Yugoslav Democratic National Union on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Ba Congress, also known as the Saint Sava Congress () or Great People's Congress, was a meeting of representatives of

The Ba Congress, also known as the Saint Sava Congress () or Great People's Congress, was a meeting of representatives of

In April 1941, the

In April 1941, the

By mid-1943, Mihailović had realised that he needed to broaden the political appeal of the Chetnik movement. Reverses in Montenegro and Herzegovina had shown that the Chetnik political ideology was producing unsatisfactory results with the populace, and the Western Allies were concerned that the Chetnik movement was anti-democratic, or possibly even

By mid-1943, Mihailović had realised that he needed to broaden the political appeal of the Chetnik movement. Reverses in Montenegro and Herzegovina had shown that the Chetnik political ideology was producing unsatisfactory results with the populace, and the Western Allies were concerned that the Chetnik movement was anti-democratic, or possibly even  When it was finally held, the Ba Congress, also known as the Saint Sava Congress or Great People's Congress, was conducted in the shadow of two threats, which affected both the Chetniks and the leaders of the political parties in pre-war Yugoslavia who now supported them. The first of these was that the Partisans had widened their appeal by advancing the idea of unity among Yugoslav peoples as free and equal members of the country. This had attracted many people to their cause. This approach was formalised by the resolution of the Second Session of the

When it was finally held, the Ba Congress, also known as the Saint Sava Congress or Great People's Congress, was conducted in the shadow of two threats, which affected both the Chetniks and the leaders of the political parties in pre-war Yugoslavia who now supported them. The first of these was that the Partisans had widened their appeal by advancing the idea of unity among Yugoslav peoples as free and equal members of the country. This had attracted many people to their cause. This approach was formalised by the resolution of the Second Session of the

The congress was also attended by

The congress was also attended by

By agreeing to the resolutions of the congress, the Chetnik leadership sought to undermine Partisan accusations that they were dedicated to a return to pre-war Serb hegemony and a Greater Serbia. Tomasevich observes that in asserting the need to gather all Serbs into a single entity, ''The Serbian Goals of the Ravna Gora Movement'' was reminiscent of ''

By agreeing to the resolutions of the congress, the Chetnik leadership sought to undermine Partisan accusations that they were dedicated to a return to pre-war Serb hegemony and a Greater Serbia. Tomasevich observes that in asserting the need to gather all Serbs into a single entity, ''The Serbian Goals of the Ravna Gora Movement'' was reminiscent of ''

Having not attended the congress, the British had no first-hand intelligence about the discussions. Only in April did the SOE contact Musulin and ask for a report. Having received it, the British were hesitant to accept the new political program on its face value. Assessing that Mihailović's situation was increasingly desperate, they were not keen to enable a late attempt to save what they already thought was a lost cause. Topalović later acknowledged that the congress was not as "imposing nor as grand as its own propaganda and the publicity given to it by its friends made it appear to be". In May, the British mission to Mihailović was withdrawn. The following month, Mihailović was dropped as a minister in the Yugoslav government-in-exile, removing his legitimacy. From this point, he treated the government-in-exile as his enemy, and had to go on alone.

The Germans were very interested in the congress, and German agents provided a detailed account of it to the Higher SS and Police Leader in the German-occupied territory of Serbia, SS- and ,

Having not attended the congress, the British had no first-hand intelligence about the discussions. Only in April did the SOE contact Musulin and ask for a report. Having received it, the British were hesitant to accept the new political program on its face value. Assessing that Mihailović's situation was increasingly desperate, they were not keen to enable a late attempt to save what they already thought was a lost cause. Topalović later acknowledged that the congress was not as "imposing nor as grand as its own propaganda and the publicity given to it by its friends made it appear to be". In May, the British mission to Mihailović was withdrawn. The following month, Mihailović was dropped as a minister in the Yugoslav government-in-exile, removing his legitimacy. From this point, he treated the government-in-exile as his enemy, and had to go on alone.

The Germans were very interested in the congress, and German agents provided a detailed account of it to the Higher SS and Police Leader in the German-occupied territory of Serbia, SS- and ,  The central committee of the JDNZ had been selected by June, consisting of six members, one each for foreign affairs, legislative affairs, economic and fiscal affairs, nationality questions and propaganda, social affairs, and economic construction. The central committee condemned the new government-in-exile led by

The central committee of the JDNZ had been selected by June, consisting of six members, one each for foreign affairs, legislative affairs, economic and fiscal affairs, nationality questions and propaganda, social affairs, and economic construction. The central committee condemned the new government-in-exile led by

The Ba Congress, also known as the Saint Sava Congress () or Great People's Congress, was a meeting of representatives of

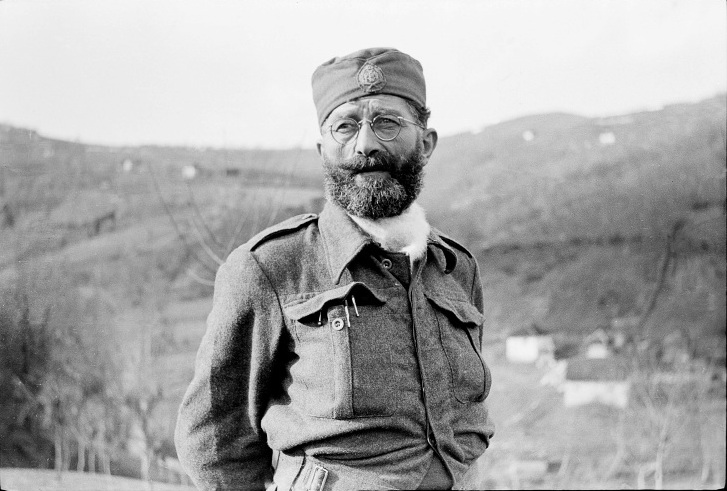

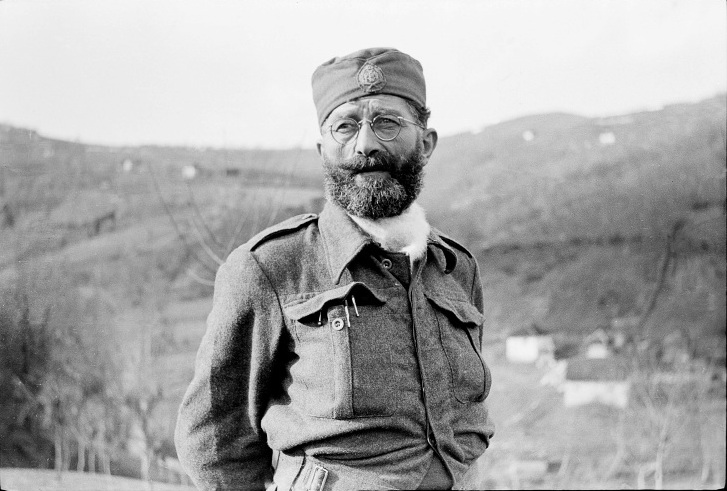

The Ba Congress, also known as the Saint Sava Congress () or Great People's Congress, was a meeting of representatives of Draža Mihailović

Dragoljub "Draža" Mihailović ( sr-Cyrl, Драгољуб Дража Михаиловић; 27 April 1893 – 17 July 1946) was a Yugoslavs, Yugoslav Serb general during World War II. He was the leader of the Chetniks, Chetnik Detachments ...

's Chetnik

The Chetniks ( sh-Cyrl-Latn, Четници, Četnici, ; sl, Četniki), formally the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army, and also the Yugoslav Army in the Homeland and the Ravna Gora Movement, was a Yugoslav royalist and Serbian nationa ...

movement held between 25 and 28 January 1944 in the village of Ba in the German-occupied territory of Serbia

The Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia (german: Gebiet des Militärbefehlshabers in Serbien; sr, Подручје Војног заповедника у Србији, Područje vojnog zapovednika u Srbiji) was the area of the Kin ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. It sought to provide a political alternative to the plans for post-war Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

set out by the Chetniks' rivals, the communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

-led Yugoslav Partisans

The Yugoslav Partisans,Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian, Slovene: , or the National Liberation Army, sh-Latn-Cyrl, Narodnooslobodilačka vojska (NOV), Народноослободилачка војска (НОВ); mk, Народноослобод ...

, and attempted to reverse the decision of the major Allied powers to provide their exclusive support to the Yugoslav Partisans while withdrawing their support of the Chetniks.

The Partisan plan had been set out in the November 1943 Second Session of the communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

-led Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia

The Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia,, mk, Антифашистичко собрание за народно ослободување на Југославија commonly abbreviated as the AVNOJ, was a deliberat ...

(AVNOJ). While the Chetnik movement and Mihailović had been working towards a return to the Serb-dominated, monarchist Yugoslavia of the interwar period, AVNOJ had resolved that post-war Yugoslavia would be a federal republic with six equal, constituent republics, and denied the right of King Peter II to return from exile before a popular referendum to determine the future of his rule. AVNOJ had further asserted that it was the sole legitimate government of Yugoslavia.

By the time of the Ba Congress, large parts of the Chetnik movement had been drawn into collaboration

Collaboration (from Latin ''com-'' "with" + ''laborare'' "to labor", "to work") is the process of two or more people, entities or organizations working together to complete a task or achieve a goal. Collaboration is similar to cooperation. Most ...

with the occupying forces. The British, who had primacy regarding Allied policy in Yugoslavia, had originally supported the Chetniks, but, by December 1943, had concluded that the Chetniks were more interested in collaborating with the Axis against the Partisans than in fighting the Axis. As a test, they asked Mihailović to attack two specific bridges on the Belgrade-to-Salonika railway line, which never happened. At the Tehran Conference

The Tehran Conference (codenamed Eureka) was a strategy meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill from 28 November to 1 December 1943, after the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. It was held in the Soviet Union's embassy i ...

of NovemberDecember 1943, the major Allies agreed to change support to the Partisans. However, the Partisans had not gained entry to the German-occupied territory of Serbia, and combined with a November armistice the Chetniks had with the Germans (and likely with their tacit support for the congress), the Chetniks planned the Ba Congress as a political gesture aimed at addressing the resolutions of AVNOJ, providing an alternative political vision for post-war Yugoslavia, and as a means of changing the minds of the Allies – but particularly the US – about the decisions of the Tehran Conference that withdrew support for the Chetnik movement.

The congress opened on 25 January 1944, with the pre-war leader of the small Socialist Party

Socialist Party is the name of many different political parties around the world. All of these parties claim to uphold some form of socialism, though they may have very different interpretations of what "socialism" means. Statistically, most of th ...

, Živko Topalović Živko Topalović (21 March 1886 in Užice – 11 February 1972 in Vienna) was a Yugoslav socialist politician. Topalović became a leading figure in the Socialist Party of Yugoslavia, founded in 1921.Banac, Ivo. The National Question in Yugos ...

, as its chairman. The congress denounced the AVNOJ as "the work of the Ustasha-Communist minority", continuing an existing propaganda campaign which claimed that the Partisans and Ustashas had united to exterminate the Serbs. It also provided its full support to King Peter II and the Yugoslav government-in-exile

The Government of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in Exile ( sh, Vlada Kraljevine Jugoslavije u egzilu / Влада Краљевине Југославије у егзилу) was an official government of Yugoslavia, headed by King Peter II. It evacu ...

, and re-asserted the Chetnik movement's opposition to the Germans and their allies. It further resolved to mobilise all anti-communist Serbs to fight for the survival of Serbdom

Serbian nationalism asserts that Serbs are a nation and promotes the cultural and political unity of Serbs. It is an ethnic nationalism, originally arising in the context of the general rise of nationalism in the Balkans under Ottoman rule, und ...

. It founded a new political party, the Yugoslav Democratic National Union (JDNZ), in an effort to unite all the elements of the Chetnik movement. Lastly, it proposed its own vision for the political and socio-economic future of Yugoslavia. This political framework included a Serb sovereign and a tripartite federal state, with entities for the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes only, with the Serb unit being dominant, much in the style of the Serbian nationalist

Serbian nationalism asserts that Serbs are a nation and promotes the cultural and political unity of Serbs. It is an ethnic nationalism, originally arising in the context of the general rise of nationalism in the Balkans under Ottoman rule, und ...

and irredentist

Irredentism is usually understood as a desire that one state annexes a territory of a neighboring state. This desire is motivated by ethnic reasons (because the population of the territory is ethnically similar to the population of the parent sta ...

idea of Greater Serbia

The term Greater Serbia or Great Serbia ( sr, Велика Србија, Velika Srbija) describes the Serbian nationalist and irredentist ideology of the creation of a Serb state which would incorporate all regions of traditional significance to S ...

. However, while the congress resulted in a short period of reduced collaboration with the Germans and the forces of the puppet

A puppet is an object, often resembling a human, animal or Legendary creature, mythical figure, that is animated or manipulated by a person called a puppeteer. The puppeteer uses movements of their hands, arms, or control devices such as rods ...

Government of National Salvation

The Government of National Salvation ( sr, Влада народног спаса, Vlada narodnog spasa, (VNS); german: Regierung der nationalen Rettung), also referred to as Nedić's government (, ) and Nedić's regime (, ), was the colloquial na ...

in the German-occupied territory of Serbia, at this stage of the war, and with the change in Allied policy towards the Chetniks, there was nothing that could be done to improve the position of the movement. Mihailović was dropped as a minister of the government-in-exile soon after, and the Chetnik situation continued to deteriorate, with their continuing tentative collaboration with the Germans playing into the hands of Partisans.

Background

In April 1941, the

In April 1941, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Kraljevina Jugoslavija, Краљевина Југославија; sl, Kraljevina Jugoslavija) was a state in Southeast Europe, Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 unt ...

was drawn into World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

when Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and its allies invaded and occupied the country, which was then partitioned. Some Yugoslav territory was annexed

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

by its Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

*Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinate ...

neighbours: Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

, Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

. The Germans engineered and supported the creation of the Independent State of Croatia

The Independent State of Croatia ( sh, Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH; german: Unabhängiger Staat Kroatien; it, Stato indipendente di Croazia) was a World War II-era puppet state of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Fascist It ...

( hr, Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH), a puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a State (polity), state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside Power (international relations), power and subject to its o ...

led by the fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

Ustaša – Croatian Revolutionary Movement. The NDH comprised all of modern-day Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

and Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of south and southeast Europe, located in the Balkans. Bosnia and H ...

and some adjacent territory. Before the defeat, King Peter II and his government went into exile, reforming in June as the Western Allied

The Allies, formally referred to as the Declaration by United Nations, United Nations from 1942, were an international Coalition#Military, military coalition formed during the World War II, Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis ...

-recognised Yugoslav government-in-exile

The Government of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in Exile ( sh, Vlada Kraljevine Jugoslavije u egzilu / Влада Краљевине Југославије у егзилу) was an official government of Yugoslavia, headed by King Peter II. It evacu ...

in London.

Two resistance movements soon emerged in occupied Yugoslavia: the almost exclusively ethnic Serb

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian ancestry, culture, history and language.

The majority of Serbs live in their na ...

and monarchist Chetniks

The Chetniks ( sh-Cyrl-Latn, Четници, Četnici, ; sl, Četniki), formally the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army, and also the Yugoslav Army in the Homeland and the Ravna Gora Movement, was a Yugoslav royalist and Serbian nationa ...

, led by Draža Mihailović

Dragoljub "Draža" Mihailović ( sr-Cyrl, Драгољуб Дража Михаиловић; 27 April 1893 – 17 July 1946) was a Yugoslavs, Yugoslav Serb general during World War II. He was the leader of the Chetniks, Chetnik Detachments ...

; and the multi-ethnic and communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

-led Partisans, under Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito (; sh-Cyrl, Тито, links=no, ), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman, serving in various positions from 1943 until his deat ...

. The approaches of the two resistance movements differed in important respects from the beginning. The Chetniks under Mihailović advocated a "wait-and-see" strategy of building up an organisation for a struggle which was to commence when the Western Allies arrived in Yugoslavia, thereby limiting losses in military and civilian personnel alike until the final phase of the war. On the other hand, the Partisans were implacably opposed to the Axis occupation and resisted consistently from the beginning. The Chetnik political agenda was a return to the Serb-dominated Yugoslavia of the interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the World War I, First World War to the beginning of the World War II, Second World War. The in ...

, whereas the Partisans strove to create a social revolution in a multi-ethnic but communist-dominated Yugoslavia. During the early years of the war, the Chetniks failed to articulate or promote a strong political agenda. According to the historian and political scientist Kirk Ford, it is possible that Mihailović believed that he did not need to do so, as he had been a representative of the government-in-exile since January 1942.

In different parts of the country the Chetnik movement was progressively drawn into collaboration

Collaboration (from Latin ''com-'' "with" + ''laborare'' "to labor", "to work") is the process of two or more people, entities or organizations working together to complete a task or achieve a goal. Collaboration is similar to cooperation. Most ...

agreements. First, with the forces of the puppet Government of National Salvation

The Government of National Salvation ( sr, Влада народног спаса, Vlada narodnog spasa, (VNS); german: Regierung der nationalen Rettung), also referred to as Nedić's government (, ) and Nedić's regime (, ), was the colloquial na ...

in the German-occupied territory of Serbia

The Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia (german: Gebiet des Militärbefehlshabers in Serbien; sr, Подручје Војног заповедника у Србији, Područje vojnog zapovednika u Srbiji) was the area of the Kin ...

, then with the Italians in occupied Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

and Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = M ...

, next with some of the Ustasha forces in the northern Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of south and southeast Europe, located in the Balkans. Bosnia and He ...

region of the NDH, and, after the Italian capitulation

The Armistice of Cassibile was an armistice signed on 3 September 1943 and made public on 8 September between the Kingdom of Italy and the Allies during World War II.

It was signed by Major General Walter Bedell Smith for the Allies and Brig ...

in September 1943, with the Germans directly. On 29 October 1943, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

authorised German headquarters to utilise "national anti-Communist forces" to fight insurgencies in southeastern Europe. By the end of the year, due to a drift towards collaboration, the Government of National Salvation and the Germans were at least as influential over the Chetnik movement in the German-occupied territory of Serbia as Mihailović, who was becoming increasingly isolated.

Prelude

By mid-1943, Mihailović had realised that he needed to broaden the political appeal of the Chetnik movement. Reverses in Montenegro and Herzegovina had shown that the Chetnik political ideology was producing unsatisfactory results with the populace, and the Western Allies were concerned that the Chetnik movement was anti-democratic, or possibly even

By mid-1943, Mihailović had realised that he needed to broaden the political appeal of the Chetnik movement. Reverses in Montenegro and Herzegovina had shown that the Chetnik political ideology was producing unsatisfactory results with the populace, and the Western Allies were concerned that the Chetnik movement was anti-democratic, or possibly even fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

. The veneer of democracy advanced by the Partisans was appealing to the Western Allies, and Mihailović was concerned that the support he was receiving would shift to them. In order to widen the base of the Chetnik movement, Mihailović contacted representatives of the pre-war political parties living in Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; Names of European cities in different languages: B, names in other languages) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers a ...

. He assured them that the former illiberal approach of the movement, as advocated by his close political advisers, the former republican and Black Hand

Black Hand or The Black Hand may refer to:

Extortionists and underground groups

* Black Hand (anarchism) (''La Mano Negra''), a presumed secret, anarchist organization based in the Andalusian region of Spain during the early 1880s

* Black Hand (e ...

adherent Dragiša Vasić and the Chetnik ideologue Stevan Moljević

Stevan Moljević (6 January 1888 – 15 November 1959) was a Yugoslav and Serbian politician, lawyer and publicist, president of the Yugoslav-French Club, president of the Yugoslav-British Club, president of Rotary International Club of Yugosla ...

, had been replaced with a commitment to democracy. The politicians responded to Mihailović's approach positively as they were concerned about the outcome of the war, and neither a communist nor Chetnik military dictatorship appealed to them.

According to the historian Lucien Karchmar, the politician that appears to have taken the primary role in these negotiations was the leader of the small pre-war Socialist Party

Socialist Party is the name of many different political parties around the world. All of these parties claim to uphold some form of socialism, though they may have very different interpretations of what "socialism" means. Statistically, most of th ...

, Živko Topalović Živko Topalović (21 March 1886 in Užice – 11 February 1972 in Vienna) was a Yugoslav socialist politician. Topalović became a leading figure in the Socialist Party of Yugoslavia, founded in 1921.Banac, Ivo. The National Question in Yugos ...

. Topalović contacted members of the pre-war United Opposition, such as the leader of the Independent Democratic Party, Adam Pribićević, and the leader of the People's Radical Party

The People's Radical Party ( sr, Народна радикална странка, Narodna radikalna stranka, abbr. НРС or NRS) was the dominant ruling party of Kingdom of Serbia and later Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes from the la ...

, Aca Stanojević

Aleksa "Aca" Stanojević (Knjaževac, Principality of Serbia, 1852 - SFR Yugoslavia, 1947) was a Serbian and Yugoslav politician, one of the founders and leaders of the People's Radical Party.

Stanojević was a member of the People's Radical Part ...

. Both Pribićević and Stanojević were only the nominal leaders of their respective parties, as the real decision-makers in their parties were with the government-in-exile in London. The political parties agreed that they would negotiate with Mihailović as a group. Each party nominated two delegates to a coordinating council, and the council selected four negotiators, led by Topalović, who were to work out the details of an agreement with the Chetnik leader. These negotiations dragged on, and there was one break of two months between discussions. On the Chetnik side, Moljević and his supporters suggested that the politicians join the Chetnik movement, which they considered apolitical, but the politicians refused to be absorbed in this way. Instead, they demanded a new political grouping be formed, of which the Chetnik movement would be just one part, and that this new grouping would lay out a new program for the future. Further demands were for a reaffirmation of the Yugoslav idea, a parliamentary system and social reforms, a federally organised country, improved relationships with the British, and a new attempt at reconciliation with the Partisans, preferably with the help of the Allies.

Some of Mihailović's followers were against agreeing to the politicians' demands. Nevertheless the Chetnik leader accepted them, but with the proviso that the politicians firmly commit to the agreement. The politicians were loath to do this, as if they signed any document it could be used against them by the Germans, forcing them to leave Belgrade and join Mihailović in the field. The next step was a proposal to convoke a congress to ratify the new political structure and announce the new program. Mihailović advanced the date of 1 December, which was the anniversary of the founding of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

(Kingdom of Yugoslavia since 1929) in 1918, but the politicians delayed the preparations as they continued to negotiate and hesitate.

When it was finally held, the Ba Congress, also known as the Saint Sava Congress or Great People's Congress, was conducted in the shadow of two threats, which affected both the Chetniks and the leaders of the political parties in pre-war Yugoslavia who now supported them. The first of these was that the Partisans had widened their appeal by advancing the idea of unity among Yugoslav peoples as free and equal members of the country. This had attracted many people to their cause. This approach was formalised by the resolution of the Second Session of the

When it was finally held, the Ba Congress, also known as the Saint Sava Congress or Great People's Congress, was conducted in the shadow of two threats, which affected both the Chetniks and the leaders of the political parties in pre-war Yugoslavia who now supported them. The first of these was that the Partisans had widened their appeal by advancing the idea of unity among Yugoslav peoples as free and equal members of the country. This had attracted many people to their cause. This approach was formalised by the resolution of the Second Session of the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia

The Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia,, mk, Антифашистичко собрание за народно ослободување на Југославија commonly abbreviated as the AVNOJ, was a deliberat ...

( sh, Antifašističko vijeće narodnog oslobođenja Jugoslavije, AVNOJ) in the Bosnian town of Jajce

Jajce (Јајце) is a town and municipality located in the Central Bosnia Canton of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. According to the 2013 census, the town has a population of 7,172 inhabitants, with ...

in November 1943, which decided to create a federal Yugoslavia, based on six constituent republics with equal rights, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of south and southeast Europe, located in the Balkans. Bosnia and H ...

, Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

, Macedonia, Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = M ...

, Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

, and Slovenia

Slovenia ( ; sl, Slovenija ), officially the Republic of Slovenia (Slovene: , abbr.: ''RS''), is a country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the southeast, an ...

. Along with this resolution, AVNOJ asserted that it was the sole legitimate government of Yugoslavia, and denied the right of King Peter to return from exile before a popular referendum to determine the future of his rule. The Western Allies expressed no opposition to the resolutions of AVNOJ, and at the Tehran Conference

The Tehran Conference (codenamed Eureka) was a strategy meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill from 28 November to 1 December 1943, after the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. It was held in the Soviet Union's embassy i ...

of 28 November to 1 December, the Allies had agreed to throw their support behind the Partisans.

The second threat to the Chetniks and their political allies was the fact that from mid-1943, the British, who had primacy regarding Allied policy in Yugoslavia, had begun to doubt their decision to support Mihailović. By December they had concluded that Mihailović's Chetniks were more interested in collaborating with the Axis against the Partisans than in fighting the Axis. On 8 December 1943, in the wake of the Tehran Conference decision, the British Commander-in-Chief of the Middle East, General Henry Maitland Wilson

Field Marshal Henry Maitland Wilson, 1st Baron Wilson, (5 September 1881 – 31 December 1964), also known as Jumbo Wilson, was a senior British Army officer of the 20th century. He saw active service in the Second Boer War and then during the ...

, had sent a message to Mihailović asking him to attack two specific bridges on the Belgrade to Salonika

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

railway line. This message was a test formulated by the British to assess Mihailović's intentions regarding resisting the Germans, and was done with the expectation that he would continue his inactivity against the Germans and not comply. The chief of the British Special Operations Executive

The Special Operations Executive (SOE) was a secret British World War II organisation. It was officially formed on 22 July 1940 under Minister of Economic Warfare Hugh Dalton, from the amalgamation of three existing secret organisations. Its pu ...

(SOE) mission to the Chetniks, Brigadier

Brigadier is a military rank, the seniority of which depends on the country. In some countries, it is a senior rank above colonel, equivalent to a brigadier general or commodore, typically commanding a brigade of several thousand soldiers. In ...

Charles Armstrong, followed this up with written orders on 16 December, directing Mihailović to carry out the sabotage on the two bridges by 29 December. The attacks were never carried out.

In late 1943, the Partisans, who had enjoyed considerable success in the rest of Yugoslavia in the wake of the September capitulation of the Italians, had been stymied in an attempt to break into the German-occupied territory of Serbia from the neighbouring occupied territories of Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = M ...

, Sandžak

Sandžak (; sh, / , ; sq, Sanxhaku; ota, سنجاق, Sancak), also known as Sanjak, is a historical geo-political region in Serbia and Montenegro. The name Sandžak derives from the Sanjak of Novi Pazar, a former Ottoman administrative dis ...

and eastern Bosnia. The German-led operation that stopped the Partisan incursion, Operation Kugelblitz

Operation Kugelblitz ("ball lightning") was a major anti-Partisan offensive orchestrated by German forces in December 1943 during World War II in Yugoslavia. The Germans attacked Josip Broz Tito's Partisan forces in the eastern parts of the Indep ...

, included Bulgarian and collaborating Chetnik units. While unsuccessful in destroying the targeted Partisan formations, it did delay their entry into Serbian territory. The Chetniks took advantage of this respite, bolstered by the relative protection afforded by armistice agreements they had made with the Germans in November. This situation allowed the Chetniks to convoke the Ba Congress as a striking political gesture aimed at addressing the resolutions of AVNOJ and providing an alternative political vision for post-war Yugoslavia. It was also conceived as a means of changing the minds of the Allies – but particularly the US – about the decisions of the Tehran Conference that withdrew support for the Chetnik movement. Another aim was to broaden political support for the movement through a program that, while remaining fiercely anti-communist, had enough democratic elements to have widespread support among the population.

Participants

The congress was organised by Mihailović and occurred between 25 and 28 January 1944 in the village of Ba, nearValjevo

Valjevo (Serbian Cyrillic: Ваљево, ) is a List of cities in Serbia, city and the administrative center of the Kolubara District in western Serbia. According to the 2011 census, the administrative area of Valjevo had 90,312 inhabitants, 59,07 ...

in the German-occupied territory of Serbia. Approximately 300 civilians participated, almost all of whom were Serbs from Serbia, Montenegro and Bosnia together with two or three Croats, one Slovene and one Bosnian Muslim. The non-Serb representation was effectively tokenistic. Delegates from Herzegovina

Herzegovina ( or ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, Hercegovina, separator=" / ", Херцеговина, ) is the southern and smaller of two main geographical region of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the other being Bosnia. It has never had strictly defined geogra ...

and Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

were unable to attend in time. The delegates attending included principal Chetnik commanders, politicians who had joined the Chetnik cause at the beginning, such as Vasić and Moljević, representatives of old Serb political parties who had decided to join with the Chetniks later on and others. The politicians included Topalović and Pribićević. Virtually all of the pre-war political parties were represented in some way, excluding the communists and fascist-aligned groups. The congress was unique during the war, in that it was the only gathering which included the main Chetnik commanders and closely aligned politicians as well as Chetnik supporters among the pre-war political parties.

The Chetnik old guard were originally opposed to the involvement of the recently aligned pre-war politicians, and according to Mihailović they were only included at his insistence. Mihailović was also opposed to Vasić having a significant role in the congress, because he and Vasić were now regularly on opposing sides in discussions. Vasić was only included at Topalović's urging. A significant number of the younger Chetnik leaders considered the pre-war politicians to be of poor quality and character, and obstacles to political, social and economic reforms after the war. Given that the Germans could easily have prevented it from occurring or disrupted it once underway, it has been argued by the historians Jozo Tomasevich

Josip "Jozo" Tomasevich (March 16, 1908 – October 15, 1994; hr, Josip Jozo Tomašević) was an American economist and military historian. He was professor emeritus at San Francisco State University.

Education and career

Tomašević was born ...

and Marko Attila Hoare

Marko Attila Hoare (born 1972) is a British historian of the former Yugoslavia who also writes about current affairs, especially Southeast Europe, including Turkey and the Caucasus.

Biography

Hoare is the son of the British translator Quintin ...

that the congress was held with the tacit approval of the Germans.

The congress was also attended by

The congress was also attended by Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

George Musulin

George "Guv" S. Musulin (April 9, 1914 – February 23, 1987) was an American army officer of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) who in 1950 became a CIA operative.

Early life

George Musulin was born into a Serbian family in New York City an ...

, one of the American Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the intelligence agency of the United States during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines for all branc ...

(OSS) officers attached to the British mission to Mihailović, largely at his own initiative. He was the only Allied representative who attended. Armstrong refused to participate in the congress because of the Chetnik failure to carry out the sabotage operations ordered by Wilson and himself. British Prime Minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern p ...

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

used Mihailović's refusal as an opportunity to tell King Peter about the Tehran Conference decision that the Allies would be backing Tito exclusively, and that Mihailović might have to be dismissed as a minister in the government-in-exile.

Discussions

The night before the congress, Moljević and the long-term Chetnik supporters verbally clashed with Topalović and the politicians, but Mihailović decided in favour of the latter. Mihailović made a personal address to the congress, pledging his loyalty to the king, to the rule of law and to Yugoslavia, and repeatedly denied he had any tendencies towards dictatorship. He also rejected the idea of taking collective revenge against any nationality or political faction for crimes committed during the war. He forcefully refused to join the drift into collaboration with the Germans affecting much of the Chetnik movement at the time of the congress, but his repeated denials about plans for a military dictatorship indicate an understandable lack of confidence from the politicians in this regard. Mihailović was not overtly involved in the following discussions. During the congress there were frequent anti-German outbursts from congress participants. In common with political practice under the period of royal dictatorship from 1929, the congress formed a new political party, the Yugoslav Democratic National Union ( sh, Jugoslavenska demokratska narodna zajednica, link=no, JDNZ), and Topalović was appointed as its chairman. Despite the very small size of the Socialist Party before the war, Topalović was apparently chosen due to his links with two Labour Party members of theChurchill war ministry

The Churchill war ministry was the United Kingdom's coalition government for most of the Second World War from 10 May 1940 to 23 May 1945. It was led by Winston Churchill, who was appointed Prime Minister by King George VI following the resig ...

, Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

and Ernest Bevin

Ernest Bevin (9 March 1881 – 14 April 1951) was a British statesman, trade union leader, and Labour Party politician. He co-founded and served as General Secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers' Union in the years 1922–19 ...

. The committee established for the new party included a large number of Serbs and Montenegrins, as well as three Croats – Vladimir Predavec, Đuro Vilović, and Niko Bartulović

Niko Bartulović (23 December 1890 – 1945) was an Austrian and later Yugoslav writer, publisher, journalist and translator known for being one of the founders and ideologists of the Organization of Yugoslav Nationalists in 1921. He joined the C ...

. It also included a Slovenian refugee, Anton Krejći, and a Bosnian Muslim, Mustafa Mulalić. Among the non-Serbs, only Mulalić was a pre-war politician, from the Yugoslav National Party

The Yugoslav National Party ( sh, Jugoslavenska nacionalna stranka, Југославенска национална странка, JNS; sl, Jugoslovanska nacionalna stranka), established as Yugoslav Radical Peasants' Democracy ( sh, Jugoslavensk ...

. Topalović's election was a victory for the moderates among the delegates, and constituted a setback for the Greater Serbia

The term Greater Serbia or Great Serbia ( sr, Велика Србија, Velika Srbija) describes the Serbian nationalist and irredentist ideology of the creation of a Serb state which would incorporate all regions of traditional significance to S ...

extremists such as Vasić and Moljević, who had dominated the Chetnik political program up to this point.

Views on the character of the congress varied between those with long-standing ties to the Chetnik movement, and those pre-war politicians that had only recently come to support it. Both groups believed they had an equal stake in the future of Yugoslavia. The Chetniks saw the JDNZ as the expanded political wing of Mihailović's movement, with Mihailović to retain all military and political power, whereas Topalović saw the Chetniks as the military arm under the primacy of the new party. It quickly became clear that the two sides could not easily agree on even procedural matters, let alone on final resolutions. Moljević was also opposed to the creation of the JDNZ, and only wanted an expansion of the existing Chetnik Central Committee, of which he was a long-standing member. During the congress, the assembled representatives sent a message of solidarity to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

and Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

. Despite the close relationship between the Partisans and the Soviets, this message is explained by the fact that neither the Chetniks nor the government-in-exile had taken an anti-Soviet stance during the war, and Mihailović also thought that the approaching Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

would appreciate assistance from the Chetniks in forcing the Germans from the occupied territory of Serbia.

Resolutions

After three days of debate, the congress made resolutions regarding both military and political matters. Firstly, it denounced the decisions of AVNOJ as "the work of the Ustasha-Communist minority", in accordance with the existing Chetnik propaganda that the Partisans and the Ustashas had united to exterminate Serbs. It also provided its full support to the Yugoslav government-in-exile, the Chetniks, and Mihailović's military leadership, claiming that Mihailović's Chetniks were a truly national army. It re-asserted the Chetnik movement's opposition to Germany and its allies, and resolved to mobilise all anti-communist Serbs to fight for the survival ofSerbdom

Serbian nationalism asserts that Serbs are a nation and promotes the cultural and political unity of Serbs. It is an ethnic nationalism, originally arising in the context of the general rise of nationalism in the Balkans under Ottoman rule, und ...

. Lastly, it proposed its own vision for the political and socio-economic future of Yugoslavia.

The congress denounced AVNOJ's change to the constitutional organization of Yugoslavia, called on the Partisans to abandon political actions until the end of the war, and adopted a high-minded but somewhat imprecise resolution known as the Ba Resolution ( sh, Baška rezolucija, links=no). The principal document was called ''The Goals of the Ravna Gora Movement'' and came in two parts. "Ravna Gora Movement" in the title referred to Ravna Gora, the place where Mihailović's Chetniks first established themselves after the invasion, and is an alternative name for Mihailović's Chetnik movement. The first part, ''The Yugoslav Goals of the Ravna Gora Movement'' stated that:

* a restored and enlarged Yugoslavia would be a national state of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes;: Draža Mihailović, .... saziva predstavnike bivših građanskih stranaka iz Srbije, Crne Gore i Slovenije, pojedine jugonacionaliste iz Hrvatske te neke javne radnike na četnički kongres u selu Ba, pod padinama Suvobora. ... je proklamirana ideja ustavne i trijalističke monarhije (s prevlašću Srbije, dakako) kao protuteža proklamiranom federativnom uređenju u Jajcu. [Draža Mihailović,... convened representatives of former civil parties from Serbia, Montenegro and Slovenia, some Yugoslav nationalists from Croatia, and some public workers at the Chetnik Congress in the village of Ba, under the slopes of Suvobor... the idea of the constitutional and triune monarchy (under Serbian hegemony, of course) is proclaimed as a counterweight to the proclaimed federal arrangement in Jajce.]* national minorities who were enemies of Yugoslavia and the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes would be expelled from Yugoslav territory; * Yugoslavia would be organised on a democratic basis as a federation consisting of three units, Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia; and * all three peoples of Yugoslavia would organise their own internal affairs as their representatives chose. The second part, ''The Serbian Goals of the Ravna Gora Movement'' stated that all Serbian provinces would be united in the Serbian unit within the federal arrangement, based on the solidarity between all Serb regions of Yugoslavia, under a

unicameral

Unicameralism (from ''uni''- "one" + Latin ''camera'' "chamber") is a type of legislature, which consists of one house or assembly, that legislates and votes as one.

Unicameral legislatures exist when there is no widely perceived need for multic ...

parliament. The congress also resolved that Yugoslavia should be a constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

headed by a Serb sovereign. Further, the congress resolved that it would not form a government as AVNOJ had done, and called upon the Partisans to follow a democratic process. Topalović had proposed that Bosnia should be a fourth federal unit, but this was opposed by Vasić and Moljević, because they saw the Bosnian Krajina

Bosanska Krajina ( sr-cyrl, Босанска Крајина, ) is a geographical region, a subregion of Bosnia, in western Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is enclosed by a number of rivers, namely the Sava (north), Glina (northwest), Vrbanja and Vrbas ...

as forming an integral part of the Serbian federal unit.

According to the historians Radovan Samardžić

Radovan Samardžić ( sr-cyr, Радован Самарџић; Sarajevo, 22 October 1922 – Belgrade, 1 February 1994) was a Yugoslav and Serbian historian, member of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (SANU).

He successfully defended his d ...

and Milan Duškov, the main principle of the programme of the Ba Congress was social-democratic Yugoslavism. They claim the resolutions of the Ba Congress were "better founded, culturally and historically" than the framework proposed by AVNOJ. The congress marked a change in the Chetnik main political objective; instead of their earlier aim to restore the centralised pre-war kingdom, they changed their approach towards a federal state structure with a dominant Serb federal unit.

By agreeing to the resolutions of the congress, the Chetnik leadership sought to undermine Partisan accusations that they were dedicated to a return to pre-war Serb hegemony and a Greater Serbia. Tomasevich observes that in asserting the need to gather all Serbs into a single entity, ''The Serbian Goals of the Ravna Gora Movement'' was reminiscent of ''

By agreeing to the resolutions of the congress, the Chetnik leadership sought to undermine Partisan accusations that they were dedicated to a return to pre-war Serb hegemony and a Greater Serbia. Tomasevich observes that in asserting the need to gather all Serbs into a single entity, ''The Serbian Goals of the Ravna Gora Movement'' was reminiscent of ''Homogeneous Serbia

''Homogeneous Serbia'' is a written discourse by Stevan Moljević. In this work, contrary to the presumptions of Ilija Garašanin who believed that the strength of the state is derived from its size and organizational principles, Moljević emph ...

'', written by Moljević several years earlier, which advocated a Greater Serbia. He also notes that the congress did not recognise Macedonia and Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = M ...

as separate nations, and also implied that Croatia and Slovenia would effectively be appendages to the Serbian entity. The net effect of this, according to Tomasevich, was that the country would not only return to the same Serb-dominated state it had been in during the interwar period, but would be worse than that, particularly for the Croats. He concludes that this outcome was to be expected given the overwhelmingly Serb makeup of the congress. Hoare agrees that despite its superficial Yugoslavism, the congress had clear Greater Serbia inclinations, and the historian Lucien Karchmar concludes that the usage of the term "Saint Sava Congress" reinforced the impression that it was focussed on the aspirations of Serbs rather than Yugoslavs in general.

In terms of the socio-economic future of Yugoslavia, the congress expressed an interest in reforming the economic, social, and cultural position of the country, particularly regarding democratic ideals. This was a significant departure from previous Chetnik goals expressed earlier in the war, especially in terms of promoting democratic principles with some socialist features. Tomasevich observes that these new goals were probably more related to achieving propaganda objectives than reflecting actual intentions, given that there was no real interest in considering the needs of the non-Serb peoples of Yugoslavia. It seems unlikely that the Chetnik movement was fully aware of the radicalised mood amongst the general population.

The most important practical outcome of the congress was the creation of the JDNZ, because all of the representatives present agreed to avoid independent political action until conditions in Yugoslavia were normalised. The existing Chetnik Central National Committee was to be expanded to include representatives of all those that participated in the congress. The selection of the new Central National Committee members was delegated to an "organisational committee of three", comprising Topalović, Vasić and Moljević, who were to consult with the various leaders. The outcomes of the congress meant that Mihailović now had the endorsement of the People's Radical Party, the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

, the Independent Democratic Party, the Agrarian Party, the Socialist Party and the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

*Republican Party (Liberia)

* Republican Part ...

. According to Karchmar, claims by Chetnik adherents that this aspect of the Ba Congress demonstrated "overwhelming popular support" for Mihailović are seriously flawed, as they fail to recognise that the pre-war Yugoslav political parties were not mass-membership organisations, and support from the leaders in no way assured support from those that voted for the various parties in the most recent election in 1938. The participants also hoped that the resolutions would restore the Chetnik relationship with the Western Allies, particularly the Churchill government and British public.

Aftermath

Having not attended the congress, the British had no first-hand intelligence about the discussions. Only in April did the SOE contact Musulin and ask for a report. Having received it, the British were hesitant to accept the new political program on its face value. Assessing that Mihailović's situation was increasingly desperate, they were not keen to enable a late attempt to save what they already thought was a lost cause. Topalović later acknowledged that the congress was not as "imposing nor as grand as its own propaganda and the publicity given to it by its friends made it appear to be". In May, the British mission to Mihailović was withdrawn. The following month, Mihailović was dropped as a minister in the Yugoslav government-in-exile, removing his legitimacy. From this point, he treated the government-in-exile as his enemy, and had to go on alone.

The Germans were very interested in the congress, and German agents provided a detailed account of it to the Higher SS and Police Leader in the German-occupied territory of Serbia, SS- and ,

Having not attended the congress, the British had no first-hand intelligence about the discussions. Only in April did the SOE contact Musulin and ask for a report. Having received it, the British were hesitant to accept the new political program on its face value. Assessing that Mihailović's situation was increasingly desperate, they were not keen to enable a late attempt to save what they already thought was a lost cause. Topalović later acknowledged that the congress was not as "imposing nor as grand as its own propaganda and the publicity given to it by its friends made it appear to be". In May, the British mission to Mihailović was withdrawn. The following month, Mihailović was dropped as a minister in the Yugoslav government-in-exile, removing his legitimacy. From this point, he treated the government-in-exile as his enemy, and had to go on alone.

The Germans were very interested in the congress, and German agents provided a detailed account of it to the Higher SS and Police Leader in the German-occupied territory of Serbia, SS- and , August Meyszner

August Edler von Meyszner (3 August 1886 – 24 January 1947) was an Austrian Gendarmerie officer, right-wing politician, and senior ''Ordnungspolizei'' (order police) officer who held the post of Higher SS and Police Leader in the Germ ...

. These reports mentioned the frequent anti-German outbursts that had occurred. The Germans were concerned about the outcomes of the congress, and they may have had some limited consequences in military terms, as the formal armistice agreements between the Germans and Chetniks ended soon after the congress. In practical terms, despite Mihailović's opposition to the slide towards collaboration, co-operation still continued, forced by the deteriorating situation for the Germans and their collaborators in the occupied territory. The congress was followed by a significant deterioration in the relationships between the Chetnik movement and the collaborationist formations of the Government of National Salvation in occupied Serbia, led by Milan Nedić

Milan Nedić ( sr-Cyrl, Милан Недић; 2 September 1878 – 4 February 1946) was a Yugoslav and Serbian army general and politician who served as the chief of the General Staff of the Royal Yugoslav Army and minister of war in the R ...

. The Yugoslav government-in-exile reported at the beginning of March 1944 that in response to the congress, the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one organi ...

and Serbian puppet government arrested 798 people in Belgrade and held them in prison as hostages, threatening to shoot 100 of them for each German soldier killed in Serbia. A number of Mihailović supporters, including some of the politicians, were rounded up by the Germans as part of this sweep, and at least one politician was executed. A number of the politicians who had accepted positions on the new Central National Committee were forced to flee and seek Mihailović's protection.

During the congress, Mihailović mentioned to Musulin that Chetniks had picked up some American aircrew who had crashed near Niš

Niš (; sr-Cyrl, Ниш, ; names in other languages) is the third largest city in Serbia and the administrative center of the Nišava District. It is located in southern part of Serbia. , the city proper has a population of 183,164, while ...

in southeastern Serbia. Musulin saw this as an opportunity to extend his stay with the Chetniks, and once they arrived at Chetnik headquarters, Musulin contacted OSS Cairo to obtain approval to enlist Chetnik assistance to evacuate them from occupied territory. On 6 March, he received approval to take this action. Musulin was supposed to depart on the flight that extracted the aircrew, but delayed his departure due to illness, but also because he wished to stay with the Chetniks and gather intelligence. On 20 May, he asked approval from OSS Cairo to remain, but this was denied, and he was extracted to Italy on 28 May with the rest of the British mission to the Chetniks. A new OSS mission, Operation Halyard

Operation Halyard (or Halyard Mission), known in Serbian as Operation Air Bridge ( sr, Операција Ваздушни мост), was an Allied airlift operation behind Axis lines during World War II. In July 1944, the Office of Strategic Ser ...

, arrived in August to utilise Chetnik assistance in evacuating downed fliers from occupied Serbia. Musulin was initially the leader of the Operation Halyard team.

When he departed in May, Musulin was accompanied by Topalović, who led a diplomatic mission on behalf of Mihailović to try to reverse the Allied decision to abandon the Chetniks. This effort was abortive, as the British did not allow him to leave Italy and would not reconsider their policy of supporting Tito and the Partisans. Topalović was replaced as chairman of the Central National Committee by Mihailo Kujundžić, who had a heart attack and died soon after. He was replaced by Moljević. The new chairman had never reconciled himself with the new political structure, and railed against it, especially as it failed to garner results for the Chetnik movement. There remained a significant gap between those who had embraced the new political structure and those that adhered to the original Chetnik ideology, and this divide was carried over into the post-war émigré

An ''émigré'' () is a person who has emigrated, often with a connotation of political or social self-exile. The word is the past participle of the French ''émigrer'', "to emigrate".

French Huguenots

Many French Huguenots fled France followi ...

diaspora

A diaspora ( ) is a population that is scattered across regions which are separate from its geographic place of origin. Historically, the word was used first in reference to the dispersion of Greeks in the Hellenic world, and later Jews after ...

. Regardless of the return of Moljević to the fold, the pre-war politicians remained in evidence, and came into the field to join Mihailović.

The central committee of the JDNZ had been selected by June, consisting of six members, one each for foreign affairs, legislative affairs, economic and fiscal affairs, nationality questions and propaganda, social affairs, and economic construction. The central committee condemned the new government-in-exile led by

The central committee of the JDNZ had been selected by June, consisting of six members, one each for foreign affairs, legislative affairs, economic and fiscal affairs, nationality questions and propaganda, social affairs, and economic construction. The central committee condemned the new government-in-exile led by Ivan Šubašić

Ivan Šubašić (; 7 May 1892 – 22 March 1955) was a Yugoslav Croat politician, best known as the last Ban of Croatia and prime minister of the royalist Yugoslav Government in exile during the Second World War.

Early life

He was born in Vuk ...

, calling its members communist sympathisers and Croat separatists. It also appointed special representatives for the Chetnik movement overseas, including Konstantin Fotić in the United States, Jovan Đonović in Algiers, Bogoljub Jevtić

Bogoljub Jevtić (Serbian Cyrillic: Богољуб Јевтић; 24 December 1886 – 7 June 1960) was a Serbian diplomat and politician in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

He was plenipotentiary minister of Yugoslavia in Albania, Austria and Hungary. ...

in the UK, General Petar Živković

Petar Živković ( sr-cyr, Петар Живковић; 1 January 1879 – 3 February 1947) was a Serbian military officer and political figure in Yugoslavia. He was Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia from 7 January 1929 until 4 Apr ...

in Italy, and Mladen Žujović

Mladen Žujović (1895—1969) was Serbian and Yugoslav attorney and professor of Law at Belgrade University. He was known as member of British-supported secret society Konspiracija and during the World War II as a member of the Central National ...

in Egypt.

Within the German-occupied territory of Serbia at least, the Chetnik movement took action to implement the resolutions of the congress. Corps commanders were ordered to modify the administrative arrangements in their areas of responsibility, and new "Ravna Gora committees" were established in each district and village to replace the existing administration. New district commanders were appointed, assisted by treasurers and quartermasters. The decrees of the expanded Central National Committee were made binding on all Ravna Gora committees and Chetnik district commanders, and they were only to take orders from the Executive Committee of the Central National Committee, which was also responsible for all propaganda. The Chetniks took over large parts of occupied Serbia outside the towns, pushing the administration of the Nedić government into the margins.

The central committee met again over the period 20–23 July, stating that it considered the Šubašić government incapable of protecting the interests of Yugoslavia and the king, and reserving the right to take whatever actions it considered necessary to look after Yugoslavia's interests. It was clear that Mihailović did not accept his removal from his position as a minister in the government in June. When he was dismissed as chief of staff of the Supreme Command in August, he also did not accept this, and continued to refer to the Chetniks as the "Yugoslav Army in the Homeland", with himself as its chief. The central committee only met twice more between July 1944 and March 1945. In August, several members of the central committee, including Pribićević, Vladimir Belajčić and Ivan Kovač, along with a senior Chetnik commander, Major Zvonimir Vučković, were sent to join Topalović in Italy. Their pleas for a change of policy towards the Chetniks were in vain. Mihailović disestablished the central committee just before he was forced to withdraw from Serbia to northeast Bosnia in mid-September 1944, as he considered that he could only take fighting men with him. Regardless, most of the members of the central committee accompanied him. Eventually, Mihailović and Moljević fell out over the relationship of the Chetnik movement with the Germans, and Moljević resigned and was not replaced. This was the end of the Chetnik political organisation given form at Ba.

Despite being planned well before the Second Session of AVNOJ was held, the Ba Congress was widely seen as a response to it. The congress was by far the most important political event for Mihailović's Chetniks during the war. Regardless of the internal changes wrought by the congress, it did not prevent the Western Allies from breaking off contact with the Chetnik movement, and there was no rapprochement with the Partisans. Given the situation in Yugoslavia in early 1944, combined with the split between the British and Chetniks over the latter's failure to resist the Germans, the congress did nothing to improve the position of the Chetnik movement.

During the balance of 1944, the Chetnik position throughout occupied Yugoslavia continued to deteriorate, as the Germans did not trust them, and tentative agreements between the two provided only limited help against their common enemy, the Partisans. The continued Chetnik collaboration also played into the hands of the Partisans from a propaganda standpoint, and undermined morale within Chetniks ranks as they came to the realisation that the Germans would lose the war. In late 1944, the Partisans, along with the Red Army, entered the occupied territory of Serbia, forcing the Chetniks to withdraw into the Sandžak then the NDH alongside German troops. Finally, many Chetniks retreated towards the western borders of Yugoslavia, hoping to surrender to the Western Allies. Mihailović himself was tricked by the Partisans into thinking an uprising against them was underway in Partisan-held Serbia, and when he tried to return to join it he was captured in early 1946. Interrogated and tried for high treason and war crimes by the new Yugoslav authorities, he was found guilty and executed on 17 July of that year.

Notes

Footnotes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Ba Congress 1944 conferences Chetniks Political movements in Yugoslavia January 1944 events Kolubara District 1944 in Serbia