Zrinski-Frankopan Conspiracy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Magnate conspiracy, also known as the Zrinski- Frankopan Conspiracy ( hr, Zrinsko-frankopanska urota) in

By late 1663 and early 1664, the coalition had not only taken back Ottoman-conquered land but also cut off Ottoman supply lines and captured several Ottoman-held fortresses within Hungary. In the meantime, a large Ottoman army, led by the Grand Vizier

By late 1663 and early 1664, the coalition had not only taken back Ottoman-conquered land but also cut off Ottoman supply lines and captured several Ottoman-held fortresses within Hungary. In the meantime, a large Ottoman army, led by the Grand Vizier

In March 1671, the leaders of the group, including

In March 1671, the leaders of the group, including

The crackdown caused a number of former soldiers and other Hungarian nationals to rise up against the state in a sort of

The crackdown caused a number of former soldiers and other Hungarian nationals to rise up against the state in a sort of

''Wappenbuch: Der Adel des Königreichs Dalmatien'', Volume 4, part 3

(in German). Nürnberg: Bauer und Raspe, p. 44. * Friederich Heyer von Rosenfield (1873), "Counts Frangipani or Frankopanovich or Damiani di Vergada Gliubavaz Frangipani (Frankopan) Detrico", in

''Wappenbuch: Der Adel des Königreichs Dalmatien'', Volume 4, part 3

(in German). Nürnberg: Bauer und Raspe, p. 45. * Friederich Heyer von Rosenfield (1873), "Coats of arms of Counts Frangipani or Frankopanovich or Damiani di Vergada Gliubavaz Frangipani (Frankopan) Detrico", in

''Wappenbuch: Der Adel des Königreichs Dalmatien'', Volume 4, part 3

(in German). Nürnberg: Bauer und Raspe, taf. 30. * Victor Anton Duisin (1938), "Counts Damjanić Vrgadski Frankopan Ljubavac Detrico", in

"Zbornik Plemstva"

(in Croatian). Zagreb: Tisak Djela i Grbova, p. 155-156. * "Counts Damjanić Vrgadski Frankopan Ljubavac Detrico" in

in Croatian). Zagreb: on line.

Painting of Zrinski and Frankopan

Petar Zrinski and Fran Krsto Frankopan

{{Authority control 17th-century coups d'état and coup attempts Hungary under Habsburg rule 17th century in Croatia Frankopan family 1660s conflicts Conspiracies 17th century in the Habsburg Monarchy Croatia under Habsburg rule Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor

Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

, and Wesselényi conspiracy ( hu, Wesselényi-összeesküvés) in Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

, was a 17th-century attempt to throw off Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

and other foreign influences over Hungary and Croatia.Magyar Régészeti, Művészettörténeti és Éremtani Társulat. ''Művészettörténeti értesítő.'' (Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. 1976), 27 The attempted coup was caused by the unpopular Peace of Vasvár

The Peace of Vasvár was a treaty between the Habsburg monarchy and the Ottoman Empire which followed the Battle of Saint Gotthard of 1 August 1664 (near Mogersdorf, Burgenland), and concluded the Austro-Turkish War (1663–64). It held for abou ...

, struck in 1664 between Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

Leopold I and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. The poorly organized attempt at revolt gave the Habsburgs reason to clamp down on their opponents. It was named after Hungarian Count Ferenc Wesselényi

Count Ferenc Wesselényi de Hadad et Murány (1605 – Zólyomlipcse (Slovenská Ľupča), 23 March 1667) was a Hungarian military commander and the palatine of the Royal Hungary.

Life

He was the son of István Wesselényi, royal court counselo ...

, and by Croatian counts, brothers Nikola Zrinski

Nikola () is a given name which, like Nicholas, is a version of the Greek ''Nikolaos'' (Νικόλαος). It is common as a masculine given name in the South Slavic countries (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, North Macedonia, Montene ...

and Petar Zrinski

Petar IV Zrinski ( hu, Zrínyi Péter) (6 June 1621 – 30 April 1671) was Ban of Croatia (Viceroy) from 1665 to 1670, general and a writer. A member of the Zrinski noble family, he was noted for his role in the attempted Croatian-Hungarian Mag ...

and Petar's brother-in-law Fran Krsto Frankopan

Fran Krsto Frankopan ( hu, Frangepán Ferenc Kristóf; 4 March 1643 – 30 April 1671) was a Croatian baroque poet, nobleman and politician. He is remembered primarily for his involvement in the failed Zrinski-Frankopan conspiracy. He was a C ...

.

In the second half of the 17th century, Vienna was interested in centralising the administration of the state so that it could introduce a consistent economic policy of mercantilism

Mercantilism is an economic policy that is designed to maximize the exports and minimize the imports for an economy. It promotes imperialism, colonialism, tariffs and subsidies on traded goods to achieve that goal. The policy aims to reduce a ...

and so lay the foundations for an absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constitut ...

.Goldstein, Ivo, ''Croatia - A History (2011), Hurst&Company, London, pp 44.'' The main obstacle on that path was the independence of magnates. Nikola and Petar Zrinski and their associate Fran Krsto Frankapan resisted Vienna's policy and were angered by its leniency toward the Ottomans. The Habsburgs were paying more attention to their Western European goals and less to freeing Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

and Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

from Ottomans.

Causes

The expansion of the Ottoman Empire into Europe began in the middle of the 14th century leading to confrontation with bothSerbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

and the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

and culminating in the defeat of both nations in, respectively, the Battle of Kosovo (1389) and the Fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had begun o ...

(1453). The expansionist policy eventually brought them into conflict with the Habsburgs a number of times during the 16th and 17th centuries.Sugar, Peter F., Peter Hanak, and Frank Tibor, eds. ''A History of Hungary.'' (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), 113 After the 1526 Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; hu, mohácsi csata, tr, Mohaç Muharebesi or Mohaç Savaşı) was fought on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, Kingdom of Hungary, between the forces of the Kingdom of Hungary and its allies, led by Louis II, and thos ...

, the middle part of the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephen ...

was conquered; by the end of the 16th century, it was split into what has become known as the Tripartite: the Habsburg-ruled Royal Hungary to the north, the Ottoman-ruled ''pashaluk

Eyalets (Ottoman Turkish: ایالت, , English: State), also known as beylerbeyliks or pashaliks, were a primary administrative division of the Ottoman Empire.

From 1453 to the beginning of the nineteenth century the Ottoman local government ...

'' to the south, and Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

to the east. A difficult balancing act played itself out as supporters of the Habsburgs battled supporters of the Ottomans in a series of civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

s and wars of independence.Kontler, Laszlo. ''A History of Hungary.'' (New York: Palgrave MacMillan. 2002), 142

By September 1656, the stalemate between the two great powers of Eastern Europe began to shift as the Ottoman Sultan

The sultans of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı padişahları), who were all members of the Ottoman dynasty (House of Osman), ruled over the transcontinental empire from its perceived inception in 1299 to its dissolution in 1922. At its hei ...

Mehmed IV

Mehmed IV ( ota, محمد رابع, Meḥmed-i rābi; tr, IV. Mehmed; 2 January 1642 – 6 January 1693) also known as Mehmed the Hunter ( tr, Avcı Mehmed) was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1648 to 1687. He came to the throne at the a ...

with the aid of his Grand Vizier

Grand vizier ( fa, وزيرِ اعظم, vazîr-i aʾzam; ota, صدر اعظم, sadr-ı aʾzam; tr, sadrazam) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. The office of Grand Vizier was first ...

Köprülü Mehmed Pasha

Köprülü Mehmed Pasha ( ota, كپرولی محمد پاشا, tr, Köprülü Mehmet Paşa; or ''Qyprilliu'', also called ''Mehmed Pashá Rojniku''; 1575, Roshnik,– 31 October 1661, Edirne) was the founder of the Köprülü political dynas ...

set about reforming the Ottoman military

The military of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nun silahlı kuvvetleri) was the armed forces of the Ottoman Empire.

Army

The military of the Ottoman Empire can be divided in five main periods. The foundation era covers the ...

and preparing it for larger conflict. The changes made it possible for the Sultan to invade and conquer the Transylvanian-held areas of Hungary in May 1660. The ensuing battles killed the Transylvanian ruler George II Rákóczi

en, George II Rákóczi, house=Rákóczi, father=, mother= Zsuzsanna Lorántffy, religion=CalvinismGeorge II Rákóczi (30 January 1621 – 7 June 1660), was a Hungarian nobleman, Prince of Transylvania (1648-1660), the eldest son of George I ...

. Following a fairly easy victory against him, the Ottomans continued to occupy more and more of Transylvania and approached the borders of Royal Hungary.

The invasion of the Transylvanian state upset the balance in the region, and precipitated the involvement of many external actors. The Teutonic Order

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians on ...

had been expelled from Transylvania in 1225 and since then had been put under the sovereignty of the Pope in Rome, and had thus not been under the sovereignty of the Holy Crown of Hungary

The Holy Crown of Hungary ( hu, Szent Korona; sh, Kruna svetoga Stjepana; la, Sacra Corona; sk, Svätoštefanská koruna , la, Sacra Corona), also known as the Crown of Saint Stephen, named in honour of Saint Stephen I of Hungary, was the c ...

for many centuries. The Teutonic Grandmaster Leopold Wilhelm attempted in 1660 to once again allow the Teutonic Knights to obtain an important role in Hungary through involvement in the supreme command of the Military Frontier

The Military Frontier (german: Militärgrenze, sh-Latn, Vojna krajina/Vojna granica, Војна крајина/Војна граница; hu, Katonai határőrvidék; ro, Graniță militară) was a borderland of the Habsburg monarchy and l ...

, the defensive borderlands between the Habsburg and Ottoman domains.

These moves drew in Habsburg forces under Leopold I. Although initially reluctant to commit forces and cause an outright war with the Ottomans, he had by 1661 sent some 15,000 of his soldiers under his field marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered as ...

Raimondo Montecuccoli. Despite this intervention, the Ottoman invasion of Transylvania continued unabated.Ingrao, Charles. ''The Habsburg Monarchy; 1618–1815.'' 2nd. ed. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 66 In response, by 1662 Montecuccoli had been given another 15,000 soldiers and had taken up positions in Hungary to stop the Turkish advance. Adding to his forces was an army of native Croats and Hungarians led by the Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

n noble Nikola Zrinski

Nikola () is a given name which, like Nicholas, is a version of the Greek ''Nikolaos'' (Νικόλαος). It is common as a masculine given name in the South Slavic countries (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, North Macedonia, Montene ...

. Montecuccoli also had additional German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

support thanks to the diplomatic efforts of the Hungarian magnate Ferenc Wesselényi

Count Ferenc Wesselényi de Hadad et Murány (1605 – Zólyomlipcse (Slovenská Ľupča), 23 March 1667) was a Hungarian military commander and the palatine of the Royal Hungary.

Life

He was the son of István Wesselényi, royal court counselo ...

. This became important, especially because it showed that Hungarian leaders, without direct Habsburg involvement and perhaps backed up by France, could hold their own diplomacy in Rome. Eventually, the Teutonic Order would also send between 500 and 1000 elite knights to Hungary in support of the Imperial armies against the Ottomans.

By late 1663 and early 1664, the coalition had not only taken back Ottoman-conquered land but also cut off Ottoman supply lines and captured several Ottoman-held fortresses within Hungary. In the meantime, a large Ottoman army, led by the Grand Vizier

By late 1663 and early 1664, the coalition had not only taken back Ottoman-conquered land but also cut off Ottoman supply lines and captured several Ottoman-held fortresses within Hungary. In the meantime, a large Ottoman army, led by the Grand Vizier Köprülü Fazıl Ahmed Pasha Köprülü may refer to:

People

* Köprülü family (Kypriljotet), an Ottoman noble family of Albanian origin

** Köprülü era (1656–1703), the period in which the Ottoman Empire's politics were set by the Grand Viziers, mainly the Köprülü f ...

and numbering up to 100,000 men, was moving from Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

to the northwest. In June 1664, it attacked Novi Zrin

Novi Zrin ( hu, Zrínyiújvár or Új-Zrínyivár) was a fortress of the Zrinski ( Zrínyi in Hungarian) noble family built near the Donja Dubrava village in the northernmost part of Croatia (at the border village of Őrtilos in Hungary) on t ...

Castle in Međimurje County

Međimurje County (; hr, Međimurska županija ; hu, Muraköz megye) is a triangle-shaped county in the northernmost part of Croatia, roughly corresponding to the historical and geographical region of Međimurje. Despite being the smallest C ...

(northern Croatia) and conquered it after one-month-long siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition warfare, attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity con ...

. However, on August 1, 1664, the combined Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

armies of Germany, France, Hungary and the Habsburgs won a decisive victory against the Ottomans in the Battle of Saint Gotthard. Members of the Order of the Golden Fleece and the Teutonic Order distinguished themselves in the battle, and the new Teutonic Grandmaster Johann Caspar von Ampringen would later be made the Imperial governor of Hungary in 1673 for his role in the victory.

Following the Ottoman defeat, many Hungarians had assumed that the combined forces would continue their offensive to remove all Ottomans from Hungarian lands.Kontler; ''A History of Hungary''. 177. However, Leopold was more concerned with events unfolding in Habsburg Spain

Habsburg Spain is a contemporary historiographical term referring to the huge extent of territories (including modern-day Spain, a piece of south-east France, eventually Portugal, and many other lands outside of the Iberian Peninsula) ruled be ...

and the brewing conflict that would come to be known as the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

. Leopold saw no need to continue combat on his eastern front when he could return the region to balance and concentrate on potential conflict with France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

over the rights to the Spanish throne. Moreover, the Ottomans could have committed more troops within a year, and a prolonged struggle with the Ottomans was risky for Leopold. To end the Ottoman issue quickly, he signed what has come to be known as the Peace of Vasvár

The Peace of Vasvár was a treaty between the Habsburg monarchy and the Ottoman Empire which followed the Battle of Saint Gotthard of 1 August 1664 (near Mogersdorf, Burgenland), and concluded the Austro-Turkish War (1663–64). It held for abou ...

.

Despite the common victory, the treaty was largely a gain for the Ottomans. Its text, which inflamed Hungary's nobles, stated that the Habsburgs would recognize the Ottoman-controlled Michael I Apafi

Michael Apafi ( hu, Apafi Mihály; 3 November 1632 – 15 April 1690) was Prince of Transylvania from 1661 to his death.

Background

The Principality of Transylvania emerged after the disintegration of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary in the sec ...

as ruler of Transylvania and that Leopold would pay a final gift of 200,000 gold florin

The Florentine florin was a gold coin struck from 1252 to 1533 with no significant change in its design or metal content standard during that time. It had 54 grains (3.499 grams, 0.113 troy ounce) of nominally pure or 'fine' gold with a purcha ...

s to the Ottomans to secure a 20-year truce. While Leopold could concentrate on the issues in Spain, the Hungarians remained divided between two empires. Moreover, many Hungarian magnates were left feeling as if the Habsburgs had pushed them aside at their one opportunity for independence and security from Ottoman advances.Ingrao: The Habsburg Monarchy 1618–1815 p. 67.

Unfolding

One of the primary leaders of the conspiracy wasNikola Zrinski

Nikola () is a given name which, like Nicholas, is a version of the Greek ''Nikolaos'' (Νικόλαος). It is common as a masculine given name in the South Slavic countries (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, North Macedonia, Montene ...

, the Croatian ban who had led the native forces alongside the Habsburg commander Montecuccoli. By then, Zrinski had begun to plan a Hungary free of outside influence and with a population protected by the state rather than used by it. He hoped to create a united army with Croatian and Transylvanian support to free Hungary. However, he died within months during a struggle with a wild boar on a hunting trip; this left the revolt in the hands of Nikola Zrinski's younger brother Petar Petar ( sr, Петар, bg, Петър) is a South Slavic languages, South Slavic masculine given name, their variant of the Biblical name Petros (given name), Petros cognate to Peter (given name), Peter.

Derivative forms include Pero (given name) ...

as well as Ferenc Wesselényi

Count Ferenc Wesselényi de Hadad et Murány (1605 – Zólyomlipcse (Slovenská Ľupča), 23 March 1667) was a Hungarian military commander and the palatine of the Royal Hungary.

Life

He was the son of István Wesselényi, royal court counselo ...

.

The conspirators hoped to gain foreign aid in their attempts to free Hungary and even overthrow the Habsburgs. The conspirators entered into secret negotiations with a number of nations, including France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

and the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia, ...

, in an attempt to gain support. Wesselényi and his fellow magnates even made overtures to the Ottomans offering all of Hungary in return for the semblance of self-rule after the Habsburgs had been removed, but no state wanted to intervene. The Sultan, like Leopold, had no interest in renewed conflict; in fact, his court informed Leopold of the attempts being made by the conspirators in 1666.

While the warnings from the Sultan's court cemented the matter, Leopold already suspected the conspiracy. The Austrians had informants inside the group of nobles and had heard from several sources of their wide-ranging and almost desperate attempts to gain foreign and domestic aid. However, no action was taken because the conspirators had made little traction and were bound by inaction. Leopold seems to have considered their actions as only half-hearted schemes that were never truly serious. The conspirators invented a number of plots that they never carried out such as the November 1667 plot to kidnap Emperor Leopold, which failed to materialize.

After yet another failed attempt for foreign aid from the pasha

Pasha, Pacha or Paşa ( ota, پاشا; tr, paşa; sq, Pashë; ar, باشا), in older works sometimes anglicized as bashaw, was a higher rank in the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman political and military system, typically granted to governors, gener ...

of Buda

Buda (; german: Ofen, sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Budim, Будим, Czech and sk, Budín, tr, Budin) was the historic capital of the Kingdom of Hungary and since 1873 has been the western part of the Hungarian capital Budapest, on the ...

, Zrinski and several other conspirators turned themselves in. However, Leopold was content to grant them freedom to gain support from the Hungarian people. No action was taken until 1670, when the remaining conspirators began circulating pamphlets inciting violence against the Emperor and calling for invasion by the Ottoman Empire. They also called for an uprising of the Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

minority within Royal Hungary. When the conspiracy's ideals began to gain some support within Hungary, the official reaction was swift.

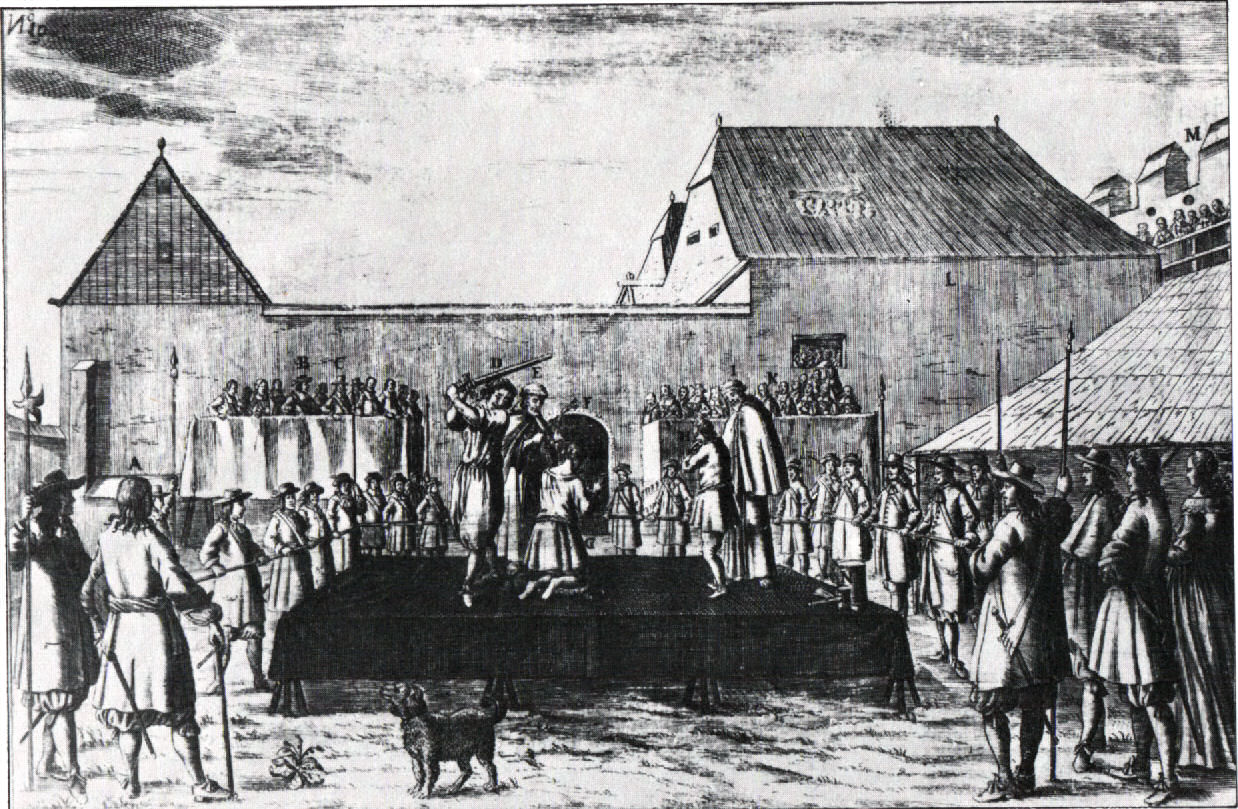

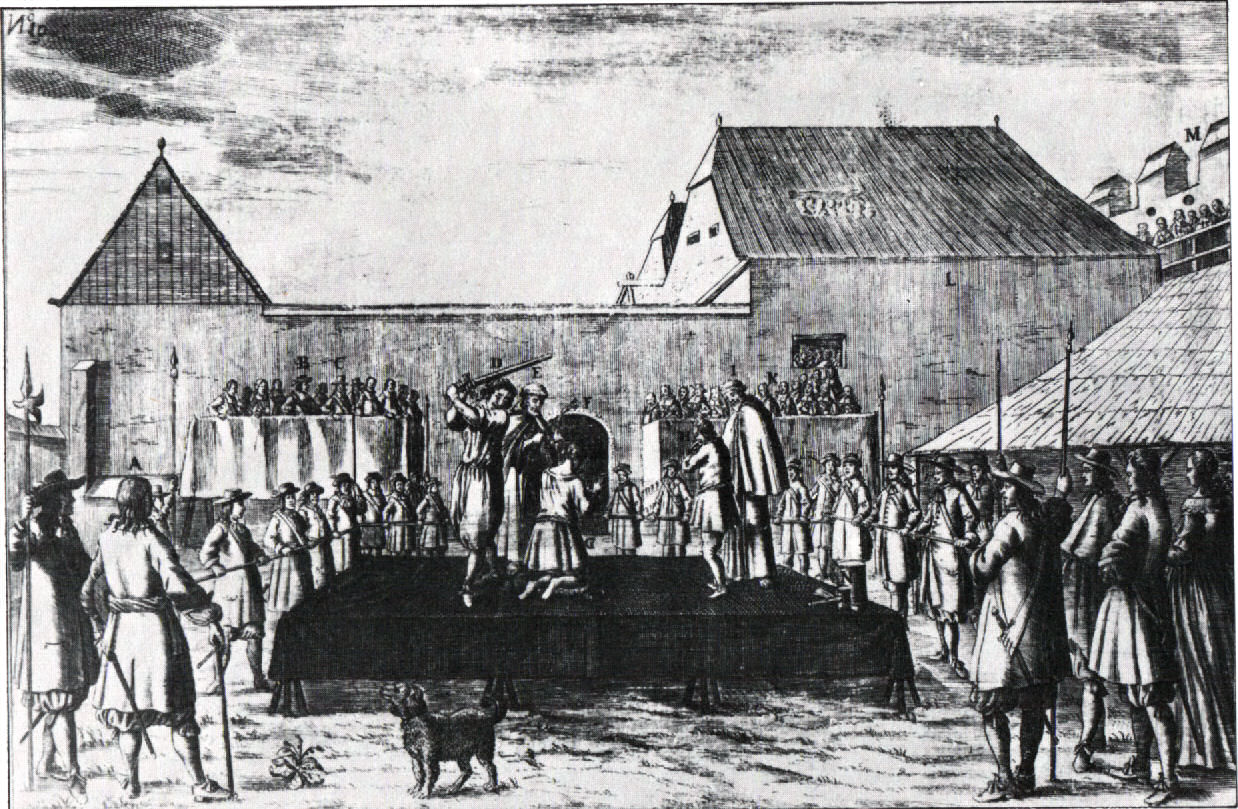

In March 1671, the leaders of the group, including

In March 1671, the leaders of the group, including Petar Zrinski

Petar IV Zrinski ( hu, Zrínyi Péter) (6 June 1621 – 30 April 1671) was Ban of Croatia (Viceroy) from 1665 to 1670, general and a writer. A member of the Zrinski noble family, he was noted for his role in the attempted Croatian-Hungarian Mag ...

, Fran Krsto Frankopan

Fran Krsto Frankopan ( hu, Frangepán Ferenc Kristóf; 4 March 1643 – 30 April 1671) was a Croatian baroque poet, nobleman and politician. He is remembered primarily for his involvement in the failed Zrinski-Frankopan conspiracy. He was a C ...

and Franz III. Nádasdy, were arrested and executed; some 2,000 nobles were arrested as part of a mass crackdown (many of the lesser nobles had had no part in the events, but Leopold aimed to prevent similar revolts in the future).

Persecution was also inflicted on Hungarian and Croatian commoners, as Habsburg soldiers moved in and secured the region. Protestant churches were burned to the ground in a show of force against any uprisings. Leopold ordered all Hungarian organic laws suspended in retaliation for the conspiracy. That gesture caused an end to the self-government which Royal Hungary had nominally been granted, which remained unchanged for the next 10 years. In Croatia, where Petar Zrinski had been a ban (viceroy) during the conspiracy, there would not be any new bans of Croatian origin for next 60 years.

Aftermath

Petar Zrinski

Petar IV Zrinski ( hu, Zrínyi Péter) (6 June 1621 – 30 April 1671) was Ban of Croatia (Viceroy) from 1665 to 1670, general and a writer. A member of the Zrinski noble family, he was noted for his role in the attempted Croatian-Hungarian Mag ...

and Fran Krsto Frankopan (Francesco Cristoforo Frangipani) were ordered to the Emperor's Court. The note said that, as they had ceased their rebellion and had repented soon enough, they would be given mercy from the Emperor if they would plead for it. They were arrested the moment they arrived in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

and put on trial. They were held in Wiener Neustadt

Wiener Neustadt (; ; Central Bavarian: ''Weana Neistod'') is a city located south of Vienna, in the state of Lower Austria, in northeast Austria. It is a self-governed city and the seat of the district administration of Wiener Neustadt-Land Distr ...

and beheaded on April 30, 1671. Nádasdy was executed on the same day, and Tattenbach was executed later on December 1, 1671.

In those ages, nobility enjoyed a few privileges that commoners did not. One of them was the right to be tried by a court assembled of peers. The conspirators were first tried by the Emperor's court assembly. After the verdict, they requested their rights as nobles. Another court was assembled of nobility from parts of the empire which were far away from Croatia or Hungary, and accepted the previous (death) verdict. Petar Zrinski's verdict read: "he committed the greatest sins than the others in aspiring to obtain the same station as his majesty, that is, to be an independent Croatian ruler and therefore he indeed deserves to be crowned not with a crown, but with a bloody sword".

During the trial and after the execution, the estates of the royal families were pillaged, and their families scattered. The destruction of these powerful feudal families ensured that no similar event took place until the bourgeois era. Petar's wife (Katarina Zrinska

Countess Ana Katarina Zrinska (c. 1625–1673) was a Croatian noblewoman and poet, born into the House of Frankopan, Croatian noble family. She married Count Petar Zrinski of the House of Zrinski in 1641 and later became known as Katarina Zrin ...

) and two of their daughters died in convents, and his son, Ivan

Ivan () is a Slavic languages, Slavic male given name, connected with the variant of the Greek name (English: John (given name), John) from Hebrew language, Hebrew meaning 'God is gracious'. It is associated worldwide with Slavic countries. T ...

, died mad after a terrible imprisonment and torture as did Katarina, the very symbol of Croatia's destiny. She published the last letter of her husband to her. It was a motivation to end the war with the Ottomans.

The bones of Zrinski and Frankopan (Frangipani) remained in Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

for 248 years, and it was only after the fall of the monarchy that their remains were moved to the crypt of Zagreb Cathedral

, native_name_lang =

, image = Zagreb Cathedral 2020.jpg

, imagesize =

, imagelink =

, imagealt =

, landscape =

, caption =Zagreb Cathedral in 2020, ...

.

Legacy in Hungary

Leopold I appointed a Directorium to administer Hungary in 1673, led by the Teutonic Order Grand Master Johann Caspar von Ampringen, which replaced thePalatine of Hungary

The Palatine of Hungary ( hu, nádor or , german: Landespalatin, la, palatinus regni Hungariae) was the highest-ranking office in the Kingdom of Hungary from the beginning of the 11th century to 1848. Initially, Palatines were represe ...

. The new government pursued a harsh crackdown against disloyal nobles and the Protestant movement. In order to combat the perceived threat from Hungary's Protestants against the Roman Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

in his lands, Leopold ordered some 60,000 forced conversions in the first two years of his reprisals for the conspiracy. In addition, 800 Protestant churches were closed down. By 1675, 41 Protestant pastor

A pastor (abbreviated as "Pr" or "Ptr" , or "Ps" ) is the leader of a Christian congregation who also gives advice and counsel to people from the community or congregation. In Lutheranism, Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy and ...

s would be publicly executed after having been found guilty of inciting riots and revolts.

guerilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tactic ...

. These ''Kuruc

Kuruc (, plural ''kurucok''), also spelled kurutz, refers to a group of armed anti-Habsburg insurgents in the Kingdom of Hungary between 1671 and 1711.

Over time, the term kuruc has come to designate Hungarians who advocate strict national ind ...

'' ("Crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were i ...

rs") began launching raids on the Habsburg army stationed within Hungary. For years after the crackdown, Kuruc rebels would gather en masse to combat the Habsburgs; their forces' numbers swelled to 15,000 by the summer of 1672.Indiana Press: A History of Hungary, p. 115.

These Kuruc forces were far more successful than the conspiracy, and remained active against the Habsburgs up until 1711; they were also more successful in convincing foreign governments of their ability to succeed. Foreign aid came first from Transylvania (which was under Ottoman suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is cal ...

) and later by the Ottoman Empire. This foreign recognition would eventually lead to a large-scale invasion of Habsburg domains by the Ottoman Empire and the Battle of Vienna in 1683.

Legacy in Croatia

The Ottoman conquests reduced Croatia's territory to only 16,800 km2 by 1592. The Pope referred to the country as the "Remnants of the remnants of the Croatian kingdom" ( la, Reliquiae reliquiarum regni Croatiae) and this description became a battle cry of the affected nobles. This loss was a death warrant for most Croatian noble families which only in 1526 voted that Habsburgs become kings ofCroatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

. Without any territory to control they have become only pages in history. Only the Zrinski

Zrinski () was a Croatian- Hungarian noble family, a cadet branch of the Croatian noble tribe of Šubić, influential during the period in history marked by the Ottoman wars in Europe in the Kingdom of Croatia's union with the Kingdom of Hung ...

and Frankopan families stayed powerful because their possessions were in the unconquered, western part of Croatia. In the time of the conspiracy, they were controlling around 35% of civilian Croatia (1/3 of Croatian territory was under the emperor's direct control as the Military Frontier

The Military Frontier (german: Militärgrenze, sh-Latn, Vojna krajina/Vojna granica, Војна крајина/Војна граница; hu, Katonai határőrvidék; ro, Graniță militară) was a borderland of the Habsburg monarchy and l ...

). After the conspiracy failed, these lands were confiscated by the emperor, who could grant them upon his discretion. Nothing better shows the situation in Croatia after the conspiracy than the fact that between 1527 - 1670 there were 13 bans (viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning "k ...

s) of Croatia of Croatian origin. But between 1670 and the revolution of 1848, there would be only 2 bans of Croatian nationality. The period from 1670 to the Croatian cultural revival in the 19th century was Croatia's political dark age. Since the Zrinski-Frankopan conspiracy up to the French Revolutions Wars in 1797, no soldiers were recruited from Istria, where in the 17th century a total of 3,000 soldiers had been recruited.

Conspirators

The leaders of the conspiracy were initiallyBan of Croatia

Ban of Croatia ( hr, Hrvatski ban) was the title of local rulers or office holders and after 1102, viceroys of Croatia. From the earliest periods of the Croatian state, some provinces were ruled by bans as a ruler's representative (viceroy) an ...

Nikola Zrinski

Nikola () is a given name which, like Nicholas, is a version of the Greek ''Nikolaos'' (Νικόλαος). It is common as a masculine given name in the South Slavic countries (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, North Macedonia, Montene ...

(viceroy of Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

) and Hungarian palatine Ferenc Wesselényi

Count Ferenc Wesselényi de Hadad et Murány (1605 – Zólyomlipcse (Slovenská Ľupča), 23 March 1667) was a Hungarian military commander and the palatine of the Royal Hungary.

Life

He was the son of István Wesselényi, royal court counselo ...

(viceroy of Hungary). The conspirators were soon joined by dissatisfied members of the noble families from Croatia and Hungary, like Nikola's brother Petar Petar ( sr, Петар, bg, Петър) is a South Slavic languages, South Slavic masculine given name, their variant of the Biblical name Petros (given name), Petros cognate to Peter (given name), Peter.

Derivative forms include Pero (given name) ...

(appointed Ban of Croatia after Nikola's death), Petar´s brother-in-law Fran Krsto Frankopan

Fran Krsto Frankopan ( hu, Frangepán Ferenc Kristóf; 4 March 1643 – 30 April 1671) was a Croatian baroque poet, nobleman and politician. He is remembered primarily for his involvement in the failed Zrinski-Frankopan conspiracy. He was a C ...

, elected Prince of Transylvania

The Prince of Transylvania ( hu, erdélyi fejedelem, german: Fürst von Siebenbürgen, la, princeps Transsylvaniae, ro, principele TransilvanieiFallenbüchl 1988, p. 77.) was the head of state of the Principality of Transylvania from the last d ...

and Petar´s son-in-law Francis I Rákóczi

Francis I Rákóczi (February 24, 1645, Gyulafehérvár, Transylvania – July 8, 1676, Zboró, Royal Hungary) was a Hungarian aristocrat, elected prince of Transylvania and father of Hungarian national hero Francis Rákóczi II.

Francis R� ...

, high justice of the Court of Hungary Franz III. Nádasdy and Esztergom archbishop (the Primate of Hungary) György Lippay

György () is a Hungarian version of the name ''George''. Some notable people with this given name:

* György Alexits, as a Hungarian mathematician

* György Almásy, Hungarian asiologist, traveler, zoologist and ethnographer, father of László ...

. The conspiracy and rebellion was entirely led by nobility. Nikola Zrinski, György Lippay and Ferenc Wesselényi died before the conspiracy was revealed. The remaining leaders Petar Zrinski, Fran Krsto Frankopan and Franz III. Nádasdy were all executed in 1671. Francis I Rákóczi was the only leading conspirator whose life was spared, due to his mother Sophia Báthory

Sophia means "wisdom" in Greek. It may refer to:

*Sophia (wisdom)

*Sophia (Gnosticism)

*Sophia (given name)

Places

* Niulakita or Sophia, an island of Tuvalu

*Sophia, Georgetown, a ward of Georgetown, Guyana

*Sophia, North Carolina, an unincorpo ...

's intervention and a ransom payment.

References

External links

* Friederich Heyer von Rosenfield (1873), "Counts Frangipani or Frankopanovich counts of Vegliae, Segniae, Modrussa, Vinodol or Damiani di Vergada Gliubavaz Frangipani (Frankopan) Detrico", in''Wappenbuch: Der Adel des Königreichs Dalmatien'', Volume 4, part 3

(in German). Nürnberg: Bauer und Raspe, p. 44. * Friederich Heyer von Rosenfield (1873), "Counts Frangipani or Frankopanovich or Damiani di Vergada Gliubavaz Frangipani (Frankopan) Detrico", in

''Wappenbuch: Der Adel des Königreichs Dalmatien'', Volume 4, part 3

(in German). Nürnberg: Bauer und Raspe, p. 45. * Friederich Heyer von Rosenfield (1873), "Coats of arms of Counts Frangipani or Frankopanovich or Damiani di Vergada Gliubavaz Frangipani (Frankopan) Detrico", in

''Wappenbuch: Der Adel des Königreichs Dalmatien'', Volume 4, part 3

(in German). Nürnberg: Bauer und Raspe, taf. 30. * Victor Anton Duisin (1938), "Counts Damjanić Vrgadski Frankopan Ljubavac Detrico", in

"Zbornik Plemstva"

(in Croatian). Zagreb: Tisak Djela i Grbova, p. 155-156. * "Counts Damjanić Vrgadski Frankopan Ljubavac Detrico" in

in Croatian). Zagreb: on line.

Painting of Zrinski and Frankopan

Petar Zrinski and Fran Krsto Frankopan

{{Authority control 17th-century coups d'état and coup attempts Hungary under Habsburg rule 17th century in Croatia Frankopan family 1660s conflicts Conspiracies 17th century in the Habsburg Monarchy Croatia under Habsburg rule Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor