmental History of Latin America'' (2007) * Noss, Andrew and Imke Oetting. "Hunter Self-Monitoring by the Izoceño -Guarani in the Bolivian Chaco". ''Biodiversity & Conservation''. 14.11 (2005): 2679–2693. * Simonian, Lane. ''Defending the Land of the Jaguar: A History of Conservation in Mexico'' (1995) 326pp * Wakild, Emily. ''An Unexpected Environment: National Park Creation, Resource Custodianship, and the Mexican Revolution''. University of Arizona Press (2011).Europe and Russia

* Arnone Sipari, Lorenzo, ''Scritti scelti di Erminio Sipari sul Parco Nazionale d'Abruzzo (1922-1933)'' (2011), 360pp. * Barca, Stefania, and Ana Delicado. "Anti-nuclear mobilisation and environmentalism in Europe: A view from Portugal (1976-1986)." ''Environment and History'' 22.4 (2016): 497–520online

* Bonhomme, Brian. ''Forests, Peasants and Revolutionaries: Forest Conservation & Organization in Soviet Russia, 1917-1929'' (2005) 252pp. * Cioc, Mark. ''The Rhine: An Eco-Biography, 1815-2000'' (2002). * Dryzek, John S., et al. ''Green states and social movements: environmentalism in the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, and Norway'' (Oxford UP, 2003). * Jehlicka, Petr. "Environmentalism in Europe: an east-west comparison." in ''Social change and political transformation'' (Routledge, 2018) pp. 112–131. * Simmons, I.G. ''An Environmental History of Great Britain: From 10,000 Years Ago to the Present'' (2001). * Uekotter, Frank. ''The greenest nation?: A new history of German environmentalism'' (MIT Press, 2014). * Weiner, Douglas R. ''Models of Nature: Ecology, Conservation and Cultural Revolution in Soviet Russia'' (2000) 324pp; covers 1917 to 1939.

United States

* Bates, J. Leonard. "Fulfilling American Democracy: The Conservation Movement, 1907 to 1921", ''The Mississippi Valley Historical Review,'' (1957), 44#1 pp. 29–57in JSTOR

* Brinkley, Douglas G. ''The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America,'' (2009

excerpt and text search

* Cawley, R. McGreggor. ''Federal Land, Western Anger: The Sagebrush Rebellion and Environmental Politics'' (1993), on conservatives * Flippen, J. Brooks. ''Nixon and the Environment'' (2000). * Hays, Samuel P. ''Beauty, Health, and Permanence: Environmental Politics in the United States, 1955–1985'' (1987), the standard scholarly history ** Hays, Samuel P. ''A History of Environmental Politics since 1945'' (2000), shorter standard history * Hays, Samuel P. ''Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency'' (1959), on Progressive Era. * King, Judson. ''The Conservation Fight, From Theodore Roosevelt to the Tennessee Valley Authority'' (2009) * Nash, Roderick. ''Wilderness and the American Mind,'' (3rd ed. 1982), the standard intellectual history * * Rothmun, Hal K. ''The Greening of a Nation? Environmentalism in the United States since 1945'' (1998) * Scheffer, Victor B. ''The Shaping of Environmentalism in America'' (1991). * Sellers, Christopher. ''Crabgrass Crucible: Suburban Nature and the Rise of Environmentalism in Twentieth-Century America'' (2012) * Strong, Douglas H. ''Dreamers & Defenders: American Conservationists.'' (1988

online edition

good biographical studies of the major leaders * Taylor, Dorceta E. ''The Rise of the American Conservation Movement: Power, Privilege, and Environmental Protection'' (Duke U.P. 2016) x, 486 pp. * Turner, James Morton, "The Specter of Environmentalism": Wilderness, Environmental Politics, and the Evolution of the New Right. ''The Journal of American History'' 96.1 (2009): 123-4

* Vogel, David. ''California Greenin': How the Golden State Became an Environmental Leader'' (2018) 280 pp

online review

Historiography

* Cioc, Mark,Björn-Ola Linnér

Björn-Ola Linnér (born 1963) is a Swedish climate policy scholar and professor at Linköping University. He is program director of Mistra Geopolitics, a research programme that critically examines and explores the interplay between the dynamics ...

, and Matt Osborn, "Environmental History Writing in Northern Europe," ''Environmental History,'' 5 (2000), pp. 396–406

* Bess, Michael, Mark Cioc, and James Sievert, "Environmental History Writing in Southern Europe," ''Environmental History,'' 5 (2000), pp. 545–56;

* Coates, Peter. "Emerging from the Wilderness (or, from Redwoods to Bananas): Recent Environmental History in the United States and the Rest of the Americas," Environment and History, 10 (2004), pp. 407–38

* Hay, Peter. ''Main Currents in Western Environmental Thought'' (2002), standard scholarly historexcerpt and text search

* McNeill, John R. "Observations on the Nature and Culture of Environmental History," ''History and Theory,'' 42 (2003), pp. 5–43. * Robin, Libby, and Tom Griffiths, "Environmental History in Australasia," ''Environment and History,'' 10 (2004), pp. 439–74 * Worster, Donald, ed. ''The Ends of the Earth: Perspectives on Modern Environmental History'' (1988)

External links

A history of conservation in New Zealand

''For Future Generations'', a Canadian documentary on conservation and national parks

{{DEFAULTSORT:Conservation Movement Environmental conservation Environmental ethics Environmental movements el:Κίνημα Διατήρησης fr:Conservation de la nature sv:Naturskydd