Zinaida Gippius on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Zinaida Nikolayevna Gippius (Hippius) (; – 9 September 1945) was a Russian

Merezhkovsky and Gippius made a pact, each promising to concentrate on what he or she did best, the former on poetry, the latter on prose. The agreement collapsed as Zinaida translated

Merezhkovsky and Gippius made a pact, each promising to concentrate on what he or she did best, the former on poetry, the latter on prose. The agreement collapsed as Zinaida translated

In 1899—1901, encouraged by the group of authors associated with ''

In 1899—1901, encouraged by the group of authors associated with ''

The

The

Gippius saw the October Revolution as the end of Russia and the coming of the Kingdom of Antichrist. "It felt as if some pillow fell on you to strangle... Strangle what — the city? The country? No, something much, much bigger," — she wrote in her 26 October 1917, diary entry. In late 1917 Gippius was still able to publish her anti-Bolshevik verses in what remained of the old newspapers, but the next year was nightmarish, according to her ''Diaries''. Ridiculing H. G. Wells ("I can see why he is so attracted to the Bolsheviks: they’ve leapfrogged him"), she wrote of Cheka atrocities ("In Kiev 1200 officers killed; legs severed, boots taken off." — 23 February. "In

Gippius saw the October Revolution as the end of Russia and the coming of the Kingdom of Antichrist. "It felt as if some pillow fell on you to strangle... Strangle what — the city? The country? No, something much, much bigger," — she wrote in her 26 October 1917, diary entry. In late 1917 Gippius was still able to publish her anti-Bolshevik verses in what remained of the old newspapers, but the next year was nightmarish, according to her ''Diaries''. Ridiculing H. G. Wells ("I can see why he is so attracted to the Bolsheviks: they’ve leapfrogged him"), she wrote of Cheka atrocities ("In Kiev 1200 officers killed; legs severed, boots taken off." — 23 February. "In

Their first destination was

Their first destination was

Modern scholars see Gippius's romantically tinged early poems as mostly derivative, Semyon Nadson and

Modern scholars see Gippius's romantically tinged early poems as mostly derivative, Semyon Nadson and

English translations of 3 poems by Babette Deutsch and Avrahm Yarmolinsky, 1921

* ttp://stihipoeta.ru/poety-serebryanogo-veka/zinaida-gippius/ Zinaida Gippius poetrya

Stihipoeta.ruThe Green Ring

(play) from archive.org * {{DEFAULTSORT:Gippius, Zinaida 1869 births 1945 deaths People from Tula Oblast People from Belyovsky Uyezd Russian people of German descent Women writers from the Russian Empire Russian religious leaders Symbolist poets Russian editors Russian women editors Russian dramatists and playwrights Russian women short story writers Russian women poets Russian women dramatists and playwrights 20th-century Russian poets 20th-century Russian women writers 20th-century Russian short story writers Emigrants from the Russian Empire to France Burials at Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois Russian Cemetery

poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator ( thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems ( oral or wr ...

, playwright

A playwright or dramatist is a person who writes plays.

Etymology

The word "play" is from Middle English pleye, from Old English plæġ, pleġa, plæġa ("play, exercise; sport, game; drama, applause"). The word "wright" is an archaic English ...

, novelist

A novelist is an author or writer of novels, though often novelists also write in other genres of both fiction and non-fiction. Some novelists are professional novelists, thus make a living wage, living writing novels and other fiction, while othe ...

, editor

Editing is the process of selecting and preparing written, photographic, visual, audible, or cinematic material used by a person or an entity to convey a message or information. The editing process can involve correction, condensation, ...

and religious thinker, one of the major figures in Russian symbolism

Russian symbolism was an intellectual and artistic movement predominant at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. It arose separately from European symbolism, emphasizing mysticism and ostranenie.

Literature

Influences

Primary ...

. The story of her marriage to Dmitry Merezhkovsky

Dmitry Sergeyevich Merezhkovsky ( rus, Дми́трий Серге́евич Мережко́вский, p=ˈdmʲitrʲɪj sʲɪrˈɡʲejɪvʲɪtɕ mʲɪrʲɪˈʂkofskʲɪj; – December 9, 1941) was a Russian novelist, poet, religious thinker ...

, which lasted 52 years, is described in her unfinished book ''Dmitry Merezhkovsky'' (Paris, 1951; Moscow, 1991).

She began writing at an early age, and by the time she met Dmitry Merezhkovsky in 1888, she was already a published poet. The two were married in 1889. Gippius published her first book of poetry, '' Collection of Poems. 1889–1903'', in 1903, and her second collection, '' Collection of Poems. Book 2. 1903-1909'', in 1910. After the 1905 Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

, the Merezhkovskys became critics of Tsarism; they spent several years abroad during this time, including trips for treatment of health issues. They denounced the 1917 October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

, seeing it as a cultural disaster, and in 1919 emigrated to Poland.

After living in Poland they moved to France, and then to Italy, continuing to publish and take part in Russian émigré circles, though Gippius's harsh literary criticism made enemies. The tragedy of the exiled Russian writer was a major topic for Gippius in emigration, but she also continued to explore mystical and covertly sexual themes, publishing short stories, plays, novels, poetry, and memoirs. The death of Merezhkovsky in 1941 was a major blow to Gippius, who died a few years later in 1945.

Biography

Zinaida Gippius was born on , inBelyov

Belyov (russian: Белёв) is a town and the administrative center of Belyovsky District in Tula Oblast, Russia, located on the left bank of the Oka River. Population: 13,180 (2018);

History

As is the case with many other towns in the former ...

, Tula

Tula may refer to:

Geography

Antarctica

*Tula Mountains

* Tula Point

India

* Tulā, a solar month in the traditional Indian calendar

Iran

*Tula, Iran, a village in Hormozgan Province

Italy

*Tula, Sardinia, municipality (''comune'') in the pr ...

, the eldest of four sisters. Her father, Nikolai Romanovich Gippius, a respected lawyer and a senior officer in the Russian Senate, was a German-Russian, whose ancestor Adolphus von Gingst, later von Hippius, came to settle in Moscow in the 16th century. Her mother, Anastasia Vasilyevna ( Stepanova), was a daughter of the Yekaterinburg

Yekaterinburg ( ; rus, Екатеринбург, p=jɪkətʲɪrʲɪnˈburk), alternatively romanized as Ekaterinburg and formerly known as Sverdlovsk ( rus, Свердло́вск, , svʲɪrˈdlofsk, 1924–1991), is a city and the administrat ...

Chief of Police.

Nikolai Gippius's job entailed constant traveling, and because of this his daughters received little formal education. Taking lessons from governesses and visiting tutors, they attended schools sporadically in whatever city (Saratov

Saratov (, ; rus, Сара́тов, a=Ru-Saratov.ogg, p=sɐˈratəf) is the largest city and administrative center of Saratov Oblast, Russia, and a major port on the Volga River upstream (north) of Volgograd. Saratov had a population of 901 ...

, Tula

Tula may refer to:

Geography

Antarctica

*Tula Mountains

* Tula Point

India

* Tulā, a solar month in the traditional Indian calendar

Iran

*Tula, Iran, a village in Hormozgan Province

Italy

*Tula, Sardinia, municipality (''comune'') in the pr ...

and Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

, among others) the family happened to stay for a significant period of time. At the age of 48 Nikolai Gippius died of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in w ...

, and Anastasia Vasilyevna, knowing that all of her girls had inherited a predisposition to the illness that killed him, moved the family southwards, first to Yalta

Yalta (: Я́лта) is a resort city on the south coast of the Crimean Peninsula surrounded by the Black Sea. It serves as the administrative center of Yalta Municipality, one of the regions within Crimea. Yalta, along with the rest of Cri ...

(where Zinaida had medical treatment) then in 1885 to Tiflis

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), is the capital and the largest city of Georgia, lying on the banks of the Kura River with a population of approximately 1.5 million p ...

, closer to their uncle Alexander Stepanov's home.

By this time, Zinaida had already studied for two years at a girls' school in Kiev (1877—1878) and for a year at the Moscow Fischer Gymnasium. It was only in Borzhomi where her uncle Alexander, a man of considerable means, rented a dacha

A dacha ( rus, дача, p=ˈdatɕə, a=ru-dacha.ogg) is a seasonal or year-round second home, often located in the exurbs of post-Soviet countries, including Russia. A cottage (, ') or shack serving as a family's main or only home, or an out ...

for her, that she started to get back to normal after the profound shock caused by her beloved father's death.

Zinaida started writing poetry at the age of seven. By the time she met Dmitry Merezhkovsky in 1888, she was already a published poet. "By the year 1880 I was writing verses, being a great believer in 'inspiration', and making it a point never to take my pen away from paper. People around me saw these poems as a sign of my being 'spoiled', but I never tried to conceal them and, of course, I wasn't spoiled at all, what with my religious upbringing," she wrote in 1902 in a letter to Valery Bryusov

Valery Yakovlevich Bryusov ( rus, Вале́рий Я́ковлевич Брю́сов, p=vɐˈlʲerʲɪj ˈjakəvlʲɪvʲɪdʑ ˈbrʲusəf, a=Valyeriy Yakovlyevich Bryusov.ru.vorb.oga; – 9 October 1924) was a Russian poet, prose writer, drama ...

. A good-looking girl, Zinaida attracted a lot of attention in Borzhomi, but Merezhkovsky, a well-educated introvert, impressed her first and foremost as a perfect kindred spirit. Once he proposed, she accepted him without hesitation, and never came to regret what might have seemed a hasty decision.

Gippius and Merezhkovsky were married on 8 January 1889, in Tiflis. They had a short honeymoon tour involving a stay in the Crimea, then returned to Saint Petersburg and moved into a flat in the Muruzi House, which Merezhkovsky's mother had rented and furnished for them as a wedding gift.

Literary career

Merezhkovsky and Gippius made a pact, each promising to concentrate on what he or she did best, the former on poetry, the latter on prose. The agreement collapsed as Zinaida translated

Merezhkovsky and Gippius made a pact, each promising to concentrate on what he or she did best, the former on poetry, the latter on prose. The agreement collapsed as Zinaida translated Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and Peerage of the United Kingdom, peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and h ...

's ''Manfred

''Manfred: A dramatic poem'' is a closet drama written in 1816–1817 by Lord Byron. It contains supernatural elements, in keeping with the popularity of the ghost story in England at the time. It is a typical example of a Gothic fiction.

Byr ...

'', and Dimitry started working on his debut novel ''Julian the Apostate''. In Saint Petersburg Gippius joined the Russian Literary Society, became a member of the Shakespearean Circle (the celebrity lawyer Prince Alexander Urusov being its most famous member), and met and befriended Yakov Polonsky

Yakov Petrovich Polonsky (russian: Яков Петрович Полонский; ) was a leading Pushkinist poet who tried to uphold the waning traditions of Russian Romantic poetry during the heyday of realistic prose.

Of noble birth, Polonsky ...

, Apollon Maykov

Apollon Nikolayevich Maykov (russian: Аполло́н Никола́евич Ма́йков, , Moscow – , Saint Petersburg) was a Russian poet, best known for his lyric verse showcasing images of Russian villages, nature, and history. His love ...

, Dmitry Grigorovich

Dmitry Vasilyevich Grigorovich (russian: Дми́трий Васи́льевич Григоро́вич) ( – ) was a Russian writer, best known for his first two novels, '' The Village'' and '' Anton Goremyka'', and lauded as the first author ...

, Aleksey Pleshcheyev and Pyotr Veinberg. She became close to the group of authors associated with the renovated '' Severny Vestnik'', where she herself made her major debut as a poet in 1888.

In 1890–91 this magazine published her first short stories, "The Ill-Fated One" and "In Moscow". Then three of her novels, ''Without the Talisman'', ''The Winner'', and ''Small Waves'', appeared in '' Mir Bozhy''. Seeing the writing of mediocre, generic prose as a commercial enterprise, Gippius treated her poetry differently, as something utterly intimate, calling her verses 'personal prayers'. Dealing with the darker side of the human soul and exploring sexual ambiguity and narcissism

Narcissism is a self-centered personality style characterized as having an excessive interest in one's physical appearance or image and an excessive preoccupation with one's own needs, often at the expense of others.

Narcissism exists on a co ...

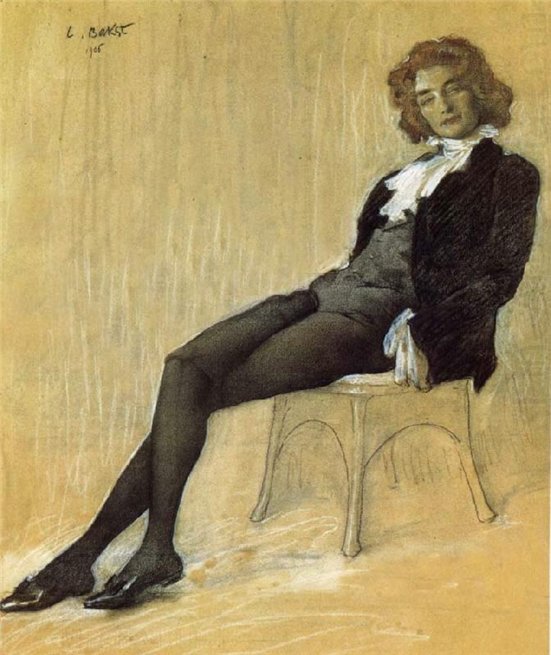

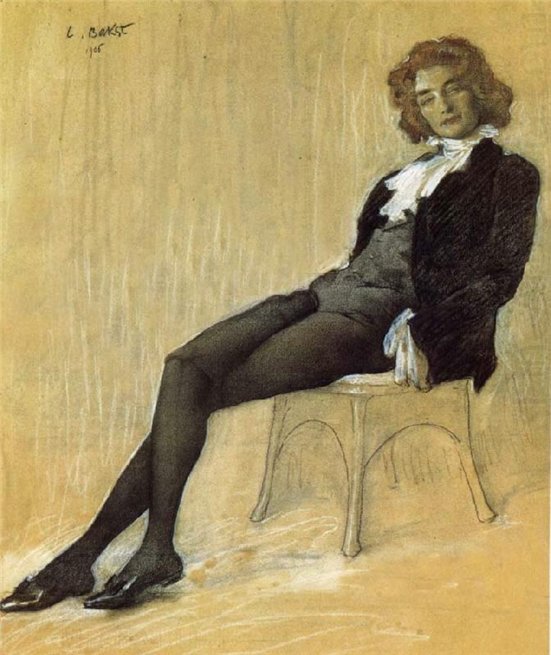

, many of those 'prayers' were considered blasphemous at the time. Detractors called Gippius a 'demoness', the 'queen of duality', and a 'decadent Madonna'. Enjoying the notoriety, she exploited her androgynous image, used male clothes and pseudonyms, shocked her guests with insults ('to watch their reaction', as she once explained to Nadezhda Teffi), and for a decade remained the Russian symbol of 'sexual liberation', holding high what she in one of her diary entries termed as the 'cross of sensuality'. In 1901 all this transformed into the ideology of the "New Church" of which she was the instigator.

In October 1903 the '' Collection of Poems. 1889–1903'', Gippius's first book of poetry, came out; Innokenty Annensky

Innokenty Fyodorovich Annensky ( rus, Инноке́нтий Фёдорович А́нненский, p=ɪnɐˈkʲenʲtʲɪj ˈfʲɵdərəvʲɪtɕ ˈanʲɪnskʲɪj, a=Innokyentiy Fyodorovich Annyenskiy.ru.vorb.oga; (1 September O.S. 20 August">Ol ...

later called the book the "quintessence of fifteen years of Russian modernism." Valery Bryusov

Valery Yakovlevich Bryusov ( rus, Вале́рий Я́ковлевич Брю́сов, p=vɐˈlʲerʲɪj ˈjakəvlʲɪvʲɪdʑ ˈbrʲusəf, a=Valyeriy Yakovlyevich Bryusov.ru.vorb.oga; – 9 October 1924) was a Russian poet, prose writer, drama ...

was greatly impressed too, praising the "insurmountable frankness with which she document dthe emotional progress of her enslaved soul." Gippius herself never thought much of the social significance of her published poetry. In a foreword to her debut collection she wrote: "It is sad to realize that one had to produce something as useless and meaningless as this book. Not that I think poetry to be useless; on the contrary, I am convinced that it is essential, natural and timeless. There were times when poetry was read everywhere and appreciated by everybody. But those times are gone. A modern reader has no use for a book of poetry any more."

In the early 1900s the Muruzi House acquired the reputation of being one of the Russian capital's new cultural centers. Guests recognized and admired the hostess's authority and her talent for leadership, even if none of them found her particularly warm or affectionate.

The New Church

In 1899—1901, encouraged by the group of authors associated with ''

In 1899—1901, encouraged by the group of authors associated with ''Mir Iskusstva

''Mir iskusstva'' ( rus, «Мир искусства», p=ˈmʲir ɪˈskustvə, ''World of Art'') was a Russian magazine and the artistic movement it inspired and embodied, which was a major influence on the Russians who helped revolutionize Eu ...

'', the magazine she had become close to, Gippius published critical essays in it using male pseudonyms, Anton Krainy being the best known. Analyzing the roots of the crisis that Russian culture had fallen into, Gippius (somewhat paradoxically, given her 'demonic' reputation) suggested as a remedy the 'Christianization' of it, which in practice meant bringing the intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

and the Church closer together. Merging faith and intellect, according to Gippius, was crucial for the survival of Russia; only religious ideas, she thought, would bring its people enlightenment and liberation, both sexual and spiritual.

In 1901 Gippius and Merezhkovsky co-founded the Religious and Philosophical Meetings. This 'gathering for free discussion', focusing on the synthesis of culture and religion, brought together an eclectic mix of intellectuals and was regarded in retrospect as an important, if short-lived attempt to pull Russia back from the major social upheavals it was headed for. Gippius was the driving force behind the Meetings, as well as the magazine '' Novy Put'' (1903–04), launched initially as a vehicle for the former. By the time ''Novy Put'' folded (due to a conflict caused by the newcomer Sergei Bulgakov

Sergei Nikolaevich Bulgakov (; russian: Серге́й Никола́евич Булга́ков; – 13 July 1944) was a Russian Orthodox theologian, priest, philosopher, and economist.

Biography

Early life: 1871–1898

Sergei Nikolaevich Bul ...

's refusal to publish her essay on Alexander Blok

Alexander Alexandrovich Blok ( rus, Алекса́ндр Алекса́ндрович Бло́к, p=ɐlʲɪˈksandr ɐlʲɪˈksandrəvʲɪtɕ ˈblok, a=Ru-Alyeksandr Alyeksandrovich Blok.oga; 7 August 1921) was a Russian lyrical poet, writer, publ ...

), Gippius (as Anton Krainy) had become a prominent literary critic, contributing mostly to ''Vesy

''Vesy'' (russian: Весы́; en, The Balance or The Scales) was a Russian symbolist magazine published in Moscow from 1904 to 1909, with the financial backing of philanthropist S. A. Polyakov. It was edited by the major symbolist writer Valery ...

'' (Scales).

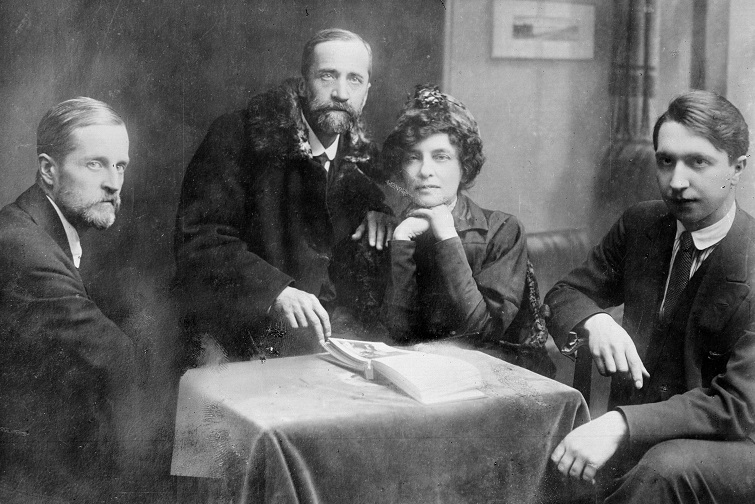

After the Meetings were closed in 1903, Gippius tried to revive her initial idea in the form of what was regarded as her 'domestic Church', based on the controversial Troyebratstvo (Brotherhood of Three), composed of herself, Merezhkovsky, and Dmitry Filosofov, their mutual close friend and, for a short while, her lover. This new development outraged many of their friends, like Nikolai Berdyaev

Nikolai Alexandrovich Berdyaev (; russian: Никола́й Алекса́ндрович Бердя́ев; – 24 March 1948) was a Russian philosopher, theologian, and Christian existentialist who emphasized the existential spiritual si ...

who saw this bizarre parody on the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the ...

, with its own set of quasi-religious rituals, as profanation bordering on blasphemy.

1905–1917

The

The 1905 Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

had a profound impact on Gippius. During the next decade the Merezhkovskys were harsh critics of Tsarism

Tsarist autocracy (russian: царское самодержавие, transcr. ''tsarskoye samoderzhaviye''), also called Tsarism, was a form of autocracy (later absolute monarchy) specific to the Grand Duchy of Moscow and its successor states th ...

, radical revolutionaries like Boris Savinkov

Boris Viktorovich Savinkov (Russian: Бори́с Ви́кторович Са́винков; 31 January 1879 – 7 May 1925) was a Russian writer and revolutionary. As one of the leaders of the Fighting Organisation, the paramilitary wing ...

now entering their narrow circle of close friends. In February 1906 the couple left for France to spend more than two years in what they saw as self-imposed exile, trying to introduce Western intellectuals to their 'new religious consciousness'. In 1906 Gippius published the collection of short stories ''Scarlet Sword'' (Алый меч), and in 1908 the play ''Poppie Blossom'' (Маков цвет) came out, with Merezhkovsky and Filosofov credited as co-authors.

Disappointed with the indifference of European cultural elites to their ideas, the trio returned home. Back in Saint Petersburg Gippius's health deteriorated, and for the next six years she (along with her husband, who had heart problems) regularly visited European health resorts and clinics. During one such voyage in 1911 Gippius bought a cheap apartment in Paris, at Rue Colonel Bonnet, 11-bis. What at the time felt like a casual, unnecessary purchase, later saved them from homelessness abroad.

As the political tension in Russia subsided, the Meetings were re-opened as the Religious and Philosophical Society, in 1908. But Russian Church leaders ignored it, and soon the project withered into a mere literary circle. The heated discussion over the ''Vekhi

Vekhi ( rus, Вехи, p=ˈvʲexʲɪ, t=Landmarks) is a collection of seven essays published in Russia in 1909. It was distributed in five editions and elicited over two hundred published rejoinders in two years. The volume reappraising the Russian ...

'' manifesto led to a clash between the Merezhkovskys and Filosofov on the one hand and Vasily Rozanov

Vasily Vasilievich Rozanov (russian: Васи́лий Васи́льевич Рóзанов; – 5 February 1919) was one of the most controversial Russian writers and important philosophers in the symbolists' of the pre- revolutionary epoc ...

on the other; the latter quit and severed ties with his old friends.

By the time her '' Collection of Poems. Book 2. 1903-1909'' came out in 1910, Gippius had become a well-known (though by no means as famous as her husband) European author, translated into German and French. In 1912 her book of short stories ''Moon Ants'' (Лунные муравьи) came out, featuring the best prose she had written in years. The two novels, ''The Demon Dolls'' (Чортовы куклы, 1911) and ''Roman-Tsarevich'' (Роман-царевич, 1912), were meant to be the first and the third book of the Hieromonk

A hieromonk ( el, Ἱερομόναχος, Ieromonachos; ka, მღვდელმონაზონი, tr; Slavonic: ''Ieromonakh'', ro, Ieromonah), also called a priestmonk, is a monk who is also a priest in the Eastern Orthodox Church and ...

Iliodor

Sergei Michailovich Trufanov ( Russian: Серге́й Миха́йлович Труфа́нов; formerly Hieromonk Iliodor or Hieromonk Heliodorus, russian: Иеромонах Илиодор; October 19, 1880 – 28 January 1952) was a lapsed hi ...

trilogy, which remained unfinished. The literary left panned them as allegedly 'anti-revolutionary', mainstream critics found these books lackluster, formulaic and tendentious.

At the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, the Merezhkovskys spoke out against Russia's involvement. Still, Gippius launched a support-the-soldiers campaign of her own, producing a series of frontline-forwarded letters, each combining stylized folk poetic messages with small tobacco-packets, signed with either her own, or one of her three servant maids' names. Some dismissed it as pretentious and meaningless, others applauded what they saw as her reaction to the jingoistic hysteria of the time.

1917–1919

The Merezhkovskys greeted the 1917 February Revolution and denounced theOctober Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

, blaming Alexander Kerensky

Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky, ; original spelling: ( – 11 June 1970) was a Russian lawyer and revolutionary who led the Russian Provisional Government and the short-lived Russian Republic for three months from late July to early Novembe ...

and his Provisional government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or f ...

for the catastrophe. In her book of memoirs ''Dmitry Merezhkovsky. Him and Us'' Gippius wrote:

Rostov

Rostov ( rus, Росто́в, p=rɐˈstof) is a town in Yaroslavl Oblast, Russia, one of the oldest in the country and a tourist center of the Golden Ring. It is located on the shores of Lake Nero, northeast of Moscow. Population:

While ...

teenager cadet

A cadet is an officer trainee or candidate. The term is frequently used to refer to those training to become an officer in the military, often a person who is a junior trainee. Its meaning may vary between countries which can include youths in ...

s shot down — for being mistakenly taken for Constitutional Democratic Party

)

, newspaper = '' Rech''

, ideology = Constitutionalism Constitutional monarchismLiberal democracy Parliamentarism Political pluralismSocial liberalism

, position = Centre to centre-left

, international =

, colo ...

cadets, the banned ones." — 17 March), of mass hunger and her own growing feeling of dull indifference. "Those who still have a soul in them walk around like corpses: neither protesting, nor suffering, waiting for nothing, bodies and souls slumped into hunger-induced dormancy."

Expressing some sympathy for 'the weeping Lunacharsky' (the only Bolshevik leader to express at least some regret concerning the cruelties of the repressive organs), Gippius wrote: "The things that happen now have nothing to do with Russian history. They will be forgotten, like the atrocities of some savages on a faraway island; will vanish without a trace." ''Last Poems (1914–1918)'', published in 1918, presented a stark and gloomy picture of revolutionary Russia as Gippius saw it. After the defeats of Alexander Kolchak

Alexander Vasilyevich Kolchak (russian: link=no, Александр Васильевич Колчак; – 7 February 1920) was an Imperial Russian admiral, military leader and polar explorer who served in the Imperial Russian Navy and fough ...

in Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part o ...

and Anton Denikin

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (russian: Анто́н Ива́нович Дени́кин, link= ; 16 December O.S. 4 December">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 December1872 – 7 August 19 ...

in Southern Russia

Southern Russia or the South of Russia (russian: Юг России, ''Yug Rossii'') is a colloquial term for the southernmost geographic portion of European Russia generally covering the Southern Federal District and the North Caucasian Federal ...

, respectively, the Merezhkovskys moved to Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. In late 1919, invited to join a group of 'red professors' in Crimea, Gippius chose not to, having heard of massacres orchestrated by local chiefs Béla Kun

Béla Kun (born Béla Kohn; 20 February 1886 – 29 August 1938) was a Hungarian communist revolutionary and politician who governed the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919. After attending Franz Joseph University at Kolozsvár (today Cluj-Na ...

and Rosalia Zemlyachka. Having obtained permission to leave the city (the pretext being that they would head for the frontlines, with lectures on Ancient Egypt for Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

fighters), Merezhkovsky and Gippius, as well as her secretary Vladimir Zlobin and Dmitry Filosofov, departed to Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, , is a country in Central Europe. Poland is divided into Voivodeships of Poland, sixteen voivodeships and is the fifth most populous member state of the European Union (EU), with over 38 mill ...

by train.

Gippius in exile

Their first destination was

Their first destination was Minsk

Minsk ( be, Мінск ; russian: Минск) is the capital and the largest city of Belarus, located on the Svislach (Berezina), Svislach and the now subterranean Nyamiha, Niamiha rivers. As the capital, Minsk has a special administrative stat ...

where Merezhkovsky and Gippius gave a series of lectures for Russian immigrants and published political pamphlets in the ''Minsk Courier''. During a stay of several months in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is official ...

Gippius edited the ''Svoboda'' newspaper. Disillusioned with Jozef Pilsudski

Jozef or Józef is a Dutch, Breton, Polish and Slovak version of masculine given name Joseph. A selection of people with that name follows. For a comprehensive list see and ..

* Józef Beck (1894–1944), Polish foreign minister in the 1930s ...

's policies, the Merezhkovskys and Zlobin left for France on 20 October without Filosofov, who chose to stay in the city with Boris Savinkov. The Merezhkovskys's relocation to France was facilitated by Olga and Eugene Petit, who also helped them secure entry and residence permit for their friends such as Ivan Manukhin.

In Paris Gippius concentrated on making appointments, sorting out mail, negotiating contracts and receiving guests. The Merezhkovsky's talks, as Nina Berberova remembered, always revolved around two major themes: Russia and freedom. Backing Merezhkovsky in his anti-Bolshevik crusade, she was deeply pessimistic as regards what her husband referred to as his 'mission'. "Our slavery is so unheard of and our revelations are so outlandish that for a free man it is difficult to understand what we are talking about," she conceded.

The tragedy of the exiled Russian writer became a major topic for Gippius in emigration, but she also continued to explore mystical

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in u ...

and covertly sexual themes. She remained a harsh literary critic and, by dismissing many of the well-known writers of the Symbolist and Acmeist camps, made herself an unpopular figure in France.

In the early 1920s several of Gippius's earlier works were re-issued in the West, including the collection of stories ''Heavenly Words'' (Небесные слова, 1921, Paris) and the ''Poems. 1911–1912 Diary'' (1922, Berlin). In Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and Ha ...

''The Kingdom of Antichrist'' (Царство Антихриста), authored by Merezhkovsky, Gippius, Filosofov, and Zlobin, came out, including the first two parts of Gippius's ''Petersburg Diaries'' (Петербургские дневники). Gippius was the major force behind the ''Green Lamp'' (Зелёная лампа) society, named after the 19th century group associated with Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin (; rus, links=no, Александр Сергеевич ПушкинIn pre-Revolutionary script, his name was written ., r=Aleksandr Sergeyevich Pushkin, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈpuʂkʲɪn, ...

. Factional altercations aside, it proved to be the only cultural center where Russian émigré writers and philosophers (carefully chosen for each meeting and invited personally) could meet and discuss political and cultural topics.

In 1928 the Merezhkovskys took part in the First Congress of Russian writers in exile held in Belgrade. Encouraged by the success of Merezhkovsky's Da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested on hi ...

series of lectures and Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

's benevolence, in 1933 the couple moved to Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

where they stayed for about three years, visiting Paris only occasionally. With the Socialist movement rising there and anti-Russian emigration feelings spurred by President Paul Doumer

Joseph Athanase Doumer, commonly known as Paul Doumer (; 22 March 18577 May 1932), was the President of France from 13 June 1931 until his assassination on 7 May 1932.

Biography

Joseph Athanase Doumer was born in Aurillac, in the Cantal ''dépa ...

's murder in 1932, France felt like a hostile place to them. Living in exile was very hard for Gippius psychologically. As one biographer put it, "her metaphysically grandiose personality, with its spiritual and intellectual overload, was out of place in what she herself saw as a 'soullessly pragmatic' period in European history."

The last years

As the outbreak ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

in Europe rendered literature virtually irrelevant, Gippius, against all odds, compiled and published the ''Literature Tornado'', an ambitious literary project set up to provide a safe haven for writers rejected by publishers for ideological reasons. What in other times might have been hailed as a powerful act in support of the freedom of speech, in 1939 passed unnoticed. Merezhkovsky and Gippius spent their last year together in a social vacuum. Regardless of whether or not the 1944 text of Merezhkovsky's allegedly pro-Hitler "Radio speech" was indeed a prefabricated montage (as his biographer Zobnin asserted), there was little doubt that the couple, having become too close to (and financially dependent on) the Germans in Paris, had lost respect and credibility as far as their compatriots were concerned, many of whom expressed outright hatred toward them.

Merezhkovsky's death in 1941 came as a heavy blow to Gippius. After the deaths of Dmitry Filosofov and her sister Anna (in 1940 and 1942 respectively) she found herself alone in the world and, as some sources suggest, contemplated suicide. With her secretary Vladimir Zlobin still around, though, Gippius resorted to writing what she hoped would some day gel into the comprehensive life story of her late husband. As Teffi remembered,

Gippius died on 9 September 1945. Her last written words were: "Low is my price.... And wise is God." She was interred in Sainte-Genevieve-des-Bois Russian Cemetery with her husband. A small group of people attended the ceremony, among them Ivan Bunin

Ivan Alekseyevich Bunin ( or ; rus, Ива́н Алексе́евич Бу́нин, p=ɪˈvan ɐlʲɪˈksʲejɪvʲɪtɕ ˈbunʲɪn, a=Ivan Alyeksyeyevich Bunin.ru.vorb.oga; – 8 November 1953) was the first Russian writer awarded the ...

.

Legacy

Modern scholars see Gippius's romantically tinged early poems as mostly derivative, Semyon Nadson and

Modern scholars see Gippius's romantically tinged early poems as mostly derivative, Semyon Nadson and Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his c ...

being the two most obvious influences. The publication of Dmitry Merezhkovsky's symbolist manifesto proved to be a turning point: in a short time Gippius became a major figure of Russian Modernism. Her early symbolist prose carried the strong influence of Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (, ; rus, Фёдор Михайлович Достоевский, Fyódor Mikháylovich Dostoyévskiy, p=ˈfʲɵdər mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ dəstɐˈjefskʲɪj, a=ru-Dostoevsky.ogg, links=yes; 11 November 18219 ...

, while one of her later novels, ''Roman Tzarevich'' (1912), was said to be influenced again by Nietzsche. Gippius's first two short story collections, ''New People'' (1896) and ''Mirrors'' (1898), examining "the nature of beauty in all of its manifestations and contradictions," were seen as formulaic. Her ''Third Book of Short Stories'' (1902) marked a change of direction and was described as "sickly idiosyncratic" and full of "highbrow mysticism." Parallels have been drawn between Gippius's early 20th century prose and Vladimir Solovyov's ''Meaning of Love'', both authors examining the 'quest for love' as the means for self-fulfillment of the human soul.

It was not prose but poetry that made Gippius a major innovative force. "Gippius the poet holds her own special place in Russian literature; her poems are deeply intellectual, immaculate in form, and genuinely exciting." Critics praised her originality and technical virtuosity, claiming her to be a "true heir to Yevgeny Baratynsky

Yevgeny Abramovich Baratynsky (russian: Евге́ний Абра́мович Бараты́нский, p=jɪvˈɡʲenʲɪj ɐˈbraməvʲɪtɕ bərɐˈtɨnskʲɪj, a=Yevgyeniy Abramovich Baratynskiy.ru.vorb.oga; 11 July 1844) was lauded by Alexan ...

's muse".

Her '' Collection of Poems. 1889–1903'' became an important event in Russian cultural life. Having defined the world of poetry as a three-dimensional structure involving "Love and Eternity meeting in Death", she discovered and explored in it her own brand of ethic and aesthetic minimalism. Symbolist writers were the first to praise her 'hint and pause' metaphor technique, as well as the art of "extracting sonorous chords out of silent pianos," according to Innokenty Annensky

Innokenty Fyodorovich Annensky ( rus, Инноке́нтий Фёдорович А́нненский, p=ɪnɐˈkʲenʲtʲɪj ˈfʲɵdərəvʲɪtɕ ˈanʲɪnskʲɪj, a=Innokyentiy Fyodorovich Annyenskiy.ru.vorb.oga; (1 September O.S. 20 August">Ol ...

, who saw the book as the artistic peak of "Russia's 15 years of modernism" and argued that "not a single man would ever be able to dress abstractions in clothes of such charm s this woman" Men admired Gippius's outspokenness too: Gippius commented on her inner conflicts, full of 'demonic temptations' (inevitable for a poet whose mission was 'creating a new, true soul', as she put it), with unusual frankness.

The 1906 collection ''Scarlet Sword'', described as a study in the 'human soul's metaphysics' performed from the neo-Christian standpoint, propagated the idea of God and man as one single being. The author equated 'self-denial' with the sin of betraying God, and detractors suspected blasphemy in this egocentric stance. Sex and death themes, investigated in the obliquely impressionist manner formed the leitmotif of her next book of prose, ''Black on White'' (1908). The 20th century also saw the rise of Gippius the playwright (''Saintly Blood'', 1900, ''Poppie Blossom'', 1908). The most acclaimed of her plays, ''The Green Ring'' (1916), futuristic in plotline, if not in form, was successfully produced by Vsevolod Meyerhold

Vsevolod Emilyevich Meyerhold (russian: Всеволод Эмильевич Мейерхольд, translit=Vsévolod Èmíl'evič Mejerchól'd; born german: Karl Kasimir Theodor Meyerhold; 2 February 1940) was a Russian and Soviet theatre ...

for the Alexandrinsky Theatre

The Alexandrinsky Theatre (russian: Александринский театр) or National Drama Theatre of Russia is a theatre in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

The Alexandrinsky Theatre was built for the Imperial troupe of Petersburg (Imperial t ...

. Anton Krainy, Gippius's alter ego, was a highly respected and somewhat feared literary critic whose articles regularly appeared in ''Novy Put'', ''Vesy'' and '' Russkaya Mysl''. Gippius's critical analysis, according to Brockhaus and Efron, was insightful, but occasionally too harsh and rarely objective.

The 1910 '' Collection of Poems. Book 2. 1903-1909'' garnered good reviews; Bunin called Gippius's poetry 'electric', pointing at the peculiar use of oxymoron

An oxymoron (usual plural oxymorons, more rarely oxymora) is a figure of speech that juxtaposes concepts with opposing meanings within a word or phrase that creates an ostensible self-contradiction. An oxymoron can be used as a rhetorical dev ...

as an electrifying force in the author's hermetic, impassive world. Some contemporaries found Gippius's works curiously unfeminine. Vladislav Khodasevich

Vladislav Felitsianovich Khodasevich (russian: Владисла́в Фелициа́нович Ходасе́вич; 16 May 1886 – 14 June 1939) was an influential Russian poet and literary critic who presided over the Berlin circle of Russian e ...

spoke of the conflict between her "poetic soul and non-poetic mind." "Everything is strong and spatial in her verse, there is little room for details. Her lively, sharp thought, dressed in emotional complexity, sort of rushes out of her poems, looking for spiritual wholesomeness and ideal harmony," modern scholar Vitaly Orlov said.

Gippius's novels ''The Devil's Doll'' (1911) and ''Roman Tzarevich'' (1912), aiming to "lay bare the roots of Russian reactionary ideas," were unsuccessful: critics found them tendentious and artistically inferior. "In poetry Gippius is more original than in prose. Well constructed, full of intriguing ideas, never short of insight, her stories and novellas are always a bit too preposterous, stiff and uninspired, showing little knowledge of real life. Gippius's characters pronounce interesting words and find themselves in interestingly difficult situations but fail to turn into living people in the reader's mind. Serving as embodiments of ideas and concepts, they are genuinely crafted marionettes put into action by the author's hand, not by their own inner motives."

The events of October 1917 led to Gippius severing all ties with most of those who admired her poetry, including Blok, Bryusov and Bely. The history of this schism and the reconstruction of the ideological collisions that made such a catastrophe possible became the subject matter of her memoirs ''The Living Faces'' (Живые лица, 1925). While Blok (the man whom she famously refused her hand in 1918) saw the Revolution as a 'purifying storm', Gippius was appalled by the 'suffocating dourness' of the whole thing, seeing it as one huge monstrosity "leaving one with just one wish: to go blind and deaf." Behind all this, for Gippius, there was a kind of 'monumental madness'; it was all the more important for her to keep a "healthy mind and strong memory," she explained.

After ''Last Poems'' (1918) Gippius published two more books of verse, ''Poems. 1911–1920 Diaries'' (1922) and ''The Shining Ones'' (1938). Her poetry, prose and essays published in emigration were utterly pessimistic; the 'rule of beastliness', the ruins of human culture, and the demise of civilization were her major themes. Most valuable for Gippius were her diaries: she saw these flash points of personal history as essential for helping future generations to restore the true course of events. Yet, as a modern Russian critic has put it, "Gippius's legacy, for all its inner drama and antinomy, its passionate, forceful longing for the unfathomable, has always borne the ray of hope, the fiery, unquenchable belief in a higher truth and the ultimate harmony crowning a person's destiny. As she herself wrote in one of her last poems, "Alas, now they are torn apart: the timelessness and all things human / But time will come and both will intertwine into one shimmering eternity'."

On November 20, 2019, Google

Google LLC () is an American Multinational corporation, multinational technology company focusing on Search Engine, search engine technology, online advertising, cloud computing, software, computer software, quantum computing, e-commerce, ar ...

celebrated her 150th birthday with a Google Doodle

A Google Doodle is a special, temporary alteration of the logo on Google's homepages intended to commemorate holidays, events, achievements, and notable historical figures. The first Google Doodle honored the 1998 edition of the long-running ...

.

Selected bibliography

Poetry

* '' Collection of Poems. 1889–1903'' (Собрание стихов. 1889–1903) * '' Collection of Poems. Book 2. 1903-1909'' (Собрание стихов. Книга 2, 1910) * ''The Last Poems (1914–1918)'' * ''Poems. 1911–1912 Diary'' (1922, Berlin). * ''Poems. 1911–1920 Diaries'' (1922) * ''The Shining Ones'' (1938, poetry collection)Prose

* ''New People'' (1896, short stories) * ''Mirrors'' (1898, short stories) * ''The Third Book of Short Stories'' (1902) * ''Scarlet Sword'' (1906, short stories) * ''Black on White'' (1908, short stories) * ''Moon Ants'' (1912, short stories) * ''The Devil's Doll'' (1911, novel) * ''Roman-Tzarevich'' (1912, novel) * ''Words from the Heavens'' (1921, Paris, short stories)Drama

* ''Sacred Blood'' (1900, play) * ''Poppie Blossom'' (1908, play) * '' The Green Ring'' (1916, play)Non-fiction

* ''The Living Faces'' (1925, memoirs)English translations

* ''Apple Blossom'', (story), from ''Russian Short Stories'', Senate, 1995. * ''The Green Ring'', (play), C.W. Daniel LTD, London, 1920. * ''Poems'', ''Outside of Time: an Old Etude'' (story), and ''They are All Alike'' (story), from ''A Russian Cultural Revival'', University of Tennessee Press, 1981.References

External links

English translations of 3 poems by Babette Deutsch and Avrahm Yarmolinsky, 1921

* ttp://stihipoeta.ru/poety-serebryanogo-veka/zinaida-gippius/ Zinaida Gippius poetrya

Stihipoeta.ru

(play) from archive.org * {{DEFAULTSORT:Gippius, Zinaida 1869 births 1945 deaths People from Tula Oblast People from Belyovsky Uyezd Russian people of German descent Women writers from the Russian Empire Russian religious leaders Symbolist poets Russian editors Russian women editors Russian dramatists and playwrights Russian women short story writers Russian women poets Russian women dramatists and playwrights 20th-century Russian poets 20th-century Russian women writers 20th-century Russian short story writers Emigrants from the Russian Empire to France Burials at Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois Russian Cemetery