Battle of Siffin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Siffin was fought in 657 CE (37 AH) between

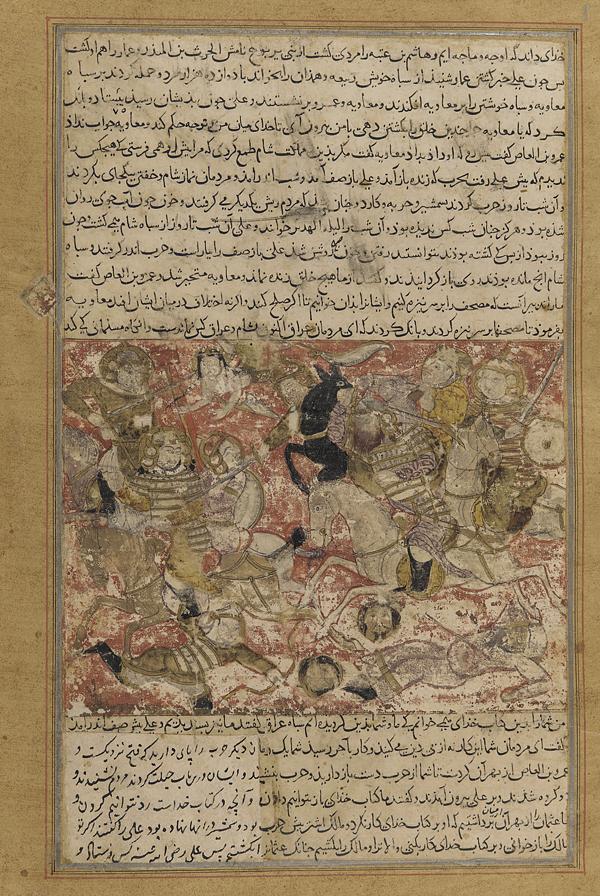

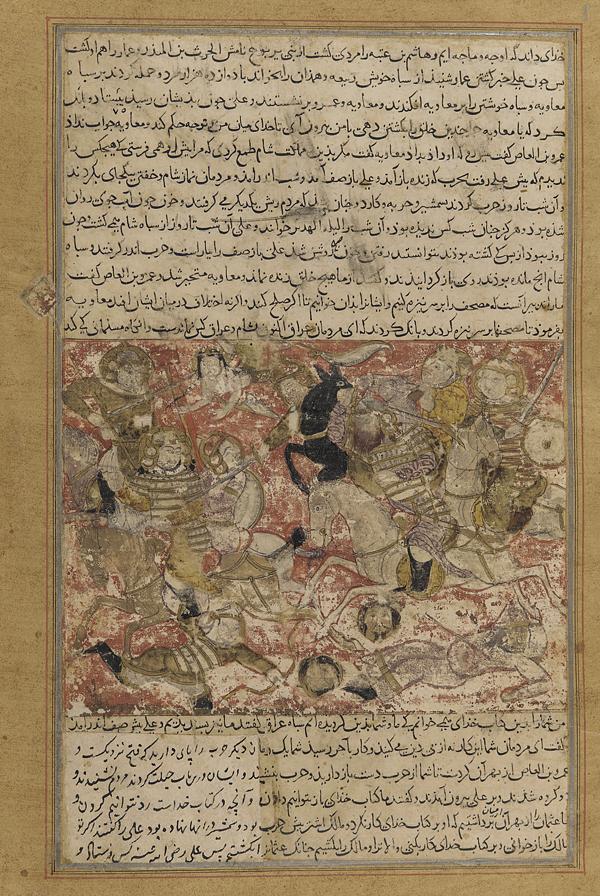

Historical materials are abundant about the Battle of Siffin, though they mostly describe disconnected episodes of the war. Lecker and Wellhausen have thus found it impossible to establish the course of the battle. Nevertheless, the battle began on Wednesday, 26 July 657, and continued to Friday or Saturday morning. Ali fought with his men on the frontline while Mu'awiya led from his pavilion. At the end of the first day, having pushed back Ali's right-wing, Mu'awiya had fared better overall.

On the second day, Mu'awiya concentrated his assault on Ali's left wing but the tide turned and the Syrians were pushed back. Mu'awiya fled his pavilion and took shelter in an army tent. On this day,

Historical materials are abundant about the Battle of Siffin, though they mostly describe disconnected episodes of the war. Lecker and Wellhausen have thus found it impossible to establish the course of the battle. Nevertheless, the battle began on Wednesday, 26 July 657, and continued to Friday or Saturday morning. Ali fought with his men on the frontline while Mu'awiya led from his pavilion. At the end of the first day, having pushed back Ali's right-wing, Mu'awiya had fared better overall.

On the second day, Mu'awiya concentrated his assault on Ali's left wing but the tide turned and the Syrians were pushed back. Mu'awiya fled his pavilion and took shelter in an army tent. On this day,

By the next morning, the balance had moved in Ali's favor. Before noon, however, some of the Syrians raised pages of the Quran on their lances, shouting, "Let the Book of God be the judge between us." The fighting stopped at once. By this point, Ali is estimated to have lost 25,000 men, while Mu'awiya is said to have lost 45,000.

By the next morning, the balance had moved in Ali's favor. Before noon, however, some of the Syrians raised pages of the Quran on their lances, shouting, "Let the Book of God be the judge between us." The fighting stopped at once. By this point, Ali is estimated to have lost 25,000 men, while Mu'awiya is said to have lost 45,000.

Mu'awiya then conveyed his proposal that representatives from both sides should together reach a binding solution on the basis of the Quran. Crucially, he was silent at this point on Uthman's revenge and a for a new caliph. Mu'awiya's proposal was accepted by the majority of Ali's army, reports

Mu'awiya then conveyed his proposal that representatives from both sides should together reach a binding solution on the basis of the Quran. Crucially, he was silent at this point on Uthman's revenge and a for a new caliph. Mu'awiya's proposal was accepted by the majority of Ali's army, reports

The seceders adopted the slogan, "No judgment but that of God," highlighting their rejection of the arbitration (by men) possibly based on verse 49:9, "If two parties of the Believers fight with one another, make peace between them; but if one rebels against the other, then fight against the one that rebels, until they return to obedience to God." When they interrupted Ali's sermon with this slogan, he commented that it was a word of truth by which the seceders sought falsehood. He added that they were repudiating government while a ruler was indispensable in the conduct of religion. Ali nevertheless did not bar their entry to mosques or deprive them of their shares in the treasury, saying that they should be fought only if they initiate the hostilities.

The seceders adopted the slogan, "No judgment but that of God," highlighting their rejection of the arbitration (by men) possibly based on verse 49:9, "If two parties of the Believers fight with one another, make peace between them; but if one rebels against the other, then fight against the one that rebels, until they return to obedience to God." When they interrupted Ali's sermon with this slogan, he commented that it was a word of truth by which the seceders sought falsehood. He added that they were repudiating government while a ruler was indispensable in the conduct of religion. Ali nevertheless did not bar their entry to mosques or deprive them of their shares in the treasury, saying that they should be fought only if they initiate the hostilities.

Ali ibn Abi Talib

ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib ( ar, عَلِيّ بْن أَبِي طَالِب; 600 – 661 CE) was the last of four Rightly Guided Caliphs to rule Islam (r. 656 – 661) immediately after the death of Muhammad, and he was the first Shia Imam. ...

, the fourth of the Rashidun Caliphs and the first Shia Imam

In Shia Islam, the Imamah ( ar, إمامة) is a doctrine which asserts that certain individuals from the lineage of the Islamic prophet Muhammad are to be accepted as leaders and guides of the ummah after the death of Muhammad. Imamah further ...

, and Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan, the rebellious governor of Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

. The battle is named after its location Siffin on the banks of the Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

. The fighting stopped after the Syrians called for arbitration to escape defeat, to which Ali agreed under pressure from some of his troops. The arbitration process ended inconclusively in 658 though it strengthened the Syrians' support for Mu'awiya and weakened the position of Ali. The battle is considered part of the First Fitna

The First Fitna ( ar, فتنة مقتل عثمان, fitnat maqtal ʻUthmān, strife/sedition of the killing of Uthman) was the first civil war in the Islamic community. It led to the overthrow of the Rashidun Caliphate and the establishment of ...

and a step towards the establishment of the Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by th ...

.

Location

The battlefield was at Siffin, a ruinedByzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

-era village situated a few hundred yards from the right bank of the Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

in the vicinity of Raqqa

Raqqa ( ar, ٱلرَّقَّة, ar-Raqqah, also and ) ( Kurdish: Reqa/ ڕەقە) is a city in Syria on the northeast bank of the Euphrates River, about east of Aleppo. It is located east of the Tabqa Dam, Syria's largest dam. The Hellenistic, ...

in present-day Syria. It has been identified with the modern village of Abu Hureyra

Tell Abu Hureyra ( ar, تل أبو هريرة) is a prehistoric archaeological site in the Upper Euphrates valley in Syria. The tell was inhabited between 13,000 and 9,000 years ago in two main phases: Abu Hureyra 1, dated to the Epipalaeolithi ...

in the Raqqa Governorate

Raqqa Governorate ( ar, مُحافظة الرقة, Muḥāfaẓat ar-Raqqah) is one of the fourteen governorates of Syria. It is situated in the north of the country and covers an area of 19,618 km2. The capital is Raqqa. The Islamic State ...

.

Background

Opposition to Uthman

Ali and other senior companions frequently accused the third caliphUthman

Uthman ibn Affan ( ar, عثمان بن عفان, ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān; – 17 June 656), also spelled by Colloquial Arabic, Turkish and Persian rendering Osman, was a second cousin, son-in-law and notable companion of the Islamic prop ...

() of deviating from the Quran and Sunna (prophetic precedence). Uthman was also widely accused of nepotism and corruption, and Ali is known to have protested Uthman's nepotism and his lavish gifts for his kinsmen. Ali also often protected outspoken and upright companions against the caliph's wrath. These included Abu Dharr and Ammar.

Among those actively opposing Uthman were some supporters of Ali, who might have wanted to see Ali as the next caliph, though there is no evidence that he communicated or coordinated with them. Notable among them was Malik al-Ashtar, a leader of the religiously-learned (). Ali is said to have rejected the requests to lead the rebels, though he likely sympathized with their grievances about injustice.

Assassination of Uthman

As their grievances mounted, discontented groups from provinces began arriving in Medina in 35/656. On their first attempt, the Egyptian opposition sought the advice of Ali, who urged them to send a delegation to negotiate with Uthman, unlike companions Talha and Ammar who are said to have encouraged the Egyptians to advance on the town. Ali similarly asked the Iraqi opposition to avoid violence, which was heeded. Ali also acted as a mediator between Uthman and the provincial dissidents on more than one occasion to address their economical and political grievances. In particular, he was a guarantor for Uthman's promises to the opposition though he later declined to intervene further when the Egyptians intercepted an official letter ordering their punishment upon their return to Egypt. Uthman was assassinated shortly afterward in 656 by the Egyptian rebels in a raid on his residence in Medina.Ali's involvement

Ali played no role in the fatal attack, and his son Hasan was injured while standing guard at Uthman's besieged residence at the request of Ali. He also convinced the rebels not to prevent the delivery of water to Uthman's residence during the siege. Beyond this, historians seem to disagree about Ali's measures to protect the third caliph. Jafri and Madelung highlight Ali's multiple attempts for reconciliation during the two sieges, andHinds Hinds may refer to:

Deer, especially does

*Deer

People with the surname Hinds:

*Hinds (surname)

In places:

* Hinds, New Zealand, a small town

* Hinds County, Mississippi, a US county

*Hinds Lake, a lake in Minnesota

*Hinds River, a river that flo ...

believes that Ali could not have done anything more for Uthman, supporting whom would have meant supporting the infamous Umayyads. Donner and Gleave suggest that Ali was the immediate beneficiary of Uthman's death, though this is challenged by Madelung, who observes that Aisha would have not actively undermined Uthman's regime if Ali had been the prime mover of the rebellion and its future beneficiary. He and others note the deep-seated enmity of Aisha for Ali, which resurfaced immediately after his accession.

On the other extreme, Veccia Vaglieri believes that Ali did not defend the caliph, and Caetani goes further, labeling Ali as the chief culprit in Uthman's assassination, even though the evidence suggests otherwise.

Election of Ali

After Uthman's assassination, his tribesmen (the Umayyads) fled Medina, and the rebels and their Medinan allies controlled the city. While Talha enjoyed some support among the Egyptian rebels, Ali was preferred by most of the Ansar (early Medinan Muslims) and the Iraqi dissidents, who had earlier heeded Ali's opposition to the use of violence. Some historians add the (prominent)Muhajirun

The ''Muhajirun'' ( ar, المهاجرون, al-muhājirūn, singular , ) were the first converts to Islam and the Islamic prophet Muhammad's advisors and relatives, who emigrated with him from Mecca to Medina, the event known in Islam as the '' Hij ...

(early Meccan

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow valle ...

Muslims) to the above list of Ali's supporters.

The caliphate was thus offered by these groups to Ali, who was initially reluctant to accept it, possibly wary of implicating himself in Uthman's regicide by becoming the next caliph. Ali eventually accepted the role, and some authors suggest that he did so to prevent further chaos and compelled by popular pressure. For others, that Ali allowed himself to be nominated by the rebels was an error because it left him exposed to accusations of complicity in Uthman's assassination.

Uthman's governors

At the time of Uthman's assassination, the key governorships were all in the hands of his tribesmen, the late conversion of most of whom to Islam smacked of expediency to Ali and the Ansar. Ali was nevertheless advised to initially confirm these governors, some of whom were unpopular, to consolidate his caliphate. He rejected this and replaced nearly all those who had served Uthman, saying that the likes of those men should not be appointed to any office. In this and other decisions, Ali was driven by his sense of religious mission, writes Madelung, while Poonawala suggests that Ali changed the governors to please the rebels. Donner has a similar view to Madelung and Shah-Kazemi maintains that justice was the key principle that molded Ali's policies in all domains. Among these governors was Uthman's cousin Mu'awiya, who had been appointed as the governor of Syria by the second caliphUmar

ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb ( ar, عمر بن الخطاب, also spelled Omar, ) was the second Rashidun caliph, ruling from August 634 until his assassination in 644. He succeeded Abu Bakr () as the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate ...

and then reconfirmed by Uthman. Having ruled Syria for almost twenty years without interruption almost since its conquest, Mu'awiya had a power base in Syria which made his removal difficult.

Mu'awiya's revolt

Removal of Mu'awiya

While there are some reports of early correspondence, Madelung suggests that Ali only contacted Mu'awiya after arriving in Kufa following his victory in theBattle of the Camel

The Battle of the Camel, also known as the Battle of Jamel or the Battle of Basra, took place outside of Basra, Iraq, in 36 AH (656 CE). The battle was fought between the army of the fourth caliph Ali, on one side, and the rebel army led by ...

. He waited possibly to have the upper hand after his victory and because Mu'awiya was not a serious contender for the caliphate anyway, considering that he was a (those pardoned by Muhammad when Mecca fell), the son of Abu Sufyan, who had led the confederates against Muslims, and Hind, who was responsible for mutilating the body of Muhammad's uncle Hamza

Hamza ( ar, همزة ') () is a letter in the Arabic alphabet, representing the glottal stop . Hamza is not one of the 28 "full" letters and owes its existence to historical inconsistencies in the standard writing system. It is derived from ...

.

In Kufa, Ali dispatched Jarir ibn Abd Allah al-Bajali with a letter to Mu'awiya that demanded his pledge of allegiance and made it clear that Mu'awiya would be dismissed from his post afterward. The caliph argued in his letter that his election in Medina was binding on Mu'awiya in Syria because he was elected by the same people who had pledged to his predecessors. According to ''Waq'at Siffin'', the letter added that the election of the caliph was the right of the Muhajiran and the Ansar, thus explicitly excluding Mu'awiya as a late convert (). The letter also urged Mu'awiya to leave justice for Uthman to Ali, promising that he would deal with the issue in due course. By this point, Mu'awiya had already publicly charged Ali with Uthman's murder and forged a letter from Ali's governor of Egypt to himself in which the governor supported Mu'awiya's right for revenge.

In response, Mu'awiya asked Jarir for time to "explore the view of the people of Syria." He then addressed the congregation at the next prayer, appealed to their Syrian patriotism, and received their pledge as to revenge Uthman. He soon launched a propaganda campaign in Syria, charging Ali with Uthman's murder and calling for revenge.

Mu'awiya's alliance against Ali

Mu'awiya also immediately wrote toAmr ibn al-As

( ar, عمرو بن العاص السهمي; 664) was the Arab commander who led the Muslim conquest of Egypt and served as its governor in 640–646 and 658–664. The son of a wealthy Qurayshite, Amr embraced Islam in and was assigned impo ...

to join him in Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

, possibly to draw on his political and military expertise or perhaps hoping that he would bring the neighboring Egypt under Mu'awiya's rule after failing to intimidate Ali's governor of Egypt to switch sides. Amr was believed to be an illegitimate child of Abu Sufyan, who had conquered and governed Egypt but was later removed by Uthman. He incited rebellion against the caliph after his dismissal and later publicly took some credit for Uthman's murder by the Egyptian rebels. However, Amr soon changed his tone and pinned the murder on Ali, possibly fearing the Umayyad's wrath or because he could have not hoped for a post in Ali's government.

After arriving in Damascus, Amr publicly swore allegiance to Mu'awiya in 657 and promised to back the Umayyads against Ali in return for the life-long governorship of Egypt. This pact thus turned a prime suspect in Uthman's murder into his public prosecutor and also later gave rise to the stories recorded by al-Baladhuri

ʾAḥmad ibn Yaḥyā ibn Jābir al-Balādhurī ( ar, أحمد بن يحيى بن جابر البلاذري) was a 9th-century Muslim historian. One of the eminent Middle Eastern historians of his age, he spent most of his life in Baghdad and e ...

(), al-Ya'qubi

ʾAbū l-ʿAbbās ʾAḥmad bin ʾAbī Yaʿqūb bin Ǧaʿfar bin Wahb bin Waḍīḥ al-Yaʿqūbī (died 897/8), commonly referred to simply by his nisba al-Yaʿqūbī, was an Arab Muslim geographer and perhaps the first historian of world cult ...

(), and others in which Amr privately confesses to selling his religion for worldly gain.

Mu'awiya also brought into his camp the influential Syrian Shurahbil ibn Simt, whom he convinced with false witnesses and reports that Ali was guilty of Uthman's murder. Moreover, Mu'awiya reached out to the "religious aristocracy" in Mecca and Medina, though al-Miswar ibn Makhrama

Al-Miswar ibn Makhrama ( ar, المسور بن مخرمة) was a companion ( Sahabah) of the Islamic prophet, Muhammad, and a Hadith narrator.Dr. Teebaye Morsdhun, ''Numbers and Mathematical Concepts in Islam'', p.118

References

Sahabah hadi ...

refused to support him on behalf of the people of the holy cities, asking Mu'awiya in a letter what a whose father had led the confederate armies against Muslims had to do with the caliphate. Mu'awiya did, however, win to his side Ubayd Allah Ubayd Allah ( ar, عبيد الله), also spelled or transliterated Obaidullah, Obaydullah, Obeidallah, or Ubaydullah, is a male Arabic given name that means "little servant of God".

Given name Obaidullah

* Obaidullah (detainee), an Afghan detaine ...

, son of the second caliph Umar and a triple murderer, who had fled after learning that Ali would apply the ''lex talionis

"An eye for an eye" ( hbo, עַיִן תַּחַת עַיִן, ) is a commandment found in the Book of Exodus 21:23–27 expressing the principle of reciprocal justice measure for measure. The principle exists also in Babylonian law.

In Roman c ...

'' to him.

Mu'awiya's proposal to Ali

Mu'awiya soon visited Ali's messenger Jarir privately and proposed that he would recognize Ali as the caliph in return for Syria and Egypt and their revenues during the caliphates of Ali and his successor. The major historical accounts are unaware of this proposal, which is nevertheless mentioned in a poem byal-Walid ibn Uqba

Al-Walīd ibn ʿUqba ibn Abī Muʿayṭ ( ar, الْوَلِيْد ابْنِ عُقبَة ابْنِ أَبِيّ مُعَيْط, died 680) was the governor of Kufa in 645/46–649/50 during the reign of his half-brother, Caliph Uthman ().

Durin ...

, who was close to Mu'awiya. The latter kept this proposal secret evidently because it contradicted the public statements that his goal was to revenge Uthman. Jarir conveyed this proposal to Ali in a letter, who rejected it, possibly perceiving the proposal as a stratagem for Mu'awiya to take over the caliphate step by step. Alternatively, had Ali accepted Mu'awiya's proposal, the Islamic territory might have been irreversibly divided into two parts, suggests McHugo.

Mu'awiya's declaration of war

Mu'awiya now sent Jarir back to Kufa with a formal declaration of war, which charged Ali with Uthman's murder and stated that the Syrians would fight Ali until he surrendered Uthman's murderers. Then there would be a Syrian council () to elect the next caliph, the declaration continued. Ali replied to this letter, saying that he was innocent and that Mu'awiya's accusations lacked any evidence. He also challenged Mu'awiya to name any Syrian who would qualify to vote in a . As for handing Uthman's killers to Mu'awiya, Ali asked the latter to pledge allegiance and then present his case before Ali's court.Views

Accusations

Contemporary authors hold that Mu'awiya either defied Ali after he deposed him or conditioned his pledge to Ali on Uthman's revenge, knowing that Ali would dismiss him after giving his oath. With the exception of Kennedy, who believes that Mu'awiya was sincerely seeking justice for Uthman, modern authors also tend to view Mu'awiya's claim of revenge as a pretext for initially maintaining his rule over Syria or for seizing the caliphate later. For McHugo, this view is corroborated by Mu'awiya's secret offer to recognize Ali's caliphate in return for Syria and Egypt. Some authors regard the call for revenge as a pious cloak for broader issues: Hinds and Poonawala trace back Mu'awiya's revolt to his demands to rule over an autonomous Syria, which was kept free (unlike Iraq) from uncontrolled immigration to check the Byzantine threats. In contrast, after the Byzantines' defeats, Ali might have expected all provinces to equally share the burden of immigration. Shaban has a similar view. Verse 17:33 of the Quran was cited by Mu'awiya to justify Uthman's revenge, "If anyone is killed wrongfully, We give his next-of-kin authority, but let him not be extravagant in killing, surely he is being helped," though Madelung suggests that the clause "let him not be extravagant in killing" was later ignored in the "frenzy of patriotic self-righteousness" created by Mu'awiya. Mu'awiya's other justification for revolting against Ali was that he had not participated in the election of Ali or that the rebels were involved in the election. At the same time, the emphasis of Mu'awiya on a Syrian for Ali's successor was likely to ensure his own caliphate. Madelung adds here that Mu'awiya designated his son Yazid as his successor without any altogether.Ali's position

Ali was openly critical of Uthman's conduct, though he generally neither justified his violent death nor condemned the killers. Ali likely held Uthman responsible through his injustice for the protests which led to his death in an act of war. Madelung sides with Ali's judgement from a judicial point of view. Still, Ali insisted (in his letters to Mu'awiya and elsewhere) that he would bring the murderers to justice in due course. In particular, closely associated with Ali was Malik al-Ashtar, a leader of the (), who supported Ali. Al-Ashtar had led the Kufan delegation against Uthman, though they heeded Ali's call for nonviolence and did not participate in the siege of Uthman's residence. Some others among the were similarly implicated by Mu'awiya in Uthman's murder. As such, some authors suggest that Ali was unwilling or unable to punish these individuals.Counter-accusations

Other authors have instead implicated Mu'awiya or his close associates in Uthman's murder. Madelung writes that Mu'awiya's close ally Amr ibn al-As had earlier publicly taken some credit for Uthman's murder. It is also commonly believed thatMarwan

Marwan, Merwan or Mervan ( ar, مروان ''marwān''), is an Arabic male given name derived from the word ''marū/ maruw'' (مرو) with the meaning of either minerals, "flint(-stone)", "quartz" or "a hard stone of nearly pure silica". However, ...

was responsible for the intercepted instructions to punish the rebels that set off the second siege, but Hazleton and Abbas further suggest that Marwan did so at the instigation of Mu'awiya. Abbas and the Shia Tabatabai also allege that Mu'awiya deliberately withheld the reinforcements requested by the besieged Uthman shortly before his murder. Lastly, Tabatabai writes that Mu'awiya did not pursue Uthman's vengeance during his caliphate.

Preparations

Iraq

In Iraq, Ali called a council of the Muhajirun and the Ansar who unanimously urged him to fight Mu'awiya after the latter declared war. The Kufans were less united in supporting the war, either simply because of its expected toll, or because they were reluctant to shed other Muslims' blood, or perhaps because the Syrians had never pledged allegiance to Ali in the first place, even though similar cases had been interpreted as apostasy byAbu Bakr

Abu Bakr Abdallah ibn Uthman Abi Quhafa (; – 23 August 634) was the senior companion and was, through his daughter Aisha, a father-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, as well as the first caliph of Islam. He is known with the honor ...

. Ali also barred his followers from cursing the Syrians, saying that it might jeopardize any remaining hopes to avoid war.

Syria

In Syria, Uthman's bloody shirt was taken from town to town to incite the people to revenge, though the support for the war was also not unanimous there. Mua'wiya secured the Byzantine borders by agreeing to a truce at the cost of a "humiliating" tribute to them. He also left the protection of his western borders to three local Palestinian commanders, probably becauseMuhammad ibn Abu Bakr

Muḥammad ibn Abī Bakr ( ar, محمد بن أبي بكر, 631–658), was the youngest son of the first Islamic caliph Abu Bakr. His mother was Asma bint Umais, who was a widow of Ja'far ibn Abi Talib prior to her second marriage with Abu Bakr. ...

faced internal problems as Ali's new governor of Egypt.

Comparisons

Siffin is described in Arabic sources as a conflict between the people of Iraq and Syria, in which most tribes were represented on both sides. The number of troops is uncertain. For instance, both armies numbered around 150,000 by one report, whereas another put the numbers at 100,000 and 130,000 for Ali and Mu'awiya, respectively. As for their Islamic credentials, a considerable number of Muhammad's companions are said to have been present in Ali's army, whereas Mu'awiya could only boast a handful of companions. As for the recruitments, Lecker considers Mua'wiya's "fierce and at times cynical" propaganda more successful than Ali's. Mu'awiya also promised better material benefits to the tribal leaders compared to Ali, who applied strict measures to governors who embezzled money, and this in turn led to their defection to Mu'awiya's side. As such, Lecker describes Mu'awiya's or well-considered opportunism as more successful at Siffin than Ali's piety, and some Arabic sources further contrast Mu'awiya's or opportunism with the Islamic chivalry () of Ali. Shia sources also describe Siffin as a confrontation of Muhammad's cousin and son-in-law with the son of Muhammad's arch-enemy Abu Sufyan, who had led the confederate armies against Muslims in theBattle of the Trench

The Battle of the Trench ( ar, غزوة الخندق, Ghazwat al-Khandaq), also known as the Battle of Khandaq ( ar, معركة الخندق, Ma’rakah al-Khandaq) and the Battle of the Confederates ( ar, غزوة الاحزاب, Ghazwat al- ...

.

Skirmishes

Early in the summer of 657, Ali's army reached Siffin, west of the Euphrates, where Mu'awiya's forces had been waiting for them. The Syrian forces prevented Ail's army from accessing the watering place. A messenger of Ali now told Mu'awiya that they did not wish to fight the Syrians without proper warning, to which Mu'awiya responded by fortifying the forces who were guarding the water. Ali's troops were, however, able to drive off the Syrians and seize control of the watering place, though Ali allowed the enemies to freely access the water. The two sides at Siffin engaged in desultory skirmishes and fruitless negotiations for some three months. This idle period reflects the troops' reluctance for battle, possibly because they were averse to shedding other Muslims' blood, or because most tribes were represented on both sides. Donner adds that neither of the two leaders enjoyed strong support among their armies. At any rate, the negotiations failed on 18 July 657 and the two side readied for the battle. Per Arab customs, prominent figures fought with small retinues prior to the main battle, which took place a week later.Main battle

Historical materials are abundant about the Battle of Siffin, though they mostly describe disconnected episodes of the war. Lecker and Wellhausen have thus found it impossible to establish the course of the battle. Nevertheless, the battle began on Wednesday, 26 July 657, and continued to Friday or Saturday morning. Ali fought with his men on the frontline while Mu'awiya led from his pavilion. At the end of the first day, having pushed back Ali's right-wing, Mu'awiya had fared better overall.

On the second day, Mu'awiya concentrated his assault on Ali's left wing but the tide turned and the Syrians were pushed back. Mu'awiya fled his pavilion and took shelter in an army tent. On this day,

Historical materials are abundant about the Battle of Siffin, though they mostly describe disconnected episodes of the war. Lecker and Wellhausen have thus found it impossible to establish the course of the battle. Nevertheless, the battle began on Wednesday, 26 July 657, and continued to Friday or Saturday morning. Ali fought with his men on the frontline while Mu'awiya led from his pavilion. At the end of the first day, having pushed back Ali's right-wing, Mu'awiya had fared better overall.

On the second day, Mu'awiya concentrated his assault on Ali's left wing but the tide turned and the Syrians were pushed back. Mu'awiya fled his pavilion and took shelter in an army tent. On this day, Ubayd Allah ibn Umar

Ubayd Allah ibn Umar ibn al-Khattab ( ar, عبيد الله بن عمر بن الخطاب, ʿUbayd Allāh ibn ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb; died summer 657) was a son of Caliph Umar (). His killing of Hormuzan, whom he suspected of involvement in h ...

was killed fighting for Mu'awiya. He had fled to Syria earlier when Ali decided to punish him for murdering some Persians who were innocent of Umar's assassination. On the other side, Ammar ibn Yasir

Abū 'l-Yaqẓān ʿAmmār ibn Yāsir ibn ʿĀmir ibn Mālik al-ʿAnsīy al-Maḏḥiǧī ( ar, أبو اليقظان عمار ابن ياسر ابن عامر ابن مالك العنسي المذحجي) also known as Abū 'l-Yaqẓān ʿAmmār i ...

, an octogenarian companion of Muhammad, was killed fighting for Ali. In the canonical Sunni sources ''Sahih al-Bukhari

Sahih al-Bukhari ( ar, صحيح البخاري, translit=Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī), group=note is a ''hadith'' collection and a book of '' sunnah'' compiled by the Persian scholar Muḥammad ibn Ismā‘īl al-Bukhārī (810–870) around 846. A ...

'' and ''Sahih Muslim

Sahih Muslim ( ar, صحيح مسلم, translit=Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim), group=note is a 9th-century '' hadith'' collection and a book of '' sunnah'' compiled by the Persian scholar Muslim ibn al-Ḥajjāj (815–875). It is one of the most valued b ...

'', a prophetic hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approva ...

() predicts Ammar's death at the hands of () who invite to hellfire.

On the third day, Mu'awiya turned down the proposal to settle the matters in a personal duel with Ali, proposed separately by Ali and some of Mu'awiya's followers. Urwa ibn Dawud al-Dimashqi volunteered to fight instead of Mu'awiya and was promptly "cleft in two" by Ali. After another indecisive day, the battle continued throughout (). Unlike Ali, Mu'awiya did not allow the enemy to recover and bury their dead when he advanced.

Call to arbitration

By the next morning, the balance had moved in Ali's favor. Before noon, however, some of the Syrians raised pages of the Quran on their lances, shouting, "Let the Book of God be the judge between us." The fighting stopped at once. By this point, Ali is estimated to have lost 25,000 men, while Mu'awiya is said to have lost 45,000.

By the next morning, the balance had moved in Ali's favor. Before noon, however, some of the Syrians raised pages of the Quran on their lances, shouting, "Let the Book of God be the judge between us." The fighting stopped at once. By this point, Ali is estimated to have lost 25,000 men, while Mu'awiya is said to have lost 45,000.

Syrians' motives

It was consistently Mu'awiya's position that battle was the only option acceptable to the Syrians. The Syrians' call for arbitration thus indicates that Mu'awiya had sensed imminent defeat, argue Madelung and McHugo. This is often the view of contemporary authors, some of whom add that Mu'awiya was advised to do so by Amr ibn al-As.Iraqis' reaction

The Syrians' call to arbitration on the basis of the Quran has thus been interpreted as an offer to surrender. Still, Ali's army stopped fighting possibly because devout Muslims in Ali's army had been fighting to enforce the rule of the Quran all along, or simply because both armies were exhausted and a truce must have appealed to them, or because some in Ali's army saw the ceasefire as an opportunity to regain their influence over Ali. For his part, Ali is said to have exhorted his men to continue fighting, warning them to no avail that raising the Quran was for deception. Nevertheless, the majority of the () and those troops whose support for war was only lukewarm are reported to have insisted on accepting the call to arbitration. In the former group, Mis'ar ibn Fadaki and Zayd ibn Hisn al-Ta'i, both of whom later becameKharijite

The Kharijites (, singular ), also called al-Shurat (), were an Islamic sect which emerged during the First Fitna (656–661). The first Kharijites were supporters of Ali who rebelled against his acceptance of arbitration talks to settle the ...

leaders, threatened to kill Ali if he did not answer the Syrians' call. The latter group included the tribesmen of Kufa and all newcomers from their clans, forming the largest bloc in Ali's army. These followed al-Ash'ath ibn Qays

Abū Muḥammad Maʿdīkarib ibn Qays ibn Maʿdīkarib (), better known as al-Ashʿath (died ca. 661), was a chieftain of the Kinda tribe of Hadhramawt and founder of the one of the leading noble Arab households of Kufa, one of the two main garri ...

, who told Ali that his clan would not fight for him if he refused the Syrians' call, as reported in ''Waq'at Siffin'' and ''Moruj.''

Ali might have thus faced a mutiny and was forced to recall al-Ashtar, who had advanced far towards the Syrian camp. Al-Ashtar initially refused to stop fighting, perhaps sensing imminent victory.

Iraqis' motives

As for al-Ash'ath's motives, Kennedy notes that Ali had earlier supported Hujr ibn Adi, al-Ash'ath's rival within the Kinda tribe. While al-Ash'ath is known to have expressed concern about Iran's insecurity and the Byzantines' threat, Kennedy suggests he also did not want to see Ali's power increased. Jafri similarly suggests that al-Ash'ath and other Kufan tribal leaders benefited from a deadlock between Ali and Mu'awiya: On the one hand, they would have lost their tribal power under a victorious Ali, who likely intended to restore the Islamic leadership in Kufa at the cost of its tribal aristocracy that had emerged under Uthman. On the other hand, Mu'awiya's victory would have meant the subjugation and loss of Iraq as the base of their power. As such, they reluctantly participated in Siffin and readily accepted the later arbitration offers. Hinds has a similar view, while Shaban writes that the Kufan tribes had benefited from Uthman's policies and were not enthusiastic about the war with Mu'awiya. Jafri adds that the Kufan tribal leaders probably resented Ali's egalitarian policies, as he divided the treasury funds equally among Arabs and non-Arabs, and among late- and new-comers to Kufa.Arbitration agreement

Mu'awiya then conveyed his proposal that representatives from both sides should together reach a binding solution on the basis of the Quran. Crucially, he was silent at this point on Uthman's revenge and a for a new caliph. Mu'awiya's proposal was accepted by the majority of Ali's army, reports

Mu'awiya then conveyed his proposal that representatives from both sides should together reach a binding solution on the basis of the Quran. Crucially, he was silent at this point on Uthman's revenge and a for a new caliph. Mu'awiya's proposal was accepted by the majority of Ali's army, reports al-Tabari

( ar, أبو جعفر محمد بن جرير بن يزيد الطبري), more commonly known as al-Ṭabarī (), was a Muslim historian and scholar from Amol, Tabaristan. Among the most prominent figures of the Islamic Golden Age, al-Tabari ...

(). Soon, however, a sizeable minority in Ali's army objected to the arbitration, possibly realizing the political motivations of Mu'awiya. This minority wanted Ali to resume the fighting. While Ali is reported to have favored their proposal, he declined it, saying that they would be crushed by the majority and the Syrians who all demanded arbitration. Some of these dissidents left for Kufa, while others stayed, perhaps hoping that Ali might later change his mind. Facing strong peace sentiments in his army, Ali thus accepted the arbitration proposal, most likely against his own judgment.

Selection of the arbitrators

The majority in Ali's army now pressed for the reportedly neutralAbu Musa al-Ashari

Abu Musa Abd Allah ibn Qays al-Ash'ari ( ar, أبو موسى عبد الله بن قيس الأشعري, Abū Mūsā ʿAbd Allāh ibn Qays al-Ashʿarī), better known as Abu Musa al-Ash'ari ( ar, أبو موسى الأشعري, Abū Mūsā al-Ash ...

as their representative, despite Ali's concerns about Abu Musa's political naivety or neutrality. Abu Musa was the former governor of Kufa, installed by the Iraqi rebels and later (reluctantly) confirmed by Ali, though he was soon dismissed after hampering Ali's preparations for the Battle of the Camel. Veccia Vaglieri and Rahman write that the Iraqis were so convinced of the legitimacy of their cause that they insisted on the neutral Abu Musa, whereas others suggest that they were impressed by his piety and his beautiful recitations of the Quran or that he stood for provincial autonomy in Kufans' view.

The arbitration agreement was written and signed by both parties on 2 August 657. Abu Musa represented Ali's army while Mu'awiya's top general Amr ibn al-As represented Mu'awiya's forces. The latter was far from neutral and acted solely for the benefit of Mu'awiya. The two representatives committed to meet on neutral territory, to adhere to the Quran and Sunna and save the community from war and division, a clause added evidently to appease the peace party. Two days after this agreement the two armies left the battlefield.

Seceders

As Ali returned to Kufa, some of his men seceded and gathered outside of Kufa in protest of the arbitration agreement. Ali visited them and reminded them that they had opted for the arbitration despite his warnings. They agreed and told Ali that they had repented for their sins and demanded that Ali do the same. Ali is reported to have responded with the general declaration, "I repent to God and ask for his forgiveness for every sin." Ali also ensured them that the judgment of the arbitrators would not be binding if they deviated from the Quran and Sunna. He thus largely regained their support. When the seceders returned to Kufa, however, they claimed that Ali had nullified the arbitration agreement, which Ali denied, reiterating that he observed the formal agreement with Mu'awiya. Many of the dissidents are said to have accepted Ali's position while the rest formed theKharijites

The Kharijites (, singular ), also called al-Shurat (), were an Islamic sect which emerged during the First Fitna (656–661). The first Kharijites were supporters of Ali who rebelled against his acceptance of arbitration talks to settle the ...

(), who later took up arms against Ali in the Battle of Nahrawan

The Battle of Nahrawan ( ar, معركة النهروان, Ma'rakat an-Nahrawān) was fought between the army of Caliph Ali and the rebel group Kharijites in July 658 CE (Safar 38 AH). They used to be a group of pious allies of Ali during the ...

. They soon labeled Ali and his followers as nonbelievers who had to be fought, thus becoming the forerunners of Islamic extremism

Islamic extremism, Islamist extremism, or radical Islam, is used in reference to extremist beliefs and behaviors which are associated with the Islamic religion. These are controversial terms with varying definitions, ranging from academic un ...

.

Motives

Donner suggests that the seceders, among them many of the , may have feared being held accountable for their role in Uthman's murder, while Hinds and Poonawala hold that the seceders were disillusioned with the arbitration process, particularly by the removal of Ali's title in the final agreement and by its reference to Sunna in addition to the Quran, as noted also in ''Waq'at Sifin''. After being silent about it initially, the Syrians now revealed that they also wanted the arbitrators to judge whether the killing of Uthman was justified, about which the had no doubts. As such, Hinds and Poonawala regard the arbitration as a skilfully planned manoeuvre to disintegrate Ali's coalition.Slogan

The seceders adopted the slogan, "No judgment but that of God," highlighting their rejection of the arbitration (by men) possibly based on verse 49:9, "If two parties of the Believers fight with one another, make peace between them; but if one rebels against the other, then fight against the one that rebels, until they return to obedience to God." When they interrupted Ali's sermon with this slogan, he commented that it was a word of truth by which the seceders sought falsehood. He added that they were repudiating government while a ruler was indispensable in the conduct of religion. Ali nevertheless did not bar their entry to mosques or deprive them of their shares in the treasury, saying that they should be fought only if they initiate the hostilities.

The seceders adopted the slogan, "No judgment but that of God," highlighting their rejection of the arbitration (by men) possibly based on verse 49:9, "If two parties of the Believers fight with one another, make peace between them; but if one rebels against the other, then fight against the one that rebels, until they return to obedience to God." When they interrupted Ali's sermon with this slogan, he commented that it was a word of truth by which the seceders sought falsehood. He added that they were repudiating government while a ruler was indispensable in the conduct of religion. Ali nevertheless did not bar their entry to mosques or deprive them of their shares in the treasury, saying that they should be fought only if they initiate the hostilities.

Arbitration

After several months of preparation, the two arbitrators met together, first at Dumat al-Jandal and then atUdhruh

Udhruh ( ar, اذرح; transliteration: ''Udhruḥ'', Ancient Greek ''Adrou'', Άδρου), also spelled Adhruh, is a town in southern Jordan, administratively part of the Ma'an Governorate. It is located east of Petra.MacDonald 2015, p. 59. It ...

. This is the understanding of Madelung, Veccia Vaglieri, and Caetani, though some other historians have insisted that the two met only once.

First meeting

At Dumat al-Jandal, the proceedings lasted for (possibly three) weeks, likely extending to mid-April 658. There, the arbitrators reached the verdict that Uthman had been killed wrongfully and that Mu'awiya had the right to seek revenge. Madelung views this as a political verdict, a judicial misjudgment, and a blunder of the naive Abu Musa, who might have hoped that Amr would later reciprocate his concession. The verdict was not made public though both parties learned about it anyway. Ali then denounced the conduct of the two arbitrators as contrary to the Quran and began organizing a new expedition to Syria.Second meeting

Evidently not endorsed by Ali, the second meeting was convened atUdhruh

Udhruh ( ar, اذرح; transliteration: ''Udhruḥ'', Ancient Greek ''Adrou'', Άδρου), also spelled Adhruh, is a town in southern Jordan, administratively part of the Ma'an Governorate. It is located east of Petra.MacDonald 2015, p. 59. It ...

in January 659, possibly to discuss the next caliph. Not part of the arbitration, this second meeting was solely an initiative of Mu'awiya, and it broke up in disarray as the two arbitrators could not agree on the next caliph: Amr supported Mu'awiya while Abu Musa nominated his son-in-law Abd Allah ibn Umar, who stood down reportedly in the interest of unity. After this meeting, one account is that Abu Musa deposed both Ali and Mu'awiya and called for a council to appoint the new caliph per his earlier agreement with Amr. When Amr took the stage, however, he deposed Ali but confirmed Mu'awiya as the new caliph, thus violating his agreement with Abu Musa. The Kufan delegation reacted furiously to Abu Musa's concessions. He was disgraced and fled to Mecca, whereas Amr was received triumphantly by Mu'awiya on his return to Syria. The arbitration thus failed or was inconclusive. This is summed up by an early source in one sentence, "The arbiters agreed on nothing." The arbitration nevertheless strengthened the Syrians' support for Mu'awiya and weakened the position of Ali.

Aftermath

After the conclusion of the arbitration, Syrians pledged their allegiance to Mu'awiya as the next caliph in 659. Upon learning that Mu'awiya had declared himself caliph, Ali broke off all communications with him and introduced a curse on him, following the precedent of Muhammad. Mu'awiya reciprocated by introducing a curse on Ali, his sons, and his top general. With the news of their violence against civilians, Ali had to postpone his new Syria campaign to subdue the Kharijites in the Battle of Nahrawan in 658. Just before embarking on his second campaign to Syria in 661, Ali was assassinated by a Kharijite during the morning prayers at the Mosque of Kufa.References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Siffin Battles involving the Rashidun Caliphate Battles involving the Umayyad Caliphate First Fitna Shia days of remembrance 650s conflicts 657