adjunct (grammar) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

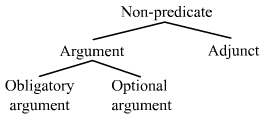

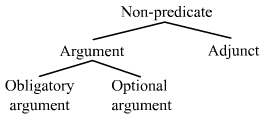

This overview acknowledges three types of entities: predicates, arguments, and adjuncts, whereby arguments are further divided into obligatory and optional ones.

This overview acknowledges three types of entities: predicates, arguments, and adjuncts, whereby arguments are further divided into obligatory and optional ones.

The object argument each time is identified insofar as it is a sister of V that appears to the right of V, and the adjunct status of the adverb ''early'' and the PP ''before class'' is seen in the higher position to the right of and above the object argument. Other adjuncts, in contrast, are assumed to adjoin to a position that is between the subject argument and the head predicate or above and to the left of the subject argument, e.g.

::

The object argument each time is identified insofar as it is a sister of V that appears to the right of V, and the adjunct status of the adverb ''early'' and the PP ''before class'' is seen in the higher position to the right of and above the object argument. Other adjuncts, in contrast, are assumed to adjoin to a position that is between the subject argument and the head predicate or above and to the left of the subject argument, e.g.

:: The subject is identified as an argument insofar as it appears as a sister and to the left of V(P). The modal adverb ''certainly'' is shown as an adjunct insofar as it adjoins to an intermediate projection of V or to a projection of S.

In X-bar theory, adjuncts are represented as elements that are sisters to X' levels and daughters of X' level ' adjunct [X'....

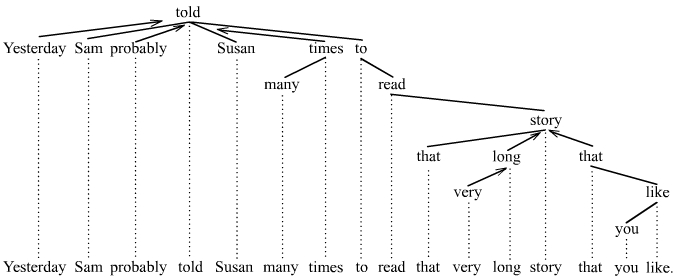

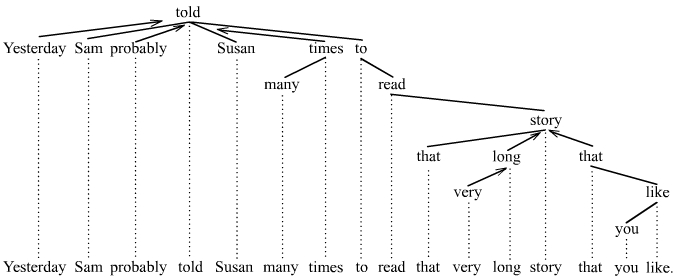

Theories that assume sentence structure to be less layered than the analyses just given sometimes employ a special convention to distinguish adjuncts from arguments. Some dependency grammars, for instance, use an arrow dependency edge to mark adjuncts,For an example of the arrow used to mark adjuncts, see for instance Eroms (2000). e.g.

::

The subject is identified as an argument insofar as it appears as a sister and to the left of V(P). The modal adverb ''certainly'' is shown as an adjunct insofar as it adjoins to an intermediate projection of V or to a projection of S.

In X-bar theory, adjuncts are represented as elements that are sisters to X' levels and daughters of X' level ' adjunct [X'....

Theories that assume sentence structure to be less layered than the analyses just given sometimes employ a special convention to distinguish adjuncts from arguments. Some dependency grammars, for instance, use an arrow dependency edge to mark adjuncts,For an example of the arrow used to mark adjuncts, see for instance Eroms (2000). e.g.

:: The arrow dependency edge points away from the adjunct toward the governor of the adjunct. The arrows identify six adjuncts: ''Yesterday'', ''probably'', ''many times'', ''very'', ''very long'', and ''that you like''. The standard, non-arrow dependency edges identify ''Sam'', ''Susan'', ''that very long story that you like'', etc. as arguments (of one of the predicates in the sentence).

The arrow dependency edge points away from the adjunct toward the governor of the adjunct. The arrows identify six adjuncts: ''Yesterday'', ''probably'', ''many times'', ''very'', ''very long'', and ''that you like''. The standard, non-arrow dependency edges identify ''Sam'', ''Susan'', ''that very long story that you like'', etc. as arguments (of one of the predicates in the sentence).

linguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Linguis ...

, an adjunct is an optional, or ''structurally dispensable'', part of a sentence, clause, or phrase that, if removed or discarded, will not structurally affect the remainder of the sentence. Example: In the sentence ''John helped Bill in Central Park

Central Park is an urban park in New York City located between the Upper West Side, Upper West and Upper East Sides of Manhattan. It is the List of New York City parks, fifth-largest park in the city, covering . It is the most visited urban par ...

'', the phrase ''in Central Park'' is an adjunct.See Lyons (1968).

A more detailed definition of the adjunct emphasizes its attribute as a modifying form, word, or phrase that depends on another form, word, or phrase, being an element of clause structure with adverbial

In English grammar, an adverbial (abbreviated ) is a word (an adverb) or a group of words (an adverbial clause or adverbial phrase) that modifies or more closely defines the sentence or the verb. (The word ''adverbial'' itself is also used as a ...

function. An adjunct is not an argument

An argument is a statement or group of statements called premises intended to determine the degree of truth or acceptability of another statement called conclusion. Arguments can be studied from three main perspectives: the logical, the dialectic ...

(nor is it a predicative expression

A predicative expression (or just predicative) is part of a clause predicate, and is an expression that typically follows a copula (or linking verb), e.g. ''be'', ''seem'', ''appear'', or that appears as a second complement of a certain type of v ...

), and an argument is not an adjunct. The argument–adjunct distinction is central in most theories of syntax and semantics. The terminology used to denote arguments and adjuncts can vary depending on the theory at hand. Some dependency grammars, for instance, employ the term ''circonstant'' (instead of ''adjunct''), following Tesnière (1959).

The area of grammar that explores the nature of predicate

Predicate or predication may refer to:

* Predicate (grammar), in linguistics

* Predication (philosophy)

* several closely related uses in mathematics and formal logic:

**Predicate (mathematical logic)

**Propositional function

**Finitary relation, o ...

s, their arguments, and adjuncts is called valency theory. Predicates have valency; they determine the number and type of arguments that can or must appear in their environment. The valency of predicates is also investigated in terms of subcategorization

In linguistics, subcategorization denotes the ability/necessity for lexical items (usually verbs) to require/allow the presence and types of the syntactic arguments with which they co-occur. The notion of subcategorization is similar to the notio ...

.

Examples

Take the sentence ''John helped Bill in Central Park on Sunday'' as an example: :# ''John'' is the subject argument. :# ''helped'' is the predicate. :# ''Bill'' is the object argument. :# ''in Central Park'' is the first adjunct. :# ''on Sunday'' is the second adjunct. An ''adverbial adjunct'' is a sentence element that often establishes the circumstances in which the action or state expressed by theverb

A verb () is a word (part of speech) that in syntax generally conveys an action (''bring'', ''read'', ''walk'', ''run'', ''learn''), an occurrence (''happen'', ''become''), or a state of being (''be'', ''exist'', ''stand''). In the usual descri ...

takes place. The following sentence uses adjuncts of time and place:

::Yesterday, Lorna saw the dog in the garden.

Notice that this example is ambiguous between whether the adjunct ''in the garden'' modifies the verb ''saw'' (in which case it is Lorna who saw the dog while she was in the garden) or the noun phrase ''the dog'' (in which case it is the dog who is in the garden). The definition can be extended to include adjuncts that modify noun

A noun () is a word that generally functions as the name of a specific object or set of objects, such as living creatures, places, actions, qualities, states of existence, or ideas.Example nouns for:

* Living creatures (including people, alive, d ...

s or other parts of speech (see noun adjunct

In grammar, a noun adjunct, attributive noun, qualifying noun, noun (pre)modifier, or apposite noun is an optional noun that modifies another noun; functioning similarly to an adjective, it is, more specifically, a noun functioning as a pre-modif ...

).

Forms and domains

An adjunct can be a single word, aphrase

In syntax and grammar, a phrase is a group of words or singular word acting as a grammatical unit. For instance, the English expression "the very happy squirrel" is a noun phrase which contains the adjective phrase "very happy". Phrases can consi ...

, or an entire clause.

::Single word

::She will leave tomorrow.

::Phrase

::She will leave in the morning.

::Clause

::She will leave after she has had breakfast.

Most discussions of adjuncts focus on adverbial adjuncts, that is, on adjuncts that modify verbs, verb phrases, or entire clauses like the adjuncts in the three examples just given. Adjuncts can appear in other domains, however; that is, they can modify most categories. An adnominal adjunct is one that modifies a noun: for a list of possible types of these, see Components of noun phrases. Adjuncts that modify adjectives and adverbs are occasionally called ''adadjectival'' and ''adadverbial''.

::the discussion before the game – ''before the game'' is an adnominal adjunct.

::very happy – ''very'' is an "adadjectival" adjunct.

::too loudly – ''too'' is an "adadverbial" adjunct.

Adjuncts are always constituents. Each of the adjuncts in the examples throughout this article is a constituent.

Semantic function

Adjuncts can be categorized in terms of the functional meaning that they contribute to the phrase, clause, or sentence in which they appear. The following list of the semantic functions is by no means exhaustive, but it does include most of the semantic functions of adjuncts identified in the literature on adjuncts: ::Causal – Causal adjuncts establish the reason for, or purpose of, an action or state. ::The ladder collapsed because it was old. (reason) ::Concessive – Concessive adjuncts establish contrary circumstances. ::Lorna went out although it was raining. ::Conditional – Conditional adjuncts establish the condition in which an action occurs or state holds. ::I would go to Paris, if I had the money. ::Consecutive – Consecutive adjuncts establish an effect or result. ::It rained so hard that the streets flooded. ::Final – Final adjuncts establish the goal of an action (what one wants to accomplish). ::He works a lot to earn money for school. ::Instrumental – Instrumental adjuncts establish the instrument used to accomplish an action. ::Mr. Bibby wrote the letter with a pencil. ::Locative – Locative adjuncts establish where, to where, or from where a state or action happened or existed. ::She sat on the table. (locative) ::Measure – Measure adjuncts establish the measure of the action, state, or quality that they modify ::I am completely finished. ::That is mostly true. ::We want to stay in part. ::Modal – Modal adjuncts establish the extent to which the speaker views the action or state as (im)probable. ::They probably left. ::In any case, we didn't do it. ::That is perhaps possible. ::I'm definitely going to the party. ::Modificative – Modificative adjuncts establish how the action happened or the state existed. ::He ran with difficulty. (manner) ::He stood in silence. (state) ::He helped me with my homework. (limiting) ::Temporal – Temporal adjuncts establish when, how long, or how frequent the action or state happened or existed. ::He arrived yesterday. (time point) ::He stayed for two weeks. (duration) ::She drinks in that bar every day. (frequency)Distinguishing between predicative expressions, arguments, and adjuncts

Omission diagnostic

The distinction between arguments and adjuncts andpredicates

Predicate or predication may refer to:

* Predicate (grammar), in linguistics

* Predication (philosophy)

* several closely related uses in mathematics and formal logic:

**Predicate (mathematical logic)

**Propositional function

**Finitary relation, ...

is central to most theories of syntax and grammar. Predicates

Predicate or predication may refer to:

* Predicate (grammar), in linguistics

* Predication (philosophy)

* several closely related uses in mathematics and formal logic:

**Predicate (mathematical logic)

**Propositional function

**Finitary relation, ...

take arguments and they permit (certain) adjuncts. The arguments of a predicate are necessary to complete the meaning of the predicate. The adjuncts of a predicate, in contrast, provide auxiliary information about the core predicate-argument meaning, which means they are not necessary to complete the meaning of the predicate. Adjuncts and arguments can be identified using various diagnostics. The omission diagnostic, for instance, helps identify many arguments and thus indirectly many adjuncts as well. If a given constituent cannot be omitted from a sentence, clause, or phrase without resulting in an unacceptable expression, that constituent is NOT an adjunct, e.g.

::a. Fred certainly knows.

::b. Fred knows. – ''certainly'' may be an adjunct (and it is).

::a. He stayed after class.

::b. He stayed. – ''after class'' may be an adjunct (and it is).

::a. She trimmed the bushes.

::b. *She trimmed. – ''the bushes'' is NOT an adjunct.

::a. Jim stopped.

::b. *Stopped. – ''Jim'' is NOT an adjunct.

Other diagnostics

Further diagnostics used to distinguish between arguments and adjuncts include multiplicity, distance from head, and the ability to coordinate. A head can have multiple adjuncts but only one object argument (=complement): ::a. Bob ate the pizza. – ''the pizza'' is an object argument (=complement). ::b. Bob ate the pizza and the hamburger. ''the pizza and the hamburger'' is a noun phrase that functions as object argument. ::c. Bob ate the pizza with a fork. – ''with a fork'' is an adjunct. ::d. Bob ate the pizza with a fork on Tuesday. – ''with a fork'' and ''on Tuesday'' are both adjuncts. Object arguments are typically closer to their head than adjuncts: ::a. the collection of figurines (complement) in the dining room (adjunct) ::b. *the collection in the dining room (adjunct) of figurines (complement) Adjuncts can be coordinated with other adjuncts, but not with arguments: ::a. *Bob ate the pizza and with a fork. ::b. Bob ate with a fork and with a spoon.Optional arguments vs. adjuncts

The distinction between arguments and adjuncts is much less clear than the simple omission diagnostic (and the other diagnostics) suggests. Most accounts of the argument vs. adjunct distinction acknowledge a further division. One distinguishes between obligatory and optional arguments. Optional arguments pattern like adjuncts when just the omission diagnostic is employed, e.g. ::a. Fred ate a hamburger. ::b. Fred ate. – ''a hamburger'' is NOT an obligatory argument, but it could be (and it is) an optional argument. ::a. Sam helped us. ::b. Sam helped – ''us'' is NOT an obligatory argument, but it could be (and it is) an optional argument. The existence of optional arguments blurs the line between arguments and adjuncts considerably. Further diagnostics (beyond the omission diagnostic and the others mentioned above) must be employed to distinguish between adjuncts and optional arguments. One such diagnostic is the relative clause test. The test constituent is moved from the matrix clause to a subordinate relative clause containing ''which occurred/happened''. If the result is unacceptable, the test constituent is probably NOT an adjunct: ::a. Fred ate a hamburger. ::b. Fred ate. – ''a hamburger'' is not an obligatory argument. ::c. *Fred ate, which occurred a hamburger. – ''a hamburger'' is not an adjunct, which means it must be an optional argument. ::a. Sam helped us. ::b. Sam helped. – ''us'' is not an obligatory argument. ::c. *Sam helped, which occurred us. – ''us'' is not an adjunct, which means it must be an optional argument. The particular merit of the relative clause test is its ability to distinguish between many argument and adjunct PPs, e.g. ::a. We are working on the problem. ::b. We are working. ::c. *We are working, which is occurring on the problem. – ''on the problem'' is an optional argument. ::a. They spoke to the class. ::b. They spoke. ::c. *They spoke, which occurred to the class. – ''to the class'' is an optional argument. The reliability of the relative clause diagnostic is actually limited. For instance, it incorrectly suggests that many modal and manner adjuncts are arguments. This fact bears witness to the difficulty of providing an absolute diagnostic for the distinctions currently being examined. Despite the difficulties, most theories of syntax and grammar distinguish on the one hand between arguments and adjuncts and on the other hand between optional arguments and adjuncts, and they grant a central position to these divisions in the overarching theory.Predicates vs. adjuncts

Many phrases have the outward appearance of an adjunct but are in fact (part of) a predicate instead. The confusion occurs often with copular verbs, in particular with a form of ''be'', e.g. ::It is under the bush. ::The party is at seven o'clock. The PPs in these sentences are NOT adjuncts, nor are they arguments. The preposition in each case is, rather, part of the main predicate. The matrix predicate in the first sentence is ''is under''; this predicate takes the two arguments ''It'' and ''the bush''. Similarly, the matrix predicate in the second sentence is ''is at''; this predicate takes the two arguments ''The party'' and ''seven o'clock''. Distinguishing between predicates, arguments, and adjuncts becomes particularly difficult when secondary predicates are involved, for instance with resultative predicates, e.g. ::That made him tired. The resultative adjective ''tired'' can be viewed as an argument of the matrix predicate ''made''. But it is also definitely a predicate over ''him''. Such examples illustrate that distinguishing predicates, arguments, and adjuncts can become difficult and there are many cases where a given expression functions in more ways than one.Overview

The following overview is a breakdown of the current divisions: :: This overview acknowledges three types of entities: predicates, arguments, and adjuncts, whereby arguments are further divided into obligatory and optional ones.

This overview acknowledges three types of entities: predicates, arguments, and adjuncts, whereby arguments are further divided into obligatory and optional ones.

Representing adjuncts

Many theories of syntax and grammar employ trees to represent the structure of sentences. Various conventions are used to distinguish between arguments and adjuncts in these trees. Inphrase structure grammar

The term phrase structure grammar was originally introduced by Noam Chomsky as the term for grammar studied previously by Emil Post and Axel Thue (Post canonical systems). Some authors, however, reserve the term for more restricted grammars in th ...

s, many adjuncts are distinguished from arguments insofar as the adjuncts of a head predicate will appear higher in the structure than the object argument(s) of that predicate. The adjunct is adjoined to a projection of the head predicate above and to the right of the object argument, e.g.

:: The object argument each time is identified insofar as it is a sister of V that appears to the right of V, and the adjunct status of the adverb ''early'' and the PP ''before class'' is seen in the higher position to the right of and above the object argument. Other adjuncts, in contrast, are assumed to adjoin to a position that is between the subject argument and the head predicate or above and to the left of the subject argument, e.g.

::

The object argument each time is identified insofar as it is a sister of V that appears to the right of V, and the adjunct status of the adverb ''early'' and the PP ''before class'' is seen in the higher position to the right of and above the object argument. Other adjuncts, in contrast, are assumed to adjoin to a position that is between the subject argument and the head predicate or above and to the left of the subject argument, e.g.

:: The subject is identified as an argument insofar as it appears as a sister and to the left of V(P). The modal adverb ''certainly'' is shown as an adjunct insofar as it adjoins to an intermediate projection of V or to a projection of S.

In X-bar theory, adjuncts are represented as elements that are sisters to X' levels and daughters of X' level ' adjunct [X'....

Theories that assume sentence structure to be less layered than the analyses just given sometimes employ a special convention to distinguish adjuncts from arguments. Some dependency grammars, for instance, use an arrow dependency edge to mark adjuncts,For an example of the arrow used to mark adjuncts, see for instance Eroms (2000). e.g.

::

The subject is identified as an argument insofar as it appears as a sister and to the left of V(P). The modal adverb ''certainly'' is shown as an adjunct insofar as it adjoins to an intermediate projection of V or to a projection of S.

In X-bar theory, adjuncts are represented as elements that are sisters to X' levels and daughters of X' level ' adjunct [X'....

Theories that assume sentence structure to be less layered than the analyses just given sometimes employ a special convention to distinguish adjuncts from arguments. Some dependency grammars, for instance, use an arrow dependency edge to mark adjuncts,For an example of the arrow used to mark adjuncts, see for instance Eroms (2000). e.g.

:: The arrow dependency edge points away from the adjunct toward the governor of the adjunct. The arrows identify six adjuncts: ''Yesterday'', ''probably'', ''many times'', ''very'', ''very long'', and ''that you like''. The standard, non-arrow dependency edges identify ''Sam'', ''Susan'', ''that very long story that you like'', etc. as arguments (of one of the predicates in the sentence).

The arrow dependency edge points away from the adjunct toward the governor of the adjunct. The arrows identify six adjuncts: ''Yesterday'', ''probably'', ''many times'', ''very'', ''very long'', and ''that you like''. The standard, non-arrow dependency edges identify ''Sam'', ''Susan'', ''that very long story that you like'', etc. as arguments (of one of the predicates in the sentence).

See also

*Adverbial *Argument (linguistics), Argument *Conjunct *Disjunct (linguistics), Disjunct *Noun adjunct *Predicate (grammar), Predicate *Predicative expression *AttributiveNotes

References

{{refbegin, 2 *Eroms, H.-W. 2000. Syntax der deutschen Sprache. Berlin: de Gruyter. *Carnie, A. 2010. ''Constituent Structure.'' Oxford: Oxford U.P. *Lyons J. 1968. Introduction to theoretical linguistics. London: Cambridge U.P. *Payne, T. 2006. Exploring language structure: A student's guide. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. *Tesnière, L. 1959. Éleménts de syntaxe structurale. Paris: Klincksieck. Syntactic entities es:Complemento circunstancial