Wendell Phillips on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

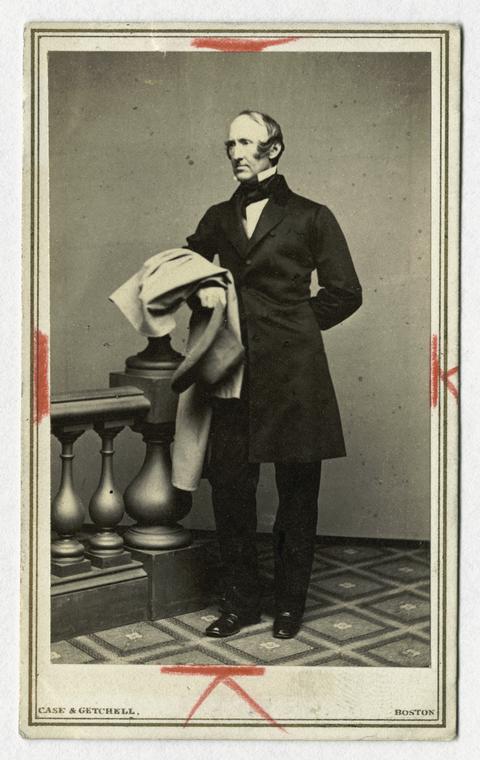

Wendell Phillips (November 29, 1811 – February 2, 1884) was an American abolitionist, advocate for Native Americans, orator, and

''Reading ATimes,'' February 4, 1884, p. 1. He was a descendant of Reverend George Phillips, who emigrated from England to Watertown, Massachusetts, in 1630. All of his ancestors migrated to

On October 21, 1835, the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society announced that British abolitionist George Thompson would be speaking. Pro-slavery forces posted nearly 500 notices of a $100 reward for the citizen that would first lay violent hands on him. Thompson canceled at the last minute, and

On October 21, 1835, the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society announced that British abolitionist George Thompson would be speaking. Pro-slavery forces posted nearly 500 notices of a $100 reward for the citizen that would first lay violent hands on him. Thompson canceled at the last minute, and  It was Phillips's contention that racial injustice was the source of all of society's ills. Like Garrison, Phillips denounced the Constitution for tolerating slavery. He disagreed with abolitionist Lysander Spooner and maintained that slavery was part of the Constitution, and more generally disputed Spooner's notion that any judge could find slavery illegal.

In 1845, in an essay titled "No Union With Slaveholders", he argued that the country would be better off, and not complicit in their guilt, if it let the slave states secede:

It was Phillips's contention that racial injustice was the source of all of society's ills. Like Garrison, Phillips denounced the Constitution for tolerating slavery. He disagreed with abolitionist Lysander Spooner and maintained that slavery was part of the Constitution, and more generally disputed Spooner's notion that any judge could find slavery illegal.

In 1845, in an essay titled "No Union With Slaveholders", he argued that the country would be better off, and not complicit in their guilt, if it let the slave states secede:

On December 8, 1837, in Boston's Faneuil Hall, Phillips' leadership and oratory established his preeminence within the abolitionist movement. Bostonians gathered at Faneuil Hall to discuss

On December 8, 1837, in Boston's Faneuil Hall, Phillips' leadership and oratory established his preeminence within the abolitionist movement. Bostonians gathered at Faneuil Hall to discuss

In the mid-1862, Phillips's nephew, Samuel D. Phillips, died at Port Royal, South Carolina, where he had gone to take part in the so-called Port Royal Experiment to assist the slave population there in the transition to freedom.

In the mid-1862, Phillips's nephew, Samuel D. Phillips, died at Port Royal, South Carolina, where he had gone to take part in the so-called Port Royal Experiment to assist the slave population there in the transition to freedom.

In 1904, the Chicago Public Schools opened

In 1904, the Chicago Public Schools opened

"Wendell Phillips: Orator and Abolitionist,"

''Pearson's Magazine,'' vol. 37, no. 5 (May 1917), pp. 397–402. * Filler, Louis (ed.), "Wendell Phillips on Civil Rights and Freedom," New York: Hill and Wang, 1965. * Hofstadter, Richard. "Wendell Phillips: The Patrician as Agitator" in ''The American Political Tradition: And the Men Who Made It.'' New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1948. * Osofsky, Gilbert. "Wendell Phillips and the Quest for a New American National Identity" ''Canadian Review of Studies in Nationalism,'' vol. 1, no. 1 (1973), pp. 15–46. * Stewart, James Brewer. ''Wendell Phillips: Liberty's Hero.'' LSU Press, 1986. 356 pp. * Stewart, James B. "Heroes, Villains, Liberty, and License: The Abolitionist Vision of Wendell Phillips" in ''Antislavery Reconsidered: New Perspectives on the Abolitionists'' Baton Rouge, LA: LSU Press, 1979; pp. 168–191.

'Toussaint L'Ouverture' A lecture by Wendell Phillips (1861)

The Liberator Files

Items concerning Wendell Phillips from Horace Seldon's collection and summary of research of William Lloyd Garrison's ''The Liberator'' original copies at the Boston Public Library, Boston, Massachusetts.

Letters, 1855, n.d..Schlesinger Library

Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University. * The story of ''The Liberator'' is retold in the 1950 radio drama

The Liberators (Part I)

, a presentation from '' Destination Freedom'', written by Richard Durham {{DEFAULTSORT:Phillips, Wendell 1811 births 1884 deaths Abolitionists from Boston Boston Latin School alumni Harvard Law School alumni Harvard College alumni Lawyers from Boston American male feminists American feminists Activists for Native American rights People of Massachusetts in the American Civil War Phillips family (New England) American temperance activists Burials at Granary Burying Ground American lecturers

attorney

Attorney may refer to:

* Lawyer

** Attorney at law, in some jurisdictions

* Attorney, one who has power of attorney

* ''The Attorney'', a 2013 South Korean film

See also

* Attorney general, the principal legal officer of (or advisor to) a gove ...

.

According to George Lewis Ruffin

George Lewis Ruffin (December 16, 1834 – November 19, 1886) was a barber, attorney, politician and judge. In 1869 he graduated from Harvard Law School, the first African American to do so. He was also the first African American elected to the ...

, a Black attorney, Phillips was seen by many Blacks as "the one white American wholly color-blind and free from race prejudice". According to another Black attorney, Archibald Grimké, as an abolitionist leader he is ahead of William Lloyd Garrison and Charles Sumner. From 1850 to 1865 he was the "preeminent figure" in American abolitionism.

Early life and education

Phillips was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on November 29, 1811, to Sarah Walley and John Phillips, a wealthy lawyer, politician, and philanthropist, who was the first mayor of Boston."A Famous Career,"''Reading ATimes,'' February 4, 1884, p. 1. He was a descendant of Reverend George Phillips, who emigrated from England to Watertown, Massachusetts, in 1630. All of his ancestors migrated to

North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

from England, and all of them arrived in Massachusetts between the years 1630 and 1650.

Phillips was schooled at Boston Latin School

The Boston Latin School is a public exam school in Boston, Massachusetts. It was established on April 23, 1635, making it both the oldest public school in the British America and the oldest existing school in the United States. Its curriculum f ...

, and graduated from Harvard College in 1831. He went on to attend Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (Harvard Law or HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest continuously operating law school in the United States.

Each class ...

, from which he graduated in 1833. In 1834, Phillips was admitted to the Massachusetts state bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar (u ...

, and in the same year, he opened a law practice in Boston.

Marriage to Ann Terry Greene

In 1836, Phillips was supporting the abolitionist cause when he met Ann Greene. It was her opinion that this cause required not just support but total commitment. Phillips and Greene were engaged that year and Greene declared Wendell to be her "best three quarters". They were married until Wendell's death, 46 years later.Abolitionism

On October 21, 1835, the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society announced that British abolitionist George Thompson would be speaking. Pro-slavery forces posted nearly 500 notices of a $100 reward for the citizen that would first lay violent hands on him. Thompson canceled at the last minute, and

On October 21, 1835, the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society announced that British abolitionist George Thompson would be speaking. Pro-slavery forces posted nearly 500 notices of a $100 reward for the citizen that would first lay violent hands on him. Thompson canceled at the last minute, and Wm. Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he foun ...

, editor and publisher of the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator

Liberator or The Liberators or ''variation'', may refer to:

Literature

* ''Liberators'' (novel), a 2009 novel by James Wesley Rawles

* ''The Liberators'' (Suvorov book), a 1981 book by Victor Suvorov

* ''The Liberators'' (comic book), a Britis ...

, was quickly scheduled to speak in his place. A lynch mob

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

formed, forcing Garrison to escape through the back of the hall and hide in a carpenter's shop. The mob soon found him, putting a noose around his neck to drag him away. Several strong men, including the mayor, intervened and took him to the most secure place in Boston, the Leverett Street Jail. Phillips, watching from nearby Court Street, was a witness to the attempted lynching.

After being converted to the abolitionist cause by Garrison in 1836, Phillips stopped practicing law in order to dedicate himself to the movement. Phillips joined the American Anti-Slavery Society

The American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS; 1833–1870) was an abolitionist society founded by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan. Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave, had become a prominent abolitionist and was a key leader of this society ...

and frequently made speeches at its meetings. So highly regarded were Phillips' oratorical abilities that he was known as "abolition's golden trumpet". Like many of Phillips' fellow abolitionists who honored the free-produce movement

The free-produce movement was an international boycott of goods produced by slave labor. It was used by the abolitionist movement as a non-violent way for individuals, including the disenfranchised, to fight slavery.

In this context, ''free'' sig ...

, he condemned the purchase of cane sugar and clothing made of cotton, since both were produced by the labor of slaves. He was a member of the Boston Vigilance Committee, an organization that assisted fugitive slaves in avoiding slavecatchers.

It was Phillips's contention that racial injustice was the source of all of society's ills. Like Garrison, Phillips denounced the Constitution for tolerating slavery. He disagreed with abolitionist Lysander Spooner and maintained that slavery was part of the Constitution, and more generally disputed Spooner's notion that any judge could find slavery illegal.

In 1845, in an essay titled "No Union With Slaveholders", he argued that the country would be better off, and not complicit in their guilt, if it let the slave states secede:

It was Phillips's contention that racial injustice was the source of all of society's ills. Like Garrison, Phillips denounced the Constitution for tolerating slavery. He disagreed with abolitionist Lysander Spooner and maintained that slavery was part of the Constitution, and more generally disputed Spooner's notion that any judge could find slavery illegal.

In 1845, in an essay titled "No Union With Slaveholders", he argued that the country would be better off, and not complicit in their guilt, if it let the slave states secede:

The experience of the fifty years...shows us the slaves trebling in numbers—slaveholders monopolizing the offices and dictating the policy of the Government—prostituting the strength and influence of the Nation to the support of slavery here and elsewhere—trampling on the rights of the free States, and making the courts of the country their tools. To continue this disastrous alliance longer is madness. The trial of fifty years only proves that it is impossible for free and slave States to unite on any terms, without all becoming partners in the guilt and responsible for the sin of slavery. Why prolong the experiment? Let every honest man join in the outcry of the American Anti-Slavery Society. (Quoted in Ruchames, ''The Abolitionists'' p. 196)

On December 8, 1837, in Boston's Faneuil Hall, Phillips' leadership and oratory established his preeminence within the abolitionist movement. Bostonians gathered at Faneuil Hall to discuss

On December 8, 1837, in Boston's Faneuil Hall, Phillips' leadership and oratory established his preeminence within the abolitionist movement. Bostonians gathered at Faneuil Hall to discuss Elijah P. Lovejoy

Elijah Parish Lovejoy (November 9, 1802 – November 7, 1837) was an American Presbyterianism, Presbyterian Minister (Christianity), minister, journalist, Editing, newspaper editor, and Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist. Followin ...

's murder by a mob outside his abolitionist newspaper's office in Alton, Illinois, on November 7. Lovejoy died defending himself and his press from pro-slavery rioters who set fire to a warehouse storing his press and shot Lovejoy as he stepped outside to tip a ladder being used by the mob. His death engendered a national controversy between abolitionists and anti-abolitionists.

At Faneuil Hall, Massachusetts attorney general James T. Austin

James Trecothick Austin (January 7, 1784 – May 8, 1870) was the 22nd Massachusetts Attorney General. Austin was the son of Massachusetts Secretary of the Commonwealth, and Treasurer and Receiver-General of Massachusetts Jonathan L. Austin. ...

defended the pro-slavery mob, comparing their actions to 1776 patriots who fought against the British and declaring that Lovejoy "died as the fool dieth!"

Trip to Europe

The married couple went abroad in 1839 for two years. They spent the summer in Great Britain and the rest of each year in mainland Europe. They made important connections and Ann wrote of them meetingElizabeth Pease

Elizabeth Nichol (''née'' Pease; 5 January 1807 – 3 February 1897) was a 19th-century British Abolitionism in the United Kingdom, abolitionist, anti-segregationist, women's suffrage, woman suffragist, chartism, chartist and anti-vivisectionis ...

and being particularly impressed by the Quaker abolitionist Richard D. Webb

Richard Davis Webb (1805–1872) was an Irish publisher and abolitionist.

Life

Webb was born in 1805. In 1837, he was one of three founding members, with James Haughton and Richard Allen, of the Hibernian Antislavery Association. This was not ...

. In 1840 they went to London to join up with other American delegates to the World Anti-Slavery Convention at the Exeter Hall in London. Phillips' new wife was one of a number of female delegates, who included Lucretia Mott, Mary Grew

Mary Grew (September 1, 1813 – October 10, 1896) was an American abolitionist and suffragist whose career spanned nearly the entire 19th century. She was a leader of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society and the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery ...

, Sarah Pugh, Abby Kimber, Elizabeth Neall and Emily Winslow. The delegates were astounded to find that female delegates had not been expected and they were not welcome at the convention.

Instructed by his wife not to "shilly-shally", Phillips went in to appeal the case. According to the history of the women's rights movement

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

of Susan B. Anthony's and Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 Seneca ...

, Phillips spoke as the convention opened, scolding the organizers for precipitating an unnecessary conflict:

The efforts of Phillips and others were only partly successful. The women were allowed in but had to sit separately and were not allowed to talk. This event has been taken by Stanton, Anthony, and others as the point at which the women's rights movement began.

Before the Civil War

In 1854, Phillips was indicted for his participation in the celebrated attempt to rescueAnthony Burns

Anthony Burns (May 31, 1834 – July 17, 1862) was an African-American man who escaped from slavery in Virginia in 1854. His capture and trial in Boston, and transport back to Virginia, generated wide-scale public outrage in the North and ...

, a captured fugitive slave

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th century to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called free ...

, from a jail in Boston.

After John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

was executed in December 1859, Phillips attended and spoke at his funeral, at the John Brown Farm

The John Brown Farm State Historic Site includes the home and final resting place of abolitionist John Brown (1800–1859). It is located on John Brown Road in the town of North Elba, 3 miles (5 km) southeast of Lake Placid, New York, whe ...

in remote North Elba, New York. He met Mary Brown and the coffin in Troy, New York, where she changed trains, and expressed, unsuccessfully, his wish that Brown would be buried, with a monument, in Mt. Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which he felt would help the abolitionist cause. He spoke at the funeral and on the way home, repeated his speech the next night to a wildly enthusiastic audience in Vergennes, Vermont.

On the eve of the Civil War, Phillips gave a speech at the New Bedford Lyceum in which he defended the Confederate States' right to secede:

In 1860 and 1861, many abolitionists welcomed the formation of the Confederacy

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between ...

because it would end the South

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

's stranglehold over the United States government. This position was rejected by nationalists like Abraham Lincoln, who insisted on holding the Union together while gradually ending slavery. Twelve days after the attack on Fort Sumter, Phillips announced his "hearty and hot" support for the war. Disappointed with what he regarded as Lincoln's slow action, Phillips opposed his reelection in 1864, breaking with Garrison, who supported a candidate for the first time.

In the mid-1862, Phillips's nephew, Samuel D. Phillips, died at Port Royal, South Carolina, where he had gone to take part in the so-called Port Royal Experiment to assist the slave population there in the transition to freedom.

In the mid-1862, Phillips's nephew, Samuel D. Phillips, died at Port Royal, South Carolina, where he had gone to take part in the so-called Port Royal Experiment to assist the slave population there in the transition to freedom.

Women's rights activism

Phillips was also an early advocate of women's rights. In 1840 he led the unsuccessful effort at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London to have America's women delegates seated. In the July 3, 1846, issue of ''The Liberator

Liberator or The Liberators or ''variation'', may refer to:

Literature

* ''Liberators'' (novel), a 2009 novel by James Wesley Rawles

* ''The Liberators'' (Suvorov book), a 1981 book by Victor Suvorov

* ''The Liberators'' (comic book), a Britis ...

'' he called for securing women's rights to their property and earnings as well as to the ballot. He wrote:

In 1849 and 1850, he assisted Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone (August 13, 1818 – October 18, 1893) was an American orator, abolitionist and suffragist who was a vocal advocate for and organizer promoting rights for women. In 1847, Stone became the first woman from Massachusetts to earn a colle ...

in conducting the first woman suffrage petition campaign in Massachusetts, drafting for her both the petition and an appeal for signatures. They repeated the effort the following two years, sending several hundred signatures to the state legislature. In 1853, they directed their petition to a convention charged with revising the state constitution, and sent it petitions bearing five thousand signatures. Together Phillips and Stone addressed the convention's Committee on Qualifications of Voters on May 27, 1853. In 1854, Phillips helped Stone call a New England Woman's Rights convention to expand suffrage petitioning into the other New England states.

Phillips was a member of the National Woman's Rights Central Committee, which organized annual conventions throughout the 1850s, published its Proceedings, and executed plans adopted by the conventions. He was a close adviser of Lucy Stone, and a major presence at most of the conventions, for which he wrote resolutions defining the movement's principles and goals. His address to the 1851 convention, later called "Freedom for Woman", was used as a women's rights tract into the twentieth century. In March 1857, Phillips and Stone were granted hearings by the Massachusetts and Maine legislatures on the woman suffrage memorial sent to twenty-five legislatures by the 1856 National Woman's Rights Convention. As the movement's treasurer, Phillips was trustee with Lucy Stone and Susan B. Anthony of a $5,000 fund given anonymously to the movement in 1858, called the "Phillips fund" until the death of the benefactor, Francis Jackson, in 1861, and thereafter the "Jackson Fund".

Postwar activism

Phillips's philosophical ideal was mainly self-control of the animal, physical self by the human, rational mind, although he admired martyrs like Elijah Lovejoy andJohn Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

. Historian Gilbert Osofsky has argued that Phillips's nationalism was shaped by a religious ideology derived from the European Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

, as expressed by Thomas Paine, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

. The Puritan ideal of a Godly Commonwealth through a pursuit of Christian morality and justice, however, was the main influence on Phillips's nationalism. He favored getting rid of American slavery by letting the slave states secede, and he sought to amalgamate all the American "races". Thus, it was the moral end which mattered most in Phillips's nationalism.

Reconstruction Era activism

As Northern victory in the Civil War seemed more imminent, Phillips, like many other abolitionists, turned his attention to the questions of Reconstruction. In 1864, he gave a speech at theCooper Institute

The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art (Cooper Union) is a private college at Cooper Square in New York City. Peter Cooper founded the institution in 1859 after learning about the government-supported École Polytechnique in ...

in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

arguing that enfranchisement of freedmen should be a necessary condition for the readmission of Southern states to the Union. Unlike other white abolitionist leaders such as Garrison

A garrison (from the French ''garnison'', itself from the verb ''garnir'', "to equip") is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a mil ...

, Phillips thought that securing civil and political rights for freedmen was an essential component of the abolitionist cause, even after the formal legal end of slavery. Along with Frederick Douglass, Phillips argued that without voting rights, the rights of freedmen would be "ground to powder" by white Southerners.

He lamented the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment without provisions for black suffrage, and fervently opposed the Reconstruction regime of President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

, affixing a new masthead to the ''National Anti-Slavery Standard

The ''National Anti-Slavery Standard'' was the official weekly newspaper of the American Anti-Slavery Society, established in 1840 under the editorship of Lydia Maria Child and David Lee Child. The paper published continuously until the ratifi ...

'' newspaper which read "Defeat the Amendment–Impeach the President." As Radical Republicans in Congress broke with Johnson and pursued their own Reconstruction policies through the Freedmen's Bureau bills The Freedmen's Bureau bills provided legislative authorization for the Freedmen's Bureau (formally known as the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands), which was set up by U.S. President Abraham Lincoln in 1865 as part of the United Stat ...

and the Civil Rights Act of 1866

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 (, enacted April 9, 1866, reenacted 1870) was the first United States federal law to define citizenship and affirm that all citizens are equally protected by the law. It was mainly intended, in the wake of the Amer ...

, their views converged increasingly with Phillips'. However, most congressional Republicans disagreed with his assertion that "suffrage is nothing but a name because the voter has not...an acre from which he could retire from the persecution of landlordism"; in other words, Phillips and the Republicans diverged on the issue of land redistribution to the freedmen.

Despite his belief that Ulysses S. Grant was not suited for the presidential office and dissatisfaction with Grant's and the party's refusal to endorse his comprehensive Reconstruction program of "land, education and the ballot", Phillips supported Grant and the Republican Party in the 1868 election. The Republicans did pass the Fifteenth Amendment constitutionalizing black suffrage in 1870, but the goal of land redistribution was never realized.

In 1879, Phillips argued that black suffrage and political participation during Reconstruction had not been a failure, and that the main error of the era had been the failure to redistribute land to the freedmen. He defended black voters as being "less purchasable than the white man," credited black labor and rule for the nascent regrowth of the Southern economy, and commended black bravery against attacks from the first Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

.

As the Reconstruction era came to a close, Phillips increased his attention to other issues, such as women's rights, universal suffrage, temperance, and the labor movement

The labour movement or labor movement consists of two main wings: the trade union movement (British English) or labor union movement (American English) on the one hand, and the political labour movement on the other.

* The trade union movement ...

.

Equal rights for Native Americans

Phillips was also active in efforts to gain equal rights for Native Americans, arguing that the Fifteenth Amendment also granted citizenship to Indians. He proposed that theAndrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

administration create a cabinet-level post that would guarantee Indian rights. Phillips helped create the Massachusetts Indian Commission with Indian rights activist Helen Hunt Jackson and Massachusetts governor William Claflin. Although publicly critical of President Ulysses S. Grant's drinking, he worked with Grant's second administration on the appointment of Indian agents

From the 1870s until the 1960s, an Indian agent was the Government of Canada, Canadian government's representative on First Nations in Canada, First Nations Indian reserve, reserves. The role of the Indian agent in Canadian history has never been ...

. Phillips lobbied against military involvement in the settling of Native American problems on the Western frontier. He accused General Philip Sheridan of pursuing a policy of Indian extermination.

Public opinion turned against Native American advocates after the Battle of the Little Bighorn in July 1876, but Phillips continued to support the land claims of the Lakota (Sioux). During the 1870s, Phillips arranged public forums for reformer Alfred B. Meacham and Indians affected by the country's Indian removal

Indian removal was the United States government policy of forced displacement of self-governing tribes of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi Riverspecifically, to a de ...

policy, including the Ponca chief Standing Bear, and the Omaha

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest city ...

writer and speaker Susette LaFlesche Tibbles.

Illness and death

By late January 1884, Phillips was suffering fromheart disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a class of diseases that involve the heart or blood vessels. CVD includes coronary artery diseases (CAD) such as angina and myocardial infarction (commonly known as a heart attack). Other CVDs include stroke, hea ...

. Phillips delivered his last public address on January 26, 1884, over the objections of his physician."Wendell Phillips: Anecdotes of the Great Orator by One of His Old-time Friends". ''The Washington Post''. February 10, 1884. p. 6. Phillips spoke at the unveiling of a statue to Harriet Martineau. At the time of the speech, he said that he thought it would be his last.

Phillips died in his home, on Common Street in Boston's neighborhood of Charlestown, on February 2, 1884."Wendell Phillips Dead: The Last Hours of One of the Apostles of Abolition". ''The New York Times''. February 3, 1884. p. 1.

A solemn funeral was held at Hollis Street Church four days later."Wendell Phillips Buried: A Great Demonstration of Respect to the Dead Orator". ''The New York Times''. February 7, 1884. p. 1. His body was taken to Faneuil Hall, where it lay in state for several hours. Phillips was then buried at Granary Burying Ground. In April 1886, his remains were exhumed and reburied at Milton Cemetery in Milton

Milton may refer to:

Names

* Milton (surname), a surname (and list of people with that surname)

** John Milton (1608–1674), English poet

* Milton (given name)

** Milton Friedman (1912–2006), Nobel laureate in Economics, author of '' Free t ...

.

On February 12, a memorial service was held at the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church on Sullivan Street in New York City."Services in Memory of Mr. Phillips". ''The New York Times''. February 13, 1884. p. 5. Rev. William B. Derrick

William B. Derrick (July 27, 1843 – April 15, 1913) was an African Methodist Episcopal (AME) bishop and missionary. He worked as a seaman early in his life and served in the Union Navy during the US Civil War. After the war, he joined the AME ...

gave a eulogy, describing Phillips as a friend of humanity and a citizen of the world. Timothy Thomas Fortune also eulogized Phillips, calling him a reformer who was as bold as a lion, who had reformed a great wrong, and who had left a rejuvenated Constitution.

On February 8, in the U.S. House of Representatives, John F. Finerty

John Frederick Finerty (September 10, 1846 – June 10, 1908) was a United States House of Representatives, U.S. Representative from Illinois.

Biography

Born in Galway, Ireland, Finerty completed preparatory studies. He immigrated to the Unit ...

offered resolutions of respect to the memory of Phillips."Congressional Notes". ''The Washington Post''. February 9, 1884. p. 1. William W. Eaton

William Wallace Eaton (October 11, 1816September 21, 1898) was a United States representative and United States senator from Connecticut.

Biography

Born in Tolland, Connecticut, he was educated in the common schools and by private instruction ...

objected to the resolutions.

A memorial event was held in Tremont Temple, Boston, on April 9, 1884. Archibald Grimké delivered a eulogy.

Irish poet and journalist John Boyle O'Reilly, who was a good friend of Phillips, wrote the poem ''Wendell Phillips'' in his honor.

Recognition and legacy

In 1904, the Chicago Public Schools opened

In 1904, the Chicago Public Schools opened Wendell Phillips High School

Wendell Phillips Academy High School is a public 4–year high school located in the Bronzeville neighborhood on the south side of Chicago, Illinois, United States. Phillips is part of the Chicago Public Schools district and is managed by the Acad ...

in the Bronzeville neighborhood on the south side of Chicago in Phillips's honor.

In July 1915, a monument was erected in Boston Public Garden to commemorate Phillips, inscribed with his words: "Whether in chains or in laurels, liberty knows nothing but victories." Jonathan Harr's "A Civil Action" refers to the statue in recounting Mark Phillips,' a descendant of Wendell Phillips,' reaction to a legal victory in the case against W.R. Grace & Co. et al.

The Phillips community in Minneapolis was named after him.

A phrase from his speech of January 20, 1861, "I think the first duty of society is justice," sometimes wrongly attributed to Alexander Hamilton, appears on various courthouses around the United States, including in Nashville, Tennessee.

The Wendell Phillips School in Washington, D.C., was named in his honor in 1890. The school closed in 1950 and was turned into the Phillips School Condominium in 2002.

Bibliography

* *See also

* Dyer Lum, labor activist and abolitionist who ran for Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts on Phillips's ticket.Notes

References

Further reading

* Aisèrithe, A.J. and Donald Yacovone (eds.), ''Wendell Phillips, Social Justice, and the Power of the Past.'' Baton Rouge, LA: LSU Press, 2016. * Bartlett, Irving H. "The Persistence of Wendell Phillips," in Martin Duberman (ed.), ''The Antislavery Vanguard: New Essays on the Abolitionists.'' Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1965; pp. 102–122. * Bartlett, Irving H. ''Wendell and Ann Phillips: The Community of Reform, 1840–1880.'' New York: W.W. Norton, 1982. * Bartlett, Irving H. ''Wendell Phillips: Brahmin Radical.'' Boston: Beacon Press, 1961. * Debs, Eugene V."Wendell Phillips: Orator and Abolitionist,"

''Pearson's Magazine,'' vol. 37, no. 5 (May 1917), pp. 397–402. * Filler, Louis (ed.), "Wendell Phillips on Civil Rights and Freedom," New York: Hill and Wang, 1965. * Hofstadter, Richard. "Wendell Phillips: The Patrician as Agitator" in ''The American Political Tradition: And the Men Who Made It.'' New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1948. * Osofsky, Gilbert. "Wendell Phillips and the Quest for a New American National Identity" ''Canadian Review of Studies in Nationalism,'' vol. 1, no. 1 (1973), pp. 15–46. * Stewart, James Brewer. ''Wendell Phillips: Liberty's Hero.'' LSU Press, 1986. 356 pp. * Stewart, James B. "Heroes, Villains, Liberty, and License: The Abolitionist Vision of Wendell Phillips" in ''Antislavery Reconsidered: New Perspectives on the Abolitionists'' Baton Rouge, LA: LSU Press, 1979; pp. 168–191.

External links

* * *'Toussaint L'Ouverture' A lecture by Wendell Phillips (1861)

The Liberator Files

Items concerning Wendell Phillips from Horace Seldon's collection and summary of research of William Lloyd Garrison's ''The Liberator'' original copies at the Boston Public Library, Boston, Massachusetts.

Letters, 1855, n.d..

Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University. * The story of ''The Liberator'' is retold in the 1950 radio drama

The Liberators (Part I)

, a presentation from '' Destination Freedom'', written by Richard Durham {{DEFAULTSORT:Phillips, Wendell 1811 births 1884 deaths Abolitionists from Boston Boston Latin School alumni Harvard Law School alumni Harvard College alumni Lawyers from Boston American male feminists American feminists Activists for Native American rights People of Massachusetts in the American Civil War Phillips family (New England) American temperance activists Burials at Granary Burying Ground American lecturers