Ynys Afallon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Glastonbury Tor is a hill near

The Tor is in the middle of the Summerland Meadows, part of the

The Tor is in the middle of the Summerland Meadows, part of the

Other explanations have been suggested for the terraces, including the construction of defensive ramparts. Iron Age hill forts including the nearby Cadbury Castle in Somerset show evidence of extensive

Other explanations have been suggested for the terraces, including the construction of defensive ramparts. Iron Age hill forts including the nearby Cadbury Castle in Somerset show evidence of extensive  Another suggestion is that the terraces are the remains of a three-dimensional labyrinth, first proposed by Geoffrey Russell in 1968. He states that the classical

Another suggestion is that the terraces are the remains of a three-dimensional labyrinth, first proposed by Geoffrey Russell in 1968. He states that the classical

A second church, also dedicated to St Michael, was built of local sandstone in the 14th century by the Abbot Adam of Sodbury, incorporating the foundations of the previous building. It included stained glass and decorated floor tiles. There was also a portable altar of Purbeck Marble; it is likely that the Monastery of St Michael on the Tor was a daughter house of

A second church, also dedicated to St Michael, was built of local sandstone in the 14th century by the Abbot Adam of Sodbury, incorporating the foundations of the previous building. It included stained glass and decorated floor tiles. There was also a portable altar of Purbeck Marble; it is likely that the Monastery of St Michael on the Tor was a daughter house of

In 1786,

In 1786,

Glastonbury Tor information at the National TrustGlastonbury , The Camelot Project

{{Good article Church ruins in England Glastonbury Grade I listed buildings in Mendip District Hills of Somerset Locations associated with Arthurian legend Locations in Celtic mythology National Trust properties in Somerset Peaks dedicated to Michael (archangel) Scheduled monuments in Mendip District Former churches in Somerset Footpaths in Somerset Ruins in Somerset Tourist attractions in Somerset

Glastonbury

Glastonbury (, ) is a town and civil parish in Somerset, England, situated at a dry point on the low-lying Somerset Levels, south of Bristol. The town, which is in the Mendip district, had a population of 8,932 in the 2011 census. Glastonbur ...

in the English county of Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lord_ ...

, topped by the roofless St Michael's Tower, a Grade I listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern Irel ...

. The entire site is managed by the National Trust

The National Trust, formally the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, is a charity and membership organisation for heritage conservation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. In Scotland, there is a separate and ...

and has been designated a scheduled monument

In the United Kingdom, a scheduled monument is a nationally important archaeological site or historic building, given protection against unauthorised change.

The various pieces of legislation that legally protect heritage assets from damage and d ...

. The Tor is mentioned in Celtic mythology, particularly in myths linked to King Arthur, and has several other enduring mythological and spiritual associations.

The conical hill of clay and Blue Lias

The Blue Lias is a geological formation in southern, eastern and western England and parts of South Wales, part of the Lias Group. The Blue Lias consists of a sequence of limestone and shale layers, laid down in latest Triassic and early Jurassi ...

rises from the Somerset Levels

The Somerset Levels are a coastal plain and wetland area of Somerset, England, running south from the Mendips to the Blackdown Hills.

The Somerset Levels have an area of about and are bisected by the Polden Hills; the areas to the south a ...

. It was formed when surrounding softer deposits were eroded, leaving the hard cap of sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates ...

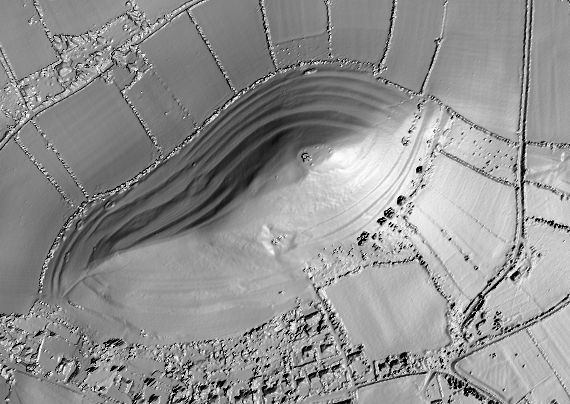

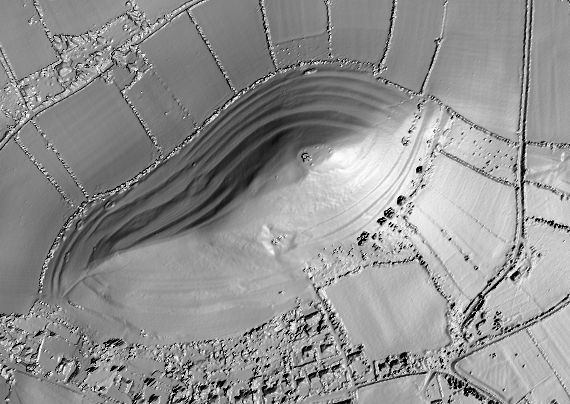

exposed. The slopes of the hill are terraced, but the method by which they were formed remains unexplained.

Archaeological excavations during the 20th century sought to clarify the background of the monument and church, but some aspects of their history remain unexplained. Artefacts from human visitation have been found, dating from the Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostl ...

to Roman eras. Several buildings were constructed on the summit during the Saxon and early medieval periods; they have been interpreted as an early church and monks' hermitage. The head of a wheel cross dating from the 10th or 11th century has been recovered. The original wooden church was destroyed by an earthquake in 1275, and the stone Church of St Michael was built on the site in the 14th century. Its tower remains, although it has been restored and partially rebuilt several times.

Etymology

The origin of the name ''Glastonbury'' is unclear, but when the settlement was first recorded in the late 7th and early 8th centuries it was called . Of the latter name, ''Glestinga'' is obscure and may derive from anOld English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th c ...

word or Celtic personal name. It may derive from a person or kinship group named Glast. The second half of the name, , is Anglo-Saxon in origin and could refer to either a fortified place such as a burh

A burh () or burg was an Old English fortification or fortified settlement. In the 9th century, raids and invasions by Vikings prompted Alfred the Great to develop a network of burhs and roads to use against such attackers. Some were new constr ...

or, more likely, a monastic enclosure.

''Tor

Tor, TOR or ToR may refer to:

Places

* Tor, Pallars, a village in Spain

* Tor, former name of Sloviansk, Ukraine, a city

* Mount Tor, Tasmania, Australia, an extinct volcano

* Tor Bay, Devon, England

* Tor River, Western New Guinea, Indonesia

Sc ...

'' is an English word referring to "a bare rock mass surmounted and surrounded by blocks and boulders", deriving from the Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th c ...

. The Celtic name of the Tor was , or sometimes , meaning 'Isle of Glass'. At this time the plain was flooded, the isle becoming a peninsula at low tide.

Location and landscape

The Tor is in the middle of the Summerland Meadows, part of the

The Tor is in the middle of the Summerland Meadows, part of the Somerset Levels

The Somerset Levels are a coastal plain and wetland area of Somerset, England, running south from the Mendips to the Blackdown Hills.

The Somerset Levels have an area of about and are bisected by the Polden Hills; the areas to the south a ...

, rising to an elevation of . The plain is reclaimed fen

A fen is a type of peat-accumulating wetland fed by mineral-rich Groundwater, ground or surface water. It is one of the main types of wetlands along with marshes, swamps, and bogs. Bogs and fens, both peat-forming ecosystems, are also known as ...

above which the Tor is clearly visible for miles around. It has been described as an island, but actually sits at the western end of a peninsula washed on three sides by the River Brue

The River Brue originates in the parish of Brewham in Somerset, England, and reaches the sea some west at Burnham-on-Sea. It originally took a different route from Glastonbury to the sea, but this was changed by Glastonbury Abbey in the twelft ...

.

The Tor is formed from rocks dating from the early Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The Jurassic constitutes the middle period of ...

Period, namely varied layers of Lias Group

The Lias Group or Lias is a lithostratigraphic unit (a sequence of rock strata) found in a large area of western Europe, including the British Isles, the North Sea, the Low Countries and the north of Germany. It consists of marine limestones, sh ...

strata. The uppermost of these, forming the Tor itself, are a succession of rocks assigned to the Bridport Sand Formation

The Bridport Sand Formation is a formation of Toarcian (Early Jurassic) age found in the Worcester and Wessex Basins of central and southern England. It forms one of the reservoir units in the Wytch Farm oilfield in Dorset. The sandstone is very-f ...

. These rocks sit upon strata forming the broader hill on which the Tor stands; the various layers of the Beacon Limestone Formation and the Dyrham Formation

The Dyrham Formation is a geologic formation in England. It preserves fossils dating back to the early part of the Jurassic period (Pliensbachian).

See also

* List of fossiliferous stratigraphic units in England

See also

* Lists of fossil ...

. The Bridport Sands have acted as a caprock

Caprock or cap rock is a more resistant rock type overlying a less resistant rock type,Kearey, Philip (2001). ''Dictionary of Geology'', 2nd ed., Penguin Reference, London, New York, etc., p. 41.. . analogous to an upper crust on a cake that is ha ...

, protecting the lower layers from erosion.

The iron-rich waters of Chalice Well, a spring

Spring(s) may refer to:

Common uses

* Spring (season)

Spring, also known as springtime, is one of the four temperate seasons, succeeding winter and preceding summer. There are various technical definitions of spring, but local usage of ...

at the base of the Tor, flow out as an artesian well impregnating the sandstone around it with iron oxides that have reinforced it to produce the caprock. Iron-rich but oxygen-poor water in the aquifer carries dissolved iron (II) "ferrous" iron, but as the water surfaces and its oxygen content rises, the oxidised iron (III) "ferric" iron drops out as insoluble "rusty" oxides that bind to the surrounding stone, hardening it.

The low-lying damp ground can produce a visual effect known as a Fata Morgana when the Tor appears to rise out of the mist. This optical phenomenon

Optical phenomena are any observable events that result from the interaction of light and matter.

All optical phenomena coincide with quantum phenomena. Common optical phenomena are often due to the interaction of light from the sun or moon wit ...

occurs because rays of light are strongly bent when they pass through air layers of different temperatures in a steep thermal inversion

In meteorology, an inversion is a deviation from the normal change of an atmospheric property with altitude. It almost always refers to an inversion of the air temperature lapse rate, in which case it is called a temperature inversion. Nor ...

where an atmospheric duct has formed. The Italian term ''Fata Morgana'' is derived from the name of Morgan le Fay

Morgan le Fay (, meaning 'Morgan the Fairy'), alternatively known as Morgan ''n''a, Morgain ''a/e Morg ''a''ne, Morgant ''e Morge ''i''n, and Morgue ''inamong other names and spellings ( cy, Morgên y Dylwythen Deg, kw, Morgen an Spyrys), is a ...

, a powerful sorceress in Arthurian legend

The Matter of Britain is the body of medieval literature and legendary material associated with Great Britain and Brittany and the legendary kings and heroes associated with it, particularly King Arthur. It was one of the three great Wester ...

.

Terraces

The sides of the Tor have seven deep, roughly symmetrical terraces, orlynchet

A lynchet or linchet is an Terrace (earthworks), earth terrace found on the side of a hill. Lynchets are a feature of ancient field systems of the British Isles. They are commonly found in vertical rows and more commonly referred to as "strip lyn ...

s. Their formation remains a mystery with many possible explanations. They may have been formed as a result of natural differentiation of the layers of Lias stone and clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay par ...

or used by farmers during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

as terraced hills to make ploughing for crops easier. Author Nicholas Mann questions this theory. If agriculture had been the reason for the creation of the terraces, it would be expected that the effort would be concentrated on the south side, where the sunny conditions would provide a good yield, but the terraces are equally deep on the northern side, which would provide little benefit. Additionally, none of the other slopes of the island has been terraced, even though the more sheltered locations would provide a greater return on the labour involved.

Other explanations have been suggested for the terraces, including the construction of defensive ramparts. Iron Age hill forts including the nearby Cadbury Castle in Somerset show evidence of extensive

Other explanations have been suggested for the terraces, including the construction of defensive ramparts. Iron Age hill forts including the nearby Cadbury Castle in Somerset show evidence of extensive fortification

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere' ...

of their slopes. The normal form of ramparts is a bank and ditch, but there is no evidence of this arrangement on the Tor. South Cadbury, one of the most extensively fortified places in early Britain, had three concentric rings of banks and ditches supporting an enclosure. By contrast, the Tor has seven rings and very little space on top for the safekeeping of a community. It has been suggested, that a defensive function may have been linked with Ponter's Ball Dyke

Ponter's Ball Dyke is a linear earthwork located near Glastonbury in Somerset, England. It crosses, at right angles, an ancient road that continues on to the Isle of Avalon. It consists of an embankment with a ditch on the east side. It is built ...

, a linear earthwork about east of the Tor. It consists of an embankment with a ditch on the east side. The purpose and provenance of the dyke are unclear. It is possible that it was part of a longer defensive barrier associated with New Ditch

New Ditch is a linear earthwork of possible Iron Age or Medieval construction. It partially crosses the Polden Hills in woodlands approximately south-west from the village of Butleigh in Somerset, England.

Its construction is similar to Ponte ...

, three miles to the south-west, which is built in a similar manner. It has been suggested by Ralegh Radford

Courtenay Arthur Ralegh Radford (7 November 1900 – 27 December 1998) was an English archaeologist and historian who pioneered the exploration of the Dark Ages of Britain and popularised his findings in many official guides and surveys for the O ...

that it is part of a great Celtic sanctuary, probably 3rd century BC, while others, including Philip Rahtz

Philip Arthur Rahtz (11 March 1921 – 2 June 2011) was a British archaeologist.

Rahtz was born in Bristol. After leaving Bristol Grammar School, he became an accountant before serving with the Royal Air Force during the Second World War. D ...

, date it to the post-Roman period and link it to the Dark Age

The ''Dark Ages'' is a term for the Early Middle Ages, or occasionally the entire Middle Ages, in Western Europe after the fall of the Western Roman Empire that characterises it as marked by economic, intellectual and cultural decline.

The conce ...

occupation on Glastonbury Tor. The 1970 excavation suggests the 12th century or later. The historian Ronald Hutton

Ronald Edmund Hutton (born 19 December 1953) is an English historian who specialises in Early Modern Britain, British folklore, pre-Christian religion and Contemporary Paganism. He is a professor at the University of Bristol, has written 14 b ...

also mentions the alternative possibility that the terraces are the remains of a medieval "spiral walkway" created for pilgrims to reach the church on the summit, similar to that at Whitby Abbey

Whitby Abbey was a 7th-century Christian monastery that later became a Benedictine abbey. The abbey church was situated overlooking the North Sea on the East Cliff above Whitby in North Yorkshire, England, a centre of the medieval Northumbrian ...

.

Another suggestion is that the terraces are the remains of a three-dimensional labyrinth, first proposed by Geoffrey Russell in 1968. He states that the classical

Another suggestion is that the terraces are the remains of a three-dimensional labyrinth, first proposed by Geoffrey Russell in 1968. He states that the classical labyrinth

In Greek mythology, the Labyrinth (, ) was an elaborate, confusing structure designed and built by the legendary artificer Daedalus for King Minos of Crete at Knossos. Its function was to hold the Minotaur, the monster eventually killed by t ...

(Caerdroia

A caerdroia is a Welsh turf maze, usually in the sevenfold Cretan labyrinth design. They were created by shepherds on hilltops and were apparently the setting for ritual dances, the nature of which has been lost. At the centre of each caerdr ...

), a design found all over the Neolithic world, can be easily transposed onto the Tor so that by walking around the terraces a person eventually reaches the top in the same pattern. Evaluating this hypothesis is not easy. A labyrinth would very likely place the terraces in the Neolithic era, but given the amount of occupation since then, there may have been substantial modifications by farmers or monks, and conclusive excavations have not been carried out. In a more recent book, Hutton writes that "the labyrinth does not seem to be an ancient sacred structure".

History

Pre-Christian

SomeNeolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several p ...

flint tools recovered from the top of the Tor show that the site has been visited, perhaps with a lasting occupation, since prehistory

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use ...

. The nearby remains of Glastonbury Lake Village

Glastonbury Lake Village was an Iron Age village, situated on a crannog or man made island in the Somerset Levels, near Godney, some north west of Glastonbury in the southwestern English county of Somerset. It has been designated as a schedul ...

were identified at the site in 1892, which confirmed that there was an Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostl ...

settlement in about 300–200 BC on what was an easily defended island in the fens. There is no evidence of permanent occupation of the Tor, but finds, including Roman pottery, do suggest that it was visited on a regular basis.

Excavations

In archaeology, excavation is the exposure, processing and recording of archaeological remains. An excavation site or "dig" is the area being studied. These locations range from one to several areas at a time during a project and can be condu ...

on Glastonbury Tor, undertaken by a team led by Philip Rahtz

Philip Arthur Rahtz (11 March 1921 – 2 June 2011) was a British archaeologist.

Rahtz was born in Bristol. After leaving Bristol Grammar School, he became an accountant before serving with the Royal Air Force during the Second World War. D ...

between 1964 and 1966, revealed evidence of Dark Age

The ''Dark Ages'' is a term for the Early Middle Ages, or occasionally the entire Middle Ages, in Western Europe after the fall of the Western Roman Empire that characterises it as marked by economic, intellectual and cultural decline.

The conce ...

occupation during the 5th to 7th centuries around the later medieval church of St. Michael. Finds included posthole

In archaeology a posthole or post-hole is a cut feature used to hold a surface timber or stone. They are usually much deeper than they are wide; however, truncation may not make this apparent. Although the remains of the timber may survive, most ...

s, two hearths including a metalworker's forge, two burials oriented north–south (thus unlikely to be Christian), fragments of 6th-century Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

amphorae (vases for wine or cooking oil), and a worn hollow bronze head which may have topped a Saxon staff.

Christian settlement

During the late Saxon and early medieval period, there were at least four buildings on the summit. The base of a stone cross demonstrates Christian use of the site during this period, and it may have been a hermitage. The broken head of a wheel cross dated to the 10th or 11th century was found partway down the hill and may have been the head of the cross that stood on the summit. The head of the cross is now in theMuseum of Somerset

The Museum of Somerset is located in the 12th-century great hall of Taunton Castle, in Taunton in the county of Somerset, England. The museum is run by South West Heritage Trust, an independent charity, and includes objects initially collected ...

in Taunton

Taunton () is the county town of Somerset, England, with a 2011 population of 69,570. Its thousand-year history includes a 10th-century monastic foundation, Taunton Castle, which later became a priory. The Normans built a castle owned by the ...

.

The earliest timber church, dedicated to St Michael

Michael (; he, מִיכָאֵל, lit=Who is like El od, translit=Mīḵāʾēl; el, Μιχαήλ, translit=Mikhaḗl; la, Michahel; ar, ميخائيل ، مِيكَالَ ، ميكائيل, translit=Mīkāʾīl, Mīkāl, Mīkhāʾīl), also ...

, is believed to have been constructed in the 11th or 12th century; from which post holes have since been identified. Associated monk cells have also been identified.

St Michael's Church was destroyed by an earthquake on 11 September 1275. According to the British Geological Survey, the earthquake was felt in London, Canterbury and Wales, and was reported to have destroyed many houses and churches in England. The intensity of shaking was greater than 7 MSK, with its epicentre in the area around Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

or Chichester

Chichester () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and civil parish in West Sussex, England.OS Explorer map 120: Chichester, South Harting and Selsey Scale: 1:25 000. Publisher:Ordnance Survey – Southampton B2 edition. Publi ...

, South England.

A second church, also dedicated to St Michael, was built of local sandstone in the 14th century by the Abbot Adam of Sodbury, incorporating the foundations of the previous building. It included stained glass and decorated floor tiles. There was also a portable altar of Purbeck Marble; it is likely that the Monastery of St Michael on the Tor was a daughter house of

A second church, also dedicated to St Michael, was built of local sandstone in the 14th century by the Abbot Adam of Sodbury, incorporating the foundations of the previous building. It included stained glass and decorated floor tiles. There was also a portable altar of Purbeck Marble; it is likely that the Monastery of St Michael on the Tor was a daughter house of Glastonbury Abbey

Glastonbury Abbey was a monastery in Glastonbury, Somerset, England. Its ruins, a grade I listed building and scheduled ancient monument, are open as a visitor attraction.

The abbey was founded in the 8th century and enlarged in the 10th. It w ...

. In 1243 Henry III granted a charter for a six-day fair at the site.

St Michael's Church survived until the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1539 when, except for the tower, it was demolished. The Tor was the place of execution where Richard Whiting, the last Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey, was hanged, drawn and quartered along with two of his monks, John Thorne and Roger James. The three-storey tower of St Michael's Church survives. It has corner buttress

A buttress is an architectural structure built against or projecting from a wall which serves to support or reinforce the wall. Buttresses are fairly common on more ancient buildings, as a means of providing support to act against the lateral ( ...

es and perpendicular bell openings. There is a sculptured tablet with an image of an eagle below the parapet.

Post-dissolution

Richard Colt Hoare

Sir Richard Colt Hoare, 2nd Baronet FRS (9 December 1758 – 19 May 1838) was an English antiquarian, archaeologist, artist, and traveller of the 18th and 19th centuries, the first major figure in the detailed study of the history of his home ...

of Stourhead bought the Tor and funded the repair of the tower in 1804, including the rebuilding of the north-east corner. It was then passed on through several generations to the Reverend George Neville and included in the Butleigh Manor until the 20th century. It was then bought as a memorial to a former Dean of Wells

The Dean of Wells is the head of the Chapter of Wells Cathedral in the Mendip district of Somerset, England. The dean's residence is The Dean's Lodging, 25 The Liberty, Wells.

List of deans

High Medieval

*1140–1164: Ivo

*1164–1189: Ric ...

, Thomas Jex-Blake

Thomas William Jex-Blake (1832–1915) was an Anglican priest and educationalist.

He was born on 26 January 1832, the son of lawyer Thomas Jex-Blake and the brother of Sophia Jex-Blake, who was a pioneer in women doctors in the United Kingdom. He ...

, who died in 1915.

The National Trust

The National Trust, formally the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, is a charity and membership organisation for heritage conservation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. In Scotland, there is a separate and ...

took control of the Tor in 1933, but repairs were delayed until after the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. During the 1960s, excavations identified cracks in the rock, suggesting the ground had moved in the past. This, combined with wind erosion, started to expose the footings of the tower, which were repaired with concrete. Erosion caused by the feet of the increasing number of visitors was also a problem and paths were laid to enable them to reach the summit without damaging the terraces. After 2000, enhancements to the access and repairs to the tower, including rebuilding of the parapet, were carried out. These included the replacement of some of the masonry damaged by earlier repairs with new stone from the Hadspen Quarry.

A model vaguely based on Glastonbury Tor (albeit with a tree instead of the tower) was incorporated into the opening ceremony of the 2012 Summer Olympics in London. As the athletes entered the stadium, their flags were displayed on the terraces of the model.

Mythology and spirituality

The Tor seems to have been called ''Ynys yr Afalon'' (meaning "The Isle of Avalon") by theBritons

British people or Britons, also known colloquially as Brits, are the citizens of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the British Overseas Territories, and the Crown dependencies.: British nationality law governs mod ...

and is believed by some, including the 12th and 13th century writer Gerald of Wales

Gerald of Wales ( la, Giraldus Cambrensis; cy, Gerallt Gymro; french: Gerald de Barri; ) was a Cambro-Norman priest and historian. As a royal clerk to the king and two archbishops, he travelled widely and wrote extensively. He studied and taugh ...

, to be the Avalon

Avalon (; la, Insula Avallonis; cy, Ynys Afallon, Ynys Afallach; kw, Enys Avalow; literally meaning "the isle of fruit r appletrees"; also written ''Avallon'' or ''Avilion'' among various other spellings) is a mythical island featured in the ...

of Arthurian legend

The Matter of Britain is the body of medieval literature and legendary material associated with Great Britain and Brittany and the legendary kings and heroes associated with it, particularly King Arthur. It was one of the three great Wester ...

. The Tor has been associated with the name Avalon, and identified with King Arthur, since the alleged discovery of his and Queen Guinevere's neatly labelled coffins in 1191, recounted by Gerald of Wales

Gerald of Wales ( la, Giraldus Cambrensis; cy, Gerallt Gymro; french: Gerald de Barri; ) was a Cambro-Norman priest and historian. As a royal clerk to the king and two archbishops, he travelled widely and wrote extensively. He studied and taugh ...

. Author Christopher L. Hodapp asserts in his book ''The Templar Code for Dummies'' that Glastonbury Tor is one of the possible locations of the Holy Grail

The Holy Grail (french: Saint Graal, br, Graal Santel, cy, Greal Sanctaidd, kw, Gral) is a treasure that serves as an important motif in Arthurian literature. Various traditions describe the Holy Grail as a cup, dish, or stone with miracu ...

, because it is close to the monastery that housed the Nanteos Cup.

With the 19th century resurgence of interest in Celtic mythology, the Tor became associated with Gwyn ap Nudd, the first Lord of the Otherworld (Annwn

Annwn, Annwfn, or Annwfyn (in Middle Welsh, ''Annwvn'', ''Annwyn'', ''Annwyfn'', ''Annwvyn'', or ''Annwfyn'') is the Otherworld in Welsh mythology. Ruled by Arawn (or, in Arthurian literature, by Gwyn ap Nudd), it was essentially a world of de ...

) and later King of the Fairies. The Tor came to be represented as an entrance to Annwn or to Avalon, the land of the fairies. The Tor is supposedly a gateway into "The Land of the Dead (Avalon)".

A persistent myth of more recent origin is that of the Glastonbury Zodiac, a purported astrological zodiac

The zodiac is a belt-shaped region of the sky that extends approximately 8° north or south (as measured in celestial latitude) of the ecliptic, the apparent path of the Sun across the celestial sphere over the course of the year. The pat ...

of gargantuan proportions said to have been carved into the land along ancient hedge

A hedge or hedgerow is a line of closely spaced shrubs and sometimes trees, planted and trained to form a barrier or to mark the boundary of an area, such as between neighbouring properties. Hedges that are used to separate a road from adjoin ...

rows and trackways, in which the Tor forms part of the figure representing Aquarius. The theory was first put forward in 1927 by Katherine Maltwood

Katharine Emma Maltwood (née Sapsworth) was a writer and artist on the esoteric and occult. Throughout her childhood, she was reared to be an artist. Her parents were progressive, and they pushed each of their children equally to achieve their ...

, an artist with interest in the occult, who thought the zodiac was constructed approximately 5,000 years ago. But the vast majority of the land said by Maltwood to be covered by the zodiac was under several feet of water at the proposed time of its construction, and many of the features such as field boundaries and roads are recent.

The Tor and other sites in Glastonbury have also been significant in the modern-day Goddess movement

The Goddess movement includes spiritual beliefs or practices (chiefly Neopagan) which emerged predominantly in North America, Western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand in the 1970s. The movement grew as a reaction to perceptions of predominant ...

, with the flow from the Chalice Well seen as representing menstrual flow and the Tor being seen as either a breast or the whole figure of the Goddess. This has been celebrated with an effigy of the Goddess leading an annual procession up the Tor.

It is said that Brigid of Kildare

Saint Brigid of Kildare or Brigid of Ireland ( ga, Naomh Bríd; la, Brigida; 525) is the patroness saint (or 'mother saint') of Ireland, and one of its three national saints along with Patrick and Columba. According to medieval Irish hagiogr ...

is depicted milking a cow as a stone carving above one of the entrances to the tower.The Goddess in Glastonbury, by Kathy Jones, 1990 Ariadne Publications

See also

*List of hillforts and ancient settlements in Somerset

Somerset is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is a rural county of rolling hills, such as the Mendip Hills, Quantock Hills and Exmoor National Park, and large flat expanses of land including the Somerset Levels. Modern man came to ...

*List of National Trust properties in Somerset

The National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty (informally known as the National Trust) owns or manages a range of properties in the ceremonial county of Somerset, England. These range from sites of Iron and Bronze Age oc ...

* 1275 British earthquake

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * *External links

Glastonbury Tor information at the National Trust

{{Good article Church ruins in England Glastonbury Grade I listed buildings in Mendip District Hills of Somerset Locations associated with Arthurian legend Locations in Celtic mythology National Trust properties in Somerset Peaks dedicated to Michael (archangel) Scheduled monuments in Mendip District Former churches in Somerset Footpaths in Somerset Ruins in Somerset Tourist attractions in Somerset