Zygmunt Szendzielarz on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Zygmunt Szendzielarz (12 March 1910 – 8 February 1951) was the commander of the

With his unit, he took part in the 1939

With his unit, he took part in the 1939  ''Łupaszko's'' unit fought against the German army and SS units in the area of southern Wilno Voivodeship, but was also frequently attacked by the Soviet Partisans paradropped in the area by the

''Łupaszko's'' unit fought against the German army and SS units in the area of southern Wilno Voivodeship, but was also frequently attacked by the Soviet Partisans paradropped in the area by the

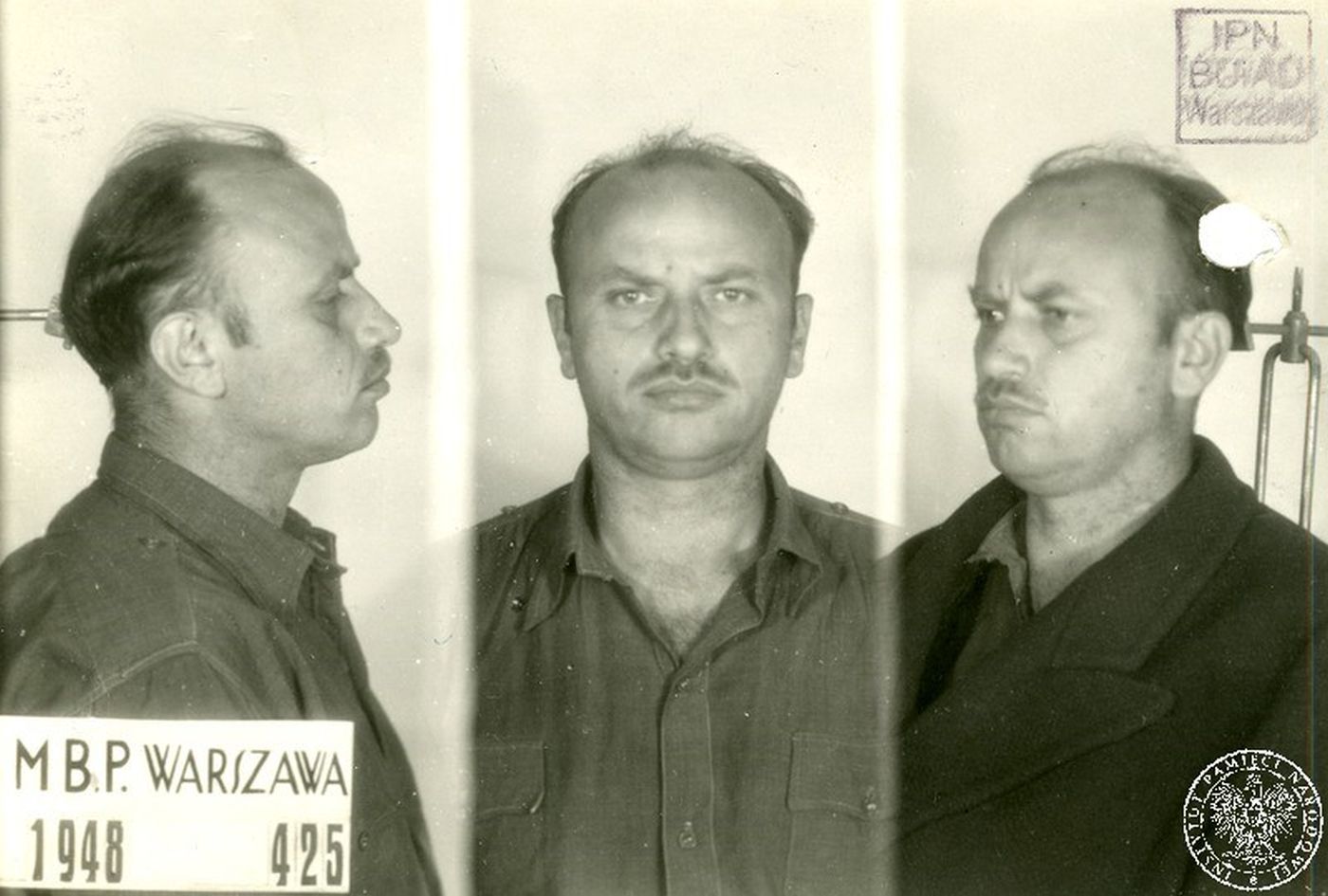

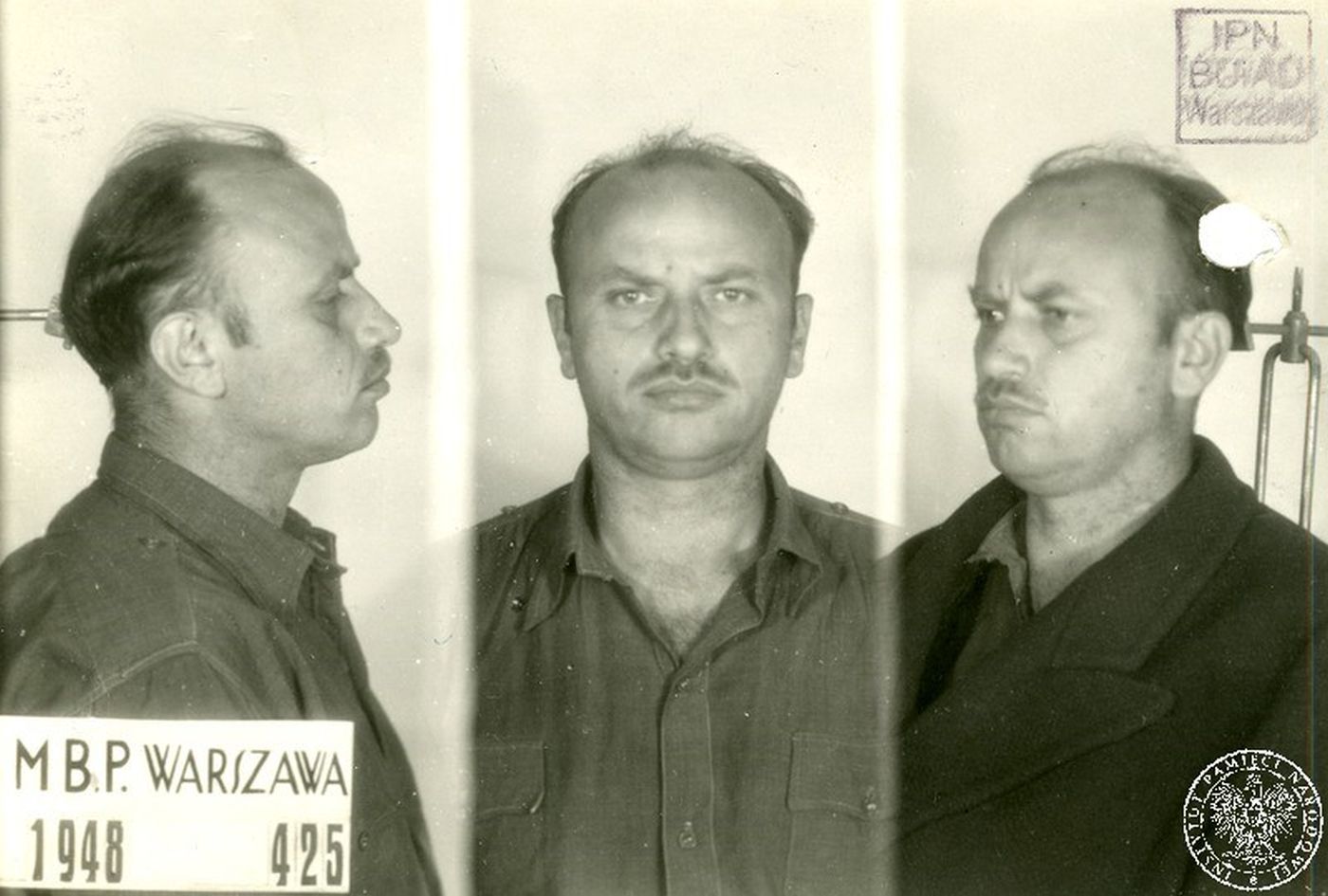

After several years underground, he was arrested by the UB on 28 June 1948, in Osielec near

After several years underground, he was arrested by the UB on 28 June 1948, in Osielec near

Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

5th Wilno

Vilnius ( , ; see also #Etymology and other names, other names) is the capital and List of cities in Lithuania#Cities, largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the munic ...

Brigade of the Home Army

The Home Army ( pl, Armia Krajowa, abbreviated AK; ) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) est ...

(Armia Krajowa), nom de guerre "Łupaszka". He fought against the Red Army after the end of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. Following the Soviet takeover of Poland at the end of World War II he was arrested, accused of numerous crimes and executed in the Mokotów Prison

Mokotów Prison ( pl, Więzienie mokotowskie, also known as ''Rakowiecka Prison'') is a prison in Warsaw's borough of Mokotów, Poland, located at 37 Rakowiecka Street. It was built by the Russians in the final years of the foreign Partitions of ...

as one of the anti-communist cursed soldiers

The "cursed soldiers" (also known as "doomed soldiers", "accursed soldiers" or "damned soldiers"; pl, żołnierze wyklęci) or "indomitable soldiers" ( pl, żołnierze niezłomni) is a term applied to a variety of anti-Soviet and anti-communist ...

. After the fall of communism

The Revolutions of 1989, also known as the Fall of Communism, was a revolutionary wave that resulted in the end of most communist states in the world. Sometimes this revolutionary wave is also called the Fall of Nations or the Autumn of Nat ...

, in 1993, Szendzielarz was rehabilitated and declared innocent of all charges. In 2007 Polish president Lech Kaczyński

Lech Aleksander Kaczyński (; 18 June 194910 April 2010) was a Polish politician who served as the city mayor of Warsaw from 2002 until 2005, and as President of Poland from 2005 until his death in 2010. Before his tenure as president, he pre ...

posthumously awarded Szendzielarz with the order of Polonia Restituta

The Order of Polonia Restituta ( pl, Order Odrodzenia Polski, en, Order of Restored Poland) is a Polish state order established 4 February 1921. It is conferred on both military and civilians as well as on foreigners for outstanding achievement ...

. His involvement in the Dubingiai massacre

The Dubingiai massacre was a mass murder of 20–27 Lithuanian civilians in the town of Dubingiai (Dubinki) on 23 June 1944. The massacre was carried out by the 5th Brigade of Armia Krajowa (AK), a Polish resistance group, in reprisal for the ...

of 1944, however, remains controversial.

Life

Szendzielarz was born in Stryj (Austrian Partition

The Austrian Partition ( pl, zabór austriacki) comprise the former territories of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth acquired by the Habsburg monarchy during the Partitions of Poland in the late 18th century. The three partitions were conduct ...

, now Lviv Oblast

Lviv Oblast ( uk, Льві́вська о́бласть, translit=Lvivska oblast, ), also referred to as Lvivshchyna ( uk, Льві́вщина, ), ). The name of each oblast is a relational adjective—in English translating to a noun adjunct w ...

, Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

), then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and from 1919 to 1939 in Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, into the family of a railway worker. After graduating from primary school in Lwów, he attended a biological-mathematical '' gymnasium'' in Lwów and then Stryj. After graduating, he volunteered for the Polish Army

The Land Forces () are the land forces of the Polish Armed Forces. They currently contain some 62,000 active personnel and form many components of the European Union and NATO deployments around the world. Poland's recorded military history stre ...

and completed Infantry Non-commissioned officer School in Ostrów Mazowiecka

Ostrów Mazowiecka is a town in eastern Poland with 23,486 inhabitants (2004). Situated in the Masovian Voivodeship (since 1999), previously in Ostrołęka Voivodeship (1975–1998). It is the capital of Ostrów Mazowiecka County.

History

Ostr ...

(1932), then Cavalry NCO School in Grudziądz

Grudziądz ( la, Graudentum, Graudentium, german: Graudenz) is a city in northern Poland, with 92,552 inhabitants (2021). Located on the Vistula River, it lies within the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship and is the fourth-largest city in its prov ...

. He was promoted to lieutenant and transferred to Wilno

Vilnius ( , ; see also #Etymology and other names, other names) is the capital and List of cities in Lithuania#Cities, largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the munic ...

, where he assumed command of a squadron

Squadron may refer to:

* Squadron (army), a military unit of cavalry, tanks, or equivalent subdivided into troops or tank companies

* Squadron (aviation), a military unit that consists of three or four flights with a total of 12 to 24 aircraft, ...

in the 4th Uhlan Regiment.

World War II

With his unit, he took part in the 1939

With his unit, he took part in the 1939 September Campaign

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week af ...

. His unit was attached to the Wilno Cavalry Brigade under General Władysław Anders

)

, birth_name = Władysław Albert Anders

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Krośniewice-Błonie, Warsaw Governorate, Congress Poland, Russian Empire

, death_date =

, death_place = London, England, United Kingdom

, serviceyear ...

, part of the Prusy Army

The Prusy Army ( pl, Armia Prusy) was one of the Polish armies to fight during the Invasion of Poland in 1939. Created in the summer of 1939 as the main reserve of the Commander in Chief, it was commanded by Gen. Stefan Dąb-Biernacki. The word ' ...

. After retreating from northern Poland, the forces of Gen. Anders fought their way towards the city of Lwów and the Romanian Bridgehead

__NOTOC__

The Romanian Bridgehead ( pl, Przedmoście rumuńskie; ro, Capul de pod român) was an area in southeastern Poland that is now located in Ukraine. During the invasion of Poland in 1939 at the start of the Second World War), the Polish ...

. However, in the area of Lublin Szendzielarz's unit was surrounded and suffered heavy losses. Soon afterwards Szendzielarz was taken prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

by the Soviets

Soviet people ( rus, сове́тский наро́д, r=sovyétsky naród), or citizens of the USSR ( rus, гра́ждане СССР, grázhdanye SSSR), was an umbrella demonym for the population of the Soviet Union.

Nationality policy in ...

, but he managed to escape to Lwów, where he lived for a short period under a false name. He tried to cross the Hungarian border to escape from Poland and reach the Polish Army being formed in France, but failed and finally moved with his family to Wilno.

In Wilno, Szendzielarz started working on various posts under false names. In mid-1943 he joined the Home Army

The Home Army ( pl, Armia Krajowa, abbreviated AK; ) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) est ...

under the nom de guerre ''Łupaszka'', after Jerzy Dąbrowski

Jerzy Dąbrowski (September 8, 1899 – September 17, 1967) was a Polish aeronautical engineer. He was the lead designer of the famed PZL.37 Łoś medium bomber.

Dąbrowski was born in Nieborów, west of Warsaw to a railway clerk family. He stud ...

, and in August he started organizing his own partisan group in the forests surrounding the city. Soon the unit was joined by local volunteers and the remnants of a unit of Antoni Burzyński ("Kmicic"), destroyed by Soviet Partisans

Soviet partisans were members of resistance movements that fought a guerrilla war against Axis forces during World War II in the Soviet Union, the previously Soviet-occupied territories of interwar Poland in 1941–45 and eastern Finland. The ...

and the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

. By September, the unit was 700 men strong and was officially named the 5th Vilnian Home Army Brigade (''5 Wileńska Brygada Armii Krajowej'').

''Łupaszko's'' unit fought against the German army and SS units in the area of southern Wilno Voivodeship, but was also frequently attacked by the Soviet Partisans paradropped in the area by the

''Łupaszko's'' unit fought against the German army and SS units in the area of southern Wilno Voivodeship, but was also frequently attacked by the Soviet Partisans paradropped in the area by the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army ( Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, afte ...

. In April 1944, Zygmunt Szendzielarz was arrested by the Lithuanian police and handed over to the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one orga ...

. Łupaszko was free in the same month under circumstances that remain unclear. In reprisal actions, his brigade captured several dozen German officials and sent several threatening letters to Gestapo but it remains unknown if and how these contributed to his release.

Dubingiai massacre

On the 20 June 1944 a Lithuanian unit of theSchutzmannschaft

The ''Schutzmannschaft'' or Auxiliary Police ( "protective, or guard units"; plural: ''Schutzmannschaften'', abbreviated as ''Schuma'') was the collaborationist auxiliary police of native policemen serving in those areas of the Soviet Union and ...

murdered 39 Poles in Glinciszki, including women and children. Lithuanian collaborator units have also harassed civilian Polish population in Pawłów, Adamowszczyzna, and Sieńkowszczyzna. In reprisal, on 23 June 1944, a unit of 5th Vilnian Home Army Brigade attacked the fortified village of Dubingiai, capturing a bunker defended by Lithuanian policemen. The order to attack the village was given by Szendzielarz.Wołkonowski i Łukomski , page=256 Dubingiai became the target of the attack due to many of the policemen, and their families, responsible for the Glinciszki crime living there. Having the list of people who collaborated with the occupier, the Poles began action to avenge the death of the residents of Glinciszki. According to historian Paweł Rokicki, the actions in Dubingiai are a war crime, and the deaths of the civilians were intentional. In Dubingiai between 21 and 27 inhabitants of the village died, including women and children.

Operation Ostra Brama

In August, the commander of all Home Army units in the Wilno area, Gen. Aleksander "Wilk" Krzyżanowski, ordered all six brigades under his command to prepare forOperation Tempest

file:Akcja_burza_1944.png, 210px, right

Operation Tempest ( pl, akcja „Burza”, sometimes referred to in English as "Operation Storm") was a series of uprisings conducted during World War II against occupying German forces by the Polish Home ...

— a planned all-national rising against the German forces occupying Poland. In what became known as Operation Ostra Brama

, Second Polish Republic)

, coordinates =

, result = Failure of the operation

, combatant1 = Polish Secret State (Armia Krajowa)

, combatant2 =

, combatant3 =

, commander1 = Aleksander KrzyżanowskiAntoni Olechnowicz

, comman ...

, Brigade V was to attack the Wilno suburb of Zwierzyniec

Zwierzyniec (; uk, Звежинець, Zvezhynetsʹ) is a town on the Wieprz river in the Zamość County, Lublin Voivodeship, Poland. It has 3,324 inhabitants (2004).

Zwierzyniec is the northernmost town of the Roztocze National Park. The par ...

in cooperation with advancing units of the 3rd Belorussian Front

The 3rd Belorussian Front () was a Front of the Red Army during the Second World War.

The 3rd Belorussian Front was created on 24 April 1944 from forces previously assigned to the Western Front. Over 381 days in combat, the 3rd Belorussian Fr ...

. However, Łupaszko, for fear of being arrested with his units by the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

and killed on the spot, disobeyed orders and moved his unit to central Poland. Wilno was liberated by Polish and Soviet forces, and the Polish commander was then arrested by the Soviets and the majority of his men were sent to Gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= was the government agency in ...

s and sites of detention in the Soviet Union.

It is uncertain why Szendzielarz was not court-martialed for desertion. Most likely it was in fact General "Wilk" himself who ordered Łupaszko's unit away from the Wilno area, due to Łupaszko long having been involved in fighting with Soviet partisans and Wilk not wanting to provoke the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army ( Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, afte ...

. Regardless, after crossing into the Podlasie and Białystok area in October, the brigade continued the struggle against withdrawing Germans in the ranks of the Białystok Home Army Area. Zygmunt Szendzielarz, the commander of the 5th Brigade, was responsible for the massacres in the area on several Lithuanian and Belarusian villages. Łupaszko's unit remained in the forests and he decided to await the outcome of Russo-Polish talks held by the Polish Government in Exile. Meanwhile, the unit was reorganized and captured enough equipment to fully arm 600 men with machine guns and machine pistols.

After World War II

After the governments of the United Kingdom and the United States broke the pacts with Poland and accepted the communist "Polish Committee of National Liberation

The Polish Committee of National Liberation ( Polish: ''Polski Komitet Wyzwolenia Narodowego'', ''PKWN''), also known as the Lublin Committee, was an executive governing authority established by the Soviet-backed communists in Poland at the la ...

" as the provisional government of Poland, Łupaszka restarted hostilities—this time against the new oppressor, in the ranks of Wolność i Niezawisłość

Freedom and Independence Association ( pl, Zrzeszenie Wolność i Niezawisłość, or WiN) was a Polish underground anticommunist organisation founded on September 2, 1945 and active until 1952.

Political goals and realities

The main purpose of it ...

organization. However, after several successful actions against the NKVD units in the area of Białowieża Forest

Białowieża Forest; lt, Baltvyžių giria; pl, Puszcza Białowieska ; russian: Беловежская пуща, Belovezhskaya Pushcha is a forest on the border between Belarus and Poland. It is one of the last and largest remaining pa ...

, it became apparent that such actions would result in the total destruction of his unit.

Lidia Lwow and Zygmunt Szendzielarz in 1948

In February 1945 his wife died and the nurse Lidia Lwow-Eberle became his partner.

In September 1945, Zygmunt Szendzielarz moved with a large part of his unit to Gdańsk-Oliwa

Oliwa ( la, Oliva; csb, Òlëwa; german: Oliva) is a northern district of the city of Gdańsk, Poland. From east it borders Przymorze and Żabianka, from the north Sopot and from the south with the districts of Strzyża, VII Dwór and Brętow ...

, where he remained underground while preparing his unit for a new partisan offensive against the Soviet-backed communist authorities of Poland. On April 14, 1946, Szendzielarz finally mobilized his unit and headed for the Tuchola Forest

The Tuchola Forest, also known as Tuchola Pinewoods or Tuchola Conifer Woods, (the latter a literal translation of pl, Bory Tucholskie; csb, Tëchòlsczé Bòrë; german: Tuchler or Tucheler Heide) is a large forest complex near the town of Tuch ...

, where he started operations against the forces of the Internal Security Corps

The Internal Security Corps ( pl, Korpus Bezpieczeństwa Wewnętrznego, KBW) was a special-purpose military formation in Poland under democratic government, established by the Council of Ministers on 24 May 1945.

History

The KBW consisted of 10 ...

, Urząd Bezpieczeństwa

The Ministry of Public Security ( pl, Ministerstwo Bezpieczeństwa Publicznego), commonly known as UB or later SB, was the secret police, intelligence and counter-espionage agency operating in the Polish People's Republic. From 1945 to 1954 it w ...

and the communist authorities. Łupaszko was hoping that in the spring of 1946 the former Western Allies of Poland would start a new war against the Soviet Union and that the Polish underground units could prove useful in liberating Poland. However, when he realized that no such war was planned he decided to disband his unit. He saw the further fight as a waste of blood of his men and decided to retire from the open fight against the communists.

After several years underground, he was arrested by the UB on 28 June 1948, in Osielec near

After several years underground, he was arrested by the UB on 28 June 1948, in Osielec near Nowy Targ

Nowy Targ (Officially: ''Royal Free city of Nowy Targ'', Yiddish: ''Naymark'', Goral Dialect: ''Miasto'') is a town in southern Poland, in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship. It is located in the Orava-Nowy Targ Basin at the foot of the Gorce Mounta ...

. After more than two years of brutal interrogation and torture in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

's Mokotów Prison

Mokotów Prison ( pl, Więzienie mokotowskie, also known as ''Rakowiecka Prison'') is a prison in Warsaw's borough of Mokotów, Poland, located at 37 Rakowiecka Street. It was built by the Russians in the final years of the foreign Partitions of ...

he was sentenced to death on 2 November 1950 by the Soviet-controlled court-martial in Warsaw. He was executed on February 8, 1951, together with several other Home Army soldiers. Szendzielarz was 40 years old. His body was buried in an undisclosed location. During a 2013 exhumation Szendzielarz's remains were recovered and identified as one of roughly 250 bodies buried in a mass grave at the Meadow at Warsaw's Powązki Military Cemetery

Powązki Military Cemetery (; pl, Cmentarz Wojskowy na Powązkach) is an old military cemetery located in the Żoliborz district, western part of Warsaw, Poland. The cemetery is often confused with the older Powązki Cemetery, known colloquial ...

.

Posthumous history

After Łupaszko's death, communist authorities accused him of many crimes, from the crimes against humanity to robbery and common theft. In 1988 Szendzielarz was posthumously promoted to ''rotmistrz

__NOTOC__

(German and Scandinavian for "riding master" or "cavalry master") is or was a military rank of a commissioned cavalry officer in the armies of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Scandinavia, and some other countries. A ''Rittmeister'' is typic ...

'' and awarded the ''Virtuti Militari

The War Order of Virtuti Militari (Latin: ''"For Military Virtue"'', pl, Order Wojenny Virtuti Militari) is Poland's highest military decoration for heroism and courage in the face of the enemy at war. It was created in 1792 by Polish King St ...

'', Poland's highest military decoration, by Kazimierz Sabbat, the President of Poland

The president of Poland ( pl, Prezydent RP), officially the president of the Republic of Poland ( pl, Prezydent Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej), is the head of state of Poland. Their rights and obligations are determined in the Constitution of Pola ...

in exile.

After the fall of communism

The Revolutions of 1989, also known as the Fall of Communism, was a revolutionary wave that resulted in the end of most communist states in the world. Sometimes this revolutionary wave is also called the Fall of Nations or the Autumn of Nat ...

, in 1993, Szendzielarz was rehabilitated and declared innocent of all charges. His exection, like those of other "cursed soldiers

The "cursed soldiers" (also known as "doomed soldiers", "accursed soldiers" or "damned soldiers"; pl, żołnierze wyklęci) or "indomitable soldiers" ( pl, żołnierze niezłomni) is a term applied to a variety of anti-Soviet and anti-communist ...

" was overturned as a Communist judicial crime. On 2007 Polish president Lech Kaczyński

Lech Aleksander Kaczyński (; 18 June 194910 April 2010) was a Polish politician who served as the city mayor of Warsaw from 2002 until 2005, and as President of Poland from 2005 until his death in 2010. Before his tenure as president, he pre ...

posthumously awarded Szendzielarz with the order of Polonia Restituta

The Order of Polonia Restituta ( pl, Order Odrodzenia Polski, en, Order of Restored Poland) is a Polish state order established 4 February 1921. It is conferred on both military and civilians as well as on foreigners for outstanding achievement ...

. 11.11.2007

Honours and awards

*Virtuti Militari

The War Order of Virtuti Militari (Latin: ''"For Military Virtue"'', pl, Order Wojenny Virtuti Militari) is Poland's highest military decoration for heroism and courage in the face of the enemy at war. It was created in 1792 by Polish King St ...

, V class; for participation in the September 1939 campaign

* Cross of Valour (January 1944)

* Gold Cross, Virtuti Militari

The War Order of Virtuti Militari (Latin: ''"For Military Virtue"'', pl, Order Wojenny Virtuti Militari) is Poland's highest military decoration for heroism and courage in the face of the enemy at war. It was created in 1792 by Polish King St ...

(June 25, 1988) in recognition of outstanding deeds during the war

* Grand Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta

The Order of Polonia Restituta ( pl, Order Odrodzenia Polski, en, Order of Restored Poland) is a Polish state order established 4 February 1921. It is conferred on both military and civilians as well as on foreigners for outstanding achievement ...

, awarded by Polish President Lech Kaczynski

Lech may refer to:

People

* Lech (name), a name of Polish origin

* Lech, the legendary founder of Poland

* Lech (Bohemian prince)

Products and organizations

* Lech (beer), Polish beer produced by Kompania Piwowarska, in Poznań

* Lech Poznań ...

, November 11, 2007

See also

*Paweł Jasienica

Paweł Jasienica was the pen name of Leon Lech Beynar (10 November 1909 – 19 August 1970), a Polish historian, journalist, essayist and soldier.

During World War II, Jasienica (then, Leon Beynar) fought in the Polish Army, and later, the Ho ...

*List of Poles

This is a partial list of notable Polish or Polish-speaking or -writing people. People of partial Polish heritage have their respective ancestries credited.

Science

Physics

* Czesław Białobrzeski

* Andrzej Buras

* Georges Charpa ...

*Danuta Siedzikówna

Danuta Helena Siedzikówna (nom de guerre: ''Inka''; underground name: ''Danuta Obuchowicz''; 3 September 1928 – 28 August 1946) was a Polish medical orderly in the 4th Squadron of the 5th Wilno Brigade in Home Army. In 1946 she served with ...

References

Further reading

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Szendzielarz, Zygmunt 1910 births 1951 deaths People from Stryi People from the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria Polish Austro-Hungarians Polish Army officers Home Army members Cursed soldiers Recipients of the Gold Cross of the Virtuti Militari Recipients of the Cross of Valour (Poland) Polish anti-communists Grand Crosses of the Order of Polonia Restituta Executed military personnel Executed Polish people Polish torture victims People executed by the Polish People's Republic Polish People's Republic rehabilitations Polish people convicted of war crimes Burials at Powązki Military Cemetery