Black Canadian on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Black Canadians (also known as Caribbean-Canadians or Afro-Canadians) are people of full or partial sub-Saharan African descent who are citizens or permanent residents of

''

The first recorded Black person to have potentially entered Canadian waters was an unnamed Black man on board the ''Jonas'', which was bound for

The first recorded Black person to have potentially entered Canadian waters was an unnamed Black man on board the ''Jonas'', which was bound for

At the time of the

At the time of the

This latter group was largely made up of merchants and labourers, and many set up home in Birchtown near Shelburne. Some settled in

The Canadian climate made it uneconomic to keep enslaved African people year-round, unlike the

The Canadian climate made it uneconomic to keep enslaved African people year-round, unlike the

In 1772, prior to the American Revolution, Britain outlawed the slave trade in the British Isles followed by the ''

During the course of one week in June 1854, 23 run-away slaves evaded the U.S. border patrols to cross the Detroit river to freedom in Windsor while 43 free people also crossed over to Windsor out of the fear of the bounty hunters. The American-born Canadian sociologist Daniel G. Hill wrote this week in June 1854 appeared to be typical of the black exodus to Canada. Public opinion tended to be on the side of run-away slaves and against the slavers. On 26 February 1851, the Toronto chapter of the Anti-Slavery Society was founded with what was described by the ''Globe'' newspaper as "the largest and most enthusiastic meeting we have ever seen in Toronto" that issued the resolution: "slavery is an outrage on the laws of humanity and its continued practice demands the best exertions for its extinction".Hill, Daniel ''The Freedom-Seekers'', Agincourt: Book Society of Canada, 1981 p. 20. The same meeting committed its members to help the many "houseless and homeless victims of slavery flying to our soil". The Congregationalist minister, the Reverend

During the course of one week in June 1854, 23 run-away slaves evaded the U.S. border patrols to cross the Detroit river to freedom in Windsor while 43 free people also crossed over to Windsor out of the fear of the bounty hunters. The American-born Canadian sociologist Daniel G. Hill wrote this week in June 1854 appeared to be typical of the black exodus to Canada. Public opinion tended to be on the side of run-away slaves and against the slavers. On 26 February 1851, the Toronto chapter of the Anti-Slavery Society was founded with what was described by the ''Globe'' newspaper as "the largest and most enthusiastic meeting we have ever seen in Toronto" that issued the resolution: "slavery is an outrage on the laws of humanity and its continued practice demands the best exertions for its extinction".Hill, Daniel ''The Freedom-Seekers'', Agincourt: Book Society of Canada, 1981 p. 20. The same meeting committed its members to help the many "houseless and homeless victims of slavery flying to our soil". The Congregationalist minister, the Reverend  The refugee slaves who settled in Canada did so primarily in South Western Ontario, with significant concentrations being found in Amherstburg, Colchester, Chatham, Windsor, and Sandwich. Run-away slaves tended to concentrate, partly to provide mutual support, partly because of prejudices, and partly out of the fear of American bounty hunters crossing the border. The run-away slaves usually arrived destitute and without any assets, had to work as laborers for others until they could save up enough money to buy their own farms. These settlements acted as centres of abolitionist thought, with Chatham being the location of abolitionist John Brown's constitutional convention which preceded the later raid on

The refugee slaves who settled in Canada did so primarily in South Western Ontario, with significant concentrations being found in Amherstburg, Colchester, Chatham, Windsor, and Sandwich. Run-away slaves tended to concentrate, partly to provide mutual support, partly because of prejudices, and partly out of the fear of American bounty hunters crossing the border. The run-away slaves usually arrived destitute and without any assets, had to work as laborers for others until they could save up enough money to buy their own farms. These settlements acted as centres of abolitionist thought, with Chatham being the location of abolitionist John Brown's constitutional convention which preceded the later raid on

Africville was described as a "close knit and self-sustaining community" which by the 1860s had its own school, general store, post office and the African United Baptist Church, which was attended by most residents. The black Canadian communities in the late 19th century had a very strong sense of community identity, and black community leaders in both Nova Scotia and Ontario often volunteered to serve as teachers. Through the budgets for black schools in Nova Scotia and Ontario were inferior to those for white schools, the efforts of black community leaders serving as teachers did provide for a "supportive and caring environment" that ensured that black children received at least some education. In a sign in pride in their African heritage, the principal meeting hall for black Haligonians was named Menelik Hall after the Emperor

Africville was described as a "close knit and self-sustaining community" which by the 1860s had its own school, general store, post office and the African United Baptist Church, which was attended by most residents. The black Canadian communities in the late 19th century had a very strong sense of community identity, and black community leaders in both Nova Scotia and Ontario often volunteered to serve as teachers. Through the budgets for black schools in Nova Scotia and Ontario were inferior to those for white schools, the efforts of black community leaders serving as teachers did provide for a "supportive and caring environment" that ensured that black children received at least some education. In a sign in pride in their African heritage, the principal meeting hall for black Haligonians was named Menelik Hall after the Emperor

The flow between the United States and Canada continued in the twentieth century. Some Black Canadians trace their ancestry to people who fled racism in

The flow between the United States and Canada continued in the twentieth century. Some Black Canadians trace their ancestry to people who fled racism in  During the First World War, Black volunteers to the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) were at first refused, but in response to criticism, the Defense Minister, Sir

During the First World War, Black volunteers to the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) were at first refused, but in response to criticism, the Defense Minister, Sir

In 1946, a Black woman from Halifax, Viola Desmond, watched a film in a segregated cinema in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia, which led to her being dragged out of the theatre by the manager and a policeman.Reynolds, Glenn ''Viola Desmond's Canada'', Halifax: Fernwood Publishing, 2016 p. 61. Desmond was convicted and fined for not paying the one cent difference in sales tax between buying a ticket in the white section, where she sat, and the Black section, where she was supposed to sit. The Desmond case attracted much publicity as various civil rights groups rallied in her defense. Desmond fought the fine in the appeals court, where she lost, but the incident led the Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Coloured People to pressure the Nova Scotia government to pass the Fair Employment Act of 1955 and Fair Accommodations Act of 1959 to end segregation in Nova Scotia. Following more pressure from Black Canadian groups, in 1951 Ontario passed the Fair Employment Practices Act outlawing racial discrimination in employment and the Fair Accommodation Practices Act of 1955, which outlawed discrimination in housing and renting. In 1958, Ontario established the Anti-Discrimination Commission, which was renamed the Human Rights Commission in 1961. Led by the American-born Black sociologist Daniel G. Hill, the Ontario Anti-Discrimination Commission investigated 2,000 cases of racial discrimination in its first two years, and was described as having a beneficial effect on the ability of Canadian Blacks to obtain employment.Winks, Robin ''The Blacks in Canada'', Montreal: McGill Press, 1997 p. 428. In 1953, Manitoba passed the Fair Employment Act, which was modeled after the Ontario law, and New Brunswick, Saskatchewan and British Columbia passed similar laws in 1956, followed by Quebec in 1964.

The town of

In 1946, a Black woman from Halifax, Viola Desmond, watched a film in a segregated cinema in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia, which led to her being dragged out of the theatre by the manager and a policeman.Reynolds, Glenn ''Viola Desmond's Canada'', Halifax: Fernwood Publishing, 2016 p. 61. Desmond was convicted and fined for not paying the one cent difference in sales tax between buying a ticket in the white section, where she sat, and the Black section, where she was supposed to sit. The Desmond case attracted much publicity as various civil rights groups rallied in her defense. Desmond fought the fine in the appeals court, where she lost, but the incident led the Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Coloured People to pressure the Nova Scotia government to pass the Fair Employment Act of 1955 and Fair Accommodations Act of 1959 to end segregation in Nova Scotia. Following more pressure from Black Canadian groups, in 1951 Ontario passed the Fair Employment Practices Act outlawing racial discrimination in employment and the Fair Accommodation Practices Act of 1955, which outlawed discrimination in housing and renting. In 1958, Ontario established the Anti-Discrimination Commission, which was renamed the Human Rights Commission in 1961. Led by the American-born Black sociologist Daniel G. Hill, the Ontario Anti-Discrimination Commission investigated 2,000 cases of racial discrimination in its first two years, and was described as having a beneficial effect on the ability of Canadian Blacks to obtain employment.Winks, Robin ''The Blacks in Canada'', Montreal: McGill Press, 1997 p. 428. In 1953, Manitoba passed the Fair Employment Act, which was modeled after the Ontario law, and New Brunswick, Saskatchewan and British Columbia passed similar laws in 1956, followed by Quebec in 1964.

The town of

On 29 January 1969, at Sir George Williams University in Montreal, the Sir George Williams affair began with a group of about 200 students, many of whom were black, occupied the Henry Hall computer building in protest against allegations that a white biology professor, Perry Anderson, was biased in grading black students, which the university had dismissed. The student occupation ended in violence on 11 February 1969 when the riot squad of the ''Service de police de la Ville de Montréal'' stormed the Hall building, a fire was started causing $2 million worth of damage (it is disputed whether the police or the students started the fire), and many of the protesting students were beaten and arrested. The entire event received much media attention; it was recorded live for television by the news crews present. As the Hall building burned and the policemen beat the students, onlookers in the crowds outside chanted "Burn, niggers, burn!" and "Let the niggers burn!". Afterwards, the protesting students were divided by race by the police with charges laid against the 97 black students present in the Hall building. The two leaders of the protest, Roosevelt "Rosie" Douglas and

On 29 January 1969, at Sir George Williams University in Montreal, the Sir George Williams affair began with a group of about 200 students, many of whom were black, occupied the Henry Hall computer building in protest against allegations that a white biology professor, Perry Anderson, was biased in grading black students, which the university had dismissed. The student occupation ended in violence on 11 February 1969 when the riot squad of the ''Service de police de la Ville de Montréal'' stormed the Hall building, a fire was started causing $2 million worth of damage (it is disputed whether the police or the students started the fire), and many of the protesting students were beaten and arrested. The entire event received much media attention; it was recorded live for television by the news crews present. As the Hall building burned and the policemen beat the students, onlookers in the crowds outside chanted "Burn, niggers, burn!" and "Let the niggers burn!". Afterwards, the protesting students were divided by race by the police with charges laid against the 97 black students present in the Hall building. The two leaders of the protest, Roosevelt "Rosie" Douglas and

In 1984, the New Democrat

In 1984, the New Democrat

National average: 3.5% (1,198,540)

Although many Black Canadians live in integrated communities, a number of notable Black communities have been known, both as unique settlements and as Black-dominated neighbourhoods in urban centres.

The most historically documented Black settlement in Canadian history is the defunct community of

Although many Black Canadians live in integrated communities, a number of notable Black communities have been known, both as unique settlements and as Black-dominated neighbourhoods in urban centres.

The most historically documented Black settlement in Canadian history is the defunct community of

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

. The majority of Black Canadians are of Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean ...

origin, though the Black Canadian population also consists of African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

immigrants and their descendants (including Black Nova Scotians

Black Nova Scotians (also known as African Nova Scotians and Afro-Nova Scotians) are Black Canadians whose ancestors primarily date back to the Colonial United States as slaves or freemen, later arriving in Nova Scotia, Canada, during the 18th ...

) and many native African immigrants.

Black Canadians have contributed to many areas of Canadian culture

The culture of Canada embodies the artistic, culinary, literary, humour, musical, political and social elements that are representative of Canadians. Throughout Canada's history, its culture has been influenced by European culture and traditions ...

. Many of the first visible minorities

A visible minority () is defined by the Government of Canada as "persons, other than aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour". The term is used primarily as a demographic category by Statistics Canada, in connect ...

to hold high public offices have been Black, including Michaëlle Jean

Michaëlle Jean (; born September 6, 1957) is a Canadian stateswoman and former journalist who served from 2005 to 2010 as governor general of Canada, the 27th since Canadian Confederation. She is the first Haitian Canadian and black person ...

, Donald Oliver

Donald H. Oliver (born November 16, 1938) is a Canadian lawyer, developer and politician. Appointed by

former Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, Oliver served in the Senate of Canada from 1990 until 2013. He was the first black male to sit in the ...

, Stanley G. Grizzle

Stanley George Sinclair Grizzle, (November 18, 1918 – November 12, 2016) CM, O.Ont was a Canadian citizenship judge, soldier, political candidate and civil rights and labour union activist. He died in November 2016 at the age of 97, six da ...

, Rosemary Brown, and Lincoln Alexander

Lincoln MacCauley Alexander (January 21, 1922 – October 19, 2012) was a Canadian lawyer who became the first Black Canadian member of Parliament in the House of Commons, the first Black federal Cabinet Minister (as federal Minister of Labo ...

. Black Canadians form the third-largest visible minority group in Canada, after South Asian

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;;;;; ...

and Chinese Canadians

, native_name =

, native_name_lang =

, image = Chinese Canadian population by province.svg

, image_caption = Chinese Canadians as percent of population by province / territory

, pop = 1,715,7704.63% of the ...

.

Population

According to the 2006 Census byStatistics Canada

Statistics Canada (StatCan; french: Statistique Canada), formed in 1971, is the agency of the Government of Canada commissioned with producing statistics to help better understand Canada, its population, resources, economy, society, and cultu ...

, 783,795 Canadians identified as Black, constituting 2.5% of the entire Canadian population. Of the black population, 11 per cent identified as mixed-race

Mixed race people are people of more than one race or ethnicity. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mixed race people in a variety of contexts, including ''multiethnic'', ''polyethnic'', occasionally ''bi-eth ...

of "white and black". The five most black-populated provinces in 2006 were Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Ca ...

, Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirte ...

, Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest T ...

, British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, for ...

, and Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

. The 10 most black-populated census metropolitan area

The census geographic units of Canada are the census subdivisions defined and used by Canada's federal government statistics bureau Statistics Canada to conduct the country's quinquennial census. These areas exist solely for the purposes of stat ...

s were Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the anch ...

, Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

, Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the c ...

, Calgary

Calgary ( ) is the largest city in the western Canadian province of Alberta and the largest metro area of the three Prairie Provinces. As of 2021, the city proper had a population of 1,306,784 and a metropolitan population of 1,481,806, maki ...

, Vancouver

Vancouver ( ) is a major city in western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the city, up from 631,486 in 2016. ...

, Edmonton

Edmonton ( ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Alberta. Edmonton is situated on the North Saskatchewan River and is the centre of the Edmonton Metropolitan Region, which is surrounded by Alberta's central region. The city an ...

, Hamilton Hamilton may refer to:

People

* Hamilton (name), a common British surname and occasional given name, usually of Scottish origin, including a list of persons with the surname

** The Duke of Hamilton, the premier peer of Scotland

** Lord Hamilto ...

, Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the province of Manitoba in Canada. It is centred on the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, near the longitudinal centre of North America. , Winnipeg had a city population of 749 ...

, Halifax, and Oshawa

Oshawa ( , also ; 2021 population 175,383; CMA 415,311) is a city in Ontario, Canada, on the Lake Ontario shoreline. It lies in Southern Ontario, approximately east of Downtown Toronto. It is commonly viewed as the eastern anchor of the ...

. Preston

Preston is a place name, surname and given name that may refer to:

Places

England

*Preston, Lancashire, an urban settlement

**The City of Preston, Lancashire, a borough and non-metropolitan district which contains the settlement

**County Boro ...

, in the Halifax area, is the community with the highest percentage of Black people, with 69.4%; it was a settlement where the Crown provided land to Black Loyalists after the American Revolution.

According to the 2011 Census, 945,665 Black Canadians were counted, making up 2.9% of Canada's population. In the 2016 Census, the black population totalled 1,198,540, encompassing 3.5% of the country's population.Census Profile, 2016 CensusStatistics Canada

Statistics Canada (StatCan; french: Statistique Canada), formed in 1971, is the agency of the Government of Canada commissioned with producing statistics to help better understand Canada, its population, resources, economy, society, and cultu ...

. Accessed on 6 November 2017. In the 2021 Census, Black Canadians totaled 1,547,870, or 4.1% of the population.

A significant number of Black Canadians also have some Indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology), presence in a region as the result of only natural processes, with no human intervention

*Indigenous (band), an American blues-rock band

*Indigenous (horse), a Hong Kong racehorse ...

heritage, due to historical intermarriage between Black and First Nations

First Nations or first peoples may refer to:

* Indigenous peoples, for ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area.

Indigenous groups

*First Nations is commonly used to describe some Indigenous groups including:

**First Natio ...

or Métis

The Métis ( ; Canadian ) are Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous peoples who inhabit Canada's three Canadian Prairies, Prairie Provinces, as well as parts of British Columbia, the Northwest Territories, and the Northern United State ...

communities. Historically little known, this aspect of Black Canadian cultural history began to emerge in the 2010s, most notably through the musical and documentary film project ''The Afro-Métis Nation''.

Demographics and census issues

At times, Black Canadians are claimed to have been significantly undercounted in census data. WriterGeorge Elliott Clarke

George Elliott Clarke, (born February 12, 1960) is a Canadian poet, playwright and literary critic who served as the Poet Laureate of Toronto from 2012 to 2015 and as the 2016–2017 Canadian Parliamentary Poet Laureate. His work is known larg ...

has cited a McGill University

McGill University (french: link=no, Université McGill) is an English-language public research university located in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Founded in 1821 by royal charter granted by King George IV,Frost, Stanley Brice. ''McGill Univer ...

study which found that fully 43% of all Black Canadians were not counted as Black in the 1991 Canadian census, because they had identified on census forms as British, French, or other cultural identities, which were not included in the census group of Black cultures.

Although subsequent censuses have reported the population of Black Canadians to be much more consistent with the McGill study's revised 1991 estimate than with the official 1991 census data, no study has been conducted to determine whether some Black Canadians are still substantially missed by the self-identification method.

Mixed unions

In the 2006 census, 25.5% of Black Canadians were in a mixed union with a non-Black person. Black and non-black couples represented 40.6% of pairings involving a Black person. Among native-born Black Canadians in couples, 63% of them were in a mixed union. About 17% of Black Canadians born in the Caribbean and in Bermuda were in a mixed relationship, compared to 13% of African-born Black Canadians. Furthermore, 30% of Black men in unions were in mixed unions, compared to 20% of Black women.Terminology

There is no single generally-accepted name for Canadians of Black African descent. The term "African Canadian" is used by some Black Canadians who trace their heritage to enslaved peoples brought by British and French colonists to the North American mainland and toBlack Loyalists

Black Loyalists were people of African descent who sided with the Loyalists during the American Revolutionary War. In particular, the term refers to men who escaped enslavement by Patriot masters and served on the Loyalist side because of the ...

. This group includes those who were promised freedom by the British during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

; thousands of Black Loyalists, including Thomas Peters, were resettled by the Crown in Canada after the war. In addition, an estimated 10,000-30,000 fugitive slaves

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th century to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called freed ...

reached freedom in Canada from the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

during the years before the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, aided by people along the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. ...

. Starting in the 1970s, some persons with multi-generational Canadian ancestry began distinguishing themselves by identifying as Indigenous Black Canadians

Indigenous Black Canadians is a term for people in Canada of African descent who have roots in Canada going back several generations. The term has been proposed to distinguish them from Black people with more recent immigrant roots. Popularized by ...

.

Black Nova Scotians, a distinct cultural group, some of whom can trace their Canadian ancestry back to the 1700s, use both "African Canadian" and "Black Canadian" to describe themselves. For example, there is an Office of African Nova Scotian Affairs and a Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia

The Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia is located in Cherrybrook, Nova Scotia, in the Halifax Regional Municipality. The centre is a museum and a library resource centre that focuses on the history and culture of African Nova Scotians. The organ ...

.

Black Canadians often draw a distinction between those of Afro-Caribbean

Afro-Caribbean people or African Caribbean are Caribbean people who trace their full or partial ancestry to Sub-Saharan Africa. The majority of the modern African-Caribbeans descend from Africans taken as slaves to colonial Caribbean via the tr ...

ancestry and those of other African roots. Many Black people of Caribbean origin in Canada reject the term "African Canadian" as an elision of the uniquely Caribbean aspects of their heritage, instead identifying as "Caribbean Canadian".Rinaldo Walcott

Rinaldo Wayne Walcott (born 1965) is a Canadian academic and writer. He wrote in 2021 "I was born in the Caribbean Barbados and have lived most of my life in Canada, specifically Toronto." Currently, he is an associate professor at the Ontario Ins ...

, ''Black Like Who?: Writing Black Canada''. 2003, Insomniac Press

Insomniac Press is a Canadian independent book publisher.

Founded in 1992 and based in London, Ontario, Insomniac began as a publisher of poetry chapbooks. The company has since evolved into a publisher of a wide variety of fiction, poetry and non ...

. . However, this usage can be problematic because the Caribbean is not populated only by people of African origin, but also by large groups of Indo-Caribbean

Indo-Caribbeans or Indian-Caribbeans are Non-resident Indian and person of Indian origin, Indian people in the Caribbean who are descendants of the Girmityas, Jahaji Indian indenture system, Indian indentured laborers brought by the United Kingdom ...

s, Chinese Caribbean

Chinese Caribbeans (sometimes Sino-Caribbeans) are people of Han Chinese ethnic origin living in the Caribbean. There are small but significant populations of Chinese and their descendants in all countries of the Greater Antilles. They are all pa ...

s, European Caribbeans, Syrian or Lebanese Caribbeans, Latinos, and Amerindians

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are the inhabitants of the Americas before the arrival of the European settlers in the 15th century, and the ethnic groups who now identify themselves with those peoples.

Many Indigenous peoples of the Am ...

. The term West Indian

A West Indian is a native or inhabitant of the West Indies (the Antilles and the Lucayan Archipelago). For more than 100 years the words ''West Indian'' specifically described natives of the West Indies, but by 1661 Europeans had begun to use it ...

is often used by those of Caribbean ancestry, although the term is more of a cultural description than a racial one, and can equally be applied to groups of many different racial and ethnic backgrounds.

More specific national terms such as Jamaican Canadian

Jamaican Canadians are Canadian citizens of Jamaican descent or Jamaican-born permanent residents of Canada. The population, according to Canada's 2016 Census, is 309,485. Jamaican Canadians comprise about 30% of the entire Black Canadian popu ...

, Haitian Canadian

Haitian Canadians are Canadian citizens of Haitian descent or Haiti-born people who reside in Canada. As of 2016, more than 86% of Haitian Canadians reside in Quebec.

Haitian Migration to Canada

Immigration 1960-1980

Immigration from Haiti ...

, or Ghanaian Canadian are also used. No widely used alternative to "Black Canadian" is accepted by the Afro-Caribbean population, those of more recent African extraction, and descendants of immigrants from the United States as an umbrella term for the whole group."As for terminology, in Canada, it is still appropriate to say Black Canadians." Valerie Pruegger, "Black History Month". ''Culture and Community Spirit'', Government of Alberta.

One increasingly common practice, seen in academic usage and in the names and mission statements of some Black Canadian cultural and social organizations, is to always make reference to both the African and Caribbean communities. For example, one key health organization dedicated to HIV/AIDS education and prevention in the Black Canadian community is now named the African and Caribbean Council on HIV/AIDS in Ontario, the Toronto publication ''Pride'' bills itself as an "African-Canadian and Caribbean-Canadian news magazine", and G98.7, a Black-oriented community radio station in Toronto, was initially branded as the Caribbean African Radio Network."Caribbean radio station set for Toronto at 98.7 FM"''

Toronto Star

The ''Toronto Star'' is a Canadian English-language broadsheet daily newspaper. The newspaper is the country's largest daily newspaper by circulation. It is owned by Toronto Star Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary of Torstar Corporation and par ...

'', 2 February 2011.

In French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

, the terms ''Noirs canadiens'' or ''Afro-Canadiens'' are used. ''Nègre'' ("Negro

In the English language, ''negro'' is a term historically used to denote persons considered to be of Black African heritage. The word ''negro'' means the color black in both Spanish and in Portuguese, where English took it from. The term can be ...

") is considered derogatory. Quebec film director Robert Morin

Robert Morin (born May 20, 1949) is a Canadian film director, screenwriter, and cinematographer. In 2009, he received Governor General's Award in Visual and Media Arts.

Biography

Robert Morin is known for his very personal, dark, and pessimisti ...

faced controversy in 2002 when he chose the title '' Le Nèg''' for a film about anti-Black racism, and in 2015 five placenames containing ''Nègre'' (as well as six that contained the English term ''nigger'') were changed after the Commission de toponymie du Québec

The Commission de toponymie du Québec (English: ''Toponymy Commission of Québec'') is the Government of Québec's public body responsible for cataloging, preserving, making official and publicize Québec's place names and their origins according ...

ruled the terms no longer acceptable for use in geographic names.

History

The Black presence in Canada is rooted mostly in voluntary immigration. Despite the various dynamics that may complicate the personal and cultural interrelationships between descendants of the Black Loyalists in Nova Scotia, descendants of former American slaves who viewed Canada as the promise of freedom at the end of the Underground Railroad, and more recent immigrants from the Caribbean or Africa, one common element that unites all of these groups is that they are in Canada because they or their ancestors actively chose of their own free will to settle there.First Black people in Canada

The first recorded Black person to have potentially entered Canadian waters was an unnamed Black man on board the ''Jonas'', which was bound for

The first recorded Black person to have potentially entered Canadian waters was an unnamed Black man on board the ''Jonas'', which was bound for Port-Royal (Acadia)

Port-Royal (1629–1710) was a settlement on the site of modern-day Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, part of the French colony of Acadia. The original French settlement of Port-Royal ( Habitation de Port-Royal (1605-1613, about southwest) had ear ...

. He died of scurvy either at Port Royal, or along the journey, in 1606. The first recorded Black person to set foot on land now known as Canada was a free man named Mathieu da Costa

, birth_date = March 1 1589

, other_names = Mathieu da Costa (sometimes d'Acosta)

, death_date = after 1619

, death_place = Quebec City, Quebec

, known_for = First recorded black person in Canada, Exploration of New France, Bridge betwe ...

. Travelling with navigator Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain (; Fichier OrigineFor a detailed analysis of his baptismal record, see RitchThe baptism act does not contain information about the age of Samuel, neither his birth date nor his place of birth. – 25 December 1635) was a Fr ...

, de Costa arrived in Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

some time between 1603 and 1608 as a translator for the French explorer Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Monts

Pierre Dugua de Mons (or Du Gua de Monts; c. 1558 – 1628) was a French merchant, explorer and colonizer. A Calvinist, he was born in the Château de Mons, in Royan, Saintonge (southwestern France) and founded the first permanent French set ...

. The first known Black person to live in what would become Canada was an enslaved man from Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Afric ...

named Olivier Le Jeune

Olivier Le Jeune (died ) was the first recorded slave purchased in New France.

Olivier was a young boy from Madagascar, believed to have been approximately seven years of age when he was brought to the French colonial settlement of Quebec in New ...

, who may have been of partial Malay ancestry. He was first given to one of the Kirke brothers, likely David Kirke

Sir David Kirke ( – 1654), also spelt David Ker, was an adventurer, privateer and colonial governor. He is best known for his successful capture of Québec in 1629 during the Thirty Years' War and his subsequent governorship of lands in Ne ...

, before being sold as a young child to a French clerk and then later given to Guillaume Couillard, a friend of Champlain's. Le Jeune apparently was set free before his death in 1654, because his death certificate lists him as a ''domestique'' rather than a slave.

As a group, Black people arrived in Canada in several waves. The first of these came as free persons serving in the French Army

History

Early history

The first permanent army, paid with regular wages, instead of feudal levies, was established under Charles VII of France, Charles VII in the 1420 to 1430s. The Kings of France needed reliable troops during and after the ...

and Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It in ...

, though some were enslaved or indentured servant

Indentured servitude is a form of Work (human activity), labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensa ...

s. About 1,000 enslaved people were brought to New France in the 17th and 18th centuries. By the time of the British conquest of New France in 1759–1760, about 3,604 enslaved people were in New France, of whom 1,132 were Black and the rest First Nations people. The majority of the slaves lived in Montreal, the largest city in New France and the centre of the lucrative fur trade.

The majority of the enslaved Africans in New France performed domestic work and were brought to New France to demonstrate the prestige of their wealthy owners, who viewed owning a "slave" as a way of showing off their status and wealth. The majority of the enslaved Africans brought to New France were female domestic servants, and were usually raped by their masters (enslavers), who tended to literally see their enslaved women and girls as their sex slaves. As a result of usually working in the home rather than the fields or mines, enslaved Africans typically lived longer than Aboriginal enslaved people: an average 25.2 years instead of 17.7. As in France's colonies in the West Indies, slavery in New France was governed by the Code Noir

The (, ''Black code'') was a decree passed by the French King Louis XIV in 1685 defining the conditions of slavery in the French colonial empire. The decree restricted the activities of free people of color, mandated the conversion of all e ...

("Black Code") issued by King Louis XIV in 1685 which stated that only Catholics could own slaves; required that all slaves be converted to Roman Catholicism upon their purchase; recognized slave marriages as legal; and forbade masters from selling slave children under the age of 14. Black slaves could also serve as witnesses at religious ceremonies, file legal complaints against free persons and be tried by a jury.

Marie-Joseph Angélique

Marie-Josèphe dite Angélique (died June 21, 1734) was the name given to a Portuguese-born black slave in New France (later the province of Quebec in Canada) by her last owners. She was tried and convicted of setting fire to her owner's home, bu ...

, a black enslaved African from the Madeira islands who arrived in New France in 1725, was accused of setting the fire that burned down most of Montreal on 10 April 1734, for which she was executed. Angélique confessed under torture to setting the fire as a way of creating a diversion so she could escape as she did not wish to be separated from her lover, a white servant named Claude Thibault, as her master (enslaver) was going to sell her to the owner of a sugar plantation in the West Indies. Whether this confession was genuine or not continues to divide historians.

Marie Marguerite Rose, a woman from what is now modern Guinea

Guinea ( ),, fuf, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫, italic=no, Gine, wo, Gine, nqo, ߖߌ߬ߣߍ߫, bm, Gine officially the Republic of Guinea (french: République de Guinée), is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the we ...

was sold into slavery in 1736 when she was about 19 and arrived in Louisbourg on Île Royale (modern Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18. ...

) the same year as the property of Jean Chrysostome Loppinot, a French naval officer stationed at Louisbourg, who fathered a son by her in 1738. In 1755, she was freed and married a Miꞌkmaq Indian who upon his conversion to Roman Catholicism had taken the name Jean-Baptist Laurent.Reynolds, Graham ''Viola Desmond's Canada'', Halifax: Fernwood Publishing, 2016 p. 92. Rose, an excellent cook, became the most successful businesswomen on Île Royale, opening up a tavern that was famous for the quality of its food and brandy all over the island. When she died in 1757, her will and inventory of her possessions showed that she owned expensive clothing imported from France, and like many other women from 18th century west Africa had a fondness for brightly colored dresses.

When New France was ceded to England in 1763, French colonists were assured that they could retain their human property. In 1790, when the British wanted to encourage immigration, they included in law the right to free importation of "Negroes, household furniture, utensils of husbandary or clothing." Although enslaved African people were no longer legally allowed to be bought or sold in Canada, the practice remained legal, although it was increasingly unpopular and written against in local newspapers. By 1829, when the American Secretary of State requested Paul Vallard be extradited to the United States for helping a slave to escape to Canada, the Executive Council of Lower Canada replied, "The state of slavery is not recognized by the Law of Canada. ..Every Slave therefore who comes into the Province is immediately free whether he has been brought in by violence or has entered it of his own accord." The British formally outlawed slavery throughout the British Empire in 1833.

African Americans during the American Revolution

At the time of the

At the time of the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

, inhabitants of the British colonies in North America had to decide where their future lay. Those from the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th centu ...

loyal to the British Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

were called United Empire Loyalists

United Empire Loyalists (or simply Loyalists) is an honorific title which was first given by the 1st Lord Dorchester, the Governor of Quebec, and Governor General of The Canadas, to American Loyalists who resettled in British North America dur ...

and came north. Many White American

White Americans are Americans who identify as and are perceived to be white people. This group constitutes the majority of the people in the United States. As of the 2020 Census, 61.6%, or 204,277,273 people, were white alone. This represented ...

Loyalists brought their enslaved African people with them, numbering approximately 2,500 individuals. During the war, the British had promised freedom and land to enslaved African people who left rebel masters and worked for them; this was announced in Virginia through Lord Dunmore's Proclamation

Dunmore's Proclamation is a historical document signed on November 7, 1775, by John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, royal governor of the British Colony of Virginia. The proclamation declared martial law and promised freedom for slaves of Americ ...

. Enslaved African people also escaped to British lines in New York City and Charleston, and their forces evacuated thousands after the war. They transported 3,000 people to Nova Scotia.Black History in Guelph and Wellington CountyThis latter group was largely made up of merchants and labourers, and many set up home in Birchtown near Shelburne. Some settled in

New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

. Both groups suffered from discriminatory treatment by white settlers and prominent landowners who still held enslaved African people. Some of the refugees had been free black people prior to the war and fled with the other refugees to Nova Scotia, relying on British promises of equality. Under pressure of the new refugees, the city of Saint John amended its charter in 1785 specifically to exclude people of African descent from practising a trade, selling goods, fishing in the harbour, or becoming freemen; these provisions stood until 1870, although by then they were largely ignored.

In 1782, the first race riot

This is a list of ethnic riots by country, and includes riots based on ethnic, sectarian, xenophobic, and racial conflict. Some of these riots can also be classified as pogroms.

Africa

Americas

United States

Nativist period: 1700 ...

in North America took place in Shelburne; white veterans attacked African-American settlers who were getting work that the former soldiers thought they should have. Due to the failure of the British government to support the settlement, the harsh weather, and discrimination on the part of white colonists, 1,192 Black Loyalist men, women and children left Nova Scotia for West Africa on 15 January 1792. They settled in what is now Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierr ...

, where they became Original Settlers (Freetown), the original settlers of Freetown

Freetown is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, educ ...

. They, along with other groups of free transplanted people such as the Black Poor from England, became what is now the Sierra Leone Creole people

The Sierra Leone Creole people ( kri, Krio people) are an ethnic group of Sierra Leone. The Sierra Leone Creole people are descendants of freed African-American, Afro-Caribbean, and Liberated African slaves who settled in the Western Area of ...

, also known as the ''Krio''.

Although difficult to estimate due to the failure to differentiate enslaved African people and free Black populations, it is estimated that by 1784 there were around 40 enslaved Africans within Montreal, compared to around 304 enslaved Africans within the Province of Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirteen ...

. By 1799, vital records note 75 entries regarding Black Canadians, a number that doubled by 1809.

Maroons from the Caribbean

On 26 June 1796,Jamaican Maroons

Jamaican Maroons descend from Africans who freed themselves from slavery on the Colony of Jamaica and established communities of free black people in the island's mountainous interior, primarily in the eastern parishes. Africans who were ensl ...

, numbering 543 men, women and children, were deported on board the three ships ''Dover'', ''Mary'' and ''Anne'' from Jamaica, after being defeated in an uprising against the British colonial government. Their initial destination was Lower Canada, but on 21 and 23 July, the ships arrived in Nova Scotia. At this time Halifax was undergoing a major construction boom initiated by Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn, (Edward Augustus; 2 November 1767 – 23 January 1820) was the fourth son and fifth child of King George III. His only legitimate child became Queen Victoria.

Prince Edward was created Duke of Kent a ...

's efforts to modernize the city's defences. The many building projects had created a labour shortage. Edward was impressed by the Maroons and immediately put them to work at the Citadel in Halifax, Government House, and other defence works throughout the city.

Funds had been provided by the Government of Jamaica to aid in the resettlement of the Maroons in Canada. Five thousand acres were purchased at Preston, Nova Scotia

Preston is an area in central Nova Scotia, Canada in the Halifax Regional Municipality, located on Trunk 7. Preston includes the subdivisions of East Preston, North Preston, Lake Major, Cherrybrook and Loon Lake. The definition sometimes ex ...

, at a cost of £3000. Small farm lots were provided to the Maroons and they attempted to farm the infertile land. Like the former tenants, they found the land at Preston to be unproductive; as a result they had little success. The Maroons also found farming in Nova Scotia difficult because the climate would not allow cultivation of familiar food crops, such as bananas

A banana is an elongated, edible fruit – botanically a berry – produced by several kinds of large herbaceous flowering plants in the genus ''Musa''. In some countries, bananas used for cooking may be called "plantains", distinguis ...

, yams, pineapples

The pineapple (''Ananas comosus'') is a tropical plant with an edible fruit; it is the most economically significant plant in the family Bromeliaceae. The pineapple is indigenous to South America, where it has been cultivated for many centurie ...

or cocoa

Cocoa may refer to:

Chocolate

* Chocolate

* ''Theobroma cacao'', the cocoa tree

* Cocoa bean, seed of ''Theobroma cacao''

* Chocolate liquor, or cocoa liquor, pure, liquid chocolate extracted from the cocoa bean, including both cocoa butter an ...

. Small numbers of Maroons relocated from Preston to Boydville for better farming land. The British Lieutenant Governor Sir John Wentworth made an effort to change the Maroons' culture and beliefs by introducing them to Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global popula ...

. From the monies provided by the Jamaican Government, Wentworth procured an annual stipend of £240 for the support of a school and religious education.John N. Grant. "Black Immigrants into Nova Scotia, 1776–1815", ''The Journal of Negro History''. Vol. 58, No. 3 (Jul 1973). pp. 253–270.

After suffering through the harsh winter of 1796–1797, Wentworth reported the Maroons expressed a desire that "they wish to be sent to India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

or somewhere in the east, to be landed with arms in some country with a climate like that they left, where they may take possession with a strong hand". The British Government and Wentworth opened discussions with the Sierra Leone Company in 1799 to send the Maroons to Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierr ...

. The Jamaican Government had in 1796 initially planned to send the Maroons to Sierra Leone but the Sierra Leone Company rejected the idea. The initial reaction in 1799 was the same, but the company was eventually persuaded to accept the Maroon settlers. On 6 August 1800 the Maroons departed Halifax, arriving on 1 October at Freetown, Sierra Leone.

Upon their arrival in West Africa in 1800, they were used to quell an uprising among the black settlers from Nova Scotia and London. After eight years, they were unhappy with their treatment by the Sierra Reynolds Company

Sierra (Spanish for " mountain range" and "saw", from Latin '' serra'') may refer to the following:

Places Mountains and mountain ranges

* Sierra de Juárez, a mountain range in Baja California, Mexico

* Sierra de las Nieves, a mountain range ...

.

Abolition of slavery

The Canadian climate made it uneconomic to keep enslaved African people year-round, unlike the

The Canadian climate made it uneconomic to keep enslaved African people year-round, unlike the plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Th ...

agriculture practised in the southern United States and Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean ...

. Slavery within the colonial economy became increasingly rare. For example, the powerful Mohawk Mohawk may refer to:

Related to Native Americans

* Mohawk people, an indigenous people of North America (Canada and New York)

*Mohawk language, the language spoken by the Mohawk people

* Mohawk hairstyle, from a hairstyle once thought to have been ...

leader Joseph Brant

Thayendanegea or Joseph Brant (March 1743 – November 24, 1807) was a Mohawk military and political leader, based in present-day New York, who was closely associated with Great Britain during and after the American Revolution. Perhaps ...

purchased and enslaved an African American named Sophia Burthen Pooley, whom he kept for about 12 years before selling her for $100.Black History in Guelph and Wellington CountyIn 1772, prior to the American Revolution, Britain outlawed the slave trade in the British Isles followed by the ''

Knight v. Wedderburn

Joseph Knight (''fl.'' 1769–1778) was a man born in Guinea (the general name of West Africa) and there seized into slavery. It appears that the captain of the ship which brought him to Jamaica there sold him to John Wedderburn of Ballindean, S ...

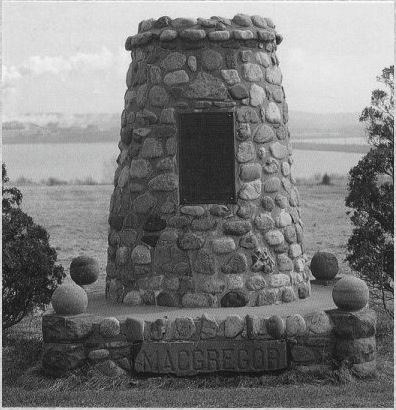

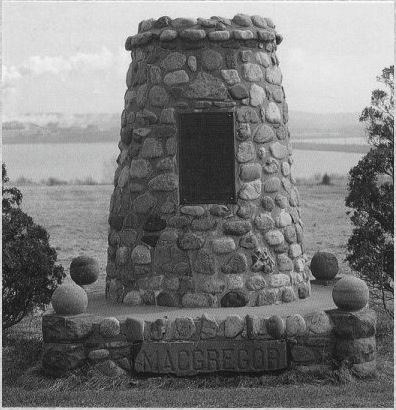

'' decision in Scotland in 1778. This decision, in turn, influenced the colony of Nova Scotia. In 1788, abolitionist James Drummond MacGregor

Rev. James Drummond MacGregor ( gd, an t-Urr. Seumas MacGriogar) (December 1759 – 3 March 1830) was an author of Christian poetry in both Scottish and Canadian Gaelic, an abolitionist and Presbyterian minister in Nova Scotia, Canada.

Life and ...

from Pictou published the first anti-slavery literature in Canada and began purchasing slaves' freedom and chastising his colleagues in the Presbyterian church who owned slaves.

In 1790 John Burbidge

John Burbidge (c.1718 – March 11, 1812) was a soldier, land owner, judge and political figure in Nova Scotia. He was a member of the 1st General Assembly of Nova Scotia in 1758 and represented Halifax Township from 1759 to 1765 and Cornwa ...

freed the African people he had enslaved. Led by Richard John Uniacke

Richard John Uniacke (November 22, 1753 – October 11, 1830) was an abolitionist, lawyer, politician, member of the Nova Scotia House of Assembly and Attorney General of Nova Scotia. According to historian Brian Cutherburton, Uniacke was "t ...

, in 1787, 1789 and again on 11 January 1808, the Nova Scotian legislature refused to legalize slavery. Two chief justices, Thomas Andrew Lumisden Strange

Sir Thomas Andrew Lumisden Strange (30 November 1756 – 16 July 1841) was a chief justice in Nova Scotia, known for waging "judicial war" to free Black Nova Scotian slaves from their owners. From 1789 to 1797, he was the sixth Chief Justice ...

(1790–1796) and Sampson Salter Blowers

Sampson Salter Blowers (March 10, 1742 – October 25, 1842) was a noted North American lawyer, Loyalist and jurist from Nova Scotia who, along with Chief Justice Thomas Andrew Lumisden Strange, waged "judicial war" in his efforts to free B ...

(1797–1832) were instrumental in freeing enslaved Africans from their enslavers (owners) in Nova Scotia. These justices were held in high regard in the colony.

In 1793, John Graves Simcoe

John Graves Simcoe (25 February 1752 – 26 October 1806) was a British Army general and the first lieutenant governor of Upper Canada from 1791 until 1796 in southern Ontario and the watersheds of Georgian Bay and Lake Superior. He founded Yor ...

, the first Lieutenant-Governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a " second-in-co ...

of Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a Province, part of The Canadas, British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North Americ ...

, attempted to abolish slavery. That same year, the new Legislative Assembly became the first entity in the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

to restrict slavery, confirming existing ownership but allowing for anyone born to an enslaved woman or girl after that date to be freed at the age of 25. Slavery was all but abolished throughout the other British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestow ...

n colonies by 1800. The Slave Trade Act

Slave Trade Act is a stock short title used for legislation in the United Kingdom and the United States that relates to the slave trade.

The "See also" section lists other Slave Acts, laws, and international conventions which developed the c ...

outlawed the slave trade in the British Empire in 1807 and the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 outlawed slave-holding altogether in the colonies (except for India). This made Canada an attractive destination for many African descendant refugees fleeing slavery in the United States, such as minister Boston King Boston King ( 1760–1802) was a former American slave and Black Loyalist, who gained freedom from the British and settled in Nova Scotia after the American Revolutionary War. He later immigrated to Sierra Leone, where he helped found Freetown and b ...

.

War of 1812

The next major migration of Black people occurred between 1813 and 1815. Refugees from theWar of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

, primarily from the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the Eastern Shore of Maryland / ...

and Georgia Sea Islands

The Sea Islands are a chain of tidal and barrier islands on the Atlantic Ocean coast of the Southeastern United States. Numbering over 100, they are located between the mouths of the Santee and St. Johns Rivers along the coast of South Caroli ...

, fled the United States to settle in Hammonds Plains, Beechville, Lucasville, North Preston

North Preston is a community located in Nova Scotia, Canada within the Halifax Regional Municipality.

The community is populated primarily by Black Nova Scotians. North Preston is the largest Black community in Nova Scotia by population, and ...

, East Preston, Africville

Africville was a small community of predominantly African Nova Scotians located in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. It developed on the southern shore of Bedford Basin and existed from the early 1800s to the 1960s. From 1970 to the present, a prote ...

and Elm Hill, New Brunswick. An April 1814 proclamation of Black freedom and settlement by British Vice-Admiral Alexander Cochrane

Admiral of the Blue Sir Alexander Inglis Cochrane (born Alexander Forrester Cochrane; 23 April 1758 – 26 January 1832) was a senior Royal Navy commander during the Napoleonic Wars and achieved the rank of admiral.

He had previously captain ...

led to an exodus of around 3,500 Black Americans by 1818. The settlement of the refugees was initially seen as a means of creating prosperous agricultural communities; however, poor economic conditions following the war coupled with the granting of infertile farmland to refugees caused economic hardship. Social integration proved difficult in the early years, as the prevalence of enslaved Africans in the Maritimes caused the newly freed Black Canadians to be viewed on the same level of the enslaved. Politically, the black Loyalist communities in both Nova Scotia and Upper Canada were characterized by what the historian James Walker called "a tradition of intense loyalty to Britain" for granting them freedom and Canadian Black people tended to be active in the militia, especially in Upper Canada during the War of 1812 as the possibility of an American victory would also mean the possibility of their re-enslavement. Militarily, a Black Loyalist

Black Loyalists were people of African descent who sided with the Loyalists during the American Revolutionary War. In particular, the term refers to men who escaped enslavement by Patriot masters and served on the Loyalist side because of the C ...

named Richard Pierpoint

Richard Pierpoint (Bundu – Canada ), also known as Black Dick, Captain Dick, Captain Pierpoint, Pawpine, and Parepoint was a British soldier of Senegalese descent. Brought to America as a slave, he was granted freedom to fight on the side of t ...

, who was born about 1744 in Senegal and who had settled near present-day St. Catharines

St. Catharines is the largest city in Canada's Niagara Region and the sixth largest urban area in the province of Ontario. As of 2016, it has an area of , 136,803 residents, and a metropolitan population of 406,074. It lies in Southern Ontari ...

, Ontario, offered to organize a Corps of Men of Colour to support the British war effort. This was refused but a white officer raised a small black corps. This "Coloured Corps" fought at Queenston Heights

The Queenston Heights is a geographical feature of the Niagara Escarpment immediately above the village of Queenston, Ontario, Canada. Its geography is a promontory formed where the escarpment is divided by the Niagara River. The promontory form ...

and the siege of Fort George, defending what would become Canada from the invading American army. Many of the refugees from America would later serve with distinction during the war in matters both strictly military, along with the use of freed African people in assisting in the further liberation of African Americans enslaved people.

Underground Railroad

There is a sizable community of Black Canadians in Nova Scotia andSouthern Ontario

Southern Ontario is a primary region of the province of Ontario, Canada, the other primary region being Northern Ontario. It is the most densely populated and southernmost region in Canada. The exact northern boundary of Southern Ontario is disp ...

who trace their ancestry to African-American slaves who used the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. ...

to flee from the United States, seeking refuge and freedom in Canada. From the late 1820s, through the time that the United Kingdom itself forbade slavery in 1833, until the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

began in 1861, the Underground Railroad brought tens of thousands of fugitive slave

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th century to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called freed ...

s to Canada. In 1819, Sir John Robinson, the Attorney-General of Upper Canada, ruled: "Since freedom of the person is the most important civil right protected by the law of England...the negroes are entitled to personal freedom through residence in Upper Canada and any attempt to infringe their rights will be resisted in the courts". After Robinson's ruling in 1819, judges in Upper Canada refused American requests to extradite run-away slaves who reached Upper Canada under the grounds "every man is free who reaches British ground". One song popular with African Americans called the ''Song of the Free

"Song of the Free" is a song of the Underground Railroad written circa 1860 about a man fleeing slavery in Tennessee by escaping to Canada via the Underground Railroad. It has eight verses and is composed to the tune of " Oh! Susanna".

Lyrics

...

'' had the lyrics: "I'm on my way to Canada, That cold and distant land, The dire effects of slavery, I can no longer stand, Farewell, old master, Don't come after me, I'm on my way to Canada, Where colored men are free!".

In 1850, the United States Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act

A fugitive (or runaway) is a person who is fleeing from custody, whether it be from jail, a government arrest, government or non-government questioning, vigilante violence, or outraged private individuals. A fugitive from justice, also know ...

, which gave bounty hunters the right to recapture run-away slaves anywhere in the United States and ordered all federal, state and municipal law enforcement to co-operate with the bounty hunters in seizing run-away slaves.Hill, Daniel ''The Freedom-Seekers'', Agincourt: Book Society of Canada, 1981 p. 32. Since the Fugitive Slave Act stripped accused fugitive slaves of any legal rights such as the right to testify in court that they were not run-away slaves, cases of freemen and freewomen being kidnapped off the streets to be sold into slavery became common. The U.S. justice system in the 1850s was hostile to black people, and little inclined to champion their rights. In 1857, in the Dred Scott v. Sandford

''Dred Scott v. Sandford'', 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that held the U.S. Constitution did not extend American citizenship to people of black African descent, enslaved or free; th ...

decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that black Americans were not and never could be U.S. citizens under any conditions, a ruling that appeared to suggest that laws prohibiting slavery in the northern states were unconstitutional.

As a result of the Fugitive Slave Act and legal rulings to expand slavery in the United States, many free blacks living in the United States chose to seek sanctuary in Canada with one newspaper in 1850 mentioning that a group of blacks working for a Pittsburgh hotel had armed themselves with handguns before heading for Canada saying they were "...determined to die rather be captured". The ''Toronto Colonist'' newspaper on 17 June 1852 noted that almost every ship or boat coming into Toronto harbor from the American side of Lake Ontario seemed to be carrying a run-away slave. One of the more active "conductors" on the Underground Railroad was Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman (born Araminta Ross, March 10, 1913) was an American abolitionist and social activist. Born into slavery, Tubman escaped and subsequently made some 13 missions to rescue approximately 70 slaves, including family and friends, u ...

, the "Black Moses" who made 11 trips to bring about 300 run-away slaves to Canada, most of whom settled in St. Catherines. Tubman guided her "passengers" on nocturnal journeys (travelling via day was too risky) through the forests and swamps, using as her compass the north-star and on cloudy nights seeing what side the moss was growing on trees, to find the best way to Canada.Hill, Daniel ''The Freedom-Seekers'', Agincourt: Book Society of Canada, 1981 p. 38. Such trips on the Underground Railroad involved much privation and suffering as Tubman and her "passengers" had to avoid both the bounty-hunters and law enforcement and could go for days without food as they travelled through the wilderness, always following the north-star. Tubman usually went to Rochester, New York, where Frederick Douglass would shelter the run-aways, and crossed over to Canada at Niagara Falls. Unlike the U.S. customs, which under the Fugitive Slave Act had to co-operate with the bounty hunters, the customs authorities on the Canadian side of the border were far more helpful and "looked the other way" when Tubman entered Canada with her "passengers".

During the course of one week in June 1854, 23 run-away slaves evaded the U.S. border patrols to cross the Detroit river to freedom in Windsor while 43 free people also crossed over to Windsor out of the fear of the bounty hunters. The American-born Canadian sociologist Daniel G. Hill wrote this week in June 1854 appeared to be typical of the black exodus to Canada. Public opinion tended to be on the side of run-away slaves and against the slavers. On 26 February 1851, the Toronto chapter of the Anti-Slavery Society was founded with what was described by the ''Globe'' newspaper as "the largest and most enthusiastic meeting we have ever seen in Toronto" that issued the resolution: "slavery is an outrage on the laws of humanity and its continued practice demands the best exertions for its extinction".Hill, Daniel ''The Freedom-Seekers'', Agincourt: Book Society of Canada, 1981 p. 20. The same meeting committed its members to help the many "houseless and homeless victims of slavery flying to our soil". The Congregationalist minister, the Reverend

During the course of one week in June 1854, 23 run-away slaves evaded the U.S. border patrols to cross the Detroit river to freedom in Windsor while 43 free people also crossed over to Windsor out of the fear of the bounty hunters. The American-born Canadian sociologist Daniel G. Hill wrote this week in June 1854 appeared to be typical of the black exodus to Canada. Public opinion tended to be on the side of run-away slaves and against the slavers. On 26 February 1851, the Toronto chapter of the Anti-Slavery Society was founded with what was described by the ''Globe'' newspaper as "the largest and most enthusiastic meeting we have ever seen in Toronto" that issued the resolution: "slavery is an outrage on the laws of humanity and its continued practice demands the best exertions for its extinction".Hill, Daniel ''The Freedom-Seekers'', Agincourt: Book Society of Canada, 1981 p. 20. The same meeting committed its members to help the many "houseless and homeless victims of slavery flying to our soil". The Congregationalist minister, the Reverend Samuel Ringgold Ward

Samuel Ringgold Ward (October 17, 1817 – ) was an African American who escaped enslavement to become an abolitionist, newspaper editor, labor leader, and Congregational church minister.

He was author of the influential book ''Autobiograph ...

of New York, who had been born into slavery in Maryland, wrote about Canada West (modern Ontario) that: "Toronto is somewhat peculiar in many ways, anti-slavery is more popular there than in any city I know save Syracuse...I had good audiences in the towns of Vaughan, Markham, Pickering and in the village of Newmarket. Anti-slavery feeling is spreading and increasing in all these places. The public mind literally thirsts for the truth, and honest listeners and anxious inquirers will travel many miles, crowd our country chapels, and remain for hours eagerly and patiently seeking the light". Ward himself had been forced to flee to Canada West in 1851 for his role in the Jerry Rescue

The Jerry Rescue occurred on October 1, 1851, and involved the public rescue of a fugitive slave who had been arrested the same day in Syracuse, New York, during the anti-slavery Liberty Party's state convention. The escaped slave was William ...

, leading to his indictment for violating the Fugitive Slave Act. Despite the support to run-away slaves, blacks in Canada West, which become Ontario in 1867, were confined to segregated schools.